17 minute read

In an ambiguous state. The role of ambivalence and mimicry in the recognition of a Palestinian State. - Ms. C. E. Potts

from Serpentes Issue 5

In an ambiguous state. The role of ambivalence and mimicry in the recognition of a Palestinian State. - Ms. C. E. Potts

Introduction

Since the decolonisation period beginning in the 1920’s, the international system has witnessed a proliferation and a subsequent normalisation of peoples demanding the right to choose their own political status; their right to self-determination. This right of selfdetermination has become such a powerful principle that it has been enshrined in Article 1 of the Charter of the United Nations (UN). Yet whilst a cornerstone ethos, the reality of self-determination has been experienced variably and unequally by different entities over time (UNPO, 2017). The study of such entities which seek this right to self-determination, but face difficulties in its realisation, is a nascent, growing body of scholarly work. Much of this literature employs these contested, anomalous geopolitical entities as a lens to further explore, critique and subvert traditional geopolitical discourses, such as sovereignty, statehood, recognition and legitimacy (Jeffrey et al., 2015).

In particular, this essay addresses a lacuna in research surrounding non-state diplomacy outlined by McConnell et al. (2012). In their paper, McConnell et al. (2012) investigate the diplomatic practices of unofficial diplomacies to secure legitimacy, using Bhabha’s (1984) concept of colonial mimicry as a theoretical tool. Their focus on diplomacy enables them to examine and challenge discourses of recognition, legitimacy and sovereignty. They find that diplomatic mimicry emulates and reproduces, yet simultaneously threatens the “gold standard” (p.805) of traditional state diplomacy, by blurring and unsettling the distinction between the ‘real’ and the ‘mimic’. This essay seeks to utilise this poststructural and performative framework of investigation to explore the mimicry of the State of Palestine. It empirically examines the mimetic, hybrid practices and structures of Palestine which have evolved over time as a strategy to gain international recognition and self-determination, and exposes its ambivalent position within the international system. Through this process, this essay provides a postcolonial critique of the western-centric concept of statehood, transgressing and overcoming its binary characterisation. As a product of past and present colonialism (Thompson, 2003), Palestine’s evolution from Ottoman Empire to statu nascendi (a forming state) provides a powerful lens for reconceptualising such norms and discourses.

Empire to statu nascendi

The territorial space of Israel and the Occupied Territories (OT’s) was once a part of the Ottoman Empire before its collapse during WW1. After the war, the resulting territories were split up between the Allied powers under the framework of the League of Nations, founded in 1920 (Thompson, 2003). The League created the mandate system in which an Allied power would have sovereignty over an occupied territory until it was deemed capable of governing itself. In 1923, Palestine was placed under British Mandate and was given the highest classification: it was almost ready for independence (Maguire and Thompson, 2017). This period also coincided with a surge of Zionist interest in Palestine, who sought to create their Jewish State within this territory, as a neo-European state

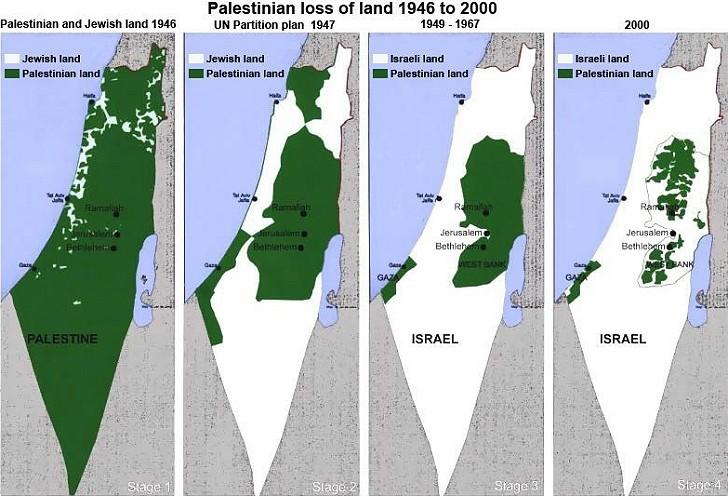

in the Middle East, bringing ‘civilizing benefits’ to the region (Karsh, 1994). The 1917 Balfour Declaration announced British support for a Jewish State in Palestine, evidencing Britain’s compromised position, as it also promised independence to the Palestinians. As a solution, the UN General Assembly (UNGA) proposed the Partition Plan in 1947, in which the Palestinian inhabitants would receive 45% of the land, and the Jews would obtain 55%. The Arab countries rejected this offer, yet in 1949, Israel declared itself a sovereign state and received UN membership.

