The Redfern Gallery

Centenary Exhibition: Part I

100 Years of The Redfern Gallery

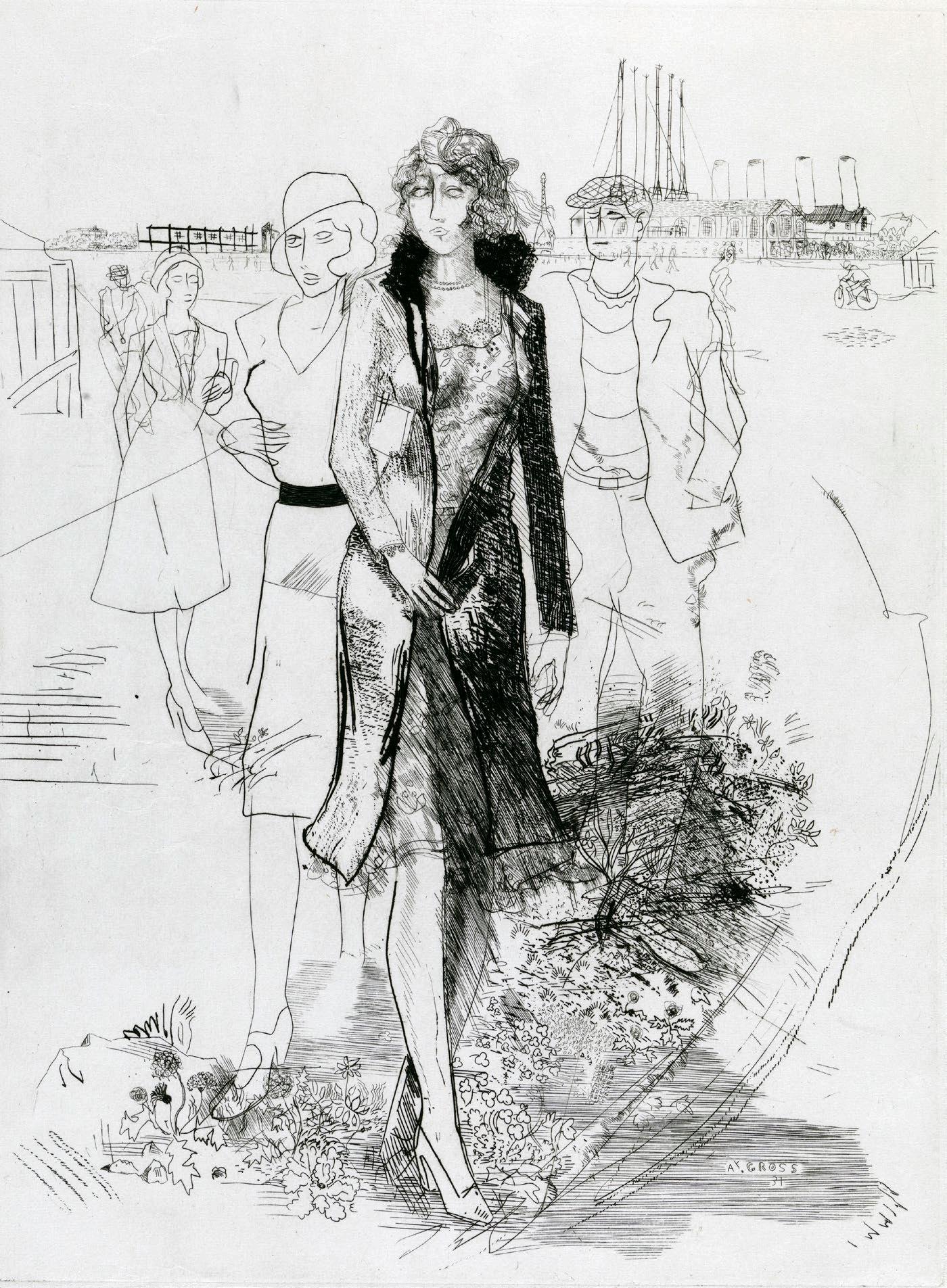

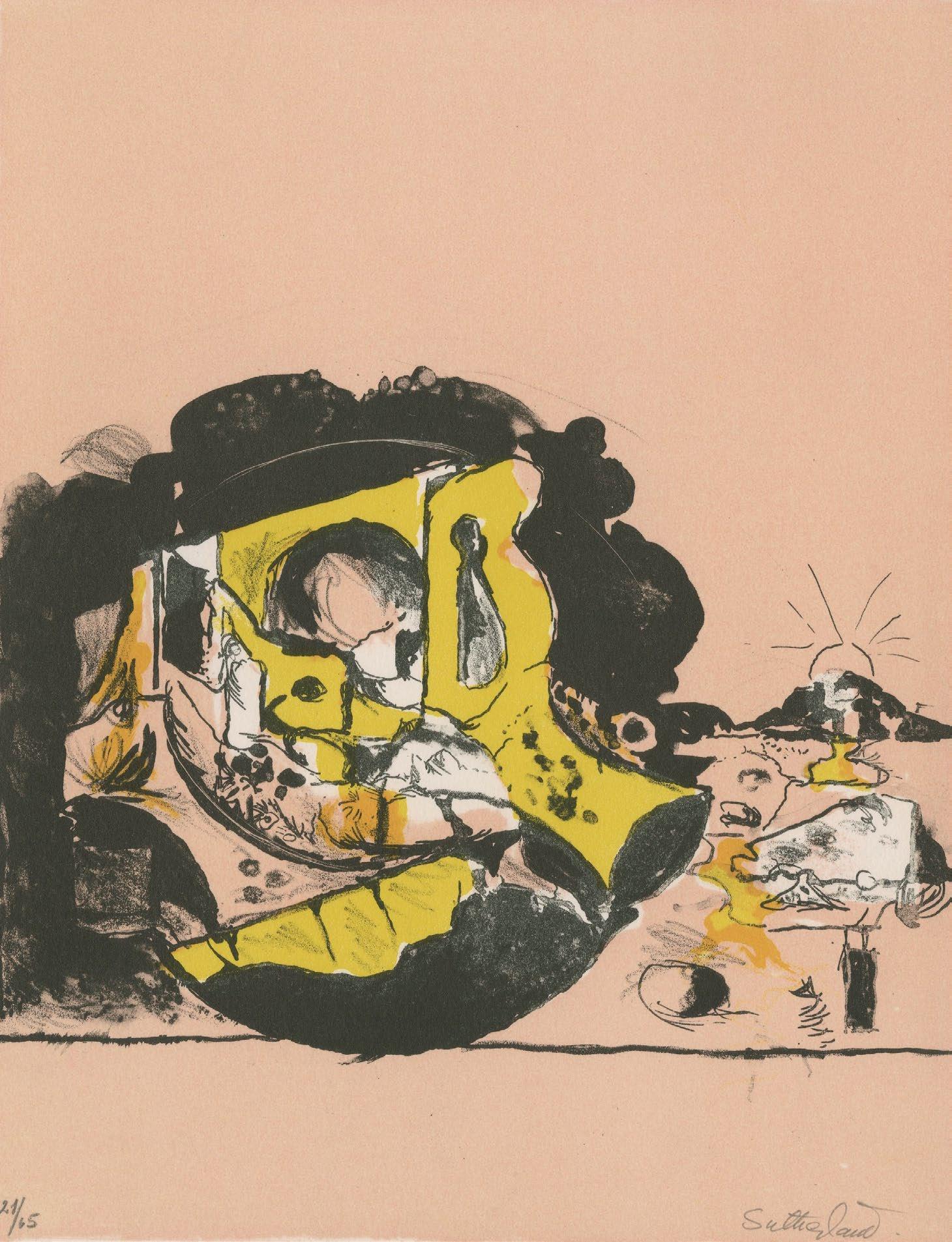

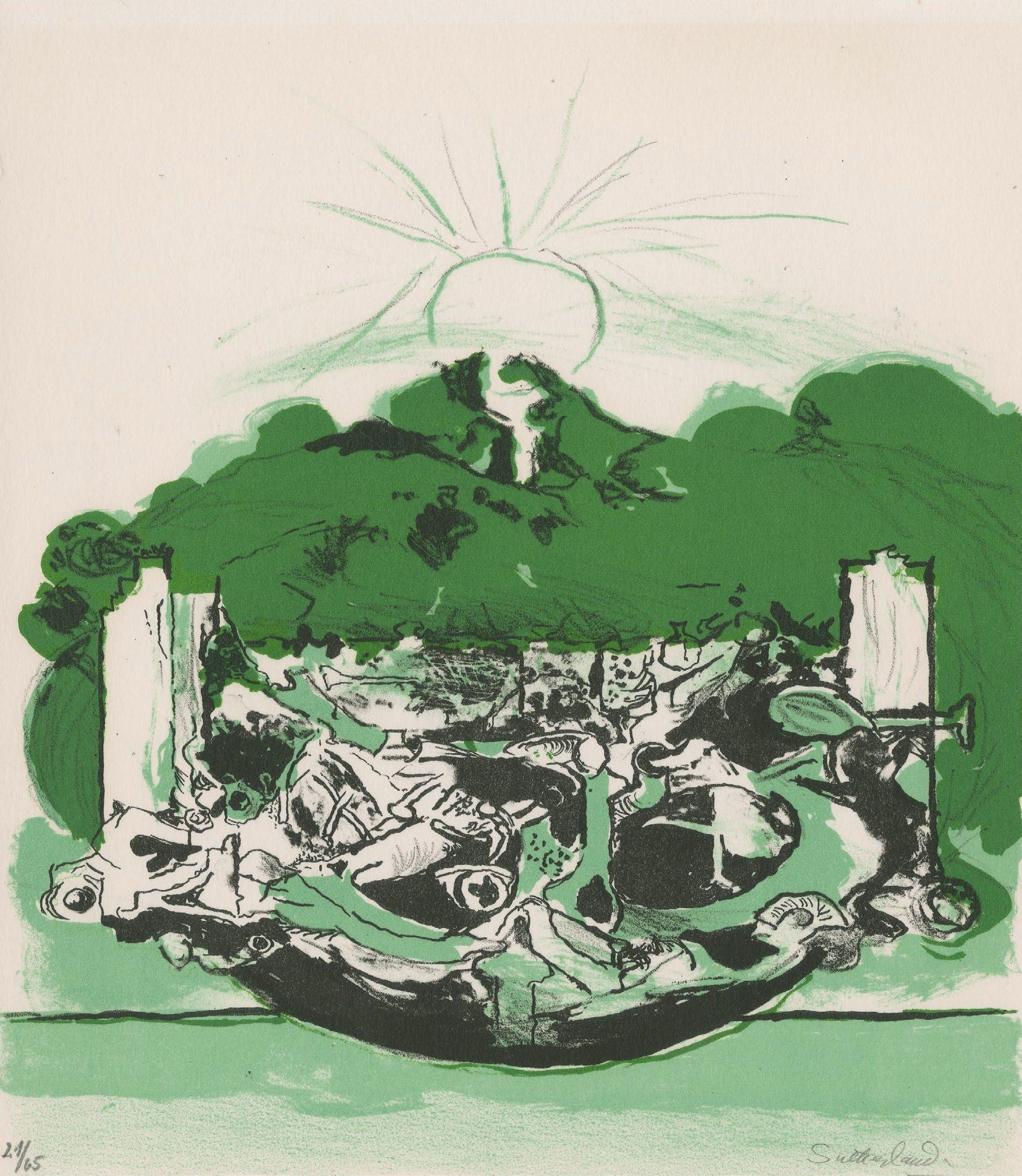

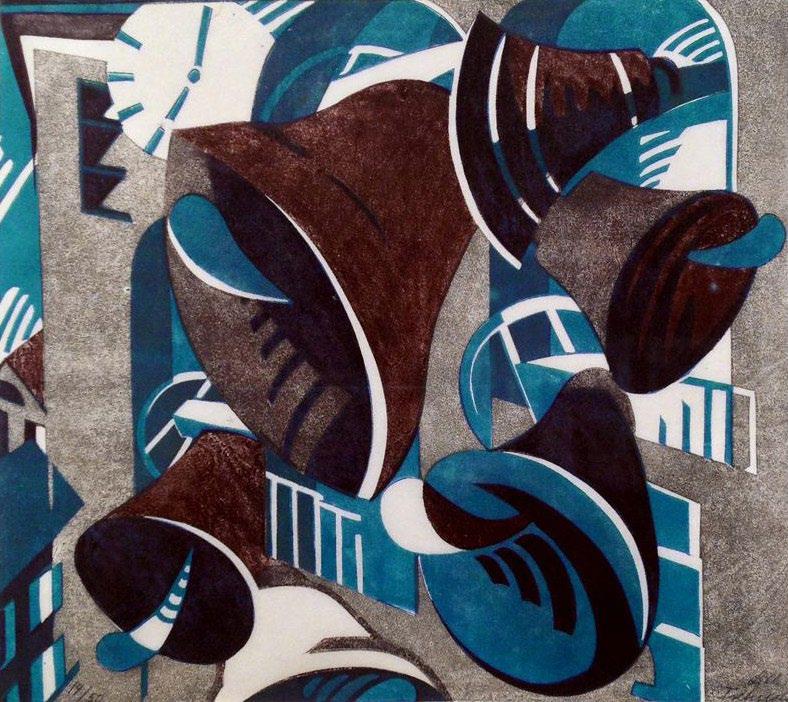

The British painter and printmaker Sybil Andrews first exhibited at the Redfern Gallery in 1929. She was working as a secretary at the progressive Grosvenor School in Pimlico, where she was a student of Claude Flight. Two years earlier, after a successful solo show with the gallery, Flight had been invited to organise the first of what would become an annual exhibition of British linocuts, a medium he was busy revolutionising with his distinct and dynamic designs. He filled the show with his own prints and those of his top students, several of whom ended up being represented by the Redfern.

Andrews was among them, and her Steeplechasing (1930) is the frontispiece of the first of two celebratory exhibitions marking the Redfern Gallery’s centenary. Three horses printed from three blocks (Chinese orange, alizarin purple madder, Prussian blue) leap over a birch fence in an elegant arc. The jockeys pitch forwards, hands forward so as not to yank their steeds in the mouth, heels safely down. Despite the mostly blank sheet of paper, there’s a sweeping sense of perspective and the hint of a horizon; the scene has a sharp linearity, though there’s a softness to the ground. It’s a striking image, and one that captures a moment in time, tantalisingly suspended.

