Author Designer

Dedicated to H K Dunston and My Sister, Kranthi Remala, For invoking my interest in chaning the world and showing me how to care the right way!

preface

Author Designer

Dedicated to H K Dunston and My Sister, Kranthi Remala, For invoking my interest in chaning the world and showing me how to care the right way!

preface

On February 10th, 2023, for the Climate Futures class in my term at Products of Design, I presented my manifesto along with my peer Heba Jaleel. It wasn’t until that course and that class that I really knew I had an interest in climate action. Since I was young, my dreams and ambitions were very much towards technology, fashion, travel, and history. Climate was something that I thought was not in the books for me.

However, as I delved deeper into the subject of climate change, I encountered the concept of “slow violence” – a term coined by the literary critic Rob Nixon. Slow violence refers to the gradual and often invisible consequences of environmental degradation, such as the long-term effects of climate adversities - whether natural or manmade. Unlike active violence, which is immediate and visible, slow violence unfolds gradually, making it harder to grasp and address.

One of the key reasons why we often fail to account for the human ramifications of slow violence is the disconnect between the timescales of environmental change and human perception. The effects of slow violence can take years, decades, or even generations to address, making it challenging for individuals and communities to recognize and respond to these threats effectively.

Through this introduction, I aim to explore the concept of slow violence and its far-reaching consequences on human lives and communities. By examining the disconnect between environmental change and human perception, we can better understand why these issues are often overlooked or underestimated. Additionally, by drawing inspiration from works like “Soil Not Oil,” we can shed light on the intricate connections between environmental degradation and the erosion of cultural identities, livelihoods, and human dignity.

Ultimately, this book seeks to amplify the voices of those affected by slow violence and to challenge the dominant narratives that prioritize short-term gains over long-term sustainability and human well-being. By fostering a deeper understanding of the human ramifications of slow violence, we can pave the way for more inclusive and holistic approaches to addressing environmental challenges, ensuring that no community is left behind in the pursuit of a more sustainable and equitable future.

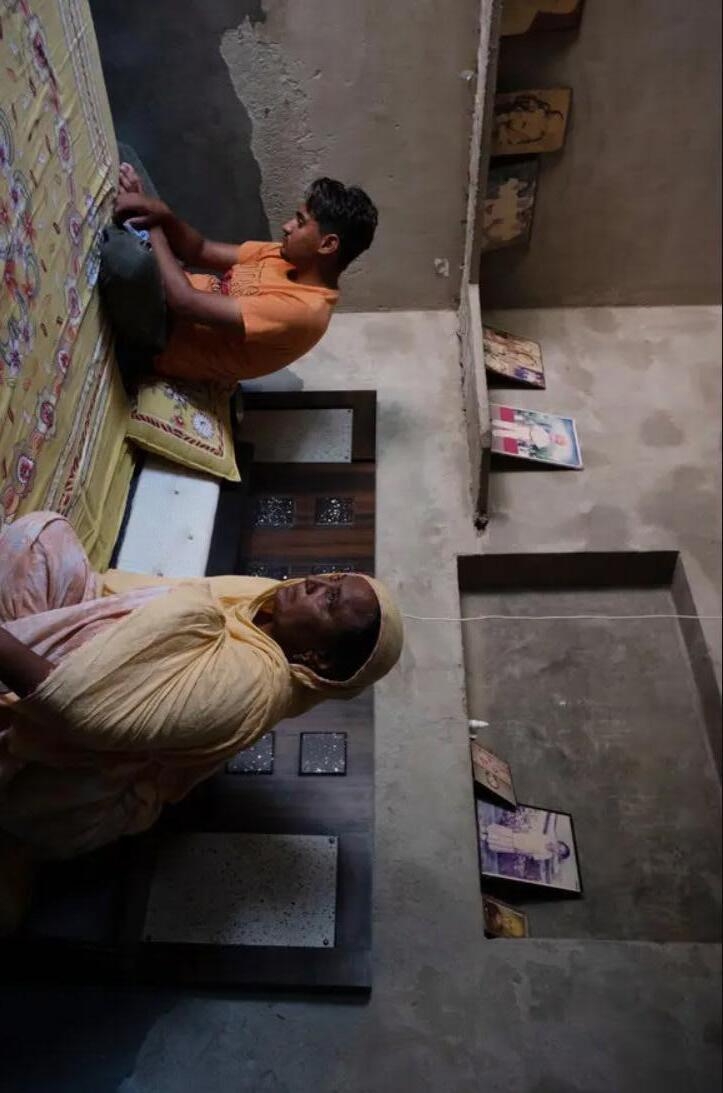

In the summer of 2023, I went back home to Hyderabad, India. I had this urge to work with an on-ground organization of some kind, directly or indirectly involved in climate change. I ended up working for a nonprofit through a mutual contact, who later became my Subject Matter Expert (SME). In the course of my involvement with the organization, I realized that the people involved with climate change are where we need to bring about change. Since the age of industrialization, we have seen that humans have been trying to come up with ways to remove humans from geo-engineering with the earth, which started as a petition to make earthly extractions more efficient, and now towards making the earth more sustainable or not harming it. The conversations I had and the readings I consumed were like a mirror - they showed me that my movement for seeking opportunity is a compulsion for many. This sparked a sense of responsibility in me to generate opportunities for them. Moreover, my cultural and ancestral background, with my grandparents being farmers or involved in farming-related business, further reinforced this commitment.

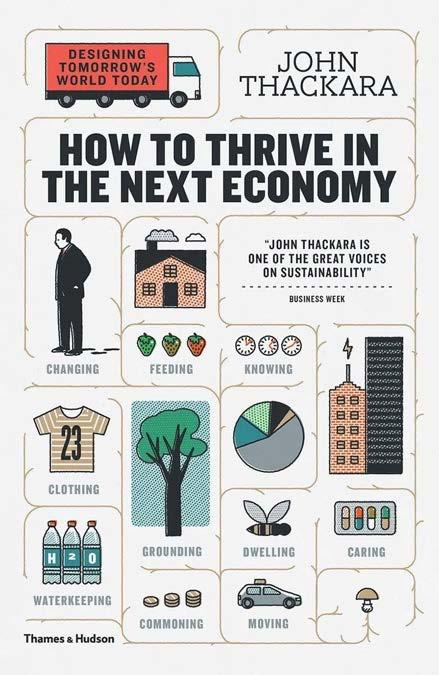

In the months leading up to my thesis, I immersed myself in understanding the motivation of climate-altered societies. I read up on the history of industrialization,

farming economy, disasters, the role of women in building societies, policy, and even anthropology.

I found three main themes that spoke to me and were areas of concern:

/ Over time, humanness was completely removed from how we treated people of low and middle-class communities - why aren’t relief measures and disaster preparedness given importance?

/ Children dwelling in climate-altered societies were carriers/hosts of transgenerational trauma.

/ We are on the precipice where we stand looking 20 years ahead into a generation of humans with no farmers.

Hence, the research began as a way to learn as much as I can from different subjects, attempting to understand as many perspectives on the above three topics as possible.

The exploratory research covered a variety of topologies in which climatealtered societies were spoken about, from education and futuring to neuroscience and psychology, through articles, books, publications, videos, and even movies. In addition to these, a large portion of the thesis involved conversations with experts who have worked with or on topics surrounding climate-altered societies - social entrepreneurship, museum curation studies, psychologists, photojournalists, urban planners, and many more - which has been crucial in shaping both my perspective and the thesis itself.

Since i came to the US there have been 226 significant climate events And, is it estimated that more than 110 million people have

been prone to some form of displacement. Additionally, at the end of 2022, 32.6 million internal displacements due to disasters were reported, with 8.7 million people remaining displaced.

Since the dawn of industrialization in the 18th century, humanity has been deeply intertwined with the earth’s resources, often exerting forceful extraction and displacing communities in its pursuit of progress. This historical trajectory has left an indelible mark on our planet. Today, we are working to repair the world we created, under the umbrella of sustainability. Today, as a consequence of our historical actions, we find ourselves at a crossroads where human activity no longer solely impacts humans, but also reverberates through the interconnected web of the climate itself.