Following the failed Partition Plan and the end of the mandate system in Palestine/Israel, a series of conflicts began between Israel and the surrounding Arab states. These conflicts culminated in the Six Day War of 1967, in which Israel gained control of the West Bank (WB), Gaza Strip (GS), East Jerusalem, the Sinai Desert and the Golan Heights. During and as a result of this conflict, millions of Palestinian refugees fled the territory (Efrat, 2006). Since the Six Day War, the last 50 years have witnessed a series of failed peace talks between Israel and Palestine, several non-violent and violent resistance movements, as well as out-right conflict between Israel and the Palestinian people. Today, Israel occupies the WB and GS. This occupation, combined with the construction of illegal Israeli settlements in the WB, and a ‘security fence’ surrounding the WB- which UNHCR Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination labels a “racial segregation and apartheid” (2012, p.6)- limits the Palestinian’s capability of self-determination. Whilst Palestine has seen an increasing level of international recognition and support over the last half a century, the Palestinian people seem to be no closer to achieving their goal of self-determination.

The Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO), the foreign representative body of the Palestinian people and the primary body of Palestinian nationalism was founded in 1964. The Palestinian National Authority (PNA) forms the administrative organisation of the Palestinian people, this Fatah-led internationally supported government nominally governs the WB and GS. However, in 2006 Hamas won the PNA elections and subsequent conflict between Fatah and Hamas has meant that Hamas is illegitimately in control of GS whilst Fatah governs WB. The PLO and PNA seek self-determination of the OT’s with East Jerusalem as the capital (BBC, 2017). They wish to stop and remove illegal Israeli settlements, secure safe return of Palestinian refugees, an end to Israeli violence, and to have international recognition and legitimacy of a sovereign, independent Palestinian State (Mansour, 2018).

A Palestinian State?

In 1988, the PLO unilaterally declared a State of Palestine and by February 1989, 89 countries had formally recognized it. In 2011, President Mahmoud Abbas applied to become a full member state of the UN. This application was rejected due to a US veto, yet in 2012, the UN ‘upgraded’ the PLO to become a permanent non-member observer state. Currently, 137 states officially recognise the State of Palestine, with notable exceptions of the US, Israel and many European Union (EU) states. Clearly, the statehood of Palestine is a controversial and ambivalent phenomenon, with variable spatial and temporal recognition. A key objective of the PLO is to be a fully recognised state, as they believe that it will empower them to achieve self-determination and have more leverage in peace talks (palmissionuk, 2019b). This ambivalence has led to a great deal of debate within international law as to whether Palestine legally qualifies as a state and also whether ‘legality’ even matters. 25

The 1933 Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States has been the predominant instrument used to define the criteria of statehood. The convention originally highlighted four aspects that would constitute a state, with a fifth added later:

1. Permanent population

2. Defined territory

3. Government

4. Capacity to enter into relations with the other states

5. Independence

Whilst these criteria make up a majority of discussions around statehood, many challenge this framework and critique it for its narrow perspective. Akram (2014), for example, contends that Namibia was declared and internationally recognised as a state before it had achieved independence, as it was still under occupation by South Africa. Quigley (2010) also argues that simply the act of majority recognition by other states, makes an entity constitute a state without needing to meet these criteria (it is for this reason that Quigley confirms Palestinian statehood). Postcolonial scholars also tend to critique this restricted notion of statehood, arguing instead for ‘Degrees of Statehood’ (Clapham, 1998). It is hence clear that what makes a state is a contested subject, which adds further confusion to the categorisation of Palestine.

