International Doctorate in Architecture and Urban Planning (IDAUP) International Consortium Agreement between University of Ferrara Department of Architecture (DA) and Polis University of Tirana (Albania) and with Associate members 2014 (teaching agreement) University of Malta / Faculty for the Built Environment; Slovak University of Technology (STU) / Institute of Management and University of Pécs / Pollack Mihály Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology.

Emel Petërçi IDAUP XXXIV Cycle

in

Constants of the Sacred Space

Architecture. A conceptual tool for identifying the sacred.

Constants of the Sacred Space in Architecture. A conceptual tool for identifying the sacred. Candidate: Emel Petërçi

POLIS

Supervisor: Dr. Sotir Dhamo DA Supervisor: Prof. Theo Zaffagnini

Cycle XXXIV

Constants of the Sacred Space in Architecture.

A conceptual tool for identifying the sacred.

PhD Candidate: Emel Petërçi

Home Institution: Polis University

Curriculum: Architecture (SSD ICAR 12 and ICAR14)

Research topic: 1.5 Cultural heritages. Innovations and ICT processes for cultural heritages use and conservation

Keywords: theory of architecture; constant; converted sacred space; cultural heritage; integrated survey;

Polis Supervisor: PhD Sotir Dhamo

DA Supervisor: Prof. Theo Zaffagnini

(Years 2018 2022)

1

Acknowledgements

The work presented in this thesis is the result of a collaboration between Polis University and Ferrara University. This collaboration offered a unique framework for the research presented in this thesis, allowing me to take advantage of the expertise of the professors of these two institutions.

There are no words to express my sincere appreciation and respect for my research advisor., Dr. Sotir Dhamo, for his continuous encouragement for my Ph.D. studies and related research, as well as his understanding, enthusiasm, and extensive knowledge He has motivated me to become an independent researcher and has shown me the value of critical thinking. His advice guided me through all of my thesis research and writing.

I would like to thank Prof.Nicola Marzot, my co DA advisor at the University of Ferrara, for his interesting comments and recommendations.

Besides my advisors, I would like to thank the Academic Board, especially Prof. Besnik Aliaj, Prof. Skender Luarasi, and Dr. Llazar Kumaraku, for their thoughtful suggestions and encouragement, but also for the challenging questions that pushed me to broaden my research from multiple perspectives. I would also like to thank the programmer coordinator Prof. Roberto Di Giulio, Prof. Theo Zaffagnini and Dr. Ledian Bregasi.

I will never forget the friends that helped me through difficult times, cheered me on, and celebrated each accomplishment.: Dr. Gerdi Papa, Dr. Kejt Dhrami, and Dr. Amanda Terpo.

And my biggest thanks to my family for all the support they have shown me through this research, the culmination of four years of studies and distance learning. To my father for teaching me to be patience and always remanding me the goal, and to my mother all the help and support she has given me during this period.

To my son Enes, who was born during this study period and who has served as my motivation to finish this journey. I'd like to thank my husband, Ervis, for all of the emotional support and understanding he has given me, without which I would have given up a long time ago

This thesis is dedicated to my father, mother, Enes and Ervis!

Thank you all!

2

Constants of the Sacred Space in Architecture. A conceptual tool for identifying the sacred.

This study is a reflection of how we perceive sacred spaces, how we define sacred, and how we examinesacred when theseplaces areconverted intoanother religion. Sacred places have always shown an extraordinary interest in human throughout their histories. And in most cases, the features that are ascribed to the sanctuaries tend to be basic and more descriptive of the architectural components that make up the sanctuaries without going into any additional detail. Related to this, the research consists of an effort to investigate what elements remain the same while reading about and experiencing converted sacred spaces.

From the formulation of primitive’s hut to the meaning of type or, finally, the documentation of objects with integrated surveying methods to the retrieval of lost objects through virtual reality, humans have always sought to make sense of everything they build. This also includes the ability to retrieve lost objects through the use of virtual reality. After gaining an understanding of the connection what constants have with type and archetype, the research makes inferences about how to describe their semantics. This method of investigation views "constants" not just as an aspect of form but also as further developments towards the fundamental "concepts" of what they imply and how they are experienced.

In conclusion, in the same manner that Rossi studies the city, these "constants" are studied against the context of sacred spaces. The first step, it is done in the process of finding the constants of the sacred space exactly for the spaces of the two most important religions, such as the church and the mosque, and to analyze their characteristics. After discovering the constants of sacred spaces in general, the next step is to discover the constants of converted sacred spaces. The "soul" of a space can be found through the process of converting a sacred space from one religion to another. Precisely this is the other purpose of this study, to find out what are the constants that remain perceptible during the conversion.

The study examines a variety of case studies to get an understanding of the processes involved in transforming sacred spaces. However, the instance of Albania serves as the primaryfocus of this investigation, inorder toget an understandingof theconstants that have survived the conversion. This thesis is limited to looking at instances of churches being converted into mosques during the time of Ottoman rule, which lasted from the 14th to the beginning of 20th century. This restriction is made because the subject topic is so wide. Following the documentation of the altered locations in Albania, two case studies were chosen as the only ones to have survived the multiple historical shifts across time. As a result of the challenges involved in tracking down the historical data and the absence of

3 Abstract

English

unambiguous documentation relating to the two buildings that were the subject of this study, digital and technological techniques have been implemented for the documentation and, potentially, the retrieval of lost constants. The study makes use of a variety of research approaches, including quantitative and qualitative analyses of survey data, as well as graphical examinations of individual case studies.

Because there are many stages of conversion, the methodology that was used in both cases in Albania consisted of using an integrated survey and the realization of hypothetical images of thespaces takeninthestudyduringthedefinedperiodsof conversion,based onthelimited photographicdatathatwas available.Theconceptualtoolof constantsis usedfortheanalysis of the Albanian converted sacred space.

Keywords: theory of architecture; constant; converted sacred space; cultural heritage; integrated survey;

4

Abstract Albanian

Konstantet e hapësirës së shenjtë në arkitekturë. Një mjet konceptual për identifikimin e të shenjtës.

Kykërkimështënjërefleksionsesii mendojmëvendeteshenjta,siepërcaktojmëtëshenjtën dhe se si e analizojmë të shenjtën kur këto vende konvertohen. Vendet e shenjta përgjatë historisësëtyre,shfaqininterestëjashtëzakonshëmpërnjeriun,dhezakonishtkarakteristikat që jipen për vendet e shenjta tentojnë të jenë simplifikuese dhe më shumë përshkruese të elementeve arkitektonik përbërës pa u thelluar më tej. Në këtë pikë, kërkimi është një tentativë të explorojë se cilat janë “konstantet” në leximin dhe përjetimin e hapësirave të shenjta të konvertuara. Njeriu gjithmonë ka kërkuar ti japi kuptim çdo gjëjë që ndërton, nga formulimi i primitve hut deri tek kuptimi i tipit apo së fundmi dokumentimi i objekteve me metodat e rilevimit të integruar e deri te rikthmimi i objekteve të humbura përmes virtual reality.

Duke kuptuar lidhjen që kanë konstantet me tipin dhe arketipin, arrihet të nxirren konkluzione në shpjegimin e terminologjisë së tyre. Ky kërkim i shikon “konstantet” jo vetëm si një atribut i formës, por avancon më tej drejt “konceptit” themelore të kuptimit dhe përjetimit të “konstanteve” Sipërfundimkëto“konstante”analizohennënsfondinehapësiravetëshenjtanjësojsiç Rossi analizon qytetin. Analiza e parë që bëhet është gjetja e “konstanteve” të hapësirës së shenjtë pikërisht për hapësirat e dy feve kryesore si kisha dhe xhami. Pas gjetjes në mënyrë të përgjithshme të “konstanteve” të hapësirave tëë shenjta, hapi tjetër është gjetja e “konstanteve” për hapësirat e shenjta të konvertuara, pasi pikërisht në konvertimin e hapësirave nga njëra fe në tjetrën qëndron “shpirti” I hapësirës. Qëllimi i këtij kërkimi është të kuptoj se cilat janë ato “konstante” që gjatë konvertimit mbetën të përjetueshme. Kërkimi shikon raste studimore të ndryshme, për të kuptuar mënyrat e konvertimit të hapësirave të shenjta. Por fokusi i këtij studimi do të jetë rasti I Shqipërisë, për të kuptuar se cilat janë ato “konstante” të cilat kanë mbetur nga konvertimit. Për shkak të fushës së gjërë të kërkimit, ky studim fokusohet vetëm në rastet e konvertimit nga kisha në xhami për periudhën e pushtimit osman të shekullit nga 14 deri ne fillim te shekullit 20. Pasi bëhet dokumentimi i hapësirave të konvertuara për Shqipërinë, përzgjidhen dy raste studimore si të vetmet që i kanë mbijetuar ndryshimeve të shumta historike. Vështirësitë në gjetjen e të dhënave historike dhe mos pasja e dokumentive të qarta për dy objektet e marra në studim, ka sjell përdorimin e mënyrave dixhitale dhe teknologjike për dokumentimin dhe rikthimin hipotetik të “konstanteve” të humbura. Studimi përdor një shumëllojshmëri qasjesh

5

kërkimore, duke përfshirë analizat sasiore dhe cilësore të të dhënave të anketës, si dhe ekzaminimet grafike të rasteve studimore individuale.

Përshkaktëfazavetëshumtatëkonvertimit, metodologjiaqëpërdoret në dyrastetshqipëtare është përdorimi i rilevimit të integruar dhe realizimit të imazheve hipotetike të hapësirave të marra në studim në periudhat e përcaktuara të konvertimit, duke u bazuar në ato pak të dhena fotografike. Si përfundim, mjeti konceptual i “konstanteve” përdoret për analizimin e hapësirës shenjtë të konvertuar shqiptare.

Fjalë kyçe: teoria e arkitekturës; konstante; hapësirë e shenjtë e konvertuar; trashegimi kulturore; sondazh i integruar;

6

Abstract in Italian

Costanti dello spazio sacro in architettura. Uno strumento concettuale per identificare il sacro.

Questa ricerca studia il modo in cui percepiamo gli spazi sacri, come definiamo sacro ecome esaminiamo il sacro quando questi luoghi vengono convertiti in un'altra religione. I luoghi sacri hanno sempre mostrato uno straordinario interesse per gli uomini nel corso della loro storia. E nella maggior parte dei casi, le caratteristiche che vengono attribuite al spazi sacri, tendonoadesserebasilariepiùdescrittivedellecomponentiarchitettonichechecompongono il sacro senza entrare in alcun dettaglio aggiuntivo. In relazione a questo, la ricerca consiste in uno sforzo per indagare quali elementi rimangono “costanti” durante la lettura e l'esperienza degli spazi sacri convertiti.

Dalla formulazione della primitive hut al significato di tipo o, infine, dalla documentazione di oggetti con metodi di rilevamento integrati al recupero di oggetti perduti attraverso la realtà virtuale, l'uomo ha sempre cercato di dare un senso a tutto ciò che costruisce. Ciò include la possibilità di recuperare oggetti persi attraverso l'uso della realtà virtuale. Dopo aver acquisito una comprensione della connessione che le “costanti” hanno con il tipo e l'archetipo, la ricerca fa inferenze su come descrivere la loro semantica. Questo metodo di indagine vede le "costanti" non solo come un aspetto della forma, ma anche come ulteriori sviluppi verso il "concetto" fondamentale di ciò che implicano e di come vengono vissuti. In conclusione, allo stesso modo in cui Rossi legge la città, queste "costanti" sono studiate nelcontestodeglispazisacri. Ilprimopassonelprocessodiricercadellecostantidellospazio sacro proprio per gli spazi delle due religioni più importanti, come la chiesa e la moschea, è l'analisi delle caratteristiche. Dopo aver scoperto le costanti degli spazi sacri in generale, il passo successivo è scoprire le costanti degli spazi sacri convertiti. L '"anima" di uno spazio sacro può essere trovata attraverso il processo di conversione di uno spazio sacro da una religione all'altra. Lo scopo di questa ricerca è scoprire quali sono le “costanti” che rimangono esperienziali durante la conversione. Lo studio esamina una varietà di casi di studio per ottenere una comprensione dei processi coinvolti nella trasformazione degli spazi sacri. Tuttavia, l'istanza dell'Albania servirà come obiettivo principale di questa indagine al fine di comprendere le “costanti” che sono sopravvissute alla conversione. Questo studio si limita a esaminare i casi di chiese convertite in moschee durante il periodo dell'occupazione ottomana, che durò dal XIV al inizio del XX secolo. Questo perché l'argomento è così ampio. A seguito della documentazione delle località alterate in Albania, sono stati scelti due casi di studio come gli unici sopravvissuti ai molteplici cambiamenti storici nel tempo. A seguito delle sfide legate alla ricerca dei dati storici edell'assenza di documentazione univoca relativa ai dueoggetti chesonostati oggetto

7

di questo studio, sono state implementate tecniche digitali e tecnologiche per la documentazione e, potenzialmente, il recupero di “costanti” perduti. Lo studio si avvale di una varietà di approcci di ricerca, comprese analisi quantitative e qualitative dei dati dell'indagine, nonché esami grafici di singoli casi di studio.

Poiché ci sono molte fasi di conversione, la metodologia utilizzata in entrambi i casi in Albania è consistita nell'utilizzo di un rilievo integrato e nella realizzazione di immagini ipotetiche degli spazi presi nello studio durante i periodi di conversione definiti, sulla base dei limitati dati fotografici che era disponibile. Lo strumento concettuale delle “costanti” viene utilizzato per l'analisi dello spazio sacro convertito albanese

Parole chiave: teoria dell'architettura; costante; spazio sacro convertito; eredità culturale; indagine integrata;

8

9 Table of Contents Acknowledgements..........................................................................................................2 Abstract English................................................................................................................3 List of Figures ....................................................................................................................13 List of Tables.....................................................................................................................20 C h a p t e r 1....................................................................................................................22 Introduction ............................................................................................................................22 1.1 Research background.............................................................................22 1.2 Statement of the problem.......................................................................24 1.3 State of Art............................................................................................... 25 1.4 Methodology 31 1.5 Research Problems and limitation......................................................... 36 1.6 Research Questions 37 1.7 Purpose of the study................................................................................38 1.8 Expected results of this research 39 1.9 Significance of Study and Stakeholders................................................41 1.10 Chapter overview 43 C h a p t e r 2 46 PART ONE THEORETICAL ISSUES INCLUDED IN THE PROCESS OF FINDING CONSTANTS IN THE ARCHITECTURAL MODEL OF SACRED SPACES.............................................................................................................................46 Theoretical Framework 46 2.1. Introduction............................................................................................. 47 2.2. Type and Typology 48 2.3. Type as constant......................................................................................51 2.3.1. Meaning of Constants 54 2.3.2. Constant as an “idea”.......................................................................54 2.3.3. Constant as form 55 2.3.4. Understanding the link between constant and archetype ..................60 2.3.5. Conclusion 62 2.4. The Anatomy of Church and Mosque 63 2.4.1. Element of Church Architecture ........................................................63 2.4.2. Elements of Mosque Architecture 73

2.4.3. Conclusions........................................................................................83

C h a p t e r 3...................................................................................................................86

The "Sacred Space" Religion scape.........................................................................................86

3.1. The importance of Religion ....................................................................87

3.3. Historic evolution of meaning of sacred space 90

3.4. The phenomenology of sacred space .....................................................93

3.5. The Exploration of Sacred Space Constants 96

3.6. Spatial organization of the prayer space in the Two Monotheist

Religious 101

3.6.1. The space of worship .......................................................................101

3.6.2. The sacred architectural space in the religious experience 102

3.6.3. Exploring The Constants of Sacred Space in Islamic Architecture.102 3.6.4. Exploring The Constants of Sacred Space in Christian Architecture 108

C h a p t e r 4................................................................................................................ 113

The idea of Conversion ........................................................................................................ 113 4.1. Definition of term “conversion” ........................................................... 114 4.2. Meaning of Conversion.........................................................................114 4.3. Conversion of buildings as “an extraordinary quality of form” ......116

4.4. Architectural Conversions Factors 118 4.3.1. Conclusion .......................................................................................120

C h a p t e r 5 123 PART TWO EMPIRICAL RESEARCH PRECEDENTS INCLUDED INTHE EXPLORATION PROCESS, DIGITAL MODELS AND VIRTUAL FRUITIONS 123

Mapping Christianity and Islam in the West Balkans 123 5.1. Introduction 124 5.2. Religious in the Mediterranean Sea and the Ottoman Empire ........127 5.3. Religion in Albania 130

5.3.1. The establishment of the Christian religion in Albania................131 5.3.2. Ecclesiastical organization and Islamization of Albania 132 5.3.3. “The right to religion and religious tolerance”.............................134

5.4. Mapping Christianity and Islam in the West Balkans 136

10

5.5. Political background discourses in Albania........................................139

5.6. Interpretation of sacred spaces in modern times............................... 144

5.7. Ottoman Architecture in the 15th -20th century and its Effects on the Converted Sacred Spaces................................................................................144

5.8. Ottoman Advocacy................................................................................148

5.9. Cases of converted sacred space in Italy.............................................149

5.10. Modern day Restoration Process of Church Mosque 154

C h a p t e r 6................................................................................................................ 156

The digital revolution in cultural heritage: the innovation of systems and procedures for cataloging, recording and representing reality 156

6.1 Historical evolution of the concept of cultural heritage ....................157

6.2 Integrated survey methodologies and digital models 159

6.3 Methodology of survey..........................................................................161

6.4 Legislation on digitalization of cultural heritage 163

C h a p t e r 7 168

PART THREE - APPLICATION CASE 168

7.1 Case studies of Converted Sacred Spaces 169

7.1.1. The case of conversion of Churches to Mosques in Istanbul...........171 7.1.2. Some word about Saint Sophia Church-Mosque-Museum-Mosque 175

