FISH-INS & BLACK / NATIVE SOLIDARITY IN THE 1960S

KABA

BY MARIAME

Fish-Ins & Black/Native Solidarity in the 1960s by Mariame

Kaba

Illustrations by Jon Bailiff

Half

Press 2023

Letter

[W]hen I got involved in the Civil Rights movement [...] I made a deal with my wife that I would never make a decision based on how will this affect my career.

―

Dick Gregory

For a long time, Dick Gregory has been one of my obsessions. I am interested in him as a political activist, artist, and healing justice practitioner. So every time I find interesting artifacts about Gregory, I collect them. This means that I have books, magazines, buttons, posters and lots of photographs about Gregory and his wife, Lillian.

A few years ago, I came across a brief description of Dick and Lillian’s fish-in protests in solidarity with Native Americans in the Pacific Northwest. I was intrigued, so I started researching and also collecting specific items related to their involvement in these protests. This publication offers a brief description of the fishins as a way to highlight a chapter in history that may be less well-known to modern audiences. The Gregorys’ involvement in the fish-ins is a concrete example of Black-Native solidarity. Perhaps you, like me, had never heard about the protests. I believe that knowing this history reminds us that we can in fact work for justice across differences. It’s been done and we can/should do so today.

5

When I had the idea to create a short zine about the fish-ins focused on the Gregorys, I reached out to my friends Brett Bloom and Marc Fischer of Half Letter Press to ask if they would partner with me to make it. I’ve worked with them a few times over the years and have always greatly respected their work. They agreed to design and publish the zine and for this I am so grateful. I met Jon Bailiff on Twitter and he created the wonderful illustrations that are included here. While social media is much maligned, I’ve been lucky to meet terrific collaborators who enrich the many projects that I co-create.

My thanks to Brett, Marc, and Jon for their contributions to this project. I hope those of you who engage with this publication will learn something that you perhaps didn’t know before and share it with others.

In peace & solidarity, Mariame

6

7

Puyallup citizen Allison Bridge’s arrest in a fishing encampment raid Sept 4th, 1970

Fish-In on the Nisqually

On March 1, 1964, local Native people of the Nisqually and Puyallup nations gathered along the banks of the Puyallup River in Washington State to exercise their tribal rights to fish. Game wardens, disputing those rights, had arrived in force to prevent them from casting their nets. Reporters were there as well. As Native people took out their own cameras and took pictures of the authorities; children played along the riverbank. Then actor Marlon Brando and San Francisco Episcopal priest John J. Yaryan cast gillnets into the river in solidarity with the protestors. They were quickly arrested.

The protest on the Puyallup River was relatively quiet. But it inaugurated a ground-breaking new phase of inter-nation activism in the fight for Native rights.

8

A History of Fishing Rights in Washington State

Isaac Ingalls Stevens, the first governor of the Washington Territory, aggressively forced and cajoled the Native people of the Pacific Northwest to sign away rights to 64 million acres of land. However, the Nisqually, the Puyallup, and the other peoples in the territory insisted on clauses guaranteeing them fishing rights to protect their food supply and their spiritual practices.

By the 1940s and 1950s, though, commercial overfishing threatened fishing stock. White Washington fishers responded by scapegoating Native peoples, arguing that their fishing rights were leading to stock depletion, and ordering them to abide by state conservation laws. This was also an excuse to advance ideological goals. Many whites believed Native people should be fully assimilated into American society.

The claim that Native people were responsible for overfishing was false. Between 1958 and 1967, Native people were responsible for 6.5% of the total catch, sports fishers for 12.2%, and commercial operations for 81.3%.

Nonetheless, Washington State continued to be

9

hostile to Native treaty rights. In 1953, Congress passed the Enabling Act, which gave state governments authority over Indian affairs. Washington game wardens soon began arresting Native fishers. Worse, several court rulings went against Native peoples, as judges found that the state had no obligation to abide by Native treaties.