You could say that, like Andrews’ jockeys, the Redfern Gallery’s reputation has been built upon a series of well-executed leaps of faith. Founded as an artists’ co-operative in 1923 by Arthur Knyvett Lee and Anthony

Maxtone Graham, who rented a couple of rooms on the top floor of Redfern House at 27 Old Bond Street, it has always focused on emerging talent. In 1924 the gallery hosted an exhibition of work by Royal College of Art students, including Edward Burra, Barnett Freedman and Eric Ravilious, as well as Barbara Hepworth and her Yorkshire counterpart Henry Moore, neither of whose carvings had been shown before. Also established that year was an annual Summer Exhibition, not unlike that of the nearby Royal Academy, which offered further opportunities to champion plucky up-and-comers.

Several of those budding artists went on to become driving forces in modern British art, among them Hepworth, whose sculpting practice and printmaking go hand in hand. Included in this year’s centenary exhibition is Three Forms Assembling (1968-69), a lithograph of two wonky rectangles (one partially filled with a sunny yellow spread, the other a sooty black) and a perfectly round circle gathered together in a small grid. In stone and on the page, the artist embraces free-flowing abstract shapes that invite the viewer to consider their arrangement and the gaps in between. Here, sharp and smudgy lines evoke presence and absence.

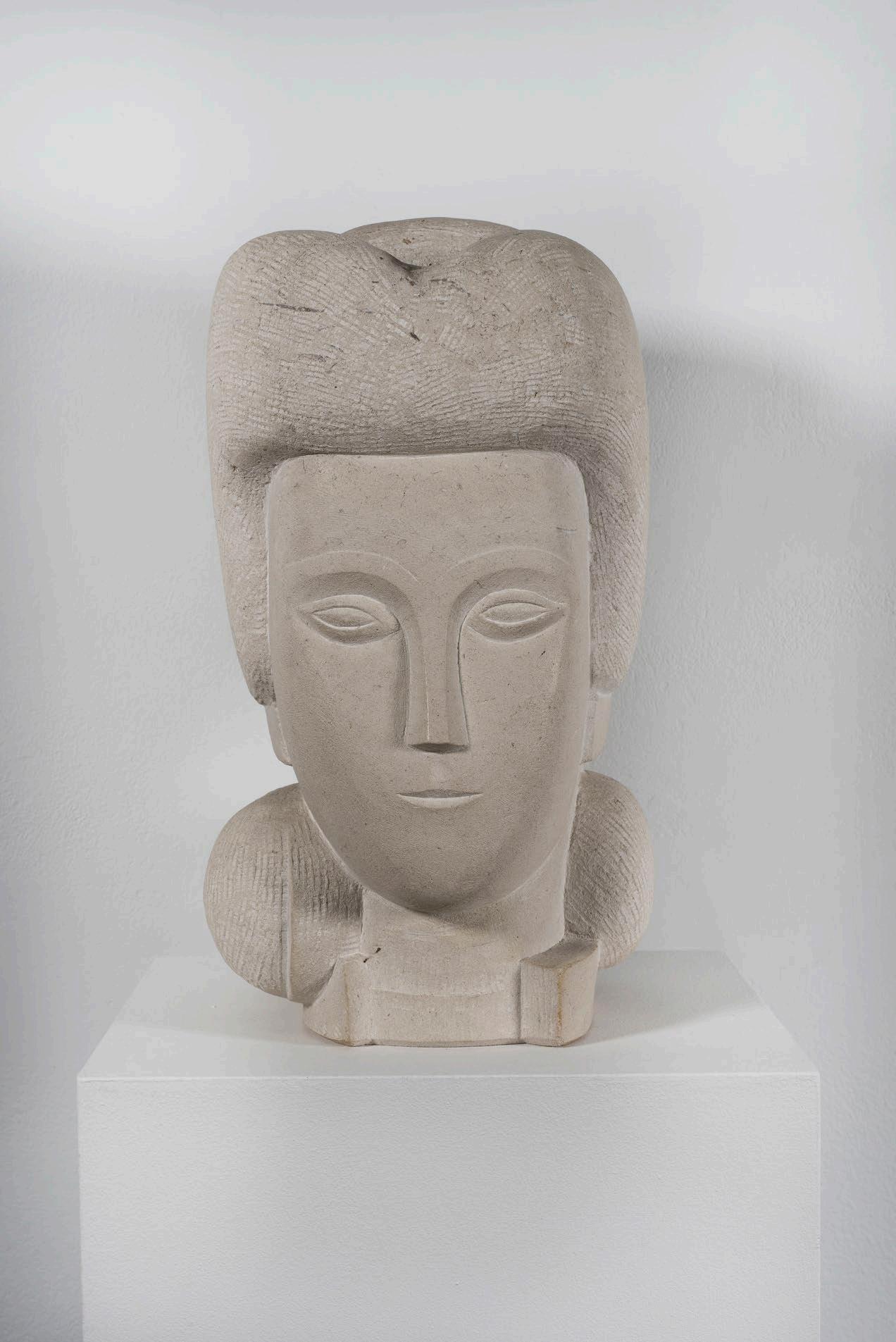

Both Hepworth and Moore studied under Leon Underwood, the great sculptor, painter and print-maker behind Brook Green School of Art in Hammersmith. A posthumous retrospective was staged at the gallery to commemorate his centenary in 1991, and

