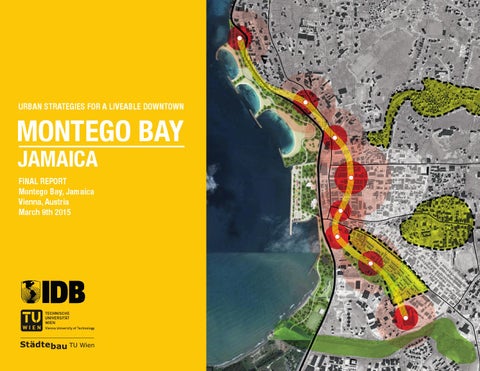

URBAN STRATEGIES FOR A LIVEABLE DOWNTOWN

MONTEGO BAY JAMAICA FINAL REPORT Montego Bay, Jamaica Vienna, Austria March 9th 2015

FINAL REPORT MONTEGO BAY 路 JAMAICA

2

INDEX CONTENT 5 8 12 16 16 24 34 36

Introduction to the Urban Issues in Montego Bay Future Urban Growth Scenarios for Montego Bay Analysis of the Urban Footprint Main Actions Creation of a new Waterfront for Montego Bay Integral Neighborhood Upgrading Strategy and Pilot Downtown Housing Project Revitalization of the Charles Gordon Market Other recommended actions

Project supervisor: Andr茅s Blanco Blanco, PhD MSc Design Team: Roland Krebs, MSc Urb Sabrina Ehrenh枚fer, BSc Arch Klaus Kodydek, BSc Arch Peter Scheibstock, BSc Arch Advisors: Sarah Benton, MSc. Urb Rebecca Sabo, BSFS Photo Credits: Ram贸n Zamora, MSc Arch Vienna, Austria 2015

5

MAP OF LAND USE MAP OF SUSCEPTIBILITY OF SELECTED HAZARDS

INTRODUCTION TO THE URBAN ISSUES IN MONTEGO BAY The urban core of Montego Bay is composed of 38 neighborhoods which have a combined population of 110,115. Historically, planned urban development has occurred within the center of the city and along the coastline. Since the early eighties, most formal and informal housing development activities have been concentrated in the hills on the outskirts of the city. On the other hand, hotels and resort complexes are no longer developed close to the main Gloucester Avenue commercial axis (“Hip Strip”), but instead have been emerging along the coast, to the east of the Sangster International Airport. Over the past three decades, the city has continued to grow on the periphery, mostly in the form of low-density informal settlements. The city is operating under a zoning plan that was approved in 1983 and needs to be updated to reflect the current reality, residents’ needs, and modern planning practices. An absence of regulations and

>> >>>>

urban growth management has led to large, widespread, and unplanned new developments in areas unfit for urbanization, such as areas exposed to natural hazards such as flooding and landslides. The historic city center of Montego Bay lacks residences and has high congestion caused by mainly vehicular traffic and an inefficient public transportation system. Over the past 30 years, the city’s downtown area has become a central business district with banks, services, a public library, markets, schools, hospitals, and clinics, and has many important functions and uses. The commercialization of downtown for these purposes has resulted in a decline in its importance as a hospitality center and residential area. This kind of urban fragmentation leads to inefficient urban development. This includes a strong dependency on automobiles and high maintenance costs for road infrastructure, sewerage, and other public services. This also results in an inappropriate environmental footprint in terms of pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, and inefficiency in the use of resources. The abandonment of the downtown area after 6 pm, by employees, customers, and pupils, is a manifestation of this fragmentation. Only a small proportion of tourists venture to downtown Montego Bay to see its historical buildings and traditional markets.

8

FINAL REPORT MONTEGO BAY · JAMAICA

FUTURE URBAN GROWTH SCENARIOS FOR MONTEGO BAY Montego Bay has been experiencing significant changes in regards to its urban footprint, reflected through the changes in growth patterns on the periphery of the city. Some of these changes are occurring as a reflection of the change in the paradigm shift of urban typologies (lower density suburban development, migration of residents from the urban core). In part as a result of unplanned development and to a certain extent a lack of enforcement of current city zoning and planning policies. These changes place the city at a critical planning stage. In the future, the city will either thrive as the region continues to grow or the city’s growth will exceed the capacity of the urban systems to serve its residents and threaten the city’s role in the regional economy. These reasons have led to the realization that it is necessary to explore different paths of development within the region, focusing not only on the variation of the population but also city’s

URBAN SPRAWL AS AN URBAN TYPOLOGY

policy and infrastructure network. In an effort to explore future growth patterns and the associated impacts, the consultant team of GeoAdaptive has developed two scenarios for Montego Bay, distinct in nature to serve as a tool for local decision makers to increase their understanding of the impacts and consequences associated with each type of growth. The scenarios also provide a means to compare the different amounts of capital investment required to provide basic urban services to their residents (when the data is available), such as potable water, sewers and roads, within the projected areas of growth. There are four main categorical differences at the policy level that guide the assumptions used as inputs for each scenario. The most important differences between the trend and the smart-growth scenarios are based on a set of urban policies associated with the following factors:

1. Urban and Natural Systems Coordination The city and its surrounding areas were studied through a rapid evaluation process to quickly to identify possible synergies

>>

and connections, which could be implemented throughout city. This analysis was based on the identification of areas that met the following criteria: aid with urban and stormwater runoff, improve water quality, regulate local temperatures and improve air quality, contribute to flooding prevention and control, provide recreational services, and provide the city with habitat and ecological connectivity. These areas were identified by experts on the consultant team and validated with local experts.

