ROW LIKE PIGS

THE MAN AND THE TEAM BEHIND THE CLASSIC ROWING DOCUMENTARY

WHEN ‘EAT LESS, MOVE MORE’ DOESN’T WORK

THE MAN AND THE TEAM BEHIND THE CLASSIC ROWING DOCUMENTARY

WHEN ‘EAT LESS, MOVE MORE’ DOESN’T WORK

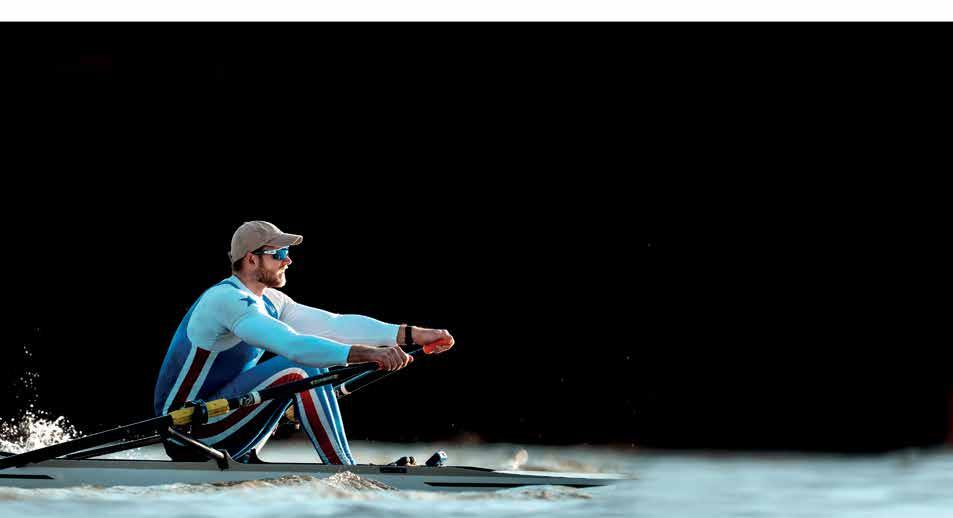

USA, U19 W8+, Gold Medalists // U8.21 STEALTH

2024 World Rowing Under 19 Championships

UPGRADE YOUR COXBOX AND SAVE BIG!

Spring season is here—make sure you’re ready with the most advanced coxing tool on the water. For a limited time, trade in your old CoxBox and get $150 OFF the COXBOX GPS—an EXTRA $50 BONUS SAVINGS!

NO COXBOX TO TRADE IN? No problem! You can still get $100 OFF the CoxBox GPS.

2-Year Warranty: No more repairs on older models!

Live Stream Boat Data: Connect to LiNK Logbook for real-time insights. Superior Audio & Performance: The best tool to keep your crew in sync.

The all-new Fluidesign rigger is engineered to elevate performance like never before. Crafted with cutting-edge materials and aerodynamic design, this rigger redefines stiffness efficiency and performance.

Unrivaled performance in waves Excellent straight-line speed Stable learning platform

Place a deposit on a new Prophet CF C1X, Remedy FG C1X, Remedy CF C1X, or Remedy FG C2X and receive a scale model boat for them to open at Christmas. Take delivery of the actual boat once it’s warm enough to row.

Chip Davis PUBLISHER & EDITOR

Chris Pratt ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER

Vinaya Shenoy ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT

Art Carey ASSISTANT EDITOR

Madeline Davis Tully ASSOCIATE EDITOR

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Andy Anderson | Nancy Clark

Tom Matlack | Volker Nolte

Marlene Royle | Robbie Tenenbaum

Hannah Woodruff | Emily Winslow

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS

Jim Aulenback | Steve Aulenback

Karon Phillips | Julia Kowacic

Patrick White | Lisa Worthy

MAILING ADDRESS

Editorial, Advertising, & Subscriptions PO Box 831 Hanover, NH 03755, USA (603) 643-8476

ROWING NEWS is published 12 times a year between January and December. by The Independent Rowing News, Inc, 53 S. Main St. Hanover NH 03755 Contributions of news, articles, and photographs are welcome. Unless otherwise requested, submitted materials become the property of The Independent Rowing News, Inc., PO Box 831, Hanover, NH 03755. Opinions expressed by authors do not necessarily reflect those of ROWING NEWS and associates. Periodical Postage paid at Hanover, NH 03755 and additional locations. Canada Post IPM Publication Mail Agreement No. 40834009 Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to Express Messenger International Post Office Box 25058 London BRC, Ontario, Canada N6C 6A8.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to: ROWING NEWS

PO Box 831, Hanover, NH 03755. ISSN number 1548-694X

ROWING NEWS and the OARLOCK LOGO are trademarks of The Independent Rowing News, Inc.

Founded in 1994

©2024 The Independent Rowing News, Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without written permission prohibited.

PLEASE SHARE OR RECYCLE THIS MAGAZINE

Follow Rowing News on social media by scanning this QR code with your smart phone.

The raw documentary about the successful 2003 Dartmouth crew is a cult classic and perhaps the best film ever made about rowing. It’s all that—and much more.

BY TOM MATLACK

Last year’s collegiate national champions face the daunting challenge of repeating.

BY CHIP DAVIS

DEPARTMENTS

USRowing Changes

Kiwis and Hoosiers on Tap for Opening Day

Regattas Raise 2025 Entry Fees

Sports Science Spring Training

Coxing Coping with Race Day Nerves

Recruiting What Really Matters

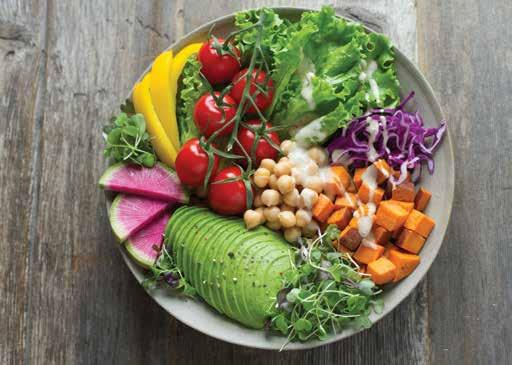

Fuel When ‘Eat Less, Move More’ Doesn’t Work

Training Eye on the Goals

Coach Development The Launch Is a Classroom

CHIP DAVIS

It’s been a long time coming, and it will be over before we know it. Finally, spring—the real racing season—is here. Hard in its wake will be championship season, with regional championship and qualifying regattas leading up to national championships.

For some, especially in the North, it will be a mere eight weeks from shoving off the dock to putting away the boats for the summer. For others, like the thousands already racing in Sarasota and San Diego, five months of real racing—racing that matters—will be the reward for all the hard work from last autumn and through the winter.

The opportunity to develop ourselves beyond our preconceived limits.

The American Youth Cup, captured in three beautiful images by the incomparable Lisa Worthy on pages 18 to 23, drew junior crews from across the continent, including Newport Aquatic Center (California) and Bromfield Acton Boxborough and Wayland-Weston (both in Massachusetts).

From its inception in 2015, the AYC has sought to serve youth crews, especially in the Southeast, with little or no racing experience. Before AYC’s existence, crews from developing regions had scarce opportunities to row in 2,000-meter buoyed-lane races before Youth Nationals and its qualifying regattas.

Organizers don’t want to take direct credit, but the results have followed. “It’s all about the kids,” said Sarasota Crew organizer Rick Brown, who spent the windy February weekend helping young crews, including middle-schoolers, learn how to row into position and lock in to a multi-lane starting platform.

At the other end of the racing-experience spectrum, the top college crews are racing their way toward national championships, where great recruits, great coaches, and tremendous institutional support are required to compete for the titles of the country’s very fastest men’s and women’s crews. In my season preview, I suggest a fourth ingredient may be what makes an IRA or NCAA champion. Read about it beginning on page 34.

Not every college crew recruits its way to wins, especially in the American College Rowing Association, which is for club programs as opposed to programs sponsored by their school’s athletic (and admissions) department.

It wasn’t too long ago (about 20 years—a lifetime for most rowers) that even some of the best varsity programs weren’t comprised mostly of recruits. It was also the early days of what is now called “user-generated content” and “reality shows.” Back then, a Dartmouth walk-on oarsman named David Shamszad made what might be the best, most raw rowing documentary ever, Row Like Pigs. In his double feature for this issue, Tom Matlack (also a walkon oarsman “back in the day”) tells the story of how that gritty film and the stories of the oarsmen told in it captured the essence of our sport—the opportunity to develop ourselves beyond our preconceived limits.

Our editorial team can be reached at editor@rowingnews.com

I did not realize that USRowing is now such a large and successful organization with a sufficient budget surplus that it’s able to afford a new C-level position with a posted salary of $160,000 a year.

It’s my understanding that USRowing’s membership base is shrinking as rowing organizations and events question the value received for the cost of association, but maybe I’m misinformed.