The NIYC and Civil Disobedience

Native Americans largely avoided organized civil disobedience during the early 20th century. Importantly, the U.S. also chilled Native dissent by kidnapping and incarcerating Native children in violent institutions known as “Indian boarding schools,” effectively holding entire generations of Native young people hostage. This repression impacted organizing potential. The National Congress of American Indians (NCAI), the largest intertribal organization of the 1950s, was strongly opposed to protest, and displayed a banner that read “Indians Don’t Demonstrate.”

Older leaders argued against using the protest tactics of the Black Civil Rights Movement. In part, this was because of racism. Some Native people themselves were prejudiced, and they worried that white people would dismiss their movement

10

if it were associated with Black struggle. Some Native leaders also pointed out that the goals of the Civil Rights Movement (CRM) differed from those of Native people. The CRM was fighting for integration; Natives were fighting for the recognition of treaties and their right not to assimilate.

Younger activists like Clyde Warrior (Ponca) and Mel Thom (Walker River Paiute) were disillusioned with older leaders and inspired by civil rights tactics such as sit-ins and demonstrations. They formed the National Indian Youth Council (NIYC) in 1961 in Gallup, New Mexico, to use direct action to advance Native causes.

In 1964, the NIYC was contacted by members of the Nisqually and Puyallup tribes who had formed an organization called Survival of the American Indians Association (SAIA). Like NIYC members, the SAIA was frustrated with the slow pace of change and what they felt were timid tribal efforts to

11

Al Bridges, Jack McCloud and Janet McCloud on the Nisqually River during a Fish-In in 1968

Al Bridges, Jack McCloud and Janet McCloud on the Nisqually River during a Fish-In in 1968

resolve issues of tribal rights. They were committed to radical solutions. They organized the fish-ins to force confrontation with authorities; they planned to be arrested.

The NIYC and SAIA were directly inspired by the Black Civil Rights Movement. The first leader of the SAIA, Janet McCloud, said “The American Negro’s revolution has necessitated a change in the whiteman’s mental picture of the colored people of the world.” Puyallup leader Robert Satiacum insisted, “We can learn much from the Negro. There’s got to be more communication.” Another leader, Don Matheson, said, “Let’s face it, our fight is the same. This whole thing has given us a better understanding of the Negro’s problems.” Both men were quoted in a 1967 article in Ebony, a strong indication that Native interest in Black struggles was reciprocated.

The most powerful and direct influence of the Black Civil Rights Movement on the fish-in early on came through the involvement of Jack Tanner. Tanner, a renowned NAACP attorney and Regional Director, agreed to represent those arrested in direct action.

Tanner’s participation drew much criticism from other civil rights leaders, who accused him of grandstanding and failing to focus on the important issue of Black civil rights. But he persevered, and

14

his involvement was vital. He was mentioned in press coverage, which recognized the fish-ins as an important turning point. The connection with the NAACP and Black struggle helped the NIYC and SAIA present themselves as more confrontational and less conciliatory. They put the authorities on notice that they were not backing down.

15

Allison Kay Bridges Gottfreidson 1951-2009

16

Dick and Lillian Gregory

Direct Action and Violence

Leaders of the Nisqually and Puyallup disavowed the NIYC and SAIA. But they received support from members of virtually all Nations in the Pacific Northwest. In addition, Seminoles from Florida, Winnebagos from Nebraska, Blackfeet from Montana, Shoshone from Wyoming, and Sioux from the Dakotas all came out to support the demonstrations. Marlon Brando also agreed to join the fishers. The day after his arrest on March 1, 1964, 1000 Native Americans marched to the capital at Olympia. Though they met with the Governor, there was no settlement.

The fish-ins escalated over the next couple of years. In October 1965, police response turned violent. Game wardens deliberately smashed a fisher’s boat. Women and children on the side responded by throwing rocks. The police rioted, hitting people with clubs and pounding one girl's face into a tree stump. Republican governor Dan Evans refused to denounce the police viciousness and instead praised the wardens.

