12 minute read

HYDROGEN COMBUSTION ENGINE VS FUEL CELL

PowerTorque’s European Correspondent, Will Shiers, takes a look at two very different hydrogen trucks with the same end goal.

To tackle the stringent European Union CO2 emissions standards that come into play in 2025 (a 15 per cent reduction) and 2030 (a 30 per cent reduction), truck makers are rapidly developing their zero tailpipe emissions vehicles.

While most seem to agree that battery electric trucks will play a considerable role in cleaning up urban deliveries, the cost and weight penalties of batteries seriously restricts their suitability for long-haul transport. For this, it is widely accepted that hydrogen gas (H2) will play a significant role.

But, as I discovered on two recent press trips, the manufacturers are divided on how best to use hydrogen. It appears that a VHS versus Betamax battle is on the cards.

The two methods in competition are hydrogen fuel-cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) and hydrogen internal combustion engines (H2-ICEs). The former uses a fuel cell to convert stored hydrogen to electricity, which powers an electric motor. It works in conjunction with a small battery.

DAF’s XF Hydrogen won the International Truck of the Year ‘2022 Truck Innovation Award’.

Meanwhile an H2-ICE is a modified combustion engine, which uses stored hydrogen as a fuel. Daimler’s MercedesBenz claim FCEVs are the future, and is just five years away from putting one into series production. In the other corner is Paccar’s DAF, which is currently putting its weight behind H2-ICE’s.

DAF XF HYDROGEN The XF Hydrogen 4x2 prime mover is the product of a collaboration between DAF and the Dutch government, and according to DAF’s Executive Director of Product Development, Ron Borsboom, is a work-inprogress. “The idea was to build a working vehicle, and increase the knowledge base,” he explains.

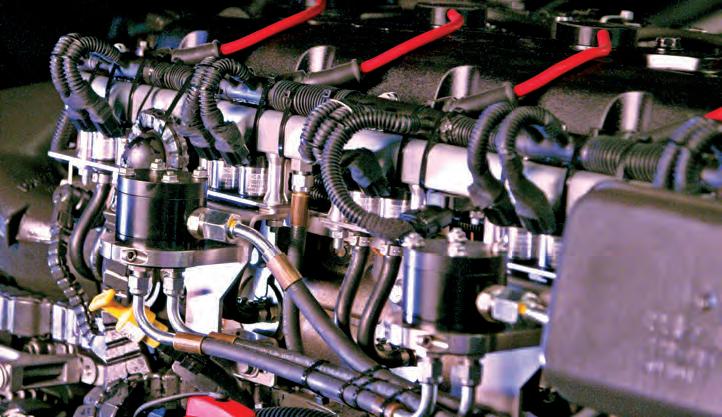

The New Generation truck is equipped with a heavily modified Paccar MX13 13-litre engine, with new pistons, different compression ratios, a revised combustion chamber, and spark plugs instead of diesel fuel injectors. This means it has more in common with a petrol engine than a diesel engine.

Although this first example uses a port injection system, Borsboom says this has seriously limited power (200hp) and torque levels (1,000Nm), and confirms that later derivatives will utilise direct injection instead. DAF is currently trialling such a system at its engine development centre, and has already achieved a 270hp rating. In the future this is expected to increase to 500hp.

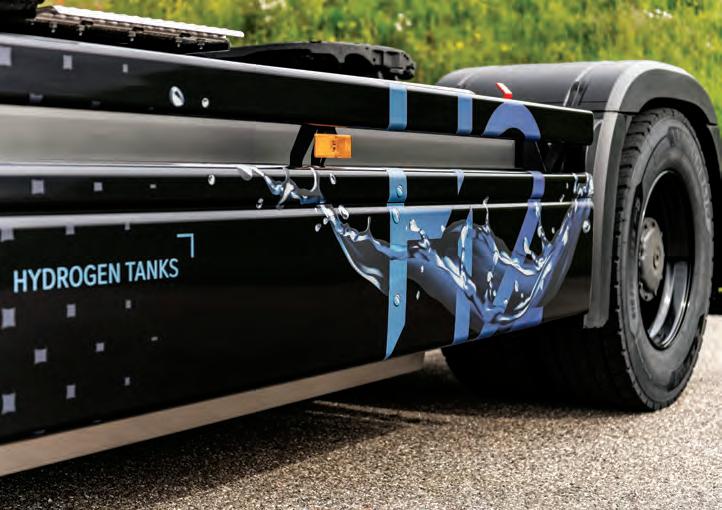

The truck is equipped with four carbon reinforced hydrogen tanks, which together hold 90 litres of hydrogen (350 bar), giving this prototype a 125km range. Later versions will have more tanks, with an anticipated range closer to 600km.

A Paccar MX13 engine, with new pistons, different compression ratios, a revised combustion chamber, and spark plugs.

DAF currently prefers to use hydrogen in gas rather than liquid form. DAF’s Executive Director of Product Development, Ron Borsboom.