Throughout history, humanity has been entrenched in the grim reality of warfare, a phenomenon that has shaped civilizations and altered the course of history since the advent of industrialization. Initially, the impacts of war were predominantly direct, manifesting as conflict among nations and devastation inflicted upon human populations. However, since the last 2 decades, we are seeing the profound indirect impact of the past industrialization’s damage on https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/education/lesson-plans/displaced-persons-aftermath-world-war-II

nature, wherein the indirect consequences of environmental degradation are increasingly influencing human societies on an unprecedented scale - beyond any man-made weaponry could. The aftermath of World War II marked a pivotal juncture, highlighting the stark contrast between the direct human toll of warfare and the burgeoning ecological crises spurred by industrial activities. In the ensuing decades, rapid industrialization and unchecked exploitation of natural resources have precipitated a cascade of environmental degradation, punctuated by phenomena such as climate change, biodiversity loss, and habitat destruction. We even saw the 2012 scare where we thought the world would end. The 2012 phenomenon, which gained widespread attention, was based on the belief that the world would end on December 21, 2012, as predicted by the Mayan calendar. However, this prediction was widely debunked by scientists and scholars. NASA scientists emphasized that there were no credible threats to the Earth in 2012 and that the claims of doomsday were not supported by any scientific evidence. The idea of the world ending in 2012 sparked a range of reactions, including heightened anxiety, survivalist and prepping activities, and a surge in creative exploration of apocalyptic narratives in literature, film, and art. We also saw that the movie had scenes related to class divide, affordability, and sustenance.

However, as the clock turned to midnight on December 21, 2012, no apocalyptic events occurred, and people around the world continued with their normal activities. With the ongoing crisis we stand at a precipice of mass migration which will not only determine the evolution of humans as a species but we see that it is now relating to the biodiversity of the earth itself. We need to take action today!

Today, mass migration, driven by social, environmental, and economic factors, poses significant challenges. Human evolution and Earth’s biodiversity are intertwined, necessitating immediate action.

“It is time to govern the world as if the Earth mattered.”

https://essaypro.com/blog/2012-end-of-the-world

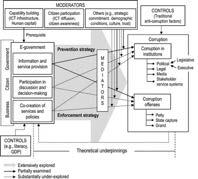

An article from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace served as a cornerstone of literature that guided the research documented in this book.

The scope and costs of this assault can no longer be ignored. They have been documented in a succession of stark reports from the United Nations and private groups like the World Wide Fund for Nature.11 On nearly all indicators, the trajectory is dismal. Global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions would need to drop 45 percent by 2030 to hold the rise in average global temperatures to 1.5°C, the objective to which nations agreed in Paris in 2015. Instead, they are on track to decline only 3 percent by the end of the decade, portending a future of searing heat, raging wildfires, acidifying oceans, violent storms, rising seas, and mass migration.12 In the latest Emissions Gap Report, issued shortly before the twenty-seventh Conference of Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP27), the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) admitted that there is “no credible pathway to 1.5°C in place.“ Indeed, current policies point to a world where temperatures rise 2.8°C, and national commitments (even if fulfilled) would only reduce this to 2.4 2.6°C.13 “We had our chance to make incremental changes, but that time is over,“ warns Inger Andersen, UNEP’s executive director. “Only a root-and-branch transformation of our economies and societies can save us from accelerating climate disaster.“14

Climate change, moreover, is just part of Earth’s environmental plight. Biological diversity is also imperiled, and global warming is not even the primary culprit.15 Around the world, ecosystems and species are at risk of collapsing as humans degrade and despoil landscapes and seascapes, dump pollutants and toxins into the environment, introduce invasive species, and harvest timber, fish, wildlife, and other living resources unsustainably.

The figures are sobering.16 Three-quarters of the planet’s ice-free terrestrial surfaces and two-thirds of its marine environment have already been severely altered, including by agriculture, ranching, logging, mining, urbanization, and industrial fishing.17 Ninety-three percent of global fisheries are overexploited or exploited to capacity, and fleets have reduced large ocean fish to 10 percent of their preindustrial numbers.18 Every year, the world discharges another 300 400 million tons of toxic sludge, heavy metals, and industrial poisons directly into the water, as well as 14.3 million tons of plastic into the oceans.19 Globally, fertilizer runoff has created more than 400 hypoxic (low oxygen) coastal “dead zones,“ with a combined area larger than that of the United Kingdom.20 One million animal and plant species face near-term extinction.21 Since 1970, populations of wild vertebrates have declined by 69 percent and insects by 45 percent worldwide, and 3 billion birds have vanished from North America.22 Humans and our domesticates now account for 96 percent of the planet’s mammalian biomass; 70 percent of all birds are poultry.23 Half of all tropical forests have been destroyed since 1960, and each year the world loses another 3.36 million hectares (8.3 million acres) an area the size of Belgium.24 Globally, more than 85 percent f wetlands and 35 percent of mangroves have already been lost.25

There have been five mass extinctions in Earth’s 4.5-billion-year history. Mounting evidence suggests we are on the cusp of a sixth.26 This risk is particularly acute in the world’s oceans, which are warmer than they have been in recorded history and 30 percent more acidic than they were just 200 years ago the fastest change in ocean chemistry in 50 million years.27 Half of all coral reefs have disappeared since 1990, and 90 percent of those that remain are likely to die by 2050 as average sea temperatures exceed those ever recorded.28 Acidic waters, meanwhile, threaten the survival of zooplankton and invertebrates and the collapse of entire food chains. Without swift and dramatic steps to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, two Princeton University scientists warned earlier this year, the loss of ocean biodiversity over the next three centuries could rival the Permian Ex-

tinction, which saw the disappearance of 90 percent of ocean life.29

Our own species is suffering, too, on this degraded and crowded planet. Hundreds of millions face food insecurity, and agricultural production must rise 50 percent by mid-century to meet growing demands.30 Freshwater resources are under similar strain as snow pack melts and aquifers are drained faster than they are replenished. By 2050, 40 percent of humanity could confront severe water stress.31

Human health is also at risk. Since 1970, some 200 pathogens have leapt from wild animals to people, often through intermediate hosts. They include among others HIV/AIDS, Ebola, SARS, Nipah, West Nile, MERS, H5N1, monkey pox, and of course SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19 and that came from horseshoe bats.32 While epidemiologists debate the pandemic’s proximate origins (natural transmission versus laboratory leak), they agree that we have entered a new era of infectious disease and that our unsustainable approach to nature is partly to blame.33 As humans and livestock encroach upon and disrupt biodiverse ecosystems, they encounter once-isolated species, exposing themselves to new viruses that can quickly spread globally.34 The average annual cost of emerging zoonoses is more than $1 trillion worldwide, with periodic pandemics capable of inflicting severe damage (in the case of COVID-19, as much as $28 trillion in lost global growth through 2025).35

Two and a half centuries after the much-maligned Thomas Malthus published his Essay on the Principle of Population, the good reverend merits another hearing, albeit with a twist.36 While Malthus may have erred in arguing that food production could never keep pace with human fecundity, overconsumption is definitely an ecological problem. According to the Global Footprint Network, it would take almost five Earths’ worth of resources for the world’s 8 billion inhabitants to achieve the same living standard average Americans enjoy today.37 And things are poised to get worse before they get better. Despite declining fertility, the human population will not plateau until at least 2060, and the aspirations of a rising global middle class will exacerbate ecological strains.38 Contrary to the beguiling claims of techno-utopians, there is scant evidence that societies get “more from less“ as they become wealthier.39 Rather, the newly prosperous tend to outsource their natural resource demands to developing countries.40

In seeking to satisfy these appetites, we risk breaching several planetary boundaries including those related to atmospheric CO2 concentrations, ocean acidification, species extinction, and nitrogen fixation that define what scientists call a “safe operating space for humanity.“41 Indeed, evidence is mounting that important subcomponents of the Earth system could be approaching critical thresholds that, when crossed, bring about massive, nonlinear shifts that will themselves accelerate climate change, with disastrous and potentially irreversible consequences for nature and humanity.42 Such potential discontinuities include a rapid die-back of the Amazon rainforest, abrupt melting of boreal permafrost, and the sudden collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, an oceanic conveyor belt that keeps Europe’s climate temperate.43

Short of an alien invasion from outer space, it is hard to imagine any threat warranting more global solidarity and collective action than the prospect of rendering the sole planet we have uninhabitable. Our circumstance cries out for a “present at the creation“ moment, akin to the flurry of international institution-building that followed World War II.

“Short of an alien invasion from outer space, it is hard to imagine any threat warranting more global solidarity and collective action than the prospect of rendering the sole planet we have uninhabitable.”

The Institute of Economics and Peace estimates that, by 2050 1.2 Billion people will be displaced around the world due to climate change and related disasters. If the global population reaches 9.9 billion by 2050, that means 12% of the world will be climate migrants, living on a planet with uninhabitable regional dry zones and increasing gentrification.

We must address climate change, preserve ecosystems, and promote sustainable development. By working together and prioritizing environmental stewardship, we can build a better future for humanity and the planet.

