September 14, 2024 – January 5, 2025

September 14, 2024 – January 5, 2025

David Matteson Associate Curator of Education, Rollins Museum of Art

This booklet presents perspectives from the Puerto Rican diaspora living in Central Florida as an accompaniment to the exhibition Nostalgia for My Island: Puerto Rican Painting from the Museo de Arte de Ponce (1786–1962) (on view September 14, 2024-January 5, 2025). The exhibition’s themes—my home, my people, my island—served as a starting point for understanding how Puerto Ricans established community, navigated cultural misperceptions, and preserved traditions in their adopted home.

The booklet begins with an essay by Dr. Fernando Rivera, founding director of the Puerto Rico Research Hub at the University of Central Florida, who offers a local perspective on the Puerto Rican community in dialogue with the exhibition’s themes. Informed by his research, Dr. Rivera expands the exhibition narrative by connecting it to the current wave of climate migration following the devastation of Hurricane Maria in 2017. His voice is one of contemporaneity and localism, establishing a throughline to our particular time and place.

Following the essay, reproductions of select paintings from the exhibition are presented alongside quotes from Puerto Ricans living in Central Florida. These quotes were transcribed from recorded

interviews in the collection Puerto Ricans in Central Florida: 1940s to 1980s held at the Orange County Regional History Center. This oral history collection was originally produced by the University of Central Florida Digital Ethnography Laboratory under the direction of Patricia Silver and Natalie Underberg in 2008 and 2009. While listening to this rich repository of community voices, our research team selected quotes with correlations to the paintings’ themes and imagery. The works in the exhibition largely predate the period covered within the interviews, yet the sense of nostalgia that permeates these paintings is echoed within the interviewees’ recorded stories. We hope this juxtaposition of quotations and images fosters a poetic polyvocality that encourages your deeper understanding of the Puerto Rican diaspora both past and present.

COVER

Waldemar Morales (Puerto Rican, 1931-2010) Landscape, View of San Germán / Paisaje, vista de San Germán (detail), 1957, oil on canvas, 25 11/16 x 32 in. 59.0118. Museo de Arte de Ponce. The Luis A. Ferré Foundation, Inc.

Fernando Rivera, Ph.D.

Professor of Sociology and Founding Director of the Puerto Rico Research Hub at the University of Central Florida

Like many Puerto Ricans, I am part of the population movement wave to Florida that began in the early 2000s. Although I did not expect to live most of my adult life stateside, it is not entirely surprising, as my grandparents and my mother were among the Puerto Ricans that moved to New York City in the 1940s. They were part of the historical time period deemed the “Great Migration” that saw almost a million Puerto Ricans move to the mainland between 1945 and 1965.1 Now I’m part of the contemporary Puerto Rican Diaspora that Anthropologist Jorge Duany notes has surpassed that earlier great migration. Perhaps my family’s migration2 history paved the way for me to be here to create a space for research and education about Puerto Rico and the Puerto Rican experience.

In 2018, after many previous attempts and with the help of other colleagues and community members, the University of Central Florida established the Puerto Rico Research Hub as a response to the growing Puerto Rican population living in Central Florida and the massive exodus from the island after the devastation caused by Hurricanes Irma and María in 2017. Following the hurricanes, I happened to be in the right position at the right time possessing the tools and support to push for the

creation of the Hub, where I continue to serve as the founding director.

Collaboration has been a hallmark of my academic experience. As such, it is with great pleasure that I write this essay to provide a local perspective on Nostalgia for My Island: Puerto Rican Painting from the Museo de Arte de Ponce (1786–1962) I draw from my personal experiences and my scholarship as a sociologist trained in demographic patterns and qualitative community observations to engage with the exhibition’s themes: my home, my people, and my island.