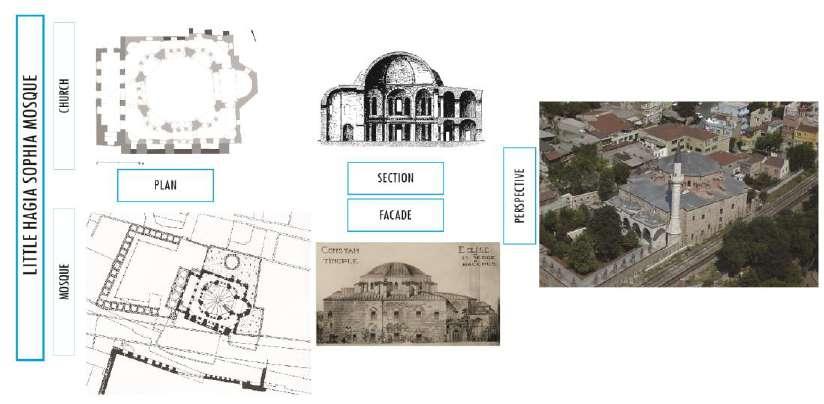

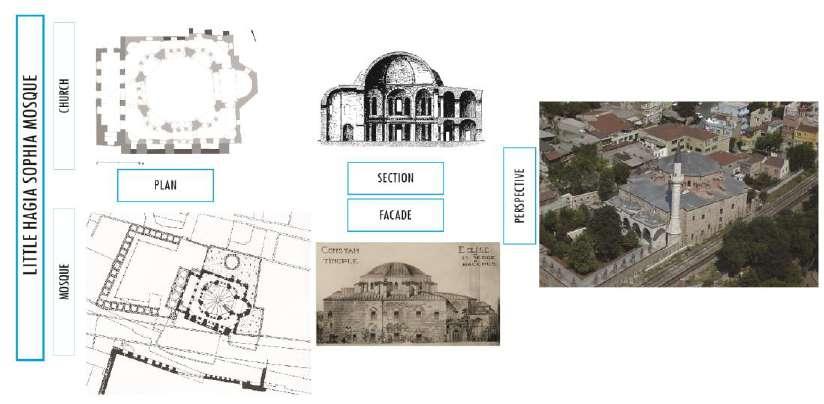

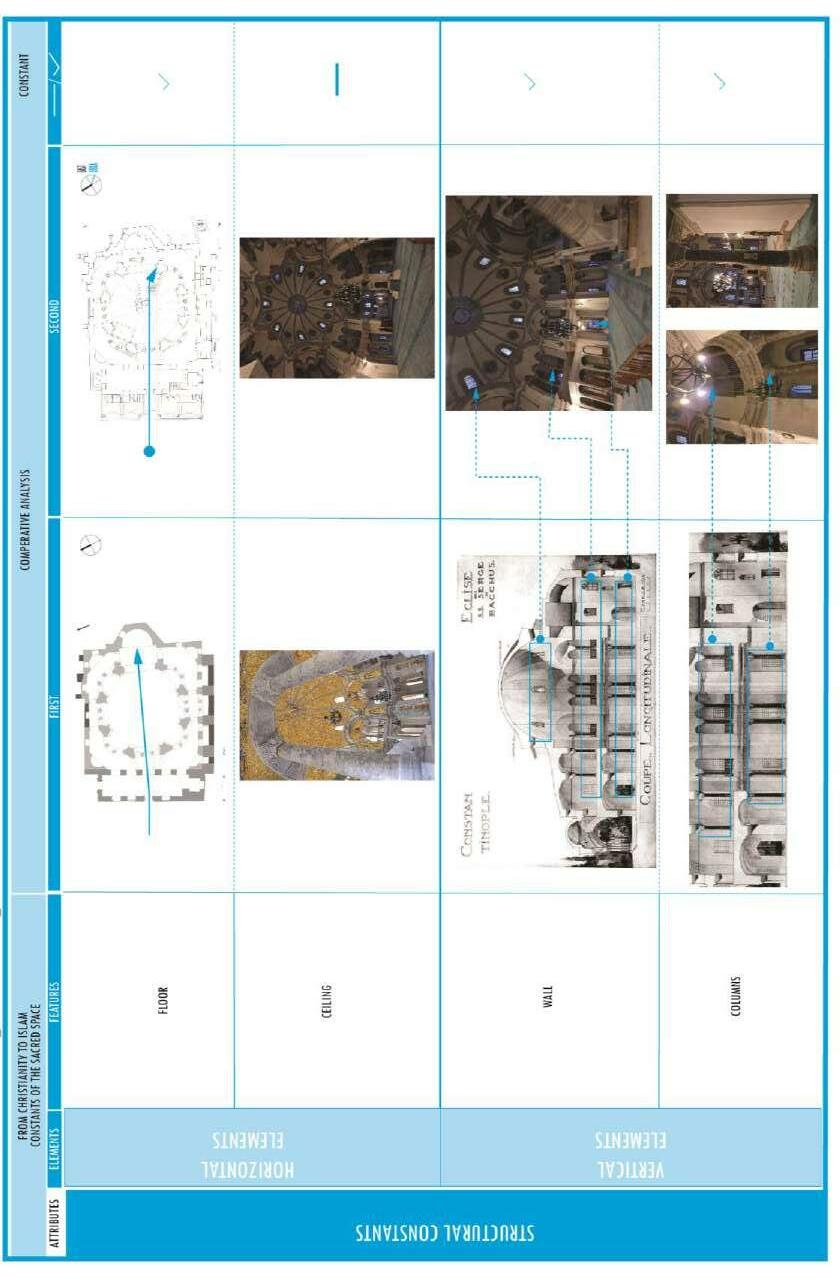

7.1.3. The case of Little Hagia Sophia Mosque 180

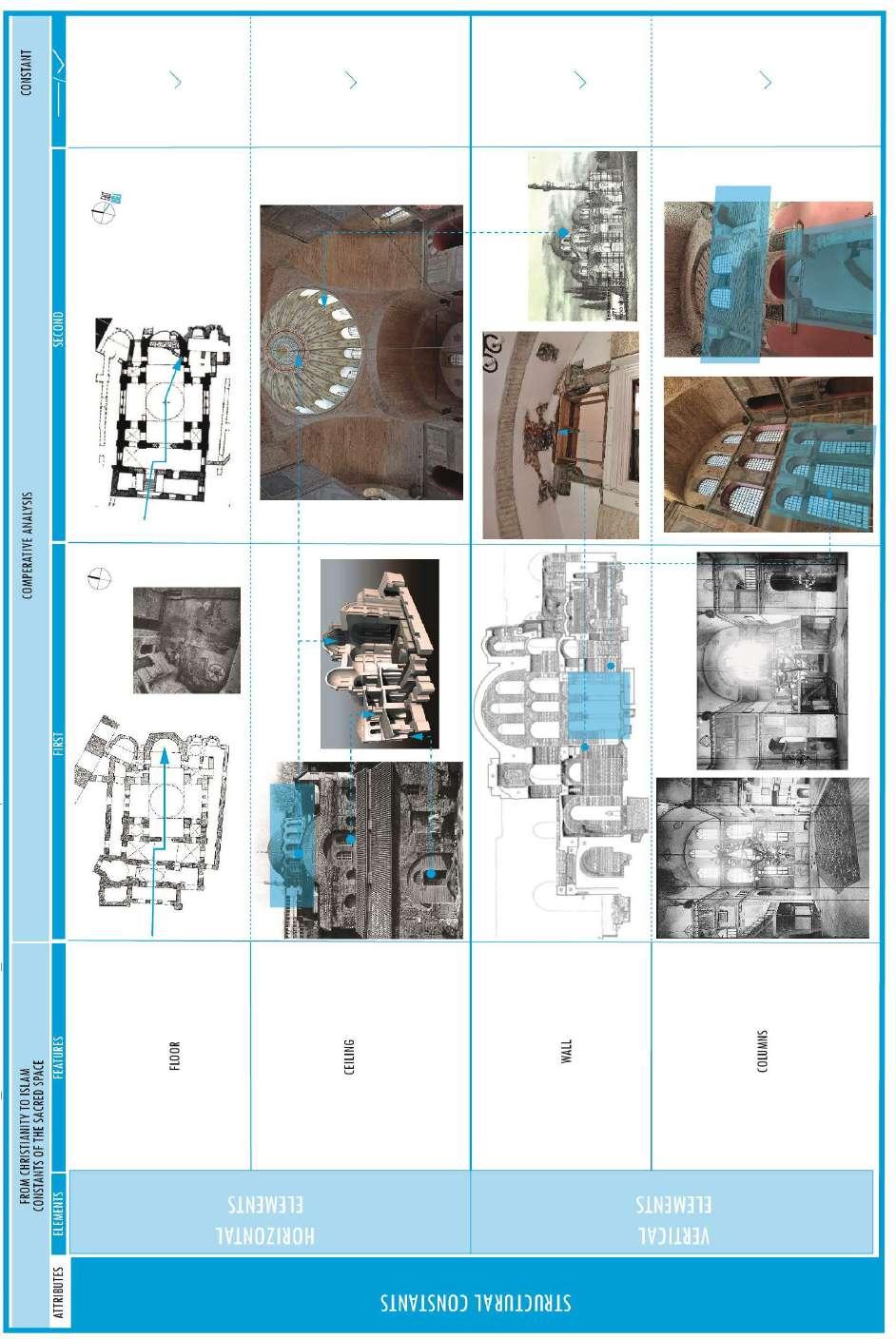

7.1.4. The Case of Kalenderhane Mosque .............................................186

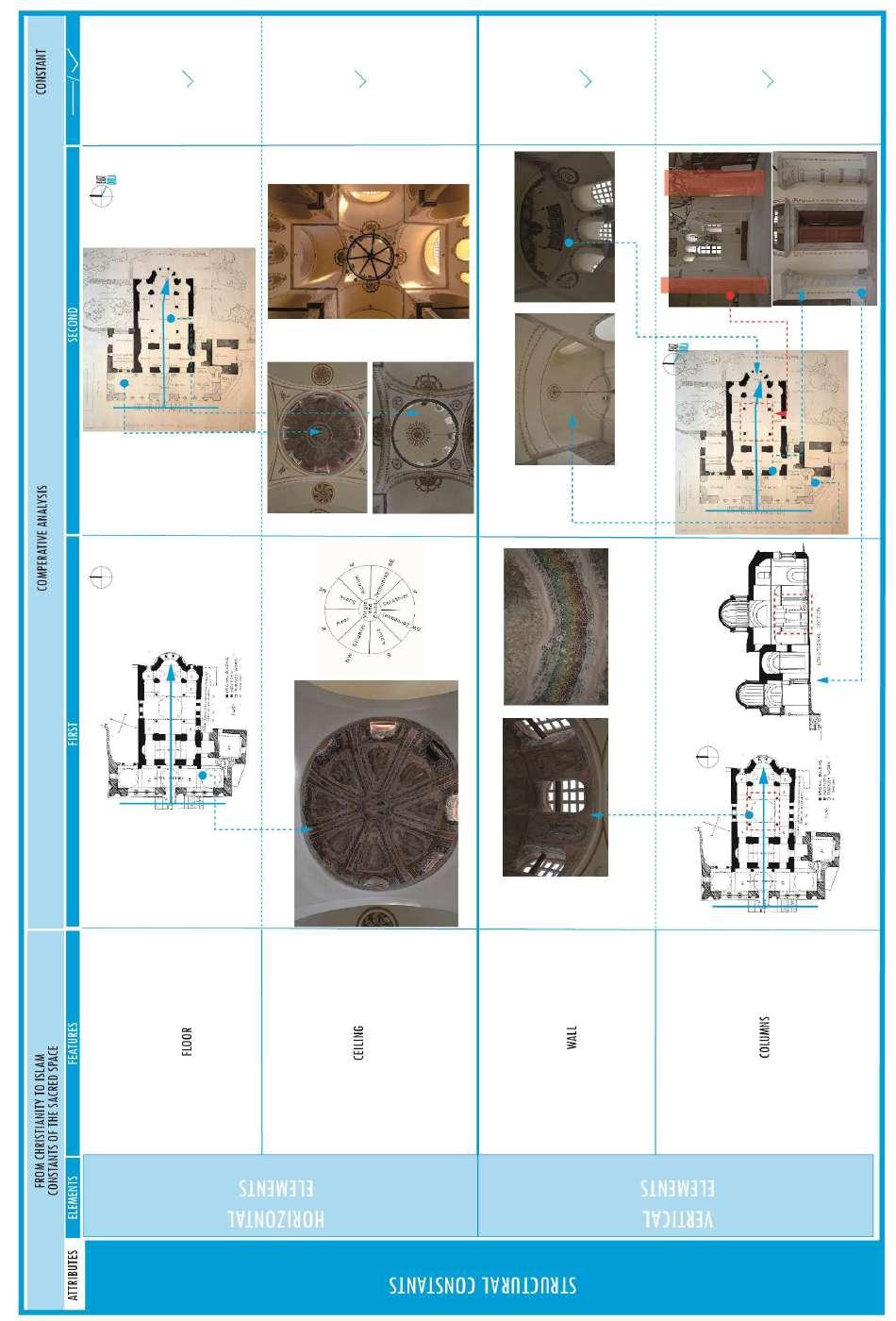

7.1.5. The case of Zayrek Mosque 191

7.1.6. The case of Bodrum Mosque ........................................................198

7.1.7 The Case of Church-Mosque of Vefa 207

7.2 The Applicative case of Albania .......................................................... 212

7.2.1. General introduction to the case of Albania 212

7.2.2. Selecting the cases..............................................................................214

7.3 Data collection for cases of mosques built on the ruins of churches 216

7.4 The case of church converted into mosque in Albania Saint Stephen Church / Fatih Mosque ...................................................................................229

