The Victorian Association for Gifted and Talented Children

Volume 34, No.1 2023

Managing Expectations of Giftedness and Talent

• Social Coping Strategies for Honors Students

• Expectations and Gifted Children

• Worried and Watchful: 7 Hacks for Helping Kids with ADHD Manage Anxiety

• Managing Expectations of Giftedness and Talent

Volume 34, No.1 2023

VISION, VOLUME 34 NO.1 2023 © 2023 Victorian Association for Gifted and Talented Children 2/3 Wellington Street, Kew, Victoria, 3101 CONNECT WITH US www.FaceBook.com/VAGTC Twitter @VicAGTC

SUBSCRIBE. BECOME A MEMBER www.VAGTC.org.au

EDITORIAL, ART & PRODUCTION TEAM

VAGTC Committee Members: Karen Glauser-Edwards and Laura Wilcox. COVER DESIGN Mariko Francis

DOCUMENT LAYOUT FOR PRINTING

Douthat Design & Print | info@douthatdesignprint.com

MANY THANKS TO THIS ISSUE’S CONTRIBUTORS

The most amazing people volunteered to make this issue what it is.

Much gratitude to: Eleni, Mary, Aarav, Angelique, Alannah, Julia, Emily, Victoria, Ksenia, Bianca, Kathy Harrison, Angie L. Miller, Stewart Milner, Sharon Saline, Marisa Soto-Harrison, Matthew J. Zakreski, Victoria Poulos, Natalie Dickson, Joanne Manoussakis and Laura Wilcox

For advertising inquiries and submission guidelines please visit www.VAGTC.org.au/Vision.

VISION Magazine welcomes contributions from members and students and invite student submissions of artwork, photographs, poetry, or short stories. Best-practices, re fl ections and educator-submitted reviews and articles are also welcome.

Copyright. The Victorian Association for Gifted and Talented Children (VAGTC) 2023 All rights reserved. VISION is published by the Victorian Association for Gifted and Talented Children (VAGTC) in two volumes each year and distributed to all VAGTC membership subscribers. All material in VISION is wholly copyright (unless otherwise stated via CC license and reproduction without the written permission of VAGTC is strictly forbidden. Neither this publication nor its contents constitute an explicit endorsement by the VAGTC of the products or services mentioned in advertising or editorial content. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, VAGTC shall not have any liability for errors or omissions. We’ve done our best to acknowledge all images used in this publication. In some instances images have been provided to us by those who appear editorially and we have their permission in each case to use the images. This publication contains links to websites at domains other than www.VAGTC.org.au. Such sites are controlled or produced by third parties. Except as indicated, we do not control,endorse, sponsor or approve any such websites or any content on them, nor do we provide any warranty or take any responsibility for any aspect of the content of this publication. We apologise if anything appears incorrectly. Please let us know and we will be sure to acknowledge it in the next issue.

1

VAGTC provides professional development for educators and support to parents through seminar presentations provided online or face to face. Seminar lengths vary from one hour to a full day, and cover a wide variety of topics. We aim to expand our offerings. Do you have expertise or resources that you would like to share? If you are interested in developing seminars and/or presenting, please send your expression of interest to info@vagtc.org.au. Remuneration is on an hourly basis.

Presenters should have:

• Minimum of 5 years experience in gifted education

• Post graduate qualifications in gifted education and/ or extensive experience working with gifted children

• Experience and ability in presenting at conferences/ seminars

• VIT registration

• ABN

School $137.50

Individual or Family $66

Student $49.50

Add $33 to any membership for annual AAEGT Journal subscription

B

www.vagtc.org.au

Membership Includes:

2 Editions of VISION

Resource Book

Select Seminars

Advocacy Resources

Consultation at Reduced Rates

VISION, Volume 34 No. 1 2023 2 VISION, Volume 34 No. 1

E C O M E A M E M B E R

VISION, Volume 34 No. 1 2023 Title Page Contributor Student Voice Sakura Flowers 4 Eleni Art Expression 9 Aarav Behind the Scenes of Being a Gifted Student 14 Angelique Lion 15 Alannah Collage 15 Julia Gifted Education Week Winners 16 Emily, Victoria, Ksenia Gaia 17 Bianca Expectations 19 Mary Welcome From the President 5 Kathy Harrison Resource Social Coping Strategies for Honors Students: 6 Angie L. Miller, Ph.D. Research Study Summary and Implications Managing Expectations of Giftedness and Talent 10 Stewart Milner Worried and Watchfull: 7 Hacks for 13 Sharon Saline Psy.D. Helping Kids with ADHD Manage Anxiety Expectations and Gifted Children 20 Marisa Soto-Harrison Ed.D. Managing Expectations of Giftedness and Talent 24 Matthew J. Zakreski Psy.D. Perspective & Reflection An Exceptional Exchange 17 Victoria Poulos What Teachers Say About Their Expectations for 18 Natalie Dickson Gifted and Talented Students Five Years On 23 Joanne Manoussakis Book Review Differentiation for Gifted Students in a 26 Laura Wilcox Secondary School: A Handbook for Teachers Contents 3

ADVERTISING IN VISION

We are exploring options for advertising in VISION in 2023. If you are interested in advertising in our publication, please contact us at: vision@vagtc.org.au

VISION, Volume 34 No. 1 2023

4

Sakura Flowers - by Eleni, Year 8, St John’s College, Preston

THE THEME OF MANAGING EXPECTATIONS OF GIFTEDNESS AND TALENT IS AN INTRIGUING ONE Whose expectations? What are the risks of inappropriate expectations? Is there such a thing as healthy expectations? What can I do to be part of the solution, part of a healthy support team for my students, my family and myself?

We are grateful to hear from a wide range of people including researchers, psychologists, teachers, parents, and students. As I read, I keep hearing the message that social relationships are vital to our wellbeing. The importance of social experiences and connections cannot be overemphasised.

There is a message for all of us here as we navigate the post-COVID world where anxiety has become the norm for so many of our gifted children, educators, and families. It is so encouraging to hear how we can be positive influences in the lives of those around us and transform worry to possibilities.

In this issue:

Dr Matt (Matthew Zakreski) offers relatable stories of expectations disappointed, but the empowering effect of asking the questions: “What if we modelled living life with no expectations for our gifted students? What if we treated every day as a blank slate, or even as a present?” Can we replace the use of the word ‘should’ with ‘could’ or ‘might’?

Stuart Milner tells us about a new school in Victoria – CHES – and the way in which they intentionally balance the expectations of academic, social challenges of childhood and adolescence and societal expectations. All whilst encouraging students to engage with topics and issues of current concern where they may choose to make contributions in the future. He emphasises that it is important that they are educated to lead fulfilling personal lives.

Angie Miller explores the relationships between personality traits, perfectionism, creativity, and social coping strategies. Dealing with social stigma associated with giftedness, students can adopt various strategies for navigating their interactions. This is related to their

Welcome Kathy Harrison From the President

personality and experience. She says that identifying these coping strategies can help educators and counsellors in advising their gifted students.

