INNOVATION IN OPEN SPACE

A Study of Innovations in Open Space from Secret Gardens to Enclosed Reserves, Corner Block Parks to Communal Open Space, Community Gardens to Urban Orchards through to Urban Bush or Biodiversity enclaves – what are the criteria that drive success or failure of these spaces?

ARLA 4506 Research Strategies in Landscape Architecture, Urban Design and Architecture Research Proposal Student: 19008890_Quinlan

Image Credit : Brennan , Bede. 2023. “An Adaptive Attitude: The Roundtable.” Landscape Australia . June 20, 2023. https://landscapeaustralia.com/articles/an -adaptive -attitude -the -roundtable/

1 1. CONTENTS 2. ABSTRACT 2 3. INTRODUCTION 2 4. OBJECTIVES 3 5. RESEARCH QUESTION 3 6. BACKGROUND 3 7. LITERATURE REVIEW 4 7.1 Cultural 4 7.2 Social 5 7.3 Economic 6 8. METHODOLOGY 7 Stage 1: Space, Culture & Context 7 1.1 Desktop Review – Case Studies 7 1.2 Observation – Spatial Activity Heat Mapping 8 Stage 2: Establishing The Indicators For Comparison 8 Stage 3: Testing Perceptions & Attributes 8 3.1 Sample 8 3.2 Recruitment 8 3.3 Instrument 8 3.4 Analysis ................................................................................................................................................................................................... 9 Stage 4: Reporting 9 9. CONCLUSION 9 Appendix 1: Case Study Tables 10 Table 1: Examples of Enclosed Reserves 10 Table 2: Examples of Radburn Plan Reserves 11 Table 3: Examples of Traditional POS, Liveable Neighbourhoods and Community Gardens 11 Appendix 2: Comparative Indicators .................................................................................................................................................. 12 Table 4: Indicators & Measurement Criteria 12 10. REFERENCES 13 11. CASE STUDY REFERENCES 16 Report Word Count: 3,778

2. ABSTRACT

Open space is defined in general, planning and policy terms as the absence of built form, or developed for use other than agriculture. This definition implies that it is a left-over space that serves no productive value, yet the literature demonstrates that there is a value for society and community in having functioning open space for a multitude of purposes. This study aims to consider this value, the drivers, the perspectives, and the purpose of open space to challenge the current town planning policies across the Western world that stipulate a required blanket 10% margin of Public Open Space (POS)

It aims to investigate the cultural, social, and economic drivers of those who have a symbiotic relationship with the space adjacent to their homes and workplaces. It asks what does success look like? And what are the factors that drive this perceived success?

The methodology proposed investigates the historical and cultural context around 25 Australian and International high-profile examples of urban or suburban open space via a descriptive desktop review, human movement and activity within each space illustrated via heat maps, establishment of a set of socio-demographic and economic indicators to consider similarities and differences across a set of indices, and a perception survey to model and correlate preferences, drivers of perceptions of innovation and desirability, and factors or themes generating success or failure.

The findings of this study will be presented to the WA Planning Commission to assist in the development of future POS policy, local LGA guidelines and assessment of governance decisions rating to shared and communal open space.

3. INTRODUCTION

Any city is an “agglomeration of countless individual units” (Farrell, E, 2023, 2) drawn together by cultural, economic, environment and physical factors. Open space is one such unit in the agglomeration, drawn by different spatial matrices from piecemeal to pragmatic.

Consideration of open space starts at the “void” an “absence of build” that creates the premise that space is “an emptiness from which anything is possible” (Koolhaas, 1985). The theory of space points us to the base question of whether space is a perceived asset for which a community can project their aspiration and shared sense of belonging, a space with a set of predetermined rules for use, or perhaps a nothing space – a green wasteland that disconnects, creates feelings of insecurity, scrutiny, discomfort or fear, and forces abandoned retreat behind our fences.

Since the turn of the century, our urban communities have been developed with a generic space application known as Public Open Space (defined by an area equating to 10% of an overall urban or suburban development). A spatial definition applied to a plan, yet its intent is to generate social, economic, and green infrastructure benefits that cannot be seen from the green square on a spatial map

Delivering successful open space is not just a question of aesthetics, or utopian environmental determinism, rather a desire to reduce wasted investment in underutilised barren corner parks, reduce community isolation, disparity, and disconnection, provide greater equitable access to green liveable spaces, address urban heat, improve biodiversity, and water conservation. A more innovative approach to open green space has the potential to deliver to each of these, while potentially providing more productive spaces of shared urban food production, shared facilities, and a greater efficiency in resource use.

2

4. OBJECTIVES

This study considers the existing literature and case studies to propose an academic investigation into the classification and considerations of open space, with the objective of:

• Investigating whether we can achieve better utilisation of shared space within our community, including whether it is possible to shift a perspective of individualistic private land ownership or “possession” to a communal “shared custodianship” in relation to public or private outdoor suburban or urban spaces

• Considering if there is innovative use of backyards and public green space that could provide better urban biodiversity and community outcomes, particularly whether large pockets of space could be repurposed to create productive gathering spaces for people and experiences, rather than programmed activity for individuals, dogs, or children

• Determining what factors could predict the success of a different functioning or designed open space through consideration of the cultural, economic, and social context of those who have the “symbiotic ownership” over the spaces adjacent to their dwellings.

5. RESEARCH QUESTION

The proposed research question guiding this research proposal is:

“What could innovation in shared open space look like if it took into account the cultural, economic and social drivers of those using, or living, adjacent to the space?”

6. BACKGROUND

In July this year, the Western Australian Planning Commission released a new Operation Policy to update the Planning for Public Open Space (POS) Guidelines to public comment. The Property Council of Western Australia, representing the development industry, responded to these guidelines suggesting they were an “ill-considered and unjustified tax on development” that would “further diminish the delivery of much needed new housing stock in WA.” The arguments put forward relate to underutilisation of existing POS, maintenance (which is argued should be appropriately funded by rate revenue not the developer), contribution of a new development to the existing rate base, and a link to a changing demographic generating demand for POS, rather than it being triggered by a new development or increase usage of open space. The cost analysis put forward as evidence for these arguments are solely economic and relate to financial opportunity, contribution, and cost scenarios (WAPC 2023, Property Council 2023).

This tension between components of the Liveable Neighbourhoods Policy, developers, market, and economic drivers in the delivery of open space is considered in the local Wungong LSP case study. Academics Bolleter 2022 and Weller 2008, both note that ‘blind’ application of generic POS standards, without accounting for the landscape, socio-demographic composition, preference, and human, as well as non-human, needs is fraught.

