Helping Texans make the best real estate decisions since 1971

Helping Texans make the best real estate decisions since 1971

Natural disasters are forecast to become stronger and more frequent this decade, affecting an increasing number of people and places.

Natural disasters are forecast to become stronger and more frequent this decade, affecting an increasing number of people and places.

Our new blog series helps inform Texans of the costs and consequences of natural disasters.

Our new blog series helps inform Texans of the costs and consequences of natural disasters.

A&M

TEXAS

UNIVERSITY Texas Real Estate Research Center

A&M

TEXAS

UNIVERSITY Texas Real Estate Research Center

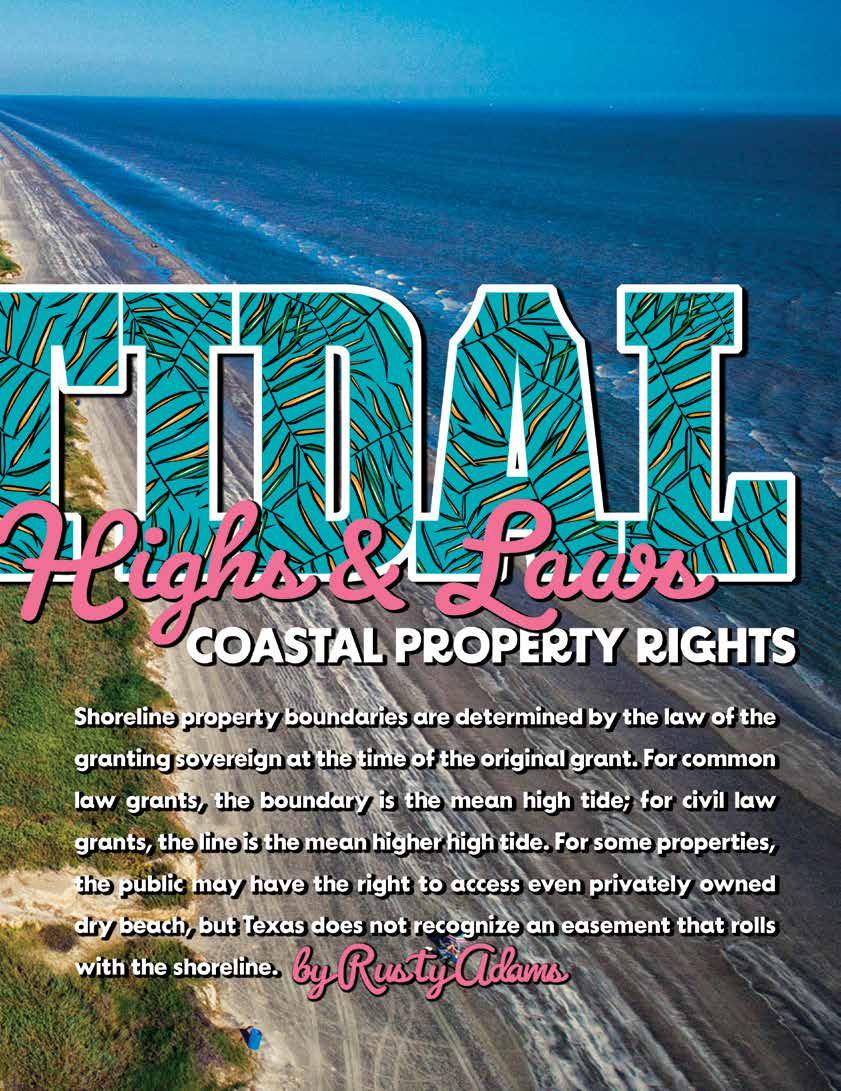

Take a break from the bleak midwinter and head to the beach for this look at how changing tides can impact shoreline property boundaries. By Rusty Adams

Transforming Commercial Real Estate

No, machines aren’t taking over the world. However, the lines between traditional office environments and technology-driven workspaces are blurring, spurred by the pandemic and an increasingly tech-savvy workforce. By Harold D. Hunt, Bucky Banks, and Steve Ramseur

An article in the summer 2022 issue of TG dipped its toe into common mistakes made in likekind exchanges. This follow-up piece does a cannonball dive. By William D. Elliott

COVID, Composition Effects, and Homebuyer Preferences

COVID changed how people look at the world. It also changed what homebuyers look for in a home. By Adam Perdue

Floor plans are popular when it comes to marketing a house for sale, but real estate professionals might be “floored” to learn that such use is a copyright violation in some states. Here’s what you need to know. By Kerri Lewis

Executive Director, GARY W. MALER

Senior Editor, DAVID S. JONES

Managing Editor, BRYAN POPE

Associate Editor, KAMMY BAUMANN

Creative Manager, ROBERT P. BEALS II Graphic Specialist/Photographer, JP BEATO III

Graphic Designer III, ALDEN DeMOSS

Communications Coordinator, HAYLEY WILEY

Circulation Manager, MARK BAUMANN

Lithography, RR DONNELLEY, HOUSTON

VOLUME 30, NUMBER 1 www.recenter.tamu.edu

2023 Texas Economic Forecast

Who needs a fortune teller when you have a team of economic experts like ours? They use their understanding of the many national and international factors that influence real estate markets to make educated guesses about 2023.

From

Since the onset of COVID, Texas land markets have had more ups and downs than the Hill Country. Learn more in our latest market analysis. By Charles E. Gilliland and Lynn D. Krebs

Take note: Paragraph 11 (Special Provisions) of a TREC promulgated sales contract can’t be used for just anything. Here’s what you can and can’t do. By Kerri Lewis and Avis Wukasch

ADVISORY COMMITTEE: Doug Jennings, Fort Worth, chairman; Doug Foster, San Antonio, vice chairman; Troy C. Alley, Jr., Arlington; Russell Cain, Port Lavaca; Vicki Fullerton, The Woodlands; Patrick Geddes, Dallas; Besa Martin, Boerne; Walter F. “Ted” Nelson, Houston; Rebecca “Becky” Vajdak, Temple; and Barbara Russell, Denton, ex-officio representing the Texas Real Estate Commission.

TG (ISSN 1070-0234) is published quarterly by the Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas 77843-2115. Telephone: 979-845-2031.

VIEWS EXPRESSED are those of the authors and do not imply endorsement by the Texas Real Estate Research Center, Division of Academic and Strategic Collaborations, or Texas A&M University. The Texas A&M University System serves people of all ages, regardless of socioeconomic level, race, color, sex, religion, disability, or national origin. Nothing in this publication should be construed as legal or tax advice. For specific advice, consult an attorney and/or a tax professional.

PHOTOGRAPHY/ILLUSTRATIONS: Robert Beals II, pp. 1 (top), 2-3, 4-5, 7, 10-11, 12-13, 18-19; Center files, pp. 1 (bottom), 8-9; JP Beato III, pp. 6, 14-15, 17, 25; Alden DeMoss, pp. 20-21, 22-23, 24.

LICENSEE ADDRESS CHANGE. Log on to your Texas Real Estate Commission account to change your mailing address.