2. Zoning and Land Use Restrictions Zoning is a mechanism of land management used by local government whose primary purpose is to restrict uses that are incompatible with current conditions or go against current development orders. Zoning can also regulate the principal use of the land and development density. The team of analysts used the St. James Development Order (2010-draft) to estimate residential densities for the smart growth scenario simulation.

3. New and Improved Infrastructures The location of existing infrastructure provides the basis for evaluating the most attractive areas for urban development.

9

One of the key inputs for the RGAM is the development of a spatial model (attractiveness model) which determines the proximity of new residential areas to areas of services (transportation, commercial areas, open spaces, school, etc.).

4. Density Urban density is a specific measure that refers to the number of residents in a particular area and is typically measured in residents per hectares (p/ha). Future urban density assumptions should be related the availability of local public services and the infrastructure that supports these. The consultant team performed a series of calculations to determine the acceptable urban density by reviewing existing conditions (during field visits and through the interpretation of satellite imagery) and the correlation between these conditions, census data and levels of density. Regional and local standards of urban density in the Caribbean and Latin American were considered as reference points for this study. From: Historical and Current Urban Footprint and Future Urban Scenarios, GeoAdaptive, LLC (2014)

12

FINAL REPORT MONTEGO BAY · JAMAICA

ANALYSIS OF THE URBAN FOOTPRINT The Historical and Current Urban Footprint and Future Urban Scenarios study shows that Montego Bay’s population will grow by 23,262 people between now and 2030, resulting in a estimated population of 133,477 residents at that time. If current development patterns continue, that population growth will result in the urbanization of 492 hectares acres of land, which will be added to the existing urban footprint.

A WALKABLE DOWNTOWN AS A STRATEGY FOR MONTEGO BAY

94%, or 464 hectares, of the new urban growth area will be low to medium density urban sprawl. Only 28 hectares are projected to be demanded for high-density development, meaning the construction of dense multi-family housing types. In this scenario, the city government would have to spend approximately J$ 1.64 billion in infrastructure to meet the demand. In comparison, a smart growth scenario with more compact patterns and high density and infill developments would require only 275 hectares of new developed land and much lower infrastructure costs (J$ 842 million) to meet the population’s needs.

>>

Over the medium and long term, Montego Bay will tackle these urban issues through a more proactive urban growth management strategy favoring investments in the downtown area. The traffic volume should decrease, particularly if additional housing is made available by increasing density and redeveloping properties for residential use. The center will be enhanced by inclusionary open and green spaces for its residents and tourists. The implementation of a smart growth scenario and selected mitigation measures concerning solid waste treatment, energy efficiency, and vehicle fuel switch, as suggested by the Historical and Current Urban Footprint and Future Urban Scenarios study, would reduce the emissions projected for 2030 from 1.215 million tons CO2e, to 857,000 tons, a 30% decrease. There are still large areas of undeveloped or underutilized land, including the whole shoreline by the downtown area (including the Hip Strip), that have great potential for park and beach facilities. However, the city is vulnerable to a variety of hazards which have the potential to cause significant damage in commercial and residential areas. Storm surge presents a threat to not only the resorts but also to the downtown. A major hurricane could be devastating

14

FINAL REPORT MONTEGO BAY · JAMAICA

RECOMMENDED ACTIONS IN DOWNTOWN MONTEGO BAY

>>

to the tourism industry, which is central to the local economy. In the Action Plan on Reduction of Vulnerability to Natural and Man-Made Disasters, emphasis is placed on disaster risk mitigation. This chapter describes the main problems in each of the priority action areas identified in the previous phases of the methodology, and outlines the actions that will be taken to address these issues. Although the actions are organized by action area, the plans themselves were developed in conjunction with one another, by a multidisciplinary team working together to determine how to optimize resources to achieve the greatest possible benefit for the city of Montego Bay.

