Co-Editors-in-Chief

Aaliyah Crawford & Leighetta Kim

Creative Director

Nesreen Galal

Head Writer

Hashmita Alimchandani

Managing Editor

Yolanda Smith-Hanson

English Editors

Christina Marando, Ali Byers ,Charlotte Perreault

French Editor

Agathe Nolla

Digital Content Manager

Alana Batten

Event Coordinators

Amara Balk, Sophie Semeniuk

Finance Coordinator

Liza Makarova

Copy Editors

Hannah Ferguson, Agathe Leroy, Ashley Rose, Merveille-Lovinsky, Xavi Meza-Wong, Hannah Silver Contributors

Lune Wagner, Renata Critton-Papp , Isabella Carver, BeNjamyn Upshaw-Ru ner

Yiara Magazine is an online and print publication that discusses feminism in the context of art through visual and written work. We are a student-run magazine that aims to showcase students’ work as well as promote critical thinking and feminist dialogue. Our project emphasizes the collaboration of university students from various disciplines across Montreal. In doing so, Yiara provides a space for the city’s undergraduate community to share their ideas and engage with a wide array of students, professors, established artists, and art institutions. Each year we publish written and visual work on our website, host various events, plan an annual vernissage, and release a yearly print edition. In cultivating a space for feminist dialogue within the field of art, we aim to raise questions on the art historical canon, study feminist representation, explore ideas of gender, race, sexuality, class, ability/disability, sustainability, and the self.

Land of Acknowledgement

Yiara Magazine publishes on stolen Kanien’kehá:ka territory. The Kanien’keha:ka are the keepers of the Eastern Door of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. Montreal, called Tio’tia:ke in the language of the Kanien’kehá:ka, has been a place of community for generations. It is not enough to just acknowledge the keepers of this land. As an organization committed to social justice, Yiara must also actively resist colonialism in the many forms it takes.

2

special thanks to....

3

4

04 Yiara Magazine April Avril 2016 Issue Volume 04 An undergraduate feminist art and art history publication. Une revue étudiante d'art féministe et d'histoire de l'art. Yiara Magazine An undergraduate feminist art and art history publication Une revue étudiante d’art féministe et d’histoire de l’art Issue 05 Volume 05 YIARA 05 April 2017 Avril 2017 An undergraduate feminist art and art history publication Une revue d’art étudiante féministe et d’histoire de l’art Yiara Magazine April Avril Issue Volume 07 2019 Vol. 08 2020 Yiara Magazine Volume 08 2020

Yiara Magazine over the years.....

In this Issue...

12 16 18 20

26 28

32

In These Eyes Lie an Endless Ocean

Quang Hai Nguyen

Hey, Don’t you know?

Thai Hwang Judiesch

Tough Love

Sarah Demers

Reclamation and Belonging in Mixed Indigeneity

Drinalba Shérif

Nutrients Series

Dan Young

Encounter in Sharee

Naimah Amin

Becoming not to Be: Identity and Place in Manuel Mathieu’s Bennett

Kari Valmestad / Kioni Sasaki-Picou

38 42 44 Paloma

54 56 58 60

Submergée

Nathalie Sereda-Bazinet

Ana Teodorescu

Diasporic Haunted Memory and the Resurgence of Korean Shamanism Online

Thai Hwang Judiesch

Karina

Issy Tessier

Recipe for Failure

Tiana Atherton

Jardin Secret

Marianne Lefebvre-Campbell

The Reception History of Barbara Loden’s Wanda (1970): Reframing the Politics of Representation, “Use,” and Slippery Historical Objects

Hannah Ferguson

Editor’s Note

As Yiara celebrates its tenth anniversary, we found it to be a crucial moment for us to reflect on the legacy of the magazine. Looking back at the history of Yiara, this publication first began as a class project and has since grown to sta over 20 students across Montreal universities. Much of the work we did this year as Volume 10 Editors-in-Chief was about honoring that legacy by investing time and resources into solidifying our institutional framework, improving our sustainability and archiving our institutional knowledge in the hopes that Yiara will celebrate another decade of publication. We alligned our mandate to be consistent with contemporary feminist and decolonial discourse. We integrated this into discussions amongst the Yiara team, and strove to prioritize publishing work that encapsulates this refreshed vision. We worked to further integrate these values by updating the language used in our constitution to more accurately reflect the diversity and breadth of our team, our values and our vision for the future. Volume 10 reflects this continued push from Yiara to carve out a path consistent with contemporary discourse.

As a feminist magazine, the topic of one’s identity is consistently woven into our publications. Yet it is unsurprising that whilst surviving a global pandemic, tensions surrounding identity, the self and our surroundings began to exacerbate as we all experienced some form of isolation, uncertainty and loss. In Quang Hai Nguyen’s In these eyes lie an endless ocean we can see the complexities of identity unfold as they explore what it means to be part of the Vietnamese Diaspora. In Nathalie SeredaBazinet’s Submergée, the relationship between one’s self and their surroundings during the pandemic is fleshed out through a series of prints.

In Reclamation and Belonging in Mixed Indigeneity, Drinalba Shérifi further deconstructs the ways in which identity and heritage is employed by Indigenous artists.

These last three years have been challenging and di cult. We missed our Volume 8 show, moved online exclusively for Volume 9, and this year has been no di erent. The pandemic has continued to loom over our heads and influence the production of our magazine as we entered the tenth volume of Yiara. Many of us experienced great losses this year far beyond the scope of the publication. We lost family members and loved ones, and bore the weight of these experiences on shoulders already worn down by the last two years of isolation and fear. Burnout amongst our team was and is no joking matter. At no fault to anyone, we could tell that with each year we continued into the pandemic, the lower and lower everyone’s capacities fell. So we, as CoEditors-in-Chief, decided to adjust and reduce our normal output for the year. All of this to say that the publication of the tenth volume is a small miracle. We are forever thankful to everyone who helped get us here. To our amazing team who made this possible despite facing so many obstacles. To our contributors who filled each and every page of this issue with their outstanding creativity and beautiful work. To our support systems for helping us along the way. And lastly, to the past nine years of Yiara; to the students who furthered the project, kept it alive and to the decade of team members who’ve worked together to sustain and expand it.

Yours truly,

7

Time Capsule

In These Eyes

9

Lie an Endless Ocean

10

How can the function of art extend beyond its aesthetic intentions? Quang Hai Nguyen approaches photography as a means to create communion and to better understand what it means to be Vietnamese. Nguyen’s ongoing photography project, In These Eyes Lie an Endless Ocean, creates a channel in which exchange and multi-directional understanding have the opportunity to flourish. In the artist’s words:

Nguyen also wants to explore the unease of creating self-definition as someone who is part of a diasporic community, while highlighting the unifying nature of shared feelings. The artist wants to create safe spaces through photography. “A space to remind Vietnamese people that it’s okay to feel a little lost. Photography can be a bridge for these experiences and feelings.”

Driven originally by a sense of loneliness and alienation, Nguyen describes their work as a stand-in for a family dinner. The intention behind In These Eyes Lie an Endless Ocean is to facilitate a kind of gathering to help lighten the burden of heavy feelings by emphasizing, sharing, and embracing vulnerability. Nguyen’s process begins with an exchange where they ask subjects how they might define the Vietnamese experience.

In These Eyes Lie an Endless Ocean

11

Quang Hai Nguyen

I’m trying to find new ways of talking about the Vietnamese experience. Vietnam is often defined only by its traumatic events, through a Western colonial gaze. I don’t want a whole generation to be defined by these traumas.

Part of this involves remembering, extending memories forward, and augmenting the present so as to create spaces for future memories that are not sullied by the lens of trauma, but instead illuminated by exchange. The resulting photographs are ultimately a collaboration, and thus relate back to the original ethos of the project – one of creating a kind of gathering and togetherness.

Nguyen uses photography as an intentional act of countering narratives of trauma. The artist has created a contemplative body of work that presents its subjects with opportunities to enter spaces in which they may ask questions, express ambivalence, and ultimately embrace communion.

12

Hey, Don’t You Know?

Thai Hwang Judiesch

13

Hey, don’t you know?

It’s already the end of the world. I’ll meet you right here, In the future, and we can talk about, What our parents’ parents did wrong And how we will do better.

For a moment we can untangle ourselves into thin silver lines, And make sense of this point (that is di erent from other points) And find safety in that knowing, Or perhaps we can just feel held by all the sticky webs, And sink ourselves under the thin covers of time, wondering if we tug just so That some[where] our parents’ parents’ parents might feel it.

