17 minute read

in this issue

Truth and Catholic Education

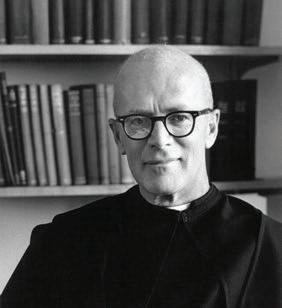

by Dom Aelred Graham, 1977

Reprinted from the Portsmouth Abbey School Fiftieth Anniversary Publication

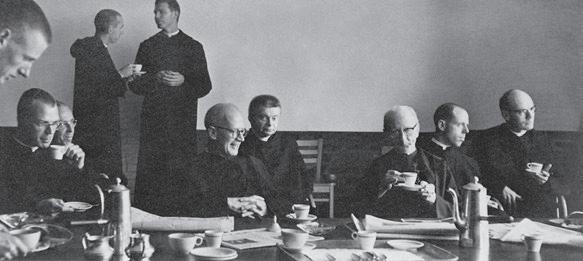

Members of the monastic community in 1960: from left to right, Dom Anselm Hufstader, Dom Philip Wilson, Dom Peter Sidler, Dom Gregory McClure, Dom Ambrose Wolverton, Very Rev. Dom Aelred Graham, Brother Basil Cunningham, Dom Wilfrid Bayne, Dom Christopher Davis ’45, and Dom David Hurst.

Rather than yield at the outset to my besetting weakness for generalities and abstractions, it may be well to give some account of how I came to know and increasingly to love the Portsmouth community. On August 8, 1951 I landed from the Nieuw Amsterdam at Hoboken, to be met and warmly welcomed by Father Peter. The car assigned to be driven down to New York from the Priory (as it then was) had burned out its motor in transit. A satisfactory substitute was somehow found, but the initial mishap lingered for a little in my mind. Was it a portent of something to come --one did not quite know what? Misgivings were soon dispelled and within a few days I found myself settling into what were at that time decidedly primitive monastic quarters on Narragansett Bay.

Looking back on those sixteen years (1951-1967) when I was not only resident in the United States (for the first time), but also virtually a member of an American Benedictine community, they appear to me now filled with pleasant memories. First in importance comes the slow influx into the monastery of dedicated young men, several of whom now hold posts of key responsibility. They had been called to serve God through a life of prayer and liturgical worship, also to play their part in handing on to others the religious and cultural values they themselves had received. While getting to know the community one was also learning to know its friends, to become aware how strongly Portsmouth was supported by its alumni and by parents of present and past students in the school.

Things seemed to happen around one, through the insight and energies of the community, rather than by any marked direction from the top. The choice of a distinguished architect, for example, to design our new buildings, Pietro Belluschi, emerged by an inspired consensus. The fighting off of a menace from an oil refinery was chiefly due to the skill of our redoubtable attorney, the late Cornelius (Connie) C. Moore. Awareness of our needs and a generous readiness to help led to the raising of sufficient funds for our development program. Meanwhile the routine work of the school

was carried on by a highly competent lay and monastic faculty; day-to-day general administration stemmed almost wholly from the offices of the headmaster and bursar.

Of course from time to time a Priorial initiative was called for. I knew a little of how to conceptualize and verbalize some principles of the spiritual life, and these talks were listened to patiently at our weekly monastic conferences, often rather more than patiently. In retrospect I think it was the community’s general appreciation of one’s efforts, their cooperation even encouragement in our various projects, the forbearance with one’s mistakes, which made the period of my priorship for me such a rewarding one. Occasional meetings with the boys, individually or in groups, and talking to them collectively in church each Monday evening remain among cherished memories.