after falling out of fashion during the 1950s and ’60s, with Redfern now representing his estate, his reputation was restored. Also included in the first of this year’s celebratory shows is Iceland’s All (1923), a group portrait of a crowd labouring beneath a clouded sky, painted during a trip to Iceland that involved trekking from Reykjavik to Husavik.

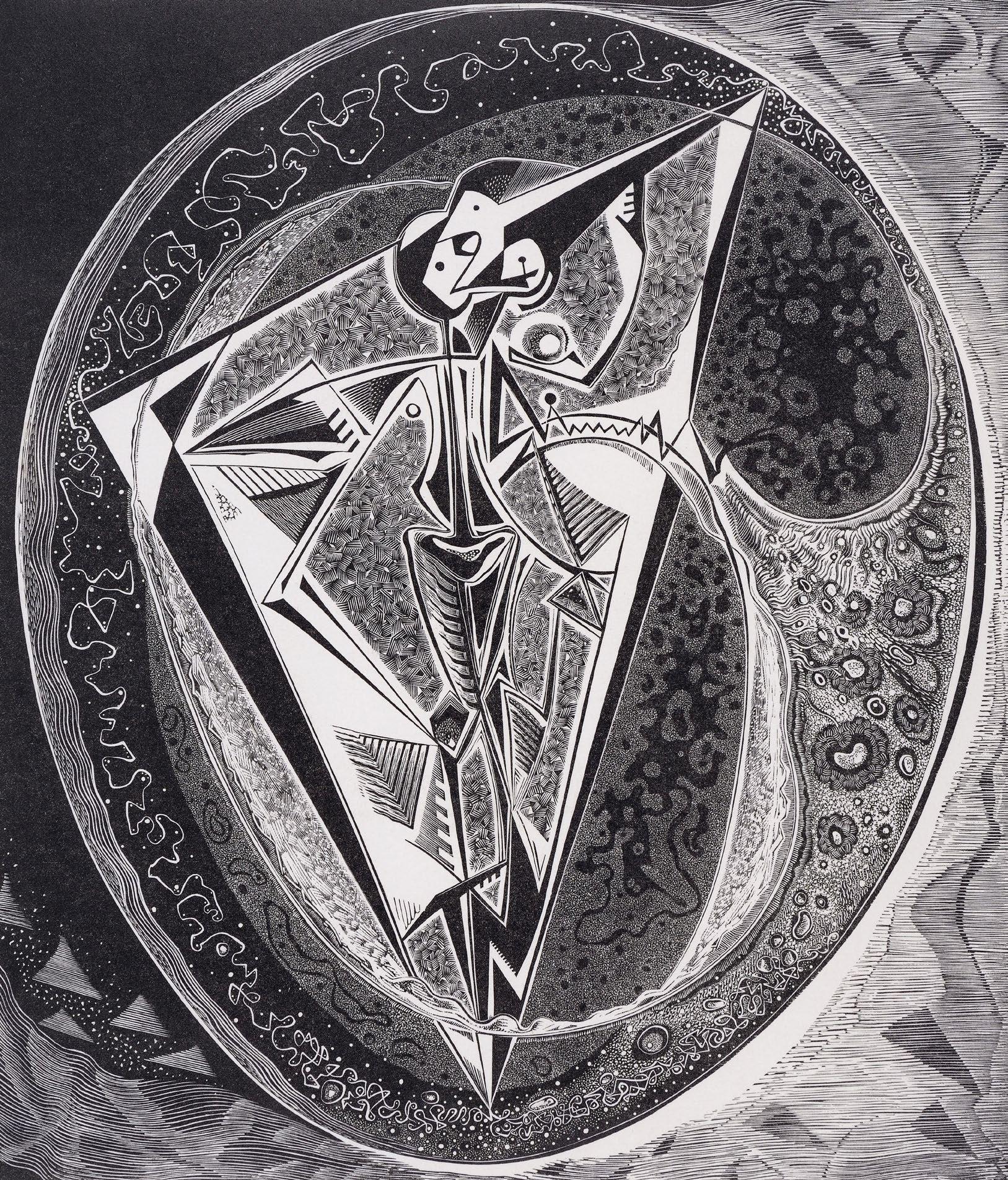

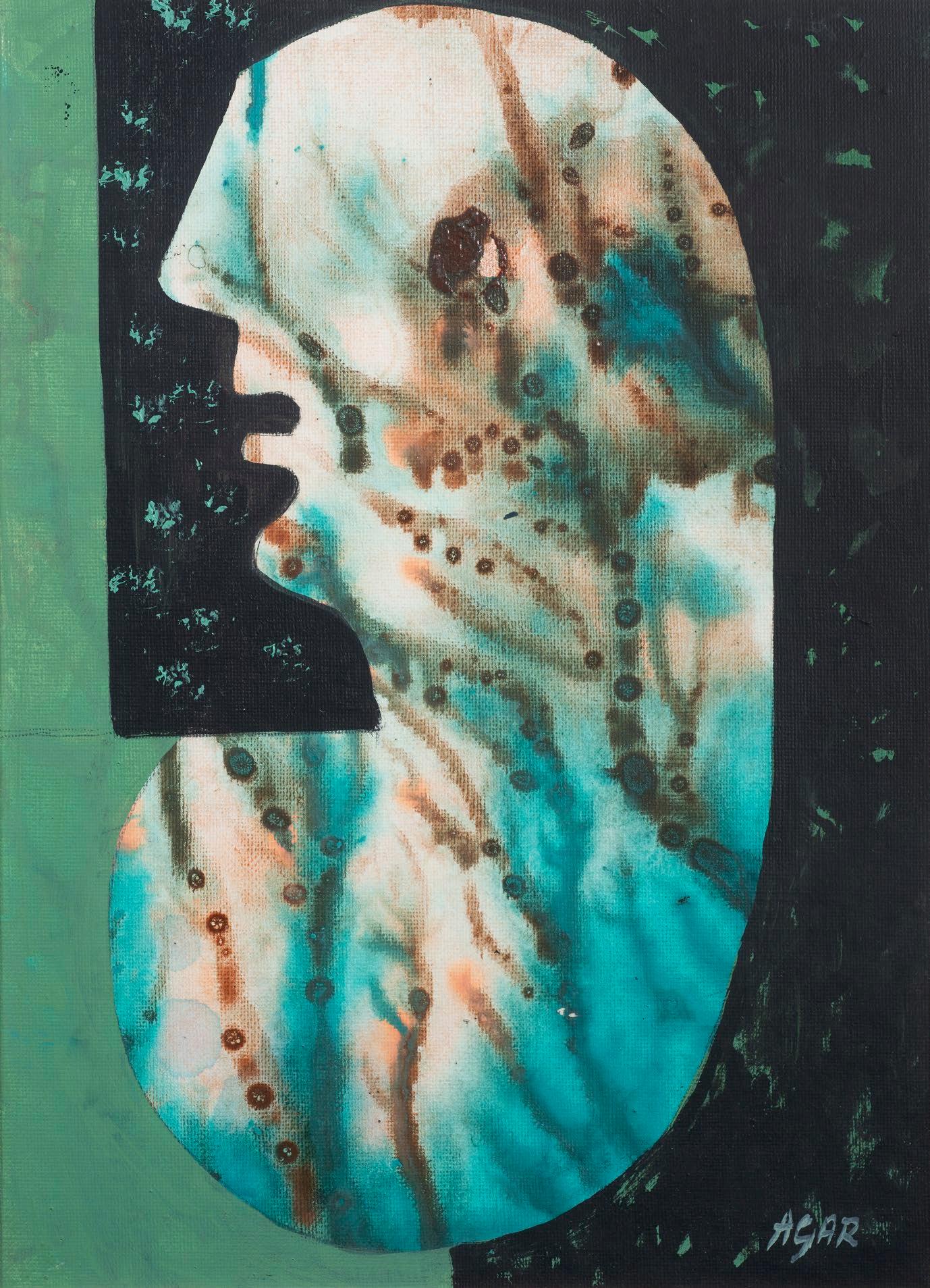

Another pupil of Underwood’s was Gertrude Hermes, who first showed her work at the Redfern in 1932. She retained a close relationship with the gallery, which staged a large retrospective thirty years later, and went on to become one of the 20th century’s finest wood engravers. At the centenary exhibition, The Yoke (1953), an intricate woodcut of an eggshaped disc filled with an abstracted figure, will appear alongside an artwork comprising collage and ink by yet another of Underwood’s protégés: Eileen Agar’s Piece with Strings (1941) is a patchwork delight in yellow, green, blue and rose.

