A Narrative History of The Princeton Public Library

A Community Endeavor

Foreword

Acknowledgements

Princeton’s Nineteenth Century Libraries

The Free Public Library of Princeton, N. J.

The Library at Bainbridge House

Post World War I

Post World War II

The Nineteen-Fifties

A Joint Municipal Library

Friends of the Princeton Public Library

A New Library Building

Addressing the Future

A Tortuous Trail

Expanding Library Activities

Supplementary Financial Support

Finally Addressing the Future

The New Three-Story Library

Appointment of a New Director

Barriers to Overcome

Site Remediation

Parking

Funding

Temporary Quarters

Construction

The Princeton Public Library

The George H. and Estelle M. Sands Library Building

The Community’s Living Room

Appendices

Board of Trustees, 1909-2006

Librarians/Directors, 1910-2006

Presidents of the Friends, 1961-2006

Foundation Directors, 2000-2006

Art in the Princeton Public Library

Over the years we’ve had much to celebrate about our wonderful library: three buildings, a dedicated staff and a strong and committed corps of library supporters in our Trustees, Friends of the Library, Foundation Board and the thousands of people whose contributions of time and resources have made our library successful.

In 2009, we will have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to celebrate Princeton Public Library’s 100th birthday. This milestone will bring the entire community together to celebrate all that the library does to enrich, entertain, inform and enlighten us all. This narrative history is just the first in what we expect will be many ways we honor the library’s centennial. Libraries are the cornerstone of our democracy, institutions that provide free and easy access to information, ideas and enjoyment for everyone in our communities. They are a safe haven for our youngest users who are just learning to read and succeed in school, places of opportunity for those new to our country and those seeking new careers and centers for dialog, a refuge for those who are seeking quiet and solitude among the thousands of stories on our shelves, and centers of understanding for those who come to discuss ideas with others. That is certainly the case here Princeton, where every day our customers tell us how much the library means to them.

Today we are, for the first time in the library’s history, happily serving four generations of users – from those born digital to those who were born before computers and the information age, and everyone in between. As a result, the Princeton Public Library has become the community’s living room, a 21st century salon where everyone is welcome and discourse is encouraged, with an atmosphere where all can learn and grow and have fun.

This narrative will provide you with a glimpse into the library’s rich history over the last 100 years. It is in itself a celebration of a community that cares about and invests in its library. One need not look any further than the list of Trustees, Friends and Foundation Board members to understand how many people have contributed to the library’s success over the years.

We owe a great deal of thanks to our author, William K. Selden, a beloved historian and personal archivist of Princeton institutions, who carefully assembled the facts and turned them into a compelling story for all to read. We are so pleased that he agreed to take on our project, and we welcome him to the library family. He is an inspiration to us all.

— Leslie Burger Library Director —Katherine McGavern President, Board of TrusteesIn writing this narrative history of The Princeton Public Library, I was impressed with the fact that its development and growth since its founding has been the result of a cooperative endeavor involving scores and scores of citizens of this vibrant community. In a similar manner, but on a more modest scale, this publication is a product of the cooperation of individuals directly and currently related to the library in several capacities. Claire R. Jacobus, present, and Barbara L. Johnson, past president, of the Friends of the Princeton Public Library, provided constructive suggestions for an early draft of the manuscript. Harry Levine, a former president, and Katherine McGavern, the current president of the Board of Trustees, were extremely supportive of the project from its inception. Terri Nelson of the staff was helpful throughout the research phase and suggesting sources of information and then offering constructive editoral comments; and Eric Greenfeldt, the former assistant director and construction manager for the construction of the Sands Library Building, and his wife, Barbara, made many editorial and substantive suggestions. Timothy Quinn, the library’s Public Information Director, contributed his expertise in designing and supervising the production and printing of the publication. Kaylie Nelson of the library staff and Margaret Sieck of the Friends of the Princeton Public Library provided proofreading services.

A special acknowledgement appropriately recognizes the support that Leslie Burger extended to all aspects of the writing, editing and printing of this publication. Despite her extensive responsibilities as director of the library, concurrent with the demands of her time and energy as president of the American Library Association, she contributed substantive editorial comments and provided detailed information about the planning and construction of the new library building, information that would otherwise not have been available to the author.

The writing and publishing of this history is truly a cooperative endeavor with which I have been honored to be associated.

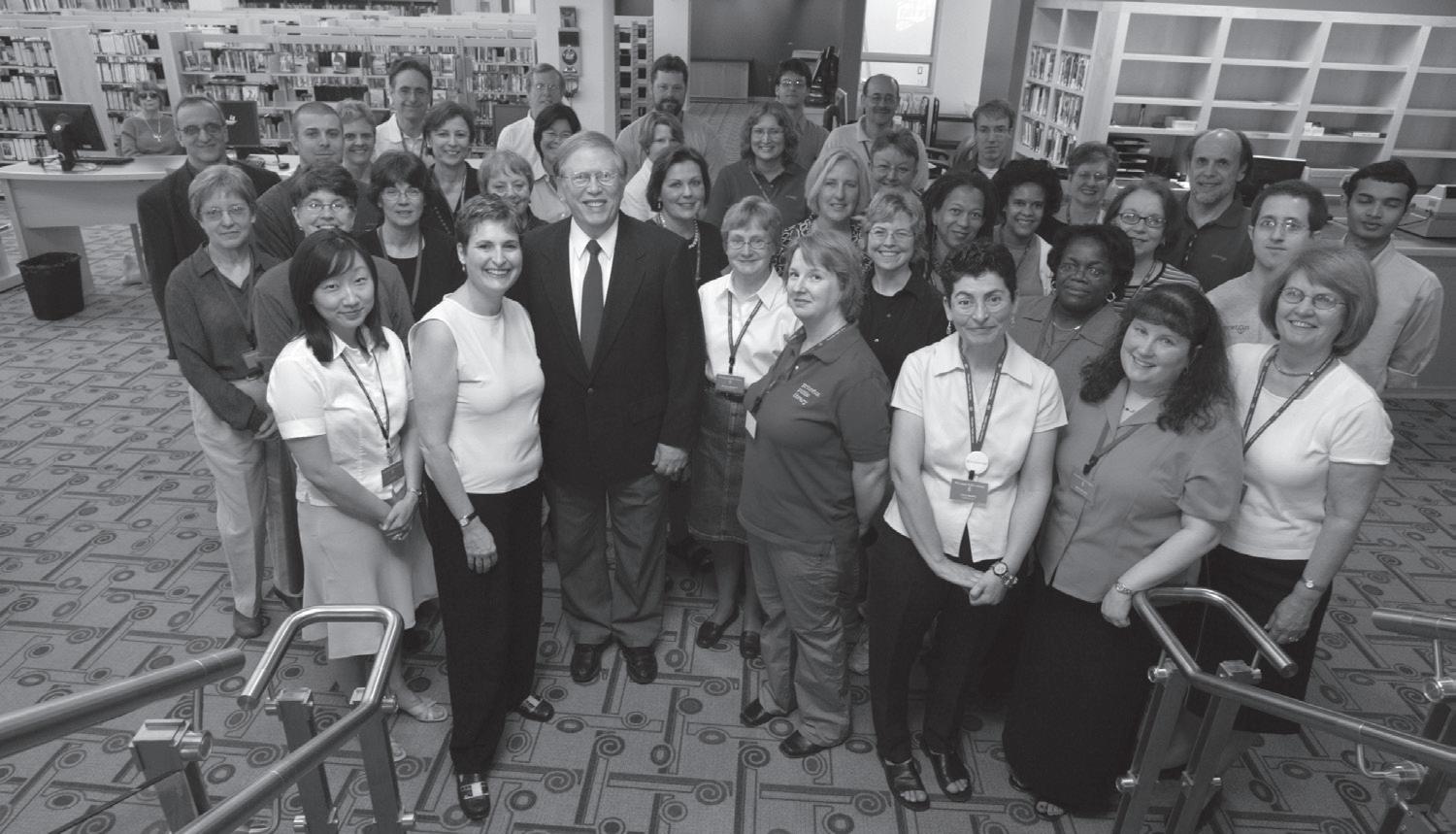

— William K. Selden August, 2007The new, magnificent and architecturally attractive Princeton Public Library is a far cry from the early origins of the library initially organized in 1909 and subsequently established in 1910 in Bainbridge House, a location that a few Princetonians still remember with nostalgia. The current library building has created an atmosphere of quiet repose with its ready access to books and multimedia items on a wide range of subjects, to its unique and extensive film collection, to its many computers and state of the art software and information technology, as well as availability of meeting space that provides accommodation for an outstanding program of events. All these attributes are enhanced by a knowledgeable, friendly and professional staff of individuals who are always helpful in making this a library of which the citizens of Princeton are immensely proud and an institution which is a model of public service for the state and the nation.

No one now remembers the Princeton Library Company whose Laws and Regulations were instituted in April 1812 by a small group of men, local merchants and tradesmen, who pooled their resources to create a collection of 292 books. By 1825 these books were listed in a printed catalog, still extant today, which indicates the diversity of interests at that time: biography, encyclopedias, history, novels, poetry, science, theology, travel and other miscellaneous items. The regulations established yearly membership dues of $1 and a fine of six and a quarter cents for the first week’s default in returning books. The library was open Wednesday and Saturday afternoons each week. It set an example for two libraries established later in the 19th century.

