11 minute read

IDOLS & THE EXPRESSIVE IMAGE

Page 65: William Turnbull in his studio in Hampstead, 1959, Photograph by Kim Lim Page 66: William Turnbull Tate retrospective, 1973, Photograph by Kim Lim, Left to right: Totemic Figure (1957); Female Figure (1955); Idol 1 (1955); Idol 4 (1956); Standing Female Figure (1955) and Screwhead (1957)

Advertisement

Expanding on the theme of the head, in the mid-1950s Turnbull began what was to be an extended body of sculpture, which continued into the early-2000s, on the theme of ‘Idols’ and ‘Standing Figures.’ These full-size bronze figures, which were invariably vertical and freestanding, were representations of divine beings. Soon afterwards, within his painting, Turnbull began to remove the figurative references present in his earlier head paintings, taking them in a new, more abstract direction which developed in dialogue with the sculpture he was now making.

Highly distinctive, yet also depersonalised, Turnbull’s figures have faces devoid of descriptive detail. In the leaflike figure, Paddle Venus 2 (1986) (cat no.30) for example, the slightest suggestion of the bridge of a nose is enough to convey the sense of a face. Height, then, becomes a defining characteristic, particularly as the forms themselves are often very slender and flat. Smaller than lifesize, Female Figure (1955) (cat no.21) stands at around 120 centimetres tall, while Idol (1988) (cat no.31) the tallest, towers 80 centimetres above it. While the forms are recognisably, and emotionally, human, the lack of figurative detail grants them a more symbolic function, suggesting ritual and worship. As David Sylvester put it, ‘There’s a quality in some of Turnbull’s figures which creates an expectation that, if some of them were placed in a simple well-lit building, it would become a temple.’ 12

Unlike Turnbull’s heads where gender is unclear, all of the figures in this group are identifiably female. Their bodies often include breasts, which in three of the works are sculpted and in two others are drawn onto the surface as triangles. In Standing Female Figure (1955) (cat no.23), a long ponytail falls to one side of the figure’s head and in Idol (1988), long hair is denoted more subtly by repeating vertical lines scored into the back of the head. These sculptures, which feel, simultaneously, ancient and modern, demonstrate Turnbull’s interests in pre-history, non-western cultures and 20th-century abstraction and this is reflected in their titles. Aphrodite (1958) (cat no.24) and Paddle Venus 2 (1986) refer to the Greek and Roman goddesses of love, fertility, prosperity and victory and their forms to Cycladic art; while War Goddess (1956) (cat no.26), Totemic Figure (1957) (cat no.27) and Aphrodite (1958) are stacked up like carved African totems. Turnbull’s work in the 1980s focused, for the most part, on heads, masks, tools and upright figures, as we see reflected in the silhouette of Paddle Venus 2. The archaeological, ‘dug-up’ look of the earlier works is developed in this decade through a number of blade and spade forms – some small, others large – that carry the aura of ancient cultures and the ground beneath them.