URBAN DEVELOPMENT & MOBILITY The following urban planning and mobilitiy strategy for Montego Bay will manage rapid urban growth at the urban fringes and revitalize the downtown area. The urban interventions comprise a strategy to transform Montego Bay into a sustainable city. These interventions aim to: (i) update the Parish Council’s existing urban planning toolkit, especially for the city centre; (ii) decrease traffic, improve walkable connectivity, and reduce greenhouse gas

Concentration of north bound taxi stands

Integrated Waterfront Park Project

Intermodal North Transportation Hub Public Library

Beach facilities and equipment

Urban Design of the public space around library

Design of a Boardwalk Beach facilities and equipment

lly

h Gu

Harbo ur Str eet

Nort

Union Street

Pedestrianization Pilot Project and Phase 1

Downtown Walkability Project Participatory Urban Design of Sam Sharpe Square

ok Howard Co

Montego Bay Cultural Centre Pedestrianization Phase 2

e Highway

Creek Street

Barn

TRANSPORTATION CENTER

ett S treet

Pilot Downtown Housing Project Inclusionary design of Social Housing Incremental Housing min. 1,0 FAR

Potential Recreational Park Create accessability

Ba

rne

tt S tre

et

Gordon Market Upgrade Project Participatory Urban Design

16

FINAL REPORT MONTEGO BAY · JAMAICA

emissions; (iii) revitalize the city centre and renovate its housing stock; (iv) rehabilitate the built cultural heritage; (v) restore the traditional market; and (vi) improve public and green spaces while reducing vulnerability in case of extreme weather events.

MAIN ACTIONS The Downtown area of Montego Bay needs a special strategy for its comprehensive upgrade. The new Development Order should include a plan for downtown Montego Bay, completed with ordinances and instruments to promote, incentivize, and guide future investments in the area. This instrument should be very transparent and publicly visible (e.g., through a website), in order to clearly communicate the potential for the prosperous development of the city centre. Among other specific actions there are: • Actively identify and promote specific opportunities for collaboration with the private sector on a housing program. • Expand the Urban Renewal Act to provide fiscal incentives for private developers to build housing in the downtown area, either in partnership with the National Housing Trust as public-private partners-

hips (PPPs) or purely private undertakings, by designating the area bound by the St. James Development Order as a Special Development Area. • Launch a program to promote downtown Montego Bay as a “place to live,” tying into the Vision 2030 Jamaica motto, “Jamaica, the place of choice to live, work, raise families and do business”. • Identify and include in the plan an inventory of all buildings and sites of historic, scenic, architectural, or cultural importance that should be preserved and/or rehabilitated as landmarks.

I

CREATION OF A NEW WATERFRONT FOR MONTEGO BAY

The Historical and Current Urban Footprint and Future Urban Scenarios study revealed that there are only 2.7 m2 of open space per inhabitant in Montego Bay. The World Health Organization recommends 10-15 m2 of open space per inhabitant. The long-term target for the urban development plan is to constantly increase this ratio to meet the minimum requirements within ten years.

17

Downtown Montego Bay has much underutilized or vacant land that is not suitable for any type of construction due to its exposure to natural hazards. This includes the waterfront, which is disconnected from the city, and the heavily polluted and vacant former railway site, situated next to the Transportation Center. Both the waterfront and the former railway site are very unhygienic and urgently need to be cleaned up. The current condition creates a negative image for the city. In order to increase public space for recreational use and also to mitigate disaster risk, these areas should be converted into

public parks. This will significantly improve the image of the city and the identity and self-esteem of its inhabitants. Currently, the coast in front of downtown Montego Bay is underutilized and could be much better integrated with the city. Both locals and tourists could enjoy the potential of recreational facilities and beaches. Areas like the Dump-up Beach and the landfill at the restaurant “Pier 1” are commonly used as garbage dumps, temporary car parks or bus stations. One of the main problems and obstacles for development is that there is no continuous beach due

to fences and the absence of walkways. However, the city built the “Hospital Park”, an approximately 250 m-long park, which is very well-received by the local population. This park serves as a viable reference for the possible development of a stretch of approximately 2 km, starting at the “Margaritaville” restaurant through to the “Fisherman Village,” into a waterfront park including public beaches. To connect the city with the sea while at the same time helping protect it from coastal hazards, the UDC will develop the area along the approximately two kilometre stretch of coast from the Old Hospital Park to the River Bay Fishing Village into a boardwalk park including public beaches and seaside recreational facilities, such as cafes, stand beach volleyball, etc. This project will include activities for: (i) beach enhancement to improve the amenity value of beaches; (ii) shoreline stabilization and erosion control works to protect against storm surge and coastal erosion; and (iii) coastal access works to provide contiguous safe public access along the shoreline. The waterfront park, which is susceptible to storm surge, will act as a buffer zone between the sea and the constructed city. In addition to increasing the quality of life for residents by providing them with a pleasant place for recreation and

southern Area

Plaza

northern Area

northern Area

Plaza

southern Area

12,5 ha

6,18 ha

3,91 ha

7,18 ha

2,80 ha

3,81 ha

0,62 ha

0,22 ha

0,35 ha

total area

green spaces sports areas

total area

green spaces sports areas

total area

green spaces sports areas

4,62 ha beaches

2,35 km

pathway

19

CONCEPTUAL DESIGN FOR THE WATERFRONT PARK

>>

beach access, it will act as a pull factor to incentivize denser development around downtown Montego Bay, away from the periphery. It will also provide an alternative local place for tourists to visit, drawing them into Montego Bay, where they can patronize small businesses. As part of the development of this continuous waterfront park project, the UDC will: • Establish groynes (breakwater structures), where necessary, in order to interrupt water flow and limit beach erosion. These groynes help to create and protect public sand beaches and recreational areas for both locals and visitors. • Erect facilities at the waterfront park including public showers, small restaurants, garbage bins and collection, lifeguard stand, attractive surface, cultural focus point (acoustic shell), benches, public toilets, bike stands, playgrounds, volleyball fields and seating area along a low wall. • Enable access to the park and beaches from downtown with numerous, visible entrance/exit points • Establish a neighbourhood watching unit or tourism police, especially for the park.

