A FUTURE WE BEGIN TO FEEL

Women Artists 1921–1971

Foreword

Marie Laurencin and the Avant-Garde

Emma Wippermann

Midcentury Multiplicity

Jenny Anger

Evolution and Sisterhood

William Corwin

Works Biographies

Acknowledgements

As I write to you looking outside my window I think of all the contemporary American poets and artists who represent their outlook on this strange country and I find myself beginning to realize that I shall be one of them. I shall be an American painter, that is to say I shall try to realize the vision of this moment in the most direct way. I shall begin to speak of the New, the new cities that are shooting up along the river, the new settlements in which humanity shall dwell, the new space in which children shall grow up and spread their arms and perform a new dance for a new time, a future that we begin to feel underneath the current of war and strife and uncertainty.

Sonja Sekula, 1947* * Sonja Sekula, journal entry quoted in Nancy Foote, “Who Was Son[j]a Sekula?,” Art in America, October 1971, 76.Our exhibition takes its title from Sekula’s writing. Without need for interpretation or greater elaboration, her words speak volumes today. A Future We Begin to Feel: Women Artists 1921–1971 was an energizing project, the orchestration of which saw us through the limbo of this past spring in New York and the cumulative uncertainty of the last year

Thank you to all the galleries and collectors who, with great generosity, lent their works and encouragement to our show. We especially thank Jenny Anger and Will Corwin for contributing insightful essays to this catalogue.

As artists, galleries, and museums continue to remake aesthetic tradition, Rosenberg & Co. is excited to contribute to a more feminist, nuanced representation of Modernist history

The Second World War effectively shifted the Western cultural nexus from Paris to New York City, as artists and intellectuals fled occupation, persecution, and the wartime economy. While the triumph of the New York School is often portrayed as occurring rapidly in the late 1940s (Gertrude Stein’s theorizing of the avantgarde is useful here: “For a very long time everybody refuses and then almost without a pause everybody accepts”), the transfer of cultural capital happened gradually 1 As established members of the European avant-garde settled in United States, they corroborated and lent credence to the work of emerging artists based in New York; for instance, it was Piet Mondrian who convinced Peggy Guggenheim to exhibit Jackson Pollock’s painting in 1943, and André Breton supported Sonja Sekula in the very beginning stages of her career Those artists who were established enough to bolster the work of others were almost always European men, but many instrumental galleries of the era were founded by American women—such as Rose Fried, Guggenheim, Betty Parsons, Eleanor Ward, and Marian Willard. In broad strokes, A Future We Begin to Feel: Women Artists 1921–1971 traces the shift in predominance from European Modernism to the New York School, focusing on the innovations, connections, and concurrences between women who worked within the differing aesthetic vanguards.

Selecting artists based on their assigned sex at birth—i.e. curating an exhibition of “women artists”—is perhaps contrived, but is also a representation of a varied but extremely identifiable life experience. To be referred to as female has meant something vague and continuous throughout history; under-recognition has been (until very recently) one of the persistent elements of a designated female existence. By removing the over-recognized men of art history, an exhibition can draw clear-sighted attention to artists who lived and

worked with far too little acclaim. In 2021, it is largely accepted as fact that for those artists who are not white, male, and economically mobile, talent and innovation are rarely commensurate with accorded fame. There is a fear, however, that by choosing only “women artists”—and thereby naming these artists as such through the insistence on the modifier of “woman” before the noun “artist”—we would unintentionally reinscribe the false sex and gender binaries that we seek to dismantle.2

Additionally, it is difficult to say whether all of the artists represented in this exhibition would wish to be included in such a show. Esphyr Slobodkina, Sonja Sekula, and Irene Rice-Pereira exhibited in Guggenheim’s 1943 Exhibition by 31 Women, but Georgia O’Keeffe famously declined to participate, writing that she did not want to be known as a “woman artist.”3 Before the feminist art movement, however, an exhibition would include either no women, a tokenized woman, or only women. All of these are fraught formulations, and as issue-ridden as the all-women show was and is, it has historically given crucial exposure to otherwise undervalued artists. It is with this framing that we pay homage to an imperfect form of great impact.

The dates that bookend A Future We Begin to Feel—1921 to 1971—feel providential. This year is the fiftieth anniversary of the 1971 publication of Linda Nochlin’s foundational essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” Published by ARTnews in the midst of second-wave feminism, Nochlin’s essay answered the titular question by puncturing the concept of “greatness” and placed in its stead the historical reality of unequal institutional access. Nochlin irrevocably changed the art historical discourse: critics and scholars today rarely use “great,” or the Romantic ideal of genius, as a comprehensive qualifier for an artist.

The beginning date of this exhibition, 1921, is not only one hundred years from the present, and fifty years before Nochlin’s essay, but is also the year in which Paul Rosenberg began representing the artist Marie Laurencin. Paul Rosenberg & Co., from which this gallery is descended, was the foremost dealer of the School of Paris before the Second World War: Paul Rosenberg represented Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Georges Braque, and Fernand Léger, and after holding a solo exhibition of Marie Laurencin’s work in 1920, began a professional relationship with Laurencin that lasted until her death. When Paul Rosenberg & Co. reopened in New York City in 1941, Laurencin was shown alongside Braque, Léger, and Picasso at the

inaugural exhibition. Her work is among the earliest in A Future We Begin to Feel, and our desire to reconsider her artistic legacy was the spark that prompted the organization of this exhibition.

Marie Laurencin is often overlooked in contemporary efforts to trace the course of Modernism. Unless it is to note her participation in Picasso’s group of Cubists or her inclusion in Guillaume Apollinaire’s The Cubist Painters, Laurencin and her figurative portraits go largely unexamined and unhistoricized. Born in 1883 to a single, workingclass mother, Laurencin initially studied porcelain painting—a classic trade for women. She switched to studying fine art at the Académie Humbert, and as a young artist she met Picasso at the gallery of Clovis Sagot in 1907. According to artistic legend, Picasso saw in Laurencin a potential fiancée for his friend Apollinaire—and indeed, she and Apollinaire soon began a tangled relationship that lasted for several years. During this time, Laurencin’s success as an artist grew; Apollinaire often wrote of her work, Gertrude Stein purportedly gave Laurencin her first sale, and Laurencin’s participation in the coterie of successful Cubists led to critical recognition and inclusion in exhibitions and salons. In 1912, Laurencin was the only woman to be included in La Maison Cubiste at that year’s Salon d’Automne.

Around this time, Laurencin ended her relationship with Apollinaire. The reasons are not clear, but art historian Elizabeth Louise Kahn draws attention to the fact that Laurencin had recently met Nicole Groult, with whom she had a well-documented and long-lasting romance.4 Her relationship with Groult lasted through Laurencin’s brief marriage to the German Baron Otto von Waëtjen, her subsequent exile from France during the First World War, and her divorce before returning to Paris in 1920. Other relationships with women followed, including with Suzanne Moreau—whom Laurencin legally adopted, seemingly so that Moreau could inherit her estate when she died.

Laurencin’s public influence lasted well beyond her relations with famed men and her early career with the Cubists: after she had ended her relationship with Apollinaire, Laurencin was included in the 1913 New York Armory Show; her 1921 representation by Paul Rosenberg garnered her financial success, and by 1925 she earned enough as a painter to buy her own house. By 1930, she was a celebrity, and had been featured in Vu magazine with Anna de Noailles and Colette with

the caption “the three most celebrated women in France.”5 Through commissions, Laurencin was able to financially support herself during the Second World War—a rare situation for a Parisian artist, particularly during the Occupation. In the interwar years, Laurencin’s style matured and crystalised: her figures flattened, and the faces grew homogenous and dreamlike; the darker, saturated colors of her early work faded to dove-gray and pink; and, most interestingly, her subjects became almost exclusively women, often depicted in couples and groups. Sometimes, these women are in varying states of undress; almost always, the feminine subjects are represented as being in intimate relation with one another. Curtains, screens, and swaths of fabric shroud the compositions, as if to signify the privacy and intimacy of such encounters. These paintings were lauded during her lifetime, yet after Laurencin died in 1956, her work was soon forgotten.

I believe that it is the very femininity of her work that has kept Laurencin from contemporary critical attention and categorization, even by feminist and queer scholars.6 In scholarship examining the Parisian “modern woman,” or in accounts of the lesbian coteries of the time, Laurencin is largely unmentioned—even though she frequented Natalie Barney’s salon and was well-acquainted with Gertrude Stein.7 Even in correctives to sexist art history, such as Whitney Chadwick’s heavily-illustrated Women, Art, and Society, the Laurencin work most commonly shown is her 1908 group portrait Les Invités, which depicts Picasso, Fernande Olivier, Apollinaire, and herself—before she developed her mature style and became famous, before her preferred palette turned to pastel, and before her figures became entirely female, feminine, and very arguably queer.8

The term “femme invisibility” is used in queer communities to describe the misrecognition of feminine-presenting but queeridentifying people. This misrecognition happens in both straight, heteronormative spaces and in queer, feminist ones. The writers Apollinaire, André Salmon, and Roger Allard all characterized her as an ideal feminine painter, and during her lifetime, Laurencin benefitted from her femme invisibility: it allowed her financial success and a steady stream of upper class patronage, and enabled a homophobic society to look the other way. In terms of contemporary scholarship, however, this invisibility has often caused her to be excluded.9 Her legacy and work must be reevaluated and rehistoricized as a subversion of the norms of art, gender, and propiety.

