JHEOURNAL 2024

FROM THE HEADMASTER

Hampton Court is the self-proclaimed “most famous maze in the world”, and justifiably so. It is the UK’s oldest surviving hedge maze; it was commissioned around 1700 by William III and covers an impressive third of an acre. All visitors start from the same place and then through a series of personal choices make their way to their destination: different pathways, shared goal. As I read through The Journal it is the rich diversity of the subject matter which particularly resonates for me. Articles focus equally on STEM as well as the Arts and Humanities. They range from the downfall of the Parisian suburbs to attitudes towards China, from the influence of Classics on white supremacy to a case study of Google and Amazon from an Economics perspective, from the rise of smart cities to hypersonic missiles, from machine learning to the rise of obesogens or pain processing in the spinal cord.

At the RGS we genuinely and passionately believe in our philosophy of Scholarship for All; every single student has considerable potential, every single student enters the maze. It is, however, the next steps that fascinate me. Our students are not steered in just one direction. Rather, all our students have the same targets but the pathways they choose, the directions they take, are unique. Students at the RGS genuinely have the potential to be who they want to be; irrespective of their interests they have the opportunity to nurture and develop them. The Journal illustrates this richness beautifully.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank Mrs Tarasewicz, our Head of Scholarship, for all her hard work and inspiration in compiling this impressive publication, to Mrs Webb for designing and producing this, and – most of all – to all those students who have contributed articles which are the result of so much passion, research and reflection: different pathways, shared goal.

Dr JM Cox Headmaster

FROM THE HEAD OF SCHOLARSHIP

Welcome to the 2024 edition of The Journal. The Journal was launched as a place to celebrate some of the finest examples of scholarship produced by RGS students as they approached the end of their time with us. It was modelled upon its namesake, a typical academic journal, with essays published in full for the readers’ perusal.

For this year, I am delighted to launch a new look for The Journal. The task that we set ourselves was to create a layout that was more visually appealing than in the past, breaking up the long blocks of text with colour and visuals, but without in any way compromising the academic quality and integrity of the content. I hope that you feel that we have been successful in our aim.

Our aspiration to create a more appealing, readable Journal mirrors our wider aspirations around scholarship at the RGS. Scholarship is one of our core school values and, as such, is not something that we believe should be limited to just an elite few. We are all scholars. This belief lies at the heart of our Scholarship for All programme, which seeks to offer opportunities for enrichment and challenge to all of our students, as well as supporting them in developing the habits and values of a scholarly mindset.

In the following pages you will find full versions of Independent Learning Assignments (ILAs) and Original Research in Science (ORIS) projects produced by students during their Lower Sixth Form year. Every year, the best of these projects are shortlisted to be presented at the annual ILA/ORIS Presentation Evening, from which two winners are selected, one each in the STEM and Arts/ Humanities categories. It is these shortlisted projects that have been reproduced here. Covering topics from pain processing to historically informed musical performance, and from machine learning to the Parisian suburbs, it offers an insight into the diversity and depth of scholarship here at the RGS.

Details about other Scholarship for All initiatives and how to become involved can be found on The Hub (our intranet site for students), The Unchained Library (our external scholarship website) and the RGS Events page.

My particular thanks to Georgina Webb, our Partnerships and Publications Assistant, for her hard work in producing this year’s Journal and for helping to make our vision a reality.

Mrs HE Tarasewicz Head of Scholarship

With thanks to: Mr Dunscombe, Mr Lau, Mrs Farthing and all of the ILA supervisors for their support with the ILA and ORIS programmes.

SHREY BIJLANI

ROHAN MCCAULEY

FINLAY SANDERS

BEN TABBERNER STEM Winner Highly Commended Short-Listed Short-Listed

PAIN PROCESSING IN THE SPINAL CORD

Validating Multi-Electrode Silicon Probe Placement in the Rat Spinal Cord Using Fluorescence Microscopy for Analgesic Drug Development

SHREY BIJLANI

This report was based on an Original Research in Science (ORIS) placement at the University of Bristol and went on to win the ILA/ORIS Award in the STEM category.

ABSTRACT

The N13 potential is a response in the spinal cord in humans that is thought to reflect post-synaptic activation of neurons. Recordings from rats show the N13 potential has an analogous N1 potential in the rat and might be useful for developing new drugs, however the precise location this potential originates from remains uncorroborated. Electrophysiological experiments were performed to analyse this, and subsequently, tissue was extracted from rats and

stained accordingly. The results show that the probe was positioned approximately 1.2mm deep and 0.5mm laterally with the tip of the probe ending in lamina V. When compared to electrophysiological data, this confirms that the origin of the N13 potential is located within lamina V, supporting the conclusion that the initial response was mediated here.

INTRODUCTION

The spinal dorsal horn is organised into different lamina which are responsible for processing different aspects of sensation (Todd 2010). There are different types of peripheral neurons that respond to differential stimuli. C fibres are responsible for conveying noxious, high-intensity stimulation and synapse with neurons in laminae I and II (Todd 2010). Aβ neurons are sensitive to low-intensity stimulation such as innocuous touch and synapse with neurons in laminae III and V. Investigating the properties of these neurons in the spinal cord can provide insight into the mechanisms of analgesia for pain killers, as well as the pathology of acute and chronic pain conditions.

“ The use of rats allows for an ethically invasive exploration of the CNS as rats have a similar anatomy and physiology to humans owing to their similar spinal structure.

The human N13 potential is a measure of postsynaptic neural activity in the spinal dorsal horn and the amplitude of the N13 potential is thought to be sensitive to analgesics (Di Lionardo, Di Stefano and Leone 2021). Having measures of neural activity in the spinal cord which are sensitive to analgesics would increase our understanding of the spinal mechanisms underlying analgesia. According to prior research findings and clinical trials, it has been established that the N13 potential is modulated by Aβ neurons located in the periphery. However, the precise location within the spinal cord responsible for generating the N13 potential remains unknown and there has been no supporting evidence of the origin of the N13 potential using multi-electrode probes.

Examining the generation of the N13 potential necessitates exploration and employing rats as an experimental model is optimal for this investigation for a number of reasons. The N1 potential generated in the rat lumbar spinal dorsal horn is similar to that of the N13 potential generated in humans. The use of rats allows for an ethically invasive exploration of the CNS and rats have a similar anatomy and physiology to humans owing to their similar spinal structure. (Toossi 2021). Rats are also cost effective as they are small animals which are able to breed quickly and cheap to house.

Therefore, following electrophysiological experiments investigating the properties of the N1 potential in rats and their sensitivity to analgesics, I sought to determine where multi-electrode probes were placed in the spinal dorsal horn, whether or not these probes were placed accurately and how their positioning corresponded to collected electrophysiological data on the spinal N1 potential.

AIM

To determine the origin of the N1 potential in the rat lumbar spinal cord by validating the location of multi-electrode silicon probes with fluorescent markers.

Figure 1: Summary of the methods used as part of the study to accurately determine the location of multi-electrode silicon probes in the rat lumbar spinal cord.

OBJECTIVES

● Sectioning of the lumbar spinal cord at a constant thickness.

● Staining the resulting tissue for better microscopic visualisation.

● Using fluorescent microscopy to image the lumbar spinal cord sections which show evidence of probe markers.

● Scaling and measuring the length of the probe in the sections using vector graphics.

● Calculating the accurate location of the probes.

● Comparing the probe positions with electrophysiological data.

HYPOTHESIS

Summary of surgery and perfusion for investigation of SEPs A 1,1'-Dioctadecyl-3,3,3',3'-Tetramethylindocarbocyanine Perchlorate (DiI) fluorescent marker will show probe placement in the spinal dorsal horn in lamina I-V and the resultant images can be used to accurately confirm the origin of somatosensory evoked potentials in lamina IV-V as part of an overarching and ongoing electrophysiological study.

METHODS

Summary of surgery and perfusion for investigation of SEPs

The tissue used in this study was collected as part of an ongoing investigation of somatosensory evoked potentials in the rat lumbar spinal cord. As such, a brief summary of the methods used in the overarching electrophysiological study has been summarised below.

In isoflurane anaesthetised Wistar rats (n=60, 250-375g), a laminectomy was performed on the 13th thoracic and 1st lumbar vertebra to expose the dorsal surface of the spinal cord. The left sciatic nerve was exposed via blunt dissection and the animal was secured in spinal clamps. A bipolar Ag-AgCl stimulating electrode was hooked onto the sciatic nerve to stimulate low-intensity SEPs that mimicked protocols used in clinical trials to observe N13 potentials in humans. An acute 64-channel silicon probe (Cambridge Neurotech, UK) was inserted into the spinal dorsal horn using a micromanipulator and stereotaxic frame to record SEPs from the lumbar spinal dorsal horn. The probe was painted with a DiI stain to allow for post-hoc investigation of the probe placement using histology and fluorescent microscopy.

refrigerated at 4°C.

Data from the electrophysiological experiments were analysed in MATLAB R2022a using custom written code and the statistical comparisons visualised in GraphPad Prism v9.4.1. The responses of the SEPs following low-intensity stimulation were averaged and the data was extracted from each channel for the 30-minute baseline period.

Sectioning and Staining

After extraction of the spinal cord from a rat, the lumbar region was removed for sectioning using a single-edge razor blade. The DiI fluorescent probe marker (a point on the spinal cord showing where a silicon probe was previously inserted) was identified as a pink mark on the dorsal surface of the lumbar spinal cord and the tissue was cut 2mm either side of this mark.

