Anima gets beneath the surface of design, whilst understanding that appearances matter too. It is interested in what things mean, as well as how they look. As appealing to the professional as to the enthusiast, it understands that design never stands still and embraces the most vital issues. Its perspective is global and predictive. Beautifully designed and incisively written, Anima takes the subject out of the specialist domain and offers a clear and passionate view on where we are now.

024 044 072 076 034 070 074 078 106 120 168 088 118 154

CELEBRATING THE INAUGURAL WINNERS

FILMMAKER & PRODUCER

WANG BING

DANCER & CHOREOGRAPHER

MARLENE MONTEIRO

FREITAS

MUSIC COMPOSER & PERFORMER

JUNG JAE-IL

ARTIST COLLECTIVE

KEIKEN

GAME DEVELOPER & DESIGNER

LUAL MAYEN

FILMMAKER

RUNGANO NYONI

ARTIST & POET

PRECIOUS OKOYOMON

THEATER DIRECTOR

MARIE SCHLEEF

FILMMAKER

EDUARDO WILLIAMS

DANCER & CHOREOGRAPHER

BOTIS SEVA

Creating the Conditions for Artists to dare

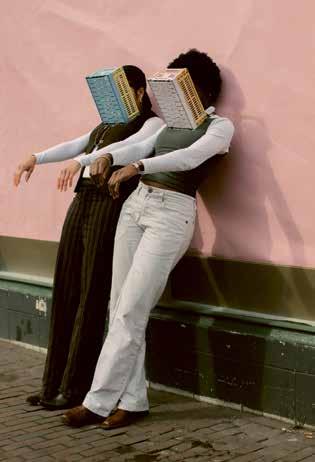

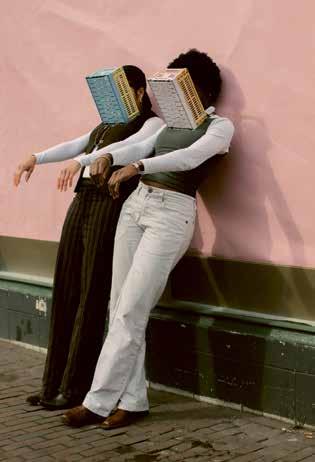

Image: Keiken, 2021

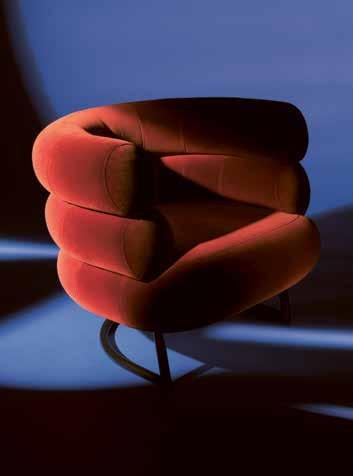

THE CASSINA PERSPECTIVE cassina.com Milan Paris New York London Los Angeles Madrid Dubai Tokyo

The Origina

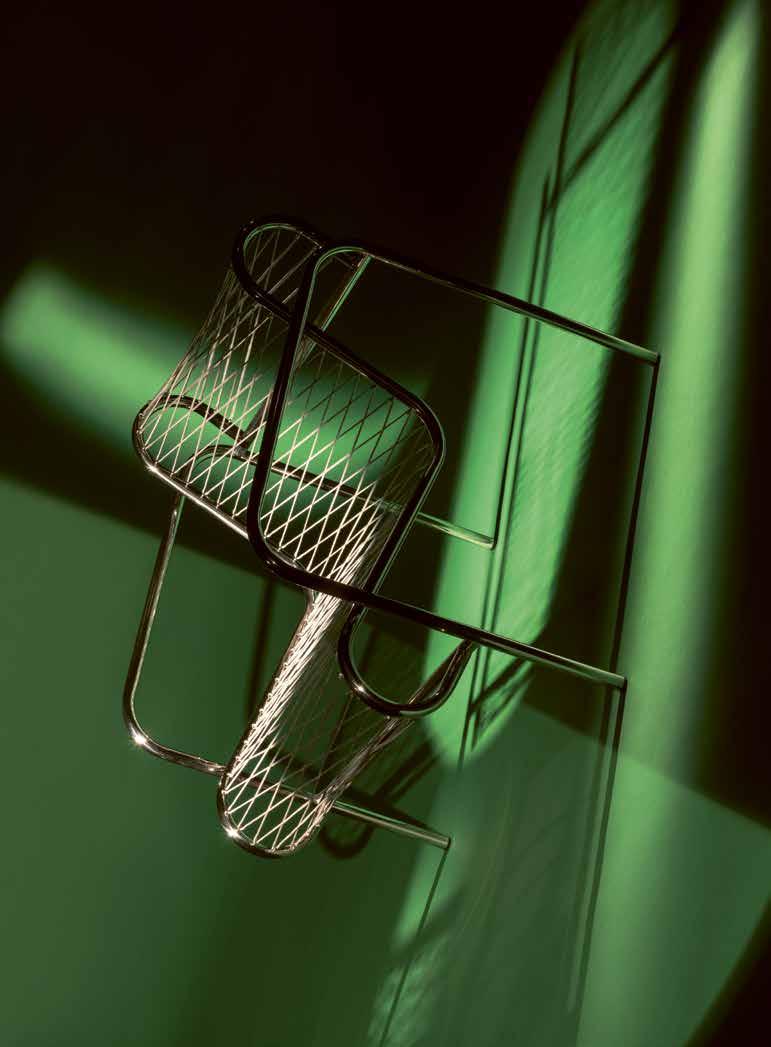

l is by Vitra

TWIGGY SEATING SYSTEM | RODOLFO DORDONI DESIGN DISCOVER MORE AT MINOTTI.COM/TWIGGY

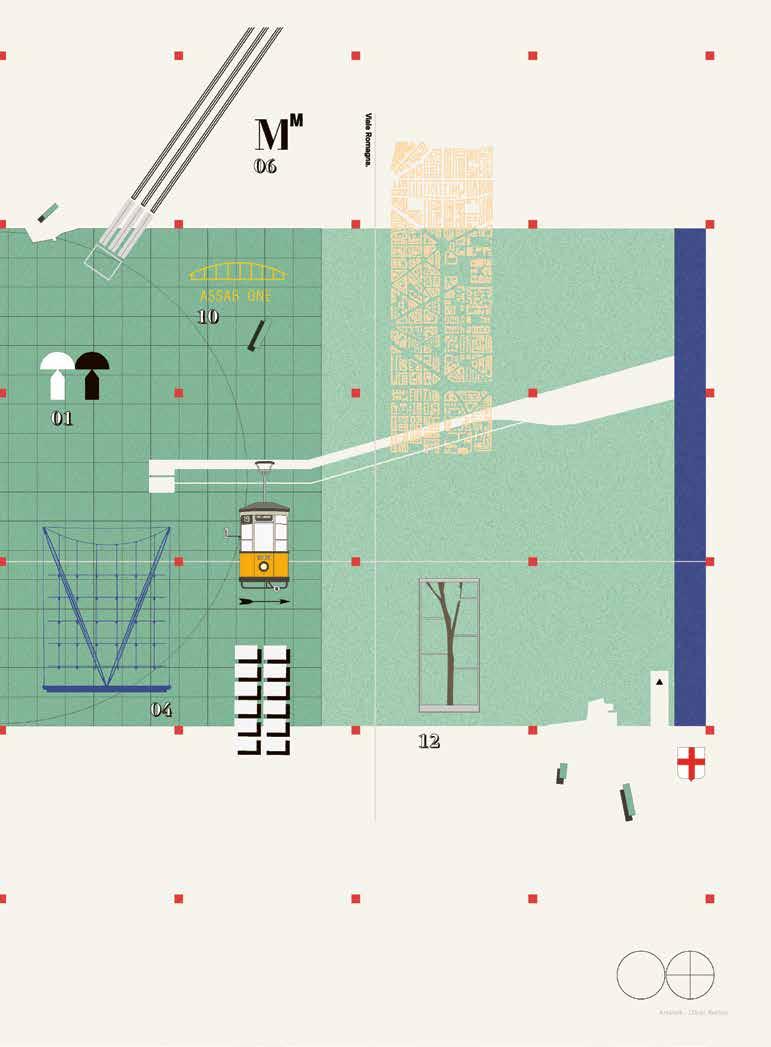

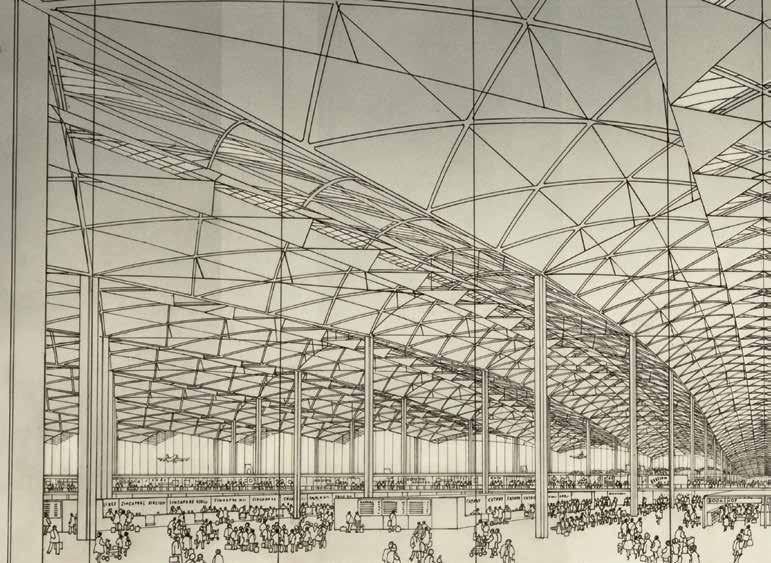

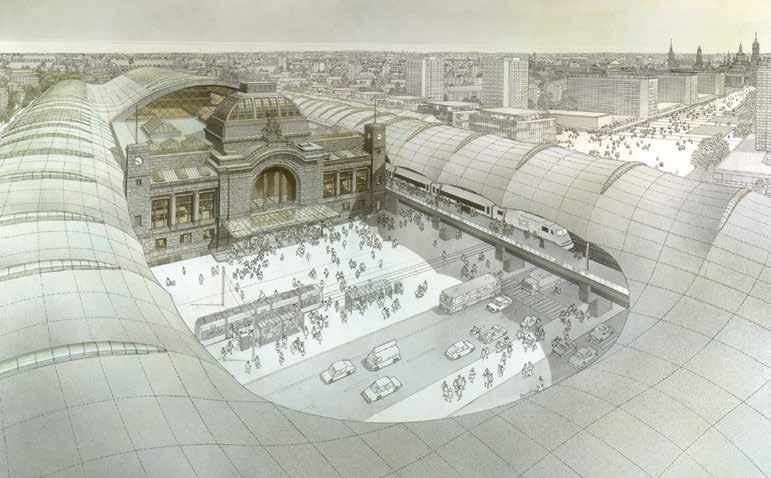

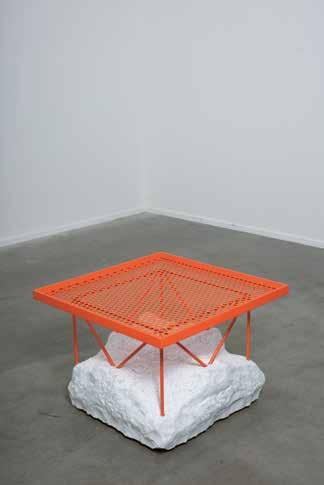

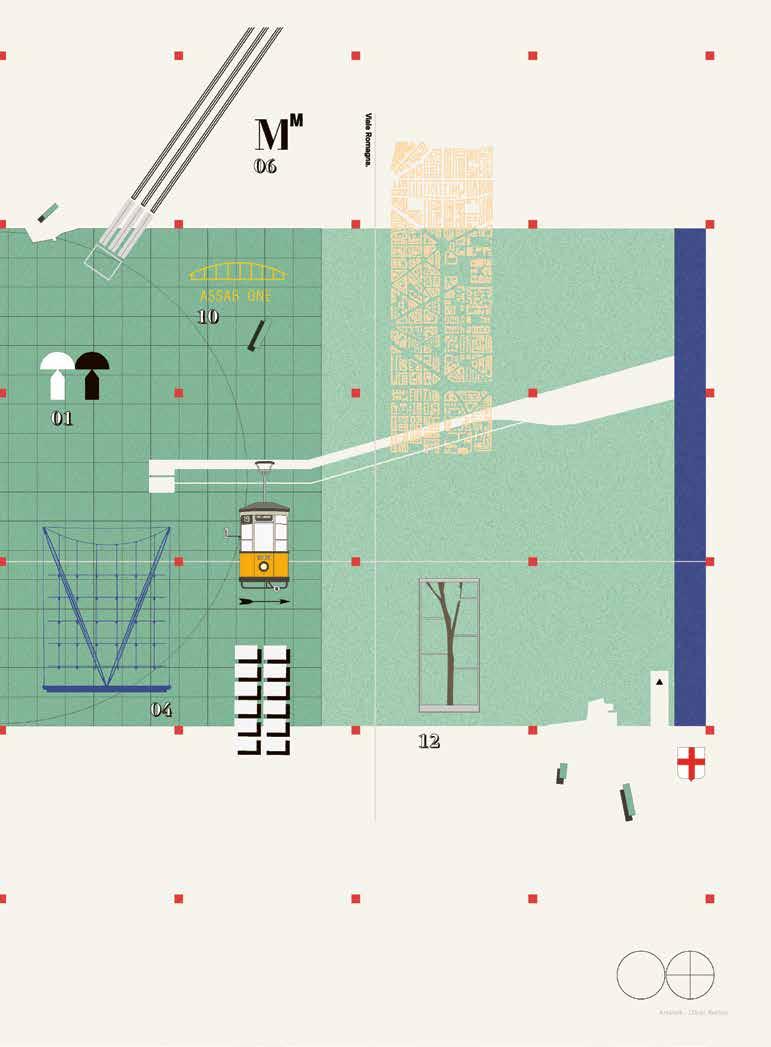

CONTENTS 24 30 34 36 44 50 68 70 78 88 96 106 112 118 120 134 144 146 154 160 164 168 Jony Ive is inspired Architectural intervention Age of analogue The Olivetti legacy Tom Dixon in full bloom Learning from Lausanne Molteni moves outside What are design museums for? Future gazing with Vitra He abbreviated trees Notes on Reflection Sustainably expanding the edges of the object Double portrait Is this the world’s first piece of architecture? Mirror mirror Talking Chairs Milan map Magistretti, Albini, Castiglioni & Ponti Everyday design language The art of the chair Assab One Why Andrea Branzi matters

