Thinking and Feeling: Mark Lancaster Paintings, 1960-1990

Ian MasseyThough Mark Lancaster (1938-2021) has by now largely slipped from view, as both an artist and social figure his name is wedded to the mythology of the 1960s and 1970s, his story interwoven with those of some of the most renowned cultural figures of the era. For he inhabited many worlds, and the extensive list of his friends and collaborators includes the artists Richard Hamilton, David Hockney, Jasper Johns and Andy Warhol, and the dancer and choreographer Merce Cunningham. Active as an artist for three decades, Lancaster worked most often in series, each group of paintings informed, conceptually and stylistically, by those that preceded them. At first unremittingly abstract, his work evolved gradually, and his later paintings combined both abstract and figurative elements.

Born in Holmfirth, Yorkshire in May 1938, on leaving school Lancaster joined his family’s woollen textile business for five years before making the decision to study art. Then, at the age of twenty-three, he enrolled on the Fine Art degree course at King’s College, Newcastle-upon-Tyne. Its teaching staff included Victor Pasmore, Kenneth Rowntree, and Richard Hamilton, who was to be a crucial figure in Lancaster’s development. At Newcastle he established lifelong friendships with several students, among them the future Roxy Music frontman Bryan Ferry, and the artist Stephen Buckley. Charismatic and stylish, and slightly older than the other students,

he was, in Ferry’s words: ‘the coolest of the cool, after Richard [Hamilton].’ 1

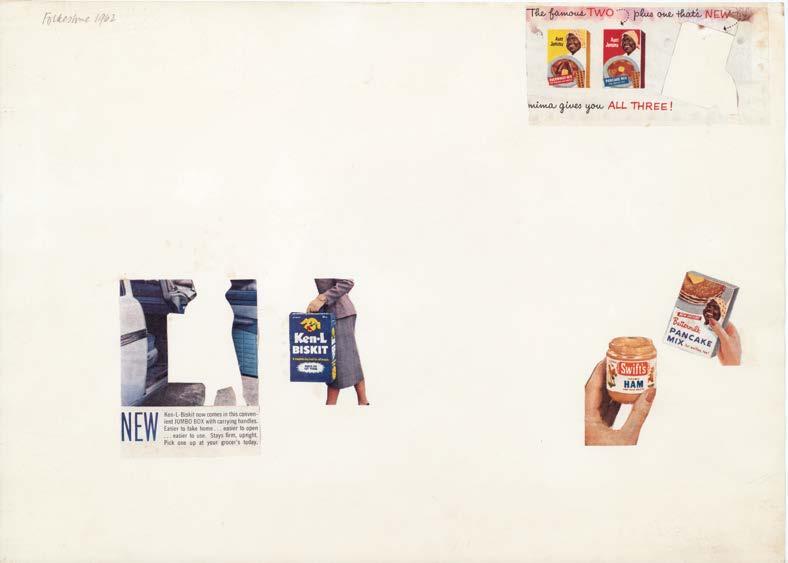

As a student Lancaster became fascinated by commercial print processes, by relationships of image and type, and the intensity of lithographic colour. Through discussions with Hamilton, he gained a deeper understanding of the semantics of graphic design and its deployment within popular culture. In 1962 he made a group of photomontages inscribed ‘Folkestone 1962’, using snippets of photographs of food packaging culled from American magazines, carefully cut out and glued onto sheets of white paper. One senses the allure he found in such images, as small tokens of a more glamorous existence on the other side of the Atlantic. Lancaster’s Three Studies for Betty Crocker Painting (1962-63) is based on similar material, its two fragmentary portraits taken from an illustration of the eponymous (and fictitious) American cook used in advertising for the famous brand of cake mixes. Later, Lancaster was to utilise the ephemera of American mass culture far more opaquely in devising an entirely abstract visual language. In this, the work of Richard Smith, a visiting lecturer at Newcastle, proved a vital source of inspiration. The two became friends, and they doubtless engaged in discussions about their mutual interests in painting and popular culture. Smith, six years or so his senior, was to prove a supportive champion of Lancaster’s work.

