LINKS

ALUMNI IN

COUNTRIES

Apart yet together, in isolating us the pandemic also served to unite us. is past year, alumni all over the world have welcomed RCSI into their lives, sharing stories and exchanging experiences. e quest to halt the devastation caused by COVID-19 sparked our desire to reach out to those who matter to us, personally and professionally, to address challenges together but also just to check in and connect, with this institution, with former classmates, and with peers and colleagues.

e capability to connect was eased by the new normal: the virtual revolution. Calls, meetings, consultations, discussions and events have become our daily life. We observed the global become personal. e ties that bind have never seemed so tight.

e last twelve months have brought fascinating stories of our alumni to life. We have discovered that our thriving global community (in 94 countries) is involved in many exciting endeavours, from oating doctors and ying doctors to the world of Formula One, to alumni working in isolated communities in Northern Canada, in rural Sierra Leone and in the Australian outback. ese far- ung alumni have become closer to the rest of us – just a screen away – as we gleaned insights into their very interesting lives.

With such a rich tapestry of alumni stories to choose from, we decided to make those stories a key feature of this, our annual RCSI Alumni Magazine. In the pages that follow, you can read about alumni all over the world in Going Places (page 8); about alumni whose careers have taken an unexpected twist in Tales of the Unexpected (page 18). You can discover how alumni coped with COVID-19 in the Irish Prison Service (page 44); and read about some memorable rotations experienced by alumni (page 51). Professor Clive Lee tells the truly remarkable story of the Anatomy Department (page 26); and on page 38 we reach back into the archives to explore the history of Sir Charles A Cameron, Dublin’s rst public health specialist, and for whom RCSI has named a new award, the Cameron Award, whose rst recipient is Dr Mike Ryan of the WHO.

Alumni voices are a key feature of the RCSI weekly eNews bulletins. Please do keep your details up to date and sign up on our website (www.rcsi.ie/alumni) to receive them. It’s a great way to keep connected with all things RCSI. We are creating, with alumni inspiration and help, more opportunities to connect. Alumni are involved in leading new innovations like the virtual 2020 Annual Gathering, the North American Engagement Series and virtual catch-ups and class calls. Please do get in touch with the Alumni Relations o ce if you would like more information on any of our activities.

e growing numbers of RCSI Alumni Instagram and Facebook followers show how much we value our sense of community at RCSI, past and present. We encourage alumni to stay in contact. We thank all those alumni who have shown incredible support to current students by mentoring, guest talks and via nancial support. Our particular thanks too, to the alumni panel, who contributed to the magazine, especially Dr Veer Gupta (Medicine, Class of 2012), Graham Widger (Physiotherapy, Class of 2015) and Dr Pui-Ying Iroh Tam (Medicine, Class of 2004).

It is true, however, that while we are all active online, there is no replacement for in-person connections. We look forward to a time when we all can meet again face-to-face. Until then, keep close.

AÍNE GIBBONS DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT AND ALUMNI RELATIONS

Aíne Gibbons

PROTECTING YOUR DATA RCSI is committed to protecting your privacy. To enable you to receive invitations for reunions, events and scientific conferences and to continue to stay in touch with classmates, please keep us informed of any changes to your details. Update your information online at rcsi.ie/alumni, by email to alumni@rcsi.ie or by calling the Alumni Office directly on +353 (0) 1 402 2523.

08 GOING PLACES

Alumni in destinations all over the world 26 STORY OF ANATOMY The place, the people and the art

Professor

18 TALES OF THE UNEXPECTED When a traditional career route takes an unexpected turn ON OUR

The story of RCSI’s first Emeritus Professor Sir Charles A Cameron

For details, see page 15

Professor Moira O’Brien: a trailblazer

The Swan pub: the “Surgeons Local” 44 Class Call

Alumni check in 48 A Life’s Work

Alumnus Dr John Latham (Medicine, 1962) on a life well lived 51 Pride of Placements

Alumni recall their more memorable rotations

55 Alumni Volunteering

Giving back and helping out

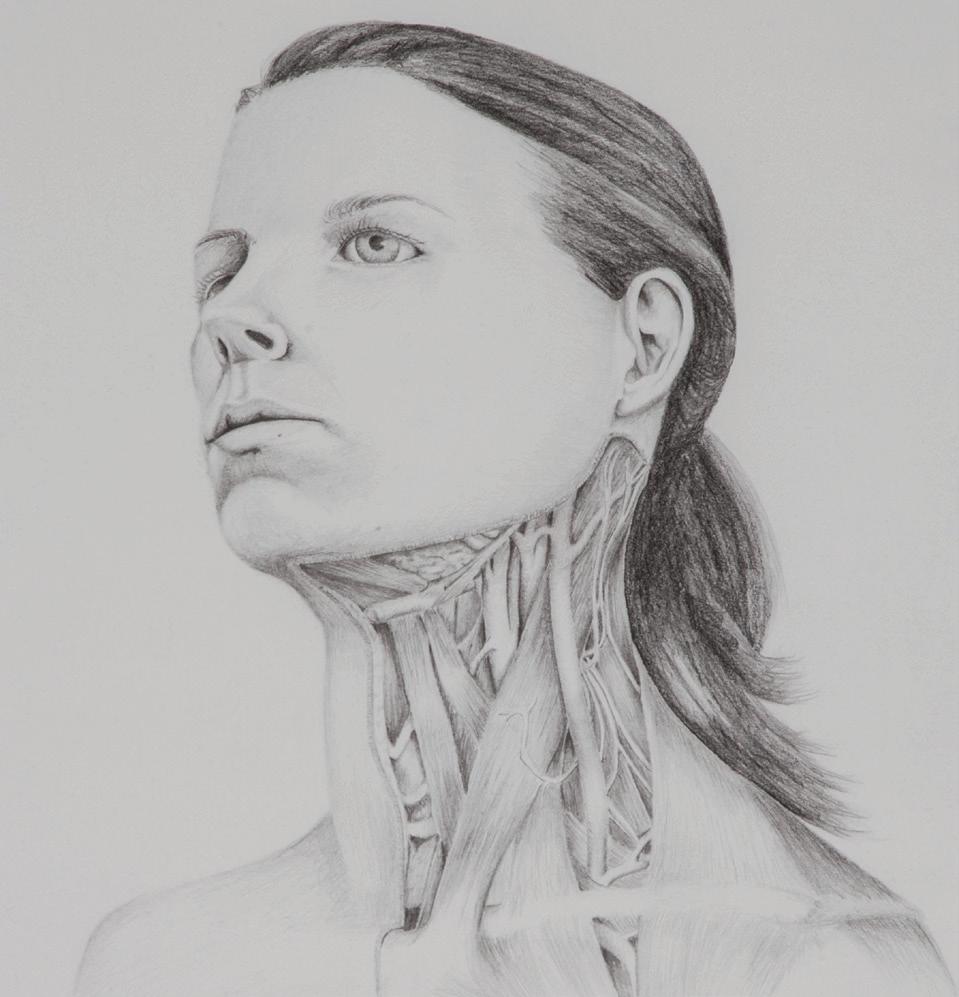

RCSI ALUMNI MAGAZINE is published annually by the RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences. Issues are available online at rcsi.ie/alumni. Your comments, ideas, updates and letters are welcome. Contact Caoimhe Ní Néill, Alumni Relations Manager at RCSI, 123 St Stephen s Green, Dublin 2; telephone: +353 (0) 1 402 8682; email: caoimhenineill@rcsi.com.

RCSI ALUMNI MAGAZINE is POSTED ANNUALLY to alumni who we have listed on our database. To ensure you receive a copy, please PROVIDE YOUR CURRENT CONTACT DETAILS at rcsi.ie/alumni. RCSI ALUMNI MAGAZINE is produced by Gloss Publications Ltd, The Courtyard, 40 Main Street, Blackrock, Co Dublin. Copyright Gloss Publications. RCSI Editorial Board: Aíne Gibbons, Louise Loughran, Jane Butler, Paula Curtin, Stuart MacDougall and Caoimhe Ní Néill.

RCSI was founded by Royal Charter in 1784 as the national training and professional body for surgery. In 1978, RCSI became a recognised College of the National University of Ireland and in 2010, RCSI was granted by the State, the power to award its own degrees. In 2019, RCSI was granted University status and became RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences.

