LIFTING

SCREEN TIME Digital eye strain and the toll it takes on children

CORNEA A look at one of the most extraordinary parts of the eye

GENETIC NURTURE Do virtual parents pass down myopia to our children?

CPD CPD

ISSN 2632-0584 Winter 2023 college-optometrists.org

How can optometrists help relieve patients of their treatment burden?

PLAY YOUR PART How to speak up and change the future of optometry PROFESSIONAL EXCELLENCE IN EYE HEALTH

THE LOAD

The Young Eye: Assessment of Vision

Examining children often requires an adapted approach to both communication style and the tests used. In this three-part course, two experts come face to face with children aged a few months to 18 years and show how adjusting the consultation can turn the typical challenges of assessing children’s vision into a rewarding process for the practitioner.

The course also includes an updated version of the Docet Examining Children Booklet and a comprehensive Glossary of Tests used when examining younger patients.

To take this course and discover more CPD visit www.docet.info

Search docet.info

Managed and delivered by The College of Optometrists and funded by the UK’s Health Departments,

OPINION

11

Clear view

The College’s Clinical Editor, Jane Veys MCOptom, on the value of curiosity in the clinical world 12 Big

question

What can be done to minimise treatment burden for patients? 16 One to one

Evelyn Mensah, Consultant Ophthalmologist, on what she is doing to encourage equality

PRACTICE

18 Screen time

How is children’s increased use of digital devices impacting their eye health? 23 Refresher

Explore the wonders of the cornea and promising research avenues in corneal innervation 26 Clinical notes The scope of practice and eye care services in optometry 28 Ageing

Supporting older patients whose quality of life has been affected by eye disease

Case study Complications arising from postoperative cataract surgery, leading to reduced visual outcomes

AMD How does the causal relationship between agerelated macular degeneration and atrophy of the visual cortex work?

Genetics Does genetic nurture play a significant role in the childhood development of myopia alongside genetics?

Career profile A conversation with Denise Voon MCOptom on her award-winning work at Amersham Hospital

BUSINESS

How to... Speak up and shape the future of the profession

Health coaching How can health coaching strengthen the patientpractitioner relationship? 50 Did you know..? The optical landscape in numbers

THE COLLEGE OF OPTOMETRISTS 42 Craven Street London WC2N 5NG 020 7839 6000 college-optometrists.org EDITORIAL BOARD Iftab Akram MCOptom Farah Awan MCOptom Dr Tamsin Callaghan MCOptom Dr Sandeep Dhallu MCOptom Dr Neema Ghorbani MCOptom Rashida Makda MCOptom Dr Annette Parkinson MCOptom Farhana Patel MCOptom Preeti Singla MCOptom Jane Veys MCOptom EDITORIAL LEAD Isabelle Rameau EDITOR Emma Godfrey emma@acuityjournal.co.uk CONTENT SUB-EDITORS James Hundleby, Amy Beveridge DESIGNER Tom Shone PICTURE EDITOR Akin Falope ADVERTISING 020 7324 2735 advertising@acuityjournal.co.uk PRODUCTION Rachel Young 020 7880 6209 rachel.young@redactive.co.uk PUBLISHING DIRECTOR Aaron Nicholls PRINTER Warners Midlands COVER Getty Full references can be found at college-optometrists.org/acuity © The College of Optometrists 2023 All views expressed in Acuity are not necessarily those of the College of Optometrists. All efforts have been taken to ensure the accuracy of the information published in Acuity. However, the publisher accepts no responsibility for any inaccuracies or errors and omissions in the information produced in this publication. No information contained in this publication may be used or reproduced without the prior permission of the College of Optometrists. Recycle your magazine’s plastic wrap. Check your local LDPE facilities to find out how. TO READ THIS ISSUE’S FEATURES ONLINE, AND TO CATCH UP WITH ALL PREVIOUSLY PUBLISHED ARTICLES, VISIT COLLEGE-OPTOMETRISTS.ORG/ACUITY 5 Editorial College President Professor Leon Davies FCOptom NEWS 7 News in numbers The clinical figures that count 8 News analysis Stories behind the headlines 10 Tech news New advances in technology 32

35

38

42

44

47

3 WINTER 2023 Acuity WINTER 2023

36 12 35 47 44 18

CONTENTS THE JOURNAL OFTHE COLLEGE OF OPTOMETRISTS

Optometry Tomorrow

Bitesize will take place online between 23 and 28 April 2023.

You can look forward to a week of sessions including webinars and online peer reviews. Up to six interactive CPD points can be earnt.

Look out for College communications for further details.

Show your patients that you are a member of your professional body and committed to their care, by displaying a College member sticker in your practice window.

You can order your new College window sticker online here: college-optometrists.org/membership/member-resources

Save the date! 2023

window stickers

College

elcome to the first issue of Acuity of 2023. I hope you were able to take time away from work to rest and reflect, and that you are now ready to seize the opportunities that a new year affords.

Over the past three months, I have continued to work hard as President to raise the profile of optometrists and to reinforce the College’s position as the voice of optometry across the UK.

During this time, a particular highlight for me was the College’s Diploma Ceremony – our first since 2019 – at Central Hall Westminster, London, where I was able to welcome more than 600 new optometrists to our profession. Two ceremonies ensured that the achievements of our newest members and higher qualification recipients, all of whom overcame the challenges of the pandemic, could be recognised.

I was also delighted to celebrate the outstanding achievements of five new Life Fellows and three Honorary Fellows of the College, along with colleagues whose research endeavours in the fields of optometry, optics and vision science were acknowledged by the College’s prestigious Research Excellence Awards. With such an abundance and diversity of talent on show, I was reminded that the future of our profession remains bright.

In terms of current and future practice, one area of our clinical work that is becoming ever more important is the identification and management of myopia. While there has been a long debate concerning the precise role of genetics and environmental factors in the development

PROFESSOR LEON DAVIES

CELEBRATING SUCCESS

concept in the light of recent evidence.

While I am keen not to dwell on the pandemic, those readers with young families will know from first-hand experience that the series of lockdowns led to a significant and sustained increase in screen time among children and adolescents. Our article on page 18 shares the thoughts of leading clinical academics on the impact of these behavioural shifts in terms of increasing symptoms associated with digital eye strain, dry eye disease and advancing myopia.

of refractive error, recent research has focused on the putative impact of “genetic nurture”, which describes the genetic effects transmitted indirectly from parents and other relatives to a child. Our article on page 38 gathers opinions from leading UK myopia researchers who discuss this

With a range of other topics covered in this quarter’s issue of Acuity, all that remains for me to do is to wish you all a happy and productive 2023.

Leon Davies FCOptom, President leon.davies@college-optometrists.org

With such talent on show, I was reminded that the future of our profession is bright

ILLUSTRATION: SAM KERR

5 EDITORIAL Acuity WINTER 2023

W

you

your

Acuity?

Have

come across interesting or challenging cases in

practice that you would like to share with readers of

Your case study should be approximately 1,000 words long, and illustrated with high-quality images. We will provide you with guidance on how to structure the case study, and a release form for your patient to sign. We will pay £250 for each case study we publish. To find out more, please email acuity@college-optometrists.org

NEWS IN NUMBERS

THE CLINICAL FIGURES THAT COUNT

A

WHO target to achieve a

A $10.3m grant has been given to the University of Rhode Island to develop retinal imaging to screen for early changes associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

(University of Rhode Island, 2022)

S40%

Topical antibiotics used to treat conjunctivitis in children significantly reduced the proportion with symptoms on days 3 to 6, compared with those receiving a placebo.

(Honkila et al, 2022)

increase in effective refractive error coverage by 2030 will require “substantial improvements in quantity and quality of refractive services” if it is to be met.

(Bourne et al, 2022)

In a study of 508 patients, higher intraocular pressure variability was associated with greater changes in RNFL thickness in glaucoma patients.

(Nishida et al, 2022)

A study involving 65,144 participants with a mean age of 56.8 found AI-enabled retinal vasculometry could help predict risk of stroke and myocardial infarction.

(Rudnicka et al, 2022)

As monkeypox cases reach 75,348 worldwide, a study says eye health professionals may play an important role in its diagnosis and management because of its associations with rare forms of severe ocular disease.

(CDC, 2022; Kaufman et al, 2022)

UK researchers have identified 5 genetic variants that may increase a person’s risk of myopia, the longer they remain in school.

(Astreinidou, 2022)

Acuity WINTER 2023 NEWS 7

BEHIND THE

NIC FLEMING LOOKS AT THE EYE HEALTH

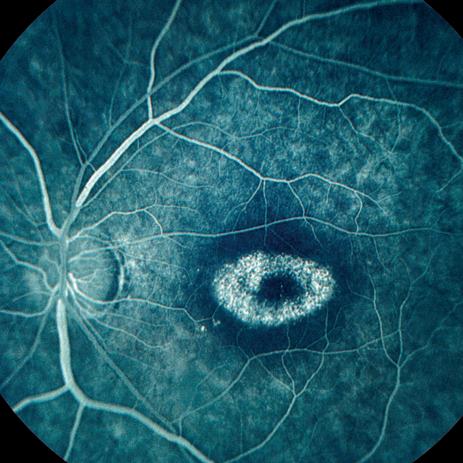

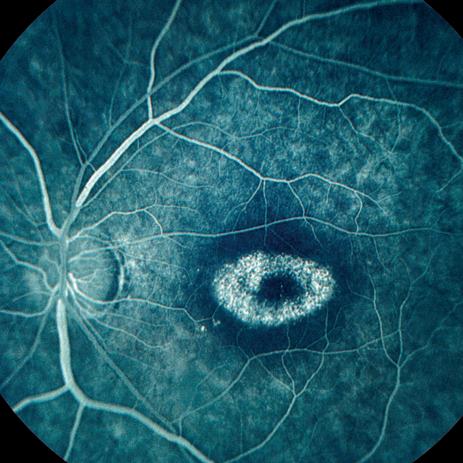

The retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) drives the reversal of this process to restore the sensitivity of opsins to light, enabling the visual cycle to begin again. A protein called RPE65 plays a key role by binding to RPE cells.

In a paper published in the journal Life Science Alliance, a team at the US National Eye Institute highlighted how previous, crystallographybased experiments

have failed to reveal the structure of a key region of RPE65.

RPE65 drives visual cycle

Researchers have identified new details about the role of vitamin A in enabling the eye to sense light. The discovery could inform the hunt for new therapies for a number of visual impairments.

When light hits photosensitive pigments called opsins in the retina, a chemical called 11-cis retinal, derived from vitamin A, is converted into the molecule all-trans retinol. This triggers chemical reactions that generate the electrical signals that form the basis of vision in the brain.