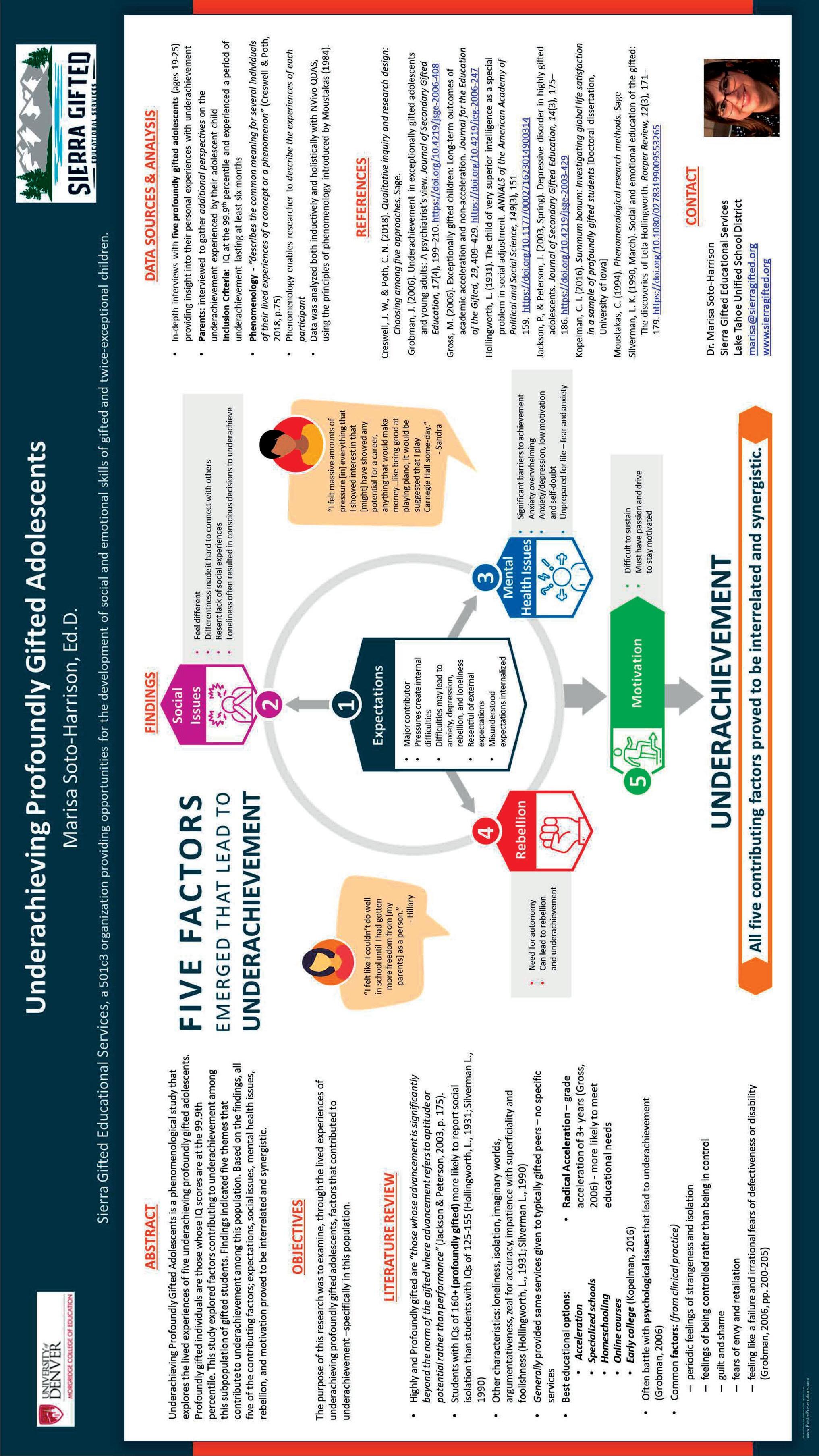

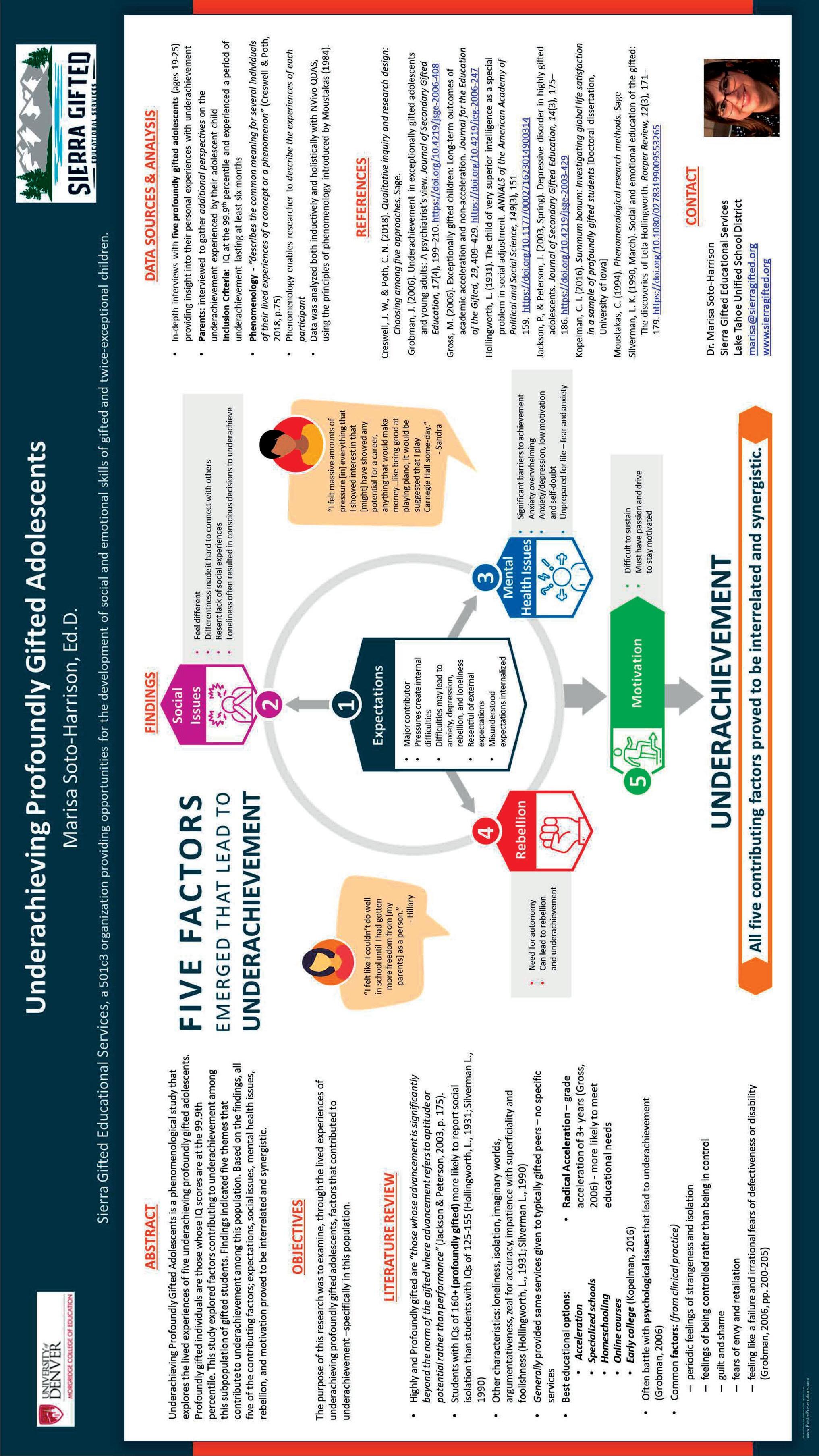

Factors contributing to underachievement are investigated by Marisa Soto-Harrison. She reports that expectations, whether real or perceived, emerged as the major contributor to underachievement in profoundly gifted. So how do we, as key supporters, encourage and provide reasonable and attainable expectations along with necessary support?

Sharon Saline encourages us to face anxiety head on, develop strategies to help kids manage their own anxiety, and discusses how to help them adopt such strategies.

“Without useful self-management strategies, and unable to access the internal resources they need, anxious kids freak out or refuse to do anything. But, when they learn how to talk back to worried, negative thinking and rely on past successes for confident choices in the present, they learn how to tolerate the discomfort of not knowing and they can accept the possibility of disappointment.”

The wisdom and self-reflection from parent Joanne and students Angelique, Mary and Aarav is inspiring. Balance in life, having outlets like art and sport, understanding the unique pressures on gifted students, and setting realistic goals all feature.

I hope that you enjoy reading this issue and can take some wisdom to share and enrich your lives, relationships, school communities and homes.

– Kathy Harrison VAGTC President

Call for Submissions - VISION Magazine Volume 34, No 2

Submissions are invited for our next edition on the theme of Enriching Gifted and Talented Minds

Due date October 31st, 2023.

VISION welcomes contributions on gifted education matters, including academic papers, reports on research, book reviews, perspectives from best practice and reflections. Some issues produced by VAGTC for VISION are thematic in nature. All written material should include a brief biographical note (approximately 30 words). Photographs and images should be original, copyrighted to the author, of suitable quality for print reproduction (no smaller than 300dpi) and emailed in JPEG format. Articles should be between 800-1500 words and be original work. All material submitted will be evaluated by the editors and outside referees where appropriate. The editors reserve the right to edit accepted works in order to fit the publication formatting and language. Email to: vision@vagtc.org.au

VISION, Volume 34 No. 1 2023

5

Social Coping Strategies for Honors Students: Research Study Summary and Implications

Angie L. Miller, Ph.D.

THE SENG JOURNAL: E XPLORING THE PSYCHOLOGY OF G IFTEDNESS (SENGJ) RECENTLY PUBLISHED AN ARTICLE EXPLORING THE RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN PERSONALITY TRAITS, PERFECTIONISM, CREATIVITY, AND SOCIAL COPING STRATEGIES WITHIN HONORS STUDENTS AT A UNIVERSITY IN THE US. This paper was authored by Dr. Angie Miller, a research scientist at the Indiana University Bloomington Center for Postsecondary Research. While the study uses a sample of postsecondary students, the findings shed light on our understanding of stigma, coping, and development for gifted individuals and how we might help gifted high school students transition into university settings and beyond.

Background Information

Previous research indicates that gifted individuals may feel different from other peers their age, and this difference can be exacerbated by the presence of a social stigma associated with giftedness (Cross et al., 2014). As a way of dealing with the social and emotional stress associated with stigma, gifted students acquire various strategies for navigating their environment and interactions with peers. These strategies can range from proactive to reactive, and from high visibility to invisibility. One existing measure of these strategies is the Social Coping Questionnaire (SCQ; Swiatek, 1995), which was initially developed with 10 to 17-year-olds participating in a gifted summer program.

It is important to address stigma for gifted students for several reasons, one main reason being that membership in a stigmatized group is associated with chronic stress and other lasting negative social and physical outcomes, with adverse effects on mental and physical health (Hatzenbuehler, 2013). If students have negative experiences in elementary, middle, or high school, they may potentially carry these memories and any resulting learned coping behaviors as they move into higher education settings, even though the specifics of the situations could differ.

Other psychological aspects have also been linked to the experience of giftedness and social coping. The “Big Five” or “Five-Factor Model of Personality” is one of the most widely known theories of basic personality traits (Costa & McCrae, 1992) and includes extroversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness/intellect. Some evidence demonstrates relationships between extraversion and the social coping strategies of humor, social interaction, and peer acceptance (Swiatek & Cross, 2007).

Perfectionism has also been studied in the context of giftedness, with one model of the construct presented in Hewitt and Flett’s (1991) Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (MPS). In this conceptualization, there are three different dimensions of perfectionism, which focus on setting unrealistic standards and expectations. Self-oriented perfectionism is related to unrealistic standards and expectations for oneself; socially prescribed perfectionism is the perception that others are placing unrealistic expectations or standards on oneself; and

other-oriented perfectionism involves holding unrealistic expectations and standards for others. The negative effects of perfectionism can be intensified by stress but can also be reduced with strong social connections.

Another construct often related to gifted students is creativity, generally described as any behavior or outcome that is both novel and appropriate (Runco & Jaeger, 2012). Some research provides support for a slight creative advantage for gifted individuals, across various age groups including postsecondary students. Empirical research suggests that engaging in creative activities can serve to alleviate stress, benefit mental health, and connects to the use of humor.

It is a fairly common practice in gifted education research to use samples of undergraduate honors students as a proxy for gifted young adults. Although not exactly the same as a K-12 gifted program experience, there are several similarities. Some distinguishable features of honors programs include: Unique and more academically demanding versions of general education courses, smaller class sizes for greater studentfaculty interaction, and more rigorous courses such as colloquia or seminars (Cognard-Black et al., 2017). Overall, the research suggests that participating in an honors college or program is related to various positive outcomes (Rinn & Plucker, 2019), but less is known about the potential negative experiences and how early social experiences for the gifted are contributing to their university experience.

Research Questions and Analyses

Given the importance of expanding research on social coping to postsecondary samples, the study addressed this by 1) exploring the factor structure of a previously established measure of social coping strategies and 2) looking at psychological and demographic constructs that predict the use of these established social coping strategies for honors college students. The second research question specifically focused on how demographics, personality traits, perfectionism, and creativity were able to positively or negatively predict the use of certain social coping strategies that were identified through the first research question.

The participants in the study were 432 students, all enrolled in the honors college of a Midwestern university in the United States, ranging in age from 17 to 23 years (M = 19.6, SD = 1.4). The students were highly representative of the demographics of the entire honors college population at this institution, and the vast majority (92%) reported having participated in gifted programming during elementary, middle, and/or high school, although the types of programming and amount of exposure varied widely (acceleration, enrichment, extracurricular, etc.). Students were invited to participate via email, which contained a link to an online survey (comprised of a battery of 12 instruments and demographic items). The measures that were used in this study were:

• Big Five Inventory (BFI-44; John et al., 1991): included subscales for neuroticism, extraversion, openness/intellect,

VISION, Volume 34 No. 1 2023 Keynote

Resource

6

agreeableness, and conscientiousness.

• Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (MPS; Hewitt & Flett, 1991): included subscales for self-oriented, other-oriented, and socially prescribed perfectionism.

• Scale of Creative Attributes and Behaviors (SCAB; Kelly, 2004): included subscales for creative engagement, creative cognitive style, spontaneity, tolerance, and fantasy

• Social Coping Questionnaire (SCQ; Swiatek, 2001): included 34 items describing different coping behaviors and strategies that individuals might use to deal with the social stigma associated with giftedness

However, preliminary reliability analysis for the original seven social coping subscales for this sample yielded lower than desirable results. Therefore, this study developed new subscales for the SCQ instrument. To this end, all items were subjected to an exploratory factor analysis using the Maximum Likelihood extraction method with a Promax (oblique) rotation. Six subscales were created based on this EFA, with five factors retaining their original names, one given an adjusted name to reflect a slightly different construct, and one original subscale dropped completely. The new subscales were: 1) Denying Giftedness, 2) Resisting Popularity, 3) Activity Level, 4) Using Humor, 5) Peer Acceptance, and 6) Helping Others.

In the next phase of analysis, Ordinary Least Squares regression was used to build six separate models, with each of the new social coping

strategies scales as the outcome variable. The models also controlled for the demographics of gender, first-generation status, and amount of previous gifted program exposure in the first block, then added the BFI traits in the second block, the MPS in the third block, and the SCAB in the fourth block.

(See above Fig.1: Summary of Regression Models )

The overall findings from all six models suggest that certain personality traits, aspects of perfectionism, creativity, and demographic characteristics predicted students’ use of social coping strategies. The predictor variables accounted for 4.6% to 35.3% of the total variance on social coping subscale scores. There were also different patterns of significant predictors for each of the coping strategies. Generally, this suggests that honors students have developed a variety of strategies to deal with the social stress that arises from the stigma of giftedness, which they may be experiencing at fluctuating levels depending on their other traits and experiences.