Nor does anyone now alive remember the immediate predecessors to the current library: the Ivy Hall Book Club and the Witherspoon Street Free Lending Library. The Ivy Hall Book Club was founded by Mrs. Josephine Ward Thomson Swann in 1872 and located in Ivy Hall on Mercer Street, a building constructed in 1847 to house the short-lived Law School of Princeton College. Subsequently the library collection was moved to Thomson

Hall on Stockton Street, which had been built by Commodore Robert Field Stockton and became the home of Mrs. Swann. She bequeathed the house to the Borough of Princeton to provide accommodations for its municipal offices and also space for the Ivy Hall Book Club, which contained a collection of some 2,000 volumes and more than 20 magazine subscriptions. It was supported by a group of women who took great pride in its operations and who encouraged additional subscribers, since the acquisition of books depended not only on gifts but on income from membership fees. George A. Armour, a noted book collector, whose home on Stockton Street later became the residence of the president of Princeton University, generously assisted financially in furnishing the rooms appropriate for library purposes.

The Lending Library at 16 Witherspoon Street was the successor to the Princeton Free Reading Room founded in the 1880s for which Professor William H. Green of the Princeton Theological Seminary rented the space and Paul Tulane financed the replenishment of the book collection. In 1897 the Lending Library was founded in the same space and was supervised by three women whose husbands were associated with the Seminary: Mrs. A.Alexander Hodge, Mrs. Henry J. Owen, and Mrs. Geerhardis Voss. Initially open one afternoon each week, by 1900 the library maintained a collection of some 2,000 books, many of which were donated, including those provided by the Philadelphian Society, a religiously affiliated organization of Princeton University students. Even though the library was open only on Thursday afternoons, in a two-year period a total of 4,193 books were lent, a remarkable achievement considering its cramped quarters located on the second floor of a small building at 16 Witherspoon Street. It is these two libraries that were joined to form the basis of the Free Public Library of Princeton, N.J.

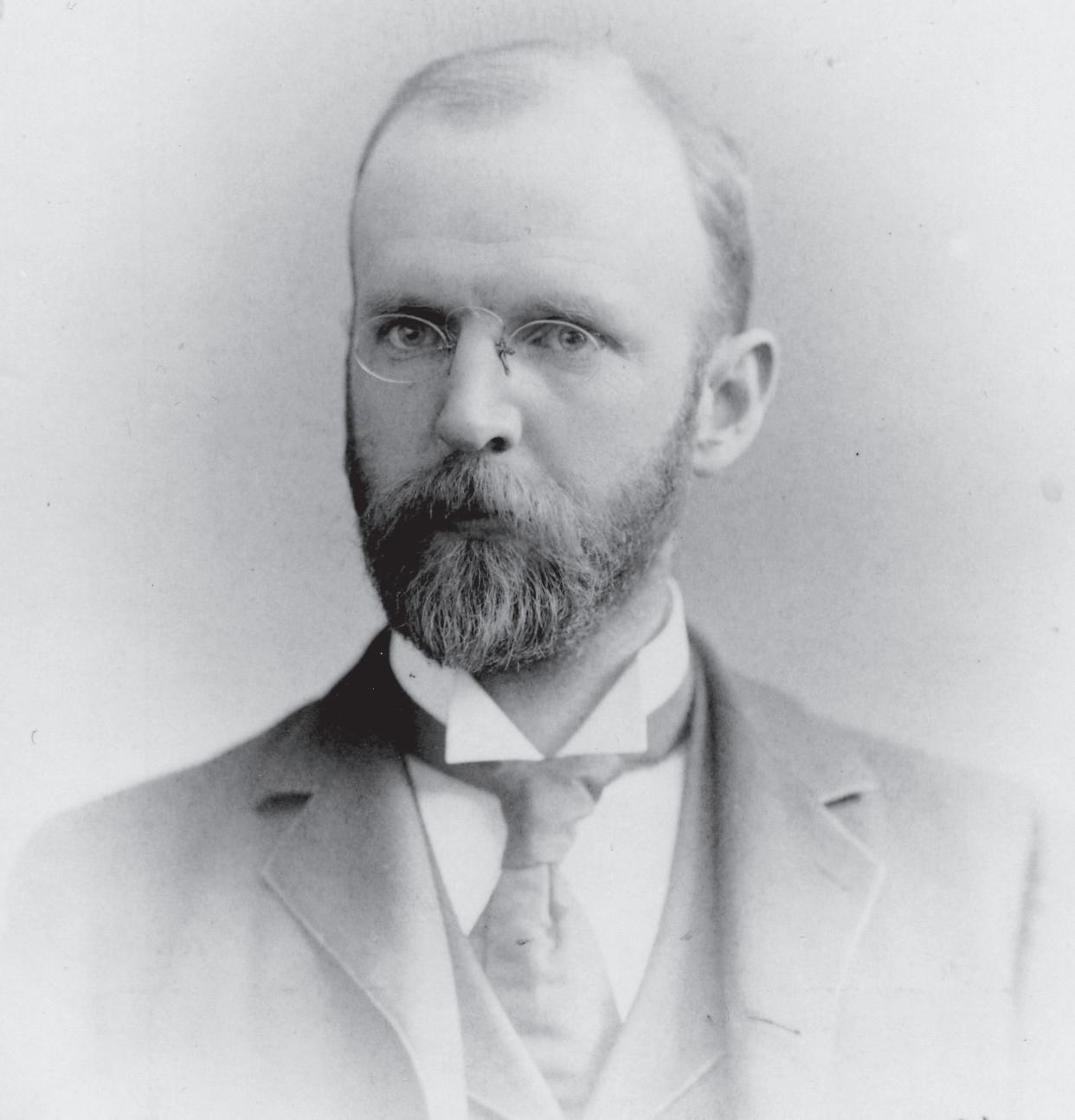

In February 1909 Ernest C. Richardson, the respected librarian of Princeton University and at one time president of the American Library Association, addressed the Princeton Borough Council and proposed that “the time is ripe for combining various elements now existing into one Public Library – not uniting them in one spot but. . . uniting these under one management in a Free Public Library founded under state law.” He noted that in 1884 a law had been enacted that permitted New Jersey municipalities to establish and finance publicly supported libraries. Richardson was convinced that the Borough of Princeton with a population of 5,136, supplemented by the Township of Princeton with a population

Ernest C. Richardson

of 1,178, warranted library facilities that were appropriate for a community with the educational level of its residents.

The following month Dr. Richardson convened a meeting of a committee to establish a public library in Princeton. This committee included Juliana Conover, representing the Ivy Hall Library, Margaretta Paxton, representing the Witherspoon Street Library, and Bayard Stockton, representing the estate of Mrs. Swann. With assurances that the two libraries were amenable to the creation of a coordinated public library, the committee adopted a resolution urging the Borough Council to call for a municipal referendum to create a Princeton Public Library. At the same meeting Dr. Richardson indicated that the University Library would make its books available to properly registered members of the Public Library, and presumably the Princeton Theological Seminary would do the same. At the November election in 1909 the proposal for a Public Library was endorsed by the Borough electorate with a vote of 424 to 97.

The rapidity with which developments occurred at this time stands in stark contrast to the long delays that were encountered both fifty and ninety years later when on each occasion the library undertook to design and construct improved facilities. Within a month

of the municipal endorsement the mayor appointed the first library board, which included Dr. Richardson as chairman, Juliana Conover, the Rev. Walter T. Leahy, Margaretta Paxton, and Charles A. Waite, as well as two ex-officio members: A. T. Ormond, president of the Board of Education, and Harvey L. Robinson, mayor of the Borough. This composition established the pattern of membership of all succeeding boards. It should also be noted that Juliana Conover served on the Board for 31 years, the longest term of any subsequent member. On December 30, 1909 the Free Public Library of Princeton was officially incorporated.

By February 1910 volunteers from the libraries at the University and the Seminary were helping to catalogue the books and on April 1 Miss Agnes Miller, having been an assistant librarian in Madison, New Jersey, assumed her duties as the first professional librarian of the newly established Princeton Public Library. Both library branches were now open each weekday with the Witherspoon Library, however, continuing to operate in severely crowded quarters. Dr. Richardson made several attempts to approach Andrew Carnegie, who was financing the construction of a number of libraries in cities throughout the country, but encountered no success. Carnegie indicated that the citizens of Princeton should be able to finance a library themselves.

By October 1910 a solution for overcrowding at the Witherspoon Street Lending Library was resolved through the generosity of Princeton University. It offered the use of Bainbridge House, located at 158 Nassau Street, on a long-term basis at a nominal charge, later reduced to $1 a year. The books from the Witherspoon branch were moved by November, after the building had been slightly remodeled through the generosity of Moses Taylor Pyne, a noted benefactor of the University, as well as many other organizations in the community. Bainbridge House was designated to serve as the main library, while Thomson Hall operated as a branch library.

