Tau Emerald & Chamelaucium spp. Wax Flower Student’s Own Watercolour, Ink and Graphite Illustration 1 LACH 5424 STUDIO - FOLIO QUINLAN_19008890

The rivers, waters and undulating dune systems of the Swan Coastal Plan havestrong and ancient story line connections to the Traditional Owners and the Noongar people.

In particular they tell the story of creation (THE WAUGUL – the ancient serpent and creator of our waterways).

According to Noongar culture - The Waugul is present wherever living water is found. Rivers, creeks and wetlands are, ‘spiritual repositories places that draw on the fundamental philosophy of Noongar spiritual believes as places of spirit, birth and spirit rest.

Like the Water Cycle the fundamentals of Noongar belief system is that all living creatures, are a part of the wider spiritual universe and cyclical system. Wetlands and damplands are a crucial part of this cycle, both as breeding grounds for numerous living creatures, repositories of spiritual essence realised generationally by individuals and sources of food, water and protection.

(Source: South West Land & Sea Corporation)

A key indicator of a healthy waterway and cycle is the dragonfly

Elder Barry McGuire stated at the Opening of Under One Sun that dragonflies are a sign that the rain has stopped for the season as they exit the water and start flying about. Symbols of change, transition and transformation.

While Elder Neville Collard says in his Dragon Fly Story - The Karlitch – dragonfly – is a beautiful little animal that flies around the water holes. It provides food for birds and animals – maybe possums/mice if they get their teeth on them, They fly so very fast, They are also known as mosquito hawks, devils darning needles and snake doctors.

“Karl” is the fire – got big bright red eyes – “fire in their eyes” is what Karlitch means, when you show spotlight on them at night their eyes glow red and you can see them around.

When they mate the female lays the eggs directly onto the water –eggs (nooroks) drift the edges. May take several months to hatch.. young dragon flies leave the water till they become sexually mature which results in dispersal when they are ready to mate.

Dragonflies people say are one of the most successful creatures on earth – fossils found from dragon flies that lived over 30 million years ago.

Stories of our people using dragon flies in art, painting extravagant and beautiful creatures,

At most water holes, most parks, you can sit in shade and you’ll see them. Take a close look at eyes and I believe you’ll see the red or fire in his eyes

(Source: Whadjuk Trails).

I acknowledge the Whadjuk and Beelier people of the Noongar nation as the Traditional Owners of this place and pay my respects to the elders past and present who have cared for this country and its people, and upon which we have the opportunity to learn and study.

OF COUNTRY Stories, Science and

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Connections

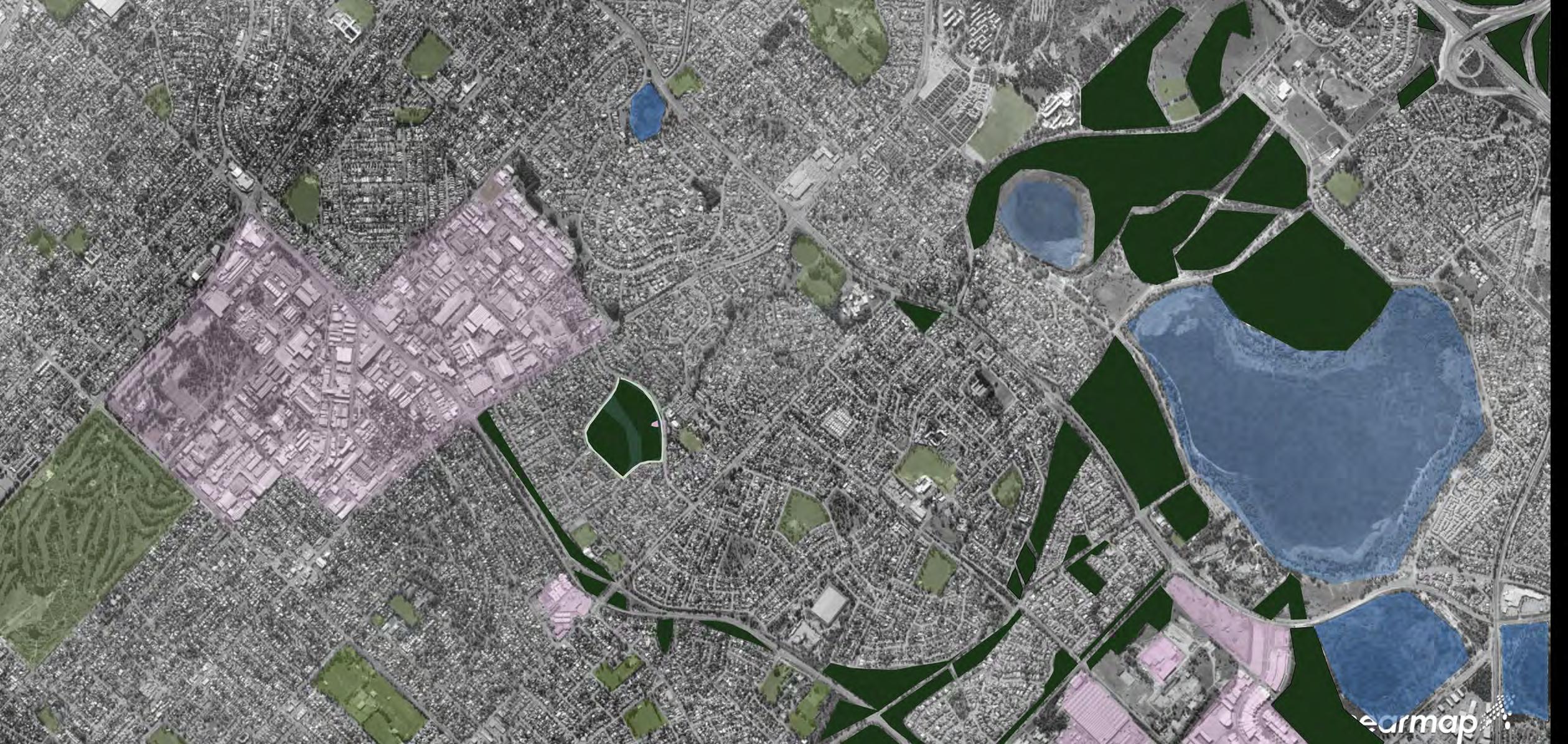

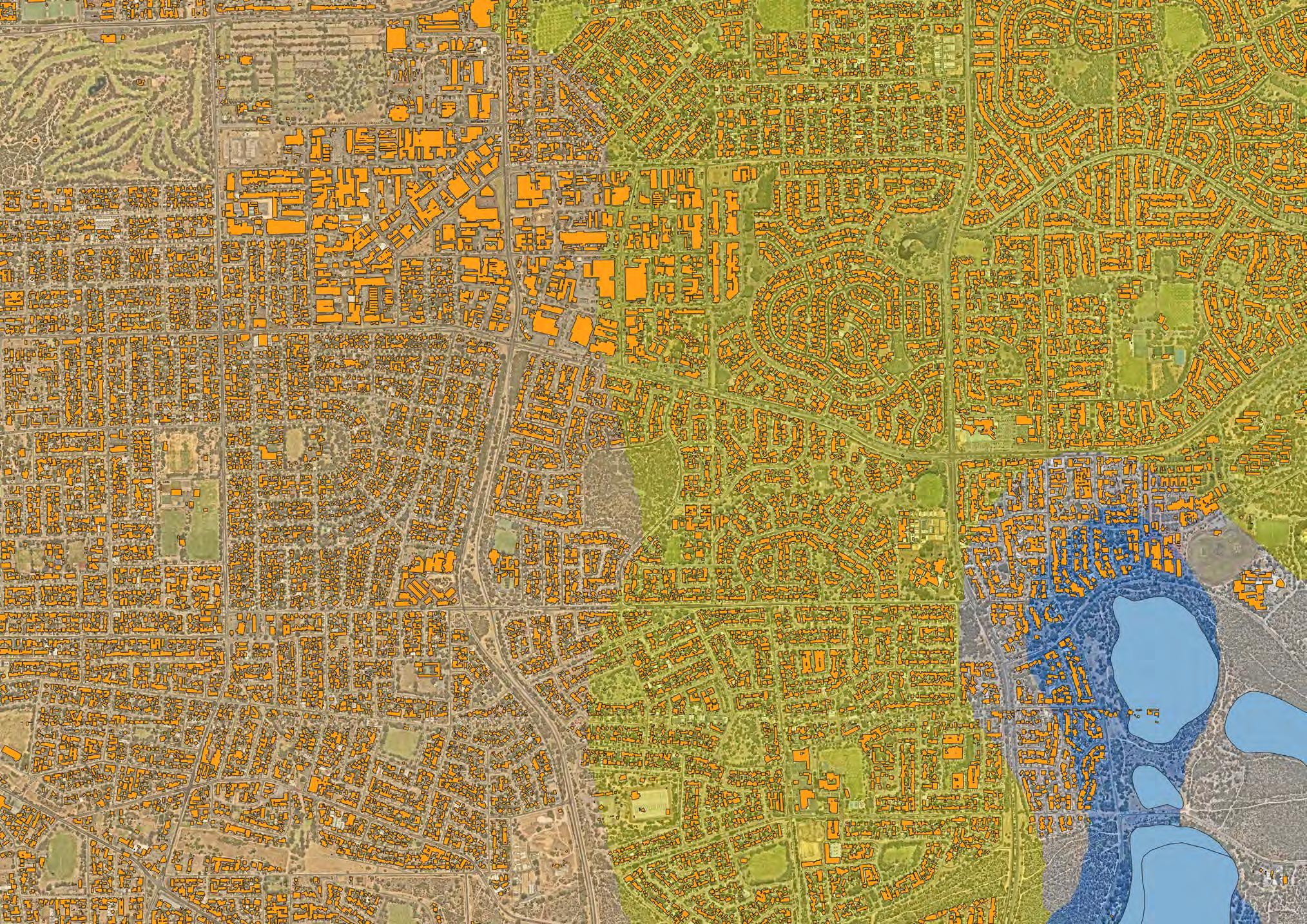

The site selected for this assignment was traditionally inhabited by the Beelier group of the Whadjuk Noongar nation. The adjacent figure shows the chosen site in red and the listed Aboriginal Heritage Sites, 2024. Source: DPLH Heritage Data QGIS

