PLANNING A HEAT RESILIENT CITY

GREATER GROVE HALL, BOSTON

Fall 2024

City Planning Studio

INTRODUCTION

Cities are more susceptible to extreme heat, and other impacts of the climate crisis, than rural areas because of the higher coverage of impervious surfaces (buildings, sidewalks, roads, etc) that trap heat a phenomenon known as the “urban heat island effect”. Dealing with extreme heat is one of the most pressing needs for urban planners and policymakers.

This study will explore how urban planning is evolving to address the escalating heat challenges and create resilient, climate-adaptive cities with a focus on a Greater Grove Hall in Boston, Massachusetts. In April 2022, the City of Boston published Heat Resilience Solutions for Boston.

The report provides a framework of how Boston can prepare its communities, buildings, infrastructure, and natural spaces for the impacts of climate change, including extreme heat, while putting Boston on a path to becoming a Green New Deal city. Boston is already under heat stress, experiencing an average temperature increase of 3.5 degrees greater than the global average. To build resilience to heat, Boston must address three factors of heat risk: exposure to extreme heat, the adaptive capacity to access cooling, and the sensitivity to changes in temperature due to underlying factors like health or age that may influence vulnerability to heat. As planners this entails re-envisioning the built environment to ensure equitable access to indoor and outdoor spaces that help preserve the health and well-being of residents, reduce temperatures in hotspots, and provide features that support resilience and emergency preparedness.

Our Purpose

As planners, we aim to reimagine the built environment through advancement in heat resilience to ensure equitable communities. By building better infrastructure, refining land use patterns, fostering social cohesion, and addressing policy gaps, we strive to address urban heat challenges, enhance emergency preparedness, and foster stronger, more inclusive communities. Rooted in principles of sustainability and adaptability, our efforts pave the way for thriving, inclusive, and climate-resilient futures.

Figure 1: Team at the City of Boston Planning Department

MEET OUR TEAM

Our team of 13 students from different concentrations with City and Regional Planning, along with our wonderful instructors Meishka and Ben, exaplored with issues of Extreme Heat in Boston. On our site visit, we listened to the concerns of the commuity and city officials to get a better understanding of the neighborhood and its residents.

Meishka L. Mitchell

Alice Kansiime Smart Cities

William Wang Sustainable Transportation and Infrastructure Planning

Revathi Machan Housing and Economic Development

Michael Clifford Sustainable Transpor tation and Infrastructure Planning

Kuma Luo Smart Cities

Hao Zhu Smart Cities

Wenjun Zhu Smart Cities

Shuai Wang Smart Cities

Avani Adhikari Smart Cities

Ryan Smith Sustainable Transportation and Infrastructure Planning

Elva Jiang Land Use and Environmental Planning

Adil Belgaumi Land Use and Environmental Planning

Riya Saini Sustainable Transportation and Infrastructure

Ben Bryant

01 HEAT AS A PLANNING ISSUE

HEAT AS A PLANNING ISSUE

Due to climate change, heat waves are becoming a more common occurrence across American cities (US EPA, n.d). Though unusually hot days are a part of Earth’s natural temperature cycle, increase in global temperatures due to climate change are making extreme heat events have seasons longer, more frequent, more intense (Marvel et al, 2023).

The increase in extreme heat risk has important implications to human health. For our bodies to function properly, it must maintain a stable internal temperature through a process called homeostasis. However, even a small increase in outside temperatures can disrupt this process leading to significant physiological damage (Beker et al, 2018). Extreme heat can increase the risk of hospitalisation for heart disease.

Climate Change is increasing the lengths of the heat wave season as well as the frequency of heat waves. Data source: US EPA.

Top:

Additionally, heat exhaustion and dehydration during heat strokes can cause critical illness, brain and kidney injury. Aside from these direct effects on the human body, heat can worsen asthma and other chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (US HHS, n.d).

As a result, it is unsurprising to note heat killed an estimated 11,000 people in 2023, a record high number since records were first kept (Borenstein, 2024) Heat disproportionately affects vulnerable populations—people without access to healthcare, those with compromised health conditions and weaker immune systems. Some groups that are extremely vulnerable to heat are:

• Older adults aged 65+

• Children and young infants

• Houseless populations

• Outdoor workers

• People with chronic health conditions (US HHS, n.d)

HEAT AS A PLANNING ISSUE

Top: Extreme Heat affects the physiology of the human body, leading to significant health impacts.

Building materials such as concrete and asphalt retain more heat

HEAT AS A PLANNING ISSUE

Cities lack green spaces that mitigate

Car exhaust exacerbated urban heat

"Heat is disproportionately felt in our cities"

Heat in our Cities

While heat can detrimentally affect people anywhere, it takes on a more insidious character in the concrete jungles of our cities. In its base form, heat is energy; due to their physical and chemical characteristics, different materials absorb and emit this energy at different rates. Asphalt Concrete, the foundational building block of our cities, has a high thermal capacity and hence absorbs and radiates more heat (Mohajerani et al, 2017). On a sunny day, a concrete parking lot will have much higher temperatures than a grassy park, even if they are physically proximate to one another.

Alongside retaining external heat, cities also produce their own heat. Energy consumption of buildings, vehicular emissions—all produce heat that can make cities feel much hotter than what is displayed on a thermometer.

The phenomena of cities experiencing higher daytime heat due to their structure is known as Urban Heat Island. The EPA defines Heat Islands as “urbanised areas that experience higher temperatures than outlying areas…[and] become “islands” of higher temperatures relative to outlying areas.” In these heat islands, daytime temperatures can be 1–7°F higher than temperatures in outlying areas and nighttime temperatures are about 2-5°F higher (US EPA, n.d).

Top: Diagram showing built environment and its relationship with extreme heat.

HEAT AS A PLANNING ISSUE

Cold cities are experiencing a much more drastic rise in temperatures than traditionally hot cities. Boston, a traditionally colder city, will take temperatures similar to Memphis by 2070.

HEAT AS A PLANNING ISSUE

Heat in Boston

Boston, a historically cold city, is not prepared to deal with the rising temperatures in its urban area. Despite being known for its cold winters, summer temperatures in Boston have been increasing decade on decade at an alarming and irreversible rate.

Even if major reductions in emissions were to occur, Boston’s current trajectory of temperature change has been locked in. By 2070, the number of days over 100°F (38°C) is expected to increase from 10 to up to 46 by 2070 (City of Boston, 2022). Hence, it is existential that the city builds resilience strategies in order to combat extreme heat.

For Boston, building extreme heat resilience is not just a matter of adapting to climate change, but also enacting environmental justice. Though Boston’s temperatures

are increasing across the board, the burden of heat is higher for its vulnerable communities. Historic disinvestment has decimated the access to heat mitigating features such as parks and green spaces in some neighborhoods. As a result, temperatures in these disadvantaged neighborhoods can be 7.5% hotter than the Boston average (City of Boston, 2022).

Top: Graph of Average monthly temperatures in Boston

02 EXISTING CONDITIONS

Key Map

Grove Hall is located South of Boston’s Downtown. It hugs the outskirts of the bigger neighborhoods of Roxbury and Dorchester. Two main streets–Columbia Road and Blue Hill Ave bisect the neighborhood.

Three commuter rail stations lie either within or close to its borders. However, the neighborhood doesn’t house any MBTA subway stations, meaning that most residents depend on Bus services for within-city commutes. Aside from these transportation features, the large Franklin Park and Zoo at its Southern edge make up the neighbourhood’s spatial geography.

However, despite its proximity to Franklin Park, the neighborhood is a hot spot for Urban Heat Island effects. The concrete and asphalt roads of the neighborhood along Blue Hill Ave and Columbia road retain daytime heat, leaving those areas up to 6° F higher than what would normally be observed at those temperatures. Hence, people living in these areas will experience higher temperatures in normal heat events and higher duration of extreme heat events.

A s a histori c ally disinve ste d neighborhood, Grove Hall is vulnerable

INTRODUCTION

to many other environmental burdens alongside heat. The neighbourhood has been found to have the highest risk of lead exposure due to the age of its homes, and children from this area have shown to have high levels of lead in their blood (City of Boston, 2002).

Brownfields are another area of concern with the neighbourhood having a high concentration of potentially contaminated industrial land. Despite only occupying 3.4% of Boston’s total land area, the neighbourhood is home to 39% of the city’s industrially contaminated land (Gaskin, n.d).

Additionally, the impact of traffic along its main roads has resulted in a high prevalence of asthma for the area (Gaskin, n.d). All of this underscores a very urgent need to drive investments towards building climate resilience in this neighbourhood.