In June 2020, RCSI announced the election of Professor Ronan O’Connell as its new President, following the biennial Council Elections. Replacing outgoing President, Mr Kenneth Mealy, Professor O’Connell is Emeritus Professor of Surgery UCD and Consultant Surgeon at St Vincent’s University Hospital. An international leader in the field of colorectal surgery, he is also the incoming President of the European Surgical Association.

Professor Laura Viani, Consultant Otolaryngologist and Neurotologist at Beaumont Hospital and the Children’s University Hospital Temple Street was elected as the new Vice-President. She is Director and Professor of the National Cochlear Implant Programme and Hearing Research Centre.

Speaking on his appointment, Professor O’Connell said: “It is my great honour to be elected as President of RCSI. My presidency will be like no other in our 236-year history as the COVID-19 pandemic has presented our surgical community with unprecedented challenges that will shape the future of surgery for years to come.

“I am particularly conscious of supporting our surgical trainees whose training has been disrupted by the COVID-19 restrictions. RCSI will use the excellent facilities of the National Clinical and Surgical Skills Centre at 26 York Street to provide innovative ways of training to complement hospital experience.”

Professor Mark Shrime, co-author on the Lancet Commission on Global Surgery, was appointed O’Brien Chair of Global Surgery at RCSI in June 2020. Professor Shrime will lead the University’s Institute of Global Surgery in its work to address the provision of surgical care in low and middleincome countries.

The groundbreaking Lancet Commission Report, “Global Surgery 2030 ”, highlighted the stark and troubling deficit in the equity of surgical and anaesthesia care globally. Every year, an estimated 140 million people who needed surgical procedures

to save their lives or to prevent long-term disability did not get them and an estimated 81 million people who receive surgical care are impoverished by its costs.

Confirming his acceptance of the O’Brien Chair of Global Surgery, Professor Shrime said: “I am tremendously excited to join the stellar team at the RCSI Institute of Global Surgery. I look forward to building on the decade of innovation that the University has driven in global surgery to create a holistic, patient-centred, equity-driven approach to surgical systems strengthening.”

Announcing Professor Shrime’s appointment, RCSI Chief Executive, Professor Cathal Kelly said: “We are delighted to welcome Mark Shrime as the O’Brien Chair of Global Surgery at RCSI. For over ten years, we have pioneered and accelerated change to provide solutions to the surgical deficit, focusing on low and middle-income countries. It is our dedicated surgical focus, research capacity and sustainable partnership model that positions us well to make a significant and lasting impact on surgical access globally. I greatly look forward to seeing Professor Shrime and his team further expand and amplify this important work over the coming years.”

Ahead of the 2020/2021 academic year that began in September, RCSI teamed up with Croke Park Meetings & Events to create a unique satellite campus for medical students to continue their education safely, at the historic Dublin home of the GAA.

RCSI Orientation Day was held at Croke Park and three main learning spaces were created – two for teaching, with a third designated as a study space for students to use between classes. Over 650 students have used these facilities to continue their learning at a safe physical distance, as part of a six-day cycle through the campus.

In addition to being well connected to the RCSI city centre campus and the rest of Dublin, Croke Park is close to Beaumont Hospital, the main RCSI teaching hospital. This proximity of the new satellite campus to Beaumont allowed academics who work there to easily travel to deliver lectures.

Mark Dorman, Head of Stadium Business at Croke Park, confirmed the announcement, saying, “Croke Park is delighted to provide a range of safe, flexible spaces where RCSI can continue the educational experience of future doctors during these unprecedented times.”

Professor Lisa Mustone Alexander has been appointed Director of RCSI’s Physician Associate Programme. The Programme was launched in 2015, and its graduates have played a critical role during the COVID-19 crisis. They have worked across surgical and medical services, with a number staffing some of the hospital testing facilities.

There are now over 135,000 physician associates practising in the US, and the UK has more than 35 programmes graduating over 750 physician associates annually. As well as leading the development and delivery of the programme, Professor Alexander will play an important role in advocating for the recognition of physician associates in the Irish healthcare system and in promoting the value of the role to healthcare professionals.

“With the increasing demands on healthcare systems during the COVID-19 pandemic, educating and utilising physician associates is important now more than ever,” said Professor Alexander. “I look forward to working with my colleagues at RCSI and within the wider Irish medical community to grow and expand not only the RCSI Physician Associate Programme, but the profession throughout the country.”

Professor Alexander joins RCSI following four decades at the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences. She was among the fifth cohort of physician associates entering the George Washington programme in 1977 and went on to teach in the programme and twice serve as its director. From 2009 to 2010, as a Fulbright Senior Specialist to the Rwandan Ministry of Education, Professor Alexander led a feasibility study to determine whether a physician associate model could meet Rwanda’s extensive postgenocide health workforce needs.

A new painting inspired by the RCSI Graduates’ Declaration was officially unveiled last October. “I make these promises solemnly, freely and upon my honour”, created by Mary A Kelly, winner of the RCSI Art Award 2019 in association with The Irish Times and the Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA) Annual Exhibition, was commissioned by RCSI to capture and to honour the ritual of the white coat ceremony and the symbolism of the white coat. During the ceremony, students are invited to make a commitment to professionalism that mirrors the Graduates’ Declaration recited at their conferring day. The Declaration signals the responsibilities they must begin to undertake as future health professionals from the start of their academic training.

Aíne Gibbons, Director of Development and Chair of the RCSI Art Committee, said: “This year, our students are commencing their academic journeys at a time of great challenge and change, and also one of great opportunity. We are delighted to add this powerful painting to RCSI’s art collection. We hope this artwork will inspire generations of students, our future healthcare leaders, and returning alumni.”

Mary A Kelly’s work is widely collected and is included in both the Microsoft and Goldman Sachs collections. She commented: “The ethos of humanity at the core of the RCSI Declaration was the inspiration for this painting.”

RCSI

ranked joint second in the world for adherence to UN Sustainable Development Goal 3: “Good Health and Wellbeing”

RCSI has achieved Ireland’s highest position in the Times Higher Education (THE) University Impact Rankings 2021, coming joint second in the world for “Good Health and Wellbeing”, from a total of 871 institutions. These THE University Impact Rankings recognise universities around the world for their social and economic impact based on the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). For its contribution to SDG 3, “Good Health and Wellbeing”, RCSI’s score increased from 90.8 in 2020 to 93.1 in 2021. In addition, according to the 2021 THE World University Rankings, RCSI has maintained its worldwide position in the #201-250 category and ranks second out of nine institutions in the Republic of Ireland. RCSI’s performance in this latest ranking is linked in particular to its continued strength in research with the impact of its publications in translational medicine and health sciences in areas including cancer, neuroscience, population health and surgical science and practice ranked highest in Ireland. RCSI continues to perform strongly in the area of international outlook, currently ranked 52nd in the world.

In November 2020, RCSI coordinated its virtual conferring ceremonies for the many nurses, health research scientists, pharmacists and physiotherapists graduating from the University.

Dr Mary D’Alton was awarded an honorary doctorate, in recognition of her position as Chair of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Willard C Rappleye Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology Columbia University Medical Centre, USA, and her achievements throughout her career. In the course of her distinguished work in obstetrics and gynaecology, Dr D’Alton has focused on eliminating the gaps in women’s health, building and strengthening programmes in infertility, minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, gynecologic oncology, family planning, and integrated women’s health care.

RCSI awarded best-selling international author, inspirational speaker, TV presenter and charity campaigner, Ms Katie Piper, an honorary doctorate, for her achievements. The survivor of a horrific acid attack in 2008, which caused extensive damage to her face and blindness in one eye, Ms Piper set up the Katie Piper Foundation which supports survivors of burns, their families and carers and works alongside existing support networks. In 2019, the Foundation achieved a significant milestone, opening a rehabilitation centre in the UK that offers burn survivors the same treatment Ms Piper received in France.

Editor-in-chief of The Lancet since 1995, Dr Richard Horton, was also awarded an honorary doctorate. This year marks Dr Horton’s 25th year in charge of what has been described as “the world’s leading independent general medical journal”. In his most recent book COVID-19 Catastrophe: What’s Gone Wrong and How to Stop it Happening Again, Dr Horton explores the global response to the COVID-19 pandemic, calling it the “greatest science policy failure in a generation.”