MOLTENI&C FLAGSHIP STORES LONDON SW3 2EP, 245-249 BROMPTON ROAD / LONDON WC2H 8JR, 199 SHAFTESBURY AVENUE moltenigroup.com

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Dan Crowe

EDITOR Deyan Sudjic

DEPUTY EDITOR Tom Bolger

DESIGN Fran Méndez, Maria Vioque Nguyen

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER Andrew Chidgey-Nakazono

PHOTOGRAPHY DIRECTOR Naoise O’Keeffe

PHOTOGRAPHY EDITOR Jodie Michaelides

SENIOR EDITOR Kerry Crowe

INTERIORS EDITOR Serene Khan

SUB-EDITOR Sarah Kathryn Cleaver

WORDS

Glenn Adamson, Leonie Bell, Tulga Beyerle, Lilli Hollein, Jony Ive, Beatrice Leanza, Justin Mcguirk

PHOTOGRAPHY

Billy Barraclough, Camille Blake, Gina Bolle, Santi Caleca, Thomas Dix, Anselm Ebulue, Alice Fiorilli, Benjamin Freedman, Matthieu Gafsou, Camilla Glorioso, John Gollings AM, Giovanni Hanninen, Jürgen Hans, Florian Hilt, Julie Howden, Hufton + Crow, Akio Kawasumi, Daniel Kukla, Julien Lanoo, Isabella Madrid, Oliver Matich, Marvin Merkel, Angus Mill, Mark Niedermann, Stefan Oláh, Mattia Parodi, Dylan Perrenoud, Henning Rogge, Carla Rossi, Paolo Roversi, Armando Salas Portugal, Paul Smith, Adam Štěch, Diana Tinoco, Max Zambelli,Andreas Zimmermann, Gerald Zugmann

ARTWORK

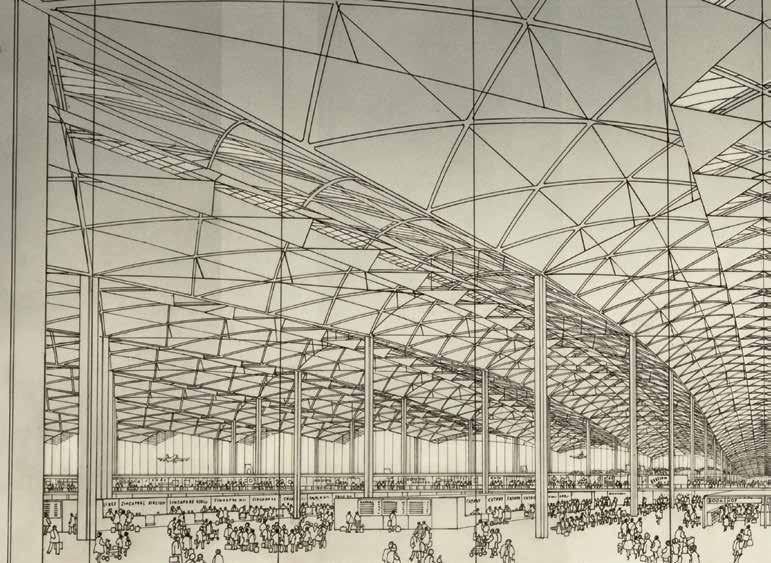

Oliver Burton, Kate Copeland, Helmut Jacoby

PUBLISHER Dan Crowe

ADVERTISING DIRECTOR

Andrew Chidgey-Nakazono andrew@port-magazine.com

CONTACT

Tom Bolger thomas@port-magazine.com

TYPEFACE

At Aero and At Haüss Mono designed by Pedro Arilla, available at Arillatype.Studio® Bradford designed by Laurenz Brunner, available at Lineto Foundry Gridnik™ designed by Wim Crouwel, available at Linotype

Anima is printed by Park Communications www.anima-magazine.com

020

MASTHEAD

TABLE OPENUP | NIK AELBRECHT CHAIRS NEWOOD LIGHT | BROGLIATOTRAVERSO VASES TRACE | FRANCESCO FORCELLINI cappellini.com CAPPELLINI UK 150 St John Street EC1V 4UD - London T. +44 (0)20 8150 8764

It was in December of last year that Dan Crowe, Port’s editor and co-founder, asked me if I would be interested in working on a new magazine that focused on all aspects of design. Of course, I was always going to say yes. Design is a subject that has fascinated me since I first read Reyner Banham, who wrote about the meaning of clipboards, or the “power plank”, as he called it. Design, as I have always seen it, is a way to understand the world around us. But given its significance, it is a subject not as well served in print in English as it might be. Milan – where I once edited Domus magazine – even today in the face of the great digital flood, still has half a dozen titles covering design.

The special qualities of a magazine, with its mix of voices and images, the tactile quality of paper, and its ability to tell a story in a way that no other medium can match, ensure that it is a format that retains its relevance.

I’d been writing for Port over the past couple of years, and I had got to know it as a magazine with an engaging personality and a strong graphic identity. It was a great starting point for Anima. Dan has conceived several magazines, and I’ve been in at the beginning of a couple myself: Blueprint, which I launched and which had a good run, and Eye, which continues to thrive. What seemed right for these times, which are so different from the climate in which Blueprint began, is a format which allows for both insightful, engaging writing, beautifully designed pages and creative photography and imagery, as well as podcasts and live events.

The name is Italian for soul. It suggests exactly what we aim to do: go beneath the surface, to look at how things happen and what they mean.

For this first issue we went to Australia to find what may be the world’s oldest work of architecture, and to Lausanne to explore the work of a new generation of designers. We explored the lessons today’s corporations have to learn from the example of Olivetti. We spoke to Jony Ive about the things that inspire him, and to Norman Foster about the significance of drawing. Lilli Hollein, Tulga Beyerle, Beatrice Leanza and Leonie Bell all reflect on the purpose of design museums. We met Tom Dixon, Rolf Fehlbaum and Andrea Branzi, and asked Paul Smith to photograph his analogue tech collection for us. We haunted the factories and studios of Milan and discovered the artist designers working in the grandeur of Chatsworth House. And Justin McGuirk, from the Future Observatory, writes about the potential of design to address the climate emergency.

Fran Méndez and Maria Vioque Nguyen have designed Anima beautifully, whilst Naoise O’Keeffe put an inspiring group of photographers together. The team from Port have put it all together with wit and style. All of us hope that you will enjoy reading it as much as we have making it.

– Deyan Sudjic

022

EDITOR'S LETTER

www.baxter.it

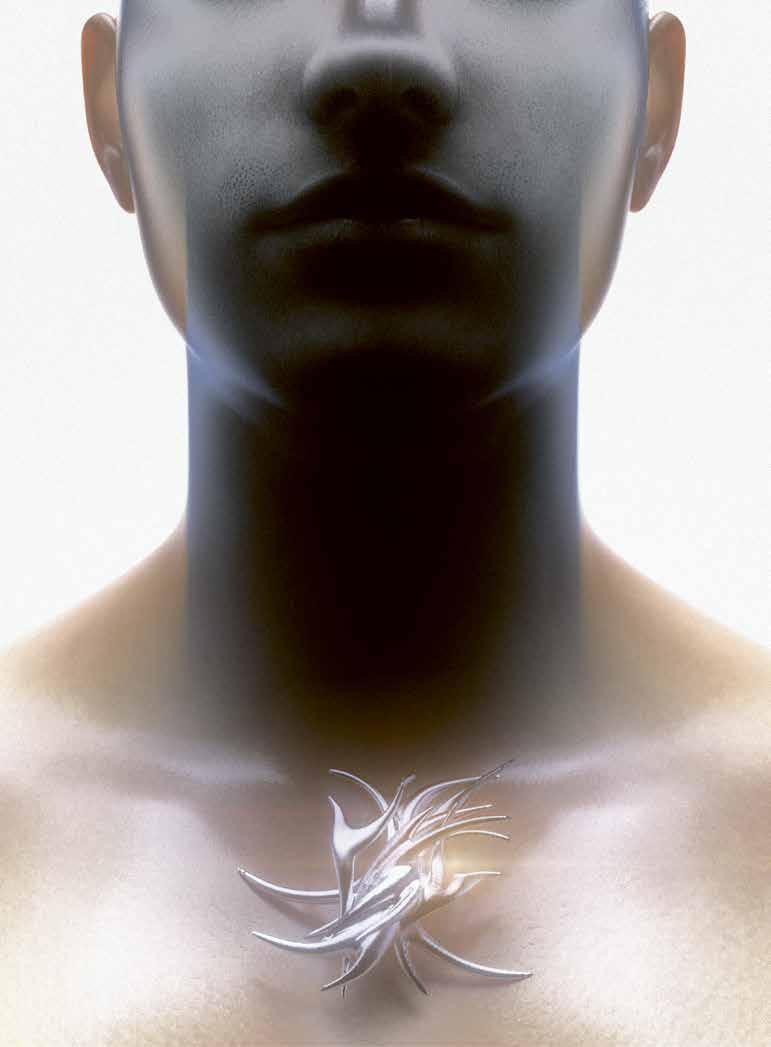

Jony Ive

No designer has done more to change the way that we all live than Jony Ive, Apple’s former chief design officer. He describes to Anima five things that have brought inspiration to his work

is inspired

024

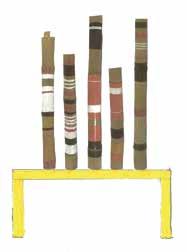

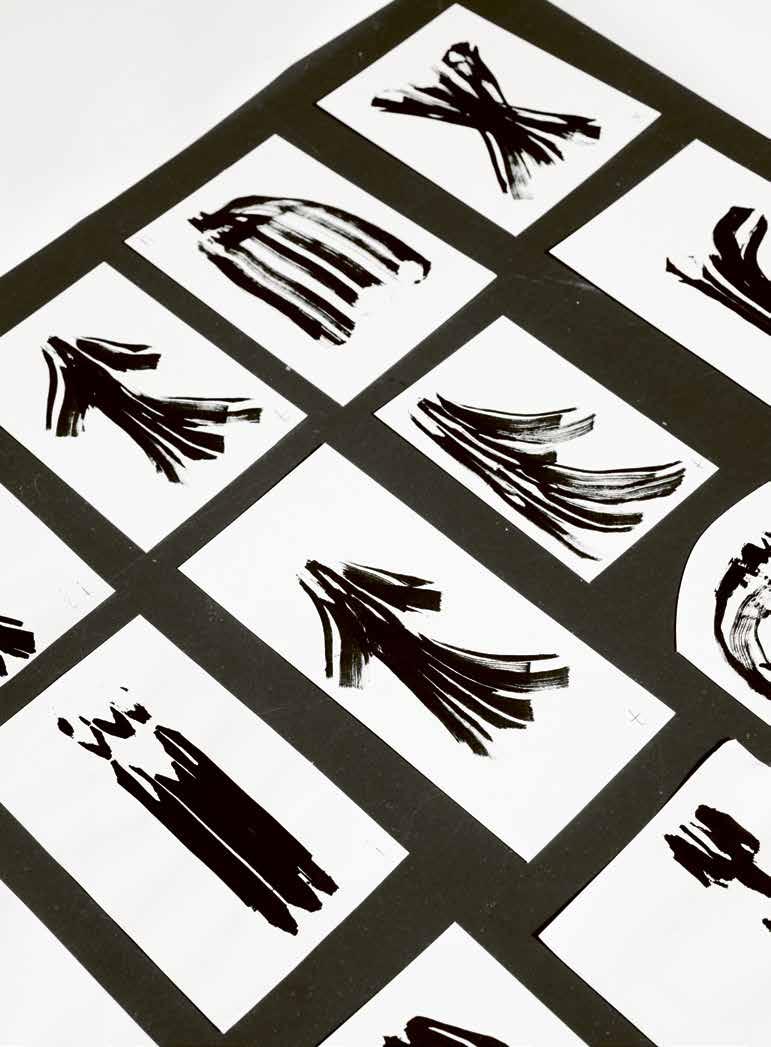

WORDS Jony Ive

ILLUSTRATIONS Kate Copeland

I always carry a handkerchief.