Reading the “HR Speak” job description for the proposed chief experience officer (CXO), we find that the list of tasks the candidate is to perform look a great deal like what the current CEO or executive director or the other three C-level positions, two senior directors, 11 directors, and one associate director are supposed to be doing, presumably ably assisted by a substantial staff supported by both part-time and volunteer positions in USRowing headquarters.

And yet the organization is still not doing or even really acknowledging the need for what its primary mission should be—the growth of our sport.

Growing the rowing membership and programs requires going out and working with people on the ground in the regions to

help them do their jobs and entails:

* Finding more rowable bodies of water;

* Developing more boathouses and more rowing programs;

* Developing more effective recruiting tools to help get more kids – including potential Olympians – involved in our sport;

* Developing many more highly qualified coaches;

* Developing and publishing more resources to help guide the growth and teach people what needs doing and how best to do it;

* Providing support for all the volunteers who will make the ground-level growth actually happen;

* Recruiting more people who will dedicate immense amounts of time and resources to growing their local programs.

Assuming we need this position at all, where is the emphasis in the job description on growth and the necessary support of the membership?

Selecting and training and managing the national teams is important, but that’s the job of Josy Verdonkschot and his staff. Do we really need an “experience officer” to assist in that? Shouldn’t the board consider funding regional work and spending the $160,000 plus on the six items listed above?

The job description and skill requirements were written in Human Resources Speak and never once mention

depth of experience with rowing. Imagine IBM advertising for a senior executive without seeking experience in a high-tech business.

What HR consultant proposed and wrote this job description? Aren’t these responsibilities already part of the job of the CEO and executive director? Like delivering “meaningful and sustainable value to USRowing individual and organizational members through effective, scalable, and mission-aligned grassroots programs, and supporting other internal USRowing (internal, administrative) teams.”

Or being—and here the HR consultant really soared—“a true end-to-end owner who can deliver programs and projects from ideation to execution to evaluation, a player-coach who scales by working cross-functionally through others while maintaining close attention to the details and rolling up their sleeves when needed, an operator who actively manages P&Ls to drive organization stability, and a strategic and clear-eyed thinker who aligns long-term goals with the steps required to achieve them.”

Wow!

But isn’t someone already doing that?

W.R. Pickard Seattle

Now, more than ever, the Gay + Lesbian Rowing Federation (GLRF) is essential as a safe space for rowers, coxies, coaches, and race officials. As an individual membership online community, GLRF offers a continuous connection between members of the LGBTQ rowing community and clubs, programmes, organizations and vendors in the broader rowing community.

We want to highlight a powerful tool on our community platform: the Share A Link feature. It provides an opportunity for LGBTQ rowers and supportive allies to promote rowing clubs or programmes, and other rowing-related entities that genuinely support acceptance and inclusion. The goal is to help both GLRF members and website visitors to find a rowing home, vendors, and other resources where they can trust they will feel welcomed and comfortable in their identity.

Every Share A Link listing provides a descriptive text space to describe the club or programme, vendor, or organization and any supportive language for LGBTQ acceptance and inclusion. Share A Link users can search by categories, geography, and by tags, helping them find an accepting space to row and participate in the sport. The categories, covering all aspects of the rowing experience, include:

• Clubs & Programmes

• Open Ocean Race Teams

• Boat, Oar, and Erg Manufacturers

• Rowing Retailers

• National and Regional Rowing Federations/Associations

• Rowing Resources

• Training and Fitness Resources

• Rowing 101

Representatives of LGBTQ-inclusive clubs and programmes, vendors, and organizations are welcome to add a link for their entity.

Why does this matter now?

The current political climate, the assault on Diversity, Equity and Inclusion policies and programmes, and threats against LGBTQ participation in sports in the United States will (among many other things) make it harder for LGBTQ individuals to find places where they can feel comfortable and safe, and for organizations to express support for the LGBTQ community.

Although we believe there is an urgent need to show support from the North American rowing community, it is equally important for this resource to be built out worldwide. We call on the global rowing community to support our Share A Link feature. With robust input from both the LGBTQ rowing community and allies, Share A Link will be a powerful tool.

The Gay + Lesbian Rowing Federation isn’t just for LGBTQ individuals. We warmly welcome allies. Our registration system doesn’t ask anyone’s sexual orientation, just a person’s gender identity. Belonging to the Gay + Lesbian Rowing Federation helps expand our network and strengthen our community.

Registering with GLRF is free, as is adding Share A Link listings (you must register to be able to add to Share A Link).

Gay + Lesbian Rowing Federation - https://glrf.info

The Bolles School’s girls quad was one of 96 racing at the American Youth Cup, Feb.15 and 16, at Nathan Benderson Park in Sarasota. The event hosted by Sarasota Crew drew 567 entries from 31 clubs, with many participants racing in three or more events.

Eight crews lined up for the third heat of the men’s youth quad event on Saturday, Feb. 15, at the American Youth Cup at Nathan Benderson Park in Sarasota. Other events used all 10 lanes of the 2,000-meter course, including the middle-school eights. “It’s sweet to see that, kids get into it,” said organizer Rick Brown.

The American Youth Cup, Feb. 15 and 16, at Nathan Benderson Park in Sarasota, features multiple small-boat and sculling events, in addition to eights and fours. The regatta is designed to give crews experience and to allow coaches to try different boat classes, says organizer Rick Brown.

The change was forced partly by regattas inquiring about deregistering from USRowing so they can welcome the growing number of programs dropping membership.

After the departure of several major regatta organizations, USRowing has backed off its blanket requirement that all coaches obtain USRowing certification for 2025. Rowing programs will not be required to have all their coaches certified with USRowing to compete in USRowing-registered regattas this year, although uncertified individual coaches will not be allowed to coach at such events.

USRowing now views 2025 as a “transition year” and is eager to “work with programs and their participants before and after to drive compliance,” the national

governing body stated in response to questions from member organizations.

“The lead-up to the [San Diego] Crew Classic is a great place to initiate the certification process for coaches; it’s not the finish line,” said USRowing CEO Amanda Kraus. “We look forward to working with coaches and teams over the year to ensure a seamless and efficient certification process.”

Rowing News has learned that the change was forced partly by regattas inquiring about de-registering from USRowing so they can welcome the growing number of programs dropping USRowing

CONTINUES ON PAGE 26

The Canada Cup Regatta, a development event featuring the top under-21 rowers from each province will return in 2025, Rowing Canada Aviron announced. Participating provinces can bring up to 17 athletes—eight males, eight females, and a coxswain of either gender—to race singles, doubles, pairs, quads, and eights in 500-meter and 2,000-meter races. Michael Simonson of Rowing Alberta calls it “a stepping stone for the next generation of athletes, as they continue their pursuit in representing Canada on the international stage.” The last scheduled Canada Cup was canceled in 2020 because of Covid.

organizational membership. Shortly after the change, USRowing announced that executive director Rich Cacioppo would be stepping into “a strategic advisory role” and his position transformed into “chief experience officer.” Cacioppo received $180,800 in compensation in fiscal year 2023, according to USRowing’s latest-available tax filings. The new position advertises a $160,000 salary.

“It’s often said that no one is irreplaceable, but if anyone comes close, it’s Rich,” Kraus said. “He will be tremendously missed.”

In her January message to USRowing members, Kraus told a story culminating in the moral “Show me where you put your money, and you’ll tell me what you care about.”

reduce the risk of phishing (tricking people into revealing personal or confidential information for illicit purposes), Kraus has said. But according to another USRowing staffer, another reason was to reduce the number of voicemail messages staff members were receiving stemming from confusion about complying with the new certification requirements.

An “Ask USRowing” online form meant to provide an alternative to direct staff contact was not functioning in mid-February when this report was filed, although other online forms for grievances, safety reporting, and grant applications were available.

Responding to a Rowing News email objecting to the new communication restrictions, Kraus wrote, “I understand your frustration, but our policy is to channel all press inquiries through our marketing and communications team. This applies to all media outlets, not just Rowing News.”

Other changes at USRowing include removing from its website contact information for both board board members and staff.

USRowing’s most recent financial statement (FY2023) shows $4.4 million for salaries and benefits and slightly more than $3.5 million for travel and meetings. Combined, those amounts constitute more than half of the national governing body’s $15.6-million budget. The 2024 high performance budget for Olympic and world championship rowing was $5.6 million— with a $2.6 million deficit—according to the USRowing high performance plan.

Other changes at USRowing include removing from its website (USRowing. org) contact information for both board members and staff. Henceforth, all media queries must be directed to media@ usrowing.org, according to Kraus.

The contact information was erased to

Kirsten Feldman, the chair of USRowing’s board of directors, copied by Kraus on her response, included this reporter inadvertently in her reply.

“He [Chip Davis] just doesn’t get it. His last issue moaned about the fact that we have so much money to raise for the Olympic team, and now he’s complaining that we are run like a private foundation. Last year, he complained about low voter turnout in elections.”

In February, USRowing announced the results of the 2024-25 board election, in which only 40 percent (234 of 580) of eligible member organizations cast a ballot. Feldman won reelection as Northeast Regional Representative with 92 votes. The low 2024-25 election turnout was an improvement over the previous election, when the turnout was only 25 percent and several candidates voiced frustration with the process.

