7 minute read

The Geo-Economics of Global Trade - James Harrabin

from Serpentes Issue 5

Geo-economics is a tool used by states to further geopolitical power. The term was coined by Edward Luttwak, who was a consulate to the US Department of State, as well as the national security council and is best described by Vusal Gasimli in his book ’GeoEconomics’: Economics, politics and geography have influenced each other throughout the history of humanity. Geographical placement determines the existence of natural resources, territory, distance, climate and other important factors in economic development. In other words, geography is a determining factor in the environment surrounding economics.

Today, geo-economics can arguably be seen as more important than traditional geopolitical tools and military power. The most commonly used geo-economic tool are economic sanctions. Tariffs, quotas and other protectionism policies all wield geo-economic power, especially for larger economies, such as the US, China or EU, yet control over global trade routes can give smaller countries power.

In the same way Russia has military interests in the Bosporus River, as it gives access to the Mediterranean Sea, large economics have geo-economic interests in the major trade routes. The Choropleth shows that much of the globes trade is concentrated around several bottlenecks: The Suez and Panama Canal, The Persian Gulf and the Maritime Silk Road (connecting Europe, the Arabian Peninsula and China). Control over who accesses these passages depends on the how the passages are classed. Territorial waters (12 nautical miles from the coastline) allow all foreign vessels innocent passage, according the 1982 UN Convection on the law of the Sea. Internal waterways (where a states sovereign territory exists on both sides of the passage) give complete control over the passage, and thus the state can choose which vessels are allowed passage.

Today, most products are not produced where they are sold, requiring them to be transported. The cost of transportation has consistently lowered over the course of history, due to economies of scale and containerization. Cost is driven by competition and trade bottlenecks have competition. Consider a shipment going from Guangzhou, China to New York. This route is 22,000km via the Panama Canal, 21,500km via the Panama Canal or 16,500km shipping to the US West Coast and on a train across the US. The Panama Canal charges $90 per container, so for the largest Panamax ships (designed especially for the Panama Canal) this can equate to $1,170,000 when fully loaded. Meanwhile the Suez Canal charges lower tolls, meaning it can be cheaper to take this route. The train, however, can save up to a week in time, which is more important for certain products.

This shows how competition is driving countries to reduce tariffs, costs and barriers to trade, affecting the cost of products. This is to increase the amount of trade flowing through a particular passage, not only so that the country increases its revenue, but also to increase their geo-economic power, giving them greater lobby on the global stage. In an increasingly interdependent and interconnected world, preventing trade from reaching its destination, through trade blockades, could collapse economies and governments. As the North Eastern and Western passages emerge between the melting ice, eight countries are fighting to gain sovereignty. This then enables them to declare whether these waters are internal waterways or territorial waters, giving them greater geo-economic power. One could now argue control of global trade wields more power than a strong military. We all depend on global trade, yet those who ultimately control it, often lie far from the governments we elect.

The Future of Global Trade

There are three major factors which are likely to affect global trade in the future. The first is cost. As identified above, cost is the primary factor in deciding how a company will transport goods. Through the course of history, the cost and speed of transport has consistently reduced for all modes of transport and with further technological advances, it is likely that it will reduce further. This means that we can expect more products to be transported by air and over land, as these methods are faster and more direct. Further, technological advances, especially in robotics are moving manufacturing away from the developing world and back to more advanced countries. The prime example of this is the Tesla Gigafactory in Nevada. This factory has the ability to produce 35 gigawatt-hours of battery cells per year and 50 gigawatt-hours of battery packs per year, or equivalent to supplying the batteries for 500,000 Tesla cars per year. Despite this, the factory employees just 6000 employees, many of whom work in product development. It is likely that more firms will follow suit in bringing production closer to development offices, which will change the geography of global trade.

Secondly, oil can be argued to have had the biggest geopolitical impact in history. From Winston Churchill buying a controlling stake in the Anglo Persian oil company, the forerunner of BP, Germany’s attempts to secure the Baku oil fields in WWII, Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait or last September’s missile attack on Saudi oil facilities, oil has been a source of conflict throughout the 20th century. Yet now, as the world looks towards more renewable sources of energy, a power shift is occurring. Demand for batteries and solar cells is likely to increase. Currently these are predominantly produced by private firms, thus giving them strategic power. Despite this, currently, fossil fuels are still substantially cheaper and so in higher demand. The US’ discovery of plentiful shale gas deposits will enable them to export, further reducing the power given to OPEC and Iran who control the Persian Gulf passage.