VISION FOR AN ACCESSIBLE BEACH

20

FINAL REPORT MONTEGO BAY 路 JAMAICA

BEACHFRONT USED AS CAR PARKING SPACE

>>

DESIGN PRINCIPLES FOR WATERFRONT PARK

st

corridor

sam sharpe square

barnett

market st corridor

north

gully eco

-corridor

Downtown

central plaza

ECO CORRIDORS In the central area of the urban intervention a system of three ecologic corridors connects the historical downtown area with the newly created multifunctional plaza at the Waterfront Park. The three corridors are designed as green boulevards connecting the existing structures from Barnett Street, the Market Street and the a newly created Eco corridor utilizing the North Gully as an accessible walkable strip.

safe transit node

safe transit node

30

safe transit hwy node cooke howard

taxi

safe transit node

bike rental

central plaza locals visitors bikers

NEW PEDESTRIAN AREAS

A NEW MOBILITY BEHAVIOUR

The new Waterfront Park is integrated into a holistic program of making the city more pedestrian friendly. The Downtown area in the mid term is a pedestrian area and connects with the central plaza of the new Park. Safe Transit Nodes are special transition areas for pedestrians at the Howard Cooke Highway. These nodes need a special design with speed bumps or other speed reducing measures. The Highway shall be 30 km/h at the main Downtown area.

The area is pedestrian friendly for all people. The locals can walk from Downtown Montego Bay to the new Plaza facilities, the bars, the beach Volleyball courts, etc. The tourists have different origin-destination patterns: they might come from the Hip-Strip or stop their cabs at the Taxi stands at the transportation center. Close to Pier 1, a bike-rental will be installed and visitors can take a bike-ride from the central plaza and explore Downtown and its new Waterfront park.

21

22

FINAL REPORT MONTEGO BAY · JAMAICA

PHOTO OF THE ACTUAL SITE OF THE WATERFRONT PARK

>>

WATERFRONT SHOWCASE

BEACH FACILITIES AND BARS The waterfront park design includes a complete transformation of the declined beach area with a lots of beach facilities such as beach volleyball courts and bars. Just a few meters from Montego Bay’s KFC, locals and tourists relax at the new facilities, which are all grouped on the new 2,35 km long boardwalk. The boardwalk serves as a connection between Margarita-Ville, the Old Hospital Park, the new plaza and the Fisherman’s Village.

The central plaza The central plaza invites both Montegonians and visitors to stroll from Sam Sharpe Square in Downtown Montego Bay directly into the new plaza. The plaza is a multifunctional area with a hard surface, perfect for cultural events, concerts and shows. On the two ends of the plaza, bars and restaurant facilities serve the visitors. Pier One is kept on the original location and will be the first incubator project on the site.

Natural Oasis The south part of the waterfront park is a much different destination: a quiet and green oasis in the middle of the city. The area has a walking path, with benches and plenty of shade. The trees and the newly designed water basin create harmony with the sea and make this area much more calm and relaxing, a perfect oasis for relaxation.

FINAL REPORT MONTEGO BAY 路 JAMAICA

24

II

MASTERPLAN FOR INCREMENTAL PILOT HOUSING PROJECT

INTEGRAL NEIGHBORHOOD UPGRADING STRATEGY AND PILOT DOWNTOWN HOUSING PROJECT

The city of Montego Bay is characterized by very extensive and low-density urban sprawl patterns in the west and northwest of the city centre. The leftovers of residential use downtown are mostly informal settlements in the area of Canterbury and at the corridors of Hart Street, Barnett Street, Barnett Lane and Railway Lane. A previous attempt to relocate the inhabitants of Railway Lane was unsuccessful. In that case an area close to the airport was specially designed for the new settlement, about 5 km from the original one. Although the living conditions were better, transportation costs associated with the new location were higher and residents lost the social support they had in their original surroundings. Therefore, most of the people returned to their original settlements. This program aims to increase the resident population in the city centre by changing the existing zoning from commercial to mixed-use in order to provide a legal basis for residential use in the city centre and encourage higher density developments in already developed areas. As a result, we

COMMUNITY

Communicate restrictions affecting the urban design project: economic, constructive, weather, etc.

MUNICIPALITY

Transfer criteria and technical expertise to address the dynamic process of the expansion of the housing.

PRIVATE PARTNERSHIPS Engage families in the decision making process.

HOW TO INCLUDE THE COMMUNITY?