Historically, waves of Puerto Ricans have been motivated to come to Florida for different reasons. Duany and fellow Anthropologist Patricia Silver have documented the history of Puerto Rican migration to Florida. In her article “Culture Is More Than Bingo and Salsa: Making Puertorriqueñidad in Central Florida,” Silver explores the different population trajectories of Puerto Ricans to the state: from participants in cigar-making industry in Tampa Bay, to soldiers at McCoy Air Force Base (now Orlando International Airport) during World Ward II, to engineers supporting the race to the moon on the

Space Coast, to buyers of land in the Kissimmee area just before the rise of the theme park industry, to the wave of professionals responding to the initial period of Puerto Rico’s financial crisis. 3 In my work, I have also analyzed the climate migration after Hurricane María and the continuous population movement that suggest that Puerto Ricans are no strangers to Florida.

One thing that these waves of movement shared was the redefinition of “home”: what to keep from the past? What to embrace in the new location? How does home evolve through time? As demonstrated by the works included in Nostalgia for My Island, art is one cultural medium through which people preserve a sense of home.

In the wake of disasters, particularly after Hurricane María in 2017, the connections between the home I left behind in Puerto Rico and my new home in Florida were amplified. A major research emphasis of the Puerto Rico Research Hub is on how Central Florida became the center of short and long-term recovery after the hurricane. In a piece published in the Orlando Sentinel, I discussed the severity of the disaster of the island through the perspective of my father back home in Puerto Rico. 4 Furthermore, in our climate migration research we detailed how important the relationships

between the old home and the new home prove to be vital in the response to the population exodus to Central Florida after the hurricane. El vaivén —the constant back and forth between the home I left behind and my new home— continuously shapes and influences my understanding of home.

“Yo soy Boricua, pa’ que tú lo sepas” (“I’m Boricua, so you know it”) can be heard in any gathering of Puerto Ricans in Central Florida. At 1.2 million people, the Puerto Rican population in Florida is the largest of any state. But numbers don’t accurately capture the scope of pride demonstrated among the Puerto Rican diaspora. Puerto Rican pride has driven the development of the institutions and the representation needed to sustain the positive impact of this population to the Central Florida region. An example of the celebration of that pride is one of the Hub’s signature events: the Puerto Rico Baseball Day at UCF. For this event we teamed up with Major League Baseball Playball program, which provides a baseball clinic to children aged 5 to 12. The event was created to recognize the many contributions of Puerto Ricans to baseball, but most importantly to promote Puerto Rican pride and heritage to Central Florida youth. 5 “My people”

encompasses communities of different backgrounds and circumstances that have come to call Central Florida home— those Puerto Ricans that come from New York, the Northeast, and other enclaves; the recent arrivals after Hurricane Maria; those who have been here for decades; and those who continue to split their time between different locations while chasing economic opportunities. Regardless of how they got here, at the end of the day the pride of the people unites them, and they are the engine of the cultural and artistic expressions that are widely displayed across our region. Observations from my disaster research provide insights into the spirit of the Puerto Rican population in the face of the devastation caused by Hurricane María. The following paragraph from a published piece I wrote in Zócalo captures the spirit of “my people”:

The hurricane also revealed the resilient spirit of the Puerto Rican communities, many of which responded quickly during and after the storm. There are countless stories of neighbors checking on the welfare of others, of people finding ways to communicate, and of individuals cooperating to remove debris and get supplies to people when no other services were available. 6

When nostalgically describing “the island,” Puerto Ricans living in Central Florida often focus on environmental characteristics like those captured in the paintings in this exhibition: the palm trees, the green mountain side, the beach, the sun, the sand, the Spanish Forts, the cobblestones of Old San Juan, and the Flamboyán (“Royal Poinciana”) trees. Even on the mainland, “the island” aesthetically manifests in Puerto Rican restaurants, murals, websites, social media profiles, music, and art festivals. Like the island’s culture, the iconic Flamboyán blossoms both on the island and in Florida, symbolically reminding us that Puerto Ricans can thrive in different places and under varying conditions.