In 1964 Lancaster travelled to New York to research his degree dissertation on the photographer Alfred Stieglitz. The visit proved life-changing, for, as he later wrote:

I arrived in New York for the first time on the Fourth of July 1964. The following day I made my first telephone call, to the number listed under Andy Warhol in the phone book. A female voice answered ‘Andy Warhol’. I was puzzled. It was eventually revealed that this was something called an Answering Service. I left a message to the effect that I was a student of Richard Hamilton’s, and that Richard, who had met Andy Warhol at the [Marcel] Duchamp exhibition in Pasadena the previous year, had suggested I call. The next morning my phone rang for the first time. ‘This is Andy Warhol’; the voice, though never heard before, was unmistakably his. He invited me to ‘come by the Factory’ that afternoon. ‘We’re making a movie’.2

Only a matter of days later, Lancaster found himself assisting Warhol in his studio at the Factory on East 47th Street, stretching silk-screened canvases from the artist’s ‘Flower’ and ‘Most Wanted Men’ series, and was drafted in to appear in two films,

including ‘Kiss’, in which he and Warhol’s assistant Gerard Malanga are locked mouth-to-mouth in a three-minute sequence. And crucially, Warhol introduced Lancaster to Henry Geldzhaler, curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Fine Art, who in turn introduced him to artists including Frank Stella, Ellsworth Kelly, and Jasper Johns.

The first of Newcastle’s art students to visit America, on his return for the new term in September Lancaster was greeted as an emissary bearing firsthand knowledge of the white heat of New York’s art scene. Success came soon after completion of his degree. Following his inclusion in The Young Contemporaries exhibition of work by recent art graduates in 1965, he was offered a solo show by the Rowan Gallery in London; it opened that November. Of the sixteen paintings exhibited, many were based on ephemera acquired in New York, such as a restaurant chain’s printed paper napkins, and postcards depicting more than one image. Taking his cue from their grids and patterns, Lancaster developed compositions on sheets of graph paper, in precise pencil lines, with colours indicated in crayon or pastel. The paintings in the Rowan Gallery show all date from 1965, with several titled from American sources; the department store Bloomingdales for

instance; and Gore, after Lesley Gore, singer of ‘It’s My Party’ (a pop song heard during Lancaster’s visits to Warhol’s studio). Some paintings were formed of two or more joined canvases, among them Boondocks, its tonal palette not dissimilar to that of an oil on board landscape that Lancaster made in 1960. (Incidentally, ‘boondocks’ is an American colloquialism for rough or isolated country). There was also Yorkshire, formed of three rectangular canvases of equal dimensions, two placed horizontally, one vertically. While each has the same pattern of parallel tapering bands, they are painted in subtly different greens, and the configuration of the final work induces a sense both of optical vibrancy and expansive space; space that might extend beyond the work’s physical parameters. 3

Lancaster knew from Warhol the power of repetition and ostensible detachment, and although the formal austerity of this early work may appear cerebral and noncommittal, it carries an underlying weight. This was noted in Norbert Lynton’s review of the Rowan Gallery show, when, having described the paintings as having, ‘all the neat suavity that goes with 1965’, he went on to write:

I know from Lancaster himself how poignantly certain colours and arrangements represent for him recent experiences, but it takes time for the emotional content to come through. 4

This theme, of the encodification of personal meaning, was made explicit years later, in a comment Lancaster made in an interview:

the grid... presented itself to me as a way to make an abstract painting that was also packed with other emotional and hidden meanings. 5

