FOR YOUR TRAINING TRIP?

FOR YOUR TRAINING TRIP?

NAVIGATING THE RISKS OF GETTING ON THE WATER—RESPONSIBLY

Supporting North American rowers since 1981

Official Boat Supplier of Rowing Canada U23 and U19 NextGen Teams

Canada, U23 M8+ // U8.32 2024 World Rowing Under 23 Championships

25 lbs.

(lightest 1x in production)

Why a light boat?

• Less drag, more speed

• Lighter feel, higher stroke rate

• Easier to carry

How did we do it?

Single skin - kevlar/carbon

No paint on deck

I-beam frame

The lightest fittings:

• Dreher/Peinert rigger - 4.3 lbs.

• Dreher seat - 15.5 oz.

• Carl Douglas tracks - 15 oz.

• Carbon footboard - 15 oz.

• H2Row shoes - 19 oz.

• Molded bow ball - 1 oz.

$9,950 incl. options

FEATURES

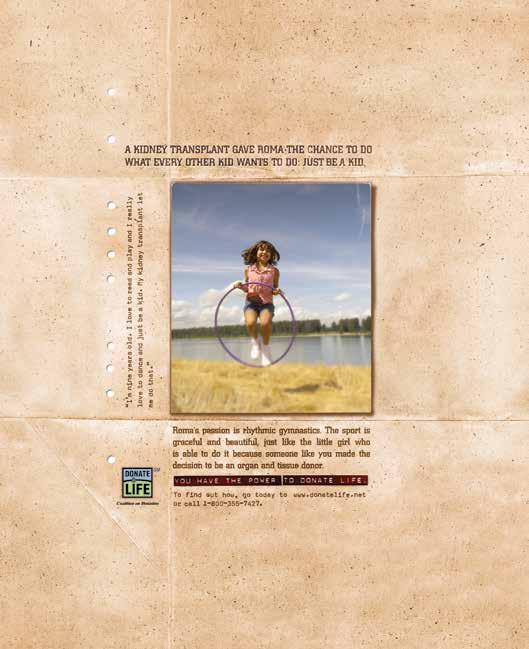

As rowers, we are mariners before we are athletes. Coaches bear responsibility for the safety of every individual who steps onto the water under their leadership.

BY TOM ROOKS

John Curran hasn’t let blindness and cancer stop him from rowing and urging others to join him. That includes racing in singles at big regattas. At 68, he’s not done yet.

BY EMILY WINSLOW

The new CEO of Rowing Canada Aviron is a high performer of high drive and high standards who’s willing to make the tough choices and lean into conflict.

BY CHIP DAVIS

DEPARTMENTS

USRowing’s Plan for LA2028

Xavier University’s New Program New Gladstone Documentary

Sports Science Training Through Transition Time

Coxing Getting Ready for Your Training Trip

Recruiting Help with Admissions?

Fuel The ABCs of Sports Nutrition

Training Work Load

Coach Development Finding Your Voice

CHIP DAVIS

The three attributes we rowers should aspire to as a sport and community are safety, fairness, and speed. Boat speed wins races. How to achieve that racewinning boat speed is the tricky part, one we spend all year trying to solve. Or, in the case of the pinnacle of boat speed, Olympic rowing, all four years.

For the 2024 Paris Olympics, U.S. head Olympic coach Josy Verdonkschot had less than three years, owing to the Covidcaused delay of the last Games, followed by USRowing’s slow hiring. And yet he was able to lead USRowing’s Olympic efforts back to the pinnacle for one event, the men’s four.

“Our sport is only as safe as any rower or coach’s next decision.”

–Tom Rooks

Now he’s got the full four years to plan and prepare for America’s first home Summer Games in more than 20 years, the 2028 Los Angeles Olympics. He spells out how he intends to do so in the 2025-2028 High Performance Plan, which I cover beginning on page 27. Spoiler alert: It’s underfunded. Meanwhile, in Canada—which won six medals at those last American Games in 1996—a new leader has been selected from one of the great crews of the glory days, Jeff Powell, stroke of the 2002 and 2003 world-champion men’s eights. Read the entertaining stories of how he came to be the new CEO of Rowing Canada in the Rowing News interview, beginning on page 46.

Fairness has many manifestations. Boats should start even at the beginning of a race. Coaches should give every member of the program a reasonable shot at making the first boat. But we should recognize also those who don’t have the same opportunities to row that we did, and do something to make access to our great sport more fair.

That’s exactly what the George Pocock Rowing Foundation, Hudson Boat Works, Concept2, and others are doing with the A Most Beautiful Thing Inclusion Fund. Read about their latest good work on page 34, and then read about Louisiana’s Xavier University, the latest college to add varsity rowing, partially as a result of that good work on page 32.

Safety is the most important attribute of our sport. No one should die rowing. And for the first time known to us, USRowing members achieved a zero-fatality year in 2024. As we report on page 27, USRowing’s recent emphasis on safety and safe practices coincides with this important accomplishment. Rowing News is proud to serve the rowing community with advice, beginning on page 36, about how to navigate the risks of rowing on cold water from USRowing Director of Safeguarding Tom Rooks, who also served in the United States Coast Guard.

“This progress shows our growing commitment to safety, but it’s up to all of us to maintain that momentum,” Rooks said. “Our sport is only as safe as any rower or coach’s next decision.”

$445 $495 AVAILABLE NOW!

Large Configurable Display (2, 4 and 6 fields)

Optional Wireless Impeller & Accessories

Easy Data Transfer via the DataFlow App

200m+ Transmission Range Pair with up to 5 units at the same time.

I enjoyed “The Magic of Rowing” (December) so much I feel the need to put my own oar in that water.

At age 78, I purchased a 1981 Alden ocean shell and, after learning how to get in and out of the shell without capsizing, embarked on what has become a 13-1/2-year rowing odyssey.

During those years, I have rowed a minimum of 2-1/2 miles a day, an average of 260 days a year, for a total of well over 8,000 miles.

Now in my 92nd year, I still go out every morning between 6 and 7, year-round, except for those few weeks in January and February when our lake is frozen over.

I believe daily rowing has added years to my life, and has certainly enriched my active life, which includes golfing two to three times a week, year-round.

Rowing has become such an essential part of my life that any day that doesn’t begin on the water just hasn’t started off quite right.

Don O’Neal Springfield, Ill.

USRowing has a responsibility to provide fair treatment and equal opportunity for girls and women. It is failing. USRowing will soon begin review of its “Gender Identity Policy” which permits males to compete against girls and women. Sex is the reason why the women’s sports category exists. Sex is genetic and immutable. Gender-transition treatment, including testosterone suppression, cannot make a male into a girl or woman and does not erase the male sports-performance advantage.

Current USRowing policy allows youth and adult rowers to compete in the gender category of their choice. They simply declare their gender at the start of each rowing season. When a man declares that he’s a woman, he can compete against women for that season. The next season, he can declare he is a man and resume competing against men. In rowing there are currently males who identify as girls and women competing at the high school and collegiate levels. Only in the mixed-boat category for master’s racing does USRowing’s eligibility criteria include sex of the athlete. In this category the athletes must be 50% assigned female at birth and 50% of any gender, protecting fairness for men. For collegiate and elite athletes, USRowing follows World Rowing rules which also provide opportunity for males to unfairly compete against women. These policies are harming girls and women in our sport.

We have consistently voiced our concern that USRowing is wrongly discriminating against its female athletes to Amanda Kraus, USRowing’s CEO, and the past and current chairs of the USRowing Board of Directors. Our position is based on science with 32 leading international sports medicine scientists calling for eligibility in the women’s category to be based on sex.

We urge the taskforce to recognize the women’s category is exclusively for female rowers. The Board of Directors must then adopt this corrected policy. We welcome all to our great sport and to compete fairly on the basis of their sex.

Please contact your USRowing board representative and demand USRowing restore fairness in competition for girls and women. Our female athletes deserve nothing less.

Mary I. O’Connor, M.D., Olympian

Carol Brown, Olympian

Jan Palchikoff, Olympian

Valerie McClain, Olympian

Anne Simpson, CA

Patricia Spratlen Etem, M.P.H., Olympian

ICONS Rowing Chapter

Please support ICONS, the Independent Council on Women’s Sports. Your donation to the ICONS female athlete legal fund enables us to defend women and girls in court and initiate lawsuits against institutions and organizations that wrongly discriminate against them.