1 2 3 4 5 Stories & Connections 1. Acknowledgement of Country 2. Location Biotopes 3. The Client 2. Site Visit Take Outs 3. Friends of Samson Park 4. Unwelt Perspective 5. Symbols and Transformations The Client - Seasons and Cycles 1.. Daily/Annual/Lifecycle 2. Predator or Prey 3. 12 months to Live or Die 4. Umwelt Section Environmental Mapping & Analysis 1. What have We Lost? 2. Water Locations and Analysis 3. More than Human Experience 4. Human Uses Opportunities and Threats 1. Non Human Perspective 2. Combined Map Strategy & Scenario Options 1. Flight - Damplands and Pools 2. Torpor - Rest 3. Flit - Feed - Procreate Sources & Science 1. Plant Schedule 2. Precedents 3. The Full Story 4. References Materiality & Planting 1. Section Details and Materiality 2. Planting Strategy & Palette 3. HOME - Perspective Masterplan and Focus Areas 1.. Broadscale and Typography 2. Masterolan 3. Delivering to clients needs 1. Flight - Damplands and Pools 2. Torpor - Rest 3. Flit - Feed - Procreate 6 7 8 CONTENTS Stories, Science and Connections

THE HEART OF SAMSON

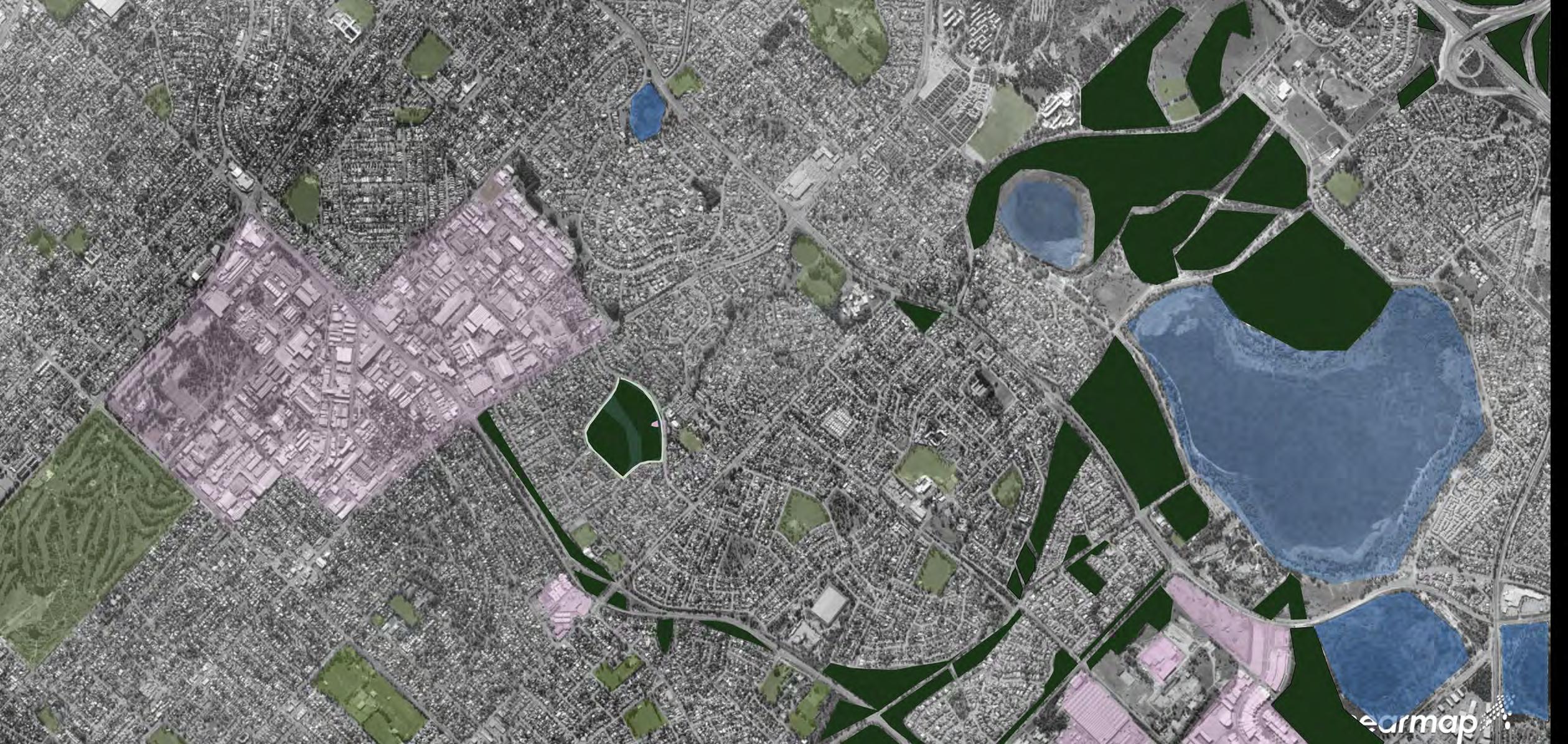

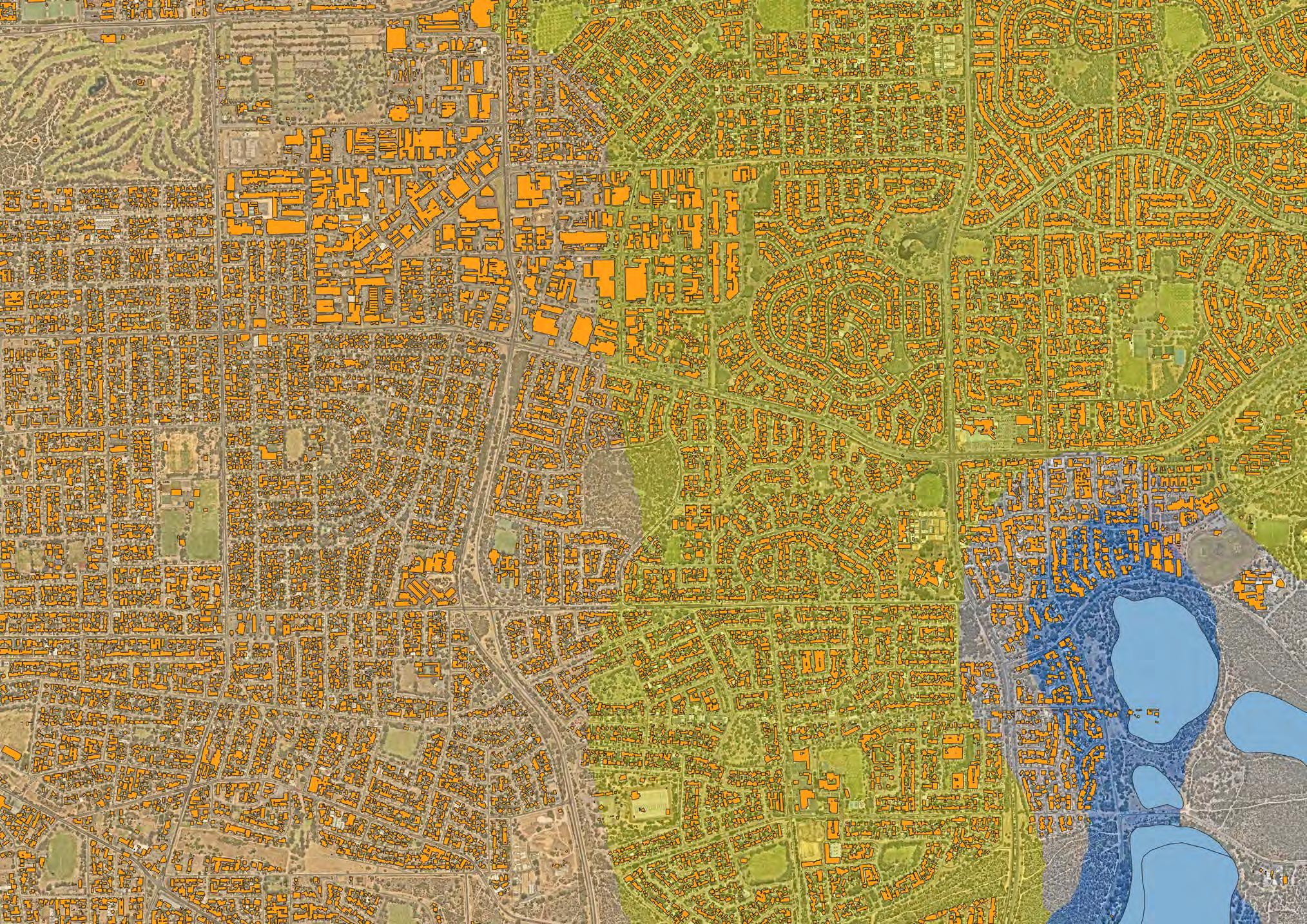

Map and Perspectives Figure 2: Dragon Fly Vision Student’s Graphite Illustration Figure 3: Frog Eye View from AboveStudent’s Graphite Illustration 2 3 Remnant Vegetation Lawns/Turf Programmed Recreation Edge Wetlands Industrial Wasteland Homes and Private Gardens Study Area

Broadscale

Image Source: Nearmaps, July 2009

1:15,000

Sir Frederick Samson Parks, wetlands and adjacent parks and public spaces.

Scale:

SYMBOL

SCALE 1:1

Stories of Transformation, Change of Season, Resilience Speed and Light CLIENT

SCALE 1:1

Stories of Transformation, Change of Season, Resilience Speed and Light CLIENT

- A

OF THE SEASON

From Sunshine to The Rains

Water, Water you can hear the Hoopee callwater needs to flow like natural goodness or else we lose our way..

You can hear the frogs a long way under trying to get a message up.

But fancy cannot work as she would wish. You cannot weigh the moon like so much fish.