Utilising the Montevideo Convention, it remains unclear whether Palestine fits the criteria of statehood. Crawford (1990) underlines the Israeli occupation as a marker that Palestine is not independent and therefore, does not fit the conditions. He also states that whilst the PNA has some influence in the OT’s, it does not have full sovereignty, which therefore means they do not have a sufficient government to meet condition four. Stephan (2006) furthers this argument by highlighting the corruption and lack of internal legitimacy of the PNA, due to the Fatah-Hamas conflict. The OT’s also don’t have officially agreed borders, and they are under continual infringement by Israeli settlements (Maguire and Thompson, 2017). However, Thompson (2003) contends that these issues are all as a result of the continuing colonialism within Palestine, and that it is Israel’s actions, not Palestine’s, that are fundamentally holding them back from meeting the Montevideo criteria. The PLO have shown significant capacity of entering into relations with other states, and despite the large diaspora, the OT’s have a steady population (Akram, 2014).

Despite this uncertain position vis-à-vis statehood, there is little doubt within academia and the international system of Palestine’s right to statehood in terms of self-determination (Crawford, 1990). Since the 1975 UNSC Resolution 32336 which recognised the Palestinian people’s right to self-determination, national independence and sovereignty, Palestine’s right to statehood has been ratified.

Mimic Man: Performance and Recognition

Acts of recognition from state actors are important occurrences for contested states, particularly for Palestine (palmissionuk, 2019a). Theoretically, a state does not have to be recognised to be a state, but it does confer legitimacy onto that actor. Without widespread recognition, foreign relations and contribution to international organisations becomes problematic. McConnell (2012), explains how sovereign states perform discourses of recognition to affirm their own position of power. Simultaneously, these acts of performance work to exclude non-sovereign others, such as contested states. Such unrecognised actors present a threat to the hegemony and balance of the inter-state system. However, full exclusion of unrecognised states rarely occurs (Bryden, 2004), and Ker-Lindsay (2015) examines the extent to which states can engage with unrecognised entities without conferring official recognition. Ker-Lindsay argues that state actors have a wide room for manoeuvre when it comes to diplomatic engagement with unrecognised states, as indirect or implied acts of recognition do not confer recognition if the intent to recognise is absent. Despite this, both McConnell (2016) and Ker-Lindsay (2015) discuss symbols of recognition, such as flags, titles and meeting places, that some state actors try to avoid when engaging with non-states, to ensure recognition isn’t implied. It is interesting to note, that whilst the Montevideo Convention may be the official basis for legal recognition, the act of recognition is still fundamentally a political decision, undertaken by the sovereign state (Silverberg, 1998). As previously mentioned, Palestine’s position within the inter-state system is uncertain- a majority of states recognise the State of Palestine, yet key actors have prevented it from achieving the full consequences of widespread recognition. However, it is obvious that this contested state has come a long way within the international arena since the very beginnings of Israeli occupation when it was considered to be an act of hostility against Israel to even mention the existence of Palestine (Anders, 2015).

This growth in recognition and legitimacy has a lot to do with Palestine’s changing governmental and diplomatic practices. When the Partition Plan was rejected in 1947, it was a group of Arab countries that made this decision, not a Palestinian government. Silverberg (1998) argues that what existed in the territory of Palestine before British occupation, did not resemble the western ideal of a state. Following the orientalist tradition, Palestine did not have external legitimacy, because its cultural and political make-up was considered ‘weak’, and ‘uncivilised’. Yet over time, the Palestinian people have adopted the trappings of statehood; they have performed and reflected the discourses surrounding sovereignty to meet the normative standards (Caspersen, 2015), such that they have become a hybrid actor.