Using biochemical and biophysical techniques, the group found the region transformed into a spiral-like shape in the presence of RPE cell membranes, enabling RPE65 to lock onto the cells and keep the visual cycle functioning. Computer modelling-based simulations supported their findings.

Improved understanding of the precise role of RPE65 in the visual cycle could help researchers develop new therapies.

It is, however, likely to be some years before these findings are translated into patient benefits. bit.ly/3Z94VRQ

CLAIM

Smaller optic cups lead to oedema in astronauts

Most astronauts experience changes to the structures of their eyes and brains while in space flight, including swelling at the back of the eye called optic disc oedema (ODE).

The size of effects and time of onset of ODE varies widely between individuals. While changes tend to be reversed when crew members return to Earth, there are concerns that extended missions, such as those being proposed to the moon and Mars, could increase the risk of permanent vision problems.

SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY / NASA / ISTOCK

IMAGES:

CLAIM

8 NEWS ANALYSIS Acuity WINTER 2023

HEADLINES NEWS ANALYSIS

ISSUES THAT ARE MAKING THE NEWS

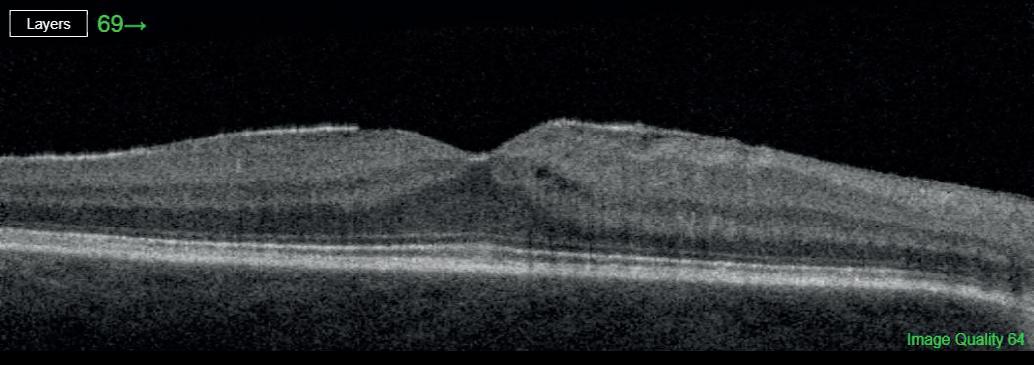

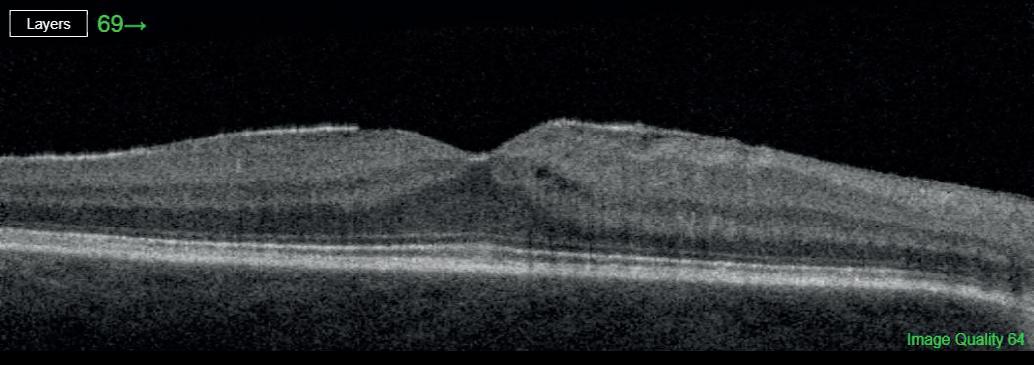

US-based researchers analysed data on 31 astronauts who spent six to 12 months on the International Space Station. They found that 23 of the astronauts developed signs of ODE. Average total retinal thickness increased from a pre-flight average of 392.0μm to 430.2μm after around 150 days in space.

It has previously been suggested that those with a small or non-existent optic cup, an area at the centre of the optic disc, are more at risk of developing ODE during spaceflight (Stenger et al, 2019).

In the new study, published in JAMA Ophthalmology, the researchers found that astronauts with small, shallow and narrow optic cups pre-flight experienced larger increases in retinal thickness while in space. No other pre-flight ocular measures were associated with ODE.

Only six women took part in the study, so it is limited in its applicability to female astronauts. It was also not possible for in-flight measurements to be collected after the same number of days, and the length of time since participants had taken part in previous space missions was not considered.

The findings, nonetheless, support the idea that astronauts with smaller optic cups may benefit from increased monitoring and use of countermeasures. bit.ly/3igZr70

CLAIM

The colour of primates’ eyes is partly the result of how much light they and their species are exposed to in their natural habitats, according to new research.

A number of studies over the past 20 years have concluded that the appearance of primates’ eyes has evolved mainly as a means of communication. If correct, variations in their size and colour would be largely down to the advantages gained from how they appear to others, both within and between species, such as through signalling gaze direction or camouflage (Kobayashi et al, 2001).

Psychologist Juan Olvido PereaGarcía, of Leiden University in the Netherlands, and colleagues at the National University of Singapore recorded data on the eyes of 77 species of advanced primates from more than 1,600 photographs. They then used these to re-assess existing hypotheses about inter-species differences in eye appearance.

In a paper published in the journal Scientific Reports, they found that primates living furthest from the equator tend to have lighter conjunctiva and are more likely to have blue or green eyes.

Blue light helps tune circadian clocks and adjust energy levels. In regions with lower light levels, bluer irises may enable blue light to reach the retina and boost energy.

Perea-García and colleagues suggest natural selection has played an important role in the emergence of blue irises in northern human populations.

They conclude that ecological factors play a greater role than communication functions across the primates they studied.

They used species’ distance from equator as a proxy for light levels, but did not take into account other factors such as habitat openness, and only included two nocturnal species in their sample.

The study also tested only existing hypotheses, which leaves open the possibility of there being other, underexplored, explanations for eye colouring that they did not consider.

bit.ly/3Q8xHy5

Light exposure varies primate eye colour 9 Acuity WINTER 2023

GENE THERAPY FOR STARGARDT DISEASE IN THE OFFING

Scientists at the National Eye Institute have found the first direct evidence that Stargardt-related ABCA4 gene mutations affect the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE).

The discovery points to a new understanding of the progression of this rare inherited blinding disease and suggests a therapeutic strategy. The research team used a new stem cell-based model made from skin cells, according to the study published in Stem Cell Reports.

Their work provides direct evidence that the loss of ABCA4 function in human RPE contributes to STGD1 cellular phenotypes, in addition to its known function in photoreceptors.

Stargardt, which causes progressive loss of central and night vision, affects about one in every 10,000 people in the UK.

bit.ly/3G6OX26

COMMON CHOLESTEROL AND DIABETES DRUGS COULD LOWER RISK OF

AMD

The use of common drugs to lower cholesterol and control type 2 diabetes could reduce the risk of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) in Europeans.

A study, published in the British Journal of Ophthalmology, found the use of common drugs to lower cholesterol or control diabetes were associated with, respectively, 15% and 22% lower prevalence of any type of AMD in European populations.

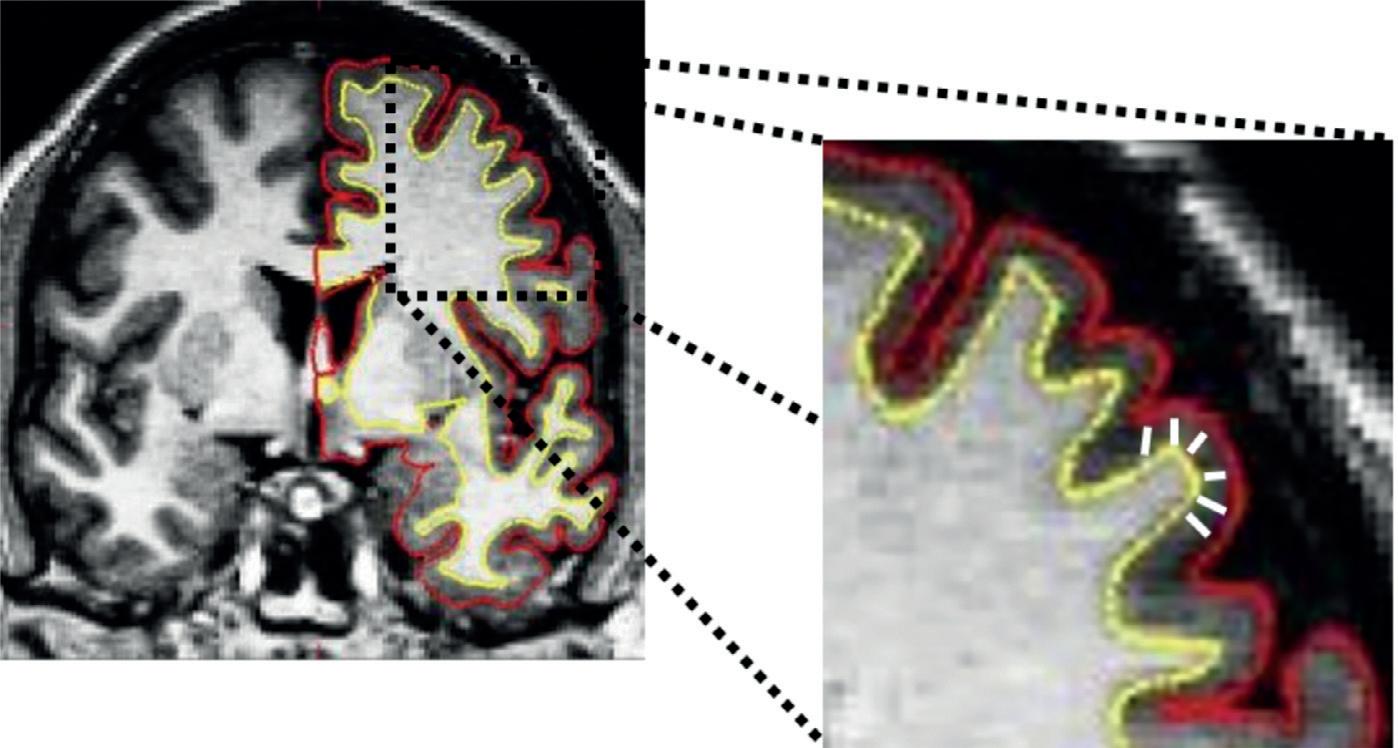

3D MAP REVEALS GENETIC INSIGHTS INTO HUMAN RETINA

3D imaging of chromatin in human retinal cells has been mapped by the National Eye Institute at high resolutions. These results have been combined with other key features of the retinal cells and gene maps to produce a series of analyses that shed light on how genes are expressed generally, but also how the complex genes associated with common and rare eye diseases may act with other factors to influence disease expression.