Whether associated with Cubism, Surrealism, British Modernism, or Abstract Expressionism, the artists in this exhibition devoted their lives to furthering artistic innovation. Most, but not all, have been excluded from the canon. A Future We Begin to Feel is not intended to insert any new artists into a “canon,” but to question the notion of the canon as such. In 2006, Linda Nochlin wrote a response to her 1971 essay, assessing what had changed in the art world due to the feminist movement:

In the post-Second World War years, greatness was constructed as a sex-linked characteristic in the cultural struggle in which the promotion of ‘intellectuals’ was a Cold War priority… Today, I believe it is safe to say that most members of the art world are far less ready to worry about what is great and what is not, nor do they assert as often the necessary connection of important art with virility or the phallus. No longer is it the case that the boys are the important artists, the girls positioned as appreciative muses or groupies. There has been a change in what counts—from phallic “greatness” to being innovative, making interesting, provocative work, making an impact, and making one’s voice heard. There is less and less emphasis on the masterpiece, more on the piece.10

A Future We Begin to Feel focuses on interesting, impactful pieces— whether they are the small works of Anne Ryan and Marie Laurencin, or the large canvases of Irene Rice-Pereira and Janice Biala. The artists in A Future We Begin to Feel have social and historical connections, and the aesthetic connections are just as strong. The untitled watercolor (c. 1960) from Alma Thomas’s time associated with the Washington Color School revivifies the compositions and palette used by Marie Laurencin. Janice Biala’s Blue Interior (1956) and the Rayonist Composition (c. 1950) of Natalia Goncharova use similar colors, brushstrokes, and organize space with an anchoring vertical line; both artists spent time in Paris in the 1930s, but there is no evidence that they knew of one another. Charlotte Park and Perle Fine, though of different generations in the Abstract Expressionist movement, were in the same periphery of the exclusionary male group that had Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning at its center.

Connections and missed connections pervade the show, and together the artists form just one version of an alternate history of midcentury Modernist art. There are as many art histories as there are artists, and

this exhibition simply constellates art made between interwar Paris and postwar New York, tracing what Sonja Sekula called the “future that we begin to feel underneath the current of war and strife and uncertainty.”

1 Gertrude Stein, “Composition as Explanation,” The Poetry Foundation, February 15, 2010. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69481/ composition-as-explanation. This essay was originally delivered as a lecture in the winter of 1925–26 to the Cambridge Literary Club, and then at Oxford University that summer. Hogarth Press published the essay later that year.

2 I would like to hereafter refer to male artists as “men artists.”

3 Griselda Pollock, “The Missing Future: MoMA and Modern Women,” Modern Women: Women Artists at the Museum of Modern Art (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2010), 43. Pollock wrote, “Only O’Keeffe was in a position strong enough to decline to participate. I do not imagine that feminist O’Keeffe’s refusual to show as a ‘woman artist,’ as cited in the letter she wronte in response to Guggenheim’s offer, was a rejection of solidarity with women. It was more a recognition of the dangers of a move that, however necessary, only consolidated the sex segregation against which the modernist woman was fundamentally struggling. To be an artist and a woman is to integrate the whole of one’s humanity into an open contribution to the world; to be labeled a ‘woman artist’ is to be disqualified by sex from membership to the group known as ‘artists.”

4 Elizabeth Louise Kahn, Marie Laurencin: Une femme inadaptée in Feminist Histories of Art (New York: Routledge, 2003), 13–17, 29–33.

5 Kahn, Marie Laurencin, 12.

6 There are, of course, notable exceptions: in 2020, Galerie Buchholz held a beautiful Marie Laurencin exhibition at their New York location,

organized by Jelena Kristic; Elizabeth Louise Kahn’s 2003 monograph on Laurencin is refreshing in its direct discussion of her sexuality, and is the only comprehensive text on Laurencin in English; several publications about Laurencin came out in the 1980s and early 1990s by writers that include Daniel Marchesseau, Fernand Hazan, and Flora Groult; and Laurencin had a surprising revival in Japan when the collector Masahiro Takano established the Marie Laurencin Museum in Tokyo.

7 Gertrude Stein, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (New York: Vintage Books, 1933), 60–61. Stein writes about Laurencin in a way that seems both knowing and admiring: “Everybody called Gertrude Stein Gertrude, or at most Mademoiselle Gertrude, everybody called Picasso Pablo and Fernande Fernande and everybody called Guillaume Apollinaire Guillaume and Max Jacob Max, but everybody called Marie Laurencin Marie Laurencin”; and “Marie Laurencin, leading her strange life, and making her strange art.”

8 Kahn, Marie Laurencin, 26. Kahn’s analysis of this painting is excellent: “Picasso is relegated to the lower left corner and constricted by the rigidity of his bodily contours and profiled face. Although Apollinaire is seated center stage, Laurencin inverts the gendered convention of the family portrait; she as the standing figure becomes the patriarch, the owner of the group’s status.”

9 It is worth noting the contemporary celebration of masculine-presenting queer artists such as Romaine Brooks and Claude Cahun, which begs the question of whether femininity is still a liability in the arts.

10 Linda Nochlin, “‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’ Thirty Years After,” in Maura Reilly, ed., Women Artists: The Linda Nochlin Reader (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2015), 312.

I had a great respect for her and she for me. She was easy to get along with, although she was highly disturbed. She painted all the time, and her work was highly changeable. It’s too bad she didn’t pin herself down, but that’s the way she was. No matter what she did it was of great interest compared with the other students. She was always one of the best in the class. Her work was much more creative and moving than most; it always had great spirit. — Morris Kantor on Sonja Sekula1

These brief lines by Morris Kantor, Sonja Sekula’s teacher, encapsulate much about the artist’s life and work. Critics admired the latter, which garnered her a solo show at Peggy Guggenheim’s gallery, Art of This Century, in 1946, and five subsequent shows at Betty Parsons’s gallery from 1948 to 1957. She did suffer from mental illness (“she was highly disturbed”), but, as I have argued elsewhere, her illness did not adversely affect her art—and, as we shall see here, it may have contributed to her creativity.2 The problem Kantor identifies is that Sekula did not settle down and produce a representative style. Her inventiveness led her in dozens of different directions—a sign of its richness—but it also left her vulnerable in the face of the art world’s desire for coherent artistic subjects and oeuvres.

