Lessons from Boeing’s 737 MAX 8 crashes

Holistic safety

Integrating safety into the DNA of an organisation

Inside Telstra’s return to work program

Rethinking contractor safety management

Our team provide a complete range of services through from audit and assurance, to building leadership to critical control management & improving wellbeing, we help to operationalise and create sustainable change. Scan below to learn how you can make a di erence.

OHS Professional

Published by the Australian Institute of Health & Safety (AIHS) Ltd. ACN 151 339 329

The AIHS publishes OHS

Professional magazine, which is published quarterly and distributed to members of the AIHS. The AIHS is Australia’s professional body for health & safety professionals. With more than 70 years’ experience and a membership base of 4000, the AIHS aims to develop, maintain and promote a body of knowledge that defines professional practice in OHS.

Phone: (03) 8336 1995

Postal address

PO Box 1376

Kensington VIC 3031

Street address

3.02, 20 Bruce Street

Kensington VIC 3031

Membership enquiries

E: membership@aihs.org.au

Editorial

Craig Donaldson

E: ohsmagazine@aihs.org.au

Design/Production

Anthony Vandenberg

E: ant@featherbricktruck.com.au

Proofreader

Lorna Hudson

Printing

Printgraphics

Advertising enquiries

Advertising Manager

Natalie Hall

M: 0403 173 074

E: natalie@aihs.org.au

For the OHS Professional magazine media kit, visit www.aihs.org.au.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect AIHS opinion or policy. No part of this magazine may be reproduced in whole or in part without the permission of the publisher. Advertising material and inserts should not be seen as AIHS endorsement of products or services

Managing the risk of airborne contaminants: The rise of OHS risks such as silicosis and other airborne contaminants necessitates stringent safety measures

14

Leading the regulator: Head of SafeWork NSW, Trent Curtin, discusses trends, challenges and priorities for the regulator

Inside Telstra’s return to work program: Telstra’s work transition program is an innovative and effective model for helping employees with the process of returning to work

Holistic safety: integrating safety into the DNA of an organisation: A holistic approach to OHS, incorporating leadership, culture, processes, systems, and continual improvement, is critical to safety performance

Rethinking contractor safety management: changing perspective: The job of safety professionals is to ensure the safety of contractors at their

26 32

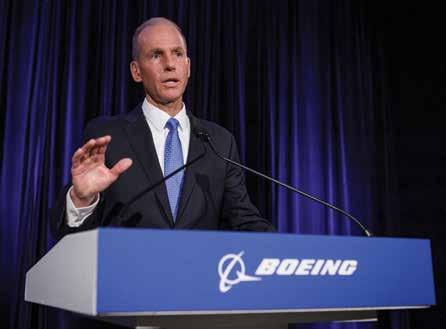

How complex systems complex systems fail: lessons from Boeing’s 737 MAX 8 crashes: A complex systems approach is more useful in analysing incidents such as Boeing’s 737 MAX 8 failures 16

Beyond compliance: building cultures of safety and resilience

In this issue, industry leaders share how they are going beyond compliance and taking a holistic approach to managing and improving OHS

When Mitchell Services won the Australian WHS Team of the Year in last year’s Australian Workplace Health & Safety Awards, the company’s WHS team was recognised for its initiative, determination, relationship-building skills, and drive to help achieve tangible business improvements. There has been a significant shift in how WHS in the business is perceived and managed, thanks largely to the efforts of Josh Bryant, Mitchell Services’ GM of people, risk and sustainability and his team, who have embedded philosophies

Corporate Members

SHARING OUR VISION – DIAMOND MEMBERS

Amazon

Avetta

CleanSpace Technology

Department of Agriculture, Fisheries, and Forestry

HSI Donesafe

Milwaukee Tools

GETTING CONNECTED – SILVER MEMBERS

Australian Bureau of Statistics

Australian Unity

Brisbane Catholic Education

Clough Projects

CM3

Codesafe

Compita Consulting

Convergint

Curtin University

Downer

Ecoportal

Fifo Focus

Fusion Safety

Guardian Angel Safety

Herbert Smith Freehills

Would

Pan Software

Programmed

SAI360

Sentis

Woolworths

Zenergy

Hitachi Rail

HOK Talent

Pilz

of Human and Organisation Performance (HOP) across the business. This has ensured a holistic approach to managing and improving WHS outcomes, which is the focus of the cover story (beginning page 16) of this issue.