DESIGN Define an architectural project through 3 participatory sessions with the resident families: 1. community workshop for creating ideas, 2. preliminary design exercise, 3. definitive architecture design

TENDER Organize an informative workshop where the actors and residents are informed about public subsidies and grants as well as the financial contribution of each family. Start bidding process for the construction works.

CONSTRUCTION Temporary relocation of residents during construction (e.g., railway area) and establish construction committees for the shared spaces of each building site. Organize 3 participatory activities: 1. visit the building site, 2. workshops for extending the properties, 3. workshops for collective space

HABITAT Support the families with the design of the extension of their homes. Organize technical workshops, social and cultural activities to support the community building process and explain to the families how to obtain a loan to extend their homes.

>>

9173 m2

419

housing units

total public space

FAR 1,0

0,4

floor area ratio

plot occupation

12.267 m

2

built area

$

building costs: basic 10 M extended 16,7 M

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

M

27

block 3

units 36 housing

block 5

48 housing units

block 7

1128m2 semi-private green space 445m2 semi-public green space

units 71 housing

Floor area 1,0 Plot occupation 0,4

2953m2 block area 1050m2 built area

1517m2 semi-private green space 436m2 semi-public green space

Floor area 0,9 Plot occupation 0,4

4511m2 block area 1505m2 built area

2097m2 semi-private green space 1005m2 semi-public green space

Floor area 0,6 Plot occupation 0,2

8173m2 block area 1788m2 built area

2398m2 semi-private green space 824m2 semi-public green space

block 2

2724m2 block area 1168m2 built area

block 4

Floor area 1,2 Plot occupation 0,4

71

units 61 housing

block 6

39

housing units

units 93 housing

market

>>

block 1

AEREAL VIEW OF PILOT INCREMENTAL HOUSING PROJECT

indoor & outdoor market

housing units

Floor area 1,2 Plot occupation 0,4

4897m2 block area 2123m2 built area

1970m2 semi-private green space 756m2 semi-public green space

Floor area 1,2 Plot occupation 0,4

4171m2 block area 1800m2 built area

1503m2 semi-private green space 765m2 semi-public green space

Floor area 1,0 Plot occupation 0,4

7694m2 block area 2833m2 built area

2801m2 semi-private green space 1556m2 semi-public green space

restaurants & bars

new roof installations for shade

green indoor courtyards & green areas oustside

recommend urbanizing the existing slums in downtown Montego Bay. As a first pilot project, the National Housing Trust (NHT) in cooperation with the Urban Development Corporation (UDC) will develop the slum at Barnett and Railway Lane. A comprehensive urban development strategy for the upgrade of existing neighbourhoods should be established. This strategies should comprise the following elements: • Using participatory planning methodologies, identify solutions for low-income families, including the upgrade of informal settlements, in accordance with the land use policies of the city. • Identify unsafe structures to be demolished. • Establish a control system for informal settlements whereby new settlements will not be allowed to emerge and existing structured will be regularized. • Promote mixed-used areas as much as possible. • Identify housing programs which can address the different needs of the city, while

HOUSING BLOCK 2 showcase

URBAN LAYOUT BLOCK 2

INCREMENTAL HOUSING: KEY CONSIDERATIONS

COMMUNITY TERRACES

SEMI-PRIVATE COURTYARDS

SEMI-PUBLIC COURTYARDS

INCREMENTAL HOUSING

housing infrastructure gets established residents can expand their housing units if needed community terraces for social interaction shared semi-private courtyards for residential community semi-public courtyards open for public with recreation facilities etc.

3rd floor

3rd floor

29

MY GROWING HOME: THE EXTENSION PROCESS 3rd floor 2nd floor

2nd floor

BASIC

EXTENDED BASIC

3rd floor

EXTENDED

1st floor BASIC

0

1m

UNIT 28m A 28m

BASIC

BASIC HOUSING UNITS VARY FROM 28M2 UP TO 56M2

2nd floor 1st floor 3m

UNIT B

28 m

2

EXTENDED

0

1m

UNIT C 56m

3rd floor 2nd floor 3m

UNIT D

28 m2

28 m

2

28m

56m

56m

84m

56m

90m

BASIC

56 m

3rd floor

0

1m

2

3rd floor

0

EXTENDED

56 m

2

28m

28m

56m

56 m

2

84 m

2

56m

56m

84m 90m

1st floor 0

3rd floor

3rd floor

2nd floor

1m 28m

28m

28m

2nd floor

EXTENDED

EXTENDED HOUSING UNITS VARY FROM 56M2 UP TO 90M2 1st floor

0

1m

3m

2nd floor

56m 56m

2nd floor 1st floor 0

1m

28m

56m

28m

56m

3rd floor 2nd floor 3m

1m

3m

56m

56m

2nd floor

56 m2

2nd floor 1st floor 3m

28m

3rd floor

EXTENDED

UNIT E

56m

1st floor

3rd floor

56 m2

3rd floor

3m

90 m2

30

FINAL REPORT MONTEGO BAY 路 JAMAICA

DETAIL

3rd FLOOR 2nd FLOOR

>>

upper level of 2nd floor units accessed trough 2nd floor through interior staircase extendable with/without balcony shading through projecting roof

3 extendable housing units basic: 28m2, 2x 56m2 (duplex) extended: 56m2, 84m2 (with balcony), 90m2 access through exterior staircase and balcony

1st FLOOR

EXPLOSION DRAWING OF A TYPICAL INCREMENTAL HOUSING UNIT

2 extendable housing units basic: 28m2 extended: 56m2 shops can be integrated in first floor zone

31

promoting investment in the city, social inclusion and mixed-used development, all in line with the Development Order.

