Pandemic Lessons from THE Global South

Contributors :Prof.JaimeHernández-García

ElisaSutanudjaja

RedentoB.Recio

AdriannaMarin-toro

VidyaTanny

DindaAlshauma

Layout :VidyaTanny

DindaAlshauma

Editor :DianTriIrawaty

Notforsale

RujakCenterforUrbanStudies

2023

Incollaborationwith:

Global South is a regional categorization term developed from interestingdebatesbydiversescientificgroups,includinggeography, politics, sociology, and postcolonial studies. The definition of the GlobalSoutharticulatesgeographicallocationandmanyotherpoints ofview,aspreviouslymentioned.

Therefore,theGlobalSouthdoesnotreferto aspecificlistofcountries,groups,orcountries because it is much more dynamic and complex than the terms that have previously existed. However, according to Mahler (2017 and 2018 Clarke, 2018), at least the Global South has three primary definitions, which debate continues in many circles, especially amongexpertsandactivists.

14,158,573

42,34

First, defining the Global South descriptively; refers to countries classified by the World Bank as lower-middle income in Africa, Asia, Oceania, Latin America, and the Caribbean. Experts and activists commonly use this term to provide a lens for unifying diverse economic,social,andpoliticalpositionsintooneoverarchingcategory (Clarke, 2018). This extends the list of previously existing concepts to classify'poorerpartsoftheworld.

Global South is also used for areas where globalisation negatively impacts people, including poorer areas within rich countries. The expression can describe the second definition, "there is South in geographicNorthandNorthingeographicSouth"(Mahler,2018).

Thethirddefinitiongoesbeyondthegeographiccontextinwhichthe Global South refers to protests against theft/grabbing of common property, against the theft of human dignity and rights, and the destruction of democratic institutions (Prashad, 2012 in Sajed, 2020). This definition is so much more analytical that it is often associated with research focusing on power and economic disparities in ways beyond the nation-state as its unit of comparative analysis. The struggles of marginalized groups – such as farmers, landless and homelessgroups,indigenouspeoples,andinformalworkers–canbe exploredunderthisanalyticalumbrella.

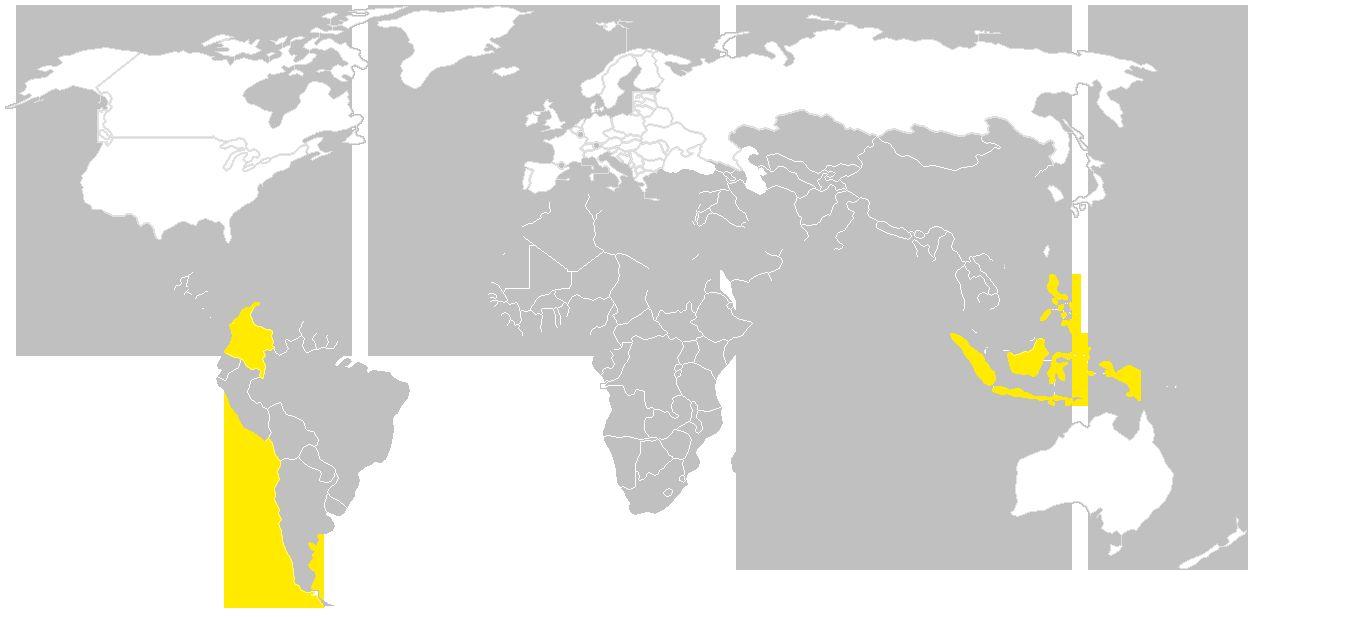

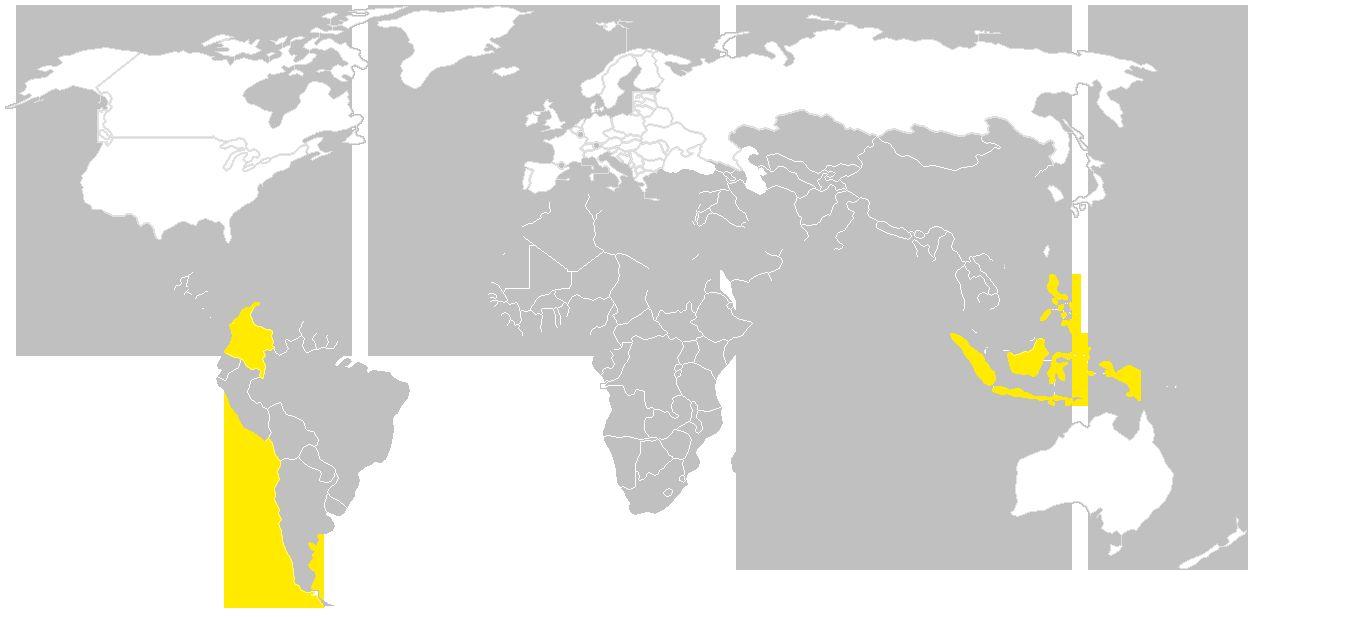

All three are relevant to the intent of Global South in this booklet. This booklet attempts to record and compile initiatives, especially solidarity responses, from various communities in the four Global South countries to maintain their viability in facing the social and economiccrisisdescribedearlier–whichwasthenexacerbatedand clarifiedbythedepravityoftheCOVID-19pandemic.

Clarke,Marlea.(2018).GlobalSouth:whatdoesitmeanandwhyusetheterm?. Available online: https://onlineacademiccommunity.uvic.ca/globalsouthpolitics/2018/08/08/global-sou th-what-does-it-mean-and-why-use-the-term/

Mahler,AnneGarland.(2018).FromtheTricontinentaltotheGlobalSouth:Race, Radicalism,andTransnationalSolidarity.Durham:DukeUniversityPress.

Sajed,Alina.(2020).FromtheThirdWorldtotheGlobalSouth.Availableonline: https://www.e-ir.info/2020/07/27/from-the-third-world-to-the-global-south/

The major cities of the Global South have been locations with an alarming number of cases during the two years of the pandemic. Restrictionsonlarge-scaleactivitiesaffectdailyincomeresidentssuch as street vendors, domestic helpers, or informal transport operations. The decline in welfare also increased because many formal workers were laid off and lost their livelihoods. This condition shows that COVID-19 goes far beyond a health emergency crisis but also reveals and deepens the impact of long-standing inequalities, showing inadequacies in employment, basic services such as health and education,andsocio-economicassistance.

TheblowofthepandemicisfeltdifferentlyintheGlobalSouththanin thecountriesofthe'north.'Asaworldregionwithahistoryofbeing disadvantagedbyglobalisationandcapitalism.Theresources inthesecountriesarenotaswellpreparedasthoseof the'northern'countriesinensuringtheirpeople's health,food,andsocialsecurity.However,how theGlobalSouthrespondsissomethingwecan alwayslearn.Southernnationsareknownas 'resistant'andcansurviveontheirterms.They survivednotonlybyindustrialpowerbut alsobysocietalresistance.Thepandemic isanopportunitytostrengthenthe resistancefromtheGlobalSouthdifferently.

Thisbookletrecordsthecollectiveeffortsof solidaritypracticesinmanyaspectsaffectedby thepandemicin4majorcitiesoftheGlobal South,Santiago(Chile),Manila(Philippines),Jakarta (Indonesia),andBogota(Colombia),through4essays thatcanbeenjoyedeasily.