Borsboom says DAF currently prefers to use hydrogen in gas rather than liquid form, as it’s easier to store. “But of course we will keep an eye on the research work that is going on,” he adds, explaining that it is developing hydrogen power generation and storage systems in parallel.

Borsboom tells me: “It is important to remember that this prototype is an early example, a first step. But it has potential and we believe in it. In the future, you can expect much more.”

MERCEDES-BENZ GENH2 The Mercedes GenH2 is a hydrogen fuel cell-powered zero tailpipe emission 4x2 long-haul prime mover.

Where you would normally find a diesel engine, Mercedes has installed a twin fuel cell system, each with a power of 150kW (combined 300kW). There are a pair of eMotors, 2x 230kW (2x 1,577Nm) continuous, or 2x 330kW (2x 2,072Nm) peak. In the centre of the vehicle is a high voltage battery, with a capacity of 72kWh.

Roland Dold, Head of Advanced Engineering for Alternative Drives and Alternative Fuels at Mercedes-Benz Trucks, tells me that a huge amount of research has gone into deciding how big to make the fuel cells and battery to minimise hydrogen consumption.

“If you make the fuel cells smaller it is not a good idea, as consumption will go up significantly. And if you make the battery smaller it will have the same effect, increasing consumption and reducing the lifespan of the battery,” says Roland. “If you make the battery bigger you won’t see any significant improvement in consumption, and there will be challenges accommodating it. If you make the fuel cell bigger, you also face packaging challenges, with no significant fuel consumption benefit. It has been a real challenge for our engineers, but we believe we found a very good combination.”

Along the chassis rails on either side of the truck are stainless steel vacuum tanks, each containing 40kg of liquid hydrogen.

“The main advantages of liquid H2 [as opposed to compressed] is that it’s light, has a high energy storage density, and does not need 1 tonne of expensive carbon fibre,” explains Roland.

Behind the cab is a 600mm ‘building block’, housing auxiliary equipment and cooling fans. This extends the length of the truck from a standard 16.5m to 17.1m, which deems it over-length by European standards. But Mercedes is currently in talks with regulators, and is confident of receiving dispensation, allowing it to be trialled on public roads soon.

PROS AND CONS Having spoken to these two experts, it’s clear that both systems have their pros and cons. A good example of this is with pollution.

While carbon emissions from

hydrogen production varies wildly, a FCEV offers zero tailpipe emissions. This is one of Mercedes’ strongest arguments for adopting the technology. “If you use hydrogen in a combustion engine, you produce nitrogen, so are not emissionfree,” explains Roland. “Yes, you could fit an after-treatment system, like with diesel, but we believe if future trucks are going to get broad acceptance from the general public, they shouldn’t have combustion engines.”

Ron Borsboom points out that the level of NOX produced is 90 per cent less than Euro-6 requirements, and for this reason the XF Hydrogen currently does not require an after-treatment system. But he acknowledges that as power levels increase, so an after-treatment is likely to be required. ON THE ROAD IN THE DAF I had a five-minute drive of this prototype on private roads at DAF’s Eindhoven headquarters. From behind the wheel it looked and felt very similar to a dieselpowered New Generation XF. However, it sounded more like a gas-powered truck. I was assured that in time noise levels will reduce significantly, and ultimately it will be marginally quieter than both diesel and LNG/CNG. This being an early prototype, the integration of the engine and transmission was slightly crude, with a few notable clunks and jerks. But overall, the driving experience was impressive, and running solo, the 200hp 4x2 tractor, accelerated smoothly. It’s important to remember that this is a very early prototype, and just a taster of things to come.

He disagrees with Roland’s public perception argument, believing the opposite to be true. He compares the harmless water vapour generated by fuel cell trucks to the steam emitted by cooling towers. “You and I know that’s just water vapour, but it doesn’t stop the news channels from showing them to depict pollution. It’s all about perception,” he says.

Four carbon reinforced hydrogen tanks hold 90 litres of hydrogen at 350 bar.

We also need to consider the cost and weight arguments. While both systems are likely to have eye-watering price tags (the most expensive part of any hydrogen-powered truck is the storage system), FCEVs also require batteries, which of course come with weight and cost penalties.

As Ron is keen to point out, high power fuel cell trucks also require significant cooling. He says: “You need all sorts of additional complex cooling equipment mounted to the back wall of the cab. This sucks up a lot of energy and makes plenty of noise.” He explains that the New Generation DAFs have been designed for maximum cooling, but not even these have the ability to provide sufficient cooling for a fuel cell.

Then there’s power and range. The figures speak for themselves on this one. At 580kW (the equivalent of 790hp), the GenH2 is Mercedes’ most powerful truck, and will no doubt have to be downrated when it goes into production.