Instilling a culture where safety is ingrained into every aspect of the organisational’s DNA requires a concerted effort at all levels, from leadership to frontline workers, as well as a commitment to transparency, communication, and collaboration. In addition to Mitchell Services’ Josh Bryant, Cumberland City Council’s manager audit, safety and risk, Belinda Doig, and Powerlink Queensland’s general manager of health, safety and environment, Ben Saal, explain how their organisations are taking a more holistic approach to safety that transcends compliance to build cultures of resilience, trust, and empowerment.

Also in this issue, Dr Sean Brady examines Boeing’s 737 MAX 8 crashes through the lens of a complex systems approach – namely the sand pile model. Rather than trying to string all the contributing factors together in a line, this model is a more useful way of viewing these types of incidents because it asks us to re-examine our more traditional views on

cause and effect, and instead look more closely at the sand piles we build in our own projects and organisations. For the full story, please turn to page 26.

The OHS Body of Knowledge feature for this edition also prompts readers to rethink contractor safety management, which will be the focus of a forthcoming OHS Body of Knowledge chapter. As Sue Bottrell and Jon Harper-Slade explain in this feature (page 32-33), WHS professionals are in a key position to change or influence contractor safety management for the better.

Professional development is another theme that runs through a number of articles in this issue, including our story on Michelle Price and her path to AIHS Fellowship. The College of Fellows was established in 2002 and comprises members who are Fellows and Honorary Fellows of the AIHS. As Price explains in this feature (page 8-9), becoming a fellow was personally important to her, as she wanted to give back to her chosen profession and share the learning and knowledge she had gained from others.

Lastly, the Australian Workplace Health & Safety Awards 2024 are fast approaching, with a gala evening slated for 29 August in Sydney. If you haven’t got your tickets yet, please see the ad on the back page for more information.

INVESTING IN HEALTH & SAFETY – GOLD MEMBERS

Alcolizer Area 9 Army

Aurecon

BGIS

Brisbane City Council

Coles

COLLAR®

Dangerous Goods Network

Everyday Massive

EY

Federation University

Pocketknife Group

Port Of Newcastle Risk Talk

Safesearch

Safetysure

Trainwest

Transurban

Uniting SA

University of QLD

Virgin Australia

Work Wear Direct

Zinfra

HSE Global

ICAM Australia

JLL

K&L Gates

Kitney

Liontown

Metcash

MinterEllison

Safety Champion

Soter Analytics

Teamcare

The Safe Step

BEING PART OF THE NETWORK – BRONZE MEMBERS

5 Sticks

Airbus

BWC Safety

Complete Security Protection

Employment Innovations

Employsure

Fefo Consulting

Flick

Health & Safety Advisory Service

Integrated Trolley Management

Isaac Regional Council

Kemira

Liberty Industrial

Modus Projects

National Storage

National Training Masters

Government of South Australia (Office of the Commissioner for Public Sector Employment)

Processworx

Safework SA

Scenic Rim

Services Australia

SIXP Consulting

Westside Christian College

Step-by-step solutions for tackling psychosocial risks in the workplace

With the right strategies, organisations can effectively manage the complex nature of psychosocial risks, writes Julia Whitford

While psychosocial safety has been on the radar within the workplace health and safety (WHS) profession for some time now, many organisations still do not fare well when it comes to managing risks around this complex and nuanced issue. These risks require more than superficial solutions, such as awareness training. Instead, organisations must take a comprehensive approach that revisits work design, ensures consistency amongst departments, and is built on the foundations of trusting relationships with workers. The three case studies comprising this edition’s cover story (beginning page 16) all discuss the importance of psychosocial safety and why a holistic approach to managing WHS and mitigating psychosocial risks is essential.

One of the key areas for improvement is the design of work itself. Rather than taking a reactive approach that looks to mitigate illness once workers are struggling from mental ill-health and stress, organisations must realise that the work itself, when poorly designed, can be contributing to this

negative mental health. Simple data-gathering activities such as surveys, observations, and interviews allow you to understand not just what the psychosocial risks are, but who experiences which risks and when.