One of the few female artists to participate in the 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition in London, Agar had a solo show at the Redfern in spring 1942. It was her first with the gallery, and her only outing during the war. She showed twenty-four new collages, among them Piece with Strings, and the exhibition was documented by fellow surrealist Lee Miller in British Vogue. After showing elsewhere, Agar re-joined the gallery in 1999, and the following year an exhibition was staged to mark her hundredth year.

Instrumental in seeking out new talent at home and abroad was the New Zealander Rex Nan Kivell, who joined the gallery in 1925. It was Nan Kivell who invited Flight to organise the exhibition of British linocuts in 1929, which was a critical and commercial success, selling more than 100 prints, and at affordable prices, too. The asking price of two to four guineas was, Flight said, comparable to what ‘the average man would pay for a beer or cinema ticket’. Cheap to create and buy, the linocut was, he believed, a medium for the masses.

Nan Kivell took the reins in 1931, and five years later the gallery upped and moved to 20 Cork Street. During the next decade he made regular trips to Paris seeking out major paintings by leading French artists including Pierre Bonnard, Eugène Delacroix and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Also, Chaïm Soutine, whose first London outing was with the Leicester Galleries in 1937, soon followed by a show at the Redfern in 1938. By now the gallery was committed to selling the work of established international names alongside modern British artists, and staged regular group shows that brought together French and English paintings.

Among the starriest of the French lot to pass through the doors was Henri Matisse’s The Red Studio (1911), consigned to the Redfern by David Tennant in 1943. An audaciously abstract portrayal of the artist’s studio in the Parisian suburb Issy-les-Moulineaux, the canvas shows a flattened space scattered with floating paintings, sculptures

and furniture, the whole lot slathered in Venetian red – a revolutionary act at a time when monochrome was yet to become a thing. Upon seeing it for the first time, the British artist Patrick Heron found it to be a ‘life-changing experience … the single most influential painting in my entire career’. Over the next couple of years, Heron was drawn back to the Redfern again and again, ‘simply to absorb, in every detail, the revelation of this great masterpiece’, and in response he made The Piano (1943), an equally colourful oil on canvas. He went on to have the first of many solo shows at the Redfern in 1947.

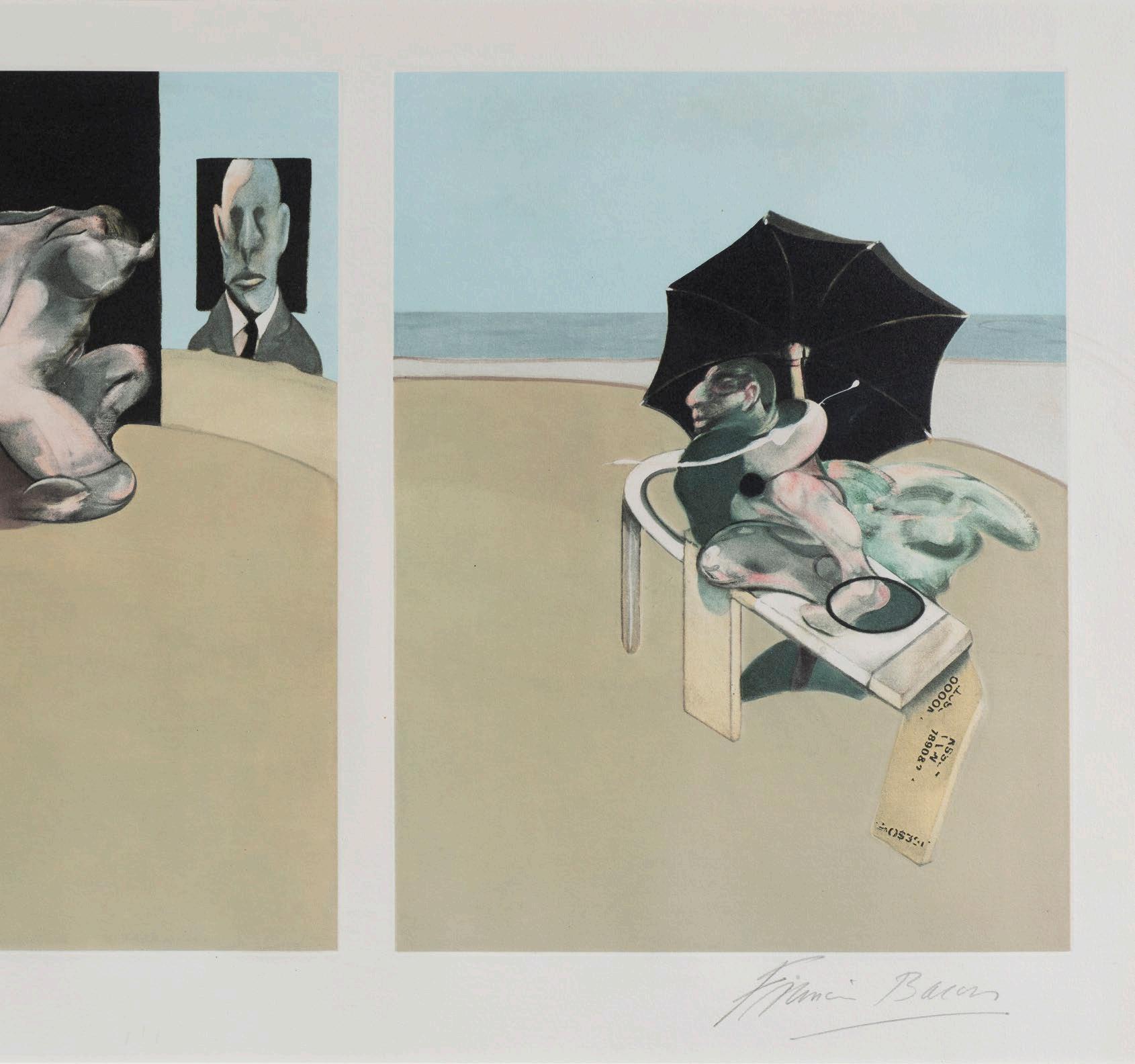

Another individual who made their mark on the gallery was the German-born, Londonbased dealer Erica Brausen, who started working at the Redfern in 1946. That same year, she discovered the dark and disturbing Painting 1946 (1946) by Francis Bacon during her first visit to the artist’s studio in Beaufort Gardens. A crucifixion of sorts, it’s a raw and meaty response to the horrors of the Second World War, with a hulking central figure shrouded by a black umbrella, and a butcher’s fill of carcasses. Bacon later described it as ‘a series of accidents mounting on top of each other’. There and then, Brausen purchased the painting, which made its public debut at the Redfern’s Summer Exhibition before being sold to the Museum of Modern Art in New York two years later.

Through Brausen, who left in 1947 to set up the Hanover Gallery, the Redfern was able to acquire further works by Bacon, who visited the gallery in the early 1950s to

admire more canvases by Soutine. Included in the centenary exhibition is Triptych 197477 (1981), painted by the artist during a difficult period of mourning. Three panels show George Dyer, Bacon’s lover of seven years, who killed himself in 1971, writhing on a deserted beach. A couple of extra black umbrellas are in bloom, and in the centre are two sinister figures. Loosely inspired by an altogether sunnier beach scene by Edgar Degas in the National Gallery, this was the last in a sombre series sparked by the artist’s bereavement.

From dark to light. The following decade saw the opening of Metavisual Tachiste Abstract: Painting in England Today, a formative exhibition that explored the influence of French tachism and American Abstract Expressionism on thirty British painters including Sandra Blow, Alan Davie and Peter Lanyon. A highlight was Gillian Ayres’ Distillation (1957), made specially for the gallery. A riot of kaleidoscopic colour against an inky blue backdrop, it vaguely resembles fireworks bursting in a night sky. An early admirer of Jackson Pollock, the English artist applied a mix of household enamel and oils, which she diluted with solvent, sometimes with brushes and rags, sometimes straight from the tube.

After Nan Kivell retired in 1965, and Tatlock Miller took over as chairman, with John Synge as director, the Redfern continued to focus on the next generation of British artists. Among them were John Carter and Patrick Procktor, both of whom debuted at

the gallery in the 1960s and continue to be represented by the Redfern. Carter soon built a reputation for his wall reliefs, shallow abstract forms that toggle between painting and sculpture. After Procktor’s third solo show in 1967, David Hockney presented him with a box of watercolours, and he declared that he would be remembered as the greatest watercolourist of his generation. On display in the centenary exhibition is Carter’s Parallelogram with bar (1972), a zingy mixed-media work with a typically physical presence, and Procktor’s Ego (1969), a dreamily washy, pastel-hued portrait of Eric Emerson, Gervase Griffiths and Ossie Clark lounging on an apple-green sofa in New York beside a vase of floppy tulips.