I can think of few more useful or functional products that have evolved over decades to become so beautiful and distinct, while remaining so essential and simple. Over the years I have collected and been given dozens and dozens of cotton squares. I have drawers full of colourful, neatly folded handkerchiefs that are unfailingly cheerful.

There are not many items I own that survive daily use for so many years. While they see blood, sweat and tears, it is rare I throw one away — far more common is producing a fresh and clean handkerchief for a friend who was caught unprepared in a moment of need. I love that it will never be returned but will become their own.

025

Handkerchief, cotton, hand rolled edge, 46 cm x 46 cm, made by Hermès, Paris

Almost everything I have designed has been done sitting in a Supporto. I have been a fan since the late ’80s. I have them at home, had them at Apple, and now, we have them at my design firm LoveFrom.

I struggle with most task chairs. They seem rather patronising to me, appearing so absurdly complex as if designed to satisfy the most extraordinary requirements.

Supporto is different. It is rational, sophisticated and refined. It gives you as much freedom to move as it does support to focus.

Fred Scott was a brilliant designer. He studied at the Royal College of Art in the early ’60s and it is a shame that his talent is not more broadly recognised. I regret that I never met him.

026

Supporto work chair, designed 1976 by Fred Scott for Hille, now manufactured by Zoeftig, Bude, Cornwall

I have worn Wallabees since I was at college in Newcastle in the ’80s. They somehow seem to exist outside of time and fashion.

I wear them pretty much all the time — with suits or with sweatpants.

They are supremely comfortable, which is important, as I have challengingly wide feet.

I have been obsessed with shoemaking for years and have had formal shoes made by the remarkable George Cleverley in The Royal Arcade. Shoes are a wonderfully ancient and fascinating product category that recently was profoundly disrupted by the sneaker. Trainers feel like SUVs to me. The innovation and functionality provide benefits even if you don’t exploit their total capability.

Wallabees have the functional advantages of trainers, but they are still shoes. They are the original Land Rover Defender, rather than a contemporary SUV.

I love the suede, the crepe sole and moccasin stitching. I love that you understand how they are made. I love that they have the perfect number of lace holes. Wallabees are perfect.

027 JONY IVE

Wallabee shoe, suede uppers, crepe soles, made by Clarks of Street, England, since 1967

Longcase ‘grandfather’ clock, based on Robert Hooke’s anchor escapement mechanism, original design by William Clement in 1680

Timekeeping is surely a forgivable obsession. I have become increasingly fascinated by the technology and the products that have been developed to keep time. This fascination culminated in our work on Apple Watch.

While I like examples from all timekeeping product categories, I have a particular affection for a longcase clock that I have in the hallway of our home in San Francisco.

Beyond how beautifully it was made, and its exceptional timekeeping, this grandfather clock has a comforting place in the house that is hard to articulate. Perhaps it is the anthropomorphic size and proportion, or perhaps the gorgeous tick-tock and hourly chime. This clock has a calm and otherworldly presence that I adore.

The technologies of timekeeping have defined cultures and societies. The gentleness and humanity of this clock’s design belies those unimaginably powerful technologies.

028

Bridges seem to exist in a design and architectural category uniquely their own. Their ambiguity as structures or buildings or products is curiously at odds with how singular and distinct their symbolism and function. If I could pursue the focused study of just one area over the coming years, bridges would be a strong contender.

While they serve a clear and understandable purpose, their gravitas, their call to attention, seems compelling, fundamental, almost primal.

There are only a few bridges that I do not like and there are many that leave me speechless.

While magnificent, ambitious and tenacious bridges can define cities and entire regions, I also find the simple, modest stone bridges of the Cotswolds equally compelling. There is a small bridge that crosses the River Coln at Ablington that is integrated into the adjacent dry stone walls that I truly love.

Whether sitting on it at the end of a hot day in June, or walking along the river and catching glimpses of it through the willow, I find it utterly complete and reassuringly beautiful.

029

Coursed and dressed limestone bridge over River Coln at Ablington, with two segmental arches, early 19th century

Architectural

n t e r v e n t i o n

030 i

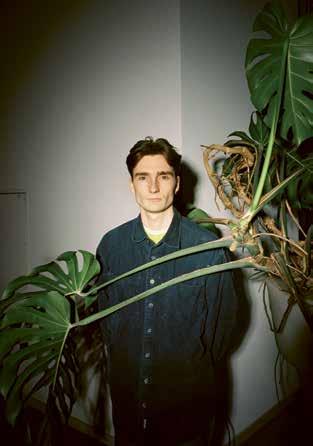

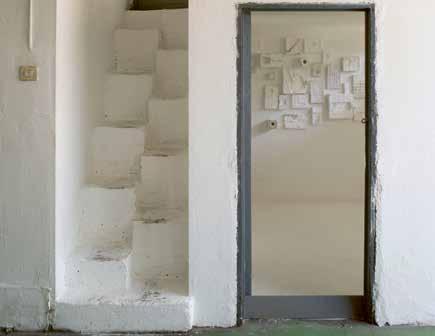

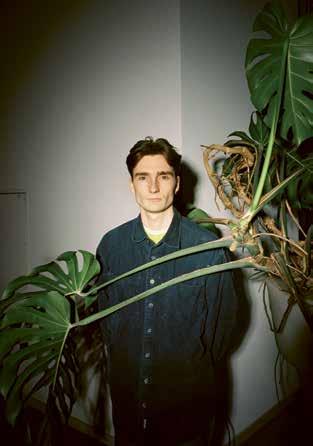

WORDS Deyan Sudjic PHOTOGRAPHY Adam Štěch

Adam Štěch’s self portrait (Above)

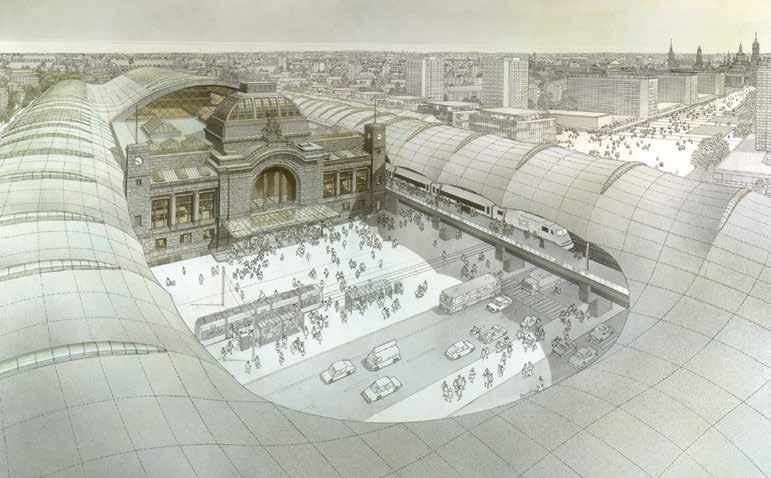

Adam Štěch spent a remarkable 16 years working on a project that he finally published two years ago as a book unpretentiously titled Modern Architecture and Interiors. As a writer, an editor and a curator, he was doing plenty of other things at the same time. He had started a magazine called Okolo in Prague with two Czech graphic designers. He was working on an editorial project with Camper in Majorca. He exhibited a photographic collection titled ‘Objects of Refinement’ at the London Design Festival. At the same time, he managed to visit 29 countries and photograph 900 works of architecture for the book. Its sheer scale is maybe what made one reviewer describe it as “the definitive guide to modern architecture.” In fact, what makes it interesting is that it is anything but that. It is far from a definitive account. It is above all a highly personal, not to say idiosyncratic point of view. It’s not quite Tom Stoppard’s famous take on Shakespeare and Hamlet as seen through the eyes of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, two of the minor characters. But it’s certainly more about mavericks, such as the homespun American Bruce Goff, and the assorted Belgians and Latin Americans that Štěch gets excited about, rather than a conventional measured account of the 20th-century and a familiar path from Otto Wagner to Frank Gehry by way of the Bauhaus and Le Corbusier. Of course, it’s also the take of a critic born in the 1980s, and so the product of a generation not prepared to take received opinions about the relative importance of architectural reputations on trust.

031

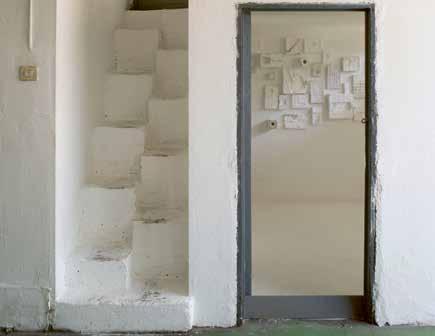

At once comprehensive and highly idiosyncratic, Adam Štěch’s monumental project saw him photograph nearly a thousand works of modern architecture. Anima examines one of his examples, the Parisian home of Valentine Schlegel, the spatially disruptive artist from Sète

The thrill of the chase is something Štěch enjoys. The 900 entries in his book are his personal trophies. He cherishes the sense of triumph that comes when he gets access to yet another interior that nobody has photographed for 50 years. He compares it to an earlier interest that he had in BMX racing and other extreme sports. He has used every tactic, from personal contacts to letter writing campaigns to beg for permission, and on occasion, simply knocking on doors. His Czech roots give him a head start in central Europe’s slightly melancholy, homespun modernism, but the book is none the worse for it.

Valentine Schlegel is certainly somebody who does not fit conventional stories about 20th-century architecture. She was not an architect, even if she made what could be described as architectural interventions, shelves and mantlepieces and panelling that she and her assistants and collaborators applied to the walls of existing buildings, disrupting their spatial qualities. She did however believe in the usefulness of objects, and so can be described as a designer. She was essentially an artist born in the little Languedoc port of Sète in southwestern France. Schlegel grew up on the beach, in a family with a tradition of craftsmanship and a passion for making, against the background of casually built white-walled seafront cafes and self-built homes that seem to have influenced some of her work.

032

Štěch doesn’t claim to have discovered Schlegel. Even though she spent much of her life between Sète and Paris, Schlegel was close enough to the centre of gravity of post-war French culture not to be neglected on the basis of her gender, her provincial roots, or of her preference for the plastic decorative arts. She met Agnès Varda – the pioneer of French New Wave cinema – in Sète when they were still teenagers and they remained close friends. In 1954, Varda asked Schlegel to work on her first film, La Pointe Courte, shot in a fishing village close to their childhood homes. No less an influencer than the film star Jeanne Moreau was a client — she commissioned a distinctive interior that is one of the most recognisable works from her career as a ceramicist and sculptor. Before her death, her work was the subject of two exhibitions organised by Hélène Bertin, an artist and a curator.

A student of drawing, for many years Schlegel relied on teaching to support herself and her stream of creative production. She used her craft skills to hand-carve utensils and bowls from mahogany, and make leather bags and sandals.

Schlegel, who contemporary photos suggest dressed in the epitome of Latin Quarter chic in striped jerseys and sailor’s trousers, lived with Yvonne Brunhammer, who worked as a curator at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris and subs quently was its director until 1991. The museum in the wing of the Louvre on the rue de Rivoli is an institution that supported Schlegel through much of her career. The impact of Brunhammer’s own work as a curator on her partner would make a useful study. Brunhammer put on exhibitions on a series of architects who included van de Velde, Gaudi, Guimard and Horta, all of them interested in a subversion of surface and form that could be seen as offering precedents for Schlegel’s spatial dynamics. Intriguingly, in one of Štěch’s photographs of Brunhammer and Schlegel’s home a Shiro Kuramata table designed for the first Memphis collection is visible.

Štěch managed to photograph the home in Paris that Schlegel had shared with Brunhammer since 1976 before its contents were sold in an auction of their effects after their deaths within months of each other. A pair of cast fire irons reached more than €80,000.

033

Age of analogue

Paul Smith

A dive into designer Paul Smith’s retro-tech world, playful mementos of what the modern used to look like

In among the snowdrifts of cycling jerseys, cliffs of books and magazines, tin toys, cameras and ornamental rabbits, one strand of Paul Smith’s ever-multiplying collection of collections is an assortment of analogue-era artefacts. Despite having been made technologically redundant by the digital explosion, they remain a powerful reminder of what the modern world used to look like.

The analogue signals that would once have brought the original Algol 11-inch portable TV set (designed in 1964 by Marco Zanusso and Richard Sapper) to life, have been switched off now. Although such is its charm that Brionvega now makes a set with modern electronics inside the moulded plastic shell. It belongs to the early days of transistors and cathode ray TV tubes and was designed as a portable object, rather than a piece of furniture, as larger television sets were still seen at the time. Zanusso was a distinguished architect, while Sapper went on to design the famously distinctive Tizio desk light, and the Think Pad, IBM’s first laptop computer.

What made the Algol so cute is the way that the up-turned screen not only makes for easier viewing when it’s placed on the floor, but as Zanusso once suggested, it resembles a pet dog, looking expectantly up at its owner.

Italy’s designers have a long history of giving machines a personality. That goes back to the oldest radio in Smith’s collection, the Phonola, designed in 1940 using moulded Bakelite by Livio Castiglioni.

And it was another Italian designer, Mario Bellini, that Yamaha asked to put his signature on the distinctive wedge-shaped cassette deck that for a moment seemed like the last word in music technology.