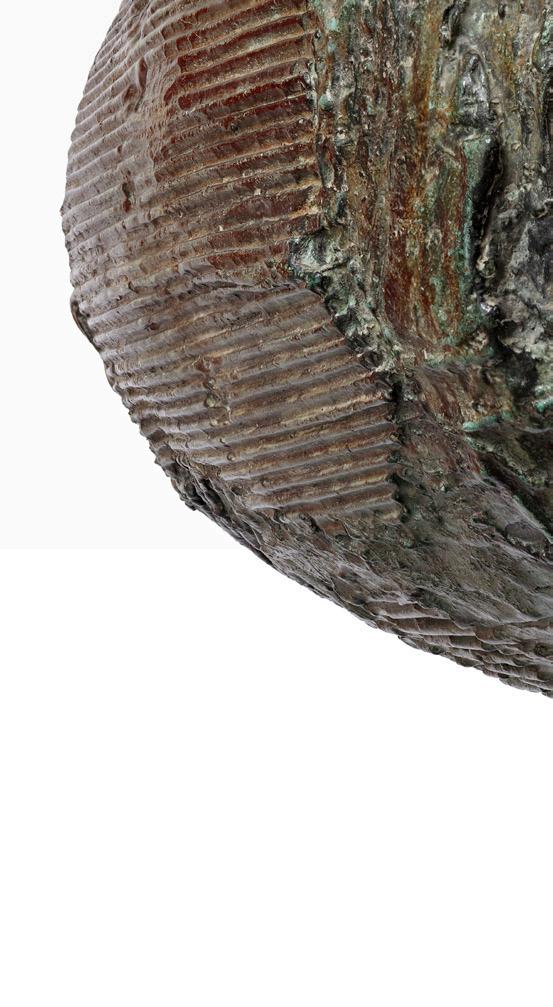

Turnbull made these figures by building up plaster over a metal armature, before modelling the surface to varying degrees, and casting the final form in bronze using the traditional lost wax technique. Turnbull took pleasure in the improvisational possibilities of working into wet plaster. He declared, ‘I used texture to invoke chance, to create random discoveries, not to elaborate the surface, but to accentuate that it was a skin of bronze.’ 13 In Female Figure, Standing Female Figure and Aphrodite, he has impressed corrugated paper into the wet plaster in different directions, creating a rich patchwork of textures which give the impression the figures have been battered, brutalised or even resurrected from the earth. In contrast, War Goddess, and later works Paddle Venus 2 and Idol have smoother surfaces, on which we see inscribed Turnbull’s characteristic wobbly lines and imperfect patterns of dots.

In the exhibition catalogue for the artist’s 1957 solo exhibition at the ICA, Lawrence Alloway describes how:

‘Turnbull responded to the surface of his solid sculptures with a sense of discovery that traditional sculptors, to whom sculpture was anything but solid, can rarely feel. Since he was a modeller working with a soft material it was natural for him to think of the surface as a receptive plane, inviting inscription and elaboration, like wet sand on the seashore or a wall in a city. He used the surface of his sculptures to record in dramatic textures and marks the events of the creative act.’ 14

Turnbull always paid close attention to the finish of his bronzes. In the early years he would colour the bronzes himself, later on he supervised their patination at the foundry. He sought to create new experiences of the same form by varying the patinations within a single edition. There are wonderful variations across the idols presented here – from dark brown, to lighter ochre-brown and iron-red, through to pistachio and aquamarine. These sculptures have rich and multi-faceted surfaces with hints of underlying colours showing through.