ICONS is defending girls and women. Every sport, every level. Please donate at https://iconswomen.com/donate/ or use the QR code:

The U.S. mixed coxed quad competed at September’s 2024 World Rowing Coastal Championships and Beach Sprint Finals in Genoa, Italy. Beach Sprint rowing consists of rowers sprinting across a beach, jumping into boats, racing through waves in head-to-head races around buoys, and returning to the beach to sprint on foot and dive for the win by hitting a buzzer button first. The new category of rowing makes its Olympic debut at the 2028 Los Angeles Summer Games..

Cold-region rowers begin the annual migration from erg to water in spring, which can present safety concerns. “As rowers, we are mariners before we are athletes,” said USRowing Director of Safeguarding Tom Rooks. “Coaches bear responsibility for the safety of every individual who steps onto the water under their leadership.” His advice for navigating the risks of cold-water rowing appears on pages 36 to 41.

Rowing Canada Aviron, the national governing body for the sport, announced the selection of Jeff Powell as its new CEO. The women’s eight has been the bright spot of Canadian Olympic rowing, winning gold in Tokyo 2021 and silver in Paris 2024, while the men have been largely absent, failing to qualify a single athlete for the most recent Olympics.

“I know we’ve got our work cut out for us,” Powell said in the Rowing News interview beginning on page 46.

Olympic hopefuls moved to Sarasota in January to begin the quadrennial journey to the 2028 Los Angeles Summer Games.

Nathan Benderson Park will host a full spring season of regattas, beginning with the American Youth Cup, February 15 to 16, and culminating with the 30th anniversary USRowing Youth National Championships, June 12 to 15.

“Nathan Benderson Park is the ideal venue for Youth Nationals because of its state-of-the-art facilities that ensure safe and fair racing for all,” said Sarah McAuliffe, USRowing Director of Competition.

JANUARY 1–31

JANUARY REVOLUTIONS CHALLENGE

Choose your goal and set your New Year’s resolution.

JANUARY 1–31

VIRTUAL TEAM CHALLENGE

Team members row, ski or ride as many meters as they can.

MARCH 15–APRIL 15

WORLD ERG CHALLENGE

Team members row, ski or ride as many meters as they can.

APRIL 1–15

APRIL FOOLS’ CHALLENGE

Row, ski or ride an increasing distance each day.

JULY 9–13

BIKEERG WORLD SPRINTS

A worldwide virtual 1000 meter BikeErg race.

continued...

SEPTEMBER 15–OCTOBER 15

FALL TEAM CHALLENGE

Team members row, ski or ride as many meters as possible.

OCTOBER 25–31

SKELETON CREW CHALLENGE

Row, ski or ride a combined 31,000 meters.*

FEBRUARY 1–28

TOUR DE SKIERG

A different SkiErg event each week.

FEBRUARY 1–28

MILITARY CHALLENGE

Select your military affiliation and row, ski or ride as many meters as you can.

FEBRUARY 9–14

VALENTINE CHALLENGE

Row, ski or ride 14,000 meters.

MAY 1–15

MARATHON & CENTURY CHALLENGE

Row or ski a half (21,097 meters) or full (42,195 meters) marathon. Ride a half (50,000 meters) or full (100,000 meters) century ride.

MAY 1–31

MINDFUL MAY METERS CHALLENGE

Row, ski or ride to support mental health awareness.

AUGUST 1–28

DOG DAYS OF SUMMER

A different total distance goal each week for a total of 100,000 meters. On water and on snow meters allowed.*

NOVEMBER 6–9

SKIERG WORLD SPRINTS

A worldwide virtual 1000 meter SkiErg race.

NOVEMBER 27–DECEMBER 24

HOLIDAY CHALLENGE

Row, ski or ride at least 100,000 or 200,000 meters.*

MARCH 1–31

MUD SEASON MADNESS

Row, ski or ride 5000 meters or 10,000 meters per day for 25 days or more.*

MARCH 5–9

WORLD ROWING VIRTUAL INDOOR SPRINTS

A worldwide virtual 1000 meter RowErg race.

MARCH 8

INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S DAY

Row, ski or ride 5000 meters (10,000 on the BikeErg) to raise money for charity.

MARCH 15–APRIL 15

WORLD ERG CHALLENGE

Team members row, ski or ride as many meters as they can.

JUNE 19

JUNETEENTH CHALLENGE

Row, ski, or ride at least 1900 meters to raise money for racial justice organizations.

JUNE 20

SUMMER SOLSTICE CHALLENGE

Row, ski or ride a combined 21,000 meters in one day. On water and on snow meters allowed.

SEPTEMBER 1–7

WOD WEEK

Complete the Concept2 Workout of the Day on at least five days of WOD Week.

SEPTEMBER 15–OCTOBER 15

FALL TEAM CHALLENGE

Team members row, ski or ride as many meters as possible.

NOVEMBER 27–DECEMBER 24

HOLIDAY CHALLENGE

Row, ski or ride at least 100,000 or 200,000 meters.* continued...

USRowing’s plan for LA2028 calls for winning six medals—and projects a $17-million deficit. Unclear: Who will execute the plan? Where will the money come from?

USRowing aims to win at least six medals at the LA Olympics and Paralympics in 2028.

So declares High Performance Plan 2025-2028, in which the national governing body calls for three to four medals— including one gold—in classic flat-water rowing and one medal each in Beach Sprints and Paralympic rowing.

Missing from the 28-page plan is how USRowing will pay for its ambitions, which

are projected to result in a deficit for the Olympic quadrennial of $17 million—the target amount for USRowing’s fundraising.

“We’re proud and excited to roll out this high-performance plan for LA2028,” said Amanda Kraus, CEO of USRowing, who called it “a vision for an elite, sustainable program.”

“This roadmap provides a clear path forward for our athletes, coaches, supporters, and

USRowing members achieved zero rowing fatalities in 2024, reported Tom Rooks, USRowing’s Director of Member Safeguarding. The safety accomplishment comes after several years of multiple fatalities. While a direct connection can’t be proved, USRowing’s recent emphasis on safety and safe practices coincides with the first noted year of zero member rowing deaths.

fans,” she added.

Unclear is who will execute the plan. Four of the 13 positions in the staffstructure diagram are labeled “TBD,” with a fifth calling for “Independent Contractors.”

Chief High Performance Officer Josy Verdonkschot, the plan’s lead author, remains at the top, with full-time men’s and women’s head coaches Casey Galvanek and Jesse Foglia supported by operations staffers Will Daly and Wendy Wilbur.

The coaches of the West Coast training center and high-performance sculling and coastal rowing will be decided in 2025, and Brett Gorman, the director of HighPerformance Pathways, will get a talent coach in 2026, according to the document.

With fewer than a dozen athletes combined training full-time at the Mercer and Sarasota training centers at the end of last year, the U.S. National Team has yet to get started on the road to LA2028, America’s first home Summer Games since

Tokyo Games, the U.S. failed to win a single medal in any event.

From 2007 through 2016, the U.S. women’s eight won every World Rowing Cup, World Rowing Championship, and Olympics they raced. But since 2019, USRowing hasn’t won gold in a single event of the 29 contested at every regular senior World Rowing Championships. If U.S. rowers can achieve the LA2028 goal of four Olympic medals, they will equal the 1996 Atlanta record, and exceed it by winning gold.

Much of the plan is about continuing to build on the system installed by Verdonkschot leading up to Paris 2024. Larger permanent facilities have been envisioned for years at the training centers in Sarasota and at Mercer Lake in West Windsor, N.J., but construction has yet to begin.

USRowing lags behind the support leading Olympic nations provide.

Atlanta 1996, when U.S. crews won four medals.

With the elimination of lightweight events and the addition of Beach Sprints, current plans call for 12 traditional flatwater rowing events (now termed “classic” by World Rowing) on the shortened 1,500-meter Long Beach course and three Beach Sprint events at a venue yet to be named.

In March, the international governing bodies of rowing will gather for World Rowing’s 2025 Quadrennial Congress in Lausanne, where more events are expected to be eliminated from the World Rowing Championships and more changes made to the Olympic program.

At the Paris 2024 Games, three countries—The Netherlands, Great Britain, and Romania—won nine of the 14 events. U.S. men did well in big-boat sweep rowing, winning gold in the four and bronze in the eight. But U.S. women and scullers were shut out of the medals for the second consecutive Olympics; at the preceding

Paralympic rowers train part-time in Boston from existing boathouses, including Community Rowing’s Harry Parker Boathouse under six-year Para head coach Ellen Minzner. The USRowing plan calls Chula Vista “ideal” for a West Coast training center and states that making a final decision and starting work on the new center this year is “a priority.”