Participants of a Neighborhood Ideas Workshop conducted by the City of Boston, also highlighted their conerns regarding the neighborhood’s hot sidewalks, limited cool social spaces,, hot homes and cooling affordability.

“

...is one of the more affordable neighborhoods in Boston, and it comes at a price because landlords do not install air units."

“

Walking to parks is very hot, even if parks themselves are cooler"

“

More public places that are open all day and in the evenings that have activities for kids and space for adults that have air conditioning"

Top: Resident comments from the 'Heat Resilient Solutions for Boson Final Report'.

HISTORY

Origins, Annexation, and Early History

Grove Hall originates from the name of Thomas Kilby Jones’ estate, which overlooked the intersection of what is now Blue Hill Avenue and Washington St. The area was predominantly rural in character during its early history and hosted several horticultural estates. This rapidly changed, however, when Boston’s annexation of Roxbury in 1868 spurred housing development and streetcar lines into the neighborhood.

From 1900 - World War II, Grove Hall became the center of Jewish life in Boston. Several of the neighborhood’s landmarks were constructed during this time, including Blue Hill Synagogue in 1906. Following national trends, the Great Migration led to a growing Black/African American community. Likewise, the end of WWII brought about postwar suburbanization, starting a new period of decline in Grove Hall.

Decline, Turbulence, and Re-investment

The Mishkan Tefila, one of New England’s most important synagogues, moved to the suburbs in 1958, and is seen as a turning point in the neighborhood’s history. Discriminatory lending practices meant while Jewish and white residents could suburbanize, Black and Brown residents were denied access to federallybacked housing loans, started patterns of disinvestment in the neighborhood and leading to a period of ethnic tension and turbulence.

A major riot occurs in the neighborhood in the late 1960s, protesting unannounced welfare cut-offs. Escalated due to excessive force by police, the riot causing damage to 15 blocks and the arrest of 44 people, including a prominent civil rights leader. Further disinvestment by the City of Boston followed after the riots, continuing for several decades. However, Grove Hall is now the subject of several reinvestment plans, including the development of the Mecca Mall in 2000.

Today, Grove Hall is among the most diverse neighbourhoods in Boston with a large Black, Latino, and immigrant population. There are almost three times more people living in the neighbourhood that identify themselves as Black or African American than in the rest of Boston.

Alongside this, almost 30% of all residents identify ethnically as hispanic compared to 19% in Boston. Finally, 35% of all residents identify as “Foreign Born” in Grove Hall, compared to 28% in Boston. Among this foreign born population, Nigeria and Sierra Leone are stated to be the most common home countries in the 2022 ACS.

Interestingly, the dominant share of neighbourhood residents are children below the age of 18. A quarter of all Grove Hall residents are children, 10% more than the proportion in Boston. The percentage of young adults (18-30) in Grove Hall is lower than other Boston neighbourhoods, likely

DEMOGRAPHICS

influenced by its location away from the city’s university districts.

A very high proportion of households in Grove Hall are single female-led households as compared to Boston. In the 2022 ACS, almost 60% of all households in Grove Hall identified as “single female-led”, almost 23% higher than the rest of Boston.

Grove Hall

Boston

Top Right: Racial distribution in Boston vs. Grove Hall.

Bottom Right: Demography distribution in Boston vs. Grove Hall.

The Grove Hall neighborhood predominantly features older housing (more than 70 years), with a mix of three- and two-family residential homes, as well as several apartment buildings and condominiums along Blue Hill Avenue. The real estate is characterized by small-tomedium-sized apartment buildings and townhomes, along with large commercial, institutional, and mixeduse properties, such as the Roxbury YMCA and the Roxbury Branch of the Boston Public Library. Approximately 72% of the housing units are renteroccupied, while the remaining 28% are owner-occupied. Residents in owneroccupied homes earn three times more than renters.

Despite 19.2% of Boston’s housing stock being designated as incomerestricted, housing affordability remains a major challenge. In 2021, 36% of all new housing production was income-restricted, yet demand far exceeds supply, with rising home prices exacerbating the housing crisis. A significant 52% of households in Boston are rent-burdened, and many renters in Grove Hall face financial strain. Additionally, energy inefficiencies are common in the neighborhood’s aging housing stock,

HOUSING

leading to higher energy burdens. Some households spend up to 19% of their income on energy costs— six times the city’s median average— further exacerbating the financial stress of residents, particularly during the summer months when extreme heat drives up cooling costs.

The housing crisis in Grove Hall has contributed to an increase in public assistance dependency, with four of the five census tracts in the neighborhood seeing higher percentages of households receiving aid. The risk of homelessness is particularly acute for elderly renters, many of whom are struggling to pay rising rents. Boston ranks second in the nation for its homeless population, with 70% of its homeless individuals being families.

Although Boston’s Right to Shelter law provides some protections, it is insufficient to address the growing need for housing. In 2023, 20% of the city ’s unsheltered homeless population lived in cars or abandoned buildings. Vulnerable individuals, including the elderly, face heightened health risks, including increased susceptibility to heat-related illnesses, as extreme temperatures intensify

their energy burdens. Additionally, unhoused individuals face barriers to accessing cooling centers, which often require identification, making it even more difficult for them to find relief during heat events. As homelessness

continues to rise, the need for more affordable housing is urgent to provide protection from extreme heat and prevent further displacement of residents, particularly the elderly and other vulnerable populations.

LAND USE

Grove Hall’s land use patterns keep it relatively cool compared to Boston as a whole, but concentrated areas of higher development result in particularly high temperatures in certain sections. The neighborhood is predominantly residential comprised of largely two- and three-family residential-only zones, with often large minimum lot sizes. Many homes have side yards, but secondary lots used as paved driveways are also common. These areas correspond with the sections of the neighborhood with more canopied and unpaved areas, visible in the landcover map on the next page. As a result, urban heat island effect is generally lower in these areas, with the heat island index generally not exceeding 4.5 degrees Fahrenheit.

The area has some commercial and mixed-use land use, abundant land for institutional uses, and sparse industrial land use as well. These uses are interspersed

throughout the neighborhood but are largely concentrated along the neighborhood’s main circulatory corridors: Blue Hill Avenue, Warren Street, Columbia Road, and Washington Street. These developments including schools and shopping malls, often feature large buildings with large paved parking lots or other adjoining spaces. As a result, these areas overall have a much higher density of impervious, heat absorbing paved surfaces like concrete, and as a result have a much higher urban heat island effect.

As can be seen on the following page, the area near the center of the neighborhood, near the confluence of Blue Hill Avenue, Warren Street, Washington Street and Geneva Avenue, experiences the highest heat island effect in the neighborhood, with heat island indices exceeding 6 degrees Fahrenheit. This is Grove Hall’s largest commercial area and the site of a major mall, Grove Hall’s Mecca.

Left: Land Use map of Grove hall

Right: Green Spaces an Heat map of Grove Hall

LAND USE

COOLING INFRASTRUCTURE

The City of Boston

has been updating cooling resources f or citizens to keep them cool from the urban heat. According to the website, the resources include spray play spots, public pools, public libraries, and cooling centers. The Map shows existing cooling infrastructure around Grove Hall proposed by the City that people can go to one of the spots if necessary. Most spray play spots are around parks and cooling centers and libraries are around the community center. Moreover, the City produced the Cooling Guide 2024 that introduced more temporary infrastructure for people to cool down.

The infrastructure includes Pop-Up Misting Tent, Passive Misting Station, User-Activated Misting Station, Seasonal Cooling Plaza, and Indoor Cooling Station.

In all, the City plays an important role in recognizing cooling infrastructure and promoting such infrastructure to citizens. However, it is unknown whether residents in Grove Hall can benefit from cooling infrastructure because of its historically disinvested status and homeless population. Considering Grove Hall’s demographics and characteristics is essential for an infrastructure plan to better benefit the community.

Right: Map of cooling infrastructure in Grove Hall.

GREEN COVER

The existing condition of street trees in Grove Hall reveals a significant imbalance in their distribution across the area, especially along the main streets. This uneven distribution contributes to reduced shade coverage, exacerbating the urban heat island effect and impacting pedestrian comfort.

Discontinuous Tree Planting Along Main Streets

Street tree coverage in Grove Hall is inconsistent, with main streets suffering from sparse planting and frequent gaps. Despite the wider roadways that present opportunities for tree planting, the current arrangement is inadequate, leaving pedestrians and vehicles exposed to direct sunlight and increasing thermal discomfort during heatwaves. In contrast, some residential streets benefit from better tree coverage, highlighting the need for more strategic planting along major corridors.