© 2023, Texas Real Estate Research Center. All rights reserved.

When real estate professionals think about a robust tech sector, California is probably the first state that comes to mind. Surprisingly, Texas comes out on top in the number of tech jobs added and second in the number of tech businesses started in 2021 according to InnovationMap.

With nearly 800,000 high-paying tech jobs, Texas has provided real estate licensees with a continuous stream of companies that buy or lease commercial space. PropTech, an industry segment that is increasingly impacting how real estate is traded and operated, adds even more to the story.

PropTech represents the technology and innovation real estate professionals use to do their job. According to research by JLL,

investment in this emerging sector has increased by over 300 percent during the past ten years. A report from the Center for Real Estate Technology & Innovation noted that venture capital investment in PropTech nationwide reached $13.1 billion in the first half of 2022, up 5.7 percent from 2021. Considering the speed at which technology is evolving and how computers, artificial intelligence, and intelligent buildings interconnect everyday objects, real estate professionals in Texas face both opportunities and threats.

The intersection between the built environment and technology surged into the mainstream when the pandemic forced companies to address the future of work. Before 2020, technology was used to monitor, manage, and control access to building operations. Such practices are now status quo. Today,

Today’s workplace has been transformed by the pandemic and workers who are more technologically proficient than ever. This transformation has ushered in PropTech, an industry seeking to merge innovative technology with the commercial real estate industry. By Harold D. Hunt, Bucky Banks, and Steve Ramseur

thought leaders are pushing the envelope much further with 3D visualization and printing, robotic process automation, deep learning, and the metaverse. Real estate investors are viewing real property more in terms of the property’s advanced technology usage than just its physical space.

Just as fossil fuels powered the last industrial revolution, data now fuel the information economy. Real estate is notoriously opaque, with market knowledge creating a competitive advantage for those who possess it. Much of the information is collected manually and siloed within disparate systems. The industry also lacks standardization, and information is guarded fiercely in a business where knowledge is power. As a result, PropTech faces an efficiency crisis that has slowed its momentum.

Compare this with the efficiency of the NASDAQ, where over four billion shares often trade daily in a transparent marketplace. Participants share a common language and have immediate access to information and analytics to make sound decisions. Comparing the two industries, one sees the opportunity for data-driven technology to disrupt arcane real estate practices and create enormous profits for new entrants. Data are one of the most significant impediments to adoption, but creating the necessary data infrastructure is only a matter of time.

As with any emerging technology, the speed of PropTech acceptance is fueled by tech advancements in other areas. These include cloud computing, the “Internet of workplace things” (i.e., connecting electronic devices in the workplace

to the Internet, thereby connecting the devices to each other), open-source software, the sharing economy, and the proliferation of mobile devices. These make up the foundation on which PropTech is being built. However, future trends will accelerate PropTech acceptance.

One example is data fabric, which provides data across platforms available to those who need it. Another is distributed enterprise, a remote and virtual-first experience for consumers and workers to support products and work modalities. According to Future Market Insights, when advancements in financial technology (FinTech) are considered, PropTech is poised to become an $86.5 billion industry by 2032 (see figure above).

PropTech demonstrates a shift in mindset. Fifty-six million millennials are in the workforce, making up about 35 percent of the total. Born after Internet usage became commonplace, they will represent 75 percent of the workforce by 2025. Add an additional 53 million Gen Xers and the result is a labor force whose native language is technology. The shift in remote work during the global pandemic—along with environmental, social, and governance (ESG) priorities—will accelerate a broad transformation within the real estate industry. PropTech will be the catalyst and the beneficiary of this massive shift.

PropTech can be sorted into several buckets that describe the function of the technology within the real estate environment. Many PropTech applications are accessed via the Internet using software as a service (SaaS), which allows users to implement specific technology for a fee. This subscription-based model is low-cost, easy to use, and takes advantage of the information economy.

Another way to classify PropTech is by the technology sector it serves. Many companies help improve building operations with automated access controls, video surveillance, parking management, and building management systems. Others enhance energy management, improve transactions and portfolio management, and provide intelligent building solutions. Each technology solves a problem within that slice of the real estate industry to assist professionals in saving time and money while mitigating risk.

Two more significant real estate value chain contributors are data and capital. PropTech requires data to operate and capital

to grow. The capital investment in PropTech will come from angel investors, founders and entrepreneurs, venture capitalists, and limited partnerships. Many large traditional real estate companies, including Cushman & Wakefield, JLL, and CBRE, are entering corporate venturing by investing in innovative start-ups along with their core businesses.

Texas is home to 125 PropTech firms, ranking third nationally. Within Texas, Austin leads all municipalities with 42 firms, followed by Dallas with 27, and Houston with 17. Capital backing these firms has continued to increase, with more than $500 million invested in Austin-based PropTech firms alone since 2018, according to online commercial real estate locator and messaging service theBrokerList.

The diversity within these firms touches practically every real estate sector, impacting all phases of a property’s life cycle. Companies such as Dallas’ Dottid and Austin’s Tenant Cloud are rapidly changing the tools brokers use to manage existing leases. Firms such as AnthemIQ and Billd—both based in Austin—have streamlined billing management during construction. They also connect the market for trading properties once the properties have been completed or listed. Finally, Austin’s SwivelMeta is bringing the metaverse to commercial real estate, allowing companies to build and manage their

digital advertising campaigns within a built environment that is a fully digital, immersive experience.

PropTech in Texas continues to grow and mature, with established firms already capitalizing on their specific disruptive technology. The firms, whether old or new, represent an extensive range of market participation. Here are some, categorized by type of service. (Editor’s note: These firms are provided as examples. Their inclusion here is not intended as an endorsement.)

Dottid provides a workflow tool that optimizes office, retail, and industrial portfolios. Its platform provides users of their SaaS technology with real-time insight into occupancy, deal activity, lease rolls, and other key operational data points.

Founded in 2020, Dottid secured a strategic partnership with Lincoln Property Company, an international real estate firm operating as a developer, owner, and brokerage shop. The firm provides value-add strategies for both commercial and residential properties.

RexTech Ventures covers multiple real estate sectors, acting as investor, innovator, and leader in traditional real estate investment space as well as PropTech. Founder Peter Rex has established nearly a dozen companies within the PropTech space.

Rex’s companies impact real estate investment not only directly through property ownership but also by providing technology solutions for contractor payments, project management, crowd-sourced (fractional) property ownership, and property insurance. In addition, RexTech Ventures has built a platform for developing, deploying, and growing new PropTech businesses.

Bowery provides appraisers with software that streamlines the valuation process. Its appraisers are able to quickly and carefully assess a property and its comparables so Bowery’s professionals can spend more time on the nuances of each building. The Bowery platform also provides access to property and market information on demand, generating consistent, high-quality, professional reports.

Lowry Property Advisors provides a full suite of property valuation and appraisal services for the office, industrial, and commercial sectors as well as for an array of unique properties, such as those purchased for transportation-related uses (e.g., road construction). Lowry has successfully expanded its office presence to include eight Texas markets.