Part of the reason for Japan’s temporary domination of the world market in consumer electronics was the strategy adopted by Sony to use a strong design language, or rather multiple languages. Matt black was intended to signal precision and reliability for its short-wave radios, yellow was associated with sport. It was also happy to adopt a much gaudier range of colours aimed at attracting attention to its users. Its competitors, especially Pioneer, responded with their own versions.

034

PHOTOGRAPHY

RETRO TECH COLLECTION

(A)

(A)

(C)

(D)

(E)

(B)

(B) (D)

(E)

(C) Phonola radio, Livio Castiglioni

Algol 11-inch portable TV set, Marco Zanusso and Richard Sapper

Yamaha cassette deck, Mario Bellini

Collection of Panasonic and Sony devices, complete with Van Morrison cassette

Toy dog looking at Algol 11-inch portable TV set

The Olivetti legacy

From ingenious typewriters to innovative computers, charting the rise and fall of the singular company whose commitment to architectural and design culture was matched only by its investment in its employees and Italian society

ALL IMAGES COURTESY

036

WORDS Deyan Sudjic

Associazione Archivio Storico Olivetti, Italy

Olivetti Programma 101, recognised as the first desk top computer, engineered by Pier Giorgio Perotto and designed by Mario Bellini in 1965

(Above)

Three generations of the Olivetti family built a company with a unique combination of engineering brilliance, social obligation, and entrepreneurial ambition, which has now all but vanished. In 1970 it employed almost 75,000 people in factories from São Paolo in Brazil to Glasgow in Scotland. In 2022, the number was fewer than 300.

Camillo Olivetti, the founder, returned home from Stanford to establish Italy’s first typewriter factory in 1908 in the company town of Ivrea, near Turin. His son Adriano took over leadership during the Fascist era and went into exile in Switzerland when Mussolini began deporting Jewish Italian citizens. In the years after World War II, Adriano expanded the company hugely, taking over Underwood in the USA, and with his son Roberto built one of the first all transistor mainframe computers, the Elea 9003. The name, both an acronym and the name of an ancient Greek Italian colony with a pre-Socratic school of philosophy, suggests a very particular corporate culture.

Adriano Olivetti invested not just in the welfare of his own employees, but of wider Italian society, supporting the reestablishment of democratic culture and politics. Olivetti offered its workers generous welfare provisions that included company nurseries, libraries, cafeterias, hospitals and a holiday resort. Adriano’s sudden death on the Milan Lausanne express at the age of 60 left the company over-extended and leaderless at a critical moment.

Decline and Fall

Three different CEOs succeeded Adriano in four years. Underwood failed to meet its financial targets. Olivetti struggled to sell enough Elea machines to recoup its investment and was bailed out in 1964 by a consortium of Italian banks working with Pirelli and Fiat. A condition of the transaction was the sale of the loss-making Elea programme. General Electric, which had already taken over the French computer firm Machines Bull, bought it, an early sign of European manufacturing vulnerability. Even so, Olivetti remained an exceptional company. It still had the Programma 101, an impressively powerful desktop-sized computer. The company went on investing both in the welfare of its workforce, and in its industrial plant. It opened a modern factory designed by Marco Zanuso in Scarmagno, mid-way between Ivrea and Turin, that started by manufacturing teleprinters, and later built personal computers. The striking La Serra Complex in Ivrea – complete with hotel and cinema – opened in 1976, reflecting Olivetti’s unwavering commitment to both architectural culture and the well-being of its employees.

But the company’s finances went from bad to worse in the 1970s. For more than a year before Carlo De Benedetti became CEO in 1978, Olivetti’s losses had been running at an impossible $10m every month, equivalent to $50m in 2022. De Benedetti had cut 20,000 jobs by 1984 and axed another 7,000 over the next six years. However, he still found the capital to

invest in promising new businesses: he bought Acorn, the manufacturer of the successful BBC Acorn personal computer in Britain, and a banknote-counting business in America. He tried to raise more capital by partnering with AT&T and selling parts of Olivetti to Hewlett Packard. But in the end, like all the rest of Europe’s computer hardware manufacturers, from Bull in France to ICL in the UK, it seems that whatever strategy Olivetti tried, there was nothing it could do that would allow it to survive in its original form. In the long run, it was only IBM that was able make the transition from hardware to software.

The conventional wisdom about the rise and fall of Olivetti is that it represents a simple and familiar story. Just like Kodak and Polaroid, one of the world’s most admired industrial companies of the analogue age failed to predict the impact that the digital explosion would have on its future. In Olivetti’s case, this myopia led to the murky financial engineering that left it as the shrunken and faded division of an Italian telecoms business, reduced to putting its branding on point-of-sale devices manufactured in Asia. But the story is not so simple. The company had opened a research centre in Cupertino in 1979 and was well aware of what was going on behind the garage doors of Silicon Valley’s start-ups. It’s not that Olivetti didn’t see what was coming, but it made some missteps and fell victim to the random accidents of the early mortality of some of its most important leaders. It had difficulty adjusting to the quickening pace of product development in the digital age. Between three and five years might have worked when it was making technically superior mechanical calculators, but it was far too slow when it was trying to make printers that could compete with Epson. And then it ran out of capital. The end came when an ambitious CEO used Olivetti to leverage a loan to buy Telecom Italia in 1999, a company five times its market value. He sold Telecom’s most valuable property, its mobile phone network, leaving Olivetti with all the debt and as he himself said, becoming personally extremely wealthy.

Making the Product

The network of Olivetti factories and technical offices in and around Ivrea in 1970 was the personification of an industrial system that seemed like the height of modernity at the time, but which is now extinct. There were machine shops and presses, there were assembly lines, maintenance shops, and warehouses. There was an office that worked on nothing but typefaces for all of Olivetti’s typewriters.

At its height, Olivetti employed 12,000 workers in Ivrea: skilled tool makers, draftsmen and technicians, but also physicists and engineers, and nursery schoolteachers and marketing men. There was a functioning foundry, working with hand-carved wooden moulds that they needed to sand cast aluminium parts for Marcello Nizzoli’s Lettera typewriters, techniques that are now mostly only used by artists such as Jeff Koons, rather than in factories. The components

037

would be hand finished, and then enamel painted in an oven. Ettore Sottsass’s Tekne 3 electric typewriter depended on aluminium extrusions demanding the use of more elaborate, and costly tools than sand casting.

Starting out as a typewriter manufacturer, Olivetti’s engineers produced sophisticated four-function mechanical calculators, built one of the first all-transistor mainframe computers, and have a plausible claim to be credited with the earliest desktop computer.

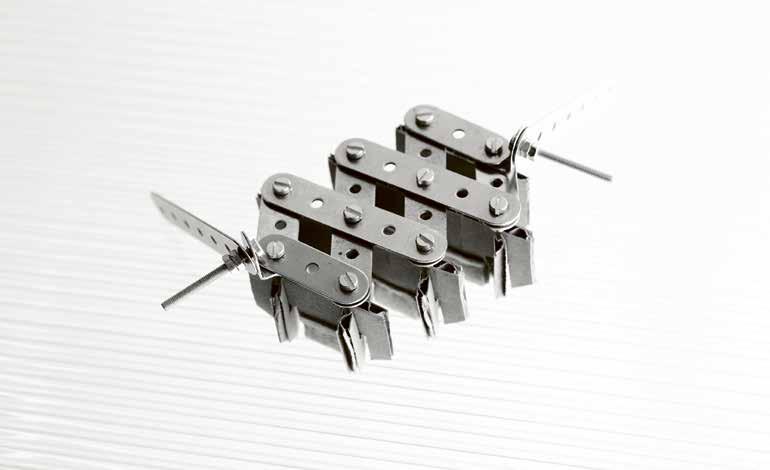

Following in the footsteps of Charles Babbage’s difference engine, Olivetti’s most elaborate mechanical calculator – which could add, subtract, multiply and divide – used an electric motor to drive an intricate web of 1,500 components. It was the product of 50 years of continuous development that began with the original Olivetti typewriter.

Each new model built on what had gone before. The company made its first adding machine in 1940, which required the user to push a manual lever to execute every step of a calculation. A new version with the capacity to store a limited number of equations mechanically, a memory in fact, came in 1949. It had a joy-stick control to engage options such as whole number only calculations. Olivetti introduced an electric motorised model in the 1950s which printed a record of every step of the calculation on a built-in roll of paper, black for addition, red for subtraction. These were remarkable machines that commanded premium prices, and which remained in production for a long time. As a result, they were highly profitable.

Press a typewriter key, and it does nothing much more than prompt a mechanical arm to strike an inksoaked fabric ribbon threaded between two spools, leaving the impression of a letter as a mark on a sheet of paper. As the key falls back into place, it pulls the ribbon a little way forward to avoid wearing it out with continued strikes in the same place. Press the = key on a Divisumma 24 on the other hand, and a whole sequence of things happens, of which a printed record of every stage of the calculation is perhaps the least complex. A mechanism as intricate and precise as that of any watch pushes, pulls, and clicks the cogs and levers into place to provide the numerical answer to the series of mathematical questions that the sequence in which the buttons are pressed represents. Inside the smooth cast aluminium skull that Nizzoli designed for the Divisumma 24 is an intricate metal brain, as beautifully engineered as an 18th-century orrery. To build it demanded skills that the world has now lost, an entire factory, and such pre-existing units as the printing mechanism, based on typewriter components. The problem in the long term was weaning Olivetti off its dependence on mechanical engineering, given the generous mark-up it had once been able to charge for its products. A mechanism as complex as the Divisumma 24 required a high level of maintenance. According to Ottorino Beltrami, the senior Olivetti engineer who defied the protests of his staff

and cancelled the company’s mechanical programme in the 1970s in favour of electronics, the cost of maintenance of a mechanical calculator over two years was higher than buying an electronic calculator outright from one of its Japanese competitors. Sottsass and Hans von Klier designed Olivetti’s last mechanical calculator, the Summa 19, in 1970. Within two years it was supplanted by the Divisumma 18, designed by Mario Bellini. Its famous tactile buttons covered in a bright yellow synthetic rubber announced that everything had changed. Inside the ABS plastic case there were no moving parts, just a pair of circuit boards.

The complexities of making a computer and the sheer scale of the investment required are such that it is all but impossible for a designer without an intimate and long-term relationship with their client to make more than a cosmetic contribution.

Yet in their nature, creative designers are not naturally drawn to the idea of becoming corporate employees based in out-of-the-way company towns like Olivetti’s HQ in Ivrea. The Olivetti strategy from the time of Adriano’s leadership was to embed designers within the company, but at the same time to give them the independence they needed to bring other experiences to its products. It simultaneously supported Sottsass and Bellini in their own studios, as it had previously done with Nizzoli, as independent consultants with their own teams and studios in Milan, 100 km from the factories and management offices in Ivrea.

The company allocated technical draftsmen to Sottsass and Bellini who worked in their studios, and it maintained a liaison office in Ivrea. It was an arrangement that allowed designers immersion within the organisation, but also the independence to cross-pollinate Olivetti with their experiences with other clients. It wasn’t like that for Jony Ive when he was at Apple.

Sottsass became a consultant for Olivetti when he started to work on the Elea 9003 mainframe in 1957. From the beginning he had explored the symbolic and emotional meanings of objects as well as their functional characteristics. “What should a computer look like?” he had written in his notebook. “Not like a washing machine.” he wrote in answer to his own question. If anybody was showing the new direction that design could take after modernism it was Sottsass. It is inconceivable that a functionalist could have posed the problem of designing a new category of machine in such terms. But as if to demonstrate his mix of rigour and poetics, he commissioned Tomas Maldonado and a team from the Ulm design school, whose approach was regarded as the embodiment of the post-war version of Bauhaus functionalism, to produce a study for an ergonomic keyboard layout for the Elea. Sottsass had designed a series of typewriters, famously the Valentine that came in a choice of colours of which red was the most memorable, the electric portable Lettera 36 and an office machine, the Praxis 48.

038

039

Advertising poster for the typewriter Olivetti Lettera 22 by Giovanni Pintori (’50s)

(Below)

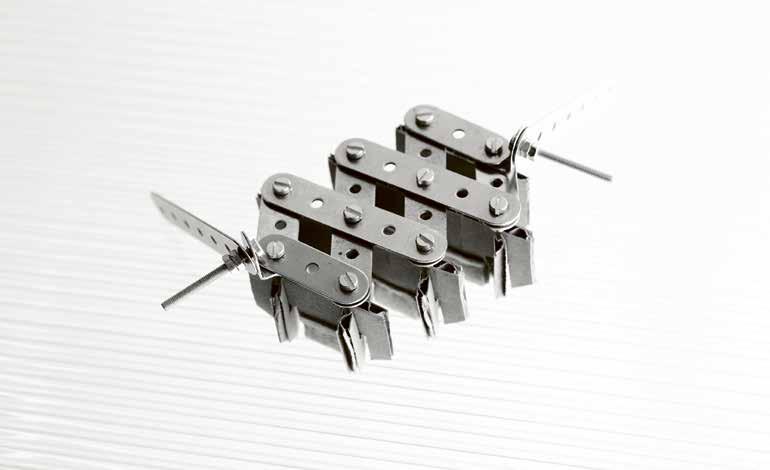

Electromechanical calculator Olivetti Logos 27 (without its bodywork) designed by Teresio Gassino in 1965

Electronic computer Olivetti Elea 9003 central console; the first large calculator produced in Italy and the first completely transistorized in the world (1959)

(Left)

(Above)

040

Expansion of the ICO workshops in Ivrea (Turin) built between 1939 and 1949 by the architects Luigi Figini and Gino Pollini

(Middle) (Left) Olivetti Technical Centre and Warehouse in Yokohama, Tokyo, designed by Kenzo Tange in 1970

041

Testing department for the electric typewriter Olivetti Tekne 3 in Scarmagno, Turin (’60s), photography Rolly Marchi / Aemme Studio

(Right)

He worked with two designers who were themselves inheritors of the Bauhaus tradition. Perry King, credited as his assistant on the Valentine, had been taught as a student in England by a Bauhaus master, Naum Slutzky. Von Klier, Sottsass’s assistant on the Praxis 48, was an Ulm graduate.