Bainbridge House has an interesting historical background that is worth recounting. It was constructed by Job Stockton in the Georgian style of architecture in the middle of the eighteenth century, shortly after the completion of Princeton University’s Nassau Hall in 1756. On Stockton’s death in 1771, he bequeathed it to his brother Robert, the owner and resident of Constitution Hill. Robert Stockton rented the house to Dr. Absalom Bainbridge, whose son William Bainbridge, born in 1774, was later commander of the frigate the U.S.S. Constitution during the war of 1812. The house was subsequently named for the son.

After the elder Bainbridge, a loyalist during the American Revolution, found it expedient to move to New York, the house was occupied in 1776 by Sir William Howe of the British military forces. Eventually its ownership was passed to other Stocktons, including Dr. Ebenezer Stockton, who resided and practiced medicine there until his death in 1838. His two daughters inherited the house, which they were later forced to sell because of financial difficulties. William Van Deventer and then James Van Deventer acquired the property and transferred its title in 1877 to the College of New Jersey (renamed Princeton University in 1896). It was then sporadically occupied by renters up to the time of the occupancy by the Princeton Public Library in 1910. During the long period of 55 years when the library occupied the building, it expanded its holdings, its activities and services to the community to such an extent that within a few years of taking occupancy it was clamoring for more space and better facilities. With the eventual construction of a library building in 1966 the use of Bainbridge House transferred to the Historical Society of Princeton on January 1, 1967.

The first annual report of the Trustees of the Free Public Library of Princeton, N. J., issued in 1910, showed an income of $1,890 of which the Borough contributed $1,550 and

the State of New Jersey $100, with gifts providing the remainder. The total number of books in its collection was 4,887, with contributions from members constituting the largest source of additions, primarily through the Ivy Hall Book Club. The librarian reported : “This is a subscription club of nearly 70 members and adds about 35 new books quarterly. These books are eventually turned over to the library, but are reserved for members of the book club for a certain time.” Following the example of the Ivy Hall Book Club two other similar clubs were soon established with the same principles of operation: the Ivy Hall Junior Book Club and the Bainbridge Book Club.

Supported by a modest librarian’s salary, Agnes Miller, during her 23 years of service, established a number of policies and procedures which were continued many years after her departure in 1933 for reasons of health. In addition to her responsibilities in supervising the daily operations of the library in Bainbridge House and the branch at Thomson Hall, she supervised the cataloging of books in the public schools, including the purchase of a new library collection for the high school; she inspired children to read by supporting the awarding of prizes for submission of the best essays; she managed volunteers and answered innumerable reference questions; she provided books in Hungarian and Italian

languages to the men working on the railroad at Princeton Junction; and she developed traveling library collections for loan at nearby rural schools. Her responsibilities for the daily operation of the two libraries included cataloging some 800 books in the year 1912, the majority of which were donations, and the circulation of 21,897 books to a registered membership of 1,879, of whom 457 were new members that year. She also encouraged the continued support of volunteers and a growing cadre of library friends, who over the years would prove to be an ever expanding community source of supplementary financial aid for the library operations.

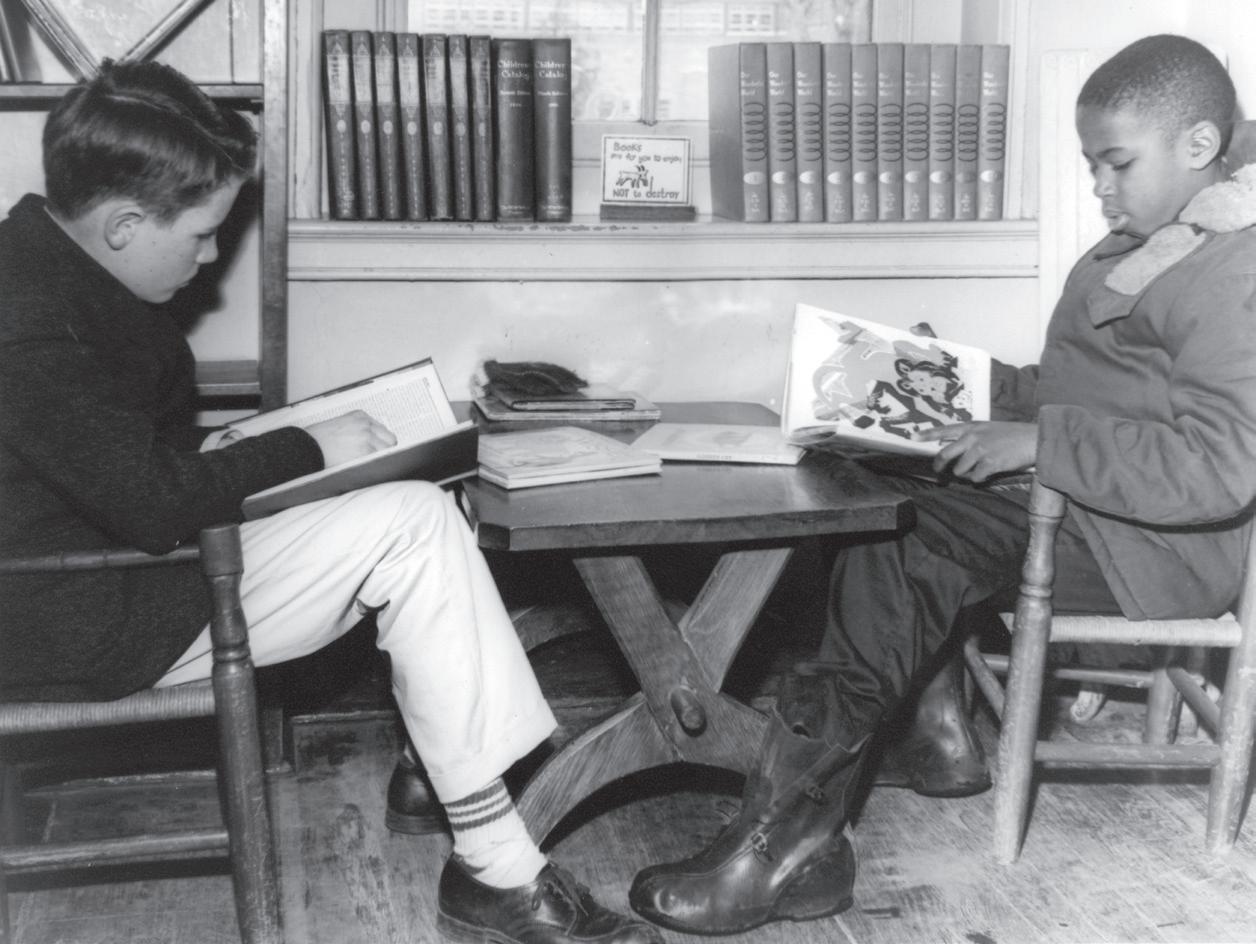

By 1914 Agnes Miller had encouraged the formation of reading clubs, which met regularly in the library, and the establishment of collections of books at the YMCA on Witherspoon Street for use by the African-American population. In addition, she was the supervisor of an assistant librarian in the high school whose salary was paid by the Board of Education.

Physical improvements to Bainbridge House were added at this time. A work room, a reading room for patrons, and a lavatory were added to the first floor, and the apartments on the second floor were renovated for rental. On the exterior, a large overhead gas lamp was installed to illuminate the entrance, only to be replaced when electricity was introduced to the building two years later. During this period a Public Library Bulletin was inaugurated to disseminate information about developments at the library, followed a year later by the suggestion that a Princeton Public Library Aid Association be created to receive contributions to build a new library.

In 1916, prior to the United States entry into the first World War, the sources of income for the library included $1,800 from the Borough of Princeton, $351 from rental of apartments and $793 from miscellaneous sources. The yearly circulation of books had reached 30,566, plus subscriptions to 25 magazines and six newspapers, while 659 books were added, a majority of which were gifts. To raise money for the book fund the Dramatic Association of the Princeton Preparatory School initiated the custom, later revived by other youth organizations, of presenting a benefit performance which netted $166.

During the years 1917 and 1918 the war affected the Princeton Library. Books were packed and shipped to military camps in the United States, as well as to the forces in France. The assistant librarian was granted a year’s leave of absence for war work; the library director was granted a three months leave to serve as a hospital librarian at Fort Dix. And near the end of 1918 the libraries were closed because of the rampant influenza epidemic – a grim time for libraries and the country.

Once the war ended recurrent issues related to inadequate library space emerged for frequent discussion, during which the Board members constantly referred to it as “Our Building Problem.” In 1923 a fair was held to raise funds, amounting to $1,700 for library operations, and a group representing 14 community organizations met to consider a proposal to raise funds for a new library. That same year Miss Miller had noted, “we have outgrown our present quarters and need a modern library building with room for all books under one roof, the building to be open all day and every evening, situated in the center of the town, with an auditorium and committee rooms, and a rest room for out-of-town visitors.” What a prescient librarian Agnes Miller was! She also proposed installing gas heating in place of coal, but the fulfillment of that suggestion had to wait for later years.

During the remainder of Miss Miller’s tenure, more space was made available for children’s books. They were soon moved to the front rooms on the second floor where one of the two rented apartments had been located and where electricity was installed. The library sponsored an adult reading club, story hours for children, a camera club, flower arranging contests, and art classes. Books were also made available to the Princeton Hospital which had been organized during the recent war, and community organizations were finding the library to be a convenient place in which to hold their meetings.