54 mAHD 47m AHD 29m AHD 20 m AHD 19m AHD Truth

Wolseley

Song Poems

Paintings

Barry Hill & John

Lines for Bird

and

PERSPECTIVES

UMWELT Hemicordulia tau

Noort/Nooranga/Fire

Dragonfly

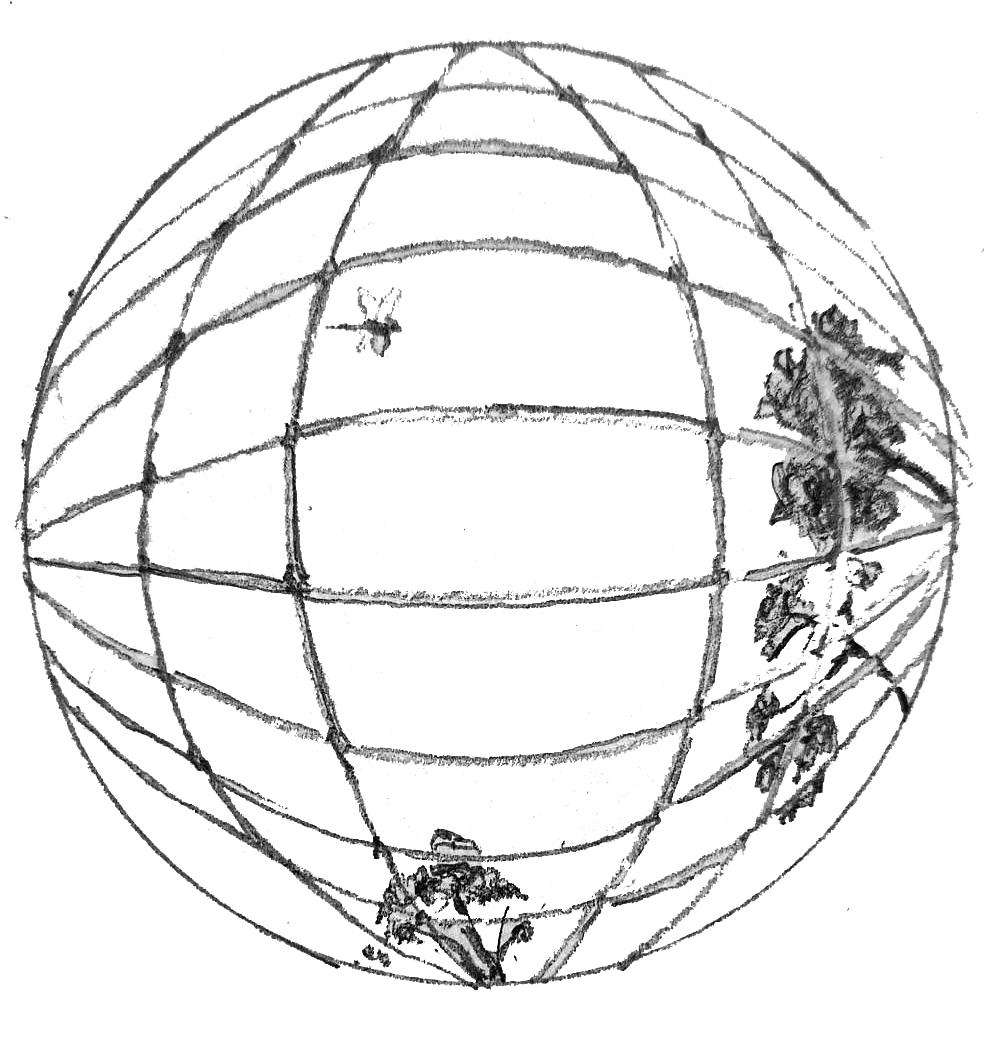

What do you see? “Why I see everything that moves in flicks vivid blinks of colour across my compound eye” said the Dragonfly to the Frog. “Ah” said the Frog to the Dragonfly “My world is a globe of the water and the sky, and your world it seems is the colour between”.

-

- Tau Emerald (Djerakan

Eyes/Devils Needles)

Litoria Moorei - Motorbike Frog (Kwooyar)

Cycads

Zamiaceae Macrozamia fraseri Sandplain zamia Flowering Plants: Dicotyledons

AmaranthaceaePtilotus drummo ndii Narrow leaf mulla mulla

AmaranthaceaePtilotus polystachyus Bottlewashers

Apiaceae Centella asiatica Centella, Pennywort

Apiaceae Eryngium pinnatifidumBlue devils

Apiaceae Xanthosia huegelii Xanthosia

Araliaceae Trachymene pilosa Native parsnip

Asteraceae Cotula australis Common cotula

Asteraceae Lagenophora huegelii Native gerbera

Asteraceae Pithocarpa cordata Tangle daisy

Asteraceae Podolepis gracilis Slender podolepis

Asteraceae Podotheca gnaphalioidesGolden long heads

Asteraceae Senecio condylus Perth groundsel

Asteraceae Waitzia suavolens Waitzia

Campanulaceae Wahlenbergia preissii Native bluebell

Casuarinaceae Allocasuarina fraseriana Common sheoak

Casuarinaceae Allocasuarina humilis Dwarf sheoak

Chenopodiaceae Rhagodia baccata Berry saltbush

Crassulaceae Crassula colorata Dense stonecrop

Dilleniaceae Hibbertia cuneiformis Cut leaf buttercup

Dilleniaceae Hibbertia hypericoides Yellow buttercup

Dilleniaceae Hibbertia racemosa Stalked guinea flower

Dilleniacea Hibbertia racemosa Grey leaf form

Droseraceae Drosera erythrorhiza Red ink sundew

Droseraceae Drosera glanduligera Pimpernel sundew

Droseraceae Drosera macrantha Bridal rainbow

Droseraceae Drosera pallida Pale rainbow

Droseraceae Drosera porrecta Leafy sundew

Ericaceae Conostephium pendulum Pearl flower

Ericaceae Styphelia pallida Kick bush

Ericaceae Styphelia propinqua Beard heath

Euphorbiaceae Monotaxis grandiflora Diamond of the desert

Fabaceae Acacia cyclops Red eye wattle

Fabaceae Acacia glaucoptera Flat wattle

Fabaceae Acacia lasiocarpa Dune Moses

Fabaceae Acacia pulchella Prickly Moses

Fabaceae Acacia saligna Golden wreath wattle

Fabaceae Acacia stenoptera Narrow winged wattle

Fabaceae Acacia willdenowiana Grass wattle

Fabaceae Bossiaea eriocarpa Common brown pea

Fabaceae Daviesia divaricata Marno

Fabaceae Daviesia nudiflora Bitter pea

Fabaceae Daviesia triflora Bitter pea

Fabaceae Gastrolobium capitatum Bacon and eggs

Fabaceae Gompholobium aristatum Yellow wedge pea

Fabaceae Gompholobium omentosum Hairy yellow pea

Fabaceae Hardenbergia comptoniana Native wisteria

Fabaceae Hovea trisperma Common hovea

Fabaceae sotropis cuneifolia Granny bonnets

Fabaceae Jacksonia furcellata Grey stinkwood

Fabaceae Jacksonia sternbergiana Green stinkwood

Fabaceae Kennedia prostrata Running postman

Fabaceae Sphaerolobium linophyllum

Goodeniaceae Dampiera linearis Common dampiera

Goodeniaceae Scaevola canescens Grey fan flower

Goodeniaceae Scaevola thesioides Blue fan flower

Lamiaceae Hemiandra glabra Coastal snakebush

Lamiaceae Hemiandra pungens Snakebush

Stylidiaceae Stylidium schoenoides Cow kicks

ThymelaeaceaePimelea rosea Rose banjine

Violaceae Pigea calycina Wild violet

Flowering Plants: Monocotyledons

Asparagaceae Dichopogon capillipes Chocolate lily

Asparagaceae Lomandra micrantha Small flowered mat rush

Asparagaceae Lomandra nigricans Mat rush

Asparagaceae Lomandra preissii Mat rush

Asparagaceae Lomandra suavolens Mat rush

Asparagaceae Sowerbaea laxiflora Purple tassels

Asparagaceae Thysanotus arenarius Sand dune fringe lily

Asparagaceae Thysanotus patersonii Climbing fringe lily

Asparagaceae Thysanotus sparteus Leafless fringe lily

Asparagaceae Thysanotus triandrus Three stamen fringe lily

Colchicaceae Burchardia congesta Milkmaids

Cyperaceae Ammothryon grandiflorum Large flowered bog rush

Cyperaceae Ficinia marginata Coarse club rush

Cyperaceae Ficinia nodosa Knotted club rush

Cyperaceae solepis cernua Nodding club rush

Cyperaceae Lepidosperma leptostachyum

Cyperaceae Lepidosperma oldhamii Oldham’s sword sedge

Cyperaceae Lepidosperma scabrum Scabrid sword sedge

Cyperaceae Mesomelaena pseudostygia Semaphore sedge

Cyperaceae Morelotia octandra (Tetraria octandra)