Verdonkschot’s program relies heavily on clubs like California Rowing Club to serve as the training homes of athletes when they’re not on trips or at U.S. National Team camps. Three of the four gold medalists from the Paris four trained at CRC, as did most of the bronze-medal eight, which prepared in Seattle under Washington coach Michael Callahan for the last-chance Olympic qualifier in Lucerne two months before the Games.

In the lead-up to Paris, Verdonkschot worked cooperatively and successfully with clubs such as ARION, Craftsbury Green Racing Project, and New York Athletic Club, and the USRowing plan advocates continuing to use this “hybrid structure.”

Much of the unmet cost of the plan comes from athlete stipends, which reached $1 million dollars in 2024. For the LA2028 quadrennial, Verdonkschot’s proposal retains the previous training stipend of $1,000 per month and adds a higher

“performance” stipend of $2,500 per month for 2025, which increases to $3,000 in 2026 and $3,500 in 2027 and 2028.

Aligning Olympic and Paralympic stipends, and projecting the same relative number of recipients, the cost of athlete stipends will rise to over $1.5 million dollars in 2027 and 2028, the plan estimates.

“It’s not a fundraising document,” said Verdonkschot. “But you can’t write a plan without considering budget implications. And then just do the math.”

Even with the proposed increased spending for Olympic preparation, USRowing lags behind the support leading Olympic nations Great Britain and The Netherlands provide their Olympic and Paralympic athletes.

Reported figures of $30 million and $5 million for Great Britain’s Olympic and Paralympic rowers, respectively, don’t tell the whole story, since British athletes, like most of Team USA’s competitors, benefit from government health-care funding, as well as existing training centers and lower travel costs to training and racing venues.

Verdonkschot and his fellow coaches are behind their international peers also in compensation. Earlier this century, when the U.S. women were on their historic winning streak and the men’s eight won gold in 2004 in Athens and bronze in 2008 in Beijing, both the women’s head coach, Tom Terhaar, and men’s head coach, Mike Teti, each were paid more than USRowing’s then CEO, Glenn Merry. In 2015, all of the top-five highest-paid non-officer employees of USRowing had coaching roles, and three of the coaches were paid more than the CEO.

That’s been reversed. USRowing’s 2023 tax returns (the most recent available) show that Verdonkschot was paid $227,191 and CEO Amanda Kraus $289,224. Of the other five highest-paid USRowing employees in 2023, none had a coaching role.

USRowing supplemented the grants made by the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee by $300,000 in 2024 and intends to more than double that additional annual support for Olympic hopefuls in the run-up to LA2028, the plan says.

Where that money will come from remains to be seen.

CHIP DAVIS

The governing body’s new certification requirement for member coaches, which has sparked confusion, resistance, and resentment, was a factor driving the departures.

The American Collegiate Rowing Association (ACRA) and Southern Intercollegiate Rowing Association (SIRA) became the latest organizations to leave USRowing last month in response to new and poorly communicated requirements from the national governing body.

“After receiving a reasonably priced comprehensive insurance quote for the ACRA regatta, the board made the decision to not be a USRowing-sanctioned regatta for the 2025 ACRA National Championship,” said ACRA president Dan Wollenben in a message to members. “The ACRA will not require programs to carry USRowing organizational membership or individual USRowing membership to participate.”

Last year’s ACRA regatta featured 1,960 college club rowers from 76 clubs racing in 23 events.

The SIRA board of directors sent a similar message to members.

“The SIRA board, following an extensive review for the SIRA Championship Regatta, made the decision not to be a USRowing-sanctioned/registered regatta for 2025. The board procured a competitively priced comprehensive insurance quote for the SIRA Regatta that

meets and exceeds the coverage we have had in the past as a USRowing-sanctioned/ registered event.”

Both organizations reminded members that while their regattas will not require USRowing membership for participating teams or individuals, programs should ensure they have appropriate insurance for the rest of the year.

USRowing’s requirement, announced in an email in June, that every individual coaching at a member organization or at a USRowing-registered regatta have USRowing Level I certification, at a cost of $99 per coach, was a factor in the ACRA and SIRA decisions, people involved said.

“While SIRA supports the rising standards of safety and coaching education recommended by USRowing, teams will not be required to adhere to the USRowing coaching certifications as the SIRA Regatta is not a USRowing-sanctioned/registered regatta,” the SIRA statement said.

The 2025 SIRA Championship Regatta will be held Friday and Saturday, April 18 and 19, on Melton Hill Lake, in Oak Ridge, Tenn., followed by the ACRA club national championships, May 16 to 18, also in Oak Ridge.

The names of Olympic coach Michelle Darville and Hudson Boat Works co-owner Glenn Burston will be inscribed on the Rowing Wall of Excellence by Western University in London, Ontario. Darville coached within the Western Rowing program during the early 90’s and again through the early 2000’s while rowing and then coaching on the Canadian National Team. She coached the Canadian women’s eight to Olympic gold in Tokyo before moving

to The Netherlands to coach Dutch women to four medals in Paris. Racing for Western, Burston won the 1992 Dad Vail lightweight eight by 11 seconds and rowed on the Canadian National Team. He was one of the first presidents of the Mustang Old Oars Club, the Western University Rowing Program’s alumni chapter, and is a principal owner of Hudson Boat Works, overseeing the growth of the company with his former teammate, Craig McAllister, and fellow Western rower, the late Jon Beare

Legendary rowing coach Steve Gladstone, who is still coaching at age 83, is the subject of Full Measure, a new documentary by director Jean Strauss, Strauss, who rowed in the 1970s at Cal, where Gladstone coached from 1973 to 1980 (and again from 1997 to 2008), made the film because she believes Gladstone’s career deserves to be chronicled.

The 80-minute documentary, which debuted at California’s Orinda Theater in December, tells the story of Gladstone’s growing up on the East Coast, where he rowed at the Kent School and Syracuse University, before beginning his remarkable coaching career at Princeton.

After producing championship crews at Harvard, Brown, Cal, and Yale, Gladstone moved to the U.S. Naval Academy last fall to coach the midshipmen.

The documentary will be available on a streaming service later this year.

COLLEGE

Xavier University of Louisiana will hire its first head coach of men’s and women’s rowing as the co-ed club team goes varsity in the fall.

Xavier University of Louisiana will hire its first-ever head coach of men’s and women’s varsity rowing as it elevates the current co-ed team from club to varsity status next fall.

With this move, Xavier becomes the nation’s first and only historically Black college or university (HBCU) to offer co-ed varsity rowing.

Elizabeth Manley, a professor of history and a member of the New Orleans Rowing Club (NORC), is one of several dedicated individuals who helped the club team go from an idea to reality.

“Around 2020, there was a lot of conversation about who rows and who has access to rowing,” Manley said. “I started thinking about how I have this position at Xavier, and as an HBCU, Xavier is limited in resources. There’s not a lot of space for club sports, but last fall we started a club program with the help of NORC.”

The team operated initially like an extended learn-to-row program and attracted an active group of engaged students, many of whom were introduced to

rowing in college. With the benefit of many supporters, it began gaining attention from the university’s administration, which was already planning to expand current sports offerings.

“By the time we began having these conversations with them, there was already a club in place, and we had more than a dozen students who were getting into the sport,” Manley said. “The administration decided last spring that they were going to add rowing as a varsity sport, so it’s a program that will be built mostly from the ground up.”

Besides carrying out the usual tasks of a college rowing coach, the prospective candidate will be expected to launch the team, gain interest from students and community members, and recruit extensively, especially during the transition to varsity.

“The coach should be someone who is a typical head coach and also a pioneer capable of building the first coed HBCU program in the country,” Manley said. “Howard University had a program in the

late ’60s for men only. Saint Augustine’s University started a women’s-only program. This will be the first co-ed program.”

Xavier will compete in the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics and do much of its racing in Texas, Oklahoma, Florida, and Georgia, in addition to competing at ACRA and SIRA events.

“As we try to change the way rowing looks, a lot of these amazing efforts are happening at the middle-school and highschool level. We need to make it clear to these rowers that there are spaces within the collegiate landscape for them.

“I’ve talked to Arshay Cooper (author of A Most Beautiful Thing ), and he has seen a lot of rowers who are no longer rowing because it’s important to them to go to an HBCU.

“This is an opportunity for them not to have to make that choice, and it’s also a larger statement that there’s a real commitment to opening up different kinds of spaces for potential rowers from all points in a rowing career.”

