9 minute read

DRAWING IN SPACE

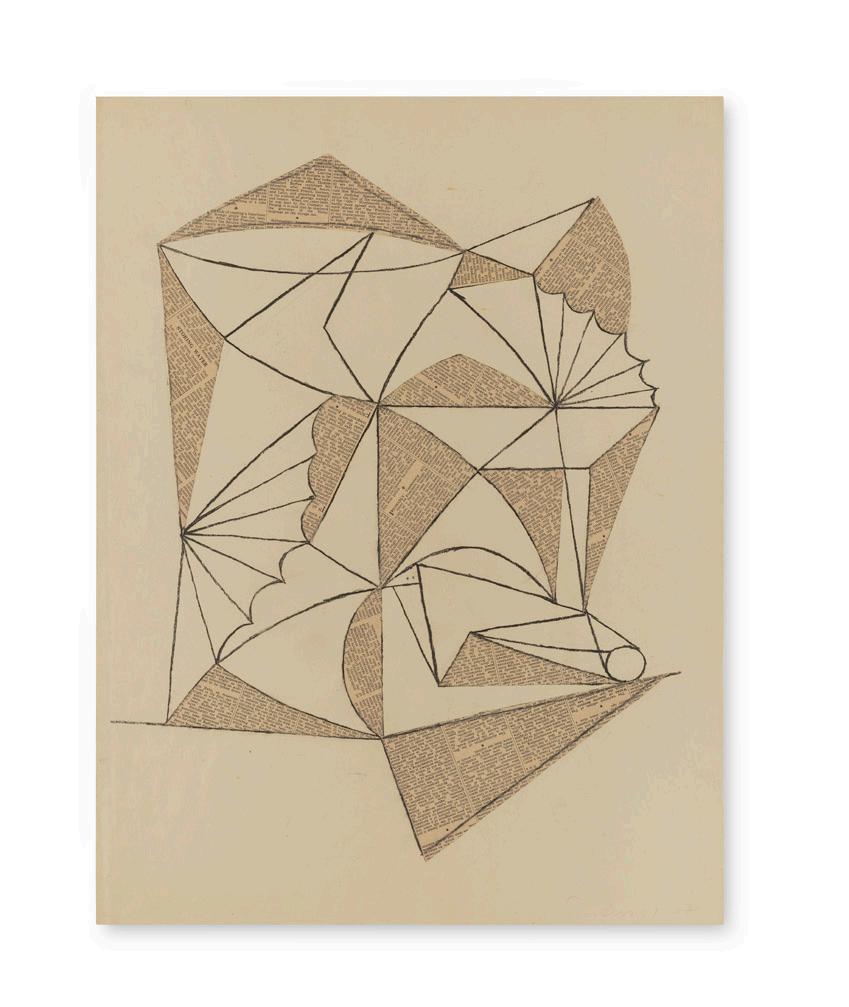

The sculpture, painting and works on paper here were all made by William Turnbull between 1947 to 1949. The two earliest works on paper – both titled Circus (1947) (cat nos. 7 & 8) and virtually identical in composition - include images of tightropes, tents and unicycles. One features bright yellow and purple paint, the other is in black and white and incorporates areas of newspaper collage within the charcoal lines, in a manner reminiscent of Picasso and Braque.

Advertisement

Four years on, Turnbull returned to this subject with the bronze sculpture Acrobat (1951), a figure whose attenuated limbs echo the linearity of the earlier works on paper. This figure, stood with arms out to the side and one leg on a unicycle, simultaneously conveys a sense of both movement and balance – a formal duality which became a major theme in both his sculpture and painting. Turnbull would have been aware of other artists who were using circus imagery in their work, including Paul Klee (1879-1940). In 1945-6, a year or so before Turnbull made his first works on paper, Klee had a major solo exhibition at National Gallery in London and Turnbull later cited his drawings as an important influence. 1 Turnbull may also have been inspired by Alexander Calder (1898-1976) who, after moving to Paris in 1926, created what came to be known as Cirque Calder, a sculpture comprising figurines of animals, clowns and acrobats, which he would ‘perform’, narrating the actions out loud, accompanied by music and lighting.