(See Table: Summary of Significant Regression Coefficients )

One central finding from this study points to the experience of high achieving individuals in higher education as different from those experiences of younger students. The new factor structure from the social coping items in this young adult population suggests that university students in honors programs are experiencing, and therefore responding to, social stressors differently than students in middle school or high school. In terms of strategy use, the most frequently used were helping others, peer acceptance, and activity level, which

VISION, Volume 34 No. 1 2023

Denying Giftedness Resisting Popularity Activity Level Using Humor Peer Acceptance Helping Others Women+ Previous gifted program exposure-+ Extraversion-+++ Agreeableness ++ Conscientiousness-+Neuroticism++ Openness--+ Self-oriented perfectionism-Socially prescribed perfectionism++++ Creative engagement++ Creative cognitive style+

+ Tolerance + + denotes positive significant predictor - denotes negative significant predictor

Fig.1: Summary of Regression Models

Spontaneity

7

Table: Summary of Significant Regression Coefficients

indicates a more proactive approach to social stress. Conversely, the least frequently used strategies were denying giftedness and using humor. These approaches might be useful for students as they navigate the cliques and bullying of middle and high school, as was the case with the original scale and sample, but their prevalence seems to lessen in a higher education setting.

One interesting finding was that previous gifted program exposure was a positive predictor of using humor and a negative predictor of denying giftedness. It may be the case that because these students have already been identified as gifted during prior educational experiences, they are more comfortable with this status and subsequently more comfortable in showing their intellect. The majority of study participants did report receiving some kind of gifted programming during their K-12 experience, although the amount and types differed. If a student has been formally identified as gifted and participated in a greater amount of gifted programming during their prior education, it makes sense that they are more likely to have accepted this label and perhaps even incorporated it into their sense of identity, compared with students who had less exposure to previous gifted programming.

Together these findings can be useful in the development of programming and interventions for helping gifted students transition into an honors college setting, and deal with social stressors they may encounter. Given the connection between creativity and several coping strategies, parents, staff, and administrators can encourage students to engage in creative outlets. Honors programs can provide low-risk and non-evaluative instruction in areas such as music, dance, fine arts, improv, creative writing or journaling, to name a few. Some creative endeavors are formally sponsored and/or group activities such as performing arts like music and drama, so the social interactions involved in these activities would be a good fit for gifted students who are incorporating these social coping strategies.

For students who are more introverted (and potentially less likely to engage in the more positive social coping strategies such as activity level and helping others), advisors could recommend participation in high-impact practices such as research with a faculty member or engagement in culminating projects in their academic discipline (Kilgo et al., 2015). Another introvert-friendly program might be the creation of a “reading-for-pleasure” book club that would be a way for those less outgoing students to still participate in some structured social interaction while also engaging in a solitary activity. For those students higher in neuroticism or perfectionism (or both), providing workshops on time and task management might help them deal with stress (while incorporating socialization during the workshop itself).

The findings from this study are encouraging, although further research with more diverse and recent samples is still needed. While representative of the honors college at this particular university, the sample was somewhat homogenous in terms of age and ethnicity and might not generalize to all high ability young adults across the US, let alone the world. Furthermore, this data was collected several years prior to the COVID pandemic. Given the extreme disruption of the pandemic on higher education and the student experience, it would be useful to replicate this study in the future.

In sum, honors college students seem to be dealing with the social stigma of giftedness in different ways than previously found in younger populations. Identifying these coping strategies and exploring which ones are used by various types of students (as was done with the predictive models in this study), can help in advising and counseling them as they begin their university experience, and throughout their higher education journey. Acknowledging how psychological traits relate to social coping for these high ability students paints a better picture of their lived experience and provides gifted practitioners with a context to better serve this population in the future.

The full article is available online, and is open-access:

Miller, A. L. (2022). Social stress in Honors College students: How personality traits, perfectionism, creativity, and gender predict use of social coping strategies. Supporting Emotional Needs of the Gifted Journal: Exploring the Psychology of Giftedness (SENGJ), 1(1), 20-36. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/sengj/vol1/iss1/5

Angie L. Miller is an Associate Research Scientist in the Center for Postsecondary Research at Indiana University Bloomington. Dr. Miller does research and data analysis for the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) and the Strategic National Arts Alumni Project (SNAAP). Her research interests include student engagement, creativity assessment, utilization of creativity in educational settings, and factors influencing gifted student achievement. https://education. indiana.edu/about/directory/pro files/miller-angela.html

If you have research related to the social and emotional needs of gifted individuals to share, consider publishing in SENG Journal: Exploring the Psychology of Giftedness (SENGJ). SENGJ publishes original research on the psychology of gifted individuals, and was created to offer opportunities for diverse voices and points of view on topics important to society as they pertain to the psychology of individuals with the ability or potential to perform or produce at exceptional levels. The aim of SENGJ is to promote the social, emotional, and psychological well-being of these individuals.

As the official scholarly publication of the SENG organization, the online open-access journal publishes peer-reviewed, rigorous research, including:

• Original studies

• Reviews of research

• Meta-analyses

• Theoretical explorations

• Substantive interviews with leaders/experts in the field

For more information on article submission, see: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/sengj/