The four available essays do not offer an objective comparison but emphasize the researchers' in-depth observations of the pandemic response in their respective countries. The pandemic in Chile exposed the underlying housing problems that led to mass evictions. Revealed by looking at the impact of the "stay at home" policy during the pandemic. Moreover, Bogota shows how the pandemic impacts the most vulnerablecommunitiesinmanyotheraspectsbesides housing, namely decreased income, health, and food security. Ang how this condition creates forms of 'resistance' efforts as a response from society. In Asia, Jakarta shows us how the informal economy tries to copetogetherbyshowingasolidarityresponse.Thisis a stark contrast to the efforts of large platforms in profit relationships with small businesses. Moreover, from Manila, we learn that many self-help and self-organization initiatives rooted in compassion occurredduringthestruggleofthepandemicandfilled thegapsingovernmentresponsibility.

This collection of essays was produced from an International Webinar entitled “COVID-19 and Global South Solidarity : SOLIDARITY, RESISTANCE & RESILIENCE”,whichwasheldinMay2021.TheWebinar brought together practitioners, academics and researchersfromfourmetropolitancitiesoftheGlobal South to exchange views and share the findings—because they are valuable for Global South countries to understand various forms of response to crises, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. This shortnarrativeunderscorestheimportanceofbuilding solidarity and sustaining resistance as cities face the ongoing crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic and explores post-pandemicrecoverystrategies.

JaimeHernández-García

ProfessoratSchoolofArchitectureandDesign

PontificiaUniversidadJaveriana

Contacts:hernandez.j@javeriana.edu.co

ElisaSutanudjaja

ExecutiveDirector

RujakCenterforUrbanStudies(RCUS), Indonesia

Contacts:elisa@rujak.org

InformalUrbanismResearchHub FacultyofArchitecture,Building andPlanning

TheUniversityofMelbourne

Contacts:rrecio@unimelb.edu.au

AdrianaMarín-Toro, PhDstudentatFacultyofArchitecture andUrbanism,UniversidadedeSãoPaul, andResearcheratLabCidade,Brazil

Contacts:adriana.marin@usp.br

Taking the case of Chile, I will use some examples of how pre pandemic conditions in housing are placed under pressure in the pandemic circumstances. Housing and specifically “stay at home”, is important because it is part of an effective technique for reducing risksindiseasessuchasCOVID-19,characterizedbyitssignificantlevel ofcontagion,andalsobecauseit'sabasichumanrightandthereare rightsrelatedtohousingthathavebeenoverlookedinthispandemic time.

2020 and 2021 it has been two tough years for many individuals and familiesaroundtheworld,evenapersonalandasocialcatastrophe.In Chile the crisis starts a little before, on October 2019, with a huge protestagainsttheeconomyandpoliticalsystem.Alloverthecountry therewerepublicexpressionofsocialdiscontentviathe“cacerolazos” (pot-banging) and gatherings in public plazas and on major throughways, while looting of supermarkets and pharmacies multiplied(Garcés,2019).

Then the coronavirus pandemic came and exacerbated the political and social crisis that Chile was going through, there was now health and economic crisis as well. The pandemic deepened the wounds causedbyeconomicinequality.Lockdowns,illnessandunemployment broughtbyCOVID-19meantthatalotofpeoplecouldnotmeettheir basicneeds(Apablaza,2021).

Chile is known as a laboratory where researchers can analyze the processofdevelopingneoliberalpolicies(Hidalgo,Santana-Rivas,Link, 2018). These policies were established between the late 1970s and early 1980s, during a period of military dictatorship (1973-1990) by Augusto Pinochet. This country has been an example for other countriesandcitiesoftheglobalSouth,especiallyinLatinAmerica,on varioustypesofpolicies,includinghousing.

Looking from the macroeconomic perspective, Chile is a model country with a highest GDP per capita compared to other Latin American countries like Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru. It has considerably better development indicators, like poverty rate, access tobasicsanitation,accesstodrinkingwater.

Althoughithasanimportantinformalsector,itisalsolowerthanthe other mentioned countries (Benítez, Velasco, Sequeira, et al., 2020). Yet,Chilehasasignificantlevelofinequality,asmostLatinAmerican countries.

Figure1.1 SocialUprisinginChile, Imagesource:SusanaHidalgo,2019

Specifically on housing, the possession of a residential property in Chile has played a much more relevant political role than in other European and North American countries, particularly in low-income groups.IntheChileancontext,wehavecalleditthe“ethosofhome ownership” (Marín-Toro, 2017), referring to a set of fundamental customsandhabits,ininstitutionsandculture,includingvalues,ideas orbeliefslinkedtohomeownership.

From the end of the 70s and early 80s, there was a construction of the idea "dream of your own home". And the promotion of private propertywasusingfinancialmechanisms(Hidalgo,etal.,2018)like:

● Subsidizationofdemand;

● Mortgagestradedinthesecondarymarketandthebuildingofa public-privatemarketforcheaphousing;

● Policiesfavoredthedisplacementofthosewhocouldnotafford houses (through settlement eradication programs), to the peripheriesofthemetropolis.

Chileansocialhousingpolicywasconsideredasuccess.Themassive housing production has managed to reduce housing deficit, and manyLatinAmericangovernmentsareimitatingthefinancialmodel. This policy was imported to other Latin American countries (Ducci, 2002) like Mexico, Guatemala, Bolivia, Ecuador, Brazil, El Salvador, Colombia,Venezuela(Rolnik,2019).

However,this“successfulpolicy”hasendedupcreatingnewurban andsocialproblems:Chileanhousingpolicyexposesproblemsof location,allocativeefficiencyandtargeting,ghettoization, designandconstructioninadequacies,segregation, fragmentation,insecurity,overcrowding.The quantitativeapproachneglectedqualitative aspectssuchassocialintegration,health conditions,educationalachievements, identity,andsenseofbelonging.

Until2007,therequirementstobuildsocialhousingwereminimal.Itis estimated that there are more than a million houses that must be repaired, also they have poor thermal conditions and overcrowding, whichcontributestothespreadofdiseases,suchasCOVID-19.Today, there are subsidies to improve the quality of these homes. But the scope is so limited that it would take us "more than a century" to reachthosewhoneedit(Pávez,Barraza,Durán,etal.,2020).

Overcrowding and poor-quality housing are not recent problems, but they havebecomecriticalin pandemic contexts. International literature has shown that the quality of the materiality of homes is key to generating appropriate indoor environmental conditions to combat the emergence of diseases.

The informal settlements, called “campamentos”, start to grow significantlyin2019.Thisgrowthisstronglylinkedtowhathappened in2019andtheactualyearsofpandemicperiod;50%ofthefamilies that come to live in “campamentos” are families that declare economic or labor reasons, either because they lost their job, their incomedroppedorthepriceoftheirrentwentup(TECHO,2021).

The paradox is that this accelerated increase in ‘land seizures’ occurred quietly. While most of the Chilean people have been able to stay at home, another part of the population has been forced to leave it and build a new one. They were those who lost their jobs during the pandemic, for whom the savings or state aid were not enough.

Many of them did not have support networks or ended up finding them in these communities, like solidarity spaces, communities that organize themselves in the construction of houses. Here, communities of Chilean people coexist with families from Haiti, Colombia,Venezuela,BoliviaandPeru.

Figure1.2Anexampleofsocial housinginChile, Imagesource:LuzMaríaVergara,2016

Figure1.2Anexampleofsocial housinginChile, Imagesource:LuzMaríaVergara,2016

Apablaza,M.(2021).Theresurgenceof“OllasComunes”inChile:Solidarityintimesofpandemic. Danish Development Research Network (DDRN) . Available online: https://ddrn.dk/the-resurgence-of-ollas-comunes-in-chile-solidarity-in-times-of-pandemic/

Benítez, M. A., Velasco, C., Sequeira, A. R., Henríquez, J., Menezes, F. M., & Paolucci, F. (2020). Responses to COVID-19 in five Latin American countries. Health Policy and Technology . DOI:10.1016/j.hlpt.2020.08.014

Ducci,M.E.(2000).Chile:thedarksideofasuccessfulhousingpolicy,inJosephS.TulchinyAllison M. Garland (eds.)SocialDevelopmentinLatinAmerica:ThePoliticsofReform . Washington, DC, Boulder,WoodrowWilsonCenter/LynneRiennerPublishers,2000,pp.149-174.

Garcés, M. (2020): October 2019: Social uprising in neoliberal Chile. JournalofLatinAmerican CulturalStudies,DOI:10.1080/13569325.2019.1696289

Harvey, D. (2020). Anti-Capitalist Politics in the Time of COVID-19. Available on line: http://davidharvey.org/2020/03/anti-capitalist-politics-in-the-time-of-covid-19/

Hidalgo, R.; Santana-Rivas, D. & Link, F. (2018): New neoliberal public housing policies: between centrality discourse and peripheralization practices in Santiago, Chile. Housing Studies, DOI: 10.1080/02673037.2018.1458287

Marín-Toro,A.(2017).Paradojadelaviviendaenarriendo:arraigoyvulnerabilidadresidencialenel barrioPuertodeValparaíso,Chile.México:PUEC-UNAM/INFONAVIT.ISBN:9786070290848

Pávez, J.; Barraza, C.; Durán, C.; Medina, G.; Rivera, M.I. & De la Barra, F. Frío, contaminación y hacinamiento: un millón de viviendas sociales con fallas que facilitan la expansión del COVID-19. CIPER Académico. Available on line: https://www.ciperchile.cl/2020/11/12/frio-contaminacion-y-hacinamiento-un-millon-de-viviendas-s ociales-con-fallas-que-facilitan-la-expansion-del-covid-19/

Rodríguez,A.&Sugranyes,A.(2004).Elproblemadeviviendadelos"contecho".EURE(Santiago . DOI:10.4067/S0250-71612004009100004

Rolnik,R.(2019).UrbanWarfare:HousingundertheEmpireofFinance,London,Verso.ISBN:978178 8731607

TECHO(2021).CatastroCampamentos2020-2021:Másde81milfamiliasvivenencampamentosen Chile. Available online: https://www.techo.org/chile/techo-al-dia/informate/catastro-campamentos-2020-2021-mas-de-81mil-familias-viven-en-campamentos-en-chile/

It´s true there exist natural and environmental catastrophes, or pandemics,thatarenotunderourcontrol,orarebeyondourcontrol. It is a fact that viruses mutate, and we don´t have any control over that, but: “… the circumstances in which a mutation becomes life-threateningdependonhumanactions”;(Harvey,2020);andwhen we talk about human actions, we are talking about the role of the State,publicpoliciesandalsotheacademyandthecommunity.When aresponsibilitybecomescollectiveandnotindividualinhowweface apandemicconditionoranyothercircumstanceofcatastrophe.

