13 minute read

Personality

OBSE SSED

highest level of safety equipment offered by the manufacturer. This covers a range of active and passive safety technologies, which all play their own role. In addition to telematics and DSS, Toll’s spec also includes the latest EBS braking and rollover protection systems, active cruise control, lane assist, and side underrun protection. We are also fitting vehicles with cameras to capture what happens on the road to assist with incident analysis.

PM: What recent technology has been game-changing? AR: One of our big wins is DSS technology. Our systems comprise in-cabin cameras that use software to detect fatigue and distraction events in drivers. I’ve witnessed the results firsthand of how it delivers positive safety outcomes on many different levels. We pick up events in real time and work with the drivers to ensure their welfare, and we can also use the findings as a coaching tool later on. One particularly positive recent story involved a driver who had a couple of fatigue events that were picked up by the system. He was tested by a doctor and was diagnosed with sleep apnoea, which he was completely unaware that he had. As a result, he now has a portable CPAP machine that he takes with him, and he says he feels 20 years younger.

PM: What’s coming up on the radar in the safety technology space? AR: There has been a lot of discussion around Autonomous Emergency Braking (AEB), given the recent Regulatory Impact Statement (RIS) which seeks to mandate it for some classes of truck by 2020. Even though it’s a relatively new technology, we’ve had AEB on a number of trucks and our experience has been overwhelmingly positive. We completely support the proposal to mandate AEB on new trucks and we don’t think it should be delayed any further. The question I ask is, given that it was mandated in other countries six years ago, why have Australian regulators waited so long?

PM: Does it seem that it is the industry itself leading the change for improvements in safety? AR: Regrettably, for a lot of the transport industry the take-up isn’t there. I think we’ve seen that clearly with AEB despite it being available on many truck models for some time. I read in the RIS that the take-up sits at around six per cent of the fleet, which is pretty low. Our own fleet would be much higher because of our approach to fleet specifications, but in terms of our role in advocating and encouraging safety technologies there is only so much we can achieve. We’ll push as hard as we can, but until it’s written into the law and mandated it’s unlikely to be widespread.

PM: Are there any metrics to measure the influence of the technologies? AR: We’ve seen an incredible improvement in key safety metrics in recent times as a result of our safety initiatives, which have included rolling-out key safety technologies. Looking at Toll employees alone (i.e. excluding subcontractors), across 2010- 11 there was one fatality per 29 million kilometres, but by 2015-16 that had reduced significantly to one fatality per 116 million kilometres. That’s a massive factor of improvement, so we understand clearly that the changes are having a real impact.

PM: What’s the approach to Electronic Work Diaries? AR: We think this is a really important next step and we’ve supported mandatory telematics and work diaries over the years. Again, many overseas jurisdictions have made them mandatory, so I ask the question, why haven’t we done so in Australia? The technology is available now, we’ve got many examples in our fleets and we are definitely seeing benefits in terms of safety and compliance.

PM: What’s your key message around safety technology for trucks? AR: Be safety obsessed. Do not hesitate in fitting safety technologies to your fleet. Why wait for them to be mandated? Why wait for the regulations to catch up with the industry? If a safety technology is available now, it can, and should be fitted. I wholeheartedly encourage the widespread adoption of road safety technologies. Toll welcomes the opportunity to continue to take on an advocacy and encouragement role and share our experience.

THE BOY FROM THE BUSH

AN OUTBACK TRIP IN A SEMI-TRAILER WITH HIS FATHER, THE LATE COLIN FULWOOD, IN 1968 AT THE AGE OF 14, CEMENTED JEFF FULWOOD’S LIFELONG CAREER AS AN OUTBACK TRUCKIE. FOR HIS TIRELESS DEDICATION TO THE INDUSTRY, IN 2017, JEFF WAS INDUCTED INTO THE ROAD TRANSPORT HALL OF FAME AT ALICE SPRINGS.