“I feel proud of the number of calls and communications we’ve had in the last few months,” wrote Feldman. “Communicating with members has been 50 percent of my time during the election period.”

CHIP DAVIS

$445 $495 AVAILABLE NOW!

Large Configurable Display (2, 4 and 6 fields)

Optional Wireless Impeller & Accessories

Easy Data Transfer via the DataFlow App

200m+ Transmission Range

Pair with up to 5 units at the same time.

The gift will enable the U.S. National Team to use extensive analytics and data to develop and strengthen promising elite rowers over the next four years.

The Zagunis family has given $500,000 to pay for the embedded scientist called for in USRowing’s high performance plan for the years leading up to the 2028 LA Olympics.

“The Zagunis Family Embedded Scientist will allow the U.S. National Teams to use extensive analytics and data to develop and strengthen our athletes and help us accomplish our goals over the next four years,” Verdonkschot said.

“We are incredibly grateful to Robert Zagunis and his family for this gift, which will provide the support our national team athletes and coaches require.”

Verdonkschot, along with U.S. Olympic coaches Casey Galvanek (men’s four) and Michael Callahan (men’s eight) used technology like Peach Innovation’s precision-measurement system as well as data and analysis from Brian deRegt to refine the performance of the two U.S. crews that won medals—gold for the four, bronze for the eight—at the Paris Olympics.

“As I experienced in missing the Olympic finals in ’76 by a bow ball, the margins are slim, and a slight improvement makes a big difference,” said Robert Zagunis, an investment manager who was a member of the U.S. Olympic coxed four at the Montréal Olympics.

USRowing advertised the position with a salary range of $90,000 to $105,000. The online job posting has closed, and Verdonkschot said he hopes to finalize a hire by the end of February or the beginning of March

Oar Board®

New Zealand’s men’s and women’s crews will compete in the Windermere Cup races, and Indiana’s women will vie for the Windermere and Cascade Cups.

The University of Washington’s rowing programs and Windermere Real Estate will host men’s and women’s crews from the New Zealand National Team and Indiana University at the 39th annual Windermere Cup and Opening Day Regatta, Saturday, May 3, on Seattle’s Montlake Cut.

“We’ve been looking forward to having New Zealand back at Opening Day for a very long time, and we’re excited to welcome fellow Big Ten team Indiana,” Washington head coach Yasmin Farooq said. “This has the potential to be an epic race for all three teams.

New Zealand will be sending men’s and women’s crews to compete in the Windermere Cup races, while Indiana’s

women’s program will compete in the women’s Windermere and Cascade (second varsity eights) Cups.

Washington’s current women’s roster includes four athletes from New Zealand: Olivia Hay, Zola Kemp, Shakira Mirfin, and Madeleine Parker. The Husky men’s roster boasts seven Kiwis: Harry Fitzpatrick, Kieran Joyce, Marley King Smith, Oliver Leach, Will Milne, Ben Shortt, and Logan Ullrich, who won an Olympic silver medal in Paris as a member of the Kiwi four.

On the Friday night before the Opening Day Regatta, all of the Windermere Cup crews will race in the annual Twilight Sprints, a race from the traditional Montlake Cut finish line to the eastern end of the Montlake Cut.

USRowing entry fees up 30

Percent, others will set 2025 entry fees after calculating new insurance costs. NEWS

USRowing announced last month that regatta entry fees will go up roughly 30 percent, after two years of no increases.

The national governing body attributed the hike to rising costs, including for improved safeguarding practices, additional referee support, and local organizingcommittee expenses.

Annual inflation rates have run between 3.2 and 8.0 percent since 2021, according to the Federal Reserve Bank.

Regattas run by the Intercollegiate Rowing Association will also raise entries fees this year.

“We historically have raised them slightly every year,” said commissioner Laura Kunkemueller. “This year is similar.”

Other regattas run by organizations that have left USRowing will set 2025 entry fees after calculating new insurance costs.

Annual inflation rates have run between 3.2 and 8.0 percent since 2021, according to the Federal Reserve Bank. What you could buy for $100 back then will cost you $121 now, according to The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Price Index Inflation Calculator.

Entry fees vary widely across regattas. The standard cost for eights in last month’s Sarasota Invitational was $180. Last year, the standard cost for eights at the Head of the Charles was $650, and $2,400 for Directors Challenge eights, a charitable fundraising event.

Far more crews apply to race at the Charles than can be accommodated, even after the racing schedule expanded to three days.

Texas, Washington, Notre Dame, Vanderbilt, Western Washington, Tufts, Princeton, and Harvard will seek to defend titles, as others vie to seize them.

STORY BY CHIP DAVIS

In 2024, Harvard’s varsity heavyweights became the first program besides Cal, Washington, and Yale to finish first or second at the IRA in the last decade when they finished second to Washington at the national championship.

Defending NCAA Division I national champion Texas faces one of the greatest challenges in all of sport: repeating.

The Longhorns have done it before, successfully defending their 2021 championship in 2022 (and Texas coach Dave O’Neill did it previously, in 2005 and 2006, when he was Cal’s head coach).

And they’ve won three of the last four, with Stanford winning in 2023 and finishing second (twice tied on points) the other three years.

Washington and Cal alternated as NCAA Division I national champions for four years, 2016 to 2019 (2020 was canceled because of Covid), and Ohio State won three straight before that.

On the men’s IRA side of collegiate rowing, Washington faces the same great challenge to repeat as national champions,

before outdistancing the Crimson to win the IRA.

If that fourth factor—a racing schedule that includes the other best crews—is the key to a national championship in an era dominated by recruiting and institutional support, Tennessee’s Lady Vols might be the NCAA favorites, while Washington is the favorite to win the IRA.

In 2024, Tennessee’s first season under head coach Kim Cupini, Tennessee rowing recorded the best season in program history with a third-place performance at the NCAAs. Now in her second year—and first full calendar year after beginning late last year—Cupini has the most complete topto-bottom racing schedule in college rowing this spring.

“We love racing and have a hard schedule,” Cupini said. “We’re racers.”

Tennessee will welcome Stanford to

“WE HOPE THE RHYTHM OF THE

having broken Cal’s two-year streak last year. Washington won the Covid-limited 2021 IRA after the canceled 2020 regatta. Yale ruled the regatta for three years, from 2017 to 2019. In the past decade, only Cal, Washington, and Yale have finished first or second, until Harvard finished second to Washington in 2024.

Over the past decade, the NCAA and IRA have featured little variation in who wins the championships. It takes great coaching, great recruits, and tremendous institutional support—all working hard and working together—to win the premier events.

Last year, both the IRA and NCAA champions shared something else: schedules that featured racing their closest competitors across the country before the championship regatta. Texas traveled to, and won, the 2024 San Diego Crew Classic and hosted Stanford for the Longhorn Invite before winning the NCAAs. Washington traveled to Sarasota to race, and lose to, Harvard

Oak Ridge’s Melton Hill Lake, its home course just west of Knoxville, on March 29. The next week, the Lady Vols host the firstever Rocky Top Invite before heading to Sarasota for the biggest non-championship college regatta, the Big Ten Invitational.

That regatta features 23 NCAA Division I programs: 11 from the Big Ten—Washington, Michigan, Ohio State, Rutgers, Indiana, USC, UCLA, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan State and Iowa— plus 12 guest schools—Tennessee, Brown, Penn, Duke, Oregon State, Alabama, Notre Dame, Harvard, Miami, SMU, Oklahoma and Clemson. The field includes 12 of last year’s top 20 and half of the top 10.

Then Tennessee goes to Princeton to race the Tigers, Ohio State, and Syracuse, before hosting the first annual SEC Championship against Texas, Alabama, and Oklahoma.

Besides racing, the winning edge comes from “the hard work that the women put in,” Cupini said. “Everyone thinks it comes

The ACRA National Championship features tight competition, with no one school repeating as men’s champion since 2016 (Michigan).

Princeton’s lightweight women won their third-straight IRA Commissioner’s Cup in 2024.

down to resources, but it’s a lot about the coaches, the athletes, and the work. It takes a lot of work; it’s an endless grind.”

“Racing other fast crews helps, no question,” agreed Yale head coach Will Porter. “Ivies is good prep for NCAAs.”

Although the Yale women’s crew has had to deal with several injuries over the winter, “the team is really good as far as people, culture, and vibe,” Porter said. “They operate at a high level, they’re mature. I’m happy with where we are right now.”

The current college athletics environment, in which student-athletes can switch schools annually and take advantage of five, even six years of eligibility at programs that include graduate students, is “super-annoying,” Porter said.

“It’s a bold new world, but it doesn’t change what we do,” he continued. “We do what we do and see where we stack up. We’re good chasing great.”

In the heavyweight men’s IRA nationaltitle chase, Washington wades into the 2025 spring season with the Husky Open and Class Day regattas at home before diving into the deep end in Sarasota at the end of March.