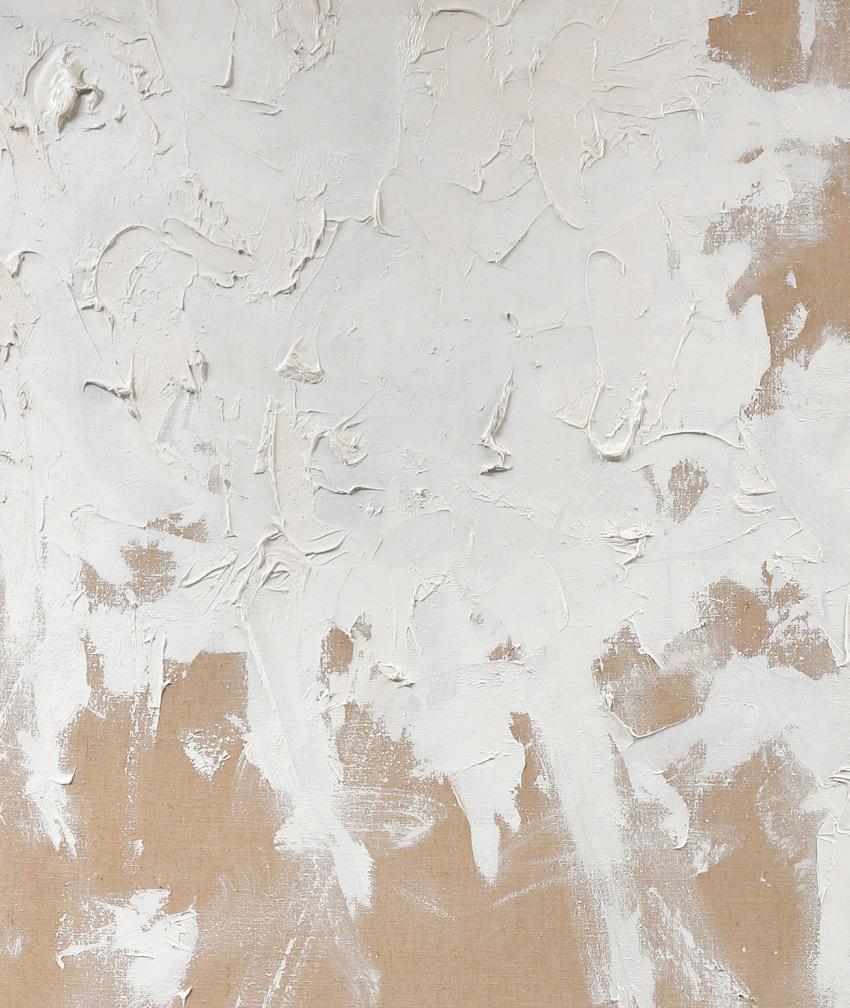

The textures and tonal variations within these bronzes find their equivalence in the large canvases Turnbull was making in the 1950s. Alloway outlines this affinity, stating ‘Painting is as physical a business as sculpture now that painters recognise the specific properties of paint as contributing to the work of art. Turnbull’s paintings, with their clear stress on the skin of paint bearing the brush or knife mark, thus extend the sculptor’s recognition of the reality of his materials into painting. ’15

In the 1950s Turnbull was keenly aware of current artistic developments in America. In 1953, the Museum of Modern Art in New York established its International Program, an initiative to send MoMA exhibitions around the world to cities including London, which meant that British artists and the wider public became increasingly exposed to exciting transatlantic developments. In 1956 the Tate staged the landmark exhibition Modern Art in the United States: A Selection from the Collections of the Museum of Modern Art, which included a room devoted to Contemporary Abstract Art which divided critics. Inspired by what he saw, in 1957 Turnbull flew to North America where he met first-hand three figures at the forefront of the Abstract Expressionist movement: Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman and Helen Frankenthaler.