Cyperaceae Schoenus clandestinus Carpet sedge

Dasypogonaceae Dasypogon bromeliifolius Pineapple bush

Haemodoraceae Anigozanthos humilis Catspaw

Haemodoraceae Anigozanthos manglesii Kangaroo paw

Haemodoraceae Conostylis aculeata Prickly cottonheads

Haemodoraceae Conostylis candicans Grey cottonheads

Haemodoraceae Conostylis setigera Bristly cottonheads

Haemodoraceae Haemodorum paniculatum Bloodroot, Mardja

Haemodoraceae Haemodorum spicatum Bloodroot, Bohn

Hemerocallidaceae Caesia micrantha Pale grass lily

Hemerocallidaceae Corynotheca micrantha Zigzag lily

Hemerocallidaceae Dianella longifolia Flax lily

Hemerocallidaceae Dianella revoluta var divaricata Flax lily

Hemerocallidaceae Dianella sp. Flax lily

Hemerocallidaceae Tricoryne elatior Yellow autumn lily

Iridaceae Patersonia occidentalis Purple flag

Iridaceae Patersonia occidentalis var. angustifolia

Juncaceae Juncus pallidus Pale rush

Juncaceae Luzula meridionalis Field woodrush

Orchidaceae Caladenia arenicola Carousel spider orchid

Orchidaceae Caladenia flava Cowslip orchid

Orchidaceae Caladenia latifolia Pink fairy orchid

Orchidaceae Caladenia longicauda White spider orchid

Orchidaceae Diuris corymbosa Common donkey orchid

Orchidaceae Diuris magnifica Pansy donkey orchid

Orchidaceae Leptoceras menziesii Rabbit orchid

Orchidaceae Microtis media Mignonette orchid

Orchidaceae Pheladenia deformis Blue fairy orchid

Orchidaceae Prasophyllum giganteum Bronze leek orchid

Orchidaceae Pterostylis brevisepala Short eared snail orchid

Orchidaceae Pterostylis sanguinea Dark banded greenhood

Orchidaceae Pterostylis vittata Banded greenhood

Orchidaceae Pyrorchis nigricans Elephant ears, Red beaks

Orchidaceae Thelymitra vulgaris Slender sun orchid

Poaceae Austrostipa elegantissima Feather speargrass

Poaceae Austrostipa flavescens Yellow speargrass

Myrtaceae Calothamnus quadrifidusOne sided bottlebrush

Myrtaceae Corymbia calophylla Marri

Myrtaceae Eucalyptus gomphocephala Tuart

Myrtaceae Eucalyptus marginata Jarrah

Myrtaceae Hypocalymma angustifoliumWhite myrtle

Myrtaceae Hypocalymma robustumSwan River myrtle

Myrtaceae Melaleuca sp. Paperbark

Myrtaceae Melaleuca viminalis Bottlebrush

Phyllanthaceae Lysiandra calycina False boronia

Proteaceae Banksia attenuata Candle banksia

Proteaceae Banksia dallanneyi Honeypot

Proteaceae Banksia grandis Bull banksia

Proteaceae Banksia menziesii Firewood banksia

Proteacea Banksia nivea Honeypot

Proteacea Banksia prionotes Acorn banksia

Proteaceae Banksia sessilis Parrot bush

Proteaceae Hakea prostrata Harsh hakea

Proteaceae Persoonia saccata Snottygobble

Proteaceae Petrophile linearis Pixie mops

Proteaceae Petrophile macrostachyaPetrophile

Proteaceae Synaphea spinulosa Synaphea

Rhamnaceae Trymalium ledifolium Coastal trymalium

Rubiaceae Opercularia vaginata Dog weed

Rutaceae Philotheca spicata Pepper and salt

Stylidiaceae Stylidium neurophyllumCoastal plain pink fountain

Poaceae Austrostipa hemipogon Half bearded speargrass

Poaceae Austrostipa variabilis Variable speargrass

Poaceae Microlaena stipoides Weeping grass

Poaceae Poa porphyroclados Purple poa

Poaceae Rytidosperma caespitosaCommon wallaby grass

Restionaceae Desmocladus fasciculatusWhorled twine rush

Restionaceae Desmocladus flexuosusTangled twine rush

XanthorrhoeaceaeXanthorrhoea preissiiGrasstree, Balga

Recording started 2 Nov 2020 – Dec 2023

Sir Frederick Samson Park, Samson, City of Fremantle

Native plants in Samson Park recorded by Diana Corbyn and Elizabeth King, 2023

151 native plants recorded (1 cycad, 86 dicots, 64 monocots)

PERSPECTIVES - FRIENDS OF SAMSON PARK Recognition, Restoration, Re-Wild, Recreation

6 5 4

Figure 3-5: Flora at Sir Frederick Samson Park Student’s Own Graphite Illustrations

THE CYCLE OF LIFE

Tau Emerald & Collaborators

Umwelt Section

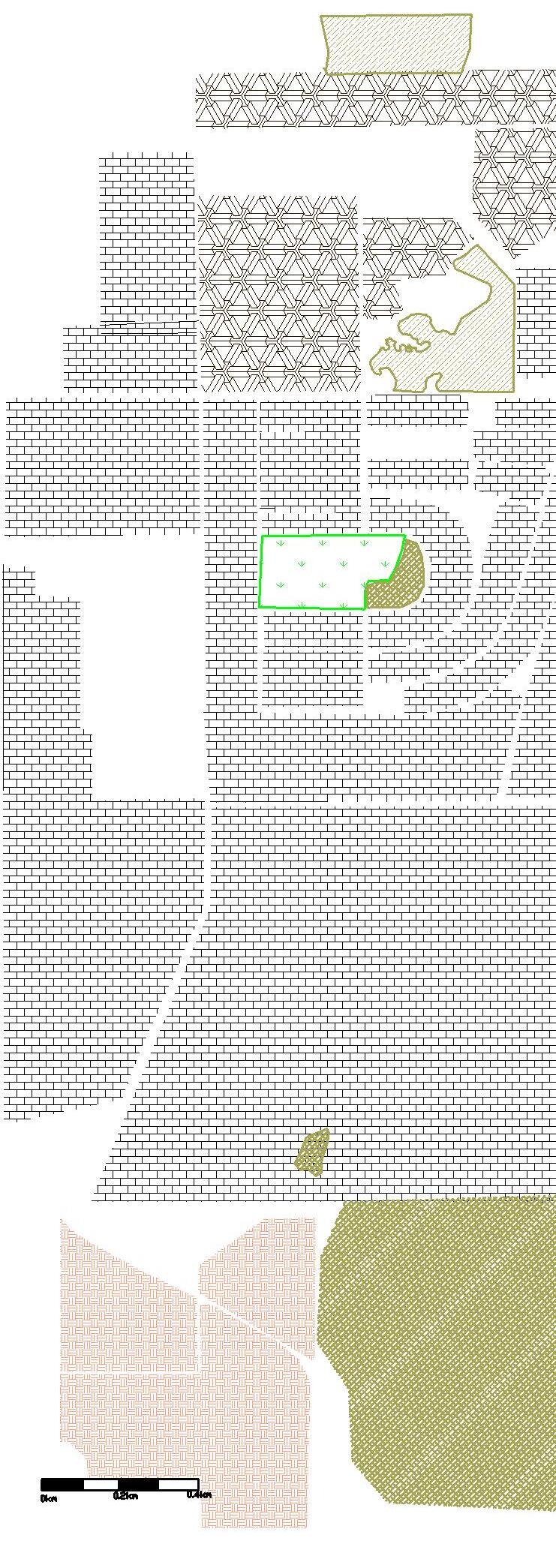

Our Tau Emerald warms up in the sun, finds something to eat, somewhere safe to rest, water to cool off or to find a mate, takes to the sky, zips around, rests, eats, cools, slows down, rests those fire eyes. Sleeps hidden on frond/in foliage up to 4-6 hours per day. Rest State called “Torpor”. Tail to water to cool down. The Stats: Flies up to 70km per, max distance 1,950m.Eats up to 100 mosquitoes in a day. SCALE 1:2000 @ A2 A

NO

More Than Human Experience of the Site - Length of Tau Emerald Flight Path

DAY ZIPPING ABOUT BUT

WATER TO BE FOUND

Figure 8: Photographs Sir Frederick Samson Park Student’s Own

LEGEND Market Garden Industrial Land Use UWA Pine Forest Native Vegetation Sir Frederick Samson Park Zone Sports Oval and POS Housing Wetland Water 1965: Different Natures - Remnant Vegetation 1981: Different Natures - Remnant Vegetation 1953: Different Natures - Remnant Vegetation Scale: 1: 1976: Different Natures - Remnant Vegetation ENVIRONMENT - WHAT HAVE WE LOST? WHAT HAVE WE GAINED? Flight Path 1953-1981

Soil Complexes

The park sits within the defined Geographical Element of the Spearwood Dune system - a coastal limestone Karst formation with water at shallow depths across the Swan River Coastal Plain.

The division between the Cottesloe Complex (shallow yellow and brand sand overlying aeolicanite) and the Karrakatta Complex (deep yellow brown sand overlying aeolianite) run parallel through the centre of the park., This provides for the Tuart, Jarrah and Marri open forest rather than the Bassendean Complex of Banksia and Sheoak-Prickly Bark low forest in low lying areas to the East of the North Lake.

The extensive pine forests across the north-east of the park across the 20th Century is likely to have introduced high levels of Phosphorus and Zinc to the soils as part of its fertilising regime.

North Lake to the East is home to the swamp or Herdsman Complex a low closed forest of Paperbark, Tee and Reeds and Rushes. Here the black organic sands of peaty loams and black clays sit in the shallows of inundation areas suitable for frogs and dragonflies, and nesting birds. This grey and yellow sand dune with swamps is likely to be the soil type in the low lying wetland areas identified on page 9.

Salinity

The ground water salinity in the park sits at 0-500 east, 500-1000 west. Nearby North Lake is experiencing falling pH levels and is at risk of acidification. Its salinity levels are seasonal and vary between 290 and 1060 mg/L, higher levels after evaporation following summer.

ENVIRONMENT -

Scale: 1: 10,000

The surrounding area of the park has been deemed suitable for garden bores illustrating a relatively high quantity and height of ground water.

Threatended and Priority Flora Canopy Cover

A significant amount of historic Tuart, Marri and Jarrah forest to the west of the Park, and Fringing Flooded Gum Woodlands around the Lakes to the East and Fremantle to the West have been cleared due to suburban sprawl through the 1970s and 80s, Pine Plantation Farming and Industries uses. The presence of Jarrah-Banksia Woodland to the East of North Lake, and the Lake’s perimeter also had historic agricultural/horticultural use through the 1950s and 1960s.

Remaining canopy and priority flora is therefore patchy with the Park providing a significant core as part of this ecological mosaic.

The areas within the green boundaries represent 20%-30% remaining canopy at over 3m, while the dark green patches show critical protected canopy at 30%-40%.

Greater than 40% 30- 40% 20-35% 10-15% 5-10% 0% Buildings Study Area DWER Priority Threatened Canopy 2018

MAPPING From Ground to Sky Datasets: WA Government Data Analysed in QGIS

HUMAN USE - A GREEN ISOLATED HEART

12 13 1829 - Colonialisation 1990s Growing industrial area at O’Connor specialising in Food and Beverage production, Transport corridor link to Perth South and Kwinana established 1939 - Park established as Melville Australian Army Training Camp 1955 Army Camp converted to Movie Hall 1971 Samson developed by TM Burke Pty Ltd Prior to colonalisation area was inhabitated by the Beelier group of the Whadjuk Noongar nation.. Figure 12: Listed Aboriginal Heritage Sites, 2024 1870 Lots allocated to Pensioners Guards and used for piggeries, poultry farms, vineyards and horticulture. 1980s Suburban development including public playing fields, schools, public transport along North Lake Road, South St and Leach Highway. 1904-1960 - Surrounded endowed to UWA for pine plantations. 1950-1960 Hilton, Kardinya, Coolbelup started to be developed Reduced tree canopy and significant urban heat surrounding park. Figure 13: Nearmaps Aerial highlighting programmed green spaces Figure 14: Public Transport Routes Around Site

Humans in Suburbia

Indigenous Heritage and Place

The flora, fauna and waters of the Swan Coastal Plan have strong and ancient connections to the people of the Beelier Whadjuk Noongar people. Coolbellup (or North Lake), and the wetlands of this area are highlighted under the State Heritage Act as places of significance. Today, Samson has a neglible population of Aboriginal people, however the adjacent suburb Coolbellup contains 78 Aboriginal or Torres Straight Islander Households (Census 2021), This direct isolation from one of the few remaining pockets of native vegetation within the City of Fremantle is an opportunity that could be considered for this project.