By 1934 the yearly circulation of books had expanded to 45,538, with 650 names added to the membership list. The Borough appropriation was now $5,000, which prompted Charles R. Erdman Jr., mayor of the Borough, to propose that an annual financial contribution be made by the Township. In return for the Township Committee’s contribution Mayor Erdman suggested that the Township should be authorized to appoint three members to the Board of Trustees. This proposal preceded by 25 years the establishment of a joint municipal board of trustees for the library.

For several years consideration had been given to closing the Thomson Hall branch which had been reduced to one room. Finally in 1935 the change was made despite the protests of some members of the Ivy Hall Book Club, and all of the branch’s books were moved to Bainbridge House. To accommodate this added collection some physical improvements were introduced, which interrupted the operations of the library several times for periods of a month or more. These improvements included new shelving, floor painting, roof repairs, and strengthening of the walls and foundation. On each occasion it was necessary to undertake the laborious task of rearranging the book collection.

Despite these interruptions by 1937 the library collection included 9,700 books for adults and 3,670 for children, a total of 13,570, with an operating budget of $11,200. Incidentally, one of its most sought after books, Gone With the Wind, had at one time a waiting list of 60 members. To meet this total demand it was necessary to call on the University and the county library for help in providing additional copies of books from their collections. The Bainbridge House Library faced daunting challenges in its crowded condition resulting in loss and destruction of reference material and periodicals, which were subsequently moved to a place adjacent to the check-out counter for better supervision. A perennial problem, which has been repeated many times in subsequent years, was the exuberance and rowdiness of boys and girls congregating in the library after school hours, an especially troublesome problem in the confines of Bainbridge House.

During the latter years of Miss Miller’s incumbency, which were plagued with her ill health, and during the years of her several successors (Helen Cottrell, Helen B. Harris, Frances K. Moore and Adeline Agar), the library enjoyed the assistance of loyal volunteers, as well as a larger staff. The staff now included a chief cataloger, a children’s librarian, an assistant librarian, a clerical assistant and a janitor. Despite the fact that several of these positions were part time, it is now difficult to comprehend how they could have conducted the increasing functions of the library in the limited space provided by Bainbridge House.

To accommodate these activities the rental of the second apartment was discontinued and the location of various functions were relocated within the building. The first floor provided two rooms for adult reading, a student study room, and the main withdrawal desk, while the second floor accommodated the children’s books and their catalog room, as well as the librarian’s office. With the exception of a modern delivery desk and a few inexpensive chairs, the library depended on cast-off furniture from generous patrons. Books were stored in the attic, as well as in the damp basement where on occasion water caused irreparable damage.

Despite the exigencies incurred by the Second World War, the library continued to operate in its usual manner while it initiated other new services, such as conducting classes from the schools in library use, establishing a book collection at the YWCA, relying on the Boy Scouts to collect unreturned books, and revising the card catalog, a major undertaking. Statistical reports for the library continued to record the number of books received, books cataloged, books lost, books mended, books discarded, books loaned to schools, pictures circulated, names of borrowers and borrower cards issued. All of this, added to its other

activities, had to be accomplished in the hours from 10 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days each week on an annual budget of $10,400.

In recognition of the financial needs of the library, a small endowment fund was established and, in addition to other donations, a trust fund in the name of Richard James Cross provided a small but steady income. These were the harbingers of future activities involved in constructing a successor to Bainbridge House.

By 1944 Mrs. Agar resigned and Helen E. Wilmot held the position of librarian until 1948, when Dorine Harper was designated as her successor, a position that she held for only two years. By that time the annual circulation attained a yearly total of 81,455, the number of individuals enjoying library privileges was estimated at 4,379, and the yearly budget had grown to $23,197. It was during this post-war period that a music record collection, initially selected by Professor Roy Dickinson Welch of the University, was established with annual gifts from Mrs. William Kelly Prentice. Following the introduction of the phonograph record collection, an art reproduction collection was established and the lending of art was added to the responsibilities of the staff.

The growth in population in Princeton following the war appreciably affected the demands on the library. By 1950 the population of the Borough had reached 12,230 and the Township 5,407, causing the Board of Trustees to review its policies of extending library privileges to non-Borough residents. Shortly thereafter non-Borough residents were assessed charges for borrowing books, a development that caused a temporary decrease in the number of books borrowed.

Concurrent with the appointment of Jane S. McClure as librarian in December 1950, other events of significance occurred at the Princeton Public Library. Mabel V. Eldridge retired after 15 years as a member of the Board of Trustees, the latter years serving as president. In recognition of her service, the Board adopted a resolution which reported on its collective perspective on recent developments at the library.

During the 15 years of her administration the library has far more than doubled in size and service to the public. From occupying only the lower floor of Bainbridge House it has expanded far beyond the capacity of the building. The periodical room, the children’s department, and the stacks have been created. The rooms have all been reconditioned and made attractive with redecoration, and more comfortable with new furniture and lighting. The collections have been rearranged, the catalogue revised, accounts and records put in order, and bylaws drawn up. The morale of the staff has been sustained, and everything done with the resources of the library to make it attractive and useful to the readers. At all times the administration has exercised economy and detailed care of the finances. For all this achievement Mrs. [Mabel V.] Eldridge deserves the highest credit. For her generous and tireless devotion to the interests of the library she has spent without reckoning her time and energy and thought, overlooking none of the thousand details involved in the responsibility of her office.

In addition to reporting on recent developments, this resolution also implied the manner in which the Board of Trustees operated, a note of which Dr. Joseph L. Wheeler included in his report of a study of the library that the Board authorized to evaluate the need for a new library building.

Dr. Wheeler, the retired director of the Enoch Pratt Library in Baltimore, presented three observations in his report. He observed that the library had poor facilities; that the staffing level was insufficient in size to meet community needs; and that the board was too dominant in the daily operations of the library. The minutes of the frequent meetings of the board clearly indicated that the members’ concern for “Our Building Problem” encouraged

them to discuss and decide the most detailed operational issues that should normally have been delegated to the librarian and staff.

The most significant recommendation presented by Dr. Wheeler was captured in one sentence: “It is out of the question to postpone longer active consideration and active steps to secure a modern, efficient, adequate, streamlined, economical public library building for Princeton.” He stressed that a new library should be located in the center of the community — between Palmer Square and Vandeventer Avenue.

In spite of the increasing attention given during the 1950s to the issue of a new building, the daily operations of the library were maintained and expanded. Concerns for the physical condition of Bainbridge House were addressed: a new oil burning furnace and a new roof were installed; the exterior and the interior of the building were painted; new lights were placed in the reading rooms; and an exterior fire escape installed. A significant addition was the acquisition of electric charging machines to facilitate the circulation of books. At the same time unforeseen events included the appearance of termites and the break in a water main that flooded the basement.

While these physical improvements were introduced, the daily library programs were continued. In addition to the constant circulation of books and recordings, which by 1956 had reached a yearly circulation of 131,093, discussion groups, storytelling sessions, weekly music sessions, and lecture series were sponsored, and the public school teachers were invited by individual letters to remind their students of the benefits to be gained by the use of the library facilities. The 40th anniversary of the founding of the library was celebrated by the printing of a widely distributed brochure and an open house which attracted a large attendance of library supporters.

While the daily operations of the library were maintained and the issues related to the physical condition of the building addressed, other events were transpiring. Jane McClure resigned as librarian in the spring of 1954 and was succeeded later in the year by Margaretta Barr. At the same time the important issue of Township cooperation in the administration of the library was being addressed.

During the decades of the 1940s and 1950s the population of both the Borough and the Township had been increasing, with the growth of the latter expanding at a much more rapid rate. In 1940 the population of the Township was half that of the Borough. By 1960 the total population of the two municipalities was 22,174, while the Township had only 1,500 fewer than the Borough, and by the next decade the Township surpassed the Borough. In recognition of this trend, by the early 1950s the Township was invited to appoint a resident to participate as an officially invited guest in the deliberations of the Board of Trustees of the library, an action that preceded the formal establishment of a joint municipal library.

Meantime, a Library Advisory Committee was organized which included among its members William S. Dix, librarian of Princeton University; Kenneth S. Gapp, librarian of the Princeton Theological Seminary; and Roger McDonough, director of the New Jersey State Library. This committee noted in its 1958 report to the Board that (1) the present building was totally inadequate; (2) the University library was no longer able to render adequate services to local residents; (3) more equitable representation of the Township should be provided in the governance of the public library; (4) the pressing issue of library expansion should be addressed to meet the projected needs of the community of Princeton; and (5) no present building, one that should be in the central part of the community, was suitable for conversion for library purposes.

At the same time, many community organizations and individuals were expressing impatience with the status of a new building and calling for action. The League of Women Voters and the Junior Chamber of Commerce offered their services in publicizing the need for a new library, and the Council of Community Services urged action on the creation of a new organization which became the Friends of the Princeton Public Library. Concurrently in 1959 the State Legislature adopted legislation that permitted the establishment of a joint municipal library. Accordingly the two municipalities called for a referendum in the fall of 1960 on the question of creating a jointly operated library. The issue was overwhelmingly approved by a vote of 2,478 to 501 in the Borough and 3,575 to 340 in the Township.