11

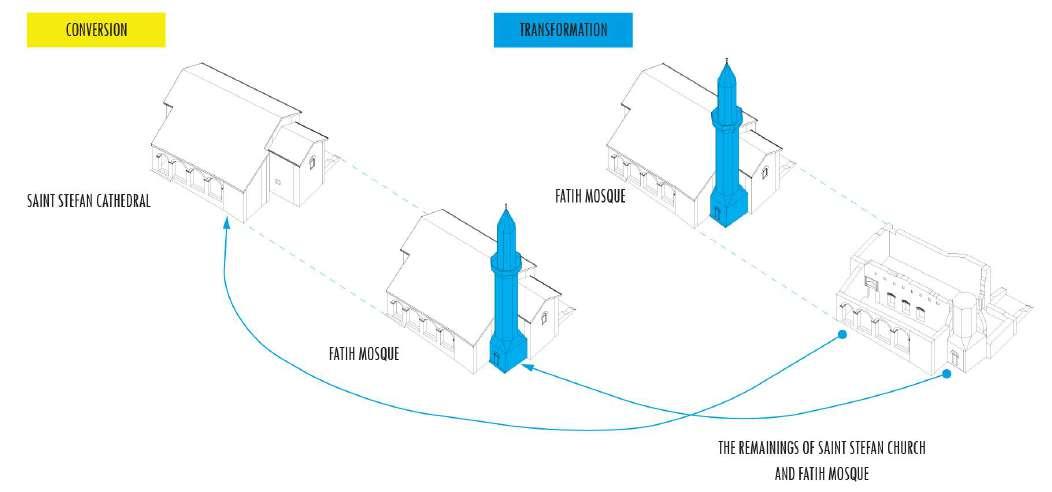

7.4.1. Historical information .....................................................................229

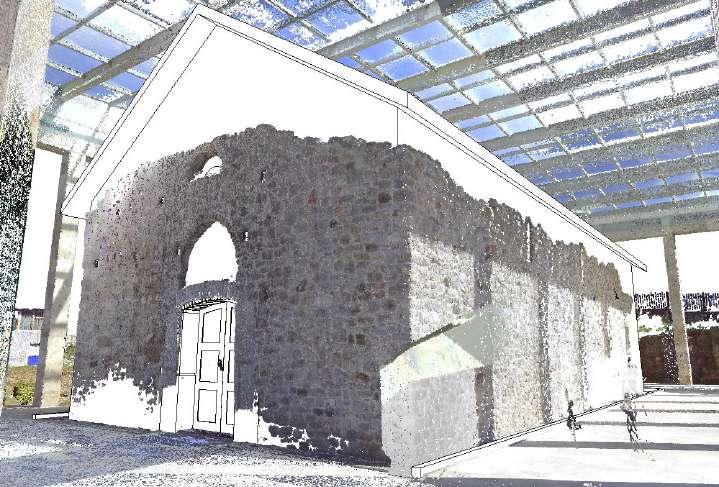

7.4.2. Architectural evolution of the monument ........................................232

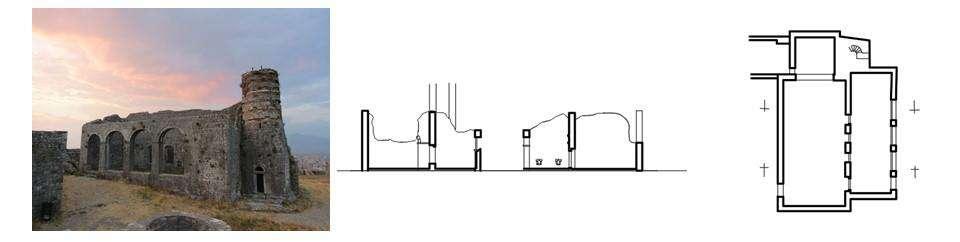

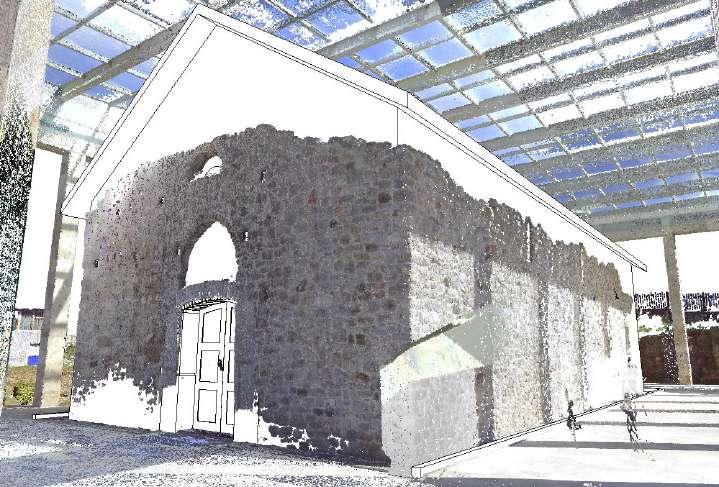

7.4.3. The architectural survey of the church mosque of Shkodra ............235

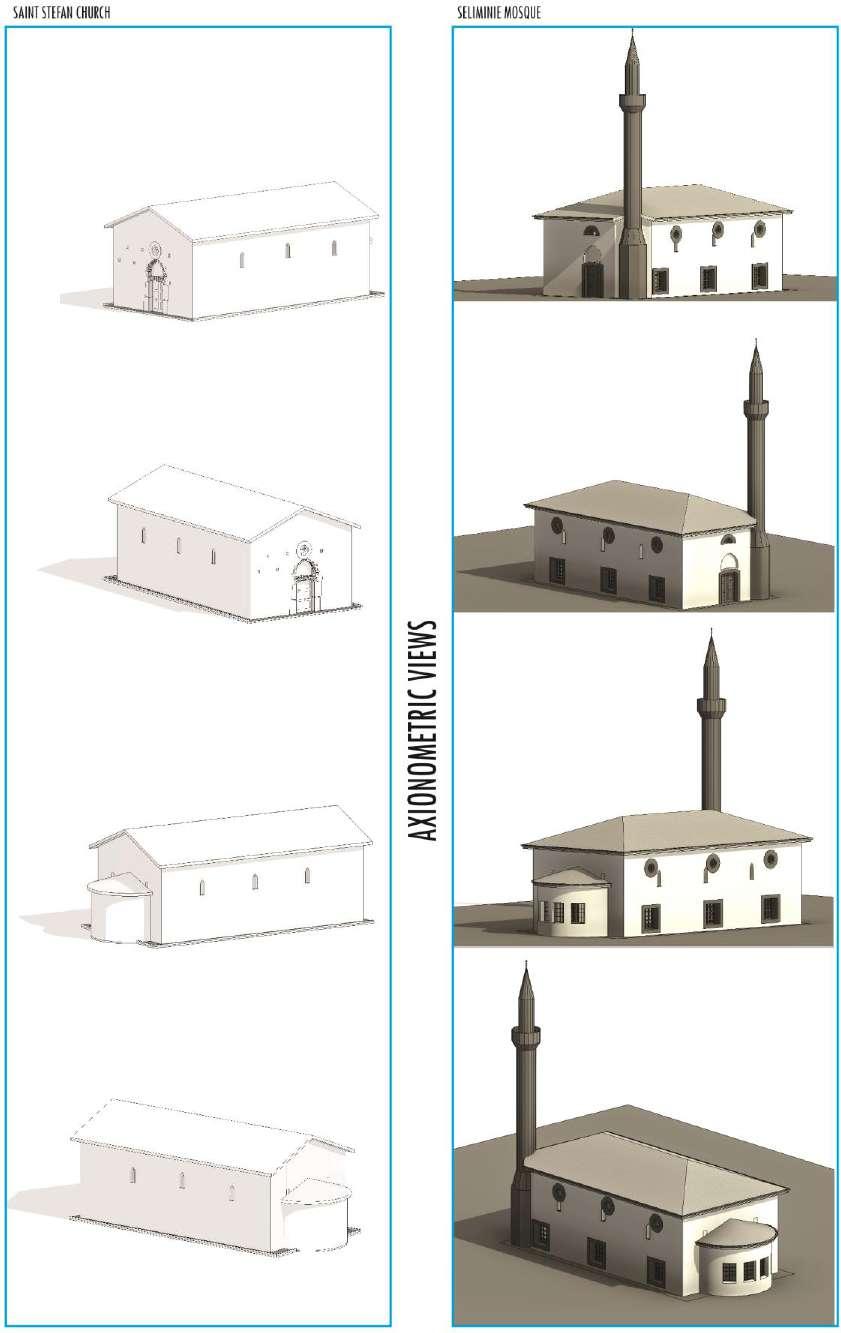

7.4.4. The three dimensional hypothetical reconstruction of the Monument 239

7.4.5. The description of constants of architecture in the sacred space....240

7.5 The case of Church Mosque in Lezha 245

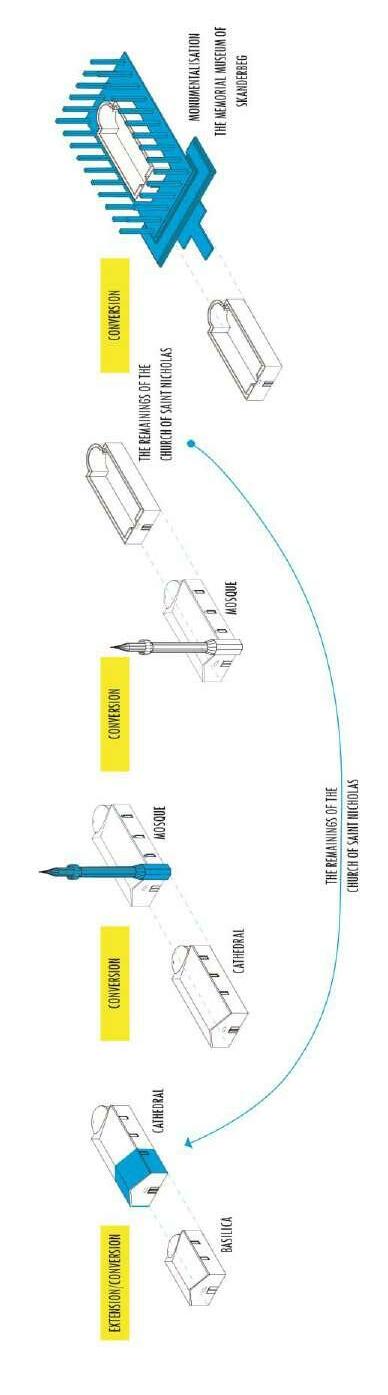

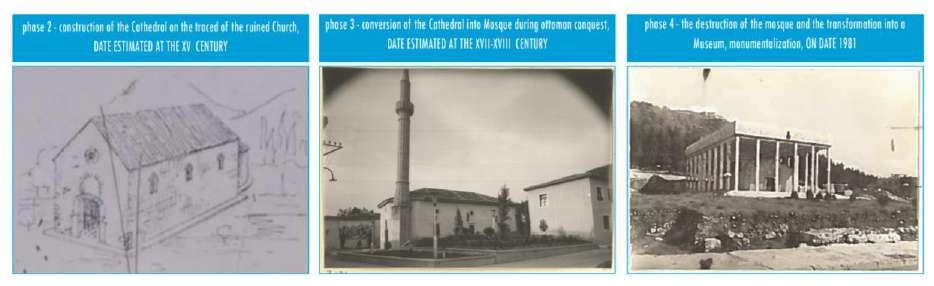

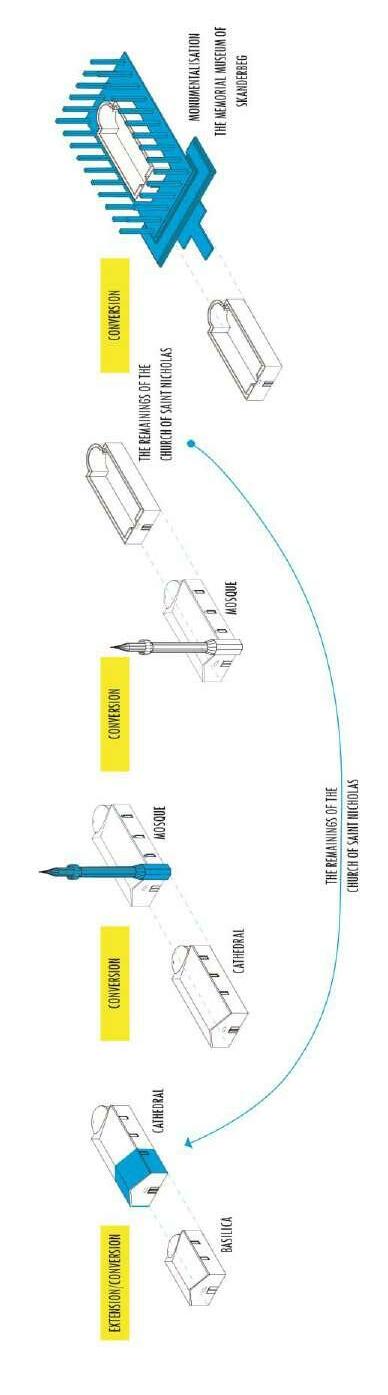

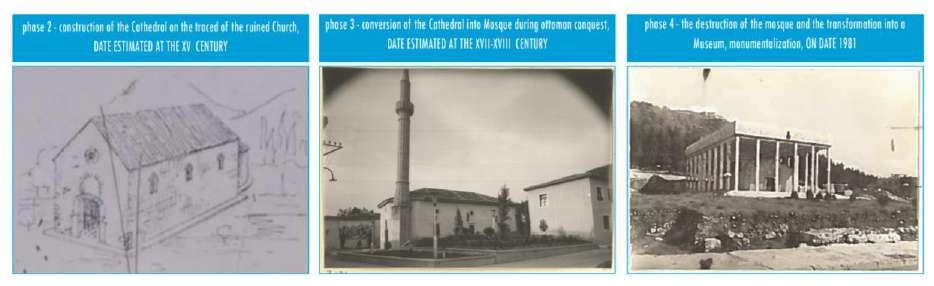

7.5.1. First as the Church of Saint Nicholas, then as the Mosque of Selimiye, and last as the Memorial of National Hero Skanderbeg. 247

7.5.2. The significant role that the monument played in the past ..............249

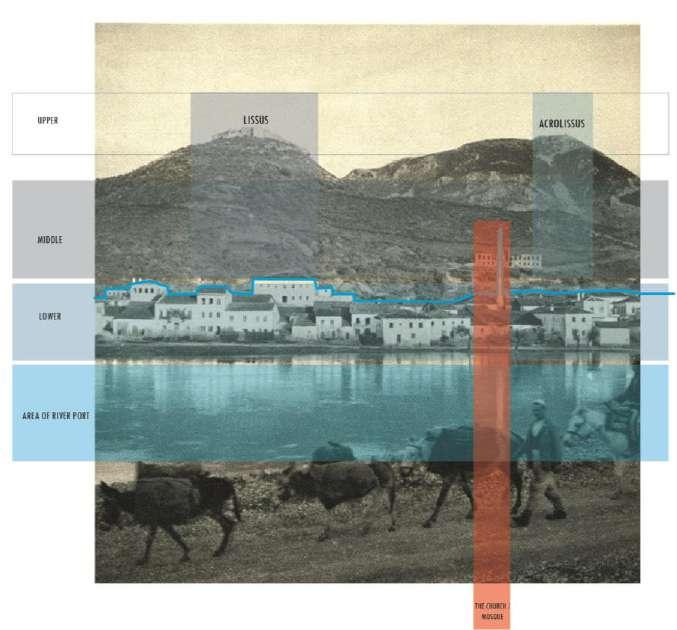

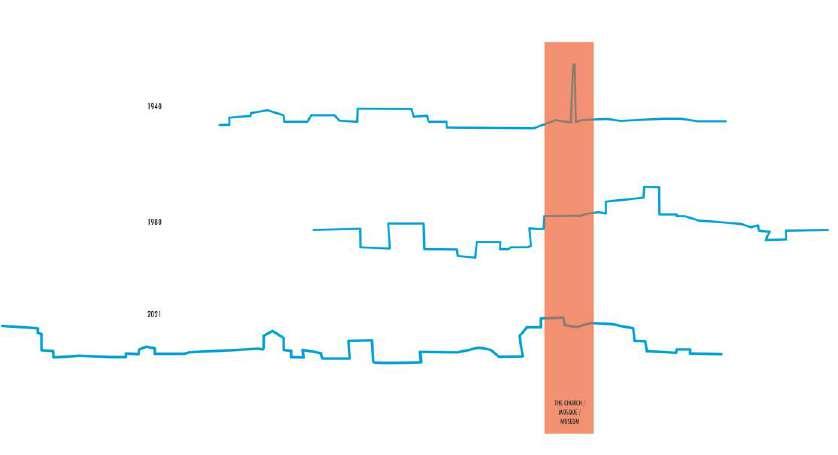

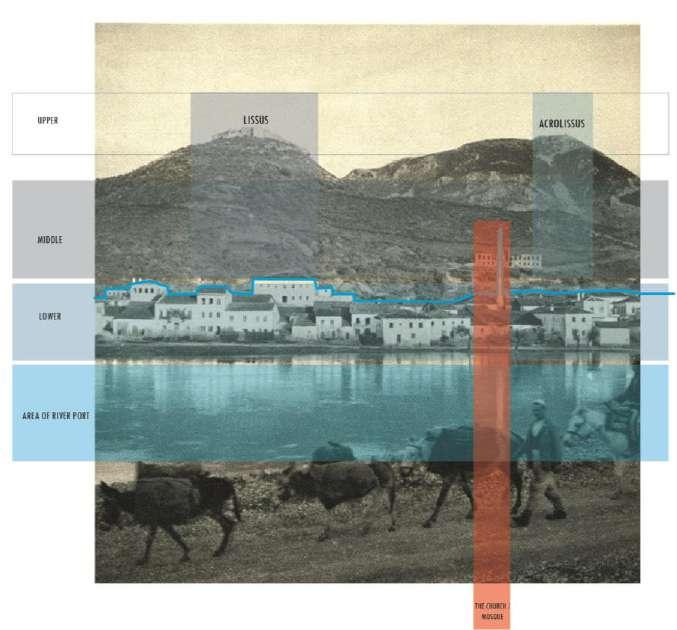

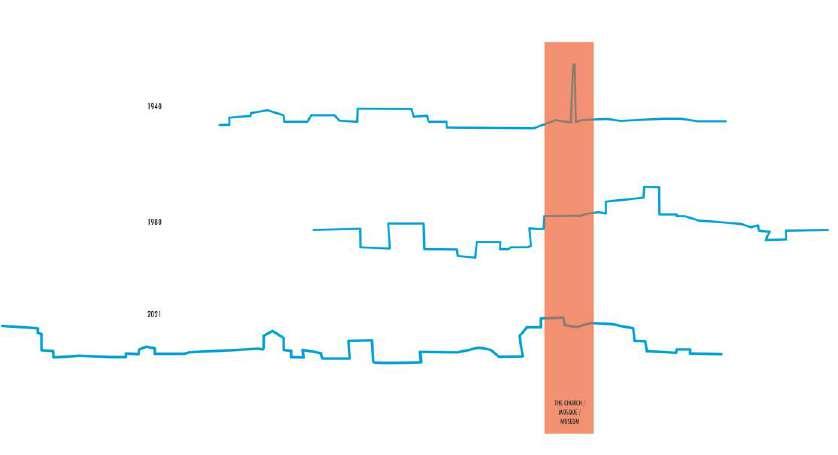

7.5.3. Layering the historical views of the object under study in relation to the city 249

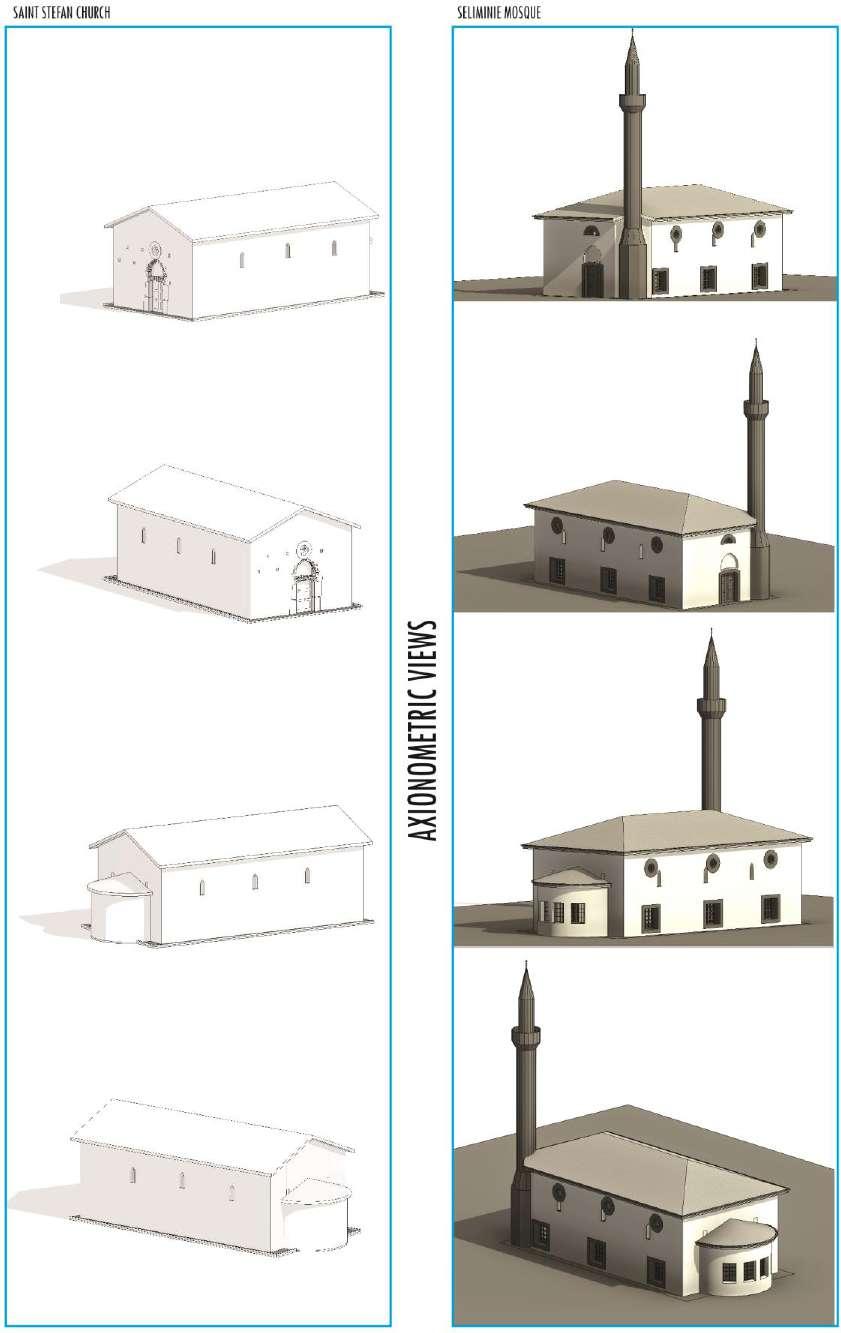

7.5.4. The development of architectural object 252

7.5.5. The architectural assessment of the Memorial of the National Hero Skanderbeg, located in Lezha. .......................................................................255

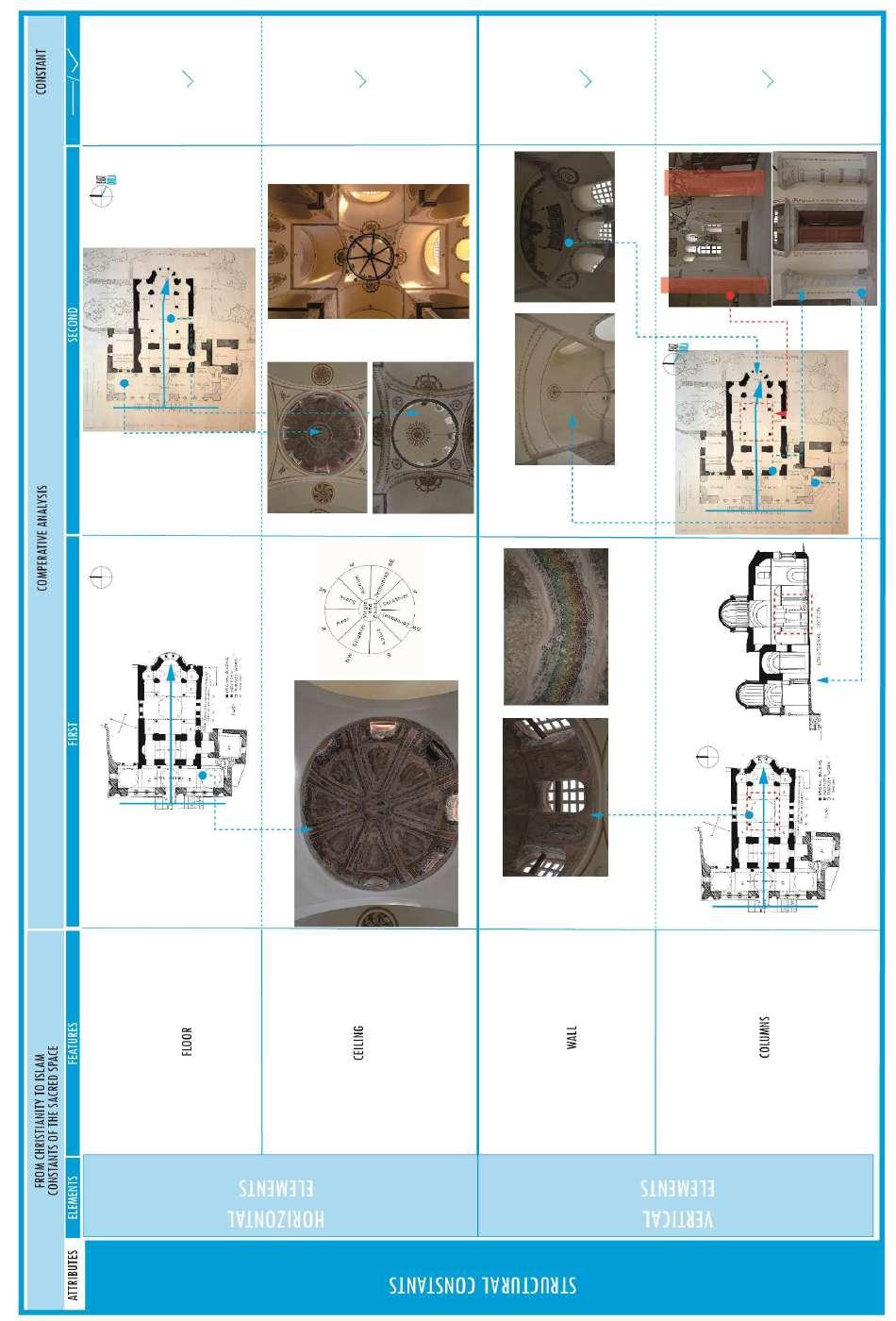

7.5.6. The three dimensional reconstruction of the monument 260 7.5.7. The description of constants of sacred space for the case of Lezha 263

12

7.6 Analysis of Findings 269 C h a p t e r 8................................................................................................................ 272 Conclusions and Recomandations ........................................................................................ 272 8.1 Conclusions............................................................................................ 273 8.1.1. Conclusions on Theoretical Background 273 8.1.2. Conclusion on Constants of Sacred Space.......................................274 8.1.3. Findings from applicative cases studies 275 8.2 Recommendation and suggestions for future research .....................285 8.2.1 Recommendation Error! Bookmark not defined. Bibliography 286

List of Figures

Figure 1 Division of the main theories used in research (Source: Author’s) ..........26

Figure 2 Methodology used for this research (Source: Author 35

Figure 3 Main objectives of the research (Source: Author) ....................................39

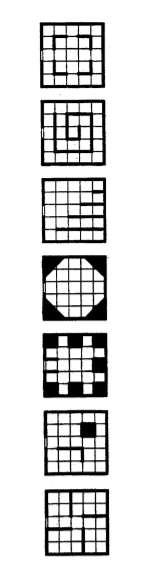

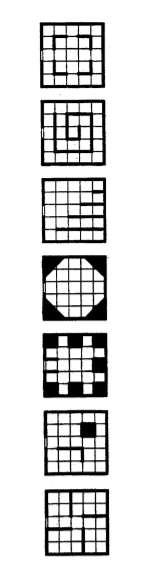

Figure 4 Thematic Model of plan 51

Figure 5 Presentation form the syllabus of Professor Bennett Neiman...................57

Figure 6 Work of one of the students, Jonathan Creel. form•Z -Course The Bebop Studio Texas Tech University 57

Figure 7 Explaining constants by Professor Bennett Neiman: Workshop Class ARCH 2501 57

Figure 8 Explaining Constants and Variables Workshop ARCH 2501 Professor Bennet Neiman 58

Figure 9 Setting up a Constant Workshop ARCH 2501 Professor Bennet Neiman 59

Figure 10 Constant relative to edge condition Workshop ARCH 2501 Professor Bennet Neiman ........................................................................................................59

Figure 11 Treatment Constant Workshop ARCH 2501 Professor Bennet Neiman .................................................................................................................................60

