The Sandwich Issue

SLOW COOKER

ROAST BEEF THE PO-BOY (AND GIRL) NEXT DOOR

SANDWICHES ANY ‘WICH WAY

SLOW COOKER

ROAST BEEF THE PO-BOY (AND GIRL) NEXT DOOR

SANDWICHES ANY ‘WICH WAY

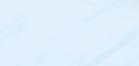

Po-boys are one of the Gulf Coast region’s most recognizable foods. And, as with gumbo and jambalaya, we can’t agree who on makes the best version. There are so many great choices that picking one po-boy is like choosing your favorite child, or your favorite Rouses Market.

We have a story in this issue on how the po-boy got its name. The most popular theory relates to the New Orleans streetcar strike in 1929, when the po-boy (usually roast beef debris on French bread) was first served to striking workers — who were called “poor boys.” The name stuck, and people have been coming up with new po-boys ever since.

How you prefer your po-boy dressed probably depends on where you grew up; this regional sandwich has its own regional varieties. In New Orleans, “dressed” usually means it’s topped with mayonnaise, lettuce, tomatoes and pickles. But for the rest of the Gulf Coast, dressed usually means mayonnaise, mustard, lettuce and tomatoes — and this is what it means to me.

For many people, including me, Olde Tyme Grocery in Lafayette serves the best shrimp po-boy on Earth —

it’s piled high with more than half a pound of large Louisiana shrimp. It comes “fully dressed” with mayonnaise, ketchup, lettuce and tomatoes. (The addition of ketchup is reserved for fried seafood.) I don’t want the ketchup or the tomato — but if a tomato sneaks its way onto my sandwich, I’ll eat it.

My favorite hot roast beef sandwich comes from Darrell’s Famous Poboys in Lake Charles. The roast beef is tender and the bread sopped in gravy (to me, the messier the po-boy, the better). At Darrell’s, dressed means mayonnaise — regular or a homemade jalapeño mayo — plus mustard, lettuce, tomatoes and cheese. I get the homemade jalapeño, and so should you. And try to get there before the noon rush.

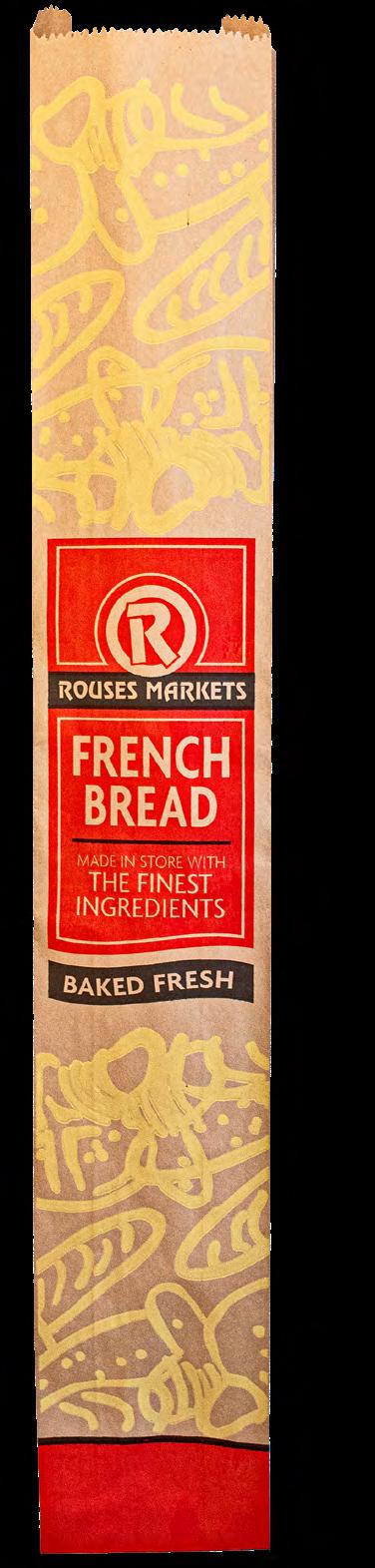

We make our own ham, turkey and roast beef po-boys at most of our Rouses stores. The bread is baked fresh daily, and we use our own fresh produce and deli meats, which we slice in-house. I think these are the best cold po-boys on the Gulf Coast. I recommend the turkey. When I remember, I take off the tomato.

Donny Rouse, CEO, 3rd Generation Photo by Channing Candies

Photo by Channing Candies

Creative Director & Editor

Marcy Nathan

Art Director, Layout & Design

Eliza Schulze

Illustrator

Kacie Galtier

Designer

Mary Ann Florey

Marketing Coordinator

Harley Breaux

Copy Editors

Patti Stallard

Adrienne Crezo

Advertising & Marketing

ron bonacci

Tim Acosta

Amanda Kennedy

Stephanie Hopkins

Nancy Besson

Taryn Clement

Marketing Interns

Peyton finch

Charlotte Ghrist

After two months of sampling po-boys, subs, clubs and maybe 10,000 finger sandwiches (see page 52), I didn’t think I could eat another piece of bread, let alone a whole sandwich. But then I discovered the Japanese fruit sandwich, the Ichigo Sando, at Yakuza House in Metairie. It’s made with fat strawberries and whipped cream mixed with mascarpone and crustless slices of shokupan, which is a milk bread. If our Gentilly cake was a sandwich, this would be it. I highly recommend it.

This issue of Rouses magazine you are holding was inspired by our designer, Mary Ann, who has a sandwich named just for her at Regina’s Kitchen, a local lunch spot in Mobile, Alabama, that her mother owns. There is also a sandwich named for her sister, Cecilia.

This all got me thinking: What kind of sandwich would I be, if I was a sandwich?

I’ll be the first one to admit that I’m a messy person, and I love a good roast beef po-boy — the smooshier and squishier, the better. To be honest, I ate my way through most of the po-boys on our 2023 best dressed list. Now, I am not a food critic, but I know what I like, and what I like is messy. I grew up on Parkway Bakery & Tavern in Mid-City (the messiest roast beef in town); Sammy’s Food Service & Deli in Gentilly; and Domilise’s Uptown, with Miss Dot behind the counter. I love Guy’s Po-Boys on Magazine Street; owner Marvin Matherne is a New Orleans original, like the po-boy itself. He’s a hoot.

But I’m not a po-boy, or a po-girl.

I couldn’t be a club either because, as Groucho Marx said, “I wouldn’t be a member of any club that would have me.” At 5’3” — okay, okay, 5’2” — I’m practically a shrimp, but just practically. And while I’ve been known to give a few fingers in my lifetime (especially while driving), I like to think I’m more substantial than a finger sandwich. Growing up, my sisters and I would fight to be the one who would

mess up the smooth surface of a new jar of peanut butter. “I got first dibs!” was like calling “Shotgun!” at our house. I always used a knife to carve my initials, like the Mark of Marcy.

My dad would make us toasted peanut butter and jelly sandwiches on Sundays, the one day a week my mom slept in. The smell of peanut butter, jelly, butter and toast sends me right back home.

I thought I invented the peanut butter and pickle sandwich, but as it turns out, it was almost as famous as peanut butter and bananas. The New York Times even has a recipe. Here’s mine: Bunny Bread or Evangeline — they are not the same thing, which we explain elsewhere in this issue — Jif Crunchy Peanut Butter, and dill pickle spears, sliced thin. It’s a little bit sweet, a little bit sour, a little bit crunchy, a little bit soft, just like me.

Now if I can just get Regina to put me on her menu…

Photo by Channing Candies

Photo by Channing Candies

We moved Rouses headquarters to Schriever, Louisiana, in September 2021. We were supposed to move in October, but Hurricane Ida had other plans. The corporate cafeteria hadn’t even been built yet, but with three weeks of power outages, and the teams all dealing with the damage to our stores — as well as their own homes — the cafeteria would have to wait.

There aren’t many restaurants on Highway 311, so the Subway at the Rebecca Truck Plaza and Casino sort of became our employee cafeteria. Our Creative Director, Marcy — from New Orleans — nicknamed it “Galatoire’s” after the famous French Quarter restaurant because there was always a line to get in. With so few choices, you’d run into coworkers at Subway no matter what time you went. And after eight months of eating pretty much the same sandwiches three lunches a week, I cannot tell you how excited we were when Subway rolled out new menu items last summer.

There is a gas station at Rebecca’s. And there’s a story in this issue about gas station po-boys that includes a few that have been labeled “best of.” I would add the Shriever Subway’s MexiCali on wheat with extra jalapeños to that “Best of” gas station list — if it were a po-boy, which it is not. A po-boy is on New Orleansstyle French bread or French roll, which is crusty; a submarine or sub comes on a soft roll. Even if you have the same meat, cheese and toppings — say, roast beef, ham and Swiss — it’s not the same sandwich. The bread makes it a po-boy.

The sound of the waves as they crash on the shore…the feeling of sugar-white sands beneath your toes…the refreshing smell of the salty sea breeze…and the spectacular view from your balcony is an experience you can taste for yourself during your stay on the Alabama Gulf Coast. All five of your senses will thank you!

Courtesy Subway®

Courtesy Subway®

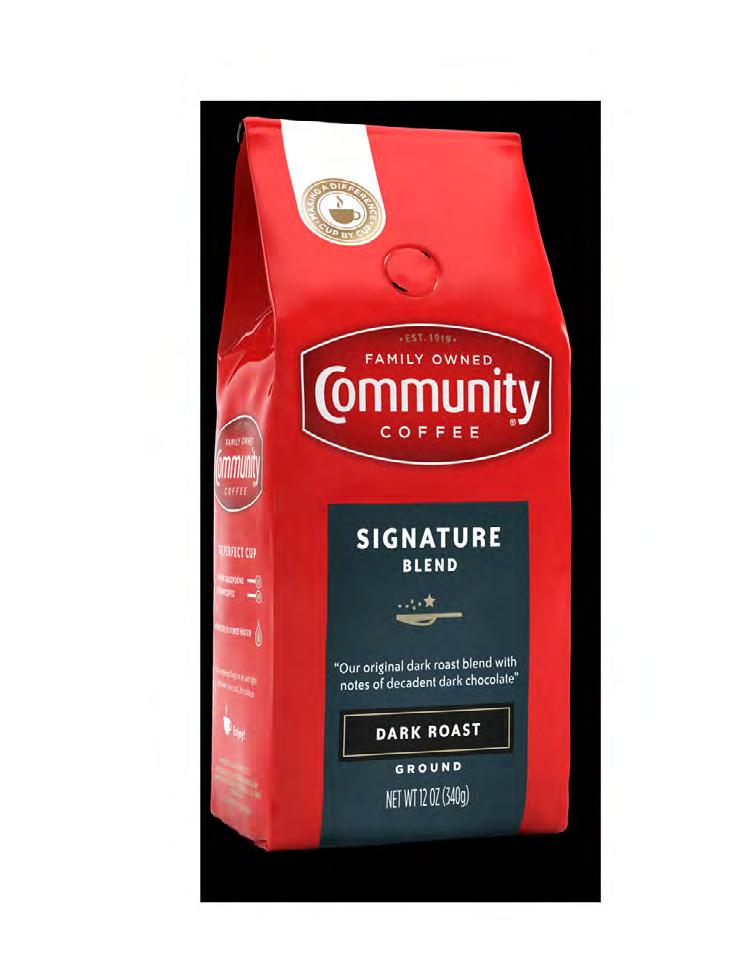

Since 1919, family-run Community Co ee has been rooted in providing the best-tasting co ee to our communities and the people who make them great.