On Friday the 28th, the team races Harvard for the re-established Bolles Cup, honoring the legendary Tom Bolles, who attended and coached Washington in the 1920s and ’30s before moving to Harvard in 1936 to coach and serve eventually as athletic director.

The next day, Washington races Yale, Brown, and Northeastern for the Benderson Cup. The Huskies return to the West Coast for duals against Stanford, Oregon State, and bitter rival Cal, before racing the New Zealand National Team for the Windermere Cup at the Opening Day Regatta. The new Mountain Pacific Sports Federation conference championship begins their post-season, which culminates in the IRA National Championship in Camden, New Jersey.

“We hope the rhythm of the spring racing season will set up the students for success at the end of the season,” said UW men’s head coach Michael Callahan.

With eight of nine members of the 2024 American Collegiate Rowing Association national-champion men’s eight returning for 2025, Notre Dame should be a favorite to repeat as ACRA national champions.

They’re not.

That’s no slight to the club champions from South Bend. No one has repeated as ACRA champions since 2016 (Michigan), and Notre Dame will be trying to do it after its coach, alumnus Quinn Klocke, left for Washington, where he was hired as an assistant coach to work with freshmen (Klocke was a walk-on at Notre Dame).

Notre Dame “took some lumps in the fall,” said new coach Jack Newell, who left Clemson to take the head coaching position. Notre Dame will race a gauntlet of four big regattas—no dual races—this spring, including the ACRA National Championships, May 15 to 18, in Oak Ridge, Tenn.

Club nationals, now larger than the combined NCAA and IRA nationalchampionship regattas (exclusively for varsity programs sponsored by their athletic departments), has become at least as competitive as the NCAA and IRA, if not as fast. That’s because the top ACRA men’s programs, while not funded through their athletic departments, have more full-time coaches and tap into more alumni support than ever before.

“It’s an exciting time to be a coach at the ACRA level,” said Newell.

Like Notre Dame, Virginia, UCLA, Minnesota, Rutgers, Michigan, Orange Coast College, George Washington, Purdue, Bucknell, and others run programs that function like varsities at schools funding men’s and women’s rowing through their athletic departments.

The top ACRA programs are “club in name only,” said Newell, whose crew takes a winter training trip to Lake Lanier in Georgia and a spring training trip to Oak Ridge, Tenn., thanks in large part to Notre Dame alumni support. “We’re extremely grateful to them. They make a lot of things possible.”

Last year’s ACRA men’s favorite, Virginia, coached since 2009 by Frank Biller, could well be this year’s best bet to win.

“It’s super-competitive,” Biller said. “It’s pretty amazing. I don’t want to be anywhere else. The salaries are lower, the budgets are smaller, but down the road beyond my tenure, six-figure salaries will not be the exception.”

The ACRA coaches are “absolutely fierce competitors but all friends,” he said.

“The true spirit of competition is there. We don’t compete in recruiting. We all cook with the same water, the same ingredients. It’s a very level playing field.

“Our number-one goal is make the final. You can’t fuck up; otherwise you’re not in the final. Make the final, and anything can happen.”

Elsewhere in ACRA, Minnesota continues to build program culture and speed under Scott Armstrong, and Michigan remains a perennial favorite with depth and excellence developed by collegiate club rowing pioneer Gregg Hartsuff.

Michigan, Rutgers, Virginia, and Bucknell are scheduled to race March 29 in Pennsylvania on the Susquehanna, a contest that will be a major determinant of rankings before the Southern Intercollegiate Rowing Association regatta, April 18 and 19, in Oak Ridge, which this year will include for the first time the Columbia University lightweights.

On the women’s side, defending champion Vanderbilt returns as a favorite and will have sharpened its racing skills against NCAA Division I program Oklahoma in an April 5 scrimmage in Oklahoma City at OU’s Exchange Boathouse.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if they do it again,” said Bucknell coach Dan Wolleben. “The fall results are amazing.”

In November, the Vanderbilt women won both the collegiate eight and four at the Head of the Hooch, beating plenty of varsity programs.

Vandy rowing is led by head men’s and women’s coach Jon Miller, the 2024 ACRA Women’s Coach of the Year, who is in his 15th season leading the program. Miller began coaching at Vanderbilt in the fall of 2007 and became head coach in January 2009. Under his leadership, the team has won 14 SIRA medals and 10 ACRA medals.

In NCAA Division II, Western Washington seeks to defend its 2024 national championship, as does Tufts University in Division III. Princeton, the IRA women’s lightweight national champion, is favored to repeat, as is the defending men’s lightweight national champion, Harvard.

“To see a winning crew in action is to witness a perfect harmony in which everything is right,” George Pocock once said. At the end of the spring, for each collegiate national champion in each league—IRA, NCAA, and ACRA— everything will be right.

“This is your life. Who do you want to become?”

— Will Scoggins, Row Like Pigs

The raw documentary about the successful 2003 Dartmouth crew is a cult classic and perhaps the best film ever made about rowing. It’s all that—and much more.

I had no plan at all to row when I got to Dartmouth. I thought maybe I’ll try rugby. I walked down to the quad the first orientation day, and they had the two captains standing there with big old oars and they’re like,“Hey, freshman, you’re six-two. Come sign up.”

The next day, I went. All we did was Will’s Chief [a body circuit of calisthenics]. We did fucking Chiefs for 45 minutes. Nothing to do with rowing, no oars, nothing. And I knew immediately after the first day I loved this, because I just did something I never thought I could do. And I’m strong. Maybe I’m stronger than I thought I am. Maybe I’m more courageous than I thought I am. Maybe I’m tougher mentally than I thought that I could ever be.

And so I spent four years pursuing that. The “why” for me was not becoming the strongest physically but being the most courageous person I could every day. And that formed the identity I have now.

What I tell my staff at work and what I tell anyone I’m talking to: Life is all about choosing courage at every inflection point. I never thought when I walked on, I want to be captain, I want to have a six-minute 2K, I want to finish third at the Sprints. Like none of that stuff ran through my mind. It was just, “Holy shit, today I did something I never thought I could. What can I do tomorrow?”

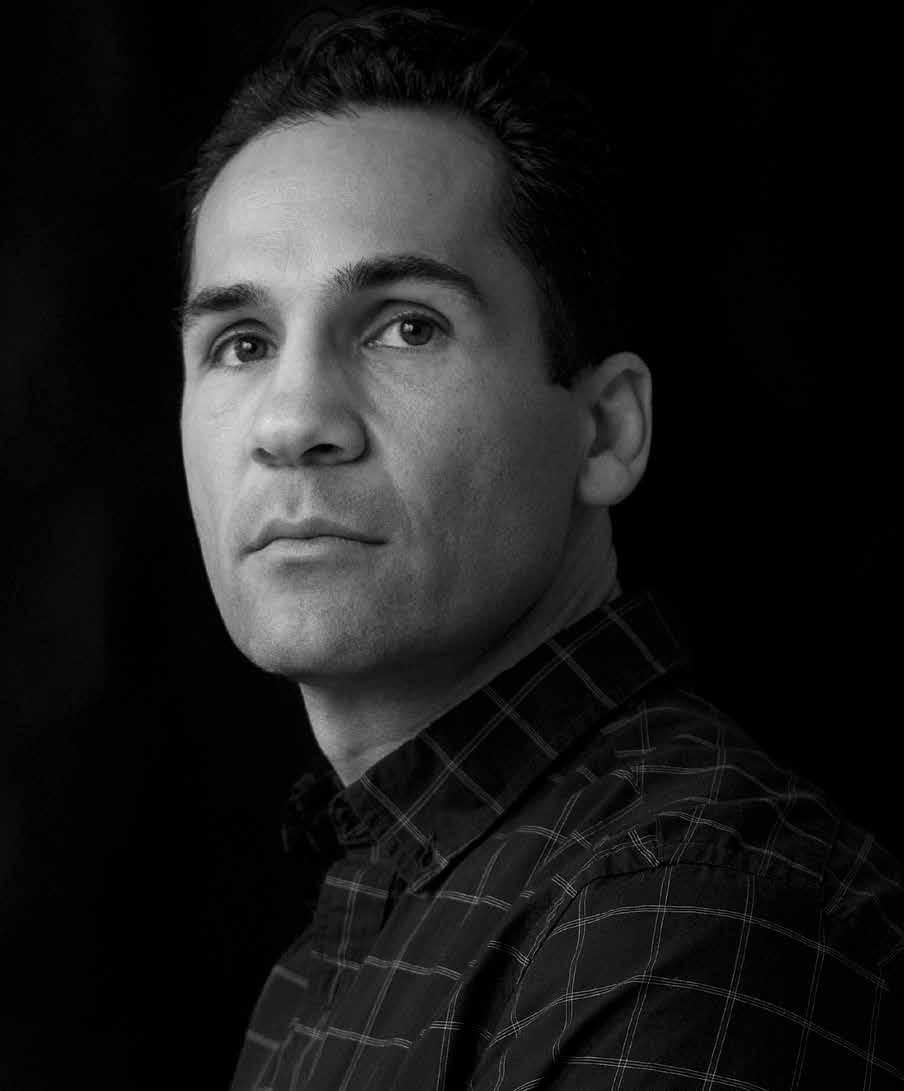

— David Shamszad Creator of Row Like Pigs

BY TOM MATLACK

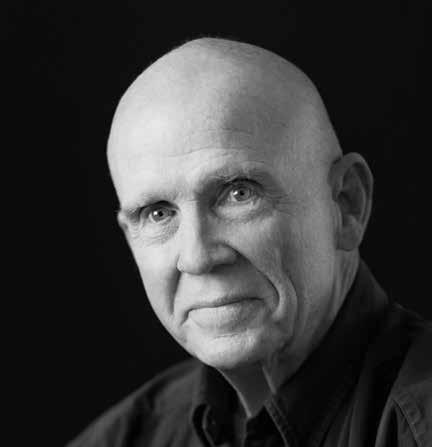

Many cultures throughout history have staged male rites of passage during which boys become men through a walkabout or killing a lion with a spear or some other potentially fatal test. Coach Will Scoggins tapped into the same need among a group of 18- and 19-year-old college boys to prove, through enduring the fire of his hell, that they were men capable of greatness on the racecourse and in life.

“I’ve committed my life to teaching young men and women about boats and oars, because it’s the only thing that has ever made sense in my life,” Scoggins said.

David Shamszad bought into that philosophy not just for the thing itself, the rowing, but for how nothing else in his life made sense, either. He bought into it to such an extent that in his junior year he made a film about it. Row Like Pigs began as a film-course assignment to make a two-minute video but has gone on to become a cult classic. Despite sweeping changes in the sport over the past 20 years, it is regarded by many as the best film ever made about rowing.

Hanover, N.H., at dawn on any given Saturday morning in January is an inhospitable place for rowing. It’s an inhospitable place for pretty much anything—dark, cold, bleak. At 8 a.m, the boathouse bay is more like the godforsaken tundra—deep snow plowed into banks outside, boats out of the way, just frigid cement and icy metal machines built for suffering, testing, and divining the true nature of a man and a team.

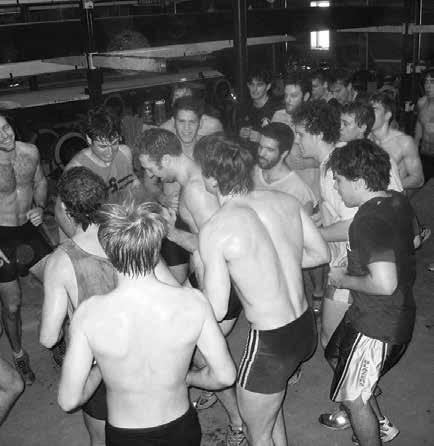

In 2003, the Dartmouth men’s crew engaged in a strange cult-like ritual called the Scoggins Circuit each Saturday morning during winter training.

This was a time when there was still freshman rowing and teams like Dartmouth were filled with walk-ons. Head coach Scott Armstrong lived too far away to come in on Saturday mornings, so freshman coach Will Scoggins had to improvise to

provide an arena for terror, joy, and human advancement for both the freshman and varsity teams all at once.

It was so important that junior Shamszad would sleep on the floor of senior Tom Schenck’s dorm room on Friday nights to ensure he was not tardy for the earlymorning sessions. Others remember entering the cave at dawn on those cold Saturday mornings with high anxiety because they knew what they were in for.

This was not the science-driven training plan of 2025. There was no real method to this madness. Just the core understanding that fast boats are built on grit, trust, and mental toughness. Saturday mornings were not a time to improve the efficiency of the stroke. Rowing telemetry by Peach Innovations—sensors on oarlocks recording power curves for each stroke made by each individual oarsman—had not yet been invented. This was a time to expand the limits of the possible. Go to the red line and keep going. Then go more. And more yet.

The traditions included shouting “I love you” to the burpees, step-ups, and one-leg presses that caused maximum suffering.

“The thing you hated most was the thing we loved the most,” recalled thensenior Jaime Velez, “until the day that as an athlete you could excel at the entire circuit—not just survive but crush each of those stations, still pushing until you’re told to stop—and realize how destroyed you are after it’s all over,”

The year before, something had been missing in Dartmouth rowing. In 2001, they won the The Ladies’ Challenge Plate at Henley Royal Regatta, and in 2002 all but one rower returned for what promised to be one of the most talented teams in program history—only to get beat all year long.

“The boat never took off, just never had chemistry,” Velez remembered. “The JV was having the time of its life beating the varsity every day in practice, which should never happen.”

Half that boat had graduated. The remaining seniors now had to face a hardcharging group of sophomores seeking to take their place. The remaining seniors got together and tried to focus on developing group chemistry. But to be successful, they would need to find the elusive X factor lacking in the prior year’s campaign. The Scoggins Circuit was a place to begin looking, testing, building not just physical strength but character as a squad.

To keep everyone moving, Scoggins had to have as many stations as rowers. The premise was easy: “Go as fucking hard as you can for a minute, then take 30 seconds to get to the next station and go as fucking hard as you can for another minute and keep going until the coach gets tired,”

Scoggins recalled.

Often, this meant going 45 minutes three times with five to 10 minutes of rest in between—or two hours and 15 minutes of hell.

The music selection was classic rock.

“They had AC/DC’s “Thunderstruck” on repeat full volume,” head coach Armstrong said. Another team favorite was Madonna’s “Like a Prayer.” Shamszad loved to dance to that while recovering between sets.

“It was loud in there,” Scoggins said. “When guys were leg-pressing, you could see people start to cheat, pushing with their arms to push their knees down.”

Cheating would get called out.

“Every guy got tested in there.”

Many members of the team recall seeing in each other’s eyes that they were fully bought in, going to the edge and well over it. Which changed them.

“You had coaches yelling and athletes yelling,” Scoggins said.

Schenck was a leader in those sessions.

“I don’t know that Schenck ever weighed 170 in his whole life,” Scoggins said. “He should have been a lightweight but he was so fucking tough that he was on the first varsity for two years. He would flip off his teammates as he booted into the trash can. That shit is just great—puking, not taking shit from these guys. That’s a big deal.”

After the Scoggins Circuit, the team would drag itself to the dining commons, where everyone else was just waking up, and then straight back to bed for a few hours of sleep to recover from the insanity— and get ready for Monday’s practice.

Row Like Pigs is a time capsule that captures the raw approach to training crews back then. As such, it stands in stark contrast to what the sport has become 22 years later.

The 2003 team was a different generation of athletes, coaches, and racing. Today’s athletes have an infinite array of training aids: thousands of rowing videos, including every significant race; multi-

episode high-production-value tutorials on national team practices; in-depth instructional videos that break down boats and races, and exhilarating coxswain recordings of big races. Every stroke they take in practice is videotaped and scrutinized.

“It’s this underground film that plenty of people have said is the best film about rowing because it captures the energy, the intensity, the guts of college rowing,” Coach Armstrong said.

Shamszad approached Armstrong at the beginning of the year and asked for permission to make the film. From that point on, the team got used to the camera being on constantly at every practice and every race. When Shamszad was rowing or working out, he would enlist a coxswain or injured oarsman riding in the launch to film.

“A friend of mine from Germany was visiting campus and took a lot of the footage in the film when it’s snowing those heavy meaty snowflakes,” senior Dirk Blum said.

“Dave was a kid who never rowed before,” Armstrong said. “He was 6-2 and 185 pounds, no superb athlete, but he made top boats because he was tough, he was gritty, and he embraced the challenge.”

“I remember seeing him in the library after all the shooting was over editing the final cut,” a teammate remembered, “because he didn’t have a computer strong enough at home.”

His parents had given Shamszad the camera, and his teammates loaned him a few bucks to buy a hard drive, film, and the rest of the equipment he needed.

Freshman rowing at Dartmouth, and rowing in general, was a war of attrition. To be great, Scoggins demanded a willingness to throw all preconceived notions about limits out the window. To face your demons square in the eye, slay those motherfuckers, and keep on going.

Everything Scoggins did to coach the freshman and set the tone for the boathouse was built on a deep, intuitive understanding of the hero’s journey throughout history, art, religion, and literature. And he drew on it all: Trojan warriors, Zen Buddhist monks, and rock-and-roll lyrics. He was as comfortable quoting the Rolling Stones as he was D.T. Suzuki.

His message was that in rowing, as in

life, we men are all trying to find our way home. There is no shortcut. Just courage. Only courage and the willingness to die on this stroke.

“Give everything, and you will receive everything,” he promised.

Scoggins was not peddling a story to his athletes; he was instilling the story. It was a slow-acting depth charge in their souls. His win-loss record as a freshman coach at Dartmouth was not the point. He created great rowers and even better men.

Shamszad still laughs about the recruits who would come to Dartmouth for the day with their dads and go for a ride in the launch with Scoggins, who terrified both the recruit and dad.

“You could see it on their faces, ‘No fucking way is my kid coming here!’”

Scoggins often talked for an hour before practice on Saturday mornings—not about rowing, not about how to get your blade in the water or release at the end of the stroke but about the existential meaning of rowing and life, quoting Suzuki and Jesus, among others, and asking his oarsmen not to shoot the arrow but become it.

It didn’t work for some—in fact, for most.

Forty rowers came out for freshman rowing in the fall of 1999. By spring, there would be nine. Sophomore year, there would be six left in the class. Four of those six would be in the varsity eight their senior year, the 2003 varsity boat on which the film focuses—one in 10 of those who had begun the process.

When Will Scoggins looked into your soul, you had to have the guts not to look away. That took a long time for most people, even the toughest athletes.

If you were to line up the medalists from last year’s Eastern Sprints or IRAs, you’d see mostly international oarsmen who have rowed for their respective countries for years, have trained scientifically at massive volumes, and who look like NBA power forwards, only more fit.

The guys at Dartmouth 20 years ago are from a different era. They are lean and long. What you see is not so much their massive muscles but the look in their eyes. They represent the soul of a sport that is more religion than recreation. Even among the contemporaries of their time, they were undersized, the underdogs who had to chop ice out of the Connecticut River

in northern New Hampshire while everyone else had been on the water for weeks.

Scott Armstrong, now the coach at the University of Minnesota, took over as head heavyweight coach at Dartmouth in 1992. In his very first year, he ran the table—going undefeated through the dualracing season, winning the Eastern Sprints and IRAs and losing to Harvard at the Cincinnati national championship by three inches.

After that, things got a lot harder.

“He had all these Olympians that underperformed through the ’90s,” one former oarsman said. “Scott brought Will in with a very specific idea in mind. And it was a smart move. They were a perfect yin and yang.”

Armstrong wanted tougher people and he knew first-hand the unique impact Scoggins could make because Scoggins had been his freshman coach when he rowed at Brown.

Armstrong was cerebral and restrained; Scoggins brought the crazy. Armstrong was the technician; Scoggins, the philosopher. Scoggins supplied the jet fuel; Scott just tried to fly the plane. The boathouse culture became Will’s culture, not Armstrong’s, which was exactly what Armstrong wanted. It was a culture that made 2003 possible.

“Scott’s the one who taught you how to row,” said Velez. “He was very even-keeled. If he got really excited, you knew he was excited. If he was pissed off, you really knew he was pissed off. He didn’t fluctuate too much. You never wanted to let him down because of how hard he worked for our program to survive and make the most of all the resources we had.”

“I had very good crews in 2001, 2002, and 2003,” Armstrong said. “The difference was that all those crews were coached by Will Scoggins as freshmen. He was a superb freshman coach, especially in terms of molding young men to eat nails for breakfast and love it. When they came to the varsity, they were ready to rock. In 2003, we had a very good sophomore class, including a very good stroke.

“Dartmouth is a lot harder place to win than Harvard and Yale, Brown and Princeton,” Armstrong reflected, echoing what many rowers have said about embracing the suck of the Scoggins Circuit, the ice, the harsh winters of New Hampshire.

“I’ve always debated if it is better to set expectations lower as a result. Is it better to

say, ‘Guys, if we do well, we might make the top six this year’ or is it better to say, ‘I think you can win it all and I want you to go for it’? I always believed in the latter because when a group embraces that—gets excited about the big dream—they feed off each other, and that’s when extraordinary things happen.”

Deep down, Armstrong believed his oarsmen were young men coming into adulthood and looking for a foundation, a philosophy of life— “like this is what I am going to be,” Armstrong said.

What the group in 2003 found at the boathouse was just that: “The idea that you can do anything if you work hard enough. You should never back down. When you face adversity, when things get hard, you double down, push even harder, and don’t give up on yourself. That is what I love most about coaching college rowing.”

In the film, Shamszad chooses to focus on three seniors—Dirk Blum, Jaime Valez, and Tom Schenck—and one sophomore, Don Wyper—central characters in making the varsity go in 2003. Schenck and Valez remain central characters in his life to this day.

One of the most unlikely was a very tall (6’ 9”), very thin German named Dirk Blum. Freshman rowing was a rude awakening. Then, he fell in love with how Scott Armstrong ran the varsity program. And by his senior year he was in the engine room of the varsity boat. Looking back now, Blum thinks of rowing as “the most impactful period in my life in terms of developing as an adult.”

When Jaime Velez, a freshman walkon, arrived in 1999, he was profoundly unfit and lacked toughness, but by the time of Row Like Pigs, he goes to the CRASH-B Sprints and makes the final against legendary Harvard rowers like the Winklevoss twins and in his senior year establishes himself as one of the best individual collegiate rowers in the country.

Tom Schenck was the emotional center of the team, or at least of the 2003 senior class, in part because his junior year was “the most miserable experience in my life.”

“The boat just never moved.”

They would be doing battle-paddle, and “for the JV, it was easy, just paddling along. And for us, it was always like lifting weights. It just sucked. Everyone was mad at each other. Everyone knew it should

have been better. No one was happy in that boat.”

After his miserable junior year, Schenck went to the U.S. National Team lightweight camp, where he did well but was cut. He came directly back to Dartmouth late that summer to continue training. A lot of his teammates were there already rowing.

“It was just a happy vibe,” he recalled.

In the fall of 2002, the vibe continued.

“The whole fall, things went well. The boats were flying.”

Don Wyper was the most talented oarsman in the 2003 boat and the leader of the insurgent sophomore class. He was a perfectionist—never satisfied, and always willing to let other people know it.

Wyper, who remembers the 2003 crew as a “special team,” has kept Row Like Pigs alive by putting it on YouTube (from which it was removed temporarily because of copyright issues with the music) and posting it on Vimeo.

“The first time we got on the water as the varsity crew in 2003,” Blum said, “the boat sang from the word go. For those of us who had experienced really bad rowing over our careers, we could sense the difference right away. We were like, ‘OK now, this is working!’”

The rowers in the varsity boat figured out right away that they had one of the fastest starts in the country.

“We thought we could beat the national team for 150 meters,” Wyper said. “We took a lot of pride in that.”

The focus became building power and speed over the course of 2,000 meters and finishing as strong as they started.

Dartmouth had not beaten Brown since 1992, a decade-long losing streak in the early-season dual race. That race was regarded by all as the bellwether of a new trajectory for the team. In 2003, the losing streak came to an end. The Big Green got out to an early lead, held on, and never felt challenged seriously.

“Beating Brown was great,” Schenck said. “Those were the little things that to us were huge because we had been a down-inthe-dumps program when I first got there.”

Dartmouth was undefeated during the dual-racing season, except for a tough race on choppy water against a very strong Wisconsin team, as they headed into the year-end championships at the Eastern Sprints.

Between the heats and finals, Blum mused to the camera about the significance of the race ahead:

“I’ve never been to a grand final before. I’m already psyched to finally, for once, go out and get a chance to row with the big boys. But any kind of trip to the medal dock for me would be just about the biggest accomplishment of my life.”

As a freshman, Blum, who hadn’t been exposed to a culture of high performance before, suffered more than anyone else, and Scoggins, the freshman coach, was happy to push guys until they broke—or made it. Schenck, his sophomore roommate, was “honestly shocked [Blum] continued rowing because Dirk had been in tears many, many times freshman year.”

Yet Blum did come back and, what’s more, embraced the Scoggins culture that pervaded the boathouse. Under Armstrong’s guidance, he learned how to row, move boats, and be tough and courageous. And here he was, on the cusp of the biggest accomplishment of his life because he came the furthest of anyone emotionally to get his shot at the awards dock. His friend Shamszad was there to capture on film what it all meant to him before the varsity went out to attempt to achieve greatness. That clip sets up everything that follows.

“We got to the thousand meters in third, and Harvard was gone, but Wisconsin was close, and we didn’t feel like there was anybody behind us challenging us. It was a super-liberating feeling, pretty darn good with what we are already likely to accomplish. Let’s go chase and see what outcome we can achieve.”

“After making the grands, we were ready to just let it rip,” senior coxswain Melissa Moody said. “We knew we belonged there. The sophomores we had at seven and stroke were two of the most poised rowers I ever was in a boat with. With them looking back at me, I was pretty damn confident we were going to have a great race. We went hard off the line as we had all season, had good rhythm, and when I saw the medal was in sight, I told the guys to take it up to a sprint early that last 500, and they responded.”

“It all came together at the Sprints,” Wyper said. “I gave everything I could possibly have given, and we had the best row we could have.”

Paddling back to the dock, everyone in the boat was ecstatic. They had done the impossible.

“I remember Harvard looking at us a little side-eyed on the dock because we were so excited about our [bronze] medal, and I did not give a shit,” Schenck said.

In the film, you watch these men celebrate on the awards dock, hugging each other, and it’s hard not to cry, because you’ve seen how far they’ve come and how their love for each other prevailed in the end.

Scoggins addressed the seniors who lost to “fucking MIT” as freshmen and were now Sprints medalists. The circle was now complete. All those Scoggins Circuits had paid off. It didn’t matter what you looked like or where you rowed. What mattered was your courage.

It gave Shamszad the perfect ending to Row Like Pigs. In the film, after the performance at Sprints, Shamszad has Schenck tell a joke about celibate priests that few viewers will understand, but the guys on the team still laugh at—you had to be there. Same goes for the film’s title, taken from a riff on commitment by the tobacco-chewing Scoggins. The mystery only enhances the movie’s appeal.

There’s growing scientific evidence that the Will Scoggins approach to making rowers wasn’t so crazy, even if it depended on moldable walk-on freshmen and would never happen now, when so many athletes are highly recruited and possess a deep knowledge of the sport and the latest training methods. College crews today train with the volume and sophistication of Olympic teams. None of them is doing the Scoggins Circuit. But maybe they should be.

Michael Easter, author of The Comfort Crisis, and Marcus Elliott, a sports medicine doctor who has worked with the New England Patriots and professional baseball and basketball players, cite numerous studies showing that toughness is not determined genetically but something that can be learned through exposure to adversity and profound discomfort. Indeed, physical limits often are more mental than physical. As an evolutionary adaptation, the mind shuts down the body to protect it well before the body reaches the limit of its capacity. Much athletic training is targeted at breaking the false governor in the mind.

Scoggins didn’t need science to tell him that. Taking a page from Navy Seals and Army rangers, he designed his training plans to select athletes with the ability to

endure and become great, training plans be damned.

“When you are two seats down with 20 strokes to go, it has nothing to do with muscle,” Scoggins exhorted his rowers. “Who wants it?”

In the end, Row Like Pigs would prove to be most important not to all the aspiring rowers who have watched and enjoyed it, or even to the teammates who were and continue to be his best friends, but to Shamszad himself. The message of the film—and what he learned making it and rowing for Scoggins and Armstrong—not only changed his life but also helped save it.

In 2003, when he made his movie, Shamszad was a junior who rowed on the JV. A year later, as a senior, he would make the IRA grand final in the varsity boat, the crowning achievement of his athletic career.

But within two years of graduating from Dartmouth, Shamszad’s life began unraveling as bipolar disorder—maddening pendulum swings between despair and euphoria that he tried to keep secret— ravaged his mind. He spent weeks in a psychiatric hospital, where he was diagnosed and medicated, after a colleague at work pried away a knife from his wrist.

“It was a nightmare,” Shamszad said. “Like being in a bad dream.”

Shamszad told Schenck and his girlfriend, but no one else. He tried to keep going but suffered terribly for a decade, during which nothing worked, and he became increasingly desperate. As depression led him through hell, he used alcohol to ease the pain.

“I was losing my mind,” Shamszad said. “Before they diagnosed me, I had never even heard of bipolar disorder.”

“He kept trying to convince me to live in Vermont and train in a pair for the national team on our own,” Schenck recalled, “like Assault on Lake Casitas style. He was looking for the purpose that rowing had offered, but neither he nor I did any rowing after college, since it was never really about the rowing anyhow. The point was the Scoggins Circuit.”

Shamszad kept drinking with abandon until his early 30s, when on the verge of dying he finally “fucking woke up,” got sober, and began dealing with his mental illness and alcoholism for the first time. He realizes now how fortunate he was; the

fighting, arrests, and countless days and nights of depression and rage hadn’t cut his life short before he had the chance to recover.

Even in his darkest days, when he had nowhere else to turn, when his life hung in the balance, Shamszad was able to draw on the lessons of his film, on his experiences with Will, Scott, Tom, Jaime, Dirk, Don, and the rest of the team. He knew he had it in him to make the change, to do the hardest thing he had ever attempted in his life. And that has made all the difference.

Without rowing and Row Like Pigs, Shamszad doubts he’d be alive today.

“The hardest thing I’ve ever done is recover, to learn how to live a healthy life— harder than any erg test or any professional pursuit. How did I learn to fight, to take a disciplined, courageous approach to mental health, to my addiction? I know I wouldn’t be here right now without rowing.”

As a walk-on, Shamszad had no idea how hard he could work, how hard he could challenge himself mentally.

“When you do something that hard that you never thought you could before, it changes you.”

Today, Shamszad is a father, husband, and founder of a successful real-estate business. He’s been sober for 13 years and recently began sharing his story with others.

“It is crazy to me now, but for the better part of two decades, even when I was sober and much better and building a cool life through tons of hard work, I just put all that in the rearview mirror out of a deeply ingrained sense of shame and a false belief about what male toughness means.”

Shamszad views his story as a way to help people beyond the cult following for his rowing documentary.

Row Like Pigs isn’t about rowing at all, Shamszad says. It’s about realizing that all of us walk around with “limitations that are just in our own fucking head.”

“The excitement is realizing that that’s all it is and that there’s a whole world out there you can participate in if you’re willing to break through those limitations.”

THE FILM AT: ROWLIKEPIGS.COM

2-layer neck gaiters will protect you throughout the seasons. Stretchguard fabric with extreme 4-way stretch for optimal comfort. Super soft, silky feel that is lightweight and breathable. 100% performance fabric, washable and reusable.

$20

PERFORMANCE FABRIC SHIRTS ALL AVAILABLE WITH YOUR TEAM LOGO AT NO EXTRA CHARGE (MINIMUM 12)

UNITED STATES ROWING UV

VAPOR LONG SLEEVE $40

WHITE/OARLOCK ON BACK

NAVY/CROSSED OARS ON BACK

RED/CROSSED OARS ON BACK

PERFORMANCE LONG SLEEVES

PERFORMANCE T-SHIRTS

PERFORMANCE TANKS

Order any 12 performance shirts, hooded sweatshirts, or sweatpants and email your logo to teamorders@rowingcatalog.com and get your items with your logo at no additional cost!

Boats that are maintained poorly and rigged incorrectly require rowers to compensate in ways that can lead to injury and bad habits that are difficult to fix later.

The days are getting longer, and the weather is getting nicer. So rowing on the water is just around the corner, and some programs have races coming up already.

During this phase, it’s imperative to make sure your equipment is ready. Place your boat on stretchers with the fin facing up. Walk along the hull and look for cracks that need to be either patched temporarily or repaired professionally.

Wiggle the fin to check that it’s secured in its box. Turn the boat over so you can inspect the inside—the slides, seats, foot stretchers, and shoes. Some of them may need to be replaced, cleaned, tightened, or oiled. Check all rigger bolts,

clean the oarlocks, and oil the oarlock bushings on the pin. If the boat has steering, make sure everything is secure and adjusted properly.

Next, measure all the rigging settings, the angle and height of the foot stretchers, the pitch and height of the oarlocks and the span. Rig the boat with measurements for the initial phase of the season. It’s annoying to row for the first time and find that your boat is set up incorrectly.

Check your oars. Clean the sleeves and look for cracks and scratches on the shafts and blades that could affect function. Wear and tear of the sleeve as well as sunlight can change the pitch of the blade and lead to technical problems.

It’s important to check the pitch of the blade relative to the flat face of the sleeve. Adjusting blade pitch correctly requires effort and some expertise, but oar manufacturers provide instructions on their websites.

Many technical problems stem from poor equipment. Better to set up your gear properly than to experience the frustration of not being able to train fully and properly. Boats that are maintained poorly and rigged incorrectly require rowers to compensate in ways that can lead to injury and bad habits that are difficult to fix later.

Once your rowing equipment is in order, you’re ready as soon as the weather

breaks for a spin on the water. As with any new exercise, begin with low intensity and short duration. Remember that your hands must adapt to shear forces different from those on the ergometer because of grip material, rotation while squaring and feathering, and, of course, grip. You cannot change the required rotation of

Only when your hands, technique, and conditioning are stabilized should you undertake high-intensity pieces.

the handles, but switching from shorter to longer training sessions as well as clean handles and a loose grip will help.

The same principle of progression applies to training intensity and stroke rate. Introduce power and stroke-rate increments slowly. If you need to prepare for early competition, begin with intervals of 10 hard strokes at a moderate stroke rate followed by two minutes of light endurance work. Increase your stroke rate to a long-distance pace before increasing the number of hard strokes. This process may take a few weeks.

Only when your hands, technique, and conditioning are stabilized should you undertake high-intensity pieces. Rowers should exhibit solid technique and strong cadence before doing exhausting workouts. When a training plan is conceived well, boats get faster and maintain speed longer. If rowers stay motivated and healthy, patience will pay off in the long run. Use your first races as practice opportunities and analyze them to adjust your training plan.

Early in the season, don’t be afraid to take a day off or train differently if you’re having trouble recovering or experiencing aches and pains. When athletes have time to recover fully, they’ll return to the water with renewed enthusiasm that will show in performance.

VOLKER NOLTE, an internationally recognized expert on the biomechanics of rowing, is the author of Rowing Science, Rowing Faster, and Masters Rowing. He’s a retired professor of biomechanics at the University of Western Ontario, where he coached the men’s rowing team to three Canadian national titles.