The three Americans who exerted the greatest artistic influence on Lancaster were Warhol, Johns, and Stella. Of the latter, Stella’s shaped paintings of 1962-64 were especially important. Lancaster is likely to have read a critique of Stella’s work of that period by the American art historian Michael Fried, in which he describes: ‘a new mode of pictorial structure based on the shape, rather than the flatness of the support.’ 6 In the same essay Fried refers to ‘depicted shape’ and ‘literal shape’; that is, to the painted shape, and that of the canvas itself. And this

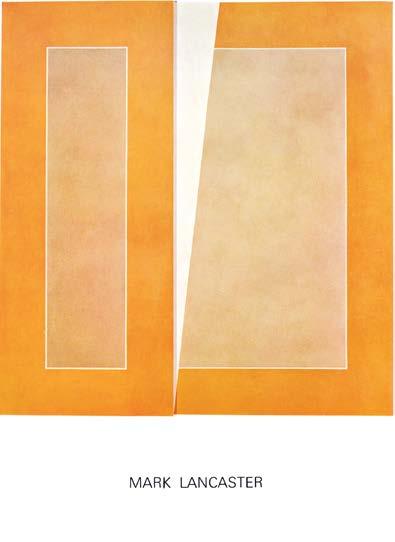

distinction is pertinent to Lancaster’s paintings of the 1960s, those in which a flat impersonality of surface is essential in work whose main preoccupation lies in perceptual relationships of shape and edge. This became further apparent in Lancaster’s second show at the Rowan Gallery in 1967, in paintings such as Easter Monday, with its two canvases set at different levels, that on the left protruding slightly against the steeply angled white shard of its adjoining partner.

In 1968 Lancaster was invited to become the first Artist in Residence at King’s College, Cambridge. The residency – which was extended to a second year – proved highly productive, the artist’s work becoming increasingly complex and expressive, in both form and colour. The change arose in no small part from a change in technique, namely the application of paint with a squeegee, an implement usually associated with silkscreen printing, of which Lancaster had first-hand knowledge from Warhol’s studio. It allowed for a wider tonal range, resulting from both the amount of pigment employed and the degrees of pressure used when spreading it

Announcement card for Lancaster's second show at the Rowan Gallery, June/July 1967, showing his Easter Monday, liquitex on two adjoined canvases, 173 x 213 cm

Mark Lancaster, with his painting Story (1965), Powis Terrace, Notting Hill, August 1965. The photographs are thought to have been taken at David Hockney’s flat. Lancaster lived in London for much of the 1960s; there his social circle included Hockney, Celia Birtwell, Stephen Buckley, Ossie Clark, Keith Milow, Patrick Procktor, and Peter Schlesinger.

Story was included in Lancaster’s 1965 show at the Rowan Gallery.

Photography by Chris Morphet

across the nub of the canvas. Lancaster began to superimpose one grid over another, as in the drawing Cambridge Michaelmas Study (1969), in which a grid of sixteen squares is overlaid by one of equal proportions set at forty-five degrees. A further exploration of spatial complexity – and of colour interactions – can be found in two canvases from the following year, Cambridge Lent II, and Founder’s Orbit, in which Lancaster’s experimental processes have also impacted on his considerations of form. In the first of these, having laid down strips of tape to mask the edges of his pattern of overlapping diagonals, he has dragged paint over the canvas in such a way that pressure on its underlying stretcher and cross bar has marked out four squares. In both paintings little crosses of raw canvas map points of intersection and shifts of direction.

By 1970 Lancaster’s success was consolidated, his work acquired by many collections, including the

Tate Gallery and New York’s Museum of Modern Art. He had returned often to America since his first visit, and in 1972 moved to live in New York. There, he continued to paint while also working as private secretary to Jasper Johns, a role that continued for over ten years, during which the two were to form an intimate relationship. He continued to exhibit, showing with Betty Parsons Gallery in New York in both 1972 and 1974. Work produced during this period includes the 14th Street Series, titled after the location of his studio, from which he had a view of the Empire State Building. There is in this series a return to a clear delineation of linear structures, though now more complex, and animated with roughly textured swathes of pigment.