Austin-based AnthemIQ (AIQ) streamlines workflows within the transaction process to save real estate brokers time. AIQ tracks deals, builds surveys, and schedules tours through an intuitive deal dashboard that stores all transactions in one place. This SaaS application allows executives to monitor their team’s performance against goals and provide transparency into their deal pipeline. AIQ currently serves over 1,000 users worldwide.

Founded by Bobby Bryant and Chris Norton, DOSS is a real estate technology company that has developed an Intelligent Personal Assistant that empowers users to speak, text, or type any question about any property to get accurate, easy, and instant answers. Their objective is to serve the entire lifecycle of homeownership by being there before, during, and after a person buys/sells a home.

Based out of Houston and founded in 2016, DOSS has raised a $1.65 million Family and Friends Round. Currently, they are raising a $5.5 million Seed Round. DOSS is backed by major technology companies like Amazon and Google.

OwnProp, one of RexTech’s newest ventures, provides newly accredited investors with the opportunity to knowledgeably invest in real estate through the tokenization of real estate assets, a process that replaces sensitive data with unique identification symbols that can retain all the essential information about the data. The platform provides investors with property details, financial analysis, and virtual tours. Each investment is recorded on the blockchain, providing users with increased security and liquidity.

PerotJain focuses its investments on the early-stage development of innovative companies spearheaded by entrepreneurs. Their expertise and experience with entrepreneurial technology

TODAY’S COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE PROFESSIONALS shared their insights on technological innovation with tomorrow’s industry leaders at Texas A&M University in November 2022. The one-day PropTech conference, sponsored by the Texas Real Estate Research Center and Mays Business School’s Master of Real Estate program, had about 160 attendees, 67 of whom were students.

Scan QR code to view photo gallery.

gives them unique insight into which firms to sponsor and helps guide their expansion.

By design, PerotJain is not structured as a fund, so their investment decisions can be free from all artificial capital constraints. In this way, the firm can focus on firms that align with their core principals. Hillwood Development Company is an affiliate of PerotJain. Together, their mission is to help shape the future development of real estate in Texas.

Crow Holdings is a vertically integrated global real estate business with $30 billion in assets currently under management. Elie Finegold is the managing director at Crow Holdings, leading their new venture and technology investment practice. Finegold has worked as an entrepreneur and leader at the intersection of real estate and technology for nearly 20 years. In addition to his work with Crow Holdings, he serves as a venture advisor at MetaProp, the leading early-stage PropTech venture capital fund.

Aerwave is a connectivity platform providing intelligent, private Wi-Fi for residential projects. The company works exclusively with real estate developers, owners, and operators in the multifamily, student living, build-to-rent, and single-family rental markets.

Aerwave’s platforms provide smart, instant-on Gigabit and Gigabit+ Internet service over a unified network infrastructure using patented HomeWiFiTM technology. This provides unique users private connectivity across a single property-wide network. The system powers smart-home and smart-building technologies to improve efficiencies, conserve resources, optimize

production, and enhance interaction between virtual and built environments.

Now is the time for investors and real estate professionals to learn about and engage with the PropTech industry.

The first step is to develop a roadmap. Start by asking what problems waste time and money or introduce greater business risk. Next, identify the job to be done and how this will benefit the firm’s customers or employees. Finally, think through the experience the firm is attempting to create. Once the problem and experience have been identified, study the technology landscape, and request a demo of two or three applications within the area of the value chain the firm is attempting to improve.

At that point, technology can be integrated into the firm’s processes. Create alliances with key stakeholders to facilitate adoption. Change is hard, so start small and anticipate pushback. Adopt a “listen, learn, and iterate” process, and communicate often to let stakeholders know their input is being incorporated. An integrated plan will include education, training, and sponsorship. The goal is improved business performance, so getting managers on board is essential to success. Celebrate small wins, and reward those who champion the new technology.

Dr. Hunt (hhunt@tamu.edu) is a research economist with the Texas Real Estate Research Center; Banks (bbanks@mays.tamu.edu) is associate director and executive assistant professor for Texas A&M’s Master of Real Estate program in Mays Business School; and Ramseur is executive professor for Texas A&M’s Master of Real Estate program.

Like-kind exchanges are popular, as many people are interested in deferring the tax on sale of property. When real estate is held in an entity, complexities arise when the owners of the entity have divergent views. Several variations on conventional like-kind exchanges can achieve desired tax results. By William D. Elliott

Editor’s note: This article is a follow-up to “Trading Spaces: Common Mistakes in a Like-Kind Exchange,” which was published in the Summer 2022 TG

When multiple individuals own real property—such as when children inherit their parents’ estate or when entities like partnerships or limited liability companies (LLCs) hold the asset—problems can emerge when the time comes to sell that property.

If all the partners in the partnership, members in the LLC, or inheriting children agree on a common form of transaction, the complexity is largely removed. The entity itself either sells the real estate and everyone shares in the sales proceeds, or the entity undertakes a like-kind exchange with everyone participating in the tax deferral. Problems arise when interests diverge.

Some of the investing partners or inheriting children may want to cash out of the real estate, while others want to seek a tax deferral such as through a like-kind exchange. Managing a favorable outcome for everyone is challenging. Fortunately, some common transaction structures have been developed that provide a reasonable chance of yielding a predictable tax result.

The phrases “drop and swap” or “swap and drop” describe popular structures that enable real estate owned by an entity composed of several owners to engineer a like-kind exchange for some and a cash-out sale for others.

In brief, the partnership distributes the real property to the individuals within the entity, removing the entity-level structure and making the individuals joint tenants (the “drop”).

Then partners can individually pursue the form of transaction most suitable to their interests. Some owners might sell out for cash, while others may undertake a like-kind exchange (the “swap”).

Drop and swap transactions are grounded in the statutory requirements for like-kind exchanges. For there to be a valid like-kind exchange, real property held for qualified use (the relinquished property) is exchanged for other property of a like-kind that is held for a qualified use (the replacement property). Only real property can be exchanged. Interests in the partnership owning the property do not qualify for a like-kind exchange. Thus, the real estate needs to be distributed out of the partnership to the partners.

For an exchange to qualify as a like-kind exchange, the investor must hold both the to-be-relinquished property and the replacement property either for productive use in a trade or business or as an investment. The qualified purposes may overlap (i.e., property held for productive use in a trade or business can be exchanged for investment property and vice versa).

The problem with the drop-and-swap transaction centers around timing. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) examines transactions that occurred before and after the like-kind exchange. Could the IRS argue that the partners held the relinquished property for the sole purpose of exchanging it? How can the partners prove they are holding the relinquished property for a qualified use?

Fortunately (for taxpayers, at least), the courts have historically rejected such arguments. A leading case, Bolker v. Comm’r, 760 F.2d 1039, 1044-45 (9th Cir. 1985), involved a sole shareholder of a corporation that had the corporation liquidate and distribute a certain piece of real property to him as the sole shareholder. On the same day, the shareholder entered a contract to exchange the property for other like-kind real property. The IRS argued the shareholder did not have the qualified intent because he acquired the relinquished property for the purpose of exchanging it. The Ninth Circuit rejected the IRS’ claim because the shareholder both owns and holds

the property, and as long as the shareholder did not intend to sell the property or use it for personal use, then he held the property for a qualified use. Courts have found the replacement property is essentially a continuation of the relinquished property, but still unliquidated. Thus, investors can enjoy some level of confidence that a like-kind exchange is possible after a drop-and-swap transaction.