Particularly if the intent of the policy is to deliver POS that meets the needs of a greater mix of housing types, meets community needs and achieves the “desired recreational, amenity, health, cultural and environmental outcomes for the whole community” (WAPC 2023), answer will not be found in a generic 10% of marginal left over space on a map.

This definition is intrinsically linked to the social narrative of open spaces and gardens, commons and property, the dwellings/housing types and the space around them, backyards, their role in biodiversity (as an environmental outcome), inclusion and exclusion as drivers of the whole community.

3

There is a note within the Guidelines that distinguishes between POS and publicly accessible privately-owned open communal space that may reduce the requirement for new lots deliver a full 10% POS, in particular where strata and community title schemes deliver communal open space, where communal open space is demonstrated by way of an approved plan to be designed and function like POS and where there is unrestricted public access via an easement.

7. LITERATURE REVIEW

This study considers what could innovation in design and function of open space could look like within our communities To do this requires an initial investigation of historic models such as

• enclosed reserves (Roosevelt, 1925),

• creation of new social narratives around POS and gardens (Flusty and Hayden 1996), (Ruble, 2016), (Green, 2011),

• a more collective European walk-up apartment model with communal space at the ground plane, rather than the English terrace model driven by Locke’s view of commons, fences, and property ownership (Harding, 2019),

• definitions of the function of different spaces around dwellings/housing types (Farrelly, 2023),

• current trends to improve biodiversity and wildlife corridors (Vega et al 2022), (Pascual et al, 2023), and

• Studies of inclusion vs exclusion and homogeneity of the user (Hester, 1984) as a social driver in open space success factors/determinants

Academics Hayden, Freestone, and Nichols have focused on the yard, enclosed shared spaces and suburban centres via a chronological re-telling of the creation of shared spaces – their origins and their innovation - from English Park Villas (1830s), Industrial Parks and Communitarian Settlements (1840s), Picturesque Enclaves (1860s), Allotment Gardens and Internal Reserves (1900-1950) and associated connections to the plans of the Garden City Movement throughout the post war migration in Australia, US, Middle East and Europe.

There is little evidence in this narrative around those who gathered in clusters around these private spaces, and the learnings that could be applied by consideration of this dimension.

7.1 Cultural

The debate around open space and innovation is not new, from the moment colonial sub-divisions emerged, advocates for open space promoted a cleaner, sanitised expression of positive values in developing cities around the world –“the basis ideal of a future world” (Burley-Griffin, 1912). While the antagonists drew lines in the space against this proposition, noting “quadrangles of useless bits of land thrown together to produce a haphazard outcome (Oxbridge 1909), “a cemetery for the corpse of the house cat” (Taylor 1918), “a trash heap”, “weed patches”, “places of poor surveillance”, “a distinct lack of privacy”, “places for social impropriety” or a “ green desert” (Freestone, 1989).

There are consistent clusters in our history where population growth demands more housing, technology drives us away from nature, or communities migrate to seek a better life for themselves, and we find ourselves at this crossroad seeking innovation in our urban spaces. The cyclical timelines, evidenced by the literature cited, certainly point to industrialisation, war, hardship, or mass migration driving whole communities to build their homes like gypsy caravans around their protected collective reserve, perhaps seeking a common gathering space for warmth, food preparation, ceremony and symbolically to protect themselves from those who posed a threat.

One could conjecture that the failure of the “internal reserve” that saw the Radburn Plans in Australia’s social housing turn into backyard “badlands” was more the result of changing social values of the late 1980s that saw women return to work in their droves, an unprecedent individualism and materialism grow that drove the fences up and left the suburban greens and playgrounds quiet.

4

Freestone and Nichols (2004, 2001, 1989) consider “the rise and fall of the internal reserve” – as an innovation as curious and sporadic, and pockets of history left over. They consider the case studies and the influential town planners designing them (such as Walter & Marian Burley Griffin, Saxil Tuxen, Charles Reade, William Bold, Klem & Hope, Robinson & Copley) as aspirational anomalies.

Language around open space as a retreat/respite, a place that marks a community, provides for status, and increases economic return for an area are consistent and recurring themes by sociologists, rather than urban or landscape architects. This work continues to highlight the attitudinal and symbolic attachment to these spaces over simply their form.

Community gardening is cited as repeatedly contributing to solving urban problems of the past. The literature over the last five years points to a reinvigoration of community gardening to sure up food supply and build community cohesion. Evident in the work of northern European academics from Vienna (Mayrhofer 2021) through to Bruxelles (Bruer, 2018, Milani 2021) which highlight this shift is both cultural and contextual.

Hester (1984, 36) puts forward the concept of “symbiotic ownership” as attributable to the success of a shared space. He also notes territory and dominance, cooperation vs competition, privacy, interactions variance, class and lifecycle stage and comfort as driving social factors of success in neighbourhood space. This is explored by Castells (1985), Zukin et al (2016) and quoted in Martire et al (2023) in terms of those who define themselves by age, similar ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, or family structure, mobilising to acquire “collective resources” and “communal territories” to find refuge, and these spaces get refined accordingly.

This theoretical concept of “symbiotic ownership” could be applied to the “internal private reserves”, and culturally specific spaces such as:

• the “kibbutz” created by the Zonist settlements in Palestine (Zaidman and Kark 2015, Katz 1994),

• the private backyards sought by the European Migrants Post WWI in Australian suburbs such as Menora, Coolbinia, Ivanhoe, and Darebin,

• the government-built communities for returning soldiers in Colonial Ridge Gardens, SA, and other sites around the globe,

• the “emerging successful businessmen” moving to rural size dwellings to cement their newfound wealth across communal lots in Sydney’s Killara subdivision, Darceyville, or Melbourne’s Blackburn,

• the South Sea Islanders behind the common food gardens in Camberwell Sydney,

• the social reformists driving communal living in harmony with nature - such as the Griffins in Castlecrag, New York’s Sunnyside Gardens, to

• the 1970s neighbours “taking down the fences” to create shared BBQ areas and pottery sheds.