The underlying lyricism that exists in much of Lancaster’s work is amplified in a series of canvases from 1974 that combine a palette of warm and cold greys with colours from which their titles are

Signed, titled and dated verso

Founders Orbit 1970

Oil on canvas

111.7 × 111.7 cm

taken; among them are Violet and Green. In each, a sequence of squares or rectangles act as containers for expansive sweeps and flurries of brush-drawn paint, a handling that owes something to Jasper Johns out of Cezanne. The hue of untreated canvas is also integral, for Lancaster delighted in its shades and tactility (one is reminded of his early experience in textile production). One might usefully compare the gestural freedom in these pictures, with their shifts of direction and emphasis, to Lancaster’s designs for Merce Cunningham, which began with Sounddance (1975). Lancaster had an instinctive understanding of stage lighting, and brought his refined sensibility to bear when selecting colours for costumes and sets, in which, as John Russell has written:

‘[Lancaster] achieved, over and over again, the kind of limpidity that passes unnoticed. A great deal happened at his behest, but for most of the

audience there was “nothing to it”: no splashy scenery, no costume designs that aimed to put Bakst in the shade, no fancy lighting. The spectacle had no detachable elements, and it was as ego-free as any we are likely to see.’ 7

Intriguingly, there is painting from 1975, titled NAME Costume, to which Lancaster attached a section of sleeve from a dancer’s costume, to dangle loosely over its top edge.

The stylistic bridge between the Cambridge canvases and those of the mid-seventies is found in paintings such as Untitled (August ’73), with its architectural blocks of greys, blacks, and yellows. As much as anything, it reads as a painting about process, combining as it does a range of techniques, including applying paint through a silkscreen to form gradated panels in which greys segue into pale yellows.

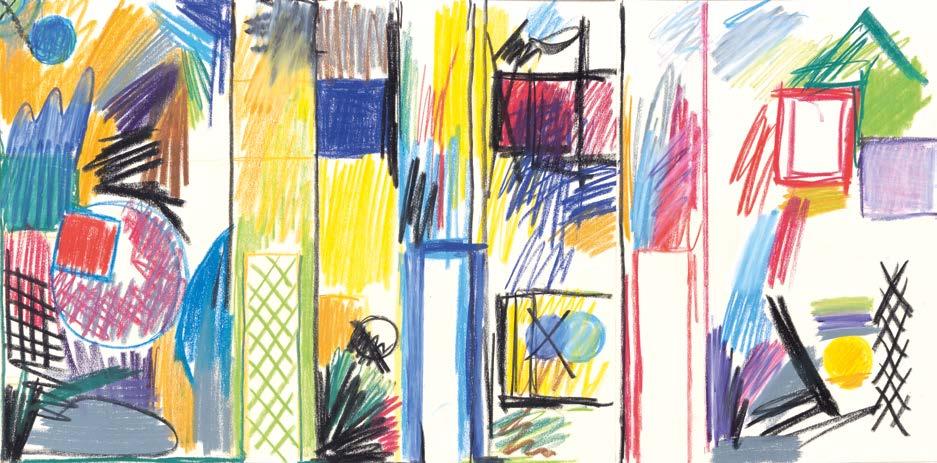

Lancaster first became interested in the Bloomsbury Group in 1958, when Richard Morphet introduced him to Virginia Woolf’s A Writer’s Diary, and to the work of artists Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell. In the following year, the Tate’s retrospective of Grant’s work was, as Lancaster subsequently wrote: ‘a great experience, and influence, in the year in which I decided that I wanted to be a painter.’ 8 He and Grant met and became friendly during his Cambridge residency, and he made visits to Grant at his home, Charleston, the farmhouse in the Sussex downs he had shared with Bell since 1916 (she had died in 1961). Woolf’s complete diary was published in 197778 and, following Grant’s death in 1978, in New York Lancaster made three paintings with the intention of expressing his readings of the diaries in abstract terms. They are each titled The Diary of Virginia Woolf, with a prefix of Volume I, II or III. Their shared starting point is in the decorative devices from Grant’s dust wrapper designs for the Hogarth Press editions of Woolf’s diaries; for example, the cross-hatched rectangle from the volumes’ spines is common to all three, as are the circles found in decorative work by both Grant and Bell. There followed Charleston, a six by twelve-foot triptych, made in tribute to Grant, and using the same motifs as those of the three Diary canvases. A drawing in coloured pastel shows