Experience the Co ee with Heart™

Do you ever go on vacation and, afterwards, feel like you should incorporate something from the trip into your daily life? I’ve done this so many times, from olive oil tasting in Tuscany to learning how to make a gin/muddled strawberry drink in a bar in Brooklyn. (I recently discovered while setting up a new phone that I’d lost the “note” in my Notes app from that trip, and I am lowkey devastated. Not that I’ve made one of those concoctions in probably 10 years — but still !) I love to bring a little bit of vacay back home. Most times it’s something really delicious or fun, but mainly it’s just a little touchstone to remind me of the good times.

Picture it: Paris, 2009. Three girlfriends having the time of their lives — baguettes in hands, berets on heads, escargot in mouths. OK, maybe that’s a bit too far.

We did lots of touristy things, but we also made a point to work in lots of genuine Parisian-style activity, like sitting at cafés, peoplewatching, snacking and having a glass of wine on a leisurely late afternoon. There’s nothing quite like it…. I discovered love for a few new (well, new to me !) dishes on this particular trip. Moules-frites was one, which is steamed mussels served with fries — who knew?! And the other standouts were croque monsieurs — a delicious ham sandwich made with gruyere, parmesan and béchamel sauce, then toasted in the oven — and its better half, the croque madame — same, but topped with a sunny-side-up fried egg. My mouth is watering just thinking about that!

After returning stateside, I was home for lunch a few days later, making a sandwich. Boy, did it look pitiful compared to those scrumptious French sandwiches. Inspiration struck and, while I didn’t want to start frying eggs on my lunch hour, I did decide to play around with the plain old turkey-on-wheat I had been eating. Given the constraints on time, attempted constraints on my calorie intake, and minimizing the mess to clean up, I had to get a bit creative. Using Rouses Bread, lightly “buttered” with Brummel & Brown, deli sliced ham and Swiss cheese, I pulled out my panini press (TBH, it was an off-brand George Foreman Grill!) and voilà !

Ali’s ridiculously bad imitation of a croque monsieur was born — and it was my go-to lunch for the better part of a year. So far, my 2023 lunches have been mostly turkey-on-wheat. I need some Paris in my life, tout de suite!

Photo by Channing Candies

Photo by Channing Candies

SARAH BAIRD

Sarah Baird is the author of multiple books, including New Orleans Cocktails and Flask, which was released in summer 2019. A 2019 Knight Visiting Nieman Fellow at Harvard University, her work has been featured in The New York Times, Washington Post, Saveur, Eater, Food & Wine and The Guardian, among others. Previously, she served as restaurant critic for the New Orleans altweekly, Gambit Weekly, where she won Critic of the Year in 2015 for her dining reviews.

David W. Brown is a freelance writer whose work appears in The Atlantic, The New York Times, Scientific American and The New Yorker. His most recent book, The Mission: A True Story, a rollicking adventure about a motley band of explorers on a quest to find oceans on Europa, is in bookstores now. Brown lives in New Orleans.

Susan Langenhennig Granger is editor of Preservation in Print magazine and director of communications and marketing for the Preservation Resource Center in New Orleans. Prior to that she was a news editor, reporter and feature columnist for The TimesPicayune and NOLA.com.

James Karst is an award-winning writer, researcher and editor. He was part of a team at The Times-Picayune that won two Pulitzer Prizes, and he won a Press Club of New Orleans Award for a story he wrote about Louis Armstrong’s childhood. He is currently the Director of Communications and Marketing at the Coalition to Restore Coastal Louisiana.

ARROW-CIRCLE-RIGHT I like a Reuben + Rachel, which has both corned beef and pastrami. They have a similar flavor, but the pastrami is a little spicier. I always add extra Thousand Island dressing, too. If I order at a deli, I get a half sour pickle with it, but when I make it at home with our Dietz & Watson corned beef and pastrami, I serve it with a Wickles Pickle.

– Mike Westbrook, Director of Deli, Cold Cuts & SushiARROW-CIRCLE-RIGHT When it comes to sandwiches, I am a sucker for a good po-boy. Although there are many different takes on this classic sandwich — and normally, I would go for a fried oyster or fried shrimp version — my favorite has to the be Darrell’s Special from Darrell’s in Lake Charles. This po-boy comes with ham, turkey, roast beef, American cheese, Swiss and provolone on a house-made bun with roast beef gravy, jalapeño mayo and all the fixin’s! I always get a large size with plans of eating half later, but by the time I leave, I have eaten the whole sandwich. How can I resist?! Each time I visit Lake Charles, I make it a point to go to Darrell’s. Their delicious food and hometown bar atmosphere keep you coming back for more. It feels like home.

– Brooke Bueto, Deli Merchandiser

ARROW-CIRCLE-RIGHT I live for a traditional bánh mi: soft but crusty French bread (lightly buttered and slathered with aioli), pork, pâté, cilantro, carrots, cucumbers and jalapeños. New Orleans’ West Bank is a haven for all the varieties of bánh mi. While you are grabbing your whole Peking duck at Hong Kong Market, don’t sleep on their bánh mi — it’s top-notch!

– Kim Neal, Deli & Cold Cuts Category Manager

FRENCH FRIED PO-BOY

ARROW-CIRCLE-RIGHT I can’t go two weeks without thinking about a sloppy roast beef debris po-boy with a side of French fries. Then, my mind is completely overcome with the thought of a French fried po-boy from Jeanfreau’s in Chalmette. Yes, you heard correctly: a French fried po-boy. It is a pile of crispy French fries covered with melted cheese and topped with delicious roast beef debris

and gravy. Don’t forget the mayonnaise and the napkins. You’re welcome.

– Mickey Bordelon, Deli Merchandiser

BRIOCHE GRILLED CHEESE

ARROW-CIRCLE-RIGHT My favorite sandwich is a brioche grilled cheese with Dietz & Watson Tavern Ham and Smoked Gouda with just a little bit of Dietz & Watson Horseradish Sauce to give the sweet, smoky taste a little kick. Have to have it with bread & butter pickles.

– Lori Sims, Deli Merchandiser

THE MARY ANN

ARROW-CIRCLE-RIGHT One of my favorite sandwiches is the one my mom named after me! You can read about it on page 58.

– Mary Ann Florey, Designer

MONTE CRISTO

ARROW-CIRCLE-RIGHT The Monte Cristo has always been my favorite sandwich. It’s sweet and savory. It’s basically deep-fried French toast with smoky ham and turkey, melty cheese and sweet preserves. The first one I ever had was at Bennigan’s. We stopped there on our way to see Death Cab for Cutie at the House of Blues. I can still taste it more than a decade later.

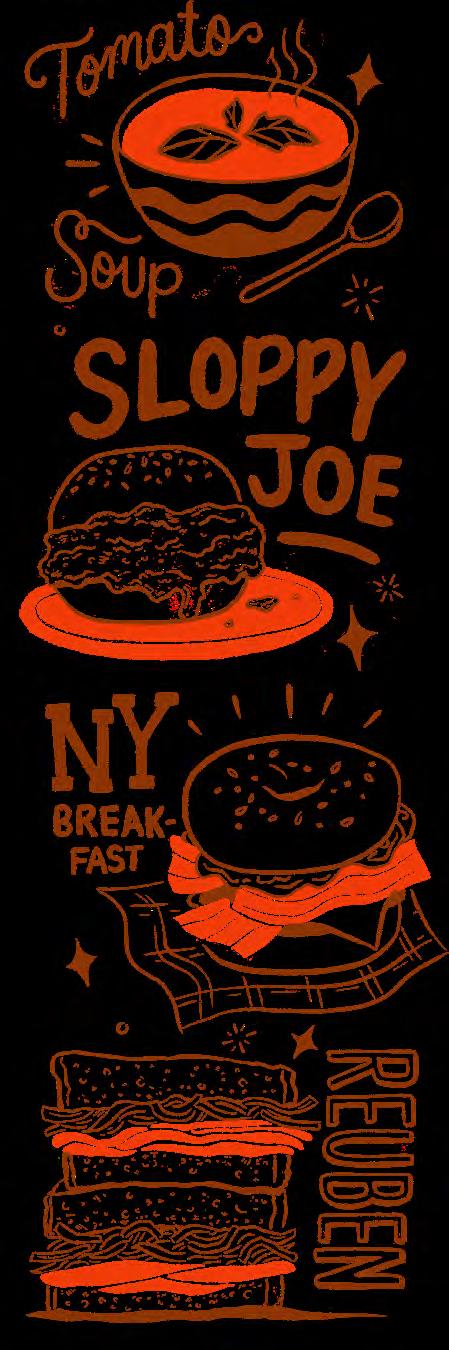

– Kacie Galtier, Illustrator and DesignerARROW-CIRCLE-RIGHT Bánh mi.

– Peyton Finch, Intern

ARROW-CIRCLE-RIGHT Bánh mi, too.

– Charlotte Ghrist, Intern

ARROW-CIRCLE-RIGHT I’m not one for picking favorites; my sandwich choice changes week to week. However, when I picture a sandwich, I immediately think of a BLT: big slices of white bread, crispy bacon, tomatoes, mayo and lettuce. It’s a classic in my mind and always makes me think of my grandmother, who had a beautiful garden right on the Vermillion River. She made the best BLT with her own garden-ripe tomatoes.