Here , at the end of the world, We can imagine history happened di erently, Or that umber possibilities that have long since been discarded, Or dumped in riverways that lead to the ocean, Can be rediscovered Hanging on a fin of a fish, Or around the neck of a turtle, Or tangled up in seaweed. We can imagine that this was where our soul last left o , And pick it back up again.

Here , at the end of the world, We can finally mourn and wail deep indigo And allow the ghosts crowding our houses to be put to rest, Or, if they wish, to roam freely Between ether and orange sky. Where clouds that look like willow trees Chatter on di erent time—lines

And remember di erent memories. We can hold their phantom pain, And cry about what-could-have-been-but-never-was.

Here , at the end of the world, We can dip our fingers into honey And gasp in between this realm of pleasure and pain that helps us feel the future. We can dream about freedom, wake up again, And remember that we are alive. That some[where] between here and there Exists eternity and it is ours if we want it.

Hey, don’t you know?

It’s already the end of the world.

14

Sarah Demers’ Tough Love was inspired by research done by the artist on quilt making and the sculptural potential of the medium, ultimately culminating in a reimagining of quilted garments worn under medieval armour. Demers’ work centres bell hooks’ concept of a “love ethic”, from her book All About Love – an idea that stresses the work of enacted, mutual care. The decision to create armour in the style of a decorative quilt is the artist’s way of putting certain binaries into question. As also discussed by hooks, these binaries include supposed opposition of certain feminine and masculine tendencies and expressions: philosophies of care versus those of domination, two principles that have historically stood in conflict with one another.

Tough Love works to combine these disparate elements, creating a visual juxtaposition that questions the societal segmenting of love and protection, and ultimately asks if both can exist together. Demers hand sewed each triangle used in her artwork, favouring a softer, pastel colour palette. Her labour reflects the ethos of a “love ethic”, one that is implicit in the craft of quilt making. The resulting work is a poetic take on questions that challenge societal binaries–questions central to forming new ways of being that celebrate and honour the tenets of protection, care, and love.

15

“Quilts are an act of love”, says Demers, emphasizing the roles of the object as both reflections of and extensions to notions of love, care, protection, and labour. In Demers’ work, armour represents a rejection of these qualities, “[standing] in for the concept of the “ethic of domination” …where qualities such as sensitivity, openness to others, and a caring disposition are at best dismissed or at worst heavily punished, especially in men.”1

Tough Love

Sarah Demers

2020 Cotton, cotton batting and aluminum wire

Approx. 17’’ x 22’’

2020 Cotton, cotton batting and aluminum wire

Approx. 17’’ x 22’’

Reclamation and Belonging in Mixed Indigeneity

To a rm oneself is to remedy others’ misconceptions. For this reason, the declaration of belonging to an Indigenous identity is an essential expression of inner being for Indigenous artists of mixed racial ancestry. A rmation of their cultural background guides them in the creation of artworks narrating a story of discovery. For many artists, this endeavour has its challenges, as the story of the Indigenous population has been linked with the colonial enterprise of cultural erasure. Artistic endeavours made by mixed Indigenous artists thus tackle notions of reconnection and reclamation as forms of self-healing and self-expression. The incorporation of gendered lived experiences of Indigeneity emerging from cases of sex discrimination supports this a rmation, along with the practice of digital media interaction as a tool of belonging with Indigenous knowledge. Alternatively, the modern reconceptualization of Indigenous kinship aids in cultural connectivity with an ancestral past.

The reclamation of Indigeneity in contemporary art can be perceived through the incorporation of dialogues pertaining to sex discrimination and gendered experiences of Indigenous culture. The use of a feminist perspective uncovers the generational impact of communal erasure for Indigenous women and highlights the artistic endeavour of First Nations artists, such as Caroline Monnet, who bring forth ideas of belonging and reconnection. Sex discrimination refers to the unequal treatment made unto an individual or a group solely based on their sex. Indigenous women experienced firsthand the discriminatory treatment enacted in Canada’s legislation as they were unfavourably recognized in community membership.

In Canada, the Indian Act drastically limited First Nations women in gaining “Indian” status. At first, the assimilation project of the Act stipulated that Indigenous women were to lose their membership amongst their community if they married white men. However, this did not apply to Indigenous men, who, while keeping their community status, could grant the latter to white women and their children.1

According to Pam Palmater, this form of sex discrimination was advantageous for Canadian settlers, as it permitted legislative extinction through the expatriation of Indigenous women.2 As colonial enterprises critically demanded the extermination of Indigenous presence, the gendered imposition of the Indian act supported the erasure of First Nations groups through women’s disconnection from their communities.3 Moreover, Palmater a rms that by granting non-Indigenous wives and children Indian status, cultural assimilation was reinforced as white individuals gained access to their lands.4 Sex discrimination thus became a political tool that strengthened the racialized perception of Indigenous presence and caused the cultural erasure of many Indigenous individuals who, through this law, lost touch with their land, culture, and language. On the report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, conclusions about Canada’s treatment of First Nations note the ongoing violence and prejudice caused by the country’s actions: Canada has displayed a continuous policy, with shifting expressed motives but an ultimately steady intention, to destroy Indigenous peoples physically, biologically, and as social units, thereby fulfilling the required specific element.5

17

The MMIWG stipulates that through measures of erasure, such as sex discrimination in the Indian Act, Indigenous women are at increased risk of physical and emotional abuse along with sexual assault.6 By having policies that separate individuals assiged female at birth from their communities, later reconnection with Indigenous lands becomes far more di cult for Indigenous women and their descendants, as they su er forced relocation and are left with a feeling of being unwanted in their community.7

As a counteraction, we can link gendered experiences of Indigeneity through examining Caroline Monnet’s History Shall Speak for Itself, which challenges preconceived notions of Indigenous female representation and includes a visual experience of multi-cultural integration. As the daughter of an Algonquian mother in the Kitigan Zibi reserve and a Breton father, Monnet often integrates frameworks of both cultural backgrounds into her practice.8 In her art, bicultural understanding of the self is bound with visual homogeneity, as she presents both realities under a singular and personal lens. In History Shall Speak for Itself, photographs are shown of Indigenous women such as filmmaker Alanis Obomsawin, Quebecois actress Dominique Pétin, costume designer Swaneige Bertrand, film student Catherine Boivin, the artist herself, and her sister.9 The artist presents the women’s portrait beneath black and white archival images of Indigenous life. As the black and white pictures superpose the women’s photoshoot, their faces remain unobscured by the collage, emphasizing their

Drinalba Shérif

presence in the monumental artwork.

The use of archives in this work intentionally references Western methods of documenting Indigenous women and their domestic tasks.10 As ethnographic studies on Indigenous people often rendered the subjects with little to no interiority or engagement, Monnet

explores the blending of both European aesthetics and Indigenous representation to form prominence in the female subjects’ rendition. Her work reflects female collaboration and unification, which demonstrates a will to reinforce the integration of women into discourses about Indigeneity. By depicting a strong female presence through the multiplicity of female subjects and their solemn postures, ideas of resistance and resilience emanate from the picture. The artist invites its viewers to think about their stories as a way of discussing the treatment of Indigenous women. The idea

18

of being seen and heard is materialized in this work to bring forward demands for agency and recognition. In this sense, reclamation by Indigenous artists of mixed ancestry can be perceived through cultural retrieval. Monnet recovers Western and Indigenous visuals to proclaim her bicultural identity. This endeavour aids in the inclusion of newer gendered experiences for Indigenous reconnection.

The need for reclamation also emerges in the application of digital art and new media by mixed Indigenous artists who seek connection with past knowledge and beliefs. In her work about Indigenous art in the hyperpresent, Suzanne Newman Fricke defines the concept of Indigenous futurism as an element that o ers “a new vision” of the world from a Native American perspective—“ [...] a forum to address di cult topics, such as: the long impact of conquest, colonialism, and imperialism; ideas about the frontier and Manifest Destiny; about the role of women within a community; and about the perception of time.”11 She says, “[…] the term suggests a time outside of the timeline we are in. It could even refer to the past, to a re-envisioning of what has already happened.”12

Fricke explains that Indigenous futurism is enacted through the influence of Indigenous writers of science fiction who conceptualize worlds outside of colonial influences, homeland and resource loss, and unethical treatment of Indigenous people.13 Conceptions of cosmology and traditional understanding of the universe are elements retold through the utilization of technology as a modern way of accessing knowledge.