New Haven Rowing Club invites you to join us for fast racing, a fun, family atmosphere, and perfect fall foliage at the completely reimagined, two-day Head of the Housatonic Regatta!

• Dedicated racing days for colleges and masters (Saturday) and for juniors (Sunday)

• More novice junior events: 4+, 4x, 2x, and 1x

• No event caps

• More opportunities to race twice

It’s the Head of the Housatonic you love, only better. Mark your fall schedule for October 11-12 in Shelton, Connecticut. Check out RegattaCentral for more information!

Since 2019, gifts of boats, oars, and ergs have ensured that enthusiastic rowers—regardless of background or income status— are beginning from the same starting line.

Hudson Boat Works will deliver 17 shells valued at $335,000 to eight programs in 2025 through the A Most Beautiful Thing Inclusion Fund.

Since 2019, Hudson and Concept2 have enabled the fund, inspired by Arshay Cooper’s eponymous book and under the umbrella of the George Pocock Rowing Foundation, to provide top-of-the-line equipment to rowing programs that are at the forefront of creating diversity and inclusion within the rowing community. Dozens of ergs and oars, as well as previously donated boats, have ensured that enthusiastic rowers—regardless of background or income status—are beginning from the same starting line.

“Hudson is honored to be part of the AMBTIF movement and to see that these programs serving historically neglected communities now have no barriers to world-class equipment,” said Olympian Dan Walsh, Hudson’s Northeast sales manager. “To see how fast this movement is growing, both on and off the water, is nothing short of amazing. We are excited to be part of Arshay’s vision, now and in the future.”

The eight programs receiving Hudson shells in 2025 are Atlantic City High School, Dallas United Crew, DeMatha Catholic High School, Evanston High School, Hackensack High School, Newport Rowing Club, Riversport OKC, and Xavier University.

The January issue of the Princeton Alumni Weekly set out to start arguments—and succeeded—with a cover story ranking the 25 greatest Tiger athletes of all time.

Besides such obvious greats as Bill Bradley ’65 (basketball), Hobey Baker 1914 (ice hockey), and Dick Kazmaier ’52 (football), the list includes four rowers. As ranked among the 25 and described by the magazine:

No. 5: Caroline Lind ’06

In 2006, Lind anchored a women’s eight that won a national championship [first varsity eight] for Princeton, winning all its races by more than 6.4 seconds. She won gold medals in the women’s eight at the 2008 and 2012 Olympics, as well as six world championships. Lind and her 2008 Olympic boatmates were inducted into the National Rowing Hall of Fame.

No. 6: Carol Brown ’75

Brown starred on Princeton’s women’s rowing team for three years. A member of three Olympic rowing teams, Brown won a bronze medal in 1976. She was inducted into the National Rowing Hall of Fame.

No. 10: Chris Ahrens ’98

Ahrens represented the U.S. in the 2000 and 2004 Olympics, winning a gold medal in the latter. He claimed world championship gold medals in 1995, ’97, ’98, and ’99. At Princeton, Ahrens was on the men’s heavyweight-eight teams that won the IRA championship in 1996 and ’98.

No. 22: Anne Marden ’81

After rowing for four years on Princeton’s varsity eight, Marden switched to sculling and won two Olympic silver medals for the U.S. (quadruple sculls in 1984, single sculls in 1988). She also competed in the 1992 Olympics and, if not for the 1980 U.S. boycott, would have been Princeton’s first four-time Olympian.

Discover our new website:

• intuitive navigation,

• mobile friendly,

• packed with features to connect LGBTQ+ rowers.

Join our global community in just a few clicks!

• Help us build a more inclusive future for rowing.

WHO STEPS ONTO THE WATER UNDER THEIR LEADERSHIP.

In November, the water was cold in Bellingham Bay, Washington.

Lanny “Bip” Sokol was a 48-year-old emergency-room doctor, Ironman triathlete, cross-country skier, and experienced surf-ski kayaker. He was also a devoted husband and father of two young sons.

Sokol set out for an evening paddle with a fellow accomplished kayaker, prepared with a headlamp for nightfall. Conditions were mild, with winds of five to 10 m.p.h., but the wind shifted unexpectedly, and water conditions worsened.

As the wind intensified, they turned back. Sokol capsized, and his kayak was swept away. Despite wearing a dry suit and life vest, he couldn’t overcome the tide and wind to reach the shore. His friend tried to help but after several failed attempts left to seek assistance.

After a massive search effort, including two Coast Guard motor lifeboats, two rescue boats from other agencies, two search aircraft, and a large shoreline search party, Sokol was found unresponsive three hours later.

As rowers, we are mariners before we are athletes. Coaches bear responsibility for the safety of every individual who steps onto the water under their leadership. Our community is passionate, often volunteering countless hours to the sport, but this dedication can lead sometimes to tunnel vision, where performance goals overshadow essential safety considerations. Cold water increases the risks exponentially, and recognizing those dangers is crucial for every rowing program.

The National Center for Cold Water Safety and the National Weather Service caution that water temperatures below 60 degrees F. are dangerous, with risks increasing as temperatures drop. The sequence of cold-water shock includes:

· Gasp Reflex: Sudden immersion can trigger an involuntary gasp, causing immediate drowning if underwater.

· Breathing Difficulties: Hyperventilation, lasting one to five minutes, makes basic movements challenging.

· Cardiovascular Stress: Elevated pulse and blood pressure can lead to exhaustion and impaired motor skills.

· Hypothermia : Prolonged exposure cools the body rapidly, leading to confusion, loss of motor control, and unconsciousness. Panic can intensify each of these stages, making survival even harder.

USRowing used to recommend, and many teams and clubs follow, a combined air and water temperature of 90 degrees F. for safe rowing, with some clubs adopting a 100-degree rule. These standards can be a decent starting point for assessing coldtemperature risk, but they fail to account for the much greater risk of cold water versus cold air. Rowing in 65-degree air with 35-degree water is far riskier than 35-degree air with 65-degree water.

In addition, safety decisions must factor in more than just temperature:

Shell Type: Are larger, more stable boats being used?

Weather: Are wind, rain, or snow in the forecast?

Current Conditions: Is the current manageable?

Experience and Skill: Are rowers prepared for cold weather and water?

Safety Drills: Has the crew practiced coldwater emergency procedures?

Protective Gear: Do coxswains have anti-exposure gear? Are rowers equipped with waterproof layers, pogies, and warm headgear?

Other Watercraft: Are there other boats that could pose a wake or capsize risk?

To mitigate cold-water risks, consider these safety strategies:

Use Stable Boats: Larger boats with more oars provide better balance.

Match Experience to Conditions: Assign crews based on skill levels.

Keep Moving: Avoid long pauses to prevent chilling.

Stay Near Shore: Loop near safe exit points rather than venturing far.

Limit Pauses at the Catch: Minimize drills that increase capsize risks.

Set Clear Cutoffs: Establish and respect conditions that warrant ending practice.

Monitor Coxswains: They’re especially vulnerable to hypothermia.

Carry Safety Gear: Use life jackets and consider wearing waist-pack inflatables when rowing without a coach.

Stay Calm: Avoid panic; control your breathing.

Stay Afloat: Use or put on a life jacket if available.

Plan Your Actions: Visualize and communicate your next steps.

Limit Attempts to Re-board: Set a limit for re-boarding attempts; otherwise, get on top of the boat or wait for rescue.

Call for Help: Use a VHF radio or phone to summon assistance immediately.

As a Coast Guard cutter swimmer and boat coxswain, I worked in search and rescue in Washington, Alaska, and Maine. The priorities of cold-water immersion response are the same as they are for a rower and coach: slow down, stay calm, regain control over breathing and heart rate, make a plan before trying to execute it, and call for help early.

The night Sokol died was the most devastating of my 22 years in search and rescue. I was the command duty officer coordinating the response when our crew recovered him. Hearing “Chief, we’ve recovered the victim; there are no signs of life” over the radio, with his wife standing in front of me, was heartbreaking. Despite a small search area, expert rescuers, and his wearing the best safety gear, we couldn’t save him. He’d been in water that was too cold for too long. I vowed never to underestimate the risk of boating on cold water again.

In 2017, the rowing community lost three athletes to cold-water accidents in just two months. Last year, no USRowing members died while rowing. This progress shows our growing commitment to safety, but it’s up to all of us to maintain that momentum.