For Walter Gropius and Hannes Meyer, his successor as the director of the Bauhaus, form was the inevitable outcome of rigorous analysis, stripped of emotions or sentiment. That was not how Sottsass, who had pursued a parallel career as an artist since his student days, saw it. Even as he worked on Olivetti’s technically exacting projects, he was designing objects for craft production, in ways that looked to expand the meaning of design beyond the production line.

Sottsass’s staff included the Canadian designer Albert Leclerc, previously an assistant to Gio Ponti, Masanori Umeda, Koichi ‘Tiger’ Tateishi (a brilliant Japanese artist who illustrated Planet as Festival, Sottsass’s utopian dream for a post-industrial future), George Sowden and Jane Dillon from England, and Bruno Scaglioli. It was a determinedly international group, while Mario Bellini’s studio relied mainly on Italians. Each studio’s work had its own signature.

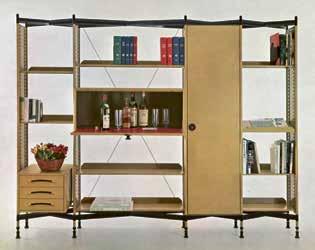

As well as working on large-scale machines, Sottsass’s team was developing Olivetti’s Synthesis 45

office furniture range to take the place of BBPR’s earlier design. Another presence in the office was Clino Castelli who had previously worked for Sottsass as an assistant and would return from time to time to provide long, drawn out half-philosophical, half-scientific presentations to find reasons to introduce new colours to the company’s palette that went beyond universal Olivetti grey. Between them they represented the two sides of Sottsass’s diverse range of interests. One side of his work was speculative, critical and poetic, the other was rigorously industrial.

There was a room in the studio to make rough models. They were the starting point for more elaborately finished models made by one of Milan’s celebrated specialist model makers, Giovanni Sacchi on the via Sirtori, or else by Ovidio Ribolini. Nizzoli had discovered Sacchi’s carpentry workshop in the 1940s and made use of his remarkable skills as an essential part of his practice. Ever since, an immaculately finished model made from pear wood had been an important part of the process of creating a new product for Olivetti. Before committing to the cost of investing in expensive tooling, Sacchi and Ribolini’s craft skills could create an object that had the authority and presence of the finished object. It gave designers a chance to refine their thinking, and managers the confidence they needed to approve a new project.

“ Some companies sponsor football teams. Olivetti funded Bruno Munari’s 1962 exhibition exploring kinetic art.”

Olivetti showroom in New York designed by BBPR Studio in 1954

(Above)

Sottsass used Ribolini more than Sacchi. But both made exquisite representations of the defining products of Italian industry. Milanese photographers were a significant part of the process too, turning simple preliminary models into evocative images, and making Sacchi’s wooden studies look like the real thing.

Olivetti set a path for culturally sophisticated brand building, and manufacturing charismatic products that was followed at a respectful distance by its competitors, first IBM, then much later by Apple.

Adriano Olivetti appointed his son-in-law Giorgio Soavi, a writer and a close friend of Alberto Giacometti, as the company’s corporate design director. He and Renzo Zorzi, who edited Primo Levi’s first book, led the selection of architects, artists and designers to work for Olivetti. Zorzi, who retired in 1986, was succeeded by Paolo Viti. Louis Kahn built Olivetti’s factory in Pennsylvania. James Stirling designed its training centre in Britain. Carlo Scarpa, Gae Aulenti and Ernesto Rogers did its showrooms. Olivetti employed Richard Meier to design its US HQ in 1971, but cancelled the project. Kenzō Tange’s training centre in Yokohama did go ahead. Milton Glaser and Herbert Bayer designed its posters.

In 1970, Sottsass worked on plans to fit out Olivetti

US’s newly acquired headquarters building in New York as a showcase for the company. Sottsass was asked to produce a design that would be as striking as the company’s first American showroom on Fifth Avenue. This was the famous interior designed by Ernesto Rogers in the 1950s, where Nizzoli’s typewriters, impaled on marble stalagmites, attracted the enthusiastic attention of IBM’s leader, Thomas Watson Jr. He was impressed enough to hire Elliot Noyes to lead IBM’s own corporate design strategy, with Paul Rand and Charles and Ray Eames. Olivetti’s new office building 12 blocks south at 500 Park Avenue, was originally commissioned by Pepsi Cola from SOM’s Gordon Bunshaft, and was one of the handsomest post-war buildings in the city. Sottsass flew to New York with his British assistant where they met Bunshaft. He was characteristically dismissive of their diplomatic overtures to present a sympathetic transformation of the building. “I don’t care if you knock it down,” he told them.

Over a two-year period Sottsass came up with a series of striking proposals, including one that he called the ‘Hippie encampment’, and another that took the form of a garden with a series of clearings. At one point, Sottsass asked George Nelson, the distinguished American designer that he had worked for in the 1950s, to come up with a scheme. Frustratingly, Olivetti chose to implement a much lower profile make-over, and then sold the building.

Some companies sponsor football teams. Olivetti funded Bruno Munari’s 1962 exhibition exploring kinetic art. It paid for the restoration of Leonardo’s ‘The Last Supper’ in Milan, as well as of the four bronze horses from St Mark’s in Venice, and the Cimabue crucifix damaged in the Florence flood of 1966. It sent the horses on a tour of the world’s museums.

Henri Cartier-Bresson was commissioned to photograph Olivetti’s new factory at Pozzuoli overlooking

the Bay of Naples. The factory, Adriano Olivetti said, should serve man, and not the other way around. In his speech at the opening ceremony, he described Luigi Cosenza’s architecture as “conceived to the measure of man, so that he could find in his orderly place of work an instrument of redemption, and not a device of suffering.”

Olivetti production came to an end at Pozzuoli in the 1980s, but it has fared better than the Ivrea buildings, which have lost their purpose. Even though both sites have been declared world heritage sites by Unesco, Pozzuoli is close enough to Naples for the former Olivetti buildings to have found new uses. Adriano Olivetti’s investment in architecture provided the point of departure for a new life for the community.

043

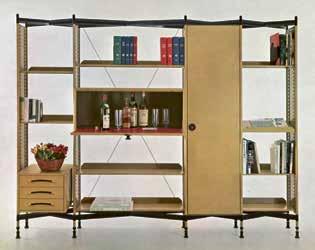

“Spazio” bookshelf produced by Olivetti Synthesis and designed by BBPR Studio in 1960

(Above)

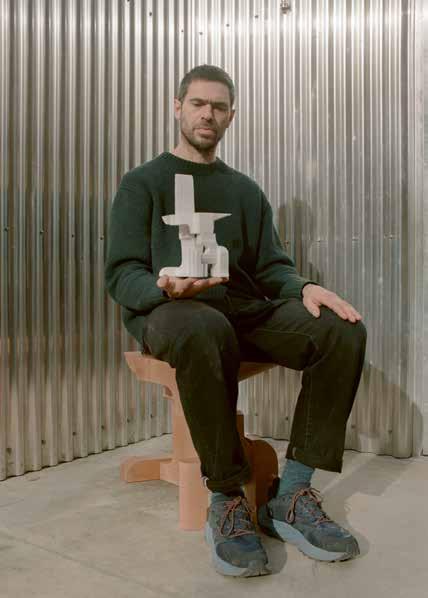

The British designer’s gently subversive work –which spans furniture, lighting, and domestic accessories – combines the gritty and the precious; handcraft with classical design. Anima visits his countryside studio, connected to a historic orchid nursery, to discuss his journey to date

Tom Dixon in full bloom

044

WORDS Deyan Sudjic PHOTOGRAPHY Billy Barraclough

Tom Dixon wears Canali SS23 throughout

045

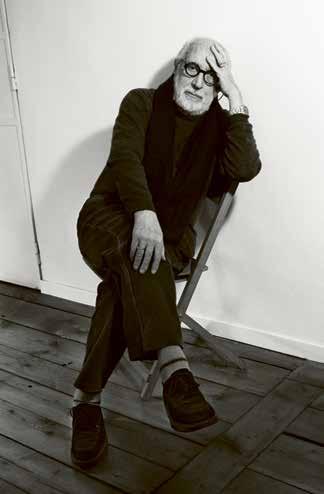

Tom Dixon has done a lot of things, but completing a conventional design education is not one of them. That hasn’t stopped him from becoming one of Britain’s most inventive designers, driven by a continual curiosity, and a disarming ability to make the most out of any material or situation.

There are nine Tom Dixon shops now, four in China, one in Japan, two in Italy and another in New York as well as the flagship in London. In total there are 150 people working for Dixon. It’s a global reach that sends him travelling around the world.

After the session at which Anima’s photographs were taken, he was on the way to the airport for a trip that would take him first to New Zealand, then Australia to promote his products, followed by a flight from Melbourne to Delhi.

The British designer’s name has become a brand now, but it is anything but corporate or bland. He was born in Sfax in Tunisia, where his father was teaching English, and his mother is half French. Dixon, however, is the elusive personification of cosmopolitan London, mixing the gritty and the precious, found objects with handcraft and design classics, combining them all with a gently subversive wit and a natural eye for form, colour and materials.

The stores offer furniture, lighting, and domestic accessories, both to casual shoppers, and to the contract furnishing market. But Dixon likes to bring his stores to life, so food and drink has been a part of the picture since he first opened a pop-up restaurant with talented chef Stevie Parle in a canal-side building at the more interesting end of Ladbroke Grove that became the Dock Kitchen. When he set up there he noticed an abandoned water tower across the street, bought it, and managed to turn it into a unique circular apartment in a typically pragmatic way.

Food was an equally casual addition. “I cooked lunch for my staff, so a restaurant was a natural step.” There is a Dixon restaurant in the Milan store and a bar in his Beijing outlet. The Coal Office in London has a very successful restaurant operated with Assaf Granit. As well as objects and furniture he designs eclectic interiors, ranging from apartments inside a Herzog & de Meuron-designed tower at Canary Wharf, to the interiors of the Mondrian Hotel in London.

Dixon’s career tracks the evolution of contemporary design in Britain since the 1980s, when he was making one-off pieces of creative salvage, to the present day when his furniture is made in factories and he designs superplastic formed aluminium chairs, lighting systems using the latest evolution of LED technology, and all-purpose sofas for IKEA.

The peripatetic migration of his studio, from Notting Hill’s All Saints Road, which he once shared with the French designer and maker André Dubreuil,

to Kings Cross where he took over the Coal Office, a relic of the industrial revolution, is an insight into the shifting social geography of creative London. Most recently the pandemic lockdown saw him going back to hands-on making – as he puts it, for the sheer pleasure of it – in a studio in a part-derelict orchid-growing industrial greenhouse close to Brighton. “McBean’s nursery has been here since 1897, it’s a kind of dystopia in the countryside with only part of it still in operation. I have made a studio there.”

Dixon did manage a six-month stint on the foundation year programme at Chelsea School of Art, as it was then, before a motorcycle accident ended his student career. He played bass guitar for Funkapolitan, a moderately successful post-punk band for a while. He supported himself with music events at weekends and taught himself how to weld metal at the start of the 1980s, a skill which he was able to use to turn himself into a designer. At a time when Britain’s industrial base was shutting down, there was no obvious way for a designer to get their work into production, other than to make it for themselves. It was a moment that produced a kind of informal group of designers in London who were putting salvage to creative use to make furniture. In Ron Arad’s case it was leather upholstered seats taken from Rover cars and combined with scaffolding.

Dixon’s S chair also began by welding scrap; a steering wheel for the base, a recycled rubber inner tube provided the seat and the back. It was a design that reflected a particular moment, but also one which encapsulates Dixon’s career. The fashion retailer Joseph Ettedgui put a display of his work in his shop window. In 1977, when Giulio Cappellini took over the creative leadership of the family firm, sensing that design was moving beyond the traditional group of Milanese masters, he began to look for designers from outside Italy. In 1982 Tom Dixon was one of the first designers he took on. Cappellini started manufacturing an industrial version of the S chair that Dixon had once made with his own hands and 30 years later it is still in production.

In the early days of his career, Dixon always cited Terence Conran – who had also started his career by using his welding skills to make and sell furniture –as an inspiration. In fact, Dixon would spend 10 years as design director and subsequently creative director for Habitat, the home furniture retail business that Conran had started in the 1960s. In those days, when Dixon tended to wear the kind of overalls that you would associate with garage mechanics, Conran in his blue shirts and suits seemed like an unlikely role model. But in the way that Dixon has grown since starting his own brand and developed the reach of design, mixing making and convivial interiors, he was closer than we knew.