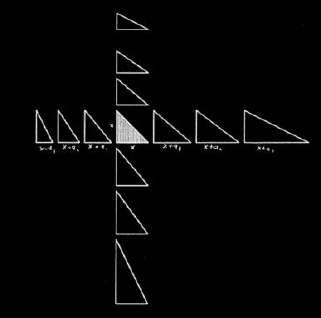

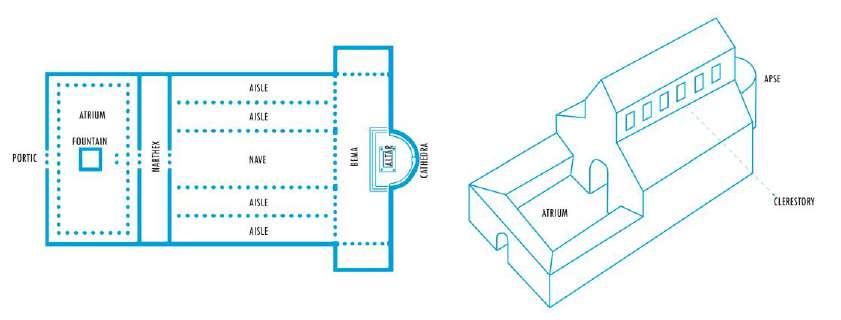

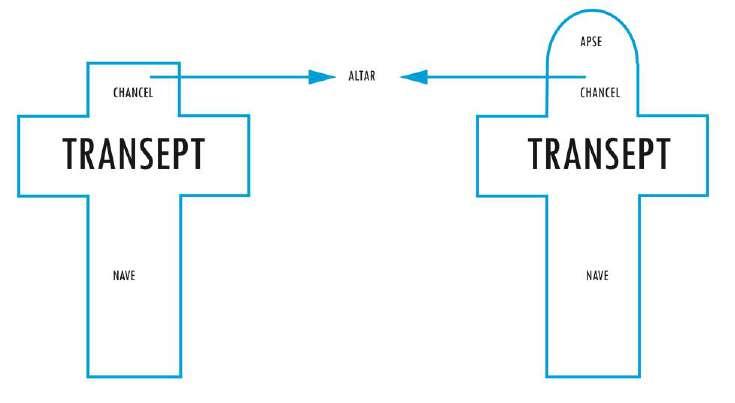

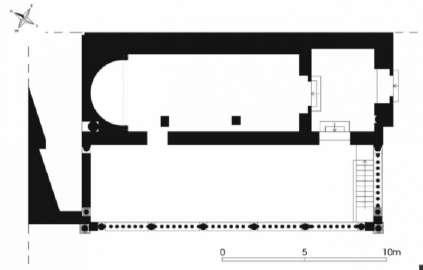

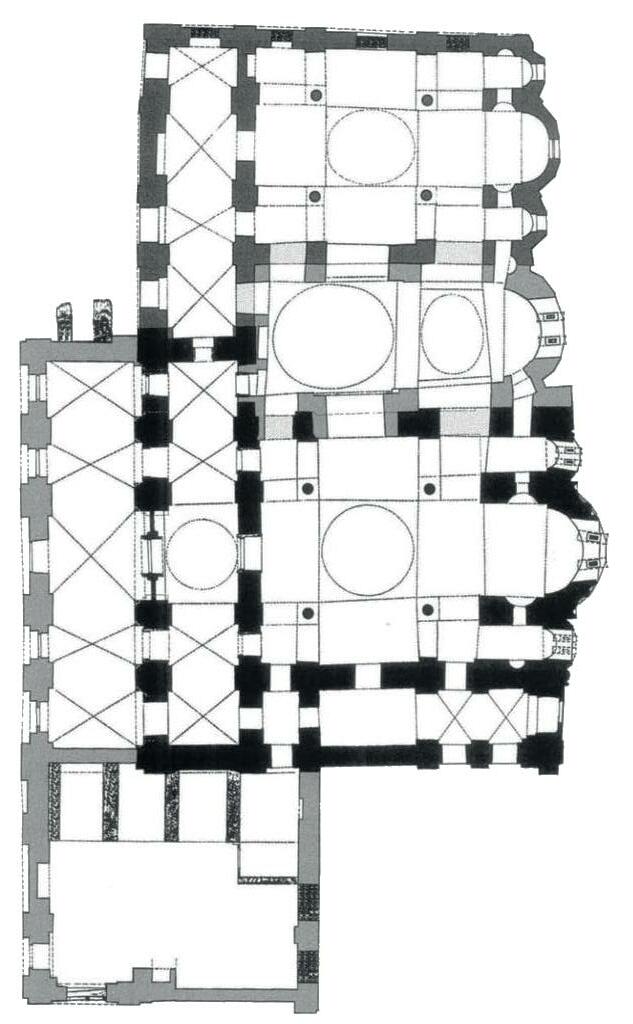

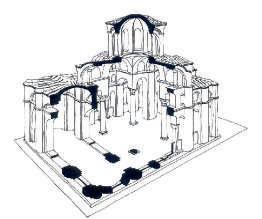

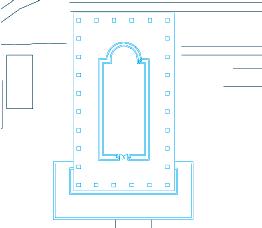

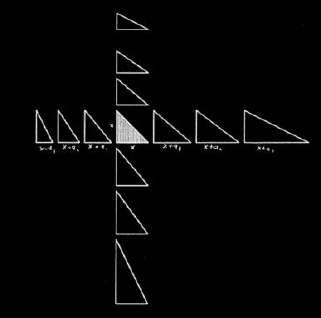

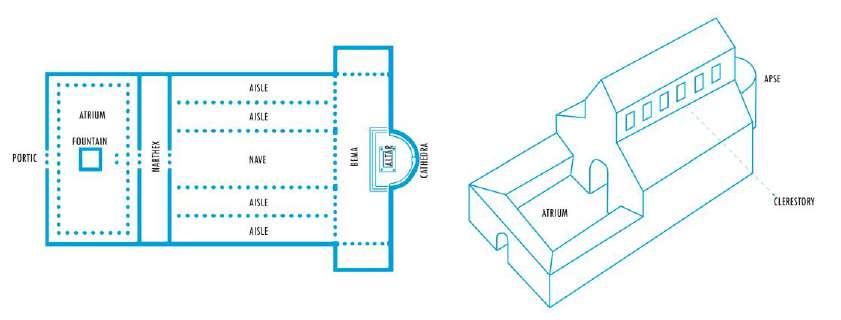

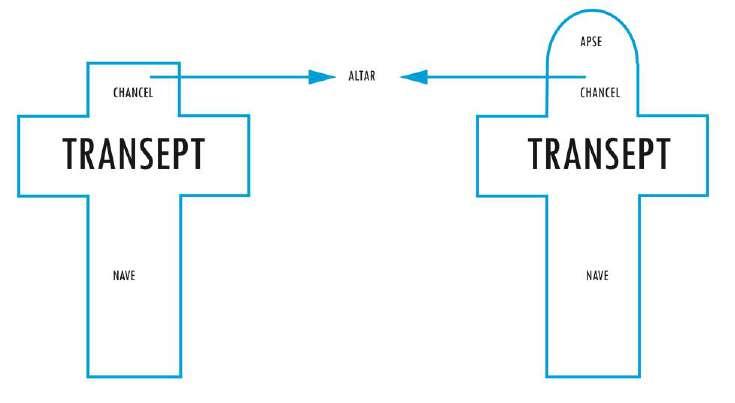

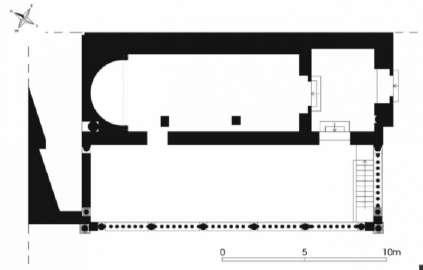

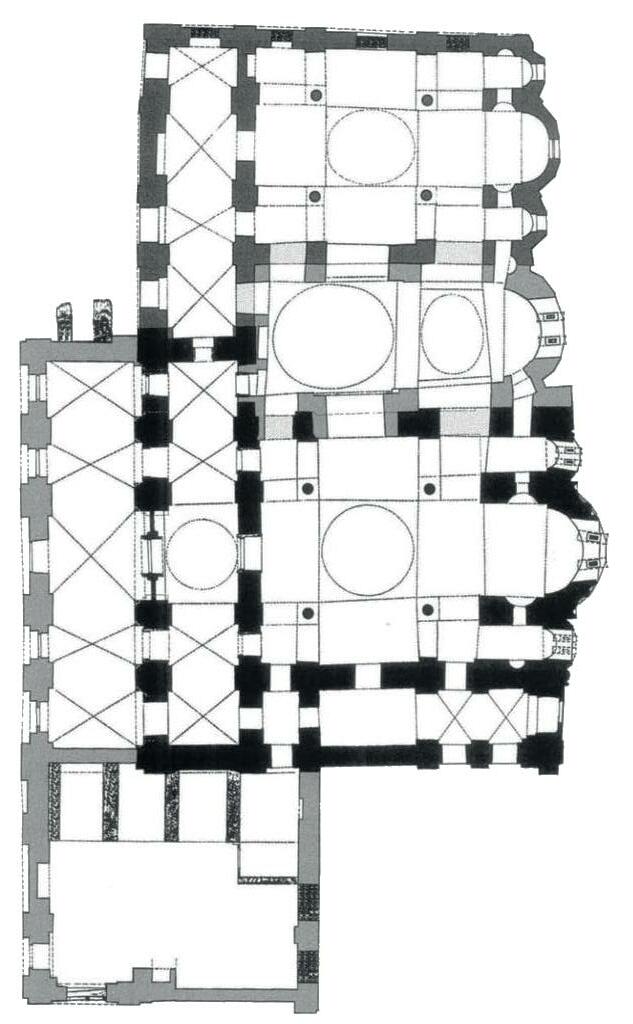

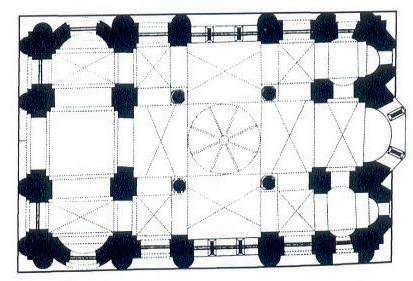

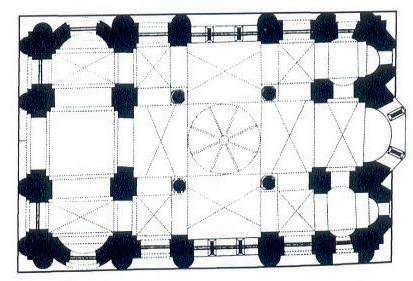

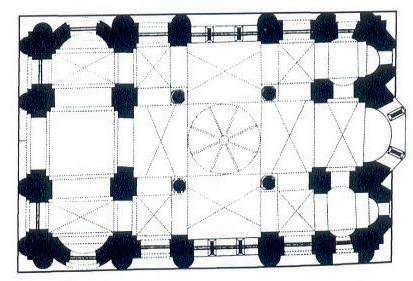

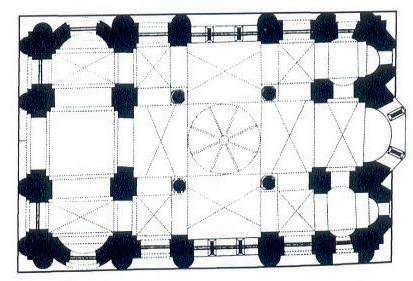

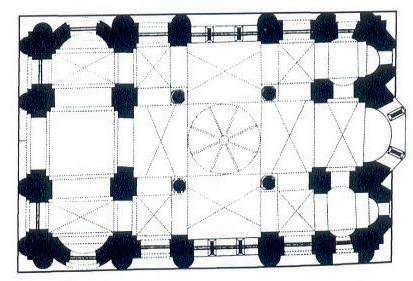

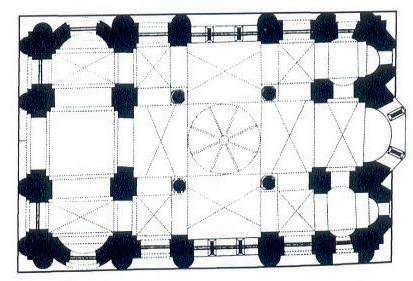

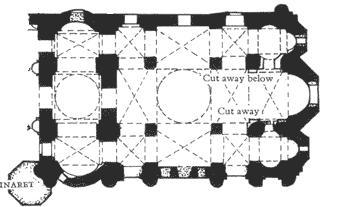

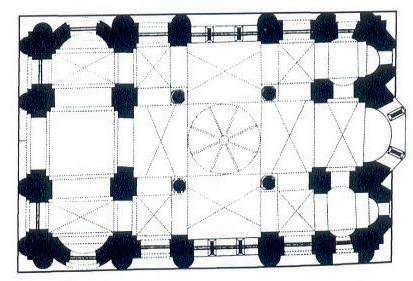

Figure 12 The architectural plan of Basilica in Christianity (Source diagram: Author).....................................................................................................................64

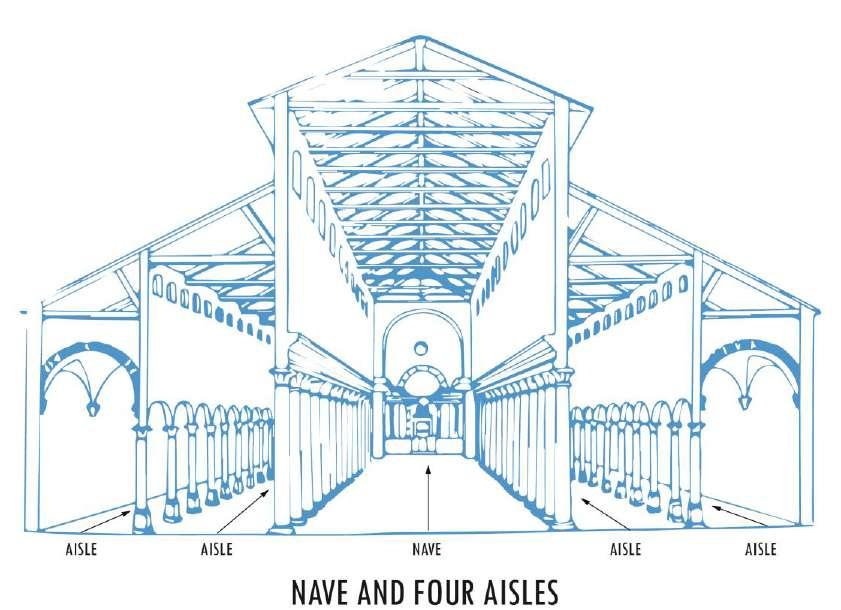

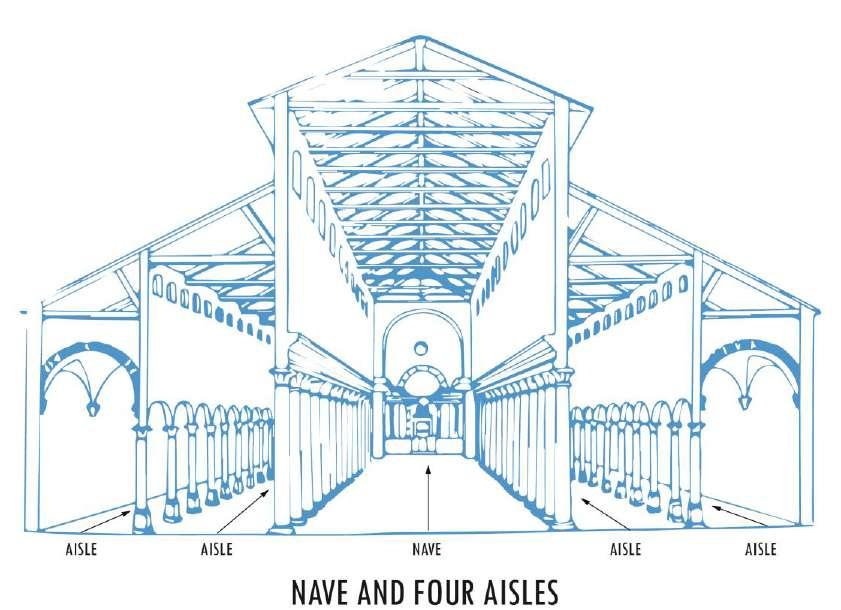

Figure 13 A section of the Basilica, the nave, and the aisles (Source Diagram: Author) 65

Figure 14 The first type: rectangular plan (Source diagram: Author).....................66

Figure 15 The second type: Cross plan (Source Diagram: Author) 66

Figure 16 In a functional orientation, the direction of prayer in a church should be toward the altar. (Source Diagram: Author)............................................................66

Figure 17 The longitudinal axial axis, which points toward the altar, is used to represent the church's physical orientation.(Source Diagram: Author)...................67

Figure 18 The altar is located in the position of the chancel, with or without the apse.(Source Diagram:Author)................................................................................69

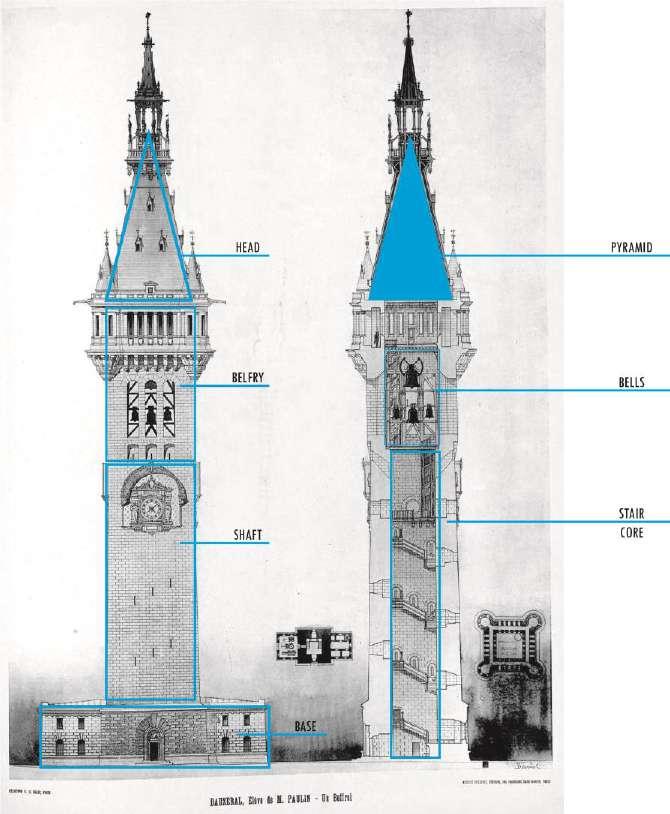

Figure 19 “Altar” (photo source: https://www.britannica.com/topic/altar).............70

Figure 20 General components of bell tower ( Diagram : Author) 71

Figure 21 According to Cresswell, the sacred region of Damascus (Syria) was reconstructed between the years 636 and 705 / Photo taken from (Guidetti, 2013)73

13

Figure 22 Functional Orientation, which is determined by the direction of Prayer to Kabaa (Source diagram: Author).............................................................................75

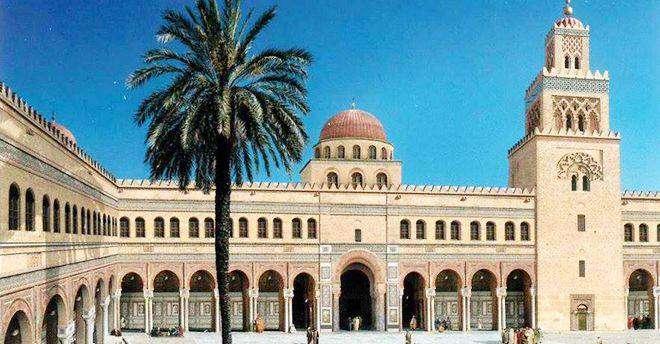

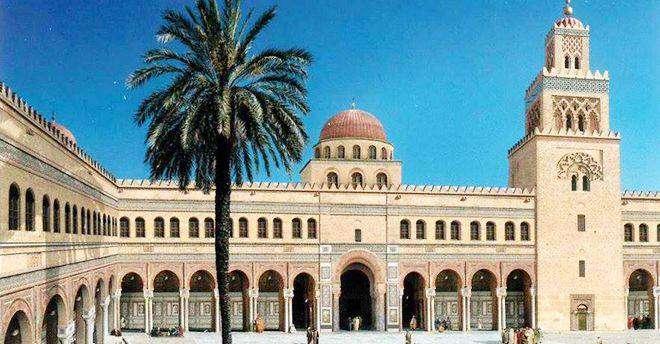

Figure 23 The example of Kairouan Mosque in Tunisia, whose main entrance is axial to Niche, demonstrates this. (Source: Author)................................................76