The final major factor likely to influence global trade is China. In 2018 China exported $2.5tn worth of goods (see the graph, right), or 13.5% of global exports. The majority of these went to the US and Europe, placing strategic value on the Suez and Panama Canal. However, as Chinese standards of living rise with incomes, imports have increased (as shown in the graph). Further, higher wages are reducing the economic advantages to Chinese manufacturing.

Consequently, it is likely to assume China will demand more imports from South East Asia and Africa in the future, where manufacturing is starting to relocate to. This will place greater significance on the South China Sea trade route.

As a result of increasing wages, the Chinese government have invested to try and reduce the cost of transport, reducing the prices of Chinese goods. One example of this is the ‘belt and road initiative’, which is a $1.4tn global trade network. The network includes the Gwadar Port, Pakistan, giving the China’s landlocked western region of Xinjiang ocean access, the China-Myanmar oil pipeline, which has provided Beijing with its first overland access to Middle East crude that skips the Malacca Straits choke point, the Chinese

controlled Greek port of Piraeus, which serves as a maritime gateway to Central Europe alongside a planned Belgrade-to-Budapest high-speed rail link. These projects, however, represent a small amount of funding compared to the diagram above, which shows Chinese official aid projects globally. These investments have increased China’s power, through the ability to withhold funding, as well as increasing their geo-economic power via the new Silk Road.

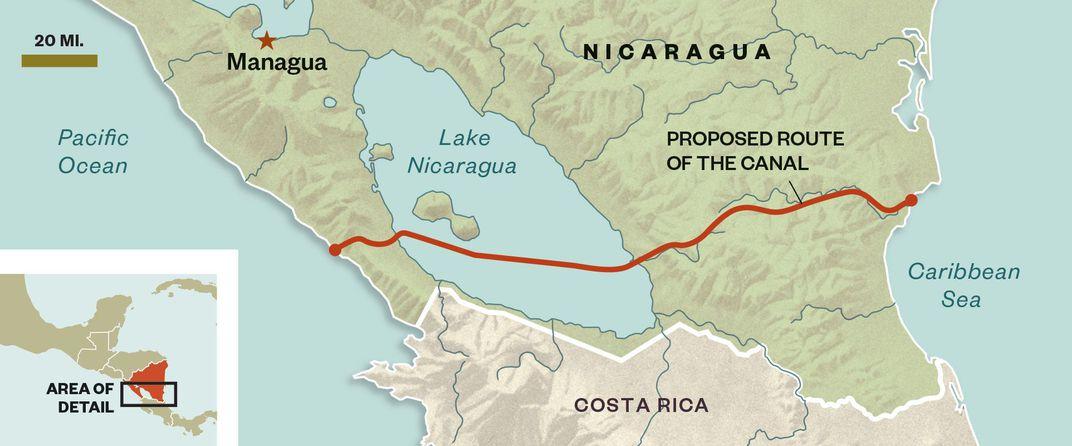

The proposed Nicaragua Canal is another example of Chinese efforts to increase geoeconomic power. While the French still controlled the Panama Canal in the early 20th century, the US explored attempts to create this passageway, but this became defunct when they purchased rights for the Panama Canal in 1904. The project resurfaced in June 2013, when Nicaragua’s National Assembly granted a 50-year lease for Wang Jing (a Chinese billionaire) to finance and manage the construction of a Nicaragua Canal. Whilst some major works have taken place, in 2015, media reports suggested the project would be delayed and possibly cancelled because of financing problems. Officially, the HKND Group, who had been granted the lease, stated that financing would come from debt and equity sales and a potential initial public offering, however it is likely that there was further backing from the Chinese government. The passage would inevitably allow all Chinese vessels lower fees to access Europe and the US east coast, thus lowering the cost of production for Chinese manufacturing. Currently, the HKND group states work is ongoing, however there is no evidence of this, so it is likely that the Nicaragua canal will not be completed soon. Figure 2: Nicaragua Canal 20