PETER SEDGLEY

A retrospective survey conceived in dialogue with Dr Omar Kholeif

In memory of Ingeborg Lommatzsch

Omar Kholeif

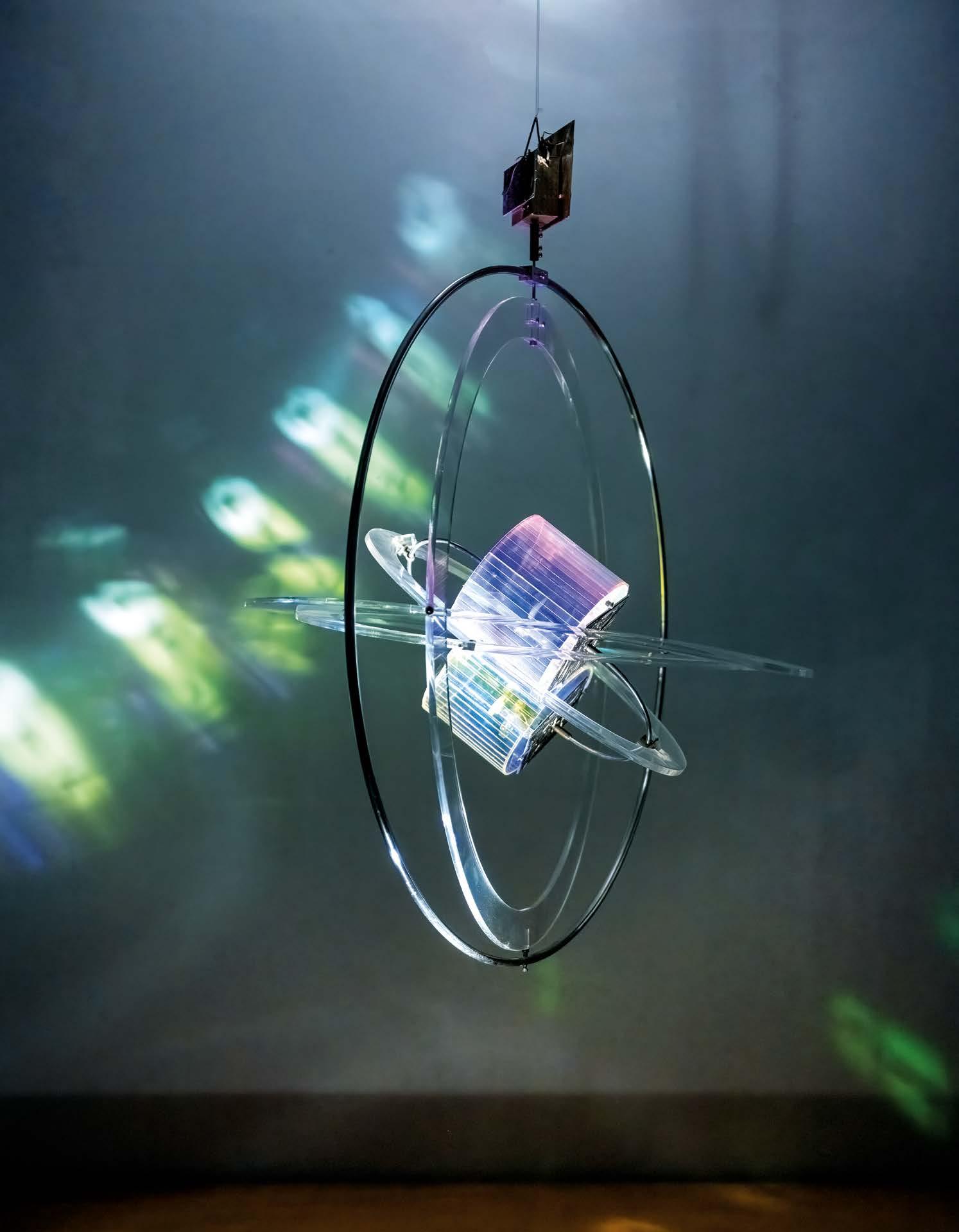

From within the choreographed theatre of darkness— the architectural motifs and reliefs of the museum, a thicket of dust gently unspools itself from the stillness and begins to float mid-air. Above beams of colour, it drifts and meanders, gliding the guide towards the direction of a centre point. A gentle rip in the tide, the particles form cellular-looking blankets, which forge the site of encounter between me and a slow-moving orb. An orbit tilting at 45 degrees, at a pace all its own. What in the ‘light’ may have seemed but a modestly sized kinetic sculpture, a scalable Calder mobile perhaps, has evolved into something rather peculiar. The work, one of Peter Sedgley’s signature 1980s kinetic sculptures ushers one into its shadows, enfolding you into silhouettes that disguise brightness, an experiment in composition and colour.

Meticulously laid tubes of blue, green and magenta transmit against wall and floor, punctured by a warm off-white. It is not quite the sun that we are looking at. Everything here is as artificial as the synthetic and fluorescent paints in Sedgley’s 1960s paintings on paper, board, panel, and canvas. But, in this silence, it becomes entirely human. Each reflection or is it a refraction becomes akin to an echo that has been caught and held within the Lascaux caves. Kept here for keepsake—for humanity to examine and bear witness to. The human-made motor that governs the motion of light in Sedgley’s sculpture begins to resemble a body. It evokes the sensibility of a ballet dancer who is gradually warming up before the dance. You the spectator are

invited, and this is how Sedgley would like it. For you to bring forth your own impulses of movement and feeling, to complete the waking journey of his, and in the end, our artwork.

Peter Sedgley has never been shy of his affections for the French painter, George Braque. A 1996 publication is annotated on either side of the inner lead with a quote by Braque that reminds us that art finds its meaning in ‘that which cannot be explained’. Some, including Sedgley, have correlated the humanistic impulse of emotion in art with the concept of the enigma, or the enigmatic self. The mysterious concept allows for one to submit to art’s expressive will. To circumscribe, to stitch a path, a way of being in the world where the constant need for critically disentangling the art object is put aside for a moment’s relief.

For Sedgley, who has devoted his life to venturing into arenas that have required sheer will and self-belief— sites where the end result may have at first only seemed probable, not necessarily possible, the concept of the enigma assumes an almost romantic station within a constellation of metaphors. From today’s vantage point, where technological cabling of the ‘internet’ under land and sea have created ripples of information overload, I would argue that although Sedgley the artist might be an enigma himself, in the realm of art he is an open book. Indeed, his art, has for more than five decades

plunged spectators into the inner-most depths of the soul. It is the inverse of a Freudian uncanny, of the spectral. Instead, Sedgley’s is an art that exists as a consequence of his open invitation to the human to complete the artwork’s journey.