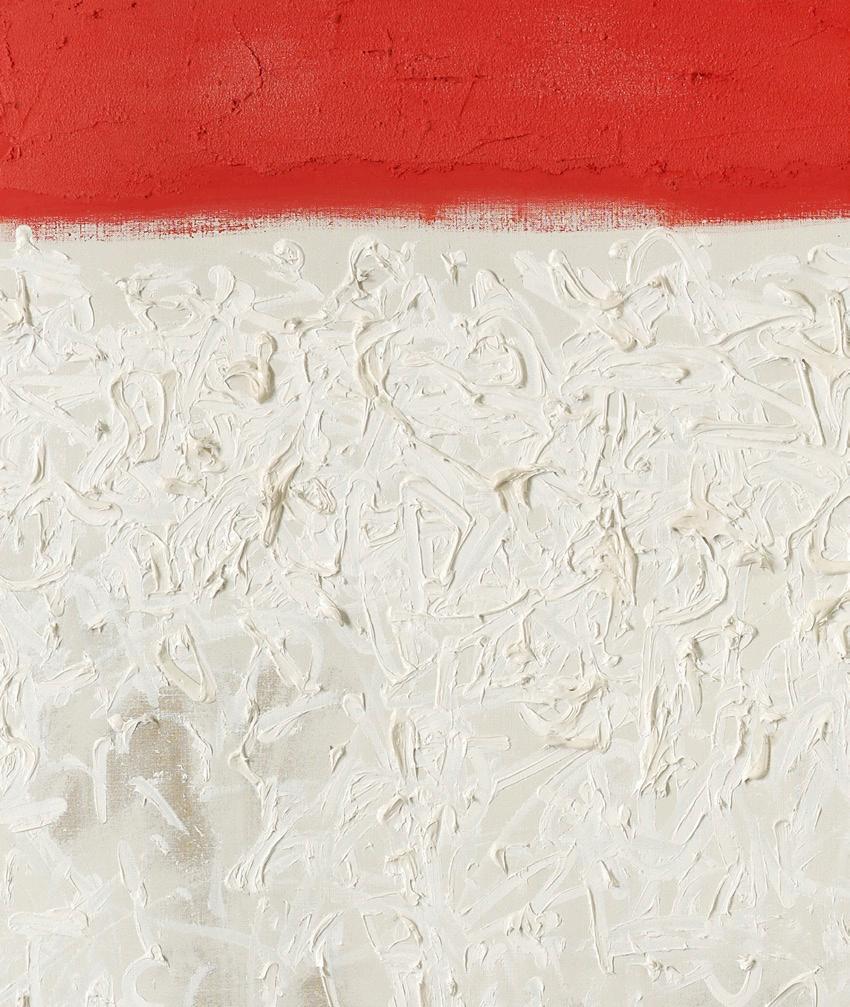

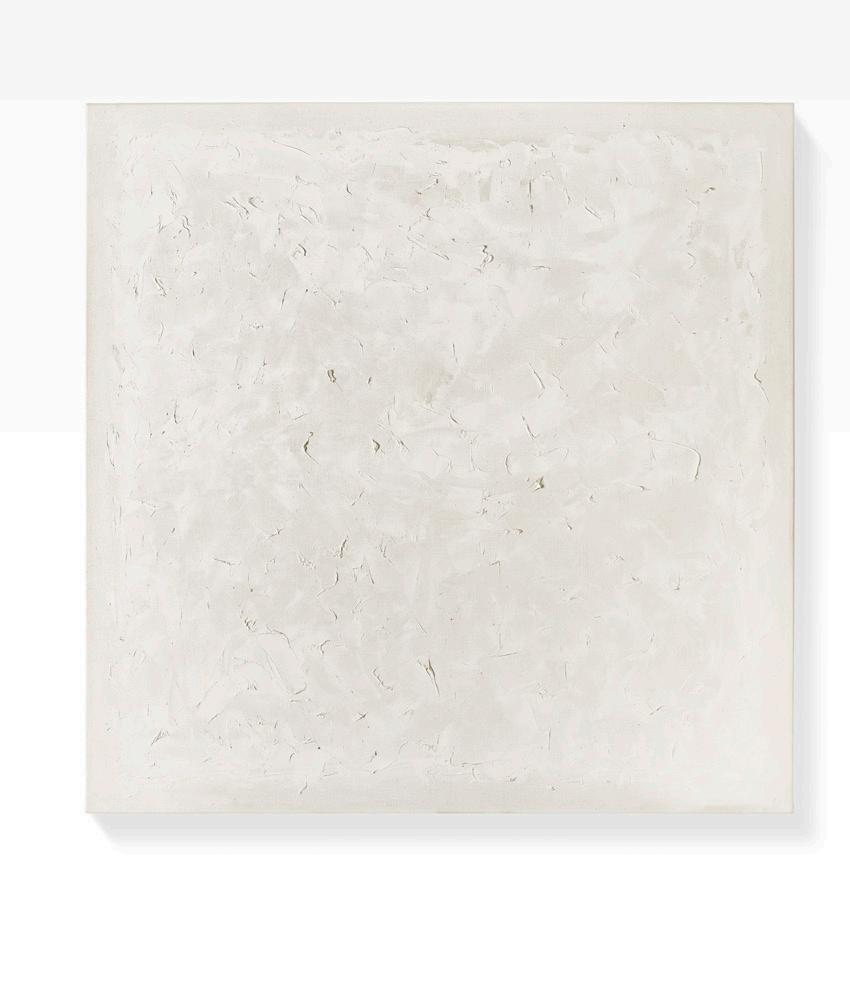

Back in London, in 1958 the ICA exhibited paintings by Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still in its exhibition Some Pictures from the E.J. Power Collection. The Whitechapel Gallery also played an important role in bringing American art to Britain, by holding a series of solo exhibitions of American artists, beginning with Jackson Pollock in 1958. Turnbull’s own paintings increased in size, as he strove for ‘a dynamic between the painting as object and as surface experience’. He reduced his palette, creating monochromatic or duochromatic abstract paintings including Landscape (1957) (cat no.25), 10-1958 (1958) (cat no.22), 5-1958 (1958) (cat no.29) and 29-1958 (1958) (cat no.28), which focused on a small number of formal concerns – line, shape, form, tone and texture.

This group of paintings suggest a range of influences. The scarlet red band at the top of Landscape recalls the bands of colour in Rothko’s paintings, while the scratchy white brushstrokes recall the gestural marks of Jackson Pollock’s and, also, Japanese calligraphy. Turnbull had been exposed to eastern culture first through his travels as a pilot in the RAF (1941-46) and, later, his relationship with the Singaporean sculptor Kim Lim, who he married in 1960. Turnbull used calligraphic mark-making in various paintings, including his series of black and white head paintings from 1955 (cat no.20).