For Müller (2012), the most important ingredient for a successful community space is not about the predefinition and restricted rules, but about the openness and even an atmosphere of untidiness, which gives space to cooperation and desires to create innovative ideas. However, the “untidiness” and lack of “symbiotic ownership” have seen many of these have fallen into disrepair, become known as “backlands,” where the fences have come up to block out this once heralded version of utopia However, as Müller (2012) points out the most important ingredient for a successful community space is not about the predefinition, exclusion, and restricted rules, but about the openness and even an atmosphere of untidiness, which gives space to cooperation and desires to create innovative ideas”. These are again ideas based in social theory and cultural context.

7.2 Social

The idea to “sit out of doors in neighbourly intercourse,” or “share a garden,” relies on a similar grouping of likeminded cohort, and to a degree an absence of difference or diversity (Calderia and Sorkin, 1994). Sorkin expands briefly on this idea as he notes that “cities without segregation, have only existed in the dreams of some utopian thinkers – throughout history, segregation both social and spatial – has been an important mark of existing cities.” He notes the multi-ethnic vibrant communal spaces as the antithesis or medicinal antidote to impersonal and increasing technological impacts.

5

Other social scientists have long considered the civic links between innovation in the built environment, behaviours over urban space and communal life, (Zhu Fu 2016 and Dickinson et al 2003) socio-cultural exchange (Federici 2012), subordination of women, people of colour, lower class people and nature in social patriarchal structures, outsiders, and partners in delivery of space, and the link between these users and the environment (Milani 2021).

Dolores Hayden explores in her work “Power of Place” neglected histories of the “The Other” – women, the elderly, workers, and ethnic minorities” – where shared internal reserves and common squares have provided places of gathering, safety, and an outlet for these groups – not advanced by the “developers suburban model” of enclosed yards. (Lategan and Cilliers 2014, Milani 2021)

There is a burst of current academic literature and studies as to POS post covid, where the cultural, social, and economic resources in POS provide important health and welfare benefits when located close to a dwelling. Hsu et al (2022), Meyrick and Newman (2023), Bhaskaran and Nilon (2022), Eriksson (2022), Bhaskaran and Nilon (2022) and Eriksson (2022) all point again the antidote to isolation in our homes was the use of nearby open space

7.3 Economic

Drayton (2000) poses the question why if it makes such sense to improve property values, develop aesthetically pleasing hidden, or secret, pockets of open space, why whole cities have not turned their attention to turning a patchwork of urban back yards into neighbourly communal parks?

Whether it be for “bourgeois aspirations” or “humanist socialism” fenceless gardens are a metaphorical and practical means of connecting individual economic respectability of the citizen to the well-being of the overall community.

London’s prized communal gated gardens and New York city’s walled shared block gardens, once a drawcard for musicians, artists, and hippies, are now coveted residential lots with minimal occupancy turnover, excluding all others bar privileged residents, with sky rocketing housing prices (Rowlinson, L, 2021), (Drayton, 2021). They provide an interesting economic lens to consider attraction and renewal (or some would say “gentrification,” rather than cost)