The study, published in Nature Communications, is the first such integration of 3D mapping with mapping of genes and other key factors.

The specialised nature of adult human retinal cells, which do not divide, provided the stability needed to investigate chromatin’s 3D structure.

TECH NEWS

According to the paper, researchers found “distinct chromatin interactions at retinal genes”, suggesting their important role.

bit.ly/3GcswbY

OCT ASSESSES DRINKING AND SMOKING DAMAGE IN FOETAL BRAINS

Over $3m in funding is helping researchers to investigate the foetal brain and assess how it is impacted by maternal drinking and smoking.

In this investigation, researchers pooled the results of 14 population-based and hospital-based studies looking at 38,694 people from France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Norway, Portugal, Russia and the UK.

AMD causes severe visual impairment among older people in high-income countries, with 67 million people in Europe alone having the condition.

bit.ly/3WFqCrp

Kirill Larin, Professor of Biomedical Engineering at the University of Houston, is developing a new imaging platform using high-resolution optical coherence tomography (OCT) to visualise dynamic changes in foetal physiology. He previously reported that prenatal ethanol exposure produces rapid and sustained decreases in bloodflow through the middle cerebral artery and pial/peri-neural vascular plexus, which supplies blood to the foetal brain. Using this new OCT platform, he will explore this discovery even further.

Larin said: “The tools will enable us – for the first time – to get dynamic, time-resolved assessment of capillary permeability and monocyte precursor invasion.”

bit.ly/3WYprCY

IMAGES: SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

10 TECH NEWS Acuity WINTER 2023

A GLANCE AT WHAT’S HAPPENING IN THE WORLD OF TECHNOLOGY

JANE VEY S

Carry on being curious

to understanding each patient’s unique experience of their refractive correction and/or eye disease, and the impact on their lives.

The dictionary defines curiosity as “an eager desire to know or learn about something”. The word comes from the Latin cura meaning “to take care of”. Dissecting the etymology helps us realise that the benefits of being curious extend beyond patient outcomes, to potentially advancing our own career and finding a healthy work/life balance.

E

ver since I dissected a pig’s eye in school biology lessons, the wonders of the ocular structure have never ceased to fascinate me. “The most important square inch in the human body,” one enthusiastic lecturer claimed. My wonder and awe of this amazing organ of sight has not waned.

The wonders of the cornea in particular. How can such a complex, multilayer cellular structure be transparent? How can such a small, thin, sensitive tissue be so powerful? 43D! How amazing that a new layer or sub-layer has been discovered (and debated) within the last decade. These facts and more are covered in our article on page 23 – a great read to remind yourself of what you learned long ago, and to discover how innovative technology, such as in vivo confocal microscopy, can aid our understanding of the corneal nerve

fibre architecture in health and disease. As technology continues to advance, I am curious to know what the next ocular phenomenon will be uncovered.

Curiosity is a quality that should be valued in the clinical world. It drives learning and the exchange of ideas in an ever-changing field and leads us to ask questions, explore and collaborate. Curiosity can help us embrace new technology, and above all allow us to get to know our patients.

Understanding our patients is critical to successful clinical outcomes. Our cover feature on page 12 explores the emerging concept of treatment burden, how it can affect patients’ adherence to medication and attending ongoing appointments, and is linked to worse medical outcomes (Alsadah et al, 2022). A respectful and healthy level of curiosity is fundamental

Taking care of our own careers and helping shape the future profession can be hugely rewarding. “I got involved out of curiosity,” Farra Raqib MCOptom answered when asked why she became involved in her local optical committee. Our article on page 44 asks a number of optometrists at all stages of their career how they got involved in the profession outside of the consulting room, and the rewards they reaped as a result. So what kind of difference will you make?

As an optometrist, enjoy being curious – continue to wonder, question and reflect for the benefit of your patients and yourselves. Curiosity has led to inventions, sight- and life-saving devices, solved world problems (and boy do we need that now!) and so much more. Potentially, there is an Albert Einstein in all of us. In his own words: “I have no special talent – I am only passionately curious.”

Jane Veys MCOptom, Clinical Editor jane.veys@college-optometrists.org

ILLUSTRATION: CAROLINE ANDRIEU

Curiosity is a quality that should be valued in the clinical world

11 Acuity WINTER 2023 CLEAR VIEW

The idea that the “treatment burden” affects a patient’s adherence to medications, adaptations and attending ongoing appointments, and is linked to worse medical outcomes, is emerging in healthcare literature (Alsadah et al, 2022).

A wide range of chronic eye conditions and comorbidities with other diseases can have an impact on a patient’s quality of life. From drops and lasers for primary open angle glaucoma to intravitreal injections for eye conditions such as diabetic macular oedema, treatment burden can be relevant to a variety of medical interventions.

One study of 22 glaucoma patients found that, while there was considerable variation in how much people experienced treatment burden, “understanding glaucoma treatment burden and its influencing factors is important as we work to deliver patientcentred care and prevent vision loss” (Stagg et al, 2021).

Janki Barai MCOptom is a specialist optometrist based at a London hospital, and works as a locum in a high-street practice and with the charity Glaucoma UK. “I’ve seen treatment burden from quite a few points of view,” she says. “It is being discussed more, mostly because there are so many other treatment options available.” Janki hears increasing numbers of callers to Glaucoma UK’s helpline asking whether their condition is lifelong, if they need to take eye drops for the rest of their lives and if there are any other options, “knowing that laser treatment and MIGS [minimally invasive glaucoma surgery] interventions might be possible”.

“When I am speaking to people on the helpline, my eyes are much more open to

Is it all getting too much?

The effort, cost and logistics of managing treatment for eye conditions can have a big impact on patients’ quality of life. Anna Scott explores what can be done to minimise their treatment burden.

12 Acuity WINTER 2023 BIG QUESTION

the quality of life that people have when we leave them with drops. There are far fewer patients that say to you in clinic: ‘I really don’t like doing this.’

“It’s only once you leave the patient on daily drops that they really start to ask, ‘What is glaucoma and what would happen if I just didn’t treat it?’”

ANXIETY IMPLICATIONS

A recent report by the Macular Society (2020) found that patients facing treatment for macular disease were suffering “significant burden”, including high levels of anxiety surrounding their appointments, and that 55% who were receiving treatment for wet age-related macular degeneration (AMD) admitted to feeling anxious “always” or “some of the time” before their appointments.

“In the survey, the feelings of anxiety did not change according to how long patients had been receiving their treatments, with half undergoing treatment for more than three years,” says Cathy Yelf, Chief Executive of the Macular Society. “This goes against the belief that over time

patients are likely to become less anxious, as they become accustomed to frequent anti-VEGF [vascular endothelial growth factors] injections. However, despite the burden, the majority of patients continue to attend their appointments, as losing their sight is not an option for them.”

Mike Horler FCOptom is Consultant Optometrist in Medical Retina at University Hospitals Sussex NHS Foundation Trust. “The mainstay of treatment for macular degeneration, diabetic macular oedema and retinal vein occlusion is regular injections into the eye,” he says. “There is a treatment burden for the patient: having to come in, every four weeks in some cases. Added to the anxiety of the treatment, we cover quite a wide geographic region. So some patients are having to travel up to two hours each time.

“Patients are often elderly, need help from family members or friends, and may need to use public/hospital transport and taxis or struggle to find parking. There may be comorbidities that mean they miss appointments because they are having other hospital treatment. What if they want to go on holiday? You can totally understand why patients feel ‘I just can’t go this week. I need a break,’ even though they know it’s potentially going to affect their vision.”

But even minor eye conditions may be prone to treatment burden. Dry eye, for example, doesn’t require clinical follow-up, but patients often present with the same complaint at their next check-up and it may be clear they have not used the drops prescribed or recommended to them.

What goes hand in hand with patients not adhering to their medication is guilt,

Reducing the burden for patients

● Ensure effective communication. Talk clearly to patients about their prognosis and what the treatment means. Follow up to ensure they are clear about both.

● Be aware of the range of services and information available to patients that you can signpost to them. Many charities offer helplines, counselling and guidance on practical issues of receiving treatment, and you can refer patients to them.

● Ask patients about transport. For example, if their bus pass doesn’t allow them to travel before 10am, they won’t be able to make a 9am appointment.

● Educate patients about potential side effects of treatment – for example, eye drops that change eye colour or encourage eyelash growth – so these things don’t come as a shock.

● If patients have carers, make sure that they too are fully informed and educated about the treatment regimen, side effects and the importance of treatment. Find out if they also need support.

● Make use of eye care liaison o cers (ECLOs, also known as eye clinic liaison o cers), who can support patients with eye drop aids and techniques for using their drops effectively. They can also provide patients with emotional support and signpost them to services available in the local area.

HELPLINES

Glaucoma UK: 01233 648170 helpline@glaucoma.uk

Macular Society: macularsociety.org

Macular Society Advice and Information Service: 0300 3030 111

RNIB Sight Loss Advice Service: 0303 123 9999

13 Acuity WINTER 2023 BIG QUESTION

Added to the anxiety of the treatment, some patients have to travel up to two hours each time

explains Patrick Gunn MCOptom, Principal Optometrist for Education and Training at the Manchester Royal Eye Hospital, as is wanting to avoid consultations or the discussion completely, leading to them dropping out of treatment entirely.

Other factors have an impact on treatment burden, such as medication supply and cost, says Patrick, citing the example of glaucoma. “It is a chronic condition that brings with it all kinds of challenges for patients, in terms of side effects of eye drops or difficulties instilling their medications,” he says.

“There are difficulties with supply from the GP. An increasingly problematic factor for patients is cost. Some simply can’t afford to pay for eye drops, either privately or on NHS prescription, because there are so many financial pressures.”

Another consideration is whether patients experiencing an improvement in their condition are less likely to experience treatment burden. Professor Robert Harper FCOptom, Optometrist Consultant at Manchester Royal Eye Hospital, says this comes down to the explanations people are provided with. “Unfortunately with glaucoma, for example, the treatment doesn’t make people better, it stops them getting worse,” he says. “There are people

The patient’s view

Maureen, in her 70s and diagnosed with wet AMD 17 years ago, has three antiVEGF injections every four weeks in her left eye.

“[The right eye] has so little sight in it, they can’t really do anything with it. But the consultant says it could be helped with laser treatment. I’m waiting to hear about that,” she says.