VISION, Volume 34 No. 1 2023

8

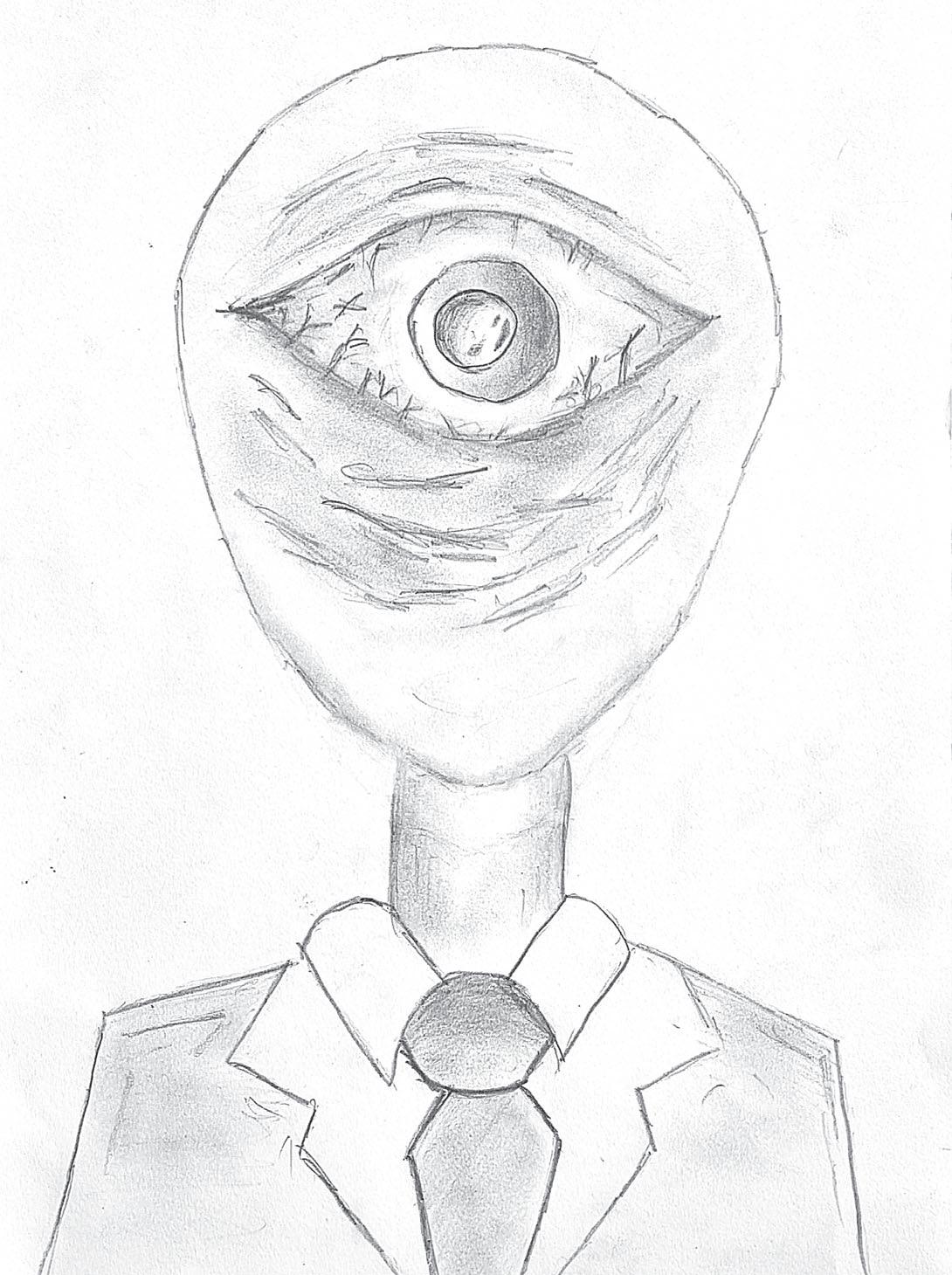

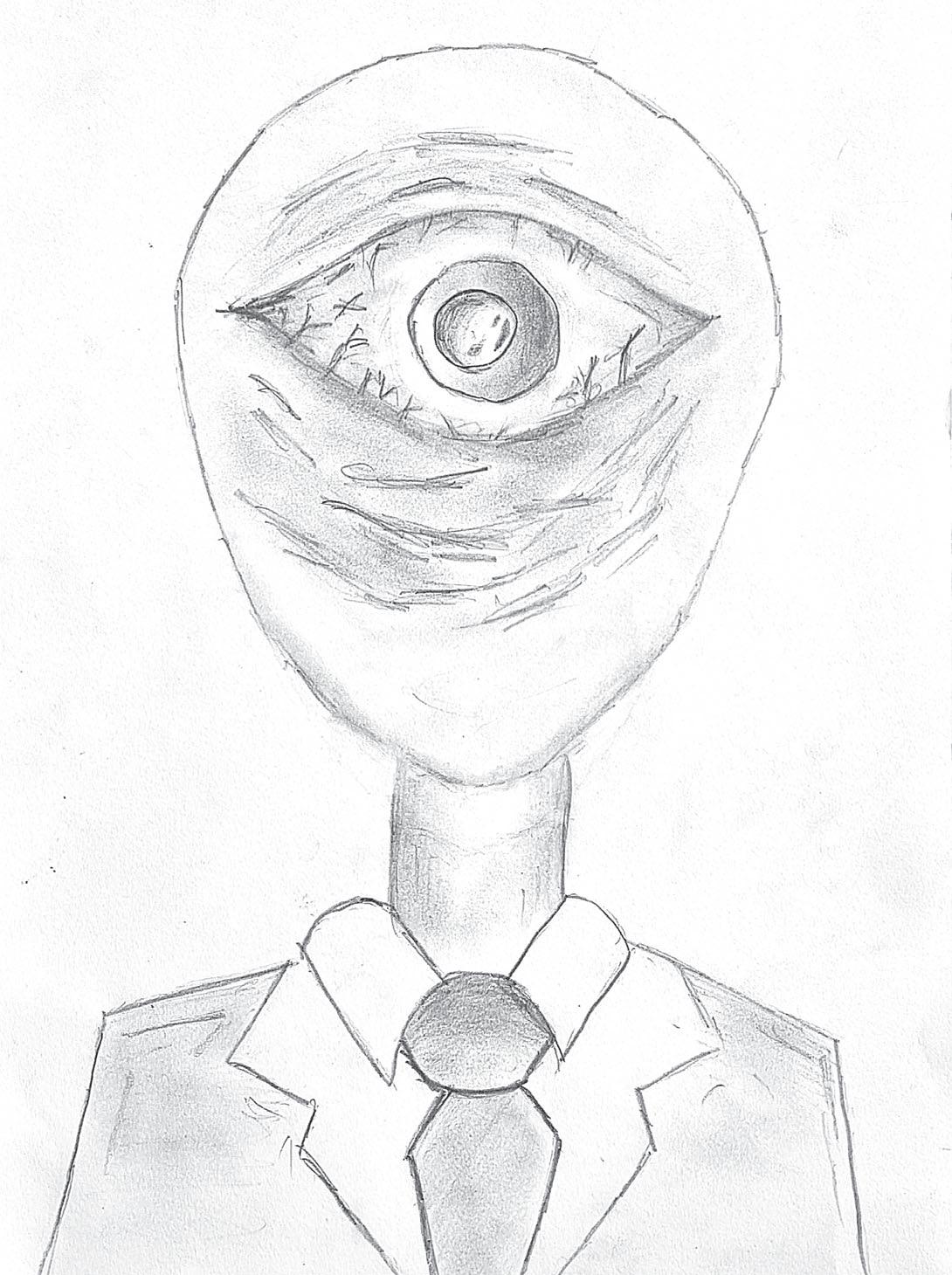

Student Reflection Aarav Mehra Art Expression

Moving to a new country can be a challenging experience, and it’s understandable that it may take some time to adjust to the cultural and social differences. As someone who has recently moved from the Indian to Australian education system, I faced a number of struggles during my transition period. I felt forced to sacrifice my pursuit of art when I first arrived, although I had spent years developing my skills and passion for Art. As I continue to adjust to life in Australia and at St John’s College, it is helpful to find ways to connect with others who share my interests in art. Art can serve me as a means of relaxation as it allows individuals to engage in creative activities that promote mindfulness and well-being. Moving to a new country and a new school also encouraged me to set some life goals for myself. Most of my goals were related to Art, such as how I want to be a well-known young artist in the community. Art is currently more like a hobby to me, but I would be delighted to turn it into a career. Now that I have settled down here, I can definitely say that moving to Australia really helped me to express myself through art in different ways and further explore my gifts.

Aarav, Year 8, St. John’s College, Preston

VISION, Volume 34 No. 1 2023

Title: Wintertide.

Title: Oculus.

Title: Curious Castle.

9

Keynote Resource Managing Expectations of Giftedness and Talent Stewart Milner, Principal, CHES

“BUT ONE CAN QUITE EASILY TEACH WITHOUT EDUCATING, AND ONE CAN GO ON LEARNING TO THE END OF ONE’S DAYS WITHOUT FOR THAT REASON BECOMING EDUCATED” - HANNAH A RENDT (1954)

As the foundation principal of the new Centre for Higher Education Studies (CHES), I am delighted to contribute this keynote essay for this issue of Vision, in response to the theme - Managing Expectations of Giftedness and Talent - and to take this opportunity to introduce CHES to VAGTC members.

Clearly, there are a range of expectations to manage in relation to highability and gifted children and young people. Families, schools, and communities all hold expectations of them. At times, those expectations can help or hinder them in reaching their potential, developing their talents, and contributing fully to the world. We know that gifted young people can also place certain expectations on themselves which may need to be managed. At CHES, our goal is to extend, challenge and accelerate high-ability students in senior secondary government schools across Victoria, and to support them in navigating options and pathways through into university.

Introducing the Centre for Higher Education Studies (CHES)

CHES is a new centre of excellence established to cultivate the potential of high-ability and high-achieving students in government schools. Our extension, enrichment and acceleration programs commenced in January this year. CHES is a direct response to the Victorian government’s intention that all students, regardless of their starting point, are supported to realise their full potential.

Navigating opportunities for high-ability students

At CHES, we only work with high-ability senior secondary students. However, I recognise that the overall educational journey, through primary school into secondary and beyond, is certainly not without its challenges for families. There are many decisions to make in navigating the most appropriate pathways and settings, while considering the child’s unique abilities, aspirations, and stage of development.

CHES is one part of the overall Victorian education system. In addition to CHES, there are numerous initiatives for high-ability and gifted students in government schools across Victoria, including the awardwinning Victorian High Ability Program for students in Years 5 to 8 and the Victorian Challenge and Enrichment Series. This is complemented by the appointment of High Ability Practice Leaders in all government schools, and the launch of the High Ability Practice Toolkit to support effective teaching practice. Schools implement various approaches to bring out the best in high-ability students, including the delivery of curriculum which promotes depth and exploration, personalised programs, differentiated teaching, and ability-grouping, and the kind of acceleration and enrichment we offer at CHES.

At CHES, we coordinate and support accelerated access to university studies, and we aim to strengthen those tertiary pathways. We currently offer 17 Higher Education Studies (first year university subjects), through our partnerships with several universities, and we specialise in two VCE studies which are of great appeal to high-ability senior

students: VCE Algorithmics and VCE Extended Investigation. CHES is a bridge between school and university, and between metropolitan and rural Victoria. We aim to bring highly able students together, build a robust community of learning for them, and enable students to form networks which support them as they transition to university.

Empowering high-ability students from disadvantaged backgrounds

Excellence and equity underpin the foundation of CHES. We emphasise equitable access for highly able students in regional, rural, and remote areas of Victoria and for those who are socioeconomically disadvantaged. These students have traditionally been underrepresented in accelerated university studies. Our aim is to remove barriers and impediments. Currently, over one quarter of our enrolments are from high-ability students in rural Victoria and about one third are students from disadvantaged backgrounds. These highability students can access our programs regardless of where they live, without needing to leave their local community, because we use a contemporary “hy-flex” approach to teaching and learning. This enables students to join our programs online or on-site from around the state and, wherever possible, to schedule their engagement in our programs at times which suit their school timetable, including lessons and special events adjacent to regular school hours. Our staff develop and implement Individual Achievement Plans through discussion with each student, taking into account their longer-term goals, aspirations and passions, as well as determining the short-term logistics of their enrolment and participation in CHES courses.

Managing the academic expectations of students

The expectations that high-ability young people place on themselves can sometimes be excessive. Burnout is a risk to be managed. Our students are studying a Higher Education Study, as part of their overall VCE program, and one of the main challenges can be balancing their workload demands. Our Individual Achievement Plans provide a strong foundation for monitoring student progress, whilst the positive relationships between staff and students underpin wellbeing support. We work closely with families, base schools, and universities, to support the learning, health and wellbeing of students.

Managing the challenges of childhood and adolescence

Throughout their educational journey, gifted students are managing not only their academic studies but also their personal identity development, social cognition, and their place in the world. They are forming the values which will shape their lives and underpin their aspirations for the future. In addition to managing their studies, students are often managing their participation in a range of extra-curricular activities, and their role in friendship groups and families, which may even involve carer responsibilities. In many cases, high ability young people are also balancing responsibilities as leaders in various group settings and managing the pressure to step up into those leadership positions.

In my experience, it is crucial that the partnership and communication between home and school is strong, so that the expectations we place

VISION, Volume 34 No. 1 2023

10

on students, and they place on themselves, can be cohesively and successfully managed. This is ongoing work because there are times when students may be taking on too much and are at risk of burnout, and there are times when students may be taking on too little and ‘cruising’ or disengaging. At the senior secondary level, we actively encourage high-ability students to communicate with the adults in their life about future careers and pathways. Careers counsellors and wellbeing coordinators in schools also play an important and influential role.

Managing the societal expectations of high-ability young people

On a broader societal level, the demands we place on young people with high cognitive abilities need to be managed. The eminent American psychologist and intelligence researcher, Robert Sternberg, emphasises the importance of ‘transformational giftedness’ rather than ‘transactional giftedness’ (2020). In this framing of talent development, Sternberg argues that we need to do more than funnel high-ability young people through the proverbial academic sausage factory. He points towards the importance of developing the capacity and passion of high-ability young people to positively change the world. Of course, for students, the desire to achieve high academic results is not mutually exclusive from the desire to respond to the world’s needs and to create a life worth living. There are many ways that high-ability people contribute to society and change the world for the better, while balancing their own needs and aspirations. As parents, carers, and teachers of high-ability young people, it is imperative that we provide them with the support they need to navigate their way in the world and to foster their commitment to contribution.

We have found that many of our students are keenly interested in contributing to broader improvements in our world, and in using their abilities to tackle complex real-world problems. Many have a great passion for causes, both global and local. They readily engage in discussions about these problems and potential solutions. They recognise that we face a range of significant problems - climate change, loss of biodiversity, infectious diseases, conflicts and wars, inequality and poverty, repressive regimes, political polarisation, aging populations, increasing mental illness, resource depletion, recessions, famine, and the threat of intentional or accidental misuse of technology to name a few they’ve identified - and they know that these are consequential problems affecting large numbers of people, and potentially the entire planet.

At CHES we offer an enrichment series which includes masterclasses from leading academics. To inspire students to consider how they can transform the world. For example, over the past two weeks, we’ve held three separate masterclasses. In the first two, students engaged with University of Melbourne physics professors, Steven Prawer and Geoffrey Taylor. The first presentation was on the frontiers of high-

energy particle physics, and the research that some of our students from Warrnambool are involved in relating to ‘dark matter’. The second presentation was on the application of physics to the development of brain implants made from diamond, to enable blind people to see certain shapes and people with epilepsy to detect upcoming seizures. Our third masterclass was on contemporary applications of Artificial Intelligence with Dr Piyush Madhamshettiwar, who is a leading Australian AI and Machine Learning consultant. These masterclasses are optional for our students and cover a range of subject areas and topics, not just the sciences. The emphasis is not only on informing students of cutting-edge research, but also to enable them to identify which pathways excite and inspire them - and why.

Preparing high-ability students for the future

While we cannot know ahead of time all the potential roles, responsibilities, challenges, and opportunities students may face in future, we can equip them with effective analytical, creative and practical thinking skills. To prepare students for the future, we emphasise the development of critical thinking and problem-solving skills at CHES, through VCE Extended Investigation and VCE Algorithmics.

In our VCE Extended Investigation course, students explore and research areas of interest, and identify and test solutions to significant problems on a local level. Rather than wait until they have graduated high school, students can begin exploring and addressing issues of interest to them through a rigorous and structured research process.

Students who are taking our VCE Algorithmics course are learning and applying logical reasoning to address real world problems. They apply some of the algorithms that underpin major systems, such as coordinating networks and optimizing supply chains, predicting the effectiveness of vaccination schemes, estimating resources for growing populations, and establishing appropriate guard rails for artificial intelligence.

Without placing overwhelming expectations on them, it is evident that many highly able students can, and will, go on to have a disproportionate impact on the world beyond school. With the right supports, many will rise to the top of their fields and take on roles of influence and leadership. While we hold high hopes for the contributions they will make in future, it is important that we also educate them to lead fulfilling personal lives and to cultivate their unique talents for their own sake.

