Candidate: Blerim Nika

POLIS Supervisor: Doc. Dr. Arben Shtylla DA Supervisor: Prof. Theo Zaffagnini

External Expert: PhD. Erida Curraj PhD. Sokol Huta Cycle XXXIV

International Doctorate in Architecture and Urban Planning (IDAUP) International Consortium Agreement between University of Ferrara Department of Architecture (DA) and Polis University of Tirana (Albania) and with Associate members 2014 (teaching agreement) University of Malta / Faculty for the Built Environment; Slovak University of Technology (STU) / Institute of Management and University of Pécs / Pollack Mihály Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology.

Blerim Nika IDAUP XXXIV Cycle Adaptive Reuse. Albanian industrial heritage reuse through passive systems in architecture

Adaptive Reuse. Albanian industrial heritage reuse through passive systems in architecture.

INTERNATIONAL DOCTORATE IN ARCHITECTURE AND URBAN PLANNING

Cycle XXXIV

IDAUP Coordinator Prof. Roberto Di Giulio

Adaptive, Reuse. Albanian industrial heritage reuse through passive systems in architecture.

Curriculum: Architecture IDAUP, Topic: Adaptive reuse, Industrial heritage, Energetic retrofit, (Area 08 SSD: ICAR/12)

Candidate Blerim, NIKA

Supervisor POLIS Doc. Dr Arben SHTYLLA (UniFe Matr. N. 148584) (Polis Univ. Reg. N. PL581N080003)

Co-Supervisor DA Prof. Theo ZAFFAGNINI (Years 2018/2022)

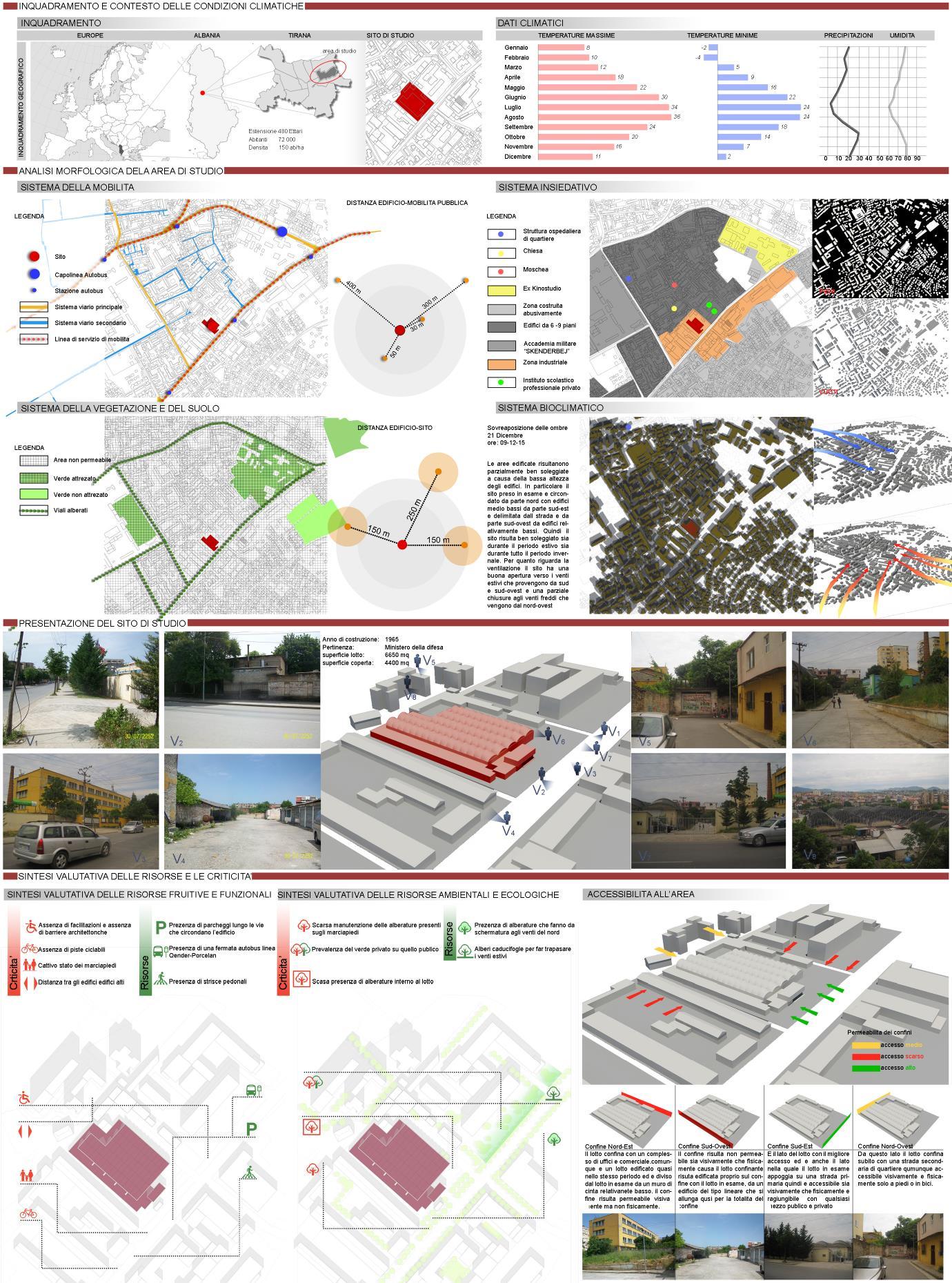

Riuso addattivo. Riuso del patrimonio dell'architettura industriale in Albania tramite l’architettura passiva. Durante il regime comunista, l'Albania chiuse la sua economia al mondo esterno. Come risultato di questa strategia, l'economia albanese ha sviluppato una rete di strutture industriali che ora sono in disuso e sono state abbandonate per quasi 30 anni. Sebbene la demolizione non sia un'opzione, il riutilizzo di questi siti industriali dovrebbe essere considerato una risorsa. Il riutilizzo adattivo degli edifici industriali abbandonati dovrebbe essere considerato un piano d'azione strategico nazionale al fine di rivitalizzare le ex aree industriali mantenendo bassi i costi di costruzione. Il riutilizzo adattivo ha un'importanza enorme nel contesto dello sviluppo sostenibile e delle ripercussioni del cambiamento climatico causato dal precedente disprezzo per il nostro ambiente. L'obiettivo di questa proposta di ricerca è esaminare come il settore delle costruzioni possa riorientarsi per porre maggiormente l'accento sul rilancio degli edifici esistenti piuttosto che sulla demolizione e sostituzione degli stessi.

Il processo di deindustrializzazione dell'Albania ha portato alla perdita di popolazione e all'abbandono di grandi distretti industriali. La sfida di oggi è trovare modi per riutilizzare le aree industriali.Occorrono studi approfonditi sullo stato dell'arte dell'archeologia industriale della città, nonché dibattiti pubblici e azioni strategiche di policy making urbana che attivino politiche territoriali basate sull'evidenza per uno sviluppo sostenibile e integrato, al fine di ripristinare le aree industriali dismesse per generazione in modo creativo e nel pieno rispetto degli antichi valori e tradizioni.

L'obiettivo di questo studio è vedere come la tecnologia può essere applicata a un approccio di riutilizzo per questo tipo di progettazione, nonché i principi in base ai quali potremmo riabilitare strutture industriali abbandonate.

L'obiettivo di questo studio è vedere come la tecnologia può essere applicata a un approccio di riutilizzo per questo tipo di progettazione, nonché il principio in cui possiamo riabilitare strutture industriali abbandonate.

Lo scopo di questa tesi è di testare il quadro olistico sviluppato sul progetto menzionato con tre domande di ricerca sottostanti, che sono:

Abstract_Italiano

Quali sono i principi e le strategie nel contesto tecnologico per il ripensamento degli edifici industriali dismessi all'interno della città?

Come utilizzare lo sviluppo tecnologico sostenibile per preservare le caratteristiche di questa tipologia di architettura?

Il processo di verifica di questa ipotesi è analizzare lo spazio abbandonato nel suo stato attuale, creare uno scenario che incorpori gli approcci sopra menzionati e verificarli attraverso modelli comparativi simulati. L'obiettivo atteso dello studio è quello di produrre linee guida e un nuovo approccio per rivitalizzare il contesto abbandonato e urbano in cui si trova.

Parole chiave: Riuso adattivo, Architettura ex industriale, Conservazione, Archeologia industriale, Conservazione, Architettura passiva, Sviluppo sostenibile.

Adaptive, Reuse.

Albanian industrial heritage reuse through passive systems in architecture

During the communist regime, Albania closed its economy to the outside world. As a result of this strategy, the Albanian economy developed a network of industrial structures that are now in disuse and have been abandoned for nearly 30 years While demolition is not an option, reuse of these industrial sites should be considered a resource. Adaptive reuse of abandoned industrial buildings should be considered a national strategic action plan in order to revitalize former industrial areas while keeping construction costs low.

Adaptive reuse has enormous significance in the context of sustainable development and the repercussions of climate change caused by earlier disregard for our environment. The goal of this research proposal is to look at how the construction sector may reorient itself to put more emphasis on revitalizing existing buildings rather than demolishing and replacing them.

Albania's de-industrialization process has resulted in population loss and the abandonment of large industrial districts. Today's challenge is figuring out ways to re purpose industrial areas. We need comprehensive studies of the state of the art of the town's industrial archaeology, as well as public debates and strategic actions of urban policy making that trigger evidence-based territorial policies for a sustainable and integrated development, in order to restore the abandoned industrial areas for generation in a creative way and in full respect of the old values and traditions.

The goal of this study is to see how technology may be applied to a re-use approach for this sort of design, as well as the principles by which we might rehabilitate abandoned industrial structures.

The versatility of the space distinguishes industrial architecture, and the initial hypothesis is how such aspacemay be recovered,its flexibility, and thehybridizationof functions thatcanbeformed inside it. The objectives of this Thesis is to employ concepts and approaches to review abandoned industrial buildings and identify technological ways to reuse them in the Albanian situation. The growth of industrial structures in space and time, as well as the modified characteristics associated to technological progress, as well as the main functional and technical elements of these buildings, will be investigated.

The aim of this thesis is to test the developed holistic framework on the mentioned project with three underlying research questions, which are:

Abstract_English

Which are the principles and strategies in the technological contest for rethinking abandoned industrial buildings inside the city?

How can we use technological sustainable development to preserve the characteristics of this typology of architecture?

The process for verifying this hypothesis is analyzing the abandoned space in its current state, creating a scenario that incorporates the above-mentioned approaches, and verifying them through simulated comparative model. The study's expected objective is to produce guidelines and a new approach for revitalizing the abandoned and the urban setting in which it is located.

Keywords: Adaptive reuse, Former industrial Architecture, Conservation, Industrial Archaeology, Preservation, Passive Architecture, Sustainable development.

Acknowledgments

I owe a great deal of gratitude to a large number of individuals, including friends and colleagues who have contributed in some way, either directly or indirectly, to our success up to this point.

My first thanks go to my wife and to my son, both of whom have been patient and encouraging during this difficult four year road. I couldn't have gotten through it without their support.

My two advisors, Professor Theo Zaffagnini and Doc. Dr. Arben Shtylla have my utmost appreciation and admiration for all of their hard work and the helpful support that has been offered by them It has been outstanding.

The greatest amount of appreciation to Dr. Llazar Kumaraku, the coordinator of the Ph.D. program at U Polis. His inexhaustible aid in the form of guidance and recommendations, without which I wouldnothavebeenabletoreachtothispoint.Itwouldnotbeappropriateformetodepartwithout expressing my thanks to Professor Besnik Aliaj, who has offered an enormous amount of support not just to myself but to all PhD students.

In closing, I would like to extend my appreciation to the other travel companions, Dr. Nikola Vesho, Dr. Emel Peterci, and Dr. Johana Klemo, with whom I struggled through the challenging and arduous journey.

Thank you to every one

Dedicated to my son.

3 Adaptive, Reuse Albanian industrial heritage reuse through passive systems in architecture Table of contents TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 LIST OF FIGURES........................................................................................................................................... 5 ADAPTIVE, REUSE. ALBANIAN INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE REUSE THROUGH PASSIVE SYSTEMS IN ARCHITECTURE .................................................................................................................................................................... 9 ABSTRACT 9 SUBJECT OF THE SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH 9 THEORETICAL APPROACH 9 HYPOTHESES 10 RESEARCH OBJECTIVES AND LIMITATIONS 11 RESEARCH QUESTIONS 11 METHODOLOGY 12 PRELUDE.................................................................................................................................................... 12 DEFINITIONS. TRYING TO UNDERSTAND THE ADAPTIVE REUSE THROUGH DEFINITIONS.............................. 16 1. HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF ADAPTIVE REUSE APPROACH........................................................ 24 1.1. REUSE BUILDING ADAPTATION. LITERATURE OVERVIW ON BUILDING ADAPTION REUSE THEORY 24 1.2. ADAPTIVE REUSE AND BUILDING CONSERVATION DIALOGUE 26 1.3. THE CONCEPT OF ADAPTIVE REUSE AS AN INNOVATIVE STRATEGY FOR THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT 29 1.4. ADAPTIVE REUSE THEORIES MOST DISCUSSED THEORIES IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE ADAPTIVE REUSE PRACTICE 30 1.4.1. Approaching the Industrial Built Fabric by typology.....................................................................30 1.4.2. Approaching the Industrial Built Fabric by Architecture 31 1.5. APPROACHING THE INDUSTRIAL BUILT FABRIC BY TECHNOLOGY 33 1.6. PROGRAMMATIC APPROACH 34 1.7. INTERIOR APPROACH 34 1.8. INTERVENTION STRATEGIES 36 1.8.1. The concept of monument as a main strategy of preserving former industrial architecture. Palimpsest 36

1.8.2. A classification into strategies 39

1.8.3. The copy and improvement as a strategy for adaptive reuse 40

1.8.4. The model and the copy dichotomy..............................................................................................43

1.8.5. Translation, imitation, and emulation as strategies for intervention...........................................45

1.8.6. The concept of Façadism: working with the dichotomy of interior and exterior 47

1.8.7. The metaphor of the façade. 48

1.8.8. Facadism as a strategy for adaptive reuse of former industrial buildings....................................49

1.9. RE USING THE RUINS: BUILDINGS UPON THE EPHEMERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE FRAGMENTARY FABRIC 52

1.9.1. The ruins as a cultural product of memory 52

1.9.2. Re using the ruins: informal reuse & vernacular adaptations 53

1.9.3. Reusing the consolidated ruin.......................................................................................................56 1.9.4. Staging the ruin as a strategy for adaptive reuse.........................................................................59

1.9.5. Evolving strategies 60

1.10. URBAN REGENERATION THROUGH ADAPTIVE REUSE 62

1.11. INDUSTRIAL ARCHITECTURE HERITAGE AND ITS CONTRIBUTION IN URBAN PLANNING 62

1.11.1. From old typologies to new typologies .........................................................................................68 1.11.2. Once brown fields to neighborhoods 69 1.11.3. Adaptive re use as for new housing typology 70 1.11.4. Former abandoned industrial sites as landscapes & urban parks ................................................72 1.11.5. Vernacular approach of adaptive reuse........................................................................................80 1.11.6. From bottom to top adaptive reuse. Communities on the rise. 81 1.11.7. The formalism and under the influence of spontaneous adaptive reuse. 83 1.11.8. Adaptive reuse as a tool for urban regeneration..........................................................................85 1.12. DEFINITIONS OF VALUES AND SELECTION CRITERIA 87 1.12.1. Criteria of authenticity 87

4

.......................................................................................................................................................

2. ALBANIAN INDUSTRIAL ARCHITECTURE HERITAGE ........................................................................ 89 2.1. HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF ALBANIAN INDUSTRIAL ARCHITECTURE 89 2.2. ADAPTIVE REUSE AS AN APPROACH TO RE PROPOSE FORMER INDUSTRIAL BUILDINGS 91 2.3. ADAPTIVE REUSE PRACTICE IN ALBANIA THROUGH CASE STUDIES TIRANA CASE STUDY, COMPARATIVE APPROACH 92 2.3.1. Tirana as an former industrial city 93 2.3.2Case Study selection criteria

2.3.3.

Water Turbine building.....................................................................................................

2.3.4. EX MISTO MAME 111

Ex Textile Factory ‘Stalin’

typography of

People Army

Comparison Model......................................................................................................................

PART 2

89

96

Former

99

2.3.5.

121 2.3.6. Former

Albanian’s

129 2.3.7.

139

2.3.8. Conclusions 142

2.3.9. About Contest and morphology 142

2.3.10. About the values transition.........................................................................................................143

2.3.11. About collective memory ............................................................................................................144

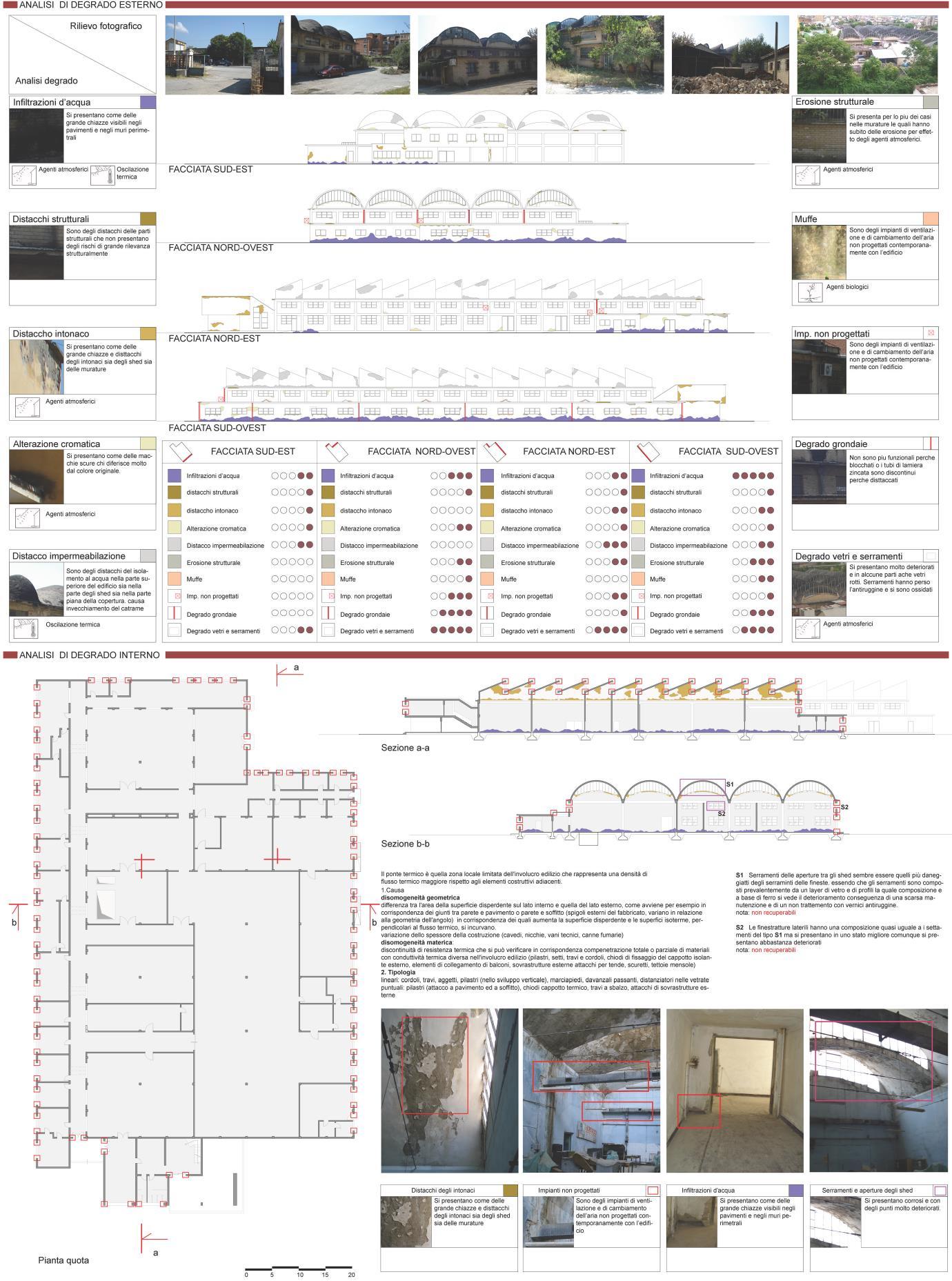

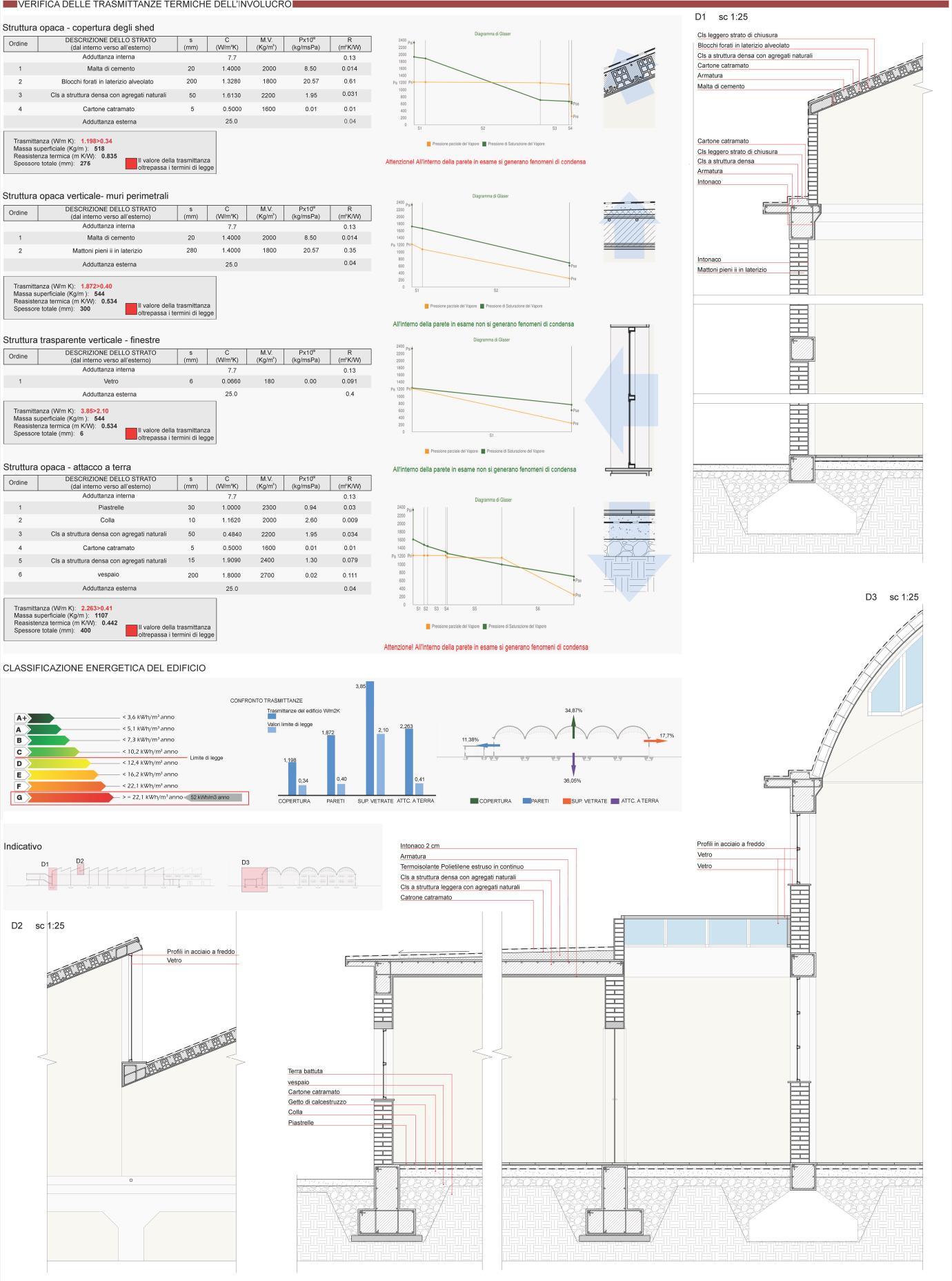

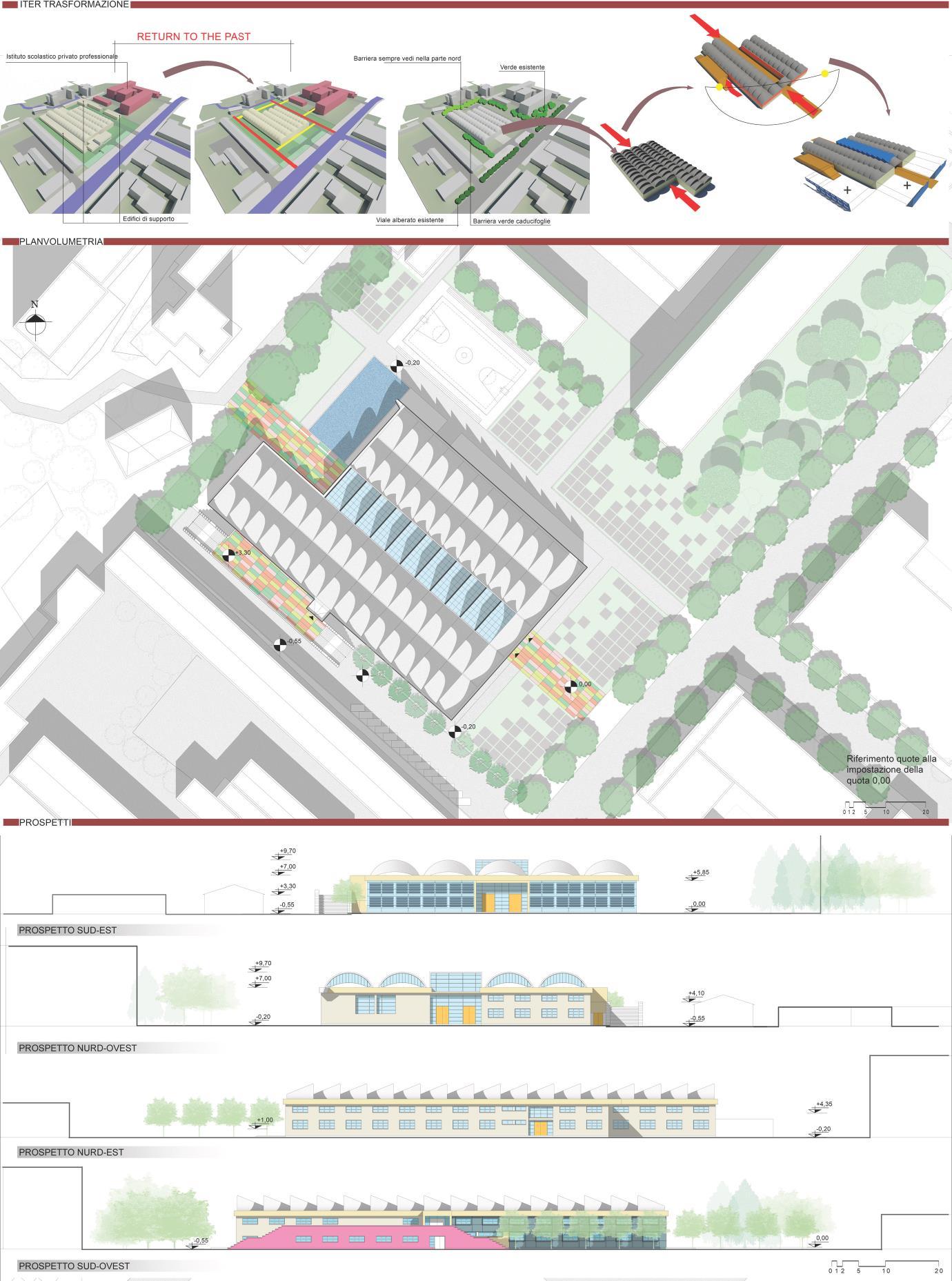

2.3.12. About Energetical retrofit 146

List of figures

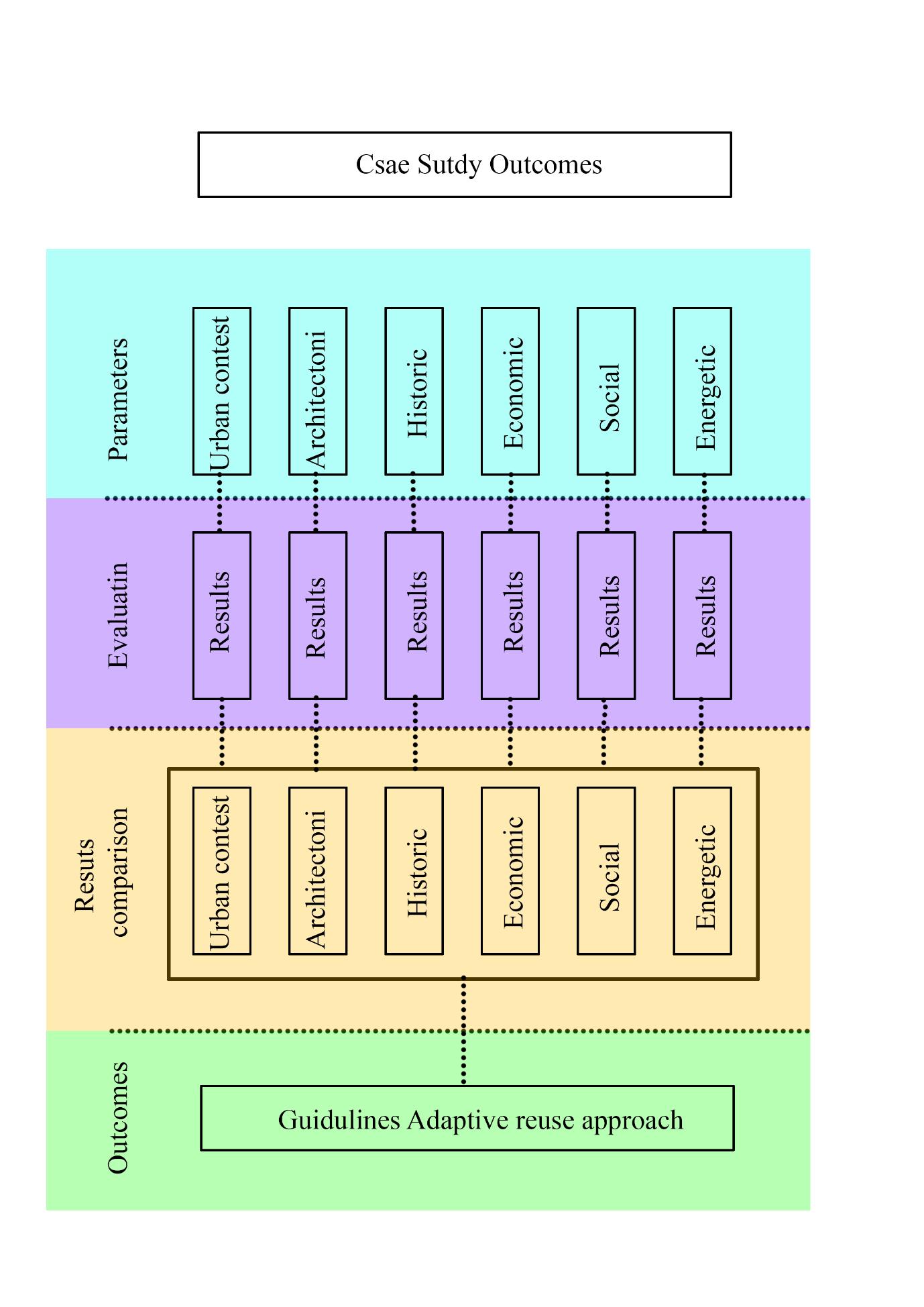

Figure 0.1 Methodology diagram. Credits Author 12

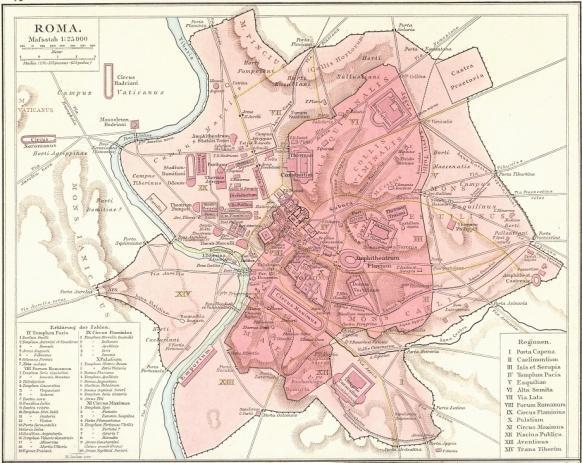

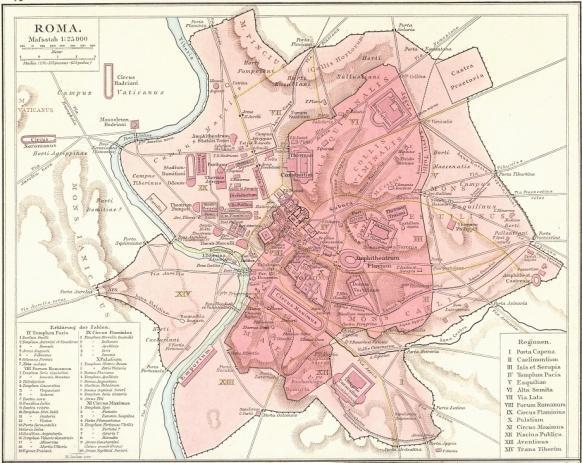

Figure 1.1. Aincent rome map. Source wikiedia 24

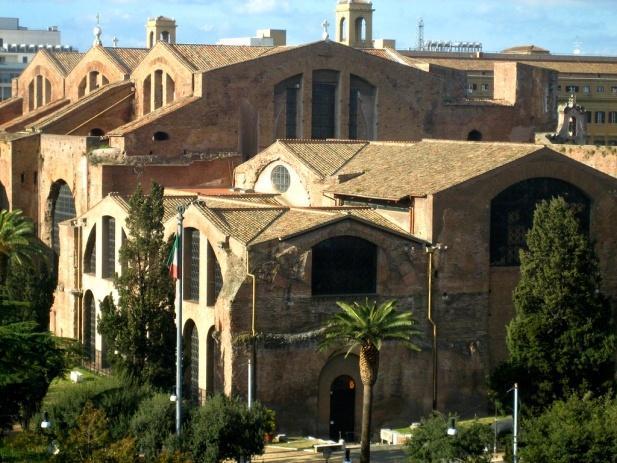

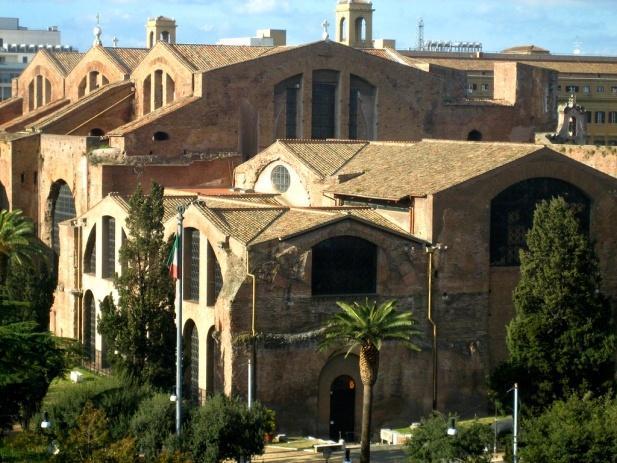

Figure 1.2 Dioclecian Baths. Source Wikipedia......................................................................25