• Design and implement a pilot project for the slum between Barnett Lane and Railway Lane.

In a particular case in the Downtown area we propose the following set of activities as a pilot project in Montego Bay:

• Collect data and infos about families currently living in the planning area and start an inclusionary development process with the community.

• Collect information about the existing situation of the settlement (families living there, condition of homes, etc.) • Clear the situation of property rights and, if needed, purchase the site.

SECTION B: VIEW ON HOUSING TYPOLOGIES AS SEEN FROM THE SEMI-PUBLIC SPACE

• Collectively design a housing project, if possible by using the existing parcel-structure of land. It is estimated that it is possible to build 419 housing units on the existing block structure.

• Organize an inclusionary neighbourhood development and participation process based on cultural activities.

SECTION C: FACADES FROM VIEWPOINT OF BARNETT LANE semi-private courtyard

exterior staircase

private balcony

access/community terrace

SECTIONS

semi-private courtyard

exterior staircase

shop

private balcony

possible shop/housing unit

access/community terrace

semi-public courtyard

exterior staircase

shop

extended housing unit

extendable housing units

FINAL REPORT MONTEGO BAY 路 JAMAICA

exterior staircase

semi-public courtyard

exterior staircase

street art

semi-private courtyard

exterior staircase

private balcony

shop

private balcony

access/community terrace

exterior staircase

32 VISION FOR CREATING INCLUSIONARY URBAN SPACES IN MONTEGO BAY

SECTION A: VIEW ON FACADES FROM VIEWPOINT OF RAILWAY LANE

>>

FINAL REPORT MONTEGO BAY · JAMAICA

34

III

REVITALIZATION OF THE CHARLES GORDON MARKET

Markets are traditionally the economic backbone for people with low incomes in Montego Bay. The main market, the Charles Gordon Market, is a very well-visited market facility and, with its 2.2 hectares, is the largest market in the area. On weekends, especially, the streets around the market get really busy. The Charles Gordon Market is the traditional market of Montego Bay, which is divided into three sectors: the market hall, the open-

OUTLINE CONCEPTUAL DRAWING OF REORGANISATION OF THE CHARLES GORDON MARKET

air market and the wholesale market. The market’s main problem is that the main hall lacks fresh air circulation. For this reason, the selling premises are not fully occupied. Only two thirds of the market hall is used; the rest is vacant or cannot be used because of the degraded structure of the building. The vendors complain about the neglected state of the market, especially the rentable storage boxes. The wholesale is not divided from the rest of the market, which causes some friction between the sellers, wholesalers, and street vendors. Some vendors even live in the boxes to avoid mugging and stealing. This public

>>

market needs revitalization and an upgrade, with better infrastructure for both sellers and customers, including better facilities and necessary amenities such as toilets and washing rooms. Therefore, the SJPC will conduct the following activities to specify the upgrade of the market: • Elaborate an architectural design based on a participatory planning process that includes both the sellers and the market authorities. • Modernization of the main-façade, the roof, hygiene facilities, administration area, waste management and security. • Separation of wholesale and retail vendors at the open-air market • Redesign the entrance areas and create a spacious entrance area with an interesting landscape design. • Establish a marketing concept to create a positive image of the market. • Organize vendors with pushcarts as cooperatives and include them as a positive image in the urban core of Montego Bay. Create central storage for pushcarts in a sector of the Charles Gordon Market, which should be administrated by the Market Authority.

FINAL REPORT MONTEGO BAY · JAMAICA

36

IV

OTHER RECOMMENDED ACTIONS

Downtown Walkability Project Pedestrians in downtown Montego Bay lack open public spaces in which they can move efficiently. One example of this is the connection between the most important poles of the downtown area: the touristy Hip Strip along Gloucester Avenue and Charles Gordon Market (off Fustic Road). The poor quality, impermeable surfaces of this pathway create “heat islands” due to direct exposure to sun. Pedestrian crossings are missing along the Howard Cooke Highway and at St. James Street in the inner core of downtown Montego Bay. The high volume of vehicles, pedestrians, and street vendors with traditional pushcarts in narrow streets lead to long delays, particularly during rush hour. The pedestrian facilities and pathways are inefficient for the number of people using the downtown area. In particular, Sam Sharpe Square, the main square of Montego Bay, is a vehicle-dominated public space with low quality for its users. Increasing pedestrian connectivity in the area could significantly decrease motor vehicle traffic volumes and encourage more people to walk in the