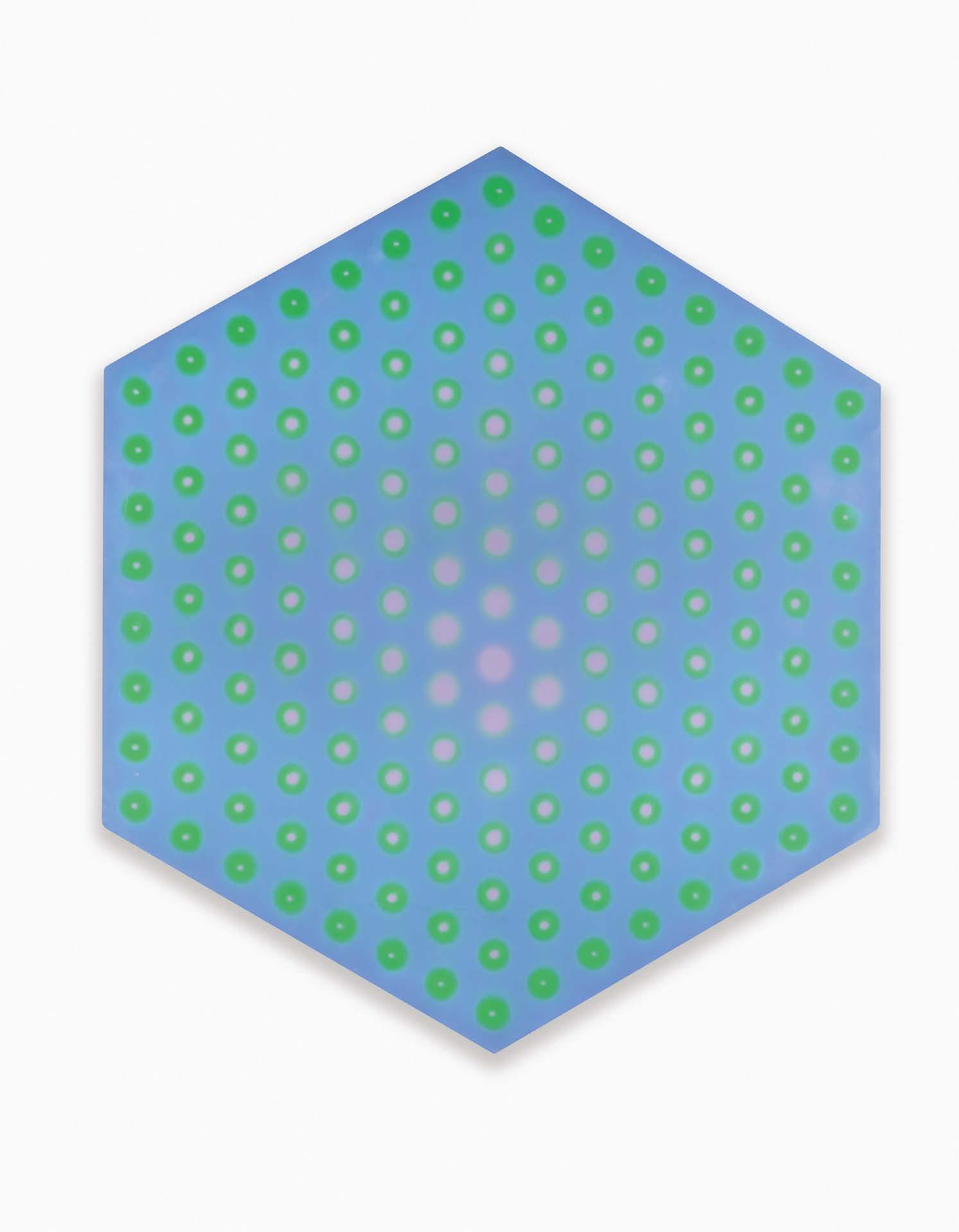

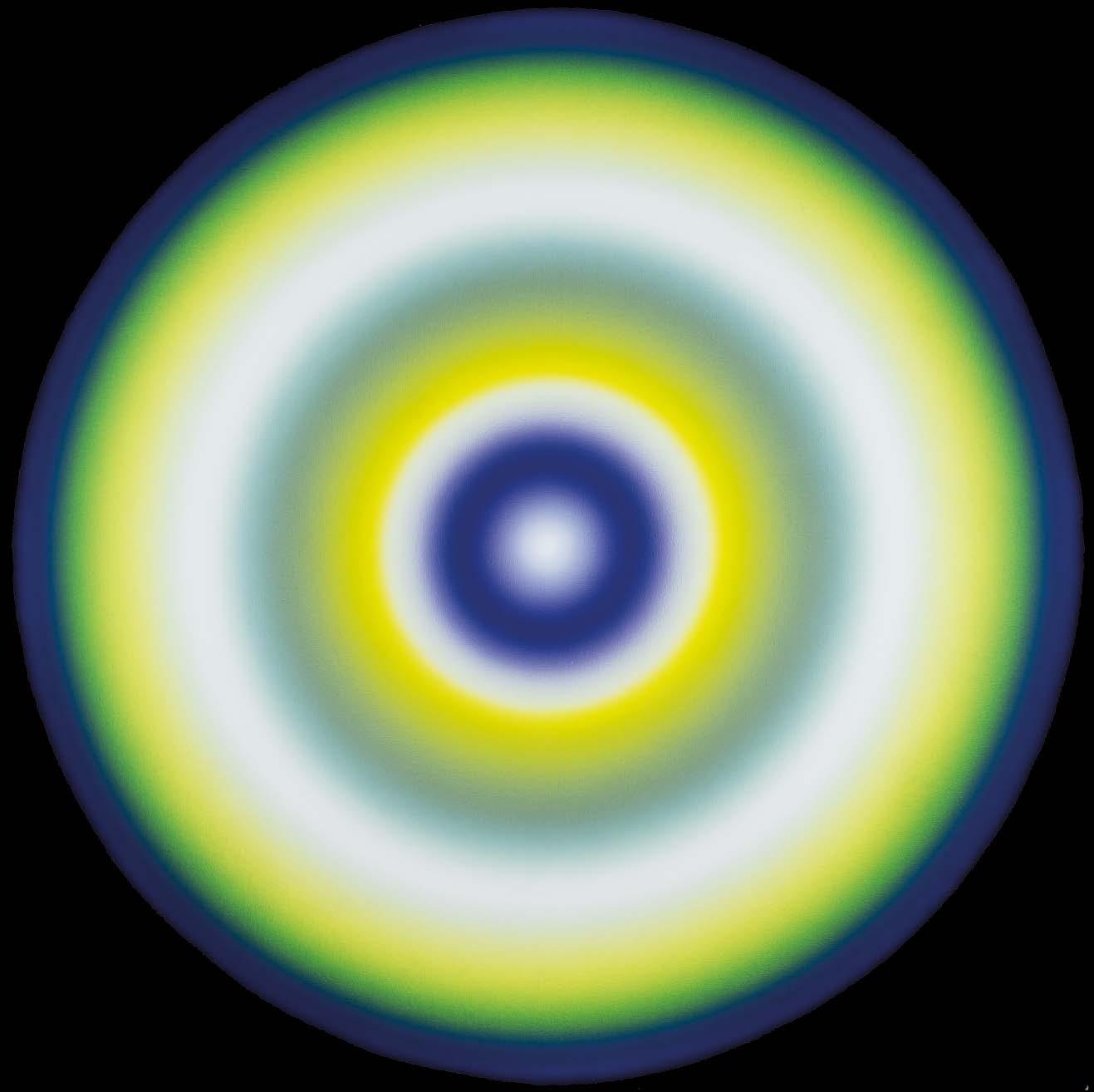

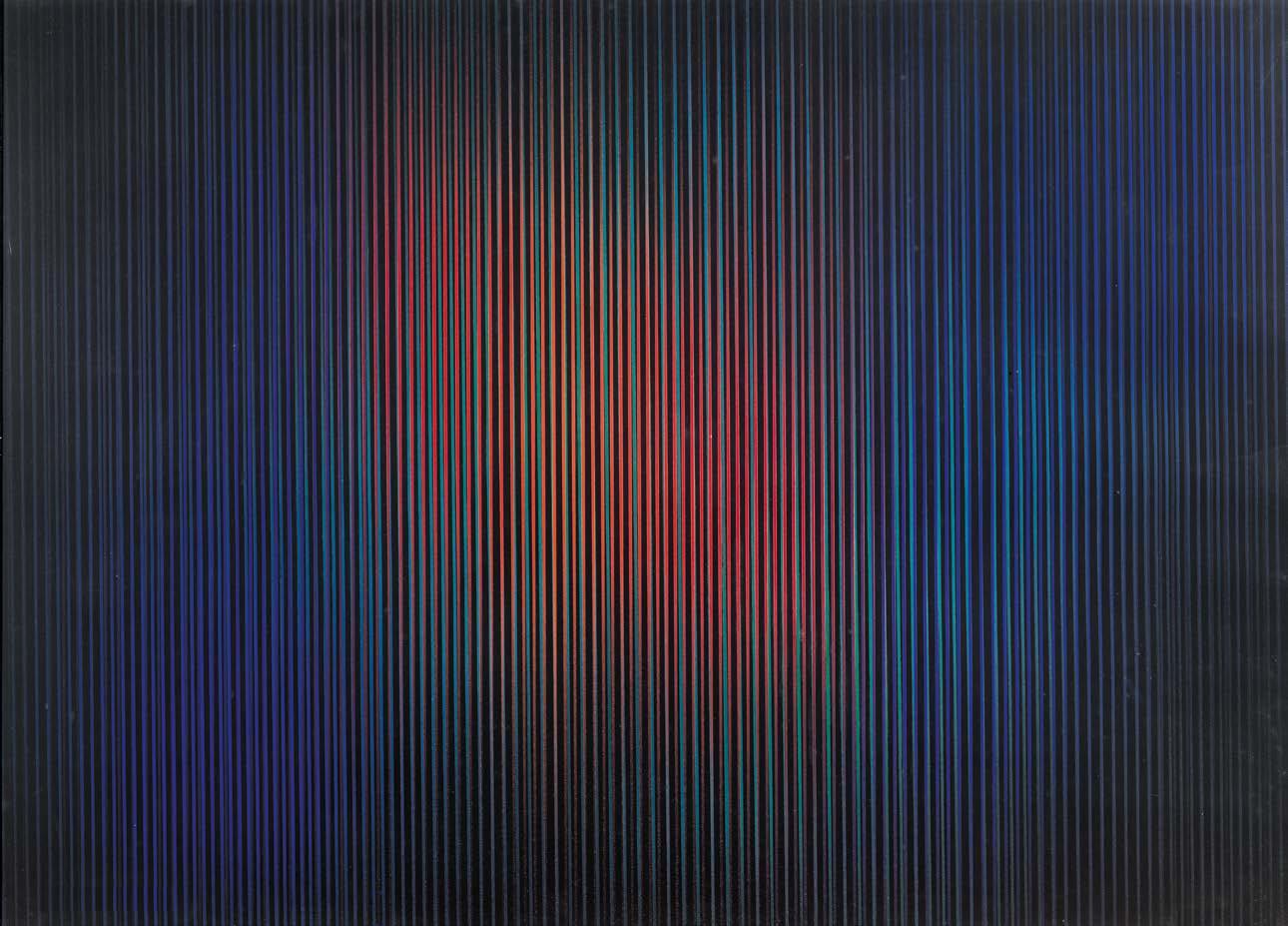

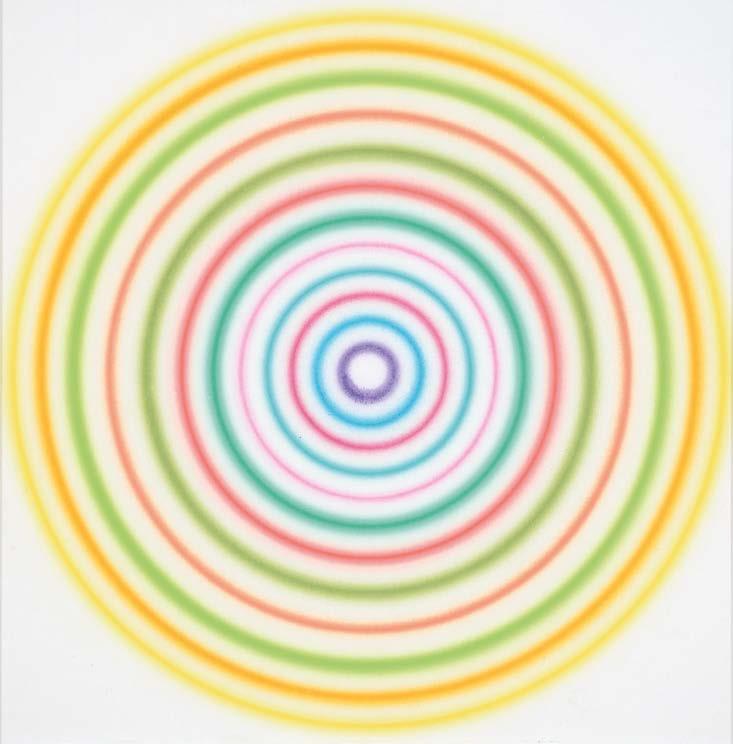

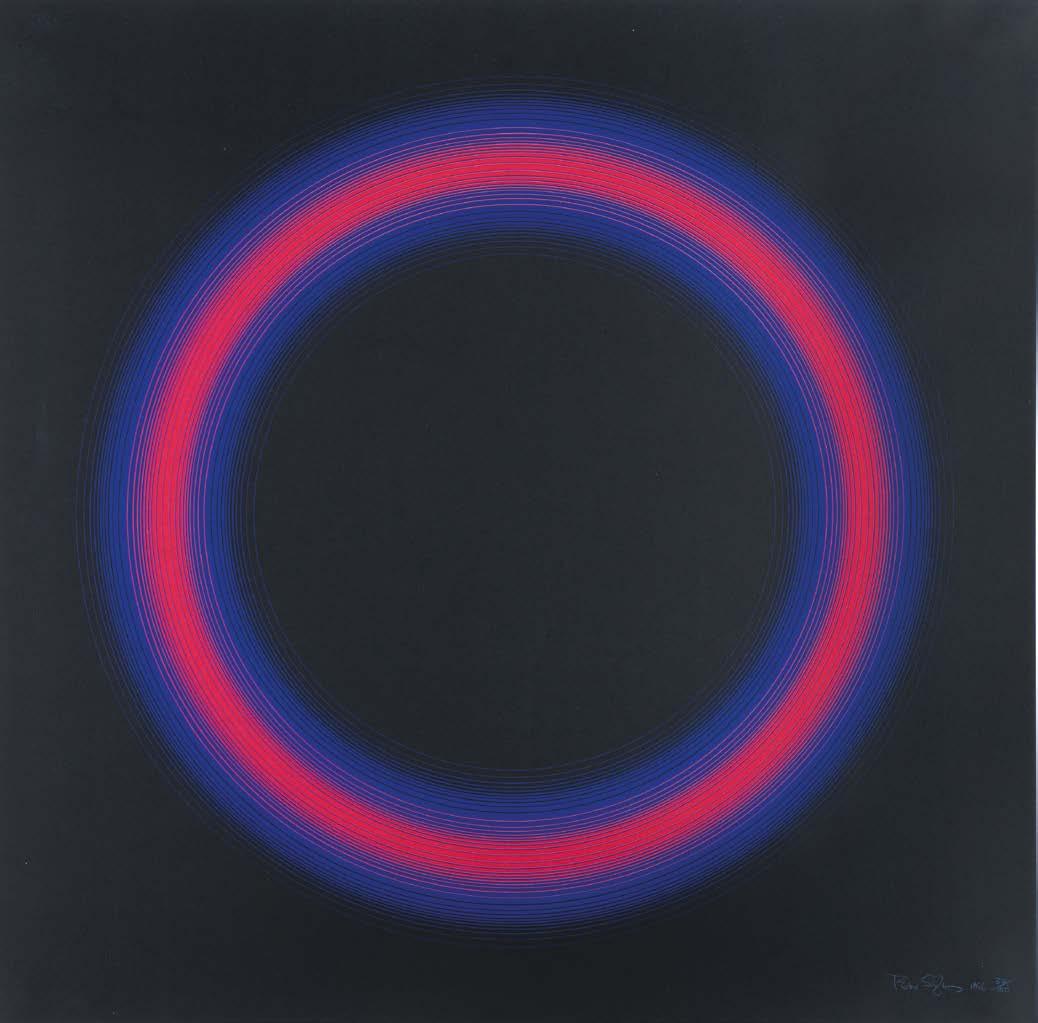

Let us examine one of the most visually iconographic works in the exhibition, ‘Peter Sedgley: Five Decades’, Red Nebula, 1973. Red Nebula is as representative as any work of Sedgley’s lauded experiments with light and painting. The work itself, although constituted of a programmed light that is cast upon a florescent painted ‘target’ of meticulously painted concentric lines forming a circular centrifugal form, is nonetheless left to the spectator’s eye to determine the affective possibilities. Constantly mutable, no two bodies will necessarily be able to absorb, construct and form the same ontological view of the scene before them. The title’s allusion to the ‘nebula’, i.e., that which exists between the stars and us, the cloud of dust visible in certain nocturnal skies, speaks to humanity’s wish to connect with each other, and with the prospective possibilities of time and memory itself. As the eyes shore to the night sky seeking to decode history, we ask if one is connecting with the past or with the future. What realm exists beyond that of the present tense?

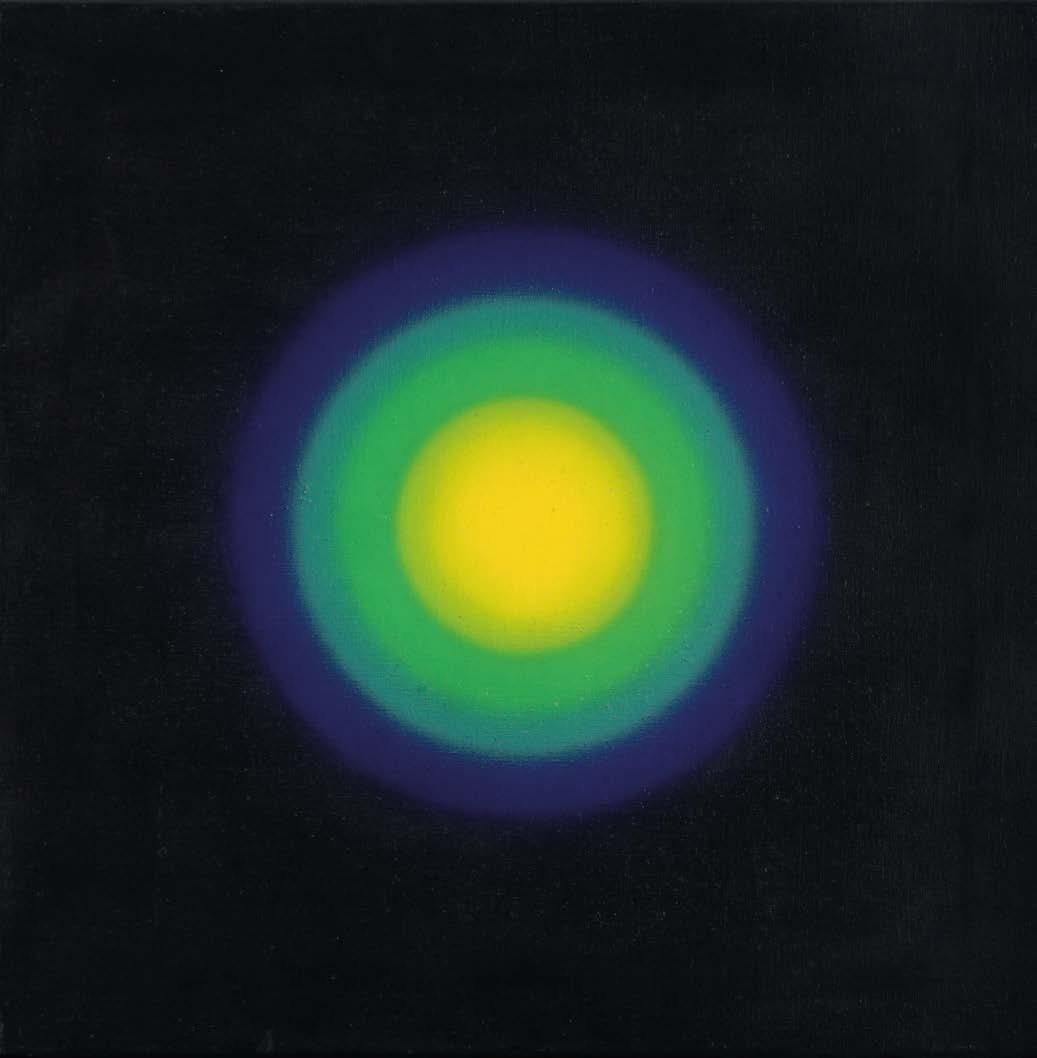

Energy, 1980, an acrylic painting on linen, is bulbous and alive, like an amoeba being studied under a telescopic lens. Except it is thrust into one’s cornea – one is made to feel as if seeping through a funnel of white light. The yellow and green and blue contours are synonymous with constructivist notions of productivity. Looked at here, it is as if the painting were about to come up off the wall and serve as a flotation device, or any other number of conjured imaginings. To render art that cleaves itself to the human imagination is the gift that Peter Sedgley has given to art’s living history.

The genesis of this thinking for the art critic has been debated widely and is often attributed to Susan Sontag’s summoning within her collection of essays, ‘Against Interpretation’. Here she requests, or rather demands that we submit to an ‘erotics’ of and for art. Sedgley’s art can be conceived as a riposte to Sontag and every critic’s bidding for an erotic of art—to give in to the

hermeneutics, not exclusive of considering one’s formal tradition. The experience of surrendering one’s faculties to the sensuous pleasure gleaned from looking at an aesthetic object—desiring it, without wishing to extricate it from its presence is a delight that all artists aspire to in a certain way. Sedgley invites you to allow ‘it’ [the art] to do its ‘job’. One can absorb its materiality— pigment, ink, paper, the artist’s movement and gesture— imbibing the vessels of raw feeling that have been put forth.1

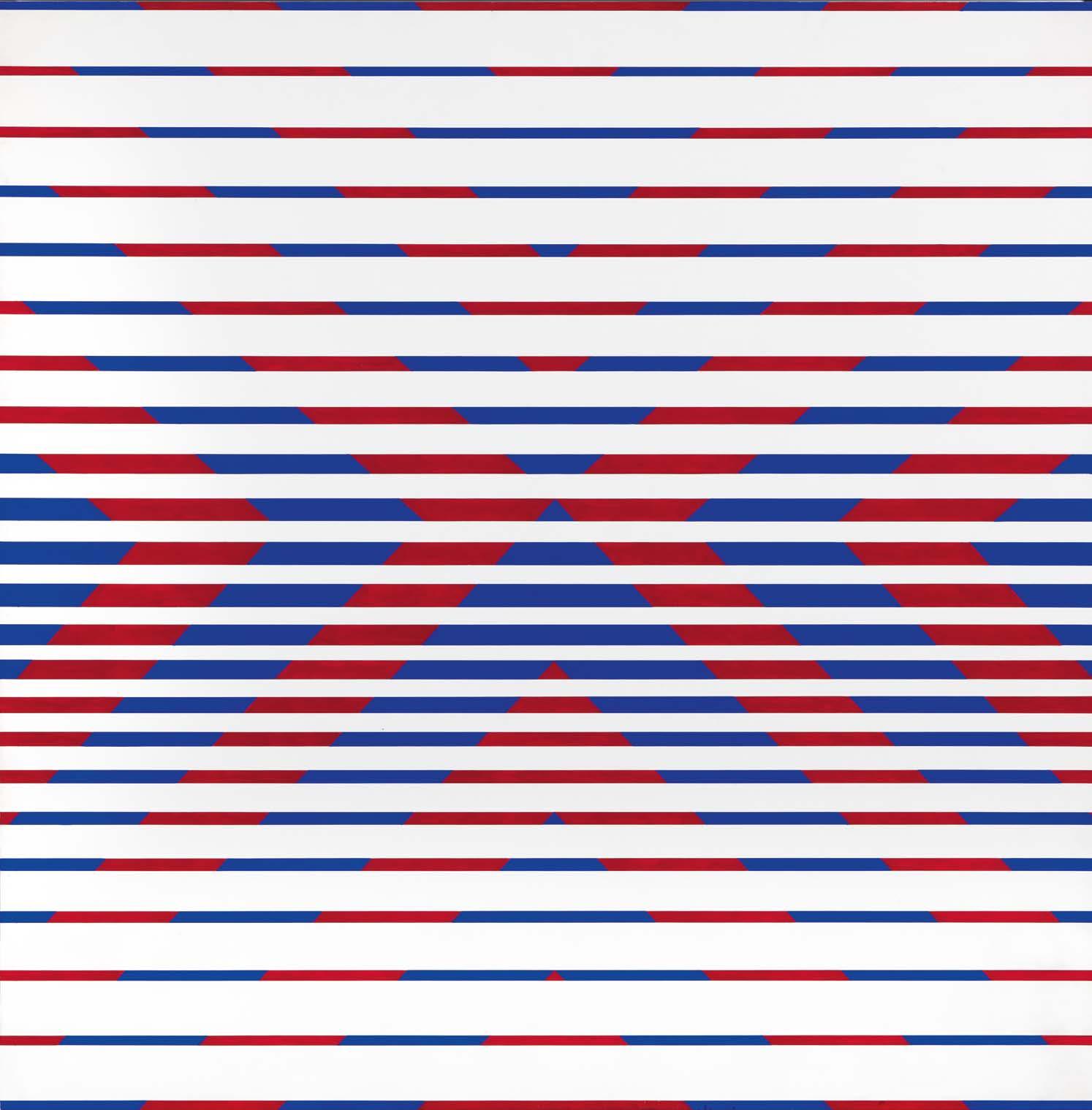

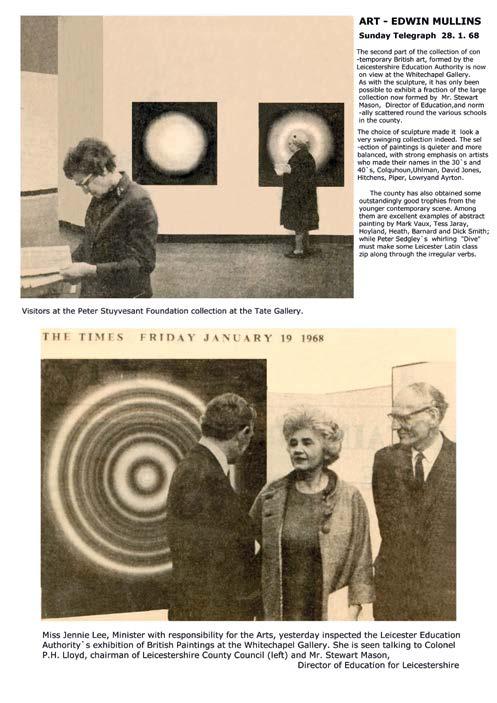

For Sedgley, who was born in 1930, the act of surrender began gradually in 1959 when he relinquished his work in architecture and the built environment to pursue an ‘exercise of the imagination’—engaging in experiments that were deemed to resemble the German Dada and Surrealist artist, Max Ernst.2 By 1965, after presenting Red and Blue Modulation, 1964 at the Museum of Modern (MoMA)’s storied Op Art exhibit, The Responsive Eye in 1965, Sedgley deemed his art practice ‘serious’ in that it was his full time occupation. Prior to that he had had his own business. His early exhibitions were critical and commercial successes, with artworks acquired by the nation of Great Britain’s treasured collections from Tate to the Arts Council.

Today, these successes, which have been consistent to varying degrees, throughout the artist’s life, feel like lesser details when attempting to assemble Sedgley’s portrait in space and time. Back then: Modern and contemporary art was not as widely competitive nor vernacular. When art roused a person be they a collector or curator, it elicited a response, an action, a money drop. Competition, price, context, were incomparable. The art of Peter Sedgley, conversely, has not changed in its magnificence, if anything, it has matured with the thickness of time itself, becoming more abundant.

Paintings, prints, and installations presented in ‘Peter Sedgley: Five Decades’ are ebullient, voluptuous, psychologically rich and contemporaneous. With societal conflict and stratification weighing heavily upon our lives, the need to make sense of its machinations and its burden, we as a society find ourselves in a state of perpetual burnout. We need art as salvation. Sedgley constructs topographies that ultimately become sites of affect. Sedgley’s art is textured, lush, unashamedly so, filled with desire. Brought together here in this exhibition

they propose a world, they put forth their own erotics— an erotics of salvage. A space of dreaming, one where we can put aside the lumpen pain of an imagination colonized by large media conglomerates and tech companies.