046

049

050

ECAL HEAD OF TYPE DESIGN

Matthieu Cortat-Roller

ECAL HEAD OF PRODUCT DESIGN

Camille Blin

ECAL HEAD OF PHOTOGRAPHY

Milo Keller

ECAL HEAD OF MASTER THEORY

Anniina Koivu

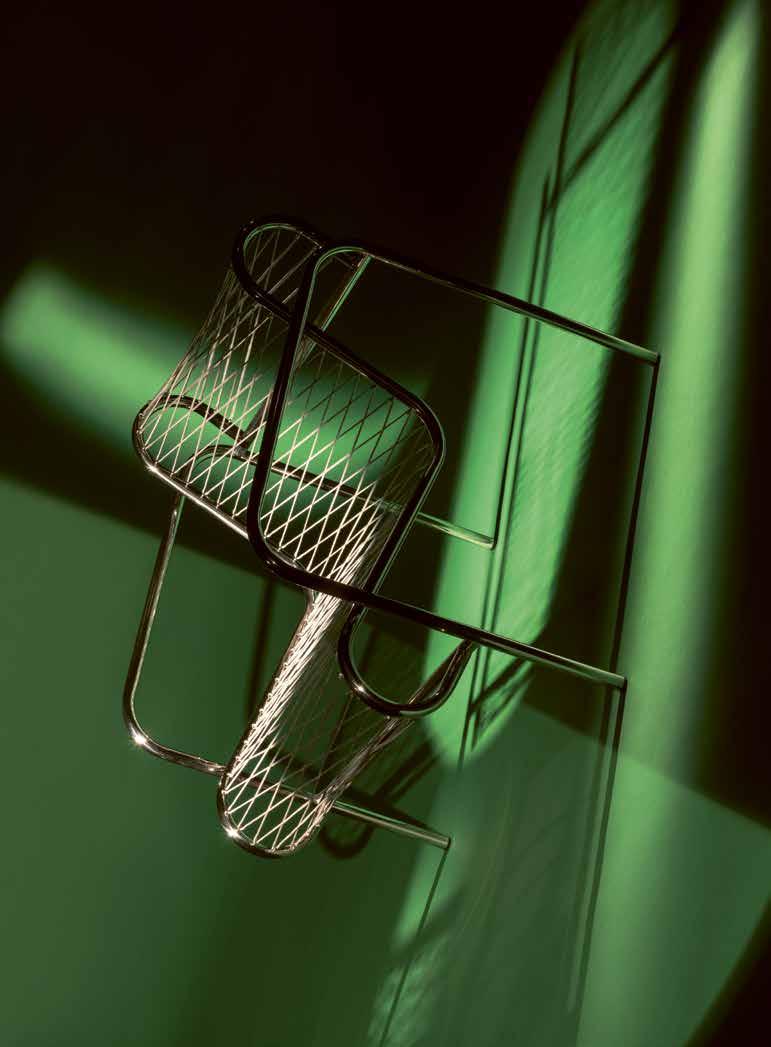

Lausanne’s ECAL school of design has a worldwide reputation for producing talented graduates.

Anima challenged some of its ECAL’s photography students to capture a selection of work from their colleagues

Learning from Lausanne

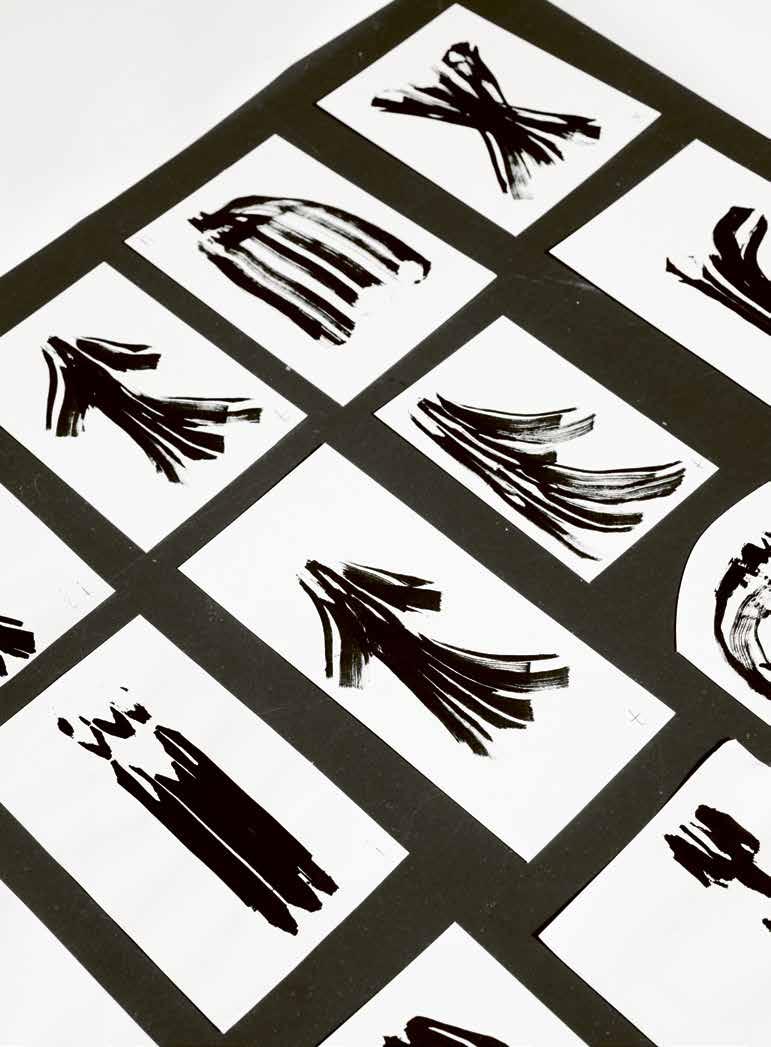

Work created by the Accordion, DIY calligraphy tool, designed by Þorgeir Blöndal, Maximilian Inzinger and AnnaSophia Pohlmann

(Right)

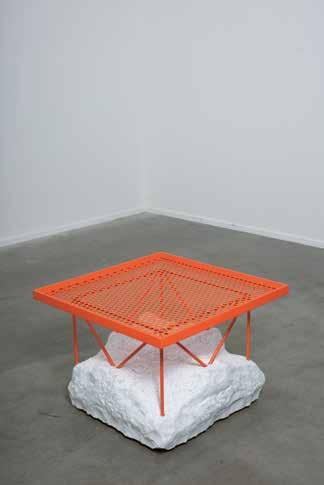

Rako hack storage system

The Georg Utz group is a manufacturer of storage containers including the Rako range. Hilfenhaus transformed a generic industrial plastic product into a domestic system.

Design Justus Hilfenhaus

Photography Isabella Madrid

053 ECAL 2023

Caddie basket

Caddie is a French-owned company that has been manufacturing supermarket trollies since 1957 using wire-working techniques. Caddie has a robotised production line. Weber used ECAL’s workshops to weld her own version.

054

Design Loïs Weber

Photography Carla Rossi

Accordion DIY calligraphy tool

Calligraphy is part of the course for type design master’s students and they were recently asked to design a tool to work with. Product design students, meanwhile, were asked to come up with a design based on an existing brand, and to use its manufacturing techniques and product history to come up with a new design that would fit into its catalogue.

ECAL 2023

Design Þorgeir Blöndal, Maximillian Inzinger and Anna-Sophia Pohlmann

Photography Gina Bolle

ECAL 2023

Recyclable shoes for children

Rieckhoff worked on a range of children’s shoes that can be manufactured without the use of glue, allowing the components to be reused. She explored the idea of a rental system that would allow parents to trade shoes in as their children grow.

060

Design Yohanna Rieckhoff

Photography Benjamin Freedman

Avatar tool

A project exploring the connection between the digital and physical worlds.

Design Luis Shiro Rodriguez

Photography Florian Hilt

063 ECAL 2023

U.F.O.G.O Site specific wind turbines

Fogo, the Canadian island off the coast of Newfoundland is the subject of a series of social enterprise developments initiated by Zita Cobb, a successful businesswoman who grew up there. She has invested in sustainable projects that aim to maintain life on the island. ECAL’s students worked on the design of wind turbines tailored for the location.

Design Marcus Angerer, Jule Bols, Fleur Federica Chiarito, Matteo Dal Lago, Sebastiano Gallizia, Sophia Götz, Maxine Granzin, Lucas Hosteing, Paula Mühlena, Cedric Oder, Oscar Rainbird-Chill, Yohanna Rieckhoff, Luis Rodriguez, Donghwan Song, Chiara Torterolo, Luca Vernieri

Photography Marvin Merkel

064

ECAL 2023

Tony Dunne and Fiona Raby, who pioneered a speculative approach to design as professors at the Royal College of Art in London before moving to New York, convinced their students that asking questions is as important as trying to answer them. Their approach was to explore the consequences of fictional scenarios. What would the world be like if the tendencies that we are just beginning to see are extruded to their logical consequences. They used the same method when they turned their attention to the nature of design education. “There are no disciplines in the conventional sense, instead students study bundles of subjects: rhetoric, ethics and critical theory combined with impossible architecture scenario making and world building, mixed with ideology and found realities and CGI and simulation techniques taught alongside the history of propaganda, conspiracy theories, hoaxes and advertising.”

They were clearly teasing the Design Academy Eindhoven which established its reputation by abolishing traditional skills-based definitions of design. Rather than teaching industrial design, or furniture design, graphics or interior design, as design schools once did, just as a previous generation had departments of leather, metal, ceramics, glass, and textiles, it offers programmes in contextual design, social design and design curating. In some ways this is a natural response to the accelerating pace of change triggered by the digital explosion. As the emphasis has shifted from material objects to the immaterial, design education has been reconfigured. Yet the more that world dematerialises, the more that we value tactile, physical qualities and skills.

suggest that his job was to make his students unemployable. What he was getting at was independence of mind. He wanted his students to be capable of working on their own. When Arad ran the department of design product, its graduates included Martino Gamper, Max Lamb and Paul Cocksedge. While Lausanne doesn’t put it in the same way as Arad did, many of its graduates have gone on to make their own mark too. BIG-GAME, the product design studio founded in 2004 by Augustin Scott de Martinville, Elric Petit and Grégoire Jeanmonod; Carolien Niebling, memorable as the inventor of the sausage of the future; Adrien Rovero, responsible for numerous exhibition designs and windows for Hermès; the passionate photographer Karla Hiraldo Voleau; and the typographers Maximage and Omnigroup are all ECAL graduates.

With only around 600 students, Lausanne is also the smallest of the three schools, even though it offers a foundation year, as well as bachelor’s, master’s and research programmes. The Swiss education system is well-funded enough for ECAL to be able to charge a fee of just £900 for all students including those from abroad, and for them to work in what other schools would see as tiny groups.

“ There are no disciplines in the conventional sense, students just study bundles of subjects”

Of the three design schools in Europe that most often get mentioned as places to watch, The Ecole Cantonale d’art de Lausanne is the most straight-forward and unassuming in the way that it teaches. In Eindhoven, where things have moved on at a pace since Dunne and Raby’s speculations, students now choose between enigmatically named courses in Studio Body Building, Studio Turn Around, The Invisible Studio and The Morning Studio, but in Lausanne, they still have a photography department, a type design department, and a product design department. Perhaps as a result, it is also regarded as the place that turns out the most employable graduates. In some places ‘employability’ is a suspect concept. When Ron Arad taught at the Royal College of Art, he used to

With 1,400 students, London’s Royal College of Art, which was once based only on master’s programmes, is not the place it was when Arad taught there, let alone when David Hockney almost failed to get his diploma. Home students are now charged £8000 a year, or £9,750 if they want a studio space and access to what the RCA calls ‘more than a low level of technical provision’. For overseas students it’s £29,000. As the RCA website warns; “The College reserves the right to charge students the higher fee band if a student is found to be occupying space and using resources in line with the ‘high residency’ provision.” Aware of the steep cost for its students, the RCA is cutting back its master’s programmes, from two years to just one.

066

Cinema Studio, photography Younès Klouche/ECAL

(Right)

068

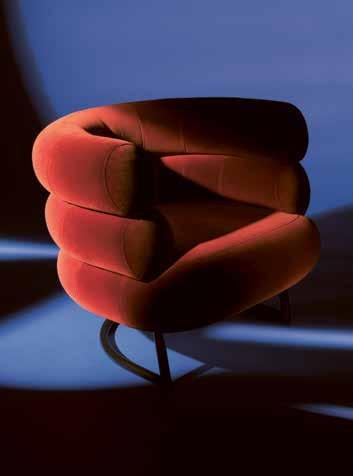

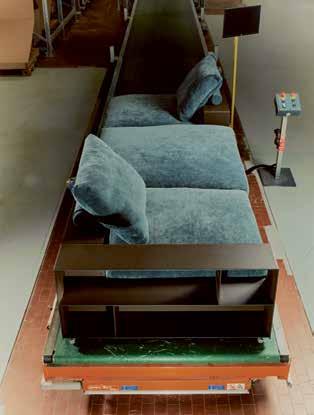

Molteni moves

Vincent Van Duysen, Molteni’s creative director, has reshaped the company’s Giussano HQ to make a platform for the launch of its new outdoor furniture collection

PHOTOGRAPHY

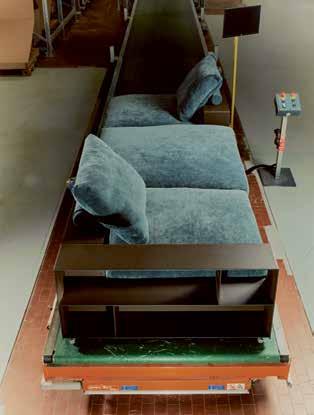

Molteni has been making furniture in Giussano, a small town just outside Milan, since 1934. In that time, it has grown from a workshop into a factory and then transformed itself into a group of companies with a presence in both the domestic furniture field and the office market. Molteni itself is associated with domestic furniture. It has Unifor as its subsidiary specialising in the world of work, while Dada is its kitchen brand.