COXING

Anxiety is normal and means your brain and body realize that racing is important. Understanding the processes behind nerves can help you stay grounded instead of spiraling.

The beginning of the spring racing season means it’s time to talk about something that plagues so many coxswains on race day. It’s your moment. You’ve prepared, and your crew is ready to go. You’re also so nervous you’re uncomfortable.

This is normal.

“Everyone who is performing has some common experiences, which is that their nervous system gets activated in anticipation of the ‘big moment,’” said Emily Saul, a sport-psychology coach, owner of E Saul Movement, and a former Division I rower.

“This basic and essential part of our brain and brain-body integrated system creates the sensation of ‘nerves’ or the common symptoms of anxiety. This is normal, and while it can feel distracting, uncomfortable, and undesirable sometimes, it’s not a bad thing.”

What you tell yourself about this feeling makes a difference. All of us have heard the advice to think of the nerves as excitement, not anxiety, but that’s easier said than done.

“One key practice is to notice these sensations in the body and label them as a normal response to something important happening,” Saul said. “Noticing and interpreting these experiences as ‘this is my body doing a good job being ready for the important thing’ is way more helpful than interpreting them as signals of danger or of something being ‘wrong’ with you.”

Your nerves show that your brain and body understand that racing is important, and that it’s important to you. Remembering that and understanding some of the physical and psychological processes behind nerves can help you stay grounded instead of spiraling.

A helpful metaphor is stroke rate, Saul said.

“In the human body, we need a certain amount of what’s called psychological arousal or internal activation to perform in an optimal way. Too little internal activation and the person will not be engaged enough. Too much internal activation and the person will become overwhelmed, skills will break down, and it’s as if they lose the ability to perform the tasks they’ve done many times before.”

Think of calibrating your raceday nerves into an optimal range. You wouldn’t want to race at steady-state pace, so some nerves are appropriate. You should try to stay in an effective range so you’re not spinning your wheels and panicking.

One way to help find the appropriate level of activation is to build a solid raceday routine so strong habits support you if and when your anxiety surges.

“Build a routine that you practice during practice sessions and repeat many times so that on race day you’re relying on something familiar, comfortable, and trusted,” Saul said.

For the routine, focus on what you can control. Eat well so your brain has plenty of fuel, get adequate sleep on the days leading up to race day, and make sure you’re dressed appropriately for the weather.

The day before racing, make a packing list and get your items together, even if it’s a home race. It will be comforting to know that when you wake up in the morning, your uniform is ready to go and your CoxBox charged.

If your coach doesn’t provide a raceday schedule, make it yourself and make it detailed, from arrival time to when you begin the warm-up to hands-on. Make sure to build in enough time for all the realities of race day (e.g., the wait in the Porta Potty line) so that you can stay on target.

Leading up to a race, time your warm-up a few times with your crew. That way, you’ll have a sense on race day of how long your warm-up takes without the interruptions of a 2K course. Write down your schedule and keep it handy so you can refer to it easily. Know your race time, your lanes, and your opponents. If you feel nerves rising, you can reassure yourself that the things you need are in place.

What if you’ve prepared and your anxiety still is surging? Take a moment to access the internal stroke-rate dial Saul mentioned.

“Access to this dial of internal activation is found most easily by influencing the sensory information going into your body,” Saul said.

Sights, sounds, and even smells and tastes can be helpful in keeping yourself grounded and in the moment if you feel your nerves beginning to spin out of control.

“Simply bringing your attention to your breath can help tune out external stimulation that might be overwhelming,” Saul said. “Look at the water, a skyline, a cloud, or something that’s calming to see. Feel the texture, weight, or contact of something”—your team jacket or your headset.

Do some introspection on what grounds you. What do you need on race day? Maybe your rowers need to get pumped up to go but maybe you need to listen to some relaxing music on the team bus. Extra hands are always needed on race day, so if you find yourself getting anxious when you’re waiting for racing, you can ground yourself by putting yourself to work. Carry shoes for other crews launching, double- and triple-check your rigging, wipe down your boat, and straighten up the trailer area.

Every race is a learning experience, and with each experience your nerves will ease. I always felt a great moment of relief when we shoved off the dock finally to start our race warm-up. My teammates and I were there together, and it was time to begin the fun.

Helping rowers worldwide get scholorships

Helping high school rowers and families navigate the university recruiting process- Coaches and parent groups reach out to us!

Robbie Consulting will meet your team, coaches and parents at your home club or school. Go to www. robbieconsulting.com to get in touch and schedule a visit

“His assistance was essential to get prepared for such a big step and to get to know the school and team I would compete for.”

Find a program where you connect with the athletes and coaches. A negative team culture can dampen not only your rowing experience but also your entire university journey.

Rowers often debate whether stroke styles or training methods should influence their choice of a college program. Just as football players select teams based on offensive or defensive strategies, should rowers and coxswains adopt a similar approach?

The answer is both yes and no.

Training philosophies vary widely among rowing programs. Some emphasize high mileage with low intensity, while others prioritize shorter high-intensity sessions. Strength training may be a cornerstone for certain teams but less emphasized in others. Understanding these distinctions can help athletes choose programs that align with their strengths and long-term goals.

Rowing styles also differ, particularly in sweep rowing. Young athletes adapt quickly typically to a university coach’s technical approach, however, and in my experience, it’s rare for a rower’s previous stroke style to limit his or her ability to transition into a new system. College coaches often blend

team styles seamlessly during the first few weeks of practice.

While training methods and rowing styles are worth considering, they shouldn’t be the deciding factor. The most critical aspect of choosing a rowing program is its culture.

Find a program where you connect with the athletes, coaches, and overall environment. A negative team culture can dampen not only your rowing experience but also your entire university journey. Conversely, a supportive and positive culture fosters both personal and athletic growth.

At its core, collegiate rowing is about more than just improving speed on the water; it’s about joining a community where you can thrive as a student-athlete. Prioritize finding the right cultural fit, and everything else will fall into place.

Some rowers worry that they’re eating too much. Others wonder whether they’re eating too little. Both groups feel frustrated that their bodies defy their attempts to shed fat.

As a sports nutritionist, I spend too many counseling hours resolving weight concerns of athletes, including rowers. Females and males alike come to me trying to figure out how to lose weight. The “eat less and move more” paradigm doesn’t always work. Weight is more than a matter of willpower. Despite restricting their food intake, some rowers aren’t losing weight. They ask whether they’re eating too much. Others wonder whether they can’t lose weight because they’re eating too little. Both groups feel frustrated that their bodies defy their attempts to shed fat.

Rowers who under-eat can be experiencing Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs). Relative energy deficiency occurs when an athlete eats well but not enough to support normal body functions and the demands of exercise. REDs is a constellation of symptoms (eating disorders/ disordered eating, stress fractures, low libido [men], amenorrhea [women], depression, hormonal imbalance, and altered metabolism that can impair overall health and performance.

Despite consuming 2,500 calories a day, a female rower can still have an energy (calorie) deficit relative to how much fuel her body actually requires. Over the long term, this Low Energy Availability (LEA) contributes to the symptoms associated with REDs.

• Rowers can be in a state of low-energy availability and still remain weight-stable despite having undesired body fat. They become frustrated by the persistence of fat

even though they’re working hard to slim down. Said one rower: “I should be pencilthin by now for all the exercise I do.”

• The body does an amazing job of conserving energy and curbing fat loss when food is scarce. Signs of energy conservation include chronically cold hands and feet, irregular or no menstrual period in women, low libido with no morning erection in men. Other signs of LEA: constant food thoughts (e.g., finishing one meal only to begin thinking about the next), trouble concentrating, and poor sleep.

• LEA can happen unintentionally because of lack of nutrition knowledge about how much an athlete “deserves” to eat. Because we live in a “food is fattening” culture, hefty meals often get scrutinized negatively (“you’re really going to eat that much food?”).

• Female rowers commonly need more than 2,800 calories a day and males more than 3,000, depending on body size and training hours. Selecting this amount of food can become a daunting challenge without a structured food plan, particularly for rowers who “eat healthy” (i.e., no added sugar, fat, or “fun foods”). They can fail to consume enough calories because a highquality diet (lean protein, fiber-rich veggies, whole grains, and fruits) is filling and curbs the appetite. Suggestion: Eat more

nuts, olive oil, and even some fun foods. A reasonable target is 85 to 90 percent quality calories and 10 to 15 percent fun foods. Yes, when you need a lot of calories, it’s OK to plan in a few sweets and treats!

• LEA also happens with intentional food restriction, such as dieting, disordered eating, and eating disorders. Other barriers to increasing food intake are lack of time to prepare/eat the food as well as lack of money to buy the food. Chronic food restriction means reduced consumption of not just calories but also vitamins, minerals, protein, and bioactive compounds that promote a strong immune system, health, and performance. LEA can lead to yet another injury and ruin an athlete’s career. Recovery from chronic LEA can take months (to regain menstrual rhythm) and years (to restore lost bone-mineral density).