Baseline responses to low-intensity stimulation were recorded for 30 minutes before either a vehicle or drug solution was administered (1ml/ Kg, I.P. injection). Post-dose, spinal SEPs were recorded for up to 90 minutes to observe changes to the amplitude of the SEP until the experimental endpoint, at which time the animal was killed and perfused with phosphate buffered-saline (PBS). The spinal cord was removed from the vertebral column and fixed in paraformaldehyde for 24 hours before being transferred to a 30% sucrose solution and

Figure 2: Mounted slide. 24 spinal cord sections from the lumbar region at a 50μm thickness. Sections with a fluorescent probe marker have a pink mark and the section where the probe marker is the deepest is shown in a red box. The section has been enlarged and shown as a brightfield image.

The spinal cord was sectioned using a freezing microtome. The spinal cord was positioned onto a cooling Peltier using Cryomatrix embedding solution with the rostral end of the cord directed vertically upwards. The Peltier began to cool to approximately -20°C. Additional Cryomatrix was added on top of and around the spinal tissue to secure its vertical position during the freezing process.

3: Chemical structure of 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Produces fluorescence given by minor groove binding and intercalation in the DNA pocket in preference to adenine-thymine clusters.

It was important that the length of the spinal cord was not much longer than 4mm, ensuring that the Cryomatrix would freeze on top of the spinal cord. Once the Cryomatrix was frozen (forming an opaque white solid), a sharp blade was attached to the microtome and adjustments to the blade’s height were made to match the height of the Cryomatrix around the spinal cord. 50μm sections were then cut manually and individually transferred to wells filled with PBS in a microtitre plate using a thin paintbrush. As a buffer solution, PBS has a similar ion concentration, pH and osmolarity to that of biological tissue, preventing sections from becoming either turgid or flaccid. On completion of tissue sectioning, microtitre plates were covered with aluminium foil and refrigerated. Aluminium foil was used to ensure that the DiI stain maintained its fluorescence, which would be otherwise compromised in the presence of light.

Prior to the mounting process, it was essential to identify a critical area within the sections. This refers to a group of sections where the probe marker can be identified, highlighted as a pink line by the DiI stain. Once identified, sections were mounted in series onto 25mm × 75mm × 1mm microscope slides (Epredia Superfrost, UK) according to a prescribed ratio: sections outside the critical area were mounted at a 1:5 ratio, while sections within the critical area were mounted at a 1:1 ratio.

Approximately 24 sections were mounted on a single slide. This was achieved by dipping the sections in distilled water to wash excess PBS solution from the surface of the section and transferring them to a slide using a thin paint brush. Washing in distilled water is vital in preventing the solidification and build-up of salt around the section on the microscope slide. Once all sections were mounted in this way, the slides were kept in darkness at ambient conditions for 24 hours.

Once the mounted sections were dry, they were stained using 300nM 4′,6-diamidino-2phenylindole (DAPI), a fluorescent stain that binds strongly to adenine–thymine-rich regions in DNA to highlightneuronal cell bodies which appear blue under ultraviolet light. 200μm of DAPI was added to each slide using a pipette and spread across the slide, ensuring that all sections was fully covered. The sections were left to stain in darkness for approximately 5 minutes and excess stain was washed off in a slide bath. They were then left to dry for 1 hour in an incubator at approximately 37°C. Once dry, 3-4 drops of Fluorsave reagent was added onto each slide using a pipette and a 24mm × 50mm coverslip was placed on top. If air bubbles were present on a particular slide, the pointed tip of tweezers were used to tease the bubbles away from the sections, allowing for a clearer final image.

Figure

Bioimaging and Microscopy

All slides were initially visualised under a Leica DM 4000B fluorescent microscope (Leica Camera, Wetzlar Germany) at a 5× magnification. An ultraviolet filter was used to show the DAPI staining of neuronal cell bodies, and a green chromatic filter was used to produce a bright red fluorescence in areas of high DiI concentration, thus confirming whether or not a probe marker was present. After identifying a single section per spinal cord that showed the brightest DiI red fluorescence, the slides were scanned at a high resolution on an Olympus Slideview VS200 Slide Scanner (Olympus Microscopy, Japan).

Image Analysis

Once scanned, the microscope slides were digitised as tiff files and initially appeared in greyscale, showing the binary intensity of fluorescence for each particular stain. To better visualise the fluorescent marker, FIJI, an open-source image processing program (LOCI, University of Wisconsin), was used to merge the blue colour channel (highlighting the

5: Output image after running the macro instruction. A single lumbar spinal cord section at a 50μm thickness under a fluorescent microscope showing a white line providing the angle of probe insertion and estimated probe depth.

neuronal cell bodies of the section) with the red colour channel (highlighting the area where the probe was inserted) to create an overlaid image.

To determine the probe position in sections with probe markers present, a macro instruction was created. It described a threshold value that established a limit after which no more fluorescence was detected. The macro also described drawing an elliptical region around the fluorescent area of the image, quantified by the threshold value, and then drawing a line connecting the two most distant points within this ellipse. This process yields two key pieces of information: the length of the fluorescence within a particular section (and therefore an estimate for the depth of the probe), and the angle at which the probe was likely inserted.

Figure 4: Using FIJI to create an overlaid image. A single spinal cord section from the lumbar region at a 50μm thickness under a fluorescent and brightfield microscope showing the relative probe position. A. Brightfield image. B. Yellow light fluorescence appearing as greyscale. C. Ultraviolet light fluorescence appearing as greyscale. D. Merged colour image with neuronal cell bodies in blue highlighted by the DAPI stain and the area of probe insertion in red highlighted by the DiI stain.

The final step in the image analysis was to perform accurate measurements determining the precise position of the probe within the lumbar spinal cord section using Inkscape, an open-source vector graphics editor.

Figure

To perform the calculations of the probe position, multiple additional images were uploaded to Inkscape as individual layers, including the original overlaid image (Figure 4, D), the output image from the macro instruction (Figure 5) and an image of the multi-electrode silicon probe. Calculations were performed to scale the initial size of the probe in Inkscape to the appropriate size.

Below is an example of how the depth of the probe was calculated from the top of the cross-section using Inkscape:

RESULTS

The results of this report show the identification of multi-electrode silicon probes inserted into the spinal dorsal horn to record somatosensory evoked potentials.

The measurements in Table 1 were recorded during the electrophysiology experiment using a micromanipulator to identify where the probe was positioned in the rat lumbar spinal cord. They all show a rostral-caudal measurement of -7mm, a medial-lateral measurement of -0.3mm and a dorsalventral measurement of -1.0mm from the T12-T13 vertebral boundary.

Table 1 The rostral-caudal, medial-lateral and dorsal-ventral probe positions in 5 rat lumbar spinal cords.

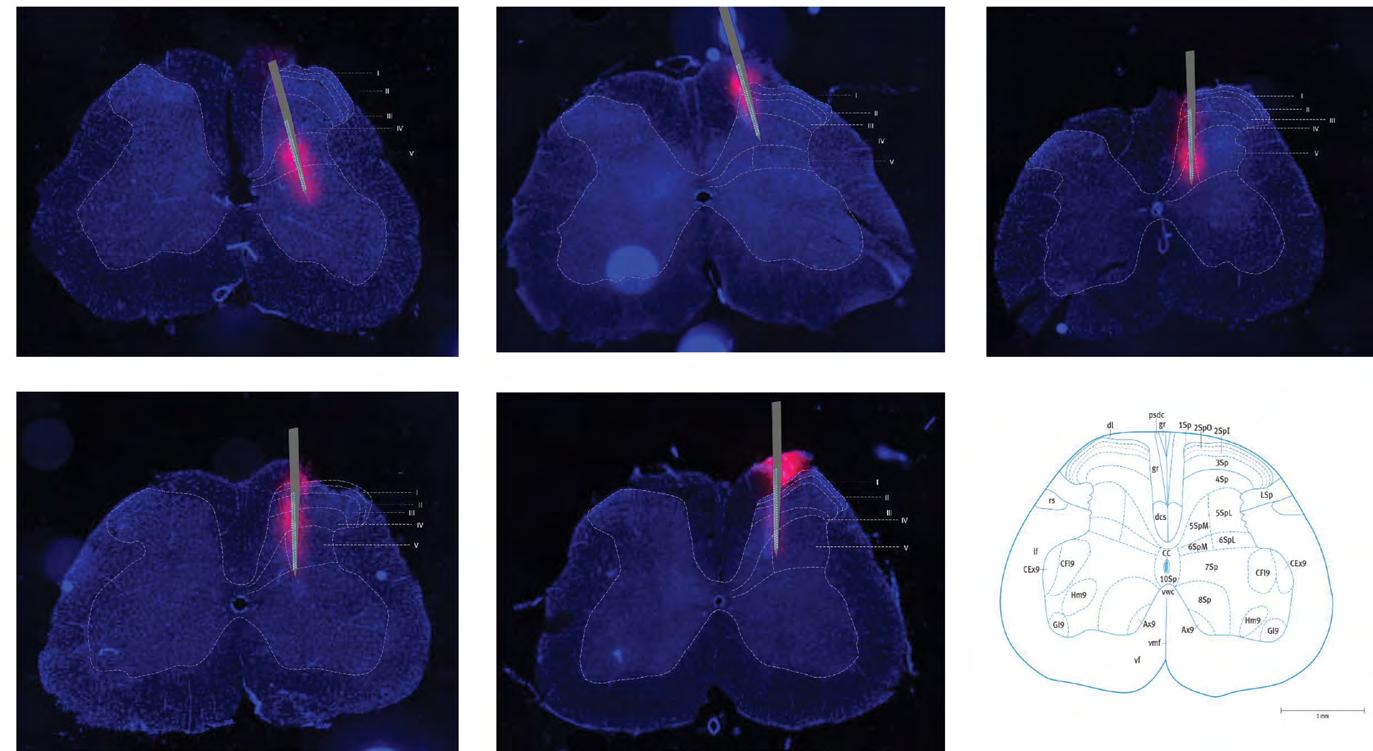

Figure 6 Final images produced using Inkscape vector graphics. 5 spinal cord sections from the lumbar region at a 50μm thickness under a fluorescent microscope with an animal ID showing the relative probe position as compared to the structure of an L5 rat spinal cross-section. Neuronal cell bodies in blue highlighted by the DAPI stain and the area of probe insertion in red highlighted by the DiI stain.