Sedgley’s structured tessellating objects, their watchful geometric balance, emitting a precisely located field of light lead us to a map. Here, the conscious interplay of colour across multiple surfaces—both inside and outside is revealed. This choreography is so boundless, yet still restrained, unlike the haphazard chaos of the entangled webs that unfold in the virtual sphere. Whether bathed in light or left unburnished from his interventions, Sedgley’s pictures dance, and that is what we wish to do, is it not, to be invited to dance, all of us, on the same playing field, each to our own abilities?

Why then, is Peter Sedgley, still

seen as such as an enigma by so many, or rather why

is his art,

a genuinely human enterprise,

circumscribed to the realm of the unknowable?

It is the middle of the night in London, late autumn. It is balmy, unusually so, but the sky is thicker and darker than before. I open all the windows. After weeks of digging, I uncover a brown package from my archive with all of Peter Sedgley’s past exhibition catalogues. They are mostly modest in size, and softcover, and fit in my lap. From the way that they have been wrapped, I feel like I’m about to sit down and eat a bag of fish and chips.

This grouping of battered and bruised, dog-eared and marked books were salved from random places over several years between 2010 and 2014. I had to beg, borrow, and barter when I was conducting research for the exhibition Electronic Superhighway (2016-2016) an exhibition that was largely inspired by Sedgley, and when it opened at the Whitechapel Gallery in 2016 before its tour, two of his light-filled cellular ‘target’ paintings closed out the show. I completed the project

while I was curator at Whitechapel Gallery, London. I had begun work on the concept of bringing together a history of all the variant subfields of ‘networked’ art and culture when I was still curator at the Foundation for Art and Creative Technology (FACT) in Liverpool.

Subsequently, I jumped ship to SPACE in Hackney Central thanks to the inspiring figure that is Anna Harding and then to Aldgate East to fulfil a dream at Whitechapel—to amplify the voices of artists on a global stage. At SPACE, I worked alongside the CEO, artist and social activist, Anna Harding whom I had known as a founder director of the MFA programme in Curating at Goldsmiths, University of London. I had learnt about her through a colleague, Heather Corcoran at FACT, who was my predecessor at SPACE, which many do not realise is the UK’s largest artist support agency, offering advocacy and support as well as subsidised studio provision across over 20 buildings in London and Essex. It is the oldest and longest running studio provider in London.

It was co-founded by Peter Sedgley and Bridget Riley, with Peter Townsend in 1968. I recall Anna Harding being very expressive whenever Peter’s name came up in discussion. At the time, she was negotiating the donation of the SPACE archive, and she had prepared a book on the organisation’s history. She narrated tales of Sedgley showing up to a meeting on a motorbike when he was in his late 60s or 70s. I’ve never managed to find a picture to such effect, but the myth was one that the staff and I luxuriated in.

I returned to serve as a trustee a decade later, where I felt it imperative to articulate the original ethos of the place. SPACE, we now consistently remind ourselves as directors is not merely a studio provider but an acronym: Space, Provision, Artistic, Cultural + Educational. It is our duty to serve and embody this by nurturing and fostering a sense of community—one that Sedgley and Riley fostered and nourished. I attempted to square this circle by founding a committee for Access, which focused on racial equity, social mobility and studio access, as well as disability. ‘The thing about art is that it doesn’t discriminate’, I said at first. ‘Yet, it’s makers [including artists] and institutions, often do, and often do so unconsciously’, I recall this being my opening gambit.

I knew if it were not for SPACE, for Sedgley and Riley that the shape of my life would look very different. Sedgley’s practice in a sense has continuously extended beyond the confines of pure object making. He was also a maker of experiences, a convenor of worlds. Likewise, his contribution to founding these multiple sites of work and imagination lend themselves to another point of reference and inquiry—namely Sedgley’s interest in what he has referred to as ‘fusionist’ thought and work. Here one can reason with his interest in fostering a union of cultures, of ideas, considering the dissolution of factions.

Sedgley’s references to ‘fusionist’ ideals invoke the synthesis between the interiority of the artist passing through an exterior realm into another person’s culturally situated interiority. In the 1960s, art was an experiment that orbited around the individual as much as it did a community. The search for communion led Sedgley down a path to the storied constructivist, Systems Group. The core membership included the likes of Jeffrey Steele and Peter Lowe. Simultaneously, he and Riley taught art together at Byam Shaw School of Art (now absorbed as part of Central St Martin’s), among other places. Together, they stirred a generation of the world’s leading art and design professionals, including famed students such as James Dyson.

Sedgley was inspired by figures such as the controversial artist and educator Harry Thubron, who emphasized the study of ‘visual literacy’ over technical skill development in fine art degree programmes in the UK3. Nevertheless, he has consistently remained modest regarding his contribution to the field and space of influence—never attesting to or making grand claims in his writing or annotations. Despite embodying the profile of the heroic painter—tall, slender, moustached, sporting biker jackets, he was also from a self-professed ‘working class background’ and served in the British military in Egypt—a polemical issue that is discussed in the endnotes. Notwithstanding the stripes and adornments that he embodied, Sedgley preferred to stay clear of the limelight, rarely giving press interviews for instance in the last several years, except to trusted confidantes.4

Other collaborations included a tenure with the notable performance artist, Bruce Lacey who has resurged in popular consciousness for what were deemed his

‘eccentric’ cabaret-like showcases. Also in this group is the iconic assemblage and systems artist, John Latham. The three of them formed Whscht (Pronounced: Whistle). The collective intervened in everyday events through provoked and staged happenings.

Prior to SPACE, its progenitor, an initiative propelled by Sedgley was A.I.R—the Artist Information Registry, which would later merge with SPACE—many are confused by this. At the outset, the idea of A.I.R seemed simple. This was a place for any artist interested in contemporary art to list their contact information, to propose projects, and share artworks, or commission ideas, that could be sold or exchanged in a public arena. The goal was to ‘cut out the middleman. No more agents noted Bridget Riley’5 Autonomy was a crucial vector even in the sphere of Sedgley’s desire for a collective impulse. The listings attracted illustrious names and extravagant proposals for commissions by the likes of artists such as Frank Auerbach to David Bowie.6 Like all of Sedgley’s endeavours, at the core, or in effect, the result is a rhizomatic structure. It fashions a spectrum that seeks to move, upturn, unsettle, sometimes unbuckle a given context, but where did all of this leave Sedgley’s luminous art?

The paradox of deconstructing Peter Sedgley’s enigma returns me to the artist’s most substantive catalogue, produced in 1996, and authored entirely by the artist— Peter Sedgley: Painting, Kinetics, Installations, 19641996. The cover is a picture of restraint –or at least in my case. The copy that I have is entirely blank bar for a mere ‘S’ printed atop a faded Royal Blue. Inside its pages, it seems that Sedgley has decided to nullify certain assumptions. There is ‘no Sedgley idiom’, he professes. He also dismisses artistic movements and ‘isms.’7 Conversely, nearly a decade later, in a 2004 exhibition catalogue, Jasia Reichardt, former director of Whitechapel Gallery, London and curator of the landmark exhibit, Cybernetic Serendipity, which was held at the Institute of Contemporary Arts London in 1968 professes to Sedgley’s legendary status. She begins by asserting that he is the only British artist to be

associated with all three of the movements associated with illusion, light and motion: Op Art, Kinetic Art and Light Art.8

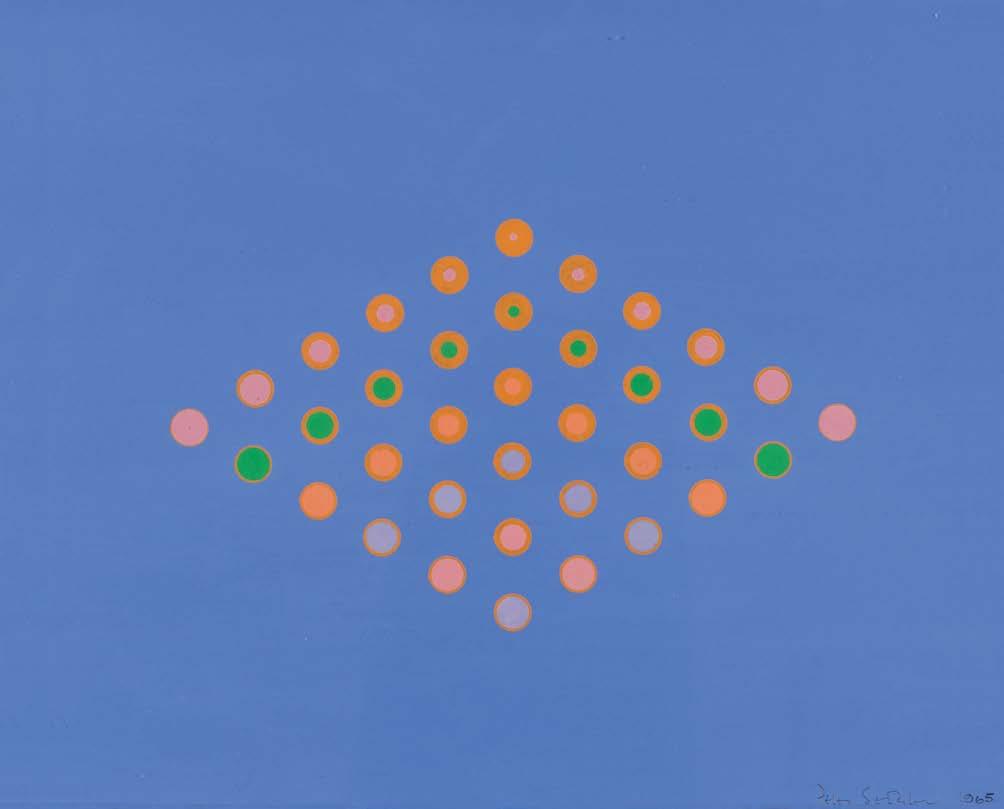

I return to the mid 1960s, my hand gliding over an exhibition guide produced for an exhibition at McRoberts & Tunnard Gallery held at 34 Curzon Street, London. Here, the philosopher Cyril Barrett locates the reader by articulating the influence of Kandinsky and Klee on the artist. Sedgley has repeatedly professed that Klee and Goethe fuelled his disciplinary studies in colour. The cover of the pleated accordion-like matte booklet showcases a painting called, Cycle, 1965. It looks like Kandinsky on acid. Peering at it nearly 60 years since it was printed, this round foil is at first suggestive of an abyss, that is, until the gaze, the spectrum of colour circulates around this orb, revealing the finely tuned details. Lines that shimmer, suggestive of energy. The eye wanders back up the spectrum and around again.