Maureen has had more than 70 injections since diagnosis. She also has follow-up scans. “I go to the local hospital, which either means two buses or a taxi. I also have a neighbour who sometimes takes me,” she says.

“But when I have to get a taxi it’s a bit problematic because obviously when I come out from having an injection I can’t really see anything, and the taxi drivers don’t really want to get out of the taxi [to find me].”

Generally, communication is straightforward – appointment letters for either the injections or follow-up scans and clear guidance given about her condition – but occasionally it isn’t apparent to Maureen why she

needs to go for an appointment. “I’ve had two letters recently that just give a date and time and the consultant’s name. I would assume it’s for laser treatment but I don’t know,” she says.

There’s also confusion about prognosis. “I was told about a year ago by one consultant that I may not have any more [injections] because I’ve got a lot of scarring, but then another consultant said I should have a set of four. And I thought to myself, ‘Do they not agree?’ I still don’t really know why.”

Cancellations can also be a problem. “You know the treatment isn’t very pleasant. You just want it to be over and done with,” she says. “You don’t want to be told to come back next week.’

But Maureen attends all her appointments. “I can’t say that my eyesight has improved – it’s gradually got worse.”

But she adds: ”I don’t know if it would have got even worse if I didn’t have the treatment.”

See page 28 for the second article in our ageing population series.

14 BIG QUESTION Acuity WINTER 2023

IMAGES: GETTY / ISTOCK

who want to stop using the drops because there has been no improvement. That’s when someone hasn’t been given adequate counsel.

“This is all part and parcel of expectations management and we need to have improved conversations and patient education to try to reduce the impact of that sort of effect on sticking with the treatment.”

SOLUTIONS TO THE PUZZLE

There’s also an impact on eye care practitioners and NHS budgets. NHS England hasn’t yet collated data on the impact of treatment burden on professional time, medication costs and budgets. One study calculated that the mean cost to the NHS of glaucoma treatment over the lifetime of a patient was £3,001, with an annual cost of £475 per patient, with non-drugs – including staff time spent on in- and out-patient appointments, procedures and equipment – comprising 66% of costs and drugs 34% (Rahman et al, 2012).

Treatments for macular disease represent some of the highest drug costs in secondary care, Cathy says. “Delivery of the treatment has to be in a clean room and, when first introduced, only ophthalmologists gave the injections,”

she says. “Such is the demand for treatment that nurses, orthoptists, optometrists and theatre technicians have all been recruited as injectors.”

According to Mike, “the main challenge for delivering eye care services is that it’s a big logistical puzzle – scheduling scans, injections and face-to-face appointments – especially when patients are being treated by a variety of clinicians.”

think it is also up to primary care optometrists. It’s up to GPs, pharmacists, and others, especially when patients are more vulnerable. And it starts at the time of diagnosis. Patients need to understand the diagnosis.”

Mike adds: “Optometrists are in a great place to educate their patients about the benefits of good diet, the risks of smoking and the other things that can affect the progression of a condition. They’re in a good place to refer appropriately as well.”

SUPPORTING PATIENTS

Education and support should be tailored for individuals – what works well for one person may not work for another. The glaucoma service in Manchester provides a patient support group and access to glaucoma support nurses for one-to-one advice. “Just having a variety of different options and making them available to patients is really important,” Patrick adds.

Effective communication with patients about the ongoing importance of treatment is crucial. “It is a whole eye care pathway responsibility,” says Robert. “We need to not see this as purely something that relates to clinicians seeing patients on the day in the clinic. I

Janki says the pandemic provided a learning curve for eye care practitioners about how little they could actually monitor patients’ treatment and condition when they weren’t able to see them. “We all have those patients who may not come to appointments but COVID-19 really showed how, when we can’t monitor patients, they can have quite a deterioration in a short space of time,” she says.

“Knowing that your patients fully understand what they’re taking, why they’re taking it and the condition they have, that they have got completely open communication, is really important.”

MEMBER RESOURCE

How to communicate effectively with patients: coptom.uk/3BUjOO5

There are people who want to stop using the drops because there has been no improvement

15 BIG QUESTION Acuity WINTER 2023

With a dynamic professional life that includes active interests in research, education and clinical work – not to mention her role as Clinical Lead for Ophthalmology at Central Middlesex Hospital and co-lead for the North West London Clinical Reference Group – it would be hard to imagine how Consultant Ophthalmologist Evelyn Mensah could fit much more into her life. But some issues, she says, are too important to ignore.

“If optometrists see anybody receiving any type of racism, they need to call it out. You can’t be bystanders; you need to be upstanders who are ready to challenge behaviours and take action.”

“May 2020 was something of a reckoning with the murder of George Floyd,” Evelyn says. “Because of that, and also because of what was happening to people across the world

, cal ed to be allen a eorg that, world

Evelyn Mensah Consultant

Evelyn Mensah Consultant

Ophthalmologist, talks about the steps she is taking to encourage equity.

t e o o ce ace qu qua ty St S a da d [W [WRES] S expert fo f r Lond n on North Wes e t Un U ivversiity t Heaalt l hc h are e NH N S Tr Trus u t.

“Th “ e first NHS WRES report was pu p blisshehed d in n 201 0 6 wiith th data fr from the he 2015 annual NHS staff ff survey, and thhe e la lateest repport wa was s publblisishe h d in n March h witth data ta from m 20021. Almost

during the COVID-19 pandemic – and its disproportionate impact on different populations – I signed up to become the Workforce Race Equality Standard [WRES] expert for London North West University Healthcare NHS Trust. rst NHS WRES report was published in 2016 with data from the survey, and the latest report was published in March 2022 with data from 2021. Almost 50%

of NHS staff surveyed report personal discrimination experienced on the basis of their ethnic background. When you look at the trend over the past five years, this has worsened for racial discrimination when compared to other protected characteristics, which have improved.

t e t e d o e t e past e yea s, e discrimination wh co c mparred e to ot othe h r prrottected d ch c araccte t risticcs, s which have d

“SSo o th the po p innt t of o the he WRES S pr p ograamm m e is s to ensure e that Black, Asian annd minority et e hnnic c stataff havve e eq e uaal l ac access s to o career er and receive fair treatme m nt in

“So the point of the WRES programme is to ensure that Black, Asian and minority ethnic NHS staff have equal access to career opportunities and receive fair treatment in

A RECKONING WITH RACISM

ps

16 ONE TO ONE Acuity WINTER 2023

The greatest gift: what it takes to be a surgeon

Her mother was a pattern cutter and, from an early age, Evelyn learnt the value of precise handiwork. But that is just one skill an ophthalmic surgeon needs.

“I do some of the most complex and di cult cataract surgeries using just topical anaesthesia, and probably the most rewarding part of my professional life is teaching my trainees to do topical cataract surgery. There’s nothing wrong with blocking, but when you train using just anaesthetic drops and a bit of anaesthetic inside the eye, it teaches you how to handle eye tissues with care,” she says.

“It also teaches you important communication skills because that patient is awake. I show my trainees how to speak with the patient, how to treat the patient holistically. You’re looking at their anxiety levels. You’re being compassionate, empathetic, gentle. You’re reassuring them while you’re treating them. I really do believe that eyesight is the greatest gift we can give, and I just adore training others to do it.”

the workplace, looking at nine general key indicators [see Member resource].”

WIDER EFFECTS

Race is one of the key social determinants of health outcomes. Evelyn says that, if we can reach the stage where everyone has the same experience, whether they are from an ethnic minority or not, we will have a healthier NHS workforce and better cared-for patients. In her own area of specialism – ophthalmology – there is obvious work to do.

“Nobody has looked into the experience of ophthalmology patients in a disaggregated way, in terms of their care and outcome with respect to race,” Evelyn says.

“London is one of the most diverse places in the country and we know that there are certain eye conditions that impact some populations more than others. For example, diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma or sickle cell retinopathy predominantly impact specific groups of people. But there is very little research regarding individualised treatment according to race.

“For example, somebody who is suffering with diabetic macular oedema can receive very effective treatment with an injection of anti-VEGF [vascular endothelial growth factor] agent. To be able to start the treatment in England, according to NICE guidelines, you have to

have a central retinal thickness of at least 400μm. However, there is evidence that macular thickness is smallest in Black people, followed by Asian people, when compared with Caucasians. That means Black people are already disadvantaged and would require a much greater volume of macular fluid before being able to start treatment. That is a racial disparity in itself.”

INTERNATIONAL INFLUENCE

Locally, Evelyn has been working with her trust to examine their Medical Workforce Race Equality Standard (MWRES) data in a uniquely localised quantitative and qualitative way to understand the lived experience of minoritised staff. Nationally, she has run a webinar for the Royal College of Ophthalmologists in August 2020 looking at racism in the NHS, and she was invited to host the EDI session at this year’s Royal College congress in Glasgow. Evelyn is also working with the Royal College Council to improve diversity and educational attainment.

But her international efforts aren’t confined just to WRES. As a trustee of the Moorfields Lions Korle Bu Trust, Evelyn has been one of the driving forces helping to deliver medical retina (MR) subspeciality training to ophthalmic surgeons in West Africa.

“The training, which we developed in

partnership with our West African colleagues, is a two-week residential course in Ghana following online pre-course learning, with candidates selected from the West African College of Surgeons. We ran the first MR course in December 2016, and one of the candidates from that course actually became a trainer for the second course in 2018.

“I didn’t need to attend the third and fourth MR courses in 2020 and 2021, because the system had become selfsufficient. I taught with West African trainers during the fifth MR course in 2022 and was delighted with progress. Training, educating and passing on that knowledge is far more impactful than just having people like me going out to provide clinical care.”

Now Evelyn is keen to develop another project that could impact the way ophthalmologists treat patients.

“One area I’m passionate about is sickle cell retinopathy [SCR]. There has been hardly any research into it. The last randomised controlled trial looking into laser treatment for SCR was in Jamaica in the 1990s. Even though it demonstrated that treating early with lasers reduces subsequent vitreous haemorrhage, people are still undecided about the optimum time to treat it,” she says.

“One of the reasons I was so interested in the training programme in West Africa is because ophthalmologists there see far more patients with SCR than anywhere else in the world. So why aren’t we forming a network with our ophthalmology colleagues there? That’s something I really want to do – form a network for the management of SCR and find the best way to reduce its morbidity.

“For the first time, I want to see my West African colleagues leading on this work and providing expert knowledge to the rest of the world.”

INTERVIEW: MATT LAMY IMAGES: GETTY / RICHARD H SMITH

MEMBER RESOURCE WRES

17 ONE TO ONE Acuity WINTER 2023

indicators: bit.ly/3Ck06vi

18 SCREEN TIME Acuity WINTER 2023

Helen Gilbert reports.