Mature Trees Clustered Only in Northwestern Grove Hall

Larger, mature trees are concentrated in the northwestern part of Grove Hall, providing significant shade. However, their uneven distribution leaves other areas, especially main streets, vulnerable to extreme heat impacts.

Top: Tree cover with Red circles highlighting trees with canopies larger than the regional average.

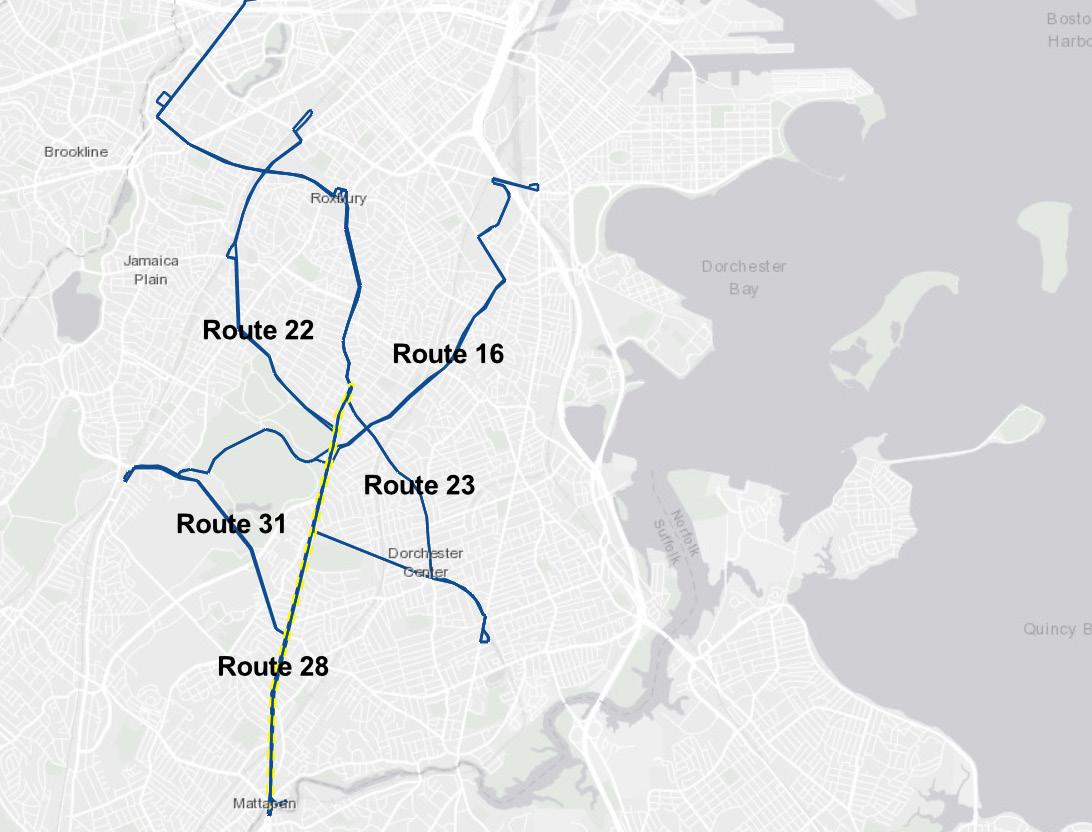

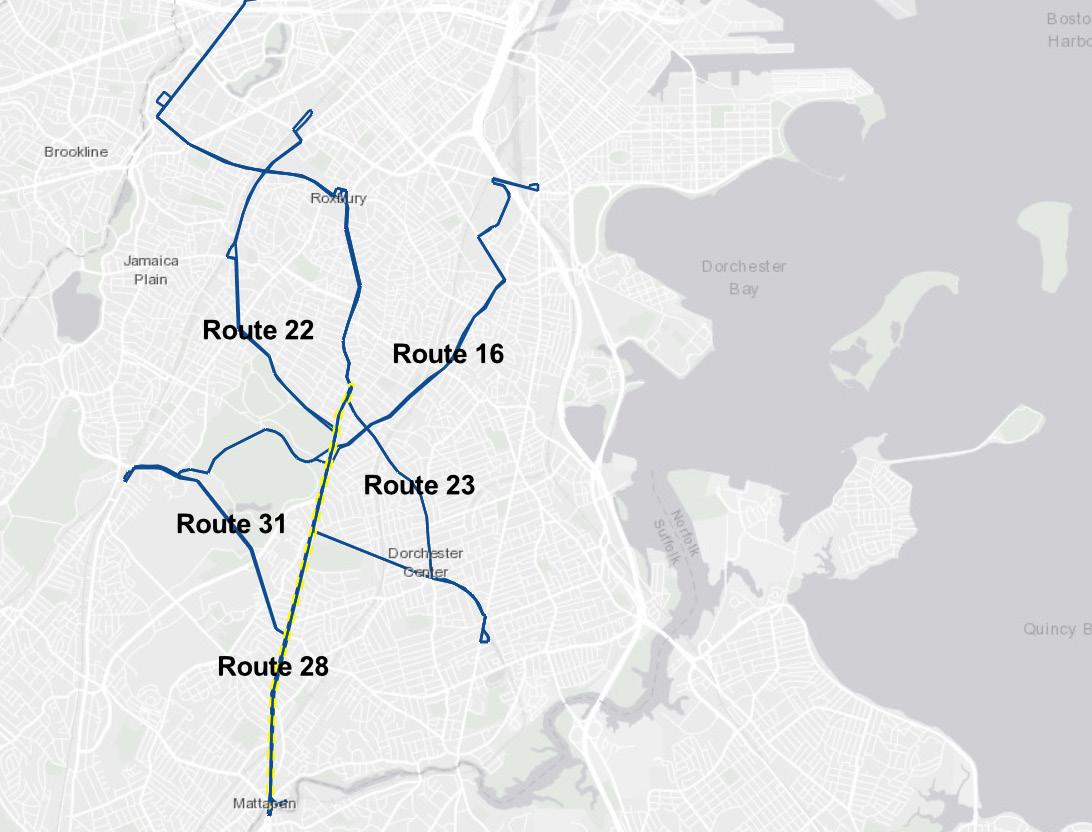

Top left: Map of public transportation routes passing through Grove Hall.

Top Right: Map of Average Annual Daily Traffic through Grove Hall.

TRANSPORTATION

Although car is the most popular way to commute in Grove Hall, transit ridership remains high. According to ACS estimates,51% of Grove Hall residents commute to work by automobile, which is higher than the city-wide rate of 40%. Even so, 33% Grove Hall residents also commute by public transportation vs. 25% city-wide. Major arterials cutting through Grove Hall; Blue Hill Ave, Seaver St, Columbia Rd, and Warren St, all are four lanes for at least part of their length.The sections of Seaver Street and Blue Hill Ave designated as Massachusetts Route 28 and have by far the highest average daily traffic volumes in the neighborhood (BostonMaps, 2024). Blue Hill Ave also serves as the major commercial corridor for Grove Hall.Transforming these busy corridors into cool, heart resilient thoroughfares will be an important element of this plan.

The neighborhood is not directly served by the Massachusetts BayTransportation Authority (MBTA) subway network, making buses the most important form of public transit.Two of the MBTA’s busiest conventional bus routes, the 28 and the 23, run through the middle of Grove Hall, serving a combined 20,000 riders on an average day (Transit Matters, 2024).These routes, as well as route 29, are currently fare-free under a program funded by the City of Boston (MBTA, n.d.). Blue Hill Ave is the busiest bus corridor in New England, seeing 27,000 daily riders, while bus riders make up as much as 50% of all road users during rush hour (Volcy, 2024). Improving the experience of these bus riders during periods of extreme heat will be another focus of this plan. Grove Hall is also served by the Fairmount Line of the MBTA Commuter Rail system at the Four Corners/Geneva Station, as well as the Uphams Corner andTalbot Avenue Stations at the neighborhood’s northern and southern edges. While the Fairmount Line sees much less ridership than the local buses, service has been improving in the last decade, with the construction of modern stations, fare reductions, and more frequent service.The line may also be the first in the system to use battery-electric trains, reflecting the increasing importance of this service (MBTA, 2024).

There are plans underway to transform two of Grove Hall’s major arterials, Blue Hill Ave and Columbia Rd. to include a center-running bus lanes to speed travel times, as well as protected bike lanes for Blue Hill Ave as far north as Warren St. Meanwhile, Columbia Ave is being re-imagined as a tree-lined linear park, with safety improvements, extending Boston’s extensive“Emerald Necklace”system of parks and parkways from Franklin Park northwest to Moakley Park on Dorchester Bay (Volcy, 2024, StreetsBlog Mass, 2024).