The RCSI Institute of Global Surgery and global medical technology company, BD (Becton, Dickinson and Company), recently announced KidSURG, a joint initiative aimed at significantly improving paediatric surgical services across southern Malawi. Created in collaboration with leading Malawian paediatric surgeon, Professor Eric Borgstein, the KidSURG initiative will develop a paediatric surgical network in southern Malawi, to expand surgical access to eight million children. The initiative will also seek to develop and share optimal models for replicating this initiative in other countries. BD has donated $500,000 in cash and surgical products to support the initiative.

Leading healthcare simulation educator and scholar Professor Walter Eppich has been appointed Chair of Simulation at RCSI. Building on RCSI’s significant investment in simulation, Professor Eppich will lead the University’s interdisciplinary Centre of Simulation Education and Research (RCSI SIM) in informing the global growth in experiential simulation-based learning in healthcare and other training and education sectors. Professor Eppich, who joins RCSI from the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Illinois, will also build the University’s capacity to improve patient safety and care through simulation which is embedded across RCSI’s curricula.

Professor Jan Illing has been appointed as Professor of Health Professions Education and Director of the Health Professions Education Centre. Professor Illing will build on RCSI’s strength in health professions education and advance the University’s health professions education research strategy. She will lead on the evaluation of RCSI’s new medical curriculum, support the development of interprofessional education at the University and build international research collaborations.

In April 2020, RCSI launched a fundraising appeal aimed at making protective face masks more comfortable to wear for intensive care staff providing care to COVID-19 patients.

The Comfort for Carers Appeal was a huge success, raising over €18,000 and funding multiple Wound Care Kits for intensive care staff.

According to Professor Zena Moore, Head of RCSI’s School of Nursing & Midwifery: “We are acutely aware of the skin abrasions and pressure ulcers experienced by ICU teams as a result of wearing PPE for prolonged periods on a daily basis. Each Wound Care Kit consists of a set of instructions, moisturiser, tape and wipes. These Wound Care Kits have been developed by the RCSI School of Nursing & Midwifery, as a preventative measure and the School captured data over a 12 week period to document the impact of the kits, with very positive results.”

Ms Helen Mohan FRCSI, was announced as the recipient of the second PROGRESS Women in Surgery Fellowship. Aimed at addressing the barriers to women medical graduates advancing in the surgical profession in Ireland, this prestigious RCSI bursary, funded by Johnson & Johnson Medical Devices Companies, promotes female participation in surgical training at Fellowship level.

Ms Mohan will now undertake a Fellowship in colorectal surgery at Peter MacCallum Cancer centre in Melbourne, Australia. This will focus on advanced colorectal cancer, including training in robotic surgery, peritonectomy and pelvic exenteration.

“ The Ways COVID-19 has Influenced Our Lives and United Medical Forces” was the theme of the address at the 88th Biological Society Inaugural Meeting, which took place virtually in January 2021. The Biological Society (BioSoc) is the oldest student society in RCSI, and the event was organised by students from the BioSoc Committee with assistance from the RCSI Student Services team. At the meeting, exiting Faculty President of the Biological Society, Professor Camilla Carroll (Class of 1985), passed the chain of office to the new Faculty President of the 2020-21 academic year, Professor Rory McConn Walsh.

The Widdess Lecture, “How Our Medical School has Adapted to Covid-19: Implications for the Future of Medical Education”, was delivered by Professor Arnold Hill, Head of the School of Medicine at RCSI, Professor and Chair of Surgery at RCSI, National Advisor for Surgical Oncology for the National Cancer Control Programme and President of the Surgical Research Society. Professor Samuel McConkey, Deputy Dean and Head of the Department of International Health and Tropical Medicine at RCSI, spoke about the COVID-19 vaccination programme. Dr Eoghan De Barra, Consultant in Infectious Diseases at Beaumont Hospital and Senior Lecturer at RCSI, delivered his address: “Discussing the COVID-19 Pandemic”. Dr Eoin Cleere, an intern at Beaumont Hospital and Class of 2020 alumnus of RCSI, gave insights into his experience as an intern during the pandemic.

The RCSI Bahrain campus was a very different experience for new and returning students and staff members this academic year, following the implementation of a host of processes and initiatives designed to combat the spread of COVID-19.

Among the new measures are a one-way system around the campus, plexiglass protection at student-facing contact points, extensive instructional signage to guide people and remind them of precautions, additional hand-sanitising stations, foot-operated door-opening devices, and enhanced cleaning processes.

Access to the campus has been closely managed and monitored in order to adhere to social distancing guidelines, with pre-planned

timetabling and seating arrangements limiting the total number of people on campus at any one time.

As part of the support programme implemented to assist in the safe return to campus, all international students were offered the opportunity to avail of a tailored group health insurance scheme with a flexible payment plan, while the University also offered to reimburse the cost of compulsory COVID-19 tests for those entering Bahrain to attend classes.

On the teaching side, part of the sports hall has been repurposed as additional clinical simulation space, equipped with new simulation equipment, while some lecture theatres and tutorial rooms have been upgraded to facilitate adequate online streaming.

With alumni in

94 countries, the RCSI diaspora

is truly global. Eight alumni tell us about where they live and work

PERTH, AUSTRALIA

ALISON MOLAMPHY

Physiotherapy, Class of 2015

After graduating, I worked in University Hospital Limerick for two years before coming to Perth in 2018. I had no job organised before I arrived, and it took a while to organise the paperwork side of things. I was here for two or three months before everything was approved for me to start working as a physiotherapist.

I work in private practice. I had originally thought I might work in a hospital as that was my experience in Ireland, but you have to be a permanent resident or citizen to work as a physiotherapist in a hospital in Western Australia; it’s di erent for doctors. e practice I work in is based in the Wembley suburb of Perth; we consider ourselves generalists. We have a mix of private and insurance patients, and we run specialist osteoporosis classes. We have a gym and a clinical pilates studio, and I am trained to deliver clinical pilates instruction. In private practice we have autonomy to refer for imaging, which is something I did not have at home when I worked in private practice, and many health insurance schemes cover preventative physiotherapy.

Perth is very beautiful, and can be very hot – it’s 37°C today! It’s very easy to live an active lifestyle, because of the dry, sunny weather. Because of the heat, people tend to be early risers, and things kick o early in the morning and nish early at night. If you are a er late nightlife, there are better places. It’s not uncommon for exercise classes to happen at ve in the morning, and I’m o en in work before 7am. Usually I work three early days, nishing at

“WE ENJOY THE LIFESTYLE SO MUCH.”

lunchtime, and some late days, nishing at 8–8.30pm. I o en work on Saturdays. Accommodation can be quite di cult to come by, and apartment living is not as prevalent outside of the city centre as on the east coast, so house shares are more common. Cost-wise, rents are comparable to Ireland, and cheaper than the eastern states, but eating and drinking is a bit more expensive. ere are lots of Irish doctors here, but not as many physios – there are more in Sydney and Melbourne.

Public transport connections in Perth aren’t as extensive in suburban areas as they are in the centre, as there has been a lot of development over the past decade and the train line has not been extended to reach sprawling suburbs. A car is the easiest way to get around if you are not living directly on the train line. e beaches are amazing and the shopping and restaurants are great. One of the amenities I love is the public barbecues for groups of families and friends. We try and go on trips as o en as possible – there are so many places to visit even just within Western Australia. When we came initially, we thought we would be here for a year or two and then return home, but we extended that because we enjoy the lifestyle so much and it’s one of the very few places in the world where you can live a relatively normal life during the pandemic. Now we have permanent residency so we have the option to stay, but we haven’t made a decision yet.

BETH WOLFE

Physiotherapy, Class of 2017

I’m from Cork originally and two weeks after graduation I moved to Vancouver for the summer to teach sailing at Jericho Beach. Initially I thought it was only going to be for a couple of months but very quickly I decided to stay and I’m still here four years later. I don’t have any immediate plans to go back to Ireland – the more I get settled here, the harder it is to leave. I really love it here but do see myself going back to Ireland at some point in the future.

Vancouver is not a very big city, it’s a similar size to Dublin. It is built on an outcrop of land surrounded by water. ere’s a huge seawall with a cycling and running track that wraps around the city which is absolutely beautiful. Most of the Irish in Vancouver live in an area called Kitsilano. I lived there for a while but I moved downtown to an area called Yaletown. You can see the mountains and the water from my apartment.

As a relatively junior physiotherapist it is easier to get work in a private practice here than it would be back in Ireland. In Ireland they won’t hire anyone to a clinic without a number of years’ experience, but here in Canada they train you up within the practice.