Figure 1.3

Figure 1.3

Thisessayofferssomereflectionsabouttheimpacts of Covid-19 in informal settlements in Bogotá, and the way communities face the consequences with resistance and proposals. The text focuses on two communityinitiatives:HuertopíaandSurvamos,with urban agriculture the first and street art the second, contributingnotonlyintermsofprovidingassistance to their communities, but also as a political statement to get visibility and report the abandonmentofthegovernment.

Covid19hasbadlyhitColombia.AfterBrazilandMexico,Colombiais the worst affected country in Latin America. The country finished June with more than 4 million confirmed cases and more than 100,000 deaths. From these numbers, one third approximately correspondtoBogotá.Bogotáhas643.2activecasesofCovid-19per 100,000inhabitantsandamortalityrateinmenof324.6per100,000 and in women of 169.5 per 100,000. When comparing Bogotá with Miami, New York, Madrid, London and major Latin American cities, theColombiancapitalranksfifthintermsofthenumberofcasesper millioninhabitants(114,897).

On top of this, the country is experimenting a social outburst since April 28th, that is taking hundreds of people to the streets. And although the strike is a truly demonstration of disapproval of social andeconomicpolicies,itispromotingpeopleagglomerations,apart fromviolenceandhumanrightabuses.

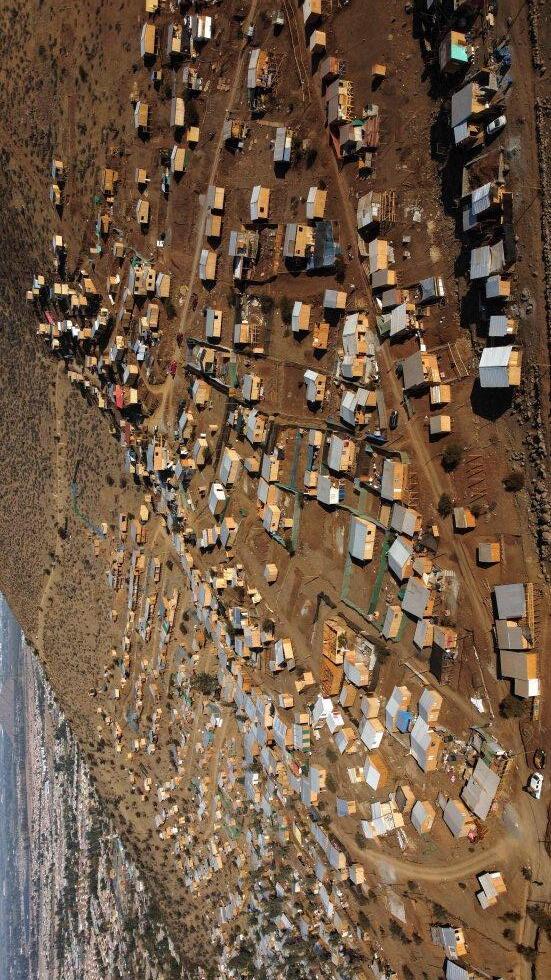

The city in Latin America has been greatly developed by informal urbanisation. Informal settlements are today a consistent feature of Bogotá (see Figure 1). More than 50% of the city have grown from somekindofinformalpattern(urbanand/orhousingdevelopment), andnearly25%ofBogotá’sareaiscoveredbylandthatisoccupied informally or ‘illegally’ – as it is described in urban policies (Hernández-García,2016).

TheUnitedNations(UNCHS,2003,2015)definesinformalsettlements asthosethatdonotcomplywithplanningandbuildingregulations, i.e.thatusuallylackbasicservicesandinfrastructures.

However,thisviewhasbeencriticisedforbeingdeprecatoryandfor not recognising the positive characteristics of such neighbourhoods (Gilbert, 2007; Robinson 2006). These settlements have been configuratedespeciallyfrommigratoryprocesses;manycomingfrom ruralareaslookingforbettereconomicopportunitiesinthecity,and others as a result of the armed conflict since around 1950s. The characteristicsofsocial,economicandhealthvulnerabilityofinformal settlements exposes them disproportionately to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Collective action has been the way most of these areas have used to self-develop themselves, as the same as facingtheCOVID-19.

Conditions within informal settlements exacerbate exposure to the multipleimpactsofthepandemic.Thekeyenduringfeaturesinclude historical stigma, low incomes, restricted accessibility, high risks, climatechangehazards,limitedservicesandinfrastructure(i.e.water, sanitation, electricity, information and communications technologies [ICTs], waste), high residential densities, limited access to health services,andinsecurityoftenure(Duqueetal.,2020).

Following Duque et al. 2020, the pandemic has impacted the living conditions in informal settlements in several ways, in addition to the alreadydifficultsituationofthepeoplelivingintheseareas:

➔ Housing: being the front line of defense to Covid, the first self-care measure is to stay at home. Tenure, overcrowding, and quality are major issues. Lack of property titles aggravate the eviction risk, potentially to put families in the streets. But overcrowding andlackofqualityarealsoabigrisk,particularlybecausefamilies needtobeinsidethehouseformoretimethatusedto,andthe risk to contagious but also of lack of proper conditions become higher.

➔ Income: withrestrictionstobeinginthestreets,informallabourbecome impossible, affecting the earnings of low-income families. This posesabigchallengeforthem:beingathomeavoidingtherisk tocontagiousinthestreetsbutwithnoincomeandnofoodor getting out the house to get some income and food but risking life.

➔ Food security: connected to the earlier issues, access to food poses a great challengetolow-incomefamilies.

➔ Health: health insurances are not enough forlow-incomefamilies,andsocial health systems are also scarce. At the same time, health systems are collapsing and getting on time physical and or mental care becomemoredifficult.

The government has enforced policies and programmes to address thepandemic,intermsofbiosafetyandeconomicsupport,especially forvulnerablecommunitiesincludingurbaninformalsettlersarepart; however,theyarenotenough.Initialmeasurementsincludedcurfews, lockdownsandrestrictingpeoplefromthestreets.Atthesametime, food was distributed to low-income families by the municipality and by the civil society. After a few months, more medium-term policies were put in place, such as the solidarity subsidy and guaranteeing a basic income. This last one is being discussed at the moment to becomeapermanentpolicy.Nowadaysvaccinationisanothertoolto facethepandemic,butatthemoment(June2021)onlyabout20%of thepopulationhavebeenimmunized,whileatthesametime,asseen before,contagiousratesanddeathtollsareontherise.

Initial policies of social isolation affected low-income families’ dependence on informal economic activities, as the majority of the populationlivingininformalsettlementdependsonstreetseveryday work and earnings. And lockdowns exposed them, to two dramatic risks: on the one hand, insufficient means to survive; on the other hand,theirhealth,theirfamiliesandtheircommunities.

Lockdownsexposedthemtotwo dramaticrisks: insufficientmeanstosurviveand thehealthoftheirfamiliesand theircommunities.

People in informal settlement have not just wait for government's policies and programmes, that have been limited in terms of resourcesbutalsoincoveringallthein-needpopulation.Inresponse, communities have organised themselves to help their own communities, based on their tradition of community empowerment and self-organisation to overcome the lack of institutional presence intheirterritories.Twoinitiativesarediscussedbelow.

Huertopía is a community organization that has been working for several years to help people with gardening by providing technical advice,seedsandseedlings(seeFigure2.2).Theworkfocusesonthe informally developed area of Alto Fucha, along the river Fucha, on theEasternHillsofBogotá.

“Whatwedoisnotjusturbanagroecology,ithasthreedimensions: environmental, political and economic.” With these words Jhody Sanchez, one of the leaders of Huertopía, describes the work they do. And it is important to highlight that it is not just about urban agricultureandtheenvironmentandeconomicgains,it’sverymuch aboutapoliticalstatement.Inthissense,Huertopíaisalsoinvolved inmanyothersocialandcommunityactivitiesinthearea,usingtheir visibilityandtheactivism.

And Jhody continues: “The community was very affected by the pandemic. Neither the national nor the local government guaranteed free food or public services during the pandemic. If peoplecannotaccessajob,whatcantheyliveon?".

Inhereshegivesaclearpictureofthesituationintermsoffoodand attentionofmostinformalareas ofthecity,implyingthattheyneed to cater for themselves but claiming responsibility from the government. And she adds: "We feel that we are in charge of a responsibility that should be assumed by the state. There is an institutionalbarrierthatsometimeshindersthings,becausewedoit from the community and they see everything as a problem.There is nodialoguebetweenthedistrictgovernmentandus".

Another initiative that Huertopía has been working on during the pandemicistheSolidarityEconomyNetwork.Ninety-fivepercentof thenetworkismadeupoflocalwomenwhometduringlockdowns

Six young urban artists met in 2013 and started making graffiti in CiudadBolivar(majorinformalsettlementsarea)aimingtogenerate identity in their territory and to raise their voices in the face of environmental damage and crime. In times of the pandemic, Survamos, the collective founded by youngsters, continued doing their artistic interventions, seeking to counteract dynamics, particularly social and economic discrimination, and aiming to generate visibility and attract the view of the municipality towards thecommunity.

It is about resisting, making a statement, raising the voice. Through artandmusic,theyhaveworkedtomitigatecommunityproblemsby givingyoungpeoplewhojointhesealternativetoolsfocusedonart asawayoutofdrugsanddelinquency.Itisawaytomakevisiblethe invisible:thesocialstigmaandtheoblivionofthestate.

(seeFigure2.3)

Survamosisgraphiclaboratorythat recallstheoriginsofthefamiliesinthe territory,themeaningandimportance ofnature,aswellastheroleofthe mountainastherootsofidentity. Itis politicalpositionthroughart.

Bahn et al., 2020 have argued that “Reading the pandemic means… looking beyond formal actors and institutions… It is to ask what new forms, practices and agencies have emerged as rearrangements and whattheymayteachusaboutwhatishappeninginandtoourcities”.

Huertopía and Survamos are an example of this, communities taking responsibility and making a step forward. It also shows how they demand government attention and response. In doing so they are making a political statement, not just waiting the government to respond,butdoingsomethingaboutit.

Andthegovernmentshouldidentifythosepracticesandfacilitateand improve them. “Doing so does not mean that one refuses the imperative to act and respond to the pandemic at “scale.” It instead affirms that policy measures, relief efforts, and response practices… will be those that are anchored on existing and emergent modes of collective life”. As Bahn et al. (2020) put it: “Paying attention to these modesisthenwherewemustbegin,turningawayfromthelureofthe monumental,andbacktoanurbanrealismofthemajority”.