Table 2: Means and standard deviations of probe placement in the spinal dorsal horn. Major axis length: length of fluorescence produced by the macro instruction. Probe depth: depth of the probe from the top of the section. Medial-lateral: Horizontal deviation of the probe from the middle of the section. Orientation: Angle at which the probe was inserted taken counter-clockwise from the horizontal. Lamina: Shows the lamina number in which the probe tips reached.

“ These results can be used to accurately confirm the position of the probes when used in conjunction with the electrophysiological data.

Values for the probe positions in sections A-E were calculated using Inkscape and the means and standard deviations for the measurements are shown in Table 2. Individual measurements for the probe depth are represented in Graph 1 below. These results can be used to accurately confirm the position of the probes when used in conjunction with the electrophysiological data.

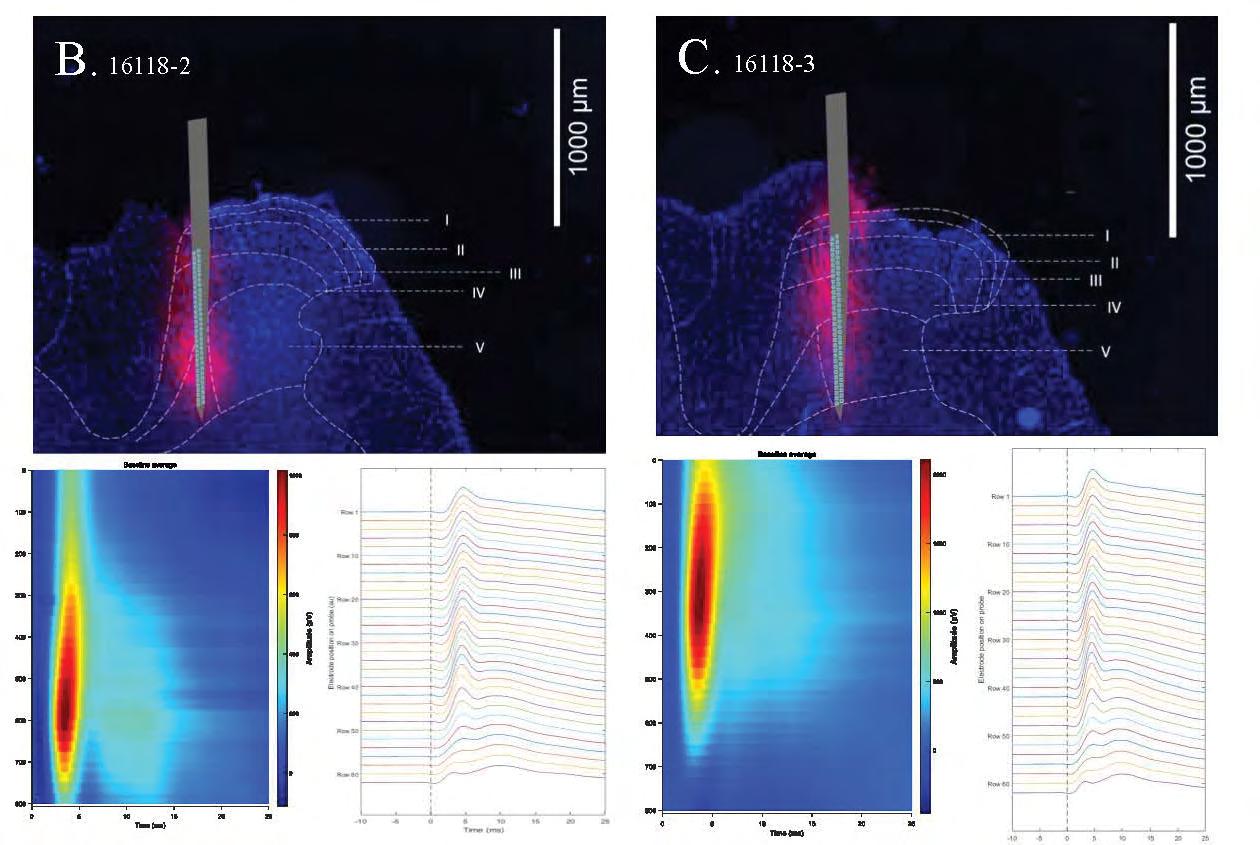

Figure 7 shows 3 of the 5 sections where the corresponding electrophysiological data was provided. Each image consists of an Inkscape image showing the individual electrode sites on the surface of the probe, a heat map showing amplitude against time in a colour chart to display where the peak is, and an SEP waveform showing the shape of the signal over time, emphasising the N1 potential. In addition, other slower conducting peaks are shown on the heat map in light blue.

Graph 1: Bar chart showing the values of the depth of the probe in five rat lumbar spinal cord sections. Mean value of probe depth is shown by the blue bar, standard deviation is shown by the thin black bar with measurements of each individual probe depth plotted vertically as red dots.

Figure 7: Comparing probe placements with electrophysiological data. A heat map showing the amplitude of signal and latency, and a waveforms graph showing the electrode channels where electrical activity is recorded are presented alongside 3 images produced on Inkscape.

Across the 3 sets of data presented below, the peak responses were recorded on electrodes in rows 20 to 40 as shown on the SEP waveforms. When compared to the images created on Inkscape (Figure 6) and the probe depth measurements (Graph 1), this directly correlates to lamina IV-V in the lumbar spinal dorsal horn. However, the probe in section A has been inserted deeper which explains why the peak amplitude of the N1 potential is recorded towards the top of the probe. The peak amplitude in recorded in sections B and C is more central as the probe is shallower in the spinal cord. Therefore, the N1 potential is recorded on medial channels.

DISCUSSION

Experimental procedure and wet lab techniques used to obtain the final results had to be regularly assessed and modified, and were not without its limitations. Having started off with a total of 9 spinal cords, only the sections from 5 spinal cords were usable as part of the study. Some spinal cords became especially fragile having been perfused from the rat vertebral column and were unable to be sectioned. Of those that were, many sections became damaged while using the freezing microtome, including those showing evidence of fluorescent probe markers. Furthermore, condensation on the microscope slides and coverslips after refrigeration may have been responsible for the lack of clarity of several images after being scanned.

During the sectioning process, it became clear that using a section thickness of 25μm left sections susceptible to tearing, which reduced the quality of the spinal tissue. Therefore, changes were made to the methods to increase the thickness of the sections from 25μm to 50μm. This was shown to increase their durability during the mounting process, which ensured that tissue was successfully stained and mounted while preserving the integrity and clarity of the resultant images, highlighting the significance of thickness selection in minimising tissue tears and breakages.

After mounting the first spinal cord section, I came to realise that the direction in which the sections were facing on the surface of the slide was not kept constant, resulting in the exact distance between each section being different. In order to maintain a single facing direction for all sections moving forward, I employed a simple scoring technique which involved making a shallow cut down the contralateral ventral surface of the spinal cord in advance of sectioning. When the sections were then mounted, they were placed on slides with this cut positioned on the left-hand side, allowing for the rostral end of each section to be constantly directed upwards. This, in turn, meant that the probe marker always appeared on the same side regardless of the section, making the microscope images more accurate when analysing. However, introducing an additional cut to sections made it difficult to mount onto microscope slides and some were damaged.

The rat spinal cord perfused from the vertebral column in a dish of 30% sucrose solution with peripheral nerves branching out from the cord.

The fluorescent dye successfully stained the position of the probe and the cell bodies of neurons within the spinal dorsal horn across 5 rats. The anatomical features of the sections identified with DiI fluorescence closely match those of lamina V of the spinal cord, confirming the expectations of the electrophysiology. Figure 6 also shows a similarity regarding the shape and size of the sections. This holds true when compared to the cross-sectional image of the rat L5 spinal cord from the rat spinal cord atlas, especially with regards to the shape of the grey and white matter.