I rst got interested in physiotherapy as a career through a family friend who is a physiotherapist. He worked both with out-patients at a hospital in Cork and with sports teams so I got an insight into both types of work. And I experienced physio as a patient when I had sports injuries and I loved that. In university we spent more time on rotation in hospitals and I didn’t enjoy it as much – I didn’t feel as if I was making any di erence to patients because you have such a short time to see people. In hospital the focus is on getting people mobile enough to get them home, which is what you need to do in that situation, but in private practice sometimes I could get to work with people for a year or more and I feel more ful lled in terms of the type of work I am doing. at’s not to say I wouldn’t work in a hospital again, just that for now I prefer private practice.

It takes me 25 minutes to get to work on public transport, the buses are great. Vancouver is quite an expensive city, on a par with Dublin and Cork, but I am probably earning a bit more here than I would back home. e cost of housing here is through the roof and I have to say that is one consideration in terms of whether I will stay, because to a ord a nice house I think you would have to move quite a way out of the city.

At the moment I feel as if I work all the time. It’s shi work and I usually work ve days, including Saturday. In private practice you do have to work either early mornings or late into the evenings, and you don’t get paid for time o or holidays. Work/life balance can be tricky but I don’t mind it at the moment. My favourite time of year here is summer and the weather is so nice. I love sailing and going to the beach. Hiking and anything to do with the mountains is massive here, I had never really skied or snowboarded growing up, but here I’ve been going snowshoeing. ere are lots of great spots to explore within a couple of hours of the city. e worst thing about being in Vancouver is missing family: I was homesick when the borders closed, it felt so far away. I’m coming to terms with it now.

“YOU CAN SEE THE MOUNTAINS AND THE WATER FROM MY APARTMENT.”

AKSHAY PADKI

I’m originally from India but I grew up mainly in China as my parents were based there for work and I did most of my schooling there, with my last three years of high school in Canada. In my nal year at RCSI, I applied for a job in Singapore as a back–up option, in case I didn’t get the job I wanted in Ireland a er graduation. I was o ered a medical job outside Dublin but I wanted a surgical job so I took up the position in Singapore instead, moving here in August 2015, straight a er graduation. I had never lived here but had visited several times, I knew what it was like.

I did my houseman year – the equivalent of intern year in Ireland – in Singapore. at consisted of three di erent postings: one medical, one surgical and one elective. You are graded on those postings and then you can apply for SHO postings in areas you are interested in, a er which you can apply for a specialist scheme, which is a direct pathway to consultancy. I am applying for the Orthopaedic Surgery Scheme which is quite competitive, but I hope to be accepted this year. ere are only ten to 15 spots a year.

I have worked at several di erent public hospitals including Changi Hospital in Eastern Singapore and the National University Hospital. I am now at Singapore General, the biggest hospital in the country. During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, I helped at the National Centre of Infectious Disease as well.

Singapore is a small country and its healthcare system is very well-funded, e cient and quite advanced. It was a bit of a culture shock at rst, I was surprised how quickly things were done. I remember when I was in Ireland I would have had to take all the bloods myself and wheel the ECG cart around, but here it is more automated and nurse-led. at was both refreshing and interesting to see. Work/life balance here is de nitely less than in Ireland. Saturdays are still technically a half day, and sometimes I have clinics/OTs. On calls can be tiring as well and the following day you’re expected to continue your normal duties until around noon when you can go “post call”.

I’ve always been comfortable in big cities, and I enjoy living here but there is no beach near the city and although we have some parks there is not much access to large parks/nature trails. One of the biggest draws is the proximity to SE Asia, which is cheap and easy to get to. Prior to the pandemic, we would have gone on holiday somewhere every two months or so, to Bali, ailand, Cambodia or Vietnam. Singapore is one of the most expensive cities in the world – as a nonSingaporean doctor you get a housing allowance when you arrive, which helps. If you are looking to buy, the prices are astronomical so you are likely to be renting here longer than you might in other cities. Cars are expensive too, but food and day-to-day expenses are reasonable. Public transport is very e cient,

“THERE IS GREAT NIGHTLIFE HERE, IT IS A VERY VIBRANT CITY WITH LOTS OF YOUNG WORKING PROFESSIONALS.”

I usually take a taxi to work in the morning, which takes about 15 minutes, and get the MRT home, which takes about 40 minutes.

I did not originally intend to stay in Singapore, but I met my wife who is Singaporean and we are settled here now for the foreseeable future. ere were about 20 other Irish medical graduates who arrived here the same year I did and we meet up fairly frequently. We go out for drinks and dinner. ere is great nightlife here, it is a very vibrant city with lots of young working professionals. But now it’s less nightclubs and more going to cafés and walking the dog.

DR JEYSEN YOGARATNAM Medicine, Class of 1999

A er graduating from RCSI, I moved to the UK to pursue training in Cardiothoracic Surgery and completed a PhD. In 2008, while I was coming to the end of my training at the Royal Brompton Hospital in London, I began to realise that opportunities to progress my career in cardiac surgery were diminishing. Many of my more senior colleagues who had completed their cardiothoracic surgical training found it very challenging to secure consultant positions in the UK.

“WHEN WE MOVED HERE FROM THE EAST COAST, OUR HOUSE HALVED IN SIZE BUT OUR MORTGAGE DOUBLED!”

I was keen to explore opportunities outside academia in the area of biotech–based clinical research and joined a world class biotech organisation, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), in the UK to explore and pursue a new career as a clinical drug developer. at was 13 years ago and I have not looked back since! Within two years, I was promoted and BMS relocated me and my wife to Connecticut and later I secured a place at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Sloan School of Business, to pursue an MBA. While in Boston I worked with Vertex and following the completion of my MBA in 2015, my family, now including two children and a husky, decided to move to sunny California.

I transitioned to a more senior role as a drug developer at Janssen Pharmaceuticals (a Johnson & Johnson Company) in the Bay Area of San Francisco, USA. While working in the Bay Area, I have held increasingly senior roles as a drug developer at a number of di erent biotechs, leading the early clinical development activities of a number of di erent novel therapeutics in the areas of chronic hepatitis B, C and D and in uenza. In my current role at Aligos erapeutics, I was incredibly fortunate to be able to join the company while it was just a small private start-up biotech. In my role, I lead and advance the clinical development of many novel therapeutics through early clinical development that ultimately enabled the company to transition into a successful publicly traded biotech.

California is beautiful and the amazing weather is a huge attraction for my family. We live in a suburb of San Francisco, in the East Bay, called Danville. In this part of the Bay, it is possible for us to drive up to the slopes of Lake Tahoe for early morning skiing and still be able to drive back to the Bay Area beaches to catch the late a ernoon sun and waves. It also o ers some of the best US public schooling systems and recreational activities for our growing boys.

e San Francisco Bay Area is consistently ranked in the top two of the best biotech hubs in the world. As such it o ers ample professional opportunities for me to continue to grow as a drug developer. Furthermore, it has world class hospitals and healthcare systems that o er fantastic opportunities for my wife to grow her career as an intensive care nurse.

While the Bay Area of California is a fantastic area to raise a family, it is one of the most expensive places to live in the USA. When we moved here from the East Coast, our house halved in size but our mortgage doubled! Tra c is frequently awful in the Bay Area, though it has improved since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, in order to avoid sitting in tra c for two hours or more, I used to leave the house at 5am each morning to travel the 50 miles to my o ce in South San Francisco. To avoid the evening tra c, I used to leave the o ce by 3pm.

e COVID-19 pandemic has brought a whole new way of balancing work and life that I would never have thought possible, showing that it is possible to be a successful biotech executive while working from home. It has brought us closer together as a family.

My wife and I became US citizens in 2018 and we love every part of contributing to our new home country. It has o ered our family opportunities beyond our expectations.

“I LOVE IT HERE. MALAWI IS KNOWN AS THE WARM HEART OF AFRICA, AND THE PEOPLE ARE WARM AND FRIENDLY; AND THE COUNTRY IS BEAUTIFUL.”

I’m originally from Hong Kong and did a rst degree in the US before going to RCSI for my medical degree. A er graduating, I stayed in Ireland for two years and, a er nishing my SHO posts, I went to the US for residency and fellowship. At the time I nished fellowship the plan was to move to Nigeria, but we ended up staying in the US and I got a faculty position in Minnesota in Paediatric Infectious Diseases, where I stayed for four years. roughout that time my interest in global health and working in sub-Saharan Africa never waned. I realised several years a er arriving in Minnesota that even though I was enjoying what I was doing there, it wasn’t the work that had inspired me to go into medicine in the rst place. I started looking around and found this position at a research institute in Malawi and came out here in 2016.

