ENGINEERING HEALTHCARE by Lango Deen ldeen@ccgmag.com

J

aneen Uzzell had been working at GE Medical Systems (now GE Healthcare) for about five years by the summer of

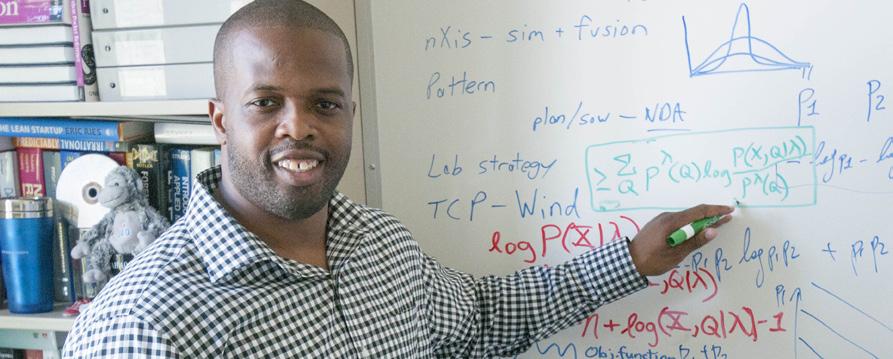

2007 when health-care leaders across America met at an annual senior executive event. The conference’s theme was “The Future is Now: Effective Leadership in a Global Healthcare Environment.” Five thousand miles away in Ghana, the GE Foundation, the philanthropic arm of GE, had launched its Developing Health Globally initiative, providing medical equipment, water desalination units, and power generators to the West African country’s resource-poor hospitals, health centers and maternal child health posts. Yet one of the keynote speakers at the four-day event was unimpressed. An international consultant in healthcare, he compared the American system to the MTV show, “Pimp My Ride,” where a rapper and his crew transform an old vehicle into a flashy, moving music sound station, reported a St. Thomas newspaper. “American health care places unbelievable amounts of high technology into a frame that is fired by an old, ineffective engine,” he said. Its system “rewards procedures, and not keeping people healthy.” But GE professionals like Uzzell were in “the grind” with “eyes on the ground” providing “diversity of thought, creativity, and decision-making.” Inspired by her mother, a successful businesswoman, and an older sister who was a nurse, Uzzell often dreamed of wearing a white swan Janeen Uzzell Global Director of Operations, uniform someday, but an older cousin who was studying GE Global Research, External Affairs, engineering motivated her to take a different path. and Technology Programs Although Uzzell started with an engineering 14 USBE&IT | DIGITAL ISSUE 2017

www.blackengineer.com