By considering Table 2, it can be deduced that the major axis length provided by the macro instruction served solely as an estimate for probe depth, where the length of the fluorescence was notably larger than the depth of the probe calculated using Inkscape. This may suggest a possible limitation in using computation to define a region of fluorescence

based on a single threshold value used across all 5 sections. Therefore, fluorescence would be better used as a visual indicator of probe position rather than a quantitative value which serves to estimate probe depth. It is worth noting that the DiI stain which gives rise to fluorescence under the microscope may have diffused through the spinal tissue to a certain extent, further undermining the values for major axis length in reflecting probe depth. A similarly large discrepancy can be seen when comparing the mean medial-lateral value in Table 2 to the medial-lateral values in Table 1. It is now clear that the reason for this was due to the fact that measurements obtained using the micromanipulator were taken from the left hand side of the central vessel instead of the midline of the spinal cord as done on Inkscape. This would have accounted for the difference of approximately 200μm between the two results.

The measurement of the depth of the probe recorded in Table 2 showed a strong similarity to the dorsal-ventral position calculated as part of the electrophysiology in Table 1. A minor difference between the two may be due to the inclusion of the result obtained from section A in Figure 6. While he depth of the probe in section A was deeper compared to sections B, C and D, this result is clearly reflected in the electrophysiological data shown in Figure 7. Similarly, the value of orientation is important in showing that the probe insertions across all 5 sections were similar and inserted nearly perpendicularly. However, insertion at an angle may have caused a greater number of electrodes to be present in certain lamina compared to others.

“ This study has contributed to the understanding of the origin of the N13 potential.

Analysis of features of the electrophysiological data show that the N13 peak has a latency of less than 5ms and an average maximum amplitude of over 1000μV. This this suggests that the observed phenomena are the result of post-synaptic neural activity in the spinal dorsal horn to an Aβ-mediated response. Aβ primary afferent neurons conduct sensory information at velocities less than 100ms which matches the time course of the evoked response here. Moreover, these results show that the origin of spinal SEPs occurs in laminae IV-V of the spinal dorsal horn, which is expected because Aβ fibres form synapses with neurons in laminae III-V. The data in Figure 7 also shows a second peak in the heatmaps and waveform plots, suggesting a second component of the SEP which could reflect the activation of slower conducting peripheral neurons or activation of second order neurons in the spinal

cord. It is thought that these wide dynamic range (WDR) neurons, which respond to both painful and innocuous touch, contribute to the generation of the N13 potential in rodents and humans (Di Pietro, Di Stefano and al. 2021). The electrophysiological data proposes that WDR neurons may contribute to the generation of SEPs in the spinal dorsal horn which in turn may be sensitive to analgesics such as Tapentadol. More work, including single unit analysis of this data, is needed to understand which spinal neurons are responsible for the generation of the N13 potentials. However, this study has contributed to the understanding of the origin of the N13 potential in rat, which has important ramifications for ongoing studies that investigate the N13 potential as a biomarker of analgesic drug discovery.

After constructing images of the 5 sections in Figure 6, corresponding electrophysiological data was unavailable for all 5 recordings. 2 of the 5 recordings were discounted from the analysis pipeline and these figures were not pursued. This was likely because of dirt on the stimulating or recording equipment. However, it is worth noting the placement of the probe in both section B and E (Figure 6). The value for the depth of the probe in section B is very low compared to the other 4 sections and the majority of the electrodes lie between lamina I-III. In section E on the other hand, the probe tip ends in lamina V as originally planned and the majority of the electrodes on the probe lie between lamina III-V. We can therefore expect the electrophysiological data corresponding to section E to be similar to sections B and C in Figure 7.

CONCLUSION

This study has validated the position of probes in the spinal dorsal horn with DiI fluorescent probe markers using a range techniques within histology, bioimaging and vector graphics. This serves to contribute to a wider study where multi-electrode electrophysiology has been used to show where the N1 potential is generated in rats for the first time, providing the groundwork for novel testing of analgesics on patients suffering from chronic pain. This has important implications for understanding the generator of the human N13 potential and future analgesic drug development. Nevertheless, further investigation of the N13 potential in humans and the N1 potential in rats is needed, and future studies should use lamina-specific markers to more clearly identify anatomical landmarks to assist with the tissue analysis.

An image taken from Inkscape showing how lines and shapes were used to calculate the depth of the probe.

Experimental set-up for electrophysiological experiments on rats using electrodes to monitor and record electrical activity.

LITERATURE CITED

1. Di Lionardo, A, Di Stefano, G and Leone C et al. Modulation of the N13 component of the somatosensory evoked potentials in an experimental model of central sensitization in humans. Sci Rep, 2021.

2. Di Pietro, G, Di Stefano, G, and Leone C et al. The N13 spinal component of somatosensory evoked potentials is modulated by heterotopic noxious conditioning stimulation suggesting an involvement of spinal wide dynamic range neurons. Neurophysiol Clin., 2021: 517-523.

3. Todd, A.J. Neuronal circuitry for pain processing in the dorsal horn. Nat Rev Neurosci., 2010: 823-836.

4. Toossi, A., Bergin, B., Marefatallah, M. et al. Comparative neuroanatomy of the lumbosacral spinal cord of the rat, cat, pig, monkey, and human. Sci Rep, 2021.

5. Watson C, Paxinos G, Kayalioglu G, Heise C. Chapter 15 - Atlas of the Rat Spinal Cord. The Spinal Cord, 2009: 238-306.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I extend my formal appreciation to the following individuals and facilities for their contributions to this project. Kenneth Steel for the day-to-day supervision and experimental planning, Dr Tony Blockeel for his expertise of somatosensory evoked potentials and Professor Tony Pickering for his support in securing my research project. I also thank the Histology Services Unit for granting access to their freezing microtome and the Wolfson Bioimaging Facility, particularly Katy Jepson for granting access to the Olympus Slideview VS200 Slide Scanner and Dr Stephen Cross for helping to develop the macro instruction. Their collective efforts greatly facilitated the success of this study.

THE RISE OF OBESOGENS

Could synthetic chemicals be the hidden catalysts of the obesity epidemic?

STEM ROHAN

M C CAULEY

This Independent Learning Assignment (ILA) was highly commended at the ILA/ ORIS Presentation Evening.

ABSTRACT

Obesity is a huge problem in both the developed and developing world. Rapidly rising levels of obesity mean that every year, a greater proportion of the population is at risk from diseases such as type II diabetes and various cardiovascular disorders. My ILA aims to explore the role of obesogens, endocrine-disrupting chemicals that contribute to obesity, by examining their impact on factors such as adipocyte differentiation and Appetite control which lead to weight gain. Understanding obesogens is crucial for effective policy-making and prevention strategies, although it is evident that factors such as diet and exercise are ultimately more significant, and that tackling the obesity epidemic is an incredibly complex issue which requires the consideration of a broad variety of contributing factors.

INTRODUCTION

An Overview of the Obesity Epidemic

In 1997, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared obesity to be a global epidemic1

Since then, numbers have only continued to rise increasingly rapidly. The largest observed increase has been in the US; National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) have found that the proportion of obese adults in the age range 20-74 has increased from around 14.5% of the population in the period 1976-19802 to 30.5% in the period 1999-20003 - an increase of approximately 110% in only around 20 years. As of 2018, the figure sits at around 42.8%, and by 2030, just under half of all US adults are expected to be of obese weight status4

“ Rapidly rising levels of obesity mean that every year, a greater proportion of the population is at risk from diseases such as type II diabetes and various cardiovascular disorders.

The commonly proposed reason for this astronomic increase, and a fixture of the health and wellness industries, is the concept of ‘calories in, calories out’. On the surface, this model of weight gain has its merits - as diets and, more broadly, lifestyles, have shifted in the developed world to favour energy consumption over expenditure, so too has the incidence of obesity dramatically increased5. At the same time, this concept is insufficient as it massively simplifies a problem rooted within a complex spectrum of socioeconomic factors, belying a huge range of confounding variables such as the quality of those calories consumed as well as a demographic’s access (or lack thereof) to good quality food.

It would also be wrong to assume that this problem is limited to developed countries. Whilst the prevalence of obesity is generally lower across African and South East Asian countries, more recent trends show that the mean body mass index (BMI) in many of these developing countries is on a sharp rise, and with it, the proportion of adults and children that are obese6,7. A case study in The Gambia published in 2020 found that obesity rates in Gambians aged 16 years and over had increased from an estimated

2% in 1996, to a prevalence of 8% in men and 17% in women in recent years, particularly in urban areas8. This global rise is of huge concern as there are well-established links between obesity and a huge range of further health complications. Obese individuals are more likely to suffer from a wide range of health complications including (but not limited to): type 2 diabetes; coronary heart disease, heart failure and strokes; respiratory problems such as asthma; weakened immune systems; cancer; and kidney disease9. This comes not only at a great personal cost for the sufferer, but also as an extreme burden on health services globally - as of 2014, the estimated annual cost of obesity sits at around two trillion dollars, due to the direct costs of healthcare as well as the indirect costs of lost economic productivity10,11 . It seems clear that as we have transitioned to an increasingly automatised and sedentary lifestyle, and as the volume of readily available, high-calorie food has increased, the prevalence of obesity has followed suit. However, the question remains; within the complex web of factors and variables responsible for the expansion of this epidemic, could one comparatively inconspicuous factor be driving the increase at an ever faster rate?

INTRODUCTION TO OBESOGENS

An endocrine-disrupting chemical (EDC), also called an endocrine disruptor, is any chemical, natural or artificial, that can interfere with the endocrine system, usually by mimicking or blocking the action of the body’s own hormones12,13. Just under 1500 potential EDCs have been classified14, and these come from a wide variety of sources, including pesticides, flame retardants, cosmetics, and compounds used to produce plastics.