Now is the time for action.

Among the most vulnerable to these changes are agrarian communities - farmers, fishermen, loggers - whose livelihoods come from ancestral geo-engineering practice and have been intricately tied with nature for generations. For these communities, climate events are seasonal, and hence climate adversities are recurrent. If we draw a timeline it looks something like this

Due to the combination of repetition and unpredictability, it becomes challenging for governments to allocate resources effectively, both for infrastructure and healthcare, addressing both physical and mental health needs. Additionally, mental health issues often carry a significant stigma within these communities.

Therefore, it is not solely the result of human and infrastructural forces but also the gradual toll on individuals’ minds and bodies without respite that drives families to migrate away from their societies.

However, they do not migrate for or toward opportunity but out of necessity because their homes were destroyed, occupations disappeared, and wealth drowned. The increased occurrence and prominence of climate crises are generating both active and passive distress among humans. Since harvest is highly dependent on climate conditions,

climate change is intricately woven into not just the occupational but also the socioeconomic and personal state of these individuals, societies, and countries. In many cases, entire communities have vanished from their original landscapes as a consequence.

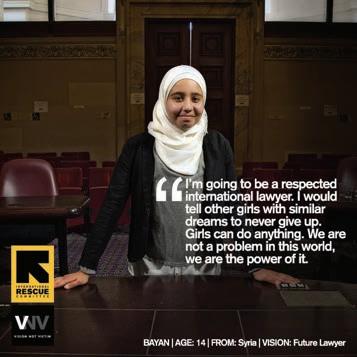

The connection between recurrent climate events, mental health, and children may seem loose to some; initially, it felt very loose to me as well. Until I read Rob Nixon’s Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Rob coined the term Slow violence to bring to attention the insidious, longterm harm inflicted by environmental degradation, socio-political injustices, and systemic inequalities that often go unnoticed or are overlooked in traditional notions of violence.

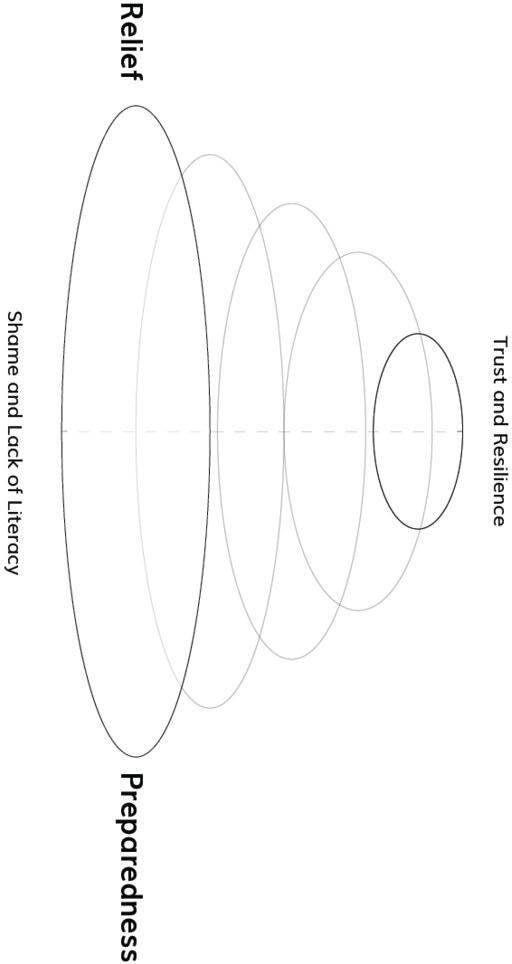

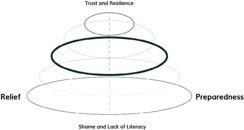

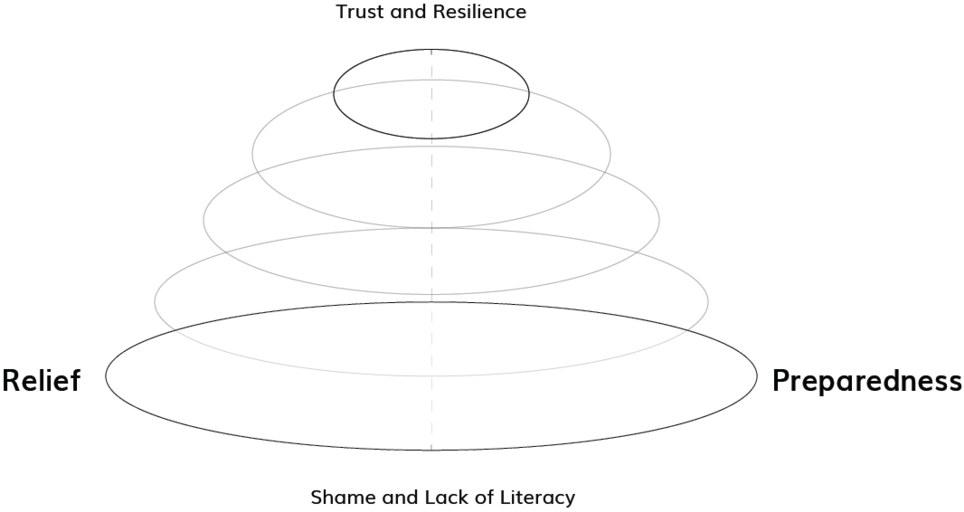

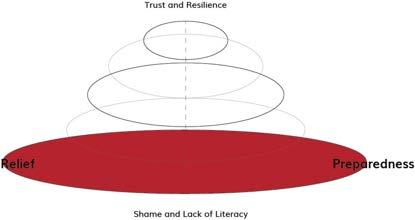

But to really understand where slow violence manifests itself, we need to also look at the preparedness and relief together.

The first 3-4 weeks of my thesis semester were dedicated to researching how agrarian communities prepare for recurrent climate events. To my surprise, there was heavy documentation on schemes, plans, and even bsiness models around what should be done, but not many instances where these schemes, plans, and business models were implemented. My first understanding was that there was not enough funding, or the idea could not be scaled, or there was exploitation involved. However, the issues were related to adoption, from language barriers to distrust in something working, to failed projects as they could not provide consistent relief.

However, I did see that relief was getting a lot more attention and support from both government and non-profit organizations. But here also there is a layer of distrust, because of political and economic reasons. There’s the initial period when a community is struck by climate events, followed by a subsequent phase dedicated to rebuilding, restoring, and returning to what experts in the field term the “pre-crisis state.”

Yet, for numerous communities in the Global South, climate events are intricately woven into the fabric of the harvest season. Consequently, their timeline takes a different shape, resembling more of a continuous cycle, where the period between each catastrophe, though not immediate, becomes a state of “before.”

When in conversation with Vijay Konda, Founder of Hope Foundation, Hyderabad, India, It became clear that we cannot see preparedness and relief as separate entities; there needs to be a bridge that connects these two and the bridge to reduce the distance, in order to accommodate the increased frequency of climate activity.

Konda Vijay Kumar, Chairman Hope Foundation, Telangana.

Vijay Konda is associated with the Hope Foundation, a non-profit organization based in Hyderabad that works to provide support and services to underprivileged communities. In a quoted statement, Vijay Konda shed light on the Hope Foundation’s approach when working with tribal communities, suggesting that he likely holds a position overseeing or coordinating the organization’s outreach efforts and engagement with these marginalized groups in the region. He emphasized that in many of the tribes they serve, the organization is not directly involved; instead, a volunteer from within the tribe becomes a mediator between the Hope Foundation and the community. The approach described by Vijay Konda underscores the organization’s emphasis on patience, cultural sensitivity, and a deep understanding of the unique challenges and dynamics within these marginalized communities. By fostering trust and working through local intermediaries,

the Hope Foundation aims to deliver its services and support effectively while respecting the cultural identities and autonomy of the communities they serve.

Q: Have you seen an increase in migration due to climate change?

A: We have seen more and more people wanting to move to gentrified areas as climate adversities increase.

In India, where every few miles people, cultures, languages, and communities change, impacts of climate change are more adverse, as communication becomes a problem. At Hope, we mostly service tribal communities who are often unaware of what is coming ahead as they are locked away from news and everyday communication and stick to their own societies. Now, due to all of this, when a flood or a storm hits, they are underprepared, and even if they are prepared, they are not prepared to face the adversity of today, as for them, their little world has not changed. So at Hope, we aim to educate and empower through knowledge and help these communities be prepared.

Q: What kinds of communities are most at stake?