Like the physical island, the aesthetic idealization of “the island” was threatened by Hurricane María. The devastating images of a desolated rain forest, brown vegetation, and falling trees were shocking, though they also inspired a greater sense of empathy and a desire to change the conditions on the island for those who remained.

The hurricane heightened Puerto Rico’s financial crisis dating back to the early 2000s that reduced the capacity to

maintain critical energy, health care, transportation, and communication infrastructure. For many, the hurricane was the impetus to exit the island until conditions improved, for others it was a permanent move. In several of our research publications we documented the population change on the island before and after Hurricane María. Estimates showed that around 130,000 people left the island or about five percent of Puerto Rico’s population.7

A significant number came to Florida, particularly Central Florida, as it became the center of recovery and assistance for many Puerto Ricans after the hurricane. Thus, the island became closer than ever to the Central Florida community, further solidifying an imaginary bridge between these seemingly disparate communities. Though spurred by devastating crisis, this bridge will have a lasting influence we have yet to fully realize, blurring geographical borders and uniting Florida and Puerto Rico through our arts, culture, people, and traditions.

Founded in the summer of 2018, the Puerto Rico Research Hub at the University of Central Florida is one of the institution building efforts for the

Central Florida Puerto Rican community. The Hub is the center for the study of Puerto Rico and the Puerto Rican diaspora in the United States. The Hub focuses on the diaspora in Florida and serves both the community and policymakers by working on four main themes: research, student engagement, partnerships, and outreach.

Academic research is conducted to systematically study and produce reports and publications that inform the public, scholars of Puerto Rican studies, and policymakers. Students engage in individual or collective research projects, and exchange knowledge within the academic community and beyond. Partnerships include collaborations with other institutions, research centers, nonprofit organizations, and businesses in Florida and Puerto Rico. The Hub aims to disseminate knowledge about Puerto Rico and the Puerto Rican diaspora through community events, news interviews, and discussions with policymakers. In all, the Hub is an example of how my home, my people, and my island converge to advance the investigation of Puerto Rican issues to the Central Florida community. For more information: https://global.ucf.edu/ puertorico/

@prrh_ucf @ucfprhub

Dr. Fernando I. Rivera is Professor of Sociology and the founding Director of the Puerto Rico Research Hub at the University of Central Florida. He earned his M.A. and Ph.D. in sociology from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and his B.A. degree in sociology from the University of Puerto Rico-Mayagüez.

1 “Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History,” accessed August 6, 2024, https://www.loc.gov/ classroom-materials/immigration/puerto-ricancuban/migrating-to-a-new-land/#.

2 Jorge Duany, Puerto Rico: What Everyone Needs to Know (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2017).

3 Jorge Duany and Patricia Silver, “The ‘Puertoricanization’ of Florida: Historical Background and Current Status,” Centro Journal XXII, no. 1 (2010): 4–31.

4 Fernando Rivera, “Hurricane Maria: When Dad Wanted to Flee, I Understood Puerto Rico’s Peril,” Orlando Sentinel, December 12, 2018, https://www.orlandosentinel.com/2018/09/19/ hurricane-maria-when-dad-wanted-to-flee-iunderstood-puerto-ricos-peril/.

5 Juzanne Martin, “Home Run For Hispanic Youth,” Pegasus, 2023, https://www.ucf.edu/pegasus/ home-run-for-hispanic-youth/.

6 Fernando Rivera, “Hurricane Maria ‘Lifted the Veil’ on Puerto Rico’s Broken System,” Zócalo Public Square, September 18, 2018, https://www. zocalopublicsquare.org/2018/09/18/hurricanemaria-lifted-veil-puerto-ricos-broken-system/ ideas/essay/.

7 Anne N. Junod, Jorge Morales-Burnett, and Fernando Rivera, “Five Lessons from the Aftermath of Hurricane Maria for Communities Preparing for Climate Migration,” Urban Institute (blog), September 19, 2022, https://www.urban.org/ urban-wire/five-lessons aftermath-hurricane-mariacommunities-preparing-climate-migration.