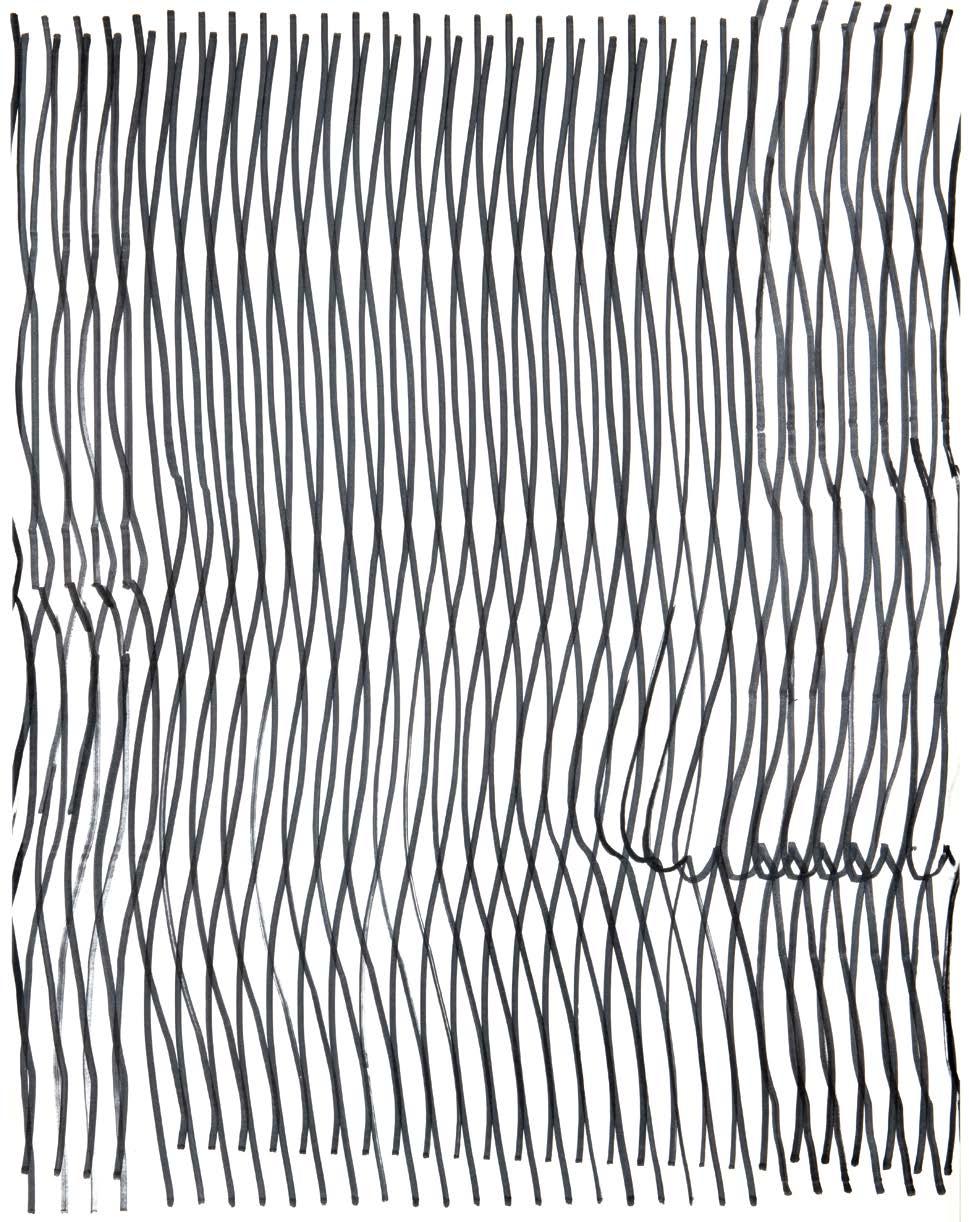

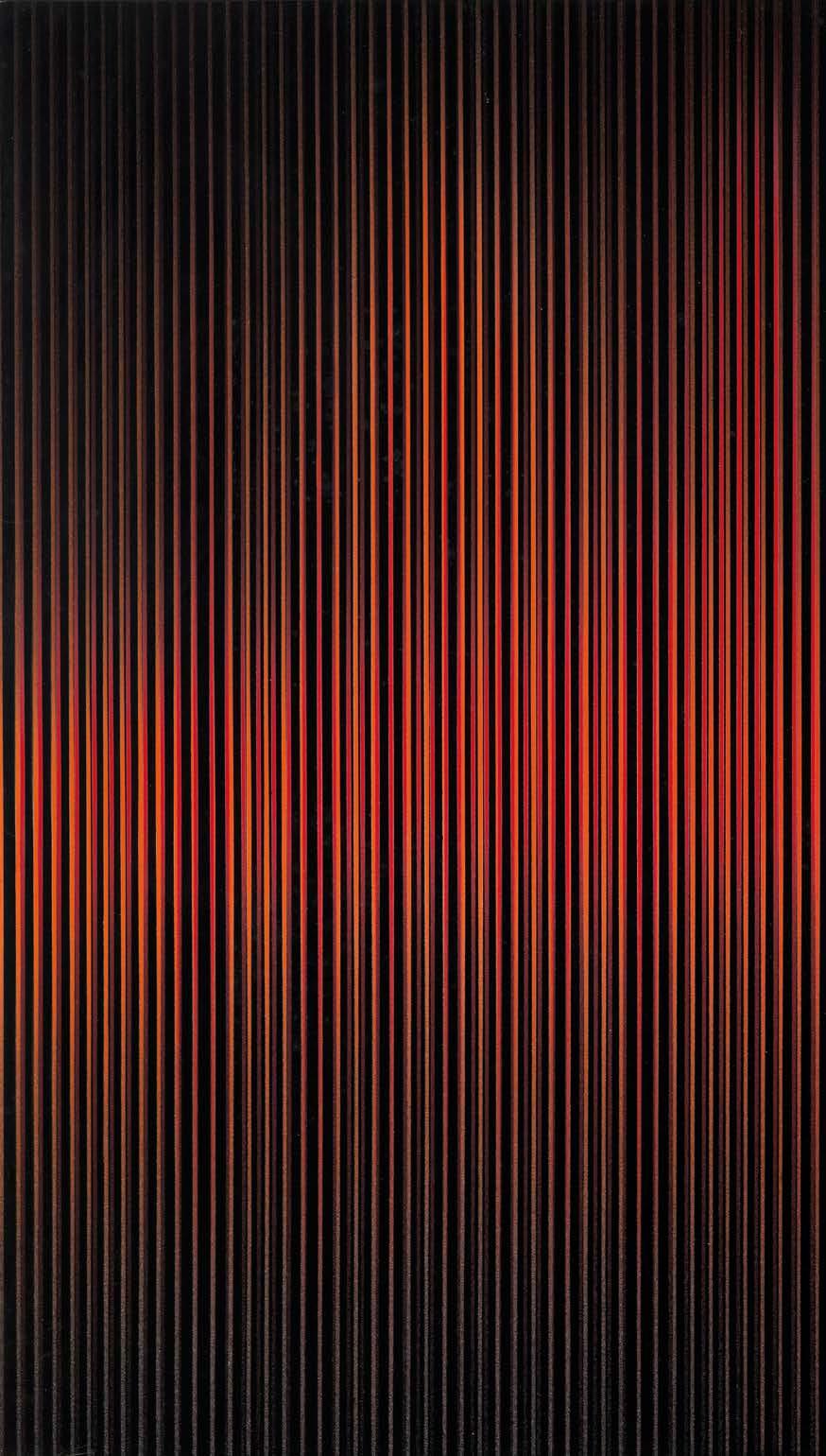

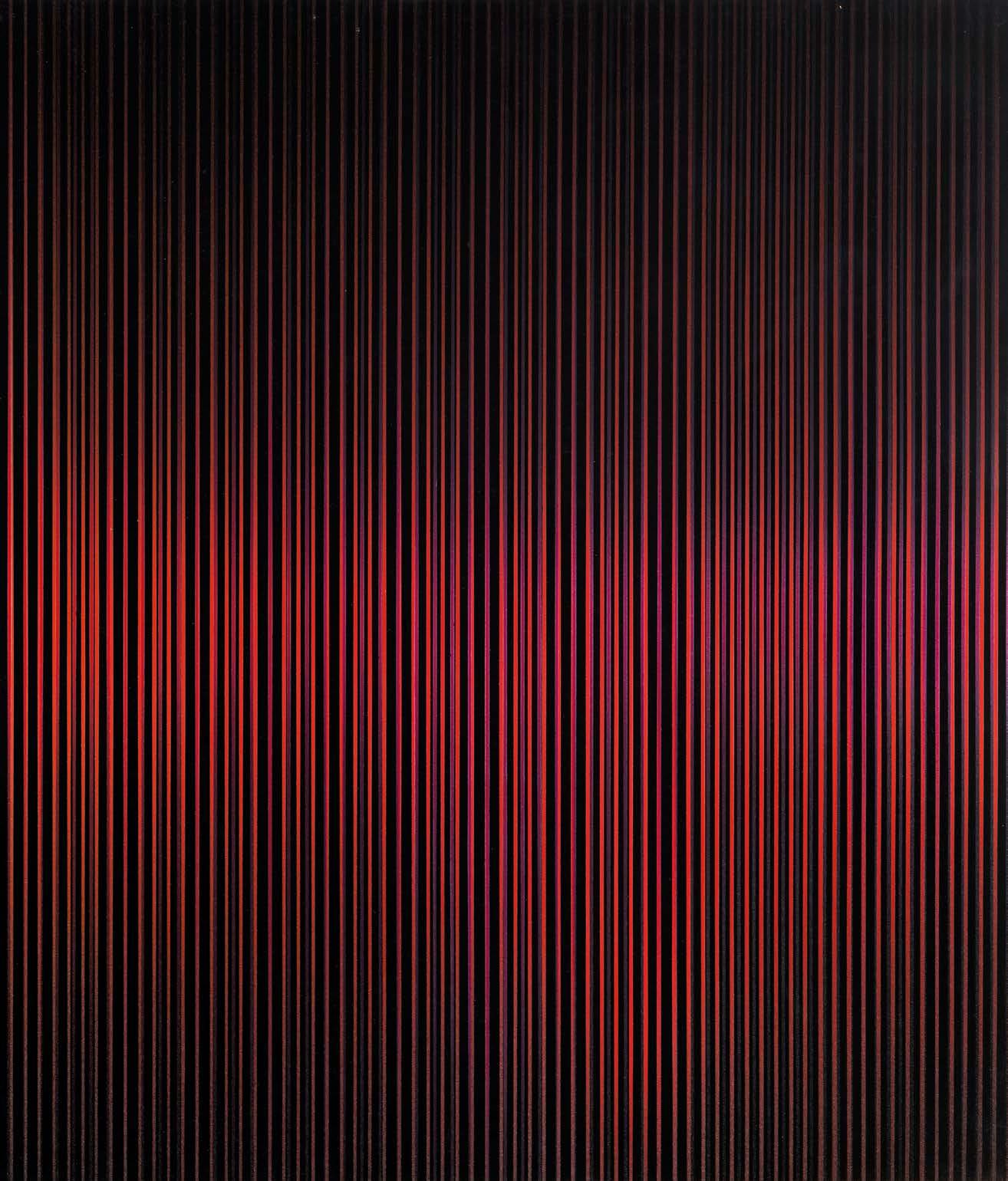

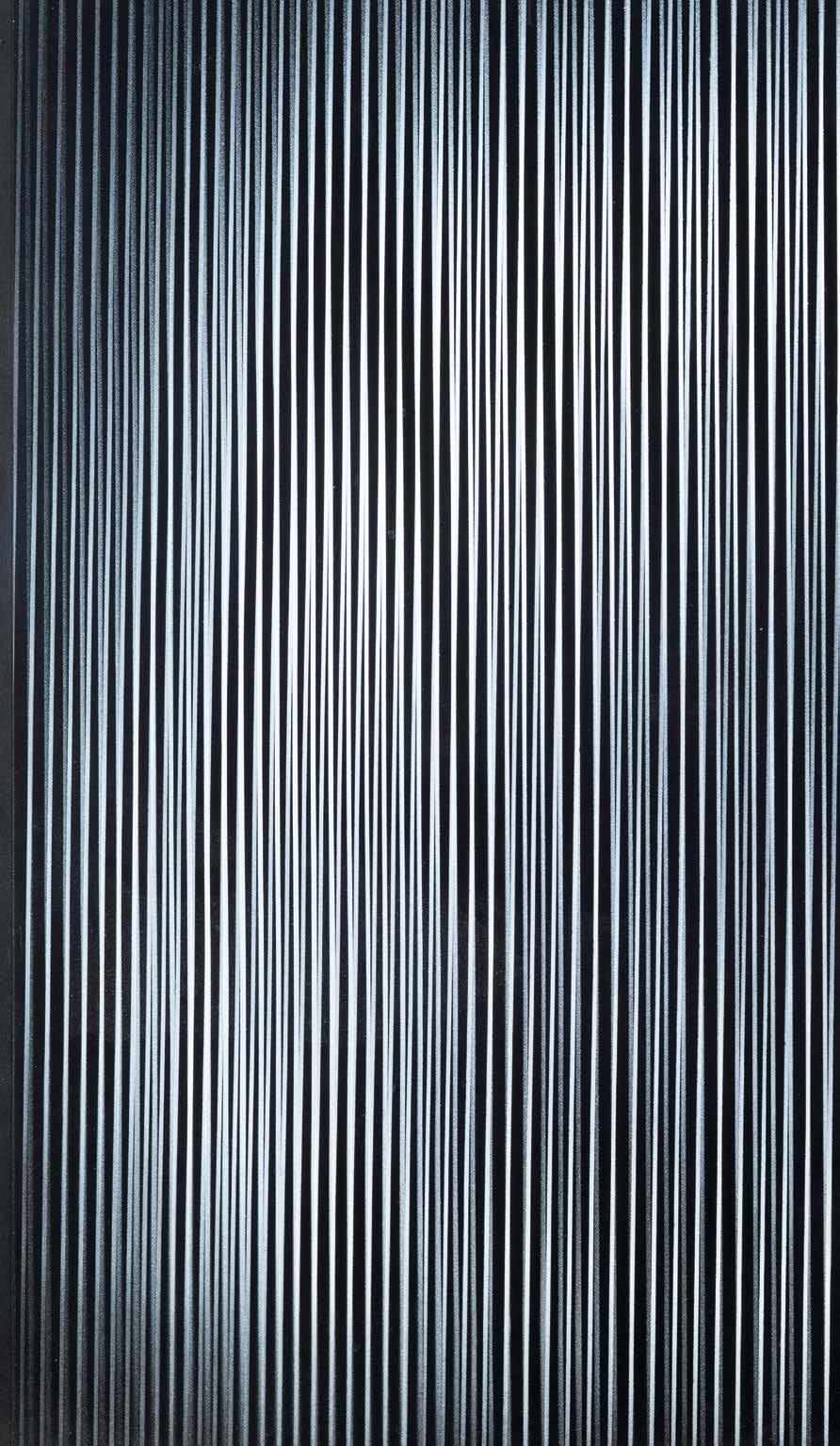

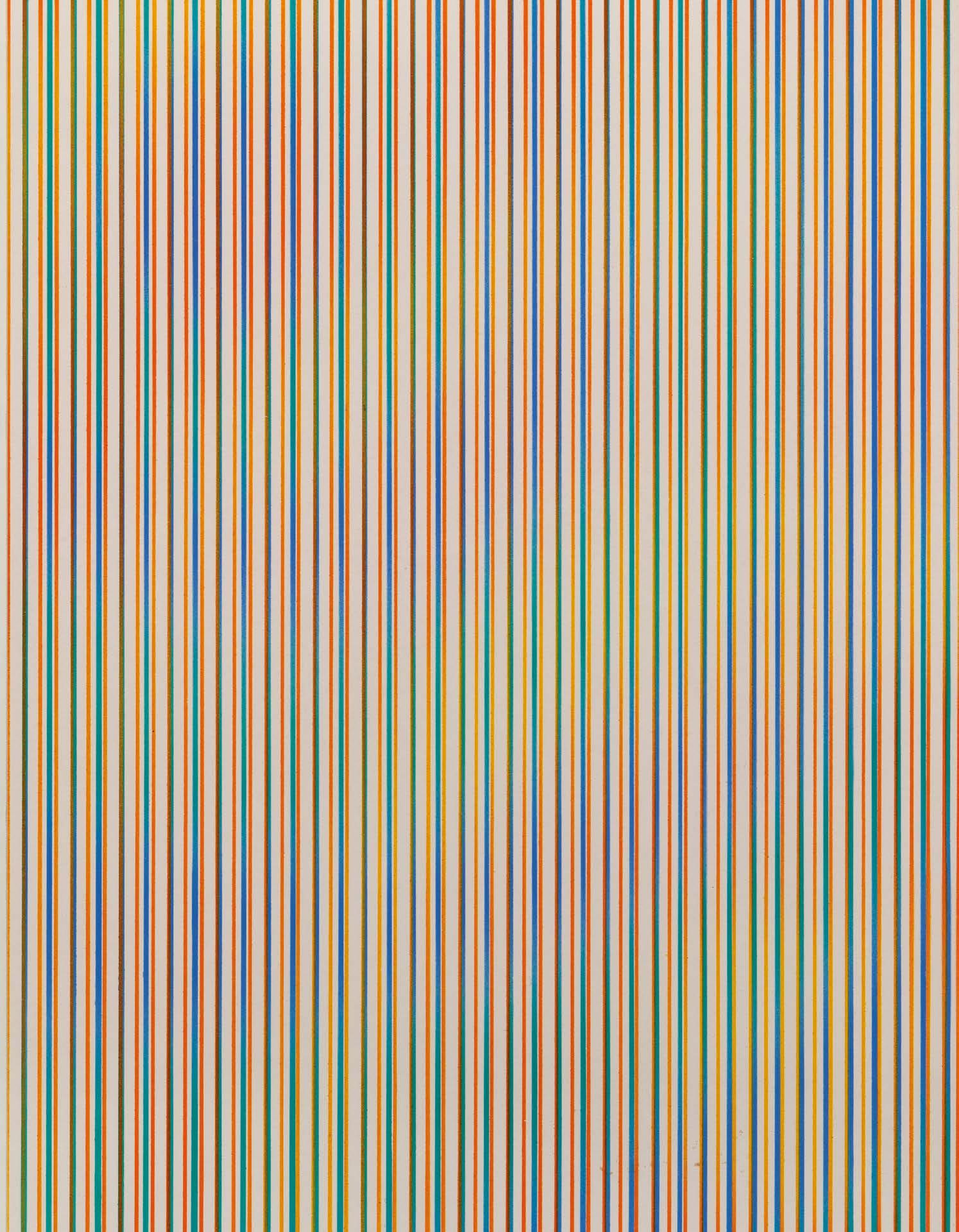

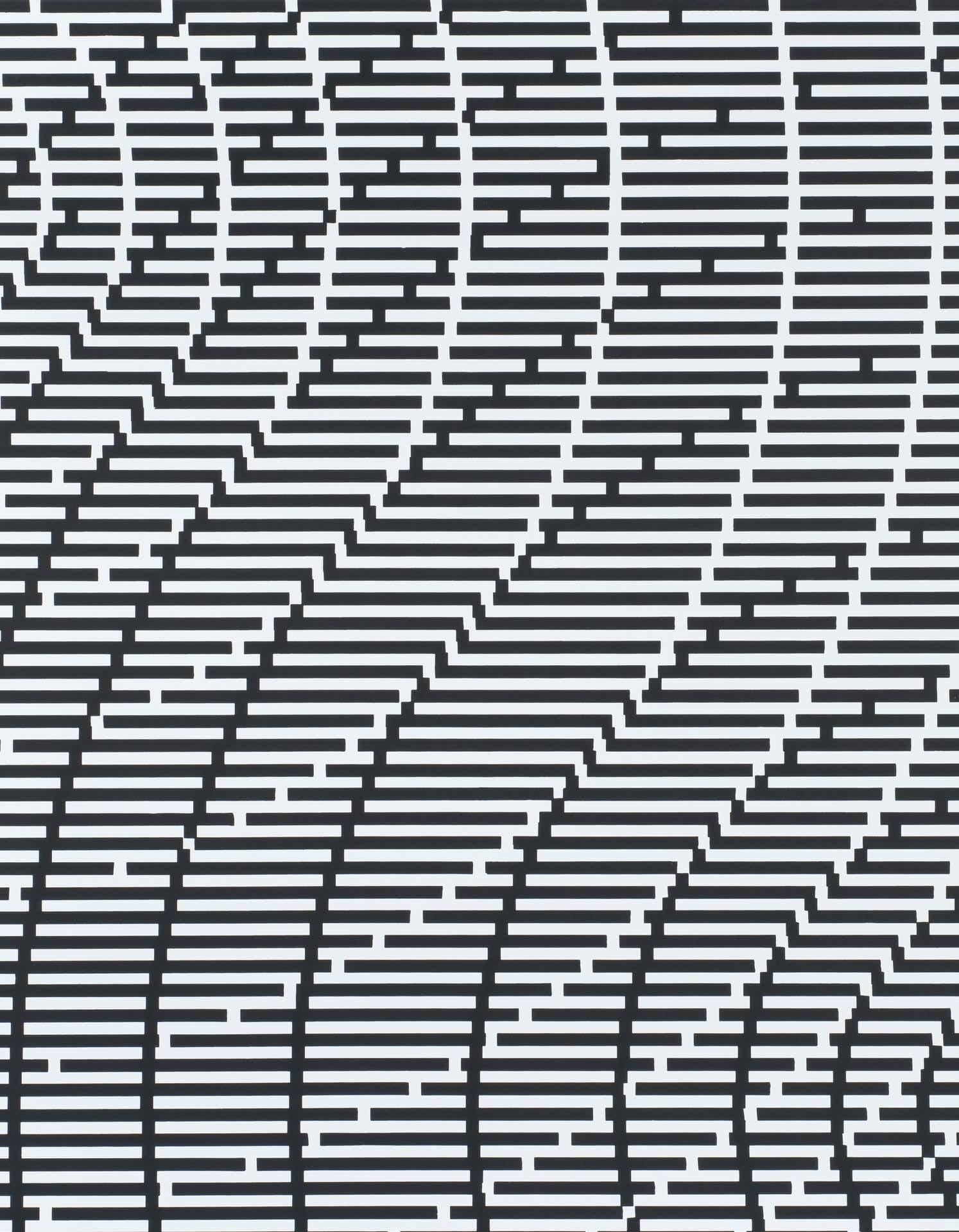

Examining the space between the lines, what is within the interstice, is perhaps at the core of Sedgley’s aesthetic practice. Marker pen and ink drawings on large paper such as Eye Sign, 1982 or Zotow IV, 1982, evidently embody the disciplined Op Art techniques of his comrade in arms, Bridget Riley. They are also whether he likes it or not very Sedgley. They both boast their own sense of chaos—of an unfurling that is about to begin. It is a much messier dance, and he, and we, by turn are okay with that. Reflecting back on Riley and Sedgley’s relationship, it is evident that a kinship of form and mind continues to exist to this day. According to one source, Riley attributes Sedgley with teaching about ‘geometry so that I could make the things I know out to be’.9 The irony is that with Sedgley nothing transpires to be what we had first assumed it to be. Returning to Eye Sign and Zotow IV, although at first are seemingly monochromatic, they both correspondingly rupture the notion of stillness. With each glance, the in and the out breath, the body ascends into perpendicular cross-sections that are finely carved out into the landscape.

At any given moment, one thing is certain, Sedgley is pulling from within, making that interstice, those cracks between the seams in the landscape visible to us: Could this be a metaphor of and for the unseen,

the dispossessed, a foil, for my, or your feelings? The question lingers.

Drawing out from the flatness of the page, the screen, or the light source, Sedgley presents evidence that consciousness does not settle until its finds its mutual resolve.

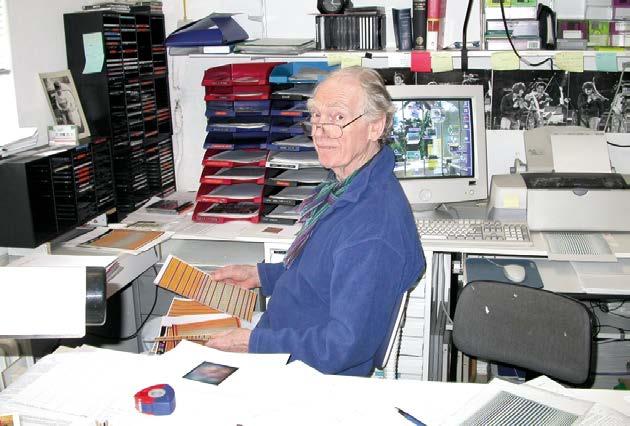

Reflecting on his methodology in 1996, Peter Sedgley noted that he enjoys a slow, methodical, precise journey towards the end. He is someone less concerned with personal fame and instead occupied with the ‘humanising’ aspect of making art and as a consequence ‘humanity’s role’ in the project of art as opposed to aligning with an artistic grouping or collective.10

Standing outside of The Redfern Gallery before I enter to discuss the context of this exhibition, I reflected on Sedgley’s words and writings. Taking in the final drag of my cigarette on the street corner, I receive a video message from one the world’s greatest living artists, Sean Scully—a Londoner, a British artist, an Irish artist an American artist, a fusionist. On my phone, I see Scully at a podium at Centre Pompidou in Paris on the eve of a new exhibition opening. In a short and elegant speech, he reminds us of his commitment to revealing the ‘humanism’ behind ‘abstract painting’—a discipline and a commitment that he has made his life’s work. I watched the video again. Amen, I muttered as I entered into the chapel-like vestige that is The Redfern Gallery, an artist’s safe haven for over a century.