A: Most definitely, communities who are directly linked to the climate are very much at stake. We service a range of communities, including loggers, forest tribes, fishermen, and more. We see that over the last few years, there has been a significant shift in their lifestyles, from the food they eat to the kind of shelters they live in. Before, when the climate wasn’t so adverse, the sustainable lifestyle they built or had for generations was able to serve them, but it is no longer serving

them. Rains are stronger, winters are colder, and summers are hotter, and their ancient practices, which helped them survive, were not aiding them anymore. Moreover, we see the pattern becoming more and more common in communities when joint families are becoming single-family nexuses.

Q: What does it take to build trust and foster relationships with these communities?

A: As you can imagine, tribal communities are not synonymous with other communities and don’t easily open up, so this makes extending help and facilities very difficult. The way we work is by letting one or two people from their community approach us and make ourselves visible. Through this, we build volunteership, and this volunteer becomes the representative of that tribe, who lets us know. And this isn’t some covert operation. In many cases, the volunteer is a known important public figure from this community, who seeks permission from the community or the elders of the community. We make friends with the local rural/tribal residents and choose one or two young boys and girls to know the situation in their area from time to time, and we will take nutritional supplements, medicines, educational materials, blankets, water filters/motors, and many more resources which will help the pregnant women, malnourished children, students, elderly people, and a few more tribal residents.

Q: How are you prepared to help these communities prepare?

A: Firstly, we always prepare 4-8 months in advance. We foresee certain issues that have been a pattern in the past and therefore stock up our inventory. Ever since COVID, we have made it a structured part

of our team’s work to follow the PRE approach: P - Planning, R - Resources, and E - Executability. With these three in mind, we coordinate.

Q: Is relief accepted without any resistance?

A: Absolutely not. As a team, we faced many challenges from police, village authorities, religious groups, forest officials, nature, and many more. People think differently, but we make sure we stand by our core values – no discrimination based on religion, region, caste, age, gender, social/financial status, color, height, weight, and education. As we are a little aggressive team for work and result-oriented, sometimes we are seen as local rebels. But once they see our work and get to know us deeply, people like to join us for future work. However, the communities see this rebelliousness as allyship, and in a way, it breaks the barrier. It’s not perfect, but it’s what it takes.

Q: What, according to you, will bridge the gap between being prepared and the relief that is required after, to help these communities stay and rebuild?

A: I see a gap in infrastructure definitely, but from my work, it’s also very bold. Being prepared today encompasses a range of things, from getting your environment prepared, then your home, but most importantly, one’s body and brain. The reason why moving is seen as a viable solution is that they don’t want to put themselves, and most of all their children, in the kind of bodily stress individuals are already facing. That’s why a logger today does not want his son to continue the heritage.

While active efforts are made to counteract the visible violence, employing technology and efficient ways to rebuild and restore swiftly, the emotional distress of these communities continues to accumulate.

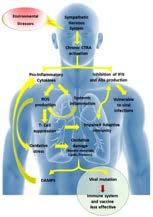

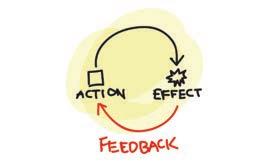

Slow violence builds anxiety and stress within the physical environment, and consistent exposure to stress creates a flight or fight response within the brain. Human experience is individual and impacted by a multitude of intersecting factors that affect the biological development; the brain, which is the mediator between the environment and biological processes, becomes disordered by trauma and maladapts, and it is unpredictable how an individual will manifest the maladaptation.

Neuroplastic changes have lasting effects on brain communication, functioning, and behavior. Being continuously exposed to stress puts the body in a flight of fight mode. During which the brain in a maladaptive method of self preservation triggers the cortico-limbic release of glutamatea chemical that greatly impacts behavior because of how it stimulates changes in neuroplasticity. Neuroplastic changes have lasting effects on brain communication, functioning, and behavior. Which is further translated to the body.

And the lack of support structures puts the brain into thinking that the individual cannot rely on anything, hence eroding the trust towards structures in one’s brain. Since that maladaptive network of not trusting is already formed - the maladaptive neurons which wire together will maladaptive fire together.

Stress is a physiological reaction that is part of the body’s innate programming to protect against external threats. When the brain anticipates danger, it triggers the stress response, releasing cortisol and activating the body’s sympathetic nervous system, which initiates the fight or flight response. This leads to the release of counter-response hormones as well, resulting in increased heart rate, accelerated breathing, dilation of blood vessels, and elevated blood sugar and glucose levels.

The immune system also responds to promote quick healing. However, for unremitting stress caused by slow violence, which accumulates over time, the regulation becomes inequitable and continuous.

The constant strain interlaces and accumulates in the body as it strives to return to “normal,” eventually wearing it down. Professor Arline T. Geronimus first coined the term “weathering” to describe this continuous “high-stress coping,” which is experienced as a universal human physiological process. Stress can fundamentally alter the body on a cellular level, as noted by Dr. Glenn Schiraldi.

But the weathering - Like the tree, the body remembers

Children are the most vulnerable in this state of slow crisis. Unlike adult brains, children’s brain anatomy is still developing and is naturally neuroplastic[]. Even a single instance of stress can create a larger number of maladaptive neural connections -leading to altered neural circuitry.

Moreover, prolonged exposure to stress hormones like cortisol can disrupt the development of neural connections, particularly in areas of the brain responsible for emotional regulation, cognitive function, and stress response. This dysregulation in the brain’s communication is a common indication of PTSD. Slow violence is so insidious that it can manifest in the womb, A washington post article, which I came across during my research explained how cortisol released into a the womb by the mothers body had changed the structure of placenta, as the cortisol is transmutable through the bloodstream. Once again - stress can change the body on a cellular level, changing the structure of the epigenetic markers. These changes are imprinted onto how the body - which is a large system of wires which communicate with each other - speak within and develop.

Stephanie Foo, in her memoir “What My Bones Know,” confronts the history of abuse in her ancestral line, which she had inherited.

“We are all products of our history... I don’t really think it’s surprising that we carry our fears, traumas, ties, and insecurities and pass them on to children to some degree,” she also added a personal anecdote, speaking of her greatgrandfather who had survived World War II. “I personally believe that because my great-grandmother and grandmother had to hustle desperately to survive, that has contributed to the hustle and creativity I’ve possessed in building my own career and survival skills... It’s probably contributed to my intense anxiety.

The kind of traumatic experiences faced by children are called Adverse childhood experiences.Furthermore, ACEs can also impact the architecture of the brain’s limbic system, which is involved in processing emotions and memories. This can lead to heightened emotional responses, including anxiety, depression, and hypervigilance.

Over time, these maladaptive neural connections can contribute to a range of negative outcomes, including mental health disorders, substance abuse, and physical health problems. Therefore, addressing ACEs and providing support and intervention early in life is crucial for mitigating the long-term impact on neural development and promoting resilience in affected individuals.

Gayathri Thakoor, Social Entrepreneur and Co-Founder LeTS India.

postgraduate degrees in Education (IGNOU) and Finance (Mumbai University), and a Bachelor’s degree in Economics.

Q. How do you think climate adversities affect children today? How does it affect them psychologically?

Gayathri Thakoor is a social entrepreneur who co-founded the Learn Through Stories (LeTS) Foundation, a not-for-profit initiative aimed at disseminating the Learn English Through Stories framework developed at IIT Bombay. With a background in academia, industry, and media, she has expertise in bridging gaps between these sectors. Previously, she contributed to the development of the Learn English Through Stories model at IIT Bombay’s Tata Centre for Technology and Design. Thakoor has managed multiple research projects, fostered collaborations, and served as a liaison between institutions, agencies, and partners. She is also a published author and co-founded ‘Nanogems’ to create children’s literature and copyrighted animated characters. Early in her career, she worked as a journalist covering diverse beats like business, crime, education, and politics for The Times Group. Thakoor holds

As someone deeply involved in children’s education and well-being, I am increasingly concerned about the profound impact that climate adversities are having on the younger generation. The effects of climate change, such as extreme weather events, rising temperatures, and environmental degradation, are not just physical threats but also have farreaching psychological consequences for children. From an early age, children are becoming acutely aware of the dire state of our planet, whether through personal experiences of natural disasters, education about environmental issues, or the constant barrage of news and media coverage. This awareness can lead to a sense of eco-anxiety, a deep-rooted fear and worry about the future of our planet and their own well-being. Children may experience feelings of helplessness, anger, sadness, and even depression as they grapple with the enormity of the climate crisis.

However, the real issue is that children are developing this anxiety from two sources: parents and social media/ communication. When my child was 6-8 years old, we experienced a flood, but I did not worry about her well-being because I trusted her resilience and my ability to keep her safe. Nowadays, due to these two factors, we see a stark difference in how parents communicate with children. The minute a parent sees a weather forecast, children are made to stay home,

alarm calls go out, and naturally, children, with their flexible brains, store these as voluntary responses to such news.