Finally, I believe that many CHES students intuitively understand that education is more than just memorisation for VCE exams. Rather, they are cultivating their curiosity, harnessing their talents, and gradually taking responsibility for themselves and the world. In that respect, CHES students seem to grasp the meaning of the Hannah Arendt quote above and are already embodying what it means to be highly educated. They are finding meaning in active citizenship and they aspire to become ethical and effective leaders and to make the world a better

VAGTC PARENT & EDUCATOR SEMINARS

We run seminars on a regular basis for parents and educators of gifted and high ability children. Please check our website for more information: www.vagtc.org.au/seminars/

11

VISION, Volume 34 No. 1 2023

place. If we manage expectations appropriately, I have no doubt that highly able and gifted young people - whether taking up opportunities here at CHES or through other wonder ful settings and initiatives - will find ways to innovate, wherever they live and work in future. Further information on the Centre for Higher Education Studies can be found at: https://ches.vic.edu.au

Graduating with a Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Business at Swinburne University and then a Graduate Diploma in Education at the University of Melbourne, Stewart began his teaching career in Sunbury in 1999. His subjects included Japanese, accounting, business management, humanities, and English as an Additional Language (EAL). Early in his career, Stewart moved into leadership roles within the Department of Education, focusing on strategic planning, leadership coaching, languages education, centres of excellence, and literacy and numeracy initiatives in some of Melbourne’s most disadvantaged communities.

In 2011, Stewart was appointed to the position of Assistant Principal for the launch of the newest selective-entry school, Suzanne Cory High School in Werribee. Over the next five years, he was responsible for leading the development of the school-wide curriculum, teaching and learning framework,

and professional learning programs, and for overseeing workforce planning, facilities management and maintenance.

In 2012, Stewart completed a Master of School Leadership at Monash University.

In 2016, Stewart was appointed as Principal of Coburg High School. Coburg High School has since expanded from 340 students to 1,200 students with steady improvements in NAPLAN and VCE outcomes and a strong reputation for educational innovation. In 2021, Stewart was seconded to the position of Senior Education Improvement Leader (SEIL) overseeing 25 government schools in the Banyule Nillumbik network in the north-western region of Victoria.

As the Foundation Principal for the Centre for Higher Education Studies (CHES), Stewart is passionate about working with high-ability students to:

• cultivate their potential and talents

• accelerate their learning

• support them to pursue their passions

• challenge them to strive for excellence and make valuable leadership contributions

• strengthen their wellbeing to overcome adversity and realise their full potential.

STUDENT SUBMISSIONS INVITED!

We are particularly interested in hearing from students/children in our next edition, which is on the theme: Managing expectations of giftedness and talent. If you would like to contribute a reflection, story, essay or visual piece, please contact vision@ vagtc.org.au for further information and guidelines.

VISION, Volume 34 No. 1 2023 12

vision@vagtc.org.au 12

Worried and Watchful: 7 Hacks for Helping Kids with ADHD Manage Anxiety

Sharon Saline Psy. D.

MOST KIDS AND ADULTS JUST WANT THEIR ANXIETY TO GO AWAY NOW. As parents, we try to anticipate and cope with the fear of our child or teen by trying to protect them from the pain. I don’t know about you, but this rarely worked in my family because the worries just came back. Anxiety – the physiological response to powerful worries –needs to be addressed head on. We have to teach our neurodivergent kids tools to cope with their worries, so that they feel empowered and confident to take risks and meet unforeseen challenges. Even though anxiety loves reassurance, because it offers short-term relief from discomfort, telling kids that everything will be okay or not to worry only increases long-term anxiety. These reassurances don’t work, because you are not teaching the necessary coping skills your child or teen actually needs. Instead, everybody benefits when you take a different approach. Although it’s more useful to acknowledge their fears, validate their concerns and brainstorm solutions-together, let’s face it – this can be a tougher road to travel.

Unlike nervousness which goes away once a skill has been mastered, anxiety can take over a child or teen’s life. Worry differs from anxiety. Worry refers to how we think about something. Anxiety is our physiological response, based on negative thoughts and distorted beliefs. We cannot eliminate anxiety: it’s a natural human response that’s evolved for survival. It thrives in the petri dish of natural child development and in a culture that is obsessed with comparisons and instant gratification. Without useful self-management strategies, and unable to access the internal resources they need, anxious kids freak out or refuse to do anything. But, when they learn how to talk back to worried, negative thinking and rely on past successes for confident choices in the present, they learn how to tolerate the discomfort of not knowing and they can accept the possibility of disappointment. This is how neurodivergent youngsters develop the resilience that’s crucial for becoming a competent, successful adult.

Despite misdiagnoses, ADHD differs significantly from anxiety. While kids with ADHD wrestle with organization, working memory challenges, impulse control, kids with anxiety struggle with compulsive, obsessive or perfectionistic behaviors, psychosomatic ailments and debilitating specific phobias. Issues related to food, housing or job insecurity, systemic racism or trauma further intensify anxiety. According to the CDC, approximately 7.1% of U.S. children (aged 3-17 years old) currently have an anxiety diagnosis1 and the rates are higher for females (38%) than for males (26.1%)2. For 34% of U.S. kids with ADHD, anxiety is often a frequent companion3, because of neurological patterns and the ways that executive functioning challenges and delays make it harder for kids to manage big feelings. Plus, youngsters with ADHD often miss visual or auditory cues and misread facial expressions, fostering social anxiety. Their concerns about ‘messing up again’ amp up into persistent worry about the next time that they will (unwittingly) mess up or forget something important. Children and teens become overwhelmed beyond their coping skills and anxiety moves in. Anxiety is a shapeshifter. Just when you think you’ve figured how to deal with one issue, another one pops up. It’s like playing Whack-A-

Mole. To avoid this frustration, you’ve got to step back and see how your teen’s anxiety operates and not react to the content. It’s the reaction to the worry, not getting rid of it, that makes the difference. Dismissing concerns (“This isn’t that big of a deal. You’ll be fine.”) doesn’t honour the reality of their worry. It will grow. Reassurance (“Don’t worry, everything will work out”) also doesn’t provide a lasting solution because your teen learns to rely on other people making things okay for them, even though no one really can. Instead, validate their concern by saying “You’re right to be scared. You’re not sure you can handle that. It’s natural to worry in that situation. What else could you say to yourself?”. This lets them know that you heard their worry and acknowledge that it’s real, while simultaneously guiding them towards managing it.

Practical tools for helping kids manage their own anxiety is what works best to reduce it. Here are 7 strategies to try:

1. Manage your own concerns first: Kids have incredible radar. They easily pick up when their parents are stressed or anxious and it increases their own distress, conscious or unconscious. The first step is to lower your own anxiety. Discuss your concerns with your partner, a friend, extended family member or counsellor. Write these down and then strategize responses or to-do action items to each by creating an “Anxiety Decelerator Plan.” This ADP will help you feel like you have some control. For instance, if your child needs more academic support, you can contact the school to set up a meeting.

2. Identify their worries: We can’t assist kids in turning down the frequency or intensity of their anxiety, unless we know what’s causing it. Worried thinking and environmental triggers can set off children and teens. We want to stop this tumble. During your weekly or twice a week check-in meeting (these are a must), explore what might be uncomfortable or uncertain for them. Write these down. Pick one fear together to address first and, when its volume is lower, you can pick another. People can really only change one thing at a time.

3. Change the relationship to anxiety: Think like Sherlock Holmes and investigate anxiety like a puzzle. When, where and how does it show up? What are its triggers? Brainstorm with your teen what to say when worry arrives: “Hmm, that sounds like worry. What could you say to size it down?” Separate anxiety from who your teen is. Many kids feel powerless about anxiety and benefit from redefining it as something distinct from who they are.

4. Stay neutral and compassionate without fixing: Although you must intervene in situations of bullying, violence, academic failure or risky behaviours, most of the time your teen needs your support in thinking through responses to tricky situations, not solving them. Kids of anxious parents are more likely to be anxious themselves. Monitor your reactions about your child’s anxiety and refrain from discussing your concerns in public. React neutrally, regardless of their irritating, frustrating and sometimes scary behaviours. These behaviours are demonstrating how out of control your child or teen feels inside, which is why anxiety exists in the first place.

VISION, Volume 34 No. 1 2023

Keynote Resource

13

5. Start small to build confidence: Anxiety is great at erasing memories of past successes, which is compounded for kids with ADHD and their working memory challenges. Choose a goal that’s within reach and work on taking a small step first. What would your teen want to do if anxiety wasn’t there? Help them recall times when they took a risk and succeeded. Then, discuss how those strategies can apply to this situation. Offer them language: “I’m willing to feel unsure. I can grab onto my courage and try this.” This calms the anxious brain.

6. Opt for curiosity over anxiety: It’s tough to stand in uncertainty and, frankly, adolescence is filled with unknowns. Kids often feel a distinct lack of control in their lives, which fuels their anxiety. Instead of worried thoughts, though, you can assist kids to shift to curiosity. Where anxiety shuts youngsters down and predicts negative outcomes, curiosity opens them up to possibilities. Work with them to say “I wonder about ...” rather than “I’m worried about ...”

7. Focus on building resilience: Resilience is the antidote to anxiety. When your kids identify strengths, people who care about them and develop an interest, they feel more confident. Find ways to connect on things that matter to them, like a favourite computer game or funny YouTube video. Nurturing this connection will improve their willingness to work with you in tackling anxiety.

Sharon Saline, Psy.D. is a licensed clinical psychologist and the author of the award-winning book, “What Your ADHD Child Wishes You Knew: Working Together to Empower Kids for Success in School and Life” and “The ADHD solution card deck”. She specializes in working with children, teens, adults and families living with ADHD, anxiety, learning diff erences and mental health issues. She speaks internationally and consults with schools and clinics on various topics related to neurodivergence. She is a part-time lecturer at the Smith College School for Social Work, blogger for PsychologyToday.com, contributing editor for ADDitudemag.com, featured expert on MASS Live TV and hosts a bi-weekly Facebook Live event for ADDitudemag. com.

Student Voice Angelique Fardis Behind the Scenes of Being a Gifted

With the title of ‘gifted student’, it’s easy to lose sight of yourself and get in your own head. I don’t like tooting my own horn, but I know I do well academically, something I have worked hard to achieve. Still, being held on a pedestal is not exactly glamorous. Every time I get stuck on a question, I feel horrible because ‘I should be smart, this isn’t supposed to happen’. In saying this, I’ve always struggled in asking for help from teachers and peers.

In managing expectations of yourself, it’s important to remember that you’re not Superman. You’re not perfect and that’s okay. You need to realise that sometimes you are going to come across challenging content. This is healthy. Set realistic and achievable goals for yourself and work hard to achieve them. Strive to do your best. If you reach a wall in your studies and general life, find a way to get around it. Never feel embarrassed to ask for help just because you’re a ‘gifted child’; we all have something to learn.

In being a gifted student, it’s also easy to be side-tracked by everyone else’s high expectations of you. This is something I’m currently trying to manage; however, I’ve come to realise that I am my own worst

Student

critic. Learning not to worry about what other people think about you is challenging, so my advice would be to focus on the expectations you have for yourself rather than what everybody else expects from you. Only you really know yourself.

One other thing about me is that I am a major stress head. I play soccer outside of school as an effective stress reliever. I highly recommend having something that relieves stress you get from school as it helps to clear your mind and get you back in a positive mindset. Whenever I feel overwhelmed or stressed, I take a step back from my schoolwork and focus on other things that make me happy like going for a walk outside, listening to music and hanging out with my family. Being a gifted student doesn’t exempt you from stress; take time to look after yourself and your happiness and wellbeing.