Victor Alvarado was born in New York City in 1948 and moved to Central Florida with his family in 1986. He described his move from the Bronx as a “change from the chaos.” A selfproclaimed “Barrio Boy,” Alvarado held several elected and government leadership positions throughout his career. In his interview, he describes the discrimination he faced from Florida employers, his involvement in political leadership, and the cultural differences between those born on the island and those born on the mainland.

James Auffant was born in New York City, though he moved to Puerto Rico with his mother when he was five. In 1977, when he was twenty-six years old, Auffant moved from San Juan to Orlando with his wife, Lillian. His interview describes his career as an attorney and his involvement in politics and the local business community.

Henry Bursian was born in New York City, though his family moved to Puerto Rico after his father completed his medical residency. In 1983, Bursian moved to the mainland after earning his degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Puerto Rico. After living in Virginia for four years, Bursian

and his family moved to Merritt Island. His interview describes his longtime career as an engineer at NASA’s Kenedy Space Center and the ways his family preserved their Puerto Rican heritage while living away from the island.

Ana Jhanilca Caldero was born in Puerto Rico and lived in Bayamón until 1980, when she moved to Orlando to pursue her degree at the University of Central Florida. Her interview describes her career in academia—she is currently the Dean of Arts and Humanities at Valencia College’s West Campus— and her perception of the differences between her experience moving to Orlando and the experiences of those who move today.

Dora Casanova de Toro moved to Central Florida from Puerto Rico with her husband, Manuel, and their children in 1980. She and Manuel founded the region’s Spanish newspaper La Prensa in 1981. Her interview describes her work to empower the voice of the Hispanic community.

Raquel Lee was born in Puerto Rico but moved to New York City when she was two. The eldest of six girls, Lee describes her family returning to the island every summer to visit their grandparents’ farm, and how the rural farmland contrasted heavily with

the Brooklyn streets on which she grew up. Her interview describes the culture shock she experienced when she moved to Orlando in 1976, the importance of family in Latin American culture, and the pride she feels for her Puerto Rican heritage.

José LeGrand was born in Vieques and moved to Santa Cruz when he was four. While attending Atlantic Union College in Massachusetts, José met his future wife, Dolores. The couple moved to Mexico in 1977 and Deltona in 1983.

In their joint interview, the LeGrands describe the importance of religion and church when forging relationships and adapting to new environments.

Fabian Mercado Jr. moved from the island to New York City in 1953 when he was twelve years old. He and his wife, Elsa, met at a Seventh Day Adventist church in New York in 1963, and they moved their family to Orlando in 1973. In their joint interview, they discuss their faith, raising their children, and Fabian’s desire to return to Puerto Rico.

Yvonne Milligan was born in Arecibo, the “Rum Capital” of Puerto Rico. She moved to Baltimore at age thirteen to attend boarding school and later to Orlando to attend Rollins College in the 1950s. In her interview, Milligan describes the importance of education in Puerto

Rican culture, the segregation she witnessed when arriving in Florida, her life at Rollins College, and the common misperceptions Floridians had of the island.

Luis Moctezuma was born in 1956 in Yabucoa and moved to Guaynabo in 1961. After studying civil engineering at the University of Puerto Rico, Moctezuma moved to Orlando with his family in 1979 to begin working at the Kennedy Space Center. In his interview, Moctezuma discusses what it was like for a Puerto Rican migrant to work at KSC, the adjustment to life in Florida, and the importance of family in Puerto Rican culture.

Eva Pagan-Hill was born in 1947 in New York to Puerto Rican migrants and moved to Tampa when she was three months old. Having experienced segregation throughout her childhood, Pagan-Hill recalls firsthand accounts of moments in which her family and friends were discriminated against for the color of their skin. In her interview, Pagan-Hill discusses segregation, the importance of educating individuals on what it means for someone to be Puerto Rican, and the pride she feels for her culture and heritage.