In January 1961 a Certificate of Incorporation had been adopted which called for a Board of Trustees whose membership would follow the pattern established by the Borough in 1909. The new Board included the Mayors of the two municipalities, three citizens of each municipality appointed by the respective Mayors, and the Superintendent of Schools of each municipality. The budget of the library was initially divided between the municipalities on the basis of their respective previous year’s library circulation, a policy soon changed to the ratio of ratables on their respective taxable real estate. The name selected was “The Joint Free Public Library of Princeton Borough and Princeton Township.”

Soon after it was organized the new board agreed on the following sequence of events for a new library building: the choice of an architect, the choice of a site, and the development of a plan for a new building — in that order. To assist in their deliberations, the board again solicited the advice of William S. Dix, Kenneth S. Gapp, and Roger McDonough, as well as Joseph L. Wheeler and Neal Harlow, director of the University Library School at Rutgers University. After a deliberate and thorough review on the part of the full board, by the fall of 1961 Thaddeus Longstreth was engaged as the architect for a new building, and Emerson Greenway, director of the Free Library of Philadelphia, was engaged as a professional consultant to provide guidance for the building program.

With continuing assistance of the members of the advisory committee and the architect, plus other professional consultants, the board considered over 20 sites and finally selected property on the southeast corner of Witherspoon and Wiggins streets. Here, a small adjacent piece of property, which provided additional space on which to construct a new library building, was also available for purchase. It was also contiguous with a convenient public parking lot that could be used by patrons of the library.

After many meetings and the involvement of numerous individuals and community organizations, in 1963 the Board of Directors approved the plans for a 30,400-square-foot

building, and requested the Borough Council and the Township Committee to provide $973,000 for its construction. This amount included architect’s and other fees, a contingency fund, and $100,000 for furnishings. This last sum was coincidentally provided in the will of Mrs. William L. Ulyat, who died in 1964. At this time Charles Robinson also left a generous bequest to the library, one of many that from time to time demonstrated the continuing support of the citizens of Princeton for their community library.

Two years previously the Women’s Club of Princeton had contributed one of the first of many donations to the Library Building Fund, and an example for others was established by Mr. and Mrs. David Ludlum, who initiated their annual gifts toward a book fund in memory of their daughter.

These donations coincided with the establishment of the Friends of the Princeton Public Library. This organization has continually encouraged wide community support for the library and has also contributed tens of thousands of dollars as a supplement to the library’s general operating expenses that are annually provided by the Borough and

the Township. In the latter part of the 1950s the creation of the Friends of the Princeton Library was stimulated by the actions of a committee under the chairmanship of Mrs. A. L. Keiser that supported a favorable vote for the creation of a joint municipal library. This coincided with action by the Council of Community Services, which appointed a group of volunteers to consider ways to support the library. Assisted by Mrs. A.W. Sherwood and many others, Mrs. John Wheeler, daughter-in-law of Joseph Wheeler, served as chair of the organizing committee, which led to the creation of the Friends of the Princeton Public Library. Its statement of purpose was approved on January 18, 1960 and its state charter was granted on September 12, 1961, followed by a grant of tax exemption from the Federal Government. The official purposes were: to maintain an association of persons interested in books and libraries; to foster closer relationships between the library and the public; to increase knowledge and understanding of the services and needs of the library; and to stimulate library growth and progress.

It may be noted that this statement of purpose includes no reference to finances. In spite of this omission the Friends’ organization has proven to be a godsend to the library on many occasions in subsequent years. One of its early contributions was the gift of a copier machine. Beginning with this gift and its successor machines, the library has continually received income. Despite the insistence by the Friends during its early years that it was not a fund-raising organization, one on which the Borough and Township could depend for annual operating expenses of the library, the Friends have continued to be a reliable source of supplementary funds. Reference to some of their many contributions will be identified subsequently in this narrative.

In 1962, it was agreed that the library Board of Trustees should not be raising funds but should leave that responsibility to the Friends, whose annual membership had reached 521 with total assets of $4,594. By the following year, the membership had expanded to 670, and a representative of the Friends was encouraged to attend the library board meetings.

The extensive activities of the library continued as plans were being completed for construction of the new building. Among these activities was an innovative program of storytelling related to Asian culture for school-age children, a program that received special recognition from the American Library Association. In 1963 the ALA awarded the Princeton Public Library its John Cotton Dana Library Public Relations Award: “For an outstanding year-round program, which responded to and extended the broad cultural

Groundbreaking for the previous library at 65 Witherspoon Street. From left, Princeton Borough Mayor Henry S. Patterson, library trustees president Nancy Baldwin-Smith and Princeton Township Mayor Carl C. Schafer.

patterns of the community. In particular the ‘Asia Summer’ program ably demonstrates the unique educational role of the library in a changing world.”

In 1965, Margaretta Barr resigned as the director of the library and was succeeded temporarily by Annabelle Bramble, the assistant librarian. In July Robert Staples, who had been an assistant librarian serving under Jane McClure in Summit, New Jersey, assumed the position in Princeton at a propitious time to be involved in the construction of the new library building. After innumerable meetings and various revisions in plans, on June 21, 1965 a groundbreaking ceremony was held at which Borough Mayor Henry S. Patterson, Township Mayor Carl C. Schafer, and Mrs. E. (Nancy) Baldwin-Smith, president of the Board of Trustees, officiated.

Despite the inevitable issues that arise in construction, progress of the new library was relatively rapid. In January 1966 a roof-topping ceremony was held and by November 19, 1966 Bainbridge House was closed to allow time for the books and equipment to be transferred to the new Joint Free Public Library of Princeton, which was officially opened at a well-publicized ceremony on December 5, 1966.

It should be noted that early in planning for the building it was determined that the construction of a basement was inadvisable because of the continued presence of water, a condition that has subsequently plagued the more recently constructed adjacent parking garage. On the other hand, provisions were made for an eventual addition of a third floor, the construction of which was deferred at the time in order to avoid additional costs. Despite good construction and well designed plans there were inevitable malfunctions during the initial years of occupancy. For example, a water valve failed, causing some flooding, the air conditioning faltered, and windows were broken by unknown culprits, but these events were all eventually resolved and the community became accustomed to using the new building. At the the same time an enlarged staff had to adjust to working together in new and expanded space with a larger stock of books, films and records and a growing clientele.

In 1967 the staff included 10 full-time and part-time librarians, as well as 12 library assistants, supplemented by a number of part-time shelvers. The budget had been increased to $198,668, for which the Borough provided $79,467 and the Township $119,201. The inevitable increase in the budget was demonstrated by the total figures for the following year of 1968 — $220,017 to which the State contributed $15,153.

The library collection during this period totaled 58,183 books, 1,493 records, and 67 pictures and an expanding library card registration that represented approximately half the population of the two combined municipalities. At this time non-residents were charged $35 to become members of the library.

In comparison with the 355 public and county libraries in New Jersey, at the end of the 1960s Princeton ranked 13th in terms of total circulation of library materials, and highest in circulation per capita. In one year the total circulation of books and films reached a total of 341,392. Among its multiple responsibilities the library staff continued to conduct frequent film showings, adult lecture series, and discussion sessions for young persons, as well as special summer programs for children. Staff members were answering a variety of reference questions, such as: How does one make a totem pole? What are the dimensions of a human gall bladder? How does one count on an abacus? What is a power of attorney and how is it executed? How tall was George Washington?

In recognition of the library’s new and larger facility, a former member of the Board of Trustees, G. Vinton Duffield, presented to the library a model of its previous home in Bainbridge House, which he had meticulously made with his own hands.

This model is currently on view in the Princeton Room of the new library building. As further demonstration of support of the arts the library in 1968 joined the newly formed Arts Council of Princeton, which now conducts an expanded and active program in its modernized building located across the street on Witherspoon Street and with which the library cooperates in the display of various art exhibits.

In 1923, some 40 years before the Joint Princeton Library was constructed, Agnes Miller had noted that the facilities at Bainbridge House were inadequate. In a similar manner, in November 1970, Robert Staples addressed a memorandum to the Board of Trustees, only four years after moving to the new library building. In this memorandum he stated that “the time has come for the Library’s Board of Trustees and staff to explore and discuss the future, along with Borough and Township officials.”

Referring to its new 30,000-square-foot building, he observed that the Princeton Public Library has now “come into its own as a service agency for the entire community,” and furthermore “the public [has] responded enthusiastically to basic library services at last available in Princeton.” He enumerated the various activities conducted by the staff and identified the improved features that included “adequate seating (45 chairs in the

Children’s Department alone, 135 in the Adult Departments), a Meeting Room, actual shelf space for 60,000-65,000 volumes and sufficient space for various staff activities.” But he insisted that time was passing and soon the new library facility would be insufficient to meet the expanding demands of the increasing population of Princeton’s two municipalities in a rapidly developing technological age. Library consultant Emerson Greenway had earlier predicted that an addition to the library would be necessary within five years of its construction in 1966. This prediction was directly related to the decision not to build a third floor in order to limit expenses.

By 1970 the population of the two municipalities had surpassed 25,000; the book stock had exceeded the available shelf space as it approached 70,000 items; yearly circulation was more than 365,000; and the total of registered members was close to 17,000. With these factors in mind, Staples initiated a library expansion planning process which ultimately involved an agonizing period of three and one-half decades of discussions, negotiations, forecasting, planning, designing, and financing of the replacement of the 1966 two-story library by the new three-story library in 2004.

