6 minute read

Why has Africa not benefited from globalisation to the same extent as other countries? - Jeff Xi

from Serpentes Issue 5

Globalisation for the last three decades has generated intense debates, public demonstrations, and heated street protests. Globalisation is a term which has been used to describe and explain many worldwide phenomena. It has been given positive connotations by those who advocate greater economic integration across national borders, while it has been fiercely criticized by those who see it as a threat to social connections and as the advancement of unrestrained capitalism, which undermines the Welfare State. Many would argue the ‘golden age’ of globalisation is over. Today’s trade tensions has been under way since the financial crisis in 2008-09. International investment, trade, bank loans and supply chains have all been shrinking or stagnating relative to world GDP. Globalisation has given way to a new era of sluggishness.

Since its very first introduction three decades ago, globalisation has evolved into a complex phenomenon, for which in today’s world involve many different factors in the economic, social, and cultural spheres. Rapid improvement in transportation and communication technology and the liberalisation of trade restrictions and foreign investment have been the major factors that has enabled the globalisation process. The explosive improvement in transportation technology has played a critical role in faster distribution of goods across long distances at lower costs. Immense improvements in containerisation has allowed radically lowered cargo transport charges. For example, over the last 25 years, sea transport unit costs have decreased by over 70%, while air-freight costs have fallen by 3 to 4% year-on-year. The result has been a boost in trade flows, as transport costs are now less likely to cancel out the gains. International migration has increased due to globalisation; Since 2005, the number of travelers crossing international borders each year has risen by around half, to 1.2 billion. The basis of globalisation is foreign trade movement of goods and people are vital for globalisation. Information and communication technology have also played a major role in globalisation, as the number of people using the internet has increased from 900,000 to more than 3 billion. Accordingly, the internet gives all firms, both domestic and TNCs alike, easier access to foreign markets. Liberalisation of foreign trade and investment policy has speeded up the globalisation process. Another crucial factor that boosted if not enabled globalisation is the reduction and removals of trade barriers, carried out by the WTO (World Trade Organisation), as well as the construction of new trade blocs such as the European Union (EU).

Globalisation is no longer a new concept to the world, but Africa is yet to benefit from the effects of globalisation. The continent has been blessed with the natural advantage of having large reserves of oil, but it is still plagued with criminality, corruption, and autocracy. Africa as a continent is one of the biggest exporters in the world, with a GDP of more than 6.814 trillion dollars in 2018. Despite all the apparent wealth and resources, its poverty rate is at an astonishingly high 41%; the income inequality becoming a huge issue in most African countries. Apart from brief spurts of growth in the recent decades, this integration into the global economy does not seem to have led to sustained development. As the of Secretary of the UN have once said, ‘globalisation is not a tide that lifts all boats.’ He argued that even those who benefit from globalisation feel threatened by it.

The location of Africa is a major factor that has limited potential benefits from globalisation. There are no close potential developed countries that can support and trade with Africa, whereas China is close to Japan and South Korea. The major economies can pump investments into the country, boosting the economy immensely. Africa also has a long history of colonisation. The Sub Saharan African nations were kept under iron colonial control until 50 years ago. They were split up into countries based on boundaries drawn by the colonial powers, and these separations often produced multi-racial, extremely volatile populations. With these pre-made strains in their history and culture combined with the fact that their economies were run for the benefit of their colonisers until very recently, the African countries have been at a serious disadvantage. Many African countries are perhaps politically not ‘aligned’ with the major economies like America, and therefore deducing the goods exchange rate. This left some African countries with very little economical support, though indicators show that Most countries have moved ahead with trade and exchange liberalisation, eliminating multiple exchange rates and nontariff barriers.

However, the problem for Africa could be much more fundamental. Africa’s integration into the global economy might not have been the most ideal; Africa is stuck in a trench of low-value-added goods, bringing in little income into Africa, notably cheap agricultural commodities and minerals, which leaves it extremely exposed to international price fluctuations, attracting few investors and technology inflows, and having almost none backward linkages to the rest of the world economy.