New Wave Suburbia

Between colonisation and the 1970s, Samson was an isolated pocket of remnant native bushland. It’s low lying dampland, sandy soils and distance from the major centres of Fremantle and Perth proved to be a blessing in its preservation. It was used as a Military Camp during WWI and the surrounding area was heavily used for pine forestry and the areas close to the wetlands used for market gardens and horticulture. However from 1971 when the City called for tenders to develop the area, it has been surrounded by a new wave of suburbia, low single story residential homes with to 6m set backs of predominately introduced species and lawn define the park’s perimetre.

Programmed Spaces

Over this same period, there was significant growth in programed space across the area, from football ovals to recreational centres, primary school playgrounds to pocket playground parks and through to large spaces like Royal Fremantle Golf Club and the Netball Centre.

The City of Fremantle has over 70 parks and recreational spaces. However, only Booyeembara Park and Sir Frederick Samson Reserve are predominately unprogrammed open nature spaces. As such they have become popular areas for dog walkers.

HUMAN USE - HOME TO THE PARK

Figure 15: Collage Images Student’s Own SAMSON PARK MCKENZIE ROAD MCCOMBE AVENUE MCCOMBE AVENUE MCCOMBE AVENUE SAMSON PARK SELLENGER SELLENGERAVE

The Human Experience

Extremely high urban heat pocket

High urban heat pockets

AST Drainage - stormwater trapped underground in pipes

Stormwater traps unaccessible

Wasteland egde and perimetre barrier to park

Highly chlorinated water in surrounding swimming pools

Stormwater collection points that could be daylighted

Aquatechniques swimming pool display centre - opportunity for education and natural pools display,

Chlorinated pools - convert to natural pools

Remnant vegetation to preserve and already of natural service to community and species

Stormwater Pits already gather water that maybe suitable for natural collection and sub surface permeability

Swale could create natural barrier from dogs and cats to remnant vegetation

Stormwater pipes underneath sand and surrounding kerbs could be daylighted

Urban heat and climate change significant barrier

Topography creates natural area low point within park

Permeability sand edges in place around park that can be used for swales and improved protection for native renmant vegetation in park.

Significant hard and paved surfaces throughout surrounds of park.

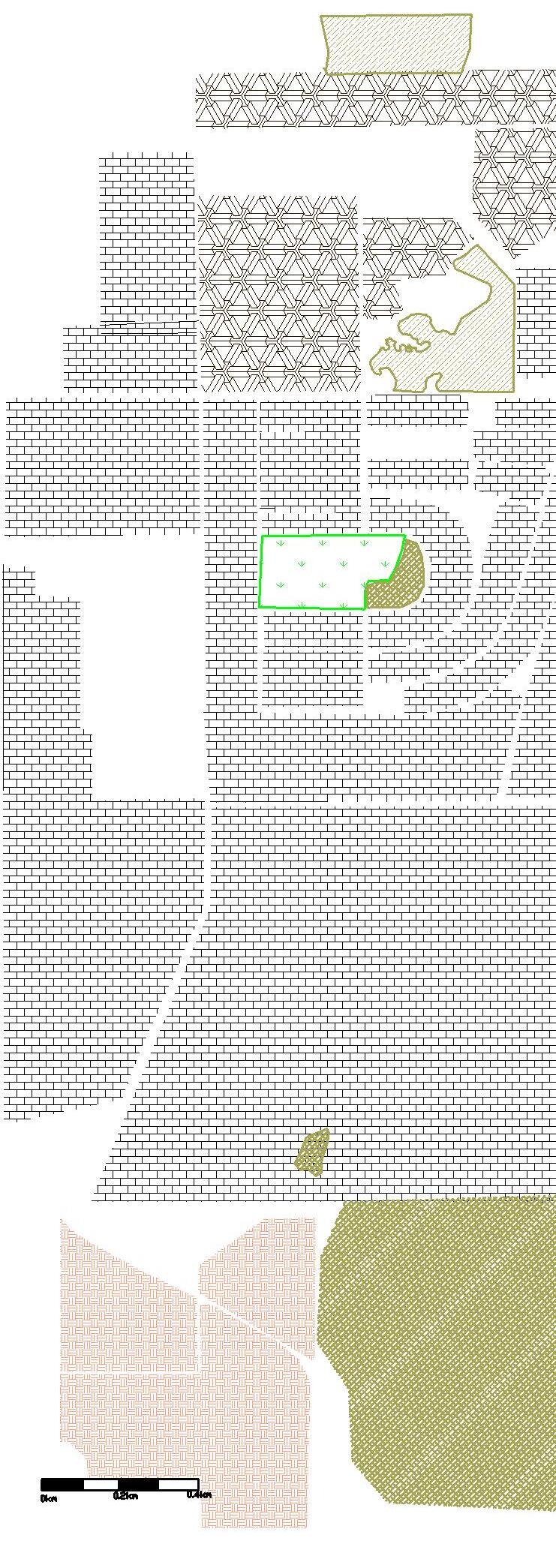

SCALE 1:10000 @ A2

LEGEND

OPPORTUNITIES

Combined

COMBINED

& THREATS

Opportunities & Threats Diagram

FLIGHT

THE PROBLEM: Flight Path 1.2 km Required With Fresh Water Pit Stops THE SOLUTION: Damplands and Pools

The City and Friends of Samson Park to work with commercial provider Aquatechniques to lead of program of change through Samson to convert chlorinated pools to natural pools without chemicals, and verges into a netwrok of damplands. This would provide a number of pit stops for our client, but also develop a cool micro-climate throughout the suburb and into Sir Federick Samson Park.

Education & Display Centre to showcase best practice in DIY and professional conversion of swimming pools to native pools and encourage education on biodiversity and the Tau Emerald’s role as a symbol of water and environmental health.

TORPOR (REST)

THE PROBLEM - Hard Perimeters and No Place to Rest THE SOLUTION - Daylight Drains & Pipes to Perimetre to Create Swale in Wasteland

The sloping typography to the low point in the cente of the park provides the ideal conditions to daylight stormwater drains and pipes to upgrade the perimetre of the park to create a surrounding protective swale in the current sand wasteland around the perimetre of the park. Protecting the native vegetation on the park edge requires a better transition from the European style home gardens into the park to prevent weed and pest invasion.

This Torpor (Rest) site surrounding the park also provides a number of opportunities for female Tau Emeralds to seek shelter from aggressive male Emeralds guarding a single water source within their flight path, as well as seeking shelter from predators.

FLIT, FEED & PROCREATE

THE PROBLEM - Females Need a Place to Flit and Hide from Males Lurking Ready to Mate, Feeds Off Moisquitos and Water Bugs, Mate Above Water and Nymphs Need to Stay in Water Over Rain Season

THE SOLUTION- Remove grated stormwater pits to Create Series of Damplands through Grassed Centre.

In the heart of the park, a designed wetland at the lowest point in the Topography elimates the need for the current stormwater pits and drainage, prevents seasonal flooding across the turf in the park.

The design with surrounding rockery, sedges and reeds also allows for better procreation conditions, nymph protection and a controlled place to develop from Ondata egg through a series of shedding to emerge from the water to take flight.

THE STRATEGY

Somewhere to fly, Somewhere to rest, Somewhere to procreate

Removal of grated stormwater pits and convert to dampland Shade and protection from predators Undderstory and leaf litter for frogs and adolescent dragonflies Rocks to enable nymphs to exit water Water from April to August to lay eggs and allow nymphs to remain in water through metamorphis stages

SCALE 1:15000 @ A2

PLAN WITH CONTOURS & BUILT FORM Sense of Place Lowest Typography Point Current Wetland or Point of Water Daylight Opportunity Water Pipe Flow Direction from High Point to Low

BROADSCALE

MASTER PLAN

An Integrated Approach

Protect Native Bushland

Micro-climate established

Natural Pool Conversions and Daylighting Drainage

Stormwater Capture

Micro-wetland Verges

Urban ReWilding Integration

DELIVERING TO CLIENT NEEDS

Layering Water and Natural Systems, Reducing Introduced Chemicals and increasing Biodiversity

waterways and vegetation Visible water capture Low PH Water Sources allowing for disperal Low lying vegetation near waterways Native vegetation that attracts collaborators preserved

Heathy

WATER CAPTURE - NATURAL POOLS

1: 100

A2

Tau Emerald and Collaborators Section:

@

Inside the Natural Pool & Dampland Education Centre Section 3 Ilustration: 200 @ A2

Proposed Conversion Aquatechnics Pools Stock Road to Heart of Samson Education Centre

Section: 1: 100 @ A2

FLIGHT

MICRO-WETLANDS -

Verge - Human Perspective Section: 1:200@A2

Verge - A New Perspective on Section: 1:200@A2

Redefining the opportunity of a 6m set back Section: Ilustration: 200 @ A2

VERGES TOPHOR (REST)

Verge - Human Perspective Section: 1:200@A2

Verge - A New Perspective on Section: 1:200@A2

Redefining the opportunity of a 6m set back Section: Ilustration: 200 @ A2

VERGES TOPHOR (REST)

RESHAPING THE EDGE

Section 3 Ilustration: 200 @ A2

Section: 1: 100 @ A2

Tau Emerald and Collaborators

Human and Non-Human Occupying the Edge

Sir Frederick Samson Park

Edge Human Perspective Section: 1:200@A2

(REST)

TOPHOR

Sedges and reeds for protection and rest

Rocks to assist nymphs to exit the water

Mud for frogs and therefore tadpoles for Nymphs prey

Stormwater pit daylighted to create indudated dampland

WATER ALWAYS FINDS ITS WAY HOME

Removal of grated stormwater pits and convert to dampland Shade and protection from predators Undderstory and leaf litter for frogs and adolescent dragonflies Rocks to enable nymphs to exit water Water from April to August to lay eggs and allow nymphs to remain in water through metamorphis stages

Open

area for sunlight and warmth

FLIT, FEED, PROCREATE

Use of permeable pavers and subgrade infiltrate provides a cost effective way to reduce Samson’s considerable urban heat and in large wide cul-de-sacs provides additional opportunities for native gound covers and filtering.