Over the years, the principal participants in all these activities included the members of the Library Board of Trustees, and members of both the Borough Council and the Township Committee, as well as the Council of the Friends of the Princeton Library and scores of citizens of the two communities. The discussions were intense and sometimes acrimonious with a lack of diplomacy, all caused primarily by several underlying factors — a continuing concern over costs, as well as location, and availability of parking.

Within a year of Staples’ 1970 memorandum the Board of Trustees appointed another consultant, Edwin Beckerman, the library director in Woodbridge, New Jersey, to develop recommendations in library expansion. This action was followed a year later by the first of a series of combined meetings of the Borough Council, the Township Committee and the Library Board to consider a possible solution to the increasing pressures that were affecting the library operations in its present location. Thus began the tortuous trail that lasted for more than three decades before the new three-story library building was completed and occupied.

The first specific action toward space expansion was the reappointment in 1974 of Thaddeus Longstreth as consulting architect, a position from which he resigned in 1979. During this time period he submitted three schematic plans for increasing library space

with estimated costs ranging from $402,320 to $711,000. This report led to another joint meeting of the municipal governing bodies and the Library’s Board of Trustees at which time informal encouragement was given to the Library Board to continue its planning. At this time the board was authorized to seek Federal funding for the construction of a new building, funding that was not forthcoming. Shortly thereafter with municipal approval a contract for $40,000 was signed with Longstreth to prepare an initial design for the library expansion.

As previously noted, the building had originally been constructed with provision for a third floor, should this be desirable. The costs for such an addition were estimated by the middle 1970s to be $753,000 and by 1979 the estimate with solar heating was $910,000. As the estimated costs were growing, discussions also involved an alternative plan: namely, constructing a new building. Although the costs were higher, the additional cost for this latter plan was considered by its advocates to be justified because of the benefits that would accrue. It was recognized that a new building would allow for more efficiency and would provide for the rapidly expanding technological developments that were becoming so important in information searching and retrieval.

The discussion of a new library building stimulated the renewed debate over its location, whether it should be in the present location or in the Princeton Shopping Center. Many residents favored the present location, while some Township residents formed a vocal organization that campaigned ardently for the Shopping Center.

During what became a protracted period of planning all municipalities in the State of New Jersey were experiencing a budget crunch. State officials had placed a cap of five percent increases on municipal budgets which proved to be a very restricting regulation adversely affecting all expenditures, including salaries. Employees were chafing under this regulation, which encouraged members of the staff of the Princeton Public Library to form a staff association. Concurrently, the demands on library services were growing while citizens were objecting to the steady increases in real estate taxes, part of which were appropriated to supporting growing library costs. Municipal officials were advocating library services to be available on Sundays, while at the same time they were objecting to increases in the library budgets needed to meet the additional costs that these services entailed.

It should be emphasized that the governing bodies of the two municipalities, comprising the community of Princeton, were operating under extreme pressures that discouraged them from considering any major capital expenditures. During this time they had to confront the growing pressure for funding of other community services, such as police and fire protection, social services, recreation, trash removal, affordable housing, road repairs, administration, as well as insurance and debt services. During their sometimes tense deliberations the two governing bodies occasionally sparred with each other, even acrimoniously, preventing any serious consideration of library issues, much to the frustrations of the many supporters of the library.

In 1987 Robert Staples submitted his resignation as director of the library partially because of the frustration from the difficulties in administering a library jointly supported by two municipalities with different salary schedules, philosophies, personnel policies and the corresponding problems of communication, and partially from his inability to move forward the planning for library expansion. Within a few months Jacqueline Thresher, a librarian from the Westchester (N.Y.) library system, was appointed director. Equally important, in 1988 Township resident Harry Levine accepted the chairmanship of a Citizens’ Advisory Committee which was appointed to explore the need for an expanded library. The formation of this committee had first been discussed at a Board meeting in 1970 and subsequently proposed to the Board of Trustees by the Staff Association in April 1982.

This 19-person Advisory Committee included members of the Borough Council, Township Committee, Library Board of Trustees, librarians and citizens, including students. Its initial report, issued in the latter part of 1988, concluded that the library is the cultural heart of the community and a valuable community asset, but is inadequately meeting the community’s needs; that it should remain, if possible, at its current site, with public parking available; that a third floor be added with a total renovation of the present building and replacement of aging equipment; and that both the collections and the staff be increased to meet the needs of the community. The costs to support these recommendations were estimated to be $9.4 million to be born by the two municipalities, as well as by funds that were to be raised by a public campaign.

The committee’s report was sufficient to stimulate action that had been in the doldrums for two decades. However, it would still take another decade to coalesce community attitudes sufficiently to support the eventual decision to construct a new three-story library on the current Witherspoon Street site. Meanwhile, as the demands on the library continued to

expand under increasingly crowded conditions, the Board and staff strove to discharge its mission statement in existence at that time:

The role of the Princeton Public Library is the acquisition, organization and provision of access and guidance to a wide variety of information and materials which help to fulfill the intellectual, education, social and recreational needs of all Borough and Township residents.

From the time when Robert Staples first proposed that planning begin for expanded library facilities to meet the future needs of the community until the time when the report from the Citizen’s Advisory Committee was issued — a period of nearly two decades — the total population of the community of Princeton remained relatively stable. However, by the year 2000 the total population had increased to some 30,000 with the Township surpassing the Borough by more than 2,000. This population growth was foretold by the corresponding and expanding demands for library services from registered members who represented nearly two-thirds of the residents of the two municipalities.

In 1970 the total library budget was $277,793 and a staff of nine librarians was supplemented by 12 additional employees. Fortunately in 1985 state legislation exempted libraries from the five percent cap on municipal budgets so that in 1990 the library budget exceeded $1 million. By then, the staff had been expanded to 22 full-time and 21 parttime, plus 12 shelvers. Book stock now totaled 118,524 and the number of recordings had reached 5,118. Circulation remained relatively constant, while nearly 10,000 books were being added each year, and a smaller number were being withdrawn. Increasingly the library collection was thus being jammed into a building designed for half the number of volumes.

As a means of controlling the acquisition of seldom requested books, the libraries in three adjoining counties created a regional association to develop a system of interlibrary loans and other cooperative services. However, this movement did not reduce the pressure on the staff to fulfill its various responsibilities, including the answering of questions, as many as 2,000 in a single month.

Added to all this activity, in a period of one year over 5,000 overdue notices were mailed by a staff that supervised more than 400 language tutoring sessions, and some 200 library programs, including film showings that attracted annually as many as 4,000 people. One of the most popular programs were “Readings over Coffee,” for which Donald Ecroyd

served as a volunteer leader for 22 years until his death in 1985. Volunteers assisted with many services, including delivering books to the home bound and arranging for instruction of English as a Second Language.

To support these daily operational activities, the aging building needed constant attention for maintenance issues such as as its leaking walls and roof, and improvements of its technical operations. By this time library functions were continuously being improved with the introduction of new technology for machine-readable record keeping, an electronic security system, and later the now ubiquitous computers which have so extensively expanded access to informational material. In order to plan properly for the introduction of these technological developments the Board of Trustees relied on various professional consultants.

The Princeton Library was fortunate in the assistance it received from generous local organizations. Among these were Dow Jones, the financial and publication company, which donated several early computers, and funds toward the installation of technology, as well as access to data base information. The Princeton University library provided microfilm copies of various newspapers, as well as access to the Internet and World Wide Web. The Robert Wood Johnson Jr. Charitable Trust made frequent donations, initially to finance the opening of the library on weekends, and the J. Seward Johnson Foundation contributed liberally to help in meeting the expenses of special functions not supported by the municipalities. But it was the organization colloquially known as the Friends that since 1961 has stimulated giving, giving that has helped to maintain those functions of the library which the municipalities have not been able to support and which many of its patrons have taken for granted.

In the early years of the Friends’ organization, as noted earlier, emphasis was placed on encouraging public support for the construction of a new library building. A newsletter was published by the Friends and events, such as its annual meeting, used book sale, and meetings with speakers, were sponsored. After the new library was constructed these events continued, one of which celebrated the 10th anniversary of the founding of the Friends. On this occasion a dinner was held at the Nassau Inn, the announcement for which stated, amusingly in retrospect, that “the charge was $7.50, including one glass of wine.”

These events encouraged both a growth in membership of the Friends’ organization, which in some later years surpassed a thousand individuals and corporations, and of equal

importance an increase in donations. These donations included annual gifts and bequests, all intended for the benefit of the library. With these funds, which expanded over the years, the Friends were able to supplement the municipal annual appropriation for the library. In so doing the Friends were constantly aware that their financial support should not be construed as a means of relieving the governing bodies of their major responsibility; namely, to provide annual financial support for the operations and maintenance of the Joint Free Public Library of Princeton.

In its early years The Friends’ contributions were modest in comparison to its larger donations granted in exceptional years, such as the 25th anniversary of the Friends in 1986 and the opening of the new library in 2004. These gifts, totaling over several hundred thousand dollars, have helped the library expand its services to the residents of Princeton in a variety of ways: installation of a telephone answering machine, a security system, and automation; microfilming of newspapers and magazines; purchase of books, films, and audio books; continuing education for staff; installation of early computers and furniture; financing for consultants; and support for reading groups and youth activities; as well as various other miscellaneous contributions. In 2001 the Friends received the New Jersey

Library Association’s Group Service Award for its record of raising money, including support for Springboard, an after-school tutoring program. Since the construction of the new threestory library the annual Friends contributions have amounted to more than $175,000.