I am a senior scientist at a clinical research institute, the Malawi-Liverpool Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Programme; the parent institution and my employer is the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine in the UK. I am based in Malawi fulltime and head the Paediatrics and Child Health Research Group. My work is a combination of clinical work, where I am a consultant paediatrician in the government hospital, and clinical research, which focuses on infections in children relevant to this setting. We see a lot of pneumonia, diarrhoeal disease and sepsis caused by bacteria that are resistant to our commonly used antibiotics. I recently led a multinational clinical trial evaluating a novel treatment of diarrhoea in HIV-infected patients, and currently am the local lead for a multicountry clinical trial evaluating empirical treatments for HIV–infected infants with severe pneumonia.

Before I came to live in Malawi, I had been to many other parts of Africa but not this country. I love it here. Malawi is known as the warm heart of Africa, and the people here are warm and friendly; and the country is beautiful. I have

lived in many cities around the world and I think what I have traded o in terms of urban activity, such as art galleries and museums, is made up for with a lot more outdoor activity and a better quality of life in many ways. With my family we go hiking, we visit waterfalls and wildlife reserves and Lake Malawi is just a couple of hours away.

Blantyre is the second largest city in Malawi, with an urban population of about a million. I live in a neighbourhood where I have my own plot of land, and a house with a huge garden overlooking a river. It’s a ten-minute drive to the hospital. ere are several international schools in the area, so my children have choices. My research is organised around my own schedule and can happen at all hours, but I enjoy it and the work is meaningful and interesting. One of the most satisfying aspects of my work is helping to develop the careers of the (currently twelve) junior researchers who I am supporting, from masters to PhD and postdoc level, in addition to the medical students, clinical o cers and registrars that I am teaching, supervising and mentoring.

It’s too early to say if I will make Malawi my permanent home. I would like to return to Hong Kong but this is looking increasingly unlikely as Hong Kong is going through political change; I could move to the UK or Europe; and my children were born in the US so they are US citizens. I haven’t yet decided which path to take next. I am in the process of certifying as a professional coach, and am coaching other physicians and academics as an executive/ leadership/ life coach. I help early/mid-career women who are trying to balance career and family and nd a way to create the life they were meant to live (reach out to me on LinkedIn).

It’s something I can do with anyone anywhere in the world. So I feel like a truly global citizen, because where I am located does not limit me in any way.

I am originally from Niger state, two hours away from Abuja, the capital of Nigeria, where I live now. I was away studying for eight years, I did A-levels in the UK before attending RCSI in Bahrain. I got married just before graduation and moved back to Nigeria in July 2019. I had been missing home and was happy to return.

It was not easy to nd a job here; there is no standardised recruitment process for internship. As a foreign medical graduate you have to enrol in a privately run training programme to prepare you for a licensing exam. When you pass, you are inducted into the Medical and Dental Council of Nigeria (MDCN) and you are given a provisional license to do a one-year internship, a er which you receive your permanent license from MDCN. Having the provisional license doesn’t guarantee an immediate intern place though, you have to apply to multiple places and it can take several months or even years to nd a job. ere are so many medical graduates and not enough spots, it’s a big issue and COVID-19 made everything worse. I sat for the licensing exam in November 2019 and got the results a week later but the induction ceremony did not happen until February. I got my license then and applied to hospitals immediately but was not called to an internship position until December. I was hanging around for months with no clear indication of when I was going to be called, and yet the National Hospital of Abuja, the main government hospital, where I currently work, was functioning without house o cers for several months. I was on maternity leave from January to April.

“I HOPE TO STAY IN ABUJA AND MAKE MY LIFE HERE, AND WOULD HOPE TO DO MY RESIDENCY IN THE SAME HOSPITAL.”

When I nish my internship, I have to apply to do a one-year service to the country with the National Youth Service Corps, which is compulsory for everyone under the age of 30. As a medical graduate I will do this in a clinical setting and a er the year I will sit an exam and then apply for residency. I hope to stay in Abuja and make my life here, and would hope to do my residency in the same hospital.

I had never lived in Abuja before but I have family here and used to visit o en. e population is around a million, it is nothing like Lagos, which is huge and very densely populated. It’s a busy city and getting busier, there are better job opportunities here than in other cities and the standard of living is good. Rents are high, there are lots of nice restaurants and we have a few malls. ere are some parks and lakes, which are nice for picnics with friends. I live a 20-minute drive from the hospital. e worst thing about Abuja is the tra c, but it’s not as bad as Lagos. Schools are expensive here, you have to pay a lot for good quality education and you have to plan for that.

DR KINAN ALRYAHI

Medicine (Bahrain), Class of 2017

My father is Palestinian, my mother is Bosnian and I grew up and went to school in Jordan. I went to RCSI Bahrain because it was close to home. I did my intern years in Jordan. When I was nished I wanted to get a place on an Ophthalmology Residency Programme. I thought I would go to the UK but my father, who is an ophthalmologist, wanted me to go to Sarajevo, where he studied. We had an on-and-o conversation for a while but I eventually decided to come to Sarajevo as I would get more hands-on experience here and the residency

programme is shorter and less competitive. My father and older brother have a private clinic here.

I arrived in Sarajevo in 2019 to start the four-year residency programme at the University Hospital. I had visited the city a few times before, and had a good sense of it. I get good hands-on experience with my father and brother in their private practice, where they do some pro bono surgeries for people who cannot a ord to pay. In the public hospital the machines tend to be quite old, but we get a lot of rare cases and diseases.

Between the hospital and the clinic I work 8am to 8pm every day, with one day o . Sarajevo is a small city where a lot of people know one another. People are very friendly and the cost of living is pretty low. If you want to go away, it’s easy to jump in the car and head to Croatia, Serbia, or Italy. I wouldn’t be here if there weren’t good restaurants! ere is a good social life. e university has delivered its medical programme in English for about six years so the school of medicine is growing and there are many international students. My plan is to stay in Sarajevo. My family hopes to expand the clinic into a hospital and start an Ophthalmology Residency Programme; that’s our aim. I’m excited to do that in Eastern Europe because there are not a lot of opportunities in the region and it will give more access for people who want to pursue a career in ophthalmology. It is a great goal for me.

Nursing (Bahrain), Class of 2015

I am originally from Bahrain, and a er I completed my degree I took a gap year in Austria, teaching high school students there about Middle Eastern Culture. When I returned to Bahrain I initially worked in the private sector and then took a job at the Ministry of Health working as a nurse in primary healthcare. en I was awarded a Fulbright scholarship o ered by the US Embassy in Bahrain and I moved to Idaho in 2020 to study for a master’s degree in public health. I work part-time in a public health department as a contact tracer for COVID-19.

I love it here in Boise. It is very safe and the people are friendly; it feels very family-centred. It’s a fast-growing city, as many people are moving here from

“SARAJEVO IS A SMALL CITY WHERE A LOT OF PEOPLE KNOW ONE ANOTHER.”

California because it is safer and cheaper. I live o campus in an apartment, it is very di erent to home but there are so many students here I have found it easy to make friends. Boise has everything you want in a small city – with mountains, parks, hiking trails and a river. I love the countryside and spending time with friends outdoors.

e scholarship gives me a monthly stipend but it’s quite expensive here –it’s a city on the rise and you can really feel it getting more expensive. At rst I used public transport but a er a few months I did my driving test and got a car, which makes it much easier to get around.

I have three classes per week, some in person and some online. e work takes me the whole week to prepare; working and studying is tough. It is a two-year course, a er which I have to go back to Bahrain and do something useful for my country. In Bahrain I plan to work as a public health professional. I am studying prevention and intervention and will be able to work on health promotion programmes. If I want to return to the US, I’ll have to wait two years before applying for residency. I’m not sure yet whether I will do that. ■

“BOISE HAS EVERYTHING YOU WANT... MOUNTAINS, PARKS, HIKING TRAILS AND A RIVER.”

e third annual RCSI Alumni Awards ceremony took place on 25 April. While the outstanding achievements of the six RCSI Alumni Awardees for 2021 could not be marked in person, the University honoured these global healthcare professionals in a virtual celebration attended by fellow alumni, faculty, family and friends

When the Alumni Awards 2020 became a casualty of restrictions imposed by the global pandemic, little did we expect that these same conditions would prevail in 2021. For the second year running, the University acknowledged its awardees virtually.

e Awardees, one from each of the six Schools, were chosen on the basis of their extraordinary accomplishments in their own eld that have contributed to patient welfare and the business of health care, and have also enhanced the reputation of the University globally.