city. One of Montego Bay’s main public buildings, it’s Civic Center, which currently functions as a cultural center, is located on Sam Sharpe Square. If Sam Sharpe Square is renovated creating a vehicle-free zone, it will become an important attraction in Montego Bay. The long term vision of this intervention is to create a pedestrian-friendly corridor between the most important spots in the city centre: the Hip Strip, Fort Montego Bay, the public library and KFC, North Gully Bridge, Sam Sharpe Square, Transportation Center, Barnett Street and Railway Lane, and Charles Gordon Market. However, to start with, an integrated urban design plan will be developed and implemented for the area around Sam Sharpe Square with the vision of increasing pedestrian accessibility by creating a shared space for pedestrians and cyclists on homogenized surfaces, with shading and adequate green spaces. The Urban Development Corporation (UDC), together with the National Works Agency (NWA), will implement the project in three phases:

• Develop and implement an integrated urban design plan with the vision of increasing pedestrian accessibility by creating a shared space for pedestrians and cyclists on homogenized surfaces, providing shading and adequate green spaces. • Pilot Project: As a testing phase, temporary pedestrianization of the area bound by Strand Street, Church Street, Orange Street and Union Street by using paint for the public space. • Phase 1: Definitive Pedestrianization of the area bound by Strand Street, Church Street, Orange Street and Union Street. • Phase 2: Pedestrianization of the area bound by Strand Street, Union Street, Orange Street, St. Claver Street, and Creek Street. Other important actions are: • Close Railway Lane for individual car traffic and renovate the road surface. • Initiate a public safety program, including increased police presence and community watch groups.

37

• Install additional eco-friendly street lighting with solar technologies to create a safer environment for pedestrians. • Include communities in a comprehensive planning process.

Rehabilitation of Historic Landmarks The Jamaican National Heritage Trust lists 22 buildings in the St. James Parish, of which 10 are located in downtown Montego Bay. An example of fine Jamaican architecture is Fort Montego Bay, built in 1750 by the British, which still has a battery of 3 of the original 17 George III cannons. Another example is “the Cage,” built in 1806, which was used as a gaol for enslaved Africans, disorderly seamen, and vagrants. “The Dome,” built in 1837 above the underground spring that supplied drinking water for Montego Bay, is an important building for Montego Bay. The Parish Church of St. James, one of Jamaica’s finest churches built of white limestone dated from 1775-1782 and other Georgian buildings, such the redbrick house at 16 Church Street, dating from 1765, and the plantation-style police station, demonstrate the rich history of

Jamaican architecture. All the mentioned monuments have a monument protection; however, their potential as monuments is not being fully exploited. Some buildings are used as office space, tourist shops, or are vacant. The Rehabilitation Project of Historic Landmarks aims to preserve these landmarks and proposes the revitalization of the heritage sites in order to support the local identity and create new sources of income for the people of Montego Bay. Among the main actions are: • Design a rehabilitation project of Historic Landmarks in Montego Bay as a PPP model including the local tourism and hotel sector. • Assess all historical buildings and include buildings from the modernism period. • Design a strategy for the revitalization of the landmarks; propose new uses for these buildings, such as museums or cultural centres. Restore buildings to their original condition and make them enjoyable for the locals and tourists. For example: excavate the Dome and create a little park around it. • Establish a marketing strategy including a heritage walking trail with maps and descriptions accompanying the monuments.

• Include communities and schools in the development process in order to strengthen local identity.

Sustainable Mobility Program An unsustainable and inefficient transport scheme hinders Montegonians from easily reaching jobs, schools, hospitals, recreational activities, beaches, parks, etc. Despite being a small city, Montego Bay already suffers large traffic jams, particularly during the morning, midday and evening peak hours in the downtown area. In a laissez-faire scenario, this situation would be worse in the future given fixed street space and the projected increase in population size and number of vehicles. Hence, addressing mobility in a sustainable manner is imperative. Among critical mobility issues are the lack of both a public bus transport network and adequate pedestrian spaces. The local public transportation system consists of route-taxis only, some of which are run illegally. A formal local bus system does not exist. As of January 2014, the Jamaican Transportation Authority had licensed 2,897 route taxis in Montego Bay, which ply along 81 routes. Most of them have downtown Montego Bay as their desti-

38

FINAL REPORT MONTEGO BAY · JAMAICA

nation, though they can be flagged down when needed and taken to almost any location in the city. Currently, only two major transportation hubs serve the city of Montego Bay. Most of the 2,700 route-taxis complete their routes at the existing Transportation Center (1,348 licensed taxis stop here) and at the Saint Clavers’ Car Park (676 licensed taxis stop here). Many routes, mostly from the northern parts of town, pass through the inner city to get to the existing Transportation Center. Secondary routes have their destination at taxi stands at King Street (248 licenses), Market Street (151 licenses), North Street (138 licenses) and William Street (160 licenses). William Street, close to the North Gully street market, is a very narrow street and most of the congestion is caused by route-taxis turning left from St. James Street. This taxi stand should be moved to a newly designed, North Transportation Center for the northern city taxi-routes. This should be implemented in order to decongest St. James Street in the downtown area. This, however, requires an in-depth traffic study. A properly designed public transportation system and the introduction of bus routes to efficiently serve the communities will meaningfully improve the quality of life of

residents by contributing to public order and reducing the congestion in the city. A properly regulated transportation system with environmental standards with regard to both emissions and fuel use could reduce future air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions from local sources.