The IRS could challenge drop-and-swap transactions on other grounds, such as the individual investors (partners) did not initiate the exchange, but instead the partnership was actually the transaction party. This is a “substance over form” argument. Some facts that might strengthen the IRS’ argument include:

• The partnership negotiated the complete transaction.

• The partnership received the offer to purchase the real estate from an unrelated individual.

• The individual partners did not pay any portion of the real estate commission.

• The individual partners did not pay any of the operating expenses between the date of the deed and the date of the sale.

• The partnership accepted the first offer but recast the transaction into a drop-and-swap before closing.

A reverse exchange involves the investors acquiring the replacement property before the relinquished property is sold. There might be good reason for reversing the order of the transaction. For example, the seller of the replacement might need to sell the property, and locating a buyer of the relinquished property is taking time. The investors may want to be certain

they can obtain the essential property before undertaking the large like-kind exchange. They might want to start zoning or financing on the replacement property before the exchange takes place.

The IRS has made reverse exchanges somewhat easy by creating a safe harbor. As long as the investor falls within that safe harbor, tax consequences are predictable. For this to apply, the transaction requires that someone acquires the replacement property before exchanging it with the investor. Under the safe harbor, an exchange accommodation titleholder, or EAT, can acquire the replacement property and hold it until the disposition of the relinquished property. Once a buyer for the relinquished property is found, the EAT transfers the replacement property to the investor. The investor could also acquire the replacement property and have the EAT hold title to it.

The EAT must hold qualified indicia of ownership of the replacement property and continue to do so from the initial acquisition until it’s transferred to the investor. Additionally, the investor must have a bona fide intent to exchange the relinquished property for its replacement. Within five days of the replacement property’s transfer to the EAT, the investor and the EAT must have a formal agreement dealing with the EAT’s ownership of the replacement property. This is commonly called a qualified exchange accommodation agreement, or QEAA.

In a reverse exchange, the relinquished property must be identified within 45 days of transferring the replacement property, and the EAT has 180 days to transfer the replacement property to the investor.

The safe harbor for reverse exchanges, which permits all kinds of contractual or legal relationships, illustrates the IRS’ ability to ensure certain results. The following circumstances illustrate some of the more commonly encountered and permissible contractual relationships:

• Guarantees are permitted. The investor can guarantee some obligations of the EAT, such as debt or protection against expenses.

• Debt can be extended. The investor can loan money to the EAT.

• Leasing permitted. The EAT can lease the replacement property to the investor.

• Management of property. The investor can contract with the EAT to manage the replacement property or supervise improvements to the property.

In the safe harbor, the IRS is showing a practical side by allowing a variety of circumstances to be used. These permissible circumstances are commonly encountered in the marketplace, so the IRS is trying to permit common financial and business tools while at the same time allowing the parties to accomplish a tax-free reverse exchange.

The IRS has made clear that reverse exchanges can occur outside of the safe harbor, but most real estate investors and their advisors prefer the definite guidance offered by the safe harbor. In cases where the United States Tax Court approved a reverse exchange outside of the safe harbor, the essential issue was whether the third-party accommodation party had the benefits and burdens of ownership.

The use of single-member LLCs to hold title to real property is another development involving reverse exchanges. Single-member LLCs are disregarded for tax purposes. Additionally, newer series LLCs are seen as suitable ownership vehicles for the replacement property.

Rather than having separate interests, an investor might want to acquire replacement property with others and contemplate acquiring an LLC interest in an entity that owns the property. Unfortunately, since the LLC is not considered real property, the exchanges previously outlined will not apply. The investor must acquire an interest in real property, not an interest in an entity that owns the real property.

In this situation, the usual arrangement is for the investing group to enter into a tenants in common (TIC) arrangement, with each investing person acquiring an undivided interest in the property. TICs are structured to avoid partnership status. Cash distributions must be distributed pro-rata, tax allocations are pro-rata, and carried interests are not permitted.

A variation for co-ownership form is the Delaware Statutory Trust, which is attractive for persons not wanting management responsibility.

Elliott (bill@wdelliottlaw.com) is a Dallas tax attorney, Board Certified, Tax Law; Board Certified, Estate Planning & Probate; Texas Board of Legal Specialization; and Fellow American College of Tax Counsel.

The IRS has made reverse exchanges somewhat easy by creating a safe harbor. As long as the investor falls within that safe harbor, tax consequences are predictable.By Adam Perdue

Recently, home prices have grown more than four times faster than the 2012-19 annual trend of 5.27 percent. From January 2020 to May 2022, the average selling price of a home in Texas rose from $278,542 to $443,856. This 59 percent increase over two years and four months is equivalent to a 22 percent annualized growth rate. Broadly speaking, the main cause of this rapid price run-up was a rapid fall in interest rates while most typical homebuyers remained employed.

However, the average price could also have been influenced by what is called a composition effect. For example, many have postulated that homebuyers shifted their preferences to larger

Prices aren’t the only things that changed for housing during the pandemic. The physical characteristics that buyers looked for in houses also changed, and in predictable ways.

homes because of COVID-19. They may also have shifted in that direction as mortgages became cheaper. Regardless of the reason, that shift in demand to larger and presumably more expensive homes would cause the reported average price to increase even if no individual home actually increased in price.

The Texas Real Estate Research Center’s (TRERC) Home Price Index (HPI) attempts to control for these composition effects and provide a more reliable indicator of average house price changes. Are signs of composition effects evident? If so, how do those composition effects impact the relationship between the average transaction price and the HPI? (Scan QR code to see Center’s HPI.)

Before COVID, the median age of purchased homes in Texas had been trending upward. It trended down during the pandemic, then returned to and rose above trend starting in mid 2021 (Figure 1).

The linear trend is estimated using 2012-19 data, then pulled forward through May 2022. The median age of a home sold in Texas fell significantly below trend in 2020, recovering in 2021 and 2022 likely due to fewer newer homes on the market. Figure 2 shows the divergence from the trend line, confirming the pattern.

Figure 1. Median Age of Homes Sold in Texas Months

Texas Median age of structure

Texas Median age of structure 2012-19 trend

Source: Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University

Figure 2. Median Age of Homes Sold in Texas (Trend Deviation) Years

Texas median age of structure 2012-19 trend

Source: Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University

2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 0.0 –0.5 –1.0 –1.5 –2.0

Years Houston San Antonio

2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Austin Dallas-Fort Worth

Source: Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University

Figure

2,040 2,020 2,000 1,980 1,960 1,940 1,920 1,900 1,880

2012 2014 2016 2018 2020 2022

Texas median square feet Texas median square feet 2012-19 trend

Source: Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University

Figure 5. Median Square Footage of Homes Sold in Texas (Trend Deviation)

Square Footage

40 20 0 –20 –40 –60 –80

Square Footage 2012 2014 2016 2018 2020 2022

Texas median square feet 2012-19 trend deviation

Source: Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University

A similar methodology was used for Texas’ four major Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSA) (Figure 3). All four MSAs followed similar patterns as the state: an apparent drop in the median age of sold homes through 2020 relative to trend, with marked increases in median age through 2021 into 2022 in Austin, Dallas-Fort Worth, and San Antonio. Houston’s path favored much newer homes in 2020 with a return to trend in 2022, but the story is essentially the same.