In retrospect one can only marvel at the number of individuals who were involved in one manner or other in the process of planning, developing and eventually financing and constructing the new three-story Public Library of Princeton. Despite the inevitable differences of opinions and misunderstandings that occur when large groups of people endeavor to attain consensus, it was truly an enterprise that reflects most favorably on the community of Princeton.

Scores of individuals were involved in attending innumerable meetings related to action by the two municipal governing bodies that would eventually authorize the construction of a new building: meetings of individuals to review reports prepared by architectural and engineering consultants; meetings of citizens to hear and consider recommendations from fund-raising advisers; and meetings of the Library Board of Trustees to direct all these discussions at the same time that the Board was responsible for overseeing the continuing operations of the Library.

Throughout this period that extended well over a decade Harry Levine, a committed public servant, volunteered his efforts to achieve an harmonious agreement for the construction of a new library building on the site of the 1960s outdated building. As previously noted, he served as chairman of the Advisory Committee and eventually president of the Library Board throughout the period of planning, fund-raising, implementation, construction and finally dedication of the new, magnificent, user-friendly and efficient structure that was planned to be and is the cultural center of the community of Princeton. This was a period of relatively intense activity in planning. Extensive consideration was given to the issues of commissioning a feasibility study and of creating a special committee to lead in the fund-raising to supplement what the municipal governing bodies would be asked to authorize in bonded indebtedness to construct new facilities. Whether an addition of a third floor or the construction of a new building would be the solution, it was recognized that the trends in new library buildings called for such improvements as a more relaxed environment with additional and flexible space to accommodate newer technologies, meeting rooms with a variety of seating arrangements, improved lighting, and a larger inventory of library materials.

In the midst of these discussions and reports from feasibility studies the two governing bodies frequently became bogged down in disagreements over financing and related issues. At the same time the mayor of the Borough injected a further controversial issue into the discussions when he informally explored the issue of Princeton Library becoming a branch of the Mercer County Library system.

In 1994 the two Boards had reiterated their agreement that “all operating and capital costs of the Joint Library shall be apportioned annually between the parties in proportion to the net real property valuations taxable within each municipality as equalized for the apportionment of the County taxes of the preceding year.” And later the same year the Township Committee agreed to the expansion of the Public Library on the understanding that it would remain at the current library site; and it also agreed to make an initial good faith pledge for new construction in an amount equal to the pledge of the Borough, subject to resolution of parking accessibility and satisfactory resolution of operating costs. Despite these resolutions, differences of opinions and attitudes continued to bedevil the two bodies. This was at a time when the total yearly municipal funding of the the library operating budget was soon to surpass $2 million a year.

To maintain the attention of the Borough Council and the Township Committee on the main subject of improved physical facilities for the library, Harry Levine was vigilant in attending their meetings whenever issues related to the library were being considered. As needed, he reminded them of their obligation to reach a mutual agreement as rapidly as possible. Eventually they did — after he addressed a joint meeting of the two governing bodies in July 1995 and stated, “Your lack of speed in resolving this issue [your respective share of the cost of this project] has a direct and significant monetary impact on taxpayers. . . Please resolve your differences, resolve them quickly; let us go forward.”

Although at this point in time many basic issues were yet to be resolved, the movement toward the construction of a new library building on the same site as the old site was accelerated. Over the next few years decisions were made, agreements were reached, and despite the important remaining issues to be resolved the attainment of a new library was now in sight.

Following Harry Levine’s appearance before the two governing bodies in 1995, action toward a new library was accelerated. A fund-raising consultant had assessed the situation and proposed that a tax-exempt foundation be established to raise funds, that a small

group of potential friends be convened to introduce a campaign, and that a development coordinator be employed. As a result, the Board of Trustees of the library authorized “the formation of a citizen’s committee the goal of which is to support the Board as it continues to seek approval from the governing bodies for the project.”

In 1997, the Princeton Public Library Foundation was established as a 501 (c)(3) organization with the sole purpose of securing private support to construct a new library and establish an endowment to support library services. The Library Board of Trustees engaged Sapoch and Company, a local firm with a proven record in fund-raising, to provide professional advice and assistance for the campaign. At the same time A.C. Reeves Hicks, a long-time library supporter, agreed to chair an Expansion Advocacy Committee to inform the community about the benefits of an expanded library and to encourage public support. By 2001, all the necessary approvals were secured that permitted the capital campaign finally to be launched.

While advocacy efforts and public discussions continued there was still a need to continue the day-to-day library operations, as well as to proceed with planning for the new library. By 1998, as a result of technological changes in the library environment, it

was apparent that the previous building plans and studies completed during the early 1990s were outdated. To address the issues a building consultant, Nolan Lushington from Hartford, Connecticut, was engaged to propose revisions in the building program. Because of the long delay in gaining approval for the expansion project, many of the previous building plans were obsolete, especially those relating to technology. Many of the library’s automated functions were in need of updating and could no longer be delayed until a new library was constructed. For example, the need to expand public access to the Internet and World Wide Web was apparent, as was the need to modernize the hardware and software used for managing the lending process. By this time the use of technology in the library was so prevalent that staff were added to oversee the installation and maintenance of this expanding service.

The library’s collection continued to grow to meet community demand and by 1999 holdings included more than 130,000 books, 4,500 audio books, 4,300 films and 2,786 music compact discs. The operating budget that year was $2.23 million. Total circulation for all items was 324,673 with more than 385,000 individual visits to the library. The library maintained a steady schedule of programs that included in that one year the sponsorship of 484 community meetings, and 599 library-sponsored programs. Springboard, the homework help program founded in 1991 to assist children in need of tutoring assistance, was flourishing, thanks to tutors from the Princeton Regional Schools and the Princeton University’s Student Volunteer Council. The Library Outreach programs to non-English speaking adults, the homebound, and nursery school children continued with the aid of a grant from the Princeton Pettorenello Foundation amounting to $10,000.

In 1999, the library once again found itself without a director when Jacquelyn Thresher resigned to accept a position with the Nassau County (N.Y.) Library System. Although this occurred at a critical juncture in planning for the new building the Board of Trustees decided to pursue a carefully considered approach in recruiting a new director who would need to be intimately involved in planning the new library, in securing the funding needed for construction, in managing the transition from the old to the new building, and in directing the operations of a library twice as large as the old building. The board engaged library consultant Leslie Burger, president of Library Development Solutions located in Princeton Junction, to serve on an interim basis until a permanent replacement for the director could be identified.

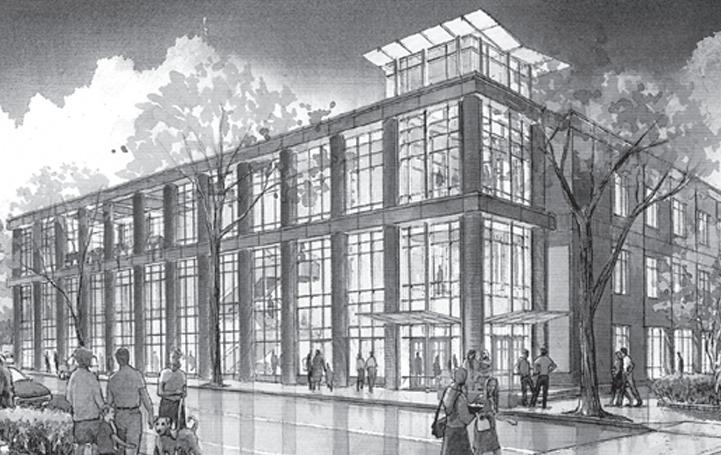

After several months of working with the board and library staff, Ms. Burger accepted the appointment as the 12th director of the Princeton Public Library. To this position she brought considerable experience having been employed previously by the Connecticut and New Jersey State libraries, and the Bridgeport, Connecticut, Public Library. In addition her first-hand knowledge of library issues was extensive as a result of her consulting work in strategic and building planning and organizational development with more than 100 clients. In 1998, the year before she arrived and after extensive public discussion, the Borough Council, Township Committee and Library Board of Trustees had finally agreed that the new library should be built on its current site. Funds were appropriated to engage architectural assistance to evaluate options for expanding the library at that location. Upon assuming her new position, Leslie Burger was immediately involved in the selection of the firm, Hillier Architecture, to complete the feasibility study. A Building Committee consisting of Edwin Beckerman, Leslie Burger, Beth Colvin, Rosalyn Denard, David Goldfarb, Eric Greenfeldt, William Howard, Michael Landau, Harry Levine, Anne McGoldrick, William Murdock, Lauren Seem, and Lee Solow was charged by the board to “review the preliminary design alternatives and associated costs with the objective of making recommendations as to the preferred options among the alternatives presented by the architects.” The Building Committee developed four principles to guide its decision-making: (1) the building should be designed to last for 25 years; (2) the internal design should be flexible to provide for changing programmatic needs during the projected time period; (3) as much land as possible should be preserved for future use; and (4) the building should be cost efficient. Architects from the Hillier team began work immediately to evaluate several expansion options which included an extension to the existing building, construction of a new library in the adjacent parking lot and reuse of the old building, or demolition of the old building and construction of a new library in its place. The Building Committee carefully reviewed each of these options and the associated costs and recommended that the 1966 building be demolished and replaced with a new state-of-the-art 58,000 square foot library. The total cost of the project was estimated at $18 million, some $6 million more than the original 1992 estimate.