Bhan,G.,Caldeira,T.,Gillespie,K.andSimone,A.(2020).ThePandemic,SouthernUrbanismsand CollectiveLife,SocietyandSpaceMagazine,3August.

Duque,I.,Ortiz,C.,Samper,J.andMillan,G.(2020).Mappingrepertoiresofcollectiveactionfacing the COVID-19 pandemic in informal settlements in Latin American cities, Environment & Urbanization,DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247820944823.

Gilbert,A.(2007).TheReturnoftheSlum:DoesLanguageMatter?InternationalJournalofUrban andRegionalResearch,31(4):697-713.

Hernández-García,J.(2016).Hábitatpopular,unmodoalternativodeproduccióndeespaciopara AméricaLatina?In:Estéticadelosmundosposibles:inmersiónenlavidaartificial,lasartesylas practicasurbanas,Bogotá,PontificiaUniversidadJaveriana.

Robinson, J. (2006).OrdinaryCities,BetweenModernityandDevelopment,London andNew York,Routledge.

UNCHS. (2003).TheChallengeofSlums.GlobalReportonHumanSettlements2003,London andSterling,Earthscan.

This brief essay offers a provocation on what I call kapwa urbanism and the challenges that urban solidarity practices face during and beyond the currentCOVID-19pandemicinMetroManila.

Over a year into this global pandemic, international borders remain closed, vaccines have been unevenly distributed and things remain uncertain. In this very challenging period, the writer Rebecca Solnit (2020)remindsthat“Oneofourmaintasksnow–especiallythoseof us who are not sick, are not frontline workers, and are not dealing with other economic or housing difficulties – is to understand this moment, what it might require of us, and what it might make possible”.

Lastyear,Itookpartinanotherwebinarthattriedtomakesenseof the situation in Metro Manila at that time. In the Philippines, as elsewhere, the COVID-19 pandemic is more than a public health issue; it has become a socio-economic crisis. We witnessed how leaders in different cities and countries scrambled for sound approaches to navigate the onslaught of COVID-19. Some of them looked shocked as if the virus suddenly came out of nowhere. So, I would argue, there is also an element of leadership crisis. A manifestationofthisleadershipcrisiscanbeseeninincoherentstate strategiestocontaintheCOVID-19virus.

Theconceptofkapwa, meanssharedidentity, isthecoreconceptofpsycho-social relationsinFilipinosocialpsychology.

Thisrevealsandaggravatesalong-standingpre-COVID-19problemin the country, which is fundamentally linked with our fragile democratic institutions. Due in part to weak public institutions, leaders have resorted to what they know best. One of which is clientelism in the delivery of social assistance. In many communities, service delivery is riddled with patronage politics on the ground. People have also resorted to self-help practices – locally known as bayanihaninthePhilippinesorgotongroyonginIndonesia-todeal withtheimpactsofCOVID.Letmeframetheself-organisedinitiatives andsolidaritypracticesthroughIwhatcallkapwaurbanism.

Here, “The akoor self (ego) and the iba-sa-akin (others) are one and thesameinkapwapsychology:Hindiakoibasaakingkapwa(Iamno different from others)” (Enriquez 1978, p. 106). Kapwa somehow resonateswiththeAfricannotionofubuntu,whichisaboutsharedor commonhumanity.

The other important concept is the ethic of care. I draw from Fisher andTronto’s(1991,p.40)definitionofcareas"anactivitythatincludes everythingthatwedotomaintain,continue,andrepairour'world'so that we can live in it as well as possible. That world includes our bodies, our selves, and our environment, all of which we seek to interweave in a complex, life-sustaining web". From this definition, care is a process, and we need to rethink our account of human nature—that humans are interdependent rather than independent. Thus, to place the ethics ofkapwaand care at the center of human life and governance processes requires rethinking many of the assumptionsaboutsocialrealitiesandpoliticalrelations.Forinstance, asTronto(1995,p.142)argues,“Ratherthanseeingpeopleasrational actors pursuing their own goals and maximizing their interests, we must instead see people as constantly enmeshed in relationships of care”.

This is where the framing of kapwaas shared identity amplifies our connectedness and entanglements with fellow human beings (and otherspecies)whomighthaveunevenbutalsosharedvulnerabilitiesin times of crisis. By offering the notion of kapwaurbanism, I seek to highlighturbansolidaritypracticesthatarerootedincare,mutualaid, multipleformsofresistanceandeverydayusesofpublicspaceinMetro Manila.