Lancaster plotting its composition; a sequence of vertical rectangles, anchored with blocky squares, and animated with floating roundels and passages of broad gestural brushwork. While sections of the drawing are close to those of the finished triptych, it is clear that a degree of improvisation was involved as work progressed. Impressively sustained, its diverse application includes areas of gloopy impasto, incidental drips and scurries, and lines scratched into wet pigment with the handle-point of brush. At its centre is a rendition of Grant’s autograph, ‘dg’, blotted onto the canvas in reverse, as though mirrored.

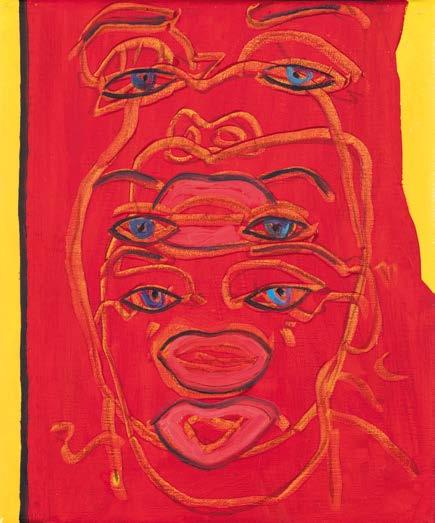

Lancaster owned a portrait that Grant made of Vanessa Bell (c.1918), from which he painted a series of eight variations in 1980. They share with Charleston a vigorous handling and an intense palette, in which the red of the paisley-patterned dress Bell wears in Grant’s painting (which includes collaged pieces of fabric from the actually dress) is dramatically heightened. In the third and last of these variations – the latter reminiscent of the designs of the Omega Workshops – the degrees of abstraction render the figure unrecognisable. In an explanatory insight into the formal configurations of

his Vanessa Bell canvases, Lancaster wrote of how they were influenced by Picasso’s paintings based on Velasquez’s Las Meninas and Delacroix’s Women of Algiers, seen at the artist’s New York retrospective in 1980. 9

One might wonder at the apparent incongruity between the Bloomsbury artists and the Americans who exerted an influence on Lancaster earlier in his career. But his attachment to Bloomsbury was clearly fundamental to him, not least because the 1959 Grant retrospective had been instrumental in confirming the then twenty-one-year-old’s decision to become a painter. Also, as Richard Shone has noted:

Lancaster’s preoccupation with the Bloomsbury style reflects one side of his cultural sympathies at a general level and a specific interest in its manipulation of a few simple forms for maximum and often subtle effect – something found throughout Lancaster’s work. 10

One might also add how relevant Lancaster’s Bloomsbury-inspired paintings appear in the context of the period in which they were made, when painting’s relevance was reclaimed with the seminal

‘A New Spirit in Painting’ at the Royal Academy in 1981; a show that included his friends Hockney, Stella and Warhol.

In an echo of his painted tribute to Duncan Grant, the day after Andy Warhol died in February 1987, Lancaster painted a small canvas, a copy of a 1964 Warhol portrait of Marlilyn Monroe. Now living in Kent, he first intended this canvas as a private gesture of homage, but in fact it was to set in train the production over the next year of 180 paintings. All of the same dimensions, the series are permutations on Warhol’s Marilyn, its components deconstructed and rearranged, occasionally sampling motifs derived from artists such as Cezanne, Matisse, and Picabia. In some a profiled face appears; that of Warhol, or perhaps of Lancaster’s own. Over a hundred of the paintings were exhibited as Post-Warhol Souvenirs at the Mayor Rowan Gallery in London, soon after the first anniversary of the American artist’s death.