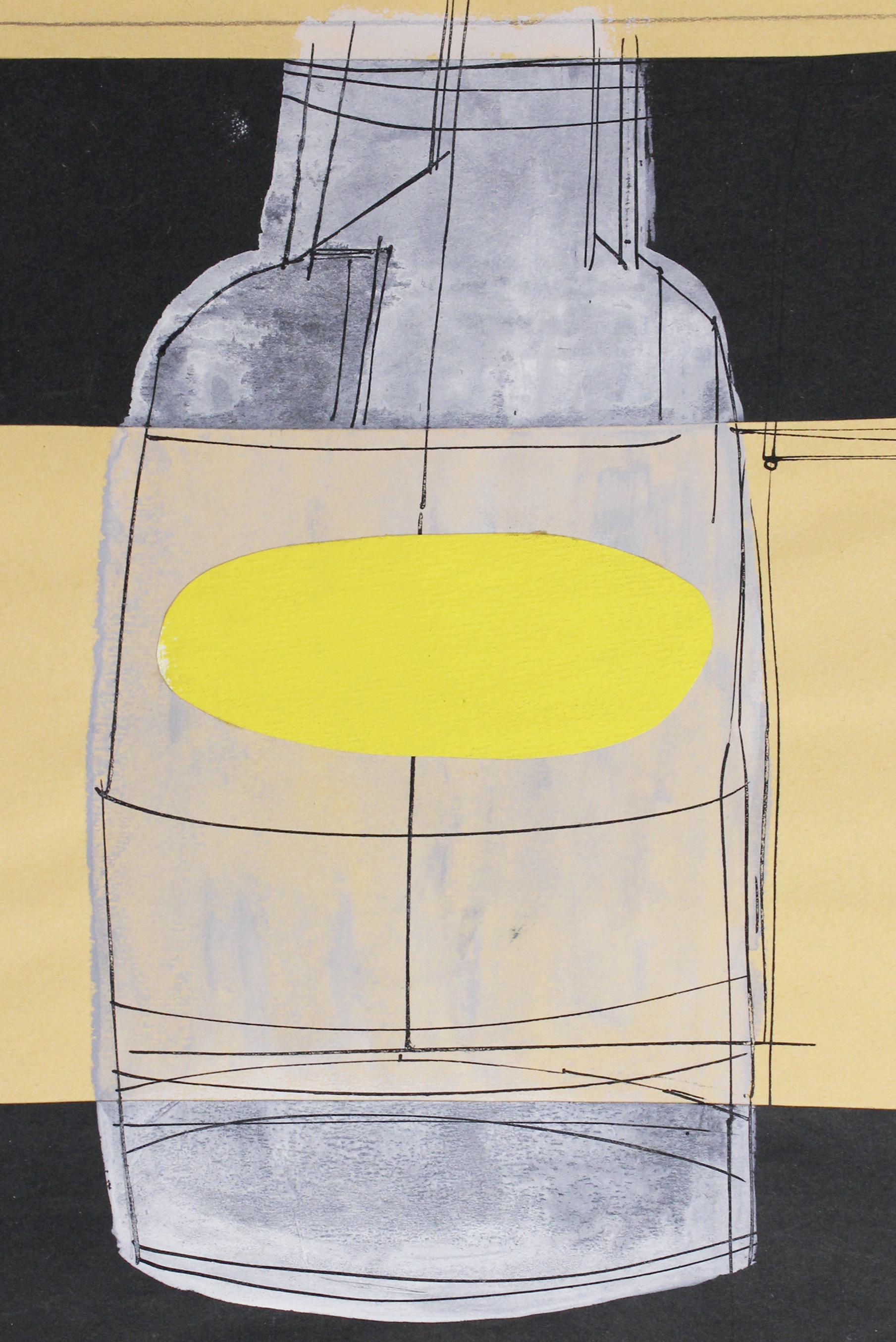

The three Sekulas in this exhibition hint at the range of her work. A Word, a Name, a Gift (1952), a mixed media work on paper, 11 x 6.6 inches, for example, reveals a fine, white calligraphic line as scaffolding for a suggested, nearly translucent architectural structure combined with text. The yellow from the bottom left is a ladder that leaps high into the arches. In contrast, Air (1956)—which is significantly larger at 18.3 x 26.2 inches—presents swirls of thick, opaque paint covering two horizontal registers, the bottom one covered with a pasty white. Finally, Untitled (Bottle) (1958), relatively small at 8 x 5.8 inches, shifts medium to a collage of several layers with gouache and ink on paper. The composition is spare, with the

titular bottle in the center, framed by wide black bands at top and bottom. A luscious, undiluted blob of yellow paint, a cutout, suggests the surface of liquid in the bottle. The three works, masterful in their own way, seem to have sprung from separate sources of creativity.

Critics generally responded favorably to Sekula during her run of solo shows in New York in the later 1940s and 1950s. Nevertheless, there are occasional signs that some critics perceived Sekula’s diverse styles not as a strength but rather as a weakness. Note, for example, Henry McBride, who wrote regarding a show at Parsons’s in 1952, “Miss Sekula, too, is not yet publishing a distinct personality.”3 The writer clearly expected more coherence from Sekula’s work, which he displaced on to her character. Or consider a review by Dore Ashton in 1957, in which she praised Sekula but reported that the show demonstrated one style after another: “The larger oil, a faintly toned painting with characteristic deep recessions, pale figures, and symbols, and a linear counterpoint, dates from 1951. Since then Miss Sekula seems to have simplified her vision, making her structures more emphatic. There are also a few ink and water-color drawings in which a nervous handwriting unfolds now in drawings, now in written fragments, in a kind of poetic puzzle.”4 One senses how much easier it might have been to promote Sekula if she had stuck to one thing.

That sense comes from a very longstanding tradition of authorship as elucidated by Michel Foucault in 1969. He referred to early Christian exegesis, which rejected the inferior, the inconsistent, the stylistically different, and the posthumous in order to authenticate Biblical texts. Later, he explained, the intellectual elite gradually established the “author-function,” whereby inconsistencies did not disqualify a text but rather necessitated management: the author-function “constitutes a principle of unity,” by which scholars attribute any changes to outside influences.5 Thus, a writer or an artist and his oeuvre need not be entirely coherent, but the author-function would work to make them or it so. However, as Griselda Pollock has pointed out, such consolidating forces have not always been available to women and their art. In her words, “Women were not historically significant artists [read: unified subjects] because they did not have the innate nugget of genius (the phallus) which is the natural property of men.”6

As many women could not take advantage of the benefits of the refining author-function, those with an extensive and inconsistent oeuvre were faced with a far more precarious career—however brilliant the artist or work. This was, I believe, the case of Sonja

Sekula. At mid-century, when the canon excluded most women, she was not alone. Take Charlotte Park, represented in this exhibition by two works. The gouache, Untitled (Black and Gray IV) (1950), shows broad black strokes contrasted with a light background, and was made during a period in which she solely worked in a monochromatic palette. Her later untitled oil (ca. 1960), however, holds colorful organic pastel forms nestled together across the page. Eileen Agar, whose oeuvre is famously varied, presents disparate styles in one single painting. Her Untitled (Still Life) (1966) presents a quasiSurrealist dreamscape contained by geometric patterning. Indeed, of a recent retrospective of her work in London, the critic for The Telegraph noted, “Her career was a lengthy ribbon on which various movements tied their knots.”7 Yet she was not to be tied down.

There is an additional element to the cacophony of styles with Sonja Sekula, and that is her mental illness. It is perhaps foolhardy without a medical degree to attribute particular aspects of her work to her schizophrenia, yet researchers on mental illness and creativity suggest ways in which her illness could be connected to her multiplicity of styles. It is important to note, first, that as signs of illness increase, creativity decreases, and this pattern likely held for Sekula as she was in and out of mental hospitals over the years.8 There were times, however, when she was well or reasonably well. During such times, she may have benefitted from her illness: as psychologist Shelley Carson writes, “It seems that both creative individuals and people with schizophrenia have a thinking style that favors making loose and non-obvious associations between objects and concepts rather than more apparent and logical associations.”9 Such loose thinking might translate into inconsistent style and content choices as opposed to a more rigid consistency. Further, latent inhibition—a sign of schizophrenia—could be a source of unfettered creativity. With latent inhibition, one does not “ignore irrelevant input based on previous experience,” resulting in less self-censoring.10 Another psychologist, Mark Papworth, believes that latent inhibition may be responsible for a “divergent cognitive style” as well as unusual “associative combinations.”11 Such openness, researchers say, is consistent with creativity, and it is likely commensurate with a wide range and combination of stylistic choices. In short, Sekula’s schizophrenia may have contributed to the multiplicity in her oeuvre.

I must be clear that I am not equating schizophrenia with multiplicity nor claiming, for example, that Charlotte Park or Eileen Agar was schizophrenic. It is compelling to see, though, that schizophrenia is

not only debilitating but also possibly productive. However, Sekula’s diverse, unexpected works have not always been easily assimilable to the consistent author-function still valued in the art world. If we could deconstruct the longstanding fetishization of the coherent masculine author/artist, then we could read Morris Kantor selectively and celebrate Sonja Sekula’s multiplicity: “She painted all the time, and her work was highly changeable…. No matter what she did it was of great interest compared with the other students. She was always one of the best in the class. Her work was much more creative and moving than most; it always had great spirit.”

328.

6 Griselda Pollock, Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism (London: Routledge, 1988), 2.

7 Cal Revely-Calder, “Eileen Agar was a shameless magpie but her art was masterful for it,” The Telegraph, May 16, 2021. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/ art/reviews/eileen-agar-shameless-magpie-art-masterful/

8 Melanie L. Beaussart, Arielle E. White, Adam Pullaro, and James C. Kaufman, “Reviewing Recent Empirical Findings on Creativity and Mental Illness,” in James C. Kaufmann, ed., Creativity and Mental Illness (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 46.

9 Shelley Carson, “The Shared Vulnerability Model of Creativity and Psychopathology,” in Kaufmann, Creativity and Mental Illness, 259, emphasis original. Carson cites B. Maher, “The Language of Schizophrenia: A Review and Interpretation,” British Journal of Psychiatry 120 (1972): 3-17.

10 Beaussart, White, Pullaro, and Kaufman, “Reviewing Recent Empirical Findings,” 52.

11 Mark Papworth, “Artists’ Vulnerability to Psychopathology: An Integrative Cognitive Perspective,” in Kaufmann, Creativity and Mental Illness, 150-51.

Imagine three daughters: one born around 1600 CE, one born in the neighborhood of 1750, and another close to the turn of the twentieth century. Each woman became a painter, and based on the year of her birth, each would have experienced a distinct route to becoming an artist. Simply put, the first would have trained in a workshop, the second an academy, and the last an art school very similar to what a contemporary artist would experience. All of the women in the exhibition A Future We Begin to Feel were born in the latest phase of the path a woman would have followed in order to pursue her creative impulses. Of course there are non-academic paths to an artistic practice as well, as exemplified by the careers of Alice Rahon and Anne Ryan. While the exhibition focuses on work from the twentieth century, the history of women’s art education is vital to understanding how these artists ended up where they were. The narrative of their education closely follows the major historical and economic events and developments that changed the face of art practices overall, such as the Industrial Revolution and the French Revolution, but this history also hinges on singular acts of kindness and generosity between women—in a word, sisterhood—that took place at critical junctures.

