VIEWS

UNITY: VARIED PERSPECTIVES FOR A COMMON GOAL

President | Ritchie Bryant, MS, CDI, CLIP-R

Vice President | Dr. Jesús Remigio, PsyD, MBA, CDI

Secretary | Jason Hurdich, M.Ed, CDI

Treasurer | Kate O’Regan, MA, NIC

Member-at-Large | Traci Ison, NIC, NAD IV

Deaf Member-at-Large | Glenna Cooper, PDIC

Region I Representative | Christina Stevens, NIC

Region II Representative | M. Antwan Campbell, MPA, Ed:K-12

Region III Representative | Shawn Vriezen, CDI, QMHI

Region IV Representative | Justin “Bucky” Buckhold, CDI

Region V Representative | Jeremy Quiroga, CDI

Chief Executive Officer | Star Grieser, MS, CDI, ICE-CCP

Chief Operating Officer | Elijah Sow

Operations Project Coordinator | Kirsten Swanson

Human Resources Manager | Cassie Robles Sol

CMP Manager | Ashley Holladay

CMP Specialist | Kayla Marshall

EPS Manager | Tressela Bateson

EPS Specialist | Martha Wolcott

Certification Manager | Catie Purrazzella

Certification Specialist | Jess Kaady

Director of Member Services | Ryan Butts

Member Services Specialist | Vicky Whitty

Director of Government Affairs | Neal Tucker

Affiliate Chapter Liaison | Dr. Carolyn Ball, CI and CT, NIC

Director of Communications | JJ Johnson

Web and Production Manager | Jenelle Bloom

Director of Finance and Accounting | Jennifer Apple

Finance and Accounting Manager | Kristyne Reeds

Staff Accountant | Bradley Johnson

RID is the national certifying body of sign language interpreters and is a professional organization that fosters the growth of the profession and the professional growth of interpreting.

We envision qualified interpreters as partners in universal communication access and forward-thinking, effective communication solutions while honoring intersectional diverse spaces.

RID's purpose is to serve equally our members, profession, and the public by promoting and advocating for qualified and effective interpreters in all spaces where intersectional diverse Deaf lives are impacted.

RID understands the necessity of multicultural awareness and sensitivity. Therefore, as an organization, we are committed to diversity both within the organization and within the profession of sign language interpreting.

Our commitment to diversity reflects and stems from our understanding of present and future needs of both our organization and the profession. We recognize that in order to provide the best service as the national certifying body among signed and spoken language interpreters, we must draw from the widest variety of society with regards to diversity in order to provide support, equality of treatment, and respect among interpreters within the RID organization.

Therefore, RID defines diversity as differences which are appreciated, sought, and shaped in the form of the following categories: gender identity or expression, racial identity, religious affiliation, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, Deaf or hard of hearing status, disability status, age, geographic locale (rural vs. urban), sign language interpreting experience, certification status and level, and language bases (e.g., those who are native to or have acquired ASL and English, those who utilize a signed system, among those using spoken or signed languages) within both the profession of sign language interpreting and the RID organization.

To that end, we strive for diversity in every area of RID and its Headquarters. We know that the differences that exist among people represent a 21st century population and provide for innumerable resources within the sign language interpreting field.

Welcome to the latest Winter edition of RID VIEWS, where we focus on important topics that shape our national organization. In this issue, we delve into the critical topic of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, Accessibility, and Belonging (DEIAB). It is crucial to have open and honest discussions about the significance of DEIAB in organizations like RID. We aim to educate and raise awareness about the impact of DEIAB and why it is essential to create a more inclusive and equitable environment for all.

At RID, we recognize the importance of not just talking about DEIAB, but taking concrete steps to implement these principles. Our goal is to create an organizational culture that prioritizes DEIAB and supports the diverse needs of our members, stakeholders and consumers. To achieve this goal, we will develop and implement action plans that address systemic barriers, promote equal opportunities, and foster a sense of belonging for all members. By putting DEIAB at the forefront of our work, we can create a more inclusive and equitable environment that supports the growth and success of all RID community members.

Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, Accessibility, and Belonging (DEIAB) benefits sign language interpreting professionals in several ways:

Enhances cultural competence: By prioritizing DEIAB, sign language interpreting professionals can develop a deeper understanding and appreciation of different cultures, improving their cultural competence and leading to more effective communication with individuals from diverse backgrounds.

Improves accessibility: By valuing and promoting diversity, sign language interpreting professionals can work toward making their services more accessible to individuals from diverse backgrounds, which can increase their client base and improve their overall impact.

Supports inclusiveness: A commitment to DEIAB can lead to more inclusive practices within the sign language interpreting profession, which can support the rights and dignity of all individuals, including those who are Deaf, DeafBlind, DeafDisabled, and Hard of Hearing.

Promotes professional growth: Sign language interpreting professionals who prioritize DEIAB can learn from their diverse colleagues and clients, broadening their perspectives and leading to personal and professional growth.

Strengthens the sign language interpreting community: By promoting DEIAB, sign language interpreting professionals can help create a more diverse and inclusive community, strengthening the profession and leading to greater collaboration and support among colleagues.

DEIAB can benefit sign language interpreting professionals by enhancing cultural competence, improving accessibility, supporting inclusiveness, promoting professional growth, and strengthening the communities we serve.

DEIAB Audit Checklist:

https://www.xenia.team/articles/diversity-equity-and-inclusion-dei-audit-checklist

DEI Committee:

https://www.uschamber.com/co/start/strategy/diversity-equity-inclusion-committee

https://www.indeed.com/career-advice/career-development/types-of-diversity-in-workplace

https://internalaudit360.com/is-it-time-to-conduct-a-diversity-and-inclusion-audit/

Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, Accessibility and Belonging - DEIAB – is one of the four pillars of our recently released Strategic Plan for the organization. DEI initiatives for all organizations are long overdue and, unfortunately, often inadequate and, at times, woefully performative. As RID’s CEO, it’s my role to effectively set the tone for our DEIAB commitment and to implement measures to enhance the representation and participation of marginalized communities within RID and our components (councils, committees, work groups, task forces, affiliate chapters, and member sections) while at the same time working to ensure RID headquarters staff members also embody and carry out the values of DEIAB and the values of our organization.

How does RID show we value diversity, equity, inclusion, accessibility and belonging? What are we already doing? And why is that not enough? What should we be doing better or differently? And why?

The question of how we express our values is an ongoing conversation with many Board members, Headquarters staff, and our volunteers and also something I – internally – strive to educate myself on. Too often, well-meaning people leading well-meaning organizations will embrace the concepts of DEI, tout these values, and host workshops and webinars on DEI principles. Yet, frequently nothing changes, or worse, the state of diversity and inclusion within an organization may actually backslide. That thought, for me, is repugnant. That is not what we want within RID.