When COVID-19 sparked worldwide lockdowns in 2020, screen time among children and adolescents soared as they relied on computers and tablets to keep up with their education at home.

Primary school children aged six to 10 recorded the largest increases in screen usage, averaging an extra 83 minutes a day, while screen time rose by 55 minutes for those aged 11 to 17 and by 35 minutes for under-fives, a global analysis of 89 studies found (Trott et al, 2022). Leisure screen time (time not used for work or study) also increased for all age groups, said researchers at the Vision and Eye Research Institute at Anglia Ruskin University (ARU), which conducted the review.

The study, described by senior author Professor Shahina Pardhan MCOptom, Director of ARU’s Vision and Eye Research Institute, as “the first of its kind to look systematically at peer-reviewed research

Is increased screen time causing visual and eye health problems in children?

19 Acuity WINTER 2023 SCREEN TIME

papers on increases in screen time during the pandemic and its impact”, also found leisure screen time climbed for all age groups.

RISING SCREEN TIME

In the UK, 15- to 16-year-olds spent an average of four hours and 54 minutes on screens each day in 2020 (Ofcom, 2021). And in the US, there was an almost 500% increase on pre-pandemic levels, with nearly half of children aged five to 15 clocking up more than six hours each day (ParentsTogether, 2020).

The report warned that the long-term effects of this reliance on technology and screens remains unknown: “The pandemic’s influence on Generation Z [born in the mid- to late 1990s] and Alpha [born in the early 2010s onward], the youngest generations during coronavirus times, will not fully be seen for years to come.”

So should optometrists be worried? Is extended screen time having a detrimental effect on children’s eyesight, and do limits need to be imposed?

When the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) published its screen-time guidance, it said there was not enough evidence to confirm the activity was in itself harmful to child health at any age, making it impossible to recommend age-appropriate time limits (RCPCH, 2019). But that was before the pandemic struck, and before children were increasingly using screens for home schooling.

DIGITAL EYE STRAIN

Shahina said their global analysis of screen-time habits (Trott et al, 2022) discovered associations of screen time with poor eye health, including digital eye strain in children as well as inferior diet, deteriorating mental health (including anxiety) and behavioural problems such as aggression, irritability and the increased frequency of temper tantrums. Primary school-aged children increased their screen time by the most (1.4 hours),

followed by adults (one hour), and adolescents (0.9 hours). “As with any study of this type there are degrees of variability between all the research we looked at,” Shahina notes.

“However, the overall picture provides support that excessive screen time should be reduced wherever possible to minimise potential negative outcomes.”

HIDDEN ISSUES

Another review by Shahina and colleagues identified digital eye strain, often characterised by eye discomfort during or after device use, blurred vision and headaches as a risk of increased screen time (Pardhan et al, 2022).

Unstable binocular vision and dry eyes were also associated with the excessive use of screens. Furthermore, any uncorrected refractive errors that were previously tolerated, such as hyperopia, may manifest themselves more readily with increased screen time, the paper stated.

It is important to make sure that children attend their local optometrist for regular eye examinations, the authors wrote. If binocular vision is unstable, there is also an increased risk of blur, double vision and eye strain as the eye muscles constantly try to realign the eyes.

Simon Frackiewicz MCOptom, of Robert Frith Optometrists in Yeovil and Chard, Somerset, and an orthoptist and optometrist at Yeovil District Hospital, explains that excessive screen time itself is unlikely to cause changes to binocular vision, but cautions that it is very likely to exacerbate underlying conditions.

“Under normal circumstances, a child’s visual world would be dynamic and their focus would change from near to distance as they look from their work to the board, for example,” he says.

“If this environment is suddenly changed for a computer screen, then they will be required to hold sustained focus at

Tethered to tech? How optometry should adapt

Neil Retallic MCOptom, President of the British Contact Lens Association, says it has become more commonplace in practice to ask patients, including children, comprehensive questions on digital device usage and any associated symptoms. Patient management systems are also increasingly including pre-populated fields on these aspects too.

“The appreciation of the benefits of a detailed slit lamp examination in children is becoming the norm over using direct ophthalmoscopy techniques,” he says.

“Conducting a more detailed ocular surface assessment is anecdotally being reported, especially in those considered at higher risk of eye health changes due to digital device usage.

“While spectacles or contact lenses are likely to help relieve symptoms of digital eye strain linked to uncorrected refractive error, there is evidence that contact lenses can adversely impact changes in blinking behaviours that are both shortand long-term risk factors for tear film and meibomian gland changes.”

Acuity WINTER 2023 20 SCREEN TIME

Excessive screen time should be reduced to minimise potential negative outcomes

a short distance, without the natural breaks to look further away, which may cause eye strain and headaches.”

COMMUNICATION CHALLENGES

“Children may find it harder to communicate their symptoms compared with adults, which may subsequently have a prolonged impact on their ability to engage with their schoolwork,” Simon adds. Children may suffer from sleeplessness, sore eyes or a loss of social connection (RCPCH, 2019).

Dr Jignasa Mehta, Professional Lead for Orthoptics at the University of Liverpool, says it is important to detect binocular vision changes early. “In young children, where their visual system is developing (up to the age of seven or eight), a change in visual status can potentially lead to suppression of one eye so that they no longer have binocular vision or have impaired binocular vision,” she explains.

“This can impact on their ability to appreciate depth and they may develop double vision. They may also complain of headaches and discomfort.”

Professor James Wolffsohn FCOptom, Head of the School of Optometry at Aston University, says there is little evidence that binocular vision exercises help to relieve digital eye strain. “A full refractive correction, a decent night’s sleep, advice on full and regular blinking, a good diet particularly rich in omega-3 and regular breaks are the key mitigation aspects.”

LIFESTYLE HABITS

Pardhan et al (2022) also highlighted a tendency in children and adolescents to use several devices at the same time.

It cited a UK-based study of 816 12to 13-year-olds that reported 59% using more than one screen simultaneously after school, 65% using at least two screens together in the evening, 36% before bed and 68% at weekends (Harrington et al, 2021).

Best practice tips

Neil Retallic MCOptom says:

● Employ careful questioning. Ask about smart or digital device use rather than just computer use as this will provide a more accurate picture.

● Imaging devices allow for high-quality meibography assessment. Grading the quality and quantity including gland expression is beneficial.

● Look out for signs of telangiectasia, hyperemia, capping and anatomical distortions of the eyelid and meibomian gland atrophy.

● Suggest interventions such as the 20:20:20 rule (every 20 minutes look at something 20 feet away for at least 20 seconds) and regular breaks, and fully correct refractive errors.

● Consider the most effective ways of communicating these points of best practice among staff and motivating them to apply them. This is especially important given the typical initial asymptomatic presentation in the early phases.

The very act of flitting between different devices increases eye strain by 22%, says Shahina, as it entails switching distances and adjusting the accommodative power of the eyes between different devices.

The paper also suggested that smartphones and tablets viewed at shorter distances, between 20cm and 40cm, where the screen and font sizes are generally much smaller than that of a desktop computer, also result in the need for more accommodative power in the eye and a higher risk of eye strain.

Unsurprisingly, dry eye is another hazard of increased screen time. A secondary analysis of a large crosssectional study investigated the impact of digital screen use and lifestyle factors on dry eye disease within the paediatric age group (five to 16) and found that greater

digital screen exposure was a risk factor for dry eye disease, while sleep was a protective factor (Wang et al, 2022).

BLINKING PATTERNS

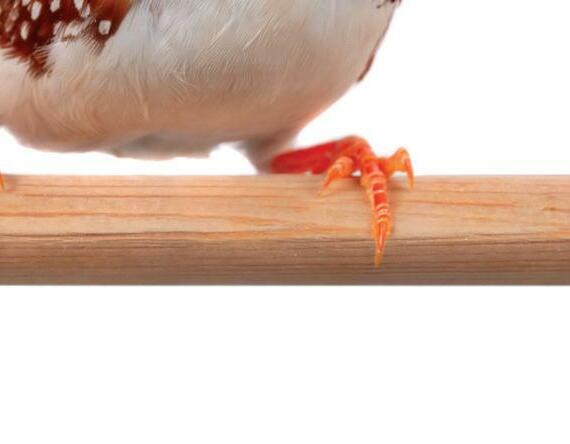

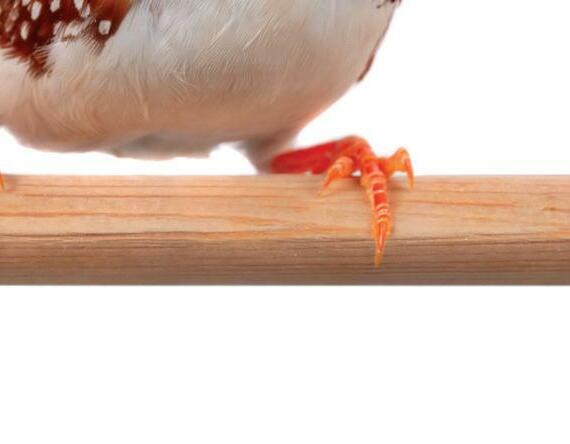

Meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) is a primary cause of dry eye disease, which can lead to discomfort due to the anterior eye drying out, especially with reduced blinking during periods of concentration.

There are approximately 30 to 40 meibomian glands (MGs) in the upper eyelid and 20 to 30 in the lower eyelid. The meibum secreted by the MGs is a vital component of the tear film, stabilising it and increasing tear film break-up time. If the quality or quantity of meibum changes, this can lead to ocular and eyelid discomfort, ocular surface disease, and evaporative dry eye (Khan et al, 2021).

Acuity WINTER 2023 21 SCREEN TIME

One study examined the effect of smartphone use on blinking and tear film function in children aged five to 16 years (Chidi-Egboka et al, 2022). Researchers found the blink rate reduced from 20.8 blinks per minute to 8.9 when children played games on a smartphone continuously for one hour. They concluded that smartphone use resulted in dry eye symptoms, despite no change in tear function evident for up to one hour.

“Given the ubiquitous use of smartphones by children, future work should examine whether effects reported herein persist or get worse over the longer term, causing cumulative damage to the ocular surface,” the authors wrote.

Extended screen time among young people was also associated with blinking behaviour consistent with patients with dry eye (Muntz et al, 2022).

James Wolffsohn, one of this study’s authors, says: “We know that digital eye strain also increases with screen time, with every additional hour/day increasing the risk of dry eye by 15%. Digital eye strain has been linked to both dry eye disease and binocular vision problems, but the balance between cause and effect is not known.”