The possibility that EDCs may be able to promote obesity in humans was first hypothesised in 2002 by Dr Paula Baillie-Hamilton15,16, and in 2006 the term ‘obesogen’ was coined in a paper published by Felix Grün and Bruce Blumberg to describe such a molecule. In the paper, Grün and Blumberg define obesogens as “molecules that inappropriately regulate lipid metabolism and adipogenesis to promote obesity”17. In other words, they are substances that promote the differentiation and proliferation of white adipose tissue responsible for the characteristic weight gain seen in obesity.

White adipose tissue (WAT) is made up of white adipocytes, cells responsible for the storage of energy as triglycerides. When the body’s energy expenditure requirements outweigh its energy intake, the adipocytes break down the triglyceride store via lipolysis, releasing free fatty acids which can be oxidised readily for the production of large amounts of ATP18.

Much of the WAT is subcutaneous, meaning it is stored under the skin. This allows it to act not only as an energy store but also as heat insulation and a protective buffer against impact. WAT is also present as visceral adipose tissue, which is packed around the intraabdominal organs such as the stomach, intestines, and kidneys20. However, problems can arise when these cells proliferate too expansively, either through an increase in adipocyte number, called hyperplasia, or an increase in the size of individual adipocytes, hypertrophy21. The storage capacity of the subcutaneous WAT, the largest depot of adipose tissue, is limited. This means that excess adipose tissue accumulation increases the load of the visceral adipose tissue, and can also lead to fat accumulation in abnormal areas, such as in excessive quantities around the liver and heart21. A potential consequence of this is the accumulation of toxic lipid

compounds in non-adipose tissue which can lead to cellular dysfunction and in some cases cell death, a condition known as lipotoxicity22

Furthermore, it has been observed that the proliferation of WAT induces a dangerous inflammatory response23. In 1994, the discovery of leptin, a hormone secreted by adipose tissue24 revealed that WAT functions not only as a storage tissue, but also as an active endocrine organ, and in addition to the wide variety of cytokines, hormones, and other products secreted by WAT (jointly referred to as ‘adipokines’), when under stress - as they are in the case of obesity - adipocytes secrete inflammatory mediators and chemoattractants such as monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1)25. These attract and recruit macrophages to the tissue, which themselves secrete, among other things, tumour necrosis factor (TNF-α), a cytokine (also secreted in smaller quantities by stressed WAT) that promotes an inflammatory response, perpetuating the process26,27 . However TNF-α also promotes the phosphorylation of serine, an amino acid, in the protein ‘insulin receptor substrate 1’ (IRS-1), which inactivates it and hence impairs the insulin signalling pathway28–30. The culmination of this series of events is that the cells eventually become insulin resistant. As insulin promotes the maturation and proliferation of adipocytes by stimulating triglyceride synthesis and preventing lipolysis28, the desired effect of inducing insulin resistance may be, in the case of obesity, to try and prevent further accumulation of adipose tissue. However, as discussed earlier, the amount of visceral and ectopic (abnormal) adipose tissue is greatly increased in obese individuals, meaning that important insulin-sensitive tissues, such as muscle tissue, and organs, such as the liver, are exposed to the effects of this insulin resistance as well29. As a consequence, obese individuals are at a much higher

19TEM micrograph of a white adipocyte: N is the nucleus, M the mitochondria, and L the lipid droplet

risk of developing type 2 diabetes; in the period 1999-2002, 54.8% of US type 2 diabetics were also obese, and if you include those in the overweight weight category (a BMI greater than 2531), the number rises to 85.2%32 .

From this it can be seen that obesity is characterised by an increase in adipose tissue mass and volume, and that the risk factors associated with obesity stem from this proliferation. Obesogens function by promoting the differentiation and growth of the adipocytes that make up these tissues through a number of different mechanisms, so it is clear why they should be a matter of concern.

BIOLOGICAL MECHANISMS OF OBESOGENS

How exactly do obesogens, generally simple molecules, cause the body to produce abnormal numbers of adipocytes? As a loose definition, the term obesogen encompasses a huge class of different molecules which can function in a multitude of different ways. This sections aims to discuss a few of the most common/well-researched biological mechanisms by which an obesogen may work.

3a. Nanomolar Ligand Affinity for ‘Master Regulator’ Nuclear Receptors

In the late 1960s, tributyltion (TBT), a toxic biocide, was mixed into paints to function as an effective antifouling agent for ship hulls33. Discovered in 1954 by a research group from the Netherlands34, TBT was extremely effective at preventing barnacles and other marine organisms from infesting the bottom of wooden and steel plated boats. However, the TBT slowly leached from the paint into the surrounding marine environments. Due to its relatively long half-life, particularly in anoxic marine sediments, TBT is able to accumulate in ocean floor sediments, only to be released back into the seawater, re-contaminating the area33. (To be precise, TBT is an umbrella term given to a closely related family of organotion compounds with similar characteristics – the organotion commonly used in hull paints was primarily bis(tributyltion) oxide, TBTO)

Scientists first began to notice the effects of this TBT contamination in the 1970s, when numerous marine species were observed to have developed abnormal disorders. In particular, scientists noticed a severe decline in populations of the rocky shore sea snail, Nucella Lapillus, commonly known as the dog whelk. They found that this decline was due to the masculinisation of female dog whelks, a condition known as ‘imposex’, which was induced by TBT35.

37Photographs showing the development of a penis and vas deferens in imposex female dog whelks

46Structure of the PPAR-γ receptor bound to DNA

Imposex females are characterised by the growth of a penis and vas deferens (sperm duct) which, at high enough concentrations of TBT, grew large enough to block the vulva and prevent the release of egg capsules, hence rendering the female sterile36.

Further research was carried out on TBT to try and deduce the mechanism by which this could happen, and in the early 2000s Bruce Blumberg (mentioned earlier), whilst in a meeting in Japan, heard about a research group which had found that TBT also caused masculinisation in fish38,39. Hypothesising that the TBT functioned by activating a sex steroid receptor, he conducted his own research, testing to see if TBT activated any known nuclear receptors. Instead, he found that it activated the nuclear receptor ‘peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma’ (PPAR-γ)40. Further study showed that TBT is also an agonist to retinoid X receptors, which is theorised to be the mechanism by which imposex is induced in gastropods such as the dog whelk41,42.

PPAR-γ is a nuclear receptor that is highly expressed in adipose tissue, and has been named the ‘master regulator’ - in other words, the apex, or most important, factor in a biological regulatory hierarchy - of adipogenesis, the process by which adipocytes mature from stem cells41,43. It forms a heterodimer with RXR, which when subsequently bound to a ligand, regulates the transcription of target genes. Through an increase in the mRNA expression of genes which promote fatty acid uptake and storage, and a decrease in the expression of

genes that induce lipolysis in WAT, the heterodimer stimulates the differentiation of multi potent stem cells and preadipocytes into adipocytes, in addition to increasing the size of existing adipocytes41,44,45. Therefore, obesogens such as TBT, which have a high ligand affinity for these particular nuclear receptors may be inducing obesity by acting as agonists to indirectly promote the expression of genes responsible for the differentiation and proliferation of white adipocytes. Animal studies have demonstrated that TBT induces adipogenesis in mice and frogs and that prenatal exposure has a particularly significant effect on adipose tissue accumulation, regardless of normal postpartum diet and exercise47 . Perhaps the most troubling fact to consider is that, as ligands, organotions such as TBT do not bind in a typical manner, particularly so in RXR activation. Typical RXR ligands have a carboxylic acid functional group, and mimic the structure of 9-cis-retionoic acid. TBT and its associated organotions, put simply, do not follow this trend in the slightest, but nonetheless are potent agonists to both the PPAR-γ and RXR receptors47. This strongly hints at the possibility that there are a wide range of substances and molecular structures that could have the potential to induce obesogenic effects through similar mechanisms to TBT and so, although TBT may have been the first obesogen to have been identified by Blumberg et al. in their seminal paper from 2006, it is certainly not the only one.

TOP: 48chemical structures of several typical RXR agonists; A – natural agonists; B – synthetic agonists. Note the carboxylic acid functional groups, CO2H, and broad structural similarity to 9-cis-retionoic acid (top left)

BOTTOM: the structure of bis(tributyltion) oxide, TBTO, also an RXR agonist, but atypical in terms of functional group and 3D structure

3b. Appetite and Satiety Dysregulation

The craving for a sugary snack in the middle of the night, or hunger after a long run, and conversely the feeling of fullness attained after a hefty meal stem from the same area of the brain: the arcuate nucleus (ARC). The ARC is a region of the brain responsible for Appetite and satiety49, and hence controls and maintains energy homeostasis. Neurons that stimulate Appetite, such as those that produce neuropeptide Y (NPY) and agouti-related peptide (AgRP) are said to be orexigenic; and those that inhibit satiety (i.e induce an Appetite), such as the neurons that produce pro-opiomelanocortion (POMC) and cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART), are anorexigenic50. These neurons develop prenatally in a process referred to as neurogenesis (although the occurrence of neurogenesis in adult human brains is hotly contested and is the subject of much research)51.

BPA was detected in the urine of over 92% of the participants53. Despite this, based on the current levels of BPA occurring in foods, the FDA considers BPA to be safe54 - regardless, a strong case is being made as to the endocrine-disrupting potential of BPA, and it is a strong contender on a growing list of potential obesogens.