• High share of Black, Latino, and immigrants contribute to Diverse and Vibrant community-driven solutions.

• Proximity to Green Spaces and associated spray parks, misting stations offer cooling and recreational benefits.

• Key bus and commuter rail stops provide Accessible Public Transit, with affordable fare-free programs.

• City initiatives, like Pop-Up Misting Tents and seasonal cooling plazas, aim to address extreme heat challenges.

• Historic resilience of residents provides avenues for Community Engagement on climate adaptation goals.

• Active Urban Revitalization Plans for tree-lined corridors, bus lanes, and protected bike lanes on Blue Hill Ave and Columbia Rd enhance resilience and accessibility.

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats S

• High impervious surfaces exacerbates Urban Heat Island Effect

• Energy inefficiencies due to Aging Housing Stock lead to increased cooling costs for rent-burdened households.

• Lack of MBTA subway access Limits Transportation options for residents.

• Lead exposure, industrial brownfields, and traffic-related asthma compounds Environmental Burdens.

W• Plans for Blue Hill Ave and Columbia Rd present opportunities to Integrate Heat-Resilient Infrastructure.

• Growing Awareness to Extreme Heat as a Policy Priority enables funding and innovation.

• High concentrations of children, older adults, and immigrants allow Tailored Programs to address specific vulnerabilities.

• Public-Private Partnerships for developing affordable housing can drive equitable outcomes.

• Use of smart sensors, Energy-Efficient Building Technologies, and AI-based heat solutions can enhance planning outcomes.

• Expanding Boston’s Emerald Necklace system through Columbia Ave offers a nature-based planning solutions.

O• High percentages of Rent-Burdened households and reliance on public assistance impede community resilience efforts.

• Historical disinvestment may Limit Equitable Access of Cooling Resources for vulnerable populations.

T• Predicted increases in days over 100°F by 2070 will Intensify Heat-Related Health Risks.

• Wealth Gap between renters and homeowners may deepen inequalities in access to cooling and housing.

• Barriers to accessing cooling centers increases Risks for Un-housed Individuals.

• Long-standing patterns of Historical Disinvestment may hinder the success of investments and community distrust.

• Environmental Contamination add layers of vulnerability, complicating resilience efforts.

• Increased heat may Strain Energy Systems and transit reducing their reliability during extreme heat events.

03 RECOMMEND- ATIONS

Build Better Infrastructure

Land Use Patterns

Build Better Infrastructure

This section explores strategies to enhance transportation infrastructure and address urban heat challenges in Grove Hall, a neighborhood where nearly 40% of residents depend on public transit. Despite the area’s importance as a transit hub, issues such as congestion, delays, and extreme heat remain persistent obstacles to mobility and quality of life. To build on the efforts of the City of Boston, this chapter proposes expanding transit connectivity and implementing innovative cooling solutions. By incorporating community-driven designs, greenery, and advanced materials, these interventions aim to improve the transit experience while fostering resilience against extreme heat.

Existing Infrastructure Plans

BOSTON’S HEAT RESILIENCE PLAN

This plan presents new methodologies, updated future temperature projections, new extreme temperature models, heat risk and vulnerability profiles for five environmental justice focus areas, the City’s heat resilience strategies, and next step actions to advance heat resilience across Boston. Inputs to the plan included existing plans and programs for climate resilience in Boston and the broader region, as well as detailed heat modeling and stakeholder and community discussions.

COOLER COMMUTES

In the Boston Heat Resilience Plan this inititative includes shaded and cooling bus stops through increased tree plantings, misters and cooler fans, and other operational and service improvements.

ENHANCED COOLING IN POCKET GREEN SPACES AND STREET -TO-GREEN CONVERSIONS

This initiative builds on other cooling strategies like cooler commutes

OPEN SPACE AND RECREATION PLAN 2023-2029

OSPR is a detailed document that goes through Boston’s entire environmental history and goes over the key issues and concerns within the city that prevent people from accessing or using the green spaces that exist currently. They’ve developed specific goals to improve, increase and maintain the park spaces throughout boston and have found sites to invest in green spaces within various communities.

BUS SHELTER 2.0

The Consolidated Smart Shuttle System, the MBTA’sThe RIDE, and the Age Strong Shuttle can be integrated into a comprehensive emergency transit network to support vulnerable populations during extreme heat events. While The RIDE and the Age Strong Shuttle already focus on individuals with mobility challenges and older adults, their reach can be expanded to include other atrisk groups, such as children and individuals with chronic conditions like asthma or heart disease. By utilizing real-time tracking apps and placing shaded or covered stops strategically, these systems can reduce wait times and protect riders from heat exposure. Coordinated outreach can ensure that the most vulnerable residents are aware of and can access these services effectively.

Benefits

These emergency transit services can offer significant benefits during heatwaves by ensuring access to critical destinations, including cooling centers, healthcare facilities, and essential stores, for those without personal vehicles. By providing free or subsidized rides during extreme heat events, the city can reduce the risks associated with traveling on dangerously hot streets.The services can also be deployed for rapid evacuation or transportation to safe locations in emergencies, enhancing the city’s ability to respond effectively to heat-related crises. Ultimately, integrating these systems can foster resilience and equity, offering protection to those most affected by climate-related challenges.

Image Source: Smart Cities World.com

BUS SHELTER 2.0

The Consolidated Smart Shuttle System, the MBTA’s The RIDE, and the Age Strong Shuttle can be integrated into a comprehensive emergency transit network to support vulnerable populations during extreme heat events. While The RIDE and the Age Strong Shuttle already focus on individuals with mobility challenges and older adults, their reach can be expanded to include other atrisk groups, such as children and individuals with chronic conditions like asthma or heart disease. By utilizing real-time tracking apps and placing shaded or covered stops strategically, these systems can reduce wait times and protect riders from heat exposure. Coordinated outreach can ensure that the most vulnerable residents are aware of and can access these services effectively.

Benefits

These emergency transit services can offer significant benefits during heatwaves by ensuring access to critical destinations, including cooling centers, healthcare facilities, and essential stores, for those without personal vehicles. By providing free or subsidized rides during extreme heat events, the city can reduce the risks associated with traveling on dangerously hot streets. The services can also be deployed for rapid evacuation or transportation to safe locations in emergencies, enhancing the city’s ability to respond effectively to heat-related crises. Ultimately, integrating these systems can foster resilience and equity, offering protection to those most affected by climate-related challenges.

Cool Commercial Corridors

TREES are one of the most effective natural solutions to combat urban heat, providing shade, lowering surface temperatures, and improving air quality. In our community, streets like Columbia Road lack consistent greenery, leaving wide stretches exposed to heat. Similarly, many broad streets and vacant spaces have minimal shade, creating uncomfortably hot environments that could be transformed into cooler, more inviting areas with strategic tree planting.

Tree planting is a long-term process that requires careful planning, community trust, and ongoing feedback. A phased approach ensures the project is manageable, effective, and responsive to community needs. Starting with small-scale, safe locations such as medians, curbside parking spaces, and playgrounds allows us to test strategies and build momentum. Feedback from residents, combined with data from sensors monitoring cooling effects, will guide refinements for future phases. This step-by-step process helps establish trust, demonstrate benefits, and create a foundation for a larger, sustainable green network.

Pilot Phase: Small-Scale Testing

This phase focuses on testing tree planting strategies in safe, targeted locations like medians and curbside parking spaces. Sensors will track cooling effects, and community surveys will help refine approaches for broader implementation.

Expansion Phase: Integrating with Commercial and Community Spaces

Building on pilot successes, we expand efforts along Main Streets, near storefronts, and in pedestrian areas. Collaboration with businesses and community organizations ensures visible and impactful results, making green spaces a vital part of daily life.

Full Rollout: Community-Wide Green Network

The final phase establishes a cohesive green network, extending tree planting to private spaces such as residential courtyards and shared community areas. Long-term monitoring and maintenance will ensure the sustainability and effectiveness of this network.

COOL COMMERCIAL CORRIDOR

PLANTING TREES

Roadway Median

We will select medians that meet safety and planting conditions, especially along Columbia Road, where wide roads lack consistent greenery.Even planting small shrubs in these spaces can make a meaningful impact in mitigating heat and enhancing the streetscape. We will install sensors to monitor the impact.