Q. Is education a route that can be pursued for this? Why is storytelling an effective tool for education? And why is LeTS rooted in storytelling?

A. No matter how much education we provide and try to build emotional resilience through information, there will be a gap, mainly because education is just a part of their day. We need interventions that can instigate them to communicate, think, and visualize differently the situation they are in. Where education can really help them is to express and reinforce the learning, because learning is never individual; it occurs in groups.

Educating a community or class is far more effective when the learners can relate to what is being taught. Many subjects and concepts are lost or tend to be feared for years when there is no context or relevance shown.

A teacher is revered as a good educator when they deliver the concepts in ways that can relate to the learners, so they make it their own. Experience tells us that a lot can be achieved through storytelling. A professor in food science I know once said, “A good teacher is one who can tell the most wonderful stories.” That the concepts can be woven into stories and then delivered to the captivating learners, for them to absorb, contextualize, internalize, and always remember, is what makes teaching and learning even more impactful.

Another critical aspect of our process is that as learners gather the means to generate their own content – and, especially, as they put it together – their own lived worlds and realities become part of the learning material, from language to geography, science to story. They write themselves in.

The development of children is influenced not only by internal factors but also by the responses of adults, which play a crucial role in shaping their growth. When in conversation with Gayathri Thakoor, Social Entrepreneur and co-founder of Learn Through Stories (LeTS) Foundation, India, she spoke about how parents of the 2000s are extremely concerned about their children when they are not at home. She shares a personal anecdote, stating that over the last 10 years, childcare has shifted from allowing children to learn and grow through making mistakes and facing challenges to a focus on protection, supervision, and constant monitoring.

“As a parent, when my daughter was in elementary school, I never panicked about her well-being to the extent of needing to make alarm calls or inquire about her minute-to-minute status. Even during floods, we trusted that our child would return home safely. We were concerned, yes, but not like parents today who, upon hearing a hurricane warning, immediately call to check up on their kids,” she added.

She also noted how technology has made it very easy to make alarm calls, and while parents may believe they are safeguarding their children, the children perceive these calls as signals of danger. This erosion of trust between parents and children is concerning.

While technology has its perks and solutions, it also has created a web of lacking trust within individuals, which has to be addressed.

During this conversation, there were three large themes - Trust between parents, children, and their environment is deficient, influencing children’s learning of crucial responses, reactions, and information processing primarily through parental influence.

Cynthia E. Smith, Curator of Socially Responsible Design Cooper Hewitt

Smithsonian Institution

Cynthia E. Smith is the Curator of Socially Responsible Design at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. In her role, she organizes exhibitions, publications, and public programs exploring the evolving field of design aimed at addressing global social issues. Smith’s curatorial work has focused on showcasing how designers, architects, engineers, and non-profits collaborate with communities to co-create solutions that improve lives and alleviate poverty. Her notable exhibitions include “Design for the Other 90%,” which highlighted designs for underserved populations, and “Design with the Other 90%: CITIES,” examining informal urban settlements. Smith’s curatorial vision extends beyond developing economies, exploring the intersection of poverty, prosperity, and design innovation within and beyond the United States as well.

Q: As the curator of Socially Responsible Design, how do you evaluate whether a project fits within the theme, especially a theme like designing for peace?

A: I would say that it starts with developing a thesis. That’s the first thing I do - put together a thesis to organize the initial research, talking to people, and gathering information, not unlike what you’re doing. So you have this guiding statement, and then you go out and conduct extensive research. I cast a wide net, trying to talk to as many people as possible, and they lead me to more projects and work. Then I begin to sort through what I’ve gathered because I’m looking at current happenings or concepts that people are envisioning. Often, themes start to emerge. I don’t go out looking for specific themes initially. I just have a broader question or proposition. And then, as I begin to analyze the research, the themes sort themselves out. I bring it to other people to see if it makes sense because I’m always thinking about who my audience is. Depending on the work, I have different narratives and scales because I only have a limited exhibition space. So I tell stories using different media, depending on what’s available based on the work of that particular designer, artist, or collaborator. It has to be legible and make sense.

This is the dilemma we’re living in right now. This is what we’re thinking about in the degrowth movement, when you consider degrowth, we’re at a point where the planet’s future is at stake. When you talk about your kids’ future, are you thinking about profit? Probably not. We’re likely talking about social entrepreneurship because it depends on who the population is and who’s working

in that arena.

You have to look at the different sectors - public, private, and civil. So you really need to think about whether it’s a municipality or part of what a government will deliver at the local level. Or is it a neighborhood group? A non-governmental organization (NGO)? A combined effort? An agency? It depends on the country, its economy, and whether you’re an international upstart wanting to crowdsource and create something.

We have the ability to stop this warming if we choose to do so. I want to introduce you to someone because I think you’ll have a fabulous conversation with them, and they’ll point you to things I could never, as this is directly what they’re looking at. It’s an initiative called “Root Shock 2.0.”

Q: From the work you’ve done and the artists you’ve seen and collaborated with, what do you think the planet will look like? It was definitely different from when you were young.

A: There is definitely a difference, and that difference calls for action, which is what you’re looking at in relation to what’s happening. We’re on the brink of it exploding all over the place with the advent of a warming planet. If we don’t achieve zero emissions, we’ll be unable to inhabit large portions of the Earth, leading to mass migration.

The original “Root Shock” influenced an entire generation of city designers and urban designers. It was a really important book. The other thing I want you to look at is the IPCC, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. There are some graphs you might want to include in your thesis, which really show what the planet is going to look like for people born when I was born, people born 20 years later, and people of your age and later, if we don’t do something now. It will lend credence to your argument.

In children of low and middle income agrarian households, we see an increased tolerance towards climate events, but the vulnerability is compensated when handling issues of slow violence brought on by the climate event - alcoholism in parents, parental absence, strict/stern parenting, emotional and physical abuse, and in some extreme cases death of a parent through suicide.

Following such events, the brain looks for physiological ways to express what cannot be tolerated to articulate making somatic symptoms and conversion disorders common byproducts of PTSD .

Trauma impacts the brain’s neurobiological responses or otherwise manufacturing processes- how it communicates with the rest of the body Traumatic events are held by the brain with more complexity and enmeshment than benign or even positive ones (Corrigan & Grand, 2013) [12]. Dissociation first presents during traumatic events and is the first association of how that memory becomes held. It is the foremost coping skill the brain develops- it exacerbates other symptoms and creates great complexity in the treatment process. Colloquially known as shock, dissociation is a prolonged state of being during which one feels detached from their emotional state and physical self, a maladaptive attempt at self-preservation.

Trust is the generalized expectation that they themselves or another individual can be consistently relied upon, without any harmful repercussions.

the feeling/ emotion attached to being in a reliant space or with a reliant person.

One of the primary challenges faced by low-income societies living in climatealtered environments is the unpredictability of relief efforts. Despite the increasing frequency of climate-related disasters, the response remains inconsistent and often delayed, leaving residents grappling with uncertainty about when or if help will arrive. This lack of reliability erodes trust in relief structures, leaving communities feeling abandoned and neglected. Furthermore, even when aid does reach affected areas, the accountability of relief efforts comes into question. Reports of mismanagement, corruption, and misallocation of resources are not uncommon, exacerbating the distrust towards relief organizations and government agencies. Without transparency and accountability, vulnerable communities are left susceptible to exploitation and further marginalization.

Mallela Prashanti, Indian Administrative Services Officer, for the Telangana state.

Mallela Prashanti, graduated in Economics from Osmania University, Hyderabad, India. She holds a PG degree in Political Science and M Phil in International Relations from the University of Hyderabad, India. She was selected in the Indian Administrative Service and is currently working as an Additional Secretary in the Department of Environment Forest, Science & Technology in the Government of Telangana. She also holds additional charge of the post of Director in the Department of Health, Medical & Family Welfare looking after the division of traditional medicines like Ayurveda, Homeopathy & Naturopathy.

She previously worked as a District Magistrate of a district primarily consisting of a rural population occupied in agricultural operations. She took the initiative to develop an App designed to enable small farmers in rural and remote areas to access Agricultural machinery on the uber model. This project went on to win a National award.

As Director of the Department of Women & Child Welfare, she successfully conducted skill development programs for rural women, many of whom were successfully placed in the market.

Q. In your term have you seen migration and what have your and the government done to support the movement or help them rebuild?