The median square footage of homes sold in Texas had been on a slight trend upward from 2012 until COVID hit (Figure 4). As with age, a linear trend was estimated for 2012-19 then pulled forward through 2022. Figure 5, which shows the deviation from the trend, reveals an increase in median square footage through 2020 followed by a collapse to well below trend through 2021.

Texas’ major MSAs show a similar pattern (Figure 6). San Antonio stands out due to the linear trend assumption not holding from 2012-19. Something else was occurring in San Antonio, and the city’s median square footage peaked in 2015. Despite that, San Antonio follows the underlying shifts common across Texas: square footage follows a trend, increases above that trend in 2020, then falls below trend through 2021 and into 2022.

Square Footage

Changes in the housing stock being traded make interpreting price changes difficult. If people shift toward purchasing larger homes in a given month, the average sold price for that month will increase even if none of the houses on the market increased in price.

This difficulty can be lessened in Texas using TRERC’s HPI. The influence of composition effects are apparent with average sales prices increasing more than the indexed prices as the market composition shifted toward newer and larger homes through 2020 (Figure 7). In 2021, the values reversed as the market ran out of those larger and newer homes. Figure 8, which uses the HPI growth rate minus growth in average sales price, shows the same pattern held for each of Texas’s major metropolitan regions.

People don’t always completely change their minds about buying a home just because of a major shock in the housing market. Often, they’ll simply change the characteristics of the home they planned to buy. TRERC’s HPI controls for these composition effects to provide a better measure of value increase across a given home market.

Dr. Perdue (aperdue@tamu.edu) is a research economist with the Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University.

Figure

100 50 0 –50 –100 –150

2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Austin Dallas-Fort Worth Houston San Antonio

Source: Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University

Figure 7. Change in HPI vs. Change in Average Sold Price, Texas

Percent YOY Change

35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 –5 –10

2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018 2020 2022

Index Sale Price

Source: Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University

20 15 10 5 0 –5 –10 –15 –20

2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Austin Dallas-Plano Fort Worth Houston San Antonio

Source: Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University

George Strait had a tongue-incheek number-one hit with “Oceanfront Property” in 1986. Unlike Arizona, Texas has oceanfront property in abundance. Miles and miles of Texas—367 to be exact— border the Gulf of Mexico, making it the sixth-longest coastline in the U.S.

An earlier TG article, “Moving Water: Boundary Changes and Property Rights” (scan QR code to download), discussed the effects of erosion, accretion, avulsion, and subsidence on the boundaries of land where water forms the boundary.

This article addresses two matters that affect owners of property on the seashore: the location of the boundaries, and the public’s right to access beaches and navigable waters.

All real estate in Texas was originally owned by Spain (1690-1821), Mexico (1821-36), or the Republic/ State of Texas (1836-present). The original grants or patents of land all came from one of those sovereigns.

Unlike most other states, the land was never owned and conveyed by the United States federal government. For this reason, Texas property boundaries are determined by Texas courts, applying the law of the granting sovereign at the

time the grant was made. Federal law has little or no effect on these matters.

The land seaward of the line of mean low tide is considered to be permanently covered by the water. This submerged land is owned by the state unless the state has intentionally conveyed that land to another owner, which the legislature may do if it so wishes.

The waters covering submerged land are considered navigable waters and may be used by the public for trade, navigation, and recreation. Upland or “fast land” is above the high-water line (more on this later) and is owned by the private landowner. The area between the high-water line and the extreme seaward line of vegetation, which spreads continuously inland, is referred to as the “dry beach.”

Between the state-owned submerged land and the upland is the tideland or “wet beach,” which is the land that is covered and uncovered by the water as a result of the tides. The wet beach is also owned by the state.

As stated in “Moving Water,” a simplified definition of the shoreline as a boundary is the average daily high-water level. It’s actually a bit more complicated than that.

In disputes over seashore boundaries, as with all boundary and title disputes, courts attempt to determine the intent of the grantor. In determining the grantor’s intent, the court attempts to interpret the language of the original grant or patent as determined by the law in effect at the time of the grant. Prior to Texas’ independence, it was under the civil law of Mexico, and before that, Spain. These systems of law trace their origin as far back as ancient Rome. When Texas became an independent state, it began blending the civil law system of Mexico with elements of other legal systems, including the French civil law system in use in neighboring Louisiana and the English common law system in use in the United States. As to land, the civil law system prevailed until Jan. 20, 1840, when the Texas Congress provided that the rule of decision for the courts of the Republic should be the common law of England, as far as it could be applied consistently with the Constitution of the Republic.

Accordingly, if the grant was made by Spain or Mexico, it will be determined by the civil law of Spain or Mexico, respectively, which was in effect at that time. A grant made by the Republic prior to Jan. 20, 1840, is governed by the civil law of Texas on the date of the grant, whereas a grant made on or after that date is governed by Texas common law in effect at the time of the grant.

For common law grants, the seashore boundary is the ordinary high-water mark. Texas courts have held

this to be the line of “mean high tide.” Rudder v. Ponder, 156 Tex. 185, 293 S.W.2d 736 (1956). For civil law grants, the boundary is “mean higher high tide.” Luttes v. State, 159 Tex. 500, 324 S.W.2d 167 (1958). So what’s the difference?

Mean high tide is determined by finding the mean of all of the daily high tides over a period of 18.6 years, which is the length of the periodic astronomical cycle that affects the tides. For days with more than one high tide, each high tide is a data point.

Mean higher high tide is determined by finding the mean of all of the higher daily high tides over the same period. For days with more than one high tide, only the higher high tide is included in the calculation.

The measurements are made by offshore tide gauges. An excellent discussion of the methodology is found in Luttes. The measurements are made over an 18.6-year astronomical cycle, where data are available. Where data are not available for the entire cycle, the available data are adjusted by reference to other tide gauges.

The water levels are affected by astronomical forces (tides) as well as non-tidal forces (atmospheric conditions such as wind and weather). Because the gauges measure the level of the water as affected by all forces, the rule actually seems to be based on a calculation of mean high water as measured by tide gauges. Either way, as the court states in Luttes, the Spanish (Mexican) law concept of the shore is the area in which land is regularly covered and uncovered by the sea over a long period. Luttes, 324 S.W.2d at 192. This allows the rule to be applied in areas where water levels fluctuate more due to atmospheric conditions as opposed to tidal flows, such as the Laguna Madre.