The word “daughter” is used in the first sentence of this essay to emphasize a much wider scope of intentionality than just that of the individual. For most of history, a woman’s choices were her own, and this is true in the arts as much as any other discipline or lifepath. A woman’s family dynamics would have most likely placed her in a position to be exposed to visual art, and her family’s business trajectory or financial fortunes would have determined whether or not she could pursue that path; further, her family’s position in society often determined whether that path in the arts came to an end in a marriage often chosen out of economic or social necessity. The most important decision though, in almost all cases, was whether she was allowed to receive an artistic education, and what form that education took. Familial commitments were somewhat less consequential to the artists in A Future We Begin to Feel, as their births fall in the

range of 1878 (Blanche Lazzell) through 1921 (Judith Rothschild), but they still mattered, In addition to the sheer hostility of the art market towards women, the major obstacle to the success of many artists was a more successful artist husband—though a few of the artists in the exhibition, notably Perle Fine and Natalia Goncharova, managed to outshine their spouses and be known by their names alone.

This last historic phase of women’s art education before the present, which coincides with the emergence of private art schools such as the Académie Julian, the Art Students League, and the Yale School of Art, presented aspiring women artists with a relatively wide selection of coeducational opportunities. The sobering reality is still true, as it was in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, that professional art careers exist only for those whose work is embraced by the market, have independent means, or have a second career allowing them to sustain themselves through lackluster sales. None of the women in this exhibition can be described as poor, and several, such as Hilla Rebay, hailed from the highest echelons of society. The major challenge that faced the women in this exhibition was not lack of access to education, but making use of that education to pursue professional careers. Still, these smaller art schools changed the art landscape massively: what had been a trickle of women artists with either family associations or great means at their disposal, now became a torrent of women liberated at least in their ability to study art. These numbers, once activated by a few key decisions such as the active inclusion of women in the Works Progress Administration in the United States in the 1930s, led more women to focus specifically on professional art careers. Through the concerted unyielding efforts of groups such as the Guerilla Girls and Micol Hebron’s Gallery Tally Project, women have gained increased market acceptance—of which this exhibition is a very good example.

What follows is an all-too-brief look at a few of these private institutions, most prominently the Académie Julian in Paris and the Art Students League in New York, which educated half the women in A Future We Begin to Feel. Other institutions that educated the featured artists, such as the Yale School of Art, Byam Shaw School of Art, and the Slade, were similar in mission and organization. Before embarking on an analysis of artists working in the twentieth century, however, it’s helpful to look at the educational trajectory of an artist born in 1600 and in 1750, as these two periods inform our understanding of how women became practicing artists. The improvements that took place in these periods—sometimes overt,

but often subtle—caused major changes that led to the idea of women’s emancipation in art, and that made this exhibition possible. A woman born in 1600 would have trained in the workshop of an established artist. Usually this would have been a family member, but not all women who became artists were the daughters of artists: Judith Leyster (1609–1660) was simply the talented daughter of a brewer, studied art at an as-yet unknown studio, and was accepted to the Haarlem artists’ guild in 1633. More common seems to be the experience of Maria Merian (1647–1717), an engraver’s daughter who followed in her father’s footsteps and even married one of his students, thus keeping her art career part of a tightly-knit and controlled network of individuals who shared commitments to each other and their craft. These stories belie the fact that art was not a career open to most people, even less so women. More well-known artists of the era such as Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1652) were no exception, and according to Germaine Greer, even if they rarely achieved lasting historical status, many of the daughters of wellknown renaissance masters—such as Marietta Robusti (1560–1590), daughter of Tintoretto, and Antonia Ucello (1456–1491), daughter of Paolo—were trained as artists.1 An artist simply trained one’s children in one’s craft, male or female, it was always good to have an extra pair of hands around the studio.

In this way, the medieval model of art education was the most exclusive: like most things in the Middle Ages, an artist’s education could only be inherited, with the very occasional buy-in or remarkable burst of talent. At that time, the idea of choice was foreign and largely nonexistent for men and especially for women; in addition to one’s career and money matters, women’s personal choices were made for them as well. In societies where the power of the Catholic church and aristocracy were waning, and the bourgeois was gaining ground, such as the Netherlands, we see slightly more personal freedom—but those circumstances were the exception.

The woman born in 1750 would experience a very different notion of art education, one which would continue to expand due to the influence of the Industrial Revolution, the Enlightenment, and finally the French Revolution (and for the next generation, the Revolutions of 1848). The tradition of the academies began in the 1500s in Italy with the foundation of the Compagnia di San Luca in Rome in 1478 as a painters guild, which was expanded into the Academia di San Luca a century later in 1577, and the Accademia delle arti del disegno was founded in Florence in 1563. The French academic system

modeled itself on the Italian school, and in 1648 Charles Le Brun founded the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in order to create a space between the guild-controlled traditional crafts, and the “fine arts” of painting, sculpture, and architecture. The latter were developing both aesthetic and metaphysical philosophies that were constrained by the feudal rules and restrictions of the guilds, which maintained the traditional notion that family and personal connections were primary to the arts, not ability or talent.

Two early members of the French Académie were women: Madeleine Boullogne (1646–1710) and Anne Strésor (1651–1713). Interestingly, they were both daughters of artists who were also academicians, indicating that the old-fashioned guild practice of inheriting one’s trade did not end with the foundation of the Académie.

As the academic system spread throughout Europe, founders were often members of the aristocracy—and because of the relative independence and tremendous wealth afforded to aristocrats, these founders were sometimes women. Powerful women assisting women artists is a recurring theme, as in the case of Queen Marie Antoinette sympathizing with Elizabeth Vigee-LeBrun, or Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna becoming the first patron of the women’s department of the St Petersburg Drawing School upon its founding in 1842. This mode of support continued up through Francis Perkins, the first female cabinet member in the history of the United States (Secretary of Labor), who insured some level of gender parity within the Works Progress Administration. Within these seismic socio-political shifts, which generally benefited both the new bourgeois and the working classes, women saw other women. There is a good likelihood that these seemingly small acts made possible the much larger social advances that followed.

As we move into the modern period of women’s art education, and the rise of art schools both attached to state institutions and private, now is a good time to revisit the artists in A Future We Begin to Feel and take note of their specific educational backgrounds. Janice Biala, Isabel Bishop, Dorothy Dehner, Perle Fine, Blanche Lazzell, Beatrice Mandelman, Irene Rice Pereira, Judith Rothschild, Sonja Sekula, and Yvonne Thomas all studied at the Art Students League in New York City. Many of the artists studied in the private art schools in Paris: Marguerite Louppe and Hilla Rebay attended the Académie Julian, Marie Laurencin the Académie Humbert, and Fahrelnissa Zeid the Académie Ranson. Of the two artists who originated in the United

Kingdom, Eileen Agar attended the Byam Shaw School of Art and then the Slade, and Barbara Hepworth attended the Leeds School of Art followed by the Royal Academy. Natalia Goncharova attended the Moscow Institute of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture and Hilla Rebay first attended the Cologne Kunstgewerbeschule, while Marie Laurencin also studied porcelain painting at Sevres. Other notable institutions were Yale School of Fine Art attended by Isabel Bishop and Charlotte Park; Howard University, attended by Alma Thomas; and the National Academy of Design in New York (from which emerged the Art Students League), which was attended by Janice Biala, Alice Trumbull Mason, and Esphyr Slobodkina. Alice Rahon and Anne Ryan were both writers who embraced visual arts in their thirties and forties, respectively, following non-academic paths of art tutelage.

Probably the most influential as a model for succeeding schools was the Académie Julian, which was founded by Rodolphe Julian in Paris in 1868. The Académie Julian offered preparatory training for the examinations that had to be passed in order to gain entry to the state sponsored académies. The school soon became an art school in its own right (as opposed to merely a prep school), and within five years it accepted women as students, too—first in mixed classes and then in women-only ateliers in order to avoid any accusations of impropriety. The French state académies did not accept women until 1897, and by that time Julian had already made a market for himself as the premier art school for women in the world. His Académie was a study in proto-franchising, eventually branching out to nine locations throughout Paris. His obsession with expanding his customer base and notions of “customer service” made his school fertile ground for both the growth of Modernist painting and for the entry of women into both the French art market, and by extension, the wider world market—in particular the United States. Julian combined openmindedness—eductating women artists to the same exacting and punishing standards as the École des Beaux-Arts,—with a capitalist’s instinct to see the untapped resource of middle and upper-middle class women’s (previously unrealized) artistic aspirations. The class distinction is important to note, as Julian applied a substantial surcharge to his female students’ tuition under the assumption that a male family member or sponsor would cover the costs.2

The foremost practitioners of academic French art were hired at the Académie Julian: William Bouguereau, Jules Joseph LeFebvre, and Gustave Boulanger, among others. These practitioners were well-

connected and advised their pupils beyond the studio; mentoring them and offering professional contacts. This was especially important to those for whom the traditional path to an art practice was blocked and it made it possible for talented women artists to work professionally, gain commissions and exhibit at the mainstream salons. The same conservative life-drawing, sketching from plaster casts, and anatomy classes were found at the Académie Julian as at the state académies, but there was a receptiveness to new ideas that Julian fostered himself (perhaps harboring no little antagonism to the more institutionalized art world). The results were new ways of painting and innovative uses of materials. Almost all of the founding members of the Nabis—Bonnard, Vuillard, and Denis— attended classes at the Académie Julian, and Matisse did as well. The Académie Julian also became a who’s who of well-known women artists: Cecilia Beaux, Louise Bourgeois, May Stevens, and the artists featured in A Future We Begin to Feel