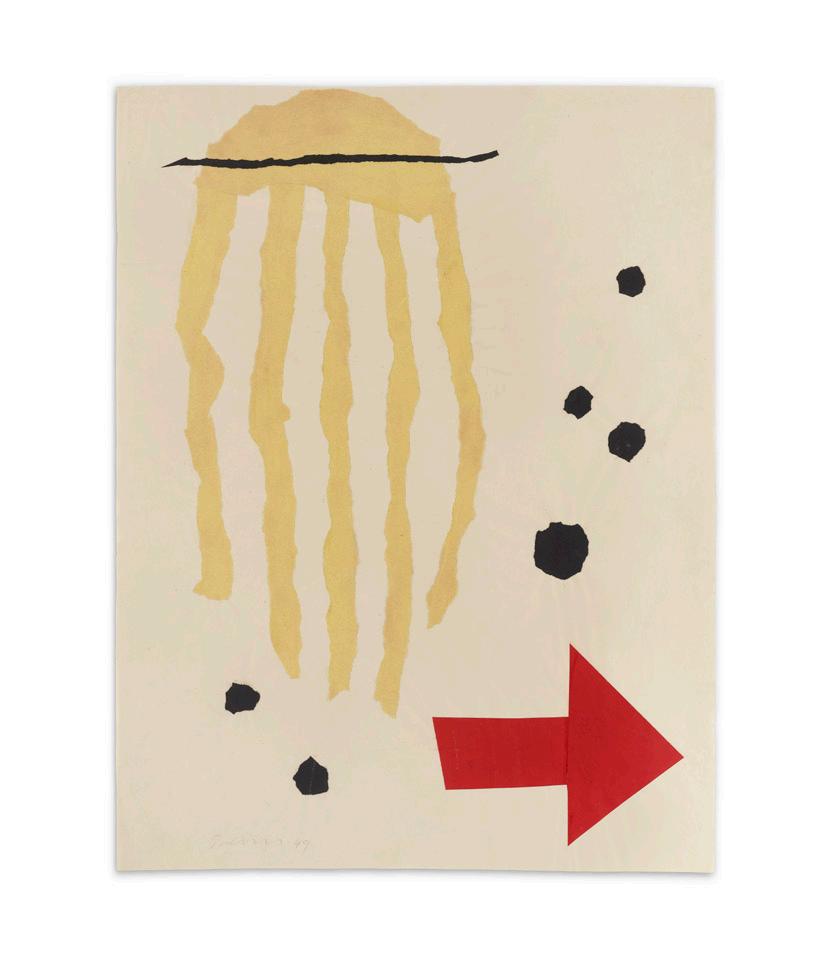

The wheel-like form seen in both the Circus drawings and Acrobat appears in two kinetic mobiles both titled Hanging Sculpture (1949), in which eleven fish dangle down on lengths of wire. Similar simplified fishes are found anchored to a base in the table-top bronze Aquarium, (1949) (Coll. Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art) as well as in a number of collages on paper from the same year, two examples of which are included in this exhibition (cat nos. 2 & 3). In these collages, jellyfish, shoals of fish and coral are combined with large arrows pointing in different directions, signalling rapid changes in movement.

Looking back later, Turnbull summarised his preoccupations at this time: 'I was very involved in the random movement of pin-ball machines, billiards (which I played a lot) and ball games of this sort; and the predictable movement of machines (in the Science Museum). Movements in different planes at different speeds. I loved aquariums. Fish in tanks hanging in space and moving in shoals. The movement of lobsters. I became quite expert with a Diablo. I was obsessed with things in a state of balance.' 2

‘I was fascinated with things moving and touching and perceptually convinced of energy as creation. The movement of insects, fish and plants seemed to be a making and breaking of contacts. Like a marvellous electrical system. The word most in my mind was “contiguity”. Perhaps it doesn’t express what I mean but it acted as a mnemonic aid. I wanted to make sculpture that would express implication of movement (not describe it), ambiguity of content, and simplicity (lack of interesting detail separate from the whole).’ 3

Aside from the Circus pictures, all the other works here were made in Paris, where Turnbull lived for two formative years between 1948 and 1950. He’d been inspired to move there by his friend Eduardo Paolozzi and before completing his final year at the Slade, requested a transfer to finish his studies at the Grande Chaumière Art School in Montparnasse. Turnbull wanted to 'escape the prevailing post-war Neo-Romanticism’ of British art at the time, which he found backward-looking and limiting. 4 During his time in Paris, he sought out the avant-garde artists of the day, including Constantin Brancusi (1876-1957) and Alberto Giacometti (1901-66).