6

8. METHODOLOGY

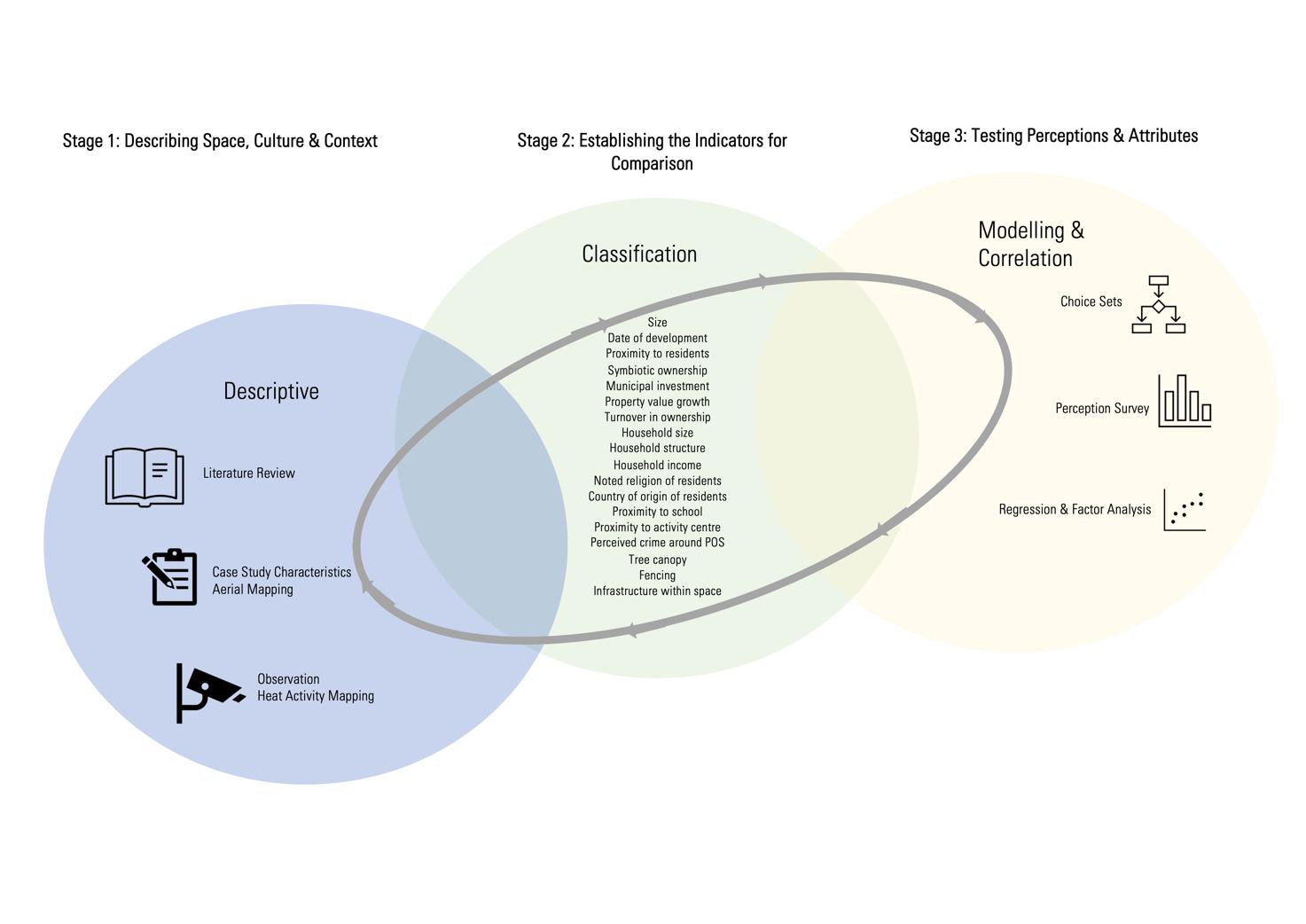

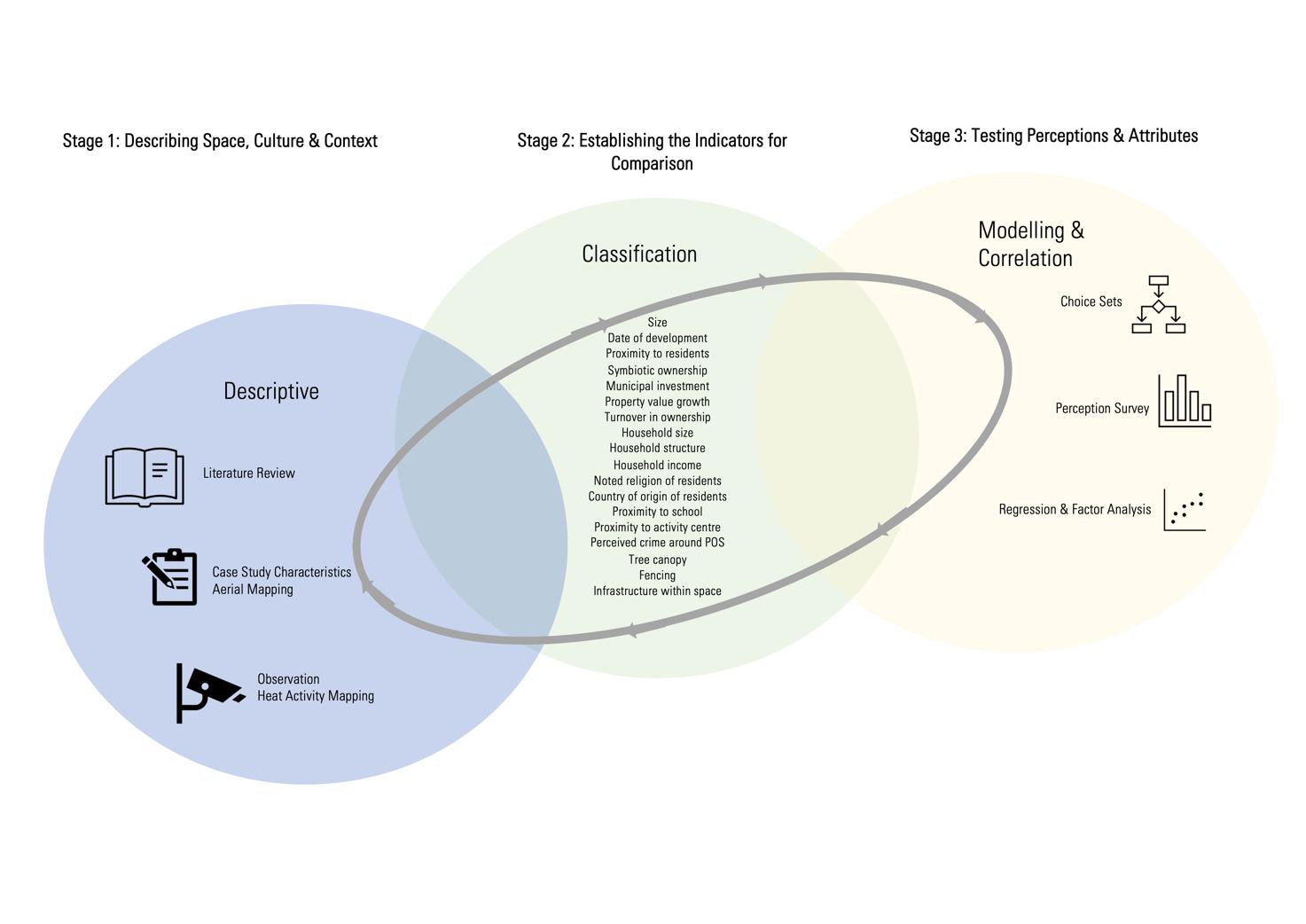

Figure 1: Proposed Methodology

This innovation in open space study is a cross sectional study that is designed in three stages. The first descriptive stage intends to further investigate the historic models and design theory associated with 25 documented “innovative” open spaces, particularly those that demonstrate this innovation in line with the cultural, social, and economic factors identified in the literature review The second classification stage establishes the indicators for deductive comparison across the 25 case study spaces using existing datasets and mapping, and the third stage overlays perceptions and attitudes across these indicators to reflect the drivers of innovation in terms of perceived preference (choice sets), an attitudinal scale of desirability, and identify the variables with the greatest level of predictability of innovation/desirability The quantitative analysis will also consider the identified groups of common factors that can influence future design criteria.

Stage 1: Space, Culture & Context

1.1 Desktop Review – Case Studies

A desktop review of the 25 identified Australian and International case studies (detailed in Section 9 Table 1-3 on Page 10) will be conducted to document and describe the characteristics, trends, and design intent categories of each case study (primarily through aerial mapping and local history texts) to establish the theoretical framework Where possible, original development masterplans will be assessed to consider intent and execution of the space over time. This assessment will be qualitative in nature to describe, compare and understand the historic, cultural, and spatial context of each identified case study. The proposed case studies were selected based on criteria noted in the initial literature review to ensure they are representative of historical timelines, design models proposing a difference from the norm and cultural specifics.

7

1.2 Observation – Spatial Activity Heat Mapping

Heat maps will be generated to visually represent activity within each of the 25 open spaces across three set times (7am, noon and 6pm) on two weekdays and a weekend day. These will be created using local Telcos mobile phone to plot access, location, dwell time, trip distance to map spatially (e.g., using Telstra Spatial Insights within Australia) across a polygon zone that measures movement as people and objects traverse through that zone. This will identify areas of use, desire lines and indicative attachment to the open space. Further investigation will be required in the international context to test availability of this primary data source, and alternative primary observation techniques utilised to spatially map frequency of use, and activity if required.

Stage 2: Establishing The Indicators for Comparison

A list of defining and tangible socio-demographic, cultural and economic indicators for comparison will be identified using a publicly available dataset via desktop research. These metrics will be assessed and compared in tabular form across all 25 case studies to investigate patterns, and plot similarities/difference across a potential matrix of success determined initially by use and activity, and later by the attitudinal survey in stage three

A proposed table of indicators and measurement indices are detailed in Section 10 Table 4 on Page 12.