A micro-wetland edge to the park and kerb serves an appropriate resting place for invertebrates and there collaborators, but also provides natural biofiltration from the road runoff and pollutants that surround the park. In addition, by creating a biofiltering edge a micro-climate is created that protects the inner remnant vegetation.

Sedges and reeds create a natural layer of bio-filtering, Rocks and boulders are to be placed in situ as retaining, but also providing stepping stones for play and basking rocks for invertebrates and amphibians.

A coconut coil underlay and liner assist with appropriate drainage, with natural typography ensuring water captured flows into the park.

A natural swimming pool is defined by its ability to provide clean natural water that is safe to swim in without the addition of chemicals such as chlorine or salt. The latter pushes the particles and pH levels in the water above what is safe for native invertebrates, particular dragonflies, bees and butterflies.

It uses a circulation system that operates automatically for a set period of time each day to ensure the natural filtration process is maintained and surrounding biofilters that enable biology to clean the pool/pond not chemicals.

The proposed design to be promoted to the Samon community draws on both the texture and colours of the park, as well as the brick and terracotta style homes in the heart of Samon.

A reed bed system biofilters and purifies the water. They also provide shade and keep the pH neutral.

Creating a natural lake style shoreline creates a natural regeneration zone, and together with coconut fibre or coils, and gravel enable a strong subtrate that also serves to naturally filter the water.

See planting palette for appropriate groupings.

SECTION DETAILS & MATERIALITY

CURRENT STATE FUTURE STATE CURRENT STATE FUTURE STATE CURRENT STATE FUTURE STATE CURRENT STATE FUTURE STATE Circulation Pump, Valve, Drain and Skimmer Delivery Pipe Perforated Pipe to Regeneration Zone Swimming Zone with bottom drain Regeneration and biofilteing vegetation Daylight current stormwater pit Sedges and reeds planted for biofiltering Native shrublands for shelter, pollen attractants and tophor Canopy for shade Rocks for basking and providing means of exiting water for frogs, turtles and nymphs Gravel and porous ground cover for overflow and water return to acquifer Liner and underlay to assist with water capture, Rocks to hold micro wetland in during months, provide basking rocks, steppers across and exit assistance Sedges and reeds planted for biofiltering Controlled draining to permeable surface to return water to acquifer and provide sub soil moistore for plant growth Gaps to promote grass or native ground cover growth to reduce heat Permeable driveway and culde-sac paving Subgrade infiltrates via crushed stone base Existing soil Perferated pipe to channel water to micro-wetland

FEELS LIKE HOME

Plant Zone 1: Reedbeds

Pools/Dampland

Ecological Services = filtration, egg disperal, habitat protection fo nymphs/tadpoles, Noongar bush tucker

Plant Zone 2: Sedges

Microwetlands/ Bank

Ecological Services = filtration, protection for juveniles, home to frog collaborators, Noongar bush tucker

Plant Zone 3: Herbaceous Border - Rockery/Edge

Ecological Services = insect and bird attractant, Noongar bush tucker, sunbaking/warming

Plant Zone 4: Understory 1 Samson Shubbery (native)

Ecological Services = insect and bird attractant, cover protection, tophor (rest)

Plant Zone 5: Understory 2

Samson Shubbery (native)

Ecological Services = insect and bird attractant, higher level of cover, cool and shade

Plant Zone 6: Tree Canopy

Ecological Service

Ecological Services = bird collaborators, higher level of cover, cool and shade

Full plant descriptions are provided in the appended schedule on page 24 and 25. Each plant notes its non human attractants (i.e Tau emeral and collaborators - birds, frogs), its historic use in Noongar bush medicine or as a food source and soil or known maintenance notes.

Planting Density per m2

• Plant Zone 1: 7-10 species

• Plant Zone 2: 5-7 species

Plant Zone 3: 3-5 species

Plant Zone 4: 1-2 species

Plant Zone 5: 1 species

PLANTING STRATEGY & PALETTE

Triglochin procerum Salicornia quinqueflora

Carex appressa

Schoenoplectus litoralis

Baumea juncea

Lomandra longifolia Schoenoplectus validus

Chorizandra enodis

Ficinia nodosa

Scaevola crassifolia

Boassiaea preissii Daviesia ulicifolia

Templetonia retusa

Olearia-axillaris Melaleuca incana

Melaleuca fulgens

Macrozamia fraseri

Grevillea ‘Moonlight’

Xanthorrhoea preissii

Diploleana angustifolia

Chorizema cordatum

Kennedia prostrata Hardenbergia ‘white-out’

Grevillea ‘honey gem;

Eucalyptus foecunda Corymbia calophylla (Marri)

Eucalyptus marginata Jarrah)

Eucalyptus gomphocephala (Tuart)

Allocasuarina fraseriana (Sheoak)

Mesomelaena pseudostygia

Melaleuca rhaphiophylla Clematis linearifolia

Marsilea drummondii

Babingtonia camphorosmae

Corymbia ficifolia Banksia menziesii

Zone 1: Reedbeds/ Pools/Damplands 4 Plant Zone 2 Plant Zone 2 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 3 4 3 4 3 6 3 4 3 4 3 3 Plant Zone 2

TOPHOR (REST)

START CLOSE IN

Start close in, don’t take the second step or the third, start with the first thing close in, the step you don’t want to take.

Start with the ground you know, the pale ground beneath your feet, your own way to begin the conversation.

Start with your own question, give up on other people’s questions, don’t let them smother something simple.

To find another’s voice, follow your own voice, wait until that voice becomes a private ear listening to another.

Start right now take a small step you can call your own don’t follow someone else’s heroics, be humble and focused, start close in, don’t mistake that other for your own.

-excerpt from START CLOSE IN from David Whyte: Essentials.

HOME TEACHINGS & LEARNINGS

PLANT SCHEDULE

Designing on Country and Creating Sense of Place

PLANT SCHEDULE

Designing on Country and Creating Sense of Place

Image References (Left to Right)

1. Imae, S; Dikhanov N, Desert 2020 Rain Frog LA+ Creature

2. Federica Fragapane 2021 Thesis Instagram

3. Larch C. 2023 Intersection Cologne Germany - The Art of Mapping, Instagram

4. Gabrielian, A 2020 Shiitake Mushroom LA+ Creature

5. del Águila S, 2019 Carton Printed Topography, Pinterest

6. Munchton, P, 2013 The Patchwork Connection, Issu

7. Hill B and Woodley, J, 2001 Lines for Birds Hoopee Preening, Taman Negara, 8 Lerner, D, Saachti Art, Pinterest

9. Cobe, 2023, The Opera Park

Image References (Left to Right)

1. TRACT Achitects

2. Layout Jocelyn Taruna, University of Melbourne as per LACH5425 Studo References

3. Turtle’s World Jocelyn Taruna, University of Melbourne as per LACH5425 Studo References

4. Cycles Drawing as per LACH 5425 Studio References

5. LOLA Rohan and Liben Island Project - https///lola.land/project/rohan-and-liben-island/ as per LACH5425 Studo References

6. LOLA Wartz-Spoorzone-zwolle - https://lola.land/project/wartz-spoorzone-zwolle/

Image References (Left to Right)

1. Seattle SEA Street Masterplan Examples - https://www.seattle.gov/utilities/about/plans/drainage-and-sewer/stormwater-management-plan 2. As above 3, - Students Own

4. Habib Amanda. “Sustainable House Melbourne.” Homes to Love, 6 Sept. 2016, www. homestolove.com.au/home-tours/sustainable-house-melbourne-4020/. 5-10 - Student’s Own

PRECEDENTS

Image References (Left to Right)

1. Water By Design 2021, Sydney Park Water 2. MDGLA, Riverwalk Werribee Victoria

Issuu Convert your Pool into a Natural System

Brooklyn Greenway Navy Cemetery 5. Natural Swimming Pools - Girl in Water

6. Blumer D, Northern-Sandplains-Garden-Roe-Gardens-WA-Kings Park Botanic-Garden 7. Cheonggyecheon-2008 Korea-Seoul

3.

4.

Graphic + Projects

Hemicordulia tau - Tau Emerald (Djerakan Noort/Nooranga/Fire Eyes/Devils Needles)

A symbol for the season

Djeran season sees a break in the hot weather. A key indicator of the change of season is the cool nights that bring a dewy presence in the early mornings. The winds will also change, especially in their intensity, with light breezes generally swinging from southerly directions (ECU 2024). This is the time the Tau Emerald female enters close to the water and the territorial males, she joins up in a heart shape, mates and lays her eggs by the reeds in the low water waiting the rains.

The Noongar Season ‘Bunuru’ is represented by the colour orange and is the hottest time of the year. Bunuru is the hottest time of the year with little to no rain. Hot easterly winds continue with a cooling sea breeze most afternoons – if you’re close to the coast. Traditionally this was, and still is, a great time for living and fishing by the coast, rivers, and estuaries. Because of this, freshwater foods and seafood made up major parts of the Noongar people’s diet during Bunuru. Bunuru is also a time of the white flowers with lots of white flowering gums in full bloom, including jarrah, marri, and ghost gums. This is the time the Tau Emerald zips about feasting on mosquitoes and living its best life dawn to dusk.

In the park this is the time the striking flower emerges of the female zamia (Macrozamia riedlei). Being much larger than its male counterpart, the huge cones emerge from the centre of the plant with masses of a cotton wool like substance. As the hot and dry weather continues, the seed cones change from green to bright red, indicating they’re ripening and becoming more attractive to animals and vertebrates.

During the season of Djeran - kwiyar (frogs) would be included in the Noongar diet. Not only a source of meat for the Noongar people, but they also provide a significant link in the food chain by contributing to the diet of birds and other animals. Frog numbers are now considered to be an indicator of the health of wetlands.