17

18

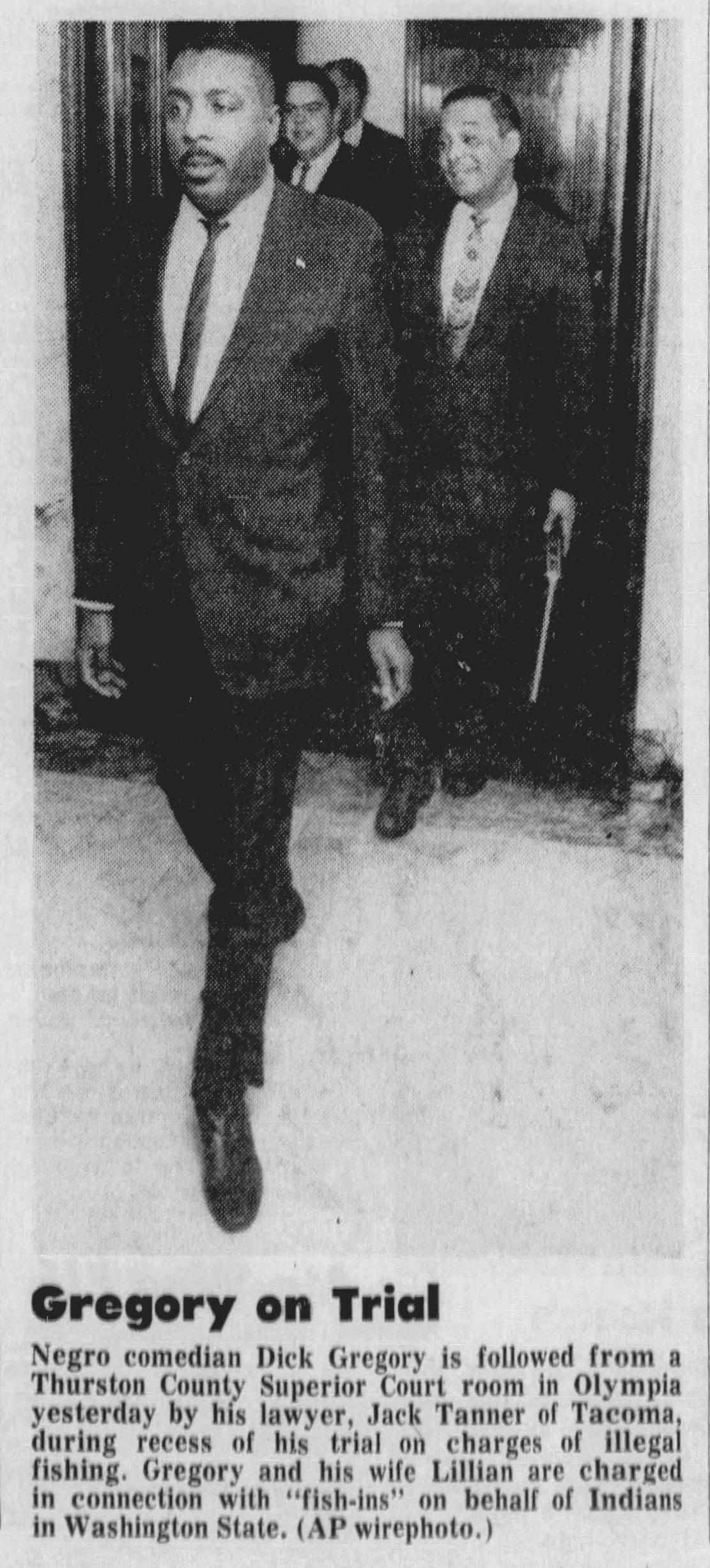

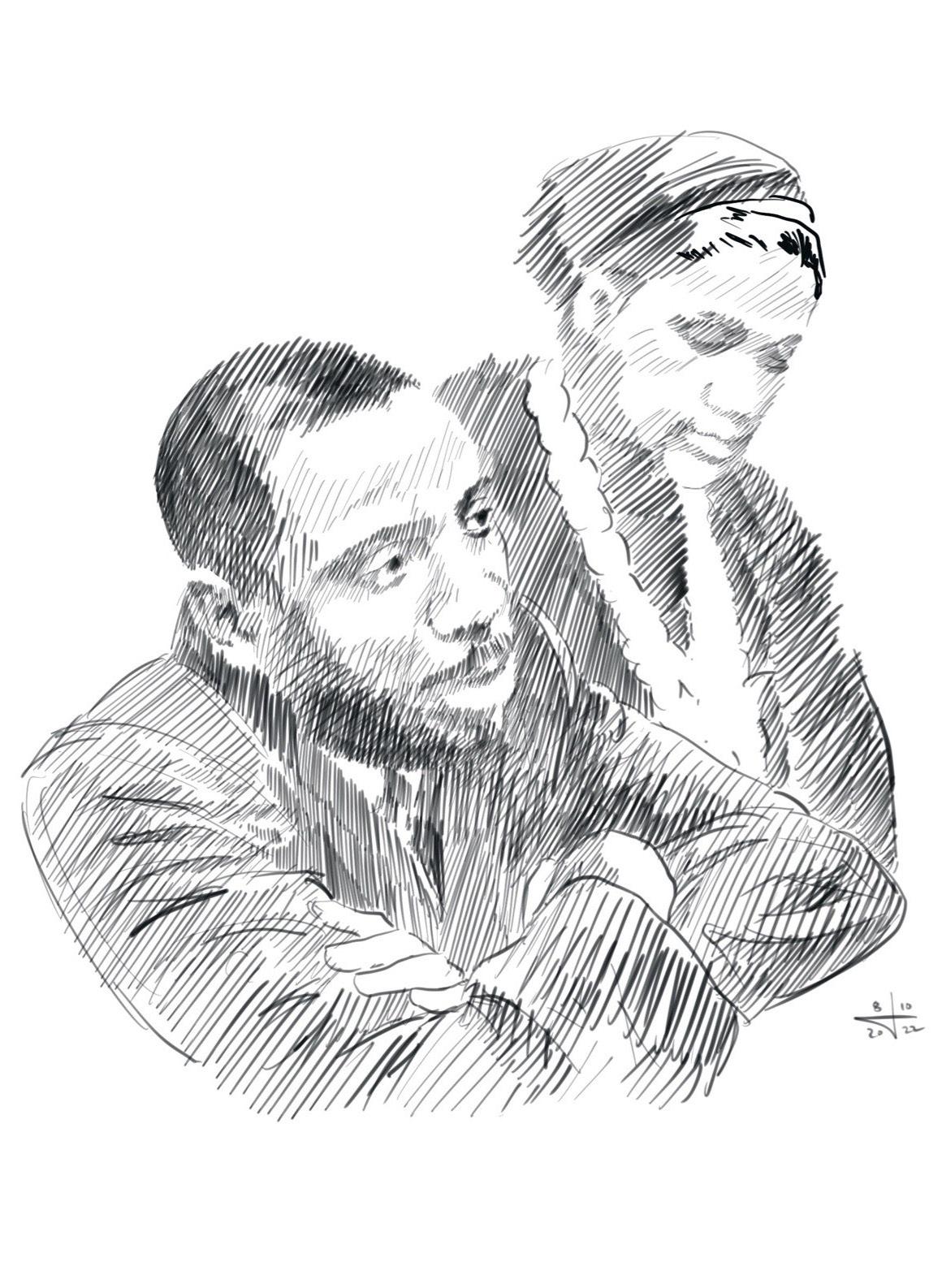

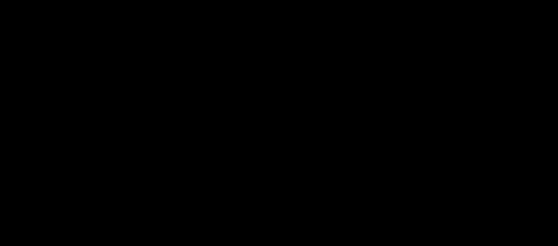