For instance, Sonny Assu’s work They’re Coming! Quick! I have a better hiding place for you. Dorvan V, you’ll love it (fig.1) reimagines past colonial depictions of Indigenous living by adding to the work elements of the sciencefiction imaginary. The artist utilizes a scan from an A. Y. Jackson painting, which depicts a small village made of multiple cabins, and modifies it

through digital intervention, adding a UFO-type structure in the sky. In Assu’s work, we see a group of people in the middle of the foreground, targeted by the alien structure cloistering them inside circular beams of green and purple rays. Rather than reading Assu’s work as depicting aggression (through the abduction of villagers), Fricke suggests it is an act of salvation, moving the First Nations to safety.14 The Indigenous subjects are not rendered as victims, but rather as protected individuals. “There is this narrative in sci-fi movies, TV, and comics where an alien invasion is happening, and how we, mostly white North America, will step up and say, ‘we’re going to kick out these aliens.’ It becomes an ironic dynamic, especially when you take a look at how what we know now of North America was colonized by an alien invasion.”, says the artist.15

This narrative invites viewers to perceive the depicted people as fleeing colonial attacks and violence. Moreover, the incorporation of sci-fi elements into a Canadian landscape painting o ers a contemporary and Indigenous response to colonial rendition of First Nations’ land. Fricke writes,

[…] Assu’s paintings give way for the forms to be a stand-alone entity unto themselves that interact with the landscapes and environments that are equally so ever changing by many hands through generations.16

19

The alien invasion is the story of North America’s colonial enterprise by Westerners. Indigenous individuals represent, in this piece, those who seek shelter from the occupation in their territory.

By adding an abstract form mimicking alien occupation, the artist transforms the land to incorporate notions of deliverance from past trauma, where the future, shown here through digital manipulation, holds betterment and liberation for Indigenous people. This ties in with the concept of reclamation as Indigenous artists from di erent cultural backgrounds use technology to retrieve past knowledge and modify its contemporary reception. The practice encourages immersion into an Indigenous narrative and contributes to a new form of self-fashioning and artistic production for mixed artists. Indigenous futurism thus permits the digital reconceptualization of ancestry and o ers a gateway into the latter’s knowledge and accessibility.

Artist Megan Feheley’s digital beadwork also conceptualizes traditional making and the modern practice of digital rendering. Their numeric work, named Wâniska (fig. 2), showcases an intricate pattern of beadwork, where traditional shapes are put into a computerized canvas. The dark background of the image contrasts the bright colours of

the beads, making them the primary object of visualization. Moreover, viewers are confronted with an image that holds visual energy—the artist’s three-dimensional creation invites us to follow the bead’s dynamic motions. Feheley incorporates the idea of entanglement into their artistic practice,creating shapes inspired by their Cree culture, whilst mixing these Indigenous motifs with other forms of artistic mediums (such as digital media). In their work, being tangled up in one’s own body allows for an analysis of the self in regards to identity and gender as a two-spirited person. Alternatively, because of the limits to learning traditional languages, new forms of knowledge are revised into a modern framework. By incorporating digital art, contemporary Indigenous artists can combine modern visual culture with Indigenous knowledge, demonstrating the possibility for new understandings of reclamation.

Self-representation and reclamation in contemporary Indigenous art can be explored through the modern reconceptualization of kinship and blood belonging. Indigenous people have long su ered the damages of the blood quantum and social a liation through biological markers of blood. In Bonita Lawrence’ study of mixed

Indigenous identity, she brings forward the stereotypical notion of the “vanishing Indian”;

[…] The apparent consensus from all quarters within the dominant society that “real” Indians have vanished (or that the few that exist must manifest absolute authenticity—on white terms—to be believable as Indians) functions as a constant discipline on urban mixed-bloods, continuously proclaiming to them that urban mixed-blood Indigeneity is meaningless and that the Indianness of their families has been irrevocably lost.17

The idea that Indigenous people are undergoing extinction reveals intergenerational prejudices preserved in modern times. By abiding by the “vanishing Indian” narrative, white society perpetuates colonial understandings of Indigenous people as extended communities that possess a

20

singular lineage—in this perspective, mixed Indigenous individuals do not acquire “Indian” recognition, as the idea of a multi-biological a liation goes against their essentialist judgments on “real” Indigeneity;

The problem for [Indigenous people] is less a matter of not belonging anywhere, than living in a polarized society where whiteness and Nativeness are not admitted as existing in the same person. 18

She explains here that for bicultural people, the undermining of their Indigenous identity taints and diminishes the latter because of the perception that they are not Indigenous enough.19

In discussion with Eve Tuck in the Henceforward podcast, Kim Tallbear advances the idea that in our society today, cultural knowledge and genetics are elements closely bound together, hence the reason we need to have a more fluid perception of Indigeneity.20 Tallbear explains that Indigenous people have overcome many changes to their life experiences with the colonial project of genocide and assimilation, which is why we need to think about Indigenous kin groups as being a

dynamic population that reactualizes its cultural a rmation.21

By looking at Amanda Amour-Lynx’s work Salmon Run II (Figure 3), we can perceive the intention of bringing forth reconnection with Indigenous lived experience. The artist presents a canvas that possesses no geometrical boundaries to it; the wooden panel is submerged in a thick layer of acrylic that expands beyond the supporting medium. Moreover, the combination of acrylic, beads, sunstone and fish vertebra showcases an elaborate formal work on textures. The artist uses a mix of pastel colours; we can perceive tones of greys and blues that are mostly in the background, while more vibrant colours such as pinks, oranges, and purples overshadow the preliminary colours. Amour-Lynx encapsulates in her work notions of recuperation.Salmon Run II not only imitates the natural habitat of wildlife salmon, but it also presents itself as a map. The idea of finding one’s pathway through a map resonates with the claim for reconnection amongst Indigenous communities as it asserts the promise of a cultural retrieval. It symbolizes an ancestral conception of

21

the natural world uncovered by the artist to form a spiritual reunification.

Mixed Indigeneity manifested itself in Indigenous contemporary art as a way of demonstrating reclamation and self-determination. Indigenous artists approach notions of reconnection as forms of self-healing to reintegrate their past. It is by engaging with Indigenous lived experiences that we can suppress intergenerational prejudices and support multicultural individuals in their paths to redefining Indigenous identity. By incorporating gendered lived experiences of Indigeneity and the practice of interaction with digital media as a tool of belonging for Indigenous knowledge, communities can achieve a modern re-conceptualization of Indigenous kinship in art.

22

The idea of finding one’s pathway through a map resonates with the claim for reconnection amongst Indigenous communities as it asserts the promise of a cultural retrieval.