Seven different species of frogs are commonly found in lakes and swamps on the Swan Coastal Plain motorbike frog, litoria moorei slender tree frog, litoria adelaidensis western banjo frog, limnodynastes dorsalis quacking frog, crinia georgiana clicking froglet, crinia glauerti squelching froglet, crinia insignifera moaning frog, heleioporus eyre”.

Some species inhabit permanent wetlands and others seasonal wetlands on the Swan Coastal Plain. The breeding season for frogs coincide with wetland flooding and maximum water levels. The species geocrinia leai lay their eggs in litter and vegetation beside a wetland, without water, but their tadpoles need water. Heleoporus eyrie and pseudophryne guentheri lay eggs in burrows in or near swamps that become flooded by early winter rain to release the tadpoles. It is then that the Tau Emerald Nymphs emerge for their first metamorphosis and the baby tadpoles become their prey.

A few metamorphosis later and the tables turn, and the emerging dragonflies become the prey of the Frog, as the water subsides and the Frogs multiply in number in the low-lying mud.

As the dragonflies turn into adults they rely on their sight and speed to both prey mosquitoes and insects, but also avoid being the prey and frogs and native birds.

All dragonfly species have excellent vision. They have two large compound eyes, each with thousands of lenses, and three eyes with simple lenses. Each retina contains several thousand photo receptors that collect light and send information about the visual scene to inter-neurons, which further process the information.

Each compound eye is comprised of several thousand elements known as facets or ommatidia. These ommatidia contain light sensitive opsin proteins, thereby functioning as the visual sensing element in the compound eye. But unlike humans, day-flying dragonfly species have four or five different opsins, allowing them to see colours that are beyond human visual capabilities, such as ultraviolet (UV) light. Together, these thousands of ommatidia produce a mosaic of “pictures” but how this visual mosaic is integrated in the insect brain is still not known.

This patterned concentration of opsin types, particularly those sensitive to blue and UV light, gives special advantages to hunting dragonflies. For example, it is thought that the sky appears to be very bright to a dragonfly, thereby providing a clear background against which small moving prey can be easily detected, according to Dennis Paulson, dragonfly expert and director emeritus of the Slater Museum of Natural History at the University of Puget Sound, in Tacoma (Grrl Scientist 2018).

Dragonflies can also detect the plane of polarization of light, which humans cannot do without the aid of sunglasses. The advantages of this capability are unknown for dragonflies, but other insects are known to use polarized light as a sort of “sky compass” by which they navigate. Another visual advantage of the multifaceted eye is a dragonfly’s acute sensitivity to movement. Dragonflies can see in all directions at the same time.

Dragonflies are the strongest flyers in the insect world. Compared to most other insects, dragonflies can fly further and higher than other insects. Their maximum flight speeds are 22 to 34 miles per hour (36 to 54 km/hour), depending upon the species, with an average cruising speed of about 10 miles per hour or (16 km/hour). This is due to the magnificent construction of their two sets of wings. Each wing can move independently of each other, allowing dragonflies to fly in all directions. Their wings are both strong and flexible, giving them the ability to curve, cut through the air and hover even in the strongest headwind.”

Dragonflies can judge the speed and trajectory of a prey target and adjust their flight to intercept prey (Obispo 2022) They have up to a 97% success rate when hunting. They can catch prey mid-air. A single dragonfly can eat anywhere between 30 and hundreds of mosquitoes per day (Obispo 2022).

The maximum recorded distance from the natal site was 1196 m, while the maximum distance traveled between segments was 1128 m, both of which distances were recorded for males. The average distance of females from the natal site was significantly greater than that of males (481 and 446 m, respectively).

Movements directed from the natal site towards terrestrial environments were recorded throughout most of the adult flight period. In contrast, ‘return’ flights (i.e. movements towards the natal site) were recorded only in the second half of summer. The longest time interval between detection of an individual at a terrestrial habitat and its recapture at the natal site was 57d. The appearance of marked individuals at other permanent water bodies occurred only during the last third of the flight period.

In addition to being a symbol of the cycle of the natural seasons, and the end of the rains, dragonflies have inspired creation of new human technology—from drones to artificial visual systems—because of their incredible flight skills and vision. They also serve an important ecosystem role to humans by keeping those pesky insects, such as mosquitoes, that could carry diseases in check.

Habitat Requirements

Adults showed some degree of preference for patches of certain habitat types. Different distributions of individuals among transects was likely a result of the different representation of individual habitat types within the landscape matrix. The most parsimonious model revealed significant differences in preference for certain types of habitat patches. Individuals of both sexes preferred small ruderal patches or abandoned fields over meadows. There was a significant decrease in the number of individuals observed on transects between the second and third periods, which may have occurred because the flight period ended, or because the majority of individuals had returned to the natal site or relocated to other water bodies for reproduction.

Researchers have found dragonflies to be indicators of freshwater habitat quality and changes in habitat quality. Positive relationships between vegetation-based landscape/habitat heterogeneity and species richness of insects are also well documented on regional scales, and also on micro- and meso-scales. For instance, landscape heterogeneity (e.g. within-habitat heterogeneity of vegetation) is a principal factor determining butterfly species richness and habitat heterogeneity is positively associated with stability of butterfly populations and lower risk of extinction (Dolny, A, Harabis, F and Mizicova H 2014).

Similarly, land use and the structure of vegetation adjacent to aquatic habitats (especially important as nocturnal roosts) have a dominant influence on odonate diversity and abundance of adults, and on fine-scale movement behaviours of damselflies. The structure of habitat patches outside of freshwater habitats can be important for major life events, especially juvenile development, and routine movements of imagoes at sexual maturity. The use of terrestrial habitats in adults of this species was long term – even exceeding 3 months, which is at least as long as the period of the larval development. In most dragonfly species, territoriality manifests in the behaviours of males attempting to guard an appropriate territory. Males with established territories have a lower tendency to disperse, but their density is limited by the number of territories available (Dolny, A, Harabis, F and Mizicova H 2014).

A high density of males at a breeding site influences the routine movements of females, who leave the natal site immediately after emergence and return only very briefly for reproduction. Although females moved away from the water body and the recapture rates for females were relatively low, none of our data indicated that females passed the distance that marks a departure from the natal site. Rather, it can be assumed that female behaviour was a reaction to a lack of resources and/or harassment by males. As winged insects, dragonflies have a relatively large radius of action, and the aquatic habitat and immediate surroundings represent a small fraction of the area utilized by these species.

Terrestrial habitats, while not suitable for larval development, provide forage and shelter and so are essential to survival. Macrophytes as keystone structures influencing dragonfly diversity ((Dolny, A, Harabis, F and Mizicova H 2014). The important factor is the absence of continual disturbance during the adult flight period.

The distances of individuals marked in the study points farthest from the natal site were very similar (approximately 1 km) in all directions and on all transects, and did not cross the critical distance, the external borders of the home range were diminished during the flight season, and the numbers of emerged individuals and adults returning to the natal site were comparable, based on exuviae collection and capture–mark–recapture.

It is thought that the ability to perceive polarized light plays an important role in spatial orientation over longer distances and that the overall character of (aquatic) vegetation is important at shorter distances.

Based on field observations articulated in the research, it can be assumed that even less ideal aquatic habitats, such as temporary pools and fishponds, have an important function and can be used as stepping stones for subsequent dispersal ((Dolny, A, Harabis, F and Mizicova H 2014). In addition, the structure of terrestrial habitats appears to have a considerable effect on dragonflies and other water-breeding invertebrates, and thus should be considered and included in the master planning.

Daily life

Odonates do need heat to function and start their day, they warm up by exposing their body to the sun. In the mornings, they rest on various plants while basking in the sun to absorb heat or make their own heat by shaking their wings. Once their body is warm, dragonflies and damselflies spend most of the rest of their day flying around to catch food. In fact, they are almost always moving. If they stop zipping around, they could end up as a snack for some other animal.

Being a good-sized insect, odonates have predators. These include fish, frogs, water beetles, and birds, though many birds are not agile or quick enough to catch the dragonflies.

Odonates are carnivores, i.e. they prey on smaller flying insects like mosquitoes and gnats. It usually eats it in midair, unless the prey is a larger insect, then it lands on the nearest branch to consume it.

The courtship of dragonflies and damselflies often requires aerial contests, as males fight over territory. Females only mate with males that have a territory to defend that is close to a body of water. In both damselflies and dragonflies, the male often guards the female after mating while she lays her eggs in the water. The Tau Emperor dragonfly lay their eggs onto the stems of pondweeds to protect them from being eaten by fish.

The larva that hatches out of the egg is called a nymph. It has wing pads but no functional wings and breathes underwater with gills. The nymph feeds on other insect larvae, tadpoles, and small fish. It is stocky and shorter than the adult and is usually a green-brown colour to help blend in with its watery habitat. Water temperature can determine what time of year the eggs hatch and how quickly the nymph grows and moults.

Like its parents, the nymph is a carnivore. It grabs prey with a unique mouthpart called a mask, which can shoot out and snatch prey in its pincers. All nymphs go through a moulting sequence that can last between a few weeks to several years, depending on the species. Moulting is how insects grow. During a moult, the old exoskeleton sheds to reveal the body that has grown larger underneath it.

Nymphs moult 10 to 20 times, and the time between moults is called an instar. Eventually, the nymph sheds for the last time and emerges as a full-grown adult dragonfly. The new adult needs to allow time for its new, soft exoskeleton to dry and harden before it can fly. During this time, it is vulnerable to predators and tends to stay to close to reeds and vegetation for protection.