Alumni from all over the world were invited to nominate classmates and peers. Written submissions were assessed by a panel of judges led by RCSI Chief Executive, Professor Cathal Kelly; Dean of RCSI, Professor Hannah McGee; Professor Arnold Hill (Medicine); Professor Suzanne McDonough (Physiotherapy); Professor Tracy Robson (Pharmacy and Biomolecular Sciences); Professor Zena Moore (Nursing and Midwifery); Professor Niamh Moran (Postgraduate Studies) and Eunan Friel (Institute of Leadership).

Aíne Gibbons, Director, Development and Alumni Relations, RCSI said: “We are extremely proud of the recipients of these special awards, our distinguished alumni who are united by their time spent at RCSI. eir enduring contributions to the betterment of human health are extraordinary. We look forward to receiving nominations for the 2022 Alumni awards and to being able to gather in person to honour another cohort of exceptional RCSI alumni.”

RCSI acknowledges the support and contribution from our Alumni Award sponsors

Rising Star Award, supported by Physiologix

Outstanding Clinician Award, supported by 3M

Ambassador Award, supported by Novartis

Research and Innovation Award, supported by HealthTech Ireland

Humanitarian & Community Award, supported by Medical Protection

Positive Global Impact Award, supported by Bon Secours Health System

MR STEPHEN O’ROURKE School of Physiotherapy

Stephen trained as an actor at e Samuel Beckett Centre, Trinity College Dublin, and worked as a professional actor and performer before entering the world of physiotherapy. After graduating from RCSI in 2014, he worked as a rotational Sta Grade Physiotherapist in Beaumont Hospital and in both vestibular and musculoskeletal private practice, pioneering Ireland’s rst Healthier Dancer Programme and Injury Screening Programme. He undertook research examining injury incidence and physical tness in aerial dance performers, with the support of RCSI and the Irish Aerial Creation Centre.

In 2016, Stephen became Company Physiotherapist for Riverdance and toured China, visiting 18 cities. In 2017, he went on to become Senior Physiotherapist at Franco Dragone’s e House of Dancing Water Show in Macau, looking a er more than 100 professional international performers, from former Olympic gymnasts to cli divers and elite motocross riders.

Stephen says he loved his time at RCSI, singling out one lecturer for special mention: “I began my physiotherapy studies as a graduate student with the intention to work in musculoskeletal medicine with performers. Louise Keating was assigned as my personal tutor. When I discovered she had previously worked and toured with Riverdance, I knew I was in the right place. Louise was and is a huge inspiration to me.” He says that RCSI set the standard for the quality of care he delivers to patients: “RCSI instilled a strong ethos of looking to evidence-based practice and international best practice in me. is has guided my physiotherapy practice throughout my career.”

Stephen says being selected for the Rising Star Alumni Award is a huge honour. “It is an encouragement to continue to strive for excellence and new heights in my future career.”

DR CLARE LEWIS

School of Nursing and Midwifery

Clare is Deputy Chief Nursing Officer in the Department of Health, supporting the Chief Nursing O cer with policy and strategic development, as well as clinical and operational expertise, to translate policy into practice.

Clare has over 20 years’ experience in advanced practice, working in both primary and secondary care settings and in areas of chronic disease management and older persons’ care. Clare worked across hospital and community, supporting GPs and the primary care team to provide rapid access to diagnostic nurse-led clinics, care at the front door (emergency department), in-patient consultation services and domiciliary care.

As part of her PhD research, she developed and tested Ireland’s rst Community Virtual Ward, which supports older persons with complex health and social care needs at home, thereby reducing unplanned hospital admissions and emergency department presentations. is model of care has been recognised nationally and internationally to improve integration and complex care provision in the community.

Clare says the education she received from RCSI in uenced her approach to policy and strategic development. “I start from the patient/service user, building care and services around them. RCSI prepared me by developing my knowledge and skills to lead on innovation, to critically analyse and synthesise evidence, translating it into practice, as well as teaching me conceptual models, frameworks and methodologies to develop and evaluate policy to advance practice. I am truly honoured to receive this award. I dedicate it to my husband Je , my sons Tristan and Adam and my late mother Margaret, who have been so supportive throughout my academic journey. I hope this award will inspire nurses and midwives in the future.”

MS LOUISA POWER School of Pharmacy and Biomolecular Sciences

Louisa, Chief Pharmacist for Pharmacy Services in the HSE Community Healthcare Mid West, graduated from RCSI in 2007. She has worked in both traditional and non-traditional pharmacy roles, always striving to promote the profession and ensure excellent pharmaceutical care. Her particular interest is in the role of the pharmacist in ensuring medication safety and medicines optimisation across all divisions of healthcare.

In her early career, Louisa took the opportunity to work in other healthcare systems before returning to Ireland to take up the post as the rst Medicines Management Inspector with the Health and Social Care Regulator in Ireland, forging a path for pharmacists to work in this area in the future.

Due to her family background in pharmacy, Louisa has always been passionate about the practice of community pharmacy. She was elected a member of the Council of the Pharmaceutical Society of Ireland and sits on the PSI Risk and Audit Committee. Louisa is part of the Peer Support Network with the Irish Institute of Pharmacy.

While a student at RCSI, Louisa says Professor Judith Strawbridge was a key inspiration. “She brought enthusiasm, positivity and energy to every lecture. Professor Strawbridge had the great skill of imparting a huge amount of knowledge in a manner that was easily understood and accessible for all students.” Professor Strawbridge also played a key role in Louisa’s decision to choose the path of hospital pharmacy on graduation. “I didn’t believe in myself but Professor Strawbridge’s belief that I could t into this world kept me pushing forward. is had a signi cant impact on me, as a young person, that a respected professional was so invested in my journey.” Receiving the award was a huge honour, she says: “I am proud to be a member of the RCSI family and to be recognised by my alma mater.”

DR EVA BUNK School of Postgraduate Studies

Eva studied Biology at Westfälische WilhelmsUniversität Münster, Germany before undertaking postgraduate studies in the Department of Physiology and Medical Physics at RCSI.

e title of her PhD thesis was “E ect of Gene Knockout and NMDA Receptor Modulation on Cell Survival and Neuronal Stem Cell Fate in in vitro and in vivo Models of Excitotoxicity”. Having studied adult neural stem cells in mice brains at RCSI for so long, she became curious about how this could be of bene t for humans and how she could be involved in these processes.

A er graduating from RCSI, she took a decision to return to Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster to study medicine with the aim of becoming a neurosurgeon. Eva is now a resident physician at the clinic for neurosurgery in Münster, and her research interest has shi ed towards brain tumour treatment. Her research has been published in various academic journals and she has presented her work at a number of international conferences.

Eva says that RCSI taught her to never give up on ideas, research interests and long-term goals, even when nothing seems to work and experiments don’t show the hoped-for results. “My years at RCSI proved to me that there will always be a colleague to speak to or a discussion to have that will give you a new perspective so you can move on with your work.”

anks to her degree from RCSI, Eva was able to work in research during her medical studies. “I was able to work and support myself, thanks to this experience. is award means a lot to me. It demonstrates how hard work will be recognised and honoured when the time is right and it always pays to give the best you can. It brings back very good memories of RCSI, the good friends I made and the beautiful country I was able to live in for that time.”

DR BENJAMIN

LA BROT School of Medicine

Ben, founder and CEO of Floating Doctors, is a Southern Californian, who from childhood, has had a deep connection with the ocean, spending countless hours on (or under) the water o the coast of Southern California.

Ben is the President of RemoteCare Education. providing training for clinicians to practice international medical relief. He is Professor of Global Medicine at the Keck School of Medicine UCLA, and a Clinical Professor at University of California, Irvine Medical School, and an FDA Compliance Advisor for Roche Pharmaceuticals.

A er graduating, Ben worked in the Irish healthcare system before private medical mission work in developing countries led him to combine his love of the sea and medicine. He founded the Floating Doctors in 2009, to bring medical services to remote rural communities. In 2010, he led the rst Floating Doctors mission to Haiti.