Certainly, here, in places like this, these were the sites that Scully had intended for us to engage with abstraction— from material to feeling. In this regard, Sedgley and Scully could be said to be somewhat kindred spirits. Both artists are propelled by a similar philosophical pursuit of the humanistic.

Colour or its absence is a driving investigation. Their careers, one could say, exist in parallel. Sean Scully’s first exhibition was held at the famed Rowan Gallery,

London in 1973. One of Peter Sedgley’s earliest exhibitions was mounted at the Rowan Gallery in 1962. Like Scully, Sedgley often chooses to speak and write about his own work and has kept a close and small group of confidantes who have served as his chief interlocutors. Cyril Barrett, author of Sedgley’s 1965 catalogue essay is a philosopher, who helped cofound the modern-day philosophy department at the University of Warwick. Barratt became inspired by his long-standing dialogue with Sedgley and his comrades and would go on to author the first major survey of Op Art and in later life. He also collected Op Art and donated his collection of contemporary artworks, which included several significant Peter Sedgley paintings to the Mead Art Gallery at the University of Warwick, which thus helped form a cornerstone for one of the nation’s significant university museums.

Peter, or was it Richard Gault at The Redfern Gallery, who sent me this piece of writing, I scratched my head? It is a beautiful, thorough and well-argued text on expanding the field of colour in Sedgley’s art by Italian curator Luca Cerizza, authored in 2014. I was delighted to read it and perplexed all the same.11 That is the thing with Peter Sedgley’s art, it leaves you with questions that are too complex to decode in an instant. The question of colour is the challenge of a lifetime.

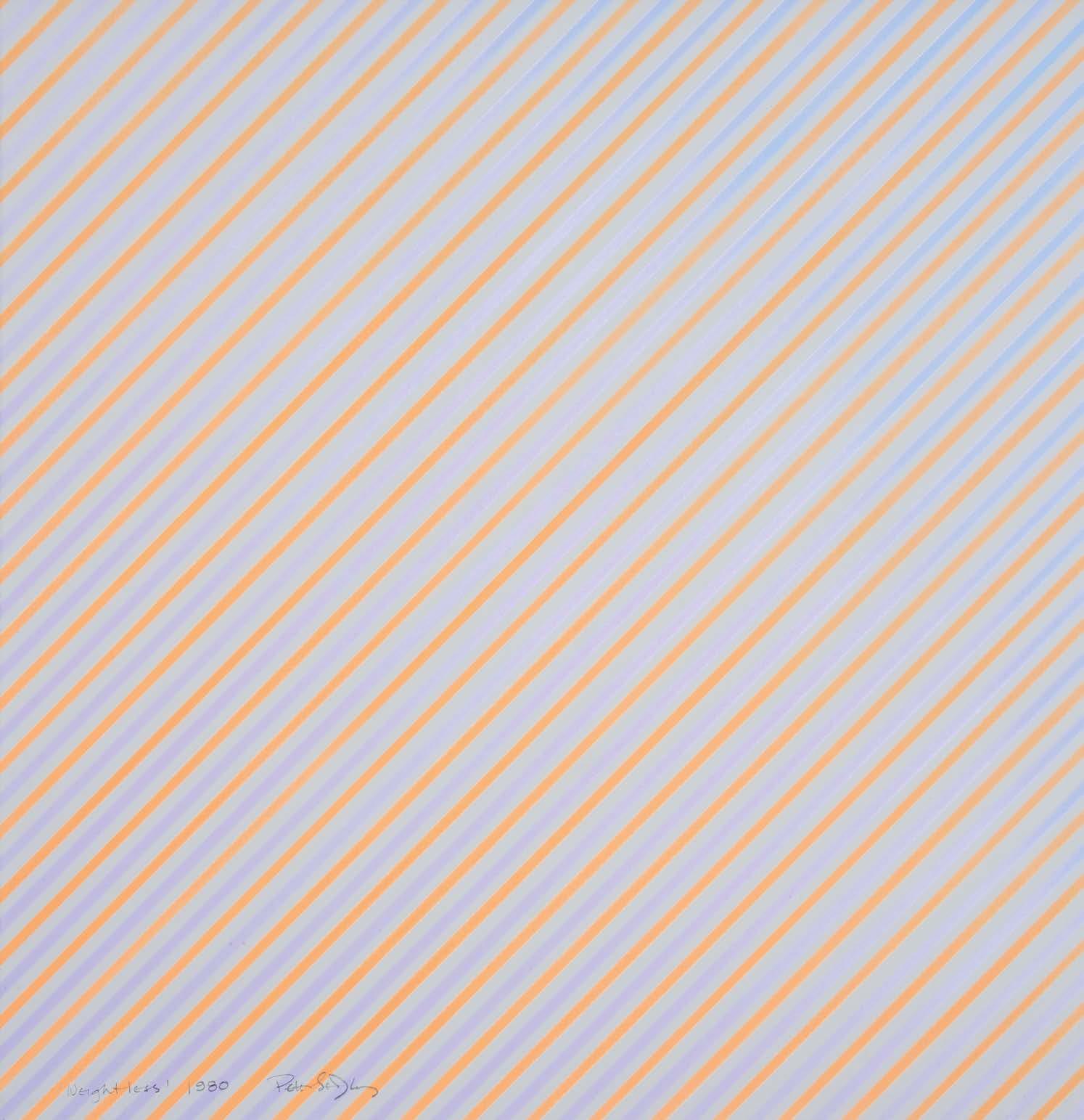

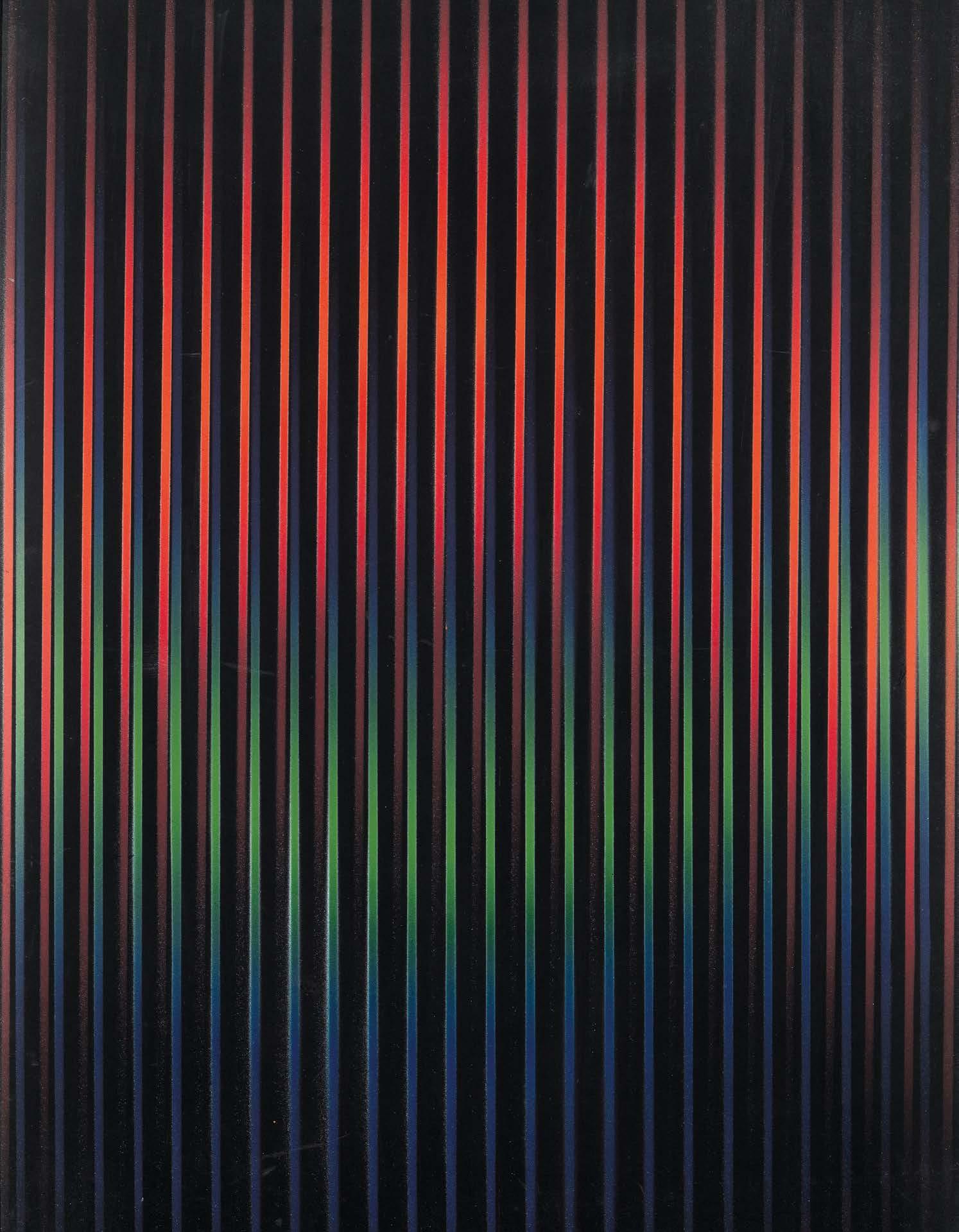

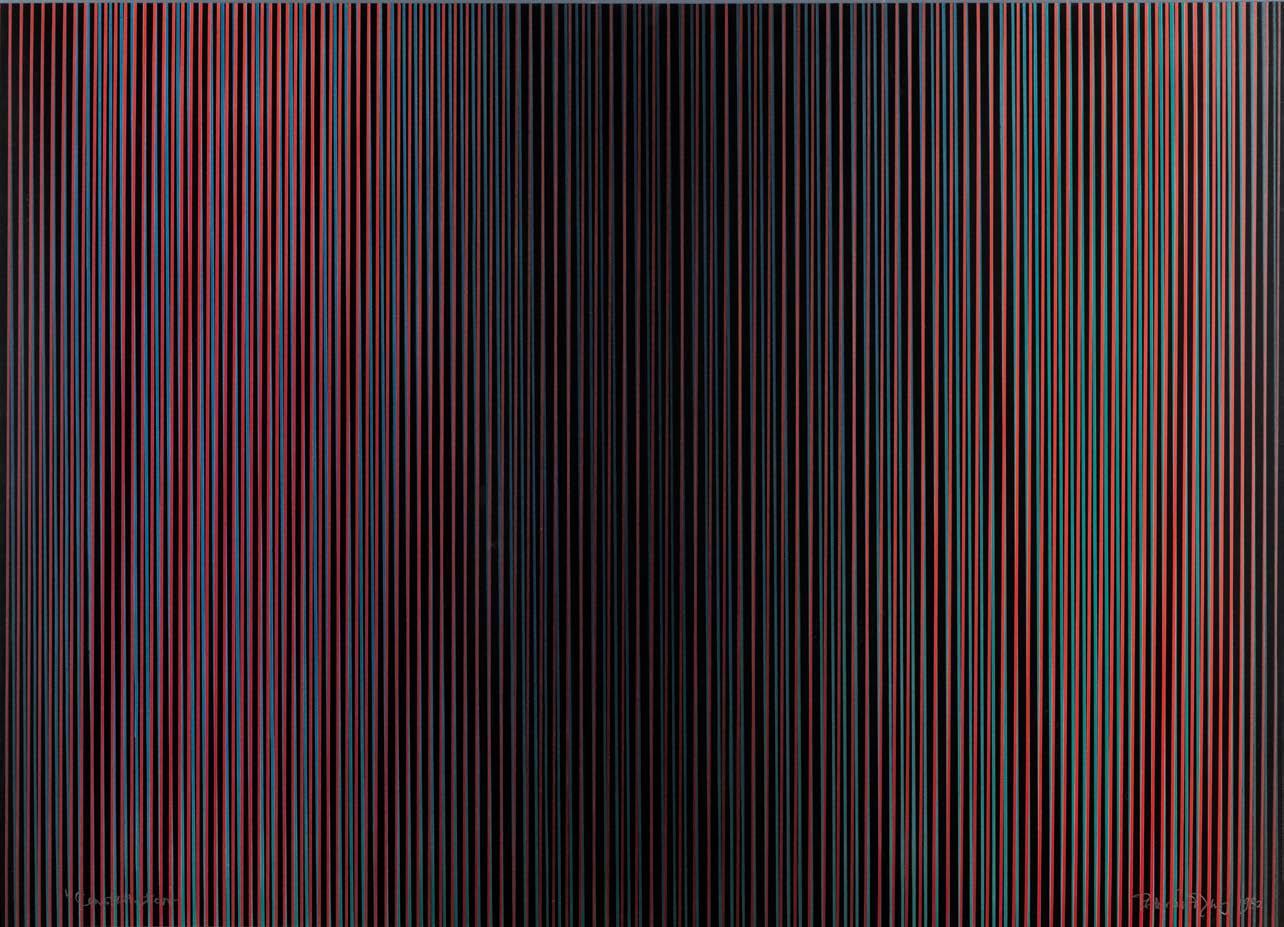

I gaze at Sedgley’s acrylic on linen, Cryptic, 1982, featured in the exhibition, and I feel as if I am in the Matrix, not just the movie, a matrix of my own making. The oblique stripes, seem to have bodies that have sedimented within, or am I hallucinating. According to Cerizza this was part of a conscious interplay of colour choice and application to foster the illusion that a light source was impacting these paintings—spectral, spectrum. Still, these are not ghosts, but rather haptic spaces to be touched and entered, desirous ones for touch. They are part and parcel of an erotics of colour—a disciplinary practice that western art history has historical found troubling.

It is in this nook that I query: What is lost to history, and what can be resuscitated through experiments with light, which reach the ocular, and in turn, the mind?

British artist David Batchelor famously argued that since antiquity, the western world has ‘reviled’ colour. Certainly, white space, white cubes, the concept of whiteness as a race is a constitution, a construction that desires, and requires sullying, tampering with. It demands a poetics of creolising to invoke Martinican author, poet and philosopher, Edouard Glissant. Glissant’s argument of creolisation is to create ‘a capacity for [human] invention’ and intervention. It is a space that allows for a process of ‘becoming’ to occur. Sedgley whose experiments with colour moved between minute studies of pigment and their application to the rainbow, incorporating knowledge from industrial chemistry, film and television, theatre, print media and beyond, was doing something extremely subversive. He was and had always been engaging with the mass medium of the time, whether through his ‘Videodomes’ or his inkjet prints—to spark back the erotic sense in the human imagination, to invite us to claim it back for ourselves, inching us towards a vital space of and for ‘becoming’.

Becoming for Peter Sedgley involved many moments of retreat, to and from (west) Berlin to London to West Sussex, perambulating among them all, almost as if in hiding. For his art to ‘become’ and assume its legacy it demands something of us. To submit to it. Orbiting is the preserve of the web 2.0 Instagram fiend. Submitting however requires more than admiring an object’s beauty but engaging in its erotics and applying them to one’s own worldview. I find Edward Lucie-Smith’s description that

‘if beauty is in the eye of the beholder, then eroticism is in his or her [their] mind…it is the governing [force that will dictate] our reactions’.

Erotics then are an evocation that ask that we nurture and suture the mind—an oft untended vessel—the central operating system; the motherboard. In an age where the mind is being left subject to overload by so many different fields of manipulation, Peter Sedgley’s art serves as to counter-act, forming a counterbalance, a dialogue with you, and me and everyone we know.

In the end: Peter Sedgley is nothing short of pioneering. My colleagues at SPACE call him a ‘legend’. As do many whom I have met in the studios over the years.

Like everything Sedgley does, his art is not merely restricted to the domain of a specific type of picture-making. To consider his influence art historically one must acknowledge that Sedgley is an architect who builds worlds.

The story—evolves, and shall, still. Its constitution is in your hands, but first you must submit to the pleasures of Sedgley’s art and allow for the mind’s wisdom to do the necessary.

Dr Omar Kholeif is a British artist, author, curator and broadcaster, and director of collections and senior curator Sharjah Art Foundation (Govt. of Sharjah), UAE. Kholeif is a visiting professor in the school of art and creative industries at Teesside University, trustee of SPACE, London; founder of artPost21, a not-for-profit dedicated to exploring the interstices of art, technology and social justice, and Ambassador for Mental Health Research UK. They can be contacted via, www.omarkholeif.com, or www.artpost21.com

Endnotes

1 Peter Sedgley produced several exhibition catalogues during his lifetime, many with commercial galleries, and several produced independently with grants from the Arts Council of Great Britain as well as from German funding bodies. To attempt to cite them formally would be a difficult task here as the books do not necessarily have titles, or page numbers, only dates of publication and ISBNs: I have done my best below in the limited scope of time afforded to me. All of my quotes throughout this essay by Sedgley are gleaned from nearly a dozen catalogues, pamphlets and leaflets, which will be on view at the exhibition at The Redfern Gallery. The ongoing project of properly indexing and archiving these datasets alongside the artist’s own writing is one to come. This essay, this book, this show is a summoning for that to happen.