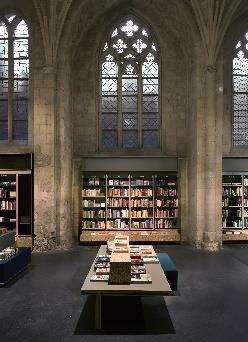

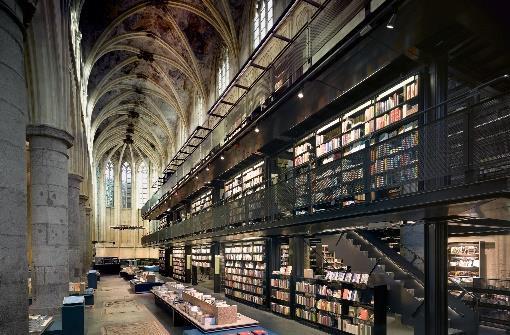

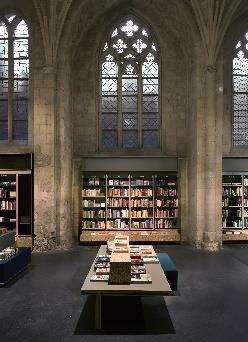

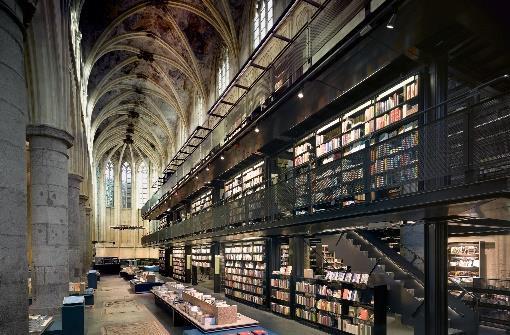

Figure 1.3 Selexyz Dominicanen Bookstore 37

Figure 1.4 The Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus, a Greek manuscript of the Bible from the 5th century, is a palimpsest 37

Figure 1.5 Caixa Forum Madrid, Herzog & De Meuron, Foto Simon Garcia.........................38

Figure 1.6 Tate Modern, Bundeswehr Military History Museum, Fondaco Dei Tedeschi.....41

Figure 1.7 Park Avenue Armory, Herzog & de Meuron; Neues Museum, David Chipperfield Architects.................................................................................................................................41

Figure 1.8 Liverpool Philharmonic, Modern Tate Britain, and Sir John Soane's Museum, Caruso St John Architects........................................................................................................42

Figure 1.9 a.Caravaggio Entombment of christ, b.Rubens Deposition ...................................44

Figure 1.10 OFF Poitrkowska in Lodz 55

Figure 1.11 OFF Poitrkowska in Lodz ....................................................................................56

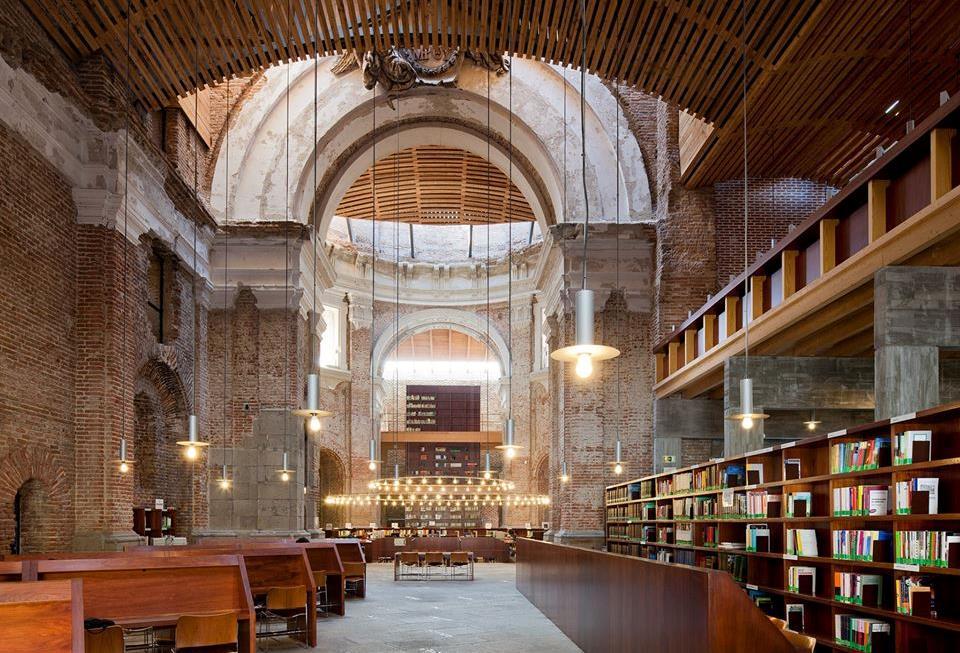

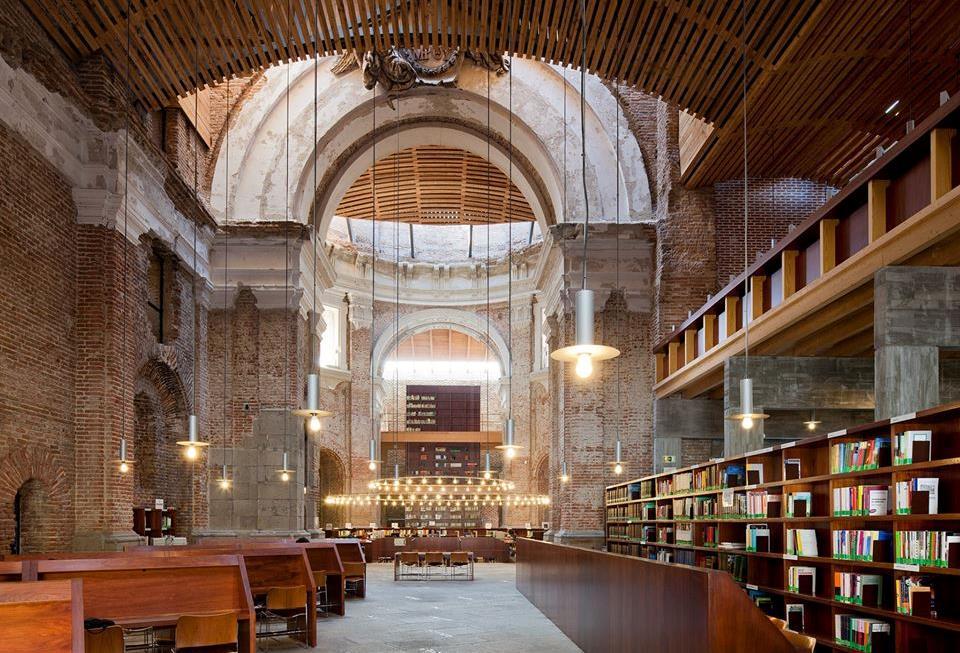

Figure 1.12 Escuelas Pias church ruins, Madrid 57

Figure 1.13 Escuelas Pias church , Madrid. Interior................................................................58

Figure 1.14 Amsterdam Westergasfabriek 74

Figure 1.15 Amsterdam Westergasfabriek Plan 75

Figure 1.16 Parc DellaVillette, Bernard Tschumi, Author Sophie Chivet ..............................76

5

3. FINAL CONCLUSIONS ...................................................................................................................149 4. FURTHER DISCUSSIONS................................................................................................................151 5. BIBLIOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................................153 BIBLIOGRAPHY..........................................................................................................................................153 6. ANEX 1 ........................................................................................................................................158

Figure 1.17 Parc DellaVillette, Bernard Tschumi, Author William Beaucardet 76

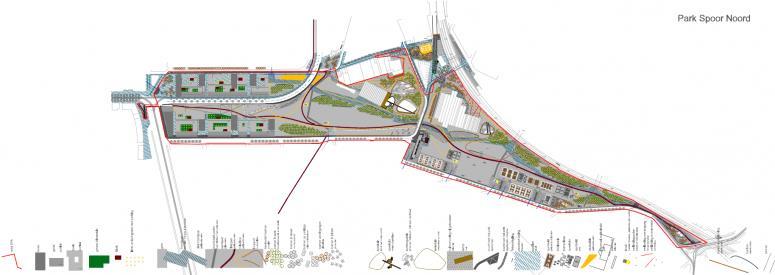

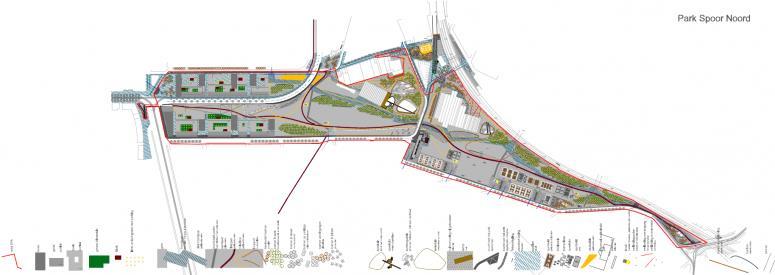

Figure 1.18. Park Spoor Noord development plan ..................................................................77

Figure 1.19. Park Spoor Noord converted building.................................................................78

Figure 1.20. The High Line in New York City 79

Figure 1.21 New York highway requalification......................................................................80

Figure 1.22 Tacheles sculpture garden. Image via kunsthaus-tacheles.de 82

Figure 1.23 Staircase at Kunsthaus Tacheles...........................................................................83

Figure 2.1 Mao Tse Tung Textile factory, Berat,Source Archive...........................................90

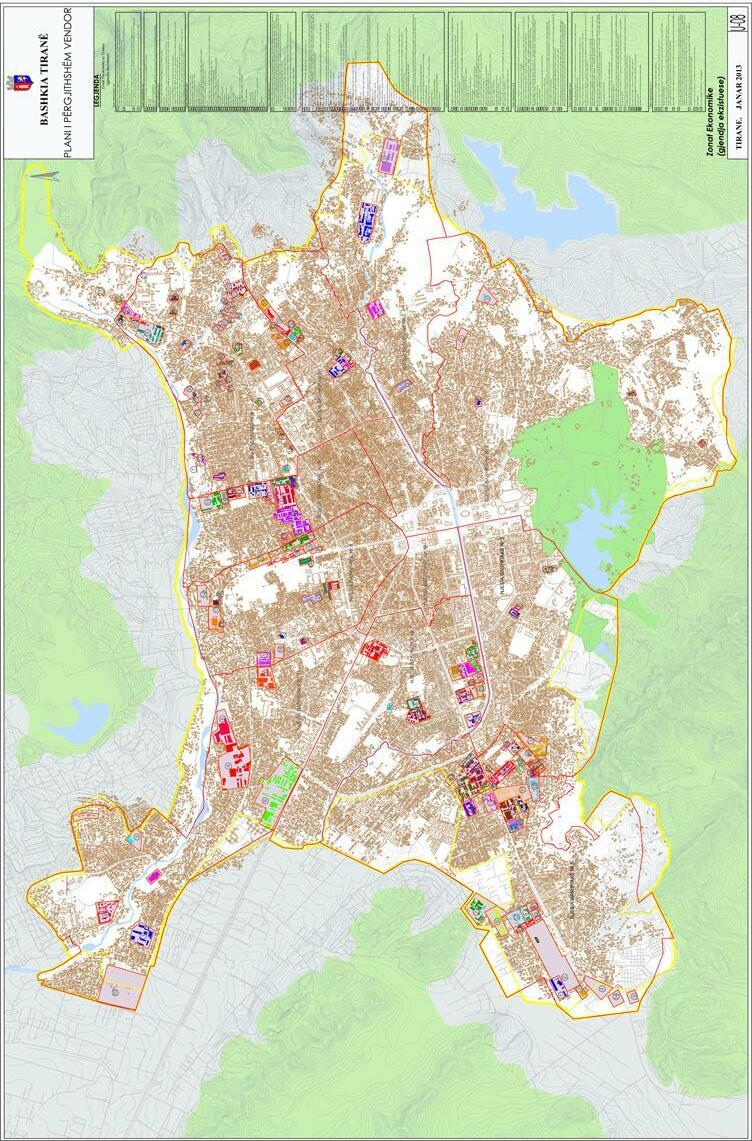

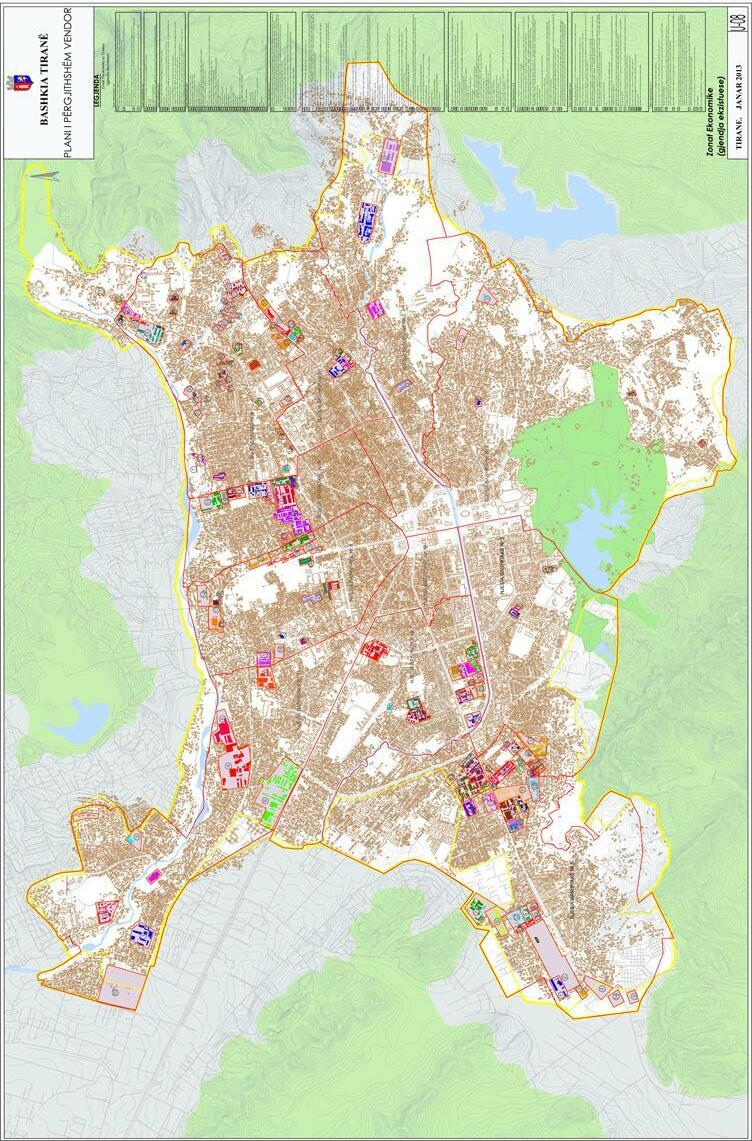

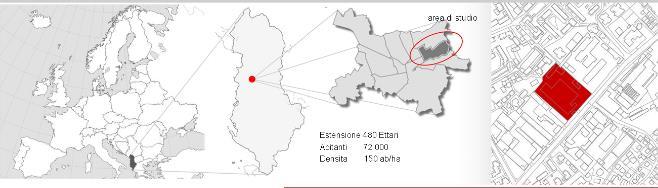

Figure 2.2. Industrial areas of Tirana. Source Tirana Municipality 94

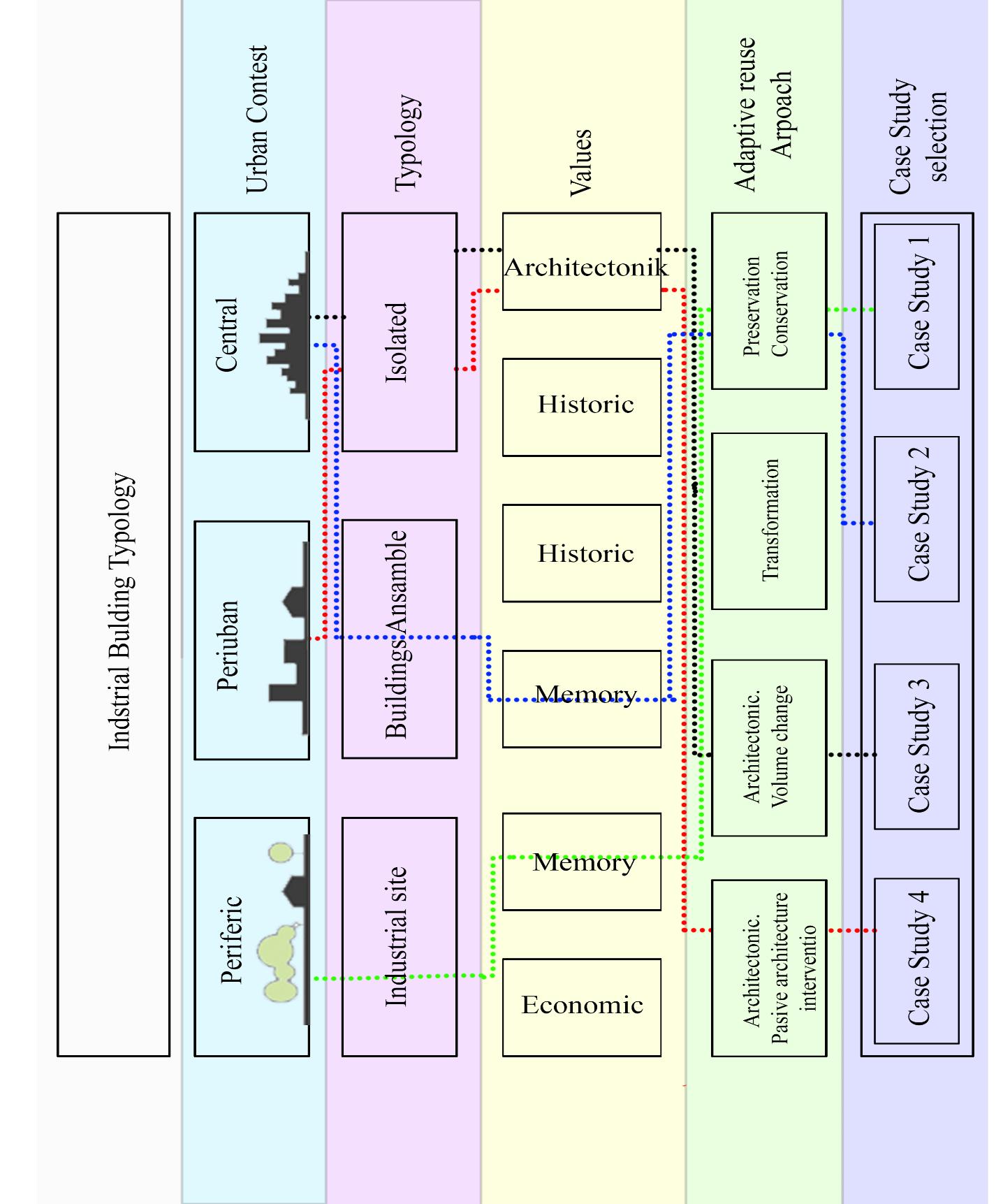

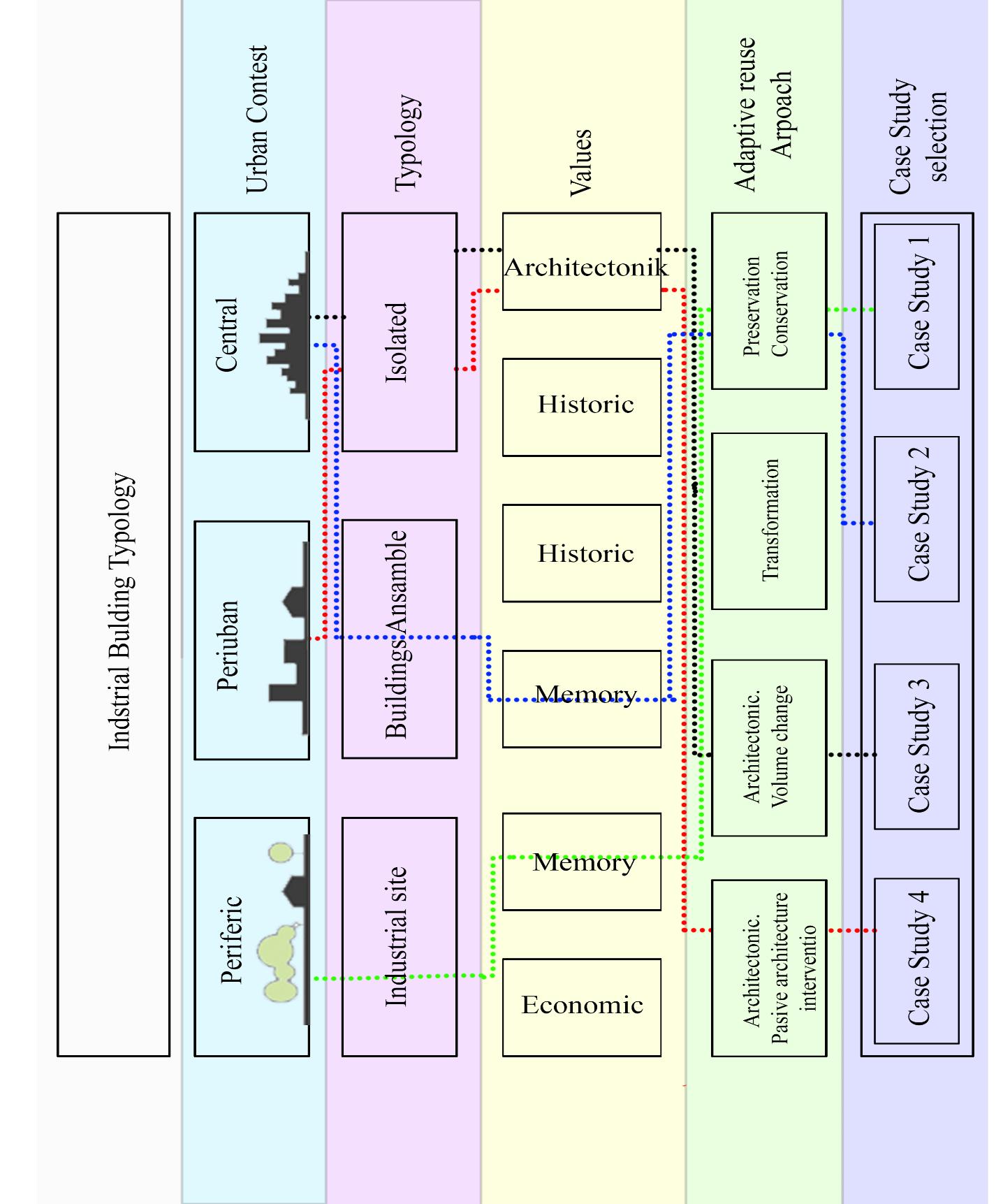

Figure 2.3. Methodology Diagram. Credits Author.................................................................96