But now what of the present and the future? A kindly providence has arranged that I should still be able to keep somewhat in touch with Portsmouth’s affairs. Each summer hospitable friends invite me for a lengthy visit to Cape Cod, where I find myself little more than an hour’s car ride from the Abbey. Despite my half-hearted protests that an old actor should not be seen hanging around the green room, I am warmly welcomed there annually by my former associates and, being now without any executive responsibilities, find the encounters increasingly congenial. Though Portsmouth has its problems, they are not different from or more complex than those besetting other monastic schools, particularly those of the English Benedictine Congregation. And here I have no inclination to advise, still less to prophesy. Concrete decisions are obviously to be made by the people on the spot, future planning left in the hands of those in close touch with the present situation. The best I can offer are a few reflections of a general kind, leaving it to others to decide how far, if at all, they are applicable in the case of Portsmouth.

Apart from the difficulties involved in providing what is necessarily an expensive education in the present state of the economy, we have to deal with the problem of operating a Catholic school when religion, itself, or at any rate institutional religion, is largely at a discount. But here we are faced with a challenge rather than grounds for dismay. I take it as axiomatic that in our passage through life our one supreme task is to try to bring ourselves, and those influenced by us, nearer to the truth of things. That was how, when confronting Pilate, Jesus proclaimed his mission: What I was born for, what I came into the world for, is to bear witness of the truth” (John 18:37). These words, I have long believed, provide the basic inspiration for a Christian and Catholic education. The more so if we understand them at the deepest level: truth is not for or against anything, truth simply is. What follows?

Let us accept as a principle the familiar adage that religion is not as much taught as caught. One result of the controversies ensuing from Vatican II has been to weaken almost to the point of extinction long accepted methods of religious instruction. Indoctrination is out. The appeal must still be to the intelligence, but reason must be stirred through sensibility and imagination, perhaps by some process of meditative experience. Not therefore – “This is how it is,” but “Let us look at this together.” Here it is noteworthy that Catholicism can respond to this test with greater effectiveness than presentations of religion which often appear little more than a judicious mixture of scientific positivism and biblical fundamentalism. Evidence suggests that the Church, or rather its representatives, may have become neglectful of its own treasure. If young people are bored by a good deal they read in Scripture, by accounts of the Church’s history, by ecumenism and the trendy religious controversies surrounding such topics as abortion, contraception and divorce, the explanation is simple: they don’t see the relevance of these matters to the lives they have to live here and now.

Yet move to another series of questions: Why is it more important for me to know what wisdom is than just to have at one’s fingertips a lot of facts? What is wisdom anyway? And what justice? Why is it wrong to be unfair to other people, or to be dishonest or to tell lies? What is the difference between foolhardiness and real bravery? Why is it said that the highest form of courage is simply to be patient? And take sex: is there anything really wrong about it? What is the difference between being a puritan and a libertine?

The Zen Garden at Portsmouth, designed by Dom Aelred Graham, 1962.

Then alcohol and other drugs: are the people who urge restraint in these matters spoilsports and killjoys? Or do they have solid reasons for what they say? These questions, which touch vital issues for nearly everybody, young and old, are not picked out of the air. They merely state interrogatively an ethical tradition, which has come down to us from ancient Greece, accepted by the Church fathers and expanded in magisterial fashion, within a mediaeval context by St. Thomas Aquinas. They embody the four cardinal virtues of prudence, justice, fortitude and moderation, upheld as norms of civilized conduct alike in Plato’s Republic and the Old Testament Wisdom of Solomon.

The emphasis on a life based on natural virtue, the substructure for divine grace, is still very much a part of Catholic tradition, though it could have been somewhat lost sight of amid the liturgical and ecumenical clouds emanating from current ecclesiological discussions. At any rate, personal religious and ecumenical concerns have shifted from strongly held doctrinal positions to the area of conduct, and more fundamentally, the attitude of mind and heart which inspires it. Here Catholicism and particularly the ethos of a Benedictine school are at no disadvantage; they may well be unique and irreplaceable. So the questions from our teenagers in class may rise to another level: What is love? How can I become an understanding and loving person? How can I be unselfish when I’m forced into competition with a lot of other people? Is love for God the same as or different from the love for others? How can Christ, who lived 2000 years ago, be meaningful in my life today?