The evolving history of a family-run business is clearly visible in the architectural traces left on its complex of buildings in an unassuming suburb of Giussano. They are the outcome of a continuing programme of work and investment in production by a series of distinguished architects and designers. Over the years the Molteni family has worked with Afra and Tobia Scarpa, Luca Meda and Aldo Rossi. Angelo Mangiarotti designed the Unifor factory. The Scarpas also designed the family home. Molteni commissioned Norman Foster and Jean Nouvel to design furniture. Rossi worked not only on the firm’s products but was also responsible for the design of the family tomb in Giussano’s monumental cemetery. More recently it has started manufacturing designs by Gio Ponti from the 1950s and 1960s.

For a design conscious furniture company, the architecture of its buildings is both a reflection of its identity, and an important step in creating a setting in which to make the most of its products. What is notable about the Molteni complex is the way the company has worked to retain the memory of each stage of its past, while continuing to add to its heritage by working with new generations of designers to reinvent its traditions. Part of the

Guissano complex designed by Meda, with elements by his friend and collaborator Rossi, was originally built as a timber store that was used to air dry wood before it was used on the production line. Rossi turned it into a showroom for Molteni products, one floor of which was later used as a corporate museum. Vincent Van Duysen, who has been Molteni’s creative director since 2016, taking the role once played by Meda, remodelled it some years ago. Van Duysen, who trained as an architect in his native Belgium, and is now based in Antwerp, has developed a distinctive approach that combines simplicity and rigour with tactile warmth.

Van Duysen has inserted a sophisticated sequence of new indoor and outdoor spaces that form a new route into the Molteni complex, contrasting open-air courtyards landscaped by Marco Bay with a glass-walled pavilion and other interior spaces. The consistency of paired square columns running throughout Van Duysen’s insertion forms a coherent connection between the variety of architectural languages on the site.

The pavilion itself – which is designed to offer visitors a chance to sample Molteni’s hospitality, as well as to see the qualities of its products — is fitted out as an oak-lined restaurant looking over the garden courtyard beyond. It’s an arrangement that consciously sets out to highlight the company’s new-found focus on outdoor furniture, which in itself is a response to the lessons that so many furniture manufacturers learned from the experience of the pandemic lockdown, and its impact on the home.

Max Zambelli

outside

070

What are design museums for?

Understanding that design goes beyond utility and appearance, four directors from world-leading institutions explore its vital role in contemporary life

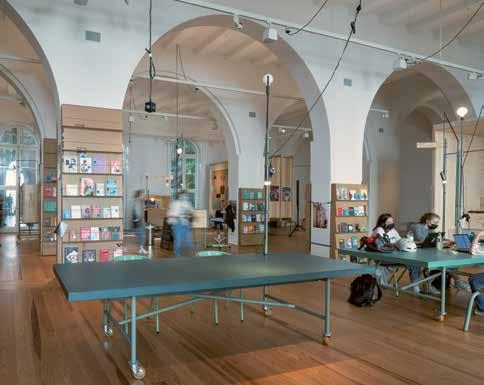

MUDAC Lausanne

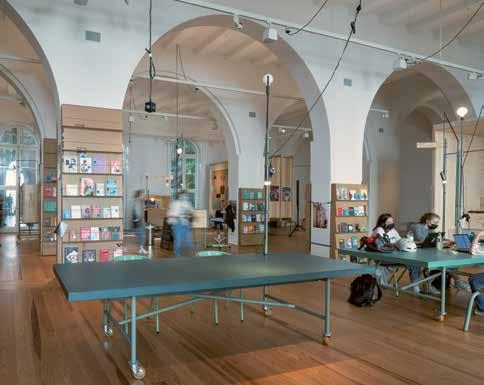

The Museum of Contemporary Design and Applied Arts (MUDAC) first opened in 1967, moving to a second home in 2000. From 2020 it has been based in Plateforme 10, a 25,000m2 arts district that it shares with a fine arts museum and a photography collection.

ARCHITECTS: Francisco and Manuel Aires Mateus 2023 exhibition programme highlight:

As a counterpoint to the idea of universal, canonised knowledge and analytical reason which governed the rational divide of nature and culture, the ancient Greeks deployed the concept of mētis. It denoted a form of embodied intelligence crafted by contextual responsiveness, a type of intuition cultivated with experience, resourcefulness and technical mastery not devoid of proto-magical trickery and the cunning ability to devise solutional strategies with both method and creativity. Aristotle would have possibly singled out design as a mētis-laden practice on par with navigation and medicine.

Design is a shapeshifting set of modes through which we apprehend, imagine and build our rapport with a world that is everyday a little bigger, deeper, expanded through hybrid realms of existence – the perceptual and relational universe of reality revealing itself populated by myriad entanglements among various forms of intelligence, from the microbial scale of fungi and bacteria, or living organisms like slime and plants, to that of synthetic matter such as artificial

networks. The exploration of such hybrids and relationships fuels and determines our socio-cultural lives, and the wider shape of the world.

I see design as a poetics and science of relations that transforms as we transform with it, and a form of practical wisdom that more than others can engage with the fascinating complexities involved in a future evidently destined to drive the ‘human’ off its centre.

The museum I envision is a world-building enterprise that engages these future-facing ecologies of poli-disciplinary knowledge, fostering creative activism and social debate that encourage a view of the web of life liberated from dominating worldviews to embrace instead the empowering notion of what physicist Karen Barad calls ‘intra-action’, where categories of identity are mutually defined and interpenetrated. In a world still abated by inequalities deeply written in our bodies and territories, the future we could inhabit is one where the most effective technologies are those that leave no trace; cities, as theorist Tony Fry would say, are designed as metabolic events of circular

‘Beirut. The Times of Design’

making and dissolution, with new epistemologies emerging at the crossroads of human dreaming, synthetic culture and algorithmic rituals.

As public fora and collective encounters rapidly dematerialise, museums remain precious fortresses of publicness, to explore the biography of ideas – no longer that of objects, spaces, materials or places as discrete entities, but the genealogies of thought that bring them all into ever new relational paradigms of planetary life.

Their mission as purpose-driven organisations is one exercised in orchestrating conversations among public, private and civic stakeholders designing the protocols and environments in which life is imagined, nurtured and perpetuated.

– Beatrice Leanza, Director, MUDAC

(Above)

(Below)

DO AIs DREAM OF CLIMATE CHAOSSYMBIOTIC AI, Iris QU Xiaoyu. Courtesy Camille Blake

MUDAC, photography Matthieu Gafsou

(Above)

(Below)

DO AIs DREAM OF CLIMATE CHAOSSYMBIOTIC AI, Iris QU Xiaoyu. Courtesy Camille Blake

MUDAC, photography Matthieu Gafsou

071

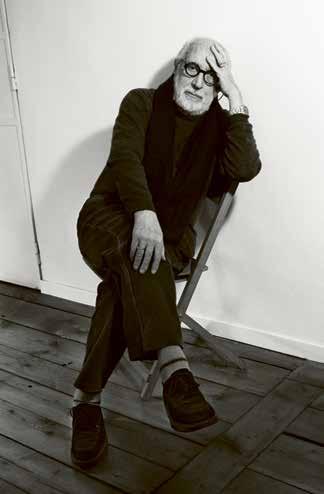

(Above) Beatrice Leanza, photography Diana Tinoco

V&A Dundee

A partnership between the Scottish Government and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London established by Henry Cole after the Great Exhibition of 1851. Opened 2018.

ARCHITECT: Kengo Kuma

2023 exhibition programme highlight: ‘Tartan. A radical new look at one of the world’s best-known fabrics’

Every single person engages with architecture and design every day. They are the most accessible forms of creativity.

We’re too often surrounded by careless design that disregards the planet that hosts us and hinders, rather than helps, people. Design museums advocate for good design for everyone.

In 2018, V&A Dundee opened as Scotland’s dedicated design museum and part of the V&A family of museums. The creation of the museum in Dundee, the UKs only UNESCO City of Design, is part of an ambitious cultural regeneration plan with the design museum at its heart as a creative catalyst. V&A Dundee was conceived as a 21st-century museum, designed for everyone as a place to experience and enjoy design from Scotland and from around the world.

Our mission is to inspire and empower through design and to champion design and designers and the infinite possibilities they bring. Our programme aims to generate joy and spark curiosity for and with audiences, and to inspire confidence in design,

providing thought-provoking content for schools and professionals. The museum’s role is multiple –cultural, social, economic and civic – we are creating jobs, contributing to the economy, and have significant convening power and influence through the stories we tell. The museum is bringing a new audience to design, from city planning to the future of plastics, to showcasing the best in Scottish design.

The museum itself is a marvel of architecture, designed by Kengo Kuma and inspired by Scotland’s cliffs and riverside location, the changing light alters the feel of the spaces each day. It’s created a new harmony between river and surrounding city and has become a new icon for Dundee; later this year we will open a new exhibition exploring the building’s unique design stories.

The design of our building shapes our role as a design museum, we respond to it in a range of ways. The Scottish Design Galleries tell diverse stories of 500 years of design, making and manufacture from Scotland; we stage spectacular exhibitions within

Scotland’s largest exhibition galleries and host talks, tours, workshops and activities for all ages.

We are champions of exhibition making. Engaging audiences in design through a deep exploration and excavation of themes, collections, archives and designers that reflect and refract our humanity, and the ideas and values that help to define the times we live in and through. Exhibitions reveal how our understanding of the past changes with present times. This year we are staging a landmark exhibition on Tartan, a radical look at one of the world’s best-known fabrics – telling its design story from the historic to the contemporary, the rebellious to the established, the sublime to the kitsch.

In our fifth year we are thinking especially hard about what this design museum is for – a place to gather, to mark moments, and to celebrate who we have been and who we can be through design. A place of joy, curiosity and challenge; a place that is useful and loved, attuned to the times we live in, yet able to transcend them.

073

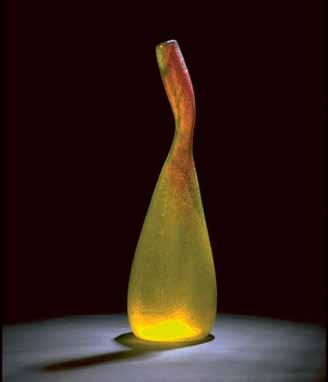

Charles Rennie Mackintosh Oak Room, Scottish Design Galleries, photography Hufton + Crow

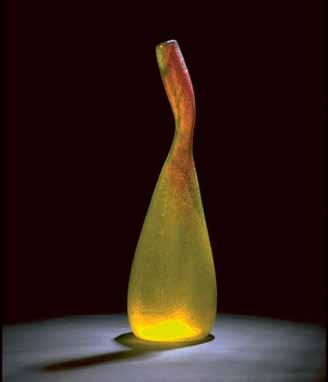

Clutha glass vase, Christopher Dresser and made by James Couper & Sons

(Left) (Below)

Leonie Bell, photography Julie Howden

(Above)

– Leonie Bell, Director, V&A Dundee

Dress, Christopher Kane, 2015 (Above)

MAK Vienna

Inspired by London’s Great Exhibition, the Museum of Applied Arts (MAK) was founded in 1863 and moved into the purpose design building that it still occupies in 1871. The adjoining University of the Applied Arts was initially part of the museum’s activities before it became an independent institution.

ARCHITECT: Heinrich von Ferstel

2023 exhibition programme highlight: ‘/IMAGINE: A Journey into The New Virtual’

My answer to questions about the purpose of a design museum would have been different before I became the director of one of the world’s first examples of the type. Of course, I knew the MAK well. I was a student at the design school that had originally been founded as part of the museum. I knew its collection, its history, and its recent development. It was an exhibition about Bernard Rudofsky at the MAK that made me want to study design in the first place. But living and working so closely with a couple of hundred thousand extraordinary objects has changed my perspective. I have completely fallen in love with our collection and the possibilities that it offers us.

It is inevitably the collection of a museum of the applied arts, founded in 1863, with the Victoria & Albert Museum in London as a model. Its building, in the style of Italian Early Renaissance on the Ringstraße, is an architectural manifesto for the museum’s mission to demonstrate the highest skills in art and making and provide a model for manufacturers and designers. With carpets, porcelain and glass, furniture and

woodworks, metal and jewellery, design, architecture and fashion, but also contemporary art, the collection reaches back to the medieval period but looks to the future.

Rudolf von Eitelberger, the first professor of art history in Vienna, was a truly inventive and modern-minded founding director, and his strategy still offers us a model. By establishing a design school in 1867, theory and practice were brought together. von Eitelberger took advantage of the Vienna World Fair in 1873 to organise the world’s first art studies conference, emphasising the museum’s orientation toward education and research.