Roberto Rivera moved to Central Florida with his family from Juana

Díaz, Puerto Rico in 1982 when he was seventeen years old. His interview describes his professional work as a radiologist and raising his family to respect Puerto Rican traditions.

Reina Rubert was born in New York City but moved to Puerto Rico with her family when she was fourteen years old. As an adult in her thirties, she moved from Villa Carolina, Puerto Rico to Central Florida in 1979 with her husband and three children. Her interview describes the cultural differences she perceived between Puerto Rico and Central Florida.

José Santana was born in 1937 in Utuado, a small mountain town in the heart of Puerto Rico. In 1964, Santana became an officer in the United States Air Force and moved to Central Florida. In his interview, Santana reflects on his childhood in Puerto Rico during World War II, when Germans occupied much of the Caribbean. He also details the missions he was assigned during his years of military service, the fellow Puerto Ricans he met on base, and the tragic memories of this experience.

Marilú Rodríguez Salas (Puerto Rican, 1939-1983), Mountains / Montañas, 1959, oil on panel. 12 x 19 3/4 in. 63.0431. Museo de Arte de Ponce. The Luis A. Ferré Foundation, Inc.

“My role has been that: to try to educate people about who we are.”

-Eva Pagan-Hill

“Stereotypes are something I hate.... People sometimes think of all Puerto Ricans as one type of Puerto Rican, they don’t realize that there is a variety, there is a spectrum...of people that came here for different reasons.”

– Ana Jhanilca Caldero

“People have an idea of what Puerto Ricans look like, and they don’t realize that we’re white, we’re dark, we’re blonde, we’re dark-haired, we’re light eyes, we’re dark eyes. We’re a mix.”

– Dora Casanova de Toro

“We had no family here— we were the pioneers. We each brought a suitcase.”

– Reina Rubert

“I remember...landing in the airport [in Orlando]...and we had all these boxes, like fifteen boxes, of things that we moved from our home in Puerto Rico...I was only 17 years old and just going along with whatever my parents [had] decided.”

– Roberto Rivera

“With

time, you get to know people and they end up replacing your family...they fill the void that family leaves.”

– Luis Moctezuma

“Ten to twelve families came here [to Orlando] because we had come in the beginning...they wanted a better life.... On the island there was a lot of political upheaval... the ones who had younger kids came because they wanted to give their children better education.”

– Reina Rubert

“I remember going to banks [in Orlando] and them telling me about [Puerto Rican] currency. They didn’t know that we use the American currency...I would tell them, ‘You go check honey...we use the American dollar as our currency. We don’t have Puerto Rican pesos.’”

– Dora Casanova de Toro

“When I applied to the Florida bar, and I had graduated from Interamerican University of Puerto Rico, they had to write to the American Bar Association to find out that yes, my school was an accredited school, because they had never heard of it.”

– James Auffant

“During Christmastime there is a custom of bringing serenades to your friends, they are called parrandas, and you play guitar and an instrument called a cuatro, maracas, and the güiro...We play instruments, bring fun to the families that you know...[After moving to Central Florida] we missed that— it wasn’t as wild as [it] typically was in Puerto Rico.”

– Roberto Rivera

“Holiday time is food time. It’s eating time. Lots of food. Lots of family. Lots of laughter. And always [telling] stories...We had Santa Claus and Tres Reyes...we always made it a point that Tres Reyes came from the island for [the children].”