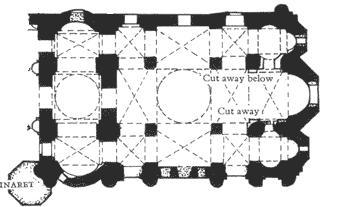

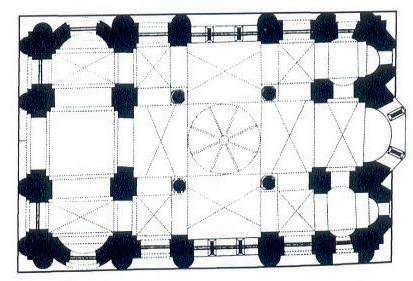

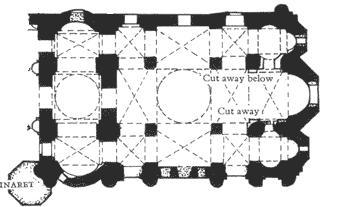

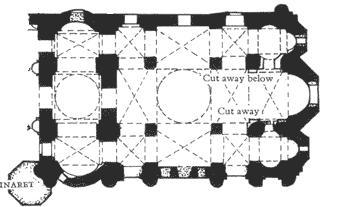

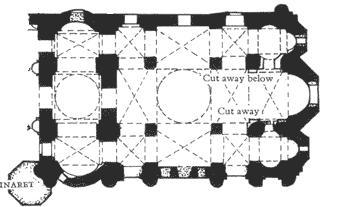

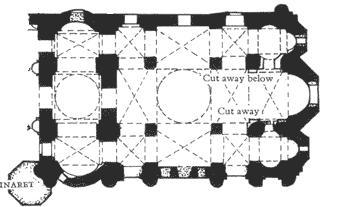

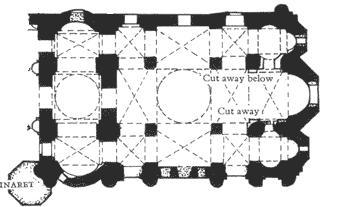

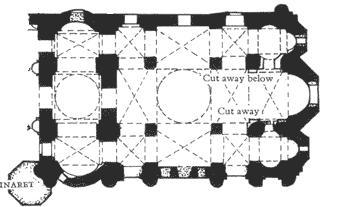

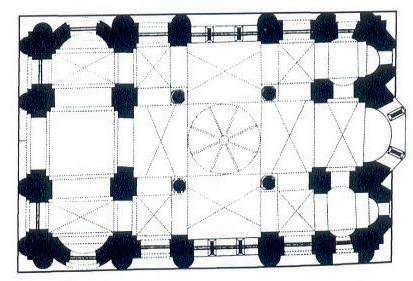

Figure 24 Examples of the three main typologies of mosque plans (Source diagram: Author).....................................................................................................................78

Figure 25 Model of a Niche (mihrab) in a mosque (Source diagram: Author) 80

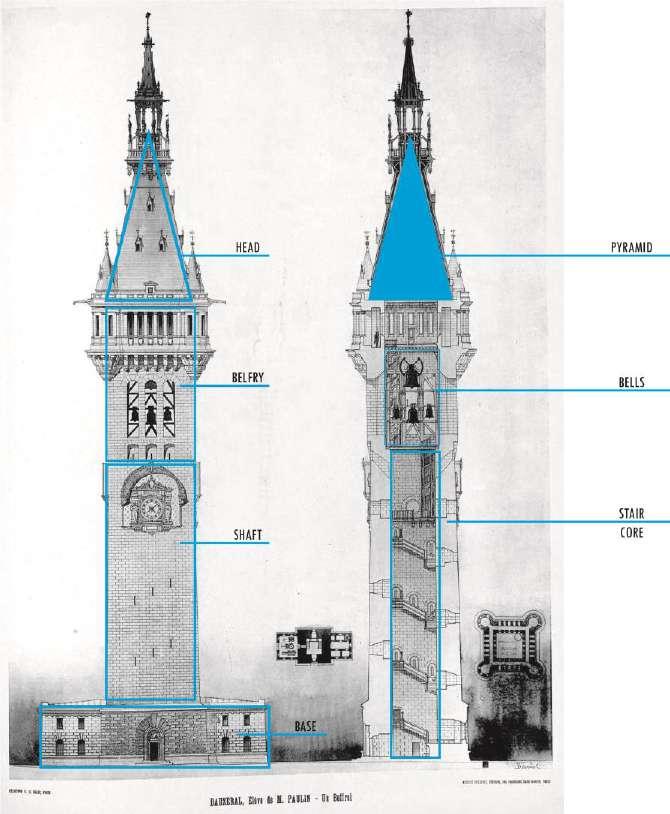

Figure 26 Elements that Make up the Minaret (Source diagram: Author)..............81

Figure 27 Model of a Minbar (Source diagram: Author)........................................83

Figure 28 Arjun Appadurai's five scapes for the globalization of cultural flows (Source: Author)......................................................................................................90

Figure 29 Photo collage shows two conceptually similar sacred spaces (Source Diagram: Author; Photo Source of Church of Seed Iwan Baan; Photo Source of Sancaklar Mosque Thomas Mayer).........................................................................91

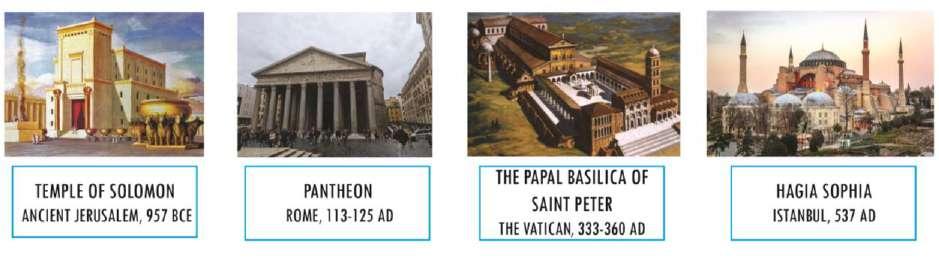

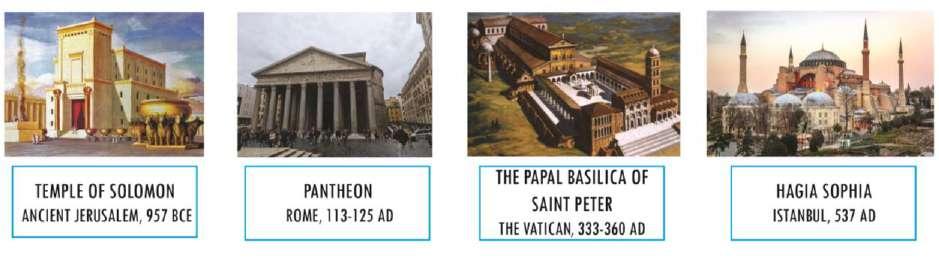

Figure 30 Most famous sacred spaces in world history (Source: Diagram Author, Photo Wikipedia).....................................................................................................92

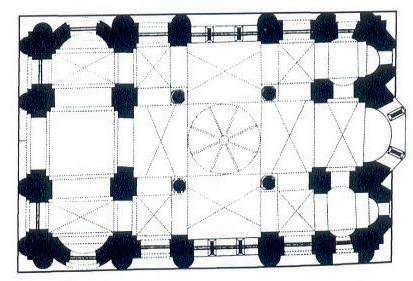

Figure 31 Vatican II Roman Catholic church general components (Diagram Source: Author) .......................................................................................................97

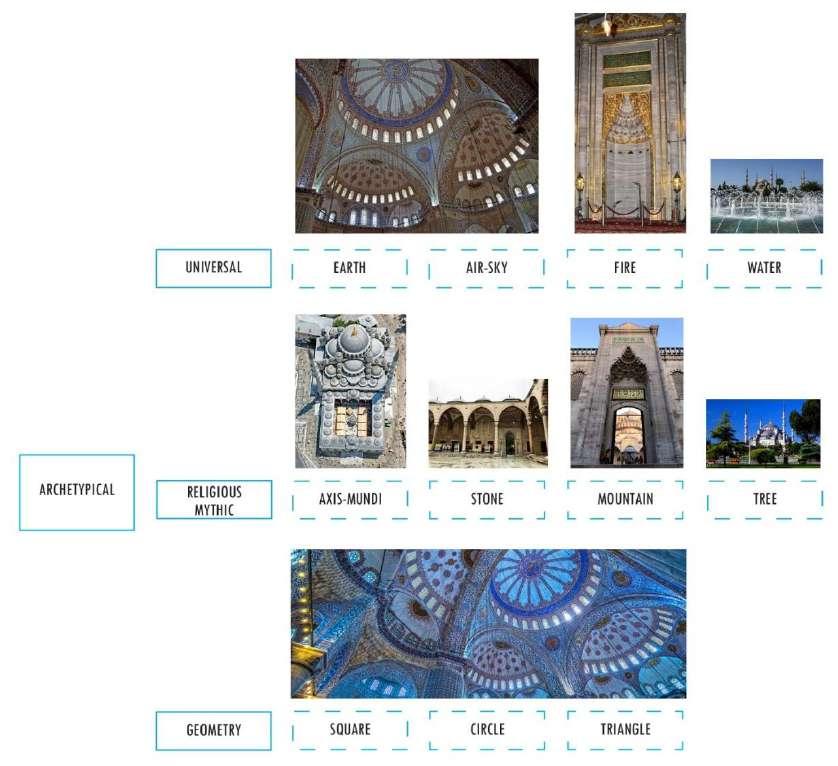

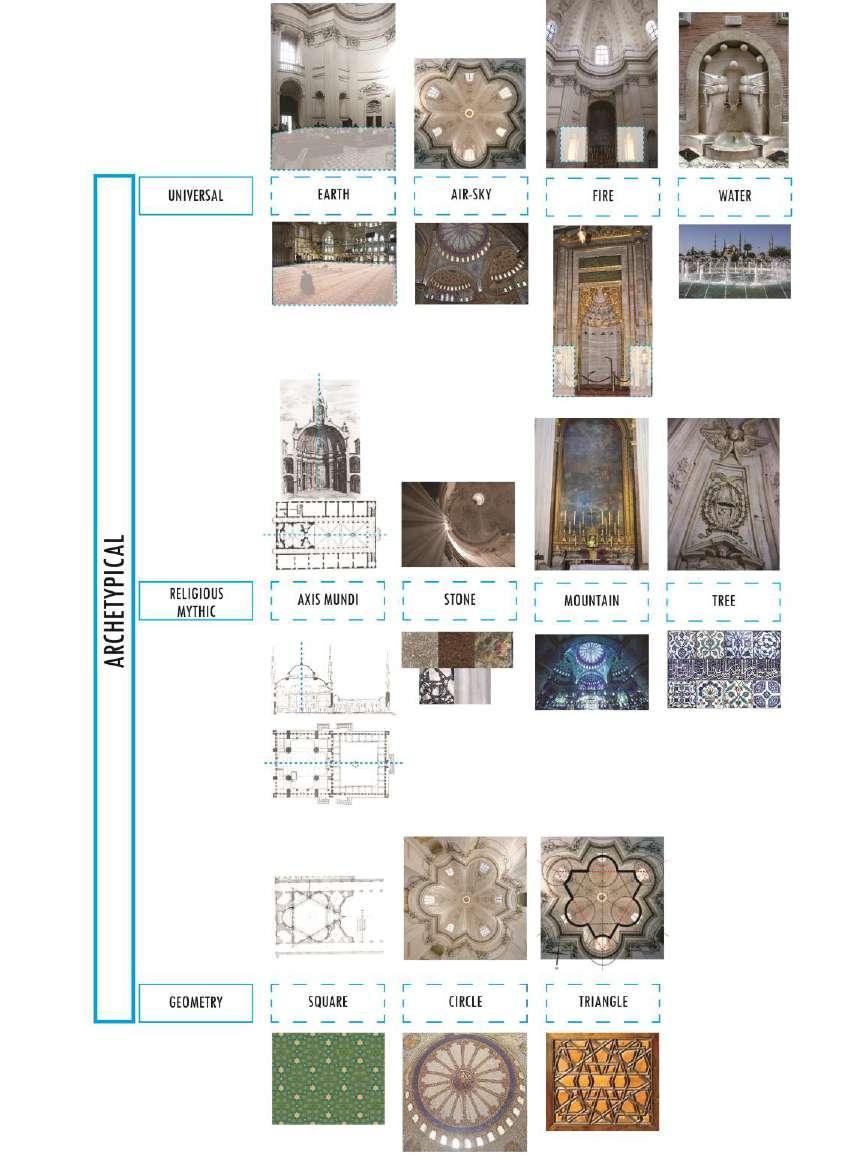

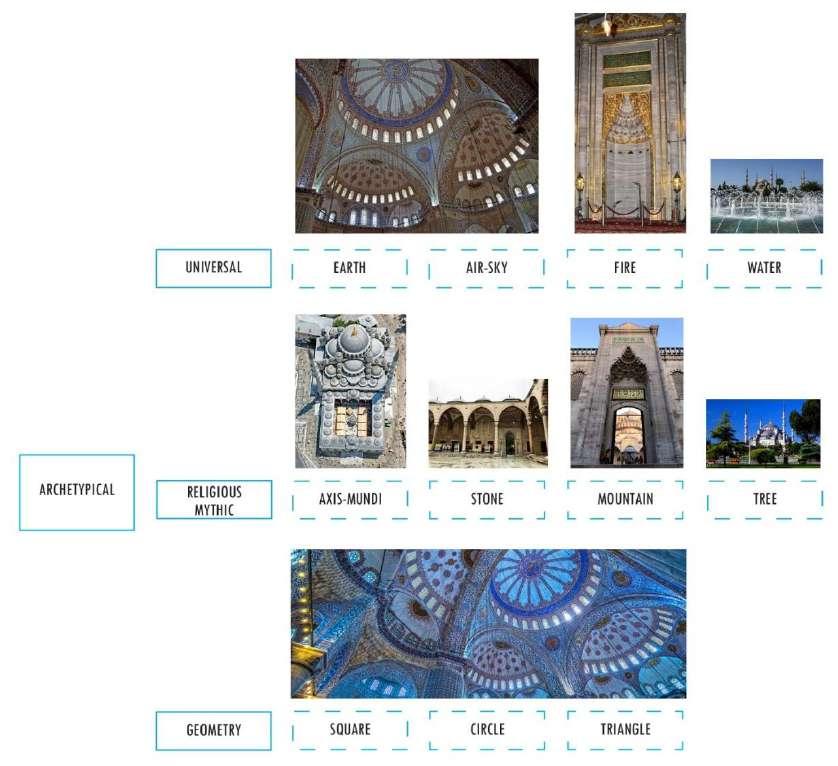

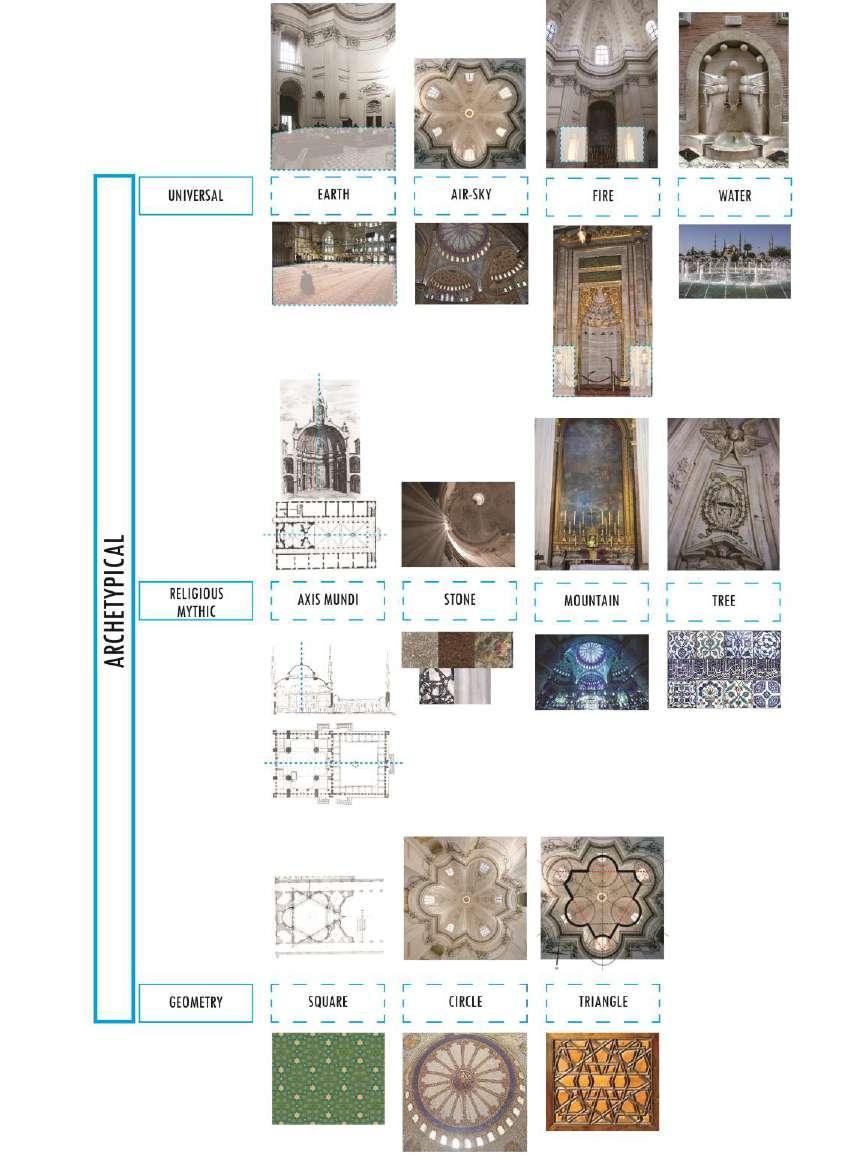

Figure 32 Constants of the sacred space (Source: Author) 100

Figure 33 Archıtectural elements of sacred space: exterior and interior 104

Figure 34 Archetypical elements of sacred space: universal, religious mythic and geometry 106

Figure 35 Atmospheric ambiguity of sacred space................................................107

Figure 36 The comparison of Christian and Islamic Architectural constants ( Diagram Source: Author) ......................................................................................109

Figure 37 The comparison of Christian and Islamic Archetipical constants (Source Diagram: Author) 111

Figure 38 The comparison of Christian and Islamic Atmospheric constants (Diagram Source: Author) 112

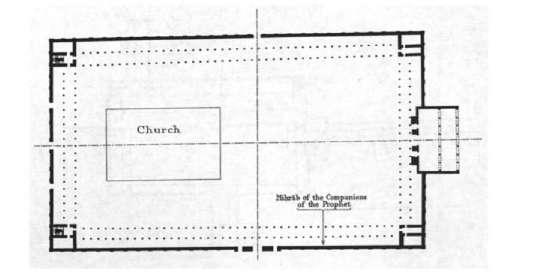

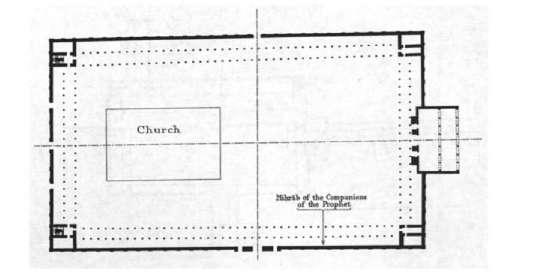

Figure 39 Floor plan of Prophet Muhammad's house in Medina (623 AD) (Mortada, 2011, p. 43)............................................................................................................116

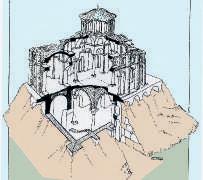

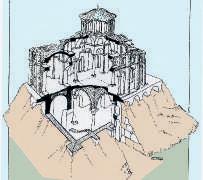

Figure 40 The conversion of Parthenon 117

Figure 41 Main ways of conversions (Diagram source: Author) ..........................120

Figure 42 The Ottoman Empire, 1300 1512 Source: Donald Quataer "The Ottoman Empire, 1700 1922" (Quataert, 2005)....................................................128