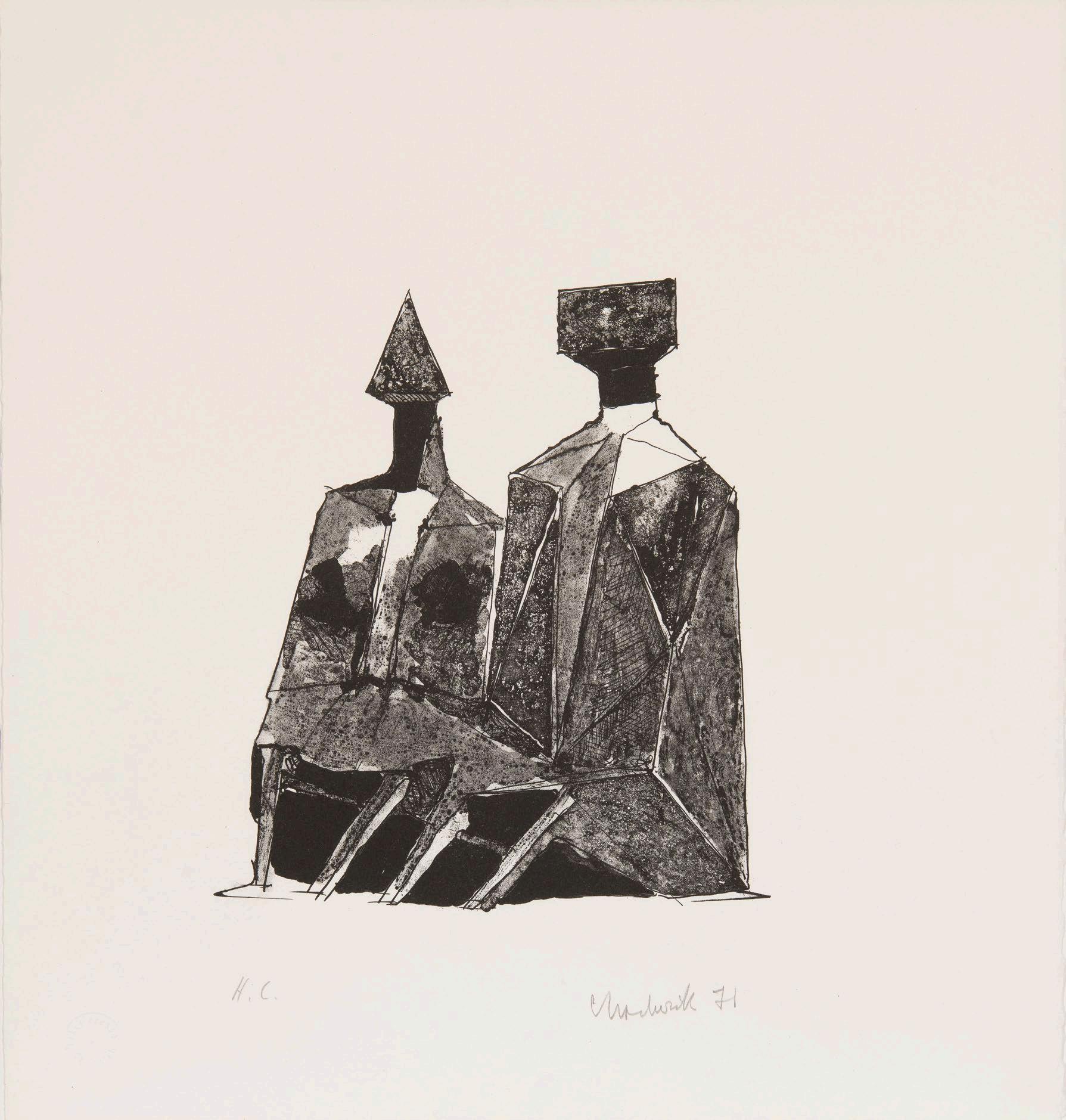

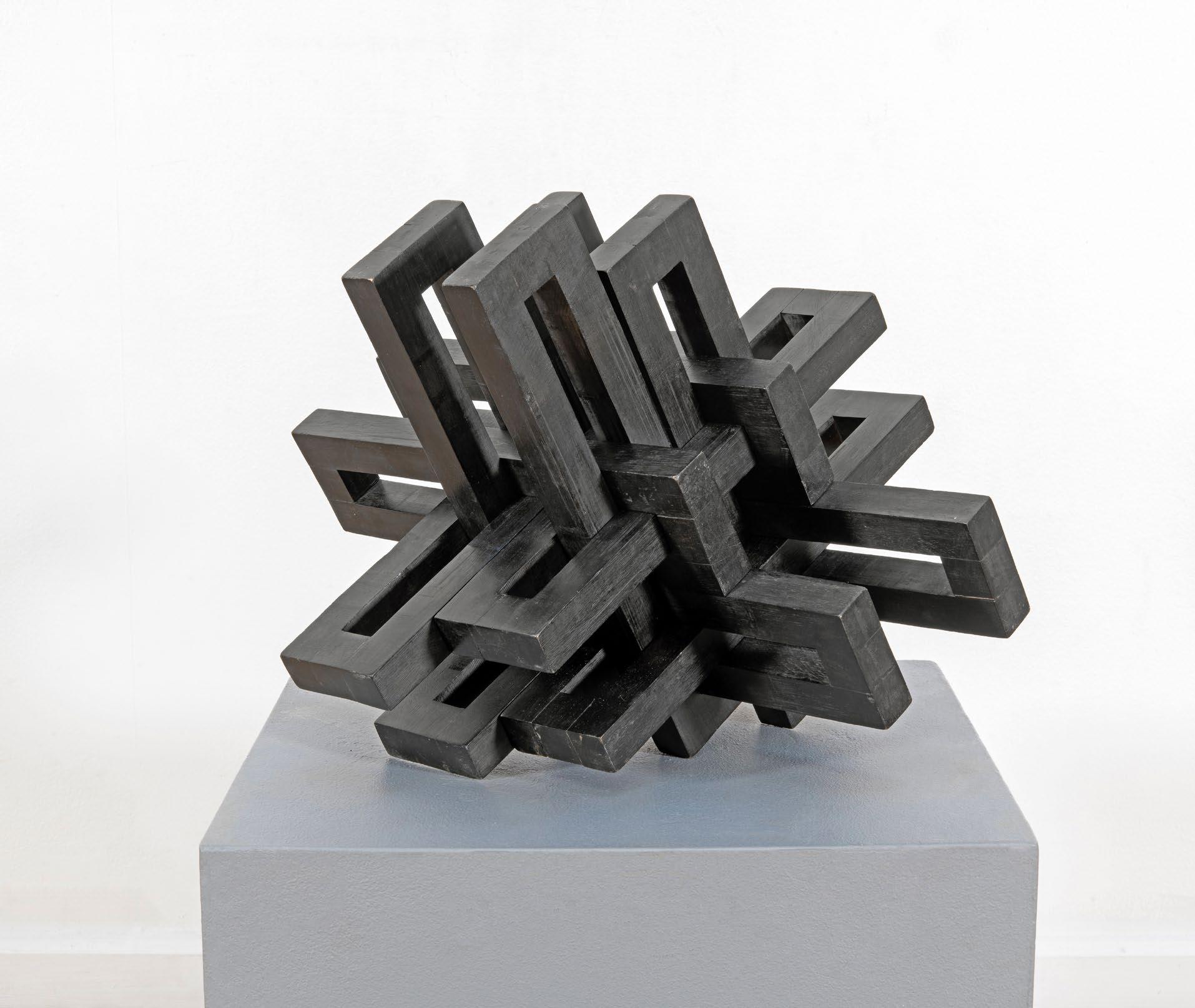

In 1973 the Redfern celebrated its fiftieth anniversary with an exhibition featuring several notable sculptures, among them a mega-mobile by Alexander Calder hovering above a graceful double oval by Henry Moore. The following year it gave another leading light his first exhibition at a commercial London gallery: a show of Antoni Tàpies’ work coincided with the great Barcelona-born artist’s retrospective at the Hayward Gallery. That same year, there was a one-off show of recent paintings and prints by the late, great Sonia Delaunay, who the previous decade had become the first living female artist to have a retrospective at the Louvre in Paris.

The gallery has a long history of welcoming talented female artists through its doors, among them Maeve Gilmore, who just last

year had her first institutional solo show. She exhibited with the Redfern in 1945, and included in the centenary exhibition are two distinctive oil paintings from that 1945 solo show: two portraits, one of Gilmore, the other of her husband, the writer and artist Mervyn Peake. Fast-forward to the nineties and the number of shows by women at the gallery skyrocketed. In 1990, Margaret Mellis, whose Blind Woman (1945) also features, unveiled a new series of flower studies sketched in crayon on unfolded envelopes. The Scottish artist, who prompted the migration of artists to St Ives in Cornwall from 1939, found inspiration in the envelopes’ different shapes, sizes, textures, hues. Examples are now in the Arts Council Collection and the British Museum.

Among those who followed Mellis during that decade were Annabel Gault and Sarah Armstrong-Jones, both recent graduates of the RA Schools. Also, Yvonne Hawker, another Scottish painter whose visceral still lifes of slaughtered animals and gutted fish were shown at the gallery in 1995. Two years later the bright and meticulous paintings and etchings of parrots’ plumage by Elizabeth Butterworth filled the space. And in 1999, Ffiona Lewis, a recent graduate of the Central School of St Martins, who set aside a career as an architect to pursue her love of painting, had her first exhibition. The gallery continues to show her softly abstracted landscapes and still lifes today.