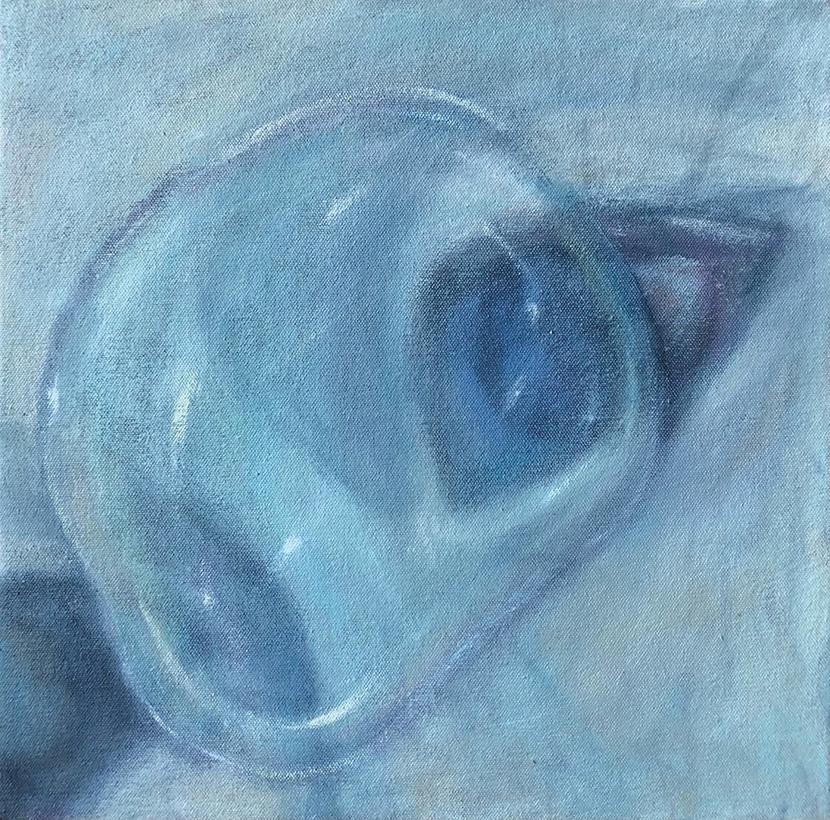

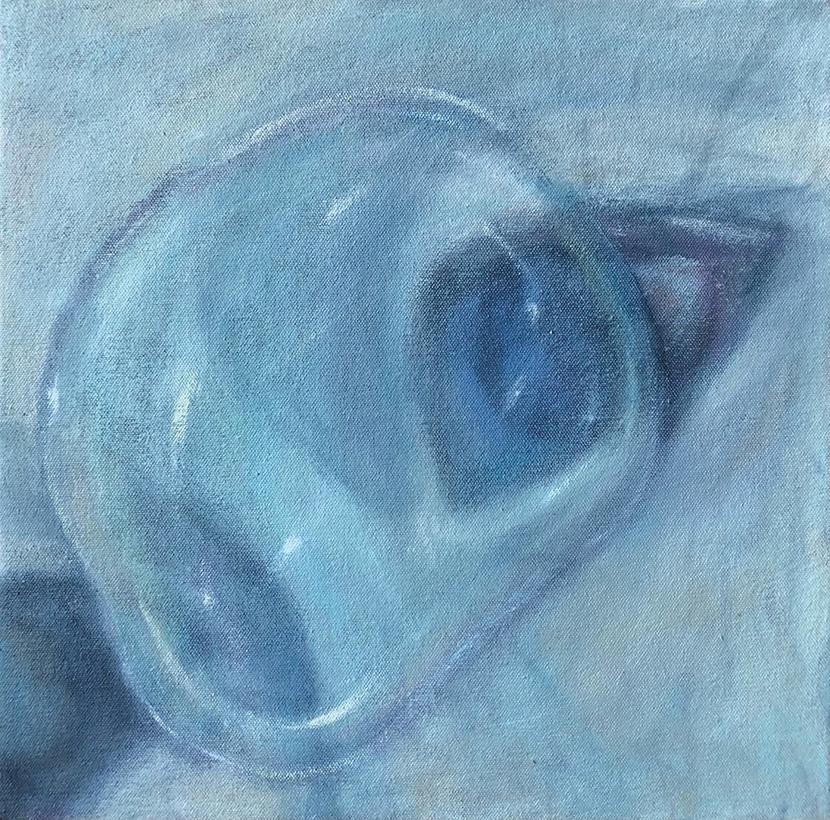

In Nutrients Series, Dan Yang investigates liminal spaces that are beyond language. These painted representations combine seemingly recognizable visual elements, like various parts of bodies, with surreal projections that come from the artist’s imagination. Yang’s paintings depict fragmented parts of the body paired with unlikely objects and phenomena. The uncanny images are bathed in striking shades of blue – creating a spacious sense of ambiguity and melancholy.

Nutrients Series presents works that evoke a sense of mystery and alienation from the body. Things are left up to interpretation, but Yang’s series is chiefly concerned with bodily experiences of the world. Yang’s paintings further evoke feelings of alienation that are a product of living within a seemingly unfamiliar country and culture. Yang shares, “[t]he paintings speak to my own experience because I’m here in Canada, where things are new to me and I’ve experienced loneliness here as a result. They speak to my subjectivity. Painting isn’t necessarily a healing process, but it’s a way for me to deal with what I’m feeling”.

Yang has a background in film studies, and this has influenced her painted works. She paints straight onto canvas by omitting the use of gesso, and this gives the paintings a distinctly filmic quality that is reminiscent of pictures shot on film.

Yang’s paintings simultaneously reflect a process of observation and self-contemplation that echo certain experiences of the artist. At the same time, they maintain enough space so that anyone engaging with the work may be able to recognize and relate to feelings of remoteness and disconnection from the body.

Dan Young

23

24

Nutrient Series

Daughter, 24

2021

Acrylic on canvas, 30x24”

photo credit: Julie Ciot

Daughter, 24

2021

Acrylic on canvas, 30x24”

photo credit: Julie Ciot

Mother, 21 2021

Acrylic on canvas, 24x18”

photo credit: Julie Ciot

Mother, 21 2021

Acrylic on canvas, 24x18”

photo credit: Julie Ciot

Encounter in Sharee (2021) Naimah Amin

In Encounter in Sharee (2021), Naimah Amin presents us with the sharee - a shared cultural object that links two paintings to one another. The two paintings depict a mother and daughter, for which Amin used old family photographs as visual references. Amin emphasizes the subjectivity of her distinct lens, one that centres imagination, interpretation, and ultimately unique representations. Her works do not necessarily seek to create narratives about identity, despite the use of the personal archive as one point of reference; “I have a fascination with old photographs…but my intent in using them doesn’t necessarily align with nostalgia or longing. I use them as a lens to understand other things.”

Even within spaces of contemporary visual culture, racialized artists are not always given the credit of being able to look beyond themselves or their own cultural identities. The self, already a charged entity that must navigate spaces that are predominantly white, becomes a metaphorical ball and chain of artistic freedom and expression. Artworks made by racialized individuals can sometimes be pigeonholed into shapes that are easily recognizable by the white majority. To subvert these expectations, Amin uses imagination as a means to ground her paintings,

“With imagination, I’m filling in the gaps I have about my parents’ culture and extending their memories. I use it as a tool to signify the hybridity of cultural identity, but also to emphasize how identity is in states of constant evolution and transformation as it lives on in the diaspora.”

In Encounter in Sharee, Amin asserts artistic agency, keeping in mind her conceptual ambitions, which challenge hegemonic narratives of how and what racialized artists are allowed to explore in their works. “I chose to present these two paintings together because, in my head, they show that memories can be interpreted in di erent ways. One is a recent memory of my sister, and what you see on the canvas is the impression of a memory I hold close to my heart. Whereas, in the painting of my mother, I allowed myself to deviate from what I saw in the picture. It isn’t based on my memory. The painting is a standin for how oral histories are absorbed by diasporic individuals, and how they live on through us.”

27

I chose to present these two paintings together because, in my head, they show that memories can be interpreted in di erent ways. One is a recent memory of my sister, and what you see on the canvas is the impression of a memory I hold close to my heart.

https://narmassociation.org/manuel-mathieu-world-discovered-under-other-skies/.

29

Figure

1: Manuel Matthieu, Bennett , 2018, acrylic, tape, charcoal, chalk on canvas, 152 x 137 cm.

Collection of Adriana Bjäringer,

What does it mean to search for a feeling — not necessarily an understanding — of one’s identity when rooted amid divergent landscapes? What can this embodiment look like in a state such as Haiti, where identities are pluralistic, complex, and dismissed?

ly conceptual, his paintings are driven by a narrative, usually derived or inspired by Haitian history, where intimate memories and feelings are spawned. His mixed-media painting Bennett (2018) (Fig. 1) calls attention to Haiti’s oppressive Duvalier eras, where Mathieu found family members on both sides of two murderous dictatorships. Having painted this work after su ering serious injuries in a car accident, Mathieu’s historical examinations have since taken on embodied implications wherein hereditary traumas and memory incarnate into physical expressions.

In this visual investigation, we explore Mathieu’s attempts at self-identification through his intimate explorations of uncertainty towards identity and place as expressed in his history-centric work. Using Bennett as a pictorial guide, we delve into the hindering journey of self-discovery and the

by Kari Valmestad / Kioni Sasaki-Picou

Montreal-based artist Manuel Mathieu explores these questions in his expansive hallucinatory paintings that interweave themes of nationhood, diaspora, identity, and trauma. Immigrating from Haiti to Canada at age nineteen to live with his grandmother in Montreal, Quebec, Mathieu has since emerged as a prominent Canadian artist with nine solo shows and over a dozen group exhibitions under his belt. His style is recognizable: drawing from Abstract Expression (taking specific inspiration from Cly ord Still)1 Mathieu’s colourful and formless compositions build up non-descriptive worlds in which ambiguous figures dwell in indistinct and often hidden spaces. Typical-

never-ending flux of becoming. Along this examination, Mathieu’s work will be placed into a context of Black Canadian art history, an up-and-coming field that centers Black Canadian artists and artwork historically omitted or devalued in canonical Canadian art history.2

Unlike in most of Mathieu’s works where (if there is a figure) they remain abstractly hidden or disjointed, the figure in Bennett is identifiable. Michèle Bennett on her wedding day to Haitian president (1971-1986) Jean-Claude Duvalier.