Stage 3: Testing Perceptions & Attributes

Once the spatial movement and use maps, and the comparative indicator tables are complete, an attitudinal perception survey will be conducted with residents and users of the open space identified in the case studies.

3.1 Sample

A target sample of 1,250 residents, or park users, will be sought (representing 50 residents or park users at each identified case study). This will provide a robust sample, with a likely margin of error of around 10% at the 85% confidence interval, assuming the total number residents within a block radius of the identified park is no more than 1,000 people) and provide the opportunity for comparison across socio-demographic and economic characteristics.

3.2 Recruitment

Survey participants will be recruited initially using an appealing and branded direct mail postcard sent to each residential address in the neighbourhood surrounding the open space, inviting participation in a self-completion online survey identified via a weblink or QR code. In addition, poster flyers will be placed in each open space advertising the project and inviting participation. An incentive of a local plant tuber will be provided for all completed surveys.

3.3 Instrument

The survey instrument will be divided into 5 parts, as detailed below:

• use (I.e how often on a scale of never, a few times a year, at least once a month, at least once a week, almost daily or daily) and behaviour questions around use of existing open space,

• preferences using initially a choice set using images of different open space innovations (i.e., enclosed vs open, hard infrastructure vs natural landscaping, a range of comparable sizes and visually different cohorts of users – with respondents being asked which image they most preferred/least preferred and why?)

8

• desirability using a Likert 5-point rating scale across desired attributes within the open space (i.e., meet people, experience nature, grow food, feel safe, socialise with my neighbours, occupy my children, play sport, exercise, walk the dog, chat to friends, craft or construction, BBQ, rest)

• An overall rating scores on perceived innovation of the open space and desirability of the open space.

• The survey instrument will also include socio - demographic and economic profile characteristics data, perceived cohesion, and perceived positive or negative relationships with neighbours

3.4 Analysis

All data will be verified, and any missing data excluded from the analysis. The analysis will be built initially in excel with regression, factor analysis and any further correlation work conducted using SPSS or Power BI to tabulate and graph results. Multiple regression will be used to predict the dependent variable by the independent variables, and further factor analysis will be used to identify grouping of variables by their underlying dimensions and relationship to innovation and desirability of open space. Any open-ended questions, or qualitative data will be coded and grouped by theme, then illustrated quantitatively.

Stage 4: Reporting

The findings of all stages of the research methodology will be graphically and spatially summarised with comment in a final report. This report will be provided to the WA Planning Commission to assist in the development of future public open space policy, local LGA guidelines and governance decisions relating to shared and communal open space.

9. CONCLUSION

“For almost 200 years, … all classes have idealized life in single-family houses with generous yards, while deploring the sprawling metropolitan regions that result from unregulated residential and commercial growth.” (Hayden 2003) Today, there is an evidenced drive towards collectivism, urban gardens, biodiversity corridors and post covid connection to green space, yet we still guard our fences. Perhaps there has been no better time to see innovation in policy that sees the fences come down to create common public open space that is shared, used and relevant for our human and non-human communities into the future?

9

A PPENDIX 1: C ASE S TUDY T ABLES

T able 1: Examples of Enclosed Reserves

NameofReserve Date Description

DarceyGardensSydneyNSW 1918 This affordable state govt housing model has a clause to keep gardens in good order, with garden competitions, a school of arts and community hall.

Castlecrag– SydneyNSW 1921 Griffins greater Sydney development association – establishing sense of community and focusing on its own needs, includes a natural amphitheatre, arts, protection of nature environment and landscape character, a “neighbourhood circle” where residents helped each other build their homes. Covenants placed on the land to protect native trees, prevent buildings that would be out of place or impeded views or were too dominant, levy to maintain reserves, tree planting and other activities to protect common spaces. Living rooms designed to face view of park on the inner side of the allotment.

SunnysideGardens,NewYork 1924

Designed based on philanthropic idealists and urban critics, a. community of affordable homes for working people, co-op and rental apartment buildings around common gardens and parks.

ColonialGardenLightAdelaideSA 1924 This soldier settlement was based on Hamstead heath model and presented at 2nd Town Planning Conference and Exhibition held in Brisbane in 1918. It includes rear lot gardens and minor internal reserves – intended originally for WWI injured soldiers, sailors, and war windows

Ticket of Leave Park - Killara, SydneyNSW 1927 28 residents abut this central wooded densely green enclosed reserve, access via a small walking lane between two homes.

Hartlands Internal Reserve –IvanhoeVictoria 1930 A triangular reserve behind the houses as part of a geometrically patterned 313 -hectare subdivision by Saxil Tuxen. 12 houses abutting the park proper have access to it via back gates, while another four properties have access via the “neck”. Children’s play area, fire pit and residents maintain the space.

WarralongCresCoolbiniaPerth 1930 –1950 A shared common reserve designed as part of the original plan based on the Garden City Movement by Robinson & Copley. 28 residents abut the reserve with each resident having a small private yard that opens out to the common private reserve that can be accessed via a small path from the street. Residents use the space for afternoon drinks and activity.

Gan,MierPark,TelAviv,Israel 1940

Named after first Mayor Meir Dizengoff, fenced public park with promenades, fishponds, outdoor gym, playground basketball court, feature trees and green canopy Amster Yard, Turtle Gardens, New York 1946 Turtle bay gardens, NY City-Italianate Garden with a central fountain, cool shade, and a tree between Forty-eighth and Forty ninth Streets and Second and Third Avenues. It was the creation of a Mrs. Walton Martin, who bought the surrounding twenty houses in 1919 and 1920. She altered each one so that all the living rooms faced the garden, removed fences that separated back yards to create a plan based on group housing she had seen in Italy and France. The original covenant stipulates that no fences be built in the rear, no laundry lines or garbage cans be visible, and no building be used as a boarding-house. There are small private greens that residents can plant as they choose, however they visually merge with the common green.

10

Table 2: Examples of Radburn Plan Reserves

NameofReserve Date

Arkwright Meadows Community Garden - The Meadows Nottingham,UK

1963

Crestwood Reserve BushlandThornlie – CreswoodEstate –1970

DesUglePark - 1960

Landscape Drive Playground

Description

A historic social housing Radburn project designed to clear out a slum in the 1960s, New Meadows underwent a redevelopment in early 2000, which saw local Meadows residents coming together to transform part of a disused, unloved, rubbish-strewn playing field into a green space for the local people to use, includes a safe space for family events, place of learning and opportunity to buy freshly grown fruit and vegetables.