Lancaster's final series of paintings dates from 1990; they were shown at the Mayor Rowan Gallery in London that autumn. In character, they are to some extent a continuation of the playful experimentalism of his Post-Warhol Souvenirs. Many allude to art history, and to the act of picture making, with pictorial puns, spatial ambiguities, and hints at trompe l'oeil. There are references to Mondrian, Duncan Grant, Cezanne, and Johns, to Lancaster’s own back catalogue of imagery and personal history. Viewed now, as the artist's final works, they read as a coda, at once knowing, ironic, and elegiac.

In his later years Lancaster lived with his husband in Miami, where he had a show of some earlier paintings in late 1993, the last during his lifetime. Ultimately it seems that his work with Johns, though rewarding, had disrupted his own career so that it became impossible to regain momentum. He worked again with Cunningham in 1991 and 1993, on what were to be his final creative projects. The distinctive body of work Lancaster made is now ripe for reappraisal, beginning with this survey, his first London exhibition in over thirty years.

Endnotes

1 Bryan Ferry, quoted in Michael Bracewell, Re-make/Remodel, Faber and Faber Ltd., 2007, p84.

2 Norbert Lynton, London Galleries, The Guardian, 20th November 1965.

3 The painting Yorkshire was later included in a group show at the Robert Fraser Gallery, London, in July 1967.

4 Norbert Lynton, London Galleries, The Guardian, 20th November 1965.

5 Interview with Gary Comenas, 2004: https://warholstars.org/ andywarhol/interview/mark/lancaster.html

6 Michael Fried, Shape as Form: Frank Stella’s New Paintings, Artforum, Vol. V, No. 3, November 1966. A somewhat revised version of Fried’s essay, dated July 1969, was published in Henry Geldzhaler, New York Painting and Sculpture: 19401970, Pall Mall Press, London, 1969, pp 403-425.

7 Norbert Lynton, London Galleries, The Guardian, 20th November 1965.

8 Mark Lancaster, Variations and Tributes, The Charleston Magazine, Spring/Summer 1997, Issue 15, The Charleston Trust, pp16-21.

9 Ibid.

10 Richard Shone, review of Mark Lancaster’s show at the Rowan Gallery, London, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 122, No. 928, July 1980, pp517-518. .

Zapruder Study I

Oil on board

30.5 × 40.6 cm

Three works from the generically titled Zapruder series. Lancaster made the first of his Zapruder works in 1967. The series includes large canvases, drawings, lithographs, and smaller paintings such as the three undated ones shown here. All are based on stills from an amateur film showing the assassination of President Kennedy, made by Abraham Zapruder in Dallas in November 1963. The footage was printed, frameby-frame, in Life magazine. Lancaster professed himself struck by these images and their emotional content. Each work in his Zapruder series is formed of uniform rectangles set within a grid, echoing those of the sequential frames printed in Life magazine. An example of the Zapruder canvases is in the British Council collection.

14th Street Study 1972

Aquatec on canvas

14th Street Study D (Blue and Yellow) 1972

Aquatec on canvas

14th Street Series No.12 1972

Aquatec on canvas

80 × 127.5 cm

Signed, titled and dated verso

14th Street Series No. 10 1972

Signed, titled and dated verso

Untitled c.1972-3

Oil on canvas

38 × 55.5 cm

Untitled c.1972-3

Oil on canvas

40.5 × 61 cm

Untitled (August ‘73) 1973

‘The allure and enduring quality of Marilyn Monroe’s image, as fixed by Warhol, may be too strong for it to be stripped away more than momentarily. The persistence of Lancaster’s unmaskings, however, serves well as a reminder of the complex motivations, multiple readings and interconnections prompted by a single image of such apparent simplicity.’