In New York in 1875, a group of about seventy disaffected students and an art professor, Lemuel E. Wilmarth (1835–1918), decided to separate from the National Academy of Design and start a new art school: The Art Students League. Like the National Academy, the League accepted women students—in fact, afternoon classes were reserved for women. The acceptance of women pupils was part of The League’s constitution from the start, but there was also the guarantee that the Board of Control be divided equally: “two-vice presidents (one lady and one gentleman) and four other members (two ladies and two gentlemen).”3 Despite being organized on this seemingly egalitarian model, a woman was not president until Lisa M. Specht was elected in 1968, almost a century after the school’s founding. The first woman art instructor was Mary Lawrence Tonetti, who taught from 1895 to 1899. She had been a student of Augustus Saint-Gaudens at The League, and created the central sculpture of Christopher Columbus for the World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago in 1893. Women formed a substantial portion of the student body, but as instructors they were an infrequent presence: Tonetti was the sole woman to teach in the first quarter century of the League. Of the forty-two artists on the roster in the first ten years of the twentieth century; four were women: Lucia Fairchild Fuller, Alice Beckington, Rhoda Holmes Nicholls, and Hilda Belcher. Among the other institutions attended by the artists included in A Future We Begin to Feel; the Yale School of Art was the first art school attached to a university in the United states and was founded in 1869, the Slade was founded in 1871, the Byam Shaw School was founded in 1910.

All were coeducational from the start, yet the relatively large number of women in institutional student bodies was vastly incommensurate with the lagging representation within professorships, gallerists, and sales.

The third daughter from the initial scenario, born sometime around 1900, would have represented the experience of most of the artists in A Future We Begin to Feel. If she followed a traditional academic path, she might study art at a four year college that offered art as a major, as did Alma Thomas at Howard, who was the university’s first graduate in the fine arts program. A decade later, Thomas earned a Master of Arts degree in education from Columbia Univeristy, and in the fifties took art classes at American University. Blanche Lazzell studied fine art at West Virginia University and then continued her training at the Art Students League. For most, however, the simplest path was to attend the more casual art schools like the Art Students League, Académie Julian, or the Slade, where the only obstacle to an art education was not being able to come up with the tuition. The women of this third generation were far more numerous than any of the preceding generations and they worked as teachers, designers, and stylists in any number of creatively-aligned professions. In this exhibition, Beatrice Mandelman, Irene Rice-Pereira, and Anne Ryan were employed with the WPA. It was the first time in recorded history that working class women in substantial numbers were paid by a democratic government for their work as artists. Other notable artists who benefitted from employment with the WPA were Berenice Abbott, Elizabeth Catlett, and Lee Krasner, and the experience opened their eyes to the notion that they could live and work as artists, especially in the low-rent walk-ups of Greenwich Village in New York. Their example paved the way for succeeding generations of women.

As we honor the fiftieth anniversary of Linda Nochlin’s landmark essay “Why Are There no Great Women Artists?,” we still acknowledge her most basic point: lack of access is responsible for the gendered disparity in art history, not lack of talent. But renewed attention to what occurred before the shift away from the workshop to the classroom, and to what happened after, has led to many important changes that Nochlin also acknowledged. We have begun to unearth the many women who painted in plain sight but whose works were misattributed to their fathers, husbands, or contemporaries. The picture that begins to form is of a constant but restricted tradition of women working in the workshops of the late middle ages, for their

families or on their own, which shifted to a few positions of regard in the académie system of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and finally a complete transformation in the mid-nineteenth century which created perhaps the greatest imbalance of all—equal numbers of male and female art students with almost no representation in the market for the latter. This is where the artists in this exhibition are drawn from, and above all, this is the situation that A Future We Begin to Feel seeks to remedy.

2 Gabriel P. Weisberg and Jane R. Becker, Overcoming All Obstacles: The Women of The Académie Julian (New Brunswick, New Jersey and London: The Dahesh Museum, 1999), 13-41.

3 Marchal Landgren, Years of Art: The Story of the Art Students League of New York (New York: Robert M. McBride & Company, 1940), 23.