Our sport is only as safe as any rower or coach’s next decision. Each of those decisions, and the standards we follow, even when inconvenient to other goals, can be the difference between a safe practice and a tragedy. Let’s continue to make safety our first priority. TOM ROOKS

JOHN CURRAN HASN’T LET BLINDNESS AND CANCER STOP HIM FROM ROWING AND URGING OTHERS TO JOIN HIM. THAT INCLUDES RACING IN SINGLES AT BIG REGATTAS. AT 68, HE’S NOT DONE YET.

Your eyesight is like a big crayon box. I lost a lot of the crayons without even noticing because I lost my peripheral vision first. When I found out what I had, it was almost all gone.”

John Curran, who didn’t set foot in a boat or pick up an oar until after a retinitis pigmentosa diagnosis in 2002, not only learned to row with complete vision loss but also became skillful enough to race in a single at one of the premier fall regattas, the Head of the Schuylkill.

Curran’s passion for rowing, his desire to share it with others—especially those with disabilities—and his compassion, selflessness, and generosity have made him a prized and beloved member of the rowing community in Philadelphia.

Retinitis pigmentosa, which afflicted one of Curran’s sisters as well, is a rare genetic condition that affects the retina and can cause blindness. Curran, 68, began experiencing symptoms when he was in his 40s, and his eyesight became progressively worse. He had held various jobs—outpatient billing, a moving company, supermarket night crew—but his failing vision prevented him eventually from working.

He began rowing 20 years ago when, while training to use a cane, he was told about the Pennsylvania Center for Adaptive Sports, which is headquartered on Boathouse Row and is dedicated to improving the health and well-being of people with disabilities through inclusive sport and recreation programs.

Curran was handed an activity list and among such sports as cycling, skiing, and kayaking, he spotted rowing. The first time he rowed on an erg, he was on the machine for only five minutes when a coach noticed his strength and was convinced he was an experienced oarsman.

Curran went out on the water that very same day and received instruction from a coach with the U.S. National Para team. He continues to surprise rowers and coaches with his strength and power.

“I had always been a weightlifter, and I was in pretty good shape,” Curran said, “so I wanted to compete against the best.”

Curran races in a single currently with the assistance of a guide either in a scull next

to him or a launch following him. Through a Bluetooth speaker, the guide gives him directions, just as a coxswain would.

Curran is active in the Philadelphia rowing community. At Whitemarsh Boat Club, where he serves on the board, coaches and members alike praise him for his involvement, his efforts to get others passionate about the sport, and his determination on the water.

“He’s done pretty well getting in the single and hammering away at it,” said Whitemarsh coach Sean Hall. “He’s a wellrespected member of the club, and people take his opinions quite seriously. His back story is the stuff of Boys in the Boat.”

Curran appreciates the camaraderie and the support he receives from friends and fellow club members, such as rower Ed Fox, who demonstrated his admiration by contacting Rowing News and sharing Curran’s remarkable story.

A major beneficiary of Curran’s involvement at Whitemarsh is the annual Pumpkin Regatta, when junior and masters rowers race in Halloween costumes.

“I met Laura Olah after the Pumpkin Regatta one year,” Curran said, “and she said her son Lev was at the Pennsylvania Center for Adaptive Sports but too young to row. She told me he had a brain tumor and was losing his eyesight.

“I told her if she ever needed anyone to row with him, just look me up and I’ll find somebody.”

When Curran got home, he called the Whitemarsh president and suggested that the club invite the family to the Pumpkin Regatta. He also asked the coach of the high-school program to get the kids together to cheer for him.

“It was like a Hallmark movie,” Curran recalled. “I wanted to make it neat not only for him but also for the parents. I got two different kinds of medals and let him pick.”

“Lev is not on a crew and wouldn’t otherwise compete in this friendly regatta,” Laura Olah said. “However, John cooked up a plan to start the regatta with Lev and another athlete taking on two established rowers in a double.

“Nothing has made Lev so excited. He

shared that he would be competing with every teacher, every family member, and even people in line at the grocery. Little did any of us know that John even brought medals for Lev to ‘win’ when they drove across the finish line—first, of course, because John contrived that as well.

“That day is one of the most memorable days for Lev, and it was all created by another person living with a disability knowing how much it matters to give the gift of strength and optimism.”

Lev’s rowing journey is one of many that Curran has helped launch and nurture. He has done so cheerfully despite not only dealing with blindness but also battling leukemia, which was diagnosed in 2016.

Last fall was the first time Curran has been cancer-free in nine years.

“John reached out shortly after the 2024 Pumpkin Regatta,” Laura Olah recalled. “He was checking in on Lev because we were absent [beginning treatment in Boston for Lev’s brain tumor]. This time, John offered to support Lev’s interest in the 2025 BAYADA Regatta.” Sponsored by the home health-care company, it takes place on the Schuylkill and bills itself as the world’s first Para rowing event.

“He sent details and offered to help with networking and anything needed to get Lev more support in the rowing community. John is that person always pushing and pulling to connect rowers, to foster their competitive spirit, and to encourage their determination and will over all odds.

“He’s very open about his own challenges. He repositioned my grief into something more powerful. I was more committed than ever to not allowing medical challenges to overcome Lev’s personal determination— with any sport, and anything in life.”

After Curran’s cancer diagnosis, his doctor cautioned that the disease would make him feel fatigued. When Curran informed him he rows five days a week, the doctor was speechless.

While Curran sometimes must cut back the number of days he makes it down

“Sometimes I feel like an ambassador for disabled people, letting people know we’re no different from anybody else. It’s just getting the opportunity.”

—

John Curran

to the boathouse, his leukemia has not kept him from the sport he loves.

“Last summer, I was going through leukemia treatments and rowing one day a week trying to stay somewhat in shape,” Curran said. “When I wasn’t feeling so good, I figured I wasn’t going to be feeling that good anyway, so I might as well try to train. May through August, it was pretty rough. I just went out with some people who didn’t mind if I wasn’t killing it.”

Curran’s last treatment was Sept. 17. Less than two weeks later, on Sept. 29, he participated in the King’s Head Regatta on the upper Schuylkill, racing in a mixed quad. His admonition to his boatmates: “I’m not really in shape, so keep the stroke rate down.”

“John never complains about anything, and it puts things in perspective,” said Whitemarsh coach Art Post. “It’s a constant reminder that the joy of rowing overrides all our little complaints. If he’s cold, he doesn’t say so. If he’s getting splashed a little bit, he’ll joke about it. We have a boat at the club named after him: Strong Curran. In spite of his limitations, he’s a pillar of strength.”

While Curran’s resume in team boats is impressive, more remarkable is his racing in a single at such events as the Head of the Schuylkill and the King’s Head Regatta.

“Being blind and going out to row a single is pretty neat,” Curran said. “It’s like when you let a bird out to clean the cage and you can’t contain it—that’s me on the water.

“Maybe somebody sees me doing this and is encouraged. I met a girl rowing for Lower Merion, and she told me, ‘I’m rowing two-seat, same as you.’ I talked her into going to the disabled club to learn how to scull.

“Sometimes I feel like an ambassador for disabled people, letting people know we’re no different from anybody else. It’s just getting the opportunity.”

Curran has rowed the Head of the Schuylkill twice, once in a masters single and once in an open recreational single.

“It was storm conditions,” Curran recalled. “The regatta was worried because the next race was an elite race—Mahe Drysdale and those guys. They were afraid the launch guiding me would affect their race. My guide assured them we would be out of the way. I was on the water when they came by. They sounded like race cars.”

Every time Curran races in the single, he’s excited by the challenge. Navigating the Schuylkill, the Twin Bridges, the Girard Avenue Bridge, and Boathouse Row in a single is no easy feat—even for someone with perfect vision.

Racing in a single, Curran has won the BAYADA Regatta six times.

“They told me that I couldn’t do the BAYADA because they banned blind single rowers on the Schuylkill. I was like the dog that gets out of the yard all the time. I talked a couple of other blind rowers into doing it, and the race had to buy more headsets.

“The last year I did it, there were 10 men and 10 women [racing singles],” Curran said. “It became the race to do, and they thanked me for keeping the race alive.”

Curran’s determination and demonstrated ability have not gone unnoticed by coaches, athletes, and regatta directors. After he won permission to race the BAYADA and Head of the Schuylkill, races in and around Philadelphia expanded the Para and blind-rowing categories to allow more entrants.

His latest ambition: to race in a single at the Head of the Charles.

“I was in one of the first groups of disabled rowers to do The Charles in mixed fours,” Curran said. “Now they have a bunch of different races. It’s really come a long way.

“Every time someone says, ‘You can’t do this,’ I try to get it done. At the Charles, where there’s no singles race for blind people, they asked me, ‘Why don’t you row a double like everybody else?’ I don’t want to do what everybody else does.

“It’s been fun, a pretty wild adventure. Somebody offered to write my story, and I said, ‘It’s not done yet.’”

EMILY WINSLOW works in athletic communications at Salve Regina University in Newport, R.I. She captained the women’s rowing team at the University of Rhode Island, where she also coached, when the team won multiple Atlantic 10 championships and advanced to the NCAA DI championships.

THE NEW CEO OF ROWING CANADA AVIRON IS A HIGH PERFORMER OF HIGH DRIVE AND HIGH STANDARDS WHO’S WILLING TO MAKE THE TOUGH CHOICES AND LEAN INTO CONFLICT.

Rowing Canada Aviron, the national governing body of the sport, named Olympian and two-time world champion Jeff Powell as the next CEO this winter.

The 48-year-old native and resident of Winnipeg assumes the role this month as the organization casts a rescue net under a once-proud rowing program that won four gold medals at the 1992 Olympics, including in both the men’s and women’s eights, and another six medals at the 1996 Games.

Recently, not so much. Canada failed to qualify a men’s crew for the Paris Olympics and hasn’t raced a men’s eight in the Olympics since 2012. The women’s eight won silver in Paris, and the women’s lightweight double—the only other Canadian crew to qualify—finished eighth. Jacob Wassermann was Canada’s lone Paralympic competitor in Paris.

“Re-establishing Canada in a position where we believe it ought to be is without question a priority of the organization,” Powell said.

“He’s a man of high drive, high standards, and very confident in implementing his ideas,” said Adam Kreek, remembering his teammate of 20 years ago. “He will piss off many people, and this is exactly what the organization needs. He has the hard edge of a high performer and is willing to lean into conflict.”

Powell returns to rowing from the Canadian Sport Centre Manitoba, where he was CEO. He replaces Terry Dillon, who resigned June 30, and succeeds interim CEO Jennifer Fitzpatrick, who will be returning to her role as Director of Partnerships and Sport Development.

Rowing News: How did you get your start in rowing?

I played basketball all through high school and thought I was going to be a university basketball player. Then I went on an exchange program for a year to Japan and I came back and I wasn’t that good at basketball anymore. So I was kicking around looking for a new sport in 1996, the summer of the Atlanta Olympics.

Canada did very well in rowing in those Games, and so I and probably 50 other university-age kids were showing up at the tarmac of the Winnipeg Rowing Club at 5:30 every morning the rest of that fall. It was a great social group, with outstanding parties, and I just kind of stuck with it from there, never intending

that it should reach the levels it did.

Rowing News: But it reached the highest level. You stroked the 2002 and 2003 world-champion Canadian men’s eight and competed in the 2004 Olympics. What led you to pursue elite-level rowing?

Well, I got into it. I don’t want to underweight the value of a great social group—it was just a great time and place to be rowing. We had a good coach. We had a good time, and some of the performances began to follow. It just seems like it built on itself pretty naturally.

I had some modest success on the North American circuit—the old Canada Cup that we used to have in Montreal the week after [Canadian] Henley, which was an interprovincial event. I won a few medals there and mistakenly had it in my head that I was therefore qualified to join the national training center.

I went out there, was last at everything for about six months before I got very lucky; I got to spend about three days with Kevin Light, who showed me what was required. Things really took off from there, but it was a little bit the same thing—we had a great group of guys with a great coach all dedicated to the same task and had some success with the results.

Rowing News: Tell us the story about flipping in the single. How did that get to you?

Oh man. I got up to Victoria, I was last at everything, right? Of course, no one’s coaching me and no one’s paying any attention to this guy who can barely keep up. So one day, Terry Paul and Sarah Pape took pity on me and said, “We’ll work with Powell over here.”

So he pulled me over to the side and wanted to fix my catch position. He gets me sitting there. I need to reach a little farther. I need a little longer arms and I’m inching up the slide. He says, “Right, you’re good there. I want you to take a stroke now.”

So I begin to take the stroke, but over the course of all this adjusting and moving, one of my blades has come off the square and I start rowing and it just pulls me right over, and I get partway through this roll and I can remember thinking, “This isn’t good.”

I roll over and I hit the water and it’s March in Victoria, the water is six degrees or something and blasts all the air out of

me. I come up for air. I’m sputtering like a drowned rat, gasping, dog-paddle over to his Zodiac coach boat, and he looks at me, deadpan, and he’s like, “That didn’t go very well for you, did it?”

That was the first ever national-team coaching I got.

Rowing News: How do you go from flipping the single to the stroke seat of the best eight in the world?

I can’t tell you how important Kevin was in that journey. He and Joe Stankevicius, who also rowed in that eight, rowed in a pair and they were very good. Joe picked up a minor injury and sat out probably three rows—it wasn’t very long.

Kevin was looking around for a partner, “Well, I guess Powell’s here, I’ll row with him.” He could’ve taken those rows off. If we’d been slow, no one would’ve thought it was him. And I had never imagined that someone could pull as hard as he pulled when we were out there together.

You remember Mike [Spracklen] was all about the competitive work, right? We weren’t just paddling. I still have the journal I was keeping at the time: “I don’t know if I can do that, but it’s probably what I need to try to do if I want to have a go with this.”

Kevin was this model of honest, incredibly hard work, so why don’t I do that? And then I remember thinking, “I can’t do this, but I can probably do it for the first 100 meters of the first piece on Monday morning,” and then the next week I’ll try to lead to the first buoy on Elk Lake. It built from there, but it was a pretty humble beginning, to be sure.

Rowing News: Tell us about your coaching.

I retired [from elite rowing] and felt like I needed to start a real job, you know, suit-and-tie, nine to five. Turns out that some of those can be a touch on the soul-sucking side. I always had dabbled in coaching, and we ended up starting a real small high-performance program here at the club, and I had maybe five athletes in that group, three of whom ended up rowing for Canada in one capacity or another. I was doing that part-time, and eventually my wife said, “Listen, you’re working full-time at this ‘volunteer’ coaching job. You need to make a bit of a call here, buddy.”

There was an assistant-coach position at the training center in London, and I

was lucky enough to get in there and had a great quadrennial working with John Keough and Michelle Darville, a brilliant coach who has just come off the success with the Dutch Olympic program [after coaching the Canadian women’s eight to gold in Tokyo].

We ended up taking a development eight over to Europe for a bit of a tour. We rowed the Holland Becker and then we actually beat the German Olympic eight at Henley that year to win the Remenham [Challenge Cup, for top women’s eights].

I know a lot of this is in and around high performance, but I coached best the year after that when I came back to Winnipeg and got a “real job” again and ended up coaching a group of masters, and the lesson I learned was about the efficiency of their coaching.

I’m seeing these guys once or twice a week, and if it took me four sessions to get something across, that’s half the month. That artificial restriction on my time with the athletes was probably the top of my coaching. It was incredibly rewarding for me. It’s not the case that the national-team stuff was the best I ever did.

Rowing News: Why are you taking the CEO job?

There are a couple of factors. Obviously, the organization and the sport have been very, very good to me. It means a great deal to me. It’s near and dear to my heart.

The second is I’ve been in my role here [Canadian Sport Centre Manitoba] for about 10 years now, and it’s probably time both for the organization and for me to

look at different opportunities. I’ve moved this organization forward, and it’s for the next person to take it on its journey. And moving into a bigger organization— with a little more scope and different challenges—is a great development opportunity for me professionally.

The final thing is we’re empty nesters. Both of our girls have moved out to pursue their passions, so the time and energy are there to be able to dive in and give all of myself to a cause like this. A lot of things came together.

Rowing News: Are you planning any sort of revival of the rivalry with the USA?

There is certainly no grand plan to force a rivalry, and I don’t want to give the impression that there is. Both eights were great and I relished every bit of it. I am well aware that they got us in the race that mattered in Athens, but another story:

We went over to Henley in 2003 and we raced Mike Teti’s U.S. eight in the final. We put in a big start, got out ahead, and won pretty handily, to be totally honest.

Kreek and I are walking through the boat tent afterward, and Mike walks across and recognizes us. He comes over and sticks out his hand, and says, “You know, boys, just wanna say that was a real shit-kicking out there today.”