Bisphenol A (BPA) is a synthetic compound widely used in plastic manufacturing, predominantly for the production of polycarbonate plastics and epoxy resins used to line food and beverage packaging, and has been in use since the 1960s52. Many may be familiar with it, as many household appliances and plastic products around today proudly declare themselves to be ‘BPA free’. This is due to various health concerns linked to BPA, although the presence of ‘BPA free’ products may be of little comfort - in a representative sample of the US population,

Different studies have postulated that BPA may be obesogenic through a variety of mechanisms, but one particular mechanism is through its interaction with neural progenitor cells (NPC), the precursors to neuronal cells, such as the NPY/AgRP orexigenic neurons. Studies conducted on mice suggest that prenatal BPA exposure leads to an increase in unregulated neurogenesis, altering brain structure and function55–57, and potentially disrupting the balance between Appetite stimulators and inhibitors, leading to, later in life, increased food intake and hence weight gain.

BPA is not the only compound theorised to have an impact on Appetite. For example, monosodium glutamate, or MSG for short, is a flavour enhancer that is particularly popular in Asia; recently studies have proposed that it may disrupt the secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), a hormone that, among other functions, acts in the hypothalamus to promote satiety58 - 60. Considering the socio-economic context of the obesity epidemic itself, in the majority of cases, decreased satiety and increased Appetite will lead to an increased consumption of cheap and readily available food, sacrificing the quality of the calories consumed for the volume of calories provided; and whilst this mode of action, an indirect exacerbation of the existing factors that have been driving the obesity epidemic, is much less well-researched than the mechanism discussed previously, it seems just as, if not more, worrying.

3c. The Search for New Mechanisms

The obesogen field is still a relatively novel area of research and study; around 50 obesogens have been identified so far, and the mechanisms for most of them are yet to be determined61. One growing field of interest is in a transgenerational approach to studying obesogens, as evidence suggests that certain obesogens, like TBT and BPA, can cause effects that are inherited across multiple generations62. However, gaining a better understanding of factors like the role of epigenetics - a relatively new field itself - in hereditary obesity is essential for further exploring the potential consequences of obesogens.

It is therefore important to keep in mind that, whilst much more is understood now about obesogens than when they were first discovered, there is still much to learn and so at this time, determining the relative impact of such chemicals on a global scale is, to put it mildly, difficult.

4. Epidemiological Evidence for Obesogens

ruin an epidemiological study - in the case of TBT, it was recently shown that plastic containers, widely used in studies on the prevalence of TBT in human specimens, strongly bind organotions themselves, meaning that the estimated organotion levels in the specimens from these studies was most likely significantly underestimated59,61

It may be unsurprising, therefore, that perhaps the strongest epidemiological evidence for the impact of obesogens itself predates the obesogen field.

Numerous studies have found that, whilst nicotine is an Appetite suppressor, there is a strong causal relationship between pregnant smokers and an abnormal rate of weight gain in their corresponding children once born, highlighting the consequences an EDC such as nicotine can have for the development of obesity16,63 .

“ 50 obesogens have been identified so far, and the mechanisms for most of them are yet to be determined.

Some of the mechanisms by which an obesogen may function have been discussed; however, is there sufficient epidemiological evidence to suggest they could be a leading factor in the expansion of the obesity epidemic? The global transition to a much more urbanised lifestyle for most of the developed and developing world, and the accompanying changes in diet and exercise that have followed clearly correlate with the rising trend in obesity, and so it would be perfectly reasonable to assume that, in comparison to such a huge societal shift, the effect of obesogenic chemicals would be minimal.

Unfortunately, even for TBT, the most well-researched obesogen, epidemiological studies of human TBT exposure are few and far between. This may be due to the difficulty of accurately determining gross exposure to any given chemical: the exposure may occur through multiple routes; the detected concentrations of chemicals with short half-lives will vary significantly over time; and sample contamination during the collection of data can

On the topic of childhood weight gain, trends in the prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity cannot be ignored. In the period 1980-2005, across the school-age population of 25 countries and pre-school populations of 42 countries, an increase in the prevalence of childhood overweight could be observed in almost all countries, with the only exceptions being among school-age children in Russia and Poland in the 1980s64. This is particularly significant, as the factors typically associated with the obesity crisis, particularly in the west, such as diet and a sedentary lifestyle, are not as predominant for children and infants. Generally, the extent to which one child may be more or less active than another is much less pronounced than between adults, and so this hints that there are external factors at play, especially when accounting for as sharp a rise in childhood obesity as has been observed in the past few years - in 2010, 43 million children under the age of 5 were estimated to be overweight or obese, an increase of 60% in only 20 years65,66.

Finally, although studies on obesogens in human populations are challenging to effectively carry out, model studies on animals can give researchers indicative and reliable results. Exposing mice,

rats and zebrafish to obesogens such as TBT have shown clear evidence of induced weight gain across multiple studies41,47. Whilst these animals are not perfect models, they are much closer to humans than, say, the molluscs claimed as victims by TBT. All three animals mentioned share roughly 70% of their DNA with humans67,68, and the mechanisms of adipogenesis and weight gain between these animals and humans are largely evolutionarily conserved69 Overall, it does not seem like a stretch to imply that obesogens could likely be playing a role in the accelerated epidemic of obesity.

CONCLUSION

The field of obesogens, and indeed that of EDCs in general, is still a novel area of research. Whilst it may not currently be possible to arrive at a definitive conclusion as to the magnitude of their impact, the evidence available indicates that they should be a serious cause for concern, and if we want to slow the current acceleration of the obesity epidemic, we need to carefully consider how, going forwards, the potential negative effects of such compounds can be mitigated.

Policy-making plays a crucial role in addressing the obesity epidemic and mitigating the impact of obesogens, and so governments and regulatory bodies need to prioritise the regulation and monitoring of potential obesogens in consumer products, although long-term human studies and further epidemiological research will be necessary to comprehensively assess the effects of these chemicals on human health and inform evidence-based policies.

Having said that, it also seems apparent that, if a world were to exist where all demographics had access to high quality food, frequent exercise and generally healthy lifestyles, the introduction of obesogenic chemicals at the levels present in our environment would not single-handedly fuel a global obesity epidemic. I do not believe that the evidence presented denotes that obesogens are the core drivers of the epidemic; rather, obesogens may exacerbate existing problems within urban societies, accelerating an epidemic that has its roots in a much less tangible web of factors.

For this reason, in addition to policy interventions, preventive measures should focus on promoting healthier lifestyles, including balanced diets and regular physical activity. Education and awareness campaigns can help individuals make informed choices and adopt healthier behaviours, and collaborative efforts among healthcare professionals, policymakers, food industries, and communities are essential for effective prevention and management of obesity.

In conclusion, it is clear that no single factor can be held solely culpable for the rapid global rise of obesity. Addressing the obesity epidemic requires a multi-faceted approach that considers the complex interplay of factors influencing weight gain. Understanding the role of obesogens and their mechanisms of action is pivotal in order to develop effective prevention strategies, and as more research becomes available, implementing evidence-based policies, in addition to promoting healthier lifestyles, will be crucial in order to secure a future with reduced obesity rates and improved public health.

REFERENCES

1. Haththotuwa RN, Wijeyaratne CN, Senarath U. Chapter 1 - Worldwide epidemic of obesity. In: Mahmood TA, Arulkumaran S, Chervenak FA, editors. Obesity and Obstetrics (Second Edition) [Internet]. Elsevier; 2020 [cited 2023 Jun 14]. p. 3–8. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/ B9780128179215000011

2. Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kuczmarski RJ, Johnson CL. Overweight and obesity in the United States: prevalence and trends, 1960–1994. Int J Obes. 1998 Jan;22(1):39–47.

3. Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL. Prevalence and Trends in Obesity Among US Adults, 1999-2000. JAMA. 2002 Oct 9;288(14):1723–7.

4. Li M, Gong W, Wang S, Li Z. Trends in body mass index, overweight and obesity among adults in the USA, the NHANES from 2003 to 2018: A repeat cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2022 Dec;12(12):e065425.

5. Bleich S, Cutler D, Murray C, Adams A. Why is the Developed World Obese?

6. Bhurosy T, Jeewon R. Overweight and Obesity Epidemic in Developing Countries: A Problem with Diet, Physical Activity, or Socioeconomic Status? Sci World J. 2014;2014:964236.

7. Caballero B. The Global Epidemic of Obesity: An Overview. Epidemiol Rev. 2007 Jan 1;29(1):1–5.

8. Cham B, Scholes S, Ng Fat L, Badjie O, Groce NE, Mindell JS. The silent epidemic of obesity in The Gambia: evidence from a nationwide, population-based, cross-sectional health examination survey. BMJ Open. 2020 Jun;10(6):e033882.

9. Kinlen D, Cody D, O’Shea D. Complications of obesity. QJM Mon J Assoc Physicians. 2018 Jul 1;111(7):437–43.

10. Tremmel M, Gerdtham UG, Nilsson PM, Saha S. Economic Burden of Obesity: A Systematic Literature Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017 Apr;14(4):435.

11. Swinburn BA, Kraak VI, Allender S, Atkins VJ, Baker PI, Bogard JR, et al. The Global Syndemic of Obesity, Undernutrition, and Climate Change: The Lancet Commission report. The Lancet. 2019 Feb;393(10173):791–846.