A. As someone who has been closely involved with initiatives in Telangana, I can speak to the efforts made by the state government to support communities affected by diminishing natural resources. Despite having a rich heritage in cattle, textiles, and art, natural resources have become increasingly scarce over the years. This has led to tribal communities, villagers, and artisans migrating to towns and cities, causing them to abandon their traditional practices. Early on, we recognized the need to subsidize these artisans, farmers, and tribals to help them earn a decent living from their crafts. When they move to cities, they often face financial exploitation,

social marginalization, and in the case of women and young girls, even sexual exploitation. To combat these issues, we initially focused on forestry and tourism initiatives. In recent years, the emphasis has shifted towards water, energy, and infrastructure development, including housing, ensuring access to clean water, and providing produce and fertilizers for farmers and fishermen, primarily through loan programs. Moreover, to empower women in this process and reduce violence against them, a significant portion of land and loans are subsidized for women, making them the primary decision-makers. As a government, our approach is to keep people rooted in their communities and build infrastructure to support their livelihoods there. The more migration occurs, the more the state’s overall well-being diminishes, a factor that many states fail to consider. Unlike highly industrialized states that may seem to profit from migration, even their gains become difficult to sustain. When societies dwell in a place, they promote water conservation, greenery, and the preservation of natural habitats, as humans have historically been accelerators of environmental stewardship. It was not until the rise of the fossil fuel industry that this balance was disrupted.

However, lacking the means or, in some cases, the cultural inclination towards institutional education, they encourage their children to enter the labor market and earn money instead. This situation is absolutely atrocious, but it is the reality we are grappling with. There was a case involving girls from Orissa, rural tribals who had migrated almost 50 miles away. We found them at a construction site on the border of Telangana, being exploited to the point of earning a mere 10 rupees (0.12 dollars) per day.

Q. What are some issues the government has seen rise in the last few years due to migration?

A. A significant issue we face with migrant communities is the violence and exploitation of children. While I do not want to attribute it solely to climate adversities, the challenges arising from such adversities play a role. Parents in these communities often desire a different future for their children than the one they have experienced.

We intervened, providing these children with counseling, medical assistance, and facilitated their return to their original villages, offering incentives for education and monetary benefits. However, two seasons later, they were back in the same exploitative labor market. This is where, as a government, our services alone are not enough. That is why we provide funding for non-profits, self-help groups, and various committees whose mission is more localized and impactful, as they belong to those very communities. Their grassroots approach is crucial in addressing these deep-rooted issues effectively.

M. Prashanti, IAS, the Joint Collector, Hyderabad District formerly the Director and State Commissioner for the Welfare of Disabled and Senior Citizens, Govt. of Telangana and Joint Secretary to the Govt. of Telangana State, who has served as the former collector of Nirmal district, in the state of Telangana speaks to how in the state of Telangana, drought relief efforts have shifted focus towards supporting small communities and societies through policies and schemes. Despite these measures, the toll on mental health within these communities cannot be overstated. The constant threat of disaster, coupled with uncertainty and distrust towards relief efforts, creates a pervasive sense of anxiety and despair.

Moreover, generational injustice has led to a history of mistrust towards outsiders. Therefore, the government has been providing support to locals, often through trusted individuals, to act as beacons of change within their communities. However, communication barriers hinder government initiatives in reaching small societies.

Addressing the trust deficit in relief structures requires a multi-faceted approach that prioritizes transparency, accountability, and community engagement. Relief organizations and government agencies must work collaboratively with local communities to develop solutions responsive to their needs and concerns, establishing clear communication channels and ensuring equitable resource distribution.

Efforts to build resilience within these communities must extend beyond physical infrastructure to encompass mental health support and psychosocial services. Providing resources for coping mechanisms, trauma counseling, and community-building initiatives can help alleviate the psychological burden of living in a climate-altered world.

It becomes evident that climate-induced slow violence affects not only the mental and physical state of a child but also familial, social, cultural, and possibly even genetic aspects. This realization drew parallels with my senior Erika Choe’s thesis.

A portion of mythesis took inspiration from my Senior’ Erika Choe’s Thesis, which focused on the preserving humanness in the world shifting towards cohabitating with technology. While her thesis is wholly dedicated to exploring how humans currently interact and will interact with technology, mine also delves into how technology can intervene to a certain extent, with her thesis serving as a guiding beacon.

But, a major theme that emerged for me as a reader of her thesis was the concept of trust. If we can first instill trust in individuals living in potential climatealtered societies towards themselves, we can begin a larger project aimed at restoring both humanness and trust within societies, whether that be through social media, digital experiences, government initiatives, or healthcare.

If we project this onto the preparedness healing helix, we will see that if trust is not built the curve will expand and if trust is built then the curve’s radius will become smaller. Towards the preparedness end we need to build resilience within individuals , therefore instilling trust in themselves, whereas on the other end - relief - design should aim to provide structure for developing dependability.

During the course of the thesis, I was constantly told to narrow my focus on users and target audience, as if this issue were a global one. Even while sitting in New York City, surrounded by technology, I couldn’t solve it. My mentors and advisors often urged me to narrow the topic as much as possible. Moreover, even on a global scale, the problem’s characteristics and reasons for its existence change every few kilometers due to the topology of the Earth, and so do what children experience. It was already September, and I reached a point in my thesis where I had to make a decision about what my thesis was addressing - policies, injustice, healthcare, or a combination of these?

Almost 2 months into headfast research in September, we had a guest speaker at PoD, Panthea Lee. Panthea Lee is a writer, activist, and transdisciplinary strategist / designer / facilitator working for structural justice and collective liberation. So far in my thesis, I hadn’t spoken to someone from the field of structural activism, because I did not think my answers lay in that space. But how wrong was I? During Panthea’s lecture, I was introduced to the possibilities and prospects of healing, what it is, how it differs from religion and activism, and the potential modalities in which we can provide healing.

Healing in the context of my thesis adapts its original definition of the process of becoming or making somebody/something healthy again; - it is the systematic process of realizing, restoring, and reinventing physical health, mental health, individual connections to themselves, group, society, or environment, that has been affected by physical, emotional, mental, or spiritual distress or harm. And its success in adoption lies in the versatility of modalities it can come in.

During her lecture, she discussed the significance of healing in a GDP-driven era, where people’s value is often assessed solely based on economic criteria, such as a country’s resource allocation capabilities.

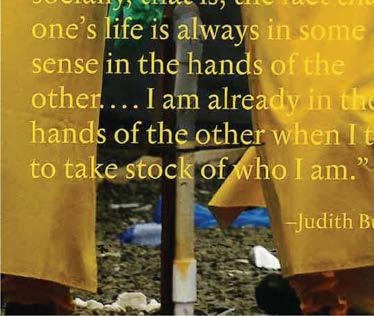

Her words took me back to a part of Rob Nixon’s Slow violence and the Environmentalism for the poor -

“In the global resource wars, the environmentalism of the poor is frequently triggered when an official landscape is forcibly imposed on a vernacular one. A vernacular landscape is shaped by the affective, historically textured maps that communities have devised over generations, maps replete with names and routes, maps alive to significant ecological and surface geological features. A vernacular landscape, although neither monolithic nor undisputed, is integral to the socio-environmental dynamics of the community rather than being wholly externalized—treated as ‘out there,’ as a separate nonrenewable resource. By contrast, an official landscape—whether governmental, NGO, corporate, or some combination of those—is typically oblivious to such earlier maps; instead, it writes the land in a bureaucratic, externalizing, and extraction-driven manner that is often pitilessly instrumental. Lawrence Summers’ scheme to export rich-nation garbage and toxicity to Africa, for example, stands as a grandiose (though hardly exceptional) instance of a highly rationalized official landscape that, whether in terms of elite capture of resources or toxic disposal, has often been projected onto ecosystems inhabited by those whom Annu Jalais, in an Indian context, calls ‘dispensable citizens.’”

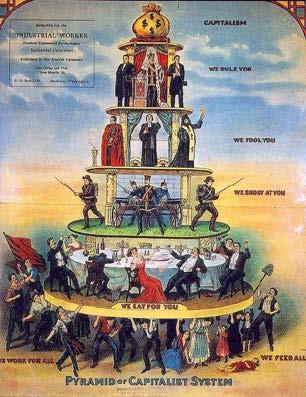

Following World War II, there was a proliferation of indices and acronyms aimed at quantifying the worth of individuals and populations, including the happiness index and GHDpe, contributing to the emergence of what she termed as a “third wave” characterized by the perception of individuals as expendable or disposable.