The concept of mimicry, as a strategy employed by the colonised to resist and adapt to the power of the coloniser, are accredited to the postcolonial scholar, Homi Bhabha. Bhabha described mimicry as the desire within the coloniser for a “reformed, recognisable, Other” (1984, p.126). In this case, it is the western-centric state system that demands entities to perform the discourses that is has produced, in the form of Westphalian sovereignty (Silverberg, 1998). Yet whilst Bhabha describes how the colonised wishes to become an authentic, identical entity, he describes mimicry as a metonym: a form of resemblance that differs, “almost the same, but not quite” (p.126). These mimetic actions create hybrid entities, a multiculturalism which intertwines the colonised with the coloniser, the original with repetition. The institutionalised statecraft which has taken place in Palestine reflects this process of mimicry. The creation of the PLO in 1964, was the first sign of a Pales

tinian form of governance loosely resembling the western ideal. Throughout the 1970s, the PLO resembled a terrorist, resistance government-in-exile in Tunis, which demanded the destruction of Israel. In 1972, the PLO famously murdered 11 Israeli Olympic athletes in Munich as a performance of resistance. Despite this militant character, the PLO was gradually given legitimacy in the international sphere. In 1965, the Special Political Committee of the UN allowed the PLO to attend meetings of the Committee and present a statement (palestineun, 2018). In 1974, the UNGA allowed the PLO to sit in sessions as an observer, and in 1981, the Asian Group of the UN gave the PLO full membership. The attendance of such sessions and events signify the PLO’s hybridity as it engaged in the formalised state system, attesting to its growing legitimacy.

During the first Intifada in 1988, when attention around the conflict was high, the PLO unilaterally declared the independence of the State of Palestine. This declaration was the first time the PLO recognised the State of Israel’s right to exist, as it claimed independence within the 1967 borders. It was clear that these moves were signalling a change in Palestinian leadership, as Abbas said to Yasser Arafat at the PLO’s Central Committee, October 1993 “it is now time to take off the uniforms of the revolution and put on the business suits of the nascent Palestinian state” (Silverberg, 1998, p.31). This line itself emblemizes the mimicry that the leaders recognized needed to be undertaken; they now needed to look and act like state leaders, in order for them to be recognized as such. Following the Oslo Accords in 1994, the PNA was created, forming the institutional character of a state with legislative and executive functions. Whilst the PNA only concerned matters of civil affairs and internal security, it was made to be a democratic body, and mirrored many of the duties of a ‘conventional’ government. By creating such an institution that mimicked the structure of other states, and matched western ideals of a democratic government, Palestine garnered greater external and internal legitimacy (Caspersen, 2015). However, securing the trappings of statehood did not secure Palestine’s recognition; the EU only endorsed the idea of a Palestinian state in 1999, and the US agreed only in 2002. This highlights the ambivalence of Palestine; its right to self-determination was unquestioned by this point and it had many features of a western state, yet it wasn’t accepted by western powers- almost the same, but not quite.

Membership of the UN is often seen as the ultimate marker of statehood. Palestine’s characteristic ambivalence as an entity is displayed evidently in its relations to the UN. Despite its non-membership status, Palestine enjoys a unique position as being only one of two permanent observer states, and having six delegates rather than the usual two (UNA-UK, 2018). Furthermore, in 2011 UNESCO permitted Palestine to join as a full member. Other symbolic signs of recognition have also increased the legitimacy of Palestine: in 2012, at the request of Abbas, the UN updated all mentions of ‘Palestine’ in its Blue Book to “State of Palestine”, and in 2015 the UNGA voted to fly the flags of permanent observer states outside the UN headquarters. These symbolic signs of statehood are incredibly important (Ker-Lindsay, 2015). Figure 1, which is taken from Palestine’s UN website, demonstrates the significance which Palestine attributes to such symbolic markers of legitimacy. Palestine has formed itself to fit the UN principles of statehood to the point that its national flag flies outside the UN’s doors, yet it is not quite a full member.

Whilst Anders (2015), notes that all EU member countries agree on Palestine’s right to statehood, they disagree on whether recognition should be granted before or after the success of peace talks with Israel. This ambivalence towards recognising a Palestinian State at EU level is also found even within individual state approaches.