These questions can all be fruitfully discussed, as they have long occupied the minds of religious thinkers, but they cannot be satisfactorily answered in words. They lead directly to the function of Catholic religious practice – liturgical, sacramental worship, crowned by the Mass, which de-

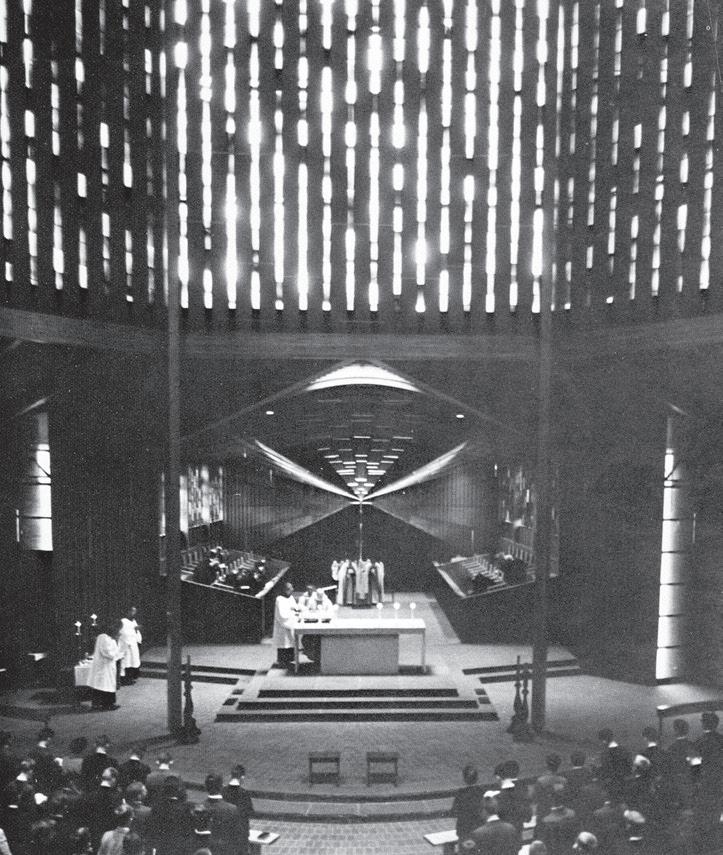

The School at Mass, 1962.