“Everything I have done in my career is the result of having gone to RCSI. One of my Norwegian classmates suggested I visit East Africa. It was on that trip I decided to pursue a career in international medicine. At RCSI, we were trained in a public healthcare setting with conscientiousness about resources. I had been told that the clinical skills emphasised at RCSI would be extraordinary: that turned out to be true. I will forever be indebted to RCSI. e collective level of excellence pushes you to do well; RCSI alumni go on to do some pretty extraordinary things.

“I feel incredibly humbled and grateful to have been able to add anything at all to the long list of amazing accomplishments by RCSI alumni over the past 200-plus years. Of course, now I feel like I have a lot to live up to, so I’m going to consider everything we’ve done so far just the warm-up for our ambitions in the years to come!”

In 2007, Subashnie graduated from RCSI with an MSc in Healthcare Management and in 2014, received a PhD from Edinburgh Business School. She is President of the American College of Healthcare Executives, and the Director of Accreditation, Enterprise Quality and Patient Safety at the Cleveland Clinic, Ohio, USA. Since acquiring her BSc in Physiotherapy from the University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa, in 2007, her research on reducing the knowledge gap in healthcare quality and patient safety has been recognised internationally. In 2017, Subashnie received the Harvard Medical School Certi cate in Safety, Quality and Informatics Leadership (SQIL). Subashnie developed a robust analytical methodology to evaluate the impact of quality interventions, such as accreditation. is has been replicated in healthcare environments around the world, including Denmark, Brazil, Saudi Arabia, Hungary, Turkey, Australia, Jordan, Rwanda, United Kingdom, and the US. In addition to her role at Cleveland Clinic, Subashnie is an International Consultant with the Joint Commission and a speaker at international conferences.

“A truly remarkable aspect of RCSI, apart from the superb education, is that RCSI is for life,” says Subashnie. Subashnie recalls Professor Ciaran O’Boyle’s lectures at RCSI and his ability to make the complex, simple. She remembers how she later encountered Professor O’Boyle when he was appointed as an external examiner in Edinburgh, where Subashnie was completing her PhD: “He provided exceptional academic guidance, read my entire thesis, adding notes in the margin as to how it could be improved, and gave excellent feedback. is made me realise that I am still very much a part of RCSI, even 14 years a er graduation. RCSI has this incredible ability to connect students and graduates across the world.”

When a traditionally routed career path takes a twist anything can happen. Six alumni share their distinctive stories

Aer graduation, like most of my classmates, I headed to Beaumont for my intern year followed by two years as an SHO, with some “out” rotations in Letterkenny and Cavan. During that time I spent quite a bit of time in the emergency department and decided that was the area in which I wanted to specialise. I was planning to go to Chicago to train and then someone suggested Australia. Almost overnight it suddenly seemed an option worth thinking about – with a very similar health system to Ireland but better weather. I arrived in 2001, with the intention of staying only as long as it took to get my Fellowship sorted out, be appointed as a Consultant and then go home. at plan completely fell apart and I’m still here.

My rst job was in Liverpool Hospital, New South Wales and I did all my emergency training there, with a couple of “out” rotations. I completed my Fellowship in 2008 and a second in intensive care in 2010. en I moved to the job I hold now in Wollongong Hospital, an hour south of Sydney, where I’m an Intensive Care Consultant.

When I was a medical student on elective in Malaysia, I had the opportunity to tag along with the medical team at a motorsport event. I spent the day hanging out in a rubber plantation, avoiding snakes, eating roti and curry, watching fast cars at what I think was probably a stage of the Asia Paci c rally. It was pretty good, and back in Ireland I started to do the same at Mondello Park, a few forest rallies and at the Donegal rally, hanging out with the paramedics and occasionally getting paid 50 quid. At that stage I’d started to watch Formula One – I knew I would never be a driver but to be involved in some capacity became a thing I thought I would like to do. Once I got

settled in Australia I got online and tracked down the doctor for the stage of the World Rally Championship held in Perth and asked if I could join in, and I’ve been involved here ever since.

I’ve now spent the best part of 20 years being a Medical O cer for everything from club motorsport events to international events and long distance endurance events. For the last couple of years I’ve been Deputy Chief Medical O cer for both the Formula One in Melbourne and the World Rally event in Co s Harbour. I usually do between six and twelve events each year, including at my local track Sydney Motorsport Park in Eastern Creek. ere have been fewer events due to COVID-19 but they are coming back now, although with fewer spectators.

Motorsport has changed a lot over the years. When I started, I was going to a lot more incidents, with a wider range of injuries and illness, but there has been a lot of engineering work done on the safety features of the cars, as well as on helmets, re suppression systems, and driver conditioning. At the top tiers of motorsport, competitors now have a much better chance of walking away from a big crash without major injury than any time previously, though the gap between having no injury and not walking away at all is much narrower. ere is a wider range of potential for injury at the lower tiers where the cars can be older or the safety equipment less well developed.

More recently, for relaxation outside of work and motorsport, I play the drums in a band with some friends – some of whom are medics. We don’t have a name yet but we have been practising for the last six months and we’re getting to the point of thinking we might take the next step and play in front of a few people. I’m not sure if my kids think this is a good idea, though.

“AT THE TOP TIERS OF MOTORSPORT, COMPETITORS NOW HAVE A MUCH BETTER CHANCE OF WALKING AWAY FROM A BIG CRASH WITHOUT MAJOR INJURY THAN ANY TIME PREVIOUSLY.”

After graduating from RCSI, I stayed in Ireland to specialise in Anaesthesia, training mainly in Dublin. In 1994 I went to Toronto to sub-specialise in General Cardiac Anaesthesiology and in 1996 took up a post as Consultant Anaesthetist at Kings College Hospital. While I was in London, I met my husband, Christopher Roberts, and in 2007 we returned home to Sierra Leone, a er the war.

I took up a position as Head of Intensive Care at Connaught Hospital. ere is a shortage of anaesthetists here and one of my priorities has been to support and develop a pre-existing training programme for nurse-anaesthetists to provide anaesthesia services in rural Sierra Leone, which is particularly vital for women, who are at risk of greater morbidity and sometimes mortality. e programme to train nurse-anaesthetists is on pause at the moment as we are trying to move from a diploma to a degree course. I am busy putting together a new curriculum to start in October 2021, alongside a curriculum to train critical care nurses, as we don’t have a course here and currently we have to send people away to train in Ghana and Nigeria. We hope to take on ten nurse-anaesthetists who have graduated from the present diploma course, and eight to ten critical care nurses. In the rst semester there will be some commonality between the two courses, and then we will send them out for further training. With my colleague Dr Eric Vreede from e Netherlands, who I rst met at our post graduation ceremony in 1994 at RCSI, we are also preparing three residents in anaesthesia for their Primary exams in April. As well as my work in anaesthesia and medical education, I have, together with my husband Chris, founded a business, Morvigor Sierra Leone, making tea from the leaves of the moringa plant. I rst heard of it by chance, as it is

used in East Africa as a natural method of water puri cation. e leaves are full of vitamins, minerals and antioxidants and help to prevent malnutrition, which is still endemic here especially in the underves. We also prepare tea infusions and powders that we are exporting to the US and UK. ey are in all the supermarkets here too and going quite well, children take it as a nutritional supplement. It’s not a big business but it is growing!

“THE MORINGA PLANT... LEAVES ARE FULL OF VITAMINS, MINERALS AND ANTIOXIDANTS AND HELP TO PREVENT MALNUTRITION.”

I am a very busy person but having good people around me to help is key; once you have good people you try to train your staff and it’s a continuous process in which you play a supervisory role. I go examining for the West Africa College of Surgeons twice each year in Nigeria and Ghana, but I don’t do on-call from the hospital any more, only from home. My husband takes care of a lot of the business side of things. Outside of this I have a full social life, and am involved in my church – you can’t help but be involved when you are back here. It is good to do good.

“WE ALSO SEE A LOT OF GEOTHERMAL BURNS FROM HOT POOLS.”

Deirdre Seoighe was on maternity leave with her three-month old son, Ruadhán in 2019, when New Zealand’s Whakaari/White Island volcano erupted with 47 people on the island. Some died instantly, while others were injured, many su ering severe burns. e nal death toll was 22 people.

Aer graduating, I did the BST and then SpR training in plastics. I worked as a locum consultant in Galway, then lived in New York and came to the National Burns Unit at Middlemore in Auckland for Fellowship in 2016. I was appointed to a permanent consultant position in Hamilton, in the Waikato region, in 2017. I moved for love – I’m married to Joe Baker, an Orthopaedic and Spinal Surgeon, who’s from New Zealand.