– Eliza Schulze, Art DirectorCORE HYDRATION PERFECTLY MATCHES

YOUR BODY’S NATURAL pH*

*approximately 7.4 pH

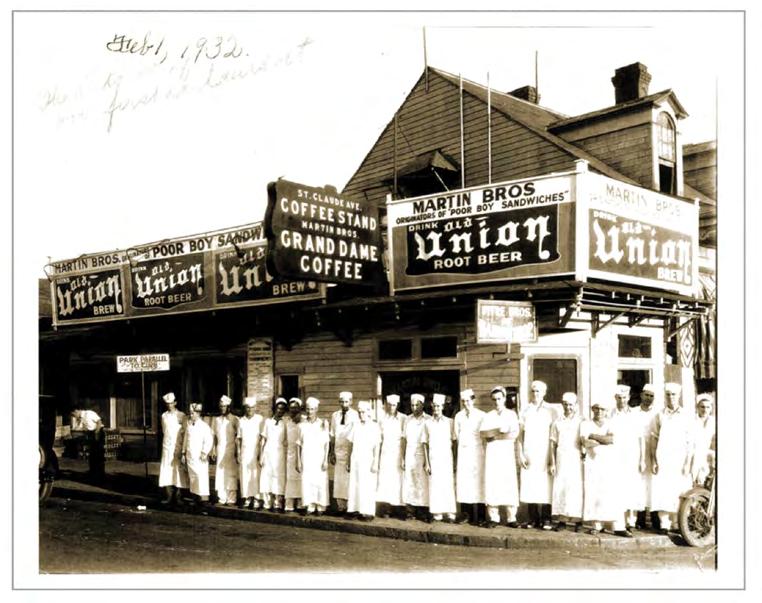

By some accounts, the history of the po-boy is straightforward. Benny and Clovis Martin, who had moved to New Orleans from their hometown of Raceland, came up with the famous sandwich to support striking streetcar workers in the Crescent City in 1929. Legend has it that, when one of the men would come into their restaurant, a cry would ring out: “Here comes another poor boy.” That man would be issued a sandwich on the house, and a culinary legend was born.

That’s the best-known story, anyway — or at least since the late 1960s, when it was first aired publicly, 40 years after the streetcar strike. Prior to that, the Martin brothers gave a different account of how they had created the po-boy, saying it had been named for the blue-collar truck farmers and other laborers who patronized their restaurant at the old French Market.

That’s just one of the complications with this official history. There’s also the fact that we know there were sandwiches very similar to the po-boy long before 1929. We have pictures and descriptions of them. Louis Armstrong, who moved away from New Orleans in 1922, wrote in his autobiography about buying po-boys with his earnings from delivering coal as

a teenager; jazz pioneer Sidney Bechet, who left New Orleans in 1917, gave a similar account in his own autobiography. (A note to language sticklers: The first specific published reference to the sandwich, from a New Orleans newspaper in November 1929, describes a “po-boy,” not a “poor boy,” being served to people in Plaquemines Parish.)

The peacemaker, now considered a po-boy variant, dates back to the 1870s. And then there’s this description from a New Orleans newspaper in 1851 of a to-go sandwich sold by a local saloon: “A big loaf of bread is ‘dug out’ — reserving a crust end as a stop — any quantity of delicious fried or broiled oysters is piled in; the top is neatly put on; and a gentleman can carry home his loaf and his ‘dozen’ — all hot — or have them brought home, for a lunch or a relish to dinner…”

But hey, I’m not here to start an argument. Maybe there was a popular food product known as a po-boy before the Martin brothers began slinging sandwiches in the late 1920s, but it would have lacked the most important ingredient: the po-boy bread created by John Gendusa’s bakery and supplied to the Martins starting in 1929. Without that bread, with a sublime crust and billowy soft inside, a sandwich is just a sandwich.

So, while it may be fair to say the Martin brothers didn’t singlehandedly create the po-boy, they certainly perfected and standardized it, and they made it famous. They recognized the marketing possibilities afforded by the po-boy name, and they made sure it stuck. What is now recognized around the world as a po-boy comes directly from them. So the next time you bite into a po-boy, remember that you’re tasting a piece of history.

It’s a story that has all the trappings of a Hallmark made-for-TV movie, Louisiana style: Two rival po-boy shop owners battle it out in a fierce competition to see who makes the best version of their signature creation and eventually (spoiler alert!) fall in love. And while the plot might sound like something dreamed up by a softhearted Hollywood writer’s room, it’s the real, honest-to-goodness way that Justin Kennedy of Parkway Bakery in New Orleans and Becca Murphree of Olde Tyme Grocery in Lafayette began their life together. And it all started — as so many good tales do — with a sandwich.

“In 1929, Benny and Clovis Martin, former streetcar conductors, retired and opened a grocery store and coffee stand on North Peter Street, right at the head of the French Market, called Martin Brothers Coffee Stand. When the Great Depression hit the country, New Orleans was really impacted through the streetcar workers. Those guys weren’t getting paid, so they went on strike,” explains Kennedy. “So,

Benny and Clovis said, ‘Look, you come to our coffee stand, show us your badge and we’ll feed you; we’ll feed our poor boys.’

P-O-O-R B-O-Y-S.”

There was one big issue with feeding so many people with one loaf: It needed consistency from beginning to end.

“What made [the po-boy] different from just a regular French bread sandwich is that the French bread baked at the time was wide

in the middle and skinny on the end, so when you had the soup line with guys trying to get their sandwich, the person on the end would get a little skinny piece [of sandwich] and the guy in the middle would get a big fat piece,” Kennedy recalls. “John Gendusa, whose family is still in business today at the bakery on Mirabeau Street, solved this problem by coming up with a 36-inch loaf consistent from beginning to end: the poor-boy loaf. It caught on and got really popular. Parkway was one of the places that started baking that consistent loaf. Then we started making po-boys and calling them po-boys. I have pictures of two guys sitting out front at the restaurant in 1929 when a po-boy was 10 cents!”

Fast-forward 87 years to 2016, and po-boy shops are scattered in neighborhoods not just across New Orleans, but all of Louisiana and the Gulf Coast, including Olde Tyme Grocery in Lafayette, which has built up a devoted local following for its delicious sandwiches and familial, convivial atmosphere since opening in 1982. Kennedy, who started working at Parkway at 18 and has devoted the last 20 years to the business, was running day-to-day operations at the legendary po-boy stalwart when a national competition crossed his radar — along with

Po-boy shops are a tapestry, weaving together the ins and outs of daily life in cities, towns and wide spots in the road across Louisiana with an ease of connection that would be impossible to replicate if they were uprooted and moved elsewhere.

this little shop two hours west that he’d never heard about.

“USA TODAY put a competition poll out back in 2016 to see who had the best po-boy in Louisiana through how many votes each place received. At first, I said, ‘No, I don’t want to take part in that. I have too much to worry about.’ But then I didn’t want us to be dead last in the competition, so I started getting into it. I swear, it was like running a political campaign: getting all your friends involved, reminding your family to vote every day. I was on the local news. Before our staff punched in, we had it set up to where they had to vote! I’m not saying it was all legit, either: Being from New Orleans, people know how to hustle and vote, and I was getting votes any way I could. It wasn’t just from natural customers, I’ll tell you that.”

Parkway was holding steady toward the top of the po-boy competition ranks when, all of a sudden, a serious competitor emerged: Olde Tyme.

“Knowing all that I was doing to get votes — reminding customers, posting on social media, getting business partners, putting signs up, QR codes at the restaurant, all kinds of craziness — there was this place called Olde Tyme Grocery in Lafayette that

Photo by Rush Jagoe

Photo by Rush Jagoe

was getting more [votes]. All of a sudden, they’d be in first, and you could see it live, too! That’s what made it fun. They jumped to number one, and they were holding at one, and I’m thinking at the time, ‘Lafayette’s the country, right? How’s this country place beating us?’” Kennedy laughs. “I know better than that now — it is definitely not the country. We even went undercover to check the place out, and it was just like Parkway: a nice, busy po-boy shop. It started to turn into a little battle between the two of us. They got wind, because when I saw they were winning, I was like, ‘Well, if you can’t beat them, join them; whatever they’re doing, we’re going to do!’ I ended up pulling it off, and Parkway got first place with a week left. I don’t think I would do that again, but I’m glad I did it that time, because I met my wife.”

After going tit for tat in such an immersive, intense po-boy battle, Kennedy and the Parkway team decided to make a visit to Olde Tyme in Lafayette that was a little less, well, sneaky to meet the family who gave them a true run for their po-boy money. “We went and visited the [Murphree] family at Olde Tyme, and they’re a beautiful family. I met Becca, who’s a beautiful girl, but when you notice beauty, you don’t just ask them out or nothing like that. So, that never happened. I remember my aunt, because I was single at the time, doing ‘the nudge’ on the way home, because aunts are always trying to set you up, like, ‘Huh? What about her?’ I said, ‘What am I going to do? Come up here and ask her out? That ain’t happening.’ So, I kind of forgot about the whole thing, and went back to New Orleans.”

After the nail-biter of a competition, Kennedy kept loosely in touch with the Murphree family, bouncing ideas around about the sandwich business. By 2020, they were trading tips and tricks for navigating the day-to-day of restaurant operations during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, when Becca called Justin out of the blue: She wanted to visit Parkway to see if it would be the right spot for the Krewe of Iris to hold a future luncheon.

“I told her, ‘That’s fine, but I’m on unemployment. We’re closed. When we open, I’ll give you a call!’” Justin chuckles, remembering the era of his “COVID beard” and no-shave days. After two-and-a-half months, Parkway officially reopened in May 2020, and ringing up Becca was at the top of Justin’s

list. “I called to tell her we’d be opening on a Friday, and by golly, she was there on Saturday morning all dressed up and stuff. I can’t blow no smoke. When I saw her, I knew why she was there. We weren’t even having Mardi Gras the next year! I quickly got the hint, asked her out, and on our first date, I took her to Biloxi on Old Highway 90 and we had lunch in Bay St. Louis — a nice little drive.”