A benchmark Radburn planned development targeting families and independent homeowners is still as the masterplan intended with limited back fences and a large, shared reserve for its 295 residents.

Withers Housing Estate, in South Bunbury – a state housing commission Radburn masterplan that is being revitalised due to social and cultural issues within the community.

Doncaster Victoria - Milgate ReserveEstateVictoria –1975 owned by the residents through a homeowner’s association. Developed by Jim Hedstrom (designed by Peter Mulcahy) first homeowners association in Victoria pay an annual fee towards maintenance of public open space and community facilities. No fences. 1975 – roadways named after the artists of the Heidelberg Arts School.

VineyStNorthStMary’sSydney - 1942 Radburn model was used for a housing estate for workers at the Commonwealth Munitions works in St. Marys, Sydney, from 1942, the architect being Walter Bunning [8

Hail Pond Community ParkWestmountSubdivisioninHalifax Early 1950s Hail Pond Community Park sits in a Radburn neighbourhood on the site of the original Halifax Municipal airport. In Westmount in Halifax Radburn designs are desirable middle to upper-middle income neighbourhoods to reside in.

VarsityRavinePark - VarsityVillage –Calgary,Alberta the late 1960s Clarence Stein and Henry Right incorporated Radburn design principles into the developers of Varsity Village in the late 1960s.

Table 3: Examples of Traditional POS, Liveable Neighbourhoods and Community Gardens

NameofReserve Date Description

Alexandria Park – Alexandria SydneyNSW 1882 A central urban park with a white picket fence, surrounding residents overlooking the park, features a children’s playground, allocated dog space, exercise pitches, facilities, and paths. Abuts a community school and light retail activity.

MullerPark – SubiacoWA 1906 An unfenced 4-hectare park between two schools and major roads with walking paths and a central children’s playground. Limited residential allotment adjacent to park and once part of a larger sporting precinct.

CeruleanPark– SeasideFlorida,US 1981 A highly decorative garden-esque style park, complete with butterfly park, in the acclaimed new urbanist master planned development WaterColor near Seaside Florida, designed by Andrés Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk.

the Kauwberg – Uccle Bruxelles, Belgium 1980 A semi-natural site, set aside for walking and encountering nature, managed by Environment Bruxelles. It does not have any special facilities but hosts a community urban garden, since the site was returned to the public in 1980s. Formerly, it was an entirely wooded area which partly fell under the national forest of Soignes and partly belonged to private owners such as the Terarken hospice, the lordship of Carloo and the Forest abbey.

Willow Pond Park – Harbour Town Memphis,US 1991

LeatherbackPark - AlkimosWA 2008

Perth Urban Orchard and Wetland, PerthWA 2010

This sculptured feature park abuts 12 residents in this new urbanist development set on a peninsula setting, with large residential condos.

A 2- hectare destination park set in the new urbanist coastal development in the northern suburbs of Perth, bound by roads, a primary school and fitness park.

Established by City Farm volunteers over a concrete roof of a public car park in the centre of the city. The volunteers grow food, share the harvest, interact with the public, and run educational tours through the space. They also care for the Urban Wetlands, a thriving fresh-water ecosystem, home to frogs, fish, waterbirds, and thousands of insects.

Meadow Brook Park, Prairie Village,KansasUS 2021 An old golf course in the middle of a Jefferson Grid has been converted into a 50 plus hectare landscape urbanism driven site around a central public space. More than 700 living spaces surround the public space with each grouping about four blocks in size.

BobGordonPlaySpace - BullCreek, WA upgrade 2023

$4million upgrade, intergeneration space, informal recreation, fencing to separate activities. Winner AILA 2023 Award.

11

A PPENDIX 2: C OMPARATIVE I NDICATORS

Table 4: Indicators & Measurement Criteria

INDICATOR

Intergeneration attitudes/history

Proximity

Symbiotic ownership

Municipal Investment

Residents Investment

Property value growth around the POS

Turnover of properties in ownership

Household size

Household income

Noted religion

Country of origin

date of construction

size/area m2 of the space and distance from house

% shared/private

$ spent on maintenance per annum

Levies or fees paid per annum

% growth in property value in 2 or more decades

% turnover across 2 or more decades

LGA/History/Library

Aerial Maps

LGA (Local Government Area)

LGA (Local Government Area)

Residents Association

Core Logic/REIWA

Core Logic/REIWA

Demographic similarity/difference surrounding POS

average household size

mean household income)

% noted religion compared to state average

% noted country of origin compared to state average

Age of residents mean

Family structure

Perceived use and time of day

% school age children

% over 55

% married

mobile phone activity data – low, medium, high

Proximity to school/activity centre distance

Perceived crime around POS

Tree canopy

Municipal investment

#break and enters

% coverage across POS

$ spent in maintenance per year

Fencing Fully enclosed/Part enclosed/Not Enclosed

Infrastructure presence of shed/BBQ/garden/seating/food/pottery shed/play-equipment)

ABS Census 2021 Data at Mesh Block/ Statistical Area 1 level surrounding and including identified space

ABS Census 2021 Data at Mesh Block/ Statistical Area 1 level surrounding and including identified space

ABS Census 2021 Data at Mesh Block/ Statistical Area 1 level surrounding and including identified space

ABS Census 2021 Data at Mesh Block/ Statistical Area 1 level surrounding and including identified space

ABS Census 2021 Data at Mesh Block/ Statistical Area 1 level surrounding and including identified space

ABS Census 2021 Data at Mesh Block/ Statistical Area 1 level surrounding and including identified space

Telstra Spatial Insights/Google Spatial Usage Data

Aerial Mapping

#break and enters

% coverage across POS

$ spent in maintenance per year

Aerial photographs, or direct observation

Aerial photographs, or direct observation

12

SOURCE

MEASURE DATA

10. REFERENCES

Bolleter, Julian. 2020. “Green Dream: Examining the Barriers to an Innovative Stormwater and Public Open Space Structure Plan on Perth’s Suburban Fringe.” Australian Planner 56 (1): 22–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/07293682.2020.1739090

Brennan, Bede. 2023. “An Adaptive Attitude: The Roundtable.” Landscape Australia. June 20, 2023. https://landscapeaustralia.com/articles/an-adaptive-attitude-the-roundtable/

Bruer, Eva. 2018. “The Commons in Brussels: Urban Gardening as a Way to Catalyze Active Citizenship and Environmental Stewardship.” Thesis For: Master of Political Science, Vrije University Brussels, December. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.21188.27520

Buchanan, Barbara Louise. 2009. “Modernism Meets the Australian Bush: Harry Howard and the ‘Sydney Bush School’ of Landscape Architecture.” UNSWorks. 2009. https://unsworks.unsw.edu.au/entities/publication/7dabe2af-195c-4ac3-91db-ef8d00021592

Caldeira, Teresa, and Sorkin, Michael. 1994. “Variations on a Theme Park: The New American City and the End of Public Space.” Journal of Architectural Education (1984-) 48 (1): 65. https://doi.org/10.2307/1425310

Deming M and Swaffield, S. 2013. Landscape Architecture Research: Inquiry, Strategy, Design. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley.