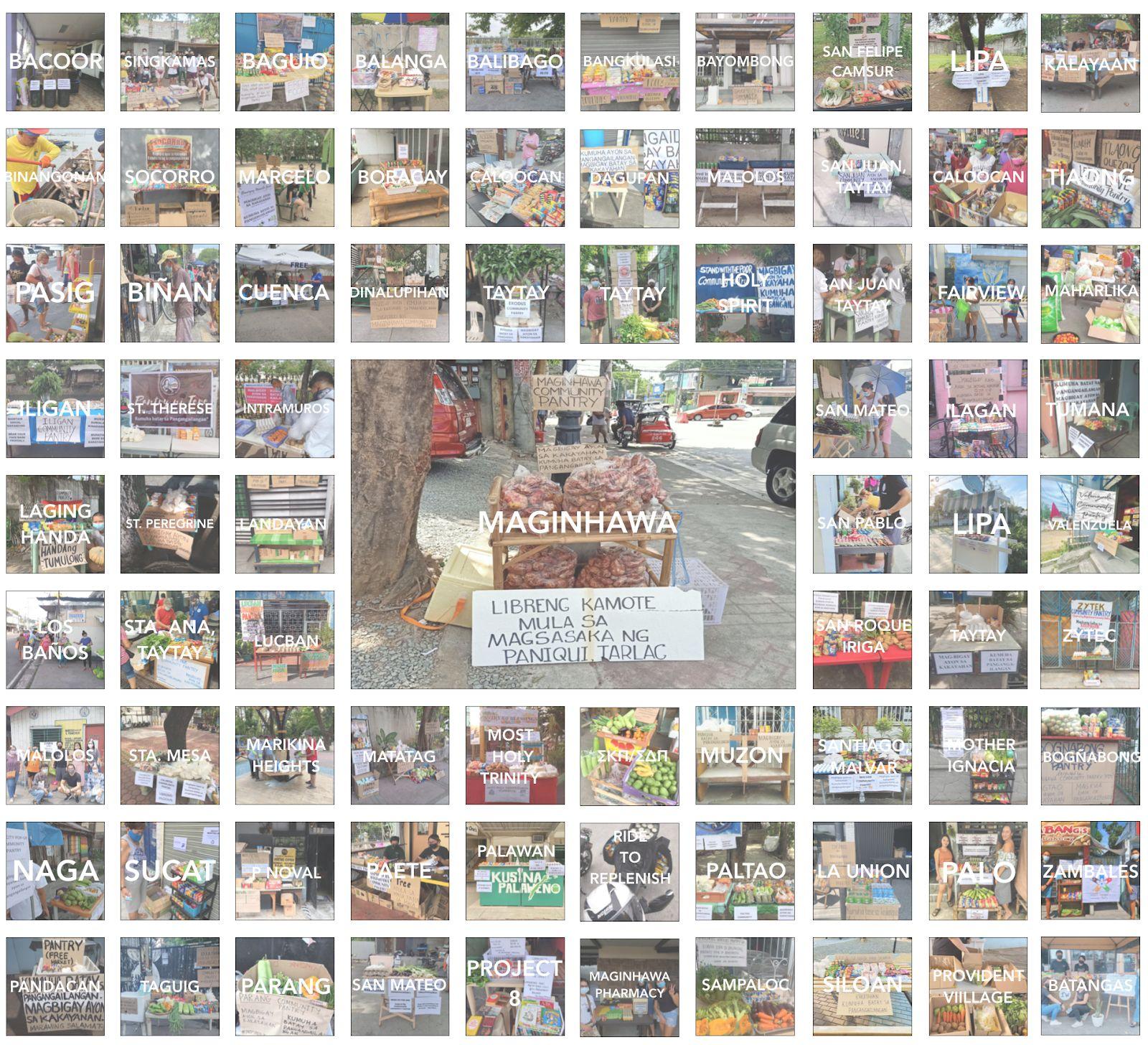

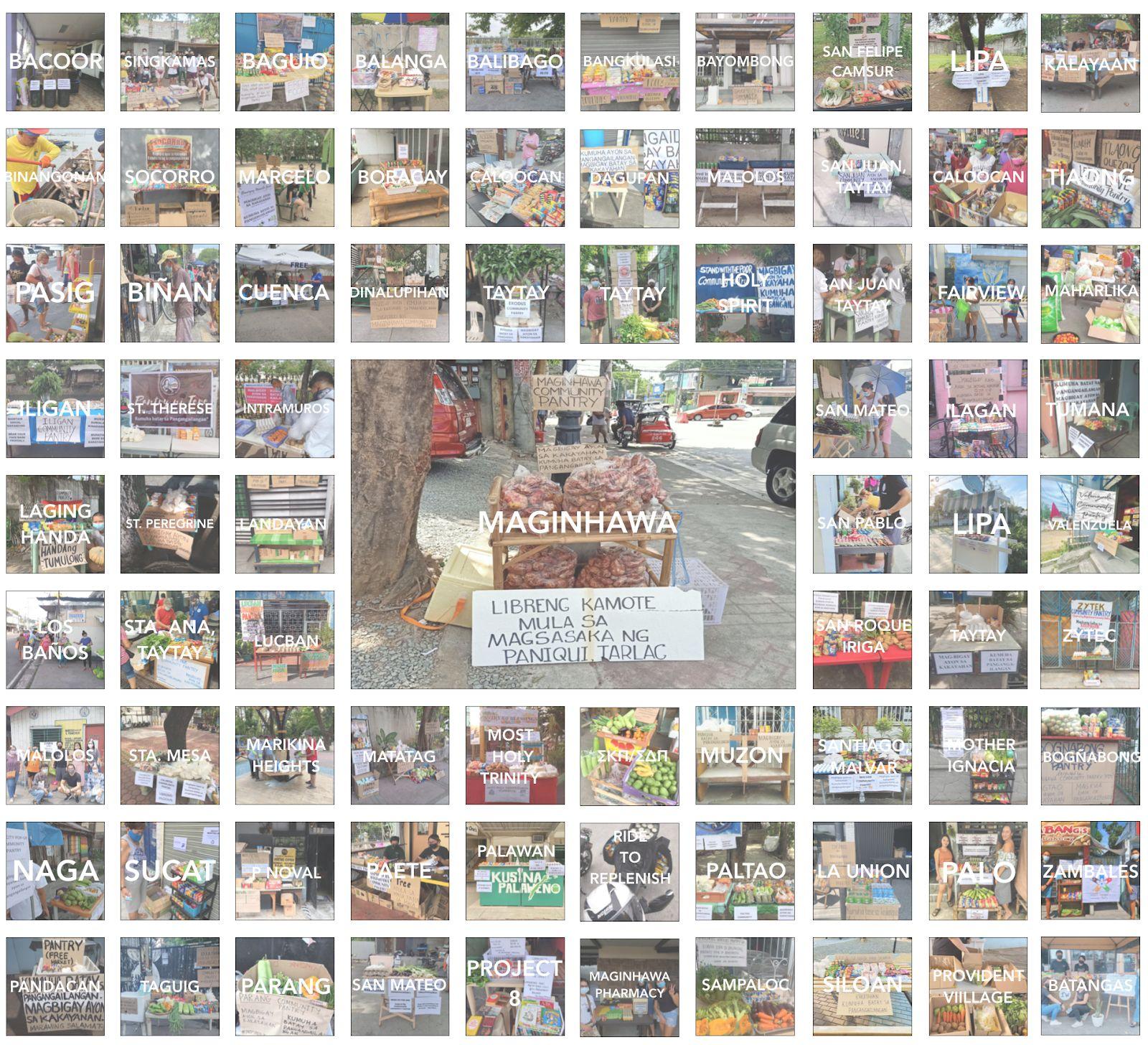

Mynotionofkapwaurbanismdrawsontwostrandsofthought.Firstis the concept of kapwa, which means shared identity, and is the core concept of psycho-social relations in Filipino social psychology. The most popular manifestation of kapwa urbanism today is the Community Pantry Movement. The first Community Pantry was initiated by Ana Patricia Non, an entrepreneur who placed a small bamboocarttoencouragepeopletodonateandtakethingstheyneed fortheday(seeFigure3.1).

The principle is “Give according to your ability. Take according to your need”. This simple principle has inspired many Filipinos. As of May 6, less than two months since Patricia Non placed a bamboo cart on Maginhawa Street, there havebeenover6700communitypantriesinthePhilippines(Maghanoy,2021). TherehavebeenmanyinterpretationsofCommunityPantriesinthePhilippines andIwouldnotbefocusingonthem.Someacademicshaveframeditasbotha clearexpressionofFilipinobayanihan(solidarity)intimesofcrisisandaformof resistance against the inability of the government to provide enough support (Dionisioetal.,2021).

Even before community pantry became a phenomenon in the Philippines, grassroots organisations, community groups and NGOs had already been engagedinvariousformsofgrassrootssolidarity(Recio,Thai&Nguyen,2020). Insomeurbanpoorcommunities,residentshavecultivatedvacantlotstogrow vegetablesforcommunityconsumption.Somegroupshaveputupcommunity kitchenstohelpfeedfamilieswhorelyonhighlyprecariousinformalworklike wastepickingandstreetvending.

Theprincipleisgiveaccordingtoyour ability,takeaccordingtoyourneed.

Another key element of kapwaurbanism is pakikibaka (solidarity in struggle) as confrontative value of kapwa. Even before the pandemic hit, public places and community spaces had been used to express resistance orcallonpublicofficialstoactoncertainissues.Figure2 below captures the demands by urban poor being displayedinapublicspacewithintheircommunity.Here, wecanseehowkapwaurbanismandcarearedeployed as a demand to make things right, to rectify state interventions that might be fundamentally flawed as an approach.

ThelastelementofkapwaurbanismthatIwill discuss here pertains to the range of everyday uses of public space in Metro Manila. In an on-going research, which examines the governance and spatiality of informal street vending in three Asian metropolises, we used a 2 km by 20 km transect map to locate the presenceandintensityofstreetvendingInMetroManila. The transect map traverses four local governments (see Figure3below). We used google street view to identify andcapturetheactivities.

We also document other activities that appropriate public space in the areas within the transect map. We have identified six other appropriations, but I will just focus here on four of them – playing, seating, greening, and production (which could be related to economic production or house work) – see Figure 4 below. Arguably, these activities entail social interaction and care activities – things that nurture us as social beings and cultivate our relationship with fellow human beings orwithnature(inthecaseofgreeningorgardening).

To what extent do these activities shape the public space in Metro Manila? Greening is present in about a third of the accessible location;seatingisobservedin22%ofthespots.Productionandplay are present in about 18% of the transect . These numbers reveal at least two things: Metro Manila residents are very social; they are willingtoencroachonpublicspacetoundertaketheseactivities.This reveals the lack of state-provided common space and the ingenuity of urban residents to appropriate very limited public space. It is, therefore, important to understand how these everyday practices of kapwa urbanism could enrich the vitality of streetlife and social belonginginmegacitieslikeMetroManila.

Thisbringsmetothechallengestokapwaurbanism.Therearemany hurdles, but I will only discuss three things. First is the tendency to over-formalise/over-regulate things through highly centralised processes. The community pantry is just an example here. The government had initially attempted to regulate (even if their own system has been inefficient) the bottom-up initiatives across the archipelago.

Figure3.3:TransectMapinMetroManila(above)

Figure3.3:TransectMapinMetroManila(above)

In the end they backtracked due to strong public support for the community pantries. However, the government often resorts to over-regulation of many other aspects of public life in the city. As I alreadynoted,morethanformalisationofsociallife,itisvitalthatwe understand how these everyday practices of kapwaurbanism and informal care networks could promote human flourishing in global SouthcitieslikeMetroManila.

A second challenge concerns the highly punitive approach to this crisis. Some fellow scholars have contended that the state has treated the pandemic as a securityissuemorethanapublic health problem (Bekema, 2021; Hapal, 2021). This has undermined people’s mobility and self-organised initiatives to help each other. Even the organizers of Maginhawa community pantry felt threatened at some point when some police personnel associated the mutual aid initiatives the Communist Party of the Philippines, a typical red-taggingtacticonthepartof thegovernment.

Bekema,J.D.L.C.(2021).Pandemicsand the punitive regulation of the weak: experiences of COVID-19 survivors from urban poor communities in the Philippines.ThirdWorldQuarterly,1-17.

Dionisio,J.,Alamon,A.,Yee,D.,Palanca, K.A.J.,SanchezII,F.,Mizushima,S.M.,& Alvarez,J.J(2021).ContagionofMutual AidinthePhilippines:AnInitialAnalysis oftheViralCommunityPantryInitiative as Emergent Agency in Times of Covid-19. Retrieved from: http://philippinesociology.com/contagio n-of-mutual-aid-in-the-philippines/

Enriquez , V. G. ( 1978 ). Kapwa: A core concept in Filipino social psychology. Philippine Social Sciences and HumanitiesReview,42,100–108

Fisher,B.,andTronto,J.C.(1990).Toward afeministtheoryofcaring.InCirclesof care:Workandidentityinwomen'slives, ed. Emily Abel and Margaret Nelson. Albany: State University of New York Press.

The third issue is the tendency to rely on the usual growth-chasing economic paradigm. This will be more critical as governments introduce recovery strategies. In the Philippines, it is crucial to pay attention to the prospects for solidarity-based economic paradigm. Thevariousmutualaidinitiativeswehaveseenshowtheimportance ofexploresolidarity-orientedeconomicmodel.Inthissolidarity-based recovery path, kapwaurbanism can offer insights on how to move forward.

Hapal, K. (2021). The Philippines’ COVID-19 Response: Securitising the Pandemic and DiscipliningthePasaway.JournalofCurrent SoutheastAsianAffairs,1-21.

Solnit, R. (2016). Hope is an embrace of the unknown: Rebecca Solnit on living in dark times.TheGuardian15

Maghanoy, C. C. (2021). Community pantries up to 6.7K in PH – DILG. The Manila Times. Retrieved from: https://www.manilatimes.net/2021/05/06/ne ws/community-pantries-up-to-6-7k-in-ph-dil g/870868

Recio,R.B.,Thai,H.,Nguyen,P.2020.Therole of solidarity economy in surviving a crisis: What governments can learn from street workers’ responses to the pandemic.Policy Forum. Retrieved from https://www.policyforum.net/the-role-of-a-s olidarity-economy-in-surviving-a-crisis/

Tronto,J.C.(1995).Careasabasisforradical politicaljudgments.Hypatia,10(2),141-149.

This essay reflects how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the informal economy sector in Indonesia. By dissecting the character of the informal sector that allows this sector to survive collectively and adapt amid adversity through 3 examples of case studies. This essay will also reflect on the actions taken by the rife service platforms in Indonesia and the practices behind them that allow for predatory rather than solidarity regarding immense capital influence over the typical small to medium scale informaleconomy.

InthecontextofIndonesia,theInformalEconomyisoftendefinedas theantithesisoftheformaleconomy.Thisunderstandingmeansthat the informal economy sector is seen as a sector that does not pay taxes and has no guarantees for its workers. Central Bureau of Statistics (BPS) defines the informal sector as a person's main job status, which includes self-employment, enterprises assisted by non-permanent workers, permanent workers, laborers/employees, freelanceworkersinagriculture,anddailyworkersinnon-agricultural andfamilyworkers.However,thisdefinitiondoesnotexplicitlycover whattheinformalsectoris.Untilnow,theinformalsectorwasnotthe main focus of government policy or attention, including during the COVID-19 pandemic. The government does not even have a general definition of the informal sector and only defines business scale (small,medium,andlargeenterprises).

Despite the government's lack of understanding of the informal economysector'scharacter,consistenteffortsaremadetotransform the informal sector into formal enterprises, especially in administrationandactivitylocations.Thiseffortismainlymotivatedin ordertoeasethegovernment'sworkload.Forexample,itiseasierfor the government to transfer cash or support, administer the exact number of sellers to be relocated, and benefit the government from moreaccessibletaxcollection.

With this opportunity, we intended to look at the informal economy initsgeographicalsetting,socialnetwork,andrelationshipproduced by it or from it. Understanding these characteristics becomes very important,consideringthereisnosolidandthoroughdefinitionofthe informalsector.