By August 2021, Justin knew the relationship was getting serious, and decided to propose with Lake Tahoe, California — a place he’d first visited with Hogs for the Cause team members — as the sweepingly scenic, romantic backdrop. Life, however, had other plans.

“When we got to Lake Tahoe, the first day was nice, but by the second and third days there were wildfires all over California, and Lake Tahoe is just a basin, so all the smoke went over the mountains and fell into the lake so you couldn’t even see your hands in front of your face. It was crazy. So, my original idea to propose on a boat was canceled. Then, toward the end of the trip, Becca’s coughing, I’m kind of coughing, and we’re coughing a little heavier, and we’re thinking it’s the smoke — but we both had COVID. I ended up putting the ring in a medicine bottle and leaving it on the side of the bed. In hindsight, that started up the ‘in sickness and in health’ part of marriage real quick!”

Becca and Justin married in January 2022 at the Grand Hotel in Point Clear, Alabama, during a three-day celebration packed with family, friends — and only one po-boy. The groom’s cake was decorated to resemble a hyper-realistic shrimp po-boy, dressed, with papers from both Olde Tyme and Parkway peeking out from underneath the sandwichshaped cake.

Since the wedding, the couple’s commitment to their respective family restaurants hasn’t wavered, with both Becca and Justin still clocking plenty of overtime while commuting between their two po-boy havens down (of course) Old Highway 90. “I’m still a New Orleans resident; she’s still a Lafayette resident. We don’t know what we’re going to do just yet. She works the restaurant business just like I work it — it’s still 50-plus hours per week!”

The couple is also expecting a baby who, without a doubt, will grow up with a deep appreciation for the pedestal-like

place that po-boys hold in nourishing the people who make Louisiana’s communities so rich. (It’s also not difficult to imagine that the kid’s first words might be, “Dressed or undressed?”) “I think home base for the kid is going to be Lafayette, because she has more family surrounding her over there than I do in New Orleans, but this kid is going to be entrenched in New Orleans culture and Lafayette culture. It’s going to be neat for my kid to see both these places. It’s going to be a well-rounded Louisianan!”

And what a colorful childhood — filled with heart-bursting love of place — that will be. Po-boy shops are a tapestry, weaving together the ins and outs of daily life in cities, towns and wide spots in the road across Louisiana with an ease of connection that would be impossible to replicate if they were uprooted and moved elsewhere.

“If I had to go work in a hotel or whitetablecloth restaurant or something like that, I wouldn’t do it. I’d only run Parkway Bakery — that’s it,” says Justin. “You go to these nice white-linen restaurants and look, they’re beautiful, but there’s only a certain type of person who can afford that. You’re not going to get everybody going in there. Not everybody feels comfortable going in there! Also, not everybody feels comfortable going to eat at a corner store. But a po-boy shop, it attracts all walks of life: eight to 80, young and old, all ethnicities. You’ll have people sitting at the bar together, and one guy could be a millionaire and the other person could be someone who can barely afford that sandwich, and they’re striking up a conversation.”

It would be simple to imagine that memorable sandwiches are the reason po-boy shops keep their tables packed from morning to night, but Kennedy knows it’s more than that — it’s the people.

“You have to have good food to attract people to your restaurant, but that ain’t the reason I’m there. I like it because it’s the heartbeat of the city. I’ve seen old-timers who died 15 years ago who would tell stories about New Orleans you wouldn’t believe. I’ve seen little kids sitting on their mom and dad’s laps who are now doctors! I’m getting to that age where you’re start to see life happen in front of you. That’s what Parkway is. I can see the city of New Orleans every day without leaving the store.”

Courtesy Olde Tyme Grocery

Courtesy Olde Tyme Grocery

One might assume a top-quality po-boy has to come from a sit-down establishment — or at least a specialty shop. It’s true that you can get a mighty fine sandwich at a real restaurant, but you can also find po-boys worth a special trip at convenience stores, gas stations and dive bars across the Gulf South and beyond, often offered at bargain prices.

It’s no coincidence that the early years of the po-boy coincided with the start of the Great Depression, when the American people had to pinch pennies, and the mobility revolution facilitated by the widespread adoption of the automobile. In the 1920s and 1930s, people needed cheap food that they could take from one place to another.

Convenience has always been a key part of any sandwich’s success, and you might think of it as a defining characteristic of the po-boy. In the Deep South, the po-boy was a pioneering fast food, developing in New Orleans before arriving in places like Biloxi, Mobile, Pensacola, and beyond, long before the drive-thru hamburger joint. Many a po-boy puts together a protein (meat or seafood), vegetables (lettuce and tomato), a starchy carbohydrate (the bread) and maybe even dairy (cheese) in a sturdy package. It’s really an all-in-one meal, built to travel in a way that is equaled by few others native to the region.

In the days before cellophane, Styrofoam and cardboard food packaging, a po-boy could be assembled, hot or cold, then wrapped in a sheet of butcher’s paper and secured with a piece of tape. The sandwich could then be tucked under an arm, stuffed into a bag or simply taken outside to be unwrapped and consumed on the spot.

That practicality has served the sandwich well throughout its history. The first known specific published reference to the po-boy, from November of 1929, describes a scene outside the courthouse in Pointe a la Hache, downriver from New Orleans. During a break in a high-profile trial, journalists, lawyers and onlookers went to a nearby lunch stand and ordered sandwiches to go — not to sit down and eat inside a restaurant. “Presently, the tree-shaded courthouse lawn was dotted with groups gnawing at the huge sandwiches New Orleans knows as the ‘po-boy sandwich,’” wrote the New Orleans States

Another description of the po-boy in its infancy, from a magazine published by the state Department of Conservation, details how young men from New Orleans would catch the old Smoky Mary train on Elysian Fields in the 1920s and ride out to Milneburg, a party town largely built on piers over Lake Pontchartrain. The men would grab food and drink before hopping aboard, armed with “three huge schooners of beer and three large ham or cheese

poboys (sic),” a package deal that cost them a grand total of just 15 cents at the old train station at Chartres Street.

Today, going to a convenience store or gas station for a po-boy may be the closest thing to the original po-boy experience. To maximize your pleasure, look for places that do a lot of business. That means that there is a lot of demand for the product — a good sign — and it also translates into fresh ingredients and sandwiches assembled on the spot. If you’re not sure how long the fried shrimp

has been sitting out or when the lettuce was sliced, feel free to ask. The people who make po-boys at mom-and-pop stores are proud of their quality, knowing that word of mouth goes a long way toward making or breaking a business’s reputation.

My experience is that fried shrimp and fried oyster po-boys are particularly well-suited for transportation but, with perhaps a few exceptions (such as a sloppy debris-filled roast beef po-boy), the contents of almost any po-boy will survive for hours.

Some quick-stop po-boy spots have turned the sandwich into an art form. Here are some excellent ones to try:

Today, going to a convenience store or gas station for a po-boy may be the closest thing to the original po-boy experience.

Kellie’s carries all the classics. No frills. None needed. Try the “Kellie’s Special” with roast beef, ham and cheese. Better grab some napkins. Save half for me?

“That’s the place to go,” says my girlfriend, and she knows what she’s talking about. It’s inside a gas station, and there’s always a line. By the time it’s your turn to order, your mouth will be watering and you’ll know exactly what to get. You can’t go wrong with anything on the menu, but because it’s Grand Isle, you might as well get a seafood po-boy.

This gem has carved out its own niche, presenting a “dressed and pressed” po-boy that will leave you impressed. There are also locations in Gulfport and Ocean Springs. My advice is to try them all. Rinse. Repeat.

This flagship location sits right next to a gas station. It has both bánh mi (a Vietnamese sandwich that resembles the po-boy in shape and in function) and traditional po-boys, in all the flavors.

Courtesy Jo-Bob’s Gas & Grill

Courtesy Banh Mi Boys

Courtesy Fayard’s Courtesy Kellie’s Poor Boy Express

Courtesy Jo-Bob’s Gas & Grill

Courtesy Banh Mi Boys

Courtesy Fayard’s Courtesy Kellie’s Poor Boy Express

At Pepperidge Farm, we have been honing and perfecting our chosen craft for generations, and our bakers care deeply about what that means. It’s the little things that make food taste special. We believe in doing things right, and we just happen to love it.

We have a long standing tradition of producing high quality, great tasting pork. Our products are fresh, tender and juicy, and we’re sure to exceed your expectations.

Scan for Recipes!

WE ARE A PROUD PARTNER OF ROUSES MARKETS

There is a specific joy that’s found in snacking on a bánh mì sandwich, whether you’re grabbing one from a strip mall in New Orleans East or picking up breakfast from a food cart on a winding, cobblestone street in Ho Chi Minh City. Unlike so many makers of between-the-bread creations that rely too heavily on a sweeping smear of condiments or stacks on stacks of meat to make them delectable, the Vietnamese know that sandwiches — just like any fine-dining dish or high-end cocktail — need balance. This often means a rainbow’s worth of colorful vegetables — including pickled carrots, stark-white julienned daikon and red-hot chile slivers — adorned with a drag through the garden of fresh herbs like cilantro, and nestled in a bed of buttery mayonnaise and pork sausage, meatballs, ham or chicken that’s been stuffed into a delicate, flaky baguette.

But the bánh mì isn’t just a decadent, thoughtful sandwich: It’s a holistic picture of Vietnamese history in a single bite. The ingredients that make up the “bánh” (bread) and “mì” (wheat) reflect Vietnam’s colonial history, specifically the intersection of French colonialism and local Vietnamese ingenuity. While the French introduced two staple building blocks of the bánh mì to Vietnam, the baguette and liver pâté, the Vietnamese masterminded their own version of the baguette using rice flour, due to wheat’s exorbitant cost as well as French gatekeeping of the delicious (but expensive) bread. The reimagined baguette proved to be an ideal vehicle for an on-the-go bite for workers, and shop owners responded in kind by adding a balanced meal’s worth of nutritious, sustaining filling to the portable snack.

“My father’s eighty-something-year-old friends recall that around the early 1940s, Saigon vendors started offering bánh mì thi nguoi, an East-meets-West combination of cold cuts stuffed inside baguette with canned French butter or fresh mayonnaise, pickles, cucumber, cilantro and chile,” writes Andrea Nguyen in her 2014 book, The Banh Mi Handbook: Recipes for Crazy-Delicious Vietnamese Sandwiches . “Somewhere along the line, the term bánh mì came to signal not only bread but the ubiquitous sandwich.”

Mass emigration in the wake of the Vietnam War has seen the banh mi become synonymous with Vietnamese cuisine, as sandwich lovers the world over have become devotees of the bánh mì’s marriage of crunch and tang. The Vietnamese poet Nguyen Đình Chieu wrote in an 1861 poem that people “splitting sweet wine, gnawing bánh mì” was a common sight in Vietnam in the mid-19th century and now, in the 21st century, this merry act is replicated across the globe on a daily basis, cementing the sandwich’s place as a culinary icon.

ARROW-CIRCLE-RIGHT Bánh mì were mostly found at Vietnamese-owned restaurants, groceries and convenience stores serving Vietnamese communities in New Orleans East and on the West Bank before Katrina hit in 2005. As the city rebuilt, Vietnamese restaurants opened in new parts of town. Today you can find bánh mì in restaurants across New Orleans, and on menus all over the Gulf Coast. This one is from Trinh “Lilly” Vuong’s eponymous restaurant, Lilly’s Cafe (in the Lower Garden District of New Orleans), which is a favorite of many at Rouses Markets.

The bánh mì isn’t just a decadent, thoughtful sandwich: It’s a holistic picture of Vietnamese history in a single bite.

ARROW-CIRCLE-RIGHT

We make our own ham, turkey and roast beef po-boys at most stores. The bread is baked fresh daily, and we use our own fresh produce and deli meats, which we slice in-house. Our sandwich wraps, sandwich wedges and King’s Hawaiian sliders are also made in-house.

Makes 6-8 servings

We bake our New Orleans-style French bread loaves in-house; they are perfect for po-boys. And when the bread gets a tiny bit stale, they’re the perfect main ingredient for our old-fashioned bread pudding. Where available, we also get French bread from local bakeries

4 cups whole milk

4 tablespoons (½ stick) unsalted butter, plus more for greasing pan

1 tablespoon vanilla extract

1 cup granulated sugar

1 teaspoon cinnamon

Pinch ground nutmeg

1 cup granulated sugar

Pinch salt

4 eggs, beaten

1 loaf stale French bread, cut into 2-inch cubes (about 5 to 6 cups)

Preheat oven to 350°F.

In a small saucepan over low heat, warm milk, butter, vanilla, sugar, cinnamon, nutmeg and salt. Continue cooking just until butter melts; let cool.

Meanwhile, grease a 4- to 6-cup baking dish with butter or nonstick spray and fill it with the cubed bread.

Add eggs to cooled milk mixture, and whisk thoroughly to incorporate. Pour mixture over cubed bread and gently stir to coat. Let sit for 5 to 10 minutes before baking so that the bread can absorb some of the liquid.

Place pan in preheated oven and bake for 30 to 45 minutes, or until custard is set but still a little wobbly, and edges of bread have browned. Remove from the oven and serve hot or warm.

Love at First Bite, the catering business run by Walker’s Southern Style BBQ in New Orleans East, began selling their cochon de lait po-boy at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival in 2001. Now you can get this warm shredded pork po-boy with cold cabbage and a homemade horseradish sauce at festivals all over Louisiana. You can also order it at their restaurant. The Galley in Metairie is home of the whole soft-shell crab po-boy served at The New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival since 1977.

Crabby Jack’s in Jefferson is JacquesImo’s owner Jack Leonardi’s lunchtime spot. The duck po-boy is slow-roasted, pulled duck served with a brown-gravy

duck debris. It is a festival favorite. The Yakiniku po-boy from Ajun Cajun in New Orleans is a thin-sliced ribeye steak and onion sautéed in garlic sauce, topped with mozzarella cheese, and dressed with pickled carrots and zucchini and Japanese Kewpie mayonnaise. It’s as if a Philly cheesesteak and a bánh mì had a baby. Creole hot sausage po-boys from the Vaucresson family have been part of every New Orleans Jazz Fest since the first one in 1970. Vaucresson Sausage Co. returned to the Seventh Ward in New Orleans nearly two decades after their building was destroyed in Katrina.

Italian sausage, ground beef and hot sausage mixed into a single, griddled patty. Sammy’s Food Service & Deli on Elysian Fields in Gentilly is known for its hot sausage and smoked sausage po-boys, along with the Ray-Ray, a combination of Southern fried chicken, grilled ham and Swiss cheese. Their roast beef is cut thick and served on slightly toasted bread. Li’l Dizzy’s in Treme serves a hot sausage po-boy using links, not patties; it is made in-house. Dempsey’s in Baton Rouge has some of the best gumbo around. At Dempsey’s Seafood & Steak in Kiln, Mississippi, the hot sausage po-boy has grilled spicy sausage patties on French, dressed to order.

The Judge Bosetta at Johnny’s Po-Boys in the French Quarter features

The best roast beef po-boys are judged by how many napkins you go through. The roast beef at Darrell’s Famous Poboys in Lake Charles is one of the messiest — and one of the most delicious. At Parkway Bakery in New Orleans, they toast their French bread until the interiors are just browned — it makes the po-boy sturdier — before adding lettuce, tomatoes, pickles, mayonnaise, roast beef and gravy. Over at Parasol’s in the Garden District, they toast their po-boys whole. R&O’s Restaurant in Bucktown’s offering was voted best roast beef po-boy in New Orleans by a local newspaper. It’s made with oven-toasted sesame bread and it’s deliciously sloppy, with tons of house-made gravy.

The Napoleon House in the French Quarter may be best known for its muffaletta, but don’t sleep on the messy roast beef po-boy. It’s a 10-napkin versiont. At Frady’s One Stop Food Store, a Bywater landmark, you can

have your roast beef on sliced bread, French bread or a bun. Up to you.

The roast beef po-boy at Rocky & Carlo’s in Chalmette is topped with the same brown gravy that’s very popular on the restaurant’s veal cutlet, stuffed peppers and, of course, their famous baked macaroni.

KY’s Olde Towne Bicycle Shop in Slidell makes one of the best roast beef po-boys in The Dell. The circa 1902 building has a great history, too.

Bear’s Restaurant in Covington is a North Shore institution, and roast beef is the top seller there and at its sister sandwich spot, Bear’s at Gennaro’s in Old Metairie.

Jefferson Parish has so many great roast beef po-boys, like those at Radosta’s in Metairie and Chateau Orleans in Marrero. Short Stop Poboys on Transcontinental in Metairie has been serving po-boys since 1966. They have over 30 different types of po-boys, but their debris-style roast beef is not to be missed. The roast beef po-boy at World Deli on Clearview Parkway at West Esplanade is another must-try. If you can wait till Friday, Mo’s Pizza in Westwego has a Fridayonly roast beef po-boy special.

The roast beef po-boy at Pirate’s Cove in Pass Christian is drenched with brown gravy, dressed with mayonnaise, lettuce and tomatoes. The gravy for the famous roast beef po-boys at Lil’ Ray’s in Gulfport is made in-house.

kinds of mustard (Creole and yellow), mayonnaise and pickles. Add Swiss cheese and you have a Ralph.

The Darrell’s special at Darrell’s Famous Poboys in Lake Charles is piled high with ham, turkey, roast beef and your choice of cheese, then drenched in their homemade roast beef gravy; ordered it dressed with their homemade jalapeño mayonnaise.

was recently ranked the best shrimp po-boy on onlyinyourstate.com

The fried seafood, including shrimp and oysters, at Bozo’s in Pascagoula is perfectly fried. The shrimp po-boy features plentiful portions of the freshly fried seafood.

Kenny’s Seafood in Slidell serves a serious shrimp po-boy. If you can pass up the shrimp boulettes at Bayou Blue PoBoys in Houma — come on, you can do it — order the shrimp po-boy. You won’t regret it!

There’s a reason tourists (and locals) line up around the block for the Ferdi special at Mother’s Restaurant in New Orleans. The Ferdi is baked ham, roast beef, debris, and gravy, dressed with shredded cabbage, two

Parkway Bakery has been making po-boys since 1911 and, while it is known for its roast beef, the shrimp is right up there alongside it. Domilise’s and Guy’s Po-Boys are two of Uptown New Orleans’ best choices for fried shrimp poboys, although you can’t go wrong with gravy-soaked roast beef at either eatery. Guy’s Chef/Owner Marvin Matherne also serves up great daily specials. Adams Street Grocery & Deli is a hidden gem, with generously portioned shrimp po-boys at a great price.

The shrimp po-boy at Olde Tyme Grocery in Lafayette has been called “Acadiana’s gold standard” for shrimp po-boys. In nearby New Iberia, the fried shrimp po-boy at Bon Creole Seafood is generously overstuffed — and delicious.

The owner of Rocco’s New Orleans Style Po-Boys & Cafe in Baton Rouge opened his first po-boy shop 25 years ago on West Chimes Street just outside of LSU, so he has his bona fides. His fried shrimp po-boy, a neighborhood favorite,

Don’t just think fried for shrimp. Spahr’s Seafood serves a blackened shrimp po-boy that’s dressed with fried green tomatoes, lettuce mix and “creolaise.” (They also make a great fried shrimp po-boy.) Seither’s in Harahan has a blackened shrimp with avocado. And the BBQ shrimp po-boy is the signature po-boy at Liuzza’s by the Track near the Fair Grounds in New Orleans.

Felix’s Fish Camp in Spanish Fort, Alabama (near the town of Daphne) on Mobile Bay enjoys some of the most scenic sunsets around. But it’s the seafood po-boys — including a fried crawfish tail po-boy — and the crab soup that keep people coming back. Thin cornmealcrusted catfish stars among the takeout po-boys at Zimmer’s in Gentilly. The

Seafood Platter po-boy at Bon Creole in New Iberia holds fried shrimp, catfish, crawfish and oysters. And while the seafood muffaletta at Parran’s in Kenner, Metairie and New Orleans isn’t technically a po-boy, it does feature fried shrimp, catfish and oysters in a spicy homemade Cajun mayo. It’s hard to pass up the plate lunches at Rita Mae’s Kitchen in Morgan City, but the crab cake po-boy at this little house-turnedrestaurant is delicious.

area, is like a Philly Cheesesteak with provolone cheese and fried shrimp.