Marilyn Sept 9-11 1987 1987

Marilyn Jan 16 1988 (Painter and Model) 1988

Oil on canvas 30.5 × 25.5 cm

Marilyn Jan 20-28 1988 1988

Oil on canvas 30.5 × 25.5 cm

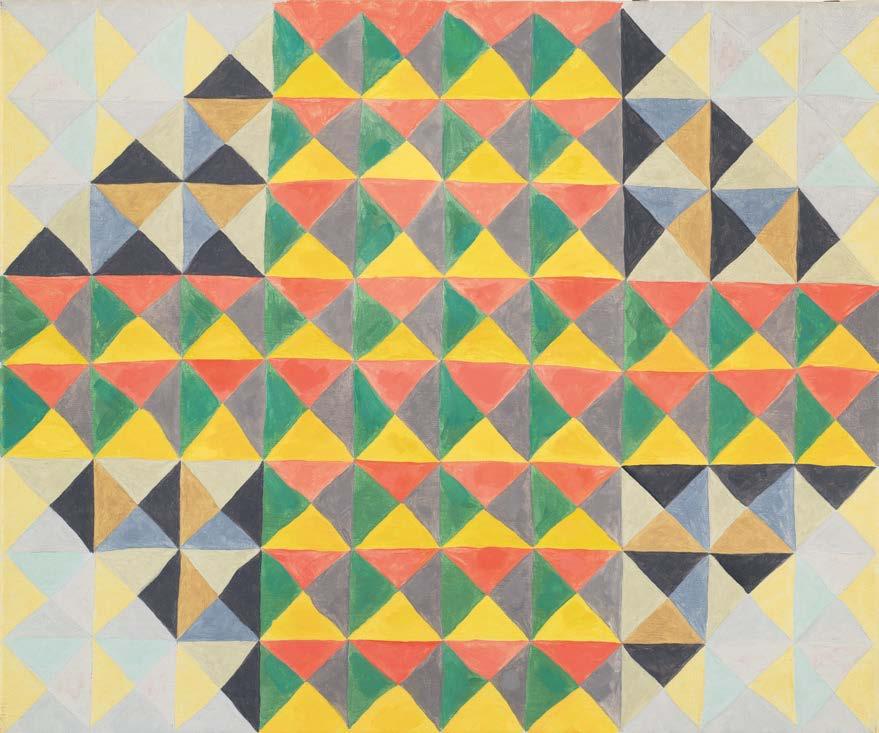

Harlequinade 1990

Oil on canvas

50 × 60 cm

Signed, titled and dated verso

Portrait 1990

Oil on canvas 50 × 60.3 cm

Signed, titled and dated verso

Night Walk I 1990

Many thanks to the following people for assistance in developing this catalogue and exhibition:

David Bolger

James Gould

Chris Morphet

Richard Morphet

Mike Shepherd

Catalogue © The Redfern Gallery, 2023

Works © The Estate of Mark Lancaster

Essay © Dr Ian Massey

Photography of Works: Alex Fox

Design: Graham Rees Design

Print: Gomer Press

Published by The Redfern Gallery, London 2023

ISBN: 978-0-948460-97-5

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying recording or any other information storage or retrieval system without prior permission in writing from the gallery.

Cover: Charleston, 1980 (detail), illustrated in full pp.52-53

Frontispiece:

Mark Lancaster with art dealer Robert Fraser and an unidentified woman, the Rowan Gallery, London, November 1965.

Photograph: Chris Morphet.

Opposite:

Mark Lancaster in Newcastle c.1962

20 Cork Street London W1S 3HL

+44 (0)20 7734 1732

info@redfern-gallery.com

redfern-gallery.com

Untitled c.1965

Acrylic on canvas 24.8 × 24.8 cm