Underused Curbside Parking Spaces

Imagine a hot summer day: cars parked on the street turn into ovens after just an hour, and pedestrians walking by feel like they’re melting in the heat. We aim to transform underused spaces, like those next to vacant lots or empty storefronts, into opportunities for greenery. By planting trees in these areas, we give them a chance to provide shade and reduce heat.

To ensure their effectiveness, we’ll install sensors to measure their impact and conduct surveys to gather feedback from the community about these changes.

BLUE HILL AVENUE TAP PHASE

2.0

Blue Hill Avenue Transportation Action Plan (TAP)

The plan represents a comprehensive effort to improve multimodal transit, safety, and accessibility in Grove Hall. It is part of the broader Safe System Approach to improve roadway safety while fostering equitable access and community development.

It includes plans to better crosswalks, sidewalks, and protected bike lanes and upgrade bus stops with improved amenities like seating, shelters, and better connections to commuter rail stations to encourage public transit use.

The plan targets issues like double parking and speeding and general improvements such as greenery, lighting, trash cans, and public art to create a welcoming environment.

Source: MBTA draft design upgrades at Blue Hill Avenue & Walk Hill St.

BLUE HILL AVENUE TAP PHASE 2.0

Nearly 40% of residents in Grove Hall rely on public transportation, and approximately 50,000 commuters traverse Blue Hill Avenue daily. Despite its critical role in mobility, complaints about traffic congestion and transit delays persist. The City of Boston’s ongoing Blue Hill Avenue Transportation Action Plan seeks to address these challenges by improving transportation infrastructure and quality of life along Blue Hill Avenue, from Mattapan Square to Grove Hall. However, this effort is geographically limited, leaving key areas in the North of the neighborhood underserved.

In terms of the existing bus network, there are 6 major bus lines running through the proposed area. Particularly, Line 22, 23, and 28 are more frequent, with 10-minute intervals. The bus lines runs past some major MBTA stations and connect Grove Hall and Mattapan to the Center Boston.

To ensure a broader impact, we propose the City launch Phase 2 of the Blue Hill Avenue initiative. This expansion would extend the dedicated bus lane along Warren Street in Grove Hall to Roxbury Crossing on Columbus Avenue, connecting to the updated Orange Line.

BLUE HILL AVENUE TAP PHASE 2.0

Extending the transportation action plan to include dedicated bus lanes and promote biking and walking is essential for a more efficient and equitable system. Improving bus efficiency, especially on Routes 23 and 28, through dedicated lanes will reduce delays, enhance reliability, and encourage public transit use. Additionally, better connecting Grove Hall and Mattapan residents to the MBTA’s Silver and Orange Lines will improve access to jobs, education, and services, addressing transit inequities in underserved communities.

This alignment complements the Neighborhood Slow Streets Program, which focuses on traffic calming, safer crossings, and reduced speeds within residential areas like Grove Hall. Extending the bus lane would reinforce these safety and accessibility goals by integrating slow street principles with enhanced transit infrastructure, benefiting pedestrians, cyclists, and transit users alike.

The plan also aligns with the Cool Commercial Corridor initiative by incorporating cooling features like shaded bike lanes, tree-lined sidewalks, and pedestrian-friendly spaces. These improvements will make walking and biking safer and more comfortable while supporting climate resilience and livable urban spaces. In summary, these updates will enhance transit efficiency, connectivity, and sustainability, benefiting both residents and the environment.

BLUE HILL AVENUE TAP PHASE 2.0

Before

After

SUMMARY

Despite the importance of public transit, traffic congestion and transit delays remain ongoing issues. The City of Boston has a number of initiatives that seek to improve infrastructure and quality of life along the corridor from Mattapan Square to Grove Hall but excludes underserved northern areas.

To address extreme heat challenges, we are proposing Bus Shelter 2.0 which includes the following features:

Drinking Water and Misting Stations: Providing hydration and cooling amenities at transit stops.

Heat-Resistant Materials: Incorporating thermally insulated, slip-resistant seating and flooring.

High-Priority Locations: Targeting high-ridership areas like Grove Hall Plaza and Blue Hill Avenue.

Maintenance: Regular upkeep and sensor-triggered alerts for functionality.

Local Artwork Integration: Reflecting Grove Hall’s culture through murals and mosaics.

Additional Cooling and Streetscape Enhancements include

Roadway Medians: Planting shrubs along wide, barren streets like Columbia Road to reduce heat and enhance greenery, with sensors to monitor impact.

Underused Curbside Parking: Transforming underutilized spaces near vacant lots or empty storefronts by planting trees for shade and cooling. Sensors and community surveys will evaluate effectiveness and gather feedback.

These initiatives aim to improve transportation infrastructure, mitigate urban heat, and foster community well-being Greater Grove hall.

Photo taken by Team Members

Photos taken by Team Members

Improve Land Use Patterns

As with the infrastructure discussed in the previous chapter, land use patterns and regulations greatly shape the way a neighborhood looks and feels to residents, especially during periods of extreme heat. It is important then to make sure future land use changes in Grove Hall are made with extreme heat in mind. Grove Hall contains a large amount of vacant land and paved surface parking, land uses that could be repurposed to provide cooling spaces while meeting other community needs such as affordable housing.

Vacant Land in Grove Hall

Based on the City of Boston’s Fiscal Year 2024 property assessment data there are over 120 acres of vacant or underutilized land, both privately and publicly owned, in the Greater Grove Hall neighborhood. These include parcels that are used as paved parking and yards for adjacent buildings, as well as parcels that are not in any active use, left vacant either due to a lack of investment or because they are undevelopable in their current form, due to zoning regulations or lack of utility access. Several lots in Grove Hall of the latter type are owned by the City of Boston, typically through the foreclosure on tax-delinquent properties.

There are also many formal surface parking lots in Grove Hall. Gardens and park space help mitigate the urban heat island effect, while paved surface parking lots significantly contribute to it, and many of these lots are clustered in commercial areas experiencing the greatest heat island effect. At the same time, unpaved vacant private lots, while not contributing to urban heat island effect, are often fenced off and inaccessible to community members as a cool outdoor space. The City of Boston should pursue a policy to use these lots as community assets, to balance different community needs in Grove Hall.

Left: Vacant Lot in Grove Hall (Source: Team Members). Right: Vacant Parcels and Surface Parking in Grove Hall, over Urban Heat IslandEffectIntensity(Source:BostonAssessingDepartment).

CURRENT CITY PROGRAMS

Source: City of Boston

The City of Boston has some recent and ongoing programs for redeveloping vacant land.

The Citywide Land Audit, conducted in 2022, was a comprehensive audit of all municipallyowned properties in Boston. This identified 218 acres of vacant or underutilized land (such as parking lots), which the City is proposing for infill development of affordable housing and other community and commercial uses (City of Boston, 2023). This represents only a fraction of Boston’s vacant land though, and a similar audit of privately held vacant parcels in Grove Hall would be useful.

Building off of the Land Audit, the City has started the Welcome Home Boston program to transfer city-owned parcels to developers to “fast track the production of new affordable homes” in Grove Hall and other parts of Boston (City of Boston, Sep 2024). The program is currently split into four phases, and the City is in the process of selecting developers. The new homes are to be affordable to “families with incomes below 80% and 100% of the Area Median Income (AMI)” as well as

LEED Gold Certified and compliant with EPA Energy Star standards. Affordability remains a concern with this new housing though. While 80% and 100% of Boston’s AMI for a family of four are $148,900 and $130,250 respectively, Grove Hall families have a median income of $60,271, less than half of the 80% limit, while renting households have a median income of only $30,279.

The Blue Hill Avenue Action Plan is another City-run program to transfer municipally-owned vacant parcels along Blue Hill Avenue for redevelopment, to boost economic activity along this commercial corridor, both in Grove Hall and further south in Mattapan (City of Boston, May 2024). Like Welcome Home Boston, the project is being split into phases led by different developers. This currently includes just two parcels in Grove Hall (as part Phase B2) at Blue Hill Ave and Charlotte and Ellington Sts. As of writing plans for these parcels have not been finalized.

Top: "Areas of Interest" from Boston's Open Space and Recreation Plan: Areas that the City has determined from its own analysis and community input to be lacking in access to sufficient open space for residents. (Source: City of Boston).

03-01 GREEN SPACES

Using data from the City of Boston’s Open Space and Recreation Plan, 20232029, we identified areas within the neighborhoods of Roxbury and Dorchester that exhibit limited access to green spaces. The City’s walkshed service area map highlights the eastern section of Grove Hall as having particularly low accessibility compared to surrounding areas. Site documentation revealed a concentration of vacant lots in this area, particularly along Blue Hill Avenue. These lots present a unique opportunity to address the community’s lack of green space while addressing issues of neglect and illegal dumping.