14

Figure 43 The Right to the City (Diagram from https://www.right2city.org/)......135

Figure 44 Map showing the distribution of the main sacred places according to the explanation given in the book The Antagonistic Tolerance..................................137

Figure 45 Map showing the distribution of the main converted sacred places in Albania according to the explanation given in the book Antagonist Tolerence (Source:Author).....................................................................................................138

Figure 46 Types of conversions (Diagram Source: Author) 139

Figure 47 Photomontage made by Author; Photo was taken from Marubi Museum _ www.marubi.gov.al ...............................................................................................143

Figure 48 Reci mosque in Tirana, Albania _ a house converted in mosque (Photo source: Author)......................................................................................................144

Figure 49 The hypothesis of the great mosque instead of the Cathedral of Palermo (Source: https://www.balarm.it/news/quando eravamo islamici la cattedrale di palermo era una moschea da 7mila fedeli 66008)...............................................150

Figure 50 Plan of the Remains of the Great Mosque in Palermo inside the Chapel of the Incoronata (Source: https://islamicart.museumwnf.org/database_item.php?id=monument;ISL;it;Mon01; 5;en).......................................................................................................................150

Figure 51 Sain Giovanni degli Eremiti in Palermo (Photo Source: Author, July 2022) 152

Figure 52 Plan of the Remains of the Great Mosque in Palermo inside the Chapel of the Incoronata. source : https://islamicart.museumwnf.org/database_item.php?id=monument;ISL;it;Mon01; 6; 153

Figure 53 The interior of the Misericordia church in Venice transformed into a mosque by the Swiss artist Christoph Büchel (Source: Photo credits Luigi Penello) 154

Figure 54 Faro Laser Scanner..............................................................................160

Figure 55 The integrated survey's methodological framework and organization (Source diagram: Author) 161

Figure 56 FIRST STEP : The process of calibrating entails assigning a unique code to each site. (Photo Source: Author, August 2021) 162

Figure 57 Research Activities and Fieldwork (Source: Author) ...........................170

Figure 58 Istanbul general map (Source: Author) 171

Figure 59 Istanbul historic peninsula map (Diagram Source : Author).................172

15

Figure 60 Map of selected monuments in Istanbul (Diagram Source: Author) ....173

Figure 61 General historical information of Hagia Sophia Cathedral, Istanbul,Turkey (Diagram Source:Author)............................................................175

Figure 62 Plan,section and photo of the mosque of Santa Cruz in Toledo, Spain mosque converted in church (Source: http://hiddenarchitecture.net/mosque of cristo de la luz/) ....................................................................................................177

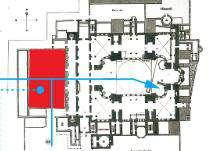

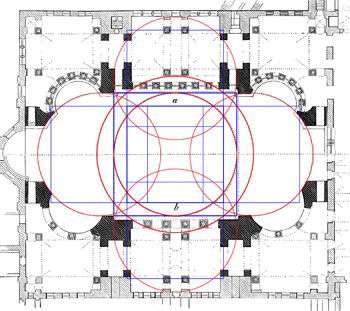

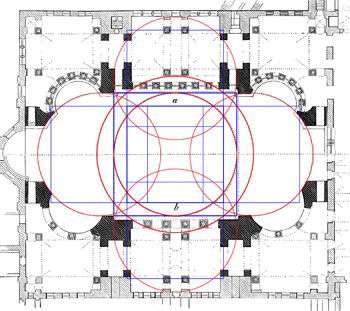

Figure 63 Saint Sophia church-mosque floor plan (Source: https://chnm.gmu.edu/worldhistorysources/analyzing/mcobjects/fp.html)...........178

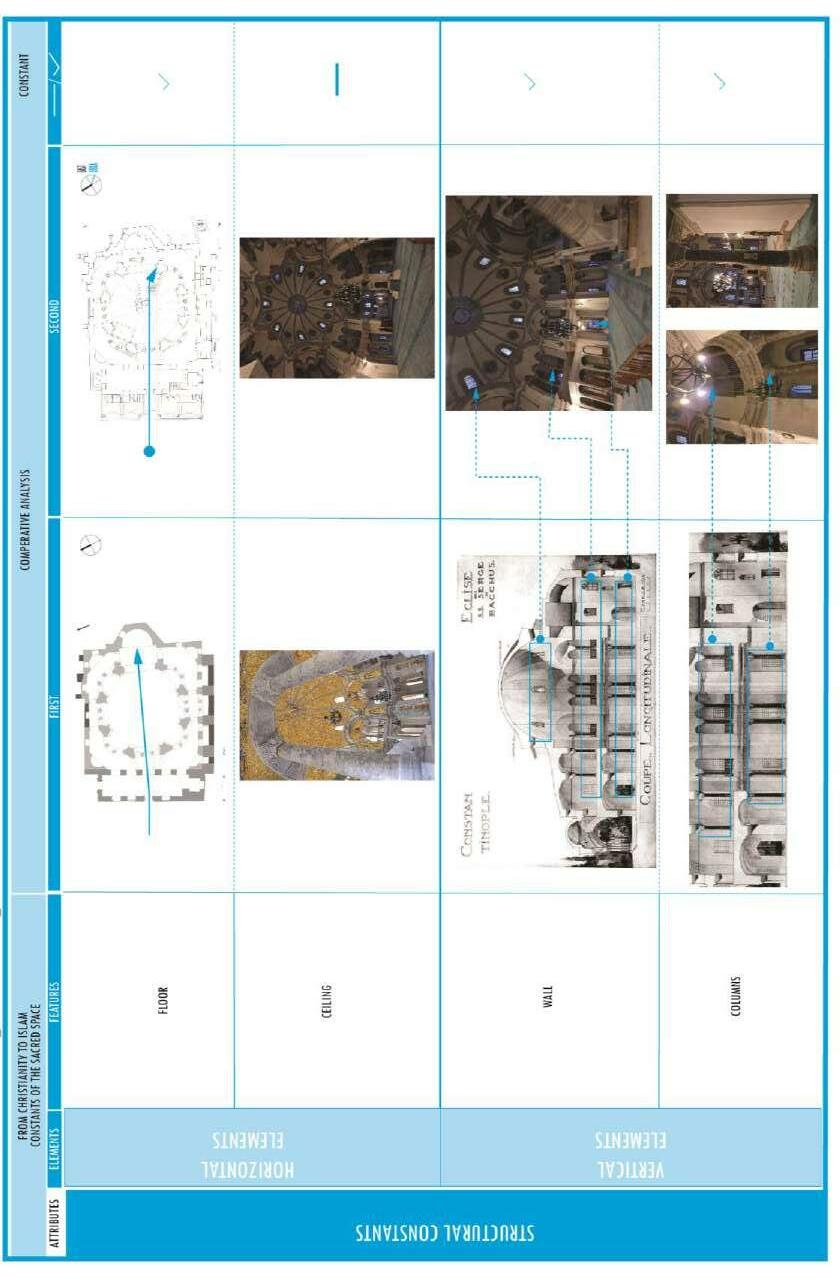

Figure 64 Structural Constants (Diagram Source: Author) ...................................179

Figure 65 General historical information of Little Hagia Sophia Mosque, Istanbul,Turkey (Diagram Source:Author)............................................................181

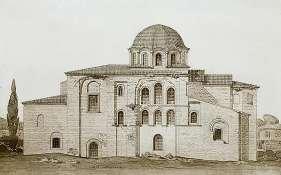

Figure 66 The Exterior of Little Hagia Sophia Mosque (Source photo: author_ Istanbul January 2021)...........................................................................................182

Figure 67 The Interior of Little Hagia Sophia Mosque (Photo Source: Author_Istanbul January 2021) 182

Figure 68 Analysis of structural constants (Diagram Source: Author) .................185

Figure 69 General historical information of Kyriotssa Church / Kalenderhane Mosque, Istanbul,Turkey (Diagram Source:Author).............................................186

Figure 70 General historical information of Kalenderhane Mosque, Istanbul,Turkey (Diagram Source:Author) 186

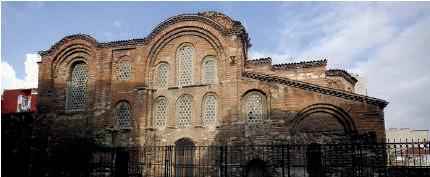

Figure 71 Exterior of Kalenderhane Mosque (Photo Suorce: Author on January 2021) 187

Figure 72 Sacred elements of Kalenderhane Mosque (Photo Source: Author Istanbul 2021) 187

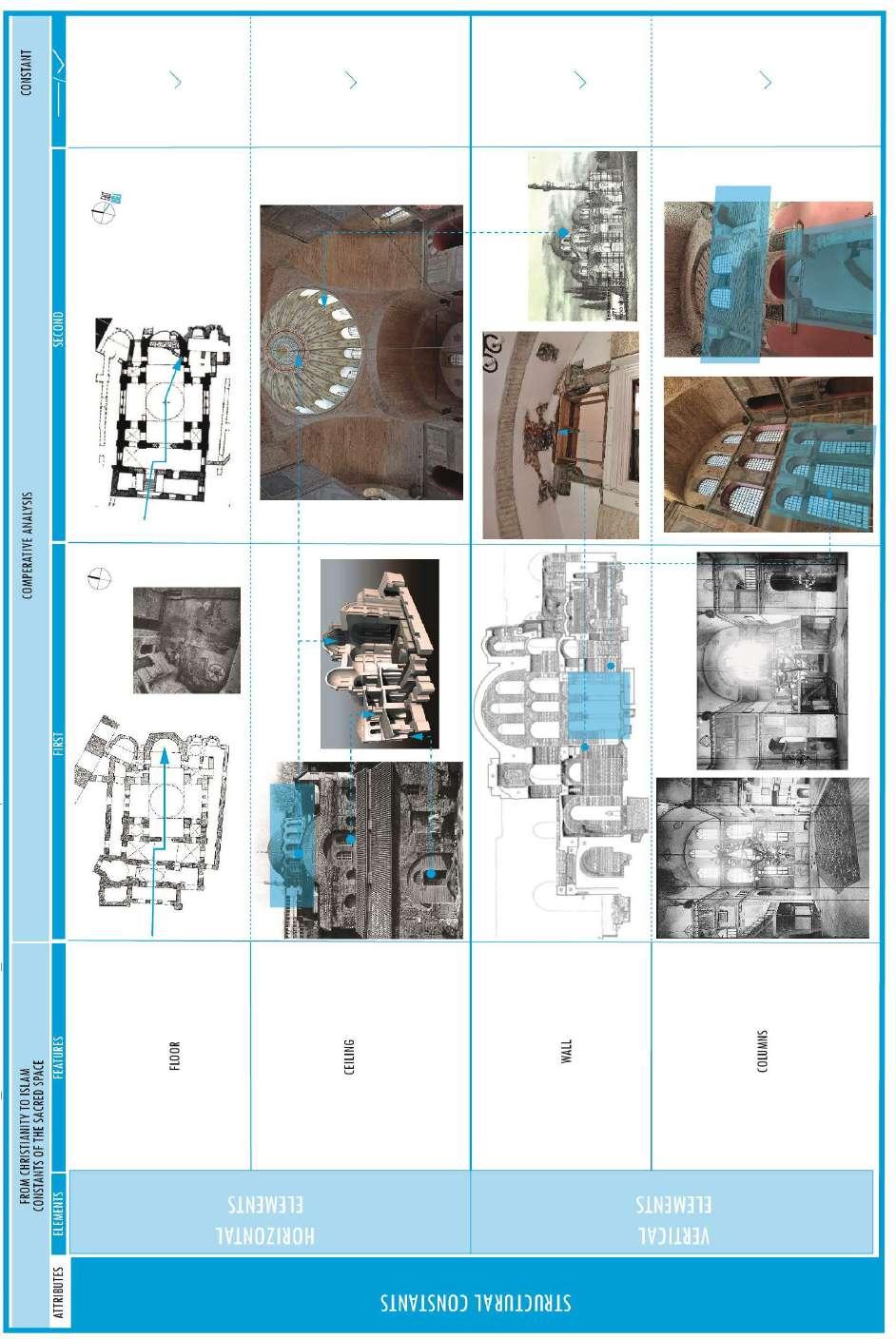

Figure 73 Structural constants analysis of Kalenderhane Mosque (Source: Author Diagram)................................................................................................................190

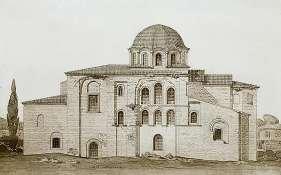

Figure 74 General historical information of Pantokrator Monastery / Zeyrek Mosque, Istanbul,Turkey (Diagram Source:Author).............................................192

Figure 75 The exterior of the Zeyrek Mosque (source: photo by author_Istanbul 2021) 192

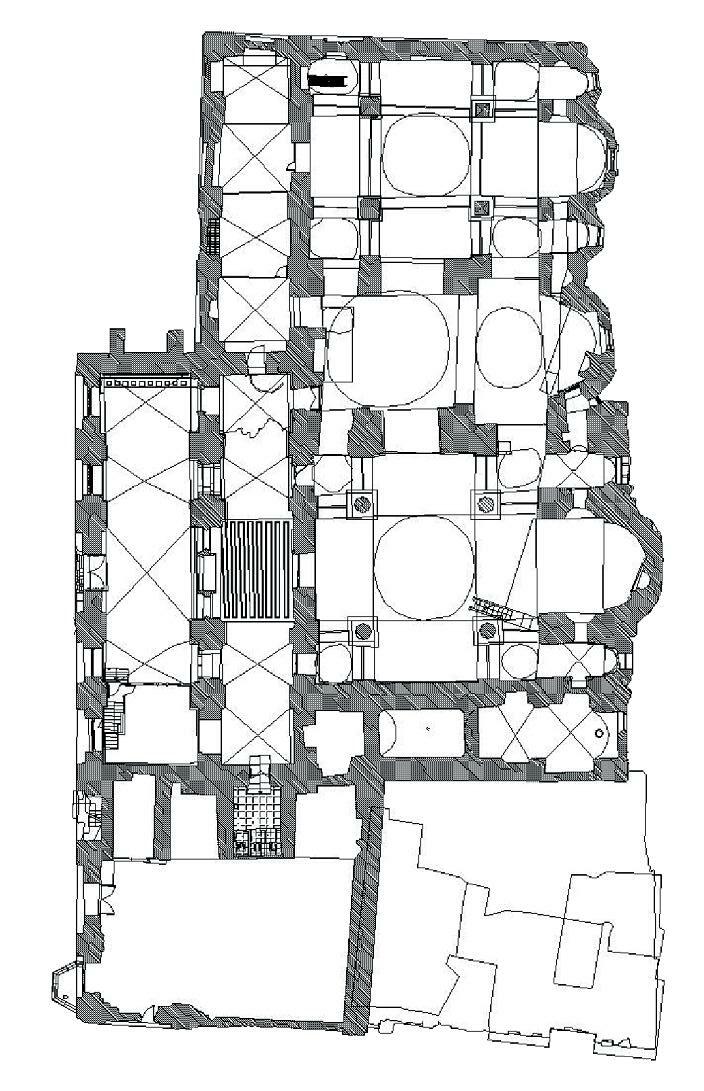

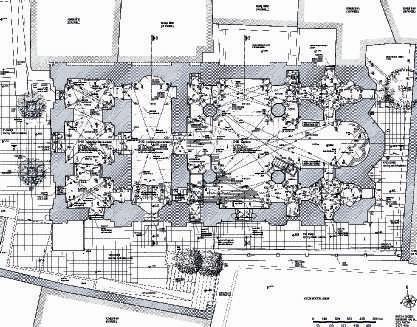

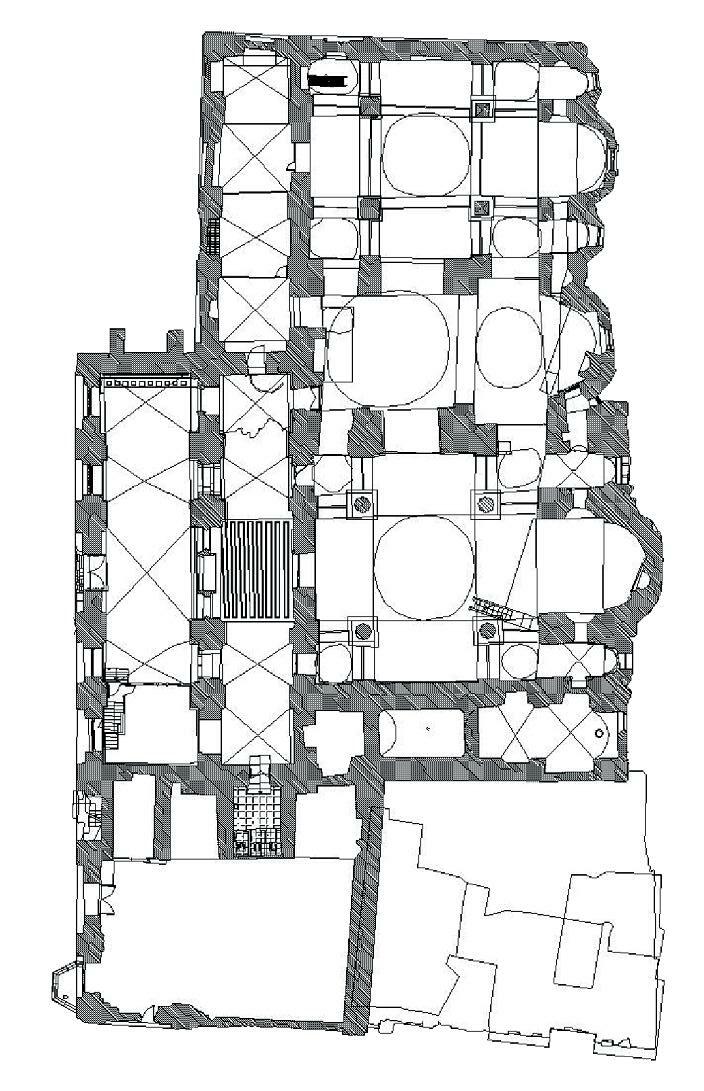

Figure 76 Zeyrek Camii,plan of complex (Source:https://www.academia.edu/4462860/Study_and_Restoration_of_the_Zeyre k_Camii_in_Istanbul_Second_Report_2001_2005)..............................................193

Figure 77 Structural constants analysis of Zeyrek Mosque (Source: Author Diagram)................................................................................................................197

16

Figure 78 General historical information of Myrelaion Church / Bodrum Mosque, Istanbul,Turkey (Diagram Source:Author)............................................................198

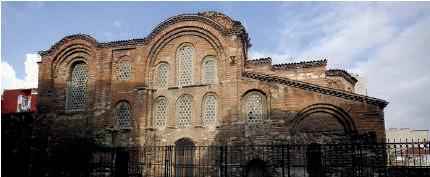

Figure 79 Exterier of Bodrum Mosque (Source: photo by author_Istanbul 2021) 199

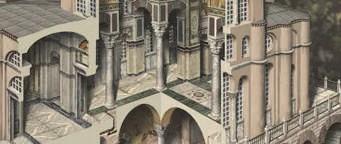

Figure 80 Palace of Myrelion IX in Constantinople and the Church of Myrelion (Photo Source: Created by Antoine Helbert / www.thebyzantinelegacy.com/myrelaion rotunda )..............................................199

Figure 81 Interior of Bodrum Mosque (Source: photo by author_Istanbul 2021) 200

Figure 82 Structural Constants in Myrelaion Church / Bodrum Mosque (Source: Author Diagram)....................................................................................................203

Figure 83 General historical information of Christ Akataleptos Church / Eski Imaret Mosque, Istanbul,Turkey (Diagram Source:Author).............................................204

Figure 84 Structural Constants of Eski Imaret Mosque (Source:Author Diagram) ...............................................................................................................................206

Figure 85 Structural constant analysis of the St.Theodoro Church / Vefa (Molla Gurani) Mosque ( Source: Author Diagram) 211