Sustainable Mobility Master Plan The establishment and implementation of a Sustainable Mobility Master Plan will be the foundation of better mobility for Montego Bay’s residents. The objective of this plan’s policies, programs, and actions will be to promote the use of sustainable transport modes (walking, biking, and public transportation) that reconcile economic, environmental, and social issues, with the result of improving the quality of life of citizens. The vision of this master plan is to decrease individual car and route-taxi traffic in the city and decongest the downtown area in order to improve the quality of public spaces. Decongesting downtown Montego Bay is a precondition to implementing the Downtown Walkability Project, which is described in the next section. This is why special attention will be given to the downtown area, to set the pillars of an organized and efficient integrated public transport system, and ensure access to mobility for the entire population, especial-

ly the most vulnerable or the disabled. National Works Agency (NWA) will conduct the following activities while developing the Sustainable Mobility Master Plan: • Assess transport supply and demand and their interaction, and pinpoint institutional, financial, regulatory, and land use issues related to mobility in Montego Bay. • Carry out an origin-destination analysis and compute a simple Transport Model for Downtown Montego Bay. • Develop a scheme for the spatial reorganization of the current location of the taxis stands and bus stations. • Organize the licensing of concessionaires through the Transportation Authority. In parallel, seek alternatives in order to reduce taxi licenses on those routes that will be served by buses. • Subsidize or otherwise incentivize the purchase of fuel-efficient and environmentally friendly buses, while creating the appropriate corresponding infrastructure at bus stations.

39

Among the more specific actions we define: • Reorganize/separate route-taxis from other regional buses. The design will significantly increase customer comfort by including shade from the sun, little restaurants and an enjoyable open green space. • Develop a strategy for, design, and implement a new Transportation Center (North) for north routes for buses and taxis located on the North Paradise Street and the public parking lots owned by the St. James Parish Council. • The areas between the Public Library and Post Office and Court House should be designed into a pedestrian and customer-friendly environment with shade, little restaurants and enjoyable open green space.

Upgrade of the Development Order and Training Montego Bay’s current land use plan was designed in 1983 and has not been updated since. There is, however, a draft version of the St. James Development Order, which was developed in 2010. This draft is an otherwise very complete document but

there are no partial plans or drawings that envision sustainable spatial development for Montego Bay. The Development Order should be reviewed and updated, applying innovative rules for intelligent spatial growth and incorporating the findings of the Disaster Risk and Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment and the Historical and Current Urban Footprint and Future Urban Scenarios study. Currently, there are only a few people living in formal homes in the downtown area while urban sprawl is rapidly growing past the city’s fringes. The new Development Order should promote a significant population increase in the city center by changing the existing zoning in the downtown area to mixed-use, which would provide a legal basis for residential use in the city center and encourage higher density development in already developed areas. At present, certain zones have maximum density limits according to zoning by use (commercial, habitation, etc.). These regulations should be changed to higher, minimum density requirements in order to reduce construction of single-family homes and incentivize more dense multifamily buildings. Achieving this will require a more proactive approach to urban planning in the city.

It is urgent that a sustainable urban development strategy or plan be made within 18 months. The strategy should, ideally, involve all relevant national and local stakeholders, including local NGOs and civil society in an inclusionary and participatory planning process that would positively impact governance in the second city. This strategy/plan could be used in conjunction with the Monitoring System to track progress. The St. James Parish Council and the Ministry of Local Government should lead the proposed activities with the support of national and/or international urban planning experts including an ongoing capacity building/training component. General considerations to be incorporated into the Development Order are: • Promote long-term sustainability and a better balance of urban land uses. Design a system of sub-centres with mixed-uses including residential areas, services and public space (increase public space per inhabitant from 6.9 ha/100,000 inhabitants to at least 10 ha/100,000 inhabitants by 2025) along the routes of public transport. • Define a clear settlement boundary around the city identifying forested and agricultural land which can be conserved

40

FINAL REPORT MONTEGO BAY · JAMAICA

and serve as a buffer for new development. Limit or prohibit development on existing agricultural lands in order to protect valuable soils and ecological functions of farmland. • In the Delvelopment Order, identify potential housing projects within the existing that can address the different needs of the city, while promoting investment in the city, social inclusion and mixed-used development. • Identify solutions for low-income families, including the upgrade of informal settlements, in accordance with the land use policies of the city. Especially, develop a strategy for addressing high-risk situations in areas such as Coral Gardens, Fairfield and Catherine Mount. If needed, provide relocation assistance to residents already living on steep, unstable hillsides. • Incorporate disaster risk prevention and management into legal and planning instruments