The MAK has continued to innovate ever since, building on von Eitelberger’s foundation, but responding to cultural and social change. The permanent collection was redesigned in 1993, with interventions from a number of major contemporary artists including Jenny Holzer and Donald Judd. In 1995 the museum acquired the Wiener Werkstätte archive, a powerful insight into a movement which believed in the idea

that progress is possible through beauty and craft. Our Design Lab – which deals with the themes of the Anthropocene, climate emergency, modern slavery, water and energy shortages, and mobility, through the perspective of a contemporary generation – opened in 2014.

In many of our exhibitions of the past year we have intertwined contemporary and historical objects from many parts of the world to offer an understanding of issues rather than simply looking at timelines. We are an active platform to facilitate communication.

When our understanding of design goes far beyond questions of function or aesthetic value, how we should teach the subject is as much of an issue as the question of how to exhibit it. A design museum must be a place to learn about transformation, diversity, and complexity. It should not limit itself to questions, but ought to think about solutions. In a constantly changing world a design museum need not only be about “what” but can also look at “how”.

– Lilli Hollein, Director, MAK Vienna

Lilli Hollein, photography Stefan Oláh

Franz West sofas, courtesy Wolfgang Wossner/MAK

Lilli Hollein, photography Stefan Oláh

Franz West sofas, courtesy Wolfgang Wossner/MAK

WHAT ARE DESIGN MUSEUMS FOR?

(Left) (Below)

Wißkirchen 21, Helmut Lang Archive, courtesy MAK/Katrin Wißkirchen

Frankfurt Kitchen, Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, photography Gerald Zugmann/MAK

(Above)

(Above)

MK&G Hamburg

The Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe (MK&G) was established in 1873 with a mission to make the German manufacturing industry more competitive, as its name which might be translated as the Museum for Art and Industry suggests. It moved into its present building in 1877.

ARCHITECT: Carl Johann Christian Zimmermann 2023 exhibition programme highlight:

‘The F* word – Guerrilla Girls and Feminist Graphic Design’

The Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the mothership of every applied art museum in the world, was established with a clear economic goal. Its founder, Henry Cole, believed it could teach designers and manufacturers how they could make products more saleable by building a collection of historic and contemporary work that could serve as examples of so called ‘good’ design. Now that design has evolved into a complex and contradictory discipline, a complexity reflected in museums of design themselves, it’s an approach that sounds naively simple-minded. Design is both part of a system of over-consumption and builtin obsolescence, and yet it also offers the possibility of amazing insights into such fields as service design, speculative design, and many more.

I look back to that time now because it offers a future direction for my museum. We can use our collection to explore design not in the moral sense of suggesting that there is such a thing as good design and bad design, but as a means to identify the key questions that face us. Museums of the applied

arts were founded with discovery and exploration at their core. They were searching for a new language for design. At some point they lost that goal and that energy. I want us to go back to those core origins –to find a balance between preserving the old and discovering the new. If our work in the museum is to stay relevant, we have to do more than display our collections. We must find ways to encourage active involvement with them. We have to offer our audience, or as the museum theorist Bernadette Lynch puts it, our ‘critical friends’, the tools to become active partners in the debate on how we want to live.

The connection between design museums and design schools used to be close. It was based on an understanding of the value of learning from the collection. It made possible a platform for debate, based on the creative energy that comes from optimism about the positive possibilities of design, and around the process of making.

I have a vision of where I want to go but I’m also aware that the systems that have developed in our

institution, which is over 140 years old, are under stress. We cannot approach relevance without ensuring that our institutions have new competencies to address themes such as climate change, diversity and inclusion, restitution and repatriation. This is in addition to our core activities. The reality is that we need significant investment and new partnerships to build these new capacities, otherwise, in 50 years, we may not exist. One of the ways we are doing this is by understanding the museum building as a platform for the city and the region. We have started to collaborate with other organisations to give them the benefit of our infrastructure.

We are taking risks in exploring programming beyond exhibitions, by making new voices welcome and sharing spaces. But we need to take risks, because there is a huge period of discovery necessary to bridge the gap between the kind of institutions we are at the present and what we need to be. We make plans, and then prepare for them to change. We need a culture of trial and error.

–

Director,

Director,

MK&G Hamburg, photography Henning Rogge (Left)

Tulga Beyerle (Above)

Tulga Beyerle,

MK&G Hamburg

MK&G Hamburg (Above)

MK&G Hamburg Life on Planet Orsimanirana work room

(Below)

MK&G Hamburg, photography Henning Rogge (Left)

Tulga Beyerle (Above)

Tulga Beyerle,

MK&G Hamburg

MK&G Hamburg (Above)

MK&G Hamburg Life on Planet Orsimanirana work room

(Below)

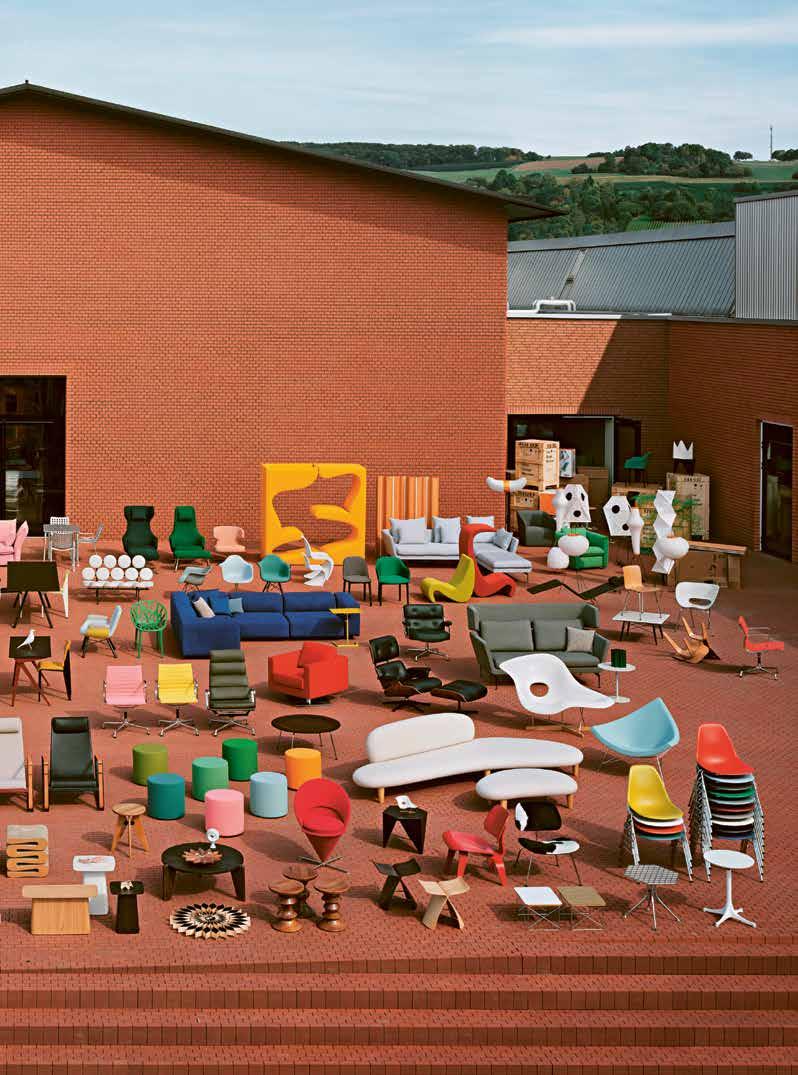

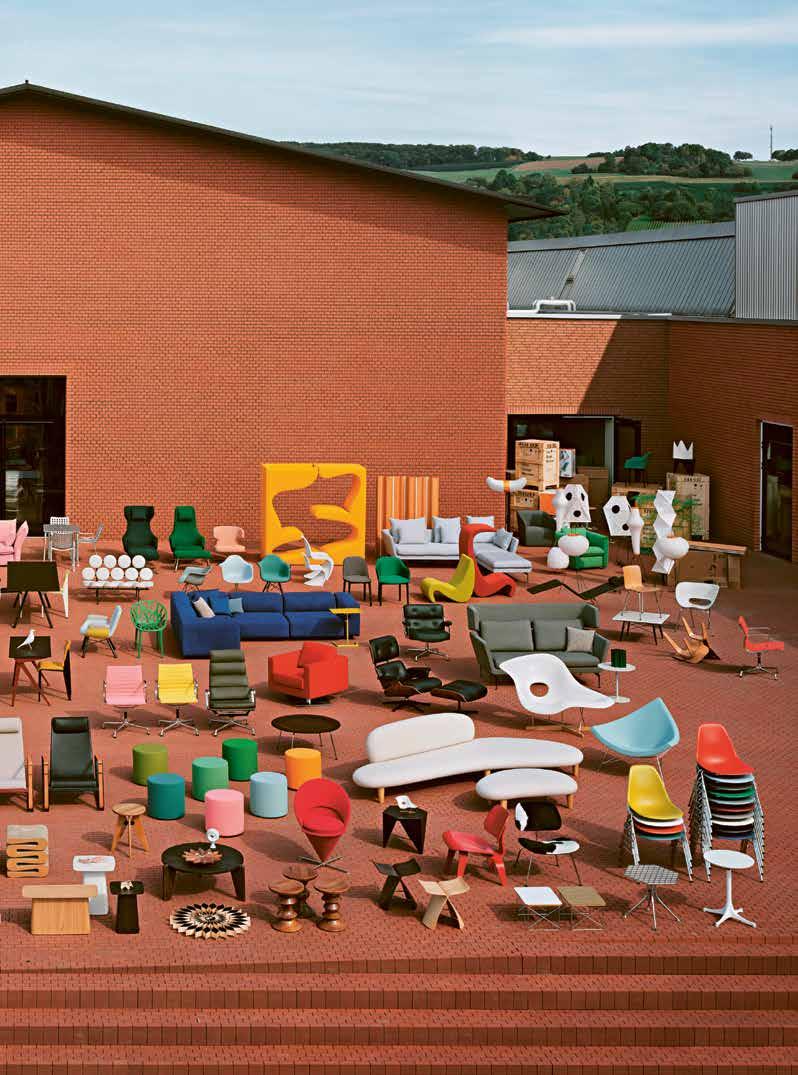

Future ga z i n g

By keeping it in the family, furniture company Vitra has continued to flourish. Anima investigates its remarkable expansion under the helm of Rolf Fehlbaum – who recruited a range of creatives to find a new design language –toits present-day ambitions driven by the next generation, Nora Fehlbaum, to sustainably transform its sprawling campus

078

WORDS Deyan Sudjic

Oudolf Garden on the Vitra Campus, photography Julien Lanoo

with Vitra

079

080

(Above)

(Left)

Herzog & de Meuron's Schaudepot gave the campus space for a permanent display of the Vitra design museum collection. Zaha Hadid’s first building is close by

Vitra Fire Station, Zaha Hadid Architects

The global furniture business today is in a state much like the one that car makers were in during the 1980s: dominated by a small number of very large American companies that have expanded through mergers and takeovers of famous smaller brands, leaving less and less room for specialist producers. As with the car industry, furniture manufacturers are struggling to cope with massive changes in the way that people work and live.

Set beside the dominant brands in the office furniture market, Vitra is modest in scale. The three largest: Herman Miller, which acquired Knoll last year; Haworth, which now owns the Italian brands Cassina, Capellini and Poltrona Frau; and Steelcase, are all based in the Michigan city of Grand Rapids, a Dutch reformed church stronghold and until recently, a dry county forbidden to sell alcohol.

Vitra has maintained its independence since its parent company was established in 1935 by growing gradually and retaining family control. Its decision 10 years ago to take on the then struggling Finnish company Artek, famous for its Alvar Aalto designs, was a rare exception. It is in the way that they view the future that family-owned businesses such as Vitra can most clearly demonstrate what makes them different from their corporate competitors. Like farmers, family businesses are able to take a perspective based on more than short-term financial calculation. When they have another generation to consider, they can be clearer about when to leave a field fallow, when to buy a new tractor, and when to start planting experimental new crops. It is more than an emotional response, it is also the basis for their survival in the long term. The 18th-century economist Adam Smith called it ‘enlightened self-interest’. Such companies invest in the future so that they can continue to innovate and continue to flourish.

In the case of Vitra, a company founded by Erika and Willi Fehlbaum in Switzerland, but which moved its factory to the small German town of Weil am Rhein (close enough to the border to feel like part of the Basel conurbation), it’s a perspective that has enabled a remarkable transition. Over 70 years Vitra has gone from a shop-fitting specialist to a creative powerhouse for every aspect of the culture of design.

Starting in the 1950s, Erika added bit by bit to the company’s land holdings around the utilitarian factory and an adjoining office block that they had built. Willi too realised that he needed to broaden Vitra’s product range to address the seasonal nature of shopfitting and keep the factory busy year-round. He tried manufacturing a chair in Plexiglass. He spotted the potential of Charles and Ray Eames’s newly launched cast aluminium work chairs manufactured by Herman Miller. Britain and Scandinavia were already spoken for, but he secured the licence for Vitra to make and sell them in most of Europe. It took time. Herman Miller’s founder, the teetotal fundamentalist preacher DJ De Pree, ignored his first letter. He only responded when

Fehlbaum dispatched a cheque for $20,000 to demonstrate his seriousness. Willi Fehlbaum set off for Grand Rapids to negotiate an agreement, taking his 16-year-old eldest son Rolf with him to translate.