Whereas at 200hp, the first XF Hydrogen, would struggle to pull the skin off a custard! But, as Ron points out, the technology is in its infancy, and more powerful versions will follow. Likewise, Mercedes expects its GenH2 to cover 1,000km between fills, while DAF’s anticipated range will be roughly half that distance.

Of course, unlike the great battle of the video tape formats, there doesn’t have to be one winner here, and both technologies can and probably will coexist side by side.

As for my personal opinion, I reckon H2-ICE makes the most sense. As the industry gradually turns its back on fossil fuels, so it’ll no longer be reliant on the Middle East fuel suppliers. Everything needed to manufacture and run a hydrogen ICE-powered truck can be sourced in Europe. Why start relying on the countries that mine/own the minerals that go into batteries instead? Europe is rather good at making combustion engines, and long may that continue.

ON THE ROAD IN THE MERCEDES I had brief ride in the passenger seat of GenH2 truck at Mercedes’ test track in Worth, Germany. This prototype vehicle featured a visual display showing the energy flows, and as we started, I could see the energy transferring from the battery to the drivetrain. Then, as our speed increased, so the fuel cell kicked in. Listening carefully, I could hear the electric turbo chargers doing their thing. Other than that there was no clue that the switch had been made. Pressing the brake pedal resulted in the regenerative braking replenishing the battery. There is also a five-stage ‘engine brake’ for want of a better word. It is basically the electrical motor operating in reverse. With the accelerator pushed firmly to the floor, the fuel cell and battery work in parallel, delivering peak power. Doing my best Elon Musk impression, I clocked the 40-tonne outfit race to 85km/h in just 30 seconds. Hill starts proved no challenge for the GenH2, with us stopping and starting half way up an 18 per cent gradient. The truck has a 2-speed transmission, and it selected first gear for this climb. In the MirrorCam screen I noticed water vapour exiting the fuel cell, which it does at temperatures ranging from 40C to 60C. The colder the external temperature, the more water vapour is emitted. Production trucks will feature a reservoir to collect the harmless water. During the hill starts the cooling fans located behind the cab kicked-in, creating quite a racket. I was assured that these wouldn’t be as obtrusive by the time the truck goes into series production.

TALKING TO A HYDROGEN SCEPTIC

Will Shiers, PowerTorque’s European Correspondent talks to Christian Levin, president and CEO of Scania and CEO of Traton about issues around using hydrogen to power trucks.

Traton Group, which includes Scania, MAN and VW Trucks, believes hydrogen will only be suitable for niche applications, and sees battery electric vehicles (BEV) as the future of long-haul transportation in Europe.

“I used to be an advocate of hydrogen, but have since changed my mind and am more sceptical and realistic,” said Christian Levin, who explained that the company has plenty of practical experience with the fuel, and is currently running hydrogen fuel cell trucks in Norway and Sweden.

“Our belief was that the fuel cell would be the answer, however one huge problem has emerged with these vehicles, and that is the energy inefficiency.”

He explained that from a well-to-wheel perspective a BEV has an overall efficiency rate of 75 per cent. This compares favourably with diesel, which is roughly 50 per cent. With hydrogen, by the time you factor in electrolysis, compression and liquefaction, transportation and filling, fuel cell and power generation, the overall efficiency rate is just 25 per cent.

“So that means that the operating cost of a vehicle is three times higher [than BEV]. And to offset three times the fuel cost is very difficult for most customers,” said Christian. “We have gone into details thoroughly, and analysed segment by segment, application by application, market by market, and we see that the BEV in most applications will always beat the

hydrogen vehicle on TCO. And that is the name of the game.” Christian also highlighted the lack of green hydrogen available, and said that even when production increases, it’s likely to be purchased by chemical companies and the steel industry, who will be prepared to pay more for it. “We agree [with Daimler and Volvo] on most things in the transition to clean energy, but on hydrogen we think they are really over optimistic,” confirmed Christian. “And we don’t think it is fair to tell governments around the world to invest in a hydrogen infrastructure alongside the battery electric infrastructure. We might be wrong, and they IKONPCARD-FRONT1.pdf 3 12/05/2021 2:51:16 PM IKON-card-FRONT.pdf 1 12/05/2021 3:24:48 PM might be right, but that’s the standpoint of MAN and Scania.”

IKON

Lifting solutions for heavy industries...

// IKONLIFTING.COM.AU

ROTARY LIFT

WIRELESS MOBILE COLUMN LIFTS

IKON LIFTING EQUIPMENT PTY LTD

6.2 / 7.5 / 8.5*STOCKED RANGE AVAILABLE: Tonne Capacities 8.5T FLEX-MAX Features:

- All steel control cabinet - Simple display for safe easy operation - LockLight™ load saftey system - Cordless remote control - Spring loaded steering / braking system - Hard rubber covered steel wheels - Digital gauges shows vehicle height and weight - Robust network connectivity

| Nationwide 24/7 service support ..

(03) 9088 6278

sales@ikonlifting.com.au