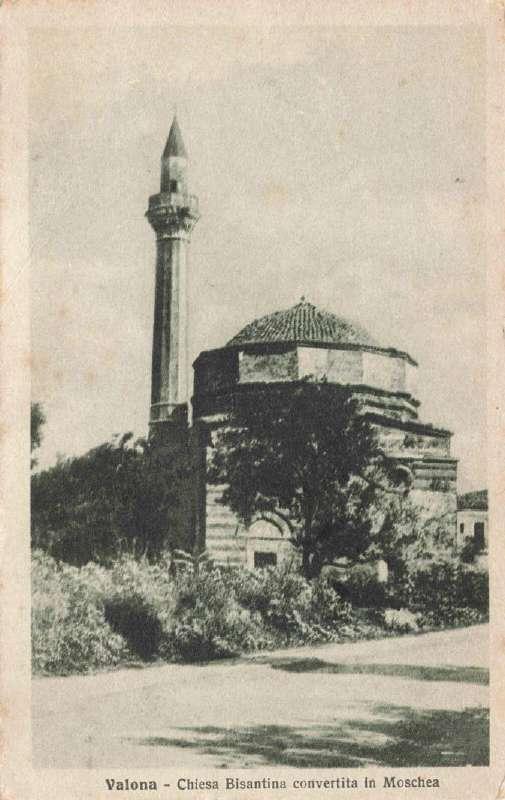

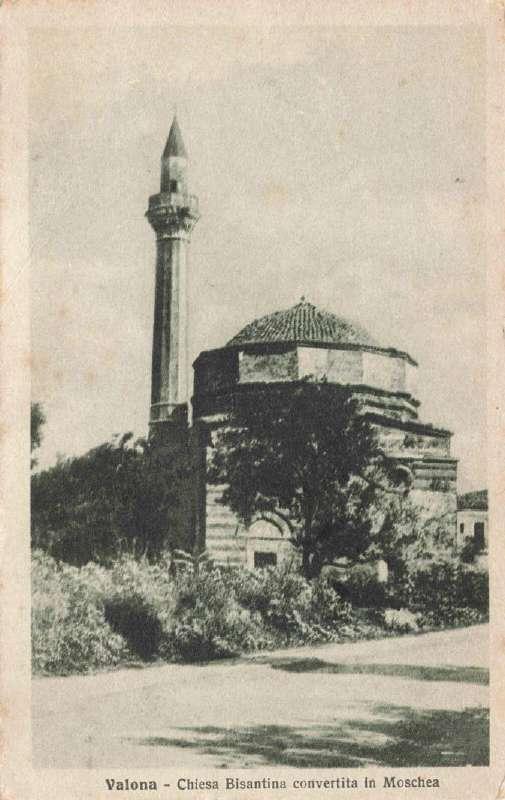

Figure 86 The Muradie Mosque in Vlora, old postcard with the inscription "Byzantine church converted into a mosque" (Source: Archive Photo ) 213

Figure 87 The exterior of Fatih Mosque (Source photo: Author, April 2022)......217

Figure 88 Old eastern wall of Fatih Mosque in Durrës (Source photo: Author, April 2022) 218

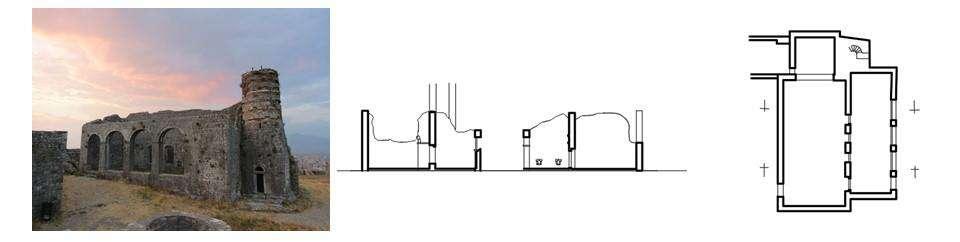

Figure 89 The ruined exterior of Shengjergj Mosque (Source: Author photo, December 2020) 219

Figure 90 Old photos of Shengjergj Mosque taken from the Archive of IKTK on 14 September 2020 220

Figure 91 The interior of Shëngjergj Mosque taken from Google Earth on March 2022 .......................................................................................................................220

Figure 92 The exterior of Gjin Aleksi Mosque (Source: Author Photo, 2022) 222

Figure 93 Interior Photo of King Mosque in Berat (Source: Author, March 2021) 223

Figure 94 Cartographic representation of the medieval center of the city of Berat (Source map: Dritan Çoku & Genc Samimi in "Kishat në Kalanë e Beratit") ......224

Figure 95 Excavation closed photo taken by author on March 2021 225

Figure 96 The construction report for the conversion of King Mosque into a Museum (Archive document teken from IKTK in 14 September 2020) 226

17

Figure 97 Red Mosque inside the Castle of Berat ( Photo source: Author, May 2022)......................................................................................................................227

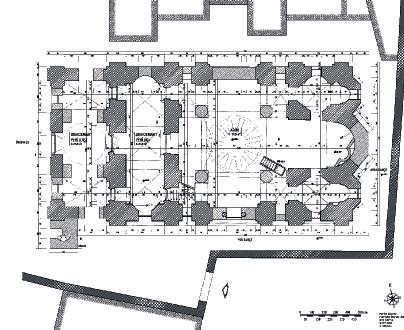

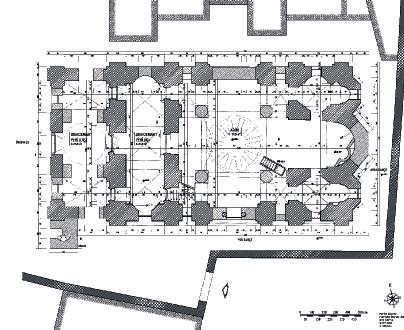

Figure 98 Plans interpretations (Source:Author)...................................................230

Figure 99 Archive photos (source: archive of IKTK, September 2020) ...............231

Figure 100 Reconstruction project from Institute of Monuments and Culture (Source: Archive IKTK, 2021)..............................................................................234

Figure 101 Calibrating the laser scanner codes (Photo source: Author, September 2021)......................................................................................................................235

Figure 102 Process of data acquisition (Photo Source: Author, September 2021)236

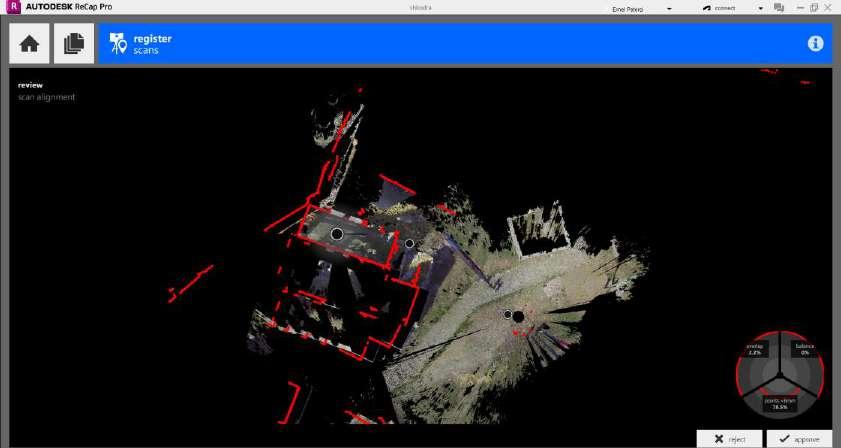

Figure 103 Position of laser scanner (Photo source: Author, issued from RecapPro 2021)......................................................................................................................236

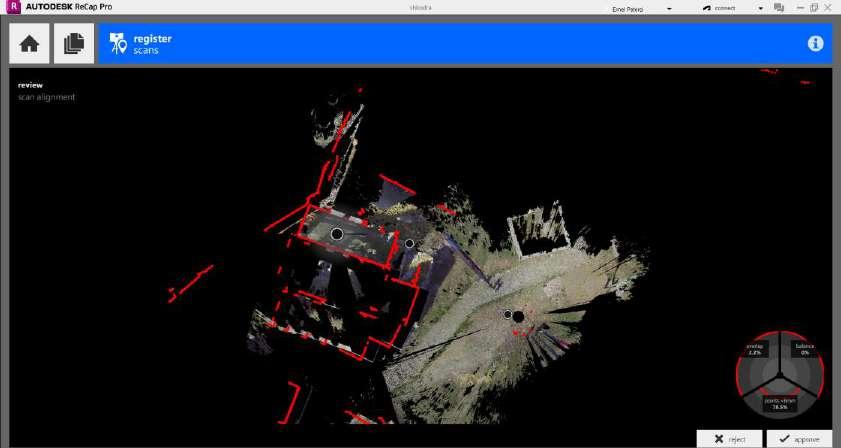

Figure 104 Image view from Recap Pro 2021 (Source: Author from Recap Pro 2021)......................................................................................................................237

Figure 105 Work on progress_Autodesk Recap Pro 2021 (Source:Author).........237

Figure 106 Final point cloud: about 220 million points (Source: Author from Autodesk Revit 2023)............................................................................................238

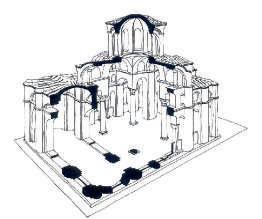

Figure 107 The beginning of the modeling of the two forms (Source Image: Author from Autodesk Revit 2023) ..................................................................................239

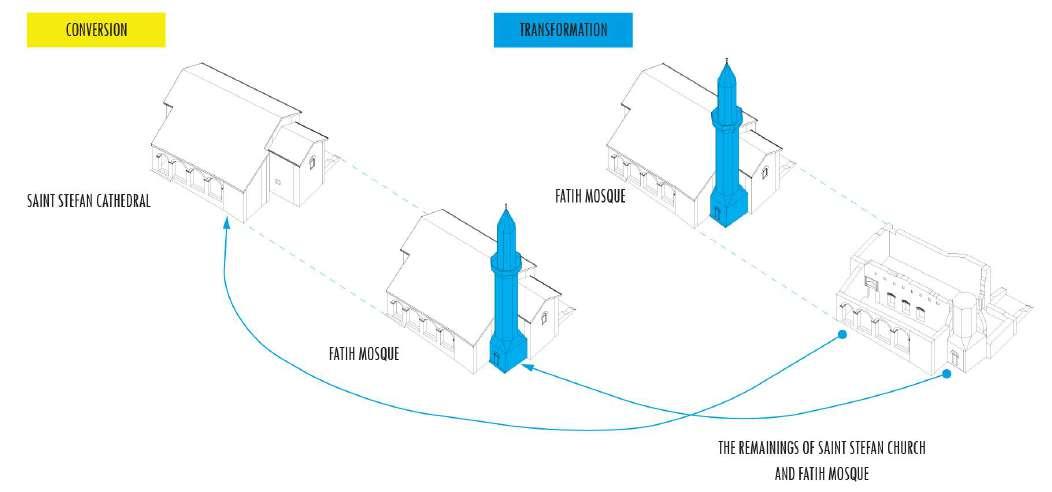

Figure 108 Diagram of conversion for the case of Saint Stefan Church and Fatih Mosque (Source: Author) 239

Figure 109 On the establishment of two states, the existing one and the hypothetical one such as the Saint Stefan Church and Fatih Mosque (Diagram Source: Author from Autodesk Revit 2023)...................................................................................240

Figure 110 Hypothetically images of the exterior of the church mosque (Source:Author).....................................................................................................243

Figure 111 Two different states of the church mosque (Source:Author)..............243

Figure 112 Hypothetically images of the interior of the prayer space (Source: Author)...................................................................................................................244

Figure 113 Memorial of the National Hero Scanderbeg (Photo source: author, August 2021) 245

Figure 114 Historic evolution of the building (Source Diagram: Author) ............246

Figure 115 Reconstruction of conversion phases (Source Diagram: Author) 246

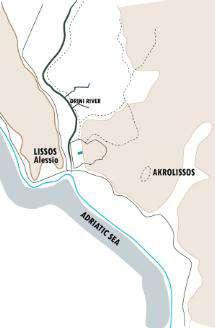

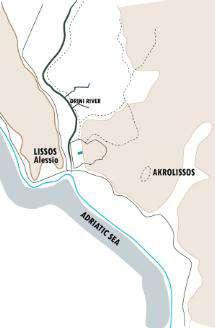

Figure 116 The general map Lissus (Source: Author)..........................................247

Figure 117 Archive data from Institute of Monument and Culture, Albania 248

18

Figure 118 First visual image in 1900 (Source photo: Archive of Institute of Monuments and Cultures; Diagram: Author)........................................................250

Figure 119 Second visual image in 1930 (Source photo: Archive of Institute of Monuments and Cultures; Diagram: Author)........................................................250

Figure 120 Third visual image in 1970 (Source photo: Archive of Institute of Monuments and Cultures; Diagram: Author)........................................................251

Figure 121 Last visual image in 2021 (Source photo: Google Earth; Diagram: Author)...................................................................................................................251

Figure 122 Comparativeness layers of the city silhouette (Source Diagram: Author) 252

Figure 123 The earliest religious transformation (Source Diagram:Author) ........253

Figure 124 The second conversion (Source_Author) 253

Figure 125 The fourth phase of conversion (Source diagram_Author).................254

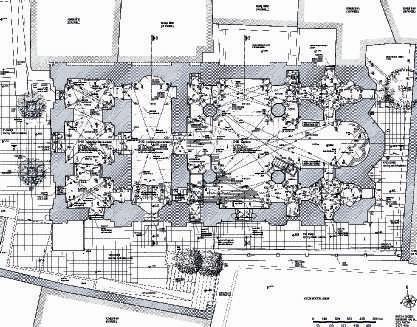

Figure 126 The laser scanner's data acquisition process is divided into several pr. (Source Photo: Author, September 2021) 256

Figure 127 The localization of the six scans that were taken using Faro Focus 3D, as well as the final point cloud, which contained around 110 million points (Source Diagram: Author)...................................................................................................258

Figure 128 Procedures for data integration. (Source Images: Author issued from CloudCompare) 258

Figure 129 Polygonal model (Source Images: Author Issued from Sketchup).....259

Figure 130 Overlay of the existing condition and form of the Selimiye Mosque, in Lezha (Source: Author, image taken from Autodesk Revit 2023) ........................262

Figure 131 The exterior of the hypothetically 3d models (Source: Author) 265

Figure 132 Hypothetically images of the interior of the sacred space ( Source: Author)...................................................................................................................266

Figure 133 The structural constant of the case of Lezha (Source: Author) 267

Figure 134 The two main forms of the monument: As the Nicholas Church and Seliminye Mosqye (Diagram Source: Author) 268

19

List of Tables

Table 1 Theoretical issues (Diagram source: Author) 29

Table 2 Historical Passport for each case study ......................................................33

Table 3 Converted Sacred Space classification.......................................................34

Table 4 Structure of the thesis (Source: Author).....................................................45

Table 5 Main theories for type.................................................................................48

Table 6 Mosque and Church Components (Source diagram: Author) 85

Table 7 General aims of constructing religious buildings.......................................89 Table 8 Architecture Conversion Summary 122

Table 9 Albanian's Beliefs according to WN Gallup Internation (2016) (Diagram source: Author elaboration)...................................................................................131

Table 10 The case of mosque converted in church in Italy_Cathedral of Palermo150

Table 11 The case of mosque converted in church in Italy_Sicily........................153

Table 12 Case studies of churches converted to mosques in Istanbul (Diagram Source: Author) .....................................................................................................174

Table 13 General historical information of Sain Sophia Church/Mosque, Istanbul, Turkey (Source Diagram:Author) 176

Table 14 Churches converted to mosques .............................................................215

Table 15 Mosques built on the ruins of the churches 216

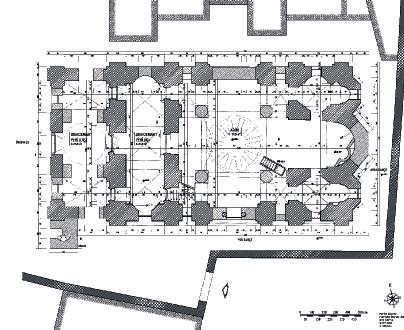

Table 16 Analysis of architectural and structural characteristics for the case of Shkodra (Source: Author) 270

Table 17 Analysis of architectural and structural characteristics for the case of Lezha (Source: Author) .........................................................................................271

Table 18 Results Obtained from Conversion of Churches into Mosque In Istanbul

Architectural Constants Exterior (Source Table: Author).....................................276

Table 19 Results Obtained from Conversion of Churches into Mosque In Istanbul

Architectural Constants Interior (Source Table: Author) ......................................277

Table 20 Results Obtained from Conversion of Churches into Mosque In Istanbul

Structural Constants (Source Table: Author) 277

Table 21 Results obtained from Conversion of Churches into Mosque in Istanbul

Archetypal Constants (Source Table: Author) 278

Table 22 Results obtained from Conversion of Churches into Mosque in Istanbul

Atmospheric Constants (Source Table: Author)....................................................279

20

Table 23Results Obtained from Conversion of Churches into Mosque In Albania

Architectural Constants Exterior (Source Table: Author).....................................281

Table 24 Results Obtained from Conversion of Churches into Mosque In Albanial

Architectural Constants Interior (Source Table: Author) ......................................282

Table 25 Results Obtained from Conversion of Churches into Mosque In Albanial

Structural Constants (Source Table: Author) ........................................................282

Table 26 Results obtained from Conversion of Churches into Mosque in AlbaniaArchetypal Constants (Source Table: Author) ......................................................283

Table 27 Results obtained from Conversion of Churches into Mosque in Albania

Atmospheric Constants (Source Table: Author) 283

21

C h a p t e r 1

Introduction

1.1 Research background

This study deals with a dilemma that has long troubled and conditioned the modern discourse on the architecture of sacred spaces. It is a dilemma related not only to reduce the tension between continuity and innovation but also to preserve tradition or history while finding genuine expressions for contemporary architecture. One of the phenomena that has intrigued this study is how different religions have shared the same space at different times. Ora Limor says: “ the nature of holy place retains its sanctity when it changes hand” (Limor, Sharing Sacred Space: Holy Places in Jerusalem Between Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, 2007)

22

In the following, the research looks closely at the ways in which space is loaded with meaning and, more broadly, in some aspects of space transformations how they were brought about and what constituted them. This thesis will parallel the study of constants as architectural theory and the research of sacred spaces converted for the Albanian case study. Also be able toprojecthowthesespaceswereexperiencedbefore thetransformationstookplace.Inaddition tohistorical,culturalreasons andarchitecturaltypologyit isimportanttounderstand how these objects should be treated at the level of documentation, restoration and maintenance.

Identifying constants in architecture is a process that many architects of different times study to understand architecture's faster perception. In this research are made the identification and ascertainment of the sacred spaces converted from the sacred spaces used as churches and converted into mosques, or vice versa. Mydiscussionfocuses on Muslim attitudes towards the conversion of the sacred space, how they have influenced the transformation of space, especially in Albania, during the Ottoman rule The sacred spaces converted, today constitute a very delicate theme for both the Albanian religious communities and the western Balkans. The first evidence of the conversion of sacred spaces are very early.

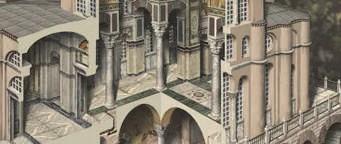

Thepossibilityof extending thearchitecturaldimension in thedigitalspace, recreatingthree dimensional forms that can then be used and experienced as natural spaces, is the basis of research that, through simulations in virtual settings, elaborates the metric and geometric correctness of the data inserted in the digital area to constitute archives on the architectural heritage in the hope of preserving their memory.

The research is organized into three main parts, which are linked together.

1 Theoretical Issues Included in The Process of Finding Constants in The Architectural Model of Sacred Spaces

This section is a literature review of typology in architecture, the sacred space's phenomenological approach, and the historical evolution of converted churches to mosques buildings.

2 Empirical research precedents Included in The Survey Process, Digital Models and Virtual Fruitions

This chapter provides the basic knowledge for continuing research in methodological terms. Furthermore, the chapter includes the historical analysis of the churches converted into mosques during the Ottoman period on the Mediterranean coast and further in Albania. The

23

methodology of using technological equipment to realize the necessary surveys is also explained.

3 Application case

This section analyzes the results of the above two part and translates them into a conceptual toolfordeterminingthesacredontheconverted objects.Thisanalysisisdoneintwoconcrete cases in the territory of Albania. Finally, recommendations are given on how the conceptual tool can be used in other research outside Albania.

1.2 Statement of the problem

Since antiquity, architects have devoted their time to the design of sacred spaces, and churches, mosques, and synagogues have continued to do so into the modern era. Because of this, many cultures have invested significant resources in the creation of sacred architecture, transforming them into structures that represent the human being as a whole. Sacred spaces are investigated in this study in order to determine what remains constant and to answer the critical question of what elements contribute to the creation of a sacred space.