Angelique Fardis, Year 11, St John’s College Preston

VISION, Volume 34 No. 1 2023

14 14

VISION, Volume 34 No. 1 2023

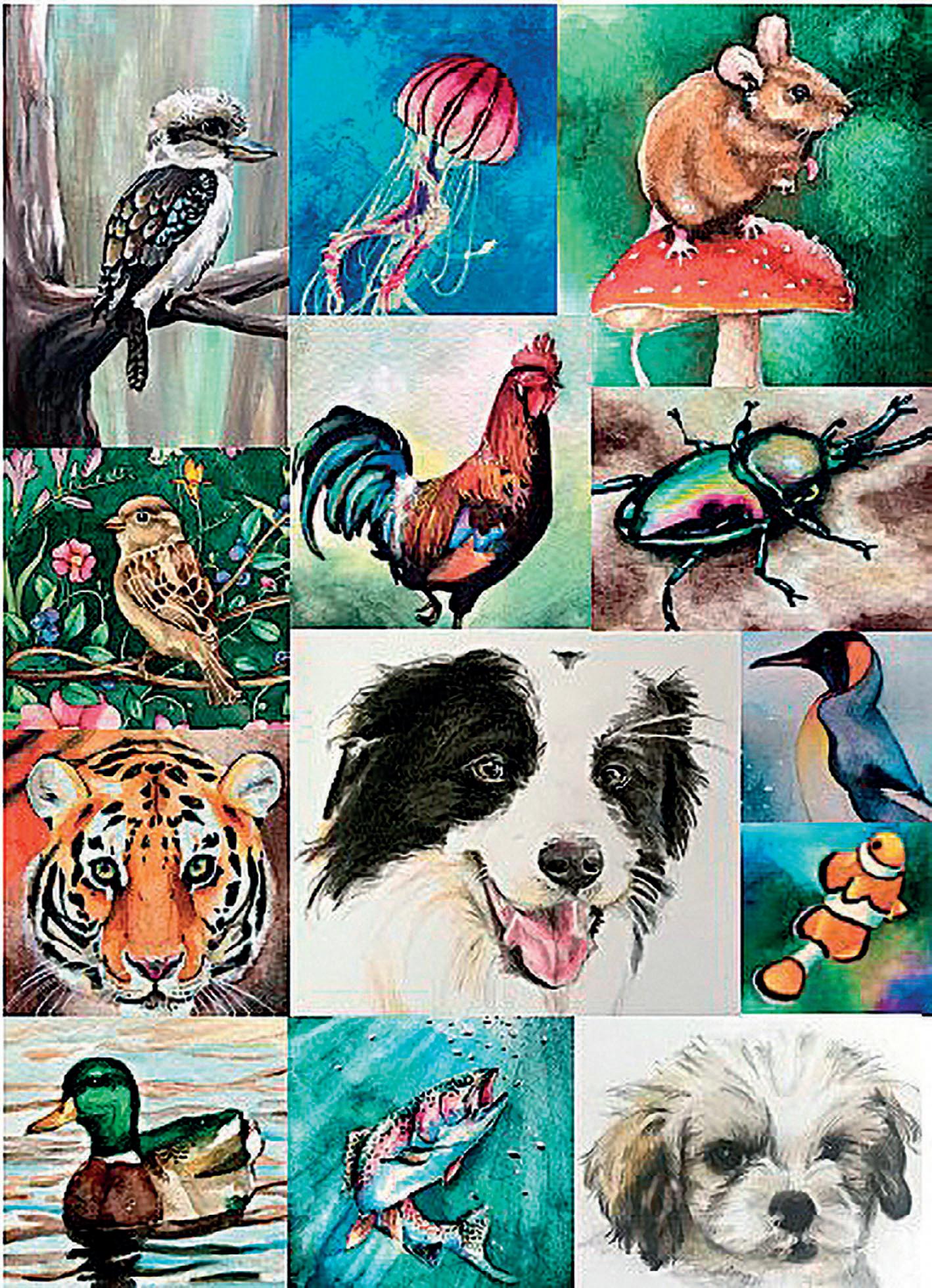

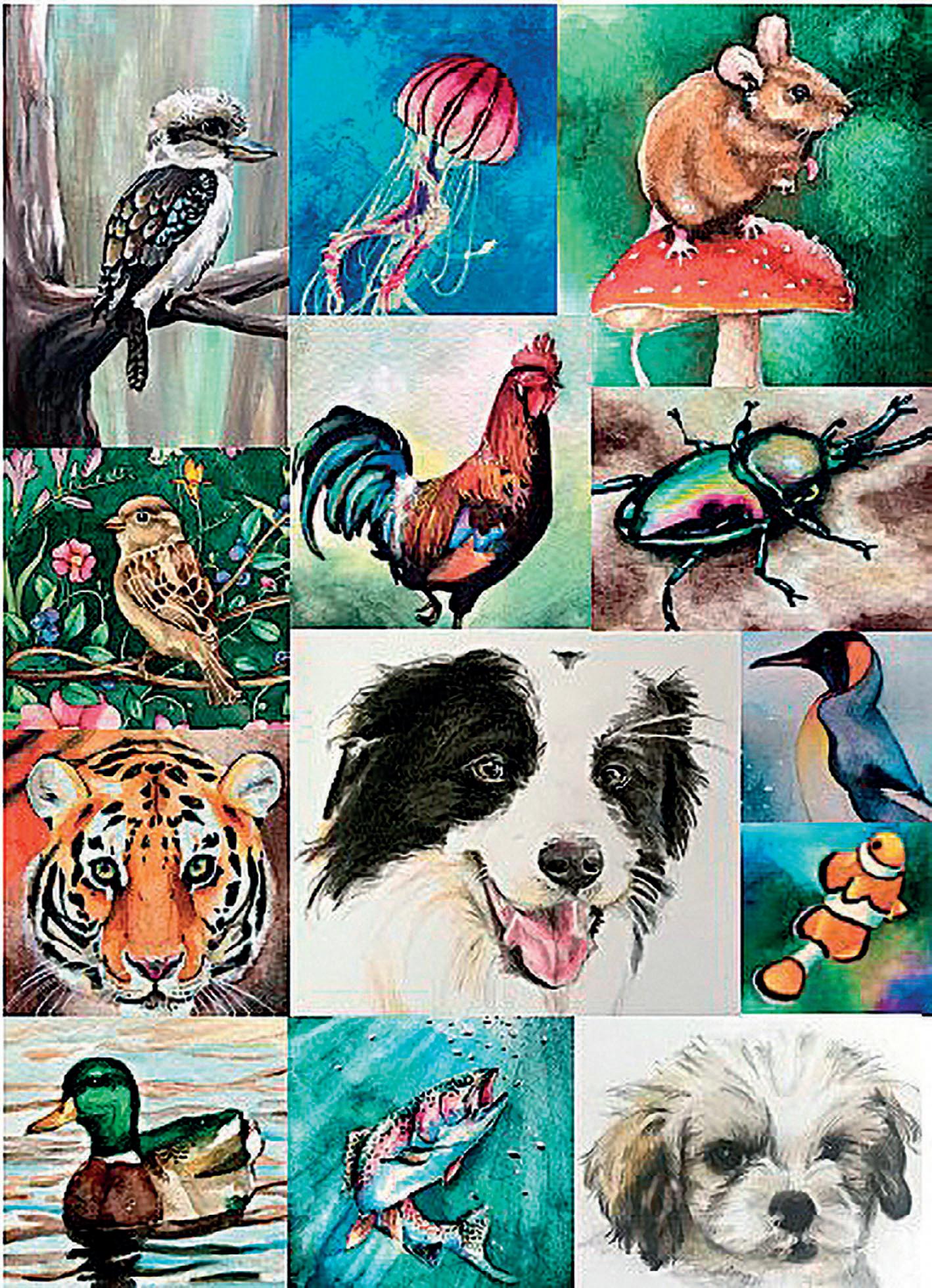

Collage - by Julia, Year 12, Mount Evelyn Christian School, Montrose

15

Lion - by Alannah, Year 6, Holy Name Primary School, Reservoir

Gifted Education Week Winners The Diverse Faces of Giftedness Student Voice

WHEN I WAS FOUR, I BEGAN ATTENDING KINDERGARTEN. This was a time of many new experiences for me, but perhaps there was one experience that seemed the most peculiar.

At that age, I was already wearing spectacles. Soon I became known as, ‘that kid who likes reading,’ and the meaning of this was somehow attached to my glasses. Kids would go home and ask their parents for glasses, so that they too would be ‘good at reading.’

This was probably my first exposure to stereotypes.

The name ‘homo sapien’ means ‘wise human,’ and in our quest for wisdom, we are constantly striving to understand things, and to group items into neat boxes. From cells in immunology to plants in botany, this happens everywhere, including with people.

We grasp onto certain traits such as wearing glasses or somebody’s skin colour – and immediately associate it with stereotypes ingrained in us. We feel like we are ‘wise’ and we can now know everything about that person based on that trait.

We don’t assume that the homeless person we passed on a street could be talented or that the unnoticeable kid who sits at the back of our classroom could be good at playing the tuba. Our fixed ideas on who is gifted and what it is in itself prevents us from seeing its diverse faces.

And while many objects can be sorted, humans are complex and unique, making such superficial sorting pointless. So the next time you meet a bespectacled person or someone from a different background, step back and consider them not just from the stereotypes you feel they should live up to, but by who they are as a person. It is only through this, that we can allow the different faces of giftedness within each person to shine through.

THERE ARE BILLIONS OF US ON E ARTH. Around eight billion, in fact. And, no matter 1 or 100 years old, every single one of us is great at something.

Our next door neighbours are experts at leaping high into the air on their trampoline, my mum gives the greatest hugs of all time, and my dad can serve the ultimate badminton serve.

They are naturally good at the things they do. Do the siblings ever think ‘I’ve got to jump higher!” or Mum ask ‘Should I hug more tightly or with higher hands?’? Even though these may not be considered gifts, they are naturally done- not honed over years of back-breaking practice!

What do you picture when you hear the words ‘gifted person’? A person with glasses perhaps. They may be wearing a suit, or a pressed skirt. They might be holding a book, or have a pencil in their locks. But imagine this- a man with unruly hair, who wore mismatched socks daily, and who didn’t speak until he was four. You may think that there would be no way that this person would be gifted, but he is a person that you have definitely heard of. With an IQ of 160, and a Nobel Prize in physics, the person who matches that very description is Albert Einstein.

Gifted people come from all over the globe. There is no particular trait that all these people have in common (apart from being gifted). No matter what gender, no matter from where in the world, no matter what culture or language or time or age or wealth, no particular type of person (for example, rich men of ages 20-60 with blonde hair and blue eyes) is gifted. We may all be different, but it’s those differences that make us stronger.

TALENTS AND G IFTS.

Talent - Mother Nature’s gift, No one knows what it really is, A bunch of lies, An expert skill?

Maybe something made to kill?

So why do we discriminate Our talents and our skills?

When we don’t even understand, What it truly is!

Mother Nature blessed us all With everlasting gifts, And all we do is counter them, With negatives on lists.

Every individual, Whether black or white, Has always had some rules,

Constraining their own rights!

And with each breath we take, We come closer to our end. We should appreciate the gifts we have, Before they leave us dead.

You and I have talents That can be used for good. Use them while they last. Use them as you should.