Mathieu reproduces the famed 1980 candid shot of Bennett in her white pu ed-sleeved gown and halo-esque hairpiece (Fig. 2). Except in his version, a fluid medley of purple, blue and chartreuse-hued washes mimic her iconic bridal accessory. In

an almost fluoroscopic fashion, Mathieu sca olds Bennett’s head and shoulders with wet bonelike marks while larger areas of colour pool at her face and scalp. Mathieu’s rendition is hauntingly luminescent, both in colour and subject.

The significance behind Michèle Bennett’s photo is multi-layered. The image calls attention to her and Jean-Claude Duvalier’s infamous marriage. Costing approximately 2 million dollars, their union was considered to be Haiti’s “wedding of the century,”3 hyper-publicized and surveyed all around the world. In addition to the wedding’s extravagance, the event garnered incredible media attention due to its sheer political nature. Bennett was the daughter of an influential Haitian family, part of the country’s bi-racial bourgeoisie. Viewed as immoral, anti-traditionalists and in opposition to the

Becoming not to Be: Identity and Place in Manuel Mathieu’s Bennett

30

Duvalieristes or Noiristes (Haiti’s Black political elite), this lighter-skinned class that Bennett belonged to had previously been the rivalry to Duvalier’s father, François Duvalier (Papa Doc)4 during his presidential reign (1957-1971). Bennett, moreover, was a divorcee and interpreted by the wide majority of Haitians to be “too ambitious, too promiscuous, too smart, and too liberal,” making her an undesirable state bride.5 Duvalier’s mother, grandmother, and associates echoed these sentiments as they all opposed the marriage, viewing it as a threat to the Duvalier regimes.6 Bennett and Duvalier’s union thus shocked and angered the Haitian public, contributing to what some scholars have deemed the ultimate demise of the Duvalier dictatorship.7 The couple’s later corruption and money embezzlement, which resulted in their eventual exile from Haiti, only added to this disdain for Bennett as a national figure.

In Mathieu’s painting, Bennett embodies many representations: she encapsulates the nation’s colourism and class;8 she symbolizes the state’s late twentieth-century wealth, power, and extortion; and, building o this last representation, she is associated with the horrific atrocities committed by both François and Jean-Claude Duvalier. Between the two men, tens of thousands of Haitians lost their lives in political

conflicts, governmental massacres, and calculated killings.9 Mathieu has direct ties to these presidential terrors, having had a grandfather on one side of his family serve as a colonel in François Duvalier’s military and members of his family’s other side killed while fighting against the government.10 Despite having only been an infant when Jean-Claude Duvalier was overthrown (1986), the Duvalier eras are vividly present in Mathieu’s life as depicted in Bennett and some of his other Haitian-focused work.11 By using the popular culture image of Bennett, Mathieu resituates his family into these complex histories of Haiti’s past—a past already filled with political crisis, state tragedy and human loss. Exposed as a result are the collateral damages and colonial legacies of Haiti, where Mathieu inserts himself, repurposing the narrative.

For Mathieu, locating an identity is not found in distinct and defined places.12 As

repeatedly described in his public interviews, he does not seek out an identity or a definite understanding of his place within a certain time and space. Alternatively, he aims to locate a sense of himself, somewhere.13 It is an uncertainty that he seeks to garner from his work, in a mystical and spiritual approach: “where you are experiencing something and it gets to you... it feels like something is happening. I want to dive into that.”14 Stuart Hall’s theories of cultural identity serve as a productive framework to study Mathieu’s ideological style. Interpreting identity as a “production,” something that is undergoing continuous remodeling and reprogramming, Hall refutes the notion of identity-making as a constant or as being capable of being completed, and instead argues for its ever-evolving properties.15 Hall understands cultural identity as a “matter of becoming as well as being.”16 Identities do

31

“he does not seek out an identity or a definite understanding of his place within a certain time and space”

Figure 2: Unknown photographer, 1980 wedding of Michèle Bennett to Pres. Jean-Claude Duvalier, 1980. Michèle is pictured with Mrs. Simone

Ovide Duvalier. Port-au-Prince, Haiti. https://www.pololifestyles.com/single-post/michele-bennett-duvalier .

not reach a certain point where they become static and absolute. They are in constant motion and flux, subject to the unceasing forces of “history, culture, and power.”17 In the work of Mathieu, we can see how his trajectory for self-discovery is mobile and unfixed as he plays with history and memory. Particularly, in Bennett, Mathieu repurposes history to comment not only on a popularly-remembered moment in Haiti but also to bridge connections between him and his ancestral home. As a result, he explores his unstable or uncertain relations to his identity and place living in the diaspora. Bennett, alongside Mathieu’s other historycentric work, demonstrates an e ort to bring memories and past experiences into the present, paralleling an attempt to “become” rather than solely “be.”

Mathieu’s work has recently considered the bodily trauma he experienced after being involved in two nearly fatal car crashes. Struck by vehicles in London and Montreal in a span of two years, Mathieu su ered a concussion, a broken jaw, black eyes, and lost his vision and memory for a short period.18 Enduring these injuries, Mathieu detailed in a 2019 interview how these physical wounds created new avenues in which to “deal with his mental scars.”19 As Connor Garel notes, Mathieu’s work does not try and sensationalize trauma. Instead “he paints the aftermath, interprets the feeling…[working] in a world of sensations.”20 Mathieu’s physical wounds have become extensions of inherited lingering strains from his country, family, and home. Already inscribed into the body, histories of trauma become accentuated by these physical injuries. Mathieu’s technical practice emphasizes these wounds; his material mark-making, creating thick and thin surfaces of heavy wet paint with agitated and temperate gestures, evokes physicality, embodiment, and

sensuality.21 In Bennett, his storytelling becomes enmeshed within the active movement of painting where historical and bodily scars collide, prompting new spaces of intimate confrontation between him, his past, and the anticipating future. The diaspora has long been conceived as a constantly-changing space—in influx and subject to the forces building up the new world that greets diasporic communities.23 Self-identifying within these convoluted spaces, therefore, becomes complex and sometimes challenging. Josephine Denis writes how “the [diaspora] is constantly rearranging itself; waving o a sea of definitions, descriptions, identifications; becoming[…]a place that built itself up with ideas of purity and separation in the name of “order”.24 Denis concurs that the diaspora can be the simultaneous inhabiting of multiple spaces. Evident in Mathieu’s works is his movement between several territories, where shared histories and embodied traumas linger throughout. Growing up in Haiti where identities are pluralistic and complex due to its saturated colonial and transnational history, Mathieu has had to navigate many di erent geo-spatial plains. His fixation with Haitian temporal moments, therefore, provides some grounding in these shifting places.

Antonio Benítez-Rojo has described the Caribbean as a consistently shifting and self-renewing body, contending that the region is “constantly [regenerating] itself through fragmentation, dislocation, interruption, and instability.”25 BenítezRojo’s structuring of the Caribbean as continuously mutating is constructive in understanding Mathieu’s work. Mathieu’s artistic practice sees him explore chronic familial wounds in memories that are complex, messy, and sometimes indistinguishable. For as he states “I don’t even know what I am

looking at. It then becomes a process of adding which then adds to myself.”26 Continued processes of reworking, rebuilding, and renarrating help construct Mathieu’s place and belonging in the spaces he resides, becoming the architecture of an ever-fluctuating identity.

The requirement to adapt as an immigrant in Canada forms new layers inside Mathieu’s manifestation of identity. In referencing his work, Mathieu has described how he is in a “constant [navigation] between two legacies [Western and Haitian],”27 how he draws from both cultures from vastly di erent geographical domains to create hybrid, fluid interconnecting networks. Being a Haitian immigrant living in Quebec, Mathieu has grown up in a spatial setting that possesses its own compound and racialized systems. Throughout the twentieth-century, immigration from Haiti to Quebec was extraordinarily high, with thousands of Haitians moving to the

French-speaking province, particularly due to the French empirical connections shared between the two states. Unlike citizens from Anglo-speaking provinces or other countries, French-Canadians viewed Haitians as distant family members, linked together “by a special bond” formulated by their inherent association to French civilization e orts.28 Although French-Canadians repeatedly used the familial analogy in reference to Haitian immigrants, Haitians were never seen as “equal” to them. Rather, French-Canadians saw them as “child-like,” “deviant,” and “uncivilized”, in need of the help of the Quebec state.29 For as Sean Mills describes in A Place in the Sun: “Haiti as a parallel society upholding French civilization and Haiti as an infantilized Other… were bound together by the metaphor of the family, linking Quebec’s international presence to its internal social history.”30 Haitian immigration to Quebec has played a large role in the province’s cultural, social, and political history, with

33

“In an almost fluoroscopic fashion, Mathieu sca olds Bennett’s head and shoulders with wet bone-like marks while larger areas of colour pool at her face and scalp. Mathieu’s rendition is hauntingly luminescent, both in colour and subject..“

Haitian-Quebec citizens having become drivers of political and social change within the traditionalist province.31 Despite Mathieu’s rising levels of success, it is crucial to consider the climate surrounding his artistic development that pushes him to live as an outsider, leaving him to navigate through a world he is excluded from yet praised under limited conditions.