Janice Biala

Blue Interior, 1956 Oil on canvas

64 x 45.5 in. / 162.5 x 115.6 cm

Seated Woman, 1924

Oil on canvas

34 x 28 in. / 86.4 x 71 cm

Gouache on board

23 x 20 in. / 58.5 x 50.8 cm

The Village in Brown and Black: Rayonist Composition, c.1950 Oil on board

10.6 x 8.7 in. / 27 x 22.1 cm

9.5 x 13 in. / 24.1 x 33 cm

Blanche Lazzell

June Roses, 1926

Pigment on original woodblock

11.25 x 12 in. / 28.6 x 30.5 cm

Petunias, 1926

Pigment on original woodblock

9.5 x 9.5 in. / 24 x 24 cm

Telephone, Newspaper and Vase, c. 1940

Oil on canvas

60 x 81 in. / 152.4 x 205.7 cm

73 x 93 in. / 185.4 x 236.2 cm

27.5 x 67 in. / 69.9 x 170.2 cm

Oil on canvas

50 x 56 in. / 127 x 142.2 cm

9 x 11.75 in. / 22.8 x 29.8 cm

Opaque paint and ink on paper

18.3 x 26.2 in. / 46.5 x 66.5 cm

Untitled (Bottle), 1958

Collage of several layers with gouache and ink on paper

8 x 5.8 in. / 20.5 x 14.8 cm

Esphyr Slobodkina

Untitled, conceived 1943 and executed 1983

Oil on canvas

46 x 48 in. / 117 x 122 cm

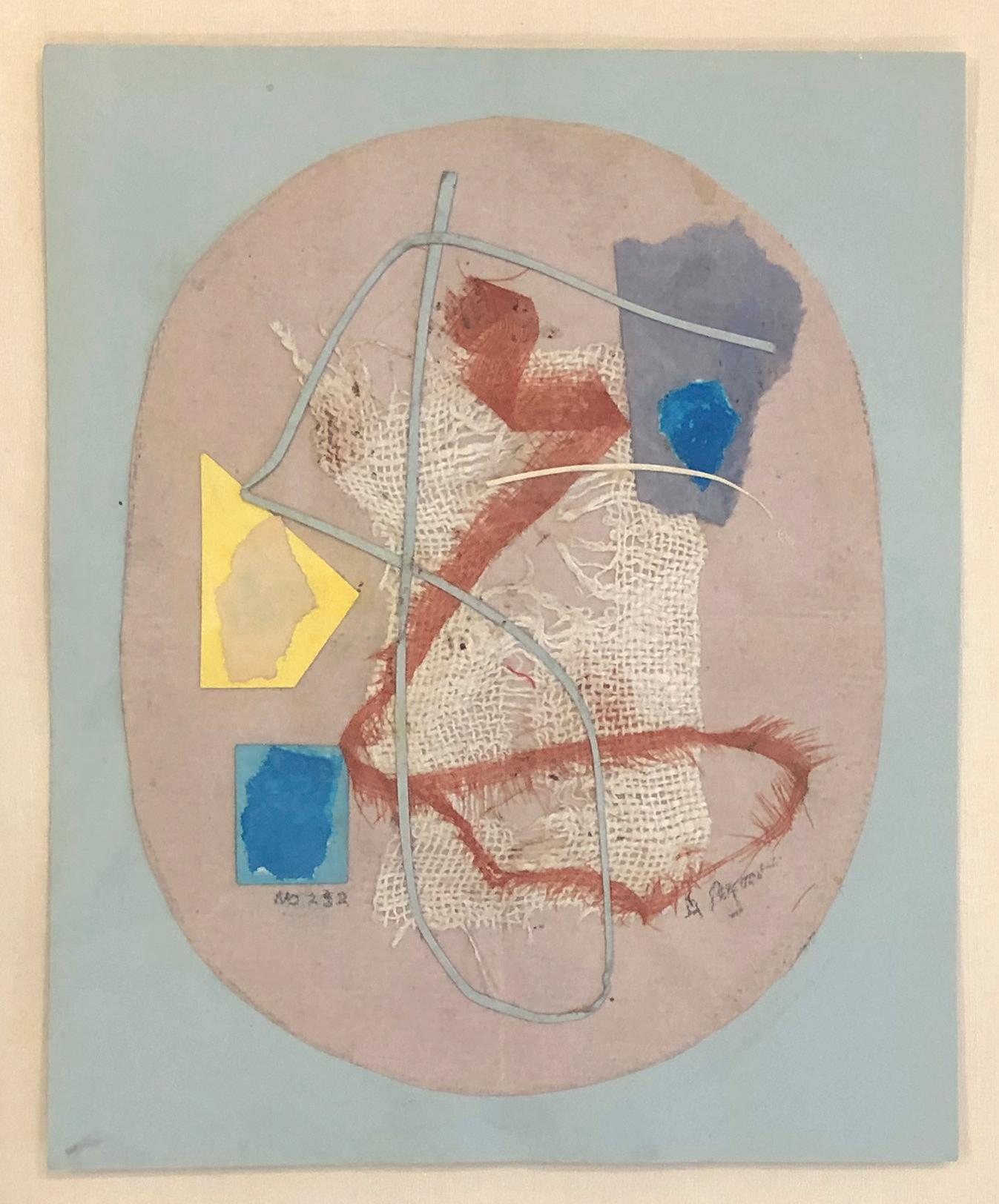

Composition, c.1953

Watercolor and ink on paper

19.7 x 13.8 in. / 50 x 35.1 cm

18.5

Eileen Agar (1889–1991) was a British painter, collagist, and photographer. Born in Buenos Aires to a Scottish father and American mother, Agar experienced an eccentric and rebellious childhood. At the age of six, she was sent to a boarding school in London, where her family joined her in 1911. Agar studied under the prolific artist Leon Underwood and later attended the Slade School of Fine Art. In 1929, Agar moved to Paris where she met the Surrealists André Breton and Paul Éluard and began taking painting lessons with the Czech Cubist František Foltyn. She quickly became a leading British exponent of Surrealism and was the only professional British female artist represented at the 1936 London International Surrealist Exhibition. After World War II, Agar continued to exhibit with the Surrealists in England and abroad, while also experimenting with Surrealist techniques, hat making, photography, and collage. In 1965 she discovered acrylic paint, finding that its versatility and quick-drying nature made it an ideal medium. Agar continued to make art for the remainder of her life, and wrote both a biography on Joseph Bard and an autobiography.

Janice Biala (1903–2000) was a Polish-born American painter who synthesized the styles of early French Modernism and American Abstract Expressionism. In 1913, Biala emigrated with her family from Poland to the United States, settling in New York. She studied with Charles Webster Hawthorne at the National Academy of Design and later under Edwin Dickinson at the artist colony in Provincetown, Massachusetts. In 1930, Biala traveled to Paris and remained there until 1939, when she returned to New York and immersed herself in the American art scene during World War II. She returned to Paris in 1947 with her husband Daniel “Alain” Brustlein, an acclaimed cartoonist, and cultivated friendships amidst the European avant-garde. Her work began to attract the attention of critics and collectors in the 1940s, who celebrated her ability to purposefully incorporate abstraction into any given scene. Biala continued to exhibit her work extensively until her death in 2000.

Isabel Bishop (1902–1988) was an American painter and printmaker. Bishop was born in 1902 in Cincinnati, Ohio. At the age of sixteen, she went to the New York School of Applied Design for Women to study illustration. She later attended the Art Students League, studying painting under Guy Pène du Bois and Robert Henri. In 1926 she moved to Union Square and adopted the various characters that frequented the area as her models. Her candid depictions of the shoppers, commuters, and derelicts became her best known work. Despite the quotidian nature of her subjects, Bishop painted each figure with a sense of monumentality and sensitivity to light reminiscent of Old Master works. In the mid-1930s Bishop began to work as an art teacher at various schools and from 1936 to 1937 was the only full-time female instructor at the Art Students League. She received an American Academy of Arts

and Letters award (1943), an award for Outstanding Achievement in the Arts presented by President Jimmy Carter (1979), and several honorary doctorates. In 1946, she was the first woman to hold an executive position in the National Institute of Arts and Letters when she became vice-president.

Dorothy Dehner (1901–1994) was an American painter, printmaker, and sculptor. Dehner was born in Cleveland, Ohio and as a young woman pursued drawing, modern dance, poetry, and acting. After a trip abroad in 1925, she enrolled at the Art Students League in New York and met the artist David Smith, whom she married in 1927. The couple spent many summers at their upstate home in Bolton Landing, permanently moving there in 1940. During their marriage, Smith was a domineering figure and restricted Dehner’s opportunities for art-making. After her permanent separation from him in 1950, Dehner returned to New York and was free to make work without fear of Smith’s jealousy, control, or violence. Rose Fried Gallery held Dehner’s first solo exhibition in 1952, and in 1953 she participated in group shows at both the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the MoMA. Dehner began printmaking at Atelier 17, where she became lifelong friends with Louise Nevelson. In 1955, Dehner began creating sculpture, modeling abstract forms in wax for bronze casting at the Sculpture Center, and Marian Willard signed on as her dealer. Later in Dehner’s career, she began making sculptures in wood, and eventually worked with fabricators to create steel sculptures of monumental proportions. Throughout the decades, she utilized a personal iconography of arcs, lines, stars, and wedges. Dehner worked prolifically until her death at the age of 92 and today her work is held by many public collections.

Perle Fine (1905–1988) was an American painter and major figure of Abstract Expressionism. Fine was born in Boston 1905 to parents who had recently emigrated from Russia. She moved to New York to study art and attended the Art Students League under Kimon Nicolaides and in 1933 enrolled in Hans Hofmann’s new school. During her studies, she met her future spouse Maurice Berezov and befriended fellow classmates Louise Nevelson and Lee Krasner. Fine began to exhibit extensively during the 1940s, joining the American Abstract Artists in 1945 and exhibiting regularly with Abstract Expressionists such as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning. She became known for her expressive abstract works that were inspired by music, dance, and the natural world. In the late 1950s, Fine began to incorporate collage in her paintings, interweaving scraps of paper, newspaper cutouts, and gold foil into her compositions. Growing tired of city life, Fine moved to East Hampton in the mid-1950s, and from 1962 until 1973 served as an Associate Professor of Art at Hofstra University in Long Island. Following her death in 1988, she was featured in solo exhibitions at the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center in 2005 and again at Hofstra in 2009.

Natalia Goncharova (1881–1962) was a Russian artist known for her Cubist and Futurist paintings. She began her artistic career at the Moscow Institute of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture, where she met her lifelong partner and collaborator Mikhail Larionov. Goncharova established herself early on as one of the leaders of the Russian avant-garde movement. She participated in the 1906 Exposition de L’art Russe at the Salon d’Automne in Paris and in 1911 became a founding member of Der Blaue Reiter along with Gabriele Münter, Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, and Paul Klee. She participated in several significant exhibitions of new art in Moscow, including Donkey’s Tail (1912), and a retrospective in 1913 that showed more than 800 of her works. Goncharova and Larinov also coined several styles of their own, such as NeoPrimitivism and Rayonism. The Rayonist movement in particular synthesized the contemporary movements of Cubism, Futurism, and Orphisim in order to depict a single site from multiple perspectives. Throughout the course of her career, Goncharova also designed sets and costumes for the ballets of Sergei Diaghilev and Igor Stravinsky. Following the Russian Revolution in 1917, Goncharova and Larionov permanently settled in Paris where they remained involved with theatre, costume design, and fashion. She became a French citizen in 1938 and remained there until her death in 1962.

Barbara Hepworth (1903–1975) was an avant-garde artist and sculptor whose work exemplified the style of British Modernism. In 1920, Hepworth won a scholarship to study at the Leeds School of Art, where she began a lifelong friendship with the sculptor Henry Moore. She went on to study sculpture at the Royal College of Art in London, and during a postgraduate trip to Italy she learned to carve from a master-carver in Rome. In 1931, Hepworth began a relationship with English avant-garde painter Ben Nicholson, who introduced her to non-figurative abstraction. At the outbreak of World War II, the couple moved to St. Ives, where she cultivated a practice in drawing. When Hepworth returned to sculpture, her work began to include natural shapes and landscapes inspired by the Cornish coast. Hepworth’s practice was unique in that she relied on the properties of a medium to dictate her sculptural form—a quality that is evident in both her drawings and sculpture. She was also a proponent of direct-carving, the practice of carving directly into wood or stone, as opposed to modeling a sculpture in clay for a master-craftsman to then make the finished work. Hepworth became a major international figure and exhibited her work across the globe during her lifetime.

Marie Laurencin (1883–1956) was a French Modernist painter and printmaker known for her feminine, pastel portraits. While she began her education learning porcelain painting, she transferred to the Académie Hubert in 1904. The same year, Laurencin met the expatriate writer Natalie Barney, and remained a regular at her influential salon. In 1907, Laurencin had her first solo

exhibition at the Salon des Indépendants. At the exhibition’s opening, Pablo Picasso introduced Laurencin to Guillaume Apollinaire, and the two of them began a relationship that lasted until 1912. During these years, Laurencin frequented Picasso’s studio, and she famously painted a portrait of Apollinaire surrounded by Picasso, Fernande Olivier, Picasso’s dog Fricka, and Laurencin herself. Gertrude Stein immediately purchased the painting upon completion, marking Laurencin’s first sale. Laurencin exhibited her work in several major exhibitions, including the 1912 La Maison Cubiste, where she was the only woman artist shown, the 1912 Section d’Or exhibition at the Galerie la Boétie in Paris, and the historic Armory Show in New York in 1913. In 1921, Laurencin signed with Paul Rosenberg, who held solo exhibitions of her work beginning in 1920 and worked with her professionally for the rest of her life. By 1930, she was a celebrity, and had been featured in Vu magazine with Anna de Noailles and Colette with the caption “the three most celebrated women in France. Laurencin stayed in Paris throughout World War II, remaining an important fixture of society until her death in 1956. She left her estate to Suzanne Moreau, her longtime partner.