mands in turn to be brought in the minds of the partici- life, who “came not to be served but to serve” (Mark 10:45). pants to the highest degree of conscious awareness. So it is The point is familiar enough and yet there are aspects of that the communion – which means being at one with each it which may be overlooked. Selfless service means literother – as a ceremonial symbol is actualized in every-day ally that we serve without regard to the self. No looking for life. In this way the often turbulent, competitive routine of any feed-back, therefore, in terms of recognition or praise. schoolboy existence can be chas- This may or may not come – as a bytened by the sense of a living com- “A well-furnished, disciplined mind, product, perhaps, of enlightened selfmunity. After all, we are, each one able to transmit to others a knowlinterest – but is quite incidental to the of us, our brother’s keeper. This, service itself, which should be wholly as I understand it, is the abiding edge of the best that has been thought for the benefit of those we serve. And sanction for a monastic school: not and said and done by those who have then the quality of the service – a matas a recruiting ground for monks, gone before us – this surely is what is ter worth pausing over in the context even though now and then a boy owed to the young people under our of a college preparatory school. “Acamay choose to take that path, but care at Portsmouth Abbey School.” demic excellence” is a stock phrase, as providing at least one model of but it represents one of the goals in how Christianity may be authenti- the form of service to which a comcally lived. munity like Portsmouth is pledged. A well-furnished, disciplined mind, able to transmit to others a knowledge of At a time when the external life of Christ is in some dis- the best that has been thought and said and done by those order the need is forced upon us to develop our personal who have gone before us – this surely is what is owed to the relationship with God. Let us examine briefly three areas in young people under our care at Portsmouth Abbey School. which this can satisfactorily be done. Within which of these our own inclination lies will chiefly be decided by tempera- The third area is that of what is commonly called religious ment and opportunity. First and most obvious is the area of experience. Here we are not just concerned with worship individual and communal worship. The challenge here is to as a duty, performed in the darkness of faith, or with servtransform what may have become an almost mechanical lip ing others because that is what God requires of us. At this service, if it has not been neglected altogether, into a genu- stage worship and service are enlivened by some kind of felt ine self-dedication to God in spirit and truth. Not only the awareness of that which is worshipped and served. “O taste Mass and the sacraments, prayer, meditation and spiritual and see that the Lord is good! Happy is the man who takes reading, but working and playing, feasting and conviviality, refuge in him!” (Psalm 34:8). It is this element in religion can all be modes of worship. “So, whether you eat or drink, that is so in demand today; for the seeming lack of it the or whatever you do, do all to the glory of God.” (1 Corin- routine ministration of the Church are being widely disrethians 10:31) – not as preoccupied with self, therefore, not garded. Which brings us back inevitably to Christianity’s merely for pleasure’s sake. The word eucharist, it is helpful to central figure, Jesus himself. What are we to say of him, remind ourselves, means thanksgiving. Thus the mark of the pious rhetoric apart, to teenagers in our secular society? truly religious person is an unceasing sense of gratitude; he or she never takes anything for granted. They appear We note, a little regretfully, that there is no record of what grateful for everything, even for what they may rightfully he said and did when he himself was a teenager, no account claim is due. of his state of mind when he was at an age comparable to that of a Portsmouth schoolboy. All we know is that the subThe second area in which our relationship to God can be stance of his later teaching, which flowed from his personal developed and deepened is that of the selfless service to insight and experience, was the paramount importance of others. We know this to be the highest expression of Christ- loving God above everything else and our neighbor as our-

selves. For him this was the sum total of religion – or in his own Judaic phraseology: “On these two commandments depend all the law and the prophets” (Matthew 22:40) What is surely demanded of us today is to focus our attention on these evangelical simplicities. We are concerned, not with adoring a Christ who lived 2000 years ago, but with having as a present reality “this mind among yourselves, which you have in Christ Jesus” (Philippians 2:5). Love of God and our neighbor cannot be produced by an act of the human will; it is a response to the perceived realities of our situation. What can result is the kind of awareness that takes it consciously as accepted that “in him we live and move and have our being” (Acts 17:28), and empathy so deep that neighbor cannot basically be distinguished from oneself.

Too hopelessly idealistic, we may say, too out of this world. Perhaps, but we cannot escape the challenge to move forward in thought and practice from religion about Jesus to the religion of Jesus himself. Being a Christian means more than worshipping Christ and trying to do His will, though it means both these things. What emerges from the gospels, especially St. John, is the invitation to stand in the same relation to the Father as Christ himself did – “that they may all be one; even as though, Father, art in me, and I in thee, that they also may be in us…that they may be one even as we are one” (John 17:21, 22). Paradoxical as it may sound, we are not here involved in a flight from the world but with living more realistically in it. A sharp distinction between nature and supernature has bedeviled Catholic theology for centuries. To love God as we should calls for enlightening grace, but it is not “supernatural”; it is according to nature, as St. Thomas Aquinas insisted. Similarly to love our neighbors as another self requires only the removal of the illusion by which we regard him as separate, not the pretense of seeing him as other than he is. Occasionally we come across the person who strikes us as genuinely holy; he or she seemingly has no hang-ups, no affectations, no social “persona”; there is no preparing “a face to meet the faces that you meet.” Unconcerned about their “image,” they are free from postures and attitudes, while their habitual consideration and compassion for others blend with spontaneity. How natural he (or she) is! – we hear people say, by way of the highest compliment.