Considering the place Mathieu’s work takes up in a contemporary Canadian art historical context is noteworthy. Unfortunately, the state of relevance for African Canadian art history has only recently been deemed to be a more serious academic and scholar-worthy field, with art historian Charmaine Nelson taking the lead in this necessary endeavour. The erasure of Black artists has left multiple gaps within the general timeline of Canadian art history, let alone in a Black Canadian art history. In the case of Mathieu, there is a designation of Haitian identity. Using Bennett as a subject reveals to viewers individual narratives and memories within the Black community. Di erent from the rest, Haiti is the only country in the Caribbean to gain independence against colonial rule by enslaved peoples (1804). As the world’s first Black Republic, Haiti developed a divergent narrative compared to the rest of the Caribbean. Since the country’s sovereignty, Haiti has held a target on its back from colonial powers in addition to falling victim to ignored crises. Like many countries in the Caribbean, Haiti is left to fend for its own livelihood and survival of their narrative. For the future of art and identity, Mathieu fulfills the concerns of urgency for change. His passion and devotion in exploring identity vouch for the revelations of erased

histories. In this case, Black narratives within western landscapes are either underdeveloped or unheard of. Only recently has the awareness of African-Canadian art and identity become one of academic notice. Despite the recent surge in appreciation of African-Canadian art and identities, there still remains a lack of recognition for the distinction between groups within the Black community more generally. With his repertoire, Mathieu subscribes to the recovery of untold expressions and works towards formulating these distinctions. As exemplified in Bennett, Mathieu ventures on a journey of self-discovery, not just for himself but also for his ancestral roots. By taking back agency from a historical narrative of colonial threats, he allows himself the space and creativity to process new ways of self-identification. Through his painterly recollection of Michèle Bennett, a place to heal and move through inherited scars of the past emerges in an endless, lifelong process of becoming. Although recent e orts have started to decolonize the national attempt to maintain ideologies that equate Canadian identity with Whiteness, there is still a long road of rediscovering and re-learning the role and identity of Black Canadian Artists in this country, one that Mathieu is currently paving.

34

Although recent e orts have started to decolonize the national attempt to maintain ideologies that equate Canadian identity with Whiteness, there is still a long road of rediscovering and relearning the role and identity of Black Canadian Artists in this country, one that Mathieu is currently paving.

35

Nathalie Sereda-Bazinet

36

Submergée

Submergée by Nathalie SeredaBazinet is a project that was conceptualized in the midst of lockdowns during the earlier days of the pandemic. Suddenly confined to her domestic space, SeredaBazinet found herself unable to find refuge from the labour of daily life.

37

“When we were all stuck at home, I felt like I was fusing with my furniture. I have a family, so I’d end up cleaning up after everyone. Even though everyone was doing their share of housework, there was always something more to do.”

Amidst the di culty of having to maintain domiciliary stability, Sereda-Bazinet began to find inspiration in the piles of stu around her home. Inspired by the works of other contemporary feminist artists such as Mierle Landerman Ukeles (Maintenance Work, ca. 1969), Sereda-Bazinet began to reframe her domestic tasks as an extension of her artistic practice. In addition to this, she found herself drawn to the artistic and intimate gestures of archival work, which functioned as a nice compliment to her ongoing drawing and printmaking practice. Printmaking allowed the artist to create multiple iterations of works by layering and rearranging di erent stamps, reminiscent of the piles of things she was encountering in her home.

Submergée presents the distinct point of view of a parent-artist, a framework that is often detached from the archetypal methodology of art-making. In this way, Sereda-Bazinet’s positionality, in addition to her goals as an artist, underscores the inherently political nature of her work. What results is a collection of work that mirrors the artist’s experience of drowning in the necessary grind of day-to-day life, one that doesn’t sco at the possibility of finding rhythm and beauty in the maintenance of disorder.

38

Paloma, Ana Teodorescu

Inspired by a documentary on flamenco dance, Ana Teodorescu turned to her painting and ceramic practice to create the artwork Paloma. As a multidisciplinary artist, Teodorescu applied ceramic techniques in this work, which allowed her to exert more control over the final iteration of Paloma. The result is an artwork that is both vivid and lively through the marriage of formal and symbolic elements.

In this work, Teodorescu depicts flamenco, a Spanish dance tradition, as a channel through which one can look inward and ultimately create a dynamic, outward expression. “At the core of my artistic practice is the idea of fulfilment and finding your own destiny.” In Teodorescu’s work, dance and its subjects represent the ultimate joys of artistic process, where individual expression is equally as imperative as communication and interaction with others. The result is a communion and mediation with one’s internal and external self.

Paloma is a visual collage of these sentiments; a flamenco dancer’s figure is framed by a second, larger portrait. Teodorescu incorporates imagery of a dove to symbolize a kind of purity, and other elements such as contrasting shades of red against black, and a guitar to reference flamenco dance. The dancer represents the culmination of an artistic practice; one that doesn’t illustrate the myriad struggles an artist may have to endure in their path of creation. In addition to wanting to depict a fiery, internal passion, Teodorescu maintains a desire to present an uplifting sense of positivity and hopefulness in her artworks: “[t]here is a beauty in the raw energy of creation. Passion can be stronger than pain.”

39

“[t]here is a beauty in the raw energy of creation. Passion can be stronger than pain.”

40

Diasporic Haunted Memory and the Resurgence of Korean Shamanism Online

I clung to this figure as a symbol of pre-colonial and pre-modernity Korea, a path to retrace loss online. This figure within the Korean diaspora operates both as a remembering of the past and an imagining of an Indigenous future. Online, these diasporic communities are working to trace this figure both in the archive and as a lived reality now, in which past and future are being traced within an Indigenous online sphere as an opposing temporality.

I will explore remembering and hauntings as a diasporic subject, the mudang as a haunting figure, and finally, conclude with mapping out how this phenomenon plays out online.

Colonization is a rupture that attempts to create an impossibility of remembering. The concept of the “phantom limb” articulated by Saidiya Hartman in Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America highlights the nature of this in connection to the violent rupture of slavery. This distinction is important, as I will be focusing

Diasporic remembering, at best, often feels never-good-enough. Locating and retracing what has been lost and severed by the forces of imperialism and colonization is hard to reconcile. How does one attempt to locate and trace irreconcilable loss? How does one fill the haunting gaps and spaces that are left in the history of one’s lineage and ancestry? As a third-generation Korean immigrant, this loss has always held a presence—silences and gaps make remembering patchy. As I got older and attempted to locate my Korean ancestral lineage, I turned to the internet. Online, with the little information I had, I tried to trace and retrace the gaps. The internet has been an integral part of my attempt to flesh out the ghosts of my own lineage. A chance encounter on Tumblr brought me to the figure of the “mudang.” The mudang is a Korean shaman—a spiritual leader within Korea’s Indigenous folk tradition.

primarily on the diaspora of Asian peoples, specifically Korean peoples. This im/migration of Korean people to North America is not placed within the context of slavery. Although there exists a long history of underpaid Asian labour in North America, a notable example being the transcontinental railroad1, this is not comparable to the forced removal and relocation of Africans to North America. However, slavery and anti-Black racism are the fundamental basis for all other forms of racism.

Still, it is important to remember that colonization looks di erent in every place and manifests in a variety of ways. Although I see Hartman’s concept of the phantom limb as a valuable resource to understand the ways colonization e ects memory and remembering, the context that she is speaking from, Black slavery and the middle passage, is important to note. In picking apart the experience of “loss and a liation,” Hartman articulates that memory of Africa and/or an imagined pre-slavery, pre-colonial past operates “in a

manner akin to a phantom limb, in that what is felt is no longer there. It is the sentient recollection of connectedness experienced at the site of rupture where the very consciousness of disconnectedness acts as a mode of testimony and memory.”2

In other words, slavery operates as this ultimate rupture, almost like the severing of a limb. Although that limb is forever detached, there is a phantasmic experience of its presence even if it is no longer there. All access into diasporic memory is thus remembering “not by a way of stimulated wholeness but precisely through the recognition of the amputated body in its amputatedness.”3 This phantom pain is all that is left from the loss—a ghostly haunting of “home.” In this case, Africa becomes this symbolic home space; even when it is impossible to return to pre-colonial Africa, its haunting is felt. It is this very absence that marks this memory.