Figure 16: Word Art of AI Generated Top 50 Words in Scientific Journals Featuring Dragonflies

FULL STORY SCIENCE & INVESTIGATION

THE

Apace online nursery catalogues. bushland revegetation, Seedbank. 2022, Apace WA viewed 20 September 2022, <https://www.apacewa.org.au/>. Benger, N 2024, Indigenous Health Infonet Art Gallery Page, Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet viewed 10 March 2024, <https://healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au/about/art-gallery/?artid=52>. Beranek, CT, Clulow, J & Mahony, M 2023, ‘Life Stage Dependent Predator–prey Reversal between a Frog (Litoriaaurea) and a Dragonfly (Anaxpapuensis)’, Ecology vol. 104, Wiley-Blackwell, no. 8. Brahic, C 2015, Dragonfly Eyes See the World in Ultra-multicolour, New Scientist, viewed 27 February 2024, <https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn27015-dragonfly-eyes-see-the-world-in-ultra-multicolour/>. BrainFacts 2012, Image of the Week: Dragonfly Eyes, www.brainfacts.org, BrainFacts for Educators Britton, D 2020, Dragonflies and damselflies - Order Odonata, The Australian Museum. Brooker, H & Fiechter, M 2021, Dragonflies threatened as wetlands around the world disappear - IUCN Red List, IUCN, IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Bryne, J 2018, Putting Water to Work, Gardening Australia, viewed 23 April 2024, <https://www.abc.net.au/gardening/how-to/putting-water-to-work/9990524>. Chalmers, L & Wheeler, J 1997, Native Vegetation of Freshwater Rivers and Creeks in South Western Australia, Department of Conservation and Land Management. Collard, N 2019, Whadjuk Trail Network whadjukwalkingtrails.org.au, viewed 28 February 2024, <https://whadjukwalkingtrails.org.au/media/story/dragon-fly>. Coy, R 2022, There Be Dragonflies Hemicordulia Tau TAU EMERALD, www.therebedragonflies.com.au, viewed 28 February 2024, <https://www.therebedragonflies.com.au/dragonflyPages/hemicorduliaTau.html>. de Moor, FC 2017, ‘Dragonflies as Indicators of Aquatic Ecosystem Health’, South African Journal of Science vol. Volume 113, no. Number 3/4. Dolný, A, Harabiš, F & Mižičová, H 2014, ‘Home Range, Movement, and Distribution Patterns of the Threatened Dragonfly Sympetrum Depressiusculum (Odonata: Libellulidae): a Thousand Times Greater Territory to Protect?’, in M Festa-Bianchet (ed.), PLoS ONE vol. 9, no. 7, p. e100408.

Dramstad, WE, Olson, JD & Forman, RTT 1996, Landscape Ecology Principles in Landscape Architecture and land-use Planning Harvard University Graduate School Of Design Washington, DC. Ecoscape & City of Fremantle 1998, Samson Park Management Plan February, City of Fremantle, Fremantle, Western Australia. 2006, Samson Park Management Plan February, City of Fremantle, Fremantle, Western Australia, viewed 28 October 2022, <https://www.fremantle.wa.gov.au/sites/default/files/Sir%20Frederick%20Samson%20Memorial%20Park%20-%20 Revise%20Management%20Plan%20-%20Plan%20RFQ%20ATT%201%20Samson%20Park.pdf>.

Forman, RTT 1999, Land Mosaics the Ecology of Landscapes and Regions, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge New York. Forster, P 2018, WA Inspired Art Quilts Noongar Country, Wetland Glimpses Wetlands of the Swan Coastal Plain, National Museum of Australia, viewed 28 February 2024, <https://patforsterblog.files.wordpress.com/2019/11/wetlands-quiltset-booklet-online.pdf>.

Frapapane, F 2024, Instagram, www.instagram.com, viewed 4 April 2024, <https://www.instagram.com/federicafragapane/?hl=en>.

G Theischinger, Hawking, J & Orr, A 2021, The Complete Field Guide to Dragonflies of Australia CSIRO Publishing, Clayton, Vic. Grey, G 1839, Journals of Two Expeditions, gutenberg.net.au, viewed 7 April 2024, <http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks/e00055.html>.

GrrlScientist 2018, 30,000 Facets Give Dragonflies a Different Perspective: the Big Compound Eye in the Sky, Medium Hansen, V 2024, Bush Foods from Boorloo Wetlands, Perth Festival, viewed 19 May 2024, <https://www.perthfestival.com.au/media/ruti5pcl/bush-foods-from-boorloo-wetlands-vivienne-hansen.pdf>.

Harris, K-L & Wittington, P 2017, Dragonfly Habitats, Life in a Southern Forest. Hill, B & Wolseley, J 2011, Lines for Birds Garnet Publishing Ltd, pp. 62–63. Holliday, & Watton, G 1989, A Gardener’s Guide to Eucalypts Hamlyn Australia, Sydney. Kirkpatrick, A 2023, Suburban Refuge: Designing for Biodiversity in Our Cities, Landscape Australia, viewed 23 April 2024, <https://landscapeaustralia.com/articles/suburban-refuge-designing-for-biodiversity-in-our-cities/#img-2>. La+ Interdiscplinary Journal of Landscape Architecture 2020, ‘Creature’, LA+ vol. 14, no. 2021, viewed 25 February 2024, <https://laplusjournal.com/14-Creature>. Lerner, D 2024, Derek Lerner, Saatchi Art. McHugh, S 2015, Perth Shallow Groundwater Systems Investigation North Lake Hydrogeological Record Series, Department of Water, Perth, Western Australia. Meineke, EK, Youngsteadt, E, Lippey, MK & Katherine C.R. Baldock 2023, Urbanization Shapes Insect Diversity’, Routledge eBooks, pp. 219–246.

Oversby, B, Payne, E, Fletcher, T, Byleveld, G & Hatt, B 2014, Vegetation guidelines for Stormwater Biofilters in the South-West of Western Australia November, Monash University, Perth Western Australia. Payne, EGI, Pham, T, Cook, PLM, Fletcher, TD, Hatt, BE & Deletic, A 2014a, ‘Biofilter design for effective nitrogen removal from stormwater – influence of plant species, inflow hydrology and use of a saturated zone’, Water Science and Technology, vol. 69, no. 6, pp. 1312–1319. 2014b, ‘Biofilter design for effective nitrogen removal from stormwater – influence of plant species, inflow hydrology and use of a saturated zone’, Water Science and Technology, vol. 69, no. 6, pp. 1312–1319. Perron, MAC & Pick, FR 2020, ‘Water Quality Effects on Dragonfly and Damselfly Nymph communities: a Comparison of Urban and Natural Ponds’, Environmental Pollution, vol. 263, no. 2020 (114472). Perth Regional NRM 2021, Tau Emerald • ReWild Perth ReWild Perth, viewed 28 February 2024, <https://rewildperth.com.au/resource/tau-emerald/>. Phillips, A 2005, Water Harvesting Guidance Manual City of Tucson, viewed 21 April 2024, <https://www.tucsonaz.gov/files/sharedassets/public/v/1/government/departments/department-of-transportation-and-mobility/documents/2006waterharvesting.pdf>. Polyakov, M, Fogarty, J, Zhang, F, Pandit, R & Pannell, DJ 2017, ‘The Value of Restoring Urban Drains to Living Streams’, Water Resources and Economics vol. 17, pp. 42–55. Rega-Brodsky, C & MacGregor-Fors, 2023, Birds in an Urban World’, Routledge eBooks, pp. 247–261. San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance 2024, Dragonfly and Damselfly San Diego Zoo Animals & Plants, animals.sandiegozoo.org. San Luis Obispo 2022, 8 Things You Never Knew about Dragonflies, Treehugger, California Polytechnic State University. Seifikaran, M 2021, Urban Design Lab Explore the Avenues of Urban Environment Together !, Urban Design Lab. Stevens, JC, Rokich, DP, Newton, VJ, Barrett, RL & Dixon, KW 2016, Restoring Perth’s Banksia Woodlands UWA Publishing, Crawley, W.A. Tau Emerald (Hemicordulia tau) 2024, iNaturalist Australia viewed 28 February 2024, <https://inaturalist.ala.org.au/taxa/323555-Hemicordulia-tau>. Taylor, M 2023, Bateman Park - Stories of Dragonfly Dreaming exploreparks.dbca.wa.gov.au, viewed 7 April 2024, <https://exploreparks.dbca.wa.gov.au/site/bateman-park>. Thomaz, SM 2021, ‘Ecosystem Services Provided by Freshwater Macrophytes’, Hydrobiologia. Tract Landscape Architecture 2024, Penrith Green Grid Strategy tract.com.au, viewed 23 April 2024, <https://tract.com.au/projects/penrith-green-grid-strategy/>. Uexküll, J von 2001, ‘An Introduction to Umwelt’, Semiotica, vol. 2001, no. 134. Watson, J, Theisinger, G & Abbey, H 1991, Australian Dragonflies CSIRO PUBLISHING. Weller, RJ 2023, The Landscape Project, Applied Research & Design, pp. 78–79.

Whyte D 2020, Start Close In, Essentials, Collection of Poems, Many Rivers Press

Zhiliang, L 2019, 18054 - Bodkin Park Living Stream Design, February, Syrinx Environmental for City of South Perth.

REFERENCES

Image References (Left to Right)

1. Benger, N 2024, Indigenous Health Infonet Art Gallery Page, Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet, viewed 10 March 2024, <https://healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au/about/art-gallery/?artid=52>.

2. Nagula Jarndu Designs, Digital Copy from Original Print

3 + 4 Forster, P 2018, WA Inspired Art Quilts Noongar Country, Wetland Glimpses Wetlands of the Swan Coastal Plain, National Museum of Australia, viewed 28 February 2024, <https://patforsterblog.files. wordpress.com/2019/11/wetlands-quilt-set-booklet-online.pdf>

5. Beranek, CT, Clulow, J & Mahony, M 2023, ‘Life Stage Dependent Predator–prey Reversal between a Frog (Litoriaaurea) and a Dragonfly (Anaxpapuensis)’, 6 7 GrrlScientist 2018 Facets of DragonFly Eye

8. BrainFacts 2012, Image of the Week: Dragonfly Eyes for Educators

9. San Luis Obispo 2022, 8 Things You Never Knew about Dragonflies, 10. eranek, CT, Clulow, J & Mahony, M 2023, ‘Life Stage Dependent Predator–prey Reversal between a Frog (Litoriaaurea) and a Dragonfly (Anaxpapuensis)’, 11. Forman, RTT 1999, Land Mosaics the Ecology of Landscapes and Regions

Verge - Human Perspective Section: 1:200@A2

Verge - A New Perspective on Section: 1:200@A2

Redefining the opportunity of a 6m set back Section: Ilustration: 200 @ A2

VERGES TOPHOR (REST)

Verge - Human Perspective Section: 1:200@A2

Verge - A New Perspective on Section: 1:200@A2

Redefining the opportunity of a 6m set back Section: Ilustration: 200 @ A2

VERGES TOPHOR (REST)