But let me conclude these wandering thoughts nearer to home. From friendly but close observation I have learned that today, by God’s grace, Portsmouth Abbey and its school are in well-qualified hands. The present administration, both in spiritual and temporal affairs, is fully equipped to decide what future developments should be. If some of the foregoing remarks appear a little too dogmatic, I believe that they raise no issues that the resident community has not been reviewing on its own. For all their necessary concern with seemingly worldly affairs, the monks, ably partnered by the lay faculty, are dedicated to the pursuit of something beyond conventional excellence – though there is much evidence of their success in this. Portsmouth represents faithfully St. Benedict’s “school of the Lord’s service,” where those in religious vows, and even schoolboys no less, at least initially and if they so desire, may “run with unspeakable sweetness of love in the way of God’s commandments.”

Dom Aelred Graham O.S.B.

d

Stay Connected

To keep up with general news and information about Portsmouth Abbey School, we encourage you to bookmark the www.portsmouthabbey. org website. Check our listing of upcoming alumni events here on campus and around the country. And please remember to share news with our Office of Development & Alumni Affairs.

If you would like to receive our e-newsletter, Musings, please make sure we have your email address (send to: info@portsmouthabbey.org).

To submit class notes and photos (1-5 MB), please email: classnotes@portsmouthabbey.org or mail to Portsmouth Abbey Office of Development and Alumni Affairs, 285 Cory’s Lane, Portsmouth, Rhode Island 02871.

The Alumni Bulletin is published bi-annually for alumni, parents and friends by Portsmouth Abbey School, a Catholic Benedictine preparatory school for young men and women in Forms IIIVI (grades 9-12) in Portsmouth, RI.

If you have opinions or comments on the articles contained in our Bulletin, please email: communications @ portsmouthabbey.org or write to the Office of Communications, Portsmouth Abbey School, 285 Cory’s Lane, Portsmouth, RI 02871

Please include your name and phone number. The editors reserve the right to edit articles for content, length, grammar, magazine style, and suitability to the mission of Portsmouth Abbey School.

Headmaster: Daniel McDonough Assistant Headmaster for Advancement: Matthew Walter

Editor: Kathy Heydt Contributing Editor: Megan Tady Art Director: Kathy Heydt Photography: Marianne Lee, Andrea Hansen, Louis Walker, Katie Blais, Kathy Heydt

Individual photos seen in alumni profiles have been supplied courtesy of the respective alumni.

in this issue

Truth and Catholic Education by Dom Aelred Graham, 1977 3

Reunion 2021 10

Janice Brady, Leaving a Legacy of Inspiration and Dedication 12 by Director of Communications Kathy Heydt

J. Clifford Hobbins, A Legend in His Own Time by Director of Communications Kathy Heydt 18

Alumnus Profiles:

Education in the Face of Adversity by Vincent Scanlan ’79 in an interview with Joseph Scanlan ’44 Dr. Milton Little ’99 by Lori Ferguson 26

32

Timothy McGuirk’11, The Pursuit of a Meaningful Life 36 by Director of Communications Kathy Heydt

Haney Fellow Augusta Ambrose ’21 From the Office of Development & Alumni Affairs: The William A. Crimmins ’48 Scholarship Fund by Assistant Headmaster for Advancement Matt Walter and James P. MacGuire’70 40

42

Abbot’s Reception 2020 by Director of Special Events Carla Kenahan 48

Parents’ Pride: Alumni and their children reflect on their Abbey experience by the Offices of Admission & Parent Relations 50

Portsmouth Institute for Faith and Culture: 2020-2021 Science and Spirituality Lecture Series on Creation and Contemplation by Executive Director Christopher Fisher

Fall 2020 Athletics 52

54

20th Annual Scholarship Golf Tournament

Milestones: Births, Weddings, Necrology

In Memoriam

Reverend Dom Julian Stead O.S.B. ’43 Daniel T. “Bud” Kelly, Jr. ’39 Dr. Orpheus Joseph Bizzozero ’52 George Pendergast ’62 Thomas Shevlin ’64 Philip Coen 57

58

62

67 68 68 69 70

Class Notes 71