At this juncture the Borough Council and Township Committee reaffirmed their original commitment to contribute $6 million towards the construction, leaving the remaining $12 million to be raised privately; and the the Library Board of Trustee retained Hillier Architecture to develop schematic designs for the new library. Nicholas Garrison led the design team, which included Joseph Rizzo, Luis Vildostegui, and Margaret Kehrer.

Simultaneously the library engaged various consultants to provide services for traffic and parking issues associated with the project, as well as environmental remediation, historic preservation, and land surveys.

It finally appeared that the long overdue project was on its way to completion. However, there remained several barriers to be overcome.

Public Service Electric and Gas, which maintained a substation on the property, agreed to demolish the library building, remove all the foundations, and complete excavation for the new library. This decision was prompted as part of a settlement between PSEG and the Borough to provide environmental remediation for the site to comply with a requirement of the State Department of Environmental Protection. A predecessor company to PSEG had used the site to manufacture gas for the Borough streetlights during the early part of the 20th century. The byproducts of this process had contaminated the site. By complying with this governmental regulation PSEG hoped to avoid any future legal claims.

Parking remained a source of contention between the Borough and Township governing boards despite progress toward the design of the new library. The Township wanted guarantees that the Borough would provide affordable, accessible parking for Township residents traveling to the library. After studying traffic patterns and parking options, the Library Board of Trustees requested the Borough Council to allocate 80 parking spots within 400 feet of the library’s entrance to meet the Township’s concerns. The Borough agreed to this request and immediately began to work on developing a solution. The solution ultimately involved the development of a complementary project adjacent to the library; namely, a plan to construct a 500-car parking garage and rental housing.

The only remaining major barrier was the securing of funds necessary to pay for the new library. Fund-raising consultant Jamie Sapoch and Leslie Burger set out quietly to secure a number of six-figure gifts to fund the project. During their visits to prospective donors they described the new library and what it could offer, reviewed the plans, and spoke about the importance of early financial support to keep the project moving ahead. A number of people and institutions stepped forward in these early stages of the campaign

with generous gifts and public endorsements that encouraged others to contribute. The Foundation appointed a campaign committee to sponsor the fund-raising efforts and this committee, chaired by Margaret Griffin, Gordon Griffin, A.C. Reeves Hicks and Joan Hicks, launched the Community Cornerstone Campaign.

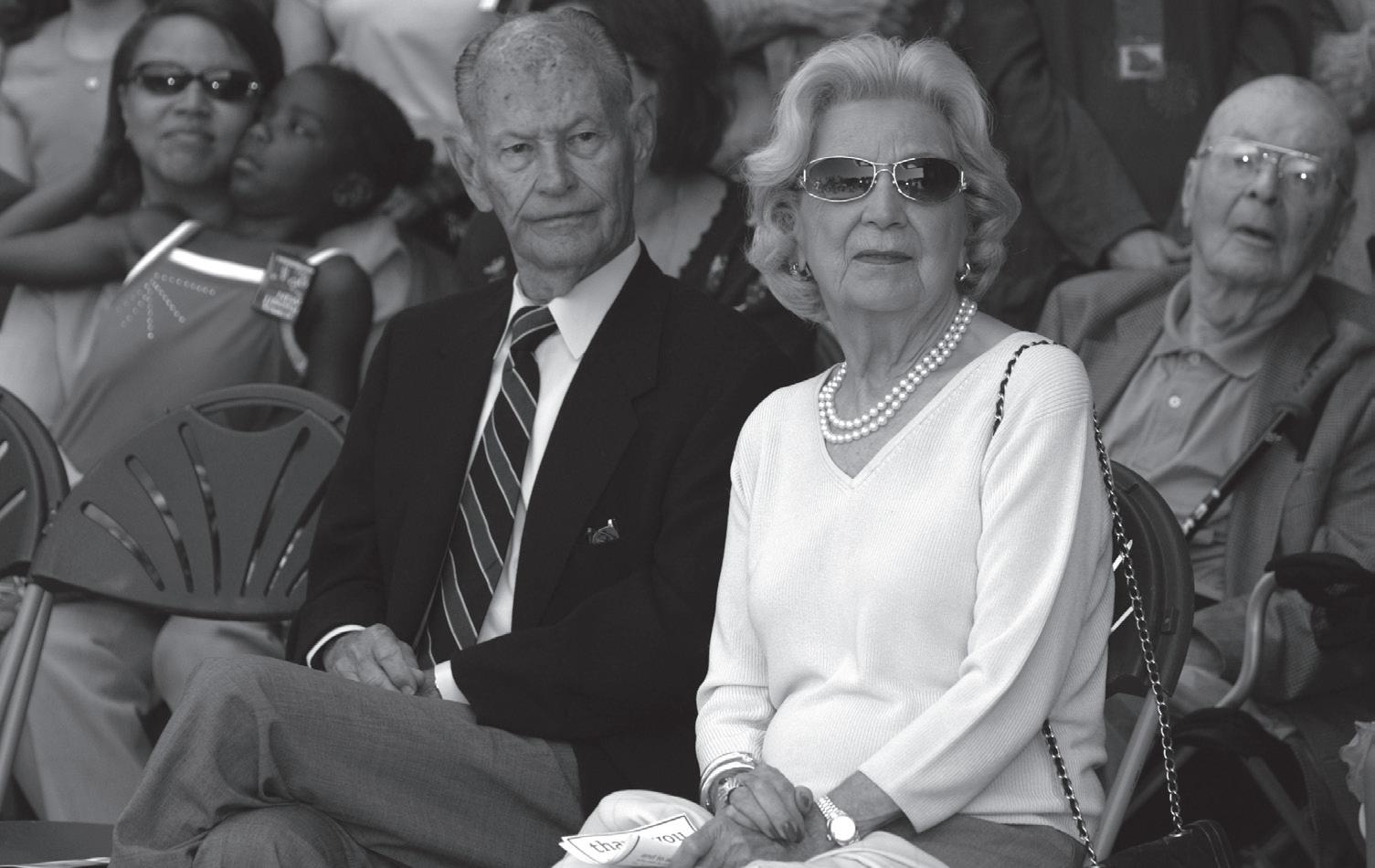

By 2002, the Foundation reported that it had received three gifts of $1 million or more, 24 gifts of more than $100,000 each, and 225 gifts for more than $1,000. The Cornerstone Campaign Committee was overwhelmed by the generosity of the $5 million donation provided by George H. and Estelle M. Sands. One-half of the Sands gift was assigned to seed an endowment and the other half was dedicated to the building campaign with the new library to be named in their honor. An early donation of $500,000 from Princeton University also provided further impetus for the fund-raising effort. Assisted by grants of $2,199,190 from the New Jersey Public Library Construction Grant Program and $100,000 from the U.S. Institute of Museum and Library Service, the full $12 million needed to support the building project was attained within a few years.

It is interesting to note that in addition to the $12 million needed to construct the new building, an additional $284,599 was raised independently to support the installation of permanent art in the new library. The Board of Trustees appointed a 14-member Art Committee to select artist’s work and make recommendations to the Board. This committee of artists, curators, and collectors was chaired by Board Vice-President Nancy Ukai Russell and included Ricardo Barros, Judith Brodsky, Leslie Burger, Penelope EdwardsCarter, Pamela Groves, Patti Kolodney, Rani Malhotra, David Miller, Mollie Murphy, Jeff Nathanson, Louise Steffens, Susan Taylor and Pamela Wakefield. The committee had the responsibility of both commissioning and selecting art work, all of which may now be seen and enjoyed throughout the new library building.

The Sandses’ gift initiated the establishment of an endowment fund for the library with the intent of expanding the fund to $10 million by the time of the library’s centennial in 2009. It is intended that the endowment will provide an ongoing source of income to supplement funding received from the Borough and Township. By the end of the capital campaign in 2004, close to 1,000 donations had been received from Princetonians and other community based organizations in what has proven to be a remarkable community endeavor.

One last hurdle needed to be overcome before construction of the new library could begin. Conservative estimates put the time of construction anywhere between 24 and 36 months. It was clear that Princeton could not survive without library service for that period of time. With available space in Princeton Borough and Township limited at that time, it was difficult to find a location that could accommodate a scaled back library operation. After evaluating a number of options the library secured space in a former bookstore and café at the Princeton Shopping Center. The Witherspoon Street Library closed to the public for the last time in November 2001 and the moving vans pulled up to the front door to move the library to its temporary quarters. The library functioned in this location for two and one-half years in crowded makeshift space that barely accommodated its total collection of 152,108 books, movies, and audio books. Reading tables and chairs as well as desks for staff were crammed into space that barely provided enough elbowroom. However, despite these obstacles, people were heartened by the anticipation of moving to a new more spacious facility with up-to-date books and equipment.