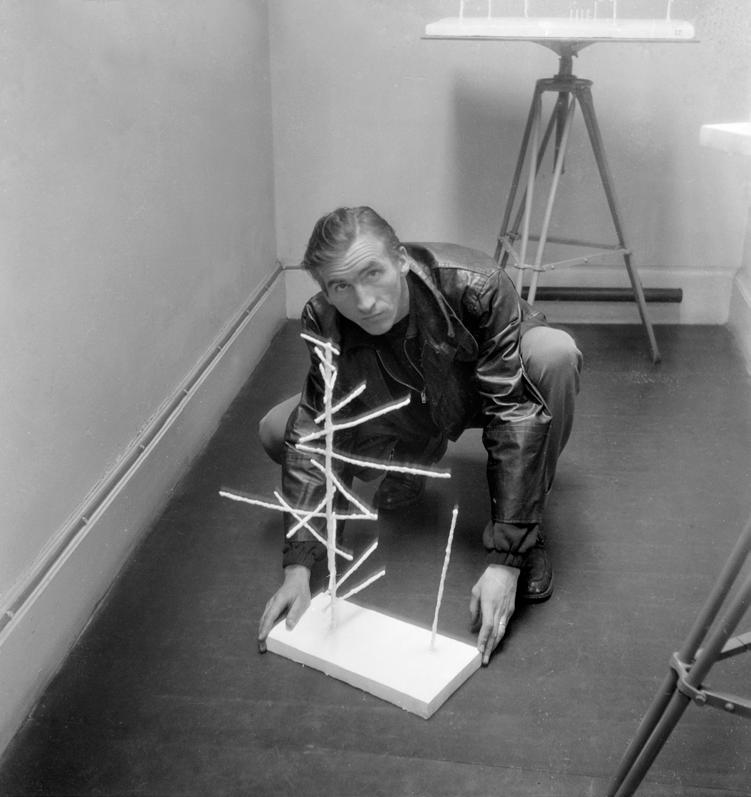

In 1949, partly inspired by the tabletop sculptures he’d seen in Giacometti’s studio, Turnbull began to make a series of sculptures where linear forms were connected to a slab-like base. These were constructed from fine wire armatures and then built up in plaster, some of which he was then able to cast in bronze. Forms on a Base (cat no.1), Torque Upwards (cat no.4), and Maquette for Large Sculpture (cat no.5) (all 1949) belong to this body of work. Although relatively modest in size, they were originally intended to be much larger – as indicated by the title Maquette for Large Sculpture. However, in this early period Turnbull couldn’t afford to pay for further casts at the same size or to realise his maquettes on a bigger scale. The lumpy surfaces and crude, uneven bases of these modelled forms emphasise that they are the direct result of the artist’s hand and evoke the studio as a place of creation. Few of Turnbull’s works from the 1940s have survived, many were destroyed either by the artist himself or as the result of having been left behind in storage in Paris after he returned to London at the end of 1950. As such, these three unique bronzes are extremely rare examples.

In each of these three sculptures numerous thin and irregular stick-like forms extend upwards from the sculpture’s base. The base forms an integral part of the composition, determining the relationship between the forms. Some of the vertically extending parts also feature other lengths which branch off horizontally or at an angle. In Torque Upwards these ‘branches’ cut into space in different directions, creating, as the title implies, the impression of a twisting force of energy rising up into the air.

Although ostensibly abstract, these three forms conjure a multiplicity of images rooted in nature and the man-made world. Torque Upwards has a skeletal quality reminiscent of a backbone and rib cage, while also conveying a feeling of rising movement reminiscent of flight. The wavering uprights in Forms on a Base recall both a crowd of moving people and a curious plant rising from the earth. In Maquette for Large Sculpture the variously spaced horizontal lengths call to mind one of Turnbull’s own notes detailing his interest in ‘Objects moving in relation to each other (aircraft in formation) – people in the Metro tunnels walking beside each other and towards one another.’ 5

Unlike in Turnbull’s Hanging Sculpture (1949), where the forms move freely in space, in these static works movement is only suggested. Turnbull pushed this idea further in another of his tabletop sculptures, Game (1949), where the pin-like uprights could be arranged in any permutation in the base, playfully introducing the active participation of the viewer and an element of chance into the work.