12. Endocrine disruptors - ECHA [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jun 18]. Available from: https://echa.europa.eu/hot-topics/endocrine-disruptors

13. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jun 18]. Endocrine Disruptors Available from: https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/ agents/endocrine/index.cfm

14. TEDX - The Endocrine Disruption Exchange [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jun 18]. Search the TEDX List. Available from: https:// endocrinedisruption.org/interactive-tools/tedx-list-of-potential-endocrine-disruptors/search-the-tedx-list

15. Baillie-Hamilton PF. Chemical Toxins: A Hypothesis to Explain the Global Obesity Epidemic. J Altern Complement Med. 2002 Apr;8(2):185–92.

16. Heindel JJ. History of the Obesogen Field: Looking Back to Look Forward. Front Endocrinol [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2023 Jun 18];10. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/ articles/10.3389/fendo.2019.00014

17. Grün F, Blumberg B. Environmental Obesogens: Organotins and Endocrine Disruption via Nuclear Receptor Signaling Endocrinology. 2006 Jun 1;147(6):s50–5.

18. Kim S, Moustaid-Moussa N. Secretory, Endocrine and Autocrine/Paracrine Function of the Adipocyte. J Nutr. 2000 Dec 1;130(12):3110S-3115S.

19. Giordano A, Smorlesi A, Frontini A, Barbatelli G, Cinti S. MECHANISMS IN ENDOCRINOLOGY: White, brown and pink adipocytes: the extraordinary plasticity of the adipose organ [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2023 Jun 18]. Available from: https:// academic.oup.com/ejendo/article/170/5/R159/6661591

20. Luong Q, Huang J, Lee KY. Deciphering White Adipose Tissue Heterogeneity. Biology. 2019 Apr 11;8(2):23.

21. Longo M, Zatterale F, Naderi J, Parrillo L, Formisano P, Raciti GA, et al. Adipose Tissue Dysfunction as Determinant of Obesity-Associated Metabolic Complications. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 May 13;20(9):2358.

22. Schelling JR. The Contribution of Lipotoxicity to Diabetic Kidney Disease. Cells. 2022 Oct 14;11(20):3236.

23. Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, Tan G, Yang D, Chou CJ, et al. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2003 Dec 15;112(12):1821–30.

24. Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman JM. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature. 1994 Dec;372(6505):425–32.

25. Park YM, Myers M, Vieira-Potter VJ. Adipose Tissue Inflammation and Metabolic Dysfunction: Role of Exercise. Mo Med. 2014;111(1):65–72.

26. Bai Y, Sun Q. Macrophage recruitment in obese adipose tissue. Obes Rev Off J Int Assoc Study Obes. 2015 Feb;16(2):127–36.

27. Surmi BK, Hasty AH. Macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue. Future Lipidol. 2008;3(5):545–56.

28. Kahn BB, Flier JS. Obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2000 Aug 15;106(4):473–81.

29. Hotamisligil GS. The role of TNFα and TNF receptors in obesity and insulin resistance. J Intern Med. 1999;245(6):621–5.

30. Sethi JK, Hotamisligil GS. Metabolic Messengers: tumour necrosis factor. Nat Metab. 2021 Oct;3(10):1302–12.

31. Stein CJ, Colditz GA. The Epidemic of Obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004 Jun 1;89(6):2522–5.

32. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevalence of overweight and obesity among adults with diagnosed diabetes-United States, 1988-1994 and 1999-2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004 Nov 19;53(45):1066–8.

33. Beyer J, Song Y, Tollefsen KE, Berge JA, Tveiten L, Helland A, et al. The ecotoxicology of marine tributyltin (TBT) hotspots: A review. Mar Environ Res. 2022 Jul 1;179:105689.

34. Van Kerk GJMD, Luijten JGA. Investigations on organo-tin compounds. III. The biocidal properties of organo-tin compounds. J Appl Chem. 1954;4(6):314–9.

35. Novotny L, Sharaf L, Abdel-Hamid ME, Brtko J. Stability studies of endocrine disrupting tributyltin and triphenyltin compounds in an artificial sea water model. Gen Physiol Biophys. 2018;37(01):93–9.

36. Gibbs PE, Bryan GW. Reproductive Failure in Populations of the Dog-Whelk, Nucella Lapillus , Caused by Imposex Induced by Tributyltin from Antifouling Paints. J Mar Biol Assoc U K. 1986 Nov;66(4):767–77.

37. Oehlmann J, Stroben E, Fioroni P. The Morphological Expression of Imposex in Nucella Lapillus (Linnaeus) (Gastropoda: Muricidae) [Internet]. 1991 [cited 2023 Jun 24]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/mollus/ article-lookup/doi/10.1093/mollus/57.3.375

38. Shimasaki Y, Kitano T, Oshima Y, Inoue S, Imada N, Honjo T. Tributyltin causes masculinization in fish. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2003;22(1):141–4.

39. McAllister BG, Kime DE. Early life exposure to environmental levels of the aromatase inhibitor tributyltin causes masculinisation and irreversible sperm damage in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Aquat Toxicol. 2003 Nov 19;65(3):309–16.

40. Holtcamp W. Obesogens: An Environmental Link to Obesity. Environ Health Perspect. 2012 Feb;120(2):a62–8.

41. Lyssimachou A, Santos JG, André A, Soares J, Lima D, Guimarães L, et al. The Mammalian Obesogen Tributyltin Targets Hepatic Triglyceride Accumulation and the Transcriptional Regulation of Lipid Metabolism in the Liver and Brain of Zebrafish. PLoS ONE. 2015 Dec 3;10(12):e0143911.

42. Nishikawa J ichi, Mamiya S, Kanayama T, Nishikawa T, Shiraishi F, Horiguchi T. Involvement of the Retinoid X Receptor in the Development of Imposex Caused by Organotins in Gastropods. Environ Sci Technol. 2004 Dec 1;38(23):6271–6.

43. Mohajer N, Du CY, Checkcinco C, Blumberg B. Obesogens: How They Are Identified and Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Their Action. Front Endocrinol. 2021 Nov 25;12:780888.

44. Li X, Ycaza J, Blumberg B. The environmental obesogen tributyltin chloride acts via peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma to induce adipogenesis in murine 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2011 Oct;127(1–2):9–15.

45. Griffin MD, Pereira SR, DeBari MK, Abbott RD. Mechanisms of action, chemical characteristics, and model systems of obesogens. BMC Biomed Eng. 2020 Apr 30;2:6.

46. A2-33. English: Structure of the PPAR-gamma receptor bound to DNA [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2023 Jun 25]. Available from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:PPARG.png

47. Grün F, Watanabe H, Zamanian Z, Maeda L, Arima K, Cubacha R, et al. Endocrine-Disrupting Organotin Compounds Are Potent Inducers of Adipogenesis in Vertebrates. Mol Endocrinol. 2006 Sep 1;20(9):2141–55.

48. Dawson MI, Xia Z. The retinoid X receptors and their ligands [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2023 Jun 25]. Available from: https:// linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1388198111001843

49. Na J, Park BS, Jang D, Kim D, Tu TH, Ryu Y, et al. Distinct Firing Activities of the Hypothalamic Arcuate Nucleus Neurons to Appetite Hormones. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Jan;23(5):2609.

50. Desai M, Ferrini MG, Han G, Jellyman JK, Ross MG. In Vivo Maternal and In Vitro BPA Exposure Effects on Hypothalamic Neurogenesis and Appetite Regulators. Environ Res. 2018 Jul;164:45–52.

51. Kumar A, Pareek V, Faiq MA, Ghosh SK, Kumari C. ADULT NEUROGENESIS IN HUMANS: A Review of Basic Concepts, History, Current Research, and Clinical Implications. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2019 May 1;16(5–6):30–7.

52. Goodman JE, Peterson MK. Bisphenol A. In: Wexler P, editor. Encyclopedia of Toxicology (Third Edition) [Internet]. Oxford: Academic Press; 2014 [cited 2023 Jun 26]. p. 514–8. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/ article/pii/B9780123864543003663

53. Rubin BS, Schaeberle CM, Soto AM. The Case for BPA as an Obesogen: Contributors to the Controversy. Front Endocrinol. 2019 Feb 6;10:30.

54. Nutrition C for FS and A. Bisphenol A (BPA): Use in Food Contact Application. FDA [Internet]. 2023 Apr 20 [cited 2023 Jun 26]; Available from: https://www.fda.gov/food/ food-additives-petitions/bisphenol-bpa-use-food-contactapplication

55. Nakamura K, Itoh K, Yaoi T, Fujiwara Y, Sugimoto T, Fushiki S. Murine neocortical histogenesis is perturbed by prenatal exposure to low doses of Bisphenol A. J Neurosci Res. 2006 Nov 1;84(6):1197–205.

56. Nakamura K, Itoh K, Sugimoto T, Fushiki S. Prenatal exposure to bisphenol A affects adult murine neocortical structure. Neurosci Lett. 2007 Jun 13;420(2):100–5.

57. Nakamura K, Itoh K, Dai H, Han L, Wang X, Kato S, et al. Prenatal and lactational exposure to low-doses of bisphenol A alters adult mice behavior. Brain Dev. 2012 Jan;34(1):57–63.