Implementing routine clinical screening, educational interventions and developing official guidance on safe screen use may help prevent an accelerated degradation of ocular surface health and quality of life in young people, the paper concluded.

Simon notes that children, as a cohort, are in some ways more vulnerable to the effects of reduced blinking (tear evaporation, dry eye and potential inflammation of the ocular surface): “They are likely to be exposed to excessive screen use for many more years, given the ways that education and the workplace have changed in recent decades.”

A US study evaluated 172 children and discovered that excessive electronic screen use among children was associated with severe meibomian gland atrophy (MGA) (Cremers et al, 2021).

All severe cases of MGA had ocular symptoms/signs of dry eye disease,

View on the ground

Simon Frackiewicz MCOptom, Paediatric Optometrist at Yeovil District Hospital, says:

In practice, I am seeing an increase in the number of young people with symptoms consistent with dry eye syndrome, which seems to have risen further since the pandemic.

This is no coincidence, given how devices have become more widely used in the academic environment. The cohort of children attending our department typically comprises those with visible issues, such as squints, or those referred from school screening with reduced vision.

As such, the mix of refractive errors tends to be hyperopia, anisometropia and astigmatism. I would expect to see a small number of myopes referred through school screening, but this number has certainly increased in the past few years. There seems to be a fairly clear link between these myopes and excessive use of mobile phones and tablets.

There is also a definite increase in the number of younger patients presenting with symptoms of eye strain who struggle to cope with relatively small amounts of hyperopia or ocular misalignment. I have no doubt that this is the result of the increased visual demands in the modern education system. In addition to increasing amounts of myopia, I find more children are experiencing eye strain and benefit from relatively small prescriptions.

including corneal neovascularisation (29%), best-corrected visual acuity loss (41%) and central corneal neovascularisation (14%), and 86% reported four hours or more of daily screen use, while 50% were on screens for eight hours plus a day. The authors concluded that further research was needed to establish formal electronic screen use limits based on meibography grade and to evaluate correlation of autoimmune disease biomarker positivity in children with severe MGA.

Interestingly, research investigating the prevalence of MGA and gland tortuosity in the paediatric population reported mild asymptomatic levels of MGA as relatively common in the young – 42% of subjects had evidence of MGA and 37% indicated meibomian gland tortuosity (Gupta et al, 2018). It also discovered moderate-severe gland atrophy to be present.

“This calls into question our current understanding of baseline gland architecture and suggests that perhaps clinicians should be examining young patients for meibomian gland dysfunction and atrophy because it may have implications for future development of dry eye disease treatment,” the study stated.

FURTHER STUDIES

What can optometrists learn from this? The latest evidence certainly suggests that extended screen time during childhood points to increased digital eye strain, with reduced blinking making children more susceptible to blurry vision and headaches.

Shahina says the next research step would require investigating how a reduction in increased screen time would impact eye health, myopia and the wellbeing of children. In the meantime, parents and teachers have a role to play in helping children use technology responsibly, while optometrists can offer advice and be alert for – and correct – any potential eye or vision problems that may present earlier but traditionally may have taken longer to identify in children.

IMAGES: GETTY

Acuity WINTER 2023 22 SCREEN TIME

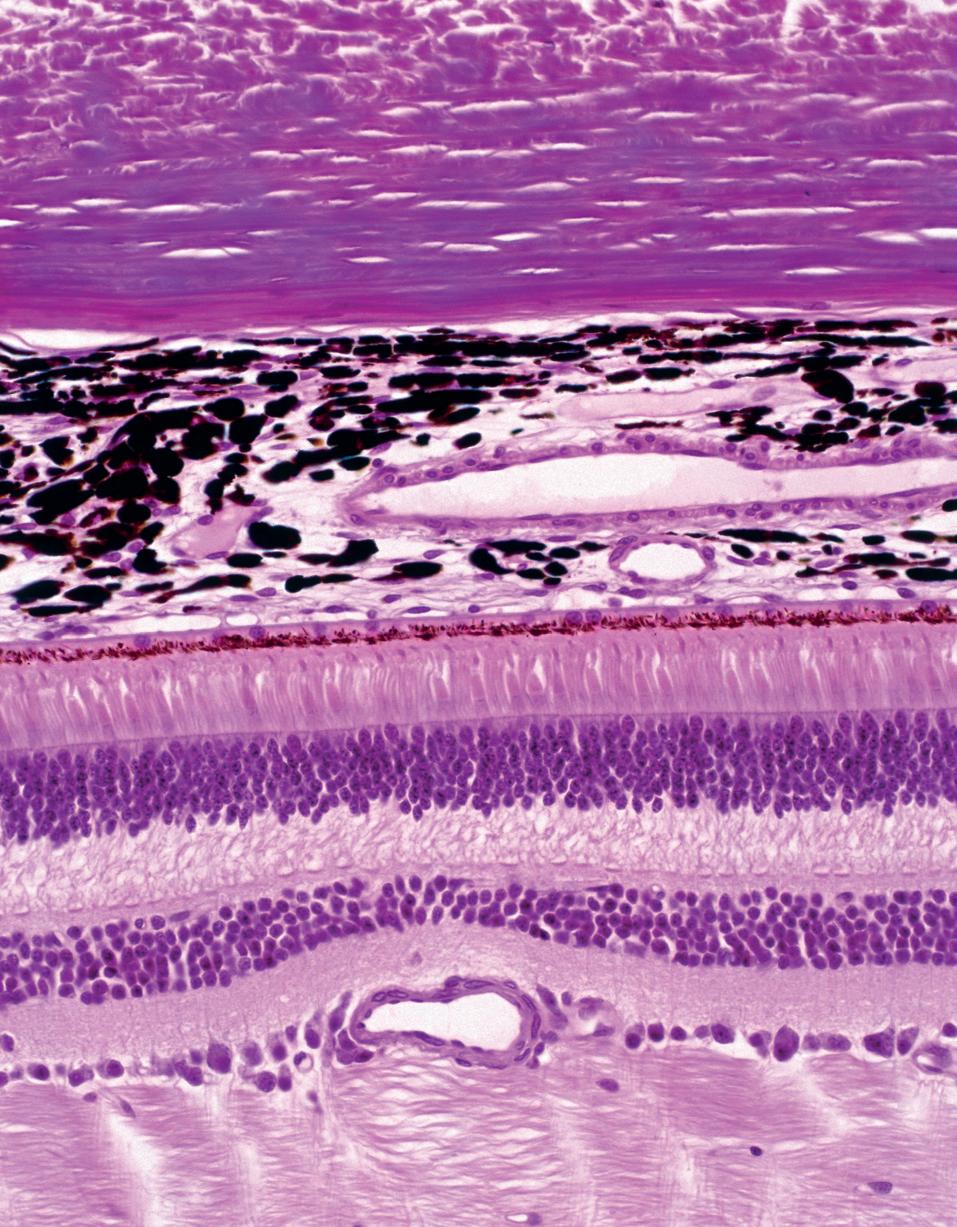

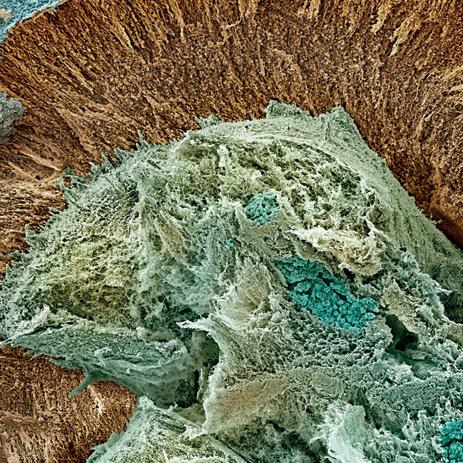

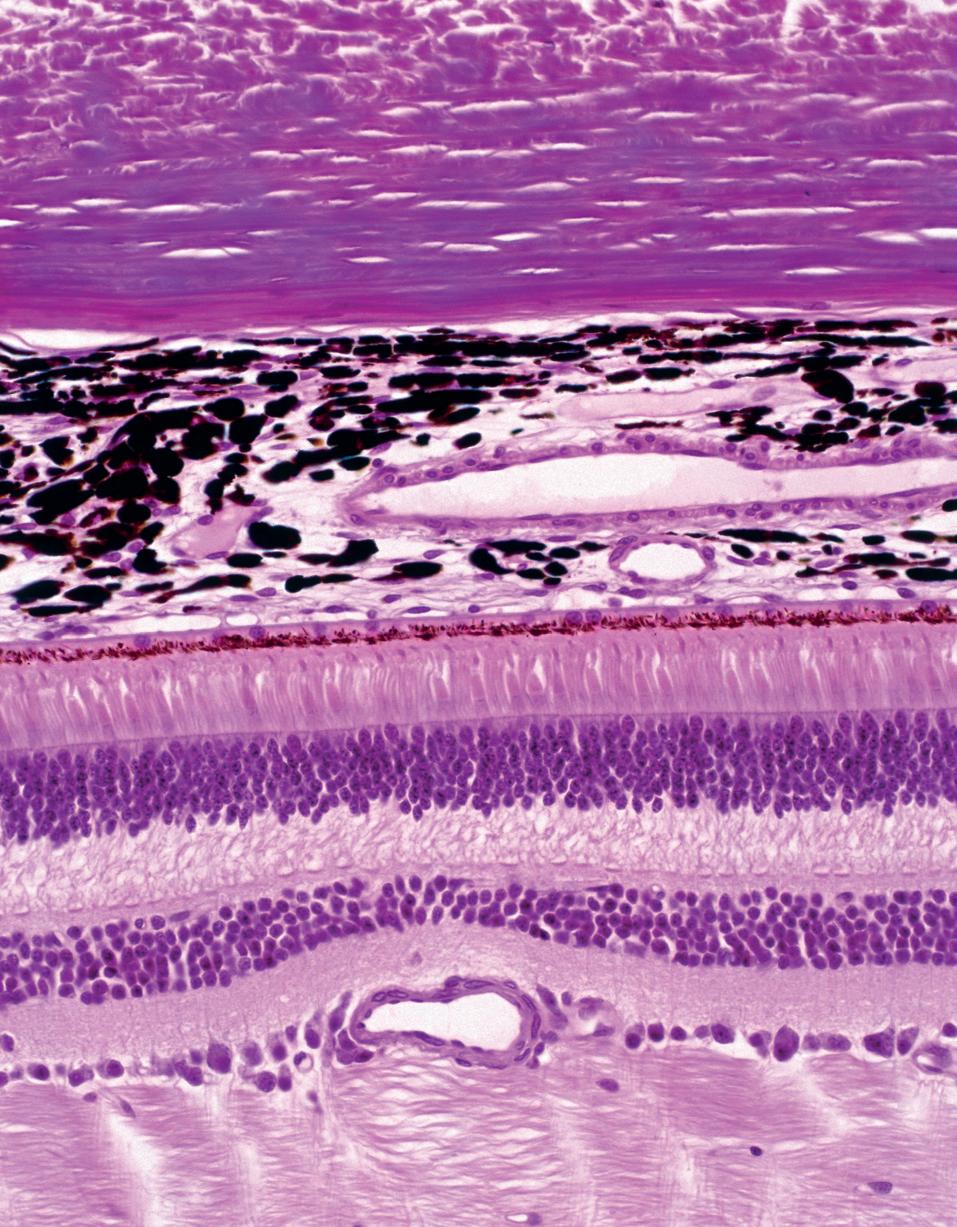

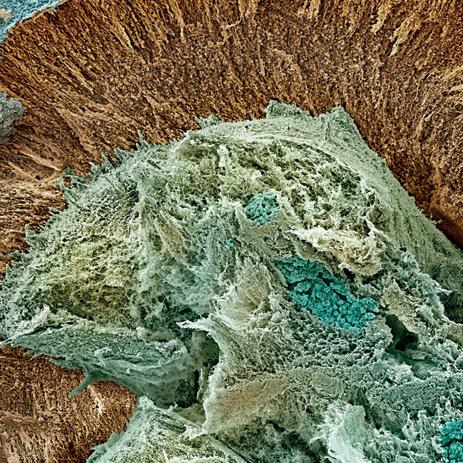

The WONDERS of the

CORNEA

Brush up your knowledge on one of the most remarkable parts of the eye. Kimi Chaddah explores the cornea’s anatomy, its capacity for healing, and promising research avenues in corneal innervation.

orneal innervation is an increasingly exciting avenue in medicine.

Examining the innervation of the cornea is beginning to be applied in new ways to understand ocular-specific and systemic diseases, from diabetes to cancer.

As the body’s most sensitive tissue, the cornea is the most densely innervated part of the body (Yang et al, 2018), receiving innervation solely from nociceptive neurons (which cause us to sense pain after physical damage). Sensory nerve endings in the corneal epithelium have a density around 400 times greater than those in the epidermis of the skin,

CPD AVAILABLE ONLINE Acuity WINTER 2023 23 REFRESHER

IMAGE: SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

C

with approximately 7,000 nociceptors per square millimetre in the cornea (Remington, 2012).

The cornea’s principal function is helping the eye to focus entering light – the cornea alone provides 65% to 75% of the eye’s total focusing power (Heiting, 2022). The cornea enables light rays to be focused on the retina with as little scatter and optical degradation as possible, and protects structures existing inside the eye.

“The cornea is largely made of collagen, which gives it strength and resistance to injury – though it’s not completely impenetrable,” explains Professor Mark Bullimore MCOptom, a scientist, speaker and educator based in Boulder, Colorado, with a PhD in vision science. “The cornea is rendered transparent by the regularity of the stromal fibres, which allows light to pass through relatively unobstructed,” he adds. “This is in contrast to the sclera, where collagen fibres are arranged much more randomly, and which is therefore opaque.”

In contrast to other bodily tissues – and other areas of the human eye – the cornea has no blood vessels. In order to refract and allow the passage of light, the cornea must be transparent.

The cornea’s features carry deeper significance. “The cornea is exquisitely clever at preventing eye infections,” says Professor Lyndon Jones FCOptom, Director of the Centre for Ocular Research and Education at the University of Waterloo in Canada. Overlying the cornea is a layer of mucin produced by goblet cells that provides protection and allows the tear film to adhere, while the closely packed epithelium forms a latticework that also prevents access to the inside of the eye.

“Tear film has lots of antibacterial enzymes in it, particularly lysozyme,” explains Lyndon. “Should bacteria contact the surface of your eye, lysozyme is very good at killing those bugs.” The blink mechanism also serves as a physical barrier against bacteria, and the epithelium safeguards the rest of the

eye from dust, germs and harmful particles.

“The cornea is a fairly stable structure – while other parts of the body grow or elongate, the cornea remains fairly constant,” says Mark. But in some cases, the cornea may become damaged. When damage to corneal nerves in the central cornea does occur, the normal nerve pattern typically presents by week four. However, the reinnervation of peripheral branches can take longer than 60 days, culminating in a less dense nerve network with lower density than that of the normal cornea.

In vivo confocal microscopy (IVCM), which is frequently used to study the cornea at a cellular level, has been used to diagnose and assess the progression of diabetic neuropathy (Misra et al, 2022). In evaluating corneal innervation, IVCM is also able to detect corneal nerve abnormalities, which may be present in various ocular and systemic conditions such as dry eye disease, glaucoma, diabetes and migraine, where decreased corneal nerve density and sensitivity have been observed (Patel et al, 2021).

CHANGES TO THE CORNEA

“Pathophysiological changes to the cornea will depend on the type of damage and which level of the cornea is affected,” explains Don Williams FCOptom, the first optometrist in the UK to gain formal accreditation in laser procedures.

When corneal nerves are damaged

as a result of disease, surgery or trauma, this can lead to diminished corneal sensitivity, epithelial defects and possible visual impairment, creating eye pain, light sensitivity, inflammation and fatigue.

After an epithelial abrasion, the corneal epithelium usually renews itself rapidly, typically repairing in 24 to 48 hours in the majority of cases.

“Corneal healing is mainly dictated by four main processes: cellular migration, proliferation, differentiation and extracellular matrix remodelling,” says Don. “Any trauma that disrupts one or more of these healing processes will cause either temporary or, in more severe cases, permanent damage to the cornea.”

POST-REFRACTIVE SURGERY

“As a general rule, any refractive surgical procedure will cause trauma to one or more of the corneal layers,” says Don. “As our understanding of corneal response post-refractive surgery improves, it is becoming clearer that stromal keratocytes play a crucial role in defining the result of refractive surgery.”

Photorefractive keratectomy, or PRK, aims to correct vision, including myopia, hyperopia and astigmatism. Unlike Lasik procedures, the most-performed refractive surgery in the UK, PRK does not leave an

The cornea: Fast facts

● The cornea is 300 to 600 times more sensitive than the skin.

● The cornea is one of the fastest healing parts of the body.

● Corneal sensory nerves have a neurotrophic effect, influencing corneal metabolism and aiding in tissue maintenance.

● The cornea in a young person prevents over 90% of UVB and 45% of UVA from reaching the posterior structures of the eye.

(Rosenblatt et al, 2020; Delic et al, 2017; Remington, 2012)

IMAGE: SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY 24 REFRESHER Acuity WINTER 2023

epithelial flap in the cornea, which may result in an increased risk of complications should an infection or injury to the eye occur.

“Histologic studies have reported an increase in the epithelial thickness (hyperplasia) following PRK,” says Don. “Failure to re-establish a normal epithelial basement membrane to promote firm epithelial reattachment contributes to epithelial breakdown [Chao et al, 2014].

“It’s not uncommon for PRK patients to report symptoms of dryness and foreign body sensation suggestive of subclinical corneal erosion.”

Almost half the patients who have Lasik experience dry eye after the surgery, with evidence indicating that this can be attributed to alteration of corneal innervation (Chao et al, 2014). “Lasik uses an excimer laser to remove tissue from the cornea through a process of photoablation,” explains Don. “Stromal and sub-basal nerve damage occurs during flap creation and the excimer stromal ablation – and damage to these sensory nerve fibres of the cornea decreases basal and reflex tearing, slows the blink rate, decreases corneal sensation and impairs neurotrophic effect of the corneal epithelial cells.”

CATARACT SURGERY

“In cataract surgery, you make a small – 2mm to 2.2mm – incision to the cornea,” says Samer Hamada, an ophthalmic surgeon at Queen Victoria Hospital NHS Foundation Trust.

“Corneal wound repair after cataract surgery is complex and facilitated by fibroblasts – if not optimised, it can lead to the distortion of the cornea and the creation of new refractive error, such as astigmatism – which might affect final visual outcomes after cataract surgery,” he explains.

“Secondly, damage to the endothelial layer of the cornea can lead to cornea swelling, particularly around the main incision area. A more severe form of corneal endothelial damage would lead

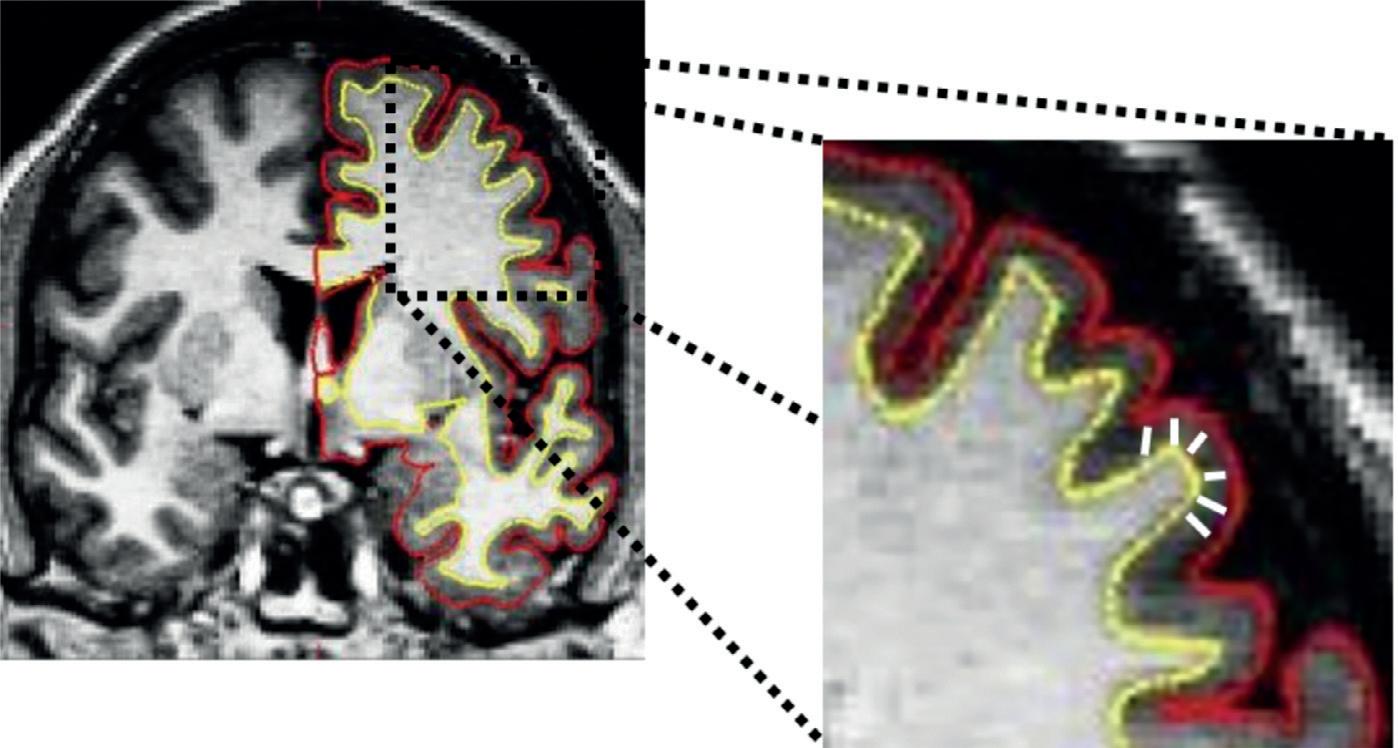

Layers of the cornea

The cornea is traditionally considered to contain five layers: the epithelium, Bowman’s membrane, the stroma, Descemet’s membrane and the endothelium. A potential sixth pre-Descemet’s (sub) layer (Dua’s layer) has been recently identified (Dua et al, 2013).