We took a load of Gilbarco equipment on a Dodge semi from Adelaide to Gidgealpa, near Moomba in the far north-east corner of South Australia,” Jeff recalls. “The Strzelecki Track was primarily just station roads then and I remember this trip like it was last week. I was occasionally allowed to steer, and vividly recall Dad’s stern warning: ‘Get your thumbs out of there, son. If we hit sand, the steering wheel will spin around and break your thumbs off.’” This knowledge came in very handy for Jeff when years later he restored and then drove a 1943 Chev Blitz truck across the Simpson Desert. “Dad also told me things like, ‘See that tree line over there, it means a creek crossing is coming up.’” Jeff began driving trucks at age 17 for the family business carting general freight, including many loads of 67kg bagged flour which had to be lumped into bakeries. In 1974, after the huge outback floods, he did a few trips back up the Strzelecki Track to Moomba from Adelaide. This was for Alan Crawford (AKA Tonto), a truckie for whom Jeff says he has the greatest admiration. “I was driving a single drive Leyland Buffalo, but to continue this work Alan wanted us to have a bogie drive truck which Dad wouldn’t buy.” During 1977 Jeff ventured out and bought a new Ford Louisville prime mover sporting a Cummins VT903 engine, 15-speed Roadranger box and 38,000 lb Rockwell diffs on Hendrickson suspension. However, after two trips to Perth doing the promised work, he knew this run wasn’t for him. “For the next three years I did Adelaide to Darwin roadtrain general freight for Freight Brokers, TNT and others,” he says, “and some interstate and local

work in between to give the truck a break from the rough South Road which, being mostly dirt from Port Augusta to the Northern Territory border, gave cause for lots of roadside repairs.” Jeff will never forget a trip with John Doyle when he infamously tipped the trailer-sized computer off and then reloaded it with surprise help, as if by divine intervention, when a massive yellow loader turned up. In 1980 TNT offered him work from Adelaide to Moomba for a Santos expansion project. He was soon working on the ‘Strez’ again. By 1981 he purchased a new W-model Kenworth roadtrain from good friend Peter ‘the Greek’ Kolizos. It was assigned, in the main part, general freight from Adelaide to Moomba for Santos. “During my first trip I met an industry icon, Neil Mansell, who wished me luck with the new job and said to see his boys if I wanted to do any rig shifts in

between Adelaide runs. Well, I passed the initiation of my first rig shift, but sadly my lead trailer didn’t. The massive load broke one main chassis rail,” Jeff recalls. “Working for Neil felt like an honour. I admire his built-for-purpose equipment and his empathy towards mates and employees, past and present.” In 1986, as the work dropped off, Jeff began the overnight Northern Territory Freight Services (NTFS) run from Adelaide to Alice Springs every Wednesday night and back then there were still some dirt sections of the Stuart Highway. On the way back he hauled timber sleepers from the newly dismantled old Ghan railway line that had run beside the Oodnadatta Track. Later that same year in the Alice, Jeff hooked up with two trailers of drummed cyanide pellets after the NTFS run. These were to be taken to Tennant Creek. “Near Barrow Creek I collided with an abandoned 1200cc road bike after the drunken rider had hit a cow. My roadtrain rolled as a result, spreading deadly cyanide pellets everywhere. Huge drama followed with the clean up and recovery operations,” he says. “I never recovered financially from this incident and everything was sold in the late 1980s. I then drove for others until 1997, doing as much bush work as I could.” In 1997 Jeff purchased what he calls a ‘magnificent machine’ – a 1993 C500 Kenworth prime mover. “This became my best-ever truck and the one I did most of my operating in for more than 18 years. The work that came with it introduced me to delivering fuel and carting crude oil all over the interior of Australia for a variety of companies up until 2014,” he recalls. The operation involved servicing most stations and road camps up the Strzelecki, Oodnadatta and Birdsville tracks and many in between taking Jeff throughout the Cooper Basin and his favourite part of Australia – the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) aboriginal lands. As a result, he spent a few years going west past Uluru every

Jeff Fulwood.