Drayton, W. 2000. “Secret Gardens.” The Atlantic Monthly 285 (June): 108–11. https://www.proquest.com/magazines/secret-gardens/docview/223099346/se-2

Eizenberg, Efrat. 2011. “Actually Existing Commons: Three Moments of Space of Community Gardens in New York City.” Antipode 44 (3): 764–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2011.00892.x

Farrelly, Elizabeth. 2023. “Boulevard of Open Dreams.” The Saturday Paper. September 9, 2023. https://www.thesaturdaypaper.com.au/life/cities/2023/09/09/boulevard-open-dreams

Flusty, Steven E., and Dolores Hayden. 1996. “Review of the Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History.” Urban Studies 33 (7): 1221–23. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43083341

Foucault, Michel. 1986. “Of Other Spaces.” Diacritics 16 (1): 22–27.

Freestone, Robert. 1989. Model Communities. Thomas Nelson Australia.

Freestone, Robert, and David Nicholls. 2001. “A ‘Particularly Happy’ Arrangement? Idealism, Pragmatism, and the Enclosed Open Spaces of Perth Garden Suburbs.” Liminia 7 (2001): 65–78. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.305351465415699

Freestone, Robert, and David Nichols. 2004. “Realising New Leisure Opportunities for Old Urban Parks: The Internal Reserve in Australia.” Landscape and Urban Planning 68 (1): 109–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2003.07.001

Green, Jared. 2011. “Interview with Martha Schwartz, FASLA |.” ASLA www.asla.org. 2011. https://www.asla.org/ContentDetail.aspx?id=33801

13

Harding, Eloise. 2019. “Spoilage and Squatting: A Lockean Argument.” Res Publica 26 (November): 299–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11158-019-09445-0

Hayden, Dolores. 2003. Building Suburbia: Green Fields and Urban Growth, 1820-2000. New York: Pantheon Books.

Hester, Randolph T. 1984. Planning Neighborhood Space with People. Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Jacobs, Jane. 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House.

Katz, Yossi. 1994. “The Extension of Ebenezer Howard’s Ideas on Urbanization Outside the British Isles: The Example of Palestine.” Geo Journal 34 (4): 467–73. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41146338.

Lefebvre, Henri. (1974) 1991. The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell.

LOPEZ-PINEIRO, Sergio. 2020. “The Limit toward Emptiness: Urban Voids as Public Space.” Landscape Architecture Frontiers 8 (5): 120. https://doi.org/10.15302/j-laf-1-030020

Lucarelli, Fosco. 2012. “Strategy of the Void: Building the Model of OMA’s Très Grande… – SOCKS.” SocksStudio.com. May 20, 2012. https://socks-studio.com/2012/05/20/strategy-of-the-void-building-the-modelof-omas-tres-grande-bibliotheque/

MacLaran, Andrew. 2014. Making Space. Routledge.

Martire, Agustina, Birgit Hausleitner, and Jane Clossick. 2023. Everyday Streets. UCL Press.

Milani, Bruna. 2021. “Commoning in Urban Gardens in Brussels, an Ecofeminist Approach to the Urban Commons.” Thesis, Universite Libre De Bruxelles https://urbanstudies.brussels/sites/default/files/202109/2021_Farine%20Milani.pdf

Mubi Brighenti, Andrea. 2016. Urban Interstices: The Aesthetics and the Politics of the In-Between Routledge. n.d. 1937. “Spacious Reserves Kur-Ing-Gai Cost 600 Pounds.” Daily Telegraph, June 30, 1937. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/247141395?searchTerm=1927%20killara%20reserve%20for%20p ublic%20recreation

Pascual, Unai, Patricia Balvanera, Christopher B. Anderson, Rebecca Chaplin-Kramer, Michael Christie, David González-Jiménez, et al. 2023. “Diverse Values of Nature for Sustainability.” Nature 620 (2023): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06406-9

Poulsen, Lone. 2010. “Towards Creating Inclusive Cities: Experiences and Challenges in Contemporary African Cities.” Urban Forum 21 (1): 21–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-010-9077-6

Property Council of Australia, Western Australia Chapter. 2023. “Response to Draft Operational Policy 2.3 - Public Open Space.”

Ruble, Blair. 2016. “Small Is Beautiful: A Washington Tale of Little Red Rockers and Ducks” Wilson Center August 11, 2016. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/small-beautiful-washington-tale-little-redrockers-and-ducks

14

Şimşek, Onur. 2019. “Emptiness and Nothingness in OMA`s Libraries.” MEGARON / Yıldız Technical University, Faculty of Architecture E-Journal https://doi.org/10.14744/megaron.2019.57873

Sundevall, Elin P., and Märit Jansson. 2020. “Inclusive Parks across Ages: Multifunction and Urban Open Space Management for Children, Adolescents, and the Elderly.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (24): 9357. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249357

Twiss, Joan, Joy Dickinson, Shirley Duma, Tanya Kleinman, Heather Paulsen, and Liz Rilveria. 2003. “Community Gardens: Lessons Learned from California Healthy Cities and Communities.” American Journal of Public Health 93 (9): 1435–38. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.93.9.1435

Vandeburie, J. 2004. “MacLaran A. (Éd.) Making Space, Property Development and Urban Planning.” Belgeo 4 (4): 497–508. https://doi.org/10.4000/belgeo.13464

Vega, Kevin, Anouk-Lisa Taucher, Christoph Kueffer, and Johan Six. 2022. “Punching above Their Weight, the Role of Small Green Spaces for Biodiversity in Cities.” Integrating Biodiversity in Urban Planning and Design Processes, 7th International Conference, URBIO 28-30 November 2022. https://doi.org/10.57699/hd4s-e705