According to these rules, a landowner owns the beachfront to the line of mean high tide or mean higher high tide, depending on whether the original grant was a common law grant or a civil law grant. The state, then, owns the submerged land and the wet beach. The dry beach, from the applicable high-water line to the line of vegetation, is owned by the upland landowner.

What about the public’s right to access the beach? Soon after the decision in Luttes, the Texas Legislature enacted the Open Beaches Act as a means of enforcing the rights of the public (where and if they existed) to access and use Texas Gulf beaches, even where they were privately owned. The act, as amended, declares that Texas’ public policy is that the public, individually and collectively, shall

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, about 6.5 million people live in Texas’ coastal regions, accounting for 24.5 percent of the state’s total population.Author Rusty Adams talks more about this on TRERC’s YouTube channel.

have the free and unrestricted right of ingress and egress to and from the state-owned beaches bordering on the seaward shore of the Gulf of Mexico. It also declares that if the public has acquired a right of use or easement to or over an area by prescription or dedication, or has retained a right by virtue of continuous right in the public, the public shall have the free and unrestricted right of ingress and egress to the entire beach, including the privately owned dry beach.

The act empowers the commissioner of the General Land Office, along with the attorney general and district and county attorneys, to enforce prohibitions against encroachments on and interferences with the “public beach easement.” A person may not construct any obstruction, barrier, or restraint that will interfere with the rights of the public on a public beach. The public beach, for this purpose, does not include a beach that is not accessible by a public road or public ferry. Likewise, a person may not display a sign, marker, or warning that the public beach is private property or that the public does not have a right of access.

The public beach includes the area from mean low tide to the line of vegetation. If there is no such line, or if the line is more than 200 feet inland from the line of mean low tide, the line is set at 200 feet inland from the line of mean low

tide. If the line of vegetation is obliterated as a result of a meteorological event such as a hurricane or tropical storm, the land commissioner may suspend action on determining a line of vegetation for up to three years, during which time the public beach extends 200 feet inland from the line of mean low tide. In some cases, encroachments on a public beach may be enjoined or removed, and landowners may be subject to civil penalties of up to $2,000 per day.

Littoral landowners must submit development plans of proposed construction on land adjacent to the public beach.

The constitutionality of the Open Beaches Act has been questioned. It appears the legislature was careful in its drafting of the act and its amendments. The act purports to be only a means of enforcing the public’s rights to beaches where it has acquired rights in the beach by dedication, implied dedication, or prescription. Whether the public has acquired such rights is a fact question that must be proven. The act was amended in 1991 to provide that there is a presumption that the public has such an easement, and that the landowner does not have the right to exclude the public from using the area for ingress and egress to the sea. The constitutionality of this presumption is open for debate. Severance v. Patterson, 370 S.W.3d 705, 715, n. 9 (Tex. 2012).

Erosion and other natural forces are constantly changing property lines along Texas’ 367 miles of coastline.Red Zone podcast host Hayley Rieder Wiley talks with Adams.

Severance also decided a certified question regarding the theory of a “rolling easement” encumbering Texas beachfront property. The rolling easement theory basically was that when the public has an easement encumbering the dry beach, if the sea moves landward, the easement moves landward with it. The Texas Supreme Court was presented with a certified question by the federal Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. The court held that for the public to have a right to use the beaches, it must prove such a right by proving an easement for use of the dry beach under the common law or by other means set forth in the Open Beaches Act.

The court further held that if such an easement is proven, it does not “roll” or move when the location of the dry beach moves landward. If the easement exists and if the dry beach burdened by it is diminished or eliminated by naturally caused changes in the location of the vegetation line, then the easement does not move; rather, it is diminished or eliminated as well.

Section 61.025 of the Texas Natural Resources Code requires a statutory disclosure to be provided to purchasers of land located seaward of the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway. The disclosure notifies the buyer

Wof certain risks involved in purchasing real property near a beach. hile this notice is still required, and while it does provide important warnings, it should be noted that the disclosure does not create any rights, and that some of the statements may be incorrect based on specific facts and subject to court decisions.

Texas has its share of oceanfront property with its undeniable allure. After all, “from the front porch you can see the sea.” The nature of its boundaries, however, and the potential rights of the public, offer specific risks and questions of law that should be considered.

Nothing in TG should be considered legal advice. For advice on a specific situation, consult an attorney.

Adams (r_adams@tamu.edu) is a member of the State Bar of Texas and a research attorney for the Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University.

conomic forecasts are tricky, what with so many state, national, and global variables at play (to say nothing about how a devastating weather event such as a hurricane or winter storm can reshuffle the deck mid-year). But using their collective understanding of current economic and market conditions and by looking at past market trends, the Texas Real Estate Research Center’s (TRERC) research team has made some educated guesses for 2023.

A few known risks in the near term may impact this forecast, and exactly how these scenarios play out will shift TRERC’s expectations. The direction and intensity of the following national and international factors will have a large influence on the Texas economy:

• China’s zero-COVID policy and responses to ongoing public protests, which are hampering the global economy.

• Russia’s war against Ukraine, which has disrupted the global grain and energy markets, increasing instability across the globe.

• Europe’s energy situation (related to Russia’s war), which is especially dire and could worsen depending on the severity of winter.

• The outcome of the Federal Reserve’s attempts to control inflation through higher interest rates.

With that in mind, here is TRERC’s forecast for 2023, given current conditions.

• Industrialdeliverieswillpull backfrom2022’srecordhighs whilevacanciesremainlow.

• Theofficemarketwillfurther segmentasnewerbuildings maintainoccupancyandolder buildingslowerrenttoattract tenants.

• Occupancyandrentswill stabilizesomeinbrick-andmortarretail.

• Expecttoseemorelifein thebesttraditionalindoor mallsaspeoplerestorelongneglectedsocialhabits.

To hear the TRERC research team talk about their 2023 forecast, tune in to the Red Zone podcast.

• The mortgage interest rate’s annual average will likely be higher in 2023 than it was in 2022.

• Existing single-family rent and price growth will moderate with the potential to turn negative on a year- over-year basis.

Commercial Real Estate

• 2023 will have fewer rural land transactions than 2022.

• Prices for lower-quality land will fall, while prices for high- quality properties will remain steadier.

• Inflation will likely stay elevated through 2023.

• Employment growth will moderate.

• Oil will likely average between $80 and $100 per barrel.

• The global response to Russia’s war on Ukraine will play a large role in the path oil takes as well as any decision by OPEC.

• A recession would place downward pressure on prices.

Read TRERC’s complete 2023 Texas Economic Forecast online.

In 2021, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit ruled that real estate professionals

use floor plans for marketing purposes without proper authorization. Because Texas falls under the Fifth Circuit, the ruling does not currently apply there. However, that could change if Texas courts choose to follow it or if the Supreme Court rules on the issue.