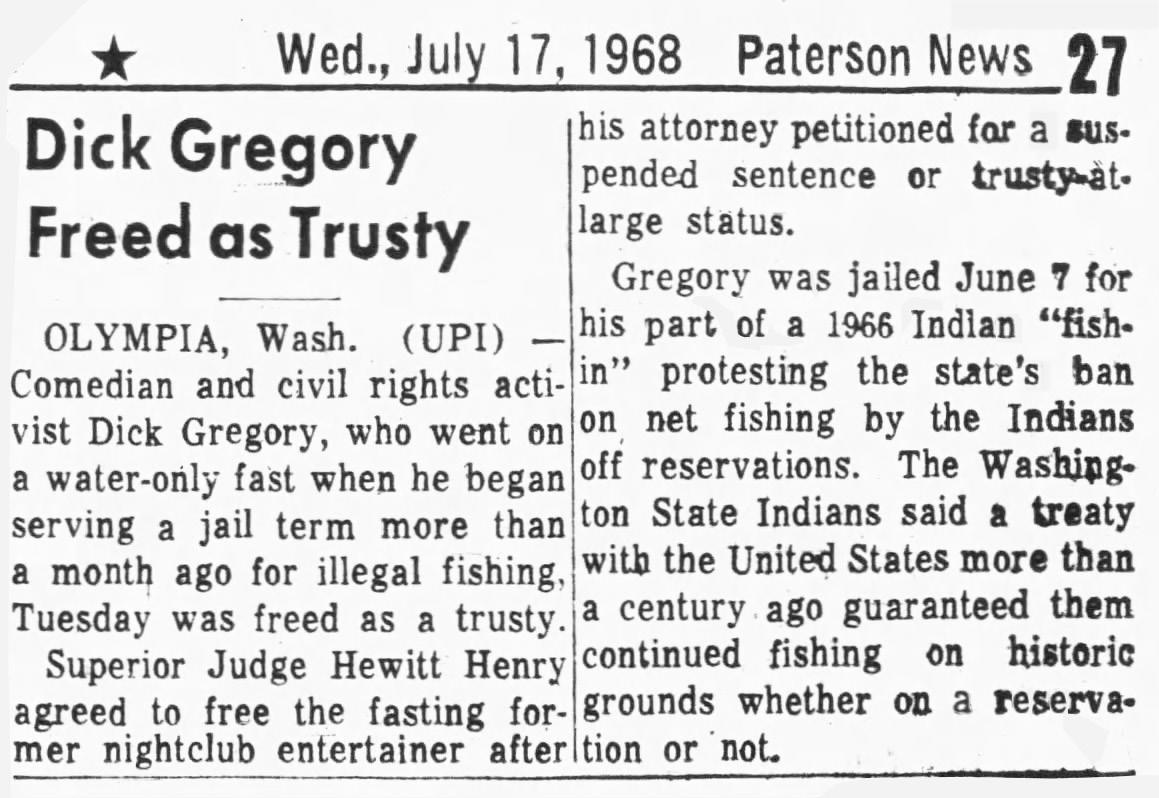

Press photo of Dick Gregory (left) and Attorney Jack Tanner (right), June 8, 1968

The violence attracted additional national attention. That led African-American comedian and activist Dick Gregory and his wife Lillian to become involved in the struggle.