Building knowledge and capability within the organisation is vital. Sharing insights and best practices can help organisations develop effective strategies for managing psychosocial risks. Engaging workers in diagnosing and redesigning work processes can lead to healthier work environments and improved performance. By fostering a culture of continuous improvement and proactive risk management, organisations can better protect their employees’ mental health and wellbeing.

“As the management of psychosocial risk falls under WHS legislation, it is imperative to be across changes to legislation to ensure compliance”

Collaboration across departments – safety, HR, workers’ compensation, and operations – is essential. A key challenge in this process is the competing interests between HR and WHS, particularly around worker consultation. To overcome this, organisations should leverage existing HR metrics, such as staff turnover and sickness absence data, to gain insights into underlying issues. Additionally, aligning existing HR

The OHS Professional editorial board 2024

systems – such as recruitment, reward and recognition, learning and development, and performance management – with psychosocial safety objectives can enhance the overall effectiveness of these controls.

Once these steps have been implemented, a final hurdle to overcome is buy-in. You can ensure the design of work is conducive to happy and efficient workers, you can prioritise and streamline collaboration between departments, and you can ensure that they are aware of your initiatives and the risks involved. Still, if you are not able to meaningfully communicate with buy-in, then these processes will be ineffective. WHS professionals must clearly understand their goals or objectives in influencing buy-in, have a pre-planned and timed approach, and have built trusting relationships with the workers they are engaging with.

As the management of psychosocial risk falls under WHS legislation, it is imperative to be across changes to legislation to ensure compliance. From consultation with members, we learned that this is something that understandably is causing stress to our members, and so we have just announced the Psychological Safety Net. In collaboration with the Australian Psychological Service (APS), the Psychological Safety Net service allows members to access a free 15-minute discussion with the APS national team of workplace psychologists. The service will be used to allow WHS professionals to discuss ways to manage psychosocial risks and help ensure compliance. I am so pleased to offer this service to our members to ensure that those tasked with managing the psychosocial health of workers are not negatively affecting their own in doing so, and that we able to offer assistance to ensure they feel well-equipped and supported.

Warning over ‘cocktail’ of serious health hazards for workers

More than 70 per cent of the global workforce are likely to be exposed to climate change-related health hazards, and existing OHS protections are struggling to keep up with the resulting risks, according to an International Labour Organization (ILO) report. For example, the ILO estimates that more than 2.4 billion workers (out of a global workforce of 3.4 billion) are likely to be exposed to excessive heat at some point during their work. The report, Ensuring safety and health at work in a changing climate, estimated that 18,970 lives and 2.09 million disability-adjusted life years are lost annually due to the 22.87 million occupational injuries, which are attributable to excessive heat. This is in addition to an estimated 26.2 million people worldwide living with chronic kidney disease linked to workplace heat stress. “Comparing exposure estimates for 2020 with those for 2000, there was a 34.7 per cent increase in the number of workers exposed to excessive heat. This increase can be attributed to both rising temperatures and a growing labour force,” said the report.

Five-day workweek boosts construction worker wellbeing

A five-day workweek for construction workers can reduce stress and improve worker wellbeing, with minimal perceived impact on productivity, according to a new report. Construction workers typically work six days a week, but research tracking a five-day workweek in the industry has demonstrated a number of significant benefits while reducing risks commonly associated with the industry. The interim report, led by RMIT University in collaboration with the Construction Industry Culture Taskforce (CICT), tracked five pilot infrastructure projects trialling a five-day workweek to address challenges such as the lack of time for life, poor health and wellbeing, and difficulty in attracting a diverse workforce. “We found the majority of workers, irrespective of gender, preferred a five-day workweek because it allowed them to spend more time with their family, see their friends, or play sports,” said project lead and RMIT distinguished professor Helen Lingard from RMIT’s School of Property Construction and Project Management.

Police officers drive up psychological injury claims payments

An increase in the volume of taxpayer-funded psychological claims is behind an estimated 50 to 66 per cent decline in return to work rates in recent years, according to a recent NSW report into workers’ compensation claims and state insurer iCare. Medical discharges of police officers who have been assessed as unable to return to the workforce have been the main source of increased psychological injury claims payments, the NSW Auditor-General’s performance audit report into workers’ compensation claims management found. Taxpayer-funded workers’ compensation payments also increased from $648 million in 2018-19 to more than $1 billion in 2022-23, according to the report. In response to a significant decline in the performance of workers’ compensation schemes, iCare is implementing major reforms to its approach to workers’ compensation claims management. However, the report noted that iCare is yet to demonstrate if these changes are the most effective or economical way to improve outcomes for the schemes.