Casamento’s in New Orleans is famous for its oyster loaf on Texas-size toast. And Ye Olde College Inn, which is down the street from our Carrollton store, is a favorite for their onion rings and oyster loaf (which is pretty much just an oyster po-boy). But it’s Lower Alabama where you find the most seafood loaves. The fried shrimp and oyster loaves at both Lulu’s in Gulf Shores and the Dew Drop Inn on Old Shell Road in Mobile are excellent.

The Surf & Turf at Darrell’s Famous Poboys in Lake Charles has roast beef and sautéed shrimp that’s been cooked in their roast beef gravy and homemade butter sauce. They give you plenty of napkins, and you’ll need them. You can’t miss with the fried shrimp with roast beef debris at Domilise’s or Parkway Bakery. Go for it and order it dressed, with cheese.

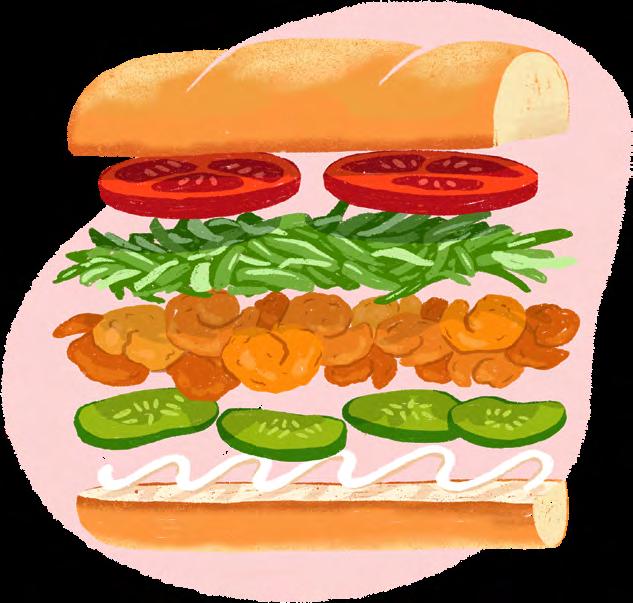

American Market — affectionately known as AM Mart — is an LSU student favorite. Get a po-boy, Zapp’s chips and a drink for under $10 at this corner store on Nicholson and Lee. Dressed here means mayonnaise, mustard, lettuce, tomatoes, pickles and salad dressing.

The Peacemaker, a combination of fried shrimp, swiss cheese, roast beef gravy and debris, at Bevi Seafood in New Orleans is fantastic. Acme Oyster House (multiple locations) tops fried oysters and fried shrimp with Tabasco-infused mayo. And the Steak Bomb at Po-boy Express, with several locations in the Baton Rouge

If you’re a meat-and-potato person, get the French fry po-boy topped with house-made beef gravy at R&O’s Restaurant in Bucktown.

BBQ chicken confit, glazed pork belly, and ham & pimento cheese are just some of the unusual offerings at Killer Poboys, which has two locations in the French Quarter.

At Julien’s Po-Boys in Lafayette they boil the ham for their Ragin Cajun po-boy in crab boil, then top it with melted jalapeño cheese, mayonnaise and lettuce. Chef Collin Cormier and his team at Pop’s Poboys in Lafayette, put their own creative spin on po-boys like Banh Banh Shrimp, Crawfish Boil Sausage and Red Bean Falafel.

You can smell the French bread baking when you walk into our Rouses stores. Our po-boys are piled high with freshly sliced turkey, ham or roast beef, with or without cheese, and dressed with fresh lettuce and tomatoes.

The po-boy purveyors of the Gulf South serve a vast variety of sandwiches. You’ve got your classic roast beef, often soaked in a bath of gravy. Fried shrimp and softshell crab are enduring favorites. Then you’ve got your hot sausage po-boy, you hamburger po-boy, or your basic sliced ham or turkey and cheese. Some places even serve a po-boy made with French fries and meaty gravy. And there are any number of combinations and lesser-known variants.

But for me, the king of po-boys will always be the fried oyster version. It’s always been my favorite. There’s really something special about flash-frying fat, salty Gulf oysters, sealing in their flavor, and then piling them into a fresh po-boy loaf, with thinly sliced lettuce and tomato, pickle slices and a smear of mayo. Sometimes I add a dash of hot sauce, but more often, I don’t have the patience to tweak something that’s already this close to being perfect. I know I’m not alone. And, in fact, the earliest known predecessors to the modern po-boy have one thing in common: their star ingredient, the mighty oyster.

Oysters are magical mollusks. They filter water. They create reefs that help slow coastal erosion and that minimize storm surge during hurricanes. In Louisiana, the oyster industry brings in hundreds of millions of dollars every year. And oysters have been a delicacy on the Gulf Coast for as long as there have been people here. These bivalves helped make our cuisine famous, and they are a mainstay on the menus of restaurants

from Texas to Florida, and everywhere in between.

They also have a long history in sandwiches. The oyster loaf dates back to at least to the 1700s, when an edition of Eliza Smith’s The Compleat Housewife, the first cookbook published in America, provided this convoluted yet compelling recipe: Take a quart of middling oysters, and wash them in their own liquor; then strain them through a flannel, and put them on the fire to warm; then take three quarters of a pint of gravy and put to the oysters, with a blade of mace, a little white pepper, a little horse-radish, a piece of lean bacon, and half a lemon; then stew them leisurely. Take three penny-loaves, and pick out the crumb clean; then take a pound of butter, and set on the fire in a sauce-pan that will hold the loaves, and when it is melted, take it off the fire, and let it settle; then pour off the clear, and set it on the fire again with the loaves in it, turning them about till you find them crisp; then put a pound of butter in a frying-pan, and with a dredging-box dust in flour till you find it of a reasonable

thickness, then mix that and the oysters together; when they are stewed enough, take out the bacon, and put the oysters into the loaves; then put them into a dish, and garnish the loaves with the oysters you cannot get in, and with slices of lemon; and when you have thickened the liquor, squeeze in lemon to your taste; or you may fry the oysters with batter to garnish the loaves.

The oyster loaf’s first known mention in New Orleans came in an 1851 newspaper ad that described hollowing out an entire loaf of bread, to fit in more oysters that would go into a loaf that had simply been cut in half lengthwise. But the interpretation of the modern oyster loaf depends on where you go. Many places simply call their oyster po-boy an oyster loaf. Others use sliced bread for a sandwich that they also call an oyster loaf.

Confusing things further is the peacemaker moniker. That name, a marketing gimmick, was first applied to an oyster sandwich served on a long loaf of bread in New Orleans. We’d recognize it as a grandfather of the po-boy today. The concept behind the peacemaker was that, when women were prohibited from patronizing the saloons of the city, they might be displeased that their husbands spent a great deal of time in those saloons. But their ire would be placated when their husbands came home with a piping hot oyster po-boy — it would bring about domestic peace.

Over the years, though, that definition has changed. Some places now call a sandwich that is half oyster, half shrimp a peacemaker, the thinking being that it offers a compromise to the discerning diner who has difficulty deciding between the two.

It can be confusing. There’s probably a punch line in development for a joke about an oyster po-boy, a peacemaker and an oyster loaf walking into a bar. But

The months of February, March and April are prime time for large, salty Gulf Coast oysters. Serve them fried on French bread, Texas toast or thick sandwich bread.

8 slices thick-cut white bread

2 tablespoons unsalted butter, at room temperature

Vegetable oil, for frying Rouses Fish Fry Mix

3 dozen large oysters, shucked, not rinsed Mayonnaise

Shredded lettuce, for serving Sliced tomato, for serving Sliced dill pickles, for serving Hot sauce

Lemon wedges, for serving

Preheat the broiler. Lightly butter the bread on both sides and set aside.

Line a baking sheet with paper towels. In a large, heavy-bottomed pot fitted with a deep-fry thermometer, add enough oil to reach 4 inches up the sides of the pot. Pour Rouses Fish Fry Mix into a shallow bowl. Working in batches, dredge the oysters in the seasoned mix, pressing it onto the oysters to cover them completely, then shake gently to remove any excess. When the oil temperature reaches 370°F, add the oysters in batches and cook, stirring occasionally with a slotted metal spoon, until oysters are golden brown, about 2 minutes. Transfer the oysters to the paper towels on the baking sheet as they are finished cooking, and continue cooking the remaining oysters. While the last few batches of oysters are frying, broil the bread, turning once, until golden on both sides, 30 seconds to 1 minute per side.

Spread 4 of the toast slices with a tablespoon of the mayonnaise. Top with warm fried oysters and dress with lettuce, tomatoes, pickles and hot sauce. Serve with lemon quarters.

Makes 6 servings

For roast beef

1 (3- to 4-pound) chuck roast

Salt and freshly ground black pepper, to taste 2 dried bay leaves

2 tablespoons olive oil or vegetable oil

1 packet ranch dressing mix

2 tablespoons tomato paste

1 packet dry onion soup mix or au jus gravy mix

½ cup (1 stick) salted butter

For po-boys

1 loaf French bread, cut in 6-inch segments

1 or 2 large tomatoes, thinly sliced

Shredded lettuce

Sliced dill pickles

Mayonnaise

Generously season both sides of roast with salt and pepper. Heat vegetable oil in a large skillet over medium-high heat until hot. Add chuck roast and sear on each side for 5-6 minutes each, until well browned.

Carefully remove roast from the skillet and transfer to your slow cooker. Sprinkle the ranch dressing mix and onion soup or au jus mix over the top of the roast. Add the butter, tomato paste and bay leaves.

Cover with the crockpot lid, and cook over low heat for 8 hours or more. Use two forks to shred the meat. Discard any fatty pieces.

Spread slices of French Bread with mayonnaise. Top with warm roast beef and dress with shredded lettuce or cabbage, tomatoes and pickles.

ARROW-CIRCLE-RIGHT Debris — pronounced day-bree — is the name for the bits of meat and crusty char that fall from a beef roast as it is cooking or being sliced and are mixed in with the pan’s drippings.

Born in New Orleans – a city that knows flavor – Blue Plate Mayo’s simple recipe using oil, vinegar and only the egg yolks brings out the delicious in everyone’s favorite comfort foods. Use the rich and creamy taste of Blue Plate to dress up a fried green tomato sandwich on toasted bread, whip up the perfect potato salad for gumbo, mix a spicy marinade for an oven roast – and more.