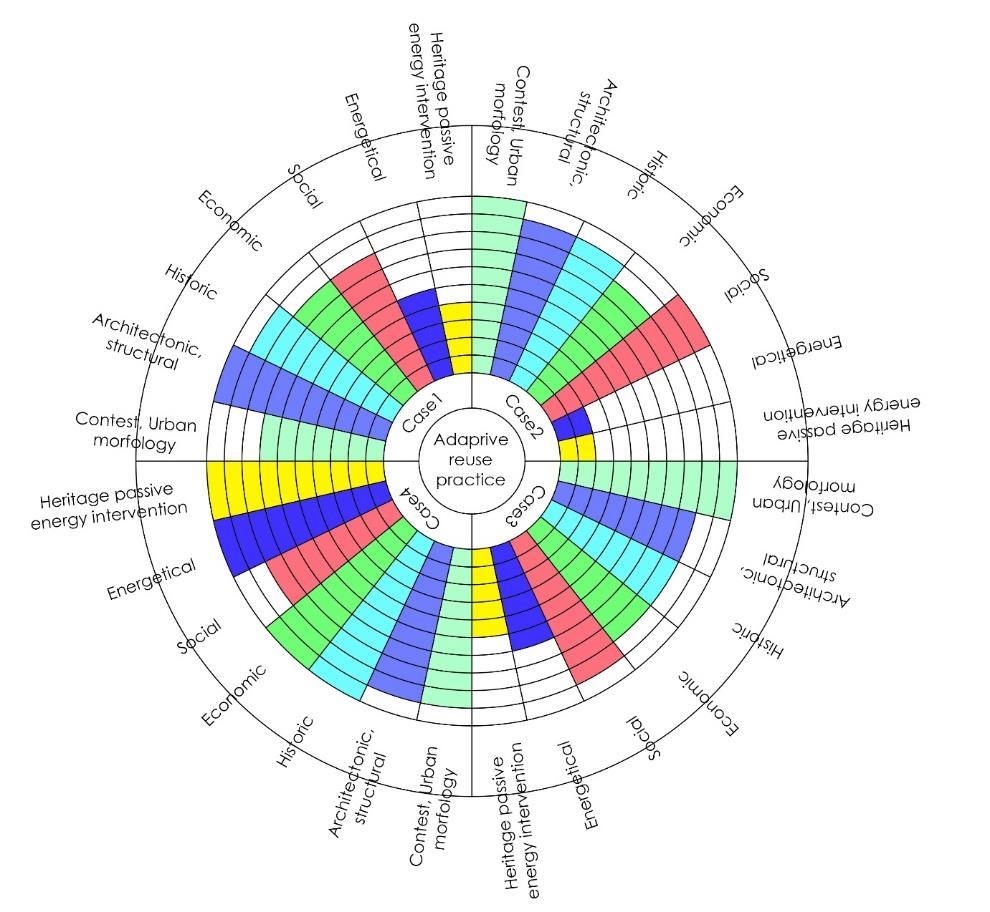

Figure 2.4. Case Study Identification Diagram. Source Author. 97

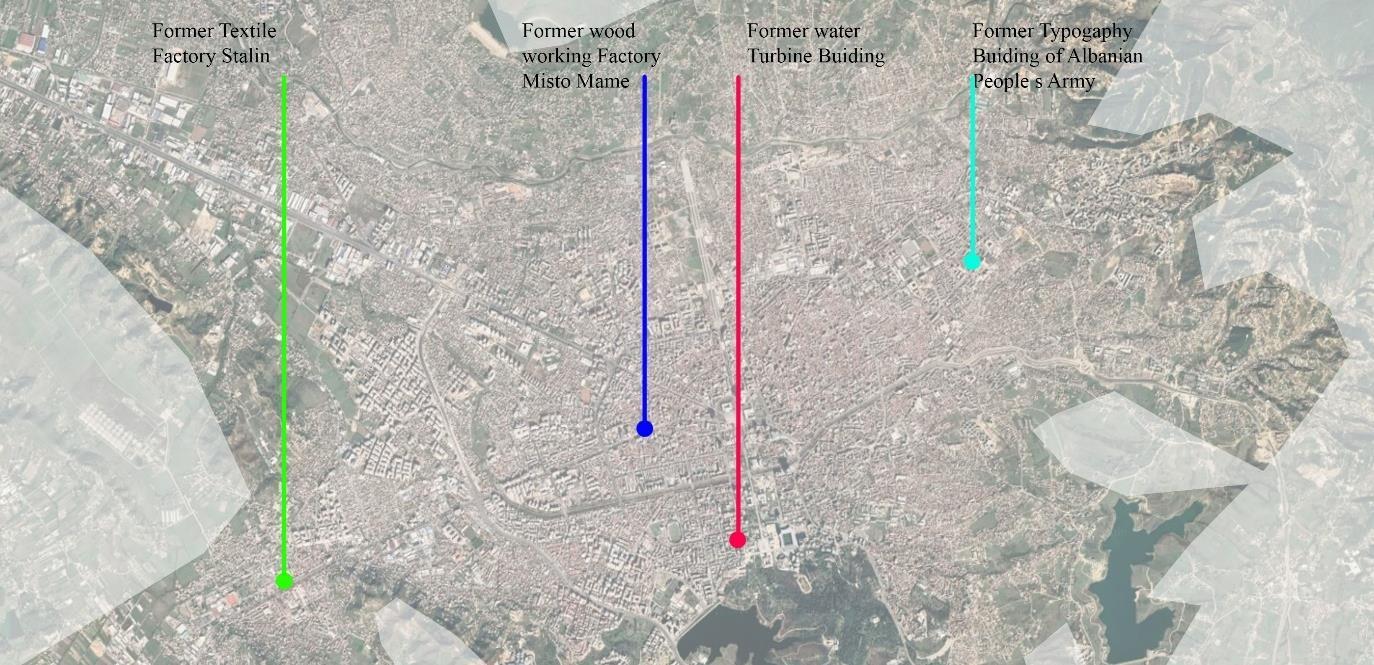

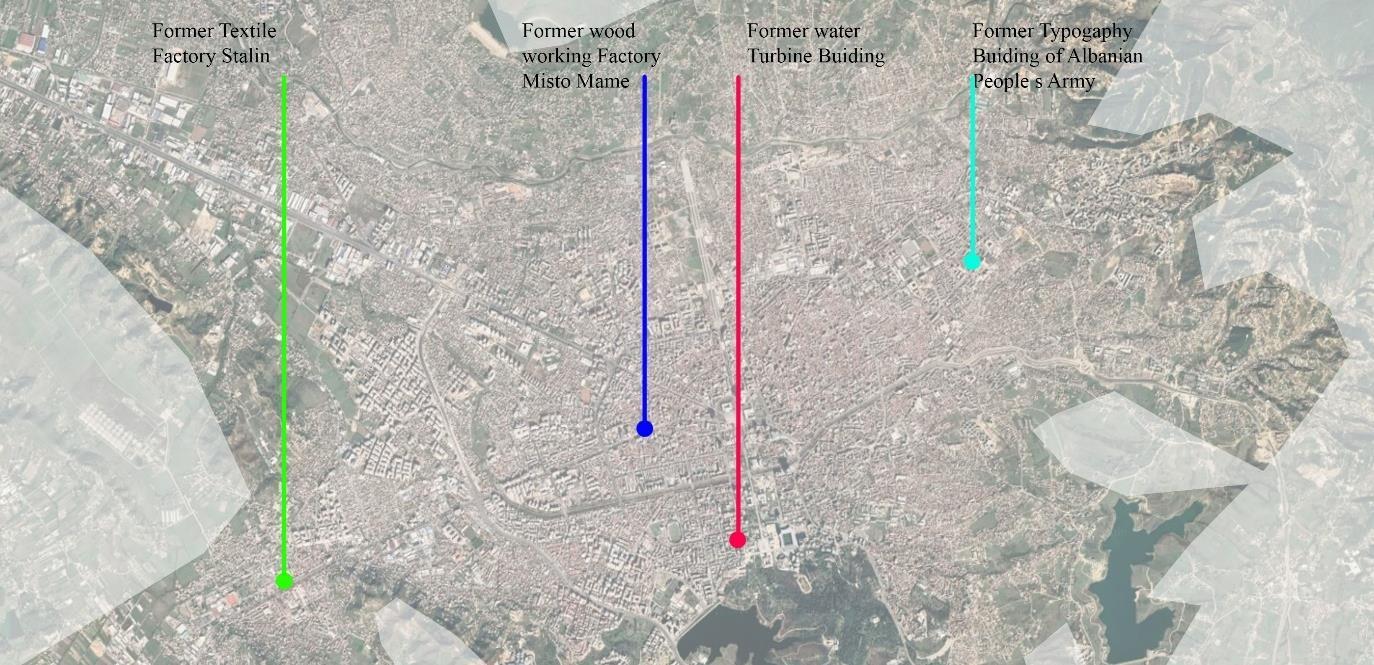

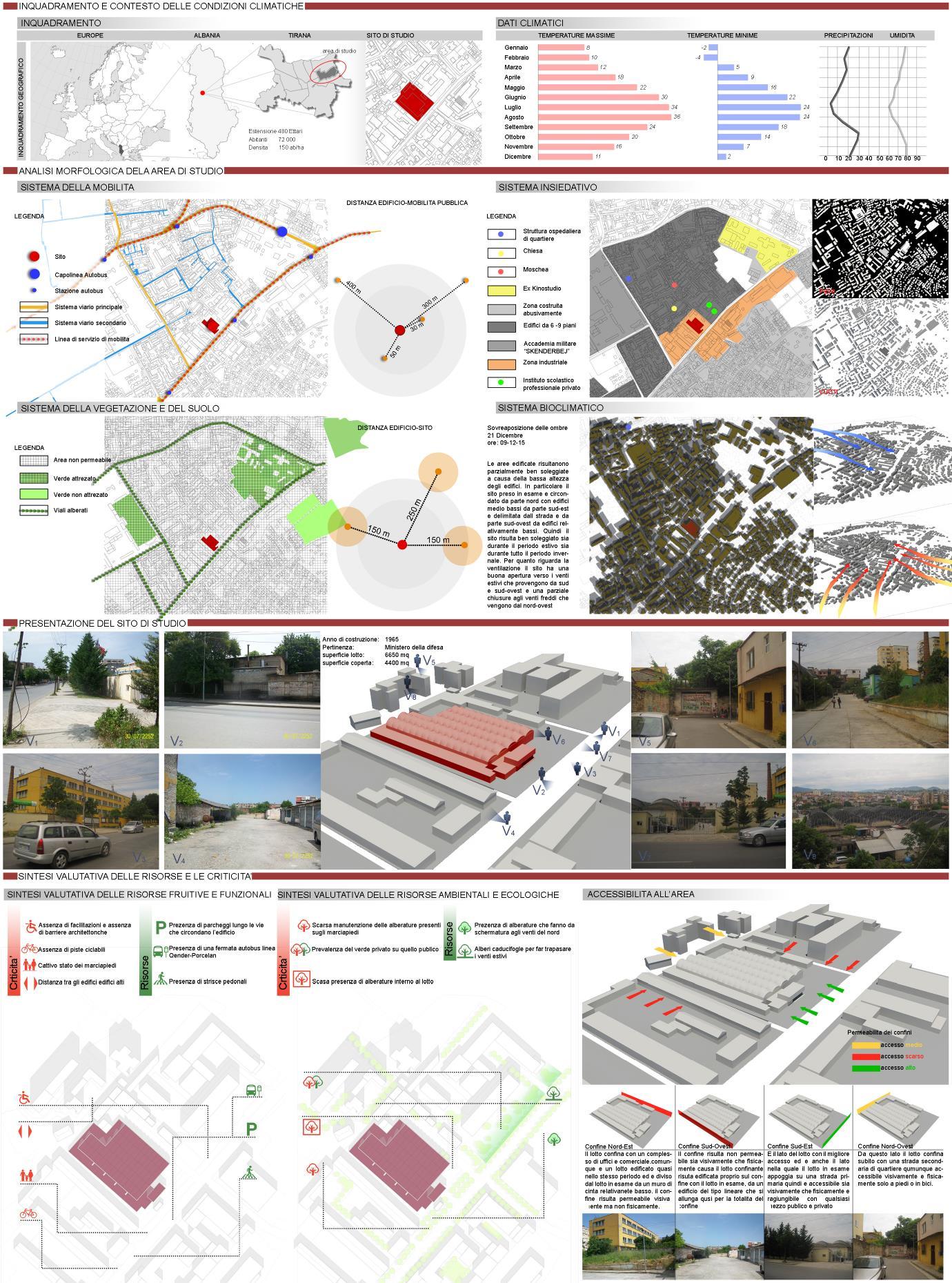

Figure 2.5. Case Study geografy..............................................................................................98

Figure 2.6 Urban situation of the site. Source Asig Geoportal Albania. Worked Author.......99

Figure 2.7 Urban Morfology comparison Source Asig Geoportal Albania. Worked Author100

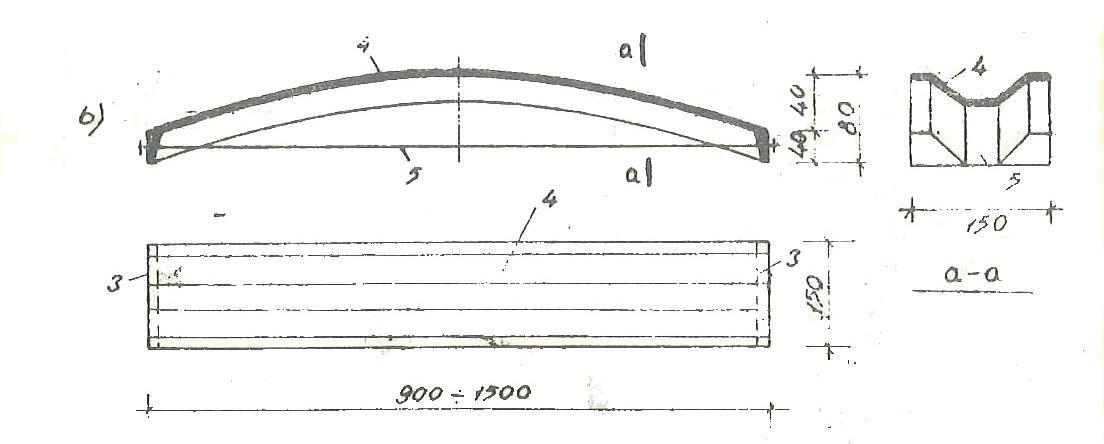

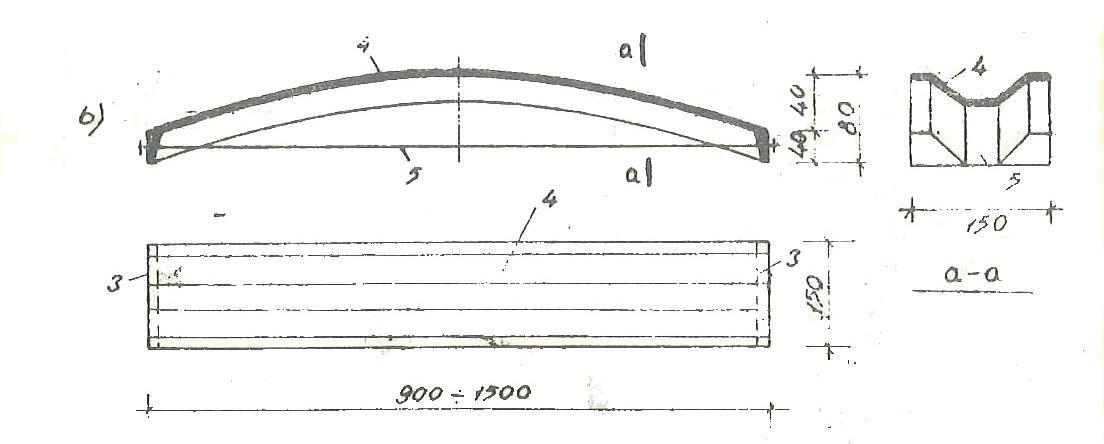

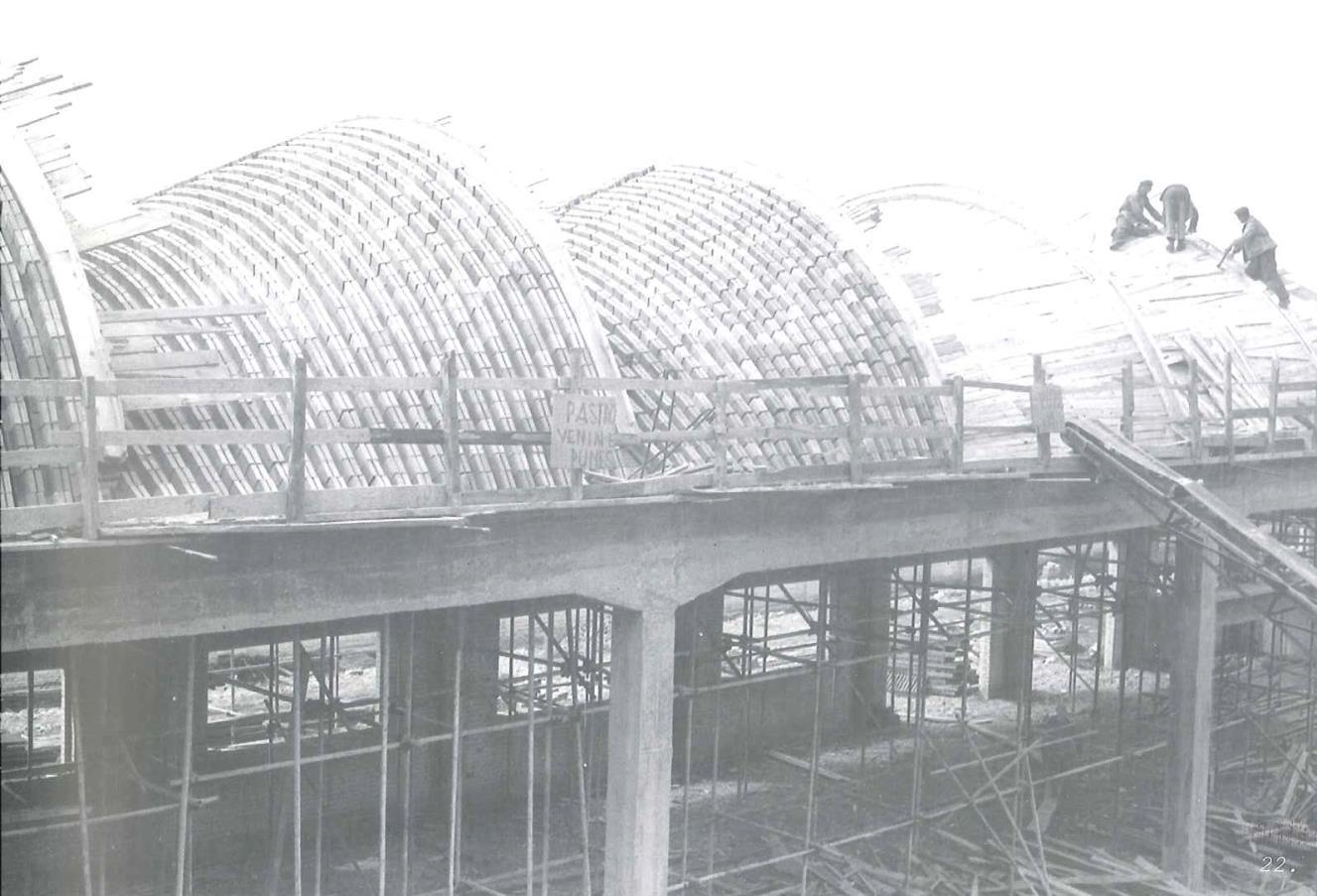

Figure 2.8 Shell panel cover scheme. Source Archive ..........................................................101

Figure 2.9 Wall column connection. Source Archive 101

Figure 2.10 Interior Space of the existing building. ..............................................................102

Figure 2.11 Wall column connection. Source Archive 102

Figure 2.12 Interior space immage before the convertion.....................................................103

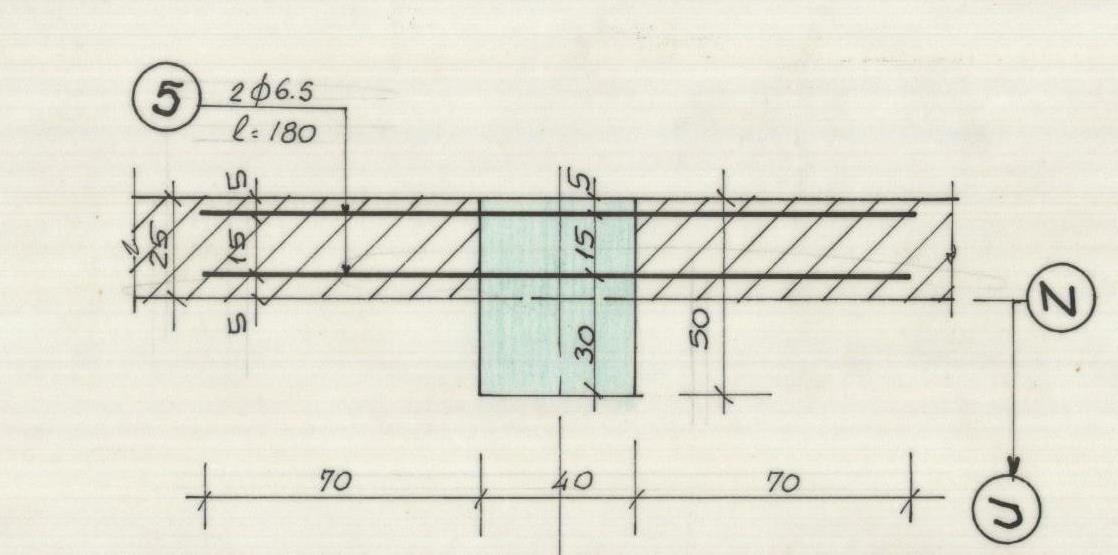

Figure 2.13 Construction detail. Source Archive...................................................................103

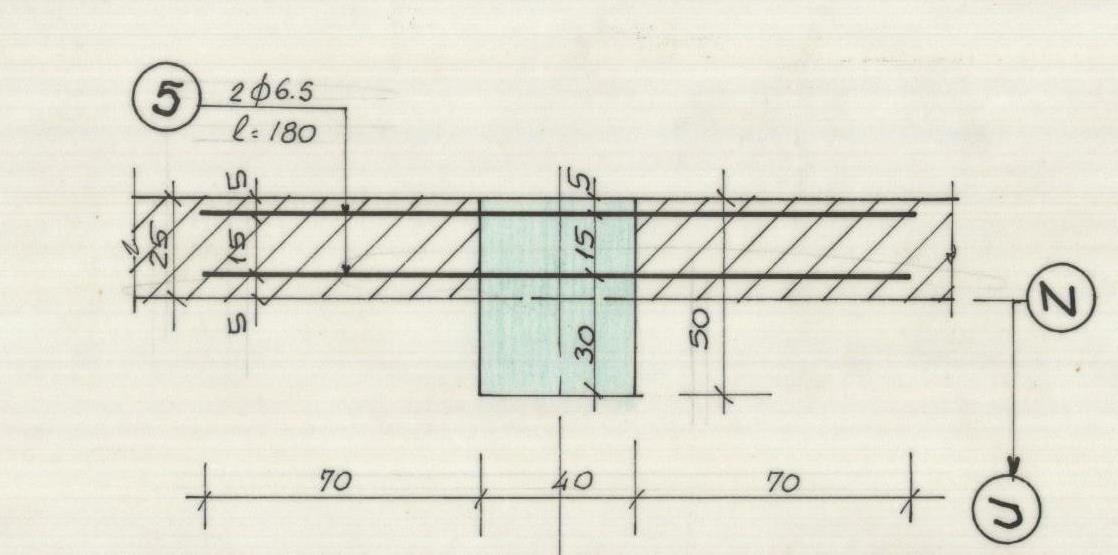

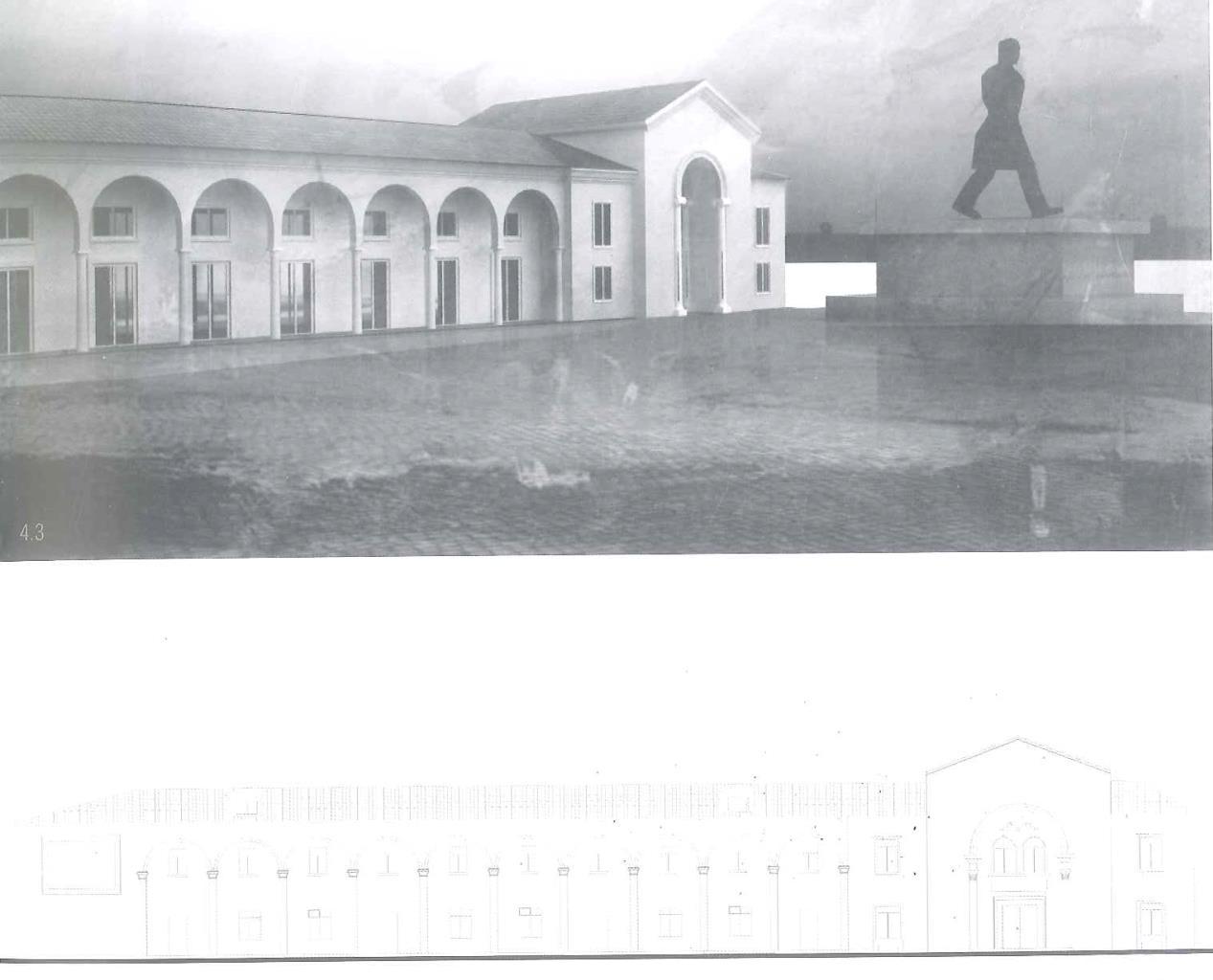

Figure 2.14. New Master plan. Credits Atelir4 104

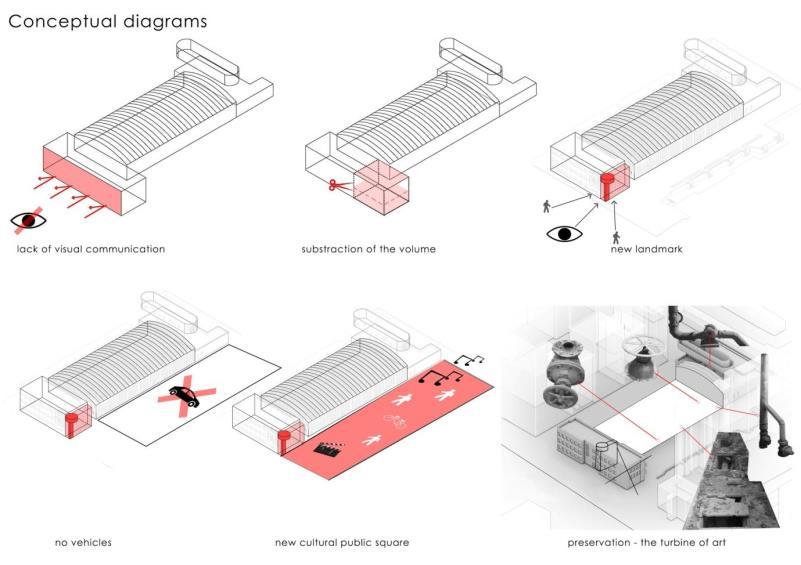

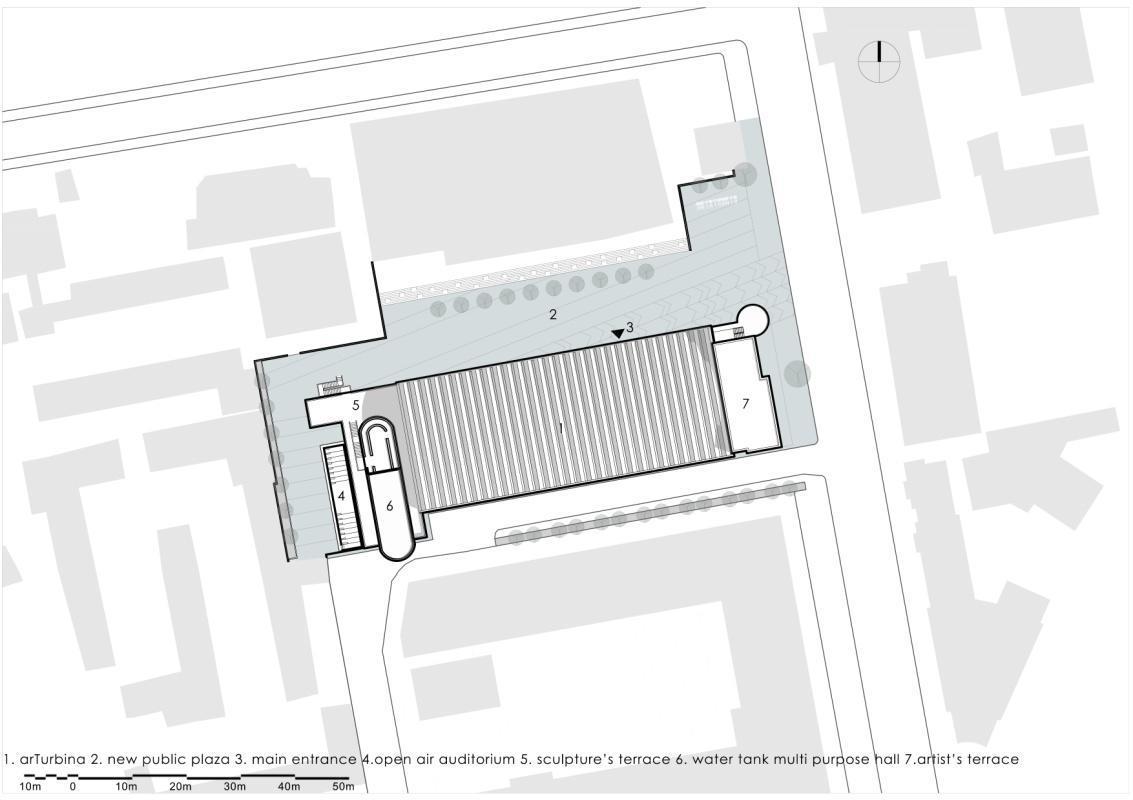

Figure 2.15. Transformation Diagram. Source Atelier4........................................................105

Figure 2.16 Render Image of the transformation. Credits Atelier4 105

Figure 2.17. Image after the transformation. Credits Author ................................................106

Figure 2.18. Image showing the preservation of the original roof cover. Credits Author 107

Figure 2.19 Image showing the preservation of the original elements of the windows. Credits

Author....................................................................................................................................107

Figure 2.20. Image showing the interior of the main internal space. Credits Atelier4 108

Figure 2.21. Facade treatment of the windows......................................................................109

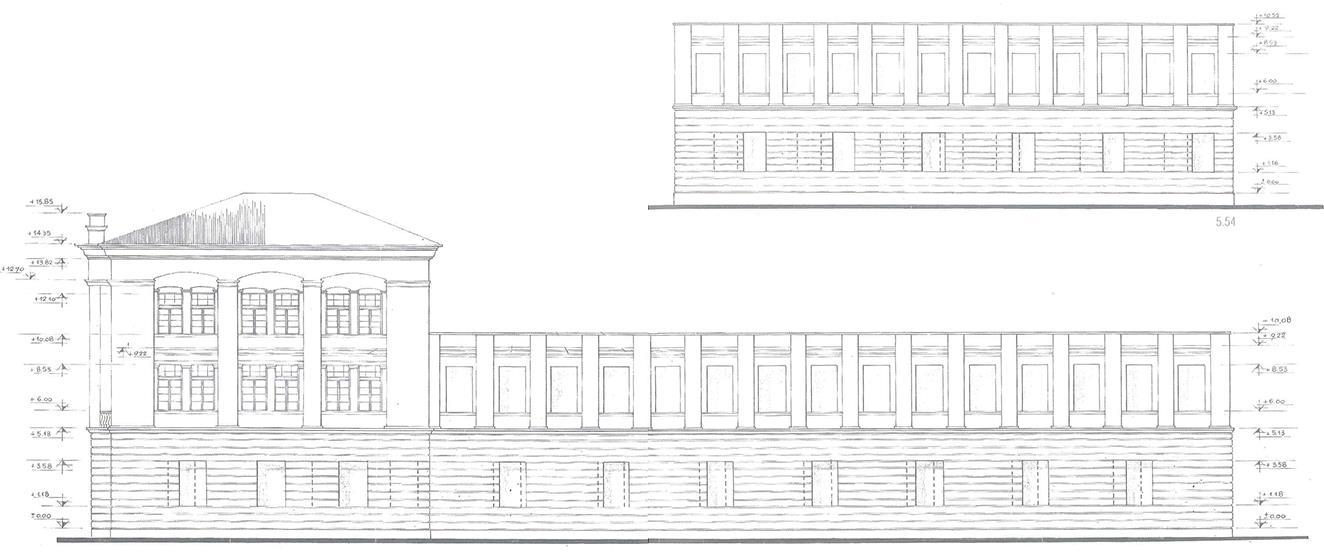

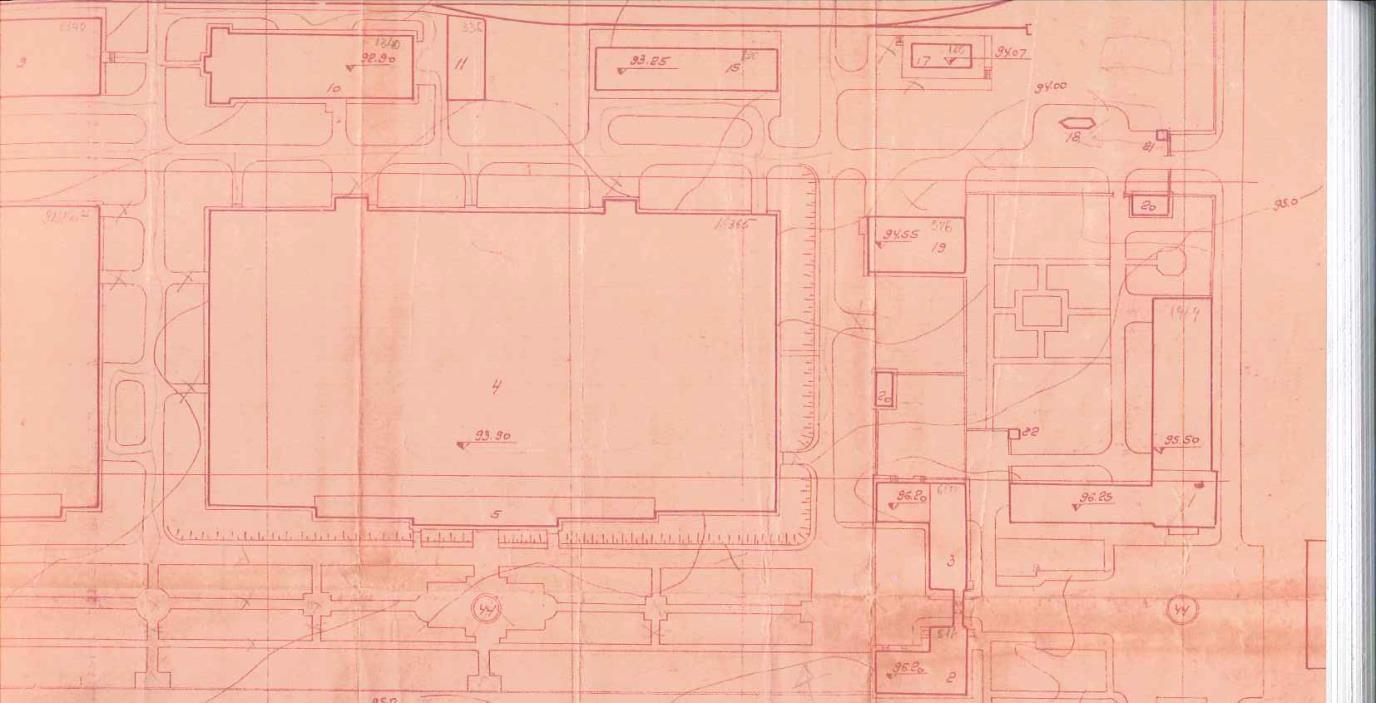

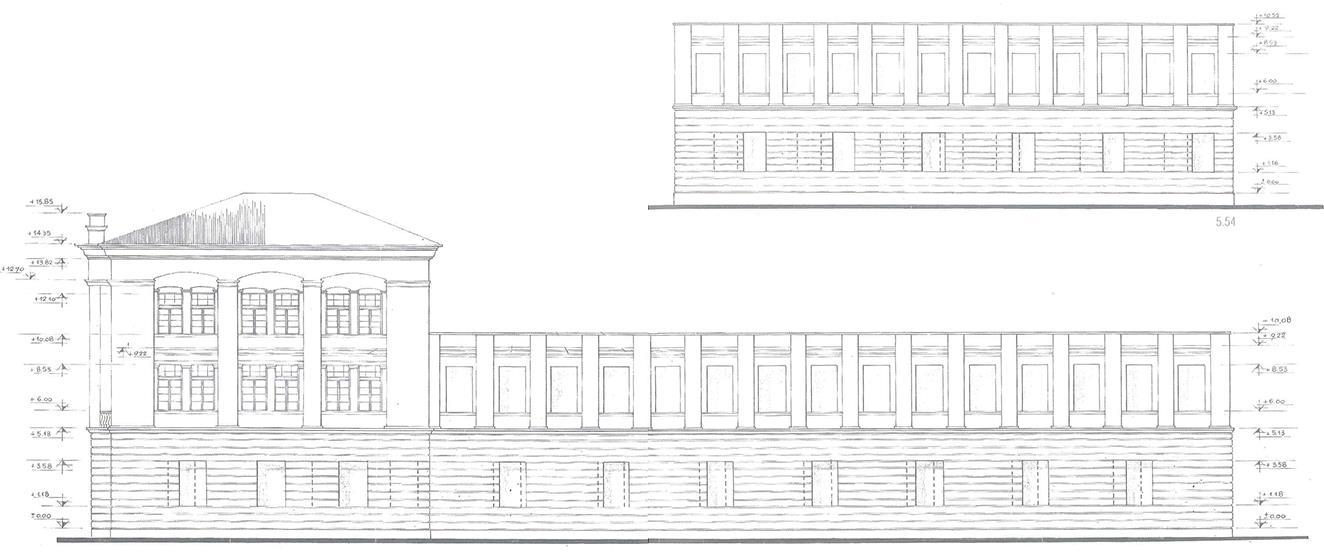

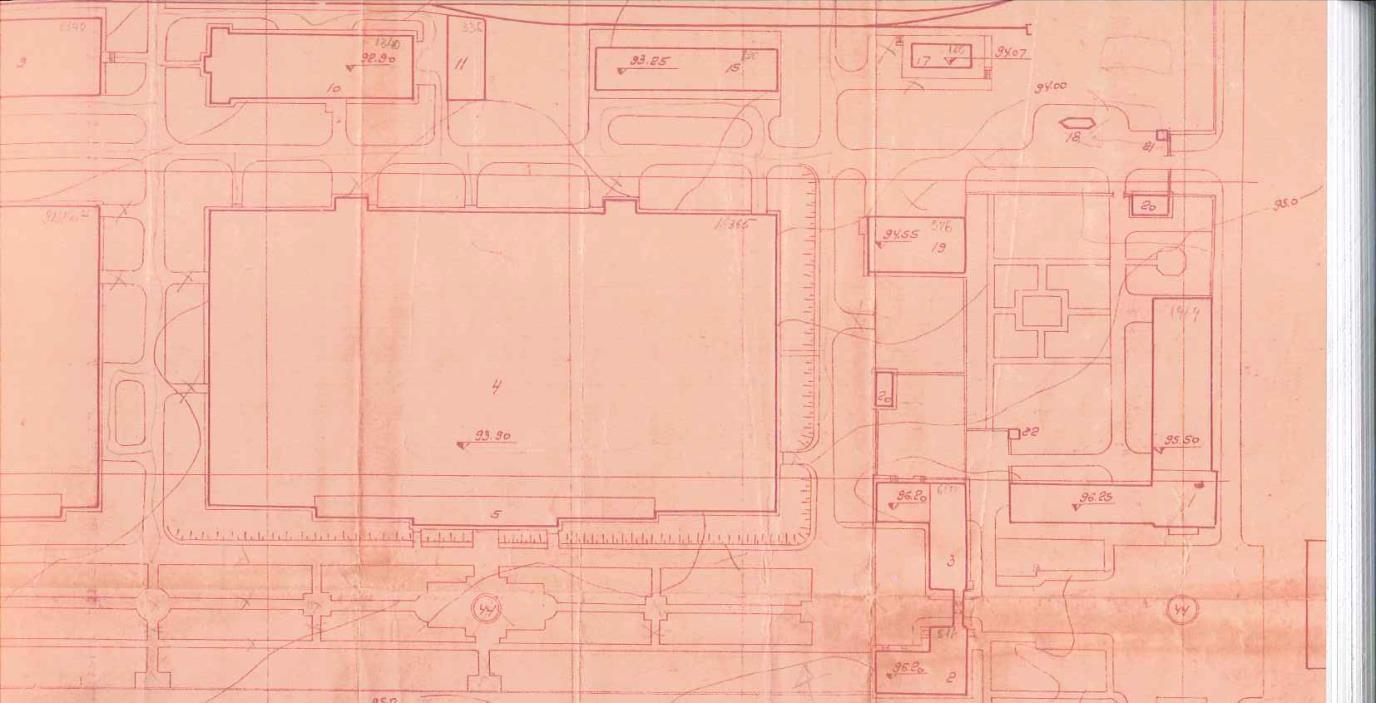

Figure 2.22 Plan fragment. Source Archive 111

Figure 2.23 Urban contest comparison. Source Asig Geoportal Albania..............................112

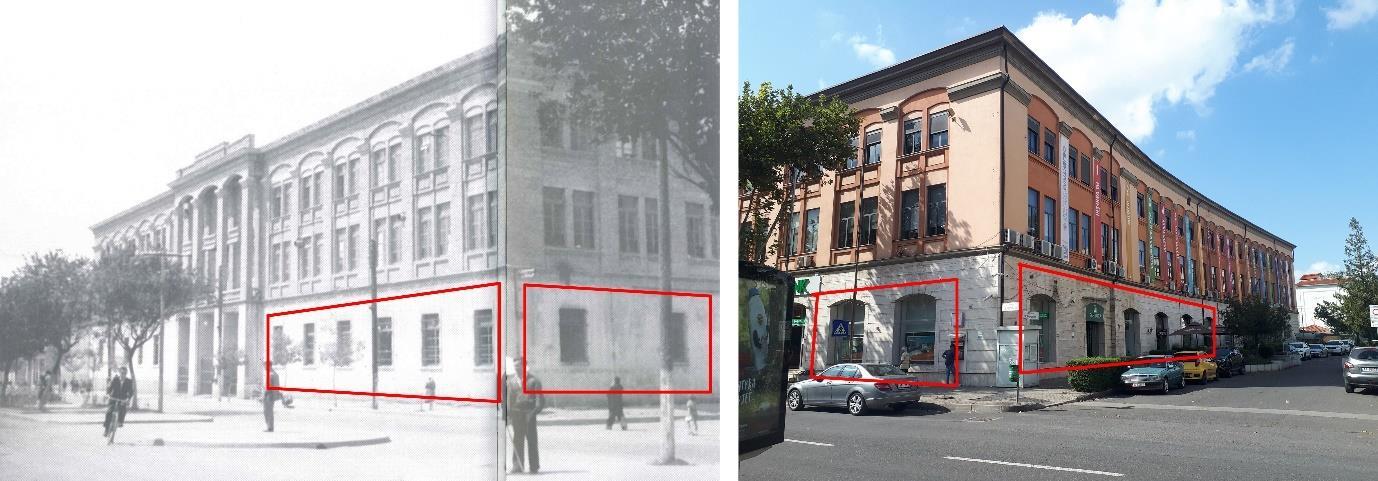

Figure 2.24 Original Façade. Source Archive .......................................................................113

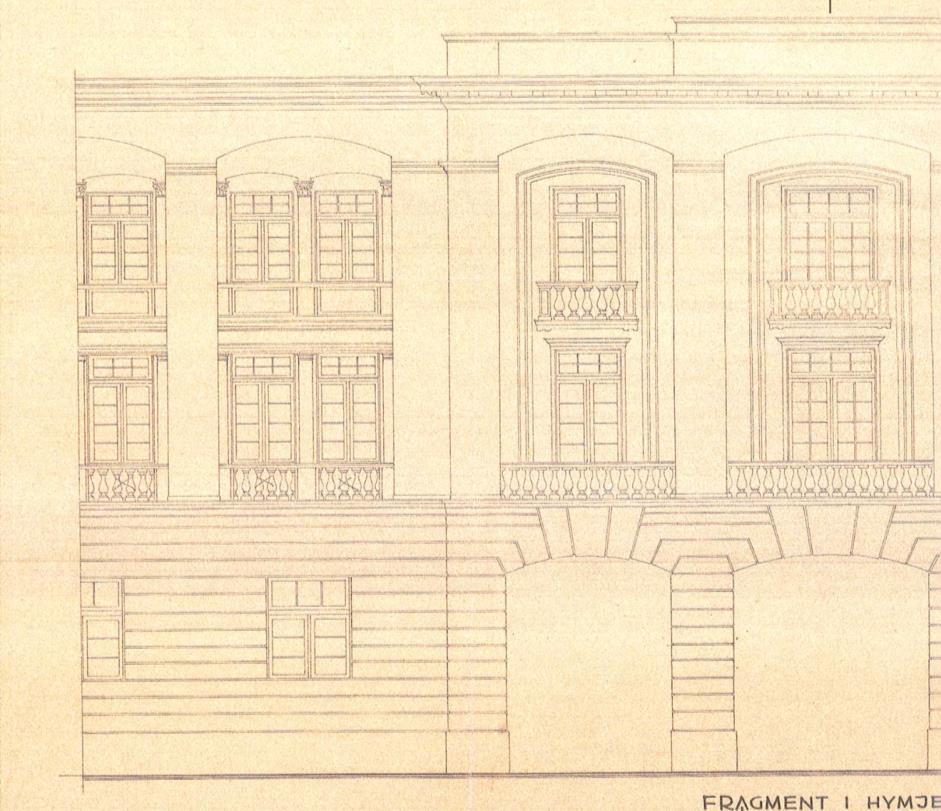

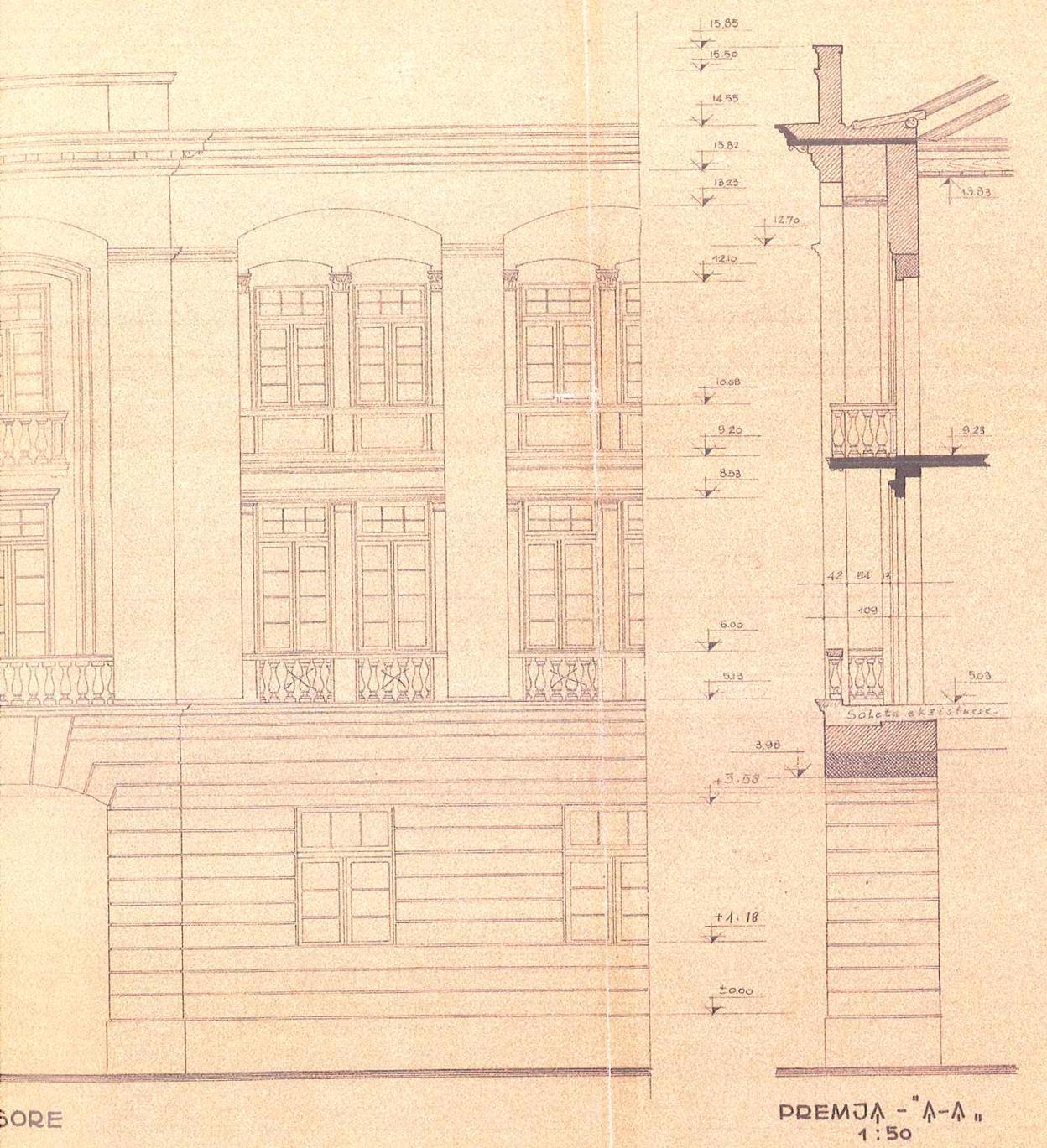

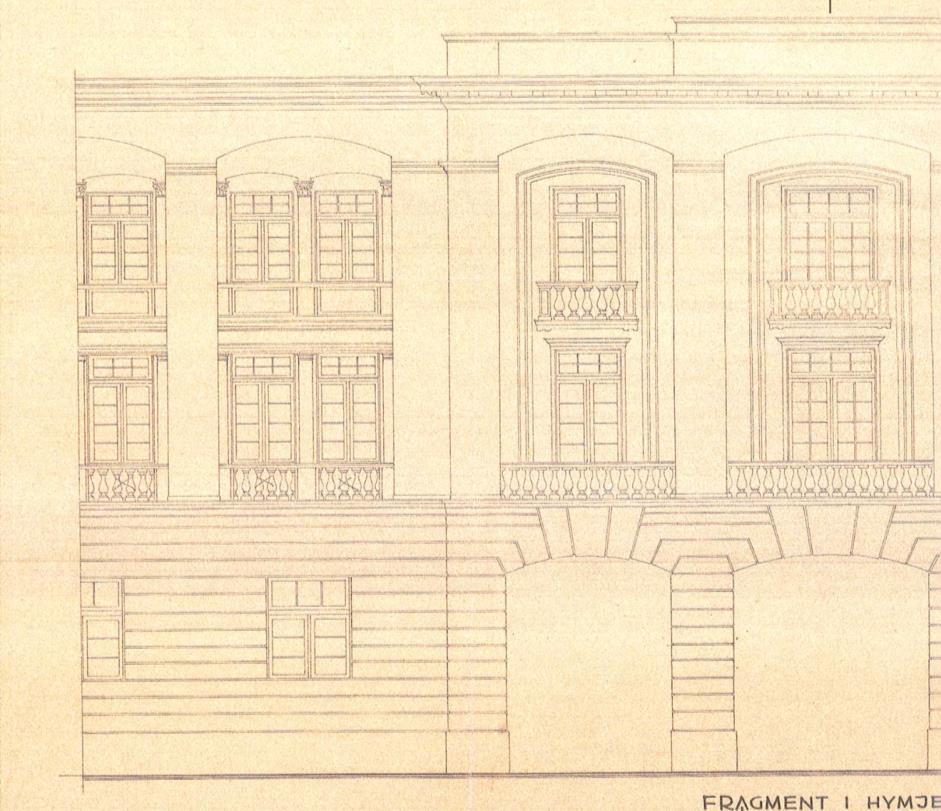

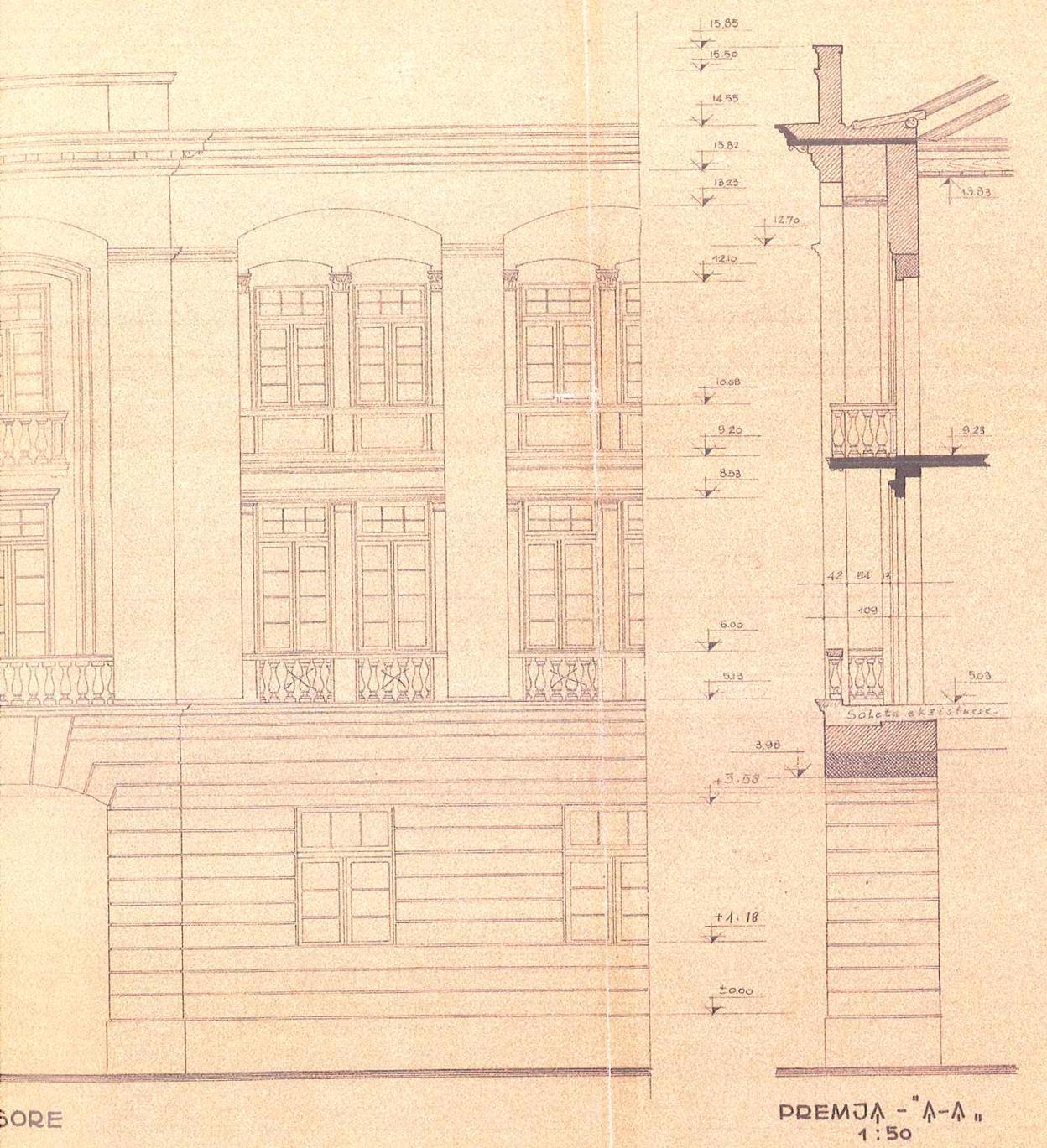

Figure 2.25 Principal façade fragment. Original project. Source Archive 114

Figure 2.26 Principal façade fragment. Section of the building. Source Archive.................115

6

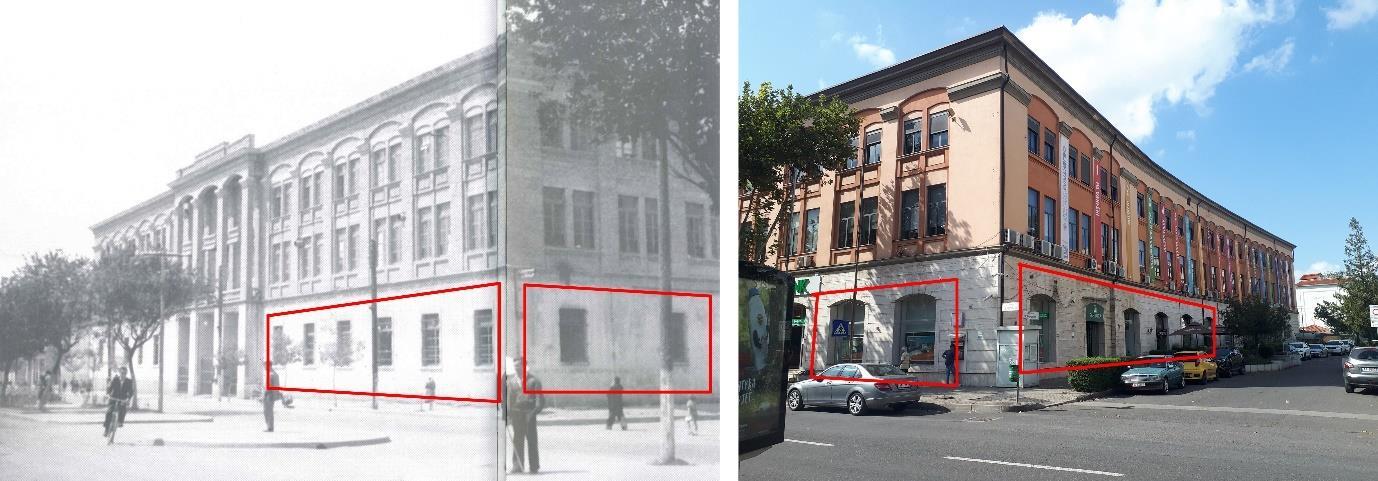

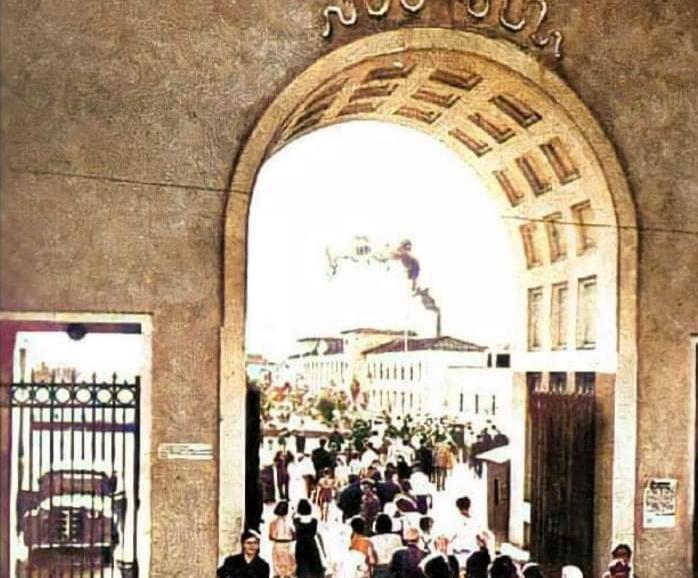

Figure 2.27 Image of the building and social activities. Source Archive 116

Figure 2.28 Comparative image Before After of the building. Source Archive Author.......117

Figure 2.29. Commercial activities hosted by the building. Source Author..........................117

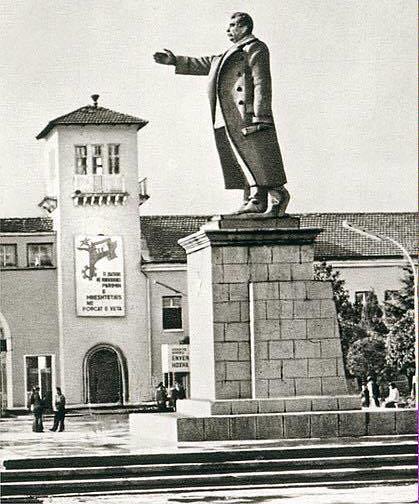

Figure 2.30. Urban contest comparison 1994 2018. Source Asig Geoportal. 121

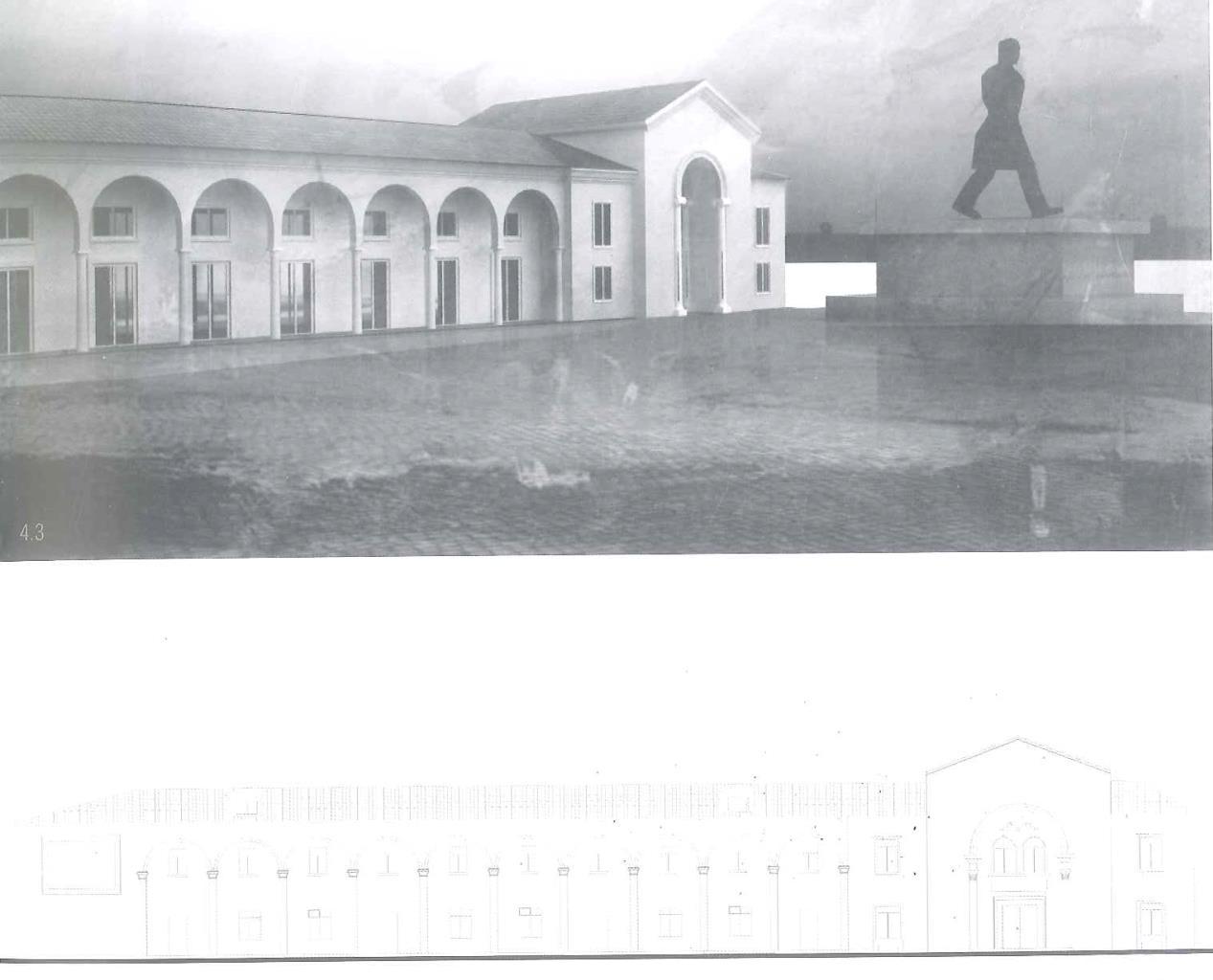

Figure 2.31. Original Facade. Source Archive .....................................................................122

Figure 2.32. Immage of postcard rapresenting the factory 123

Figure 2.33. On going work ofe the former ofice building of the factory.............................124

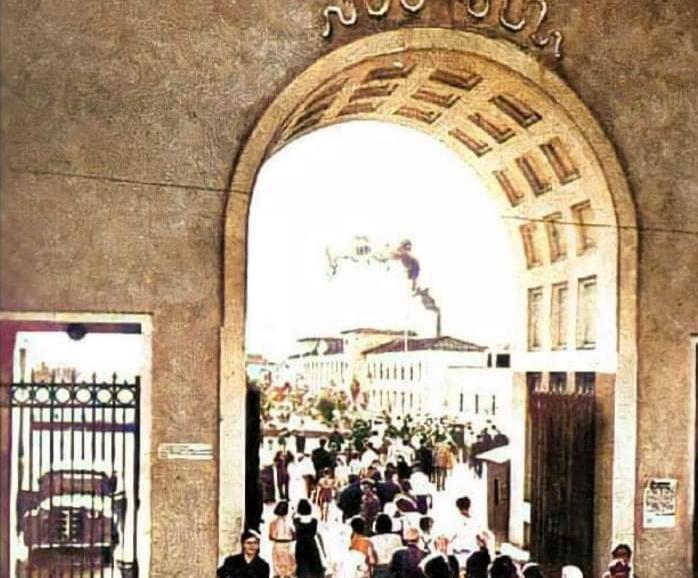

Figure 2.34. Workers entering the Factory. Source Archive.................................................124

Figure 2.35. Former ofice buiding from the square 125

Figure 2.36. Adjacent Square of the building. Source Author...............................................126

Figure 2.37. Back space of the building. Source Author 126

Figure 2.38. Geographic position of the building. Credits Author........................................129

Figure 2.39. Urban situation of the site. Source Author........................................................130