1 When it comes to this project, one of the most difficult aspects will be analyzing the phenomenon of converted space through typological analysis, which will be something that manyauthors will doona regular basis. Thereis, however, a lack of understanding regarding the constants that are extracted during space transformations and transformations, which is a problem. Typological analysis and constituent components take precedence over those immutable elements that remain constant despite the changes that occur in the sacred space as a result of a variety of factors in other theoretical studies, such as comparisons between two or more sacred spaces, when it comes to other theoretical studies.

2 There have been numerous studies conducted on the primary markers of sacred space that have had an impact on many countries around the world, but there have been relatively few studies conducted on the creation of sacred architecture in Albania.

3 Another issue that has been raised in relation to the subject is that the data documentation fortheobjectsthathavebeenconvertedisonlyatthelevelofascertainmentbyarchaeologists or historyexperts whohavepreviouslydocumented suchanevent. However, therehavebeen no studies on the analysis of sacred spaces to determine the 'constants' that have remained constant throughout the manyshifts that havetakenplaceover thecourse of time. As aresult, based on the current situation, the second most significant obstacle to the completion of this

24

research is the lack of documentation and spatial analysis of sacred spaces that have been converted from churches to mosques in Albania. Even though the lack of illustrative and archival documentation is a significant challenge for this research, it will in fact provide an excellent opportunity for both Islamic and Christian communities to have an adequate documentation of the history and significance of some of the buildings that belong to both communities and have cultural and historical significance.

4 Another issue that was addressed in the study is the verification of the generalization of the elements that have been discovered theoretically in the literature and will be tested in practice. In light of the fact that this study will be applied to the Albanian situation, it is possible that using the same equipment for other countries that have undergone sacred space conversions will prove difficult.

1.3 State of Art

State of the art will consist of multiple themes using an extensive search engine. The first step is the beginning of the investigation of scientific publications that are very rich for case studies outside Albania and provide comprehensive information. In the case of this search, this exploration begins with a combination of keywords such as "sacred space," "type," "constant," and "converted," which will find publications on these topics. The most exciting publications have been preserved and used as examples for research. Identifying these first keywords will make it possible to identify other keywords needed to deepen the subject: "laser scanner," "digital cultural heritage," "virtual representation," and will gradually do to display research topics that we will need to structure.

The proposed research topic is quite broad and touches on many different areas, so there is a need to divide the theories used. There are four main areas of division of approaches; the most important ones that occupy a significant weight in research are the historical literature and views on typology. Historical literature is divided into three categories related to the theories used for sacred spaces such as churches, mosques, tekkes, or synagogues. The second category belongs to the history of the Ottoman Empire, and the third category to the history of Albania, mentioning historical approaches to connection with cult objects.

The second and essential division where the hypothesis of this research is based is related to the theories obtained in terms of typology, relying on two main categories in theories of type and constants. The third section is related to data acquisition, where various historical and archival books have been used to translate empirical data into graphics. The last division is

25

associated with digitizing data obtained empirically and digitally. The thesis will focus on the laser scanner, virtual reality, and augmentation.

Figure 1 Division of the main theories used in research (Source: Author’s)

A Theoretical background on history of sacred space

The theoretical background of history of sacred space is mainly based on late 19th and early 20th century theories. The Latin word "sacer," which was later used in the English word "sacred," means "dedicated or consecrated to a divinity, holy, sacred." A civic institution, a location, an altar, a sign, wealth, a tree, a boundary marker, or a mountain can all be referred to by this term. (Fowler, 2012)

In theoretical studies of "sacred space," the meaning of sacred spaces in the context of the complexities of the modern urban environment has been considered only occasionally. Traditionally,conversationsabout thesacredstartwithMirceaEliade(divine disruption)and Emile Durkheim (inviolability), and they sometimes finish with them as well, “fundamental ideas that change whether sacred meaning is ontological or natural in an object or space, or is socially constructed.” (Durkheim, 1982)

This research, analyze specifically buildings that were built as sacred, but now as a result of various changes and transformations have still remained sacred or have been stripped of sanctification. The researchers argue, according to this findings, that what becomes sacred is not constructed as extremelysecular or profane, but rather in interaction, or negotiation, with what was previously considered secular or profane. This research will further stimulate the

26

social dynamics of the processes of building and deconstruction of the sacred within the framework of the virtual world. The theoretical interpretation of the sacred is very important for this thesis because based on it is generated the conceptual tool for defining the sacred. The theoretical basis on which the main theories are described below in order of publication.

Emile Durkheim's book entitled “The Elementary Forms of Religious Life” first published in 1912, lays the foundations of the sacred as a social reality (Durkheim, 1982) Durkheim views the sacred in support by what he calls the "collective conscience." Durkheim's hypothesis that the change of the sacred and the profane stems from the difference between the almost shameful daily reality on the one hand and the collective consciousness within us on the other. This distinction, he argues, is both good and bad and is a fundamental characteristic of religious thought. Usually, the conclusions drawn from fieldwork studies are not taken entirely by him but by the Australian community. Yet these studies face numerous criticisms, and Durkheim conceptually fails to discern the degree of profanity he analyzes. But to conclude it must be said that his analysis of the sacred is essential in terms of the idea of the civic sacred. Also, as a derivative of it, the two authors, Victor and Edith Turnes, are mentioned in the research for the explanation they give to the pilgrimage ritual.

The second important text is Rudolf Otto's "The Idea of the Holy", published in 1917. The philosophical theologian argues that there is a whole dimension of human experience that Kant ignores in his three critiques of knowledge, ethics, and aesthetics, especially in his idea of religion within the confines of reason alone defined by Otto as the "numinous" experience or "mysterium tremendum," which are terms that characterize unattainable, overwhelming power and a sense of urgency. Relying on Burkle and Kant, Otto points out the theory of sublimation, a vital component of the Romantic experience of wild places. Combiningthetwoterms, sublime numinous, Ottoargues that thesacred is a straightforward category: "so soon as an assertion has been clearly expressed and understood, knowledge of its truth comes into the mind with the certitude of first hand insight." (Otto, 1954, p. 75) We see numinous sublimations very prominent in architecture, whether in the prehistoric architecture of the megaliths in the Sphinx or the Gothic cathedral.

Another definition that needs to be defined is the use of the word sacred instead of holy. In everyday English sacred and holy seem to be synonymous with each other, but there is an omission between the two.

The third fundamental theorist studied is Mircea Eliade, a religious historian who published TheSacredand theProfanein1957.Eliade'stheorysupportstheargument that humanbeings are homo religious and that elements of myth appear in all forms of secular thought. The common denominator that connects these theories under study is that they make an absolute distinction between the sacred and the profane. Like Otto and Durkheim, Eliade is not

27

interested in the nature of thesacred but is moreinterested inthat imaginaryaxis of transition from the profane to the sacred. For example, religious buildings set a kind of threshold between the sacred and the profane; Eliade calls "port" and defines the boundary that separates or contrasts the two realities and stands in for the contradictory place of their communication. Eliade argues that religions, but do not define all religions, create an "axis of power" axis in the shape of a holy pillar that spiritually connects the underworld to the earthly realm and the heavenly realm to the underworld. Different cultures think of this axis as a mountain, turning it into a "central symbolism" (Eliade, 1987, p. 39) according to which: “(a) holy sites and sanctuaries are believed to be situated at the center of the world; (b) temples are replicas of the cosmic mountain and hence constitute the pre eminent [link] between earth and heaven; (c) the foundations of temples descend deep into the lower regions” (Eliade, 1987, p. 39)

Because man strives to locate his dwelling as closely as possible to the center of the world, the "Axis Mundi" argument can be applied to temples as well as any other type of building. The house itself is crucial because religious architecture took the cosmological symbolism present in the home. It is used to create this paradigmatic model. This study tends to show that ideas for sacred spaces are numerous; they may be related to a) a special place to honor or establish contact with what is called divine; b) a place where the collective consciousness is focused; c) a place perceived by numinous; d) a place that appears sacred; e) a place that makes reality a reality compared to the temporary, and f) a place in which the invisible becomes visible.

As seen in these divisions, the sacred never appear identical, in the sense of the religious and the secular.

A clear explanation of the term sacred space is more critical for this research. Although this research seeks to examine: first, the "natural world" those places which, regardless of religion, are sacred by the representation they have; second, the relation of the holy place to the story of the place; sanctified, fourth, the possibility of having a conceptual tool for the perception of the sacred in existing buildings and fifth, the use of the conceptual tool in the design of buildings as sacred spaces.

After the phenomenological explanation of the sanctuary, the research will focus on the formative aspect of the sacred religious spaces by concentrating only on the margins of

28

churches and mosques. Such a constructive, typological description is essential for this research. It will help confirm the hypothesis of the topic that the approach that both religious objects have to the sacred space is the same.

In explaining the history of the formation of the sacred space, the location of these spaces is also important. In this research, the focus will be on the history of the sacred spaces in Albania occupied by the Ottoman Empire Because of this, it is essential to make reference to and provide an explanation of the history of the Ottoman rule, with particular emphasis on their history, the history of the countries of the Balkans, and the history of Albania.

The history of Albania, due to many changes in the occupation, has undergone radical changes in history, which has influenced not only the political power but also the definition and experience of sacred spaces. This explanation is focused on the literature on the history of Albania. Still, it is mainly focused on studying the book by the author Machiel Kiel "Ottoman architecture inAlbania, 1385 1912" (Kiel, Ottomanarchitecture inAlbania, 1385 1912, 1990).

B-Theoretical background on theories of typology and constants

The term "constant," as defined by the Oxford English Dictionary, originates from the Latin verb, which meaning "to stand with" when it acts as an adjective, it means "not to interrupt in time and which acts continuously over a while," when it acts as a noun it means "a situation that does not change." (Cambridge Dictionary, 2022) The term "Constant" is widely used in algebra in "a fixed value." However, in the history of architecture, the word "constant"is little used by theorists, and it can even be said that its use is limited to a few authors such as Rossi, Semper, Rowe etc.

29

Table 1 Theoretical issues (Diagram source: Author)

What are constants in architecture and the explanation of them, who talked about constants in architecture? What is perceived as a constant in a given period? What is the importance of studying constants in a sacred architecture background?

C Theoretical Research / Data Source

Theoretical research and review of literature on the main topic and related sub topics based on books, journal papers, archive documents, and other online sources of information. All information sources are cited in the text, and a complete list of sources and literature is available on the Bibliography and References page. In contrast to quantitative analysis, the methodology proposes the study of qualitative data as typological constants in the configuration of sacred space.

D Theoretical Research / Digitalization

The following set of beliefs on the development of technology and computerization in the field of historic structures have been voiced by a number of experts working in the field of digital architecture.

The first theory is digital technology theory, which is connected to the use of digital technology in architecture, as mentioned by (T.S Andadari, LMF Purwanto,P.Satwiko, R.Sanjaya,2021).Accordingtothem,architecturemaydevelop thefollowingareasof digital technology performance:

“

(1) data based research, (2) modeling and simulation, (3) computer programming, (4) multi media presentation, and (5) knowledge and information management” (T.S Andadari, LMF Purwanto,P.Satwiko, R.Sanjaya, 2021).

From what has been said above, it is possible to draw the conclusion that the entirety of architectural design may one day be subordinated to digital technology. This would include not only the phases of designing and planning, but also the stages of implementation and product manufacture.

This section is crucial to the research of this thesis since it generates the lost constants in the case of Albanian converted artifacts, which as it is known are not preserved The use of

30

digital tools helps both in the digital conservation of those constants which are found from the analysis also helps in the hypothetical reconstruction of the lost constants.

The following are the two part that make up this stage of the research process: the first part pertains to laser scanning of existing cultural artifacts. The goal of scanning these artifacts is to protect the sacred space's constants. Integrated laser scanner survey (FARO) was used for space scanning, which is a veryprecise instrument for the construction of the digital model. Recap Pro was used to construct the digital model.

the second part is concerned with the formation of the existing digital model, which is formed by scanning and then hypothetical reconstruction based on the current model's trace. REVIT is the software used for this step. Spaces are reconstructed hypothetically to demonstrate two distinct stages, the first being the original state of space and the second being the transformed state of space.

Hypothetical reconstruction of transformed places assists us in analyzing spaces and identifying constants that were lost or damaged during conversions.

1.4 Methodology

Strategy

The research is both scholarly and applied. It is structured following three surveys fields: Theoretical framework; Empirical research precedents (case studies and Pilot Case Study: Lezha and Shkodra); Approaches toward Converted Sacred Spaces.

The first two survey fields are focused on two major set of literature: one makes up the “Theoretical bases for research” and the other set is about the “Empirical research precedents” (discussed in Part Two, Methodological Issues Included In The Survey Process, Digital Models And Virtual Fruitions

The “Theoretical bases for research” it is explained into 2 main chapters (discussed in Chapter Two, THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK and Chapter Three, THE "SACRED SPACE" RELIGION SCAPE”): literature concerning the typological approaches in determining the term constant and sacred spaces.

The main theories included in this two chapters are:

1 Theories on Type and Typology;

2 Theories on Archetype;

31

3 Theories on Architectural Constants;

4 Literature on Sacred Spaces Religio scape;

Empirical Research Precedents:

1 Mapping Christianity and Islam in the West Balkans;

2 Precedents on Converted Sacred Spaces;

4 The digital revolution in cultural heritage: the innovation of systems and procedures for cataloging, recording and representing reality;

In a century characterized by technological acceleration, heritage building documentation is the first step in resolving any built heritage problem, no matter how complex. In order for the documentation process to be successful, it is necessary to gather and examine a large number of quantitative and qualitative data points in order to generate reliable evaluations of the building's digital representation. In many instances, the activities of data collection and interpretation are carried out in an uncoordinated way by a variety of actors serving a variety of reasons. This research focuses on converted spaces because of how thoughtfully they should be treated during their conversion or restoration, which is the focus of this research. Specifically, this research focuses on converted spaces because of the dualities that these spaces demonstrate In order to gain a more in depth understanding of the structure's inheritance status and to provide a solid foundation for comparative spatial analysis, the extracted data aredivided intofour categories:theavailabledocumentation, the underground materials that include the building's performance, the historical data related to the structure's morphology over time, and the available documentation and underground materials.

Creating documentation for converted space analysis is critical in studying built heritage, as it contributes to "creating a permanent record" (Rossi A. , The Architecture of the city, 1966) of the past and its presence in a city's present. The current state of the “analytical report,” as well as the understanding of its veracity, supports the idea that the report should be kept around for the foreseeable future. When the modeling of the databases and the visual model of the architecture are integrated in this manner, the results are as follows: a sophisticated information system that can be altered and interacted with is produced. With the assistance of this technology, it is possible to comprehend the significance of architectural heritage, provide information about it, communicate about it, and increase its worth.

32

The methodology of this research is divided into five phases which are related to each other. In the first phase, the research deals with collecting primary materials related to the selection of relevant literature that will help in the historical aspect of the research. Also, materials related to the existing theory of architecture mainly related to typology, this to verify the transition of type to archetype to constant; as well as materials related to the technological part that will be used to achieve the purpose of the research, i.e., technological instruments such as parametric and survey programs. The second phase of research development is related to selecting case studies, for which identification of all converted sacred spaces will be made. Because a significant portion of the investigation is concentrated on Albania, the examination of transformedspaces inthenations of theBalkans hasreceivedrelativelylittleattention. After identifying these spaces, a division was made into categories according to constituent components, location, functions.

The listing of all the converted sacred spaces also highlighted that these spaces are numerous, and the analysis of all of them would be impossible for the timeframes that this research has. Thus, some of them have been selected, which are more easily accessible and have more apparent conversion signs. For this phase, is done a more in depth analysis of all the data obtained fromthe materials found in thefield, questionnaires withprofessionals in thefield, or even residents of the area have been done. Also, the field data collection has been done with digital images. In the two case study, laser scanning and extraction of 2d and 3d models of converted sacred spaces were also used. The pre completion phase is related to the analysis of space to find the constant in the converted space. Simultaneously, the final stage is the recommendations regarding the constant components and how they will be used during these spaces' curative or restorative interventions

Table 2 Historical Passport for each case study

Regarding field visits, close field observation was generally used, but in places that were impossible to visit due to pandemic conditions, an online site survey was used. 3d google

33

Earth, online 3d, and 360 virtual tours were also used for the search to access inaccessible places, mainly those objects outside the territory of Albania.

Thisresearchisbasedonacomparativeand evaluativeanalysisofthespacesconvertedtoeach other in order to find the constants of the sacred space. Each case study is analyzed from the architectural point of view of the development of the same space before conversion and after conversion. The following table was used for this:

Table 3 Converted Sacred Space classification

The frequency of research.

The research imposition is of a regional dimension, which indicates that the selection of the singular case study is of the dimension of churches that have a broad interpretation of the phenomenon that is considered to be primarily social, cultural, and heritage dynamics. The research imposition is of a regional dimension because it indicates that the selection of the singular case study is of the dimension of churches that have a broad interpretation of the phenomenon. This demonstrates that the restrictions placed on research have a regional dimension.

34

35

Figure 2 Methodology used for this research (Source: Author

1.5 Research Problems and limitation

The study focuses on case studies occurring in Albania, as due to pandemic issues this period it was impossible to visit and study cases outside the territory of Albania. As is well known, the Christian and Islamic culture it has developed from the Middle East which has spread throughout the Mediterranean Sea, thus making it an inclusion of Asia, Africa and Europe. Many Mediterranean countries have sacred spaces that have been converted from Islamic to Christian or vice versa. This study focuses on the sacred spaces converted from church to Mosque. Therefore, the selection of case studies was done following some criteria which will be explained below.

Mosques and Churches develop in two types: complex and individual buildings. In the type ofcomplexbuildings,wearedealingwithspacesthat,inadditiontotheprayerspace,alsohave functionssuchasschools,commercialfacilities,museumsandhouses.Inthetypeofindividual spaces, churches and mosques perform only as prayer spaces and remain unaccompanied by other objects around them. In some of the Balkan countries there is another subcategory of these two typologies that has to do with the posture of different religious spaces in a common complex. This study will mainly take into account individual spaces but cases of merging different religious spaces into one complex will be treated as a special case of this research.

Mosques and churches are designed in a variety of typologies based on their intended usage. Thus, churches may be generalized and forcedly separated into chapels and basilicas, while mosques can be divided into Musala and Friday mosques.

Examples will be taken mainly from historical and significant churches and mosques positionedaroundtheMediterraneanSea,suchasItaly,Greece,Portugal,and Turkey.Usually, these cases will be taken as examples, while the study's focus will be only on Albanian cases. The reason for selecting the case examples is that the conversion of sacred spaces from the church to the Mosque took place in the main cities' centers, where the buildings had their character in the city. The conversion of these spaces has also affected the urban fabric by turning these cities into key religious importance sites.

Another factor thatcanberestrictiveis theconversiontime. TheOttomanEmpiremaintained control over Albania from the middle of the 14th century all the way up until the beginning of the 20th century. Because these countries had been ruled over for such a significant amount of time, religious influence began to permeate over them. The Ottomans carry out all these religious conversions of the population that reflect the way of life of the people, traditions, behaviors and architecture. This was also reflected in the conversion of religious buildings,

36

where manychurches were converted into mosques. It is essential toconsider that conversions and facilities are now taking place in older cities.

To achieve the analysis of these documents are limited based on the pioneers of foreign studies such as Dutch architectural historian Machiel Kiel and English historian Frederick William Hasluck, who have uncovered the history of past generations for Albania. Also the Albanianauthorswhohavehelped intheanalysis of thisresearcharethestudies of Aleksander Moisiu and Sulejman Dashi.

Thisresearchislimitedinshowinghowtechnologicaltoolsareusedduringthisresearch.Only a brief description of them will be made to have a general knowledge of the tools, but the purpose will not be this. This research is not intended to make an archaeological analysis of built heritage and will be limited to providing data on soil layers, masonry materials used in the science of archeology.

1.6 Research Questions

This study explores the constant space in a sacred space and analyzes converted sacred spaces during Albania's Ottoman rule Consequently, the central questions of this thesis are:

What is “constant” in a converted sacred space?

Specific Research Questions

a) What is a “Constant”?

What are the existing theories regarding typology?

Is type a “Constant”?

How are related the terms type, constant and archetype in their meaning for sacred space?