BLUEPLATEMAYO.COM

When Rouses asked me to write about whether or not a hot dog is a sandwich, I knew I was going to make some enemies. I am still getting hate mail from those of you who like ranch dressing on pizza (which is the culinary equivalent of walking around barefoot in the mall) and those upset by my verdict on waffles versus pancakes (waffles are needy pancakes that require you to buy an appliance you’ll use twice a year). Rouses shoppers have strong opinions about food. But unless your opinion is the same is mine, you are wrong, sadly, and so, here goes: Hot dogs are not sandwiches. Hamburgers aren’t sandwiches, either. Before you begin your letter-writing campaign, however, hear me out. We are going to do a deep philosophical exploration of what is a sandwich. If, at the end, you disagree with me, you will still be wrong, but at least you will be better informed about how wrong you are.

First, we should probably talk about where sandwiches come from. The sandwich as we know it goes back to John Montagu, the 4th Earl of Sandwich, who distinguished himself from the three earlier earls by being a devoted gambler who did not want to stop playing cards to have dinner. While at the tables, he thus ordered a meal of meat between two slices of toasted bread, which did not require a fork to eat and allowed him to play without getting his cards greasy. His gambling addiction is the world’s gain. The food became the rage of London — people ordered “the same as Sandwich” — and it remains the greatest, if not only, culinary gift that England has ever bestowed upon the world. (Considering its other gifts are weird meat pies, and steak and kidney pudding, it’s not like there was much competition.)

Yes, people had come up with the notion of a sandwich before Montagu, but it was called (really) “bread and meat,” and sometimes “bread and cheese.”

Fast-forward to today: Let us consider the definition of a sandwich according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), which ought to know. A “closed sandwich,” it says, is made of “at least 35% cooked meat and no more than 50% bread.” An open sandwich, meanwhile, is “at least 50% cooked meat.” First, I should say that there is no such thing as an open sandwich. An open sandwich is a slice of bread with things on top. Avocado toast is an open sandwich, which is self-evidently not a sandwich. Moreover, a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, which, I will argue, is most definitely a sandwich, would not be according to the USDA due to its lack of meat. Their definition is a mess, and until it is corrected, the USDA should be defunded immediately. Our tax dollars deserve better.

Okay, so the government got it wrong. No surprise there. But what about the dictionary? It’s not every day that I can cross swords with the USDA and Merriam-Webster, but seemingly from thin air, the dictionary authors decided that a “split roll” could also be included in the sandwich description, which of course is wrong. I’m going to declare for the world that a sandwich requires a minimum of two (2) slices of bread. More is fine. You can make a club sandwich with three slices of bread, no problem. (A Big Mac, however, which also contains three parts of bread, is not a sandwich. It is a hamburger, as we will discuss.) But one slice of bread is not a sandwich. It’s a roll-over, maybe. Or it’s a toast of some sort. If nothing else, consider that a single slice of bread with toppings, folded over, would allow one of those giant slices of overrated New York pizza to be considered a sandwich. Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, according to the dictionary definition, by the simple act of folding it in half, it would be magically

“Sandwiches may only be born of bread intended to be sliced for multiple servings.”

transformed into a cheese sandwich with tomato sauce. We know that not to be true, and can disregard it with no further consideration.

I propose that a sandwich is defined not by the ingredients delivered, nor by the mere presence of bread, but by structure. Like a hologram or fractal, every single element of a sandwich must spiritually conform to, and contain the nature of, that which is sandwichness.

Furthermore, sandwiches may only be born of bread intended to be sliced for multiple servings . What do I mean by this? Consider the hamburger bun. It is bread, we agree. And it must be sliced, I admit (a top half and a bottom half). However, a hamburger bun is intended only for a single hamburger. (Or cheeseburger, which is also not a sandwich. Or the aforementioned Big Mac: again, not a sandwich.) Sandwiches are inherently a communal food. By my obviously correct definition, a hamburger is therefore not a sandwich.

“But David,” you say, thinking you have found a loophole, “What if I eat a hamburger patty on slices of Bunny Bread?” First of all, if you are doing that, it means someone at the barbecue forgot to bring buns, and you are probably pretty sad about the whole thing. Secondly, the tragedy is compounded due to the sad fact that no one at least had Evangeline Maid. And while tragic, that hamburger

not quite a hamburger. Rather, it is a mistake — an apostasy, even — with insufficient sandwichness. A sandwich is more than a mere delivery device of things to your mouth. All of the ingredients, together, must cohere elegantly as a sandwich.

Slices of bread are more than mere vessels for — to name a popular topping — peanut butter and jelly. They must instead be intrinsic parts of the whole. No one would lick a spoonful of peanut butter, then shove the spoon into a jar of jelly and add that to their mouth, chewing the two into magenta goo. The texture would be all wrong. The nature of the thing would be abominable. In the case of peanut butter and jelly especially, bread brings not only order, but balance. The two condiments are already in harmony, but they are incomplete, a mere half of a barbershop quartet. Only with the addition of two slices of bread do you achieve coherence. As proof, consider that no sane person would buy hot dog buns, spread peanut butter on one half, and jelly on the other, and eat… whatever you might call that. Even though the ingredients would be the same on a molecular level to a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, it would not be a sandwich.

You see that this discussion is not the result of a mind gone mad, but a mind staving off madness.

Now, consider a muffaletta. It has a bun, yes — a very large one. Within its confines

eat olive salad and cold cuts on their own (though it does sound tasty, I must confess). Bread is required — again, for balance. But — and here is the important part for these arbitrary rules I have defined — a muffaletta is cut into multiple wedges intended for several people (or one very, very hungry person with a cast-iron stomach). By its very nature, it meets the threshold of sandwichness. A muffaletta is, therefore, a sandwich.

We must, while we dwell on New Orleans cuisine, consider another edge case: the po-boy. Long have I meditated on this one. Can a po-boy truly be a sandwich? It is composed, usually, of two slices of bread, and that bread generally feeds multiple people (or at least, is made to be divided into multiple servings). What of its constituents? Here is where I struggle. The ham and cheese ingredients of a ham and cheese po-boy can be eaten on their own, as anyone who has ever ordered charcuterie or eaten Lunchables can attest. The fried shrimp of a fried shrimp po-boy, obviously, can be eaten on its own, and if we include the thinly shredded lettuce that usually dresses it, yes, it would make a tasty shrimp salad, no bread needed. Therefore, a po-boy is not a sandwich. Its po-boyness is simply too strong. (Consider that no one would ever order a peanut butter and jelly po-boy, which is also proof of the sandwichness of a PB&J.)

The above example challenges the

and cheese together is a snack. Meat and cheese on slices of bread is a satisfying meal, as the 4th Earl of Sandwich recognized in the 18th century.

What about an ice cream sandwich? I think you already know the answer. First, the chocolate cookie-ish cake part is not bread, and second, ice cream is ice cream. Nice try, dessert menu, but not on my watch. (They do have harmony, though, I will give you that…)

Which brings us, at last, to the hot dog. As discussed, a hot dog bun, though bread, yes, and though sliced (though not completely in two, making it ineligible to be a sandwich ex vi termini), it is still intended only for a single hot dog eaten by a single person, or if you are a parent, a single person, but the parent can finish whatever the child does not. But also, the actual hot dog itself — the meat part — is too weird for a sandwich. Like a po-boy, a hot dog is its own thing entirely, and not a subset of sandwich. The fact that I said “hot dog” — which is a meat — and you imagined the bun immediately, attests to how integrated and perfect it is as its own entity.

It is, however, a burrito. But that is a much longer discussion.

ARROW-CIRCLE-RIGHT We’d put this spicy chicken sandwich up against any chicken sandwich out there. Yes, it’s that good. Juicy chicken is coated in our buttermilk fire breading and fried in small batches in our zero trans-fat oil so the chicken stays juicy, while the breading is tender yet crispy. It’s served on a brioche bun with our creamy chipotle ranch sauce and cool dill pickle slices. We are known for our fabulous fried chicken, and this is the best fried chicken sandwich anywhere, and our best-selling sandwich overall.

ARROW-CIRCLE-RIGHT The classic club sandwich is a triple-decker made with three slices of toasted white bread, turkey or chicken, bacon, lettuce, tomatoes and mayonnaise, and cut into quarters. The club is said to have originated at the Saratoga Club House, known now as the Canfield Casino, in upstate New York, in 1894.

We sell our own classic fish sandwich during Lent. Our very popular version features a crispy fish filet patty with American cheese and tartar sauce, served on a soft bun.

The Gulf, Orange Beach

ARROW-CIRCLE-RIGHT The fried grouper sandwich at this outdoor-only restaurant on the beach is as stunning as the views.

Fresh off the Boat, Orange Beach

ARROW-CIRCLE-RIGHT Blackened Gulf fish dressed with arugula, Roma tomato, pickled red onion and signature Beachin’ Sauce on a toasted brioche bun. You can also get it fried or grilled.

Cosmo’s Restaurant & Bar, Luna’s Eat & Drink and Cobalt, Orange Beach

ARROW-CIRCLE-RIGHT Grilled, blackened or fried fish served on a toasted sourdough bun with lettuce, tomato and red onion.

Tacky Jacks, Orange Beach, Gulf Shores, Fort Morgan

ARROW-CIRCLE-RIGHT Grilled, blackened or fried fish served on a toasted buttery brioche bun.

Fisher’s Dockside Orange Beach

ARROW-CIRCLE-RIGHT Cornmeal fried Gulf fish with jalapeño citrus coleslaw served on a brioche bun.

Flora-Bama Ole River Grill, Orange Beach

ARROW-CIRCLE-RIGHT Lightly breaded Gulf fish on a soft sesame seed bun served with house-made tartar sauce. They also offer a grilled mahi-mahi po-boy.

Sassy Bass, Gulf Shores

ARROW-CIRCLE-RIGHT The grilled grouper Reuben is served on grilled rye bread with sauerkraut, melted Swiss cheese and Thousand Island dressing.