58. Baggio LL, Drucker DJ. Biology of Incretins: GLP-1 and GIP. Gastroenterology. 2007 May;132(6):2131–57.

59. Egusquiza RJ, Blumberg B. Environmental Obesogens and Their Impact on Susceptibility to Obesity: New Mechanisms and Chemicals. Endocrinology. 2020 Mar 1;161(3):bqaa024.

60. Shannon M, Green B, Willars G, Wilson J, Matthews N, Lamb J, et al. The endocrine disrupting potential of monosodium glutamate (MSG) on secretion of the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) gut hormone and GLP-1 receptor interaction. Toxicol Lett. 2017 Jan;265:97–105.

61. Heindel JJ, Blumberg B. Environmental Obesogens: Mechanisms and Controversies. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2019 Jan 6;59:89–106.

62. Chamorro-Garcia R, Blumberg B. Current Research Approaches and Challenges in the Obesogen Field. Front Endocrinol. 2019 Mar 22;10:167.

63. Behl M, Rao D, Aagaard K, Davidson TL, Levin ED, Slotkin TA, et al. Evaluation of the Association between Maternal Smoking, Childhood Obesity, and Metabolic Disorders: A National Toxicology Program Workshop Review. Environ Health Perspect. 2013 Feb;121(2):170–80.

64. Wang Y, Lobstein T. Worldwide trends in childhood overweight and obesity. Int J Pediatr Obes IJPO Off J Int Assoc Study Obes. 2006;1(1):11–25.

65. de Onis M, Blössner M, Borghi E. Global prevalence and trends of overweight and obesity among preschool children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010 Nov;92(5):1257–64.

66. Avenue 677 Huntington, Boston, Ma 02115. Obesity Prevention Source. 2012 [cited 2023 Jun 26]. Child Obesity. Available from: https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/obesityprevention-source/obesity-trends-original/global-obesitytrends-in-children/

67. National Institutes of Health (NIH) [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2023 Jul 2]. New comprehensive view of the mouse genome finds many similarities and striking differences with human genome. Available from: https://www.nih.gov/news-events/ news-releases/new-comprehensive-view-mouse-genomefinds-many-similarities-striking-differences-human-genome

68. Howe K, Clark MD, Torroja CF, Torrance J, Berthelot C, Muffato M, et al. The zebrafish reference genome sequence and its relationship to the human genome. Nature. 2013 Apr 25;496(7446):498–503.

69. Lefterova MI, Haakonsson AK, Lazar MA, Mandrup S. PPARγ and the global map of adipogenesis and beyond. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Jun;25(6):293–302.

EXPLORING EMERGENT PROPERTIES OF COMPLEX SYSTEMS USING MACHINE LEARNING

STEM FINLAY SANDERS

This report was based on an Original Research in Science (ORIS) project in partnership with Imperial College London and was short-listed for the ILA/ORIS Presentation Evening.

INTRODUCTION

Many natural phenomena display properties or behaviours more than the mere aggregation of their parts. Humans, for instance, are capable of language, cog- nition and intricate social behaviours, none of which are properties of individual cells. Similarly, each cell’s functionality arises from the interactions be- tween molecules, even though none possess the cell’s capabilities independently. This pattern, where macroscopic properties arise from interactions between mi- croscopic components, termed

’emergence’, is a hallmark of complex systems. Emergence creates layers of abstraction within a system, where each behaves according to its own physical laws.

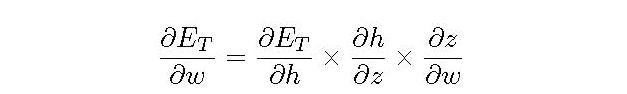

Formal theories of emergence have already been introduced using informa- tion theory, such as in5 The contribution of this paper is a novel method of identifying emergence using machine learning. By approximating the dynamics of a complex system at different spatiotemporal scales, I confirm numerically

that these layers of abstraction exist, and that the dynamics of each can be learned by a data-driven approach.

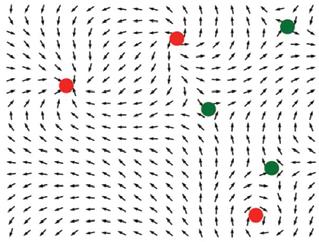

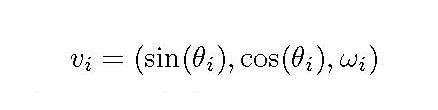

I evaluate this method using the Classical XY model, a lattice model of statistical mechanics relevant to phenomena such as the melting of crystals, magnetism and superconductivity, as an example. At the microscopic scale, the model consists of a collection of spins on a lattice that can point in any direction in the plane, which operate according to the dynamics of equation 4. At the macroscopic scale, the model is characterised by emergent structures termed ’vortices’ and ’anti-vortices’, which describe topological flaws where groups of spins make a 2π rotation either clockwise or anticlockwise, that follow Coulomb dynamics.

To this end, I propose a dual pathway approach to predicting the trajectories of spins and vortices using graph neural networks. First, I trained a model to predict spin dynamics, from which the vortices could be extracted. Second, I trained a model that bypasses spins, instead directly predicting vortex move- ments. By drawing parallels to commutativity diagrams, I demonstrate that both pathways converge to accurate vortex predictions, even over extended rollouts.

BACKGROUND

2.1 XY Model Simulation

the dynamics of spins and vortices can be learned. I chose to simulate the XY model with periodic boundary conditions (PBCs), meaning that spins on a given boundary are adjacent to spins at the opposite boundary. In essence, PBCs let a small system approximate an infinite one, as all spins have an equal amount of neighbours. Discussed below are two methods of simulating the XY model, the latter of which was ultimately chosen.

“ I propose a dual pathway

approach to predicting the trajectories of spins and vortices using graph neural networks.

Metropolis-Hastings Algorithm

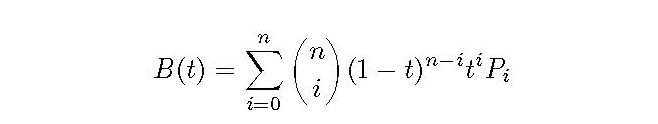

The Metropolis-Hastings algorithm, a Markov Chain Monte Carlo method, is well suited for simulating the XY model. The term ‘Markov Chain’ indicates that the state of the XY model at time t + 1 is solely influenced by its state at time t. ‘Monte Carlo’ means that spins change according to a specified probability distribution. To this end, we assume the spins interact according to the energy given by the Hamiltonian (an equation for the sum of the system’s energy), as discussed in4:

where J is the coupling constant and j(i) denotes summation over each of the 4 nearest neighbours, j, of lattice site i. Intuitively, the interaction energy of a pair of spins i, j is minimised when θi = θj. The algorithm for updating a single spin proceeds as follows:

1. Pick a spin θi on the lattice

2. Change the angle of the selected spin by some small amount ∆θ to produce a new angle θi′

3. Calculate the energy change in the system due to this proposed change using the Hamiltonian:

4. Choose whether to accept the proposed change. If ∆E < 0 we accept the change because it lowers the energy. If ∆E > 0 we accept the change with probability:

By iterating over all spins on the lattice at time t, we reach a subsequent state of the system at time t + 1. Although reasonable, this method isn’t preferred due to the inconsistency of its spin updates over extended time periods.

Numerical Integration

Numerical integration, as detailed in2, produces predictable and therefore learnable, rollouts of the XY model by eliminating all randomness in spin up- dates. By altering the Hamiltonian above and

introducing a kinetic energy term, they derived the following equations of motion:

Intuitively, the right-hand side of this equation gives us the angular accelera- tion of each spin. To transition the state of an XY model from time t to t+1, we first update each spin’s angular velocity by adding the computed angular accel- erations. Then, we adjust each spin’s angle by adding their velocities. I found that slightly damping the added velocities led to more stable vortex movements and removed the possibility of vortices spontaneously appearing.

Final Intuitions

XY Model at time t XY model at time t + 10 Figure 1: An example of the XY model’sspins at times t and t + 10.

Figure 1 is an example of how the XY model evolves over time. Vortices and anti-vortices are marked with red and green dots respectively.

The most fundamental pattern of the system is that vortices of the same type repel and those of opposite type attract, although this is not always obvious. The first source of confusion is that the two vortices in the bottom right have disappeared, or ’annihilated’, in the t + 10 configuration. This happens when vortices inevitably meet, cancel out and allow the spins they previously distorted to become uniform. The next difficulty is that the vortices on the far left and right boundaries appear to have moved away from each other, despite my previous claim that they should meet and annihilate. This is caused by the previously discussed periodic boundary conditions, which allow the vortices to attract across boundaries.

2.2 Graph Neural Networks

Neural Networks (NNs), a pillar of machine learning, are proven to be capable of representing any continuous function given an appropriate

architecture1. In a trained network, input data is transformed according to internal parameters to produce useful output such as a prediction or classification. However, traditional feed-forward neural networks don’t inherently capture structured relationships between input data points, like the local interactions that are crucial to the XY model.

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are designed to work on data structured as graphs. These networks not only consider data points but also the relationships between them. Equipped with in-built assumptions that prioritise relationships (often termed as ’relational inductive biases’)3, GNNs are particularly adept at handling systems where interactions between individual components are paramount, making them especially suitable for approximating complex systems like the XY model.

Neural Networks

Neural networks are often visualised as interconnected layers of neurons. The type of traditional neural network I used to create graph neural networks is called a multi-layer perceptron, where all nodes in layer l are connected to those in layer l + 1. The first and last layers are the input and output layers and any intermediate layers are called hidden layers.