The title of the notionally abstract work Landscape refers to the landscape tradition, but Turnbull’s entry point was not the land as seen at ground level, but rather as experienced from above. The time he spent flying planes in the RAF offered a radical new perspective on the natural environment and fundamentally changed the way he saw the world, as he explained:

‘The main thing about flying for me was the fact that the world didn’t any longer look like a Dutch landscape; it looked like an abstract painting. You looked down and you realised that so much of what one felt was true depended on where you were standing to look at it... this experience of having three different fields of movement, where you’ve got up and down and sideways...You have an extraordinary spatial feeling, and there are certain aspects of it that are very primitive...There was this sense at night where you feel you are flying away from the world, this flying into a kind of blackness.’ 16 17

With its sweeping, gestural marks 10-1958 is a painting alive with movement, energy and emotion. Comprising a single colour over an unmodulated white ground, Turnbull’s turbulent indigo brushstrokes suggest forceful winds, the ocean and the night sky. Executed across three large canvases and measuring nearly four and a half metres wide, this painting has the hallmarks of an Abstract Expressionist painting.

12 David Sylvester, ‘Introduction: Bronze Idols and Untitled Paintings’, William

Turnbull, Sculpture and Paintings, exh. cat., Serpentine Gallery, London, 1995, p9 13 William Turnbull, Statement, in Theo Crosby (ed.), Uppercase 4, Whitefriars,

London, 1960, unpaginated 14 Lawrence Alloway in William Turnbull: New Sculpture and Paintings, exh. cat.,

The Institute of Contemporary Arts Gallery, London,1957, unpaginated 15 Ibid 16 ‘William Turnbull in conversation with Colin Renfrew, 6 May 1998,’ William Turnbull,

Sculpture and Paintings, exh. cat., Waddington Galleries, London, 1998, p7 17 The British painter Peter Lanyon, who was also a pilot in the war (and later took up gliding) was exploring similar themes at this time. When Turnbull was in

New York in 1957 when Lanyon had his first solo exhibition with the Catherine

Viviano Gallery.

LIST OF WORKS

Works available for sale are marked with an asterisk * Additional cataloguing for these works can found at the back of the book on pages 197–203 Works not included in the exhibition are marked with △

(page 76-77) |21 Female Figure (1955) △ bronze 121.3 × 41.9 × 34.9 cm stamped with the artist's monogram, dated and numbered 2/4 from an edition of 4 plus 1 AC (detail page 75)

(page 78-79) |22 10-1958 (1958) oil on canvas (triptych) 198.1 × 442 cm (overall) signed and dated on centre canvas verso

(page 80-81) |23 Standing Female Figure (1955) * bronze 160.7 × 36.8 × 40.6 cm stamped with the artist's monogram and dated AC from an edition of 4 plus 1 AC

(page 84-85) |24 Aphrodite (1958) bronze 190.5 × 73.7 × 50.2 cm stamped with the artist's monogram, dated and inscribed AC from an edition of 4 plus 1 AC (detail page 82-83) (page 86) |25 Landscape (1957) oil and sand on canvas 112.5 × 150 cm signed, dated, titled and inscribed ‘Winter’ verso; signed and dated again on canvas overlap (detail page 87)

(page 88-89) |26 War Goddess (1956) bronze 161.3 × 48.3 × 40.6 cm stamped with the artist's monogram, dated and numbered 3/4 from an edition of 4

(page 92-93) |27 Totemic Figure (1957) * bronze 152.4 × 43.2 × 35.6 cm stamped with the artist's monogram and dated 1/4, from an edition of 4 (detail page 90-91)

(page 95) |28 29-1958 (1958) * oil on canvas 152.4 × 152.4 cm signed, dated and titled twice verso

(page 96) |29 5-1958 (1958) oil on linen 152.4 × 152.4 cm (detail page 97) (page 98) |30 Paddle Venus 2 (1986) * bronze 198 × 36 × 30.5 cm stamped with the artist's monogram, dated and numbered 4/4 from an edition of 4 plus 1 AC (detail page 99)

(page 102-3) |31 Idol (1988) * bronze 201.9 × 60.3 × 40 cm stamped with the artist's monogram, dated and inscribed AC from an edition of 4 plus 1 AC (detail page 101)

|22 10-1958 (1958)