The Steamer Baked Oyster Bar, Orange Beach, Gulf Shores

ARROW-CIRCLE-RIGHT You can get a great grilled mahi-mahi sandwich at this restaurant, which was voted a Top 3 Restaurant in Southern Living

ARROW-CIRCLE-RIGHT As far as meat in a can goes, you would be hard pressed to find something more famous than or as instantly recognizable as Spam. Spam was created by Hormel Foods Corporation to find a better use for pork shoulders. Bacon, ham, loin — one animal produces all those things. But the shoulder? People just weren’t buying them, and a sort of culinary Manhattan Project was convened. Hormel knew canned meats. Their first stab at it was in the mid-1920s, with — and this was its actual name — Hormel FlavorSealed Ham. This time, though, they would create the alpha and omega of aluminum-encased pig. The result? Spam. Spam? Spam.

Yeah, you’re probably wondering about that name. I mean, it’s better than “Flavor-Sealed Ham.” The guy who named Spam, Ken Daigneau, did so in a contest, and won $100 for his Shakespearean style etymology. Hormel always capitalizes the word in its entirety, and hints coyly that SPAM is an acronym.

“Pshh, everybody knows that!” you shout. “Spiced ham!”

— Wham, Bam, Mahalo Spam!, David W. Brown, Rouses Magazine, July-August 2020

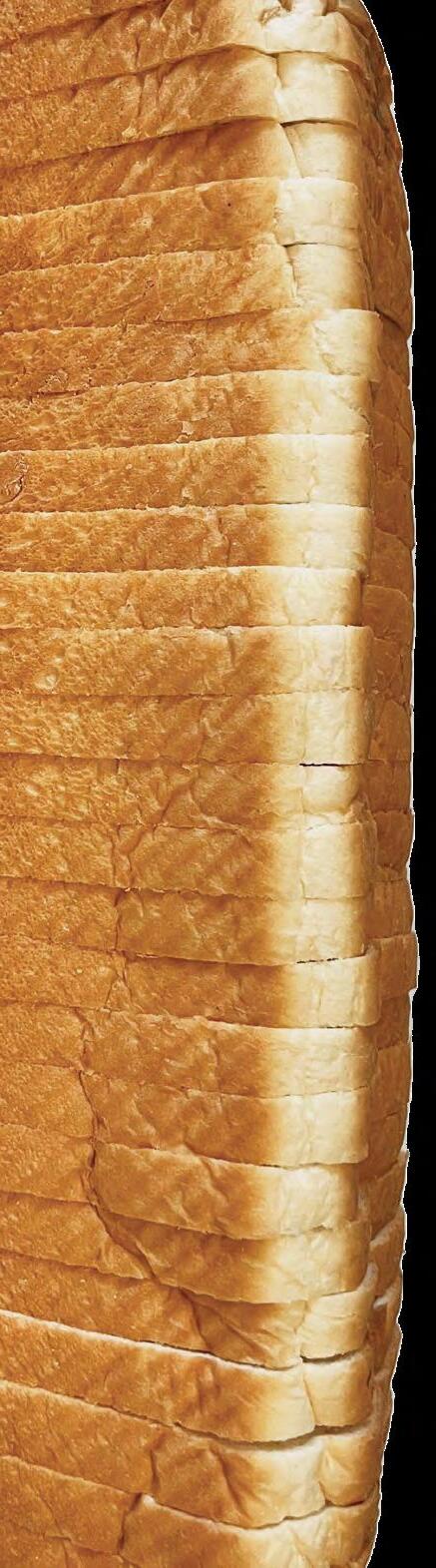

If you somehow managed to create the most impressive and dazzling new thing in all the world, it would still only be the greatest thing “since sliced bread.”

For at least 30,000 years, bread has been the center of human civilization. It nourishes the body and, across cultures and religions, nourishes the soul. A country’s most fertile soils are called its “bread basket,” and the person who makes the money in a household is the “breadwinner.” The breaking of bread is the first act of solidarity between people. (The word “companion” derives from the Latin com, which means “with,” and panis, which means “bread.” Bread is the thing you eat with your friends.) In the Catholic Church, bread is consecrated as the literal body of Christ. In ancient Egypt, it was a form of currency. In 18th-century France, Voltaire said of his people that they need only “the comic opera and white bread.” If you somehow managed to create the most impressive and dazzling new thing in all the world, it would still only be the greatest thing “since sliced bread.”

Every civilization has independently discovered its own form of bread. It is life, and the reason we have thrived since the dawn of humanity. It is also a hyper-localized product. Regional soils nourish different types of wheat in different ways, and different water goes into the making of bread. This affects taste and texture when the dough rises and is baked. (It is one reason New Orleans po-boys are so distinctive — our water somehow yields a bread both fluffier and crisper. Have you ever ordered a po-boy in New York? It would be a war crime.) And because bread is of the Earth and of the local community, people have very strong opinions about their local brands!

In Louisiana, two of the most popular types of bread are Evangeline Maid and Bunny

Bread. The uninitiated think the two are the same, but an enthusiast will tell you in polite, but not uncertain terms, that it is time for you to leave. I will discuss the reason below.

Evangeline Maid bread was born over a century ago in the heart of Cajun country: in Youngsville, Louisiana, just outside of Lafayette. A baker named Joseph Huval had learned his trade in the Army during World War I, came home, and opened a little bakery for $50. Evangeline Maid was thus born. Indeed, it is a family affair. The slender maid that’s always been on its logo is a sketch of Joseph’s daughter, Mary.

And the logo isn’t the only thing that hasn’t changed. The recipe for the bread and the way it is made is the same as ever, only on a much, much larger scale. It is what the people of Acadiana grew up on, and what their kids will grow up on as well. (When I think back to my childhood, I only remember GIANT bread — I can still see it there, those big blue letters on a yellow bag. But GIANT brand it was not. Rather, it was Evangeline Maid; the large loaves were simply given a giant, well, GIANT label.)

Bunny Bread, meanwhile, is not a local bread per se, but everyone sure knows its trademark smiling rabbit on the bag of every loaf sold. The company was founded in 1925 by a trio of brothers — Amos, Arnold and Jack Lewis — who wanted to open a bakery in Illinois. Bunny Bread, as the world now knows it, came along 20 years later, and soon came to be as emblematic of the American Midwest as the wheat fields that yielded it.

Here is where it gets interesting, though. Bunny Bread is made fresh in regional bakeries, including — perhaps more famously even than its Illinois birthplace — in the city of New Orleans. Which means, for the discriminating Louisiana sandwich eater, the bread aisle at your local Rouses can be a flavor competition between Lafayette and New Orleans. After all, we take our food pretty seriously here.

It is worth recognizing that in addition to being great bakers, the Lewis brothers and Huval family were entrepreneurs. Bread was not always a grocery store staple, sliced perfectly and wrapped in plastic bags with twist ties on the end. A hundred years ago, women baked the bread in most family households. The idea of unburdening mothers of that responsibility was pretty

radical, with no guarantee of success. How recent is pre-sliced bread? Pop-up toasters were around before bread-slicing machines were invented.

In many ways, bread is like wine. The reason Italian food tastes better with Italian wine, and vice versa, is that the two were created in conjunction, from the same local terroir, by people with similar palates, flavor preferences and cultural backgrounds. Sometimes intentionally and sometimes subconsciously, chefs and winemakers work toward similar ends, adapting to each other, pushing each other and finding new ways of elevating each other. They achieve balance and harmony without even thinking about it.

In the case of bread, consider Evangeline Maid’s old-fashioned white bread. It is soft and fluffy and absolutely perfect for wiping your bowl after finishing a Cajun dish like gumbo, for which Acadiana is so famous. Did Joseph Huval set out intentionally to make the perfect mop for remnants of crawfish étouffée, or did he naturally come onto the solution because that is the kind of food we eat around here? It is probably a little of both.

If you thought the sometimes bitter rivalry between fans of differing breads was already intense, then brace yourself. Bunny Bread partisans and Evangeline Maid enthusiasts, I beseech you to show restraint and not hurl your pillowy soft loaves of enriched white bread at each other. Because — prepare yourselves for this — both brands are owned by the same company: Flower Foods, out of Georgia. In New Orleans, the bakery that makes Bunny Bread also bakes Evangeline Maid in Acadiana.

It was only a matter of time before two such great things would come together in peace and harmony. Long, after all, is the history

of bread — so long, in fact, that bread has not only been just for eating, either. Anything that has been around for several thousand years was bound to pick up a few extra uses along the way. I’ve already mentioned that it was once a currency in ancient Egypt. Before rubber erasers were a thing, balled-up bread was used to erase pencil markings. In the Middle Ages (and today as well, if you know where to look), bread was baked as the bowl for the meal eaten. This might even be how pizza was born, though the truth is lost in the sands of time. It might even have curative properties, packed as it is with micronutrients.

What is known for certain is that we all love bread. On average, an American will eat 53 pounds of bread per year. This is about the same weight as a mattress of a twin-sized bed which, yes, was the weirdest comparison I could find in my cursory Internet search. (A thousand dollars in quarters also weigh 50 pounds).

But the subject of lost truths and misconceptions brings us back to Evangeline Maid and Bunny Bread. Specifically, some people believe they are the exact same bread in different wrappers. But that just isn’t so! Evangeline Maid is made in a very specific way, and each loaf takes about eight hours from start to finish. It starts the way all leavened bread (that is, bread made with a rising agent) is made: with flour, water and yeast. Of course, unlike bread made at home, bread at the Evangeline Maid factory is prepared in higher volume. It takes about four hours for the big blob of dough to rise, at which point it is cut into loaf-sized portions; their old-fashioned loaves are also hand-twisted, just as they were in the days of Joseph Huval. From there, it is stretched and molded into the shape you know and love, and then goes into trays for baking. After that, it gets a brief trip to the oven, and when it comes out, it is ready to eat. Before it can get to the shelves of your local Rouses, though, it must first cool for an hour. It is then sliced, bagged and tied off.

Bread is everything in New Orleans, especially French bread — and with stale such bread being considered the best of all, because you can use it to make pain perdu. Po-boy bread can only be made in the city. (You could try to make it elsewhere, but it just wouldn’t work.) Even the traditional king cake is a kind of brioche — basically bread with a hint of sweetness, mixed with cinnamon and slathered in icing and colorful sugar.

So, if New Orleans prefers Bunny Bread, there has to be something going on there. In part it is the flavor and texture. It just goes right with Creole cuisine, and a big part of that is probably due to the water. Furthermore, it is perhaps because thousands of schoolkids — who probably had sandwiches made with Bunny Bread in their lunchboxes

— also took class field trips to the bakery in New Orleans, where they were probably given stickers of the Bunny logo.