So that’s my memory of that rivalry, and it was great. That was a brilliant time for both countries in the big boats, and I would love, love, love to see it again. I know we’ve got our work cut out for us at home, so we’ll start getting our own house in order and move forward and go from there.

Rowing News: What do you want the North American rowing community to know about Rowing Canada and Jeff Powell?

I appreciate that the interest often is in the national-team stuff and high performance in the big competitions. I do have a lens now, particularly through one of my daughters, with more of the club-level coaching, around what it is to drive sport development, growth in sport, and build passionate members of the community.

The most basic unit of sport is the quality and frequency of the interactions with it. Whether it’s for my daughter or in my role as a volunteer club coach right now, whatever it is, in everything I do, I try to operate through the lens of “Does this increase either the frequency or the quality, or both, of the interactions that people are having with rowing?” That is critical to how we build sport systems.

The other piece—and this is a broad philosophical discussion about where we are in the world in 2025–involves how good we are at having difficult conversations. Something we need to be skilled at when we’re talking about achieving the highest performance, when we’re talking about building the kind of organizations and structures we want, is understanding that it means making tough choices and that caring, passionate, well-meaning people will disagree. I really value people around me who are able to have those hard conversations productively.

If I put those two together, that’s the system and organization that I think will have success here.

2-layer neck gaiters will protect you throughout the seasons. Stretchguard fabric with extreme 4-way stretch for optimal comfort. Super soft, silky feel that is lightweight and breathable. 100% performance fabric, washable and reusable.

$20

ALL AVAILABLE WITH YOUR TEAM LOGO AT NO EXTRA CHARGE (MINIMUM 12)

UNITED STATES ROWING UV

VAPOR LONG SLEEVE $40

WHITE/OARLOCK ON BACK

NAVY/CROSSED OARS ON BACK

RED/CROSSED OARS ON BACK

PERFORMANCE LONG SLEEVES

PERFORMANCE T-SHIRTS

PERFORMANCE TANKS

Order any 12 performance shirts, hooded sweatshirts, or sweatpants and email your logo to teamorders@rowingcatalog.com and get your items with your logo at no additional cost!

For coaches, it’s about the right progression of intensity and duration and motivating to achieve success. For rowers, it’s about pursuing athletic ambitions with renewed vigor.

The beginning of the year can be a difficult time for athletes. The days are short. The weather is not the nicest. And we are coming out of a period of holidays and renewed reflection during the calendar changeover. On top of that, training has been suspended while schools, colleges, and clubs are closed. Family comes first for rowers and coaches as well, so the focus is not on training. This phase of training is called the “transition period” for a reason. As athletes

themselves choose how and how long they’ll train or recover from injury, they move from the regimented training of their school programs to individualized exercise. This doesn’t mean physical activity ceases. Some rowers may spend a few days crosscountry skiing or running on a warm beach. Such a break can be beneficial and refreshing; when rowers resume highperformance training, they are more likely to do so with renewed excitement and commitment.

I remember vividly my experience as head rowing coach at the University of Western Ontario when students came back to school in early January. It was a trying time not only because students had to get back into organized workouts at times of day when it was dark and cold outside but also because long endurance runs, rowing on the ergometer, and strenuous sessions of weightlifting were not exactly appealing. For coaches, the challenge is to design the right progression of training intensity

and duration and to prepare and motivate rowers for the upcoming effort required to achieve success. For athletes, the transition period is a time to reflect on goals and plans to meet their athletic ambitions and to return to their performance program with renewed vigor.

Coaches should review topics such as self-awareness and visualization and discuss individual and team goals.

This point in the season is a good time for coaches to convene meetings that develop and improve what Penny Werthner, in my latest book, Rowing Science, calls “critical psychological skills for highperformance athletes.” In these meetings, coaches should review topics such as selfawareness and visualization and discuss individual and team goals. I have found such meetings to be very effective in giving athletes a renewed mental and physical focus.

Coaches should prepare for these meetings by analyzing previous training, testing, and competition results, determining the level of training and performance required to achieve program goals, and identifying each athlete’s strengths and weaknesses. This information will provide a clear picture of what the program and each rower should strive for and what actions must be taken. When the pathways to success are defined, it’s motivating for all.

As Penny Werthner says, “The continual development of all of these psychological skills ensures that each athlete, whether in singles or a crew boat, develops a deep sense of self-awareness, a solid level of self-confidence, and the psychological resilience necessary to cope effectively with the stress and demands of training and competition within the world of competitive sport, at all levels.”

VOLKER NOLTE, an internationally recognized expert on the biomechanics of rowing, is the author of Rowing Science, Rowing Faster, and Masters Rowing. He’s a retired professor of biomechanics at the University of Western Ontario, where he coached the men’s rowing team to three Canadian national titles.

Traveling for a camp can be one of the best experiences you’ll share with your team—flat water, great bonding, and fast rowing in a new environment. But it also can be draining.

If you’re lucky this season, you’ll be packing a bag and getting on the water for a training trip with your team. As with everything about coxing, a little preparation goes a long way.

First, you need to get there with the right gear. Make a packing list so that you have everything you need for days on and off the water. Check the weather; just because you’re southbound doesn’t mean you’ll be basking in sunshine. If it’s going to rain for multiple days, pack enough waterproof layers and shoes that you won’t need to put your own soggy clothes back on. Read your itinerary, and make sure you have enough snacks, sunscreen, and battery charge to get you through the first day or two, since you’ll probably arrive and go straight to rigging and rowing.

Training camp means that you might be going from a relatively straightforward

body of water to one with a lot more places to go—and more places to make a wrong turn.

“Look at a map. Know where north, south, east, and west are and know the traffic patterns in general,” advised Tessa Gobbo, the Loyalty Chair for Women’s Crew at Brown University (and 2016 Olympic gold medalist). “Everybody’s a little unnerved on a new body of water. It’s your job to know what’s happening. So look at a map.”

Use Google Maps to orient yourself with an overhead view (it’s good to know how the cardinal directions relate to the venue) and Google Earth to help identify some landmarks that you can connect to visually when you arrive. You can get creative here; power lines, buoys, notable houses, and odd flora are all good options.

Mastering the course beforehand allows you to show up every session ready to focus on anything else that might arise. Training trips always bring some adventure. Maybe the launch dies, maybe a pod of dolphins crashes your steady-state row. If you haven’t been in the coxswain’s seat in a little while, you might be feeling a bit rusty. Jump in with both feet.

“This is your time to be there and be involved with everything,” said Gobbo. “Make sure that when you’re around the team you’re ‘on.’”

Be present during practice and give yourself some time between sessions to rest and recover, just like your rowers. While you might not be taking strokes, out on the water your brain is hard at work.

Traveling for a camp can be one of the best experiences you’ll share with your team—flat water, great bonding, and fast rowing in a new environment. But it also can be draining. You’ll spend much of your day on the water, not always in ideal conditions, and a lot of time will be spent in selection. Emotions can run high.

This is a good moment to remember your oversized emotional influence on your team. You can make a tough practice better.

“You can set the tone more than you realize,” Gobbo said. “You want the team to be serious but have a good time? You can be serious but have a good time. You want your boat to go fast on the water? You’re only talking about that boat going fast on the water, not other stuff. It sounds super simple, but it’s so rare that a sport has a designated leader.”

A training trip is an opportunity to get back on the water and set the tone for the coxswain you’ll be this season. If you come prepared, treat your teammates well, and meet challenges with earnest effort, you’ll be on your way to a good spring.

While coaches can advocate for rowing recruits, the final decision rests solely with the university’s admissions office.

The role of athletic recruitment in the university admissions process varies widely among institutions, particularly in rowing

At some universities, coaches can advocate for potential recruits by adding them to a list supported by the athletic department, enhancing significantly their chances of admission. At other institutions, coaches may be allocated a specific number of slots for their teams. For example, a university might reserve 10 spots each for men’s and women’s rowing recruits.

Elite schools often impose academic thresholds, requiring recruits to meet minimum GPA or standardized test-score requirements. Meanwhile, some universities provide their coaches with general guidelines for what admissions is seeking but offer little to no direct influence over the admissions process.

Given these variations, there is no onesize-fits-all answer to whether recruitment can help with admissions. For instance, a rowing recruit might be assured admission at one prestigious institution, only to be

denied at another with comparable academic standing.

An admissions officer at a major university once described the admissions process as “peeling back the layers of an onion.” Each layer reveals new information, prompting additional questions or requests for clarification. This analogy underscores the complexity of admissions decisions, even for recruited athletes.