● Epithelium: a regenerative layer that covers the front of the cornea.

● Bowman’s membrane: the basement membrane of the epithelium, comprising collagen fibres, a protein that structurally reinforces the cornea.

● Stroma: provides mechanical strength to the cornea, maintains corneal transparency and serves as the main refractive component of the cornea. The stroma makes up 80% to 85% of corneal thickness.

● Descemet’s membrane: a relatively transparent matrix serving as the basement membrane of the endothelium.

● The endothelium: a single layer of specialised cells responsible for corneal clarity by removing water from the corneal stroma.

to corneal decompensation or failure where the cornea becomes swollen and loses its transparency.”

While corneal sensitivity may deteriorate after long-term contact lens (CL) wear, this change in sensitivity does not appear to be correlated with an alteration in the number of nerve fibre bundles in the sub-basal plexus of the cornea. “The worst-case scenario for a CL wearer and for the CL clinician is to have a patient who has an infection, such as microbial keratitis,” says Lyndon, with unpermitted sleeping in CLs being the main risk factor.

NEW POSSIBILITIES

But the cornea has opened up new realms of possibility in the medical world. Corneal innervation can be measured in a noninvasive manner, rendering it a possible surrogate biomarker useful for skin biopsy

measurements. Because of this feature, Ferrari et al (2013) compared hindpawskin and cornea innervation in mice exposed to neurotoxic chemotherapy. Both tissues exhibited highly correlated and dose-dependent nerve fibre damage, indicating that corneal nerves can potentially serve as a surrogate marker for skin peripheral innervation.

“There’s a lot of interest in using CLs and interacting with the ocular surface in some way to be able to detect ocular disease and systemic diseases,” says Lyndon. The composition of the tear film is of particular interest, including a variety of features that may be of interest when looking at systemic diseases. “Glucose in the tear film can be used to estimate glucose levels in the blood, which determines diabetes.”

Meanwhile, the presence of cancer markers on the tear film – as well as markers of Alzheimer’s disease – speaks to the potential opportunities for biomarkers in the tear film to indicate systemic disease. “The growing interest in tear film biomarkers will hopefully enable smart CLs to detect these biomarkers and provide valuable information about a variety of systemic diseases,” says Lyndon.

The potential future applications for studying corneal innervation are vast. The cornea is a vital part of the eye, and more exciting avenues concerning corneal innervation are continuing to emerge.

25 REFRESHER Acuity WINTER 2023

After an epithelial abrasion, the corneal epithelium usually renews itself rapidly

n recent years, optometrists across the UK have been increasingly involved in providing eye care over and above routine eye examinations in many settings, including primary and secondary care. While this has been driven by the need to manage the increasing demand and pressures on NHS services (exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic), it also reflects the willingness and desire of optometrists to demonstrate to their patients their role as clinicians first and foremost – and that they are more than capable of managing more complex patient needs.

For me, as an independent prescribing (IP) optometrist, it has led to even greater professional satisfaction to provide more care locally, quickly and often without the need to refer. This has the benefits of improved patient satisfaction within the practice and improved knowledge of the profiles and capabilities of optometrists more widely. This is critical in educating the public to recognise that optometrists should be their first point of contact when it comes to any eye problem they may experience, while helping to ensure appropriate signposting by other clinicians. Indeed, it is not uncommon for patients to approach their GP or

pharmacist before attending their optometrist, where the original problem could have been addressed more quickly.

Several studies have investigated the clinical decision-making of IP optometrists in eye casualty, where diagnosis, prescribing decisions and management advice/planning was compared to those of their ophthalmologist colleagues – statistical metrics for assessing agreement was very good in each domain, thus validating their ability to manage high-risk cases (Todd et al, 2020; Hau et al, 2007).

But what of the evidence for primary care or community settings? How do we know that patients’ needs are being safely and effectively managed here? Reports of locally commissioned urgent or emergency eye care service evaluations are convincing – a recent study published in the College’s own journal Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics showed that local practice-based IP optometrists were able to successfully manage patients to resolution in the majority of cases, resulting in reduced

BROAD

I Acuity WINTER 2023 26 CLINICAL

Dr Paramdeep Bilkhu MCOptom, Clinical Adviser for the College, on the scope of practice and eye care services in optometry practices.

NOTES

onward referral to local hospital eye service (HES) departments (Cottrell et al, 2022).

Likewise, these results were also observed in a community-based acute ophthalmology service delivered by specially-trained IP optometrists, where only 4% of cases were referred to the local HES (Ansari et al, 2022). In a literature review of locally commissioned enhanced eye care services (including those for cataract, glaucoma and red eye), the authors found that patient satisfaction was high with appropriately trained optometrists able to safely deliver clinically effective care (Baker et al, 2016).

While there are limited cost-effectiveness evaluations (Baker et al, 2016), these studies, together with other successful examples of local eye care provision (Konstantakopoulou et al, 2018), including during the COVID-19 pandemic (Kanabar et al, 2022), provide robust support for maintaining and growing commissioned eye care services (Williams et al, 2022), further recognising optometrists as important clinicians with decisionmaking capability and thus helping tackle the burden on the NHS.

EXPANDING YOUR SKILL-SET

These studies should also encourage optometrists to recognise that they can make a significant positive impact on their

local community and feel confident that they can do more. However, I am often asked by members how they can start to offer more for their patients, even though they may already possess higher qualifications. I reply by saying that obtaining a relevant qualification is typically only the first part of the puzzle. In addition to improving their knowledge, they also need to gain experience and skills to perform or offer investigations or treatments competently – to increase their scope of practice beyond core competency safely. As a health professional it is essential to recognise your own scope of practice, which will vary from one clinician to another. While this may appear challenging, I would argue that optometrists are already equipped with the tools to do so by engaging with reflective learning through regular clinical audits and CPD activities such as peer discussion.

To offer eye care above your current scope of practice, recognising your abilities and identifying any gaps in knowledge, skills and experience in order to provide additional eye care activity is an important first step towards creating an action plan to address these gaps. The College has recently published new guidance on expanding scope of practice, setting out eight key principles you should consider and reflect on to help ensure you can do so safely and effectively.

Expanded roles within the HES have taken and are continuing to take place, with optometrists typically undertaking local training and accreditation to perform roles such as intravitreal injections and specific laser procedures that would otherwise usually be undertaken by our medical colleagues (Gunn et al, 2022).

It is hard to escape the observation that an increasingly capable workforce through an expanded scope of practice, supported by the available evidence, is critical to delivering eye care to an increasingly complex patient mix – ultimately broadening the type and scope of eye care available locally and improving patient outcomes and experience. Moreover, I believe this will almost certainly lend itself to better job satisfaction by helping to fulfil the desire to serve our patients’ clinical needs better.

HORIZONS

COLLEGE RESOURCES

Expanding scope of practice principles for optometrists: coptom.uk/3hGEySy Clinical audit in optometric practice: coptom.uk/3PIX4pT

Exp x for or Cli Cl C n cop

IMAGE: GETTY

As a health professional it is essential to recognise your own scope of practice

Acuity WINTER 2023 27 CLINICAL

NOTES

rian Brown, 79, was diagnosed with wet agerelated macular degeneration (AMD) 10 years ago. “I used to be a table tennis player, but I couldn’t see the ball or the lines on the table any more, so I had to stop. And I’ve been unable to drive for the last year, as I cannot read a licence plate up to 20 metres away. Giving up my driving licence has been difficult to accept.”

In the second part of our series looking at the impact of ageing, Léa Surugue asks how to support older patients whose quality of life has been affected by age-related eye disease, and reviews the treatments available.

BLiving with his wife in High Wycombe and volunteering as treasurer of the local Macular Society group, Brian still leads an active social life. But his condition has affected his independence. To get into the clinic every six weeks for his anti-VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factors) injection, he must now take a taxi or rely on his son to drive him.

It’s surely not an unusual story, particularly since wet AMD is just one of the eye diseases affecting older people. A US study estimated that 57.5 million people worldwide are affected by primary open-

angle glaucoma. By 2020, it is expected that around 76 million people will suffer from glaucoma, a number estimated to reach 111.8 million by 2040 (Allison et al, 2020). Meanwhile, a worldwide study found that, in 2010, cataract was the cause of sight loss for one in three blind people, and the cause of visual impairment for one in six visually impaired people (Khairallah et al, 2015).

Losing sight, especially at an age where independent living may already be more complicated by comorbidities, can have a significant impact on quality of life, with repercussions on physical and mental

Acuity WINTER 2023 IMAGES: ISTOCK 28 AGEING

wellbeing, as well as on social life and family – an estimated five million (or 40%) of UK grandparents are relied upon to provide regular childcare for their grandchildren (Age UK, 2017). Many older people struggle to live with eye disease. Daily activities, the ability to take care of themselves and even to live independently are sometimes threatened, which also impacts on their wider families.

CLEARER PICTURE

Lately, studies to obtain objective data regarding the experiences and the

Ageing and eye health series

challenges of older people with an eye condition have been conducted. Access to this data is necessary if we are to develop solutions to improve patients’ quality of life based on their actual needs – and allow as many people as possible to continue carrying out their daily activities independently.

Driving, for example – which became an insuperable challenge for Brian – is an issue that is taken seriously by the College. Not being able to drive due to eye conditions limits patients’ independence. And if they continue driving, the risks may be high.

A report by the College, Visual impairment and road safety among older road users (see College resources), suggests an association between injury-collisions and visual impairment and health.