While our organization does many things right, our ASL interpreting profession as a whole has a long way to go in being diverse, equitable, inclusive, accessible, and a profession where everyone – everyone – feels a sense of belonging within the field. The irony is that the entire point of the ASL interpreting profession is to provide effective communication access for Deaf, DeafBlind, Hard of Hearing, and DeafDisabled people for the very purpose of inclusion in life activities, the pursuit of equality and equal opportunities for education, employment and success, and for participating in spaces that, by design, otherwise exclude us.

And yet ASL interpreters as a whole don’t do that enough for each other as professionals, as leaders in the profession, as colleagues, as mentors and mentees, and as teachers and students. In fact, interpreters who are also members of marginalized communities often report feeling gate-kept out of the profession. As the national certifying body of sign language interpreters and professional organization that fosters the growth of the profession and the professional growth of interpreting, That. Is. Not. Okay.

Granted, there are a number of things that RID does right. First, we have an official Diversity Statement and have had this statement in place for almost a decade. Second, we require CEUs for recertification specific to fostering an understanding of Power, Privilege and Oppression and the power dynamics it creates in our work. We have repeatedly articulated our values

towards DEIAB. The national office is pretty diverse - 19% BIPOC representation, and 27% LGBTQIA2S+ representation. The RID Board of Directors are also pretty diverse with 36% BIPOC representation, with 50% of the Executive Board BIPOC. DEIAB became a strategic priority for RID, meaning funds will be allocated towards consultation and training and setting metrics for our organization to be able to gauge if our efforts are achieving what they aim to or not.

Yet in our last annual report, our membership is still 84% white hearing women. There’s nothing wrong with being white and hearing, but the demographics of our profession do not even closely reflect the demographics of our consumers or even the general population.

This country has over 100 Historical Black Colleges or Universities (HBCUs); none have an interpreter training program. In our most recently published annual report, the percentage of members who selfidentified as Black is only 4%.

Although the CDI Certification Program is now fully operational and newly certified CDIs are joining our ranks, RID’s certified membership of Deaf interpreters is roughly 2%.

Our profession is not only not diverse enough, but too many Black and Brown interpreters, Deaf interpreters, LGBTQAI2S+ interpreters, and members of marginalized minorities report feeling unwelcome and excluded from the profession and, by extension, by our organization.

Some of the things the RID Board has done so far was to host town hall meetings focusing on the experiences of BIPOC and Deaf interpreters. These provide space for critical conversations about discrimination, racism, audism and systemic barriers in place that our interpreters are experiencing as they navigate their journey in the profession. Some of these conversations were brave, raw, and unfiltered. They shined a light on their individual and collective experiences with roadblock after exhausting roadblock. These conversations are far from over – RID must continue creating space, having these conversations and listening with the intention to understand our part in reinforcing and upholding those barriers and identifying and then taking the corrective actions to dismantle them.

It’s not enough for RID to recruit and appoint volunteers, committee members, Board members and staff members from diverse communities and backgrounds, e.g., to intentionally create space at the table – we already do that with varying degrees of success – but and align our values where diversity is celebrated and inclusion, equity, and accessibility are in place by design will foster the fifth and most important aspect of DEI: belonging.

We belong to groups that align with our values: clubs, churches, political parties, friend groups, and so forth. The same is true for professional organizations: We also belong to them to enrich our lives both professionally and personally. It’s more than just having diverse people at the table. It’s about creating an intentional community of professionals based on respect for our work and advancing our profession. One with various perspectives, narratives, ideas, information, research, experiences, etc., to share with everyone at the table, so we are all learning together and growing from these conversations.

The more diversity we have in our membership and, by extension, our profession, the stronger we are collectively. The more able we will be to collaboratively act as agents of positive changes and equality within our profession for and for the benefit of the consumers we serve. Belonging is interwoven with diversity, inclusion, equity and accessibility — they are all interdependent. If we take out one aspect, the implementation of DEIAB fails, and RID is weakened.

For us to be a strong organization and to elevate the profession to the next level, it is imperative that the Board of Directors and I ensure DEIAB is fully embraced and appropriately implemented in all facets of RID. I hope you will join us in upholding RID’s DEIAB values for the betterment of the organization. With your support, we will achieve extraordinary things for our members, stakeholders and consumers — things that we all deserve.

Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, Accessibility and Belonging, DEIAB, is an awesome approach to our thinking. Like any other approach, if we are unable or not ready to use it, it is worthless. Privilege can be a tool but we must understand it and then choose to use it for better. We have been discussing a lot of the behaviors of people with privilege, how privilege impacts others, or how privilege is used for one’s own gain. This leads me to discuss the privileged mind, the power of our mind to embrace opening and understanding or to simply shut down the idea because it is easier not to understand it.

about oppressive behaviors that arise with our values and biases. Oppressive behaviors worsen when we claim our values are more important than those of others, which can lead to harm. What is interesting is that many hearing interpreters believe they have acculturated to Deaf culture and the Deaf community; yet, Deaf shared values are often ignored because hearing values are so embedded in the ways that “we” grew up. When these behaviors are explicitly addressed, the response is often that changing or addressing the issues are “a lot of work” to which oppressed people just roll their eyes.

As we grow, our environment enculturates us leading to certain values that we incorporate into our thinking and behavior. Here I would like to go back to the power of the privileged mind and how it can cause us to have a blind spot in learning

Another problem is when there is a group of people telling stories, a truth or an experience that impacted them, what I have seen is other people saying, “What about me, my values and my feelings?” An example of this is choosing to not use sign language in a space where Deaf people are present. The response may be, “I want to be able to speak in my language.” Let’s move back to the DEIAB lens to discuss this issue. Clearly, interpreters are involved with the Deaf

Jeremy Quiroga, CDI Region V Representative

"Privilege can be a tool but we must understand it and then choose to use it for better . "

"Oppressive behaviors worsen when we claim our values are more important than those of others, which can lead to harm . "

"An example of this is choosing to not use sign language in a space where Deaf people are present . "

community which is home to a very diverse group of people; are they being heard? The issue at hand is accessibility and belonging. When those interpreters blatantly choose not to sign, they cause Deaf people, the very people they serve, to feel excluded. That in and of itself is not equity - period. I just hit all the DEIAB in one simple example. We keep asking and fighting only to be told that the more privileged people want to speak in their language even though the world and space that we all walk in is not hearing. It is just not a great feeling knowing that this small space for this short amount of time could be respected more if we really valued DEIAB.

I just gave an example as a Deaf person from a Deaf experience and the ongoing puzzlement of, “Why do they not care? Do our human values even merit the acceptance from others?” I am still learning about other issues in our humanity because I recognize that I grew up in a certain environment that developed values that I need to look at again to honor the idea of treating others the way they deserve to be treated. I invite you to look at where we are and whether our privileged mind is blocking our ability to embrace differences. Then, when that happens start considering the next level of looking at how we work and interact with people who themselves are part of different and diverse communities.

"An example of this is choosing to not use sign language in a space where Deaf people are present . "

Certifications Field Conventions and Hierarchy

1

Valid generalist certifications no longer offered (IC, TC, CSC, MCSC, RSC, ETC, EIC, OIC, CI and/or CT, OTC, NIC Advanced, Master) appear before all others. IC and/TC appear first (e.g. IC/TC, CSC).

OIC certifications appear directly after all other old generalist certifications (e.g. TC, CSC, OIC:C)

3

2

Current generalist certifications (CDI, NIC) appear after generalist certifications that are no longer offered (e.g. IC, CI and CT, OTC, NIC)

4 NIC certification appears after the CI and/or CT

5

The OTC certification appears after the NIC certification

Specialist certifications (SC:L and SC:PA) appear after all generalist certifications

6

7 NAD certifications appear after all RID certifications

8 Ed:K-12 appears after NAD certification

9 CI and CT are always expressed together as “CI and CT” or “CI & CT”

Karen King is a certified interpreter (NIC) and a SODA (Sibling of a Deaf Adult) from Portsmouth, Virginia, with almost 30 years of educational interpreting experience and over fifteen years of video relay interpreting experience. She graduated from Danville Community College’s Weekend Educational Interpreter Training (WEIT) in 2004, and has a Bachelor of Arts degree from Regent University in Biblical and Theological Studies. King is currently pursuing a Masters in Liberal Arts from Rutgers University.

By Karen King, NIC

By Karen King, NIC

Recently, I stumbled upon a George Bernard Shaw quote about communication that read, “The single biggest problem in communication, is the illusion that it has taken place.” As an educational interpreter (EI), I contemplated what this meant to me. I realized that in my experience, many of the miscommunications that led to complications had had nothing to do with a signed or spoken interpreted message. This article addresses several things EIs should consider when branding their work to their professional colleagues, to prevent the illusion of communication. The EIs’ explanation should consider the diversity of all stakeholders, especially when using interpreter-specific terminology. Joan Wink, in Critical Pedagogy, emphasizes this point by stating, “Our unique real world is the culture we know best; it is where we feel most at home; we speak the language; we know the perspective”

Imagine it is the week before school starts. As a proactive professional, you set up a meeting with

each teacher to introduce yourself and briefly explain the role of an educational interpreter working in the classroom. After a brief exchange of formalities, you state that you will interpret all spoken interactions into ASL and voice whatever the deaf student signs. Additionally, you inform the teacher that you cannot be responsible for any students, that you do not teach, tutor, or aid, and if students have any questions, they can ask you, the teacher. The teacher tells you they have worked with deaf students and interpreters before.

On the surface, the teacher-interpreter relationship appears to be off to a great start, but this verbal exchange is an illusion that fails to acknowledge the different worlds occupied by the participants. Each student’s access to language, culture and social norms differs, requiring the entire educational team to make appropriate accommodations, including the need for the interpreter to provide tutoring and pre-teach vocabulary. These accommodations may not align

with what the interpreter has told the teacher previously. Furthermore, the teacher who states, “I have worked with deaf students and interpreters before,” may add to the communication illusion. In reality, the teacher walks away with the misconception that the interpreter will faithfully communicate their “words” and mimic their pedagogy—method of teaching—without deviation and that their work will be the same as previous interpreters.

On the contrary, the interpreter understands the need for critical pedagogy and bridges linguistic/cultural gaps to ensure equal access to communication and education. As an interpreter, how should we share our perspectives in a manner that communicates effectively? What is implied when we say we interpret all spoken interactions into ASL (or signed English) and voice whatever the deaf student signs? Does this explanation suggest we render a literal interpretation—a signed word for each spoken word?

One prevalent challenge revolves around explaining and executing the ever-moving role of the interpreter in the K-12 setting. Working within our Role Space, interpreters are constantly making decisions on how to meet individual students’ needs. Decisions change depending on the student’s extralinguistic knowledge (ELK) and knowledge of the language (KL) in order to match the student’s comprehension level while also providing cultural mediation. How do EIs facilitate communication when the deaf student does not possess the tools to access communication in an academic setting? Should the product deviate from the teacher’s instruction methods to provide a “concept for concept” interpretation as opposed to “word for word”? Could cultural and linguistic mediation be perceived as “teaching?” Do you as an interpreter, have the appropriate language to explain our ever-moving role?

The profession of educational interpreting has significantly evolved in my 29 years of work. To this day, the proper method of communicating the role of a classroom interpreter without

ambiguity, remains elusive. Do we effectively communicate that we are professional members of the educational and Individualized Educational Program (IEP) teams—language facilitators, language developers, and cultural mediators— with knowledge of peculiarities that are intrinsically embedded into our unique position? I question whether the role of the educational interpreter has been adequately explained and how that explanation impacts human relations and interactions with other school personnel. Beginning an intentional dialogue among educational professionals will work to prevent “miscommunication,” and will help formulate a collective (universal) language.

One possible way to alleviate miscommunication is to describe the intentionality of our role, such as introducing yourself as the language professional assigned to facilitate communication between people who are deaf and hearing, mediate cultural and language gaps, and work with the team to develop the language and socio-emotional confidence in the student-teacher relationship that is necessary to access all elements of academia. We should be mindful of the fact that each communication event with our academic team members is an opportunity to enhance our understanding of the interpreting profession. EIs have the opportunity to model language in a bi-lingual/bi-cultural manner that clearly articulates the diversity and fluidity involved in effective interpreting. Our goal should be a bi-professional language that allows us to communicate the ever-changing interpreter role with our educational colleagues effectively.

Jason Hurdich, M .Ed .; CDI, RID Board of Directors Secretary (Past Region II Representative)

Amber Robinson, B .S . and NIC

Jason: So, during your ITP, what were your thoughts about maybe this is not the right fit, feeling out of place? Did you feel like that?

Amber: Yes. I felt like that. That was my only option for becoming an interpreter. That program.

Jason: You had to stay there.

Amber: HBCUs (Historically Black Colleges and Universities) don't have ITPs. I would have loved to do the interpreting program there, yes! But there was no opportunity to; you still have to realize that it is a white world right now. It will grow, it will, I know it will. But right now, you have to accept what it is. And move forward accordingly. Maybe one day, I will have a school or an agency of my own; you never know. And many other Black interpreters in a similar position as me feel they keep moving on inside a white ITP world. And they still continue to form agencies, groups, organizations, and multiple other associations for Black interpreters and white interpreters, BIPOC interpreters. The field is growing right now.

Jason: So, now talking about ITP, knowing that 99% of ITPs are white-run, assuming that figure. It's a fact, so I'm curious how ITPs in the field, not only in the U.S. but within the field internationally, shift to become more inclusive of not only Black culture but of several

cultures, Latino, LGBTQIA, and diverse communities. Knowing that in history, the majority of those who write interpreter education manuals and create media are white deaf or hearing. I'm curious, what do you envision a curriculum would look like? How would you envision white allies supporting that?

Amber: My first thought is to stop using us for diversity. Stop the word “diversity.” stop using that word. What I mean, for example, Black History Month. That is the busiest time for Black interpreters, really. Other times of the year when you need a Black interpreter — or a BIPOC interpreter, or so on, it's when their specific theme or event happens. That is when we are used.

Jason: Like pride month in June.

Amber: June is a big month — they always have a specific type of event during the month. You only use minority interpreters when people are ready to bring us out for more BIPOC or cultural events. Black, or whatever. Why? It is hard to trust you. Where's that trust?

Jason: I understand.

Amber: Where is that trust when you want us. If you wish to have us, please invite and welcome us to your workshops, conferences, and organizations. Come, and open the door. That way, we can expand our visibility and grow our community. But one thing is that people tend to be dismissive of younger interpreters and of us.

Jason: Yes, that is true. Younger interpreters are dismissed — can you elaborate on that?

Amber: I mean, you have interpreting students who recently graduated, and they decide they're going to team with another interpreter, and the team is condescending, saying, “it's fine, I got it,” and we're dismissed out of hand. But the younger interpreter can teach so much. We want mentoring, teaming up, and interacting to benefit from various experiences. You want more conference workshops at events, but the older generation pays lip service, saying we need to do this and this. We've done it for so long that we already know, we're familiar — we can do this. Yes!

But younger interpreters are feeling left out. Where is content from 2022 — we don't have anything. Is there anything from 2015? Where is anything recent, not from the 1980s? There is so much that is happening now in the world, right? Like technology, young people know these things, music, and politics so much that we have experience from the younger generation. Not many people understand what the term BIPOC even means. The younger generation uses that term. Same with the term POC, Black ASL: they use that term. We learn from the older generation and, in turn, use the younger interpreters. Bring us along, teach us, and let us teach you, so we can have more. Also, use the resources that are provided. For example, you can easily take the lessons from my presentation and show students. Call me, and I'll come into a class or workshop or conference. The more information available, the more you grow as an interpreter instead of stagnating in the profession. We consistently have the same people teaching the same information. That makes me think of the idiom, “teaching an old dog new tricks.” That's something that can be done. That's how you recruit new interpreters instead of staying in the same rut.

Jason: So you're saying the word diversity is not suggested. What would you recommend instead?

Amber: My personal take is that DIVERSITY as a sign is neat; it's cool. Yes, we can use that word, but don't use it for “likes.” Don't use this word to show that you're doing this one thing this month to recognize us. Because what happens is that after the event, nothing happens. Part of that was touched on in my presentation. You have white presenters, all white, and they gave terrific presentations. I watched a diversity presentation on a privileged hearing environment. And there was one Deaf man who said, “You don't realize your hearing privilege. In this presentation, we see hearing interpreters scrolling through their devices while listening to the presenters instead of watching the presentation.”

They did not realize that they hired me to come in not to present but to perform at the workshops and conferences. Why? It was performative. To show that they are affirming diversity. We have Black interpreters! And you're showing me off; look at us.

Jason: Tokenism, in other words.

Amber: Yes, that is precisely what it is. I felt like I was a checkmark. Yes, that was how I felt. I didn't turn down the job, and I didn't say no, because you need to know these things, that it is good that they are trying. But you have to understand the background context of why you're using me. These things happen. You have to accept it because now more people can understand the Black ITP experience in Alabama

Jason: Really, that's not solely Alabama, and really that could apply across the field. Of course, there are differences. So for interpreter training programs, what would your advice be, what do you think they could change, and what would be one or two things you advise them to consider? For RID, we will publish in VIEWS. What thoughts that you'd like readers to analyze and think about?

Amber: Be more considerate of your usage of the term diversity. Consider the term's usage, but don't use it only for workshops, conferences or special events. But understand that if you, as a white person from Washington DC, can come to and teach a class, workshop or conference: you can do the same thing with another diverse person. You still have the chance to learn, which can be different learning and the same lessons. As a Black interpreter from an ITP, I hope the staff can become more diversified so that we can remember that sometimes the most certified person in the room may not be the best person.

Jason: Yes, that is true. It's about what is fitting and appropriate. Historically, RID and affiliate chapters in state and local groups tend to talk about their struggles to recruit BIPOC interpreters and students, and professionals. Also, we are facing the fact that there are several -isms and issues, such as audism, racism, sexism and on. What are your thoughts on the changes in the field we need to see? To become more inclusive of different perspectives? You know that we have several organizations, such as NAOBI. But RID affiliate chapters are probably primarily run by white people historically. So what would you share your thoughts for change, and how?

Amber: What do you do when you want to learn sign language? You go to deaf events to improve your signing. You practice and ensure you feel the knowledge and develop the intuition to grow professionally when you become an interpreter.

Why don't people from different organizations try to interact with NAOBI and understand the background and culture? I know many Black interpreters will have group outings, so sometimes those Black interpreters go to their events. Sometimes it's ok because people are afraid to go out of their comfort zone. What happens is that you'll have a group that is fine, saying it's ok we're here, then another group that's saying it's fine to be here. Try to have an event where both groups can be there together. Does that make sense? In Troy, I remember they did a conference, and they got all these different kinds of people to come and participate and teach us these things. I know RID has conferences, and I know NBDA and NAOBI have conferences. But the reason why they are separate is that the information is different. Over here and over here, they are separate. They're getting information, but they're not connected. Does that make sense?

Jason: For example, RID is the only national association accredited to give certification. NAOBI now does not have certification. Should NAOBI partner with RID? It is a historically white-run organization. Is that what you mean?

Amber: I feel like if I'll explain, I feel I'm explaining this wrong. So RID has conferences, right. Yes, national conferences. How many Black, BIPOC, and LGBTQIA workshops do they have? Do they have a full list?

Jason: I remember two years ago, it was entirely online. It had its own member sections in turn.

Amber: You see that? I mean, everyone is siloed and separate. Whereas I want to see and feel like when I go in, they have a full roster of things I can choose from these underrepresented groups. Now I go to these conferences, and I see only one or two events that fit me. But if I went to the NAOBI and NBDA conferences, they would have a full slate of events. If you went to that, you would see multiple offerings; you could choose, but you wouldn't know what to choose because you've never been to an NBDA conference, you've never had that experience, you've never had the opportunity to learn, you had it, but you were unsure, I don't know. So right now, that world looks like now, I don't know. It's hard because —

Jason: Yeah, in the last few years, we have had the George Floyd situation in Minnesota, BLM Black Lives Matter, you start to think about the visibility and the other women's rights and the recent Roe vs. Wade decision. There are a lot of political situations now coming that impact us. Of course, that affects what the Deaf community faces. You have marginalized communities facing different issues. So are you

encouraging regular white members of RID to attend these conferences? The general sentiment will be, they will say — that's their safe space. I won't go because the Black community needs their time like Deaf people would say, or LGBTQIA, it is their time and space. Do you feel a need to change that thinking?

Amber: Let's keep the safe space as a safe space. Each group needs to have a safe space. I understand that because I would love to go into a space and feel relaxed knowing we all understand each other and share the same experiences. That would be fine. But a one-time event where all can attend and participate in multiple events. In a perfect world, I can see that. But now it's an iffy proposition. You have to wait and see.

Jason: I'm now curious about affiliate chapters in RID. We can talk about that at length; you mentioned that there are two separate organizations like NAOBI, then NBDA. Then there are RID and the state chapters, like ALRID, Florida RID, and all of our affiliate chapters. I know we need more collaboration, but I still see the struggle in forming a collaboration. Do you feel its regression, … obviously there is history there in colonialism. How could we — what does that look like to you regarding a successful partnership? And not feeling like tokenism?

Amber: It's not the organization. It's the people in them. You have some people you feel you can't work with and need to distance yourself from them. Those people tend to be privileged in those organizations, which is hard to challenge. It takes work to try to partner with that. Because you feel that there is doubt and distrust and that it is not a safe space for me, not that you want to try. I can only describe my experience from what I understand. It is people who will ask for partnership, but they choose the wrong time, or they choose —

Jason: Maybe like Black history month, for example?

Amber: Yes, or concerning the BIPOC example. They always send us messages and emails, but on a dayto-day basis, we don't get a lot of contact from them. The people that we want to partner with are the people that want to get involved. It's not a large Black interpreting community here in Alabama, it's small, but we are still tight. You start to discover and recognize and learn to temper your excitement and learn the daily struggles that Black interpreters face to face tokenism, colorism, racism — oh, that one is a big one. Black people who are not interpreters are really killed for everyday things.

Dr. Melanie McKay-Cody is a Cherokee Deaf and earned her doctoral degree in linguistic and socio-cultural anthropology at the University of Oklahoma. She has studied critically-endangered Indigenous Sign Languages in North America since 1994 and helps different tribes preserve their tribal signs. She also specialized in Indigenous Deaf studies and interpreter training incorporating Native culture, North American Indian Sign Language and ASL. She is also an educator and advocate for Indigenous interpreters and students in educational settings. Besides, North American Indian Sign Language research, she had taught ASL classes in several universities, schools and community for over 42 years. She is one of eight founders of Turtle Island Hand Talk, a new group focused on Indigenous Deaf/Hard of Hearing/DeafBlind and Hearing people.

By Melanie McKay-Cody, PhD

By Melanie McKay-Cody, PhD

*This is a reprint from the Feb 2020 VIEWS edition.

Hi, I’m Dr. Melanie McKay-Cody, presenting to you this protocol for interpreting in native settings. This topic arose because Indigenous Deaf people felt that ITPs and other interpreter preparation programs don’t meet our communal needs. The training is not appropriate for interpreting in native settings. Due to many issues related to that, we decided to establish this protocol. The work on this protocol started in July 2018 as we carefully crafted the different pieces and finally made it ready for publication and dissemination in May 2019. In this protocol we emphasize the five R’s: Respect, Relationship, Responsibility, Relevance, and Reciprocity. This represents our way of knowing, being, and doing, and is part of our Indigenous Deaf Methodologies, as opposed to Western philosophies used in many ASL and Deaf studies programs.

Note: For all jobs/assignments that Sign Language Interpreters conduct, every interpreter must have credentials for American Sign Language or Lengua de señas mexicana (LSM) and/or Indigenous/ tribal sign language. American Sign Language

requires certification in USA and Canada. There is no certification for Lengua de señas mexicana nor Mexican Indigenous sign languages in Mexico. There is no certification for Indigenous/tribal sign language in USA and Canada, the preference given to the interpreters who have years of experience and training with authentic tribal sign language instructors.

Approach/Philosophy:

1. Whereas it is typical for an interpreter to approach an interpreting assignment as a means of income and a profession that can be seen as a “job,” the Indigenous community asks for a shift in perception and a personcentered approach.

2. The Indigenous community encourages the interpreter to first consider the consumers of the interpretation services and to hold them as sacred; this means to consider both the Deaf and Hearing participants and their life journey, and what they mean to accomplish at this crossroad in their lives.

3. An Indigenous event or ceremony is not merely an interpreting assignment. Instead the event should be viewed as an opportunity for interpreters to bridge Deaf and Hearing participants' unfolding life journeys that manifest in Indigenous events and ceremonies.

4. Regardless of intention or lack thereof, an interpreter makes an impact on the settings they work within and the people they interpret for. The Indigenous community asks the interpreter to take this all into consideration; to honor and respect the Indigenous community, and to have an open approach since Indigenous customs and values may be different than the interpreter's.

5. If the interpreter is in need of cultural mediation, for understanding or clarification, the interpreter should ask the designated Indigenous coordinator or appropriate contact person and not the first person nearby.

6. The Indigenous community thanks interpreters who wish to serve their community.

Indigenous Deaf people:

7. Understand that not all Indigenous Deaf people are knowledgeable (e.g. customs, values, traditions, history) about their tribes.

8. Be aware that consumers may have different signs than what an interpreter may have learned or uses on a regular basis. It is crucial for interpreters to accept instruction on preferred signs from the people they are working with at any given time, and to incorporate and use these signs as best they can.

9. When an Indigenous Deaf signer conducts a sacred ceremony in Tribal sign language (Plains Indian Sign Language, Northeast Indian Sign Language, and other language varieties within the North American Indian Sign Language), and interpreters do not know specific signs, the sign language interpreter should explain to the hearing Indigenous audience that s/he is signing in tribal signs. Furthermore, not all tribes use Plains Indian Sign Language, other tribes outside of Plains region may use their own sign languages.

Indigenous hearing people:

10. When appropriate, talk with the hearing Indigenous people to discuss the cultural and language deprivation that Indigenous Deaf people experience,

beforehand, unless Indigenous Deaf people prefer to explain their unique situation themselves (this engages use of their own Indigenous Deaf agency).

11. Do not be afraid to ask the Indigenous leader/ presenter/teacher/elder and others what terms to use in interpreting beforehand. When in the service of interpreting, an interpreter may encounter the speaker switching from English to their native tongue throughout their communication. A non-Indigenous interpreter may need to switch off with a team of Native interpreters during this time. Recognize your limitations and respect boundaries in such events, as an interpreter’s job is interpreting.

12. Oftentimes, the person speaking will utilize their tribal spoken language. An interpreter can ask them to repeat the word by spelling the words. Most people are open to helping out with the tribal words. This is important as Indigenous interpreters are not universally available (i.e. University/college classrooms, general meetings, or tribal events in urban cities).

13. It is common on the Reservation/Reserve/ Nations/Village/and other places to select “any person who know signs” to interpret. These persons (Indigenous or Non-Indigenous) should not be considered “an interpreter” because they are not qualified to translate the message. Failure to provide qualified interpreters can have grave/disastrous consequences (such as wrong placement like jail, educational placement) for Indigenous Deaf people. Tribal offices need to be educated about these problematic issues.

14. Interpreters who interpret sacred ceremonies, need to be aware that American Sign Language or Language of Signed Mexican books do not cover such tribal words that may be spoken. The Indigenous and non-Indigenous interpreters who are well versed in tribal signs would be the best fit to interpret at these tribal events, meetings, and other type of tribal activities.

15. It is best to acquire tribal signs when interpreting for an Indigenous Deaf person. It is recommended that interpreters specializing in Indigenous Deaf interpreting to attend workshops that provide this knowledge and the continuation of professional development in this area.

16. Be aware that even though index-finger-pointing is considered rude and culturally unacceptable in most

Indigenous communities, it is allowed to be used with Indigenous Deaf persons by interpreters, and some bi-culturally educated Indigenous people, since ASL and LSM use index-finger-pointing for pronouns and directional purposes etc., while Indigenous/tribal sign languages do not use index-finger-pointing.

17. Instead of index-finger-pointing, as it is generally considered rude among most Indigenous communities, it is more appropriate to refer to the speaker/ presenter/signer with full-hand acknowledgement. It is common for Indigenous interpreters to do lip-pointing because it may be part of their culture.

18. It is the interpreter’s responsibility to ask about what topic will need interpretation, and what should not or cannot be interpreted.

19. Be aware that some sacred prayers by tribal spiritual leaders may not be interpreted. At times Interpreters/individuals may need consent to be present where such sacredness is happening. For example, some dancers are to stay silent and are not to be touched. Know your boundaries, and theirs, within the culture.

20. Interpreters may not bring counterparts such as people/family to become audiences within such events to take photos without permission of a spiritual leader. Within certain tribes photography is strongly forbidden, as their ceremonies are not made open to the public.

21. Be aware that there is a difference between a paid service and a gift (usually during community events). Not all interpreting assignment are paying jobs. Do not expect monetary payment for your service unless agreed to beforehand. Conferences, college/university jobs, and some meetings will provide payment.

22. Social media—interpreters are required to refrain from posting anything on Facebook, and any social media format that reveals picture of people, or names from your assignment. This is a viewpoint of self-promotion, it does not address inadvertent (and careless) revealing of client information. Any social media posting, check with appropriate Indigenous people to verify authenticity before you post.

23. Criminal conviction—Human Resources at tribal office and specific assigned Indigenous Deaf Elders will be in charge of background checking on interpreter’s criminal conviction record, if situation raises. It is important that we protect Indigenous people from any harm.

24. If you are non-native or from another tribe, it is extremely important to recognize and respect others’ Indigenous beliefs as distinct from your own. If you feel that you cannot separate your religious beliefs in an Indigenous setting, do not accept the assignment. It is best not to take the assignment if you feel you cannot put aside those personal religious beliefs that counter those of the culture you would interpret within.

Clothing:

25. Sign Language interpreters are responsible to ask the tribal/council people or the Indigenous Deaf people about what to wear at certain events. Generally, typical business attire is worn for conference-type scenarios, and casual clothing for outdoor or tribal events. You do not want to look inappropriately dressed at certain events.

26. Interpreter’s garments, if ceremony or gathering participants have colorful regalia/traditional clothes then the interpreter need not come in black clothing as to dampen the spirit of the ceremony, but instead can use a light or lighter color, so long as it is muted and does not detract, overpower, or distract from the ceremonial regalia/traditional clothes.

27. During sweat lodge activity, check with each tribe’s traditional spiritual leader(s) on appropriate clothing and conduct within the lodge.

28. When providing interpretation at outdoor events, be mindful of weather, heat, and duration of the cultural event—the community may not have a strict timeline to start and end.

29. Indigenous Deaf people and interpreters are partners in communication at all tribal events. Indigenous Deaf people will choose certain interpreter(s) they are comfortable with and whom

they deem qualified, regardless of their certification levels.

30. In colleges/universities, Indigenous Deaf people have the right to choose their designated interpreters because of their knowledge in tribal culture, language, and traditional ways. This practice aligns with standard human resources practices on Tribal lands where they seek to hire Indigenous interpreters.

31. Status and role of Indigenous people: Elders are treated with great respect. The tone of interpreting for an Elder is equivalent to that of interpreting for a person who has a PhD. Spiritual Leaders are afforded the same respect and status.

32. Turn-taking in Indigenous communities differs from non-Indigenous communities, “certain American Indian groups are accustomed to waiting several minutes in silence before responding to a question or taking a turn in conversation, while the native English speakers they may be talking to have very short time frames for responses or conversational turn-taking, and find long silences embarrassing” (Saville-Troike, 2003:18). The sign language interpreter can inform the Indigenous or non-Indigenous Deaf/HH/DB at these

times to, “hold, still thinking,” which is preferable to “wait in silence.”

Gender-Specific Information:

33. Within most tribes, women (including both participants and interpreters) are not allowed to engage in sacred Indigenous ceremonies during menstruation. In tribes that follow this practice, prior to a sacred ceremony, spiritual leaders might approach Indigenous Deaf women and women interpreters about this restriction, although it may be assumed this is common knowledge. A replacement by another sign language interpreter during such a time is a must. Note: not all tribes practice this belief. This would apply to the Indigenous Deaf person and interpreter who is participating in a sacred ceremony. An interpreter at this type of event would be a shadow, who only interprets the ceremony without participating in it. Remember, an interpreter is an outsider in such scenarios, and one who comes to convey communication of what is voiced or signed.

Be aware that certain ceremonies or sweat lodges have gender-specific protocols (female interpreters cannot go near all-male ceremonies or sweat lodges, and vice versa for male interpreters).

a. At some tribal events, there are certain gender-specific spaces; interpreter(s) need to talk to spiritual leader/elder/community leader about where you need to stand or sit prior to the event.

b. Be aware some tribal sweat lodges might require one to be unclothed. Interpreters need to be aware of this beforehand. Note: rarely is this a mixed-gendered occurrence.

35. Make ceremony or signing/talking circle plans for interpreter logistics, depending on the number of sign language interpreters present. If there are many interpreters, a placement of four chairs set in cardinal directions inside the circle would be recommended. If there are only 2 interpreters, it will mean each interpreter should take 2 cardinal directions. A category of different diagrams is attached to this protocol. Keep in mind, not all tribes have similar ceremonies or signing/talking circles. Talk to the hearing and/or Deaf leader/elders who are in charge, get their instructions, and ask for pre-ceremony preparation.

36. The placement of the interpreters in a ceremony is key and dependent on the participant’s preference. A common expectation is for interpreters to be outside the circle yet still in the line of sight to those watching the interpreter. There exist many tribes in Mexico and a standardized interpreting system is not in place because of so much diversity. At this point it is best for an interpreter to take guidance from the local tribe they are being asked to work with.

Awareness:

Be aware and conscientious that the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) standards do not apply to Native Reservations in the USA. The same is true for the Association of Visual Language Interpreters of Canada (AVLIC) for Canada. There is no certification system in Mexico.

38. Eye Contact—It is important to know that eye contact between the sign language interpreters and Indigenous Deaf people is acceptable, but when you

are in Indigenous communities, do not ask or demand an Indigenous person/people to make eye contact with you or the Indigenous Deaf person, it might be their cultural protocol to not make eye contact.

Dances or Tribal Events:

39. When any Indigenous Deaf or Indigenous hearing person asks you to participate in any event or dance, do not decline the offer, it might be perceived as disrespectful to the Indigenous people.

40. Interpreters can participate in giveaways or blanket dance, which involves a donation to the Indigenous hearing or Deaf people who need the funds to go back home or for a certain purpose.

41. Above all else, it is best to ask an Indigenous person involved with the activity first, and to prepare and provide your service accordingly.

This protocol has been developed by Melanie McKayCody (Cherokee), Armando Castro (Mixteca), Tim Curry (Non-Indigenous), Amy Fowler (Non-Indigenous), Ren Freeman (Eastern Shoshone/First Nation Cree), Crescenciano Garcia, JR. (Aztec), Paola Morales (Nahua/Pipil and afromestiza) Evelyn Optiz (San Carlos Apache) and Wanette Reynolds (Cherokee). Reviewed by Kevin Goodfeather (Dakota), Natasha Terry (Navajo), Hallie Zimmerman (Winnebago), and James Wooden Legs (Northern Cheyenne).

About the Author

Dr. Melanie McKay-Cody is a Cherokee Deaf and earned her doctoral degree in linguistic and sociocultural anthropology at the University of Oklahoma. She has studied critically-endangered indigenous sign languages in North America since 1994 and helps different tribes preserve their tribal signs. She also specialized in Indigenous Deaf studies and interpreter training incorporating Native culture, North American Indian Sign Language and ASL.

This article was originally published as Dr. MckayCody’s PhD Dissertation, “Memory Comes Before Knowledge-North American Indigenous Deaf: Sociocultural Study of Rock/Picture Writing, Community, Sign Languages, and Kinship.” University of Oklahoma, p. 312-325.

Dr. Anthony Aramburo was the first president of the National Alliance of Black Interpreters (NAOBI), and was instrumental in establishing American Sign Language classes at Xavier University. He served on the RID Board of Directors as Member-at-Large, was a Journal of Interpretation Editor, a member of the RID Diversity Committee, Chair of the ITOC Member Section, co-chaired two national RID conferences and served on the Center for the Assessment of Sign Language Interpreting (CASLI) board. In 1999, Dr. Aramburo was presented with the Judie Hustead Leadership award at RID’s conference in Boston, MA.

As interpreters, we find ourselves involved in the facilitation of communication for individuals in various settings. Based on our signing skill level, interpreter preparation background and ability to perform in a particular arena, the success of our efforts are measured. As surmised by the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf Code of Ethics, there are situations from which an interpreter will excuse him or herself based on one or more factors.

Prior to accepting any interpreting assignment, it behooves an interpreter to become familiar with the interpreting situation and to have a command of the language the Deaf or hard of hearing individual will be using. Granted, this is not always possible, but having knowledge of the situation, be it interpreting for a DeafBlind individual, a person who is Hard of Hearing and has Cerebral Palsy or a Hispanic or African-American Deaf individual, will determine the effectiveness in getting the message across.

Culturally, the Deaf community is made up of a variety of individuals that demonstrate the diverse talents needed in providing sign language communication.

Within the general Deaf community, different ethnic and cultural minorities are prevalent. Each ethnic group, each cultural minority clings to their heritage, while applying their actions and feelings to daily living activities in the general Deaf community. Ethnic groups contribute significantly to the makeup of society, each contributing their unique cultural gifts and ideas to enhance society.

African-Americans, Native Americans, Hispanics, and Asians, to name a few, all make up the melting pot of America. Just as these culturally diverse groups are found within the general community, so too are their members incorporated in the Deaf community. The Deaf community in comparison to the general community can be considered a cultural minority. The language used by its members and the distinct cultural nuances are what helps to differentiate this cultural group from others. It is from this cultural majority, in this sense, that I choose to elaborate on a subculture within the Deaf community, the AfricanAmerican Deaf community. Deaf African-Americans share the same cultural richness as African-Americans.

In a survey conducted by this author, 87% of the African-American Deaf participants said that they identify with their African-American culture before they identify with their Deaf culture. As pointed out by several participants, they indicated a person sees their color before they recognize they are Deaf. Interpreters working with African-American Deaf individuals would be remiss if they were not conscious of certain cultural properties relevant to this community. Often, what may be seen as inappropriate behavior for certain members outside of the African-American Deaf culture, to its members, would be considered appropriate behavior.

For members of the African-American Deaf community, the reality of the matter is that they do not have the luxury of requesting African-American interpreters to assist in their communication needs. In a survey conducted by the National Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, an overwhelming 92.4% of the individuals responding to the survey are Caucasian.

Those interpreters identifying with a specific ethnic minority made up 6.4% of the respondents. Recruitment of minorities into the field of interpreting is an agenda item for many Interpreter Preparation Programs. Until recently, African-Americans were not as extensively involved in the field of interpreting. Many were in church settings. However few certified African-Americans were actively engaged in the profession. Within the National Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, one of the Special Interest Groups, Interpreters/Transliterators of Color (ITOC), works at identifying and fostering minority interpreters into the profession. Still, judging from the statistics previously mentioned, it is going to take a considerable amount of time to get the numbers to where the ratio of minority interpreters is in sync with Caucasian interpreters.

Linguistic differences have been noted relevant to the way African-American Deaf individuals sign when researched with Caucasian Deaf individuals. The research findings indicate that when two AfricanAmericans are conversing amongst themselves, their primary mode of communication is American Sign Language. This is true also in instances when an African-American Deaf individual and a Caucasian Deaf individual are conversing. Where the difference lies is the form of signing used by two AfricanAmerican Deaf individuals and the signs used when conversing with Caucasian Deaf individuals.

During the days when schools were segregated, African-American Deaf students were educated in a setting that catered to an all AfricanAmerican student population. Not being able to interact with Caucasian Deaf students academically or for extra-curricular reasons, students at the all African-American schools competed with other neighboring schools of all African-Americans either in state or out of state. When students from out of state visited another school to compete, they brought with them signs that were indigenous to their area. Many of the older forms of sign language used by the older African-American Deaf are still around. Unknowingly, many of the signs are passed on to younger members.

In proportion to societal limitations placed on members of this minority group, as with numerous other minority groups, service providers working with these individuals find themselves working with the grass root members of that community. As for interpreters, in particular those working with the grass root members of the African-American Deaf community, the aforementioned information should serve to assist in providing a more comprehensive measure of interpreting.

Keeping in mind that culturally, linguistically, educationally and socially, African-American Deaf individuals delight in a rich subculture contributing to the diverseness that makes up the general Deaf community.

Originally printed June 1993.

Below is a link to a page on the RID website, accessible to the community at large, that lists individuals whose certifications have been revoked due to non-compliance with the Certification Maintenance Program or by reasons stated in the RID PPM.

The Certification Maintenance Program requirements are:

> Maintain current RID membership by paying annual RID Certified Member dues

> Meet the CEU requirements:

• 8.0 total CEUs with at least 6.0 in PS CEUs

• A minimum of 1.0 of the 6.0 PS CEUs must be in the area of PPO

• Up to 2.0 GS CEUs may be applied toward the requirement

• SC:L only–2.0 of the 6.0 PS CEUs must be in legal interpreting topics

• SC:PA only–2.0 of the 6.0 PS CEUs must be in performing arts topics

> Adhere to the RID Code of Professional Conduct

If an individual appears on the list, it means that consumers working with this interpreter may no longer be protected by the Ethical Practices System should an issue arise. The published list is a “live” list, meaning that it will be updated if a certification is reinstated or revoked. To view the revocation list, please visit HERE

Should a member lose certification due to failure to comply with CEU requirements or failure to pay membership dues, that individual may submit a reinstatement request.The reinstatement form and policies are outlined HERE.

VIEWS, RID’s digital publication, is dedicated to the interpreting profession. As a part of RID’s strategic goals, we focus on providing interpreters with the educational tools they need to excel at their profession. VIEWS is about inspiring, or even instigating, thoughtful discussions among practitioners. With the establishment of the VIEWS Board of Editors, the featured content in this publication is peer-reviewed and standardized according to our bilingual review process. VIEWS is on the leading edge of bilingual publications for English and ASL. In this way, VIEWS helps to bridge the gap between interpreters and clients and facilitate equality of language. This publication represents a rich history of knowledge-sharing in an extremely diverse profession. As an organization, we value the experiences and expertise of interpreters from every cultural, linguistic, and educational background. VIEWS seeks to provide information to researchers and stakeholders about these specialty fields and groups in the interpreting profession. We aim to explore the interpreter’s role within this demanding social and political environment by promoting content with complex layers of experience and meaning.

While we publish updates on our website and social media platforms, unique information from the following areas can only be found in VIEWS:

• Both research- and peer-based articles/columns

• Interpreting skill-building and continuing education opportunities

• Local, national, and international interpreting news

• Reports on the Certification Program

• RID committee and Member Sections news

• New publications available from RID Press

• News and highlights from RID Headquarters

Submissions:

VIEWS publishes articles on matters of interest and concern to the membership. Submissions that are essentially interpersonal exchanges, editorials or statements of opinion are not appropriate as articles and may remain unpublished, run as a letter to the editor or as a position paper. Submissions that are simply the description of programs and services in the community with no discussion may also be redirected to a more archival platform on the website. Articles should be 1,800 words or fewer. Unsigned articles will not be published. Please contact the editor of VIEWS if you require more space. RID reserves the right to limit the quantity and frequency of articles published in VIEWS written by a single author(s). Receipt by RID of a submission does not guarantee its publication. RID reserves the right to edit, excerpt or refuse to publish any submission. Publication of an advertisement does not constitute RID’s endorsement or approval of the advertiser, nor does RID guarantee the accuracy of information given in an advertisement.

Advertising specifications can be found at www.rid.org, or by contacting the editor. All editorial, advertising, submission and permission inquiries should be directed to (703) 838-0030, (703) 838-0454 fax, or publications@rid.org.

Copyright:

VIEWS is published quarterly by the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, Inc. Statements of fact or opinion are the responsibility of the authors alone and do not necessarily represent the opinion of RID. The author(s), not RID, is responsible for the content of submissions published in VIEWS.

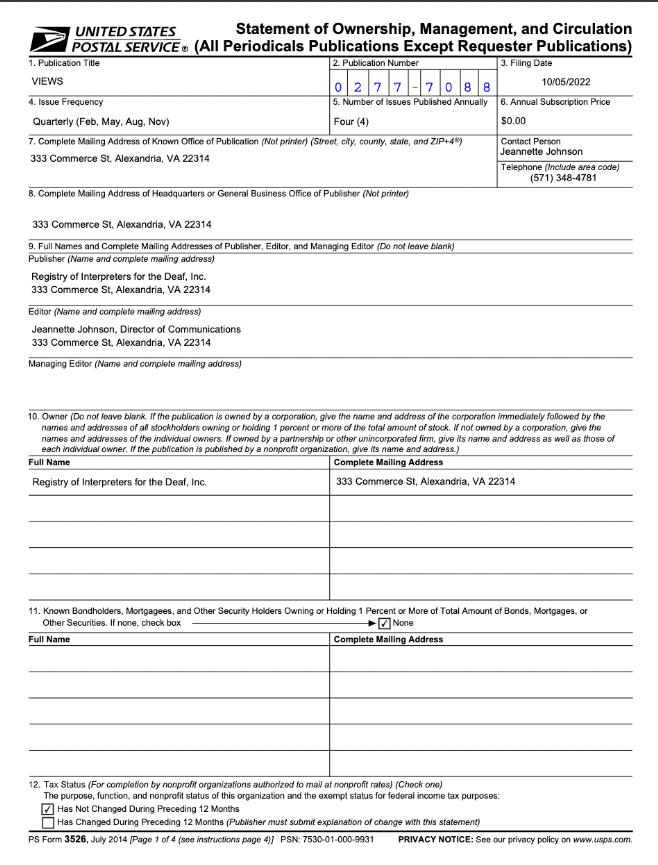

Statement of Ownership:

VIEWS (ISSN 0277-7088) is published quarterly by the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, Inc. Periodical postage paid in Stone Mountain, GA and other mailing offices by The Sauers Group, Inc. Materials may not be reproduced or reprinted in whole or in part without written permission. Contact views@rid.org for permission inquiries and requests.

VIEWS’ electronic subscription is a membership benefit and is covered in the cost of RID membership dues.

VIEWS Board of Editors

Elisa Maroney, CI and CT, NIC, Ed:K-12

Kelly Brakenhoff, NIC

Royce Carpenter, MA, NIC Master

Amy Parsons, Associate Member

© 2023 Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, Inc. All rights reserved.