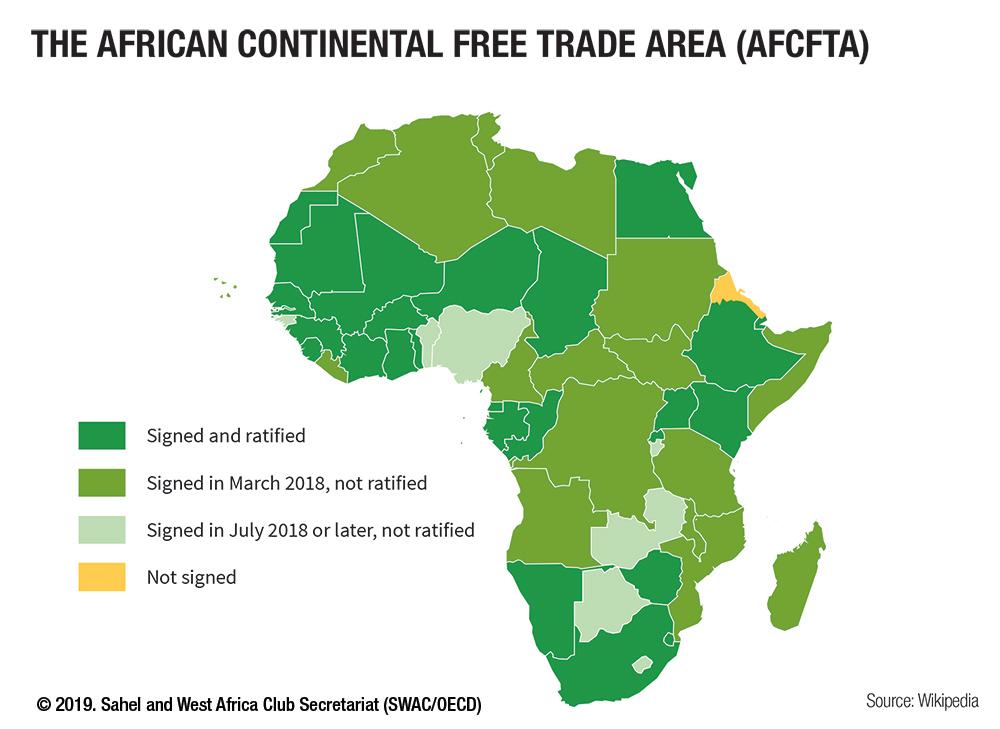

Despite the seemingly positive effects of globalisation, would Africa really benefit from it? It is important to recognize that while globalisation, trade and international integration tend to increase the overall economical income, the distribution of the income may be very uneven. Some workers, particularly those in industries that are less able to compete and whose skills have become less relevant can find it difficult to adjust. While trade is almost always advantageous for a country’s economy, not everyone within that economy will be benefiting from it. This is especially the case where there are no policies to cushion the negative consequences of trade and to ease adjustment. Low-income workers in emerging markets, for example, may find it more difficult to adapt given the less financial resources available to deal with adverse economic shocks. The adjustment process tends to erode gains from trade. Africa needs to learn to diversify its exports, in order to make a safer and more stable economy and organize a new integration into the global economy, so to attract new investments. Trade blocs such as the African Continental Free Trade Area (AFCFTA) can boost trade within Africa, its goal is to establish a single market for goods and services across 54 countries, allowing the free movement of business travelers and investments, and create a continental customs union to streamline trade - and attract long-term investment. Intra-Africa trade has been historically low. Intra-African exports were 16.6% of total exports in 2017, compared with 68% in Europe and 59% in Asia, pointing to untapped potential. It will be a challenge to make way for easy and quick facilitation of people and goods in Africa because there is so much fragmentation, with economies at widely varying stages of development. While the reality is there will most likely be winners and losers, the role of the African Union will be to ensure shared prosperity on the continent, creating supportive policies, eliminating monopolies, and stamping out uncompetitive behaviour. For Africa, globalisation would be a process that creates winners and losers, and thus leads to greater inequality. Africa is not yet ready to take on globalisation’s negative effects, much less benefit from the profits of globalisation.

Africa should aim to ensure economic security, establishing the right framework for economic activity that addresses the sense of uncertainty that still plagues economic decisionmaking in most of Africa. The direction and orientation of future policy must be firm. This requires the creation of a strong national capacity for policy design, operation and monitoring. National authorities should spare no efforts to tackle corruption and inefficiency, and to enhance accountability in government, reducing the amounts of rent from other countries, as this would set Africa further back on its road to economic development. Finally, the African governments should seek the advice and support from the civil society.

There are many challenges for Africa on the road of globalisation to development, and the hurdles can only be overcome if the regional governments in Africa evolve to become effective, meanwhile providing mutual support for others in their efforts to reform. This can also be a backstop to counter the negative effects of globalisation. Africa should seek to push through reforms in the areas of the legal and regulatory frameworks, financial sector reformation, labour and investment improvement, and exchange and trade liberalisation that seek to reach international standards as quickly as possible. 23