It is a safe bet that most Americans would be startled to hear they could be sued for copyright infringement for making floor plans of their own homes. Many homebuyers rely on floor plans in real estate listings to decide whether to purchase a residence, and their ability to secure financing for that transaction is often contingent on an appraisal that requires the creation of a floor plan. After acquiring a dwelling, homeowners will often make floor plans to tackle installations, arrange furniture, and complete do-it-yourself projects. On top of that, many localities require homeowners to submit floor plans before they can renovate their property. And when it comes time to sell, many Americans expect they will be able to use floor plans to secure the maximum value possible. The notion that all this conduct and more would flout the Copyright Act might cause even the mildest of homeowners to wonder what congress was thinking.

This statement is from the summary set out in the amicus brief filed with the U.S. Supreme Court by the National Association of Realtors (NAR) and 17 other real-estate-related entities in April 2022 in support of the petitioners in the case of Columbia House of Brokers Realty Inc. vs. Designworks Homes Inc. The case addressed whether preparing a floor plan on a property constitutes a violation of an architect’s copyrighted plans under the U.S. Copyright Act.

BY KERRI LEWISWhat were NAR’s arguments, what was the Supreme Court’s ruling, and how might it affect Texas homeowners and real estate professionals?

Designworks Homes Inc., an architectural firm, brought this case against Columbia House of Brokers Realty Inc., a real estate broker, alleging its sales agent’s computergenerated floor plan for use in marketing to sell a home was a copyright infringement of Designworks’ architectural plans.

The law at issue in this case is §120(a) of the Copyright Act. That statute provides an exclusion to the copyright protection of architectural plans stating the “copyright in an architectural work that has been constructed does not include the right to prevent the making, distributing, or public display of pictures, paintings, photographs, or other pictorial representations of the work, if the building in which the work is embodied is located in or ordinarily visible from a public place.”

Although the district court in Missouri found the floor plans were “pictorial representations” and, therefore, not an infringement, upon appeal, the decision was reversed. In August 2021, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit ruled that the broker’s computer-generated floor plans were not one of the categories set out in the Copyright Act, so the broker did infringe on the architect’s copyright by creating and publishing the floor plans without authorization.

The appellate court’s decision was based on an analysis of the statutory language stating:

can’t

We think that the terms Congress used in § 120(a) have a certain quality in common—they all connote artistic expression. Recall that that section speaks of “pictures, paintings, photographs, or other pictorial representations of” a work. Pictures (when properly interpreted as already discussed), paintings, and photographs connote expression. We think that pictorial representations, when read together with these other terms, most likely refer to pictorial representations created for similar reasons. Floor plans like the ones here, on the other hand, serve a functional purpose. Though it’s conceivable that a floor plan could be created for artistic purposes, we deal here with floor plans that all seem to agree were generated for the practical purpose of informing potential buyers of home layouts and interiors, and, more broadly, to help sell homes. They do not share the common quality that the other terms possess. [9 F. 4th 803 (8th Circuit 2021)]

Though the Eighth Circuit’s opinion did suggest the “fair use” exception might offer some protection, it has not been litigated yet. The broker appealed the ruling to the Supreme Court.

In April 2022, NAR and 17 other real estate industry organizations filed an amicus brief in support of the broker’s position that floor plans created by homeowners or real estate agents did not constitute a copyright infringement. The purpose of an amicus brief is to share knowledge or perspective of the subject matter with the court by a person or entity that is not a party to the actual case.

The amicus brief requested the Supreme Court grant certiorari (take the case) and reverse the Eighth Circuit Appellate Court’s interpretation of the copyright exception. The chief argument presented was that the Eighth Circuit’s reasoning was deeply flawed and contrary to years of precedent, both legal and everyday usage stating: The decision below threatens not only homeowners with sanctions for the use, enjoyment, and disposition of their property, but the many sectors of the economy linked to real estate as well. And it does so based not on the operative text—the court of appeals never denied that floor plans fit within the ordinary meaning of “pictures” or “pictorial representations”—but on a misguided chain of inferences from statutory context. Yet nothing in the reasoning below justifies replacing the most natural meaning of the Copyright Act with an esoteric one—especially a reading that threatens to upend the use of floor plans that are critical to the nation’s trilliondollar real estate industry.

They also provided key statistics and factors highlighting potential harm to home sellers and buyers if the Eighth Circuit’s ruling stands, such as:

• Two-thirds of homebuyers who shop on the Internet (95 percent of all homebuyers) found floor plans useful.

• Listings with floor plans on Zillow attract the most views.

• Eighty-one percent of homebuyers in a national survey say they are more likely to tour a home if its listing includes a floor plan.

• Mortgage lenders generally require an appraisal with a floor plan.

• Many jurisdictions require floor plans with applications for renovations.

• The decision opens up a new “hunting ground for enterprising copyright trolls” to threaten homeowners, real estate agents, appraisers, floor plan software companies, and home improvement and furniture companies.

• The decision puts the 1.5 million real estate agents and the 81 million homeowners in the U.S. at risk for expensive litigation.

The full brief is online (scan QR code to download).

On June 27, 2022, the Supreme Court declined to review the case, which means the ruling of the Eighth Circuit Court stands.

Keep in mind the Supreme Court is under no obligation to consider positions set out in an amicus brief. What this means practically is the Supreme Court is waiting to see if another U.S. Court of Appeals for another circuit finds §120(a) includes floor plans under “pictorial representation” and floor plans are not an infringement. If that happens, they will likely take a case to resolve conflicting interpretations of federal law.

What does this case mean for real estate professionals and homeowners in Texas? Texas is not under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit (Texas falls under the Fifth Circuit), so their ruling does not have to be followed by lower courts in Texas. However, with no other appellate court precedent on whether floor plans fall under the §120(a) copyright infringement exception, Texas courts could choose to follow it.

The best-case scenario would be for another case to be filed on this issue in another circuit court who finds floor plans are covered by the §120(a) exception. Then the Supreme Court could take the case and

resolve the conflicting interpretation of that section. Who knows when that will happen and which way they will rule. Another option would be for Congress to amend §120(a) to specifically include floor plans in the exception. Again, not likely in the near future unless the national groups that filed the amicus brief lobby strongly for it.

Although there is not much real estate professionals can do about floor plans they’ve posted on the Internet or Multiple Listing Service in the past, perhaps some additional planning needs to take place going forward until this issue is ultimately resolved.

First, don’t publish a floor plan on a public forum, such as a public-facing website, unless you have written permission from the architect who drew the original plans. Of course, this is practical only for newer homes where the architect is known and easily located. Also, understand the potential risk of continuing to generate floor plans to use in marketing properties and communicate that to clients.

Some clients and real estate professionals might consider whether the reward of continuing to use floor plans in the same way outweighs the risk of copyright infringement litigation. Brokers might consider updating their copyright policy to include a statement on floor plans.

Lewis (kerrilewis13@gmail.com) is a member of the State Bar of Texas and former general counsel for the Texas Real Estate Commission.

© Floor plan property of the Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University. No copyright laws were violated with its publication here.

Demand for rural Texas land surged in the wake of COVID-19 and unrest in the state’s urban centers. However, that demand has since slowed along with price growth.

By Charles E. Gilliland and Lynn D. KrebsIt’s certainly been a tumultuous few years for Texas’ land markets, what with demand plummeting in the first half of 2020 only to unexpectedly take off again in the second half of the year. Two years later, the market appears to have settled down again.