Figure 2.40. Access Analysis in the site. Credits Author 130

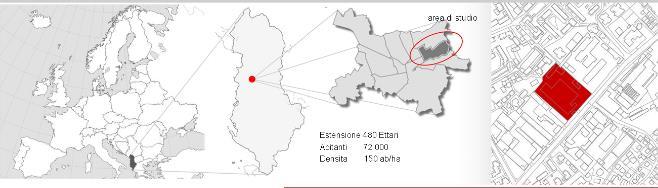

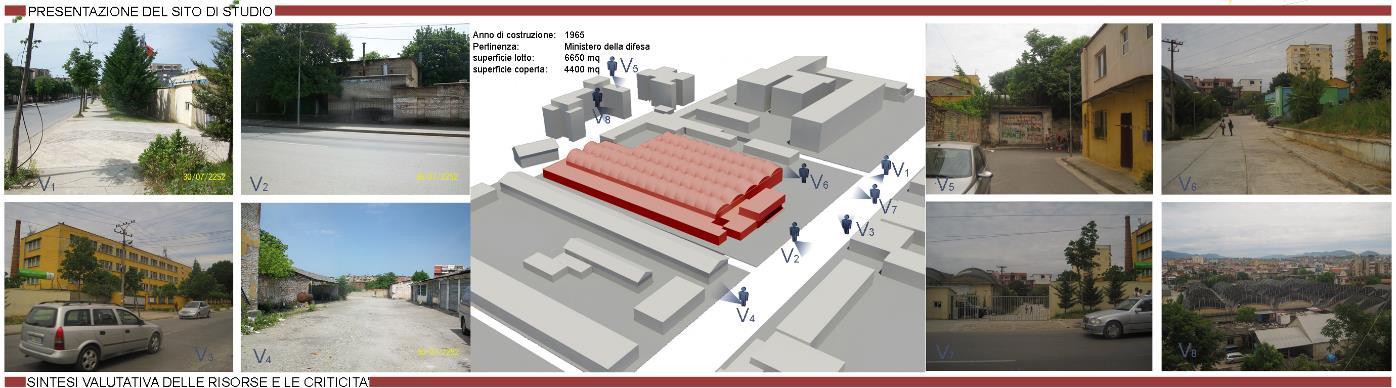

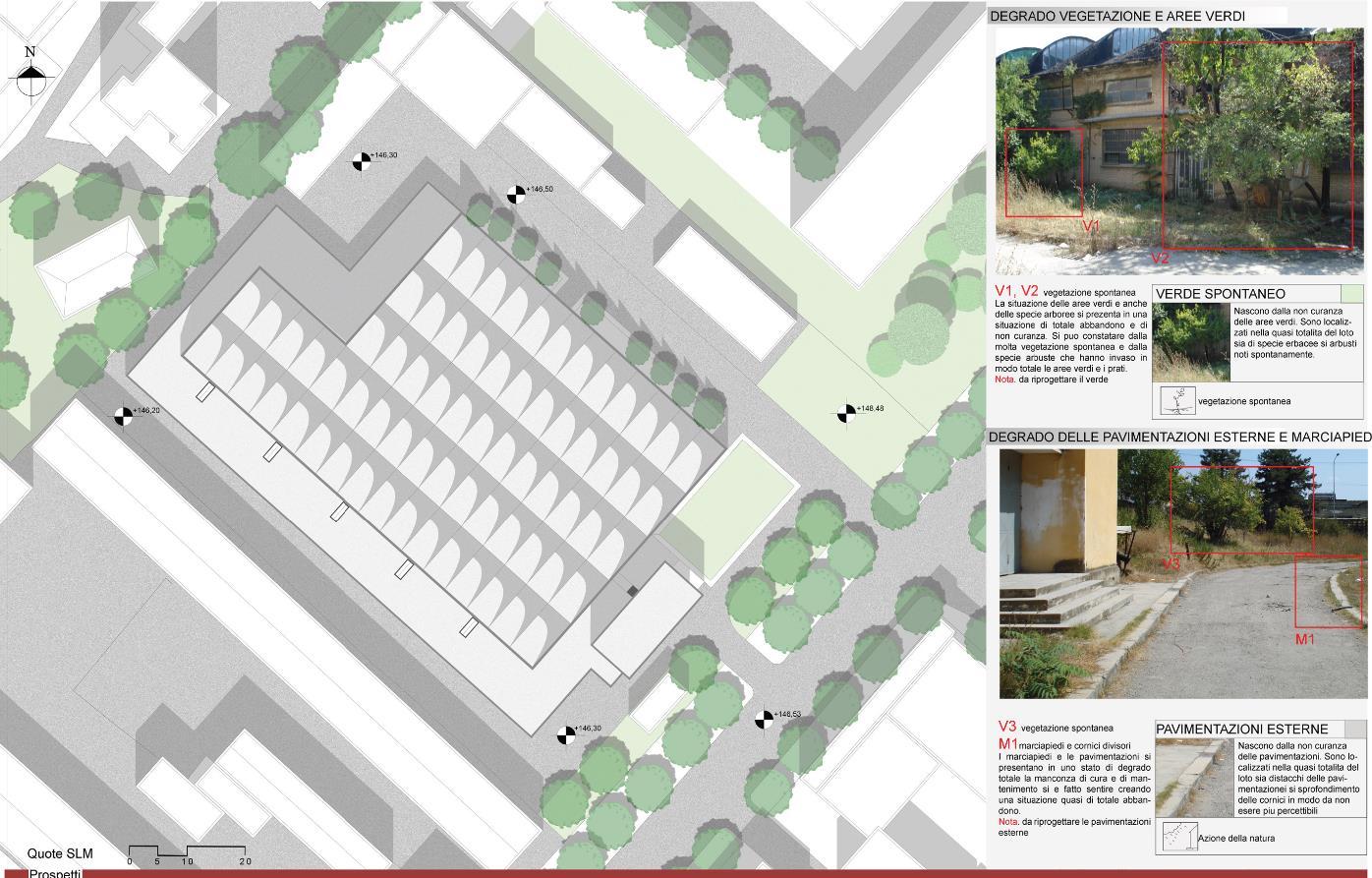

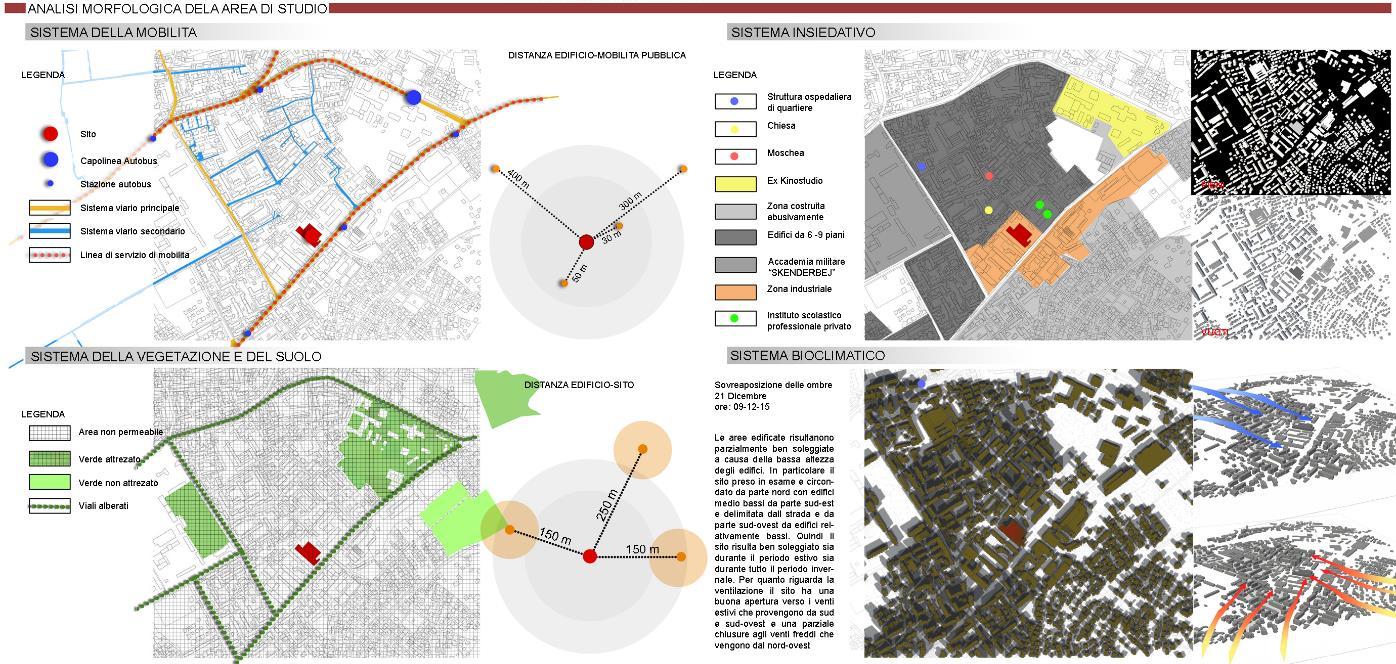

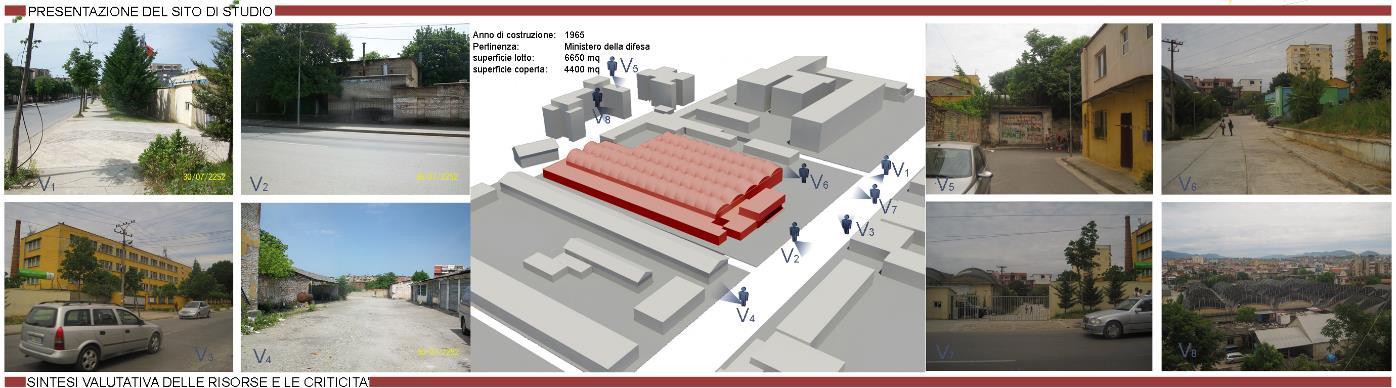

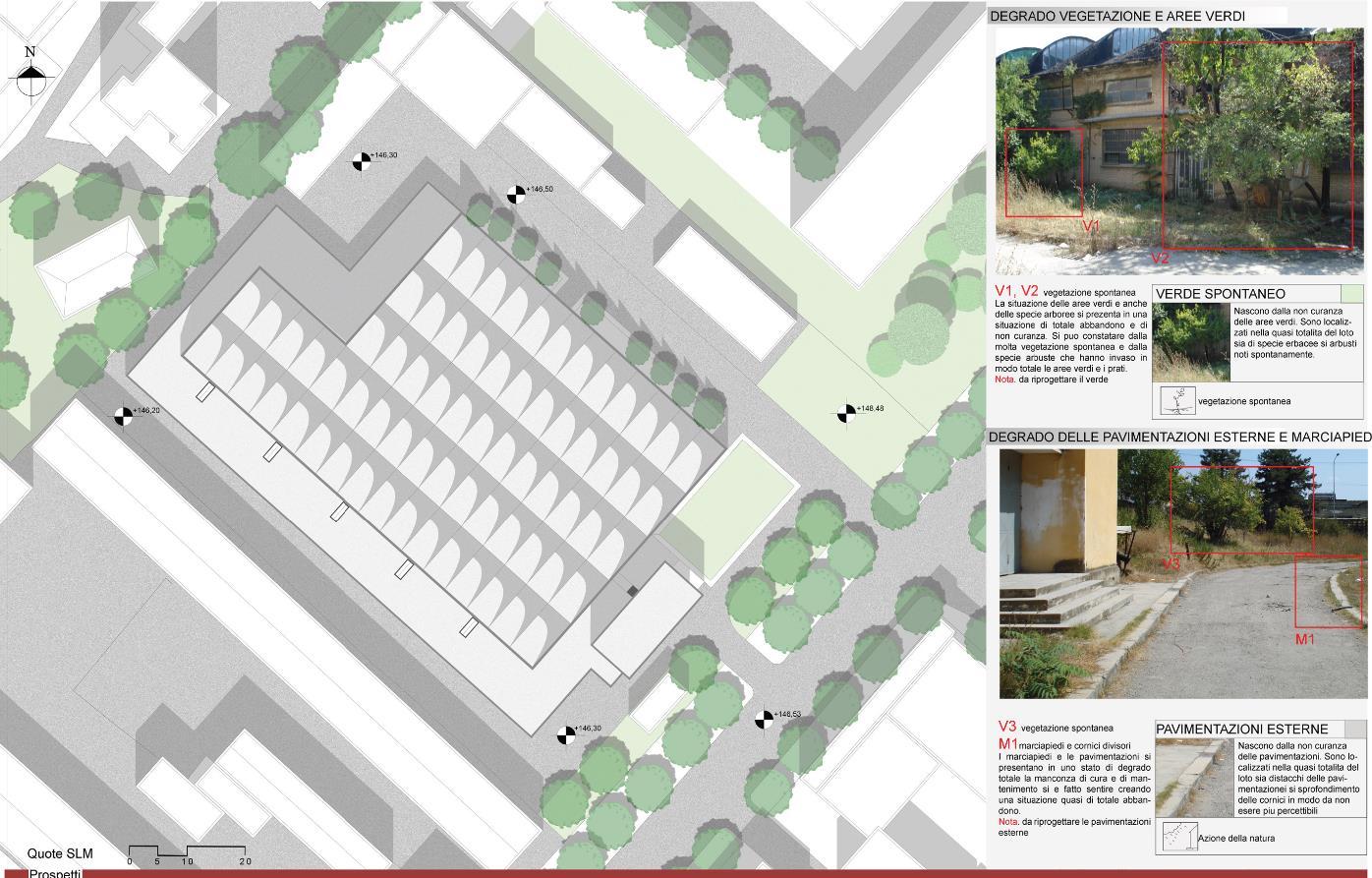

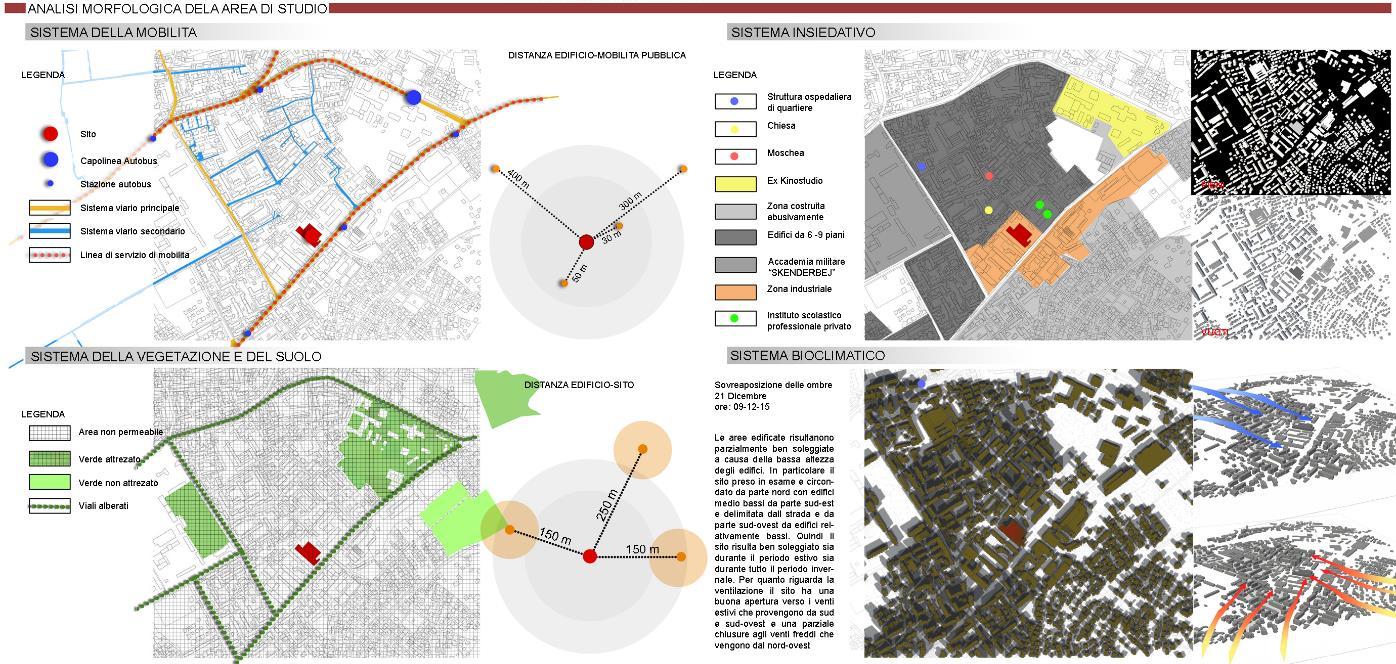

Figure 2.41 Morphological analysis of the area. Credits Author...........................................131