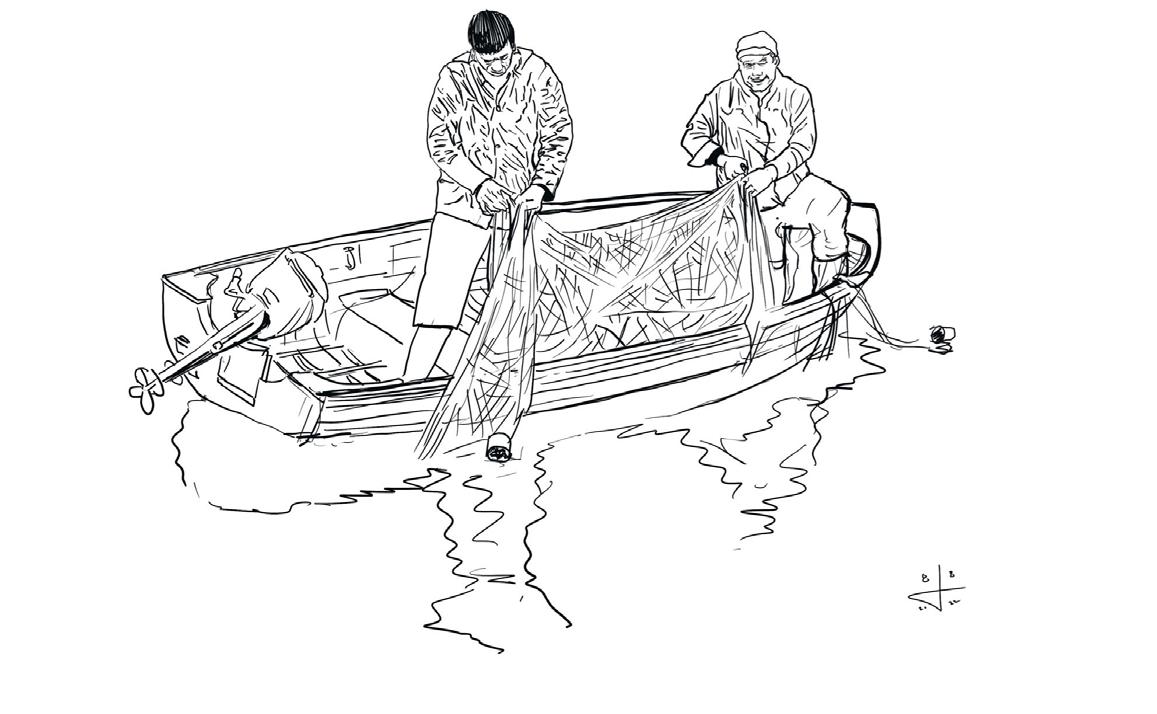

Dick Gregory

Gregory had been involved in the CRM for years and he made it clear that he saw Black and Native causes as linked. “We owe you an obligation,” he said, “No one should be free until the American Indians are free.”