– Dora Casanova de Toro

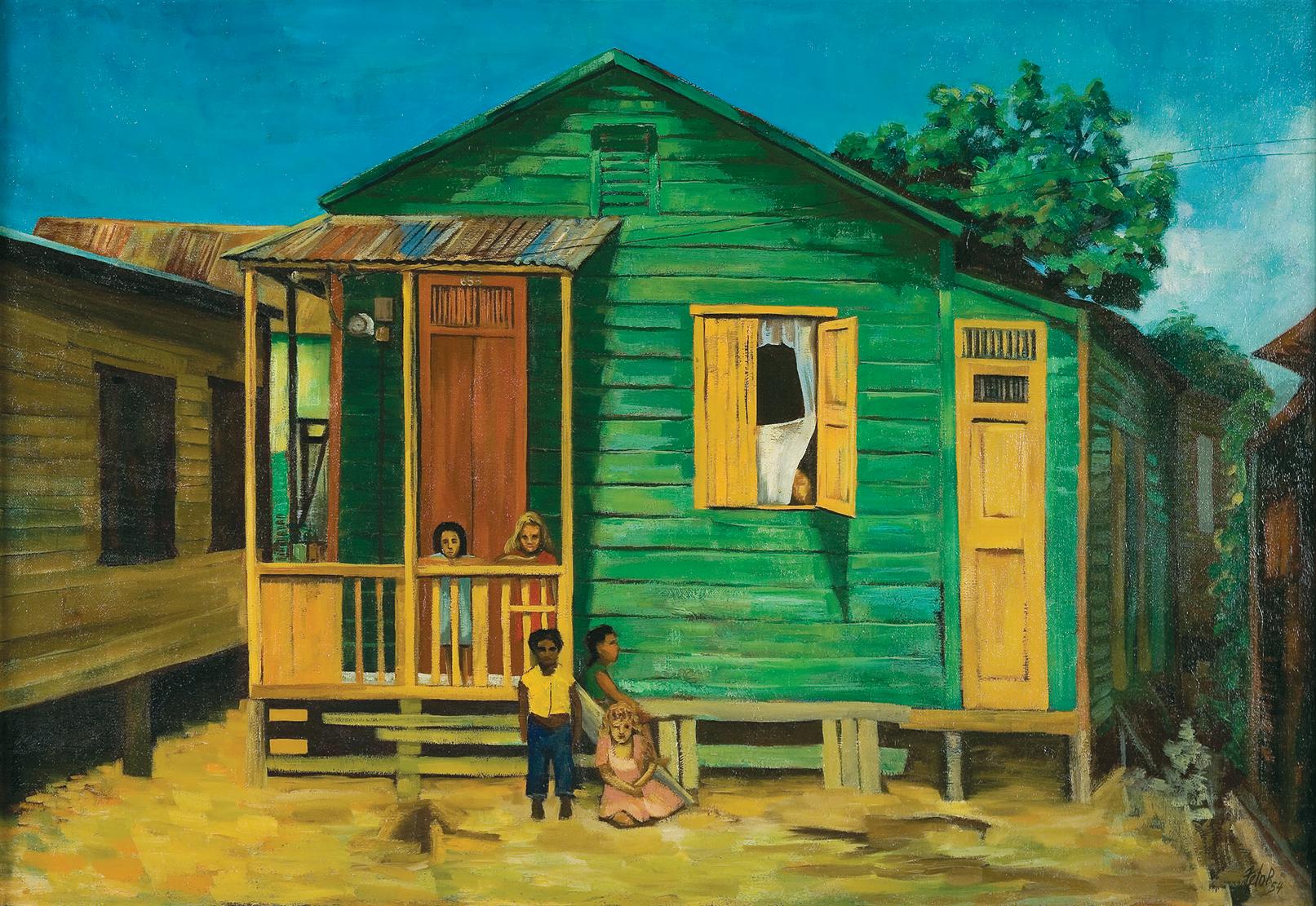

José R. Oliver (Puerto Rican, 1901-1979), Ño Gervasio’s Family / La familia de Ño Gervasio, 1961, oil on masonite, 23 1/2 x 33 1/2 in. 61.0214. Museo de Arte de Ponce. The Luis A. Ferré Foundation, Inc.

“I was sort of like the foreigner. That did not last because it was a very loving family...I tease [my husband] that he’s more Puerto Rican than I am because he’s very family oriented.”