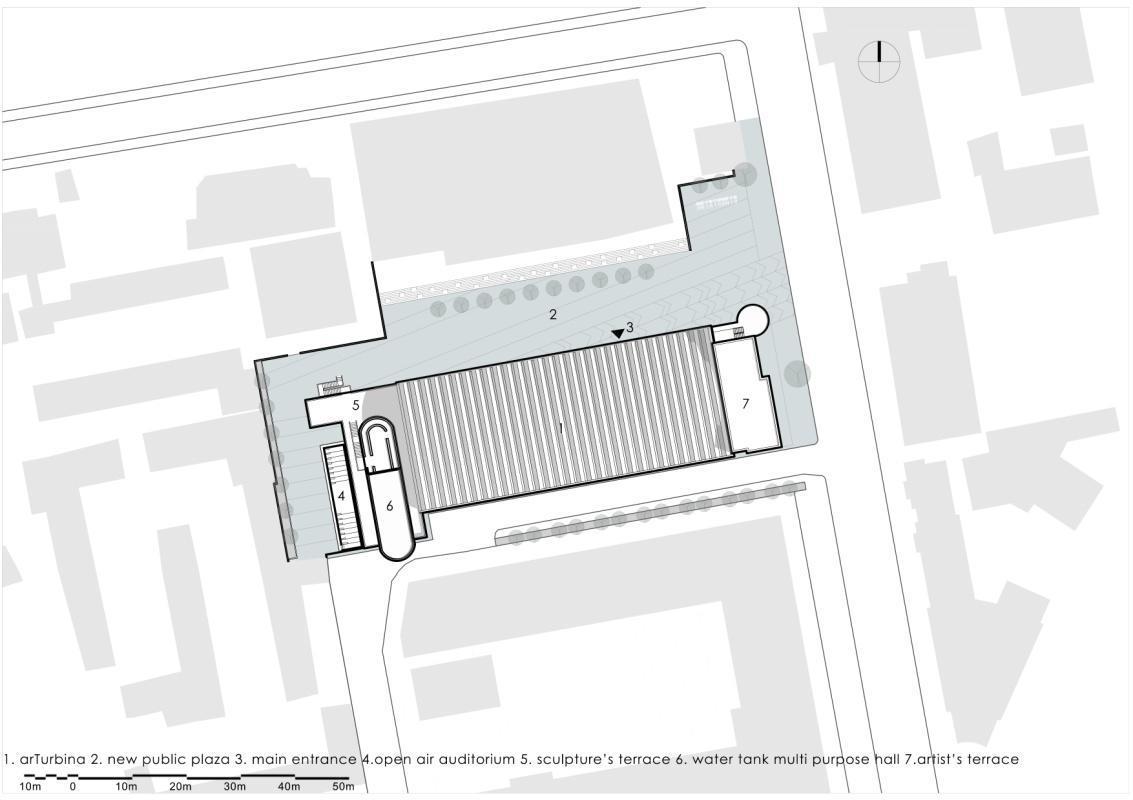

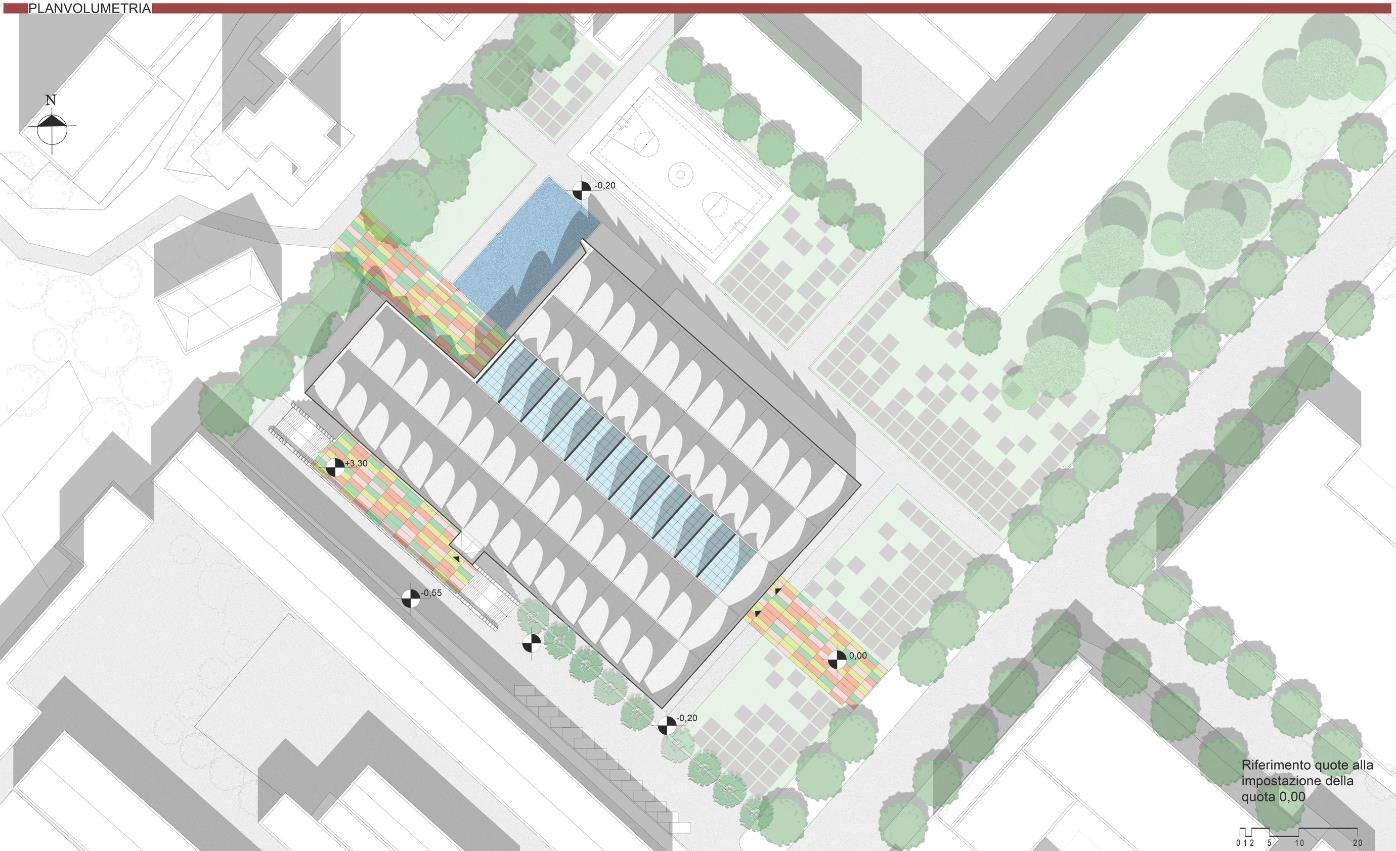

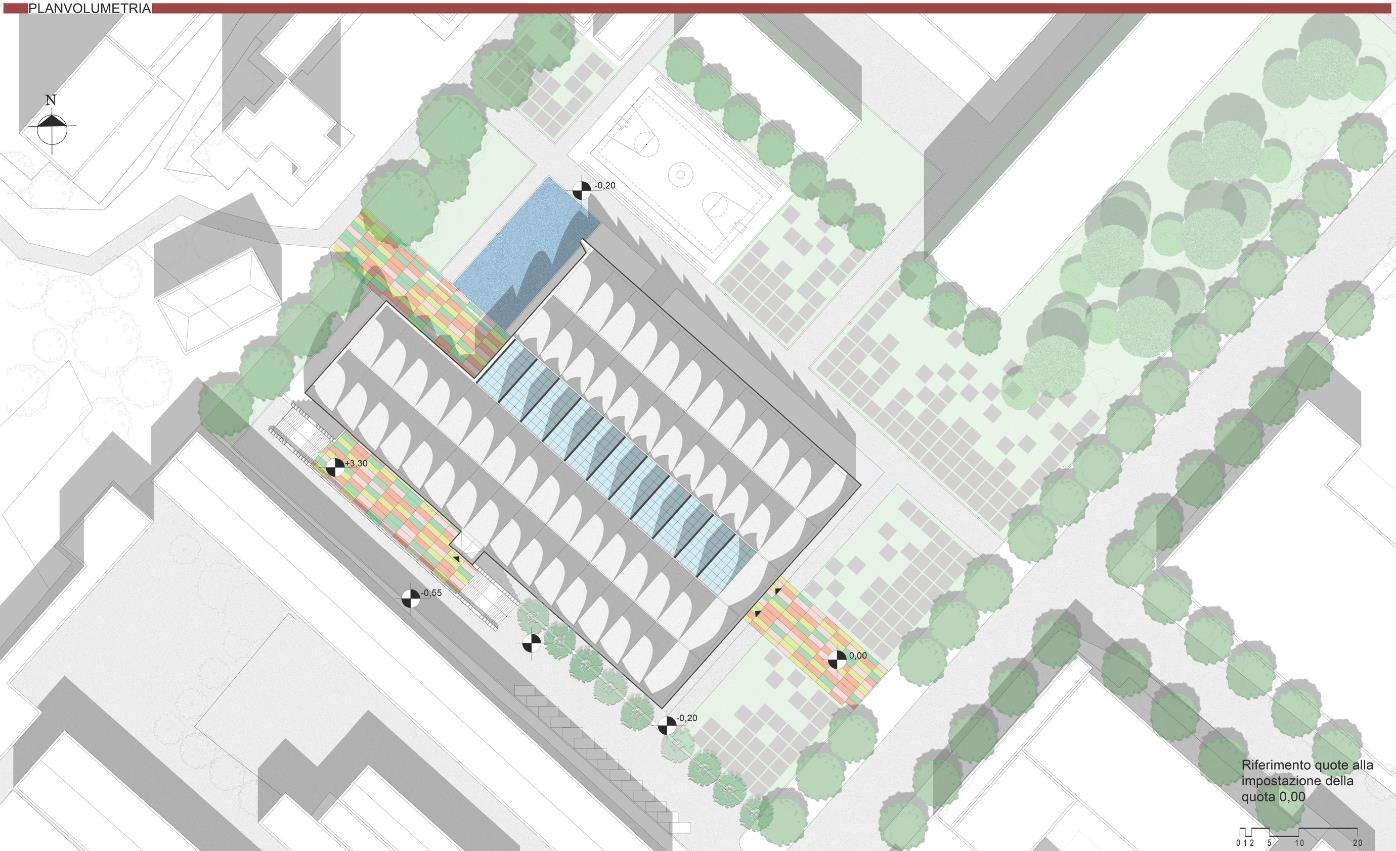

Figure 2.42. Site Plan Intervention. Credits Author 131

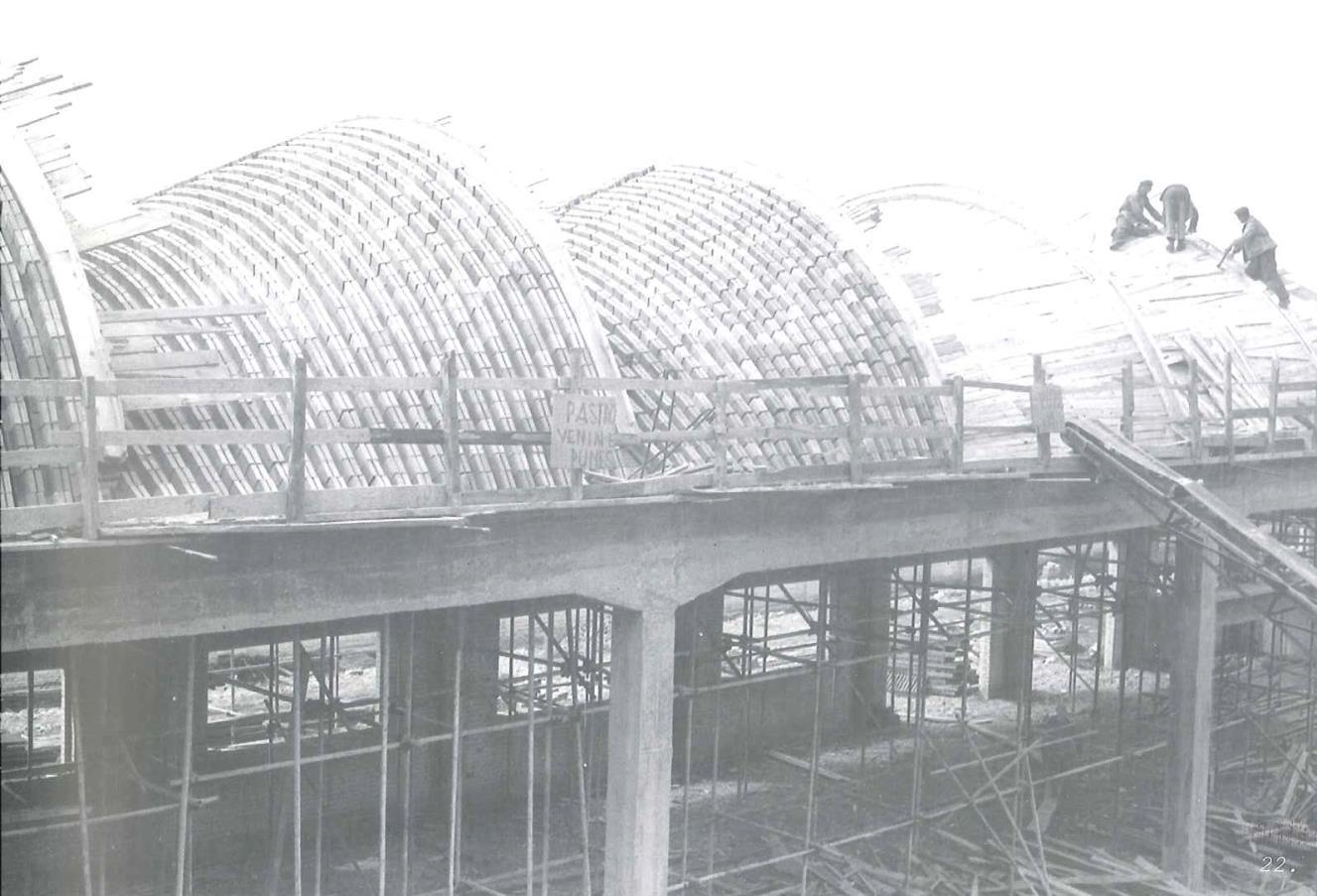

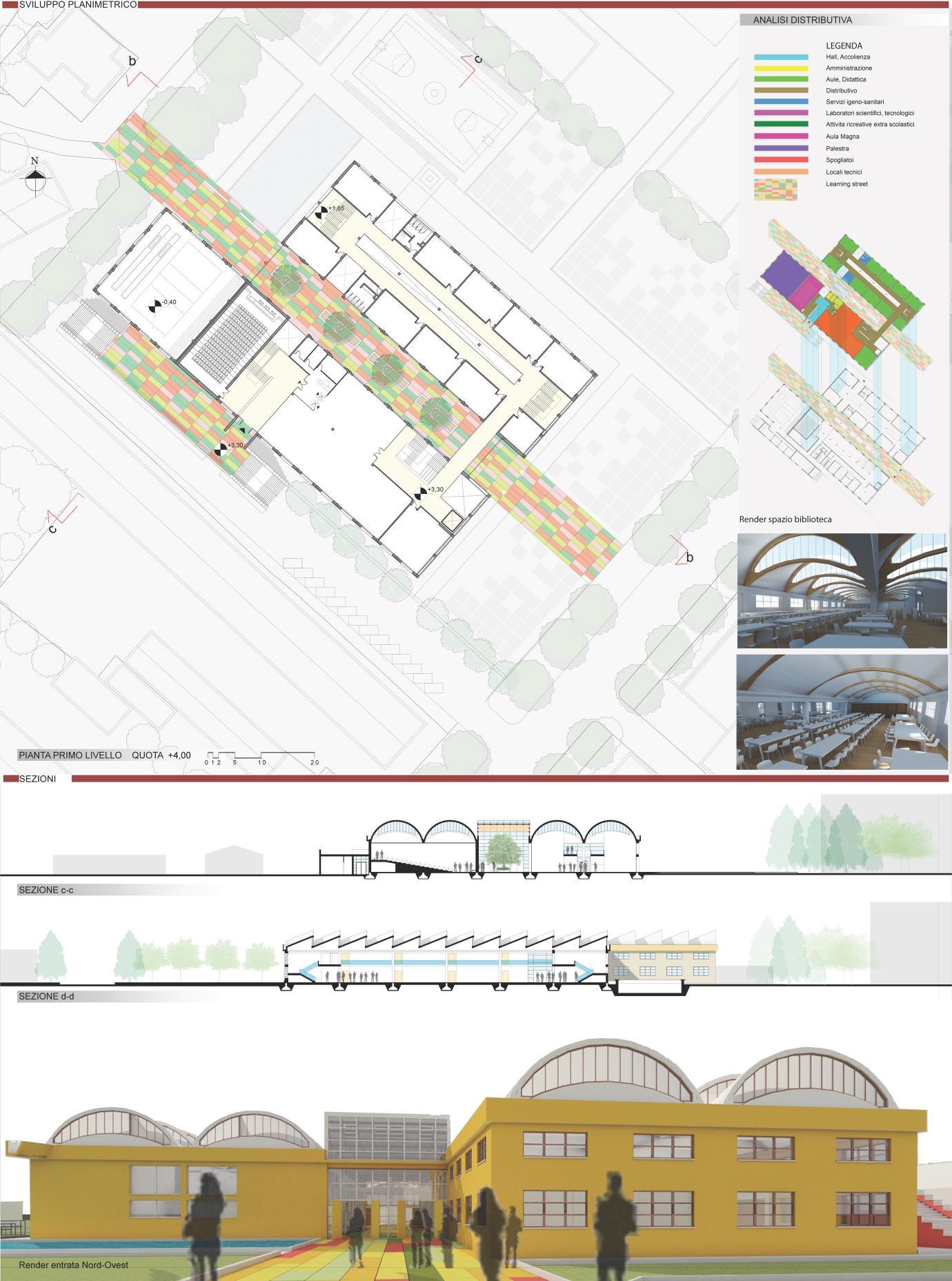

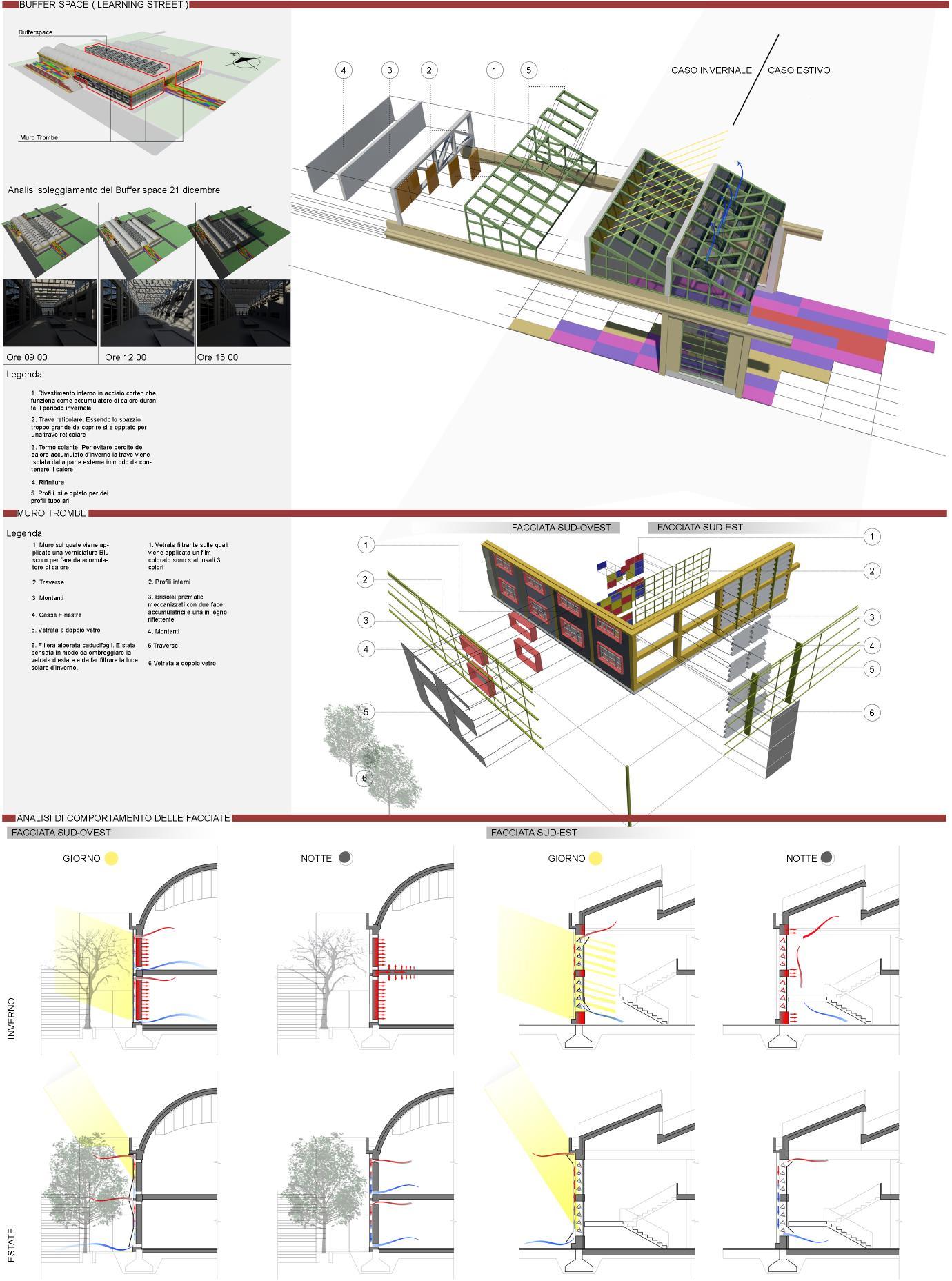

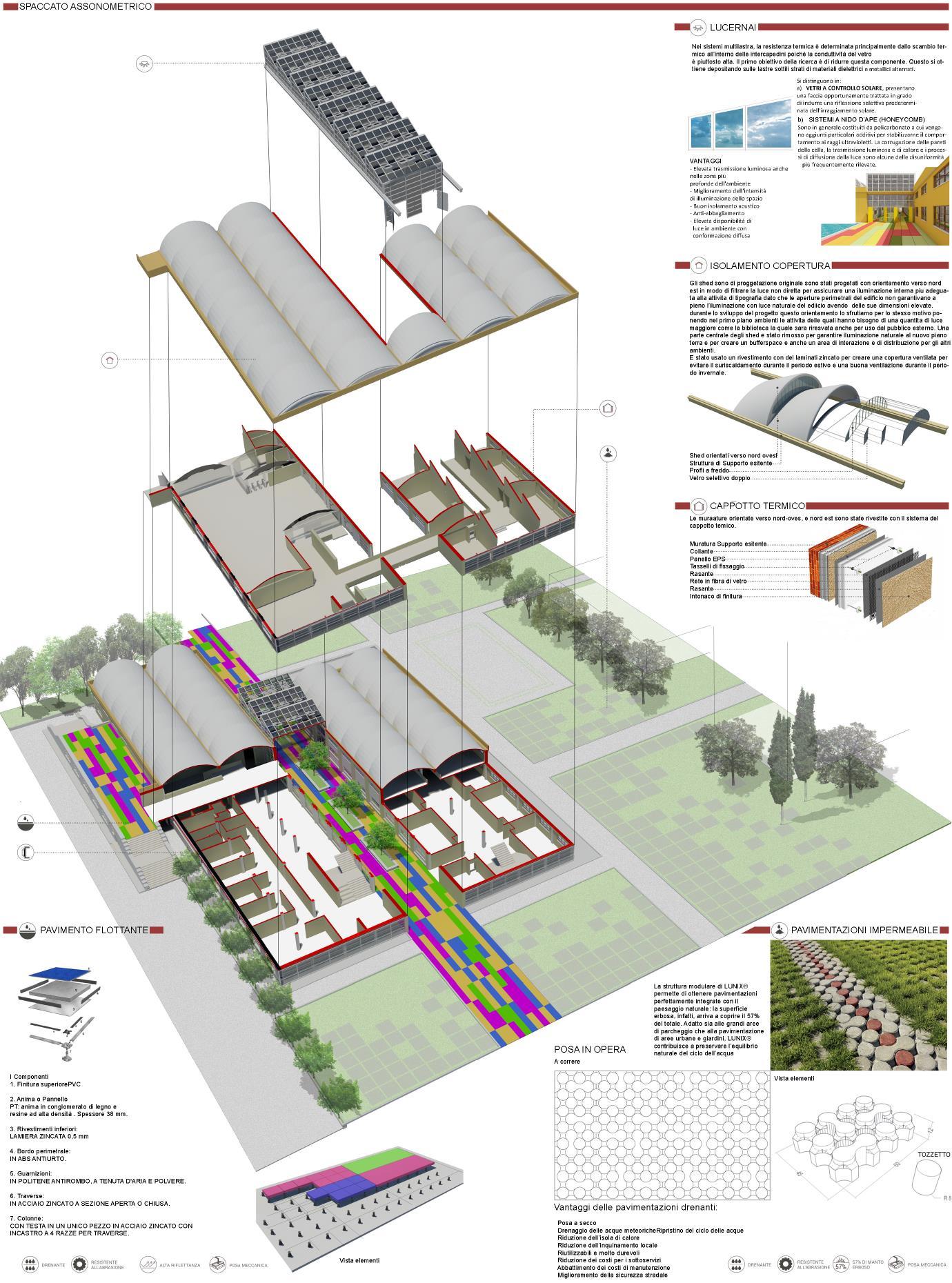

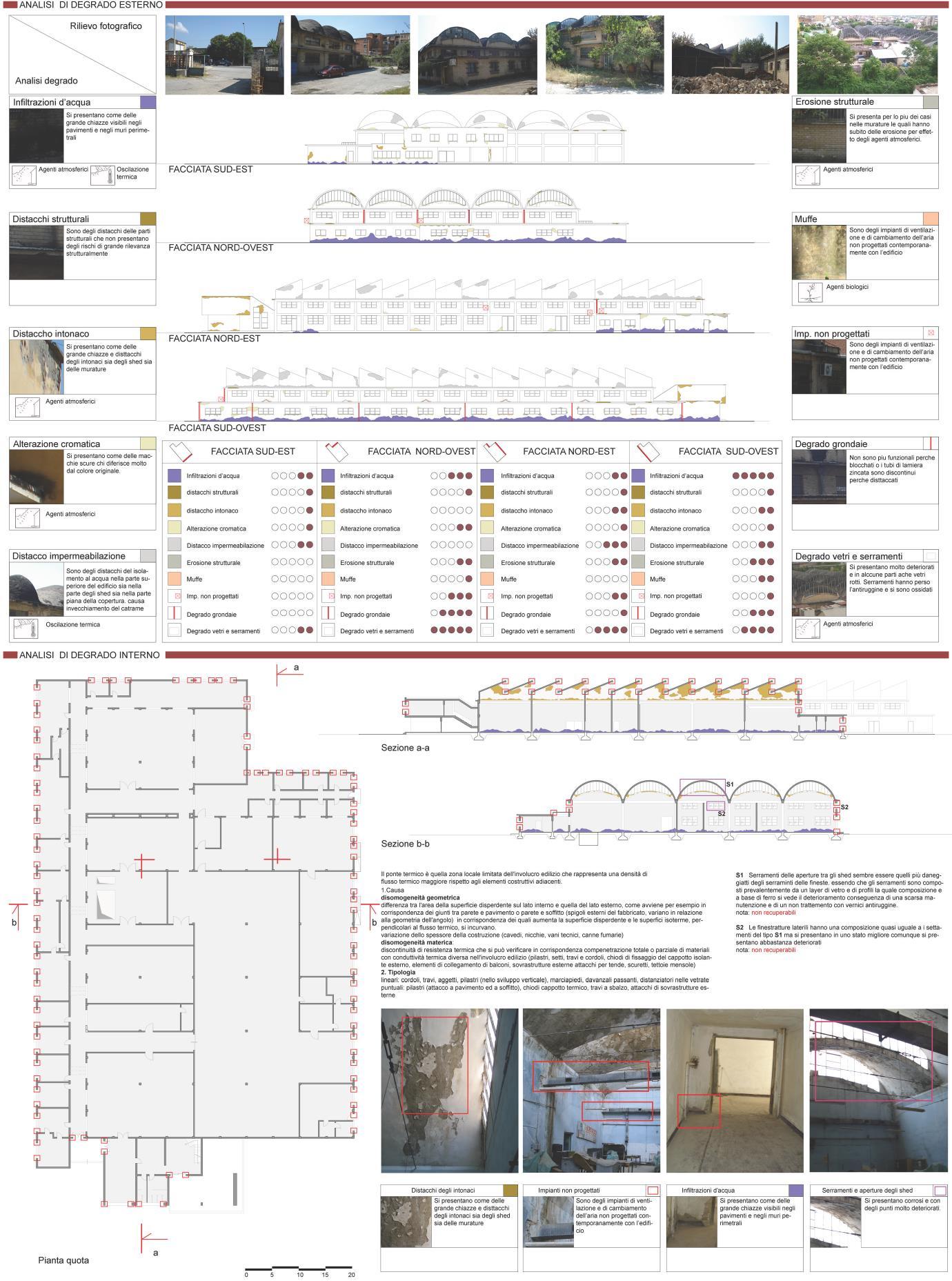

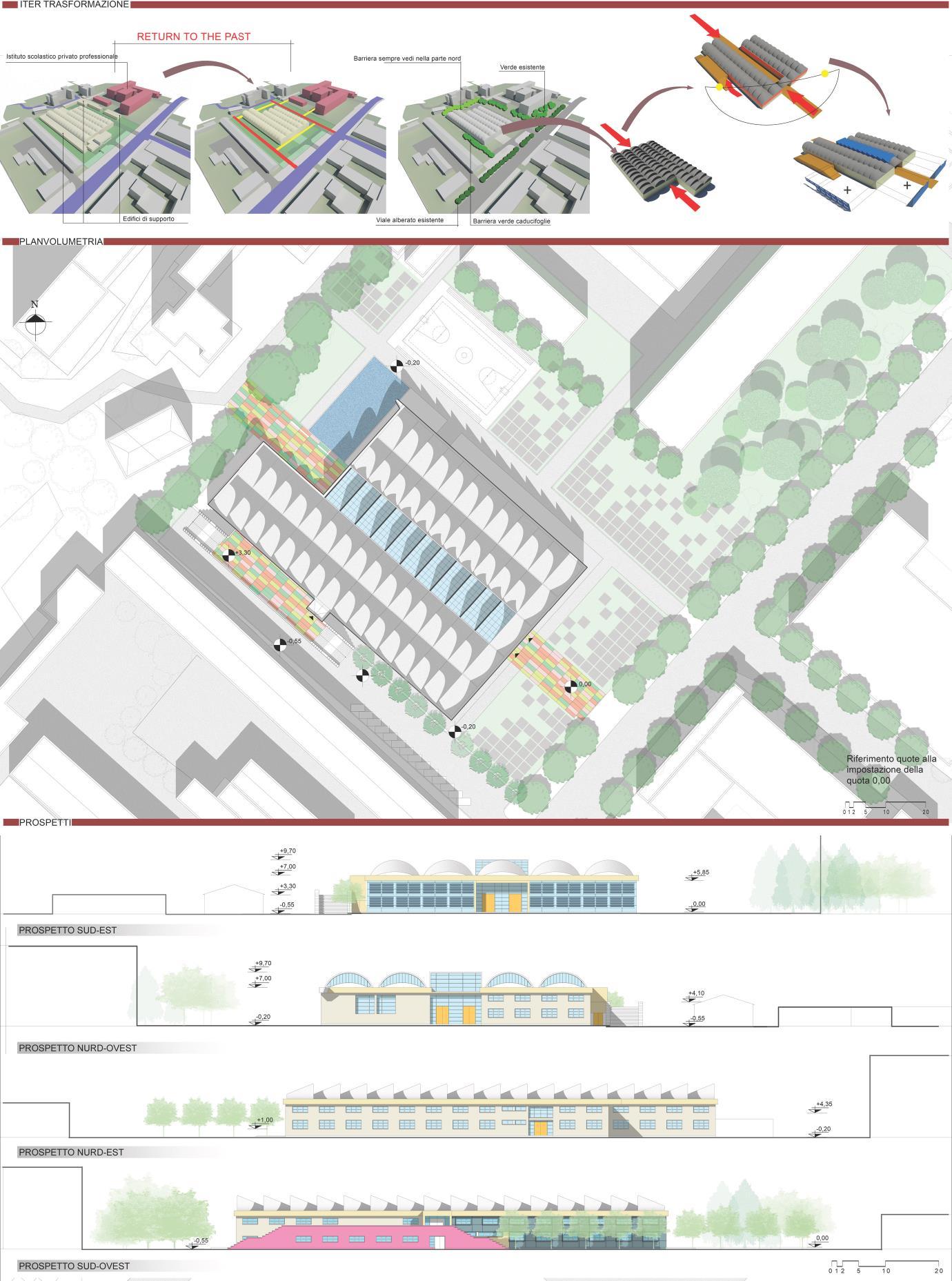

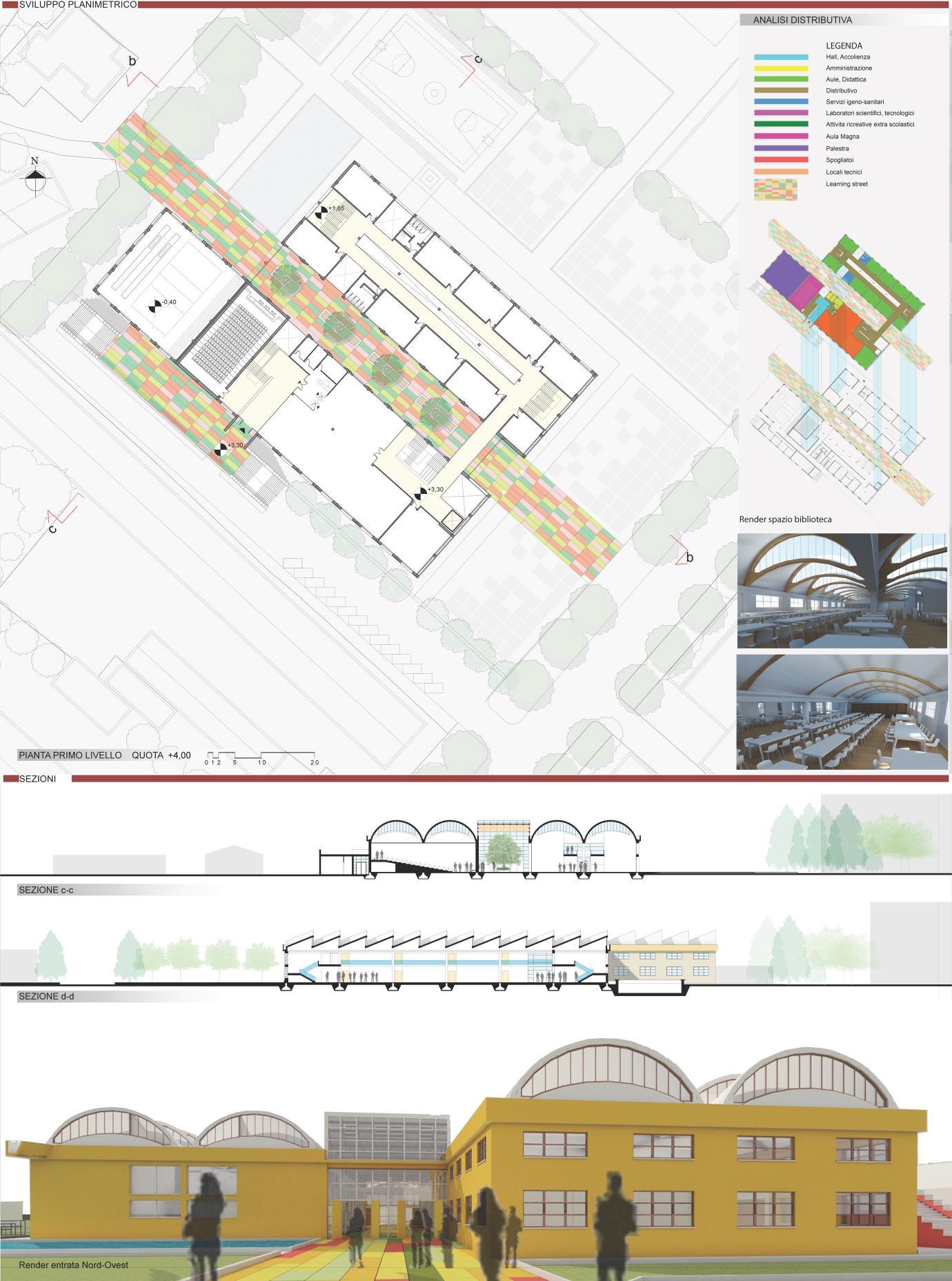

Figure 2.43 The shed construction. Source Archive..............................................................132

Figure 2.44. Building facades after the intervention 133

Figure 2.45 Historic development of the ensemble. Source Author......................................133

Figure 2.46. Facades after riqualificatin. Source Author.......................................................134

Figure 2.47 Representation render. Credits Author 134

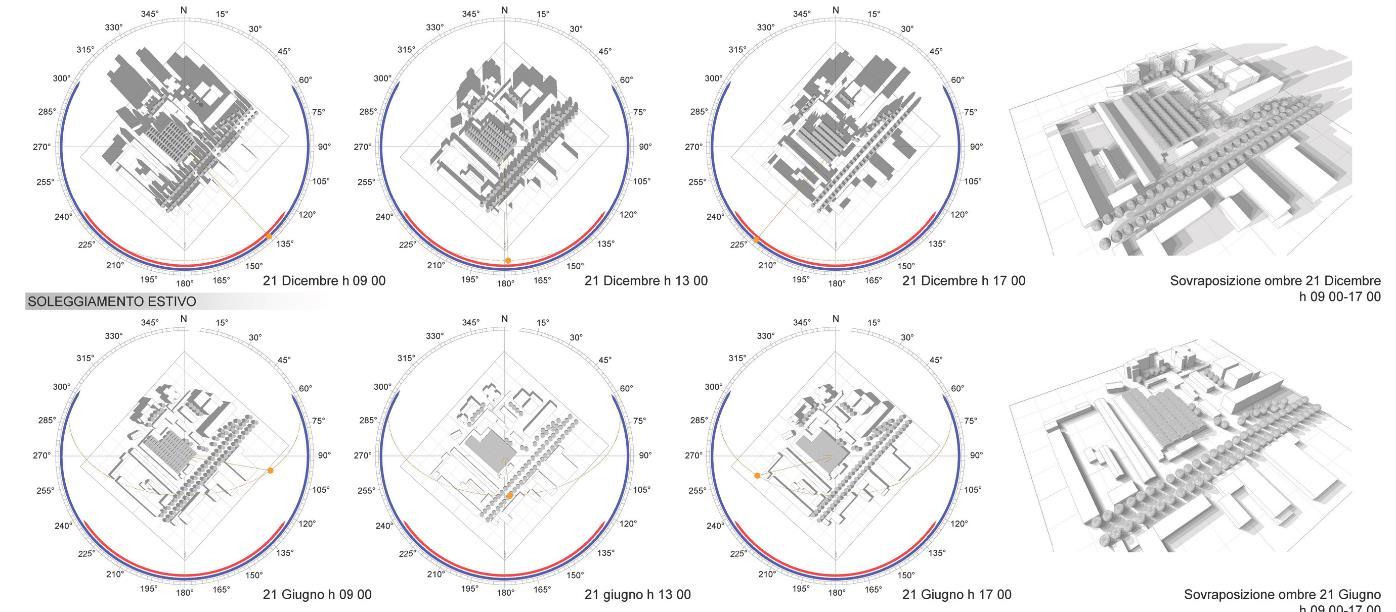

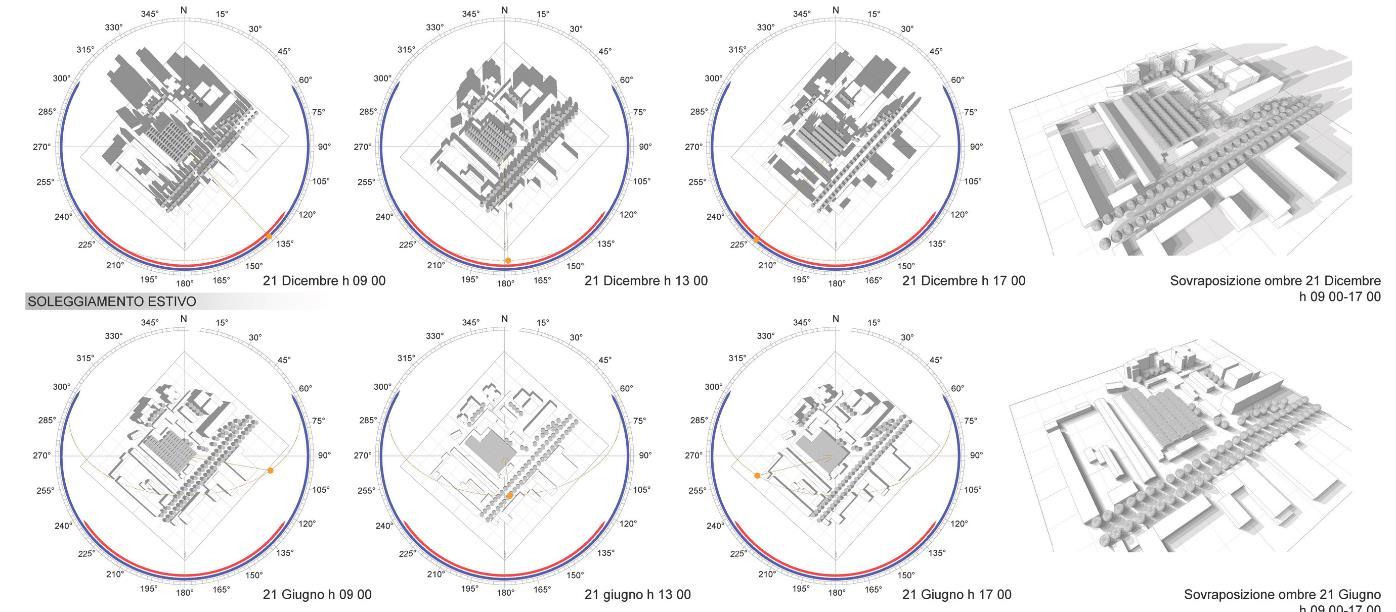

Figure 2.48. Solar exposure analysis of the site.....................................................................135

Figure 2.49 Façade exposure to the sunlight. 135

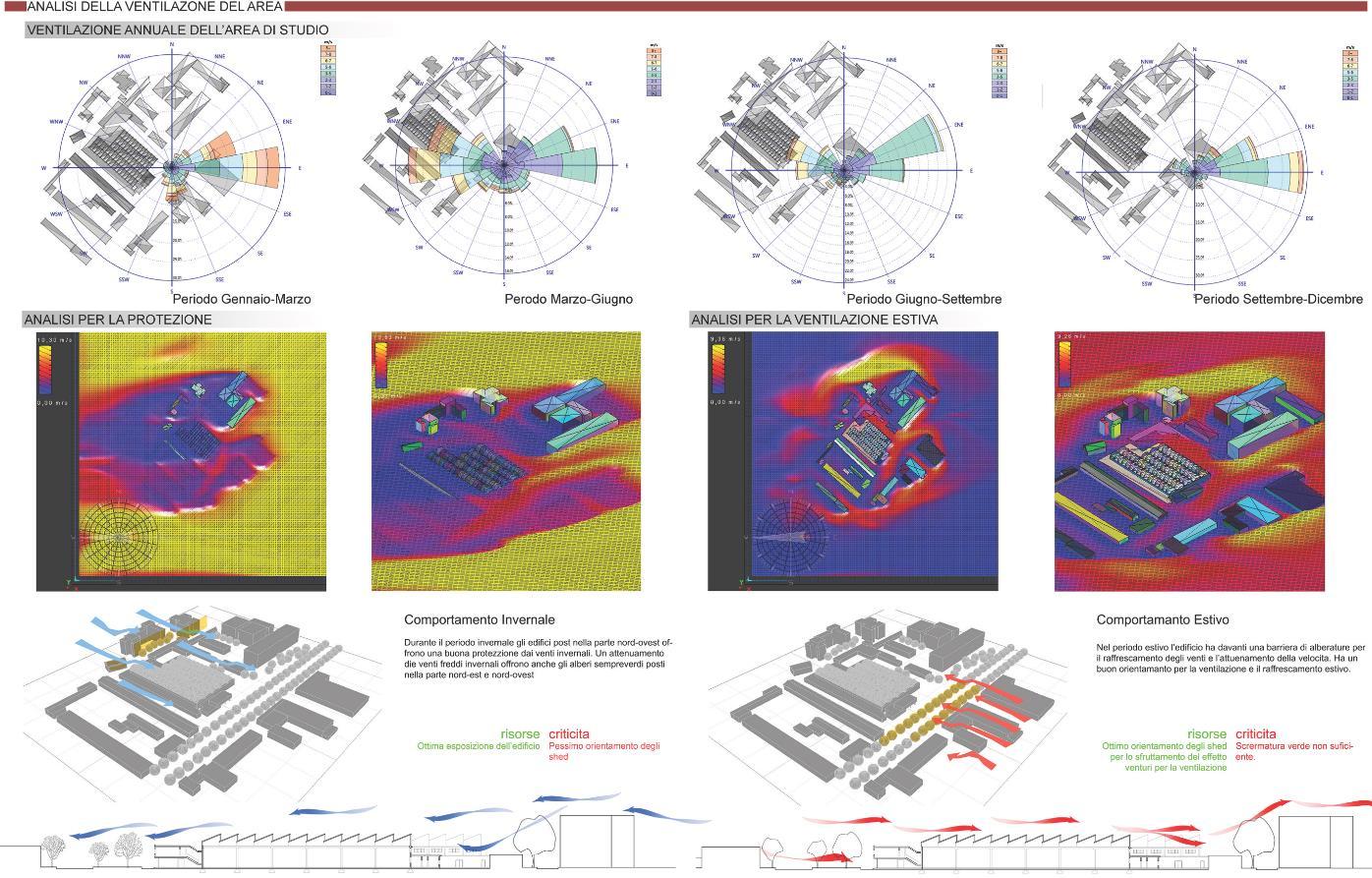

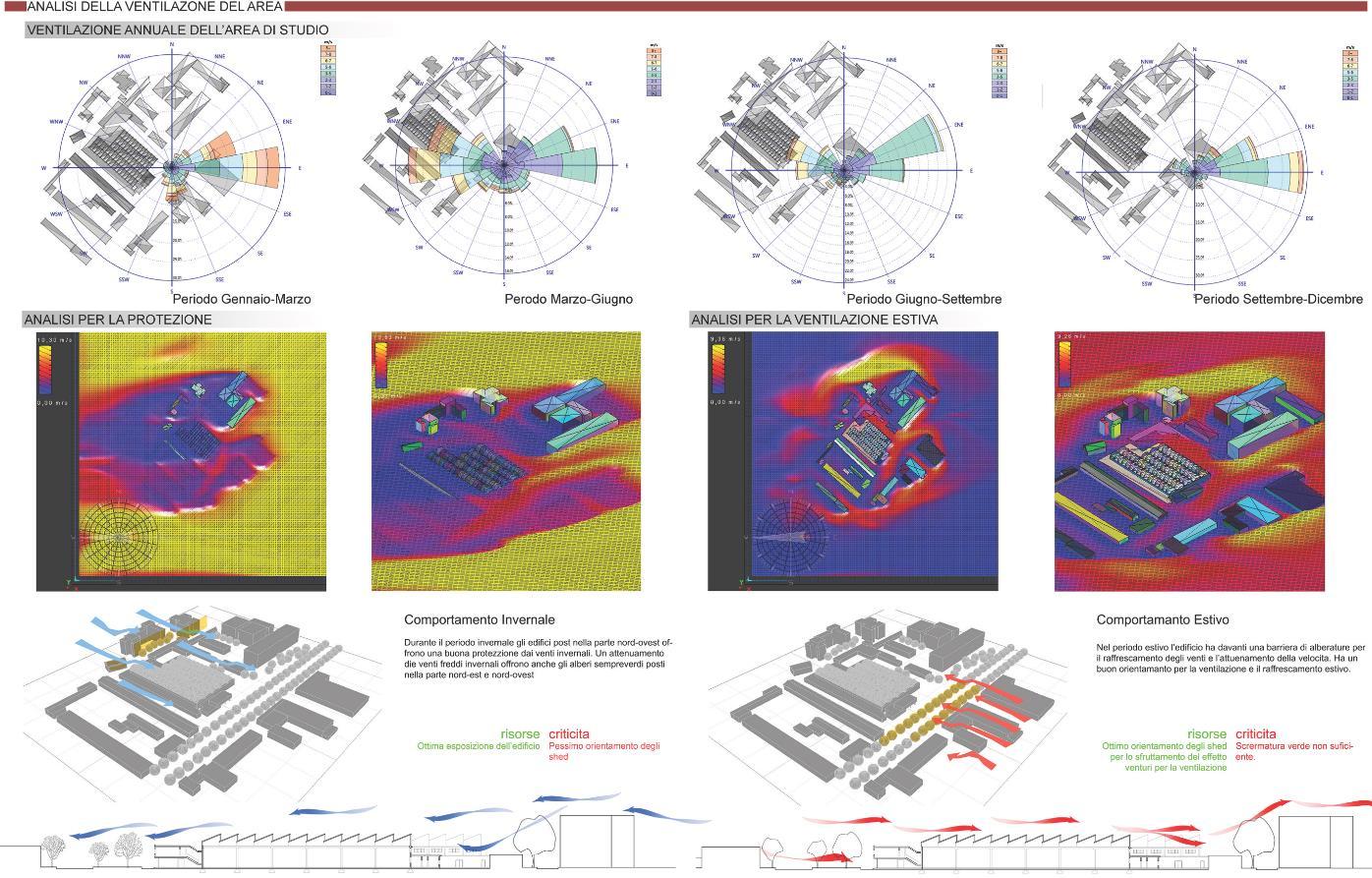

Figure 2.50. Natural Ventilation analysis. Source Author.....................................................136