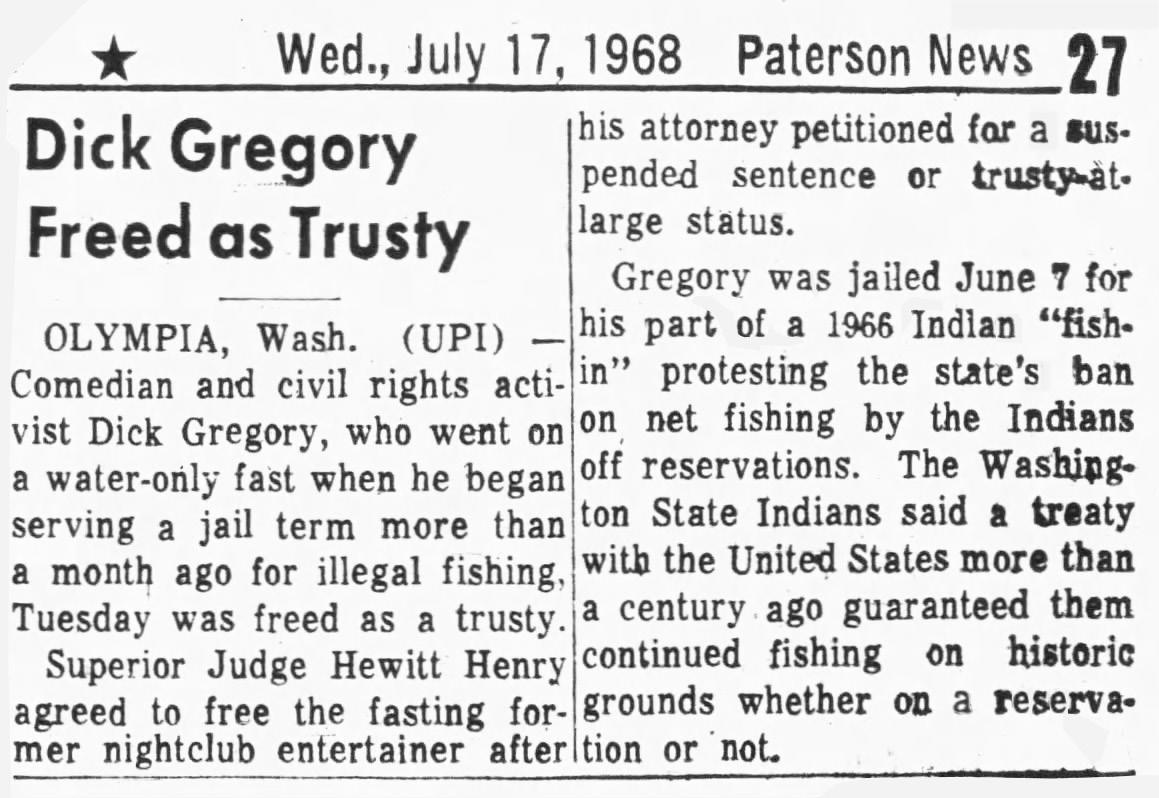

At the end of January 1966, following a comedy set in Seattle, Gregory joined Native fishers for a fishin. Wardens were reluctant to arrest him, fearing the publicity. They finally did, however, and he was jailed on February 15 in Olympia. His wife turned herself in a few days later.

Elmer Kalama, head of the Nisqually Indian Tribal council, condemned Gregory’s protest. He suggested that Gregory was “trying to turn this into a civil rights matter” and added , “We are not fighting for civil rights. We have our civil rights. We can vote and do anything any other citizen can do.

19

After appeals, in June 1968, Gregory began a 90-day sentence at the Thurston County jail in Olympia, WA. He immediately started a hunger strike living only on distilled water and bread, which lasted for 39 days before they removed him to a hospital. He served the rest of his sentence at his home.

Success Meanwhile, the NIYC and SAIA continued to organize. The activists were finally victorious in 1974, when a district judge ruled in United States v. Washington that Native fishers had the right to 50% of Washington’s fish. The Supreme Court confirmed the decision in 1979.

The SAIA and NIYC laid the groundwork for the future direction of Native protest and activism. Connections with the Civil Rights Movement proved vital for further actions, as did inter-tribal organizing. And the embrace of direct action was an important precedent for the occupation of Alcatraz Island in 1969, and for the American Indian Movement in the late 60s. The Dakota Access Pipeline demonstrations owe a direct debt to the fish-ins of the Pacific Northwest.

We just want our fishing rights.”

20

• https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/ nisqually-and-puyallup-Native-americans-winfishing-rights-through-fish-ins-1964-1970 • https://www.historylink.org/File/5462 • https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/ phr.2009.78.3.403 • https://depts.washington.edu/civilr/fish-ins.htm

21

Bibliography:

Actor Marlon Brando and Puyallup tribal leader Bob Satiacum just before Brando’s arrest during a fish-in, March 2, 1964

Fish-Ins & Black/Native Solidarity in the 1960s

by Mariame Kaba

Printed by Half Letter Press January 2023

Digital and offset printing by Mission Press, Franklin Park, IL

Half Letter Press PO Box 12588 Chicago, IL 60612 USA www.halfletterpress.com publishers@halfletterpress.com

It takes about 18 gallons of water to make one copy of this booklet. A print run of 2000 copies requires 36,000 gallons of water. We are offsetting water use by replacing a conventional toilet at a bookstore with a low flow, dual flush toilet. This will save 67% of the water used to make this booklet, reaching the offset in under two years.

Image credits

Front cover: APWIREPHOTO, Feb 15, 1966 (Olympia, WA), colorized by Mariame Kaba Pages 7, 8, 12, 13, 15, 16, 21, back cover: Illustrations by Jon Bailiff Page 4: By Herman Hiller, World Telegram staff photographerLibrary of Congress. New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3c21425, Public Domain, https:// commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1273587

Page 11: By Denver Public Library - The Native American Experience, Attribution, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/ index.php?curid=8064702

This publication is supported by the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. www.rauschenbergfoundation.org

Billy Frank Jr., River Revolutionary

Billy Frank Jr., River Revolutionary

Al Bridges, Jack McCloud and Janet McCloud on the Nisqually River during a Fish-In in 1968

Al Bridges, Jack McCloud and Janet McCloud on the Nisqually River during a Fish-In in 1968

Billy Frank Jr., River Revolutionary

Billy Frank Jr., River Revolutionary