Mellis’s husband, Francis Davison, was also on the Redfern’s books during the late 1980s

and ’90s, and since 2016 the gallery has represented both artists’ estates. Over the past couple of decades, it has collaborated with public museums and galleries to stage major retrospectives for its artists, and in 2021 the Towner Eastbourne played host to Margaret Mellis: Modernist Constructs. Small abstract compositions made under the guidance of Ben Nicholson in the 1940s featured alongside her colourful abstracts of the 1950s and ’60s, as well as the complex driftwood constructions that dominated the final twenty years of her practice and which caught the eye of the young Damien Hirst in the mid-1980s.

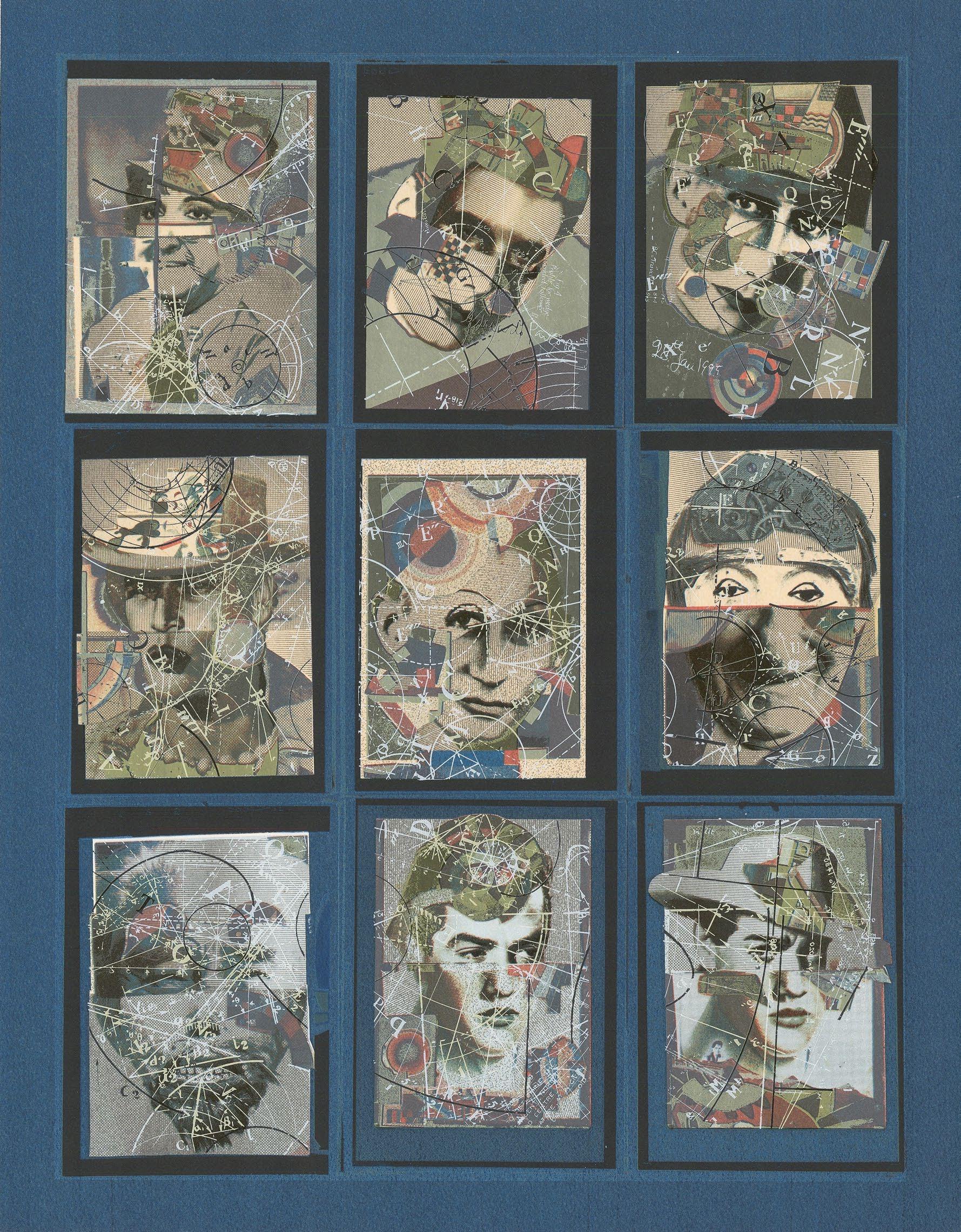

Perhaps the Redfern artist who has found the most fame of late is Agar, whose work has been included in many major exhibitions during the 2000s. In 2004, Eileen Agar: An Eye for Collage opened at Pallant House Gallery in Chichester, and the Redfern staged Eileen Agar: An Imaginative Playfulness alongside it. Most recently the Whitechapel Gallery hosted Eileen Agar: Angel of Anarchy, an exuberant display of more than a hundred rich and curious works spanning six decades, including painting, collage and whacky assemblage. This time, coinciding with the exhibition, the Redfern curated Eileen Agar: Another Look, in which five contemporary women artists were invited to make Agar-inspired work, among them Florence Hutchings and Linder.

Over the past decade, the Redfern has also taken another look at artists who have drifted from view following initial success in

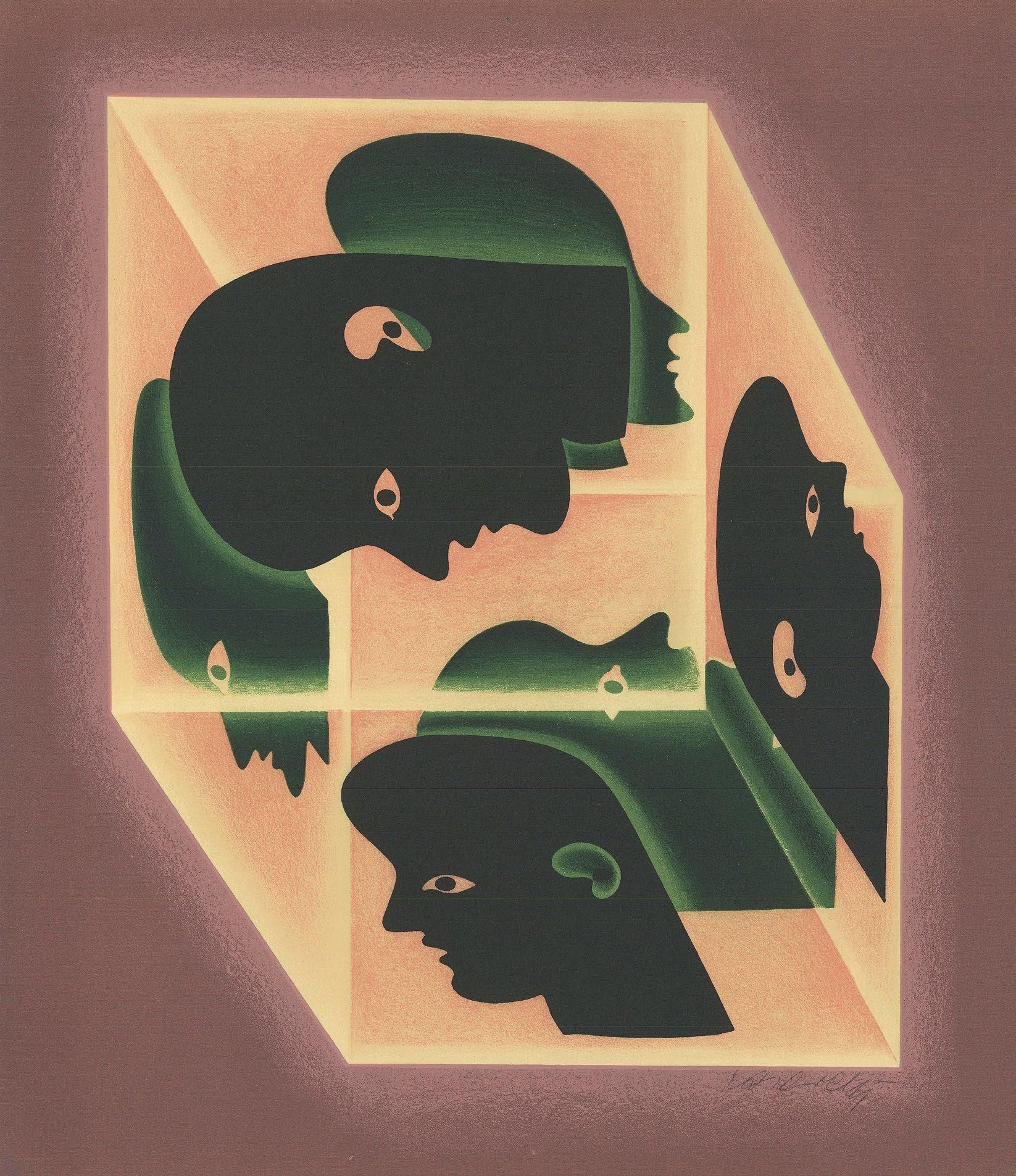

the 1960s and ’70s. One-off retrospectives have been staged for Neil Stokoe, who had only rarely exhibited his paintings prior to his Redfern show in 2015, and Brian Rice, who was thriving in the sixties before leaving London to live life as a shepherd in an isolated farmhouse in Dorset. Alongside such solo outings, the gallery continues to put on surprising and significant group shows, including Pure Romance in 2016 (which traced a romantic sensibility in paintings, photographs and works on paper from the 1920s to the present) and THEM in 2020 (a dazzling display of flamboyant work by five punky artists who came to prominence in the early 1970s).