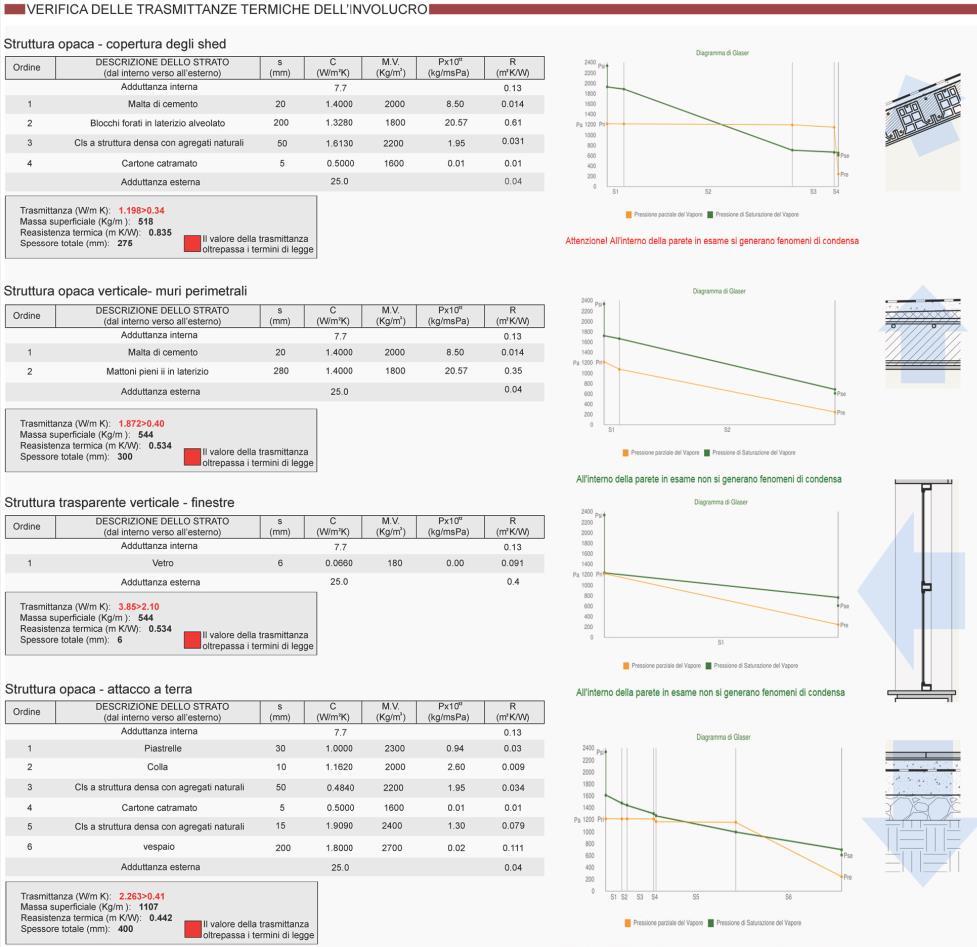

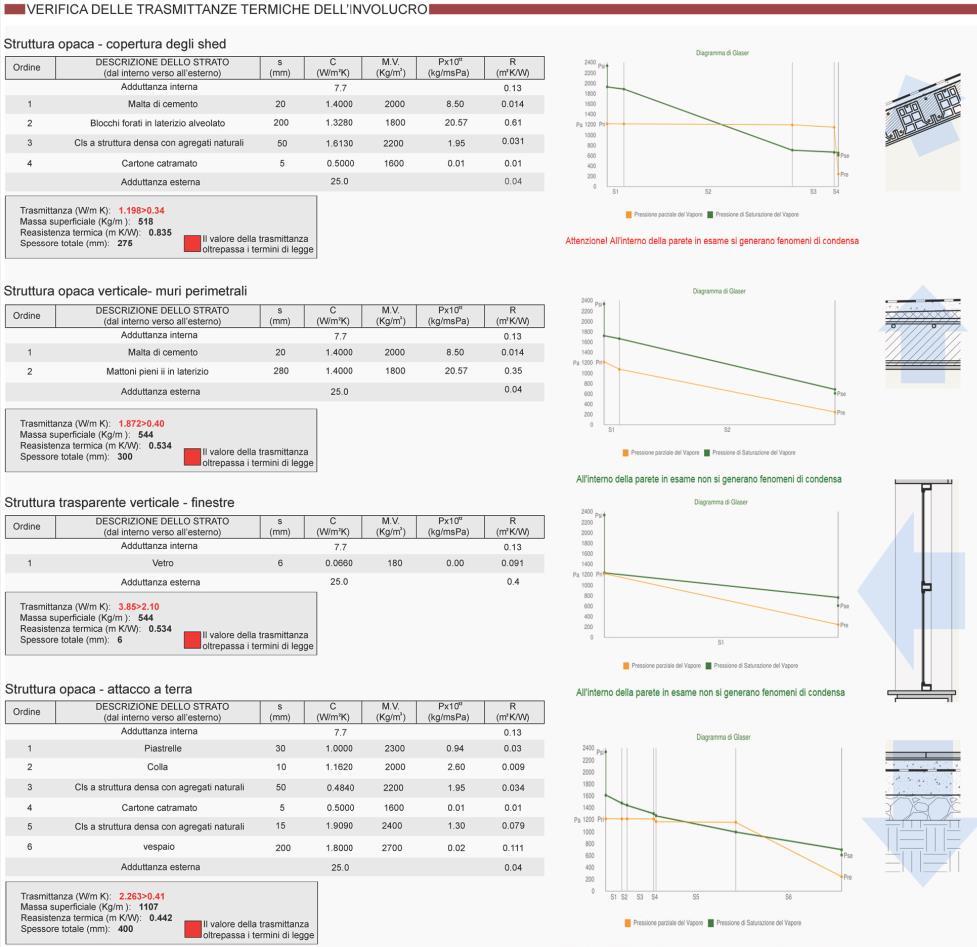

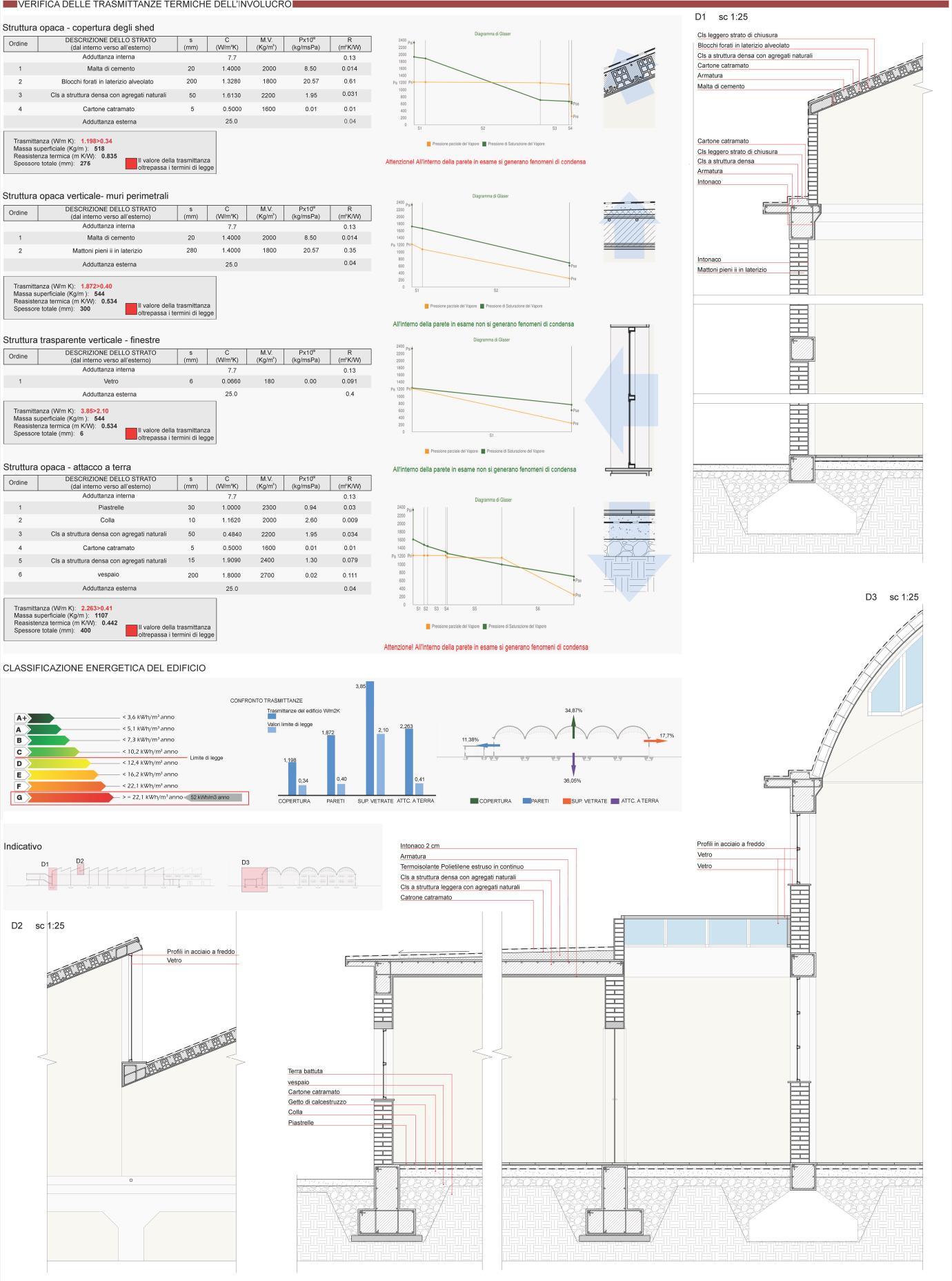

Figure 2.51. Enrgetik data of the existing situation 136

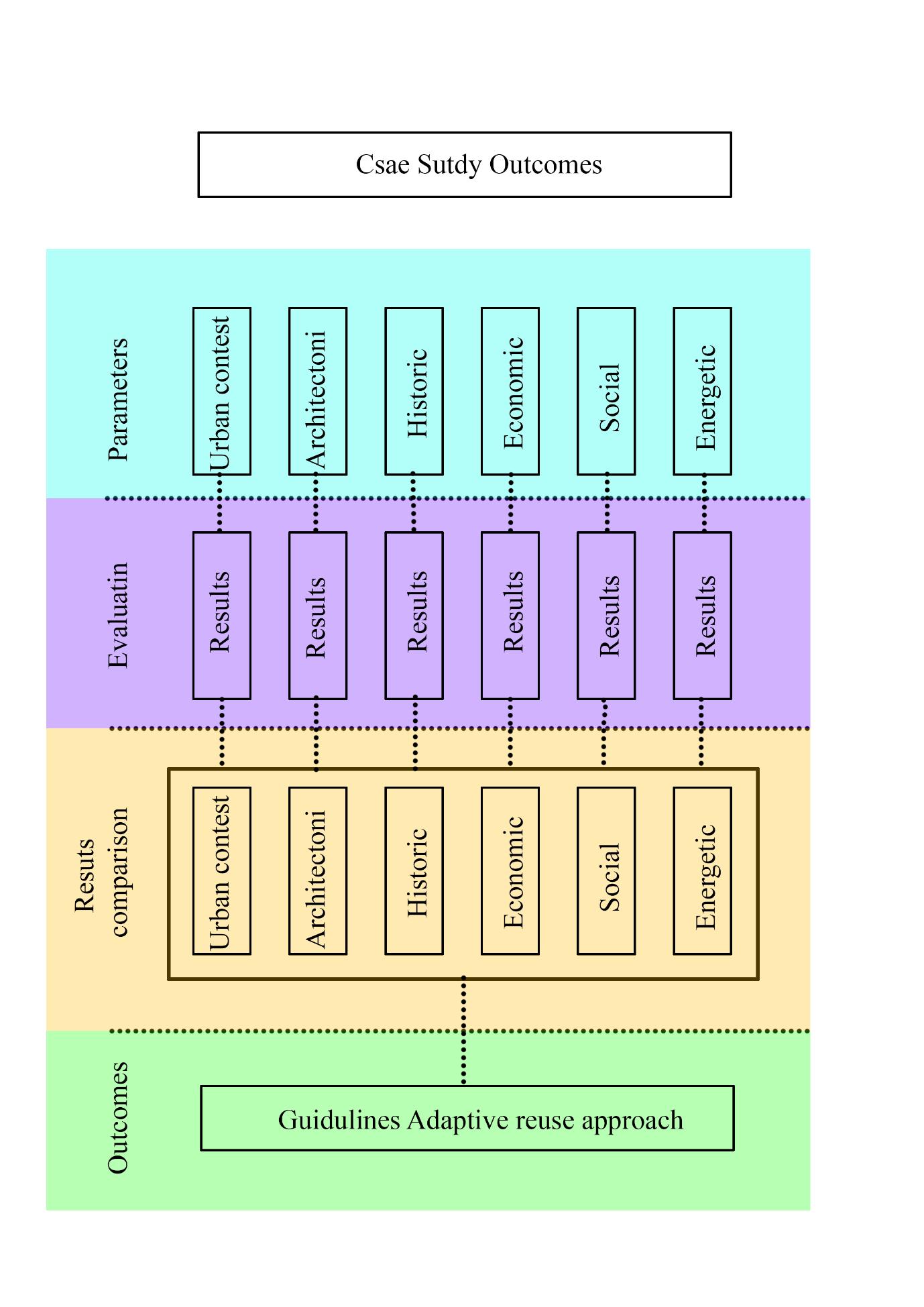

Figure 2.52. Comparison model diagram. Credits Author 140

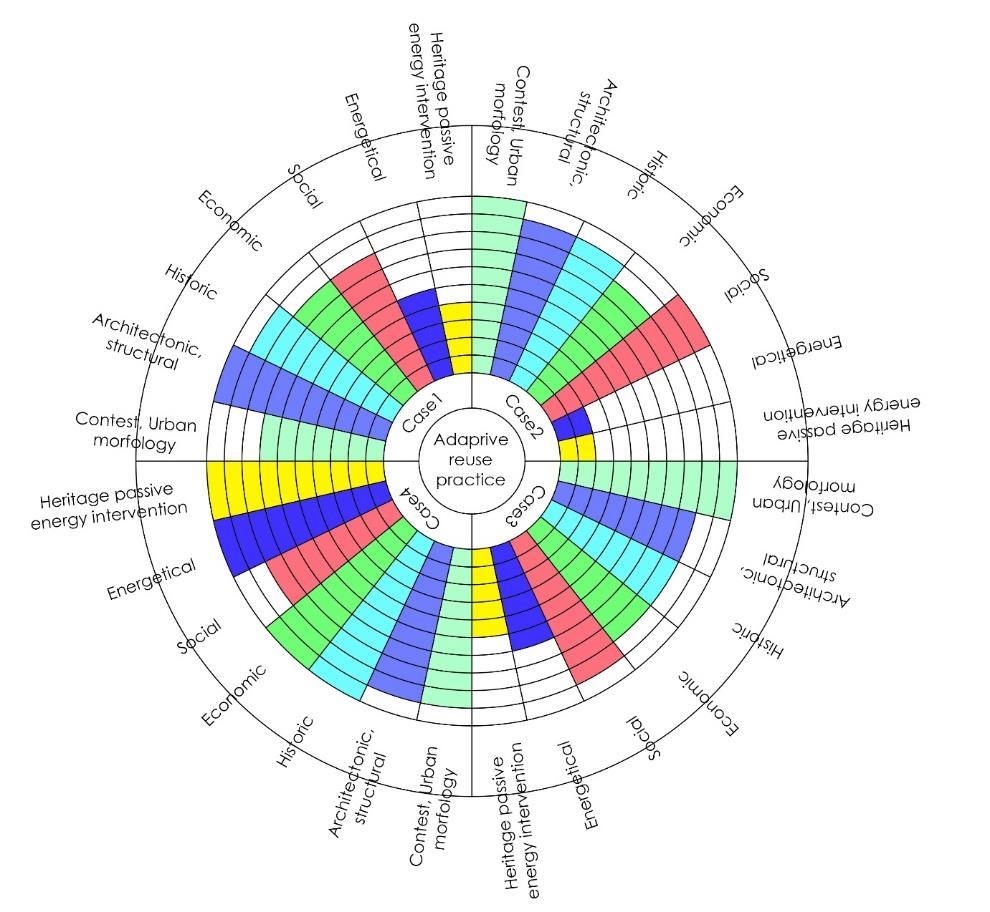

Figure 2.53 Comparison case studies diagram. Source Author.............................................141

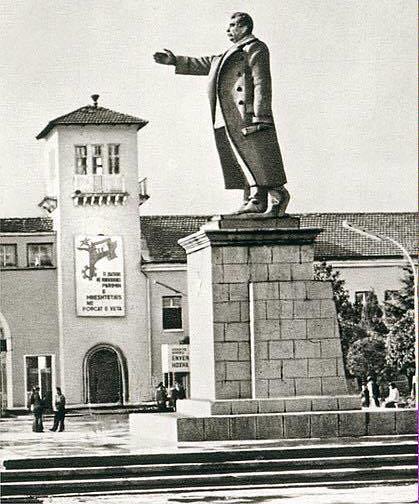

Figure 2.54 The square factory entrance. Source Archive 144

Figure 2.55 Eksisting situation of the building. Source Author ............................................145

List of tables

Table 1. Former Industrial sites of Tirana. Source Archive ....................................................95

Table 2. Final conclosions results table. Case 1 109

Table 3. Final conclosions results table. Case 2 118

7

Table 4. Final conclusions results table. Case 3 127

Table 5 Final conclosions results table. Case 4.....................................................................137

Table 6 Sumary Table. Points totalisation of the case studies...............................................141

8

Adaptive, Reuse. Albanian industrial heritage reuse through passive systems in architecture

Abstract Subject of the scientific Research

During the communist regime Albania closed its economy toward the outside this strategy required for the Albanian economy to sustain itself with on her own resources based on the situation it developed a net of industrial structures now days gone in disuse that has been abandoned for almost 30 years for economic cultural mnemonic reasons demolition shouldn’t be an option the reuse of these industrial sites but considered a resource. The reuse is to be considered a plus value.

Building adaptive reuse has become a very important global topic since the studies brought out the effects of not taking in consideration how would this affect our habitat. In the context of sustainable development and the effects of climate change caused by previous disregard for our environment, adaptive reuse has significant implications. This study proposal looks at how the building sector may restructure itself to put more emphasis on revitalizing existing structures rather than demolishing and replacing them. The adaptive reuse must be planned from the beginning, and if done wisely and consistently, it will offer a way to achieve sustainable goals without lowering investment levels or the industry's economic viability. In fact, I believe that the building business will thrive via adaptive reuse. It is the right time to gain consciousness for the future generations and to build responsibly we must leave them the memory of the past and the bases for the future in the meantime we must improve our conditions of life. The reuse is the answer to these problems. Abandoned industrial sites have the potential of becoming new centers of cultural life commerce and social

Theoretical approach

9

Deindustrialization in Albania has resulted in the abandonment of large industrial regions as well as the depopulation of such areas. How to reactivate industrial sites is now the difficulty. Comprehensive studies of the state of the art of the town's industrial archaeology, as well as public debates and strategic actions of urban policy making that trigger evidence based territorial policies for a sustainable and integrated development, are necessary before we can creatively restore the abandoned industrial areas for future generations while fully respecting the old values and traditions.

The idea of reuse serves as the foundation for the theoretical approach to sustainability and conservation of industrial archaeology. When I initially saw some of the old industrial districts, this was the first thing that crossed my mind. According to contemporary ideas of sustainable urbanization, which emphasize that by 2050, 80% of the world's population would be concentrated in cities, not every corner of the earth can be an urbanized area. Overcrowding and a lack of fertile surfaces will come after that. Reusing structures in this way is thus important.

The fact that former industrial zones are a part of our nation's architectural legacy is another incentive to address reuse. This is because the construction industry during the '60 '70 was committed and put a lot of work and attention in the construction of these structures. Additionally, industrial areas took up a lot of space in the city and its suburbs, so even after they were abandoned, there was still a good reason to use those spaces again. Revitalization is another significant theoretical notion for the former industrial districts of Albania. After being abandoned, these sites have attracted undesirable behaviors that are bad for the neighborhood and the zone.

Hypotheses

The objective of this research is to try to verify how the technology can be used to an approach of re use of this type of architecture which are the principles by which we can restore abandoned industrial buildings. The industrial architecture is distinguishable for the versatility of the space and initial hypothesis is that how such a space can be recovered by recovered, its flexibility and the hybridization of functions that can be developed within it. The methodology how to verify this hypothesis passes through the analysis of the abandoned space in the current situation, the construction of a scenario that combines the above mentioned strategies and the verification of them through simulated studies of the space in a project. The expected outcome

10

of this verification is that of creating a space that is able to revitalize the surroundings and the context where it is placed.

Research objectives and limitations

The objective of this project is to review abandoned industrial buildings and, using ideas and techniques, to identify technical alternatives to repurpose this typology of structures in the Albanian environment. In order to comprehend the change through time and space, the features that have changed due to the advancement of technology, and the primary functional and technical components of these industrial buildings, the design and adaptation of industrial structures will be explored.

Research Questions

The aim of this thesis is to test the developed holistic framework on the mentioned project with three underlying research questions, which are:

• Which are the principles and strategies in the technological contest for rethinking abandoned industrial buildings inside the city?

• How can we use technological development to preserve the characteristics of this typology of architecture?

• How can technological development of today contribute in a sustainable re use framework of abandoned industrial architecture?

11

Methodology

Figure 0.1 Methodology diagram. Credits Author

Prelude. The de industrialization process has left behind in Europe a significant amount of unused industrial buildings. For decades, the common practice in the built environment that bares any sort of significant value, has been to preserve the original appearance or protect the monumentality to the maximum extent possible and replacing other structures with new ones when they become obsolete and in disuse, physically unsafe, or outmoded. If Europe separates legacy from development, it risks becoming a museum stuck in the past, unable to evolve and create. This thinking, however, has changed in the last decade. As an urban, architectural, and conservation concept, the adaptive reuse approach toward buildings and abandoned industrial siteshasbecomemoreessentialandnecessary.Alotoffactorshavedriventhisshiftinstrategy. The consumption of land in favor of the built environment restricts new construction; It is difficult to protect all cultural assets in a purely restorative way due to the rising scope of heritage conservation boards as well as the increasing quantity and diversity of listed buildings and sites. This essentially removes them from social life. Because of the expanding responsibilities of heritage conservation boards and the growing number and variety of buildings and sites that are on the national register of historic places, it may be challenging to safeguard all cultural assets in a manner that is simply restorative. Because of this, they are effectively cut off from society. As a result of the current economic crisis, governments are unable to contribute a considerable amount of money towardthe conservation of historical sites and artifacts. Because of this, heritage is considered a valuable resource that has the potential

12

to offer additional benefits to society on a variety of fronts, such as the tourism industry, culture, society, and the economy. As a result, heritage is regarded as a valuable resource that has the potential to offer additional benefits to society. In contrast perspective, repurposing older buildings for contemporary or ongoing use is a challenging endeavor. It is a process of revaluation or establishing a new equilibrium between numerous types of values, ranging from historical and conservational values to architectural, sociological, and economic values, and it is not just about aesthetics. It is not just about aesthetics because it is not just about aesthetics. This challenging undertaking, rather than preserving the historic fabric of a structure, tries to unleash the full potential of its history, based on the audacious premise that a monument's or site's heyday may be in the future. In comparison, the process of reusing older structures for more modern or continuing use may be a difficult and time consuming task. It is a process of revaluation or establishing a new equilibrium between numerous types of values, ranging from historical and conservational values to architectural, sociological, and economic values, and it is not just about aesthetics. It is not just about aesthetics because it is not just about aesthetics. Because it is not only about aesthetics, we cannot simply say that this is just about looks. This hard endeavor, rather than maintaining the historic fabric of a building, attempts to release the full potential of its past. This endeavor is founded on the bold concept that a monument's or site's heyday may be in the future. Which of these functions is most suited for which kinds of building? And what are some inventive ways in which you may combine the modern with the traditional? The central problem with adaptive reuse, on the other hand, extends beyond the existing structure and addresses a more strategic approach: how can the legacy of the past which includes physical heritage, narratives, traditions, and values be transmitted to the future in a way that recognizes and engages them in the process of constructing the future? Unquestionably, this is a problem that is applicable in contexts more than just that of Europe. The challenge of addressing the material remnants of the past while simultaneously working for improvement and advancement is a topic that affects every society. Throughout the course of the previous decade, significant conferences representing a wide range of disciplines have focused on adaptive reuse as a central problem. WiththefallofberlinwallturmoilbegintofollowintheformercommunistcountriesinEurope Albania made no exception. December 1990 came with the student’s movement the which was followed by the fall of the regime. With the downfall of the regime came the de structurization of the hierarchy of the industry in a scale unseen before which led to a slow total abandonment of the industrial sites. Time has led to almost a total decay to this typology of architecture.

13

Apart some vernacular adaptive reuse of the abandoned stock of these industrial buildings the rest still lies abandoned waiting to be retrofitted.

14

This page is left blank intentionally

15

Definitions.

Trying to understand the adaptive reuse through definitions.

In order to have a better understanding of what is meant by the term "adaptive reuse," research of definitions and terminology of a variety of similar ideas that crop up often in the world of architecture is conducted. These concepts and definitions include adaptation, renovation, refurbishing, retrofitting, rehabilitation and more. The concept of adaptive reuse encompasses both the act of retaining the historical character of a building while also putting it to an entirely other purpose. According to Latham's definition of adaptive reuse, this kind of reuse “extends the period from cradle to grave for a building by keeping all or most of the structural system and other characteristics, such as cladding, glass, and interior walls” (Latham, 2000).

This strategy is seen as a sustainable means of reusing places or buildings that have become outdated as a result of changes brought about by advancements in technology, changes in law, and changes in economic situations, according to the notion of adaptive reuse.

This part of the study contains a list of literature related terms along with their respective definitions. According to Douglas, adaptation refers to any attempt that is made to enhance the capacities, capabilities, or performance of a structure (Douglas, 2006). The International Council on Monuments and Sites ICOMOS defined adaptation as “any step made to enhance the adaptability of a site for its intended use” (ICOMOS, Burra Charter, 2013). This definition was published in the 2013 issue of the organization's journal.

In the world that has been built, adding is often employed as a means for recycling resources that have been used in the past. A building may increase its total square footage as well as the number of story’s by undergoing an expansion or an extension. An extension may be accomplished by increasing either the height or depth vertically, or the breadth of the floor plan horizontally (Douglas, 2006). An extension is “a form of addition that aims to create new aspects of an existing company with relative independence while increasing the knowledge of the original structure” (Byard, 2005) as defined by Byard, whose book is titled “The Architecture of Additions: Design and Regulation.”

Adaptation

“Any work to a building over and above maintenance to change its capacity, function or performance”.

16

(Douglas, 2006)

Addition

“Additions cannot be allowed except in so far as they do not detract from the interesting parts of the building, its traditional setting, the balance of its composition and its relation with its surroundings”.

(ICOMOS, The Venice Charter, 1964)

Alteration

“Modifyingtheappearance,layout,orstructureofabuildingtomeetnew requirements.Itoften forms part of many adaptations’ schemes rather than being done on its own”. (Douglas, 2006)

Conservation

“The conservation of monuments is always facilitated by making use of them for some socially useful purpose” .

(ICOMOS, The Venice Charter, 1964)

“All efforts designed to understand cultural heritage, know its history and meaning, ensure its material safeguard and, as required, its presentation, restoration and enhancement. (Cultural heritage is understood to include monuments, groups of buildings and sites of cultural value as defined in article one of the World Heritage Convention)”.

(ICOMOS, The Nara Document of Autenthicity, 1994)

“Preserving a building purposefully by accommodating a degree of beneficial change”. (Douglas, 2006)

“The purpose of conservation is to care for places of cultural heritage value. Conservation means all the processes of understanding and caring for a place so as to safeguard its cultural heritage value. Conservation is based on respect for the existing fabric, associations, meanings, and use of the place. It requires a cautious approach of doing as much work as necessary but

17

as little as possible, and retaining authenticity and integrity, to ensure that the place and its values are passed on to future generations”. (ICOMOS, New Zealand Charter, 2010)

Conversion

“Making any kind of building more suitable for similar use also, for another type of occupancy, either mixed, single use type” . (Douglas, 2006)

Extension

“a Expand the capacity: b volume of an object, whether vertically by increase the height depth; c laterally by expanding the plan of it”. (Douglas, 2006)

Maintenance

“If you “maintain your monuments properly, you will not need to restore them. A few sheets of lead placed in time on a roof and a few dead leaves andsticks removed in time from a waterway will save both the roof and the walls. Observe an old structure with vigilance; protect it as best you can and at all costs from all causes of deterioration. Count its stones as you would the jewels of a crown; a set guards about it as you would the gates of a besieged city; b bind it together with iron where it loosens; c support it with timber where it declines; d do not mind the unsightliness of the aid; e better a crutch than a lost limb; and do this tenderly, reverently, and continually,andmanya generationwill yet beborn and diebeneathitsshadow.Its dreadful day must come, but let it come openly and publicly, and let no dishonorable or dishonest substitute deprive it of the memorial services” ” (Ruskin J, 1880)

“It’s “therefore for all these buildings, of all times and styles, that we plead, and call upon those who must deal with them, to put Protection in place of Restoration, to stave off decay by daily care, to prop a perilous wall or mend a leaky roof by such means as are obviously meant for

18

support or covering, and show no pretense of other art, also to resist all tampering” with either the fabric or ornament of the building as it stands; if it has become unsafe, then” . (Morris, 1887)

“Continual activity to ensure the longevity of the resource without irreversible or damaging intervention”.

(ICOMOS Appelton Charter, 1989)

“Maintenance means regular and on going protective care of a place to prevent deterioration and to retain its cultural heritage value”.

(ICOMOS, New Zealand Charter, 2010)

“Maintenance means the continuous protective care of a place, and its setting”.

(ICOMOS, Burra Charter, 2013)

Modernization

“Bringing a building up to the current standards as prescribed by occupiers, society and/or statutory requirements” . (Douglas, 2006)

Preservation

“When we speak of the modern cult of monuments or historic preservation, we rarely have de liberate monuments” (Riegel, 1903)

“

Preservation is no longer a retro active activity but becomes a prospective kind of activity” . (Koolhaas, Preservation is overtaking us, 2015)

“Preservationfocuses mainly onthe maintenanceand repairsof existinghistoricmaterials also, retention of a property’s form as it’s has evolved over time. It includes protection and stabilization measures” .

19

(Douglas, 2006)

“Preservation means to maintain a place with as little change as possible” . (ICOMOS, New Zealand Charter, 2010)

“Preservation means maintaining a place in its existing state and retarding deterioration”. (ICOMOS, Burra Charter, 2013)

Reconstruction

“The re establishment ofwhat occurred or whatexistedinthepast,onthebasis of documentary or physical evidence. Reconstruction, in other words, re creates vanished or non surviving portions of a property for interpretative purposes”. (Douglas, 2006)

“Reconstructionisdistinguishedfromrestorationbytheintroductionofnewmaterialtoreplace material that has been lost. Reconstruction means to build again as closely as possible to a documented earlier form, using new materials”. (ICOMOS, New Zealand Charter, 2010)

“Reconstruction means returning a place to a known earlier state and is distinguished from restoration by the introduction of new material”. (ICOMOS, Burra Charter, 2013)

Refurbishment

“Modernizing or overhauling a building and bringing it up to current acceptable functional conditions. It is usually restricted to major improvements primarily of a non structural nature to commercial or public buildings. However, some refurbishment schemes may involve an extension”. (Douglas, 2006)

“Work that is related to a change in performance”. (Watson, 2008)

20

Rehabilitation

“Modification of a resource to contemporary functional standards which may involve adaptation for new use”.

(ICOMOS Appelton Charter, 1989)

“Work beyond the scope of planned maintenance, to extend the life of a building, which is socially desirable and economically viable. It is a term that strictly speaking is normally confined to housing. Rehabilitation can also be defined as “the act or process of making possible a compatible use for a property through repair, alteration and additions while preserving those portions or features which convey its historical, cultural or architectural values”. It acknowledges the need to alter or add to a historical property to meet continuing or changing uses while retaining the property’s historic character”. (Douglas, 2006)

Renewal

“Substantial repairs and improvements in a facility or subsystem that returns its performance to levels approaching or exceeding those of a recently constructed facility” . (Douglas, 2006)

Renovation

“

Upgrading and repairing an old building to an acceptable condition, which may include works of conversion” . (Douglas, 2006)

Repair

“Take proper care of your monuments, and you will not need to restore them”. (Ruskin, 1849)

Restoration

“Both the term of restoration and basic the concept of restoration are relatively recent inventions. Restoring a structure means putting it back together in an unachievable level of

21

perfection that existed at no other point in time. Thoughts of restoring older structures have only been explored since the first quarter of this century, and to our knowledge, no one has yet provided a coherent definition of architectural restoration. Perhaps it's best to start by trying to pin down just what it is that we mean, or at least should mean, when we talk about restoration.” (Voillet Le Duc, 1875)

“A strange and most fateful idea, which by its very name implies that it is possible to strip from a building this, that, and the other part of its history of its life that is and then to stay the hand at some arbitrary point, and leave it still historical, living, and even as it once was.” (Morris, 1877)

“It means the most total destruction which a building can suffer: a destruction out of which no remnants can be gathered: a destruction accompanied with false description of the thing destroyed. Do not let us deceive ourselves in this important matter; it is impossible, as impossible as to raise the dead, to restore anything that has ever been great or beautiful in architecture” . (Ruskin, 1889)

“Restoration is generally understood as any kind of intervention that permits a product of human activity to recover its function … Restoration is the methodological moment in which the work of art is appreciated in its material form and in its historical and aesthetic duality, with a view to transmitting it to the future” (Brandi, 2000)

“Its aim is to preserve and reveal the aesthetic and historic value of the monument and is based on respect for original material and authentic documents”. (ICOMOS, The Venice Charter, 1964)

“The return of something to a former, original, normal, or unimpaired condition”. (Stubbs, 2009)

“Restoration means finishing an incomplete structure”. (Giebeler, 2009)

22

“The term restoration generally refers to the process of reassembling and reestablishing something, but it can also refer to the elimination of accretions that diminish the historical significance of a location. Restoring anything is putting it back together the way it was or removing the things that make it less significant as a cultural landmark” .