In 2015, the Italian parliament adopted two motions in relation to Palestine: one promotes the recognition of a Palestinian state, but the other conditions this recognition on the basis of peace talks and an end to the Fatah-Hamas conflict (Stavridis et al., 2016). By endorsing both motions, the Italian government reinforces its hesitant position vis-àvis Palestine, giving Italy much leg room in deciding when and if to recognise the State of Palestine. McConnell et al. (2012) consider the ways in which geopolitical anomalies react to such responses from state actors concerning their legitimacy, and find that for micropatrias (“self-declared parodic nations” (p.1)) any form of contact, or even no contact, can be constituted as recognition. This is a useful concept to apply here, as it draws parallels to Palestine’s and Israel’s conflicting responses to Italy’s motions. Both parties thanked the Italian government for entirely opposite reasons: Israel perceived refusal to recognise a Palestinian State, whilst Palestine saw acknowledgement of statehood despite a lack of official diplomatic recognition. This uncertain act of (non)recognition exposes the political nature of decisions concerning granting recognition and highlights the reluctance often involved in widening the exclusive circle of statehood. Yet Italy’s response did not place Palestine on either side of the ‘inside’/‘outside’ binary of statehood, rather it placed Palestine in a fuzzy in-between space, attesting to Bouris and Fernandez-Molina’s (2018) “betwixt and in-between” (p.309) characterisation of contested states.

Resemblance and Menace

By employing Bhabha’s mimicry as a postcolonial tool to empirically investigate Palestine’s diplomatic actions, normative concepts and discourses of the hegemonic ideologies of statehood can be deconstructed and destabilised. Mimicry and the ambivalence it produces disrupts the authority of the state system; a double vision of “resemblance and menace” (p.127). Palestine’s progression towards an archetypal state, via the use of hybrid strategies, reveals the malleability of the inter-state system, in concurrence with Silverberg (1998). The notion of a static, fixed set of states is thus challenged, as the performative actions of contested states garner them recognition and legitimacy. Via creating institutions resembling democratic governments, embassies and joining international organisations, Palestine has carved a place for itself within the international sphere, unsettling this image of a permanent, hegemonic system.

Through challenging these notions of statehood, Palestine’s ambivalent position of statu nascendi also disputes the fixed binary between those ‘outside’ and those ‘inside’ the state system. This finding matches McConnell et al.’s (2012) assessment of TGiE, and finds agreement with Sidaway (2003) who contends that it is the ‘excesses’ of these postcolonial actors which separate them from the western ideal. This ‘excess’ has been typically understood as a weakness, illustrating the inherent hierarchies present in the international system, as recognised by Agnew (2005). The very fact that entities desire to emulate a western discourse of statehood reveals this power imbalance, yet the subversive power of mimicry simultaneously threatens the coloniser. Sidaway (2003) contends that there is a need to move away from such fixed understandings of statehood which rely on the singular ‘pure’ reference of the western model. Maurer’s term ‘sovereigntynostalgia’ (2001, p.495 cited in Sidaway, 2003) explains that this ideal has always been a wishful imagination rather than a reality. Palestine’s ambivalent position within the grey areas of statehood contribute to this theory, arguing for an expansion of the notion of statehood, finding evidence for Clapham’s (1998) argument to consider ‘Degrees of Statehood’.

It is therefore clear that the dominant notions of statehood and recognition are insufficient as they do not match the lived realities of international actors. The hybridity and ambivalence of Palestine exposes the messy and fragmented nature of the hegemonic state system. This emphasises the need to reconceptualise normative understandings of it, through applying contextual framings that appreciates a graduated, spectrum of statehood and recognition.

A Horse with Black and White Stripes is a Zebra

In 1993, Netanyahu berated the then president of Israel for acknowledging the existence of a Palestinian state indirectly within the Declaration of Principles. He used the analogy of a zebra to explain that by talking to and about Palestine as if it were a state within the declaration, this essentially conferred legitimacy and recognition of statehood. Quigley (2011), has appropriated this analogy to make his key argument: Palestine is a state, because it looks and acts like one, in the same way that because a horse with black and white stripes looks like a zebra, it therefore is a zebra. Yet here it is possible to further adopt and distort this metaphor, employing the lens of mimicry. A horse is a horse, even if it has black and white stripes painted in the finest detail; it may look like a zebra, it may even be possible to train it to act like a zebra, it could also live among zebras, but it will always be different. This metaphor symbolises the mimetic and hybrid strategies of Palestine, and its position of ambivalence, which have been investigated. 30