In 1950, Torque Upwards was included in the seminal exhibition Aspects of British Art at the ICA, and Turnbull also showed a selection of his work from Paris at the Hanover Gallery in a joint show with Eduardo Paolozzi and Kenneth King. 6 Opened by Erica Brausen in 1947, the Hanover Gallery became one of the most notable galleries in London, dealing in 19th and 20th century masters and contemporary British and foreign artists, including Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud and Alberto Giacometti. For Turnbull to have the opportunity to show his work at such a reputable gallery at this early point in his career was a significant achievement. Two years later, in 1952, Brausen gave him his first solo exhibition and in the summer he was one of the eleven artists included in New Aspects of British Sculpture in the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale.

In his section of the Hanover Gallery exhibition in 1950, Turnbull showed the original plasters for Maquette for Large Sculpture (cat no.5) and Torque Upwards (cat no.4) alongside those for Aquarium, Mobile Stabile (Coll. Tate, London) and Female Attracts Male (presumed destroyed) (all dated 1949). A series of photographs taken by Nigel Henderson which document the installation of the exhibition are a fascinating and useful record. They show the narrow space on the top floor of the gallery which Turnbull was given to display his work. In some images we see the artist crouching down, experimenting with placing the plasters directly on the floor, while in others we see their final arrangement, on three-legged modelling stands. In one particularly dark photograph, which is difficult to decipher, there also appear to be four paintings or works on paper, including one of the Aquarium collages (cat nos. 2 & 3), hung on the surrounding walls. It’s not clear whether these were included in the final hang, as they don’t appear in other photographs showing the plasters. In this 2022 exhibition, marking the centenary of the artist’s birth, we have returned to this important moment in the artist’s early career, basing our presentation of his early sculptures on Turnbull’s own vision for the 1950 Hanover exhibition.

1 Published in The Tate Gallery Report, London 1967: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/turnbull-mobile-stabile-t00903 2 William Turnbull cited in Richard Morphet, ‘Commentary,’ William Turnbull,

Sculpture and Painting, exh. cat., Tate Gallery, London, 1973, p26 3 The Tate Gallery Report, London 1967, Ibid 4 William Turnbull, in ‘Retrospective Statements,’ The Independent Group: Post

War Britain and the Aesthetics of Plenty, David Robbins (ed.), Cambridge, Mass,

London, MIT Press, 1990, p195 5 The Tate Gallery Report, London 1967, Ibid 6 The exhibition was organised by their mutual friend David Sylvester

Page 17: William Turnbull at the Hanover Gallery, 1950 Page 18: Turnbull with the original plasters for (front left to front right): Aquarium, Torque Upwards, Mobile Stabile, Female Attracts Male and Maquette for Large Sculpture (all 1949), at the Hanover Gallery, 1950 Page 21: Turnbull with the plaster for Torque Upwards (1949) at the Hanover Gallery, 1950

LIST OF WORKS

Works available for sale are marked with an asterisk * Additional cataloguing for these works can found at the back of the book on pages 197–203

(page 27-29) |1 Forms on a Base (1949) * bronze 33.5 × 50 × 44 cm unique

(page 30) |2 Aquarium (1949) * collage on paper 39.4 × 52.4 cm signed and dated

(page 31) |3 Aquarium (1949) collage on paper 54.4 × 41.3 cm signed and dated

(page 32) |4 Torque Upwards (1949) bronze 59.7 × 42 × 33.5 cm stamped with the artist's monogram and dated unique

(page 33) |5 Maquette for Large Sculpture (1949) bronze 58.5 × 47.9 × 37.1 cm unique (page 35) |6 Untitled (1949) * oil on canvas 76.2 × 50.8 cm signed twice, dated and inscribed 'Feb 1950' verso

(page 36) |7 Circus (1947) charcoal with newspaper collage on paper 68.6 × 53 cm signed and dated

(page 37) |8 Circus (1947) * mixed media on paper 56.5 × 71.1 cm signed and dated