Increasing Green Spaces

Vacant lots can be transformed into functional green spaces, such as pocket parks, community gardens, or urban farms. This approach repurposes underutilized land while enhancing the neighborhood’s environmental quality. These green spaces can mitigate urban heat by reducing surface temperatures, improving microclimates, and minimizing airborne dust. Furthermore, they provide essential areas of respite for pedestrians and residents, fostering a sense of well-being. Urban farms, in particular, serve the dual purpose of improving environmental conditions and contributing to food security for low- and moderate-income families by providing access to fresh produce and reducing household food expenditures. These spaces create a foundation for more sustainable and equitable urban environments.

Community Engagement and Pop-Up Events

The proposed pocket parks can also serve as hubs for community engagement, offering a venue for programming and events designed to strengthen social ties. Pop-up events with shaded seating and cooling infrastructure can provide relief during periods of extreme heat, offering spaces for residents to gather safely. Additionally, these green spaces can be used to distribute relief packages, supplies, or other forms of assistance during heatwaves or other emergencies. By fostering connections among residents, these parks can help establish networks of care for vulnerable community members, creating a more resilient and cohesive neighborhood.

Broad Community Needs in Grove Hall

BALANCING HEAT RESILIENCE AND COMMUNITY NEEDS

While converting some vacant lands to pocket parks is necessary, Grove Hall is in desperate need of other land uses to address community needs. Like the rest of Greater Boston, Grove Hall is facing a crisis of affordable housing. As a result of rising demand, housing vacancy declined by almost 50% between 2010 and 2020, even as the number of units has increased by 21%. While homeowners benefit from increases in housing prices, renters are vulnerable to displacement. Over 72% of Grove Hall households are renters, of whom about one third are severely rent burdened (American Community Survey, 2022). While new park space is important, it needs to be balanced with increased affordable housing to stop the displacement of longtime residents. In addition, there is a need for other community assets, per Greater Grove Hall Main Streets (2024), including daycares, senior care facilities and off-street parking along Grove Hall’s commercial corridors .

ACCELERATE COMMUNAL DEVELOPMENT AROUND PARK PROJECTS

Boston should expand its existing land dispossession programs such as Welcome Home, Boston particularly around the proposed pocket park developments to meet community needs and ease concerns about potential green gentrification. In its request for proposal process, the City should give preference to mixed use development projects that include accessible units, senior accessible units and expressed community needs such as daycares. Preference could also be given to projects incorporating simple communal cooling resources such as shaded public courtyards, water fountains, awnings or misting stations.

IMPLEMENT POLICY TO ENCOURAGE VACANT LOT REDEVELOPMENT

The city should create incentives to encourage the development or productive use of vacant lots and paved parking areas. The city could levy new fees on vacant lots to encourage their owners to bring them into productive use. These fees could be waived if landlords agreed to improve lots into pocket parks up to city standards until they are ready to be developed. Fees could similarly be waived on parking lots if they are improved to incorporate permeable pavement and shade structures.

The city could also provide grants to support the development process of lots held by nonprofit organizations such as the 14 Grove Hall vacant lots held by religious organizations (City of Boston Property Assessment, Sep 2024).

Top : Proposed use of vacant lots in a high vacancy area along Blue Hill Ave. As three lots are developed into pocket parks along this commercial corridor, the city could distribute its remaining holdings to affordable housing developers. One lot is reserved for commercial corridor customer parking and would incorporate permeable pavement and shade structures.

ZONING AND LAND USE CHANGES

The kind of development that is needed on these lots will still need to contend with Boston’s land use regulations. Boston has a complex and restrictive zoning code that makes building new housing difficult, further contributing to the displacement of residents as housing costs rise. A 2023 report by the Boston Planning & Development Agency found that, with 3,800 pages and 429 districts, Boston’s zoning code is far longer and more complex than those of American cities of comparable population (Bronin, 2023). Grove Hall is fragmented by a patchwork of different zoning districts, especially for residential areas. There are also large minimum lot sizes (as high as 7,000 square feet in some areas), extensive off-street parking requirements, and limited mixeduse zoning along commercial corridors (BRA, 2024). These sorts of restrictions make any sort of development difficult and expensive, discouraging additional investment in heat mitigation design features. Minimum parking requirements in particular contribute to more paved surface parking, a major contributor to the urban heat island effect. Additionally, as a result of zoning restrictions, 547 undeveloped lots in GH are labeled unusable by the Boston Assessing Department as they are too small for the zoning district that they are located in.

On top of this, green building and site design standards in Boston’s zoning code are generally reserved for the largest developments. These include Articles 37 (Green Buildings) & 80 (Development Review and Approval), which only apply to projects of greater than 50,000 and 20,000 square feet, respectively (BRA, 2024). Additionally, more focus is needed on heat mitigation features. The Heat Resilience Solutions for Boston plan notes the lack of attention to heat in the Article 80 regulations.

Top: Roxbury Neighborhood Zoning Map (Source: City of Boston). Bottom: Comparison of the number of zoning districts in Boston and similarly-sized cities (Source: Bronin/Boston Redevelopment Authority).

Top left: The Clarion, Blue Hill Ave. Source: The Community Builders, Inc. Bottom left: Rooftop Farm in Dorchester. Source: Recover Green Roofs

ZONING AND LAND USE CHANGES

LEVERAGING DEVELOPER INCENTIVES

Developer incentives can be used to promote heat mitigation features in new construction by allowing exemptions from Boston’s strict and complicated zoning. These exemptions could include increased allowed density or reduced parking minimums in exchange for the developer building heat mitigation features such as street trees, reflective and/or green roofs, porous pavement, and shaded public plazas for larger parcels. By allowing greater density and speeding up the permitting process, these kinds of incentives will help offset costs of installing heat mitigation infrastructure. Such practices are common in other northeastern cities. This includes New York City, where in some areas density bonuses are awarded for including public plazas in new developments (NYC Planning, n.d.), while Philadelphia awards density bonuses for installing green roofs (Philadelphia Water, 2024).

Properties in the CMX-2 and CMX-2.5 zoning districts are eligible to use the Green Roof Bonus as provided in Section 14-602(7) of the Philadelphia Zoning Code. The Green Roof Bonus allows property owners to increase the amount of allowable residential units by 25%. To illustrate, if the Philadelphia Zoning Code allowed for 20 residential units as a matter of right, under the Green Roof Bonus, the property owner could include another five (or a total of 25) residential units with the inclusion of such a green roof. To be eligible for the bonus, the dwelling units must be located in a building with a green roof, which covers at least 60% of the rooftop. For new buildings, the building structure’s construction requires a minimum of 5,000 square feet of earth disturbance as determined by the Philadelphia Water Department (PWD).

Source: Density and Dimensional Bonuses Allowed for Mixed-Used Properties Under the Philadelphia Zoning Code by Alan Nochumson P.C. Real Estate Developer

Green Roof in Philadelphia (Source: Philadelphia Water Department)

ADDING HEAT MITIGATION REQUIREMENTS TO THE ZONING CODE

The city could also add heat mitigation requirements directly into the zoning code. This could include site requirements for elements like trees, shade structures, cool roofs , and reflective pavement, as seen in the nearby cities of Cambridge and Somerville (see Case Studies on the right). In Boston these sorts or regulations could be written into a new heat resilience overlay district (as recommended in Heat Resilience Solutions for Boston) or added on to Articles 37 and 80 with expanded coverage for smaller developments. To increase flexibility for smaller developments, heat mitigation requirements could be used as optional standards to determine developer bonuses under a certain land area threshold.

ZONING AND LAND USE CHANGES

CASE STUDIES FROM CAMBRIDGE AND SOMERVILLE, MA

ZONING CODE REFORM

Ultimately, zoning is one of the main shapers of Grove Hall’s built environment, and in the long term true zoning reform should be pursued to build a neighborhood that is more resilient to extreme heat. First, a new Boston zoning code should reduce and simplify minimum lot sizes while consolidating residential zones, speeding up the permitting approval process and lowering the cost of development, offsetting the cost of heat sensitive design in affordable housing construction. Next, the new code should reduce minimum parking requirements, reducing the amount of impervious paved surface that greatly contributes to the urban heat island effect. Finally, it should allow more mixed use along commercial corridors, reducing the distance residents will have to walk in the heat to access local services and businesses and reducing the need for automobile travel in the neighborhood, a crucial contributor to the urban heat island.