Blanche Lazzell (1878–1956) was a painter and printmaker, and one of the few female pioneers of Modernist American art. In 1908 she enrolled in classes at the Art Student League of New York. Three years later she traveled to Europe, visiting England, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Italy before finally settling in Paris where she attended classes at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, the Académie Julian, the Académie Delécluse, and the Académie Moderne. After two years Lazzell returned to the United States, and in 1915 she moved to the growing artist colony of Provincetown, Massachusetts. She was a founding member of the Provincetown Printers, who utilized Japanese woodblock techniques to create avant-garde works. Lazzell developed her own unique hybrid of Cubism and Abstract Expressionism with her white-line woodblock prints. In 1923 Lazzell returned for a brief stint in Paris, where she studied Cubism with Albert Gleizes, Fernand Léger, and André Lhote, and exhibited in the Salon d’Automne of that year. Her works are owned by major American public collections, including the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the Art Institute of Chicago; and the Whitney Museum of Art, New York.

Marguerite Louppe (1902–1989) was a French artist who synthesized Purism, Cubism, and Post-Impressionism in her paintings. She was born to a family of prominent engineers in the north of France and spent her childhood in Paris. Louppe attended a variety of art schools, including the Académie Julian, Académie de la Grande Chaumière, Académie Scandinave, and Académie André Lhote. In particular, the Académie Julian fostered a spirit of independence and radicality that became internalized in Louppe’s work. At the

Académie, Louppe met the painter Maurice Brianchon, whom she married in 1934. Louppe acted as a manager to Brianchon’s career, while still cultivating her own artistic practice throughout their marriage. Louppe exhibited her work at the Galerie Charles-August Girar, Galerie Druet, Galerie Louis Carre, and Galerie Rene Drouet. In 1950, Louppe produced a series of gouaches for the novel Le Jardin des Bêtes Sauvages for the Nobel-prize nominated author Georges Duhamel. A major shift occurred in her work in 1960, when the couple purchased a country home in Truffières. In her new studio at the home, Louppe explored her life-long fascination with the resonance of line, geometry, and patterns in everyday forms and in the vernacular architecture and structures of the surrounding hamlet. Louppe continued to paint tablescapes and landscapes and exhibited her work in France throughout the 1980s.

Beatrice Mandelman (1912–1998) was an American abstract painter and collage artist. She was born in New Jersey, the daughter of Jewish immigrants from Austria and Germany. While still a child, she was introduced to art by her parents’ friend Louis Lozowick and began taking classes at the Newark School of Fine and Industrial Art. As a young woman, Mandelman studied at Rutgers University and then later at the Art Students League in New York. During the Great Depression, she worked for the Works Progress Administration, first as a muralist and then as a screenprinter. In 1942 she married the painter Louis Ribak. Two years later they moved to Taos, New Mexico. In their new home, the young couple became the center of a group of artists known as the Taos Moderns, which included Emil Bisttram, Edward Corbett, Agnes Martin, Oli Sihvonen, and Clay Spohn. Mandelman and Ribak opened the Taos Valley Art School, using the income they made from teaching classes to support their art making. In 1948, Mandelman moved to Paris for a year to study under Fernand Léger and during this time she befriended Francis Picabia. Upon returning to Taos, Mandleman and Riback created an exhibition space in their living room, which they called “Gallery Ribak.” The couple organized miniexhibitions there, including a three-person show for themselves and Martin in 1955. Mandelman exhibited her work extensively and her works are included in public collections across the United States.

Alice Trumbull Mason (1904–1971) was an American artist and early advocate of non-objective art. Born in 1904 in Connecticut, she was a descendant of the notable eighteenth century American painter John Trumbull. She studied at the British Academy in Rome, with Charles Hawthorne at the National Academy of Design, and from 1927 to 1931 was a student of Arshile Gorky at the Grand Central School. Through Gorky’s teaching, Mason was introduced to the analytical aspects of Cubism and the spiritual approach of Wassily Kandinsky. In the early 1930s, Mason married and had two children. During this time, she took a brief pause from painting to focus on writing poetry, and she

corresponded with figures such as Gertrude Stein and William Carlos Williams. In 1936, Mason became a founding member of the American Abstract Artists, in which she took an active role for much of her life. Her abstract paintings throughout the 1930s emphasized dense, biomorphic forms with straight edges and angles. In 1944, she joined Atelier 17, Stanley William Hayter’s printmaking workshop, where she continued her exploration into geometric forms. Throughout the 50s and 60s, her work shifted towards Neo-Plasticism, becoming even flatter and harder-edged than that of the previous decades. Mason died in 1971, and in 1973 the Whitney Museum of Art organized a retrospective exhibition of her work.

Charlotte Park (1918–2010) was an American artist and first-generation Abstract Expressionist. Park was born in Concord, Massachusetts, and attended the Yale School of Fine Art from 1935 to 1939. In 1945 she moved with her future-husband James Brooks from Washington, D.C. to New York, where she studied privately with the Cubist painter Wallace Harrison. Brooks and Park soon became part of the circle of Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner and, along with other young artists working in similar styles, established studios on Long Island. Park initially worked in a monochrome palette, which allowed her to prioritize form in her compositions. By the mid-1950s, she reintroduced color into her art, evoking a sense of the lyrical and organic forms of the natural world. Park also began to produce larger canvases with complex compositions that, in fact, emphasized the dynamic relationships between colors. She particularly favored bold hues, strong contrasts, and a personal vocabulary of clustered loops and curvilinear forms. Along with her contemporaries, such as Conrad Marca-Relli and Krasner, Park explored the medium of collage later in the decade. In the 1950s, Park exhibited her work broadly, showing at the Stable Gallery and participating in annuals at the Whitney Museum of American art. Her work has been recognized as a pivotal contribution to the Abstract Expressionist movement, both in New York City and the Hamptons.

Alice Rahon (1904–1987) was a French-Mexican poet and painter of the Surrealist movement. Born in France, during her twenties Rahon moved to Paris where she worked for the Surrealist-influenced designer Elsa Schiaparelli. Rahon became an active member of the Surrealist circle, marrying the painter Wolfgang Paalen in 1934 and publishing her writings with the support of André Breton throughout the late 1930s. Rahon and Paalen traveled extensively throughout Europe and the Americas during their marriage, fostering Rahon’s lifelong interest in prehistoric and indigenous art. In 1939, Rahon met Frida Kahlo in Paris, who invited her to Mexico. With the threat of war on the horizon, she and Paalen departed with Swiss photographer Eva Sulzer—with whom the couple had a polyamorous relationship—to Mexico City where

Rahon would dedicate herself almost exclusively to painting. She became part of a group of European Surrealist artists in exile, including Remedios Varo, Leonora Carrington, and Anaïs Nin. In her paintings, Rahon derived inspiration from her Surrealist contemporaries, the ancient art she had seen in her travels, and the Mexican landscape. Rahon incorporated natural elements into her canvases, such as sand, leaves, and feathers, and also punctuated her works with sgraffito. Over the course of her lifetime, Rahon created roughly 750 works of art and exhibited widely in the United States and Mexico, as well as in Paris and Lebanon.

Hilla Rebay (1890–1967) was an abstract artist, proponent of nonobjective art in the United States, and a co-founder of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum of Art. Rebay was born into a German aristocratic family in Strasbourg, Alsace-Lorraine. She first studied at the Cologne Kunstgewerbeschule and later attended the Académie Julian in Paris, where she studied figurative painting. Rebay returned to Germany in 1910, where she began to develop her interest in modern art under the influence of Jugendstil painter Fritz Erler. In 1912, she participated in her first exhibition at the Cologne Kunstverein and the following year exhibited her work alongside that of Alexander Archipenko, Constantin Brancusi, and Marc Chagall at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris. She met Jean Arp in 1915, who introduced her to the non-objective art of Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Franz Marc, and Rudolf Bauer. Rebay’s work became increasingly abstract, as she aimed to depict expressions of a spiritual nature devoid of ties to the external world in her collages and paintings. Rebay moved to the United States in 1927, and quickly became an established figure in New York City. After painting a portrait of Solomon R. Guggenheim, Rebay became his close friend and art advisor, particularly encouraging him to purchase non-objective art. She eventually served as the first curator and director of his Museum of Non-Objective Painting, later renamed the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Rebay was responsible for commissioning Frank Lloyd Wright to design the iconic building that houses the museum.

Irene Rice-Pereira (1902–1971) was an American abstract artist and proponent of Modernism in the United States. Born Irene Rice in Massachusetts, she began taking art lessons at a young age and later attended the Art Students League. She studied under Richard Lahey and Jan Matulka, who introduced her to the European artistic principles of the Bauhaus, Cubism, and Constructivism that would come to shape her work. While she ultimately married three times, she kept the name of her first husband, Humberto Pereira, and often donned the gender-ambiguous title of I. Rice-Pereira. In 1935, she helped found the industrial arts school the Design Laboratory and began to incorporate the avant-garde theory inspired by the Bauhaus. Her

work was deeply indebted to her focus on industry and machinery, and she later became known for her geometric and rectilinear paintings. Rice-Pereira was also inspired by her travels to Europe and Northern Africa, incorporating the vistas of Morocco and the Sahara desert into her compositional style and aesthetic philosophy. Her work was exhibited at major exhibitions in New York, including a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art and in Peggy Guggenheim’s show Exhibition by 31 Women. Beyond her artwork, Rice-Pereira was also a prolific author, producing ten books of poems and essays throughout her life, and she was a sought-after lecturer of artistic philosophy.