The wave of treating people as commodities initiated the process of commoditization and began to erode humanity from the ecosystem of human connection. Over the last seven decades, this epidemic has permeated various aspects of life, including healthcare, schooling, religion, and even childbirth. commoditization has emerged as a potent force shaping the dynamics of wealth, power, and societal stratification. Defined as the transformation of goods, services, ideas, or even people into commodities to be bought and sold in the marketplace, commoditization has permeated nearly every aspect of human existence. However, its insidious effects extend far beyond the realm of economics, seeping into the very fabric of social relationships and exacerbating systemic injustices.

At its core, commoditization reduces individuals to mere economic units, valued primarily for their utility in generating profit. This reductionism strips away the intrinsic worth and dignity of human beings, relegating them to the status of interchangeable cogs in the machinery of capitalism. As a consequence, socialeconomic injustice thrives, perpetuating disparities in wealth, opportunity, and access to resources. The commoditization of labor, for instance, leads to exploitative working conditions, stagnant wages, and precarious employment, disproportionately affecting marginalized communities already grappling with historical oppression.

Moreover, commoditization serves as a catalyst for the proliferation of classism, erecting barriers that perpetuate social stratification and entrench privilege. In a commoditized society, one’s worth is often measured by their ability to consume and accumulate material possessions, reinforcing notions of status and prestige tied to economic wealth. As a result, those at the lower rungs of the socioeconomic such as low income agrarian households and workers find themselves marginalized and disenfranchised, locked in a cycle of poverty and exclusion.

The consequences of commoditization extend beyond material inequalities, permeating the very fabric of social cohesion and communal harmony. As trust erodes within the system, fueled by perceptions of exploitation, injustice, and inequality, the bonds that bind communities together begin to fray. The lack of trust breeds suspicion, resentment, and alienation, undermining the collective solidarity necessary for a thriving society. In the absence of trust, cooperation gives way to competition, empathy yields to indifference, and the common good is sacrificed at the altar of self-interest.

Panthea’s lecture was invigorating as it resonated with many of the concepts I had been exploring in my initial research. She briefly delved into the concept of UBUNTU, which underscores the interconnectedness of humanity and the significance of communal harmony. At its essence, Ubuntu highlights the idea that individuals are shaped by their relationships with others, and that one’s humanity is deeply intertwined with the collective well-being of the community. This philosophy advocates for empathy, compassion, and mutual respect, urging individuals to acknowledge the humanity in others and to extend dignity and kindness in their interactions.

Ubuntu emphasizes the inherent value of relationships and the idea that “I am because we are.”

It embodies a belief that individuals are fundamentally connected to one another, and their well-being is intricately tied to the well-being of the community as a whole.

In the context of commoditization and socioeconomic injustice, Ubuntu serves as a poignant reminder of our shared humanity and the importance of fostering solidarity and mutual support within society. As commoditization reduces individuals to mere economic units and fosters a culture of competition and exploitation, Ubuntu calls for a shift in perspective towards collective wellbeing and cooperation. It highlights the need to recognize the dignity and worth of every individual beyond their economic value, thus challenging the dehumanizing effects of classism and social injustice.

Today “We are witnessing layer and layer so trauma, historical, generation, ancestral and soul deep”

Panthea’s discourse on stewarding love and liberation as a modality of activism to foster healing inspired me to explore what lies behind a successful mode of healing. At the core of this journey lie the fundamental principles of Ubuntu. However, the question arises: how can we advocate for systemic healing in a world driven by structural and economic agendas, where the concept of healing often feels marginalized and trivialized?

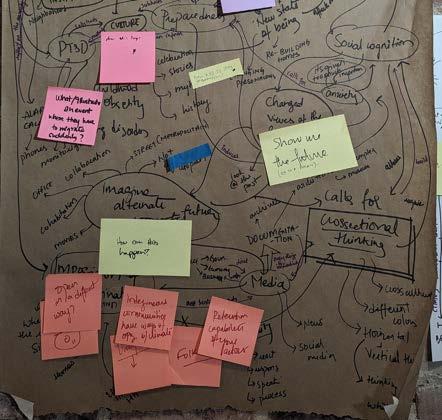

In contemplating the essence of healing, it becomes evident that its essence lies in cultivating resilience, a term more commonly embraced and applied within systemic frameworks. To understand this better, I conducted a concreation workshop with young adults and adults in their early 20’s. The agenda of the co creation was to have young adults envision their younger selves, in self exploration and envision what traits of resilience, they would foster in them.

In co-creation workshop, we embarked on a journey to understand the multifaceted concept of resilience. Initially, our focus was on exploring the diverse definitions of resilience, both from individual perspectives and from a broader societal viewpoint.

For the first half of the workshop we explored the various definitions of resilience both individually and what definition the world has -

“is the ability to cope mentally and emotionally with a crisis, or to return to pre-crisis status quickly.”

“I dont think you can ever go back to a pre crisis state“

terms of attention, anticipation, encouragement, intention, and risk-taking and management both before and after an adversity they may face. Moreover, it will also aid the individual in assessing and navigating their path back to a state of “normality.”

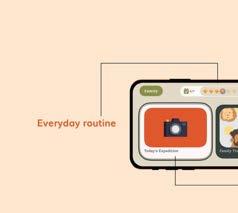

Normality is characterized by a consistent ability to navigate through daily routines without experiencing significant fluctuations in mood or motivation. It’s a blend of cultural norms and personal discipline, suggesting that resilience necessitates a routine that aligns with an individual’s cultural background.

However, how does normality differ from the pre-crisis state? When individuals encounter adverse or traumatic experiences, their brain undergoes changes as old neural networks disintegrate and new ones form, leading to changes in how the brain perceives, processes, and stores information. Even if the individual remains in familiar surroundings and receives similar information, the brain no longer interprets it in the same way. These changes often lead to the triggering of traumatic memories associated with certain stimuli, which were previously understood

Normality during the course of my thesis, has been defined as the way to continue the same routine while accommodating cultural nuances. A balanced integration of these factors can contribute to resilience.

During the co-creation I met Akanksha Kedhkar, who is Clinical Psychologist. We got into the discussion of what are the key playbooks in building resilience.

She pointed out that in psychology, Activities of daily living or Instrumental activities of daily living are a way in which we can assess an individual’s functional status and ability to live independently. The activities of daily living (ADLs) encompass fundamental tasks necessary for independent living, such as personal hygiene, dressing, eating, maintaining continence, and transferring/mobility.

`

5

Akanksha Khedkar is an experienced clinical psychologist with a proven track record of providing comprehensive support in both hospital and educational settings. She has demonstrated expertise in delivering effective therapeutic interventions and fostering mental well-being for her clients. Currently, Akanksha is advancing her expertise by pursuing a Master’s degree in Industrial/Organizational Psychology. With this specialized training, she aims to blend her clinical expertise with an understanding of organizational dynamics, positioning herself to offer valuable insights at the intersection of psychology and the workplace. Akanksha’s background in clinical and counseling psychology, spanning five years of work experience, has equipped her with strong skills in human relations, team building, and effective communication. Her unique combination of clinical knowledge and a growing understanding of organizational psychology makes her a valuable asset for organizations seeking to

promote a positive and productive work environment.

Q. Why are routines important?

A. I cannot overstate the importance of routines for children’s development and well-being. Routines provide a sense of structure, predictability, and security, which are crucial for a child’s emotional and cognitive growth. When children know what to expect and when, they feel a sense of control and safety in their environment, reducing anxiety and promoting a sense of calm. Routines also help children develop self-regulation skills, as they learn to anticipate and prepare for transitions between activities. This ability to regulate their emotions and behaviors is essential for their social and academic success. Furthermore, routines foster a sense of responsibility and independence, as children learn to complete tasks and follow a schedule without constant reminders.

Q. Are Routines and ADL’s the same?

A. No, routines and ADLs are related but distinct concepts when it comes to child development. As a psychologist, I view ADLs as the specific self-care tasks that children need to learn and master, while routines provide the structured framework for practicing those skills.ADLs refer to the basic activities like dressing, grooming, feeding oneself, using the toilet, and basic hygiene tasks. These are the building blocks of independence that all children must acquire through patient repetition and support from caregivers. Mastering ADLs allows children to take care of their own basic needs. Routines, on the other hand, are the predictable sequences and schedules that families use to organize a child’s day and times for

certain activities. Having consistent routines creates the opportunities to practice ADL skills at developmentally-appropriate times. For example, a morning routine may involve the ADLs of using the toilet, brushing teeth, getting dressed, and eating breakfast in a structured way.

So while ADLs are the specific self-care skills, routines provide the reliable contexts and prompts for children to work on those skills. The routines support ADL learning by breaking down when and how those tasks get accomplished. Without routines, the practice of ADLs can become haphazard. But routines alone don’t necessarily teach the step-by-step process of each ADL.