2 Here I am citing Cyril Barratt’s exhibition essay in the leaflet that accompanied Sedgley’s 1965 exhibition at McRoberts & Tunnard Gallery.

3 Harry Thubron: Collages and Constructions 1972-1984 (March 2007). London: Austin/Desmond Fine Art.

4 Sedgley’s military service in Egypt has always been a curious question for me. At the time, Egypt would have still been in the process of decolonisation. My grandfather, who was born in Sudan, but lived in Egypt,

a decade older than Sedgley described the period when Sedgley was stationed in Egypt as a violent one. The British he referred to as ‘merciless’ and ‘violent’. Although, my grandfather would spend a decade living in Britain—he was a noted cardiologist who was summoned to assist during a shortage of medical practitioners, and although his eldest child was born in Britain, he himself refused to naturalise or hold the British passport. This made it very difficult for me and my circumstances growing up, being constantly funnelled from country to country.

That Egypt is nary mentioned in relation to Sedgley’s interest in colour (by him or others) is peculiar to me and requires further investigation. Particularly as one Sedgley’s closest early compatriots, Bridget Riley who inspired his disciplinary practice, would go on to produce a boundless body of work inflected and influenced by Egypt’s topography, colour and landscape. Riley fashioned what she called her ‘Egyptian palette’. The absence of this discussion here begs for more and will hopefully come in time. Again, this project is a summoning of a sort.

5 See: Jonathon Jones (2008) ‘The Life of Riley’. Available here: https:// www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2008/jul/05/art1#:~:text=And%20 so%2C%2040%20years%20ago,a%20hearing%20from%20the%20 establishment., accessed 23 October 2024.

6 The SPACE and A.I.R. Archives were donated circa 2012 to the University of the Arts London, where they may be consulted by scholars. They form part of their special collections’ library. Further holdings are deposited at SPACE HQ in the CEO’s Special Archives and may be available in exceptional circumstance.

7 This statement is gleaned from one of his many assertions in the singleauthored blue exhibition catalogue, published by Sedgley in 1996, entitled, Peter Sedgley: Painting, Kinetics, Installations, 1964-1996. Supported by the Arts Council of Great Britain among others.

8 Jasia Reichardt (2004) ‘Into Space’. London: Austin/Desmond Fine Art. *There are no page numbers, but it is on what would be considered pages would be pages 4-6.

9 Jonathan Aitken (1967). The Young Meteors. London, UK: Secker and Warburg. p. 198. ISBN:3928342177.

10 Quoting Sedgley from 1996 from Peter Sedgley: Painting, Kinetics, Installations, 1964-1996.

11 Luca Cerizza’s essay is available online for the time being on Peter Sedgley’s website. Available here: https://sfxart.com/an-introduction-toop-art/, accessed 23 October 2024.

Study 1964

30.5 × 24 cm

Titled, signed and dated

Untitled 1964

Screenprint

15.5 × 30 cm

8 proofs printed

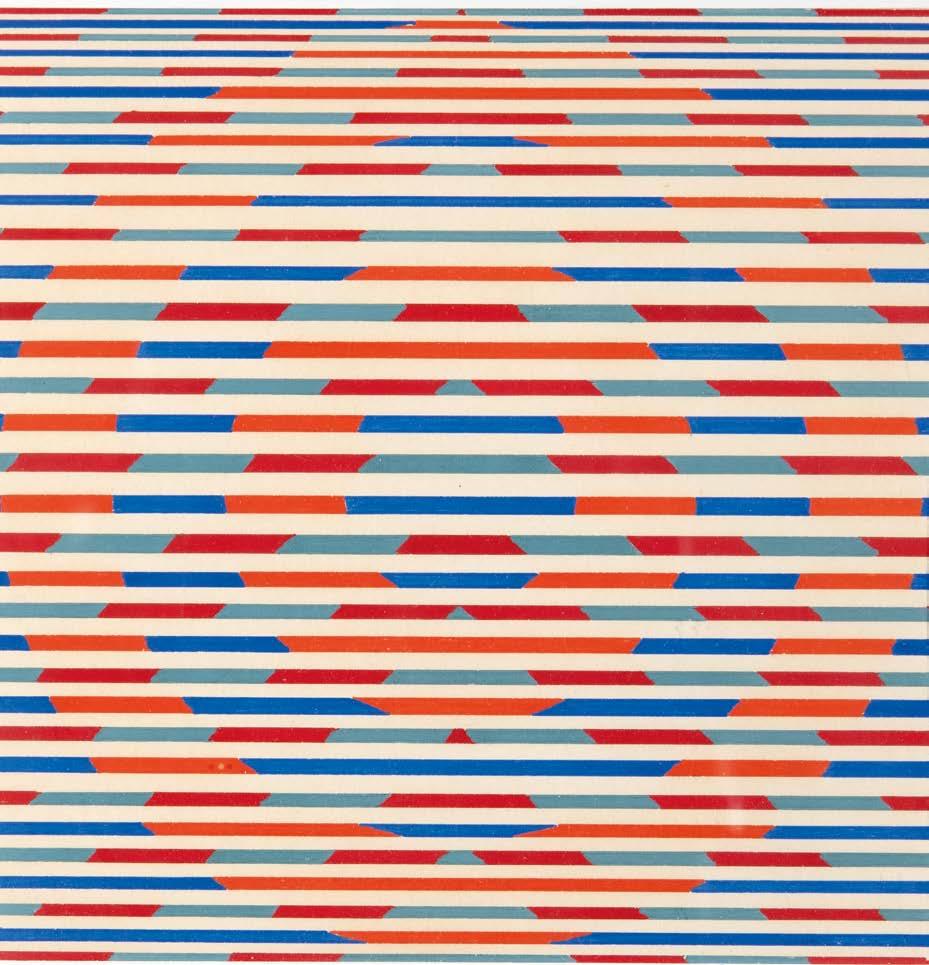

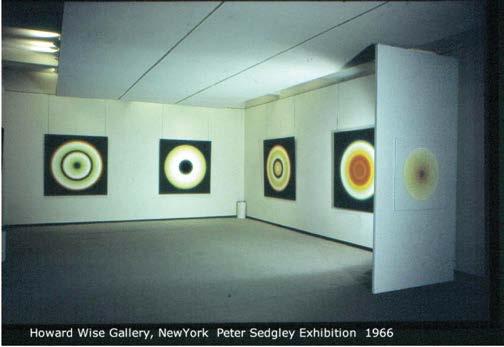

Synthetic polymer paint on masonite

104 × 104 cm

Signed, dated and titled on reverse

Exhibited

Howard Wise Gallery, New York Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1965 (Museum No: 66.76)

Acrylic on canvas laid on board

58.5 cm diameter

Signed, dated and titled on reverse

Signed, dated and titled on reverse

Signed, dated and titled on reverse

Signed, dated and titled on reverse

Red Action 1979

44 × 44 cm

Signed, dated and titled

Constellation 1966

51 × 51 cm

Signed on reverse

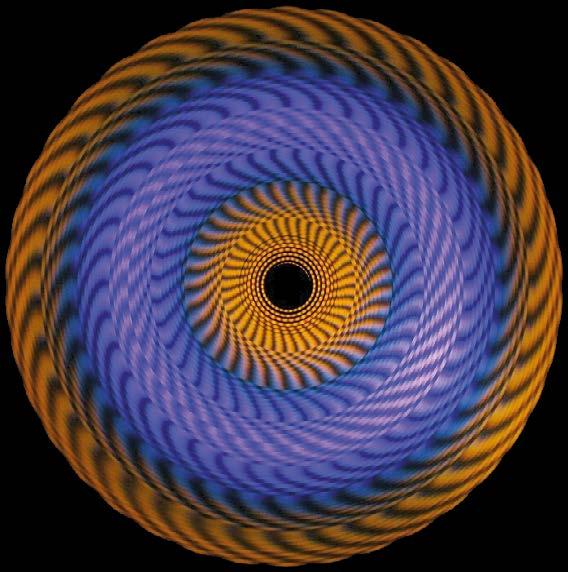

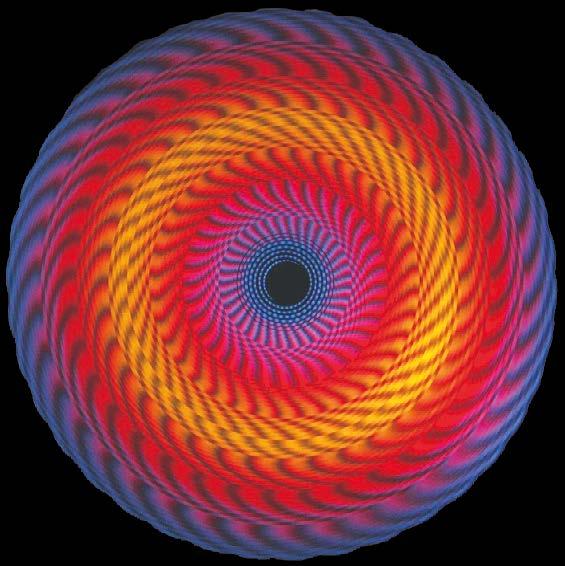

Video Disques 1969-70

Kinetic screenprints on spun aluminium

Each 75 cm diameter

(From the edition of 100)