The zoning code in Cambridge, MA requires reflective roofs in large developments and uses “cool scores” which can be met with site elements like tree canopies, green roofs and walls, and other vegetation. The Somerville, MA code also requires reflective roofs under its Heat Island Reduction section. Like the Cambridge code, Somerville also includes a “green score” for all new construction, with minimum thresholds for particular building types. This includes similar components to the Cambridge code, including those that help reduce temperatures like vegetation, pervious paving, and green roofs (MAPC, n.d.).

Cool Factor Score Sheet (Source: City of Cambridge)

SUMMARY

One major land use issue facing Grove Hall is a high concentration of vacant lots. In the short term, many of these lots can be re purposed as pocket parks and other forms of public open space. These new spaces can help cool residents and reduce surrounding temperatures during periods of extreme heat while also providing sites for community programming.

The need for new open space must be balanced though with local needs for more affordable housing and other amenities, and future development on Grove Hall’s vacant lots must take all of these things into consideration. New policies should be introduced to spur redevelopment, with heat mitigation as a major priority.

In the long term, changes to Boston’s complex zoning code are needed to ensure a built environment that is more resilient to extreme heat. On the one hand, this can include added developer incentives to promote the installation of cooling infrastructure in new developments, such as trees and reflective roofs, as well as more explicit requirements for heat mitigation in the zoning code. On the other hand, comprehensive zoning reform should be pursued to ensure long-term heat resilience and a reduced urban heat island effect while making redevelopment of vacant lots easier. This would include reducing minimum lot sizes and simplifying residential zoning, reducing minimum offstreet parking requirements, and allowing more mixed-use development.

Photo taken by Team Members

Photos taken by Team Members

Improve Social Cohesion

Building upon the technical insights on infrastructure improvements and land use modifications for heat mitigation, this chapter shifts focus to an often underutilized yet impactful resource in Grove Hall: its community. As highlighted in earlier analyses of heat impact patterns and the demographic characteristics of Grove Hall, the neighborhood faces significant vulnerabilities to extreme heat. These challenges disproportionately affect seniors living alone, younger populations, households without access to air conditioning, and outdoor workers. Despite these vulnerabilities, Grove Hall’s strong social cohesion and existing community networks offer valuable opportunities for the development and implementation of innovative, community-driven solutions.

Limitations of Current Approaches

Thecity’s heat emergency response is multifaceted and looks at multiple different pathways to provide relief to communities during heat waves. While there is an emphasis on community involvement through the Looking Out For Neighbors and Awareness, Education, and Training chapters of Boston’s Heat Resilience Plan, neither of them fully address the necessity to improve social cohesion across entire communities. A con-tributing factor to heat-related deaths is social isolation and the lack of communication/ support across entire communities. This is a community necessity that requires integrative approaches that touch on the root issues behind the isolation/distance between community members. While existing facilities offer basic amenities such as air conditioning, water, and shade, their emergency-only ope-rational model fails to address the community’s broader resilience needs.

Proposed Solution: Expansive Resilience Centers

We recommend transforming the traditional cooling center approach into a comprehensive community hub system. The current cooling centers are effective in providing immediate cooling relief during extreme heat waves, whether through official public buildings being turned into cooling centers or through the creation of pop-up centers. In order to turn this into a com-prehensive hub system for the entire community there are further developments that need to be made in terms of physical infrastructure as well as in the programming that is available to residents.These resilience centers would:

TRANSFORM EXISTING RESOURCES

-Identify existing areas of community gathering (libraries, malls, youth centers, daycares, senior centers, etc.)

-Develop a way for these areas to be transformed into fully stocked and prepared cooling centers during heat waves:

Funding from March through September to stock up care supplies (monthly installments

Train staff in how to prepare for these events and how to handle the influx of people

Consult healthcare professionals on the viability of using existing infrastructure as cooling centers

Hold meetings for healthcare professionals, [heatwave researchers], and frontline staff to discuss best ways for communal care during heatwaves.

PHYSICAL INFRASTRUCTURE

-Operate year-round as permanent community spaces

-Provide multi-functional areas integrating cooling with other services

-Incorporate flexible spaces for varying community needs:

This specifically is critical to include because one of the issues Ed Gaskin pointed out during our Grove Hall tour was that when standard community centers or YMCA centers are converted into cooling centers for all populations, the original programming for children usually has to be cancelled to make space for the higher capacity and for safety reasons as well. Alongside several youth development programs, YMCAs also provide child care services which is an essential service for working parents that they’re no longer able to access in extreme heat waves, a decision that has a resounding impact through their financial, physical, and emotional health.

It’s necessary to counter the loss of community programming even in extreme heat waves because not doing so leads to the loss of function in already struggling communities. One way to address this is to have a wider range of cooling centers that each have designated sections for different age ranges or different programming. Having specific spaces for different age groups allows for each one to be accommodated as necessary without losing space for any one group. This foresight and organization would also allow for the centers to prepare resources accordingly.

RESILIENCE CENTERS

The Red area are less accessible to the resilience centers, where residents might need to walk around 10 min to the locations.

PROGRAMMING

-Offer job training and professional development

-Provide public WiFi access

-Host recreational and educational activities

-Deliver health services and monitoring

The Urban Farming Institute Model Adaptation

CASE STUDY FROM DORCHESTER

CASE STUDIES

Inspired by the successes of Dorchester’s Urban Farming Institute, we recommend adapting and implementing this model in Grove Hall. By tailoring its key components to the unique needs of the neighborhood, this initiative could serve as a powerful tool for addressing heat resilience while fostering social cohesion and economic opportunity.

Dorchester’s Urban Farming Institute provides an exemplary model of how urban agriculture can address environmental, economic, and social challenges in vulnerable communities. This initiative combines sustainable farming practices with community engagement to foster resilience and em-powerment. By transforming underutilized urban spaces into productive farms, the Institute has created a framework that integrates environmental stewardship, job creation, and education.

Source: Urban Farming Institute

The Heat Team Structure

To ensure successful implentation, we propose establishing a "Heat Team" in partnership with Greater Grove Hall Main Streets (GGHMS). This structure would include:

The foundation of this approach centers on rotating block leadership roles, which ensures fresh perspectives and prevents volunteer burnout while building leadership capacity throughout the neighborhood.

To celebrate and encourage ongoing participation, we propose recognition programs including “Block of the Month” and “Heat Heroes” awards, highlighting exemplar y community service and innovative solutions.

Youth engagement will be fostered through a Junior Heat Team initiative, creating pathways for young residents to become future community leaders while helping with current heat resilience efforts.

To encourage the youth to participate in these efforts, this program could marketed through schools and paired with a variety of beneficial programs such as Main Streets and BCYF.

Regular community feedback sessions will ensure the program remains responsive to neighborhood needs and provides opportunities for continuous improvement. Additionally, we’ll offer emergency response certification opportunities, building professional skills while strengthening our community’s emergency preparedness capacity.

Communication and Education: Bridging Knowledge Gaps

WhileBoston currently maintains an emer community lacks structured educational programming about extreme heat risks and responses. To address this gap, we propose developing inclusive educational initiatives that reach all community members through multiple channels and approaches. These educational programs will be supplemented with hands-on training sessions where residents can practice emergency response protocols and learn to use cooling resources effectively.

Our EDUCATIONAL STRATEGY includes:

Age-specific workshops tailored for children, seniors, and families

Digital learning platforms offering flexible online modules

Practical training on identifying heat illness symptoms

Training to understand how heat can combine with other illnesses to show/hide certain symptoms

Multi-language resources ensuring accessibility for all residents

Partnering with cultural centers to spread resources in multiple languages

Mottos, slogans, easy to understand graphics that pop out and allow viewers to learn short, quick facts on what to do in a heat wave

Acquire funding to advertise graphics/workshops/ trainings on social media platforms for people in the area

Emergency Communication: Building on Existing Systems

We’llstrengthen and expand upon the existing Boston emergencyhot line system by integrating it with our local community networks and the newly formed Heat Team. Also, we’ll cooperate with Office of Emerging Technology in City of Boston to get more accurate data of daily temperature comparing to the temperature data from sensors in Logan Airport.

We propose that the Heat Team will conduct door-to-door wellness checks on vulnerable residents during extreme heat events, with trained volunteers ensuring our seniors, disabled neighbors, and others at high risk receive direct support and information. Block leaders will serve as direct communication channels during emergencies, ensuring information flows quickly and effectively throughout the neighborhood. This connection will enable more targeted and timely updates about neighborhood-specific heat mitigation efforts, ensuring critical information reaches every Grove Hall resident through channels they already trust and use.