Q. Are ADLs important for becoming resilient?

A. Absolutely, engaging in Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) is vital for children’s resilience development. ADLs are the basic tasks that children need to perform daily to take care of themselves, such as dressing, grooming, and feeding themselves. When children can successfully complete these tasks, it builds their confidence, selfesteem, and sense of competence. As a psychologist, I understand that resilience is the ability to bounce back from adversity and cope with challenges. By mastering ADLs, children develop a sense of accomplishment and self-efficacy, which are key components of resilience. Each time they overcome a challenge, such as learning to tie their shoelaces or brushing their teeth independently, they build resilience muscles that will serve them well in the face of future difficulties.

Moreover, ADLs often involve problemsolving skills, as children must figure out how to complete tasks and overcome obstacles. This process of trial and error

fosters perseverance, adaptability, and creative thinking – all essential qualities for resilience. It’s important to note that children’s ability to perform ADLs can also serve as an indicator of their overall development and well-being. If a child struggles with ADLs, it may signal underlying issues that need to be addressed, allowing for early intervention and support. By encouraging and supporting children in mastering ADLs, we not only promote their independence and self-care skills but also nurture their resilience, equipping them with the tools to navigate life’s challenges with confidence and strength.

Q. How do trust and shame work when viewed from the perspective of climate anxiety in children?

A. As a psychologist, I’ve witnessed how the existential threat of climate change deeply impacts children’s sense of trust and shame. Climate anxiety stems from feeling betrayed by the adults and systems meant to protect them, eroding their foundational trust in a safe world. Children internalize the idea that “the planet is dying due to human actions, and I am human, therefore part of the problem,” breeding profound shame tied to their self-worth and identity. Their malleable brains seek this association as an absolute truth. Grappling with these heavy emotions of mistrust and toxic shame, children need reassurance, validation, and a restored sense of agency. Dismissing their climate anxiety reinforces the original mistrust igniting the shame cycle. By listening, validating their perspective, and channeling it into positive action, we can help children rebuild trust, release unproductive shame, and find their voice as environmental stewards.

ADLs alone are not sufficient to build self-confidence. While activities of daily living (ADLs) are crucial for maintaining independence and well-being, they are not directly correlated with the development of self-confidence. Selfconfidence is more closely linked to one’s beliefs, attitudes, and perceptions of their abilities and worth. Engaging in confidence-building exercises, focusing on strengths, setting and achieving goals, and practicing selfcare are some of the methods for building self-confidence. ADLs provide structure in one’s daily activities, which allows time and the ability to engage in self-improvement activities.

On the other hand, culture plays a dignified role in self-confidence, in the growing ages, the interaction and interfacing with cultural activities and exposure to literature, art, music and activities rooted in culture provide a sense of identity and commonness to people, spaces, and objects. Especially in children, when they participate in family events at home and outside in their culture, they will have more self confidence - CNRS (Délégation Paris Michel-Ange).

When we combine ADLs and self-confidence-building activities, we can begin to introduce children to trust-building activities within their environmentinvolving objects, people, and placing themselves in that environment.

Routines and activities of daily living (ADLs) are related but not identical. ADLs pertain to the fundamental tasks necessary for independent living, such as personal hygiene, dressing, eating, and mobility. Conversely, routines encompass a broader set of activities that an individual regularly performs, which may include ADLs but also extend to other daily habits and tasks. While ADLs primarily focus on essential self-confidence-building activities, routines involve a wider range of behaviors and actions that an individual engages in regularly.

Therefore, while ADLs represent a specific subset of activities, routines are more comprehensive and can incorporate various daily practices and habits. Moreover, routines are ingrained in the body, so the flexibility of adapting to an environment can be fostered by building trust from within - inward outrather than relying solely on changing the environment.

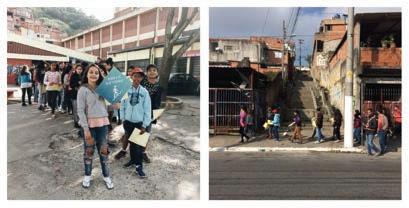

proposing routines as a systemic structure to foster resilience in children impacted by the effects of climate-induced slow violence, particularly those living in low and middle-income agrarian communities.

Where can we introduce routines for children?

But when we draw a systemic map around the ecosystem surrounding a child, it looks something like this. The ecosystem can be split into three distinct sections: the self, immediate environment, and social structures.

27% of the earth population is Children 12.7% are experincing extreme poverty

When designing for children, we need to ensure that there is an entry from the outer circles as the self is protected by them. However, there are some considerations and constraints to keep in mind, such as parental control, how children interact with it, and cultural sensitivity. While these factors enforce safety and structure, it is also important to foster freedom to make mistakes for natural growth patterns to form.

“The act of making that designers find so satisfying is built into early childhood education, but as they grow, many children lose opportunities to create their own environment, bounded by a text-centric view of education and concerns for safety. Despite adults’ desire to create a safer, softer child-centric world, something got lost in translation. Jane Jacobs said, of the child in the designed-for-childhood environment: “Their homes and playgrounds, so orderly looking, so buffered from the muddled, messy intrusions of the great world, may accidentally be ideally planned for children to concentrate on television, but for too little else their hungry brains require.”9 Our built environment is making kids less healthy, less independent, and less imaginative. What those hungry brains require is freedom. Treating children as citizens, rather than as consumers, can break that pattern, creating a shared spatial economy centered on public education, recreation, and transportation safe and open for all.”

Hence, routines ought to be adaptable to accommodate cultural nuances, provide freedom, and flourish within the ecosystem, encompassing family dynamics, friendships, social networks, and even visitors to the environment.

In today’s world, the influence of social media and external opinions has a significant impact on our society and the environment, both positively and negatively. When someone’s opinion on a matter of social change is shared online, they leave their digital footprint on that topic, potentially influencing the outcome of the issue.

An example of the power of digital footprint is the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge. What started as an awareness-raising campaign gained global attention through posting and reposting, ultimately spurring action. This demonstrates the potential for media and technology to facilitate widespread engagement and social change.What began as a grassroots effort by individuals affected by Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) evolved into a viral sensation, demonstrating the remarkable power of digital platforms to drive change and generate unprecedented support for a cause.

The ALS Association, a US-based non-profit dedicated to funding ALS research and patient care, found itself at the epicenter of this extraordinary fundraising phenomenon. Three individuals living with ALS-Pat Quinn, Anthony Senerchia, and Pete Frates,initiated the challenge in 2014, urging participants to dump buckets of ice water over themselves, film the act, and nominate others to do the same, all while soliciting donations for ALS research. The campaign spread like wildfire across social media platforms, captivating the attention of millions worldwide. Celebrities, influencers, and ordinary individuals alike enthusiastically embraced the challenge, propelling it to unprecedented levels of visibility and engagement.

At its core, the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge exemplified the transformative potential of social media in catalyzing social change. By leveraging the viral nature of digital networks, the campaign transcended geographical boundaries and cultural barriers, uniting people from diverse backgrounds under a common cause. Through the power of collective action and grassroots mobilization, the ALS Association succeeded in raising over $100 million’a testament to the immense impact of online communities rallying behind a shared purpose.

However, the campaign’s success also underscored the nuanced dynamics of digital activism and the complexities of translating online engagement into tangible outcomes. While the Ice Bucket Challenge achieved unprecedented levels of participation and fundraising, its long-term impact on raising awareness about ALS remained somewhat ambiguous.

Despite its initial focus on raising awareness about ALS, the campaign’s narrative gradually shifted towards maximizing financial donations, leading to concerns about the dilution of its original message. Moreover, the transient nature of viral trends meant that the campaign’s momentum eventually waned, raising questions about its lasting impact on public consciousness and engagement with the ALS cause.

Nevertheless, the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge offers valuable insights for

organizations and practitioners seeking to harness the power of social media for advocacy and fundraising efforts. By prioritizing transparency, authenticity, and community engagement, organizations can cultivate meaningful connections with online audiences and leverage digital platforms as catalysts for social change.

The ALS Ice Bucket Challenge serves as a compelling case study in the transformative potential of social media to drive positive change. While its legacy may be marked by both triumphs and challenges, the campaign stands as a testament to the profound influence of digital networks in shaping collective action and advancing social causes on a global scale.

Social media plays a significant role in my thesis, serving as a platform for generating accessible awareness about the trajectory of global issues. It enables individuals, whether directly affected or observing from a distance, to understand their role in driving change. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that this experience has to be owned and authored by the people who are being represented.