It’s important for rowing recruits to understand that while coaches can advocate for them, the final decision rests solely with the university’s admissions office.

As a recruit, ask your recruiting coach about admissions policies early in the process. You may be pleasantly surprised—or caught off guard—by the level of support available from the rowing staff. Understanding these nuances can help you navigate the process with clarity and confidence

You don’t have to have a “perfect diet” to have an excellent diet. The goal is 90 percent quality foods and, if desired, 10 percent fun foods.

Believe it or not, eating a good sports diet can be simple. Yet too many rowers have created a complex and confusing eating program, with good and bad foods, lots of rules, and plenty of guilt. Let’s get back to the basics and enjoy performance-enhancing fueling with these simple ABCs for winning nutrition.

Appreciate the power of food and the positive impact it has on athletic performance. Also notice the negative impact of hunger on your mood, ability to focus, and energy. As a rower, you are either fueling up or refueling. Every meal and snack has a purpose. Be responsible!

Breakfast: Eat it within three hours of waking for a high-energy day. If you’re not hungry in the morning, cut back on evening snacks (with little nutritional value) and

you’ll be ready for a wholesome morning meal. Alternatively, eat that wholesome morning meal at night in place of the snacky foods.

Carbohydrates are the preferred source of muscle fuel for hard exercise. Do not “stay away from” pasta, potatoes, bread, bagels and other starchy foods that are deemed fattening, wrongly, but actually help keep your muscles well fueled. Serious rowers who minimize carb intake risk having poorly fueled muscles.

Dehydration slows you down, so plan to drink extra fluid 45 to 90 minutes before a hard workout. That’s how much time the kidneys require to process fluid. Schedule time to tank up, urinate the excess, and then drink again soon before you begin to row.

Energy bars are more about convenience than necessity. Bananas, raisins, Fig Newtons and granola bars offer convenient fuel at a fraction of the price. If you prefer pre-wrapped bars, choose ones made with wholesome ingredients such as dried fruits, nuts, and whole grains.

Foods fortified with iron can help vegetarians and non-meat eaters reduce their risk of becoming anemic. Iron-fortified breakfast cereals, such as raisin bran, GrapeNuts and Wheaties, offer more iron than all-natural brands with no added iron, such as Kashi, old-fashioned oats, and granola.

Gatorade and other sports drinks are designed to be used by rowers during extended exercise, not as a mealtime beverage or snack. Most meals contain far more electrolytes than found in a sports drink.

Hypoglycemia (low blood sugar, characterized by lightheadedness, fatigue, and inability to concentrate) is preventable. To eliminate 4 p.m. low blood sugar, enjoy a hearty mid-afternoon snack.

Intermittent fasting might offer health benefits for an over-fat, under-fit sedentary person, but it’s not designed for rowers. Extended time without food puts your body into muscle-breakdown mode.

Junk food can fit into your sports diet in small amounts. You don’t have to have a “perfect diet” to have an excellent diet. The goal is 90 percent quality foods and, if desired, 10 percent fun foods.

Keto, Paleo and other fad reducing diets “work” because they limit calorie intake. But when dieters escape from food

jail, backlash takes its toll. Your better bet: Learn how to eat appropriately, not diet restrictively.

Lifting weights is key to building muscles. Carbohydrates provide the energy needed to lift heavy weights. To support muscular growth, choose carbohydratebased meals with a side of protein, as opposed to protein-based meals with minimal carbs.

Muscles store carbohydrate (grains, fruits, veggies) as glycogen. When replenishing depleted glycogen to prevent needless fatigue, muscles store about three ounces of water for each ounce of carb. Hence, a rower might gain two to four pounds of water weight when refueling on a rest day.

Nutrient-dense whole foods are so much better for your health than ultraprocessed foods. By satiating your appetite with hearty breakfasts and lunches, you’ll curb your desire for afternoon and evening chips, cookies, instant meals, and other highly processed foods—and may not even miss them!

Obsessed about food and weight? If you spend too much time thinking about what or what not to eat, meeting with a sports dietitian can help stop the struggle. Eating should be intuitive.

Protein is an important part of a sports diet. It helps build and repair muscles after hard workouts, but it does not refuel muscles. A recovery drink should offer three times more carbs than protein. Choose chocolate milk instead of a protein shake with minimal carbs.

Quality calories are abundant in natural foods. Be sure there are more apple cores and banana peels than energy bar wrappers and ultra-processed food packages in your wastebasket.

Rest is an important part of a training program; your muscles need time to heal and refuel. Plan one or two days with little or no exercise per week. You might feel just as hungry on rest days as on exercise days. That’s because your muscles are replenishing depleted glycogen stores with the foods you’re eating.

Sweet cravings are a sign you’ve gotten too hungry. Curb the cravings by eating more breakfast and lunch. Stop eating at those meals when you’re feeling satiated, not because you think you should or because the food is gone. You’ll have more energy

and less desire for sweets later in the day. Trust me.

Thinner does not equate to performing better if the cost of being thinner is skimpy meals and poorly fueled muscles. Instead, focus on being well-fueled, strong, and powerful.

Urine that is dark and smelly indicates a need to drink more fluid. (Fluid includes coffee, yogurt, and watery foods). Well-hydrated rowers have pale urine and urinate every two to four hours.

Vegetarian rowers who do not eat meat should include plant protein at every meal and snack. Suggestions: peanut butter on a bagel, hummus with baby carrots, nuts or seeds in a salad. Weight is more than a matter of willpower; your genes play a role. Forcing your body to be too thin is abusive. If you are far leaner than others in your family, think twice before trying to lose even more weight.

Extra vitamins are best found the all-natural way—in dark, colorful vegetables (broccoli, spinach, peppers, tomatoes, carrots), or in fresh fruit (oranges, grapefruit, cantaloupe, strawberries, kiwi). Chow down!

Yes, you can fuel your engine optimally. The trick is to prevent hunger. When too hungry, you’ll likely grab the handiest—but not the healthiest—food around. Experiment with front-loading your calories.

Zippy and zingy. That’s how you’ll feel when you fuel with premium nutrition. Eat well and enjoy your high energy!

For personalized nutrition help, consult with a registered dietitian (R.D.) who is a board-certified specialist in sports dietetics (C.S.S.D.). Use the referral network at eatright.org to find your local sports dietitian.

NANCY CLARK, M.S., R.D., C.S.S.D., counsels both fitness exercisers and competitive athletes in the Boston area (Newton; 617-795-1875). Her best-selling Sports Nutrition Guidebook is a popular resource, as is her online workshop. For more information, visit NancyClarkRD.com.

Rowers must deal with two kinds of training loads—external and internal—and a coach’s job is to monitor how they respond.

Training load refers to how the physical impact of training creates stress and fatigue as well as adaptation and fitness. An athlete’s response to training load must be considered from external and internal perspectives.

Coaches need to monitor their athletes to manage the work/rest ratio that performance improves, injury risk is lowered, and team morale remains positive.

External load refers to the actual physical work completed by an athlete. It can be manipulated by session or periodized in cycles by intensity or volume. Internal training load—VO2 max, lactate, or rate of perceived exertion—is the individual’s reaction to the stress of the external work.

It’s important to monitor the internalload response because athletes have different diets, daily demands, and lifestyle

habits; two athletes on the same crew can respond to the same workout in very different ways. The external load may be the same, but the internal load varies.

Coaches need to monitor their athletes to manage the work/rest ratio so that performance improves, injury risk is lowered, and team morale remains positive. This can be a challenge with large teams.

A quick, effective strategy is to track sRPE—session rating of perceived exertion. Ask the question: “How hard was your workout?” Then, 30 minutes after the end of practice, using a scale of 1 to 10, have each rower assign a value.

Simple to use, sRPE reflects the effect of environmental strain (wind, cold, heat) and accounts for fatigue and the emotional state of your athletes. Over time, their accuracy and reliability will improve.

There are, of course, more detailed ways to assess internal load—monitoring heartrate or lactate levels—but that may not be practical for coaches with large teams with busy schedules.

MARLENE ROYLE, who won national titles in rowing and sculling, is the author of Tip of the Blade: Notes on Rowing. She has coached at Boston University, the Craftsbury Sculling Center, and the Florida Rowing Center. Her Roylerow Performance Training Programs provides coaching for masters rowers. Email Marlene at roylerow@ aol.com or visit www.roylerow.com.

Sometimes your most valuable contribution might be providing a different type of presence than your head coach.

Did I say too much? Not enough? Did it even make sense?”