(ICOMOS, New Zealand Charter, 2010)

Retrofitting

“Reconstruction of an old structure or component to upgrade it to current standards, accommodate new technologies, or improve functionality in ways not anticipated by the original architect. Retrofitting, in other words, is the process of updating an existing structure with modern features that were unavailable during its original construction” (Douglas, 2006)

“This research through definitions demonstrates how difficult is today to navigate and to define the adaptive reuse practice. Since, various authors, historians, architects, urban planners that have worked in the field of architecture and the preservation of the historical heritage, have tried to give definition to process related to adaptive reuse approach still today we haven’t inherited a clear definition of the process. Adaptive reuse is a complex and multidisciplinary process that is put to practice and achieved according to possibilities economic and social conditions that a country has”

23

1. Historical development of adaptive reuse approach.

1.1.Reuse building adaptation. literature overview on building adaption reuse theory

Giving new functions to buildings is a process and activity that is not as new as many people believe. Giving a structure that had lost its primary function a new function was a common practice that was not always accompanied by a precise design or program. Buildings that were structurallysecureinthepast were easilychangedto meeta newdemandor function. Buildings that have been converted and repurposed by changing the function of the original building partially or completely are abundant in urban development and architecture history. Following the French Revolution, there was a surge in the reuse of ecclesiastical structures as industrial or residential structures. However, these improvements were carried out in a practical manner, with little regard for heritage preservation. Instead, it was primarily practical and financial considerations that drove reuse (Powell, 1999). During my time in Rome, Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri impressed me as an excellent example of adaptive reuse. Michelangelo Buonarotti based his new design on the remains of Diocletian's public baths.

Figure 1 1. Aincent rome map. Source wikiedia

24

Sherban Cantacuzino explained adaptive reuse in detail, stating that because the structure appears to exceed the purpose, structures have been continually modified to new uses a fact that has enabled generations to get a sense of connectedness and stability from their immediate surroundings (Cantacuzino, 1975). Adaptive reuse has gotten relatively little attention in the literature or architectural history of adaptive reuse, despite the fact that experts in architecture history and planners such as Aldo Rossi, Perez De Arce have studied this sort of building conversion. In the subject of architectural history, adaptive reuse has similarly garnered relatively little attention. According to De Arce, reusing previously constructed housing is a vital component of urban development since it contributes in three separate ways to the improvement of a community's unique characteristics. There is a greater likelihood that existing structures will be used permanently. Second, since it entails recycling materials already on site and maintaining regular routines, it may save money in both the physical and social spheres. Finally, as he adds, it creates a sense of 'place' in both historic and geographical elements:

25

Figure 1.2 Dioclecian Baths. Source Wikipedia

“…a true complexity and a meaningful variety arise from the gradual accumulation of elements which confirm and reinforce the space in an incremental process. This sense of continuity is further reinforced by the intelligence of successive generations which, through trial and error, produces a type of architecture which, by being so meaningful in social terms, by being elaborated with the concurrence of so many people, becomes almost necessarily a product of great quality”. (Perez De Acre, 2014)

De Arce utilizes a drawing technique in his work to illustrate the evolution of illustrative buildings and locales over time and geography. Given how well it illustrates the notion of palimpsest, his work is especially pertinent in the domains of architecture, conservation, and urban planning. Machado came up with this word to describe the complex histories of these buildings from the perspectives of both materiality and narrative (Machado, 1976). In his book The Secret Lives of Buildings, Edward Hollis delves into the ephemeral and narrative aspects of organic architectural development. (Hollis E. , 2009). Hollis explores the ways in which historic buildings are "taken, hijacked, replicated, translated, mimicked, mended, and anticipated" during the course of their life in a book formatted into 13 episodes.

1.2.Adaptive

reuse and building conservation dialogue.

Until the seventeenth century, old structures were converted for utilitarian or commercial use. In the eighteenth century, the notion of 'legacy' became prominent, and one of the primary themes of discussion was how to deal with these sorts of remnants from previous decades. The argument took place, and Viollet le Duc's restoration theories. The other was John Ruskin support for conservation theories. In the architectural preservation history, the French Revolution was a defining moment. During this time of profound social and political change, the absolute monarchy that had dominated France for centuries crumbled,and historic concepts of monarchy, aristocracy, and clerical power were rapidly dismantled. The Enlightenment proposed a whole new set of ideas to replace these long held beliefs, on which the ostensibly new society was founded. After its creation as an institute on November 1789, the National Assembly declared that all Church property, including buildings, lands, properties and works

26

of art, would be seized to address the governments' financial concerns. Right After that, they sold the seized assets, anyway numerous important buildings were kept as state property. This commission (Commission des Monuments Historiques) was assigned responsibility for a number of the buildings that were seized and protected as state property. When the haze from the Revolution had cleared away in the year 1837, the commission was split up, which allowed for the foundation of a second organization that was responsible for historic monuments. In the nineteenth century, Le Duc served as the first head inspector for the Commission des Monuments Historiques. He was responsible for overseeing the preservation of historical sites (Jokilehto, 2017). Le Duc was an architect and principal inspector for a variety of restoration projects. The Cathedral of Paris, the stronghold of Pierrefonds, and the castle of Carcassonne are examples of Gothic architecture. His intended interventions were often substantial when he worked on the problem of restoration; in some cases, the interventions included the addition of 'new elements' to the structure, although 'in the style of the original. The nationalist mindset, which considered old buildings to be historical monuments that needed to be repaired in order to demonstrate the nation's "achievements," was the foundation for this kind of strategy. Despite the fact that the restoration movement was a national movement, Le interpretation Duc's and the practice of the restoration movement had an influence on a global scale. This particular kind of restoration was also supported by well known architects though Europe. The Le projects and Duc's writings provide us a clearer picture of what the situation included and the reasons why it is still pertinent to this day. Even in the present day, there is a resonance with the following in his ideas of adaptive reuse:

"The best of all ways of preserving a building is to find a use for it, and then to satisfy so well the needs dictated by that use that there will never be any further need to make any further changes in the building. . . . In such circumstances, the best thing to do is to try to put oneself in the place of the original architect and try to imagine what he would do if he returned to earth and was handed the same kind of programs as have been given to us”. (Violet le Duc, 1854)

Le Duc asserts unequivocally that in order to repurpose an older structure, contemporary architects need to modify it in a way that is transparent, simple, and functional. This legislation is still important in present times because it sets a historical precedence for the contemporary modification of the physical characteristics of historic buildings. In some ways, it echoes Fred

27

Scott's concept of ‘sympathy,' which he articulated in his 2008 book “On Altering Architecture”. In that book, he compares the process of restoration to the process of poetry translation, both of which require ‘sympathy.' In other words, it's an echo of Fred Scott's concept of ‘sympathy':

“Translation in poetry is akin to the work of bringing a building from a past existence into the present. This carrying over of meaning in poetry is recognized as a work requiring inspiration equivalent to that of the original author and so similarly, one might come to view restoration as an art equivalent to any other related to building”. (Scott, 2008)

Although his multinational and historically long term significance, Viollet le work Duc's and beliefs have not been without criticism. Experts in the past and present have been critical of his method. This type of restoration, wasn’t supported by Ruskin. According to Ruskin, is "a demolition followed by a misleading representation of the building destroyed" (Ruskin, 1849) .He also described it as "the most complete annihilation that a structure can endure" (Ruskin, 1849). Ruskin claims that anything once wonderful or lovelyin architecture cannot be restored; this is as impossible as raising the dead. Don't bring up restoration at this point. From inception to finish, everything about it is a lie. You won't need to repair your monuments if you take good care of them. John (Ruskin, 1849). Ruskin emphasizes his pure conservative ideology, which is based on the protection and the maintenance of the building over the destructive characteristics of Viollet le Duc’s restorations. Morris, later founded the Society for Protection of the Ancient Buildind (SPAB) in 1877 . The SPAB considered historic buildings to be one of a kind works of art, the type that would have been produced by an artist in a particular historical location. They believed that age contributed to the beauty of a construction, and as a result, the signs of age were considered to be a vital part of any item or structure. As a consequence of this, these buildings should not be torn down or refurbished,rather, they should be conserved, and their duties should not be changed in any way. In their manifesto, they make the following declaration: It is for all of these structures, of all periods andstyles, thatwe plead, and call upon those who have to deal with them, to put protection instead of requalifying , to fend off deterioration by constant care. He states>

“…if it has become inconvenient for its present use, to raise another building rather than alter or enlarge the old one; in fine to treat our ancient

28

buildings as monuments of a bygone art, created by bygone manners, that modern art cannot meddle with without destroying”. (Morris, 1977)

The structure should be left to exist as it is and reflect its own character and history, according to the anti restoration followers. It must be preserved. Across the 19th adn20th centuries, the contrasts between these two methods were the subject of heated dispute. The difference in interpretation of the idea of authenticity was at the center of this debate, despite the fact that Viollet-le-Duc, Ruskin, and Morris never used the phrase.

1.3. The concept of adaptive reuse as an innovative strategy for the built environment in the perspectives this movement of architects was accompanied by a shift in the ideas around conservation. Up until the seventeenth century, antiquated and medieval buildings were the only kind of constructions considered historic. An understanding of the value of buildings from earlier eras of history had evolved as a consequence of the destructions that occurred during WorldWarsI andII.In addition,aninterestin other typologies as beingworthy ofconservation had also emerged as a result of these wars. Conservationists were now regarded to be responsible for vernacular architecture, industrial structures, and even entire historic cities. In this new and broader environment, the number of structures that could need to be 'conserved' rose dramatically. Inevitably, a rethinking of conservation evolved, which was represented in the Venice Charter of 1964, which emphasizes the necessity of 'adaptive reuse' as a sort of 'conservation' practice. The protection of antiquities is usually helped by using them for some socially valuable purpose, it says. As a result, in the 1960s and 1970s, architects' and conservators' ideas merged. The integration of ideas may be seen in both the theories of conservation and restoration and their respective publications. During May of 1972, “New Uses for Old Buildings” was published in which it examined the subject of adaptive reuse, also known as adaptive re use (Cantacuzino, 1975). It was also obvious in two international conferences conducted in Glasgow and Washington, D.C. in 1977, titled “Old into New” and “Old and New Architecture: Design Relationship” The contents of both sessions were published in 1978 as a book, laying the groundwork for the creation of a new field (Machado, 1976). Machado, that released Architecture as Palimpsest in 1976, was an early proponent and

29

benefactor of this new free theoretical setting. Machado uses palimpsest as a metaphor to transcend the 'internal struggle' between the restoration and anti restoration groups, as well as the exterior dispute about whether architectural design must be built on a tableau rasa. A word used to describe any surface in the which is inscribed where a text has been excised so that another textmay be inserted in its place. When writing materials were cleaned away and reused in antiquity, the term was used broadly. The expense and rarity of vellum in late classical and medieval periods were so significant that it was routinely saved after the text that had been engraved thereon had been neglected. The rebuilt architectural work itself may also be seen as a text of a unique sort that is distinguished by the juxtaposition and co presence of other texts, making it comparable to certain architectural drawings and palimpsests. Remodeling may be seen of as revising a building's initial discourse, which serves as the foundation for all subsequent formal discourses.” (Machado, 1976). Machado used the word "remodeling" to refer to "adaptive reuse," establishing a connection with writing in order to illustrate his point. This allowed him to see the stratification of formal interventions within an existing shape, which is adaptive reuse, as a creative act in and of itself. It was one that did neither damage the present context nor severely restrict its possibilities. It would serve as an example for how adaptive reuse may develop throughout the course of the next years.

1.4.Adaptive Reuse theories. Most discussed theories in the development of the Adaptive-Reuse practice

Early 1970s were a breakthrough point in the development of 'adaptive reuse' as a creative profession with conceptual or academic underpinnings. However, being recognized as a field does not imply that there is only one method or philosophy to modern reuse. In reality, in prior years, numerous theoretical perspectives coexisted. Each technique provides unique insights and highlights key challenges.

1.4.1. Approaching the Industrial Built Fabric by typology

In the 1970s, Cantacuzino was a pioneering researcher on adaptive reuse, authoring the book New Uses for Old Buildings in 1975. His book was based on an architectural review special issue that he edited in 1972. A history of adaptive reuse and its importance in modern

30

conservation practice is the subject of the book's opening article. It's followed by a collection of worldwide samples arranged by host space typology. Several scholars have taken Cantacuzino's approach, focusing their study on the topic of whether function(s) would be appropriate for specific typologies (Douglas, 2006). What Machado referred to as the form/function connection and this query are comparable. In this context, several studies on specific building types, including those of industrial and residential structures, have been conducted (Douglas, 2006). Machado criticized adaptive reuse theory for its emphasis on form/function relationships, claiming that it ignored the most fundamental question regarding the renovation of an existing structure. Machado wanted to discover which forms might producetheneededinteractionbetweenoldandnewwhilerepressing,preserving,orimproving the structure's meaning andvalues. Anadaptive reuseproject's excellence depends onhowwell the current building is adapted to the new program's functional and aesthetic needs. Adaptive reuse projects are becoming increasingly popular as a means to reduce environmental impact and save money. However, in depth research on the adaptive reuse of a specific architectural typemayhighlightitsuniqueattributesandhazardsandpossibilitiesassociatedtoitsadaptation and reuse. As a direct consequence of this, studies that make use of this typological method havebecomeevenmoretargeted,in depth,andcomprehensiveoverthecourseofthepreceding decade. Research was carried out on a variety of architectural types, including monasteries and churches, business buildings, and shopping arcades, among others. (Bie Plevoets, Koenraad Van Cleempoel, 2019).

1.4.2. Approaching the Industrial Built Fabric by Architecture

Machado, unlike Cantacuzino and other authors who have adopted a similar approach, has advocated for a more architectural approach that focuses on the form/form connection, investigating various design strategies for intervening within or on top of an existing structure. In his publication Architecture as Palimpsest, Machado uses literary metaphors like writing over, underlining, partly erasing etc to present many perspectives on building rehabilitation

31

The analogy between writing and building adaption is not new; Viollet le Duc drew a similar comparison in the eighteenth century when he remarked:

“If a single one [a capital] was missing it would be replaced with an ornament of the style in vogue at that time. It is for this reason that, in times before the attentive study of styles has been developed up to the point where it is today, replacements of this type were merely considered aberrations, and sometimes as consequence false dates were assigned to parts of an edifice that should rightly have been considered interpolations in an existing text”. (Viollet le Duc, 1967)

Machado's work had a great influence on scholarly study at first, despite the original concepts at the basis of adaptive reuse practice. Only in 1989 did they come to the attention of Robert, who utilized the palimpsest metaphor to illustrate the concept of conversion (on palimpsest as a metaphor for adaptive reuse). In a range of historical and contemporary contexts, Robert identifies seven "concepts of conversion.":

1. buildingwithin.Isaconceptthattriestoexplaintheideaofusingtheinteriorofthebuilding as a space to design in.

2. building over. Is a concept that tries to explain the idea of designing vertical additions to the building.

3. building around. Is a concept that tries to explain the idea of developing lateral additions to the building

4. building alongside. Is a concept that tries to explain the idea of developing lateral additions to the building not attached to the existing building.

5. Materials recycling. Is a concept that explains the idea of using the material of the existing building.

6. New function adaptation of the building according to the style

The above concepts make reference to a very specific intervention. After Machado, design techniques and intervention strategies for existing structures were identified by different authors:

(Brooker, 2017) distinguish among

7. Intervention on the existing

8. Insertion on the existing

9. Installation on the Existing

32

(Brooker, 2017) adds other strategies

1. Reconceptualization

2. Over use

3. Artifice

4. Narrative (Jäger, 2010) gives the definitions:

1. Additions

2. Transformations

3. Conversions

Although the breadth and depth of adaptive reuse varied between writers, the categories specified by various authors frequently (partially) coincide. The categorization demonstrates the breadth of the adaptive reuse field. Therefore, categorization is only one part of this academic method, and it is unlikely to be the most significant or impactful. Due to the fact that these projects often include a diverse range of architectural and conservational approaches, it might be difficult to get an adequate appreciation for the whole complexity and scope of these endeavors in a single phrase. Typically, these undertakings are the most stunning and inventive ones ever created. As a direct result of this fact, the development of the profession is dependent upon the publication of case study volumes. This is due to the fact that the variety and breadth of the whole project are laid bare via the analysis and presentation of case studies.

1.5.Approaching the Industrial Built Fabric by Technology

Some authors have approached the topic of building adaptation as if it were only a technical task, and as a result, their perspectives have become less theoretical. This is despite the fact that the design strategy is built on the relationship between the old and new forms. As a consequence of this, a number of "guidebooks" were written with the intention of explaining howto altera structure insuch a way that it may most effectively accommodate a newfunction. The book written by Highfield is the one that came first and is the most well known of its kind (Highfield, The rehabilitation and reuse of old buildings., 1987). The reuse of old materials and the renovation of dilapidated structures, In this book, Highfield investigates the adjustments that re used buildings need in terms of safety, energetical performance, dampness, condensation, and wood decay. He looks at these issues from a variety of perspectives. In addition to this, he provides a variety of technical case studies to back up these particular

33

difficulties. In subsequent editions of this reference guide, he updates outdated methodologies and has increased the number and variety of technical challenges that are to be examined by the designer who is modifying existing structures to include concerns regarding environmentally responsible redevelopment. In addition, he has broadened the scope of the technical issues that should be takenin considered by the designer (Highfield, The construction of new buildings behind historic facades., 1991)

1.6. Programmatic approach

The programmatic strategy is another adaptive reuse strategy that has been used in practice for some time but has not yet been fully explored in theoretical treatises. With this strategy, a certain purpose or program is chosen as the beginning point, and then an appropriate existing (old) building is sought for. In earlier research on this method, modern architecture and interventions have a tendency to take precedence over components of historical protection. (Powell, 1999). However, it is crucial to further expand this strategy, particularly in light of the fact that historic structures are being transformed for a variety of commercial uses, including retail, leisure, sport, care, and residential. Due to their "authentic character," historic buildings are often sought after by the developers of adaptive reuse projects. For instance, a building's "genuine character" mayaid in branddistinctiveness in the retail industry. Practicallyspeaking, the developers may discover ancient structures suited for retail outlets given that the structures that occupy city center shopping zones are often old (Bie Plevoets, Koenraad Van Cleempoel, 2019). If, as some of its proponents suggest, the programming approach to adaptive reuse may assist to solve not only practical functional problems but also reduce societal evils problems, then existing early research on the subject ought to be address these and other difficulties. Advocates of this strategy contend that in order to adequately address challenges like housing foranelderlypopulationwithinourcurrentbuildingstock,buildingsmustbeadaptedtodiverse programs.

1.7. Interior approach

Academics who do study on interior architecture have exhibited an increasing interest in the idea of adaptive re use over the course of the previous decade. This interest has been shown in

34

a number of different ways. Reusing old structures, interior architecture, interior design, and interiordecorationareallcloselyconnectedareasthatdeal,tovaryingdegrees,withtheprocess of turning a particular space into a use that is different from what it was originally intended for. It's conceivable that these are the crumbling ruins of an old structure, but they might also be the drawn out requirements for a new building that's being proposed (Graeme Brooker, Sally Stone, 204) They all place a significant amount of emphasis on the values, which include the establishment's intangible characteristics, atmosphere, and story, in addition to a more "poetic" approach to the rehabilitation of buildings. This is because they believe that these values are more important than the physical structure itself. Intangible aspects, atmosphere, and the overall story of the institution are included in these values. The article that Scott wrote in 2008 and titled "On Modifying Architecture" makes a direct analogy between the process of modifying architecture and the process of producing poetry. The essay is named "On Modifying Architecture." In addition to this, he investigates the concepts of empathy and generosity as a reaction to the process of modifying ancient structures to meet the requirements andsensitivityrequirementsofnewusers.Thisisdoneasareactiontotheprocessofmodifying ancient structures to meet the requirements and sensitivity requirements of new users. This "poetic" technique is a reflection of the fundamental idea presented in Machado's essay on palimpsest. Although there is a lot of opportunity for additional growth in this subject, this "poetic" approach is a reflection of the core thought (1976). Despite this, there remains a significant amount of space for more growth and improvement. It places a greater emphasis, not on the physical components of such creations or their material components, but rather on the "meaning" of the buildings themselves.

35

1.8.Intervention strategies

1.8.1. The concept of monument as a main strategy of preserving former industrial architecture. Palimpsest

There have been many suggestions for how to handle the stock of existing buildings, but they all come down to one of two strategies: treating them as monuments or seeing them as palimpsests.(Vecco,2010).Theterm"monument"nowencompassesawiderangeofindustrial architecture typologies and buildings, all of which may be used to demonstrate their historic, architectural, and cultural significance. In addition, the idea of a historic monument is always "fabricated," as defined by the things that a community choose to designate as memorials. (Riegel, 1903). The preservation and restoration of the built environment in its "full richness of authenticity" is required when it is regarded as a monument (ICOMOS, The Venice Charter, 1964). Regarding the reuse strategy, the Venice Charter stipulates:

“The conservation of monuments is always facilitated by making use of them for some socially useful purpose. Such use is therefore desirable but it must not change the lay out or decoration of the building. It is within these limits only those modifications demanded by a change of function should be envisaged and may be permitted” (ICOMOS, The Venice Charter, 1964)

Within this idea, reversibility has been proposed as a beneficial or even required concept in adapting ancient structures to modern wants and requirements. Reversibility is an intervention that may be entirely reversed to return a monument to its previous state (ICOMOS, Burra Charter, 2013). The bookshop in Maastricht, which is located in a historic former Dominican church, uses this strategy see Figure 1 3 Selexyz Dominicanen Bookstore. The two story high bookshelf that allows for the additional use is independent and can be taken down without harming the church's original construction.

36

The physical environment may also be seen as a palimpsest, in opposition to ecological ideas. A manuscript or other writing material that has had text scraped or wiped away so that it may be reused is referred to as a palimpsest. Over time, the original writing reemerge and many text layers may be seen. The amassing of material and intangible remnants of the past in historic urban settings has been described using the metaphor of the palimpsest (Bartolini, 2014). However, it has been used in the context of adaptive reuse on certain buildings and sites. (Machado, 1976). The concept of palimpsest is the outcome of a broad range of social and conceptual acts, and it serves as a tangible record of the past via the traces and representations they leave behind.

37

Figure 1.3 Selexyz Dominicanen Bookstore

Figure 1.4 The Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus, a Greek manuscript of the Bible from the 5th century, is a palimpsest

If the monument was made by a political or intellectual authority, the palimpsest is unaltered and hence genuine. (Bartolini, 2014) challenges the term's overuse and ensuing unclear meaning, as well as its influence in architectural and urban ideas. She argues that the chronological order of the layers is what makes a palimpsest unique, and that the metaphor should only be used to describe structures and places that show a chronological overlay of historical layers. She suggests the breccia metaphor as an alternative to the palimpsest:

“…a rock that consists of coarse deposits of sedimentary fragments from various origins that are consolidated or cemented together as a result of intense heating and pressure, such as along a fault wall or deposits from a volcano” (Bartolini, 2014)

Instead,shepresentstheconceptofbrecciation,orthemakingofbreccia,whichmaybeapplied to buildings and other structures constructed of elements with different origins that are not in

38

Figure 1.5 Caixa Forum Madrid, Herzog & De Meuron, Foto Simon Garcia

chronological order but nevertheless form a whole. This is analogous to the description of Rome as a city that was built from the blending of numerous layers of history, which have even grown to resemble a continuous composition in which, to the unobservant visitor, the various layers may become indistinguishable from one another. This is a city that was built from the blending of many layers of history. This is analogous to how Rome is described as a city that was constructed by the mixing of several different time periods into one another throughout its construction.

Regarding the hosted space as a palimpsest or breccia throughout the adaptive reuse process to enable many narratives to coexist. This suggests that a monument's prime may be still to come. This strategy deals with historical values in a less urgent and more inclusive fashion, which is not to say that it is fundamentally opposed to their preservation.

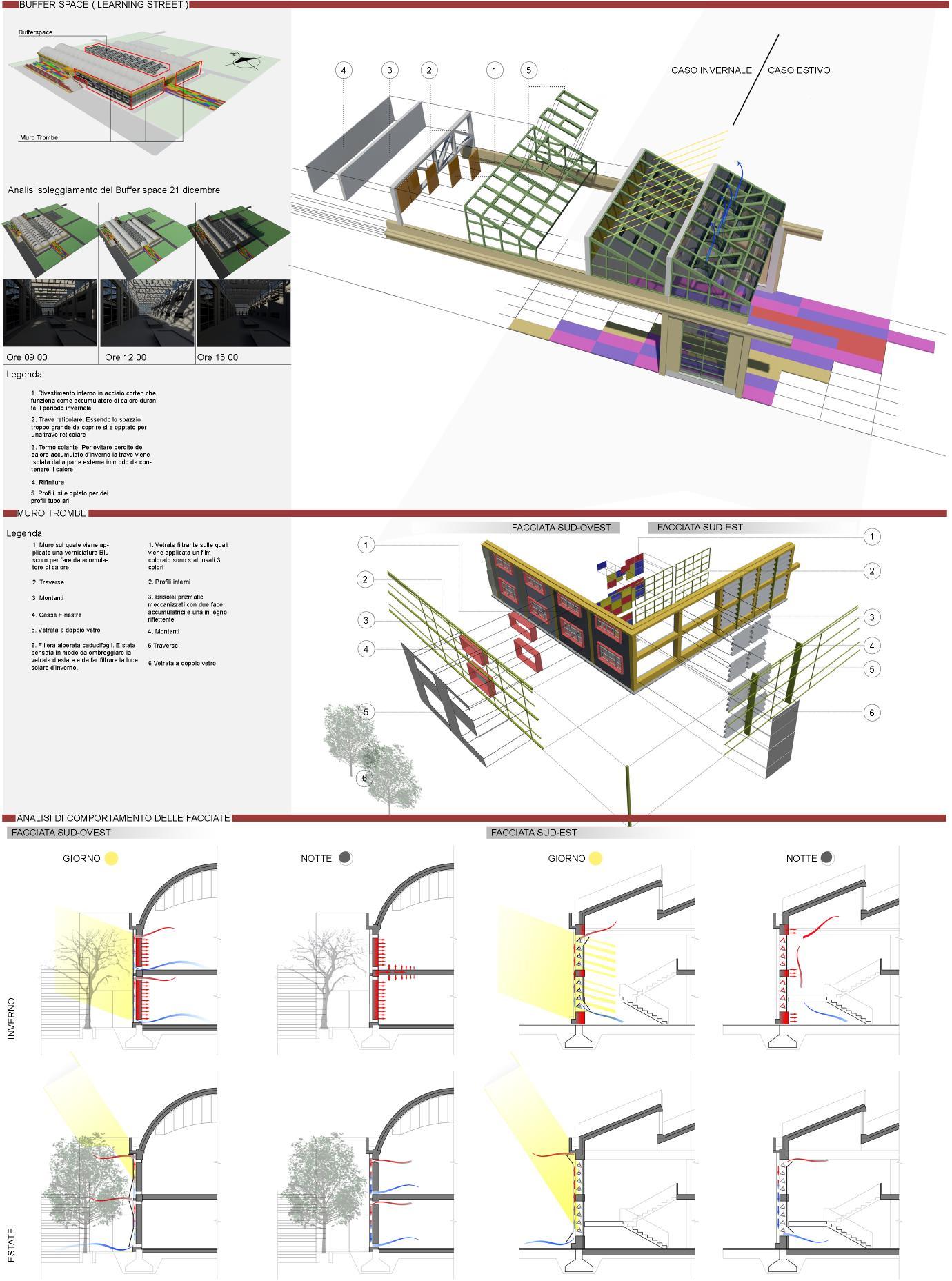

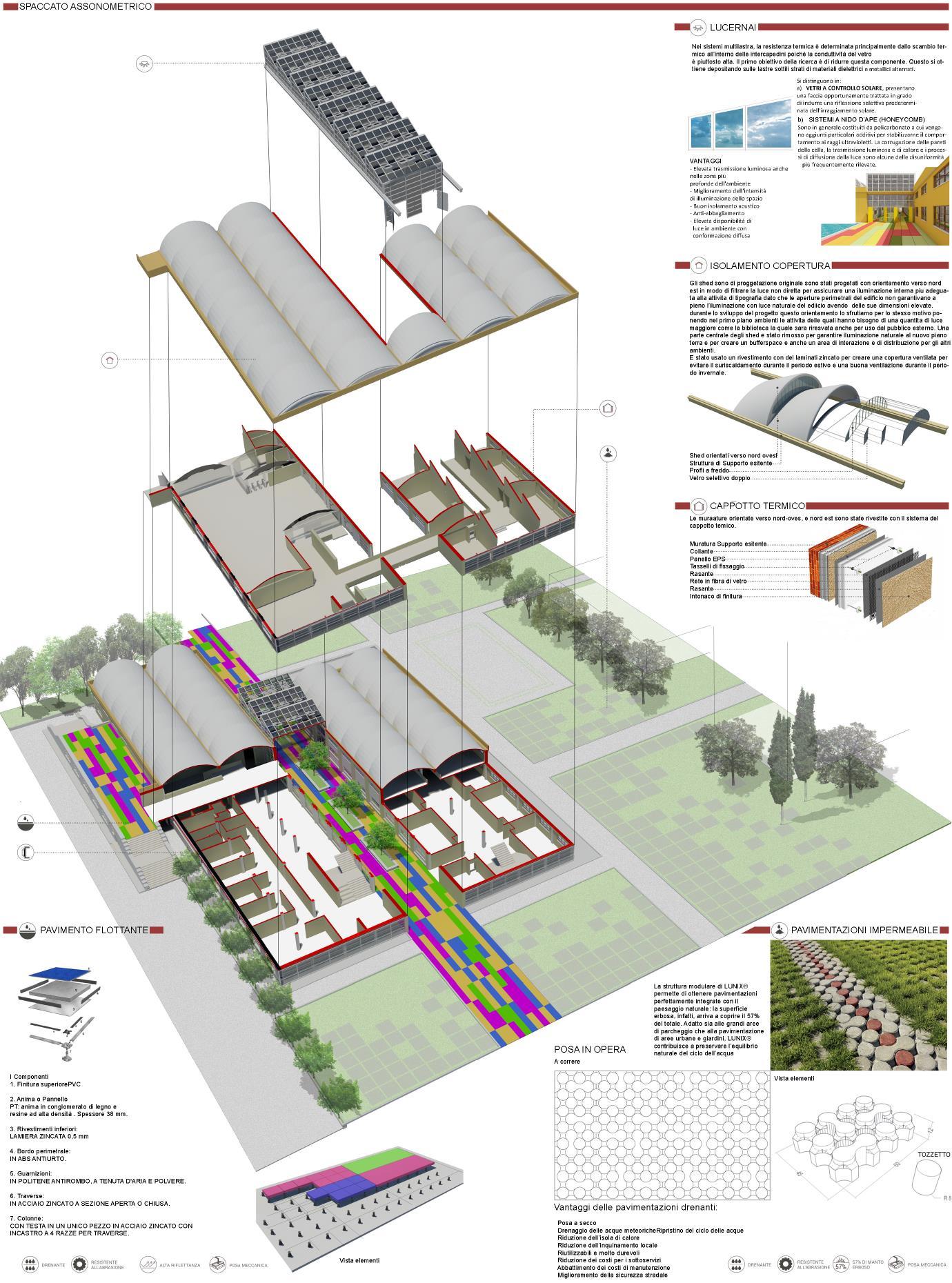

1.8.2. A classification into strategies