fortnight, delivering fuel to aboriginal communities all the way along the Great Central Road through to Kalgoorlie. He then reloaded and headed back again, finishing back at his base in Port Augusta. On a muddy floodway, west of Tjukayirla Roadhouse, Jeff got a triple roadtrain bogged. It was on a precarious lean. Trying to prevent a dangerous rollover, he managed to unhitch it and get the prime mover and lead tanker through to the roadhouse to unload. The only way to get the bogged tanker free, according to Jeff, was to pump the fuel out – JetA1 for the Warburton Airport on which the Royal Flying Doctor Service was reliant – and into the empty tanker. “Being either brave or stupid, I hung an airline around my neck and the other end up in a tree as I crammed in under the listing tanker to hook the hoses onto the just visible outlets,” he recalls. “Kneeling down with mud and water up to my waist, I thought if it rolled then maybe I could still get air through the airline. A bloke from Port Hedland pulled up, reckoned I was crazy, took a picture and headed off. I eventually emptied the tanker and the next day a grader rocked up and we managed to get it all out and moving again.” Many other opportunities arose for Jeff through the ensuing years as the business grew to 14 roadtrains, mainly Kenworths, of course, and nearly all working in later years for Toll Energy. With depots in Moomba, Quorn and Port Augusta, the business subsisted on excellent structure and good management from Garry Roeby and Jeff’s brother Ian. He even restored an old W-model, which is now on display at the Road Transport Hall of Fame in Alice Springs. He loves the APY lands with its red sand dunes, desert oaks and ghost gums. “The mountain ranges and rock formations are sights to behold,” Jeff says. “I admire and respect all those who live there.” In recent years Jeff has worked for the Darwin-based Nighthawk Transport. His main job is a weekly triple roadtrain run of general freight to Nhulunbuy, on the Central Arnhem Road. With 600 kilometres each way of relentless rough corrugated road, wash outs, bulldust, jump ups and the like, Jeff describes this as one of the most challenging tasks he has done, especially when in wet season. Although he has mixed feelings about the heavily regulated industry, Jeff believes many of the changes he has seen are for the better. For the first nine years he didn’t have a sleeper cab, having to sleep across the seats or use a swag. There was no air conditioner for those first 33 years. The introduction of tubeless tyres he deems a major milestone. “Didn’t we have fun trying to seal them up after mending punctures on the South Road,” he says, and on load restraint, “Everything was restrained by ropes and chains until straps appeared. My new Kenworth has central tyre inflation so I can let the truck’s tyres down and pump them up again on the move for dirt road running.” Today he maintains a passion for road transport, especially outback operators. Jeff admires the many truckies that came before him who he says did it much tougher. “I say to drivers wanting to do bush work you need two qualities: patience and perseverance,” he says. “I don’t know if they can be taught or are just in the blood, but thanks a million Dad for planting those seeds a few billion corrugations ago.”

PETER HART

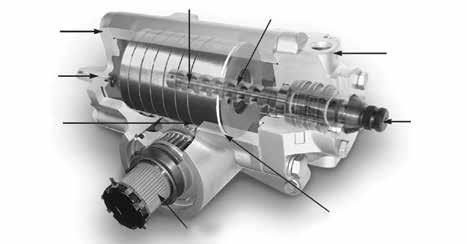

Iam currently investigating a power steering problem on a heavy-duty prime-mover. This provides me with an opportunity to learn what can go wrong and to describe to you the basics of power steering. Most heavy trucks have a single power steering box on the right-side. Dual-axle trucks will have an additional slave steering box to increase the steering force. The photo shows the steering shaft from the cabin connected to the steering box. In this installation the shaft goes via two universal joints and a bearing . The steering box converts the rotary motion of the steering column into fore and aft movement of the Pitman arm. In turn, this arm moves the steering mechanism (for further information see my February 2019 article Steering Basics). The steering box is a gearbox with hydraulic oil pressure assistance when the steering column is turned away from the straight-ahead position. A cross-section is shown in the diagram. The actuating shaft has a ball thread that contains ball bearings. This is done to minimise the turning torque. If hydraulic assistance is lost, the driver will need to steer the wheels with manual force and so the less drag involved in the steering box the better. The piston rack is moved by both the rotation of the actuating shaft via the threads and by hydraulic force on the piston.

Power steering

The hydraulic force comes from a net hydraulic pressure on the piston that occurs because turning the actuating shaft opens one or the other hydraulic flow valves, which causes steering fluid to flow into one or the other end of the piston. This provides the steering assistance. The speed of movement of the steering system depends upon the flow rate of the steering fluid and the force that the Pitman arm can generate is determined by the fluid pressure. Therefore, the sizing and condition of the hydraulic system is a key factor. The pressure at the outlet of the steering pump (hydraulic pump) that is installed onto an engine PTO somewhere at the front of the engine, should be 1800 – 2200 psi. The capacity of the pump, the sizing of the hoses and the restrictions in the steering box valves will determine the flow rate that will occur. The steering fluid temperature will rise due to flow through restrictions. The fluid also cushions road vibrations that might reach the steering shaft via the steering box, which will heat the fluid. The more steering activity, the more temperature will be produced.

CYLINDER HEAD

RELIEF PLUNGER

(4) PISTON RACK TORSION BAR

(2) ROTARY VALVE SHAFT BALL THREAD

BEARING CAP

(1) ACTUATING SHAFT

(3) SECTOR SHAFT

(5) PISTON RING