Enhanced use of Boston's existing emergency hotline

Door-to-door wellness checks by Heat Team volunteers

Real-time alerts through Heat Team block leaders and community networks

Regular updates on local cooling center locations and hours.

This case study provides a compelling example of how coordinated, accessible programs can address the immediate health impacts of extreme heat, particularly for vulnerable populations. Grove Hall could benefit from a similar initiative tailored to its unique community needs, potentially in conjunction with broader efforts like urban farming or expanded community networks.

CASE STUDY FROM PHILADELPHIA

CASE STUDIES

In Philadelphia, the “Heatline” program serves as a direct communication channel for residents during extreme heat events. The Heatline is operated by the Philadelphia Corporation for Aging (PCA) and staffed by medical professionals and social workers. It provides information on staying cool, offers medical advice, and directs residents to nearby cooling centers. During extreme heat events, the Heatline receives thousands of calls, particularly from older adults and vulnerable populations.

Source: Safety & emergency preparedness, City of Philadelphia

Supporting Vulnerable Populations

“

Sometimes a lot of people that are homeless like myself, they feel left out, because they feel like they are invisible that they don't count. They don't matter. "

-Kennan Parish, interviewed by Arizona State University for the Jenny's Trailer Project

Special

attention must be paid to vulnerablecommunity members, particularly those experiencing homelessness, who face heightened risks during extreme heat events. Our community is only as resilient as our most vulnerable neighbors, and we must ensure our heat response strategies are accessible to all. To achieve this, we recommend:

01 Implement mobile cooling centers based on successful models like Jenny’s Trailer in Tempe, Arizona. This initiative, led by someone with lived experience of homelessness, demonstrates how mobile solutions can effectively serve those who may not access traditional cooling centers due to concerns about pets, belongings, or institutional settings.

02 Public ice water stations in strategic locations, particularly in areas identified through our heat mapping as high-risk zones.

03 Reduce barriers to cooling center access, such as identification requirements and limited operating hours, making these vital resources more accessible to everyone who needs them.

04 Support local shelters with funding and resources to extend their daytime hours during heat events, providing consistent and reliable cooling options.

These interventions will be regularly evaluated and adjusted based on community feedback and usage patterns to ensure we're effectively meeting the needs of our most vulnerable residents.

Figure: Jenny’s Trailer -mobile cooling center.

City of Tempe

Supporting Vulnerable Populations

Buildinga strong and sustainable heat resilience program requires us to tap into Grove Hall’s existing network of resources. Local businesses, especially established community partners like Stop & Shop, can play a crucial role by sponsoring neighborhood cooling stations, offering immediate relief points throughout the neighborhood. By partnering with local healthcare providers, we can enhance our heat response with preventive care services and health screenings during extreme weather events. Educational institutions will be vital partners in developing and delivering training programs that build longterm community capacity for heat resilience.

This partnership mindset is also necessary when trying to implement some of the solutions we’ve provided here. For example, when it comes to building Community Integrated

Resilience Centers, it is essential to take into account the work that existing organizations have already done. One such organization is CREW (Communities Responding to Extreme Weather).

CREW has built a national network of 109 resilience hubs in college campuses and community libraries, including in Boston. While a couple resilience hubs border Greater Grove Hall, at the moment there are none within our site area. CREW would be a key connection and resource through actual implementation as well as working off of their model. Workers at CREW also distribute cooling kits and free air conditioners, hold public education sessions about local climate impacts, and encourage neighbors to check in on the elderly.

Considering their experience in community building actions as well as their previous work in Boston, it would significantly improve and speed up the impact of our solutions if we involved

them in our planning and progress.

Partnering with local cultural organizations and religious institutions could also be incredibly beneficial. Religious organizations are generally the wealthier nonprofits across the globe, and have a history of contributing to local communities either through food drives, donations, or providing homeless services/ shelters.

Boston alone has several different churches, services, and partnerships that focus on providing emergency relief, care centers, and home-lessness services. Boston’s religious institutions have also worked to gether before in significant ways to provide services to those in need. In October 2014 the abrupt closure of Long Island Bridge left over 700 people without access to the city’s largest complex of public and privately-funded ser-vices for people who experience homelessness

and addiction. This came right before Boston’s snowiest winter on record (over 108 inches of snow). In response to this crisis, religious leaders from 65 different institutions came together to launch a collaboration called Boston Warm in which two churches provide emergency relief day centers every day throughout the winter. One of these churches remains open yearround to provide a non judgemental space and resources for people who are unhoused. There are existing case studies within Boston alone of the impact religious organizations can have. Partnering with them in the case of heat related issues can help further the reach of our efforts as well as serve as another way of communicating the information that is necessary to survive the increasing urban heat.

Grove Hall faces critical challenges related to extreme heat. Vulnerable populations include seniors living alone, households without air conditioning, outdoor workers, and younger residents. Social isolation is a significant factor in heat-related deaths. Current strategies, such as cooling centers, provide shortterm relief but are limited in scope. These centers often disrupt essential services, such as child care, and fail to address broader community needs.

The proposed solution includes the development of resilience centers that function year-round. These centers would provide multi-func tional spaces, offering cooling services alongside job training, health care, recreational activities, and public Wi-Fi. Dedicated areas for different age groups would ensure that existing programs continue without disruption. A “Heat Team” would be established to perform wellness checks, facilitate communication during emergencies,

SUMMARY

and support neighborhood-level heat resilience.

Case studies from Dorchester and Philadelphia offer valuable insights. Dorchester’s Urban Farming Institute integrates urban agriculture with job creation and community engagement. Philadelphia’s Heatline program provides medical advice and cooling center referrals for vulnerable residents during extreme heat events. By adapting these models, Grove Hall can strengthen its heat resilience and promote long-term community wellbeing.

Figure: Grove Hall, Boston Public Library

Close Policy Gaps

Boston has taken significant steps to enhance energy efficiency and sustainability through progressive building codes and incentive programs. However, policy gaps remain in ensuring equitable access to energy-efficient solutions and bridging the divide between mandated standards and practical implementation. Addressing these gaps,particularlyinareaslikemodernroofingsystemsand renewable energy integration, is crucial for achieving comprehensive environmental and economic benefits while ensuring all communities can participate in and benefitfromsustainablepractices.

Winter Heating Regulation

Winters were traditionally the focus of energy regulation across a state known for historically frigid temperatures and high annual snowfall. Due to this legacy, Massachusetts’ General Code and State Sanitary Code is robust in regulating heat during the colder months, spanning September through May, with a focus on November through March of t he next calendar year.

CURRENT STATE CODE

The State of Massachusetts and City of Boston additionally provide several means of financial assistance for heat related utilities during cold weather months. Boston ABCD, a city-partnered community development non-profit, builds upon federally-backed heat assistance by helping residents cover their winter heating bills and working with utility providers. The State of Massachusetts also provides the HEAP (Heating and Energy Assistance Program) to also provide assistance in covering winter heating costs, with eligibility based on income and household size. Critically, the program is also accessible to renters.

PHYSICAL INFRASTRUCTURE

State Sanitary Code 105 CMR 410 Minimum Standards of Fitness For Human Habitation includes multiple provisions related to heat, including requirements for residential temperatures to be above 64 F at night, and 68 F during the day, without exceeding the upper threshold of 78 F. It also protects the occupants' right to file complaints and request inspections due to a lack of heat, provides a 24hour timeframe to correct any issue relating to heat, and bars the use of space heaters to meet the State's heat requirements. Other provisions within the code outline temperature requirements for workplaces, restrict utility companies from shutting-off service between November and March of the next year due to financial hardship, and provide greater protections for infants, the elderly, and those with chronic illnesses.

EXPANDING POLICY FOR EXTREME HEAT

ADAPTING CODES FOR EXTREME HEAT

Current General Law and State Sanitary Codes that provide greater protection during the colder months can be expanded or adapted to address extreme heat. Expansion of Massachusetts State Sanitary Code 105 CMR 410 could include upper-temperature thresholds during warmer months to ensure that housing units remain at safe temperatures during extreme heat events. Likewise, Massachusetts General Law Chapter 164 and State Sanitary Code 220 on utility shut-offs for vulnerable populations can be expanded to include the warmer months or applied during heat advisory events.

EXPANDING UTILITY ASSISTANCE

Utility Assistance programs, such as those provided by Boston ABCD, currently geared towards colder weather, can be expanded or created to provide parallel services during the hotter months, dependent on funding. Current assistance programs are dependent on federally-backed funding, and any new policy to address the utility burden from heat would need to find a dedicated funding source from the State or City.

IMPLEMENTATION