41

The question of disability within the phantom limb concept is present, and deserves some thought and discussion.

Although I do feel as if this metaphor of phantom pain and severing is a critical part of understanding the way that colonial memory works, the ableism in using an amputation as a metaphor is significant. In the article Metaphorically Speaking: Ableist Metaphors in Feminist Writing, Schalk discusses the way that disability is often used as a metaphor in daily life, and this bleeds in to feminist writings. Schalk specifically cites The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love, in which bell hooks refer to men as “emotional cripples.” Disability as a metaphor codes an inherent “ideology of impairment as a negative form of

embodiment and typically position[s] disability as invariably bad, undesirable, pitiful, painful, and so on.”4 Metaphors often use concrete things to describe something that is abstract, and, in the case of the phantom limb, Hartman is trying to bring to life that which is not tangible—memory and loss.

This can be important, especially within Black studies, because the intangible aspects of racism are rarely given the same weight as material racial grievances. Making this concept concrete and in the body, as it often physically manifests, is a political move for some Black scholars.

Hartman is using the concept of the phantom pain that some amputee people experience to understand loss and memory of Black folks under slavery—not

necessarily within the context of it as a “negative form of embodiment.”5 Moreover, metaphors of amputation in relation to slavery often move beyond just simply a metaphor. As Alice Hall articulates in Literature and Disability, “amputation figures here as a symbol of the loss of identity and agency, but also as a striking reminder of the material history of the physical and psychological violation of colonised black populations.”6 Hartman’s discussion of amputation, slavery and memory, I believe is making a similar move as something more than a metaphor that centres disability as a part of the lived reality of those under slavery. Yet, despite these important di erences, I still think that although phantom pain may help illuminate this concept

of diasporic memory, I choose to articulate it di erently. I propose the concept of “haunting.” This preserves the concept of the phantom and ghostliness, while shifting away from disability as a metaphor. However, “re-membering,” as Hartman articulates it, does necessitate the concept of dismemberment.7 This concept is important to this work, but I will find other ways throughout my essay to articulate this concept—notably through Grace M. Cho’s articulation of “fleshing out the ghost” in Haunting the Korean Diaspora: Shame, Secrecy, and the Forgotten War that will be discussed later on.8

Melancholia, and more specifically racial melancholia, is a large part of understanding the concept of haunting. Haunting is necessitated by loss, specifically the inability to reconcile that loss. Racial and/or diasporic melancholia’s articulation of loss is notable, and may allow further penetration into the concept of haunting. In the Melancholy of Race, Cheng articulates that in Freud’s Mourning and Melancholia, melancholia is understood in opposition to mourning, which is a healthy response to a lost object; “it is finite and accepts substitution.”9However, melancholia “on the other hand, is patho-logical; it is interminable in nature and refuses substitution; it is this melancholic cannot ‘get over’ loss.”10 There is an element of both desire for and denial of the lost object. It is “in a sense, exclusion, rather than loss, is the real stake of melancholic retention and it is this very exclusion that turns the lost object in to something ‘ghostly.’”11It is a “spectral drama” in which this lost object is felt and desired, but consequentially denied, creating a ghost. White identity works in this way—a contradictory mix of desire and consumption of racialized

42 Thai Hwang Judiesch

peoples along with revulsion, exclusion, and denial. It is the racial other that are made into ghosts. However, I want to focus specifically on how this melancholia manifests within racialized peoples and diasporic haunted memory. Diasporic peoples have a melancholic relationship with “home.” There is both a desire for this lost place, and a denial and exclusion of it, that comes with negotiating their identity and the physical space they embody. This too is a “can’t get over it” loss. Like Hartman expresses with the phantom pain, this loss holds a ghostly presence; although the “limb” is gone, the haunting remains. This “exclusion” could be the diasporic subject’s literal denial of their “home” country (my grandparents refusing to teach my mom and her siblings Korean), or this could be the way in which they feel excluded from this identity (my inability to speak Korean and thus feeling excluded from Korea and other people within my community).

In Ghostly Matters:Haunting and the Sociological Imagination by Avery Gordon, Gordon articulates

that “haunting is a constituent element of modern social life. It is neither pre-modern superstition nor individual psychosis; it is a generalizable social phenomenon of great import.”12 In a world structured by colonialism and capitalism, haunting characterizes the daily existence of modern social life. The figure of the ghost is both there and not there. It is “a seething presence, acting on and often meddling with takenfor-granted realities, the ghost is just the sign, or the empirical evidence if you like, that tells you a haunting is taking place.”13

It is seeing and not seeing. As Cheng has articulated, it is both the desire for this lost object and the denial of it that characterizes this haunting. Gordon, Cheng, and Hartman flush out the a ective and intangible experience of memory and racialization. The haunting is a “structure of feeling of a reality we come to experience, not as cold knowledge, but as a transformative recognition.”14 In The Literature of the Indian Diaspora: Theorizing the Diasporic Imaginary, Vijay Mishra articulates that “when

not available in any ‘real’ sense, homeland exists as an absence that acquires surplus meaning by the fact of diaspora.”15 Again, it is the absence that characterizes this haunting.

For the Asian diasporic communities of North America, what is felt, but also denied, is not just the absence of homeland, but the imperialism, colonialism, and capitalist-modernity that reign over the absence of home. In Haunting the Korean Diaspora, Grace M. Cho articulates that “narratives of Western progress play a large part in producing ghosts through this very process of epistemic violence.”16 Cho finds this ghost within the figure of yanggongju, the Korean women who served as sex workers for the United States of America’s military within Korea. “Behind the image of friendly and cooperative U.S.–Korea relations, 27,000 women sell their sexual labor to U.S. military personnel in the bars and brothels surrounding the ninety-five installments and bases in the southern half of the Korean peninsula.”17 They are both present and utterly invisible. Again,

43

For the Asian diasporic communities of North America, what is felt, but also denied, is not just the absence of homeland, but the imperialism, colonialism, and capitalism-modernity that reign over the absence of home.

ghosts may be found in absences, and to reveal the phantom “is to focus on gaps.”18 Cho discovered these gaps partially through the internet. She cites an interview published on www. halfkorean.com, a website for half-Korean people to connect and form a sense of community over their Korean identity:

“What is your ethnic mix?

I am Korean/Caucasian. My mother is Korean. How did your parents meet?

I’m not exactly sure how they met. All I really know is my father was stationed in Korea when he served in the Air Force.”

The “I’m not exactly sure” speaks loudly to the unspoken trauma and the absence of the figure of the yanggongju. Too, it is this very absence within the history of Korea that haunts this interview. It is the haunting of American imperialism that created this figure of the ghost within the yanggongju. American imperialism in Korea has been largely denied throughout history. The U.S-Korea treaty was even described by former U.S President Ronald Reagan as the “auspicious beginning of an enduring partnership,”19 which overlooks America’s imposition of their military government into Korea, and their support for Japan’s colonization of Korea.20 U.S imperialism has been an enduring presence throughout Korean history, and has been denied and excluded from Korean o cial memory. The yanggongju thus becomes the embodiment of this denial, and can be found in the absences. Like Hartman articulates with the phantom limb—this loss is traced through absence, and for Hartman it is the recognition of “the amputated body in its amputatedness.”21 Cho sees “fleshing out the ghost” in a similar way that Hartman sees re-membering; it is not just through seeking out places of absence, but “in the insistent recognition of the violated body as human flesh.”22 The fleshiness of remembering what is intentionally forgotten is important. This ghostliness is a body that has survived trauma, and this must be recognized and fleshed out.

I found it notable that the spaces in which Cho was trying to seek out this ghost were online. Although the internet is considered this symbolic space of the future, past and memory erupt on these online platforms. How does remembering, forgotten past, haunting, and ghosts work in the online sphere? What does it mean to recognize ghosts as flesh online, where physical bodies feel largely absent? Cho finds her ghost in the figure of the yanggongju, however, for my investigation into the hauntings of the online Korean diaspora, I would like to

44

(Fig. 1, @koreanarchives,2021).

trace the mudang, or the Korean shaman. The mudang has been a somewhat shadowy figure in my own life, and I find her increasingly becoming both visible and invisible online. A mudang shadowed over my grandparents’ marriage—my grandmother, a devout catholic, told me once that a mudang warned my grandfather’s mother that it would be bad luck for her son to marry a catholic woman.