New workplace exposure limits for airborne contaminants

Work health and safety ministers have agreed to a new workplace exposure limit list for airborne contaminants and a harmonised transition period, which will end on 30 November 2026. The workplace exposure limits will replace the current workplace exposure standards, after the ministers agreed to rename them to make it clear that a limit should not be exceeded, and for Australia to align with terms used internationally. While most exposure limits remained unchanged, the workplace exposure standards review did result in some changes, including reductions and increases in limits for certain chemicals and the removal or introduction of new limits for others. Safe Work Australia’s workplace exposure limits for airborne contaminants list notes that some people may have health effects at levels below the exposure limit, either due to individual differences or due to existing health conditions (such as pregnancy, cancer treatment, or recovery from an illness, heart, or lung disease).

School principals highly stressed over workplace violence

Nearly 43 per cent of school principals triggered a ‘red flag’ email in 2023, indicating serious psychosocial risks, potential for self-harm, or serious impact on their quality of life, according to a recent research report. It also found that 54 per cent of principals reported being subjected to threats of violence (up from 49 per cent in 2022), 48 per cent reported being subjected to physical violence (up from 44 per cent in 2022), and bullying levels also rose to 38 per cent (up from 34 per cent in 2022). The most recent Australian Principal Occupational Health, Safety and Wellbeing Survey, which was conducted by the Australian Catholic University (ACU), also found that principals were concerned about the welfare of staff and students. ACU investigator and former principal, Dr Paul Kidson, said the numbers represented a substantial increase, which pointed to a worrying trend supported by the other findings. “It is a drastic increase when you look at the whole picture,” Kidson said.

How to improve RTW programs through early intervention

There are a number of early intervention strategies that are likely to improve return to work outcomes for workers, employers, and insurers, according to a new report. While there is a high level of understanding and belief in the importance of early intervention to improve work outcomes for injured and ill workers, the report found more can be done to improve the effectiveness of early intervention in return to work programs. The Early Intervention in the Workers’ Compensation Process report, compiled by Monash University for Safe Work Australia, emphasised the crucial need for stakeholders to systematically evaluate their existing projects involving early interventions. Ideally, the report said a national evidence-based framework or criteria could be co-developed to guide this. “This would enable a shared understanding of what works/does not work in the setting of Australian workers’ compensation schemes,” said the report, which also suggested creating more opportunities for open collaboration, partnership, and sharing around early intervention in return to work schemes.

Minimising misunderstandings: the role of OHS in risk management

In the recent Dr Eric Wigglesworth Memorial Lecture, Professor Tim Driscoll discussed the importance of clear and honest communication about workplace risks to help workers make informed decisions

It is important not to pretend that there is zero risk of an adverse outcome when it comes to managing and minimising risk, unless there is actually no exposure to the hazard that creates a risk, according to Dr Tim Driscoll, professor of epidemiology and occupational medicine in the faculty of medicine and health at the University of Sydney. Instead, he said it is much better to try to quantify the risk (even on a qualitative basis) and that this should then be communicated to the potentially affected people (such as workers or sometimes members of the general public) in clear, simple ways.

He recommended sitting down with those involved or exposed to a risk to find out what they are concerned about and answer their questions honestly. “If there is uncertainty about the size of a risk, say so,” said Driscoll, who recently presented the Dr Eric Wigglesworth Memorial Lecture as part of the AIHS National Health & Safety Conference in Melbourne. “Try to put the risks in perspective, so that others can make up their own minds as to whether that is something they should worry about. This is easier said than done, of course, especially when the absolute risk is very low.”

There are a couple of ways that WHS professionals can help in the process, according to Driscoll. The first is to provide guidance in terms of the absolute increase (or decrease) in risk arising from a hazard, even just in a qualitative way, and how to interpret this. Helping organisations and workers to understand the difference between absolute and relative risk can also be important, especially when there is concern about potential media articles reporting what seems to be a high relative risk, he said.

Help with advising organisations, or facilitating discussions between management and workers about exposures and the risks they might entail, is also important. This can be particularly helpful when the risk is very low, Driscoll said. “Words or phrases such as ‘negligible’, ‘minimal’, ‘essