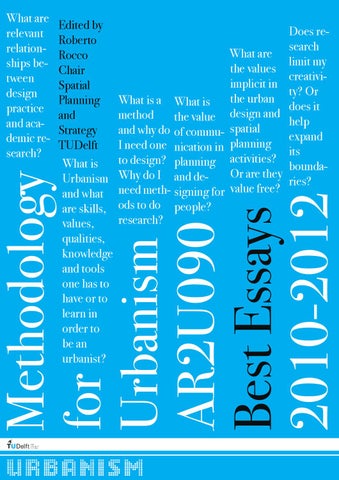

Edited by Roberto Rocco Chair Spatial Planning and Strategy TUDelft What is Urbanism and what are skills, values, qualities, knowledge and tools one has to have or to learn in order to be an urbanist?

Does research What are limit my the values creativiimplicit in ty? Or the urban What is a What is does it design and method the value help and why do of commu- spatial expand planning I need one nication in its to design? planning activities? boundaOr are they Why do I and deries? value free? need meth- signing for ods to do people? research?

Methodology for Urbanism AR2U090 Best Essays 2010-2012

What are relevant relationships between design practice and academic research?

1