We are all so different, Yet we are all the same. Nothing, I mean nothing, Will ever change that claim.

VISION, Volume 34 No. 1 2023

- Emily Lam, Yr 5, PLC, Melbourne

- Victoria Huang, Yr 5, PLC, Melbourne

16

- Ksenia Kurenysheva, Yr 8, MacKillop College, Werribee

EIGHT REMARKABLE AND VERY DIVERSE GIFTED STUDENTS SHARED THEIR VALUABLE INSIGHTS WITH US ON MAY 24TH AS PART OF THE VAGTC G IFTED AWARENESS WEEK AT THE NEW CHES FACILITY IN SOUTH YARRA. It was an extraordinary event with students presenting their stories as human libraries. Each student was placed in a different room and shared their reflections on life and learning as a gifted student to a small group of parents, students, or educators. After the presentation, students were open to answer any questions, and this was a particular highlight for many participants.

Following the human library sessions, the students came together to form a panel where general questions could be asked to the whole group. The overwhelming message from the students was directed at teachers who hold great influence in the success of students reaching their potential. They encouraged teachers to challenge them more, know when to push them harder, be their champion, and love what

An Exceptional Exchange Reflection

they are teaching.

Comments from parents, students and educators from the evening included:

“The students are all so different, but they all share the same struggles”.

“I wish we had more time to hear from the students and find out how they overcome some of the challenges”.

“The confidence in these students is amazing…I feel privileged to have heard their stories…Well done!”

“Fantastic! This was such a great way to gain knowledge about gifted students”.

“I would have loved the opportunity and time to have heard each student’s story! Great idea!”

VISION, Volume 34 No. 1 2023

Victoria Poulos

17

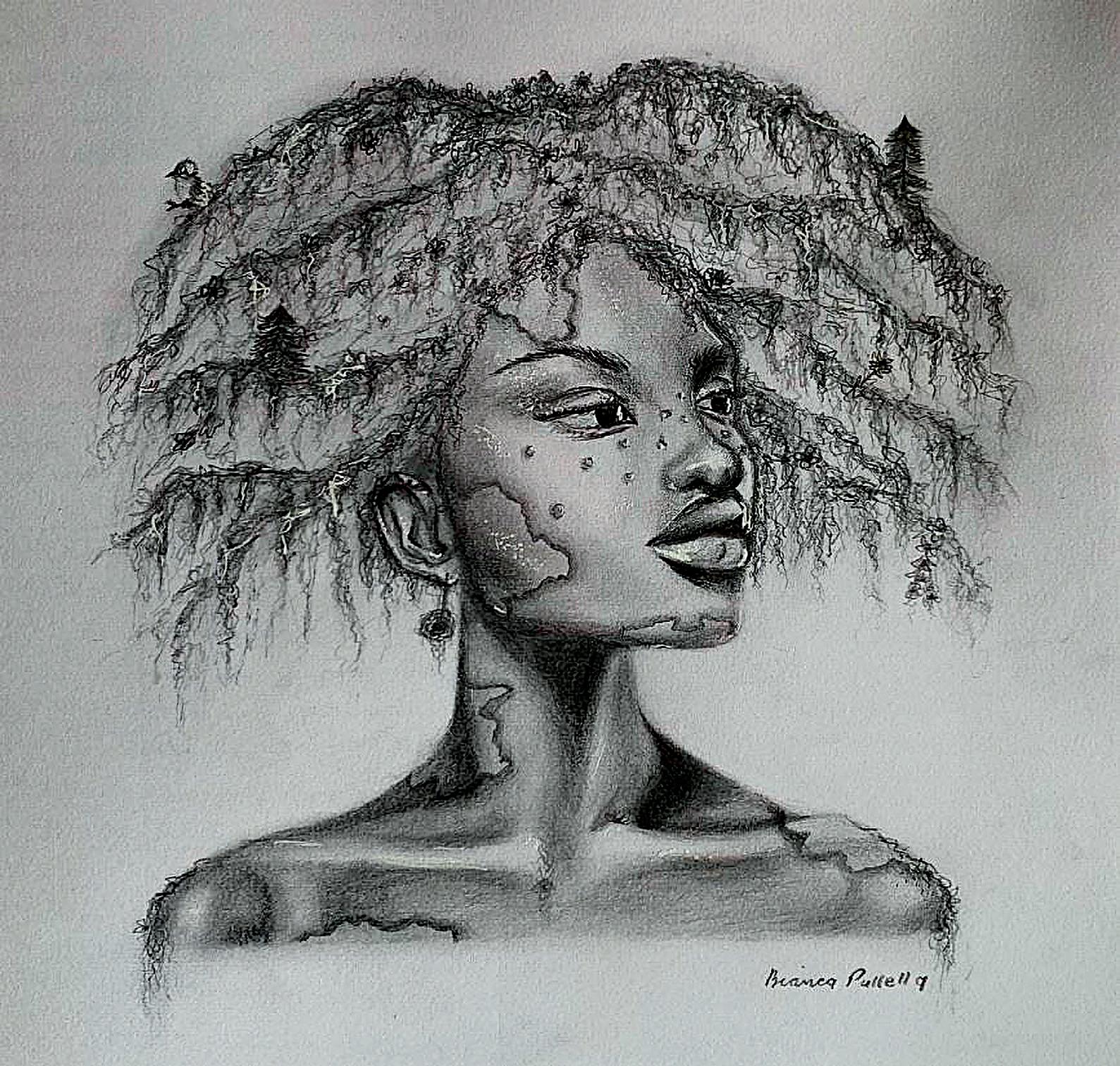

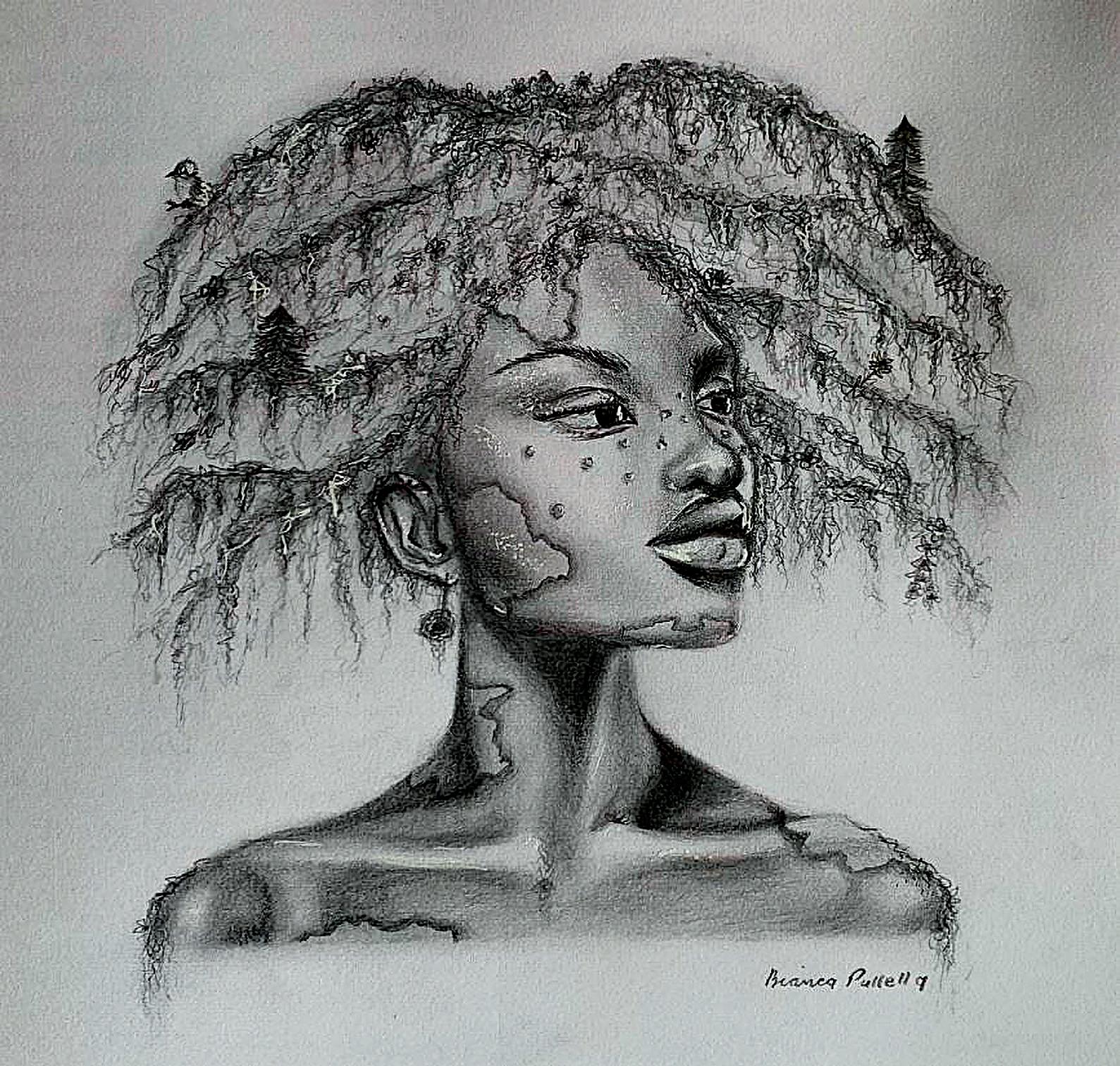

Gaia - by Bianca, Year 10, Salesian College, Sunbury

What Teachers Say About Their Expectations for Gifted and Talented Students

Natalie Dickson

INTERVIEW WITH NATALIE DICKSON, HEAD OF L ANGUAGES, ACADEMY OF MARY IMMACULATE, FITZROY.

Vision: Hi Natalie. As Head of Languages at Academy, you oversee Year 7 to VCE curriculum and with your years of experience there, have a deep knowledge of the students. What are some of your expectations for your gifted and talented students?

ND: Hello Laura. My expectations for our gifted and talented students are that they will be intrinsically motivated to learn. This means that they are encouraged to be self-directed in their learning, to explore areas of interest outside of the classroom, to challenge themselves, to be highly engaged, to set their own personal goals and to seek feedback from teachers for continual improvement. These students are generally expected to display a high level of maturity in taking ownership of their own learning. Parents/guardians at home also play a role in fostering independent learning in their children.

Vision: Do you find that you are better able to manage expectations of gifted and talented students at a senior level or at a junior level?

ND: I currently teach French from years 8 to 10. I find that it is probably a bit easier to manage expectations and cater to gifted students in the more senior levels that I teach. I think this has to do with the fact that students are generally more self-directed in their learning in years 9 and 10 rather than in the junior levels where they need more explicit direction. Older students are better able to use digital resources to help challenge themselves and extend their learning. At Academy, we currently use the Education Perfect Platform. After finishing a unit that has been set by the teacher, students can complete recommended lessons or look up units to revise a grammatical concept, learn or consolidate vocabulary or to work on a particular skill, whether that be reading, listening, writing or speaking.

Having said that, students in the younger levels are generally more motivated and willing to participate in speaking in the target language in front of the class. It’s always a challenge to encourage gifted students who are not comfortable making mistakes to realise that it is part of the process of learning a language.

Vision: Over your time at Academy, you have seen some of your gifted students progress from junior levels to VCE. How have your expectations of them changed?