What factors have been driving demand for rural land the past few years, and what questions are market experts asking going into 2023?

Canceling concerts, closing restaurants, shuttering bars, and prohibiting gatherings, cities shut down most public interaction in 2020 to reduce the spread of

COVID. Suddenly, urban dwellers faced the prospect of quarantining at home or risking an infection when they ventured out.

The pandemic forced city-dwellers to work online from home and shift gatherings such as churches, schools, and conferences from in-person to virtual. Oil prices collapsed as travel ground to a halt.

Brokers reported that some clients were concerned about violence and unrest in the city, and that was their motivation for buying rural property.

These developments brought Texas land market activity to a standstill in 2020. Brokers’ phones went silent. Second quarter total sales dropped 9 percent

Generally speaking, rural land is located outside Metropolitan Statistical Areas. It consists of properties larger than regional minimum acreages and priced at less than $30,000 per acre.

below the 2019 second quarter numbers, and land market professionals braced for significant downward pressures on prices.

Surprisingly, by third quarter 2020 those COVID-induced conditions inspired a stampede of newly sequestered Texans to the countryside searching for land. Rural transaction numbers soared as urban dwellers descended on bucolic areas, seeking escape from cities. They could work and conduct conferences from home. They could venture out in sparsely populated communities with a much lower probability of exposure to infected people. They felt safer in rural Texas.

Third-quarter 2020 transaction totals soared 47 percent higher than 2019. The fourth quarter shot up 85 percent followed by a 69 percent first-quarter 2021 increase over the anemic 2020 total. The explosion of activity continued with a 71 percent second-quarter increase.

Third quarter 2020 through third quarter 2021 was perhaps the most remarkable period Texas’ land market has ever experienced. Brokers had difficulty setting asking prices on listed properties as motivated would-be buyers made offers exceeding recent norms. The statewide price increased 26 percent from second quarter 2020 through third quarter 2021. Although subsequent quarters began posting smaller volumes of sales, prices continued to climb. The statewide price per acre shot up from $2,969 in second quarter 2020 to $4,426 in third quarter 2022, a 49 percent increase in two and a half years.

The figure shows the stampede’s effect on sales volume (number of sales) and price (dollars per acre). Demand began to soar in third quarter 2020. That explosion of activity, followed by three more quarters of rapid sales growth, initiated a remarkable run-up in price per acre beginning in first quarter 2021. Prices rose 9 percent year over year, exploded in the second quarter to 18 percent, then peaked at 29 percent in fourth quarter 2021.

Meanwhile, quarterly sales volumes have declined from the previous year’s feverish activity level.

Tables 1 through 7 provide an analysis of regional Texas market dynamics, showing prices and numbers of sales in the second quarter of each year from 2019 through 2022. In all regions except Far West Texas, volume exploded in second quarter 2021, instigating record price increases the following year. Virtually all regions posted declining activity in second quarter 2022, coinciding with the declining rate of price growth shown in the figure.

These developments suggest activity has slowed. However, that slowdown occurred after a historic explosion in demand for land. As the fall unfolds, the hoard of would-be buyers appears to have diminished to a smaller gang struggling to find properties listed for sale. Faced with few attractive potential opportunities, landowners have opted to hold onto their land rather than sell and find other investments. The pressure of heavy demand appears to be waning, but it has not vanished, and sales prices continue to climb at a more modest pace.

The resumption of in-office work, restored popularity of in-person conferences, and new landowners’ experience of the realities of property maintenance have pushed down demand for rural land, and rising interest rates may further cool demand pressures. The next few quarters may produce interesting developments in land markets.

Given the realities of ownership, will the newest cohort of landowners stay the course? Will new buyers continue to enter the market? Will buyers of all types become more discriminating regarding the quality of individual tracts? The Texas Real Estate Research Center will continue to monitor market activity and report new trends.

To track the latest regional land market developments, scan QR code.

Dr. Gilliland (c-gilliland@tamu.edu) and Dr. Krebs (lkrebs@tamu.edu) are research economists with the Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University.

Q. What can an agent write in Paragraph 11 (Special Provisions) of a TREC promulgated sales contract?

A. Not a dang thing! Seriously, though, factual statements and business details only. A prudent agent or broker will hesitate and think hard before ever writing something in Paragraph 11.

Q. If the legal description of the property cannot fit in Paragraph 2, and it will all fit in Paragraph 11, is it acceptable to put the legal description there?

A. Yes, that is a good place to put it. Remember, if the whole legal description will not fit in the space allowed for Paragraph 11, put the whole legal description in an attached exhibit to the contract. It is never good to split up the legal description.

License holders must use and are permitted to fill in the blanks on contract forms and addenda promulgated by TREC. So, they are allowed to insert information into Paragraph 11. However, a license holder shall only add factual statements and business details or shall strike text as directed in writing by the principals. Also, if TREC promulgated an addendum

that addresses the factual statement or business detail the client wants to add, a license holder must use that addendum and not write it in Paragraph 11. Finally, a license holder may not draft language defining or affecting the rights, obligations, or remedies of the principals, including escalation, appraisal, or other contingency clauses. [TREC Rules §537.11]

Examples of facts or business details that could go in Paragraph 11: 1031 exchange language; additional parties whose names will not fit in Paragraph 1 but will fit in Paragraph 11; and a legal description that will not fit in Paragraph 2 but will fit in Paragraph 11. Examples of facts or business details that cannot go in Paragraph 11: Anything that changes the rights, obligations, or remedies of the parties (e.g., “the earnest money will be non-refundable”); anything that should

be addressed in another section of the contract (e.g., repairs go in Paragraph 7; “clean the house before closing” goes in Paragraph 7D; “run a daycare on the property,” Paragraph 6D; “seller to pay for closing costs for buyer,” Paragraph 12A); and anything for which a promulgated addendum exists (e.g., Back-up Contract Addendum should be used instead of writing “this is a back-up contract” in Paragraph 11).

Paragraph 11 is provided for factual statements and business details. The hard part for brokers and agents is Special Provisions is seen as the place to put whatever might be “imagined” by the consumer or the agent. Exercise caution and rarely use Paragraph 11. Consistent training on the contract will help a license holder understand where to put items required by a

Q.

Special Provisions Paragraph 11?

client and what constitutes the unauthorized practice of law. If a client insists on putting a statement in Paragraph 11 that the license holder thinks crosses into the practice of law, the license holder should suggest the client consult with an attorney on the language. If the client does not, let her write the language herself.

A. No. Offer expiration provisions are not part of the contract between the parties. They are a pre-contract issue and are more properly placed in the cover letter or email delivering the contract offer.

Nothing in this publication should be construed as legal advice for a particular situation. For specific advice, consult an attorney. Lewis (kerrilewis13@gmail.com) is a member of the State Bar of Texas and former general counsel for the Texas Real Estate Commission (TREC). Wukasch (avis@2oldchicks.com) is a broker and former TREC chair.

Is it okay to put “This offer will expire in two days if not accepted” in