Vidler, Anthony. 2011. “Another Brick in the Wall.” New Brutalism, 136 (Spring 2011): 105–132. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23014873

Watson, Emily. 2023. “Six Friends Pooled Their Money for the Home of Their Dreams. It Almost Wasn’t Enough.” ABC News, August 23, 2023. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-08-24/nz-opens-density-limits-friendsdeveloping-new-housing/102714716

Weller, Richard. 2008. “Landscape (Sub)Urbanism in Theory and Practice.” Landscape Journal 27 (2): 247–67. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43332451

Western Australian Planning Commission (WAPC). 2023. “Operational Policy 2.3, Draft Planning for Public Open Space.” WA Government Publications. Perth, Western Australia: WA Government. https://www.wa.gov.au/government/publications/draft-operational-policy-23-planning-public-openspace

Whyte, William Hollingsworth. 1980. The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. New York: Project for Public Spaces.

Wolch, Jennifer R., Jason Byrne, and Joshua P. Newell. 2014. “Urban Green Space, Public Health, and Environmental Justice: The Challenge of Making Cities ‘Just Green Enough.’” Landscape and Urban Planning 125 (May): 234–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.01.017

Xiao, Yang, Zhigang Li, and Chris Webster. 2016. “Estimating the Mediating Effect of Privately Supplied Green Space on the Relationship between Urban Public Green Space and Property Value: Evidence from Shanghai, China.” Land Use Policy 54 (July): 439–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.03.001

Zaidman, Miki, and Ruth Kark. 2015. “Garden Cities in the Jewish Yishuv of Palestine: Zionist Ideology and Practice 1905–1945.” Planning Perspectives 31 (1): 55–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2015.1039051

Zhu, Yushu, and Qiang Fu. 2016. “Deciphering the Civic Virtue of Communal Space.” Environment and Behaviour 49 (2): 161–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916515627308

15

11. CASE STUDY REFERENCES

Alzona, Len, et al. Alexandria: Liveability, Community, and Change Research Conducted as Part of the UNSW Master of Urban Policy and Strategy. 2015.

Campbell, Shaun. “Doncaster Templestowe Historical Society: Milgate Park Estate.” Doncaster Templestowe Historical Society, Manningham Leader, Herald Sun, 2013, dt-hs.blogspot.com/2023/07/milgate-parkestate.html. Accessed 22 Oct. 2023.

Chen, Ivanne. “The New Urbanism: Successes and Failures.” The New Urbanism, 8 Mar. 2022, urbandesignlab.in/the-new-urbanism-successes-and-failures/.

City of Bunbury. “Withers Renewal Program.” City of Bunbury, May 2023, www.bunbury.wa.gov.au/projects/withers-renewal-program.

De Poloni, Gina. “How a Neighbourhood with Back-To-Front Houses Became a World-Class Suburban Utopia.” ABC News, 22 Feb. 2020, www.abc.net.au/news/2020-02-23/crestwood-estate-50-years-as-perfectradburn-neighbourhood/11981830

Environment, Buxelles. “Le Kauwberg.” Brussels Gardens, 2023, gardens. brussels/fr/espaces-verts/le kauwberg Accessed 31 Oct. 2023

Heritage Council WA. “Places of Significance Database - Withers Homeswest South Bunbury Housing Estate.” Inherit.stateheritage.wa.gov.au, 1996, inherit.stateheritage.wa.gov.au/Public/Inventory/PrintSingleRecord/c9ff44ef-41be-4c1c-91cdc2f84787f221. Accessed 22 Oct. 2023.

Jackson-Stepowski, Susan. 2002. “Dacey Garden Suburb a Report for Daceyville Heritage Conservation Area within Its Historical Context” Prepared for Botany City Council http://www.daceyville.com/heritage_documents/DACEY%20GARDEN%20SUBURB.pdf

Johansson, Dianne. “People of Bunbury: Des Ugle Remembered.” Bunbury Mail, 27 Oct. 2015, www.bunburymail.com.au/story/3451869/people-of-bunbury-des-ugle-remembered/. Accessed 22 Oct. 2023.

Leslie, Esther. 1988. The Suburb of Castlecrag. The Bicentennial Community Committee

Missell, Jody. 2020. Introduction to Coolbinia Interview by Trent Fleskens. The Perth Property Show https://perthpropertyshow.com.au/069-intro-to-owner-occupier-building-coolbellup-suburb-spotlight/

n.d. “Varsity Community Information - Calgary.” RentFaster.ca, 2003, www.rentfaster.ca/ab/calgary/community/varsity/?desktop=1. Accessed 22 Oct. 2023.

Perth City Farm. “Urban Orchard and Wetlands - Perth City Farm.” Urban Orchard and Wetlands, 14 Apr. 2021, perthcityfarm.org.au/urban orchard/. Accessed 30 Oct. 2023.

Rachel. “Arkwright Meadows Community Gardens in the Heart of the Meadows.” Arkwright Meadows Community Gardens, 2023, www.amcgardens.co.uk/. Accessed 30 Oct. 2023.

Roosevelt, Eleanor. 1925. “The Vanishing Vine & Fig Tree - on Sunnyside Gardens.” The Womens Viewpoint, October 1925. October 1925 (via Sunnyside Gardens Digital Archive). https://drive.google.com/file/d/1PDq13U7sAMhhPXcpQpO0NWhseTl6NV96/view

Saraniero, Nicole. “Amster Yard in Turtle Bay, One of NYC’s Most Beautiful Hidden Courtyards.” Untapped New York, 29 Mar. 2018, untappedcities.com/2018/03/29/amster-yard-in-turtle-bay-one-of-nycs-mostbeautiful-hidden-courtyards/. Accessed 30 Oct. 2023.

Steuteville, Robert. “A Practical “Landscape Urbanism” in a Postwar Suburb.” CNU, 20 July 2021, www.cnu.org/publicsquare/2021/07/20/practical-%E2%80%98landscape-urbanism%E2%80%99-postwarsuburb. Accessed 31 Oct. 2023.

16

Yarrow, Stephen. “Lost Sydney: St Marys’ Munitions Factory.” Www.visitsydneyaustralia.com.au, Pocket OZ Guide to Sydney, 2023, www.visitsydneyaustralia.com.au/lost-stmarys-munitions.html. Accessed 22 Oct. 2023.

17