The first of the Redfern’s two centenary exhibitions also offers viewers a chance to look again. To revisit those artists who first showed with the gallery when they were starting out, many of whom maintained a close relationship with the Redfern throughout their careers. Some had several exhibitions over the years. Others came and went. Either way, the bond remains, much like that between the horses and riders Sybil Andrews depicted leaping ever so nimbly over that birch fence.

Chloë Ashby June 2023

Paintings & Drawings

Robert Adams (1917-1984)

Study for Sculpture 1950

Ink and collage on paper

55 x 72 cm

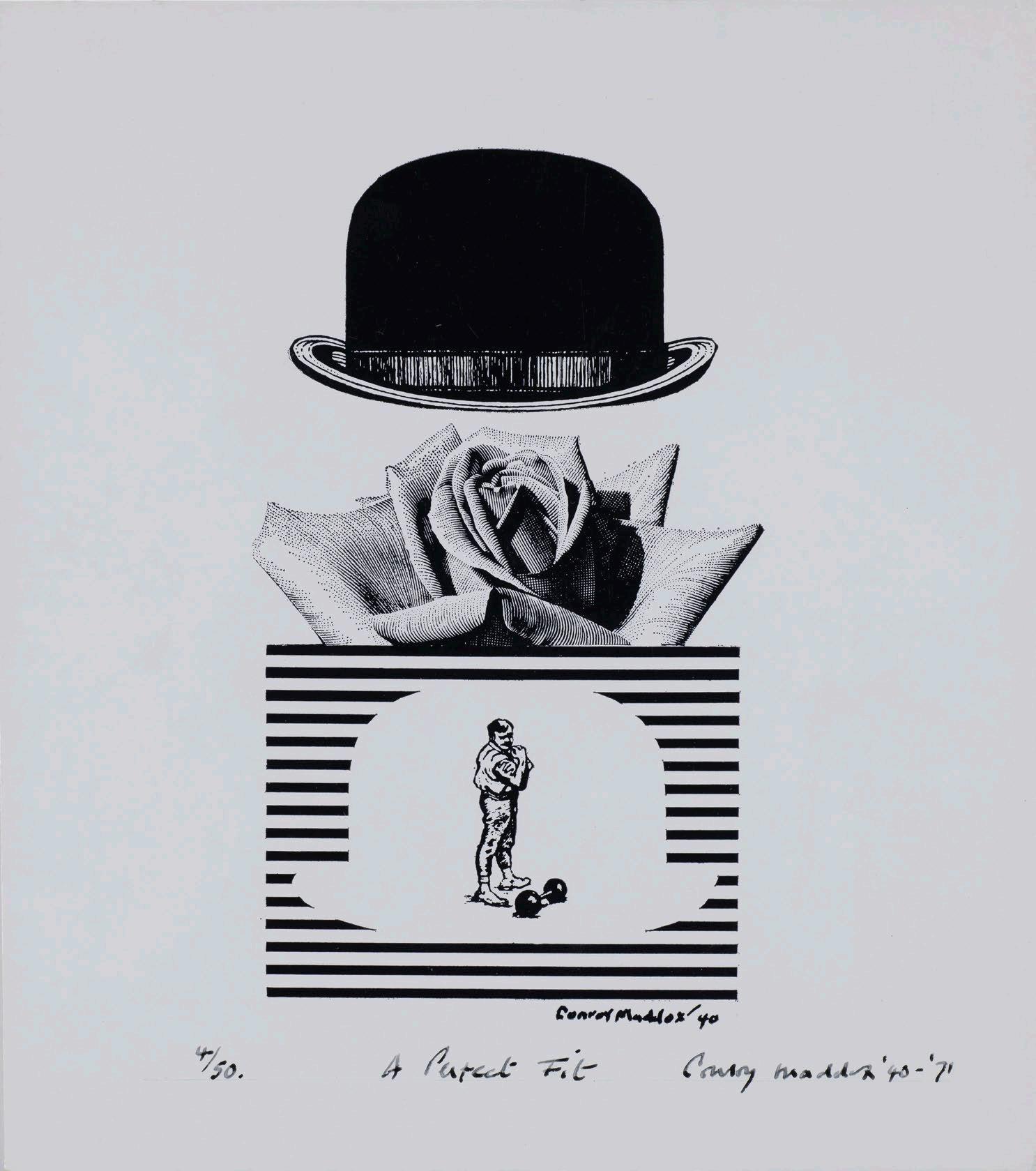

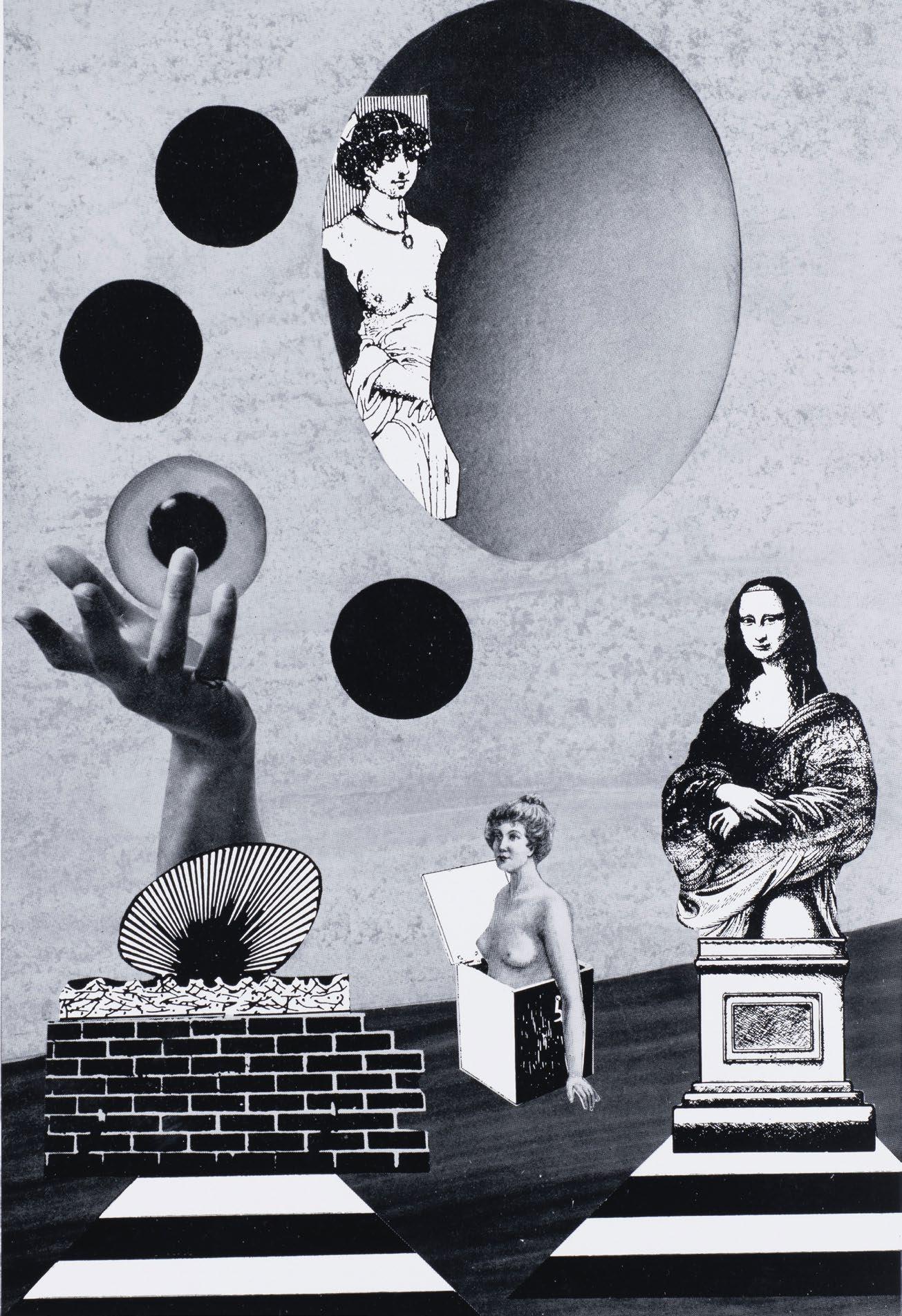

Eileen Agar RA (1899-1991)

Untitled 1955

Enamel on paper

45 x 64.5 cm

Eileen Agar RA (1899-1991)

Beetles and Hand 1966

Ink and collage on card

21 x 12 cm

Eileen Agar RA (1899-1991)

Dancers c.1948

Wax crayon frottage on paper

22.1 x 28.5 cm

Eileen Agar RA (1899-1991)

Aaron’s Rod 1976

Watercolour on paper

30.5 x 40.6 cm

Eileen Agar RA (1899-1991)

Birdform 1984

Felt-tip pen on paper

17.6 x 13.8 cm

Eileen Agar RA (1899-1991)

Rocks at Brittany 1985

Acrylic on canvas

61 x 61 cm

Untitled (Blue, Black, Red) 1956

Oil on paper

74.5 x 55 cm

Parallelogram with Bar 1972

Mixed media and collage on board

51 x 73 cm

John Coplans (1920-2003)