Judith Rothschild (1921–1993) was an American abstract painter and philanthropist. Rothschild graduated from Wellesley College in 1943 and went on to study with Reignald Marsh at the Art Students League, William Stanley Hayter at Atelier 17, Hans Hofmann in New York, and Karl Knaths in Provincetown. In 1945, Rothschild joined the Jane Street Gallery, an artist cooperative that promoted pure abstraction and rejected Social Realism. During this period, Rothschild produced flat, Cubist-inspired abstractions that emphasized unconventional color combinations. She held her first oneperson show at Jane Street, which provided her entrance into the American Abstract Artists group. Rothschild was an active member of the arts community throughout her lifetime, at different points serving as the president of the American Abstract Artists, an editor of Leonardo magazine, a trustee of the American Federation of the Arts, and founding member of the Long Point Gallery in Provincetown. In the 1970s, Rothschild cultivated an artistic practice centered around analogies between colors and music, evoking melodic harmony and dissonance through various color combinations. In her will, she established the Judith Rothschild Foundation with the purpose of using her collection of artworks, by masters like Matisse and Mondrian, to promote underappreciated artists.

Anne Ryan (1887–1954) was an American painter, printmaker, collage artist, and writer. Ryan spent her early years primarily as a writer—she frequented the literary circles of New York’s Greenwich Village, publishing a volume of poetry in 1925 and a novel the following year. After living in Majorca and Paris from 1931 to 1932, Ryan returned to New York and began to paint in the mid-1930s. In 1941, she joined Stanley William Hayter’s Atelier 17, where she made engravings and woodblocks. In 1948, Ryan began to make collage—her primary method of artmaking—after seeing an exhibition of collage by Kurt Schwitters at Rose Fried Gallery. From that point onwards, Anne Ryan made collages until her death in 1954. Similar to Schwitters, Ryan’s early collages incorporated texts and found debris, but she soon started to branch out into a wider variety of objects, such as rag papers, fabrics, and textiles including

handmade paper by Douglass Morse Howell. Ryan joined the Betty Parsons Gallery roster in 1949 with a solo exhibition of her collages and was also included in the 1951 Ninth Street Show. Twenty years after her death, the Brooklyn Museum and the Smithsonian Institute organized a solo exhibition which traveled to the Art Museum of South Texas and the New Jersey State Museum.

Sonja Sekula (1918–1963) was a Swiss-born artist and prominent figure of the art scene in New York City in the 1940s and 50s. She was born in Lucerne, Switzerland, and moved with her family to New York in 1936. Sekula began her studies at Sarah Lawrence College, then, in 1941, attended the Art Students League and studied under George Grosz, Morris Kantor, and Raphael Soyer. In her mid-twenties, Sekula was involved with the emerging group of Abstract Expressionists as well as the New York surrealists, and she developed a decades-long friendship with Alice Rahon, with whom she had a passionate affair in 1945. Sekula had several one-person exhibitions at Betty Parsons gallery between 1948 and 1960 and was included in exhibitions at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century. While Sekula’s works in the 1940s emphasized biomorphic forms and the painterly style of European Modernism, in the 50s and early 60s she developed an unconstrained personal artistic practice. Influenced by her acquaintance with American composers John Cage and Morton Feldman and her time designing costumes for Merce Cunningham, Sekula began to adopt techniques reminiscent of contemporary trends in avant-garde musical composition. Sekula was also a prolific writer and the poetic titles of her works are often written directly on the surface of her paintings and works on paper. Sekula suffered from schizophrenia and returned to Switzerland in the late 1950s to focus on her health. In 1955 she had a solo exhibition at Galerie Palette, Zurich and she continued to work in Switzerland until her death in 1963.

Esphyr Slobodkina (1908–2002) was a Russian-born author, illustrator, and pioneer of early American abstraction. Slobodkina immigrated to New York at the age of twenty and entered the National Academy of Design in 1929. At the Academy, she met Ilya Bolotowsky, whom she married in 1933. She became a founding member of the American Abstract Artists in 1936, which helped pave the way for the acceptance of abstract art in the United States. Slobodkina was a forerunner of hard-edge painting and her work often incorporated juxtaposing planar shapes in harmonious arrangements of color and form. In 1937 she met the noted author Margaret Wise Brown, who encouraged Slobodkina to illustrate children’s stories. Slobodkina published the children’s book Caps for Sale in 1940, which remains a best-selling storybook. In the same year, A.E. Gallatin held Slobodkina’s first major one-person exhibition at his influential Gallery of Living Art. Before her death in 2002, she redesigned

her home as a mini-museum and reading room for children and the foundation continues to preserve the legacy of Slobodkina’s prolific, multifaceted career.

Alma Thomas (1891–1978) was a prominent abstract painter of the twentieth century. Thomas was born in Georgia in 1891, but moved to Washington, D.C. with her family in 1907 to escape growing racial prejudice. She was the first person to graduate from Howard University’s Fine Arts program and later earned an MA in Art Education from Columbia University in 1934. From 1924 to 1960, she worked as an art teacher at the Shaw Junior High School and was a prominent figure of the D.C. art community. After her retirement, she devoted her energy to her own artistic pursuits, and became best known for her focus on abstraction and color theory. Throughout the 1960s her work was associated with the Washington Color Field painters, and she utilized faint pencil lines and broad swatches of color to explore the effects of light and atmosphere. Her later work incorporated colorful brush stroke patterns into simple circular and linear compositions reminiscent of Byzantine mosaics and West African paintings. In 1971, she was the first African American woman to have a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Thomas died in Washington, D.C., in 1978 at the age of eighty-six. Posthumous retrospective exhibitions were held at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American Art in 1981 and at the Fort Wayne Museum of Art in Indiana in 1998.

Yvonne Thomas (1913–2009) was an Abstract Expressionist best known for her lyrical compositions and symbolic use of color. Thomas was born in France, but moved with her family to the United States in 1925. She studied at the Cooper Union, the Art Students League, and the Ozenfant School of Fine Art under the direction of the French Cubist Amadée Ozenfant. In 1948, she joined the experimental Subjects of the Artists School run by Robert Motherwell, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, William Baziotes, David Hare, and Clyfford Still. In the following years, she continued to study with Motherwell and Hans Hoffman. Thomas became associated with the Abstract Expressionists, exhibiting at all five of the Ninth Street Exhibitions, which provided valuable exposure for women working in the movement. She also joined discussions at the exclusive group The Club, frequented by artists, composers, and political thinkers such as Willem de Kooning, Isamu Noguchi, Joseph Campbell, John Cage, and Hannah Arendt. In her work, Thomas conveyed both a lyrical and plastic use of color, cultivating a sense of tension and balance in her compositions. She continued to create art and exhibit her work extensively until the end of her life, keeping color as her primary mode of expression.

Fahrelnissa Zeid (1901–1991) was a Turkish painter and princess, by marriage, of the Hashemite royal family. In 1919, Zeid was one of the first women to

attend the Academy of Fine Art in Istanbul. After her first marriage in 1920, she traveled across the continent and was exposed to European modern art. Inspired, she continued her artistic studies at the Académie Ranson in Paris. Zeid dissolved her first marriage in 1934 and married the Iraqi diplomat Prince Zeid al-Hussein. Over the next six years, Zeid lived and traveled between Berlin, Paris, Budapest, and Istanbul, and visited museums extensively. She returned to Istanbul in 1941 and briefly joined the avant-garde group D Grubu. She held her first solo exhibition in her own apartment in 1944 to much acclaim. In 1946, Prince Zeid was appointed Iraqi ambassador to the UK and Zeid established studios in both London and Paris. In Paris, she gained the support of the gallerist Dina Vierny, who exhibited the artist’s work in 1953. In 1954, Zeid became the first woman to have a solo exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London. After the 1958 coup in Iraq, Zeid lived in exile until joining her son in Amman, where she established an art school. Zeid’s work is characterized by its often monumental scale and kaleidoscope patterns. Blending both Eastern and Western influence, her paintings are at once abstract, geometric, and lyrical.

We would like to thank the following galleries and their teams for lending their works and making this exhibition possible: Maggie Williams at Alon Zakaim Fine Art, London; Christine Berry, Martha Campbell, Elisabeth McKee, and Christopher Blyth at Berry Campbell, New York; Melanie Cameron at Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco; Alexandre Lorquin and Pierre Lorquin at Galerie Dina Vierny, Paris; David Blum and Mike Linskie at Peter Blum Gallery, New York; Vincent Vallarino and Masha Stroganova at Vallarino Fine Art, New York; Brian Washburn at Washburn Gallery, New York; Mac Chambers at William Chambers Art, Catskill, NY.

Additionally, we extend our deep thanks to David Hirsch for entrusting Rosenberg & Co. to show the works of Marguerite Louppe.