ND: Whilst I don’t teach VCE, I follow the progress of these students in VCE as I work closely with the senior French teacher. Generally, our expectations don’t change. We want these students to work to their potential and to be invested and motivated in their learning. These students are expected to respond in spoken and written form with greater depth than their peers and to continually challenge themselves. Language learning naturally lends itself to catering for gifted students. Students often have to use critical thinking skills in interpretive communication, they use creative thinking in presentational

communication and interpersonal communication is open ended, as students do not know the questions that their examiner will ask. Gifted students often find this oral component the most challenging. It is for this reason that at Academy, students have the benefit of a session with a language assistant once a week. Students are encouraged to make full use of these opportunities and to be prepared for these sessions. Gifted students in particular relish this opportunity to communicate in the language that they are learning on a weekly basis.

Vision: And how have their expectations of themselves changed?

ND: I think students who start off with high expectations usually carry this through their schooling years. The challenge, particularly in language learning, is for those high achieving students to extend themselves by listening to, reading and viewing the target language outside of the classroom. There are only so many contact hours at school. A considerable amount of time at home needs to be dedicated to consolidation, revision and language practice.

Vision: Let’s consider the languages classroom. What do you think the most attractive aspects of the French curriculum are for a gifted French student at junior level, say, Years 7-9? How do you expect your gifted students to engage with the material?

ND: Languages can be demanding as assessments are all skill based with a focus on writing, speaking, listening and reading in the target language. I think that gifted students can thrive on this academic challenge in years 7-9. They are able to practise different skills and can be more engaged as they tackle abstract concepts such as gender in language. Students love to make links between the French language and culture and their own.

There are so many skills involved in preparing a role play for example, and it is in these types of tasks, that gifted students are given the opportunity to shine. They have a real sense of achievement in collaborating with a partner, writing a script and then presenting to the class. They will often look up more complex vocabulary and sentence structures, ask whether they are able to add extra elements to their script, utilize digital resources to practise pronunciation and generally take ownership of their own learning. It’s very satisfying as a teacher to see the final product.

Vision: And senior, Years 10-12?

ND: Language learning in VCE becomes progressively more difficult and it requires a great deal of commitment and dedication. Most students don’t have the opportunity to use the language in their daily life, so to become proficient, time needs to be dedicated to memorising vocabulary, phrases and conjugating verbs so that they are able to speak the language proficiently and adapt different text types to different audiences in their writing.

Vision: In Victoria, most foreign languages are scaled quite highly in the VCE, rendering them attractive to students aiming

VISION, Volume 34 No. 1 2023

Interview

18

for a high ATAR. Do you think this scaling has much of an impact on students’ choice to study another language?

ND: Language learning is a complex task, and it is for this reason that the VCAA awards bonus marks to students who choose to study a language. I think that students do have this in mind when choosing to study a language as language learning does require a time commitment. Scaling is the payoff for all the hard work and dedication involved in becoming proficient in a language.

Vision: Just returning to student expectations. Do you think that experiencing educational travel might change a gifted student’s expectation of themselves and if so, why?

ND: There has been a hiatus on travel over the past few years with COVID. But hopefully we will be starting up trips in the near future. I would definitely recommend educational travel as we all know travel broadens the horizons and there is no better way to learn a language than in country experience! It can be extremely satisfying for a student who has dedicated years to learning a language, to be able to do something simple like order food in a restaurant. Through travel, students are able to immerse themselves in the culture and to demonstrate their learning and apply it to real life. The whole purpose of learning a language after all is to be able to communicate and the most authentic feedback is being able to converse with a native speaker and to be understood. Travel is something that gifted students not only benefit from but find extremely enriching. Through travel, students are able to experience

being outside of their comfort zones when they are often used to easy success in the classroom. This can be both challenging and thrilling and sometimes a student may have to readjust their expectations of themselves and what success actually looks like. More than anything, travel can be a great motivator for learning a language as the ability to communicate is so tangible.

Vision: Thanks for your time, Natalie.

Natalie Dickson is currently Head of Languages at the Academy of Mary Immaculate, Fitzroy, teaching French. She graduated in Arts from the University of Melbourne in 2007 with a double major in French and English Literary Studies. In 2010, while teaching at Loyola College, Natalie was awarded an Endeavour Languages Teacher Fellowship, a study program which comprised three weeks of intensive language and cultural study, including fi eld trips and a twoweek language course at CAVILAM University in Vichy. Since Natalie’s arrival at Academy, she has chaperoned a student study tour to Paris and an exchange program in Avignon and the south of France. She is a member of the Association of French Teachers in Victoria and Alliance Française.

Student Voice Expectations

I always thought of myself as being academically average amongst my peers, yet in my more recent years, it has come to my attention that I am slightly more above standard than I once thought. Originally, I just considered my higher marks as a personal achievement. Those who looked at my work always told me how amazing it was and without my own realisation as to why, I started to feel the burden of expectation. These pressing wants for outstanding works in my writing made me doubt myself a lot, to the point where I lost confidence in myself, but I did eventually find a way to handle the problem. By dedicating much time to my work (including lots of reading), being resilient, and pondering a lot on what I have done, I was able to get over the nerves of my work quality.

Entering high school has certainly been an experience. As someone who grew up in a town secluded from any large cities or schools, I never truly thought about all the other people that exist in the world we live in. At the start of the year, I began doubting my abilities after

seeing the capabilities of my new peers, but I eventually realised I shouldn’t care about how good other’s work is in comparison to mine. If I’m going to top any work, it will be my own.

Outside of school I play netball and train once a week. The benefit of playing a sport is I don’t need to be constantly thinking about my schooling and I can have a break from my homework for an hour. It doesn’t seem like much, but it helps a lot and has been incredibly beneficial to handling the stress of my education.

Managing expectations, it can be a difficult thing. However, what is important is that I aim high and work hard, but it is only done, once it satisfies me.

Mary Peripetsakis, Year 7, St John’s College Preston

VISION, Volume 34 No. 1 2023

19

Mary Peripetsakis

Marisa Soto-Harrison, Ed.D Expectations and Gifted Children

G IFTED CHILDREN TYPICALLY HAVE EXTRAORDINARY INTELLECTUAL ABILITIES As such, they face high expectations from their families, teachers, peers, and society. Expectations can be positive and negative, significantly impacting a gifted child’s development and well-being. Some gifted children thrive under high expectations, often excelling academically and socially. They enjoy stimulation and thrive when given opportunities to explore new ideas. These children excel when they are encouraged to pursue their passions. For others, high expectations create overwhelming stress and anxiety. Gifted children may feel pressure to perform at extremely high levels, and they might experience frustration when they do not receive the appropriate support and guidance to meet expectations.

One common expectation is that gifted children will consistently achieve at high levels. This expectation places pressure on a child or adolescent to constantly excel, leading to feelings of anxiety or stress. Another expectation is that gifted children will demonstrate high levels of maturity and emotional intelligence. However, gifted children often struggle with issues such as perfectionism, social anxiety, and depression. Parents and educators need to recognize the importance of supporting gifted children’s social and emotional developmental needs, as well as their intellectual ones.

Reasonable expectations can motivate and challenge gifted children. However, negative expectations, such as pressuring a child to perform at high levels and failing to recognize other important developmental areas, can have adverse outcomes, such as mental health struggles, rebellious attitudes, social difficulties, and low motivation, resulting in underachievement.

Research Background

In early 2020, Soto-Harrison conducted a qualitative study focusing on underachievement in profoundly gifted adolescents. The researcher explored the experiences of several underachieving adolescents through in-depth interviews with highly intelligent young adults and their parents. There is little research related to this subpopulation of gifted individuals: the profoundly gifted with IQs at the 99.9th percentile. Thus, further inquiry is necessary to better understand the factors leading to underachievement. Data analysis indicated five common themes: expectations (internal and external), social expectations/ issues, rebellious attitudes, low motivation, and mental health issues. Expectations emerged as the major contributor to underachievement.

Major themes

Interview questions posed to participants focused on the reflections of profoundly gifted young adults regarding their personal development and their perceptions of barriers and supports to their achievement. Expectations emerged as the major contributing factor among the five significant factors leading to underachievement. Data analysis showed that perceived and real expectations created pressures on profoundly gifted adolescents which impacted the social aspects of their lives, their psychological well-being, and their responses to expectations imposed on them by others (Soto-Harrison, 2020).

A. Expectations (Internal and External)

“I felt massive amounts of pressure [in] everything that I showed interest in that [might] have showed any potential for a career, anything that would make money…like being good at playing piano, it would be suggested that I play Carnegie Hall some-day.”

Research indicates that external expectations could cause troubling inner experiences. Highly intelligent individuals are driven by their interests and very often resent expectations set by others (Silverman, 2013). Soto-Harrison (2020) found that unhealthy and unwanted expectations create internal difficulties, which could create painful experiences of anxiety, depression, rebellion, and loneliness. Profoundly gifted individuals are of ten highly intense individuals, who tend to internalize expectations.

“Over time, I was frustrated because I felt that I was capable of more, but I was never able to reach my goal…I became more aware of the fact that I was supposed to be able to achieve more, and that was not the reality I was experiencing at all. If I am so smart, then why is this so impossible for me?”

All of the young adults interviewed reflected on the expectations that they set for themselves. They indicated that they had internal expectations for what they felt was most important. These were authentic and unique expectations because they showed what each of them personally valued (Soto-Harrison, 2020).

B. Social Expectations/Issues

“It was extremely frustrating to not know how to or what to talk to people about…without social experiences, it became very clear that no matter how smart you are, if you don’t know how to be a person, you’re just not going to succeed at school”.

Profoundly gifted youth often misunderstand social expectations, leaving them particularly vulnerable to having others rejoice in their misfortune (Falck, 2020). Profoundly gifted individuals frequently report feeling different, leading to disappointment, loneliness, and a lack of connectedness with others (Webb, 2013). They might be confused about how to interact with their peers. Many feel different from their peers and frequently feel the sting of rejection without knowing how to change that. Suffering rejection from peers creates the perception of being in some way deficient.

Soto-Harrison (2020) found that inadequate opportunities to interact and develop critical interpersonal skills often result in underdeveloped social skills. As a result, limited social experiences could lead to negative experiences. The reality of being out of sync with peers and feeling misunderstood becomes a constant internal battle. It is critical to recognize the need for social skills. Typically, parents and educators focus on providing challenging academic experiences, when for some profoundly gifted adolescents, social relationships are equally, if not more, important than academics.

C. Mental Health Effects/Issues

“My anxiety got so bad that it [kept] me from going to school. I ended up missing so much school that I couldn’t catch up, and my grades started to fall. I almost didn’t graduate because I had missed

VISION, Volume 34 No. 1 2023

Keynote

Resource

20

VISION, Volume 34 No. 1 2023

21

Figure 1. National Association for Gifted Children (NAGC), November 2021. Soto-Harrison, M.,Underachieving Profoundly Gifted Adolescents

so much school. I just [couldn’t] manage the anxiety.”

The effects of social difficulties can include debilitating mental health struggles. Socially difficult experiences for profoundly gifted individuals are painful and, over time, a lack of belonging has psychological impacts (Falck, 2020). Soto-Harrison (2020) found that mental health challenges can arise for various reasons, and that expectations and social difficulties directly impact mental health. Feelings of being different, misunderstood, and out of sync with others’ expectations can be confusing. Social expectations are challenging for profoundly gifted youth to satisfy. When they are unsuccessful, the emotional pain might result in mental health challenges, such as depression and anxiety.

D. Rebellious Attitudes