UGM explainedthattheinformalsectorhasanumberofsmall-scalebusiness units, with individual or family ownership, utilizing simple technology and soft skills. Another thing is that it is difficult to access local financialinstitutions,lowlaborproductivityandrelativelylowerwage than the formal sector. Another critical characteristic that Simone (2015) raised is that informal economy actors interact with various social classes and empower many people, acting with autonomy and an independent structure. This autonomy is carried out by utilizing socialnetworkstobuildrelationshipstofulfillneeds,supplymaterials, work and distribute shifts, packers, delivery workers and so on. These autonomous characteristics allow the great diversity of how people dealinthecitybyusingtheirtactics,strategies,organizing,protesting, occupying,andsolidaritymovement.

Based on these characteristics, where the informal sector unites the needs and abilities of various social classes and is very close to social networkstobuildsupplyanddemandrelations,wefeelthatthemore appropriatetermis"peopleeconomy"overtheinformaleconomy.Our perspective is similar to what happened in Latin America, which has theterm"populareconomy"comparedtotheinformaleconomy.Both thesenamingshowsbetteranddeeperunderstandingratherthanjust calling this "informal economy" based on the absence of formal registrationbythegovernment.

Based on the understanding above, we bring up 3 example cases as interestingcopingmechanismsandsolidaritypracticesintheinformal sectorduringthepandemicinIndonesia.Allcasesaredistinctyetshow the different levels of involvement between the informal worker and other significant actors involved and influence the informal sector workers' ability to carry out collective adaptation efforts during the COVID-19pandemic.

Theseautonomouscharacteristicsallowthe greatdiversityofhowpeopledealinthecityby usingtheirtactics,strategies,organizing, protesting,occupying,andsolidaritymovement.

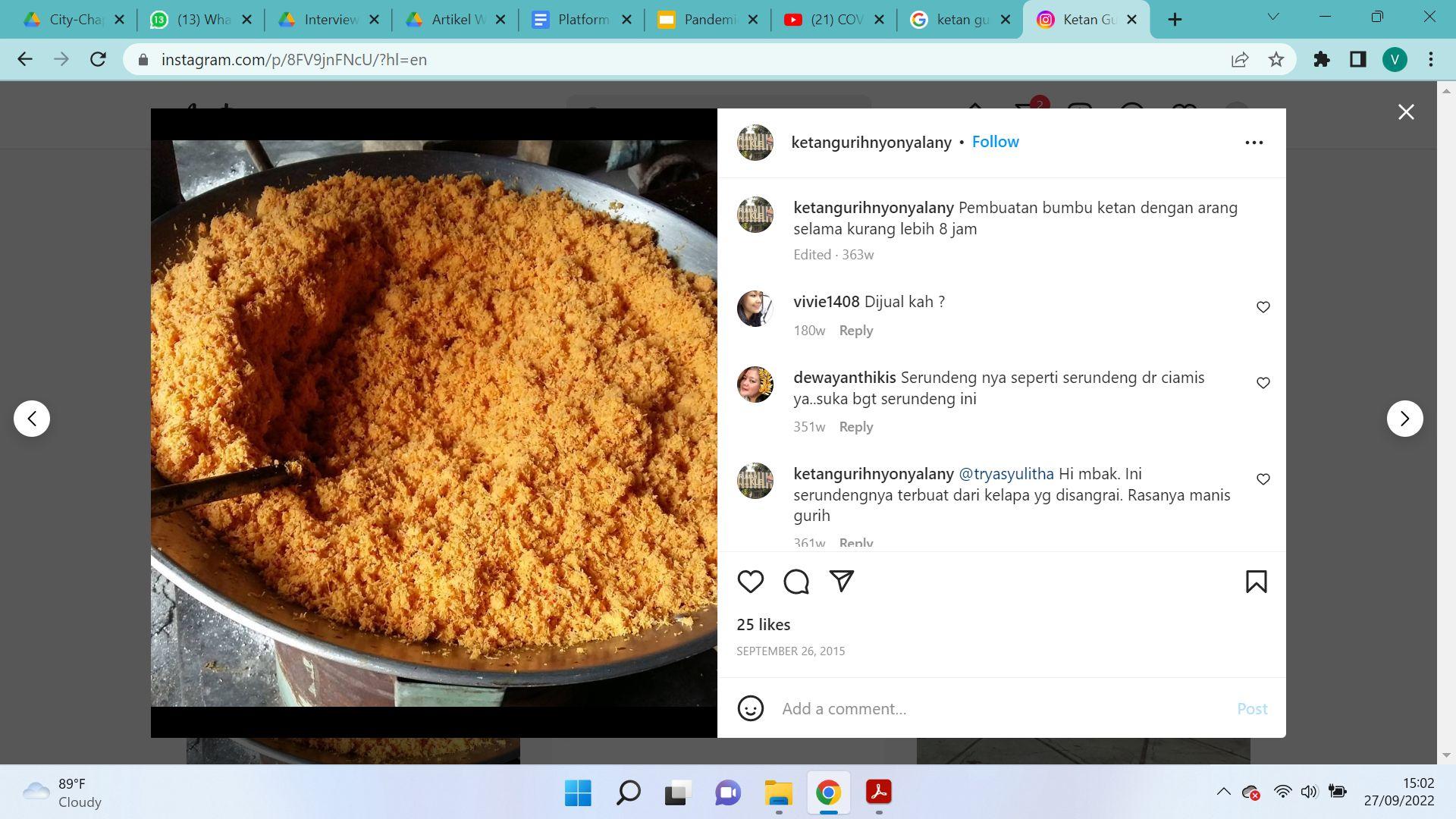

The first story is about a family's snack shop in the backyard of a former (childhood) house. Fifteen years ago, they transformed the gardenintoakitchenandaplacetostartasnackbusiness.Soonthe family developed the business into a medium-scale house industry. Employing the government point of view, this family business is a formaleconomy.Sincetheyarepayingtax,thebusinessisregistered, has a food safety license, and pays the worker above the minimum wage, with proper overtime compensation and working hours. By these criteria, this business is ticking all the formal economic requirementsfromthegovernment.

However,thebusinesshasasolidfootholdbasedonthecomplexity of the social relationship between many actors and vendors. The image below showing each ingredient used shows a different relationship produced by this business to make this product come together.Examplesarethetoothpickusedtosealtheglutinousrice inside banana leaves produced by a family of the third generation runningthetoothpickbusiness,whomtheyrelyonastheirsourceof livelihood.Theyalsomadethesticksusingthetreethatonlygrows inspecificareas;theyaretheonlyfamilylefttoproducethat.Sothat if they are not continuing their business, it will be tough to find a replacement.

Source:https://www.instagram.com/ketangurihnyonyalany/?hl=en

Figure4.1StickyricesnackProductofhomeindustry

Figure4.1StickyricesnackProductofhomeindustry

Thefamilydidnotprocuretheingredientfromthebestpricesupplier either, yet through relatives. Even the banana leaves are also coming fromstreetvendors.Thesamethingwithspicesrequiresmanyworkers fromthesamecommunitytoensuretheirworkissynchronizedundera recipe. From this first case, we can see a complex social relationship with a simple snack product. Furthermore, this relationship never receivedanyrecognitionfromthegovernment.Thegovernmentisnot acknowledging this social relationship behind a particular formal business, which makes a simple product become a network of livelihoodformanyfamilies.

Complex social relationships and networks also happen in many small productionsinKampungs.So,whenthegovernmentevictedkampung, they also wiped out all the ecosystems. This spatial issue has a social-economiccorrelation,whichweneedtodiscussmore,especially whenwetalkabouttheinformaleconomyanditspolicy.