Red Nebula 1973

PVA and fluorescent colour on canvas

150 × 150 × 4 cm

Signed, dated and titled on reverse

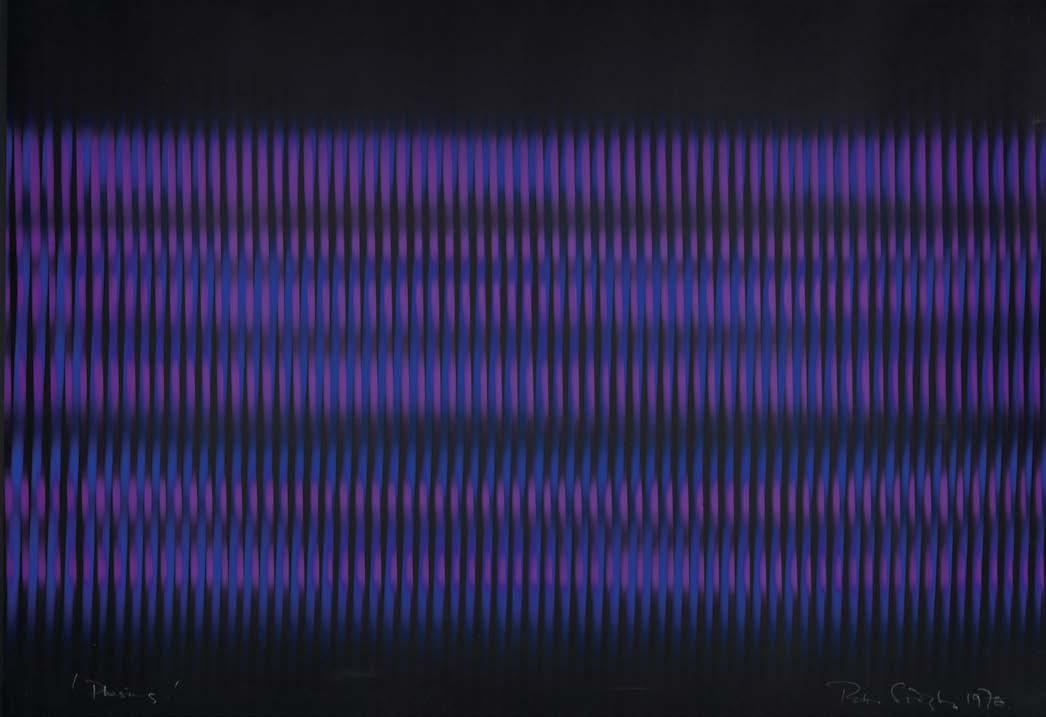

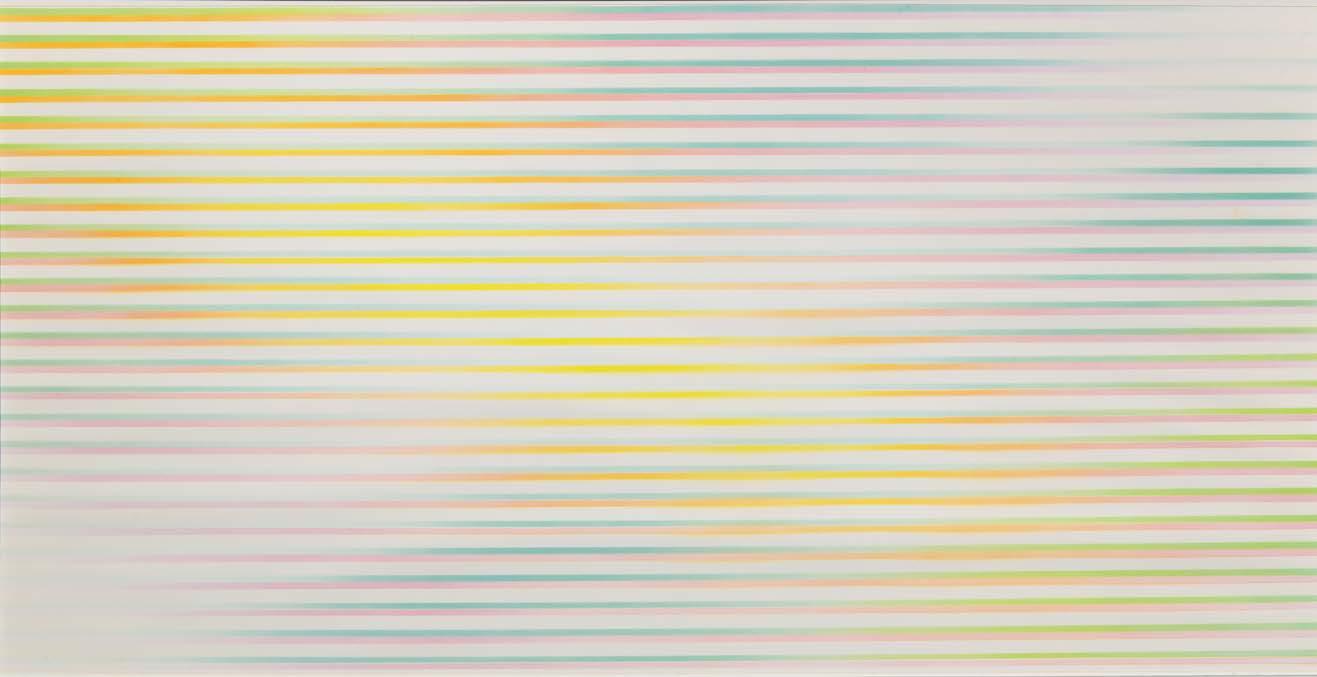

Phasing I 1979

Acrylic on paper

48 × 69 cm

Signed, titled and dated

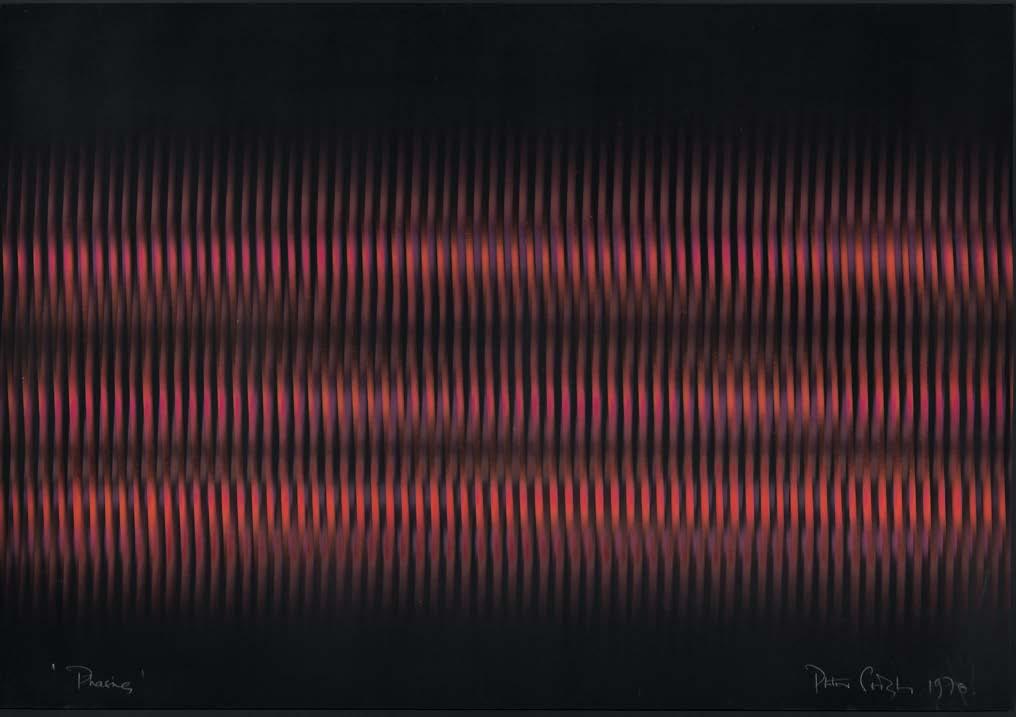

Phasing II 1979

Acrylic on paper

48 × 69 cm

Signed, titled and dated

Signed, titled and dated

Energy 1980

Signed, dated and titled on reverse

Signed, dated and titled

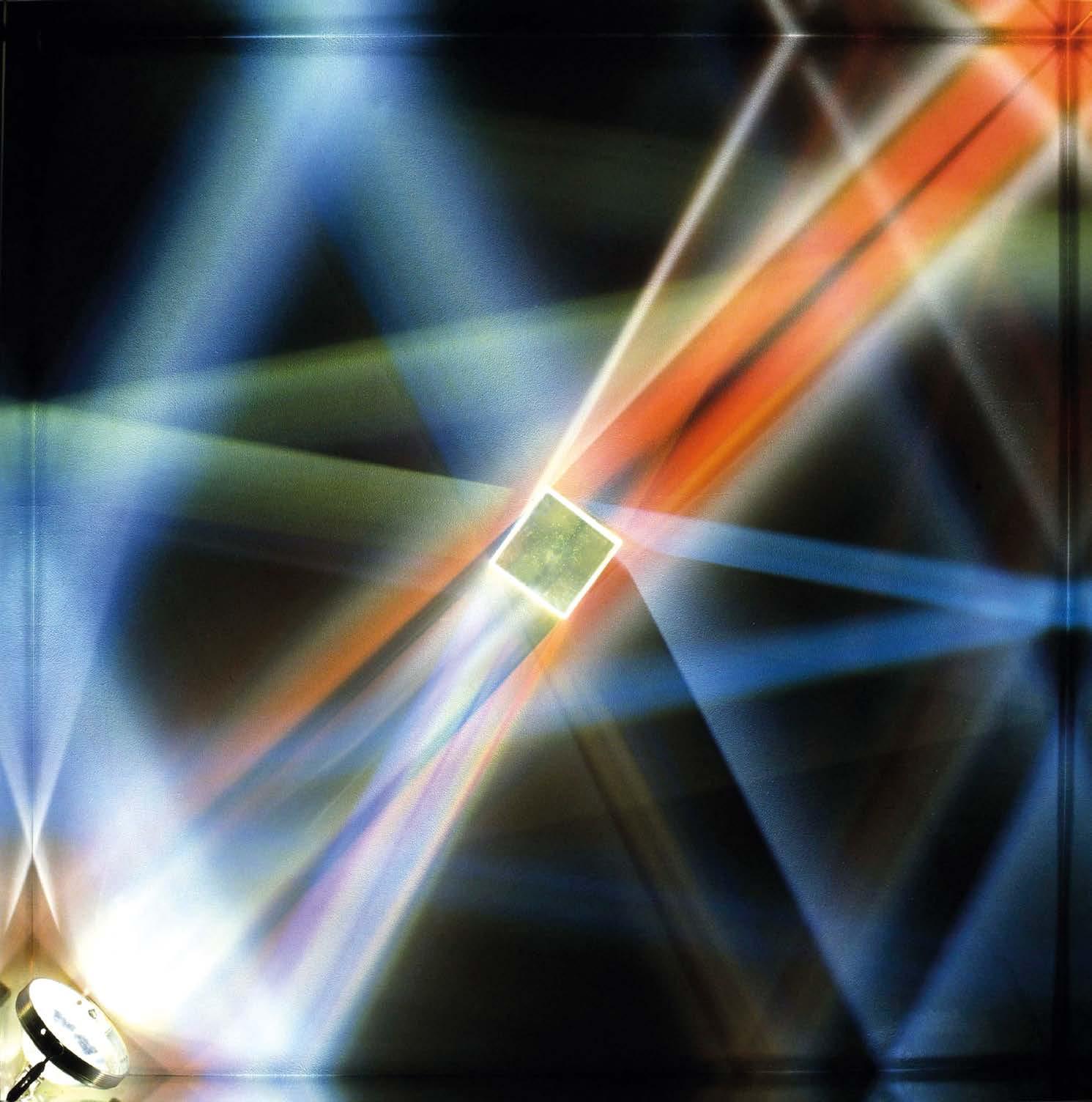

Square Dance 1980

Kinetic lightwork

120 × 120 cm

High Key 1980

Signed, dated and titled verso

Overtones 1980

Acrylic on card

51 × 97 cm

Titled, dated and signed on reverse

70 cm diameter

Signed, dated and titled

67 × 93 cm

Signed, dated and titled

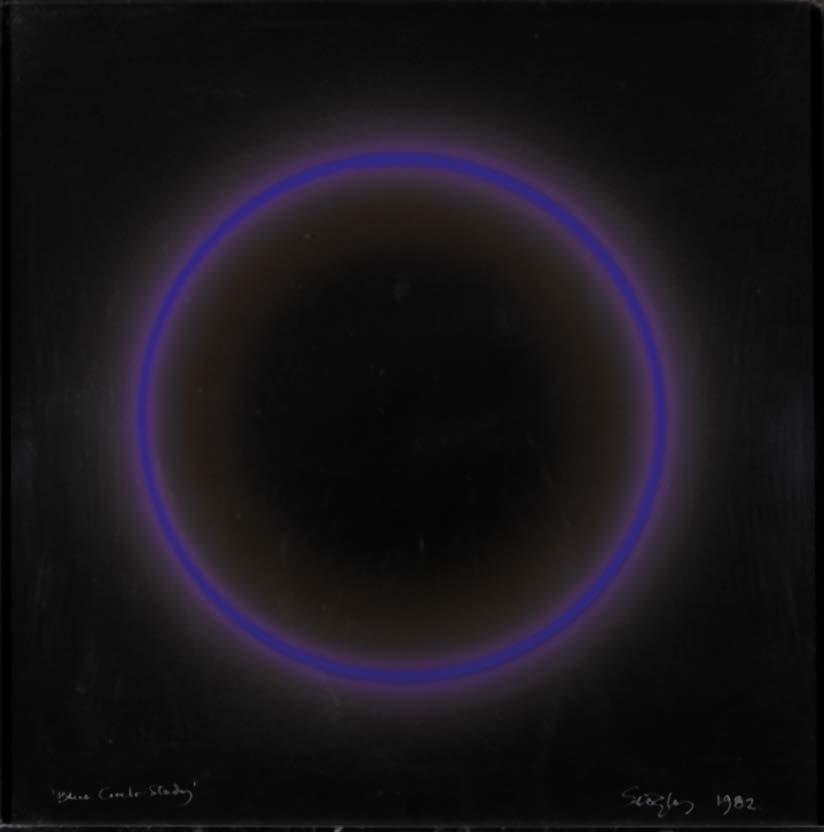

Circle Study 1982

Signed, dated and titled

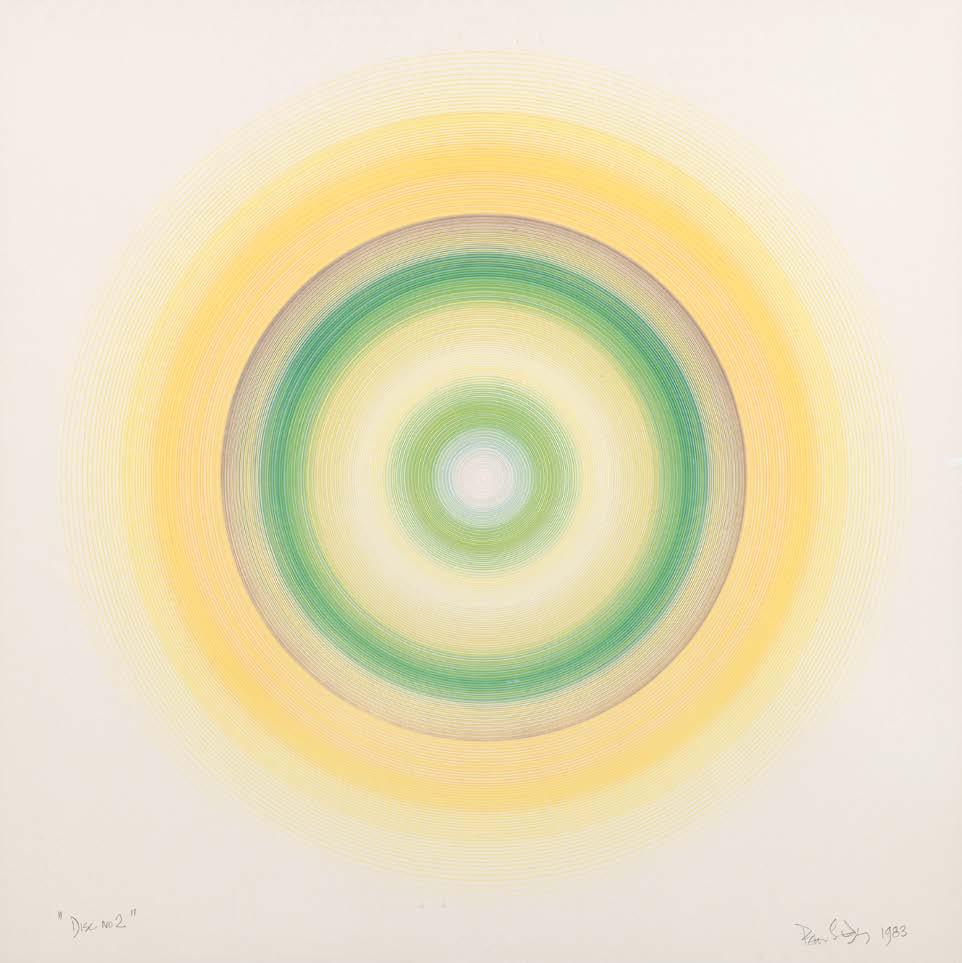

Disc No 2 1983

Signed, dated and titled

Eye Sign 1982

Marker pen and ink on paper

September 1982

Radials in 1982

Signed, dated and titled on reverse

Ripple 1983

67.6 × 48 cm

Signed, dated and titled

Quartet Suite – Yellow/Blue on Light Blue 1986

Screenprint

60 × 60 cm

Edition of 100 impressions

Quartet Suite – Red/Purple on Black 1986

Screenprint

60 × 60 cm

Edition of 100 impressions

Wall Plant 1990

Light kinetic wall display 13 × 12 × 12 cm

1990

Kinetic light environment display 50 cm diameter

Kinetic light environment display 115 × 115 × 50 cm

and Green Modulation (II) c.2000

[second version of the 1964 painting]

Counterpoint ‘64 2000 [detail]

Screenprint

68.2 × 67 cm

Edition of 150 impressions

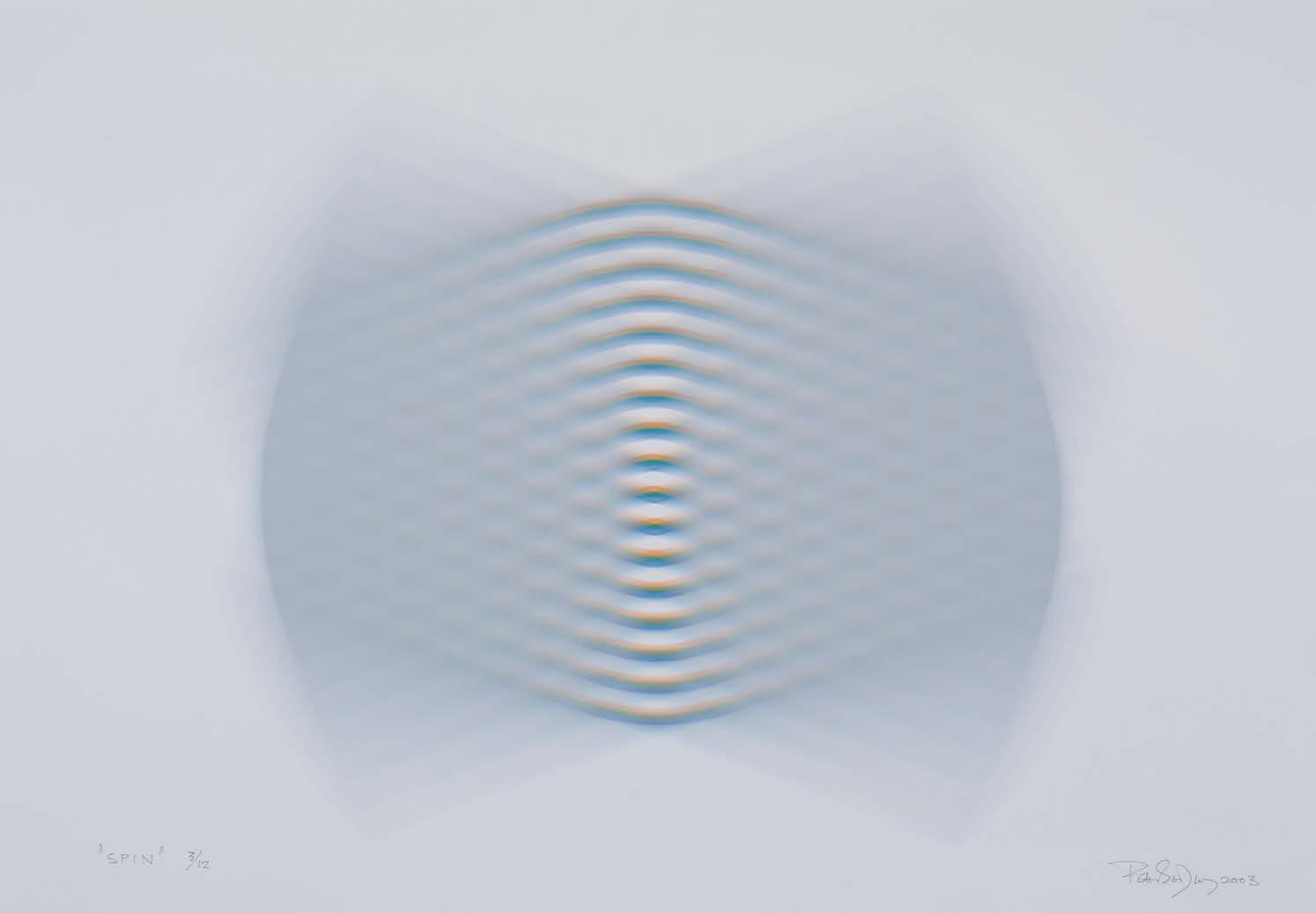

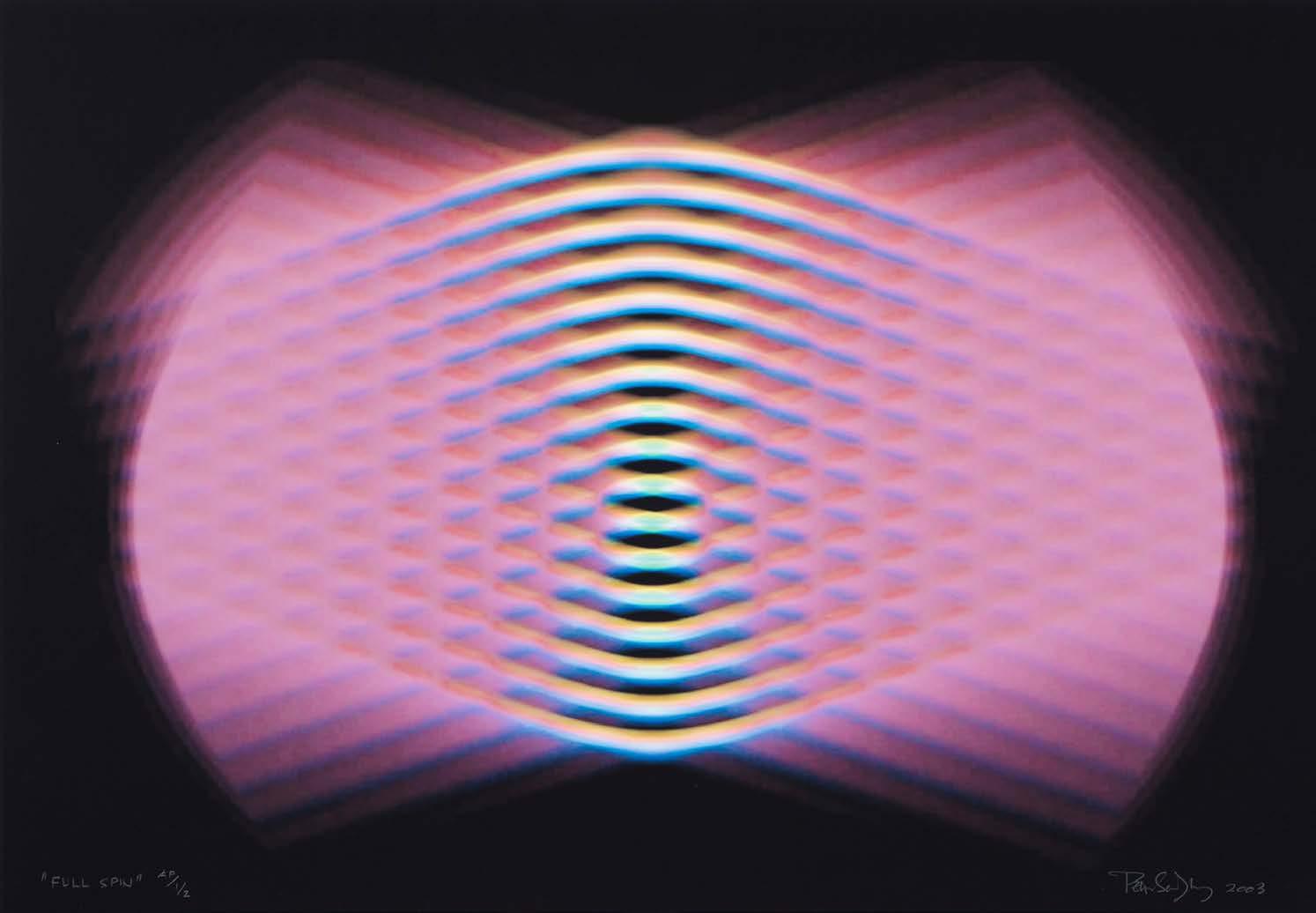

Inkjet cybergraph

33 × 48 cm

Edition of 12

33 × 48 cm

Edition of 12

Peter Sedgley

Born in London, 1930

Studied Architecture and Building

Founder Member of Art Information Registry (AIR) and Space Provision Artistic Cultural and Education (SPACE)

DAAD stipendium, Berlin, 1971

Solo Exhibitions

1965 McRoberts and Tunnard Gallery, London

Howard Wise Gallery, New York

1966 McRoberts and Tunnard Gallery, London

Howard Wise Gallery, New York

Richard Feigen Gallery, Chicago

1968 Galerie Neuendorf, Hamburg

Kunstmarkt, Köln

Redfern Gallery, London

Galerie Reckermann, Kassel

1970 Trinity College, Dublin

1971 St. Paul’s School, London

Haus am Waldsee, Berlin

1972 Forum Kunst, Rottweil

Ikon Gallery, Birmingham

D.L.I Museum, Durham

Midland Group Gallery, Nottingham

Arnolfini Gallery, Bristol

1978 Akademie der Künste, Berlin

Galerie Tilly Haderek, Stuttgart

1979 Overbeckgesellschaft, Lübeck

1980 Redfern Gallery, London

Roundhouse, London

1981 Hendricks Gallery, Dublin

Project Gallery, Dublin

Galerie im Zentrum, Berlin

1982 Galerie Ferm, Malmö, Sweden

1983 Redfern Gallery, London

1984 Galerie Seestraße, Rapperswil, Switzerland

1985 Bede Gallery, Jarrow

Galerie Ferm, Malmö, Sweden

1986 Galerie Ferm, Malmö, Sweden

Galerie Blanche, Stockholm

1987 Stadsmuseum, Norrköping, Sweden

Grønningen, Copenhagen

1988 Museum in Gelsenkirchen

Kunstverein, Siegen

1989 Galerie Führ, Munich

Worthing Museum & Art Gallery, Sussex

1990 Galerie Ann Westin, Stockholm

1991 New York Hall of Science

1994 Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase College, New York

1997 The Czech Museum of Fine Arts, Prague

2000 Austin/Desmond Fine Art, London in association with Kelly Ross

2004 Austin/Desmond Fine Art, London

2008 Kelly Ross Fine Art, Blandford Forum, Dorset

2009 Redfern Gallery, London

2014 Diehl, Berlin

Diehl Cube, Berlin

1964 Seven 64, McRoberts and Tunnard Gallery, London

1965 Le Salon des Réalitiés Nouvelles, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

The Responsive Eye, Museum of Modern Art, New York

Art Today, Albright Knox Gallery, Buffalo, NY, USA

1966 Ten 66, McRoberts and Tunnard Gallery, London

Kinetic Art, Herbert Art Gallery, Coventry

Aspects of New British Art, British Council touring exhibition of New Zealand and Australia

The 9th Mainichi International Biennale, Tokyo

Prize winner of the Education Minister’s Award

1968 Klub Konkretistu, CSSR

British Drawing Exhibition, Museum of Modern Art, New York (and tour of USA)

Galerie Milano Print Shop, Milan

Power Bequest Exhibition, Sydney, Australia

Macys Festival of Great Britain, New York

Nuevas Tendencias, Museum of Modern Art, Mexico City

Public Eye, Kunsthaus, Hamburg

1969 Gallery Onnasch, Berlin

Nantenshi Gallery, Tokyo

1970 Human Presence, Camden Arts Centre, London

Contemporary British Art, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

1971 SPACE Art Exhibition: London Now in Berlin, Berlin Festival

1972 Group New Music, Akademie der Künste, Berlin

Berlin Scene, Gallerie Haus, London

AIR Exhibition, Glasgow and Edinburgh

1973 Kinetic Art Exhibition, Swansea, and Edinburgh

30 Internationale Künstler in Berlin, Beethovenhalle, Bonn

British artists’ prints of the Sixties, British Council touring show

1975 Britanniasta 75, Helsinki Taidenhalli, Alvar

Aalto Museo, Tampere

1976 Bild-Raum-Klang, Bonn, Stuttgart, Berlin

Künstlerbund-Exhibition, Nationalgalerie, Berlin

1977 Berlin Now, New York

Group Systema, Helsinki (and tour of Finland)

British Painting 1952-77, The Royal Academy of Arts, London

Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, Berlin

A Silver Jubilee Exhibition of Contemporary British Painting, Tate Gallery, London

11 Internationale Künsterler, Forum fur Kulturaustausch, Bonn

1978 Konstruktive Tendenzen, Galerie Christl, Stockholm

Kunst des 20 Jahrhunderts aus Berliner Privatbesitz, Academie der Künste

1982 Spielraum-Raumspiel Exhibition, Alte Oper, Frankfurt

1986 42nd Venice Biennale, Art & Science

1987 Grønningen Group, Annual Exhibition, Copenhagen (and 1988, 1990, 1993)

1992 Arts Council of Great Britain 1960s Collection, Festive Hall, London (touring)

Berlin Konkret, House of Art, Brno National Gallery, Bratislava, Slovakia

Ready Steady Go, Royal Festival Hall, London

1993 The Sixties Art Scene in London, Barbican Art Centre, London

Celebrating Sculpture, Chelsea Arts Club, London

1998 Charged Light, Royal Academy, Stockholm (Cultural City of Europe 1998)

1999 Light and Visual Text, Erfurt & Weimer (Cultural City of Europe 1999)

2003 Editions Alecto: A Fury for Prints, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester (touring)

Bankside Gallery, London

2003 City Art Centre, Edinburgh

2004 Art & the Sixties, This was Tomorrow, Tate Britain

2005 Summer of Love: Art of the Psychedelic Era, Tate, Liverpool, (touring) Kunsthalle Schirn, Frankfurt,Kunsthalle Wien, Kunsthalle, Vienna

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, USA

2007 Luminaries & Visionaries, Kinetica Museum, London

‘In Flux’ A State of Being, Kinetica ar 100% Design, London

Optic Nerve: Perceptual Art of the 1960s, Columbus Museum of Art, USA

Towards a Rational Aesthetic, Osborne Samuel, London

The State of the World, Centro de Arte Moderna, Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Museu Municipal de Tavira, Portugal

2008 Traces du Sacré, Centre Pompidou, Paris

2011 Molekulare Ästhetik, ZKM, Center for Art and Media, Karlsruhe

2013 Dynamo - Un siècle de lumière et de mouvement dans l’art 1913-2013, Grand Palais, Paris

2016 Electronic Superhighway (2016-1966), Whitechapel Gallery, London

2017 Kaleidoscope: Colour and Sequence in 1960s British Art, Arts Council Collection touring show of the UK The Art of Perception – From Seurat to Riley, Compton Verney, Warwick

2018 Action <-> Reaction: 100 Years of Kinetic Art, Kunsthal Rotterdam

2021-24 Light: Works from Tate’s Collection, (touring exhibition) – Museum of Art Pudong, Shanghai, China; The Seoul Museum of Art (SeMA), South Korea; Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI), Melbourne; Auckland Art Gallery Toi O Tāmaki, Auckland, New Zealand; The National Art Center, Tokyo and Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka, Japan

Projects and Collaborations

1972 Donaueschinger Musiktage Light Sounds – Sound Light in collaboration with the composer York Höller

1973 Light Ballet, Place Gambetta, Town Festival, Bordeaux

1974 Chain Reaction, Audio Visual Concert with the composer Mario Bertoncini, Haus am Waldsee, Berlin

1976 Labyrinth, Audio Visual Environment in collaboration with the sculptor Rudolf Valenta, Berlin and Bonn

1978/97 Windforms (wind-light-sound-tower):-

Munich Cultural Week 1978

International Art Congress, Stuttgart 1978

Alte Oper Frankfurt am Main 1982

Academy Charlottenburg, Copenhagen, (Cultural City of Europe) 1996

Prague Spring Festival 1997

1979 SoundsScreen, Flute: E Blum Audio-Visual-Performance opening, Sprengel Museum, Hannover Futurism-Dadaism, Studio K 19, Berlin

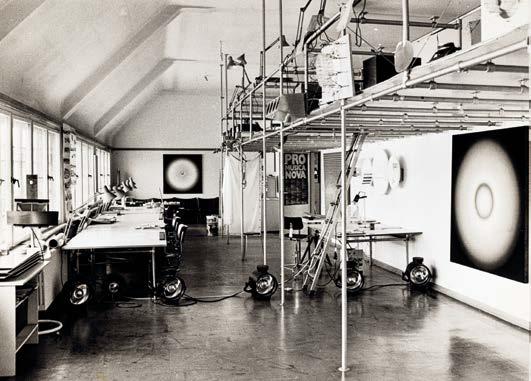

1980 Reflections, Pro Musica Nova, Bremen with Eberhard Blum

1986 Les Evénements du Neuf, Bauhaus-Montreal

Bayerische Vereinsbank, Berlin, British Embassy, Berlin Conference Centre, Dubai, UAE

Hiltrup Community Centre, Münster

Haubrich Forum, Neumarkt, Köln

Kastrup Airport, Copenhagen

Landeskriminalamt, Berlin

Museum of Science & Industry, Chicago

Ofgem Foyer, Millbank, London

Pimlico Underground Station for the Tate Gallery, London

St. David’s Link Sculpture, Cardiff

Technical University, Stuttgart

Welcome Wing, Science Museum, London

Werner-von-Siemens-Schule, Berlin

Universitätsklinikum Rudolf Virchow, Berlin

Work in Public Collections

Arts Council Collection, London

Arts Council of Northern Ireland

Ateneum Art Museum, Helsinki

Berlinische Galerie, Berlin

Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery

Bristol Museum & Art Gallery

British Council Collection

Chase Manhattan Bank, USA

Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon

Government Art Collection, UK

Kinetica Museum, London

Leicester Education Authority

L.O. Schulen Helsingør, Denmark

Manchester City Art Gallery

Museum of Modern Art, Prague

Nagasaki Art Museum, Japan

Neuberger, Museum of Art, Purchase College , New York, USA

Peter Stuyvesant Collection

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

Saint Louis Art Museum, USA

Schwedische Nationalsammlung, Stockholm

Skissernas Museum, Lund, Sweden

Städtisches Museum, Gelsenkirchen Tate, London

University of Lancaster, Lancaster

University of Warwick Art Collection, Warwick

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Walker Art Centre, Minneapolis, USA

The Winnipeg Art Gallery, Canada Wolverhampton Art Gallery, Wolverhampton

Peter and Inge at the Centre Pompidou, Paris with Light Pulse 1968 (Exhibition – Traces du sacré: Les langages de l’art) 2008

Peter Sedgley and The Redfern Gallery would like to thank Kathleen Sedgley, Hugh Gilbert, Nicolaas Kaptein and Kelly Ross for their help and support.

Published to coincide with the exhibition

6 to 30 November 2024

Exhibition conceived in dialogue with Dr Omar Kholeif.

© The artist, the authors and The Redfern Gallery, London

Editors: Richard Gault and Dr Omar Kholeif

Photography of artworks: Alex Fox

Design: Graham Rees Design Print: The Five Castles Press

Published by The Redfern Gallery, London 2024 ISBN: 978-0-948460-90-6

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying recording or any other information storage or retrieval system without prior permission in writing from the gallery.

front and back cover Energy, 1980 (detail)

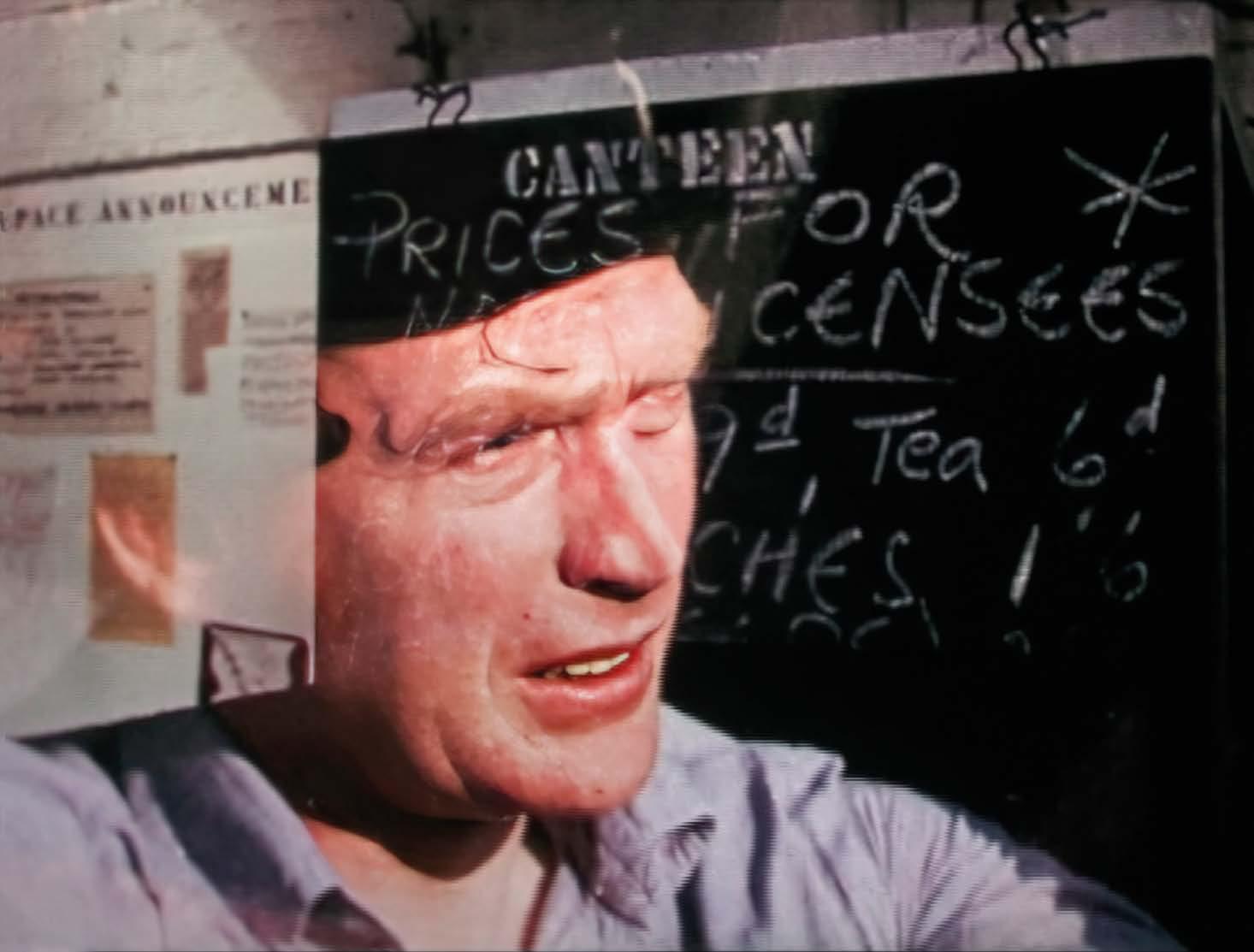

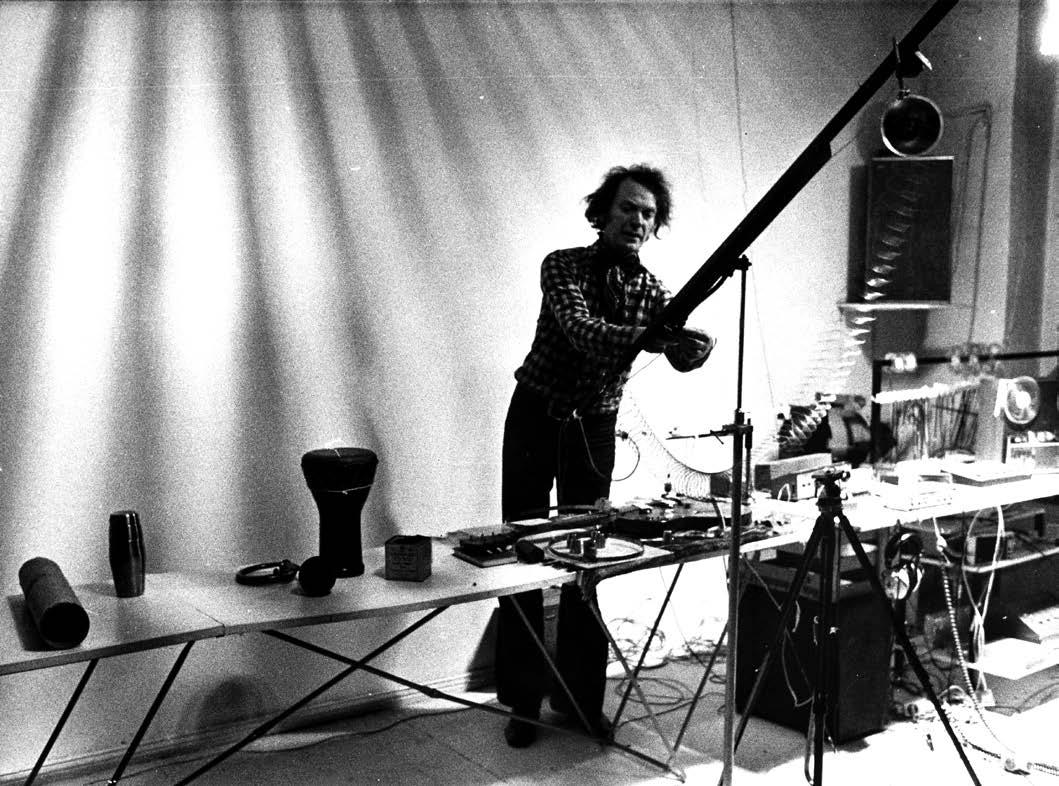

inside front cover

Peter Sedgley at SPACE, St Katharine Docks, 1970 (still from SPACE film, 1970)

© SPACE

inside back cover

At a party in the garden at Schloss Bellevue, Berlin, c.1974. Photo by Ingeborg Lommatzsch

20 Cork Street, London W1S 3HL

+44 (0)20 7734 1732

info@redfern-gallery.com redfern-gallery.com Mon-Fri 11am to 5:30pm Sat 11am to 2pm