I love the burns side of plastics. e patients tend to be from poorer socioeconomic groups and many have lifelong injuries. ey have to live with the impact and rami cations of those, I nd it awe-inspiring the way they get on with life, maybe not quite as before but with a great deal of courage.

Waikato where I work is the biggest hospital in New Zealand, it’s a busy Level One trauma centre serving a population of nearly one million. e Taupo Volcanic Zone lies within our catchment area, this includes several active volcanoes. We also see a lot of geothermal burns from hot pools. I y to Gisborne on the east coast of New Zealand every fourth week and do an operating list and a clinic. We provide a service over a huge area, much of it quite remote so many major traumas are choppered in to us.

Ruadhán turned three months on the day of the volcano. I was taking the older kids to their singing lesson and my husband texted to say there had been a volcanic eruption. I rang in to work, and they said they were expecting casualties and one of the consultants in the ED said, “I think you need to come in.” I wasn’t due back from maternity leave for another four or ve months and was still breast-feeding. I hadn’t bothered introducing a bottle so I couldn’t leave Ruadhán with anyone else because he’d starve. I le the other kids with the babysitter and I went in. We didn’t know what we

were expecting but we were ready and waiting. Someone took the baby from me and said she would let me know when he cried; Waikato is one of these places where they just cope.

Initially we took eight patients, all with serious injuries. We didn’t know their names, ages or nationalities. We operated on all eight that night, nishing at four in the morning. I went home with the baby and came back in for seven the next morning. e hospital management gave Joe leave at short notice to balance my coming in o leave.

e thing about burn injuries is they are very labour intensive. You need a big team in theatre, and the temperature needs to be turned up to 36°C so it’s very hard on sta . You want to do the work quickly and e ciently so the patients don’t lose heat or blood. And you have to operate and do changes of dressings every second day for each patient.

I am the only dedicated burns surgeon but we have six other plastic surgeons. e hospital decided I would oversee the clinical management of these patients. It’s very hard as a surgeon not to be hands-on – your instinct and training is to just get in there and do it all yourself. We had three theatres running at a time, and operated every day for two weeks solid. For four or ve days we had eight patients, then two Australians were airli ed out, two went up to Middlemore, and two unfortunately died. We were le with two, but even two meant operating every day for two weeks. You can only chip away at burns until they heal. ose last two patients stayed for months. ere is really good social medicine in New Zealand, so if you are in an accident all your treatment is covered until you are fully treated. I kept operating until all the burns were o and the new skin was on. We achieved that on Christmas Eve and I went home to Ireland on 26 December. It was a real team e ort with so many people from di erent areas of the hospital helping out.

At school, I was con icted by my love for maths and all things analytical versus a huge interest in science and the humanities (my English teacher told me I was an “unusual case” – I think it was a compliment!). My career started when I joined Irish Life as a trainee actuary when I was 17 and I quali ed as an actuary there. I practised as an actuary for about 15 years, with a break to take a degree in mathematics at Oxford University. is work was largely focused on the nancial services industry. It was a great experience but for me there was something missing so I re-evaluated and decided to return to complete graduate entry medicine in RCSI. I graduated in 2014. I absolutely loved studying medicine for four years and bene ted from the wisdom of some great teachers and mentors. In fact, a er I completed my intern year in Beaumont Hospital, I went back as a clinical lecturer in Connolly Hospital, Blanchardstown, largely focused on lecturing the second year of the GEM programme.

When I was in RCSI I didn’t really know where I was going to end up and that was part of the excitement and intrigue of the journey. I had a huge interest in medical oncology, and working with Professor Liam Grogan and the medical oncology team in Beaumont Hospital was the highlight of my clinical career. I spent some time hoping to pursue a career in medical oncology. However, I was always aware that I had a complementary skill set and wondered about the possibility of combining my two professional lives. I am passionate about medicine – especially innovation in medicine – and healthcare, but I also love turning my mind to complex problems. e determining factor in the direction of my journey was the fact that I had my son in nal med and once I had completed BST, it became apparent to me both from a lifestyle and nancial perspective that it would be impossible to pursue my medical oncology dream. It was a very di cult decision – medical training pathways are typically traditionally routed and don’t easily allow for family life, especially at the early stages. I know that progress is being made in this area and I was supported in my clinical journey as much as was possible within the constraints of the system. Both Professors Seamus Sreenan and John McDermott in Connolly Hospital Blanchardstown were particularly supportive.

In 2018, I took on a new role and challenge with EY’s consulting practice. I hoped to combine my two professional lives. It is fair to say that this has been more than realised.

“THE COMBINATION OF BEING AN ACTUARY AND A DOCTOR HELPS ME TO BE A LEADER IN THIS AREA.”

I work in the eld of health analytics. is essentially relies on mathematical modelling of any and all relevant variables from the whole system to individual patient level factors. We are all familiar these days, for example, with some of the epidemiological concepts that drive the pandemic. My role for the last year or so has been to largely support an understanding of the practical implications of these factors for the demand and provision of healthcare in this country – from both a COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 perspective. ese are complex and largely novel challenges and I hope and believe my ability to combine deep analytical rigour with clinical understanding and insights have helped some of our key decision makers. e work is fascinating.

e work is essentially an evidence-based approach to planning which helps inform strategic and operational planning. It is signi cantly actuarial in nature, which the health domain hasn’t adopted extensively in the past; its value is more appreciated now. ere is a huge opportunity for the advancement of health analytics due to the accelerant factor of the pandemic. e opportunity to optimise population and individual health outcomes is rst and foremost, but this sort of evidence based approach is more far-reaching. We can save taxpayers’ money by embedding premium quality quantitative analysis of expected outcomes as part of the planning cycle and basing decisions on this.

I greatly enjoy the technical aspects of the work. I am also passionate about its communication to key stakeholders. One of the main challenges of my work is to translate complex concepts into simple messages – to me the work is only as good as this step and I work hard to try to ensure that the messaging does justice to the insights generated. e work may be complex, but the messages delivered are best if they can be distilled simply.

e work is specialised and the combination of being an actuary and a doctor helps me to be a leader in this area. None of us ever wanted this to happen, but a pandemic of this nature was a mathematical certainty given how we exist on this planet. It will happen again and it is likely that it won’t be another hundred years. Hopefully we will have learnt valuable lessons this time round – both in terms of future prevention and management.

I miss patient contact and in some ways this has been accentuated by the pandemic, knowing the stress and strain on my clinical colleagues. Ideally in the distant future, I would like to think I can return to some degree of this. However, I love what I do now – I am absolutely passionate about the opportunity for health that this type of work presents. It certainly gives me purpose in getting out of bed every morning.

PhD in Chemistry from the National University of Ireland, PhD, BSc. FRSE, FRSC, CChem, FICI, FCSFS, FFireInv, Professor of Forensic Science, University of

Iwas one of the rst chemistry PhD students at RCSI, arriving in the College in 1989 a er an undergraduate degree in applied science (chemistry and mathematics) at DIT Kevin Street.

My doctorate was in the eld of bioinorganic chemistry. I worked under Professor Kevin Nolan and a second supervisor from UCD. e area was interesting to me because it was connected with medicinal applications, something in which I had a side-interest.

Towards the end of my research, I spent a year working for a Trinity spinout company involved in environmental monitoring and in 1994 applied to Strathclyde University in Glasgow for a lecturing post in the forensic science unit. My parents were the rst private practice consultant re investigators in Ireland, so I grew up having an understanding of the importance of forensic science.

My initial contract was for two years, but I am still in Scotland nearly 30 years later, having worked my way up the academic ladder here, attaining my Professorship in 2011, the rst female Professor in natural sciences in Strathclyde’s history.

In 2014, I moved to the University of Dundee where I am the University’s Professor of Forensic Science, and within 18 months had, with my colleague Professor Dame Sue Black, landed the biggest grant ever awarded (£10m) to forensic science in academia in the UK. What I do now is lead the Leverhulme Research Centre for Forensic Science, which is unusual in that it is funded to undertake disruptive research, to look at the whole ecosystem of forensic science and see where a profound disruption needs to occur in order to shi the culture, focus or mindset of that ecosystem to a better place. For the rst time, we have brought scientists, law enforcement, legal colleagues and the judiciary together to discuss openly the challenges we have all faced in ensuring that evidence presented in the courts is robust and scienti c.