– Raquel Lee

“The relationship between families really goes beyond mom and dad and siblings... When I think of Puerto Rico, the family is the first thing that comes to mind. And if I ever wanted to go back, that would be the main reason.”

– Luis Moctezuma

“I missed the food, and I missed the music...I love the unity of family [in Puerto Rico]...the fact that every family member took care of their elders.”

– Yvonne Milligan

“We make friends and complement each other because we share the same faith. Naturally when we meet someone that is part of our homeland [at church], we have a stronger affinity and that unites us even more.”

– José LeGrand

“Language is a big thing to a culture—religion is also. Catholicism is predominant in the Hispanic community. I used to be a Catholic, but not anymore. I guess I reached the age of reason.”

– Roberto Rivera

Bartolomé Mayol (Puerto Rican, 1910-2007), Landscape in Jayuya / Paisaje de Jayuya, 1960, oil on masonite, 11 3/16 x 9 3/16 in. 63.0316. Museo de Arte de Ponce. The Luis A. Ferré Foundation, Inc.

“Distance doesn’t change the unity of families—you just pick up where you left off.”

– Raquel Lee

“I

am most surprised, still, that a few people here [in Central Florida] from Puerto Rico, even though I feel they have everything they could possibly ask for to feel at home, that they still have this feeling of homesickness.”

– Ana Jhanilca Caldero

“When you go to Puerto Rico, you see the mountains [and they] are so beautiful...everything is nice and green. And then you see the palm trees, all different kind[s] of palm trees. And you see all the different kinds of fruits, and you can just take them from [the trees] and eat them. And they have beautiful houses, right up in the mountains, with balconies all around the house. I just love that. And I love the hammock, where you can just go and lay there and sleep....

That’s all the things I love, and that’s why I would love to go back.”

– Fabian Mercado Jr.

“I remember it being wartime and being in the danger of attack by the Germans whose submarines hung around the Caribbean...[the island was] subject to blackouts...turn everything off. Dark... In those days, if you couldn’t see it, you couldn’t hit it.... I remember my mother hanging blankets on the window so she could turn on a light inside the house without being seen.”

– José Santana

“The

island is the most beautiful place in the world... I’m an amateur photographer. I take pictures everywhere I go. I average about 100,000 pictures a year. I’ve been to Honduras, Nicaragua, taking pictures...There’s no place like Puerto Rico. I have to look for places to take pictures in the United States— in Puerto Rico I take three steps and I find a new location.”

– Victor Alvarado

“I’m

very proud of being Puerto Rican...Puerto Rico means a lot to me, it’s really my home. I look back and what Puerto Rico did to me was make me the person I am today. The culture, the people of Puerto Rico, my family, it’s all about what I am today. That’s where I studied, that’s where I got my knowledge. It means it all to me.”

– Henry Bursian

“To be Puerto Rican, to me, is who I am. I never doubted it, It’s my little island. It’s my poetry. It’s my music. It’s my stories. It’s my family history. It’s the mountains. It’s all I am. It’s all I am.”

– Eva Pagan-Hill

Many thanks to the Museo de Arte de Ponce for loaning the exhibition and endorsing this experimental form of interpretation. We hope the booklet adds a local dimension to this already impactful travelling exhibition.

We are especially grateful to Dr. Rivera for his insights and willingness to cross disciplinary boundaries from the social sciences to the humanities. Many thanks also to Rachel Williams, the Historian at the Orange County Regional History Center, who arranged our access to the collection.

Puerto Ricans in Central Florida: 1940s to 1980s was accessed at the Orange County Regional History Center, June 6-7, 2024. Research was conducted by RMA Associate Curator of Education David Matteson and Education Intern Bronwyn Bayne ‘24. The material sourced from the collection is used with permission by the copyright holder, the University of Central Florida. Original funding for this collecting project was provided by the Florida Humanities Council with additional support from the Orange County Regional History Center, UCF CREATE, UCF Digital Ethnography Lab, UCF Department of Anthropology, and a Research Exchange grant from the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College, CUNY.