What punctuated the sentence, but wasn’t spoken out loud, was the significant inheritance my grandfather lost when his father died suddenly while he and my grandmother had immigrated to the U.S. The next time I came across the mudang was on Tumblr, in a post about Asian witches. I became wrapped up with this figure, trying to access as much as I could from her online. The mudang as a figure operates in a similar way to the yanggongju; she is both visible and invisible, and “vacillates wildly between overexposure and a reclusive existence in the shadows.”23 Although the yanggongju remains much more shadowy with little discourse surrounding her, they both share some similarities. The mudang is a sort of embodiment of pre-capitalism and pre-western notions of modernity in Korea, with Korean shamanism being an Indigenous Korean tradition. A tradition that, with the onset of modernity and in the name of progress, was heavily policed and restricted.24 What was seen as “superstition” was the antithesis of modernity. Both Japanese colonial police and Christian missionaries tried to eradicate the shamanistic tradition in Korea.25

This figure of the yanggongju is also embodied in the haunting of colonial-

ism and imperialism. The mudang is far from a figure simply relegated to history. She still remains a liminal but present figure in “modern” Korea and her services are still utilized by many Koreans. However, most don’t discuss their use of mudangs publicly out of fear of appearing overly suspicious.26 She remains an unruly woman and is to be feared as a possessor of spirits. Within the Korean diaspora, this concept of the haunting of this figure is made quite literal by the “spirit sickness” that characterizes the calling to be a Korean shaman or mudang. One woman expresses her experience as a Korean diaspora person living in the U.S and receiving the calling.27 She and others are quite literally being haunted by their ancestral lineage, and denying the calling to be mudang often allows the symptoms to persist.28 This is a haunting that demands to be faced. As Gordon expressed, this is not superstition, but a past that lives and breathes in the present with spirits and ghosts that demand to be seen.29

The mudang became a shadowy trace through which I tried to understand my own haunting. Somehow, she felt like a path to re-membering, and if I could only flesh out the ghost of the mudang, I could somehow work through my own loss. The internet became my most valuable resource. Gordon articulates that these new technologies operate with a sort of “hypervisibility” in which it is hard to distinguish presence from absence.30 She goes on to explain that “in a culture seemingly ruled by technologies of hypervisibility, we are led to believe not only that everything can be seen, but also that everything is available and accessible for our consumption.”31

45

In the time that Gordon is writing, the internet was still somewhat in its early days, and she is focused on discussing television. However, her understanding of hypervisibility speaks to the internet well, and allows us to understand the di culties of tracing absence online. I discovered the mudang as a chance encounter on Tumblr—I was surprised that this was the first time I had come across her. With the internet being one of my only tools to access some understanding of my ancestry growing up, I thought I had known everything there was to know about Korea. South Korea on the internet remains a hyper visible presence—with K-pop, Korean fashion, and K-dramas dominating not just the Korean internet sphere, but also Western internet fan culture. Korea dominates “Asian” entertainment in the West, and has become a culture industry powerhouse.32

It only takes a quick search for “Korea” or “South Korea” on Twitter, Tik Tok, YouTube, or Instagram to be flooded by images and videos of K-pop stars, starlets, actors, and celebrities that dominate the discourse. In this milieu of hypervisible Korean celebrities, it is hard to feel the presence of absence—everything is not only seen, but is readily available for consumption. In the hyper-visibility of South Korea as a cultural industry, this underbelly of Korean identity on the internet was not accessible to me when I didn’t know where to look. A chance encounter was the only way in which I could find a trace, but once I found it, a community slowly opened up to me. On social media, the ghost of the mudang is being fleshed out by communities, activists, and modern day mudangs. These folks have a space to discuss and construct a forgotten memory, which breathes life into an ancient tradition that was threatened to ghostly obsolesce as modernity and globalization consumed the world. Re-membering is the process of bringing life to Korean shamanism as a forgotten memory. With the help of social media, communities don’t need a government sanctioned o cial memory place—

they could create their own. In Fixing the Floating Gap: The Online Encyclopedia Wikipedia as a Global Memory Place, Pentzold determines that memory is a collective experience, and it requires a group that is placed within space and time to remember it.33 Moreover, Pentzold cites a memory place “as any significant entity, whether material or non-material in nature, which by dint of human will or the work of time has become a symbolic element of the memorial heritage of any community.”34

Pentzold identifies the internet’s role as a new memory place that doesn’t need to rely on an o cial memory; “the web presents not only an archive of lexicalized material but also a plethora of potential dialogue partners. In their discursive interactions, texts can become an active element in forms of networked, global remembrance.”35 Pentzold determines that the internet allows for “divergent interpretations of the past” to be a part of the collective memory dialogue. There is a form of collaboration that Pentzold sees the internet engaging in, specifically on Wikipedia. He determines that it “is not a symbolic place of remembrance but a place where memorable elements are negotiated, a place of the discursive fabrication of memory.”36 With multiple people being allowed to contribute to the Wikipedia pages, he sees this space as a negotiation of memory in which it can be collectively discussed and constructed. However, Wikipedia is heavily monitored, usually to protect from vandalism, but perhaps this restricts users to engage with this discourse.37 Social media is possibly a more viable medium to see collective memory at work and to serve as memory places.

I decided to use Instagram as my primary platform of research—Twitter, Tik Tok, and YouTube all had interesting content about how the Korean diaspora was grappling with this figure. However, using just one platform allowed me to concentrate my search. I would like to establish that since I am primarily looking at English language content on these online spaces, my work

46

“With the help of social media, communities don’t need a government sanctioned o cial memory place—they could create their own.”

reality—oftentimes as a political tool. I used the hashtag #mudang, #koreanarchives and #koreanshamanism to identify the di erent creators, posts, and community networks. It is important to note that in #koreanarchives, the posts and/or pages may not explicitly be about Korean shamanism or the figure of the mudang. However, these archival spaces online also assist me in understanding how the past is remembered online, and if the figure of the mudang has a space within this remembering. In my search I found three creators of note: @ shaman.mudang, @koreanarchives, and @themudang.

In discussing explicitly archival historical content, @koreanarchives is engaging in an interesting project. It asks people within the Korean diaspora to send in family archival material in the form of photographs. It is a project that works to curate a collective archive in which people contribute their own stories. I found the figure of the mudang in these archives, but she was hard to make out. The photo struck me when I first saw it—a figure in the shadows. The mountains of Korea just behind her (see fig. 1). Her figure is present, but her face remains invisible. It is a beautiful photo that encapsulates the mudangs continued haunting within the online sphere. This online memory place is a space of loss and longing. It is the diasporic hereafter, in which people attempt to construct some sort of collective understanding of a Korean identity. In this photo, the mudang still remains a shadow, however, it o ers a space for remembering. I felt the loss most acutely in this photo; it was a trace, but something I couldn’t necessarily hold

will be specifically focused on how the diaspora negotiates the figure of the mudang online. I can not speak to her presence or absence within Korean language spaces. Moreover, I would like to create a distinction in the way I saw folks fleshing out the ghost of the mudang on social media online spaces. First, there is the figure of the mudang as a historical figure within the archival space. Second, there is Korean shamanism and the mudang as a lived reality and tool for revolution and social change.

These two approaches to the mudang are definitely not distinct categories or a binary. Moreover, oftentimes creators will engage in both impulses through using their platform as an archival memory space for the history of mudangs in Korea, and using this shamanism as a lived

47

(Fig. 2 @shaman.mudang, 2020).

Fig 3. @themudang, 2021).

onto. However, this photo held possibility, and through the other creators I researched I saw the ways that this figure, and these stories, were being maintained and were resurging. (Fig. 1, @koreanarchives, 2021).

The creators @shaman.mudang and @themudang are self-identified Korean shamans and mudangs. They primarily engage in the second impulse, and they utilize Korean shamanism as a lived reality. They call back to this as an ancient tradition, but also assert their continued existence in this time. Not as a “superstitious” tradition of the past, but a community of diaspora folks whose relationship with the figure of the mudang is being worked out now. This includes sharing a few of their practices, such as ancestral worship, their clothing and traditional dress, and a look into rituals they engage in (see fig. 2, fig. 3, fig. 4).

Creators such as @shaman.mudang and @themudang also post explicitly political and revolutionary content. There is both a move to reclaim the past and to create a new future with a few posts calling on other Korean shamans and cross community spiritual healers such as witches, brujas, healers and lightworkers to merge their collective e orts and powers into protecting protestors during George Floyd protests against police brutality (see fig. 5).

Under this post, we see the hashtags #koreanshaman, #blackpower, and #asians4blacklives. There is a move towards using these spiritual powers for revolutionary means. These creators align themselves with issues