Painting I 1956

Oil on board

76 x 122 cm

D-230 1971

Collage

110 x 107 cm

Metavisual Tachiste Abstract - Painting in England Today 1957

Mixed media on paper

73.5 x 49.2 cm

Cat, Bird and Tree Stump 1949

Ink on grey Ingres paper

31.7 x 48.2 cm

Untitled c.1953

Watercolour, pen and black chalk

38 x 41.2 cm

Mary Fedden RA (1915-2012)

Garden 1967

Gouache, chalk and collage on paper

38.5 x 54 cm

Paul Feiler (1918-2013)

Evening Harbour, Low Tide 1953

Oil on board

50 x 92 cm

Gandria, Black and Lemon 1956

Oil on canvas

61 x 40.5 cm

Coastal Walk 1959

Oil on board

40.6 x 61 cm

Gwithian, Black, Blue & Umber 1959-61

Oil on board

83.5 x 119.5 cm

Revolving Forms 1966

Oil on canvas

92 x 132 cm

Zenicon XLV 2008

Oil, silver leaf, gold leaf and gessoed board on canvas laid on wood

66 x 66 cm

Sir Terry Frost RA (1915-2003)

Mars Red and Yellow Green 1958

Oil on board

76 x 122 cm

Variations 1984

Collage, acrylic, crayon and ink on paper

29.5 x 20.5 cm

Sir Terry Frost RA (1915-2003)

Untitled (Variations) c.1970

Collage, ink and crayon over screenprint

21.5 x 23 cm

Hand-worked proof of the print Variations (Black on White), 1973 (Kemp 69)

William Gear RA (1915-1997)

Sussex Landscape 1959

Oil on canvas

204 x 127 cm

William Gear RA (1915-1997)

Landscape, Blue Element 1959

Oil on canvas

128 x 80 cm

Maeve Gilmore (1917-1983)

Mervyn Peake c.1938

Oil on canvas

91.6 x 71 cm

Maeve Gilmore (1917-1983)

Self-Portrait c.1939

Oil on canvas

91.2 x 71 cm

Donald Hamilton Fraser (1929-2009)

Composition 1951

Oil on board

32.5 x 66 cm

Adrian Heath (1920-1992)

Rowner 1977

Oil on canvas

152 x 147.5 cm

Roger Hilton CBE (1911-1975)

March 1960

Oil on canvas

63.5 x 76.2 cm

Ivon Hitchens (1893-1979)

Dark Pool with Boats 1960

Oil on canvas

45 x 115 cm

John Hoyland RA (1934-2011)

Ladders of the Sky 2001

Acrylic on canvas

61 x 76 cm

Derek Jarman (1942-1994)

Tray from ‘Savage Messiah’ c.1972

Oil on board

50.5 x 76 cm

The Riddle 1958

Oil and enamel on canvas

96.5 x 46.4 cm

Phenomena Orbital Station 1982

Acrylic on canvas

152.4 x 127 cm

Phenomena Shield to See by 1987-96

Acrylic on canvas

147.1 x 103.9 cm

Oil on board

12.5 x 45 cm

Rock

Oil on canvas laid on board

12 x 39 cm

Oil on canvas

76.2

Margaret Mellis (1914-2009)

Blind Woman 1954

Oil on board

91 x 70 cm

Margaret Mellis (1914-2009)

Little Boy: Blue on Red 1970

Relief

17.8 x 17.8 cm

Margaret Mellis (1914-2009)

Relief Pink and Blue 1971

Relief

17.8 x 17.8 cm

Nisida Island and the Gulf of Naples 1956

Ink on paper

45 x 64 cm

Sir Cedric Morris (1889-1982)

Still Life of Plants and Garden Produce in an Old Kitchen 1958 Oil on canvas

98.5 x 122.5 cm

David Oxtoby (b.1938)

Elt on Elton 1980

Mixed media on card

86.5 x 66.3 cm

Victor Pasmore (1908-1998)

Window at Dieppe c.1932

Oil on canvas

47.5 x 59.5 cm

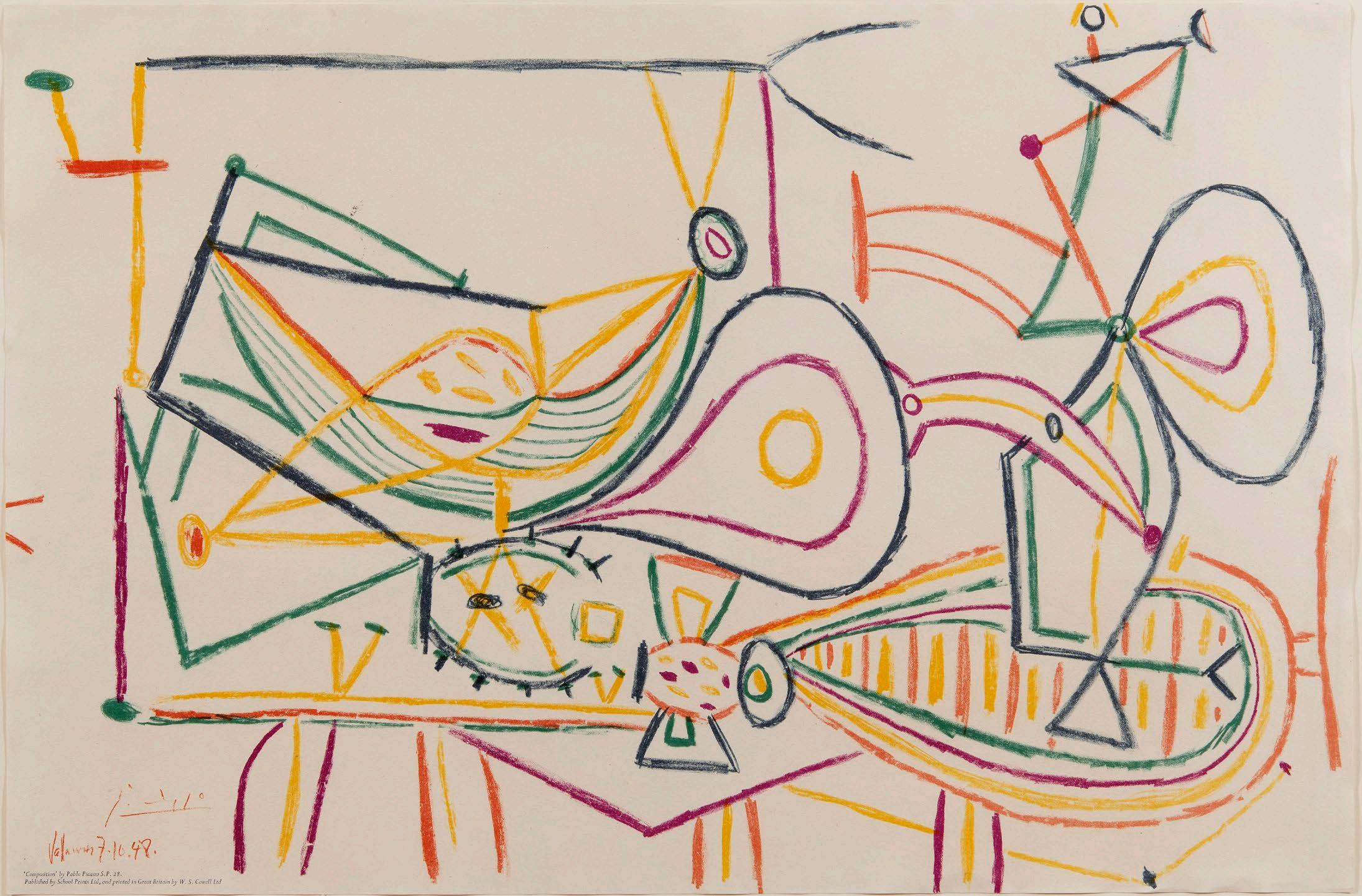

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973)

Femme Nue et Deux Têtes 1969

Pen and brush and ink on paper

32.5 x 41 cm

Drowning 1965

Oil on canvas

190.5 x 147.5 cm

Portrait of Verner de Biasi in Floating Chair

1967

Watercolour on paper

49.5 x 34.3 cm

Sunrise II 1957

Oil on board

110.5 x 197 cm

Michael Rothenstein (1908-1993)

The Hen Coop 1943

Watercolour and pen

36.2 x 49 cm

Michael Rothenstein (1908-1993)

Catherine Wheels 1954

Oil on canvas

63 x 76 cm

63 x 47 cm

Norman Stevens RA (1937-1988)

Louvered Shutter (Morning) 1972

Mixed media on paper

38.5 x 56.5 cm

Monkey

Oil on canvas

40.2 x 30.6 cm

Study for Flowers and Wasps 1964

Gouache, ink and pencil on paper

51 x 31 cm

David Tindle RA (b.1932)

Still Life 1957

Oil on canvas

43.2 x 58 cm

David Tindle RA (b.1932)

Shaded Garden 1989

Tempera on paper laid on board

50 x 77 cm

Arnold van Praag (1926-2020)

At the Easel 1965

Oil and sand on board

87 x 64 cm

Yellow Seated Figure 1949

Gouache on paper

50.5 x 38 cm

Group of Figures 1965

Gouache on paper

51.2 x 42.3 cm

John Wells (1907-2000)

Untitled 1967

Mixed media on paper

25.5 x 35 cm

Paul Wunderlich (1927-2010)

Crying Woman 1959

Oil on board

120 x 90 cm