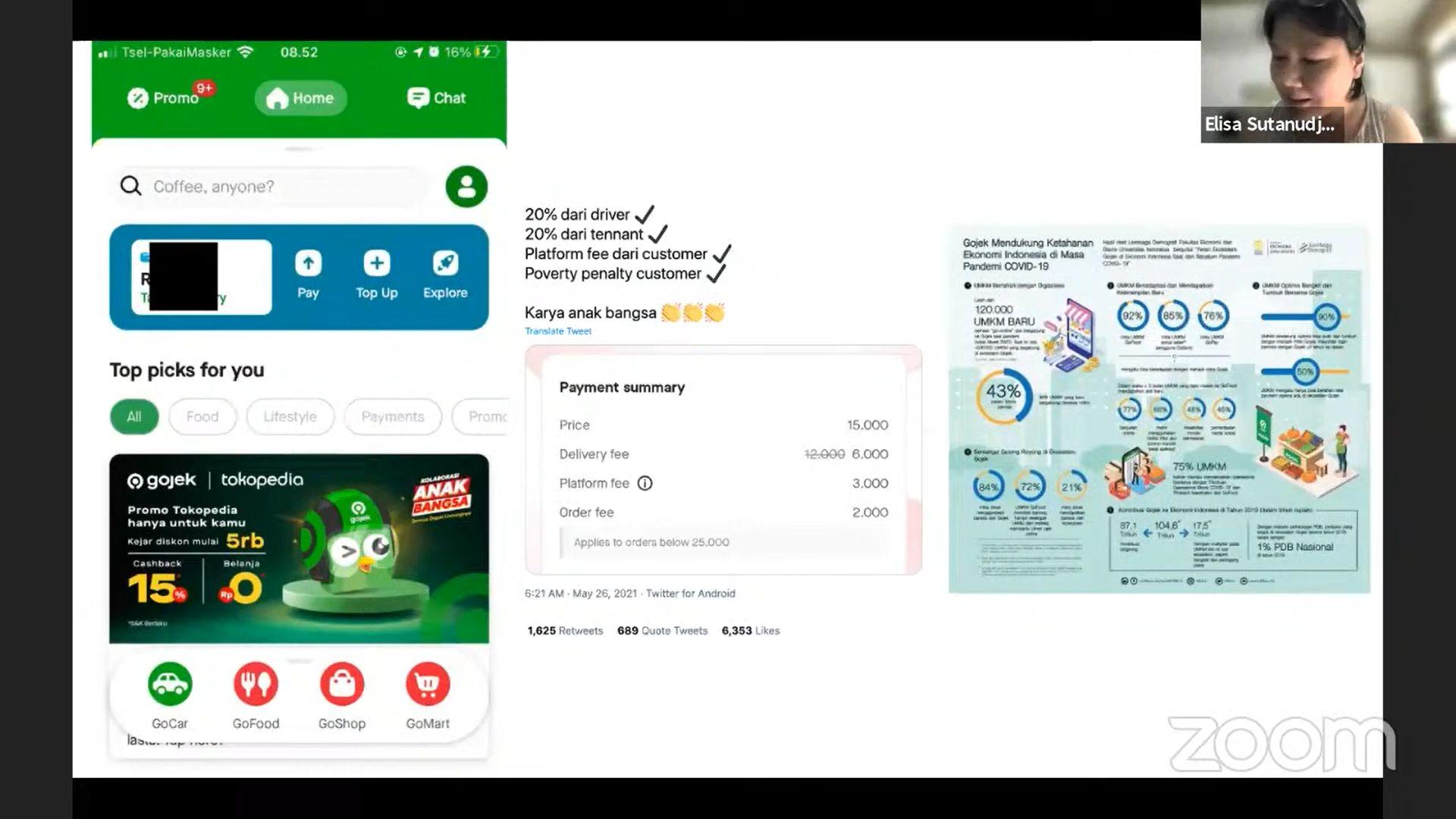

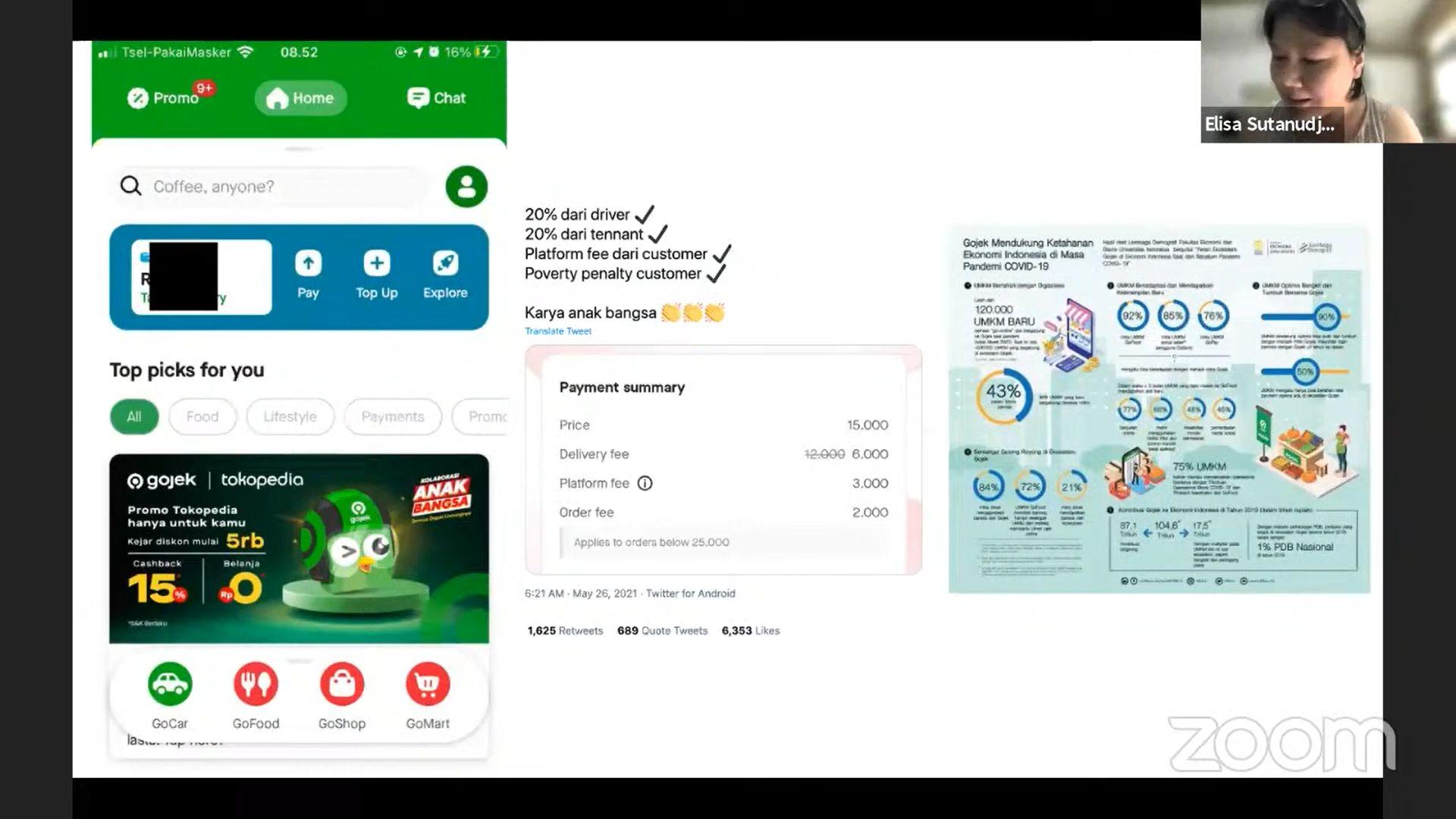

Another case is about the biggest super app in Indonesia called GOJEK.Thisappoffersridesservices,fooddelivery,deliveryservices, andothers.InMay2021,GOJEKmergedwithothergiantunicornsand rebrandeditselfasGoTo,withthejointevaluationsreaching22billion USD.Thispartwilldiscusshowthisunicornsteppedintotheinformal economy sector: the motorbike ride service (taxi bike) and SMIs (warungorstreetvendors),andhowthesuperappsproducedbythis unicorn are the pinnacle of platform capitalism, which is extracting fromthebottombillions.

There was a controversy on social media about the cost of the platform.Images1showthattheappsrecentlyaddeda“platformfee” feeontopoftheprice,deliveryfee,andorderfee.Besidestherising service fee implied by the unicorn, while also decreasing the driver’s rights. The relationship is somewhat more complicated because the government is endorsing this app. The government favors this platform economy because they have the impression that this platform is helping the government to formalize the informal economyandalsohelpingtheSMIactors.But,isit?

Thisapplicationusuallyvalues their success by how many actors are registered or getting income. However, sellers need to compete with more prominent players with

Source:twitter.com

Figure4.3 Appsadditionalfee&customer complainsonsocialmedia

Figure4.3 Appsadditionalfee&customer complainsonsocialmedia

Overtime,theincreasingnumberofvendorsalsomakesthecondition sosaturatedthatvarioussellersaresellingthesamegoods,makingit difficulttodistinguishthequality.

Asweunderstand,thewaytoadvertisethebusinessontheplatform is very much different from how the informal worker promotes the businessonthestreet.Thuscreatingamassivegapbetweensellerson the digital platform and raising the question of whether this appears to be “technological advancement” is needed to target the informal economy,whichisgrowingitscustomerbaseinthesurroundingarea.

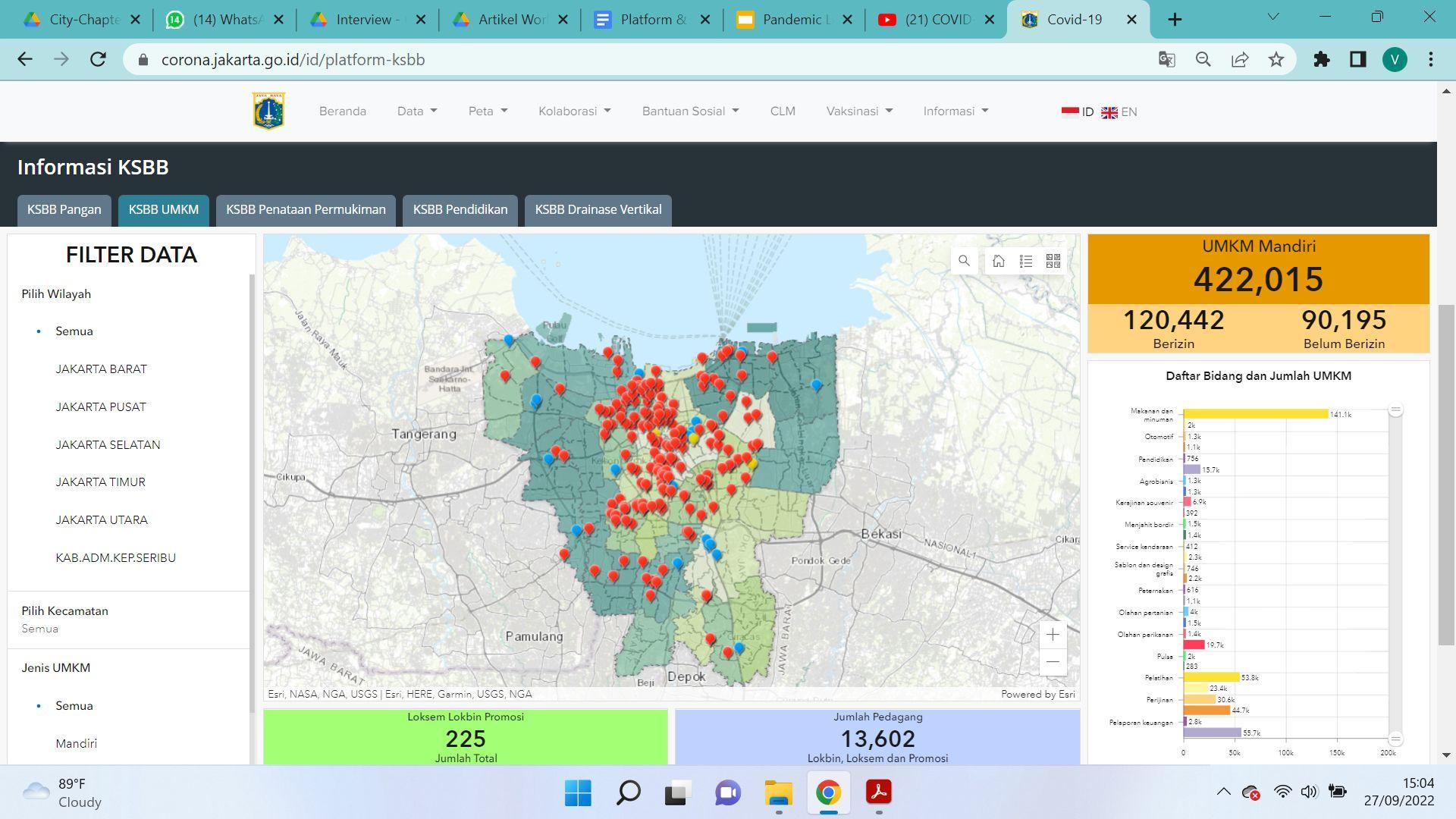

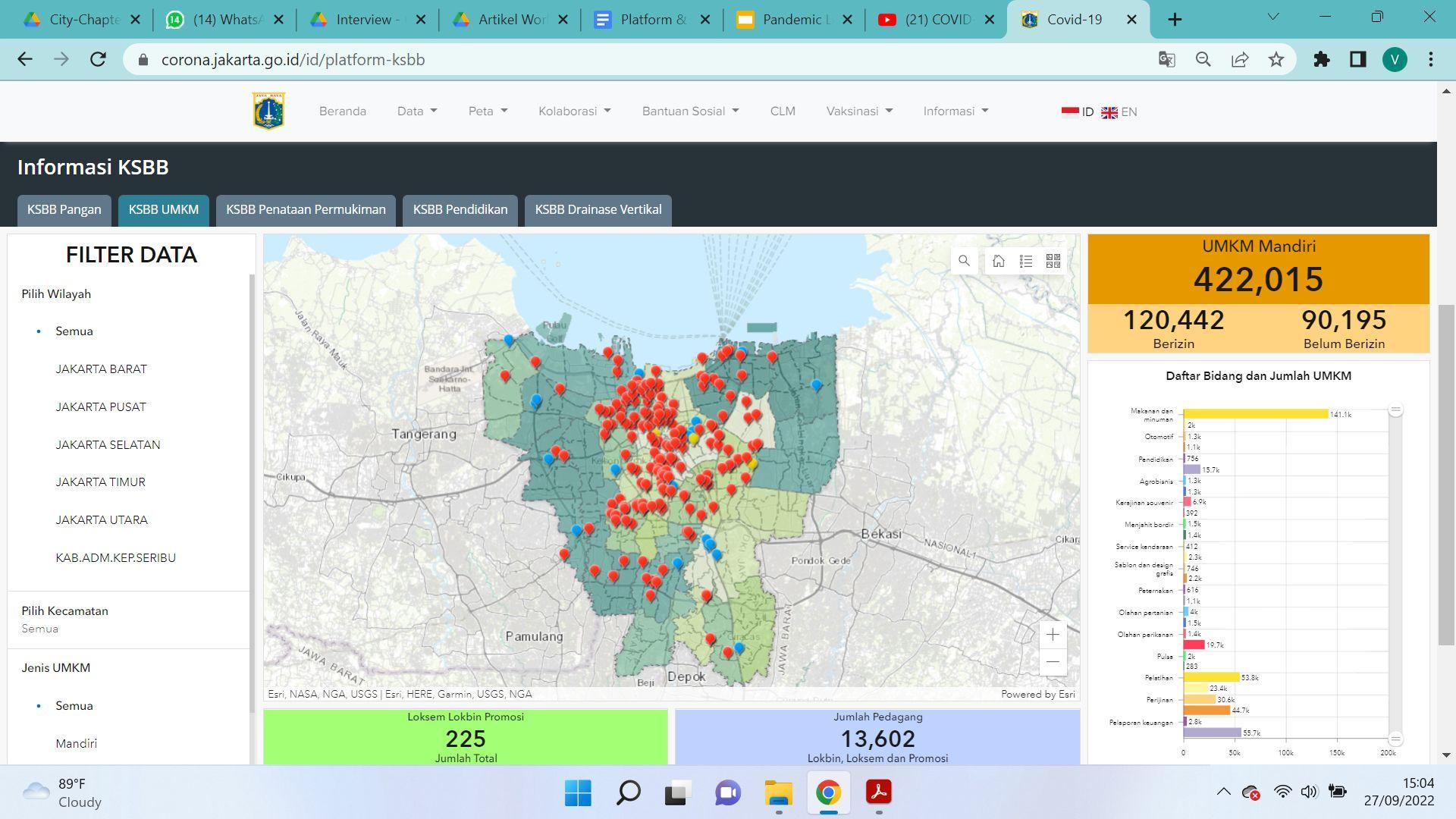

The last story comes from a platform made by the Jakarta Government,calledtheLarge-ScaleCollaborationPlatform(Kolaborasi Sosial Berskala Besar), which was made in 2020. This platform was made after the government experienced financial difficulties when it neededtodistributesocialaidduringthepandemic.

Thisplatformusesthegotong-royongormutual collaborationasthegroundworkandworksasa toolfordonorstomeetthepeoplewhoneed thehelp,andinthiscase,streetvendors.

Behindthewayitworks,thisplatformisalso anotherwayforthegovernmenttoformalize the“informal.”Beforetheysetupthis platform,aroundApril2020,togetherwiththe nationalgovernment,theylaunchedasurvey askingstreetvendorsandinformaleconomy workerstofilloutaforminorderforthemtoget aid. The data becomes the government database to build this platform. There are several types of aid;thefacilitypackage,capitalloanpackage,and trainingpackage.

The reflection from this case is how this platform was initially made based on the difficulties the governmenthadinprovidinghelptoactorsinthe informal sector who needed it, which is a government responsibility. This platform allows the government to share the burden with donors andforthedonorstousethisplatformtochannel the donation to those who deserve it. This act of kindnessisdeeplyrootedinIndonesianculture.

Thisconditionproducesadilemma.Theplatformalsoactsasatoolthat splits/ease the government's responsibility to make use of the people tax,whereinthiscase,theburdentohelpthoseinneedisonceagain backtocivilians.Somehow,wecanseethisplatformmanipulatingand using the "solidarity habit of giving" to lessen what the government shouldprovideforthecitizens.Moreover,fromanotherviewpoint,this platform does data extraction and behaves like corporations or super appsfromthepreviouscase.

Pekerja di Sektor Informal. Badan Pusat Statistik. Available : https://sirusa.bps.go.id/sirusa/index.php/variabel/8483.

UniversitasGadjahMada.“PeranSektorInformaldiIndoensia”,UGMWebsite,March 08, 2006 [Online]. Available : https://www.ugm.ac.id/id/berita/1756-peran-sektor-informal-di-indonesia [Accessed on27September2022]

Simone,AbdouMaliq(2015).TheUrbanPoorandTheirAmbivalentExceptionalities SomeNotesfromJakarta,CurrentAnthropology,Vol.56,No.S11,PoliticsoftheUrban Poor:Aesthetics,Ethics,Volatility,Precarity(October2015),pp.S15-S23,TheUniversity ofChicagoPress

MercedesRuehl,”Indonesia’sGojekandTokopediaagree$18bnmerger”,Financial Times, May 17, 2021 [Online]. Available : https://www.ft.com/content/ce944c28-a6d1-42b9-9da2-12e90cb2ae19.[Accessedon16 October2021].

Novianto,A.,Wulansari,A.D.,&Hernawan,A.(2021,April30).Riset:empatalasan kemitraanGojek,Grab,hinggaMaximmerugikanparaOjol.TheConversation.Retrieved February 4, 2022, from https://theconversation.com/riset-empat-alasan-kemitraan-gojek-grab-hingga-maximmerugikan-para-ojol-159832

Ibrahim,S.M.(2017,Maret30).MenhubDukungKolaborasiAnakBangsaAntaraBlue Bird Dan Gojek. The Conversation. Retrieved February 4, 2022, from http://dephub.go.id/post/read/menhub-dukung-kolaborasi-anak-bangsa-antara-blue-b ird-dan-gojek

KolaborasiSosialBerskalaBesar.(2020).PemerintahProvinsiDKIJakarta.Available: https://corona.jakarta.go.id/id/platform-ksbb

Mangihot,Johannes(2020).“BantuUMKMTerdampakCovid-19,PemprovDKIGandeng Dompet Dhuafa”, Kompas, 15 Juli 2020 [Online]. Available : https://megapolitan.kompas.com/read/2020/07/15/11212951/bantu-umkm-terdampak-c ovid-19-pemprov-dki-gandeng-dompet-dhuafa.[AccessedonFebuary2022] References

ThereistoomuchevidencetoshowthattheCOVID-19pandemicisnot onlyahealthcrisis.Thetwoyearsofthepandemichaveshownmoreof the system's unpreparedness for protecting and fulfilling the needs of itspeople.Itbringsmanysubsequentproblemsandiswideninggapsin ability,financialsecurity,tenure,andhealth.

Without protection, most people are left without options. Demonstrations, job shifts, and people migration result from the broken system. Furthermore, on the grassroots level, many solidarity actions emerge; the distribution of free food and mutual support throughlongproductionchainsandartisticstatementsareonlyafew effortsthatwererecorded.Thiseffortisthewealthforthecommunity togetbetterconditionsamidinjustice.

However, these little things can give an idea and open the minds of many people about the imbalance of people's power in coping with disasters -both short and long-lasting disasters-and how to work collectivelytobeawayoutformanypeople.Thiscollectiveculturehas proventolightentheburdenonindividuals,anditisappropriatetobe acknowledgedascommunitycapital,especiallyintheGlobalSouth,in thecontextofpreventingandhandlingdisastersinthefuture.

Thisbookletshowsonlyatinypartof thecollectiveeffortsofthepeoplein theGlobalSouthtosurvivethe COVID-19pandemic.

Figure1.1

SocialUprisinginChile,Imagesource:SusanaHidalgo,2019

Figure1.2

AnexampleofsocialhousinginChile, Imagesource:LuzMaríaVergara, 2016

Figure1.3

AnexampleofsocialhousinginChile,Imagesource:LuzMaríaVergara, 2016

Figure2.1

InformalsettlementsinBogotá

Figure2.2

OneoftheHuertopíaallotments

Figure2.3

SurvamosstreetartinCiudadBolivar

Figure3.1

CommunityPantriesinthePhilippines,Source:JeanPalma

Figure3.2

Residentsinaninformalsettlementdisplayedtheircallstothe government:AidnotArrest;RicenotViolence;MedicalSolutionnot MilitaryAction,Source:SaveSanRoqueAlliance

Figure3.3

TransectMapinMetroManila

Figure4.1

StickyricesnackProductofhomeindustry

Source:https://www.instagram.com/ketangurihnyonyalany/?hl=en

Figure4.2

Superapphomescreen,Source:Author

Figure4.3

Appsadditionalfee &customercomplainsonsocialmedia

Source:twitter.com

Figure4.4

KSBBPlatformmadebyDKIJakartaProvincialGovernment

Source:https://corona.jakarta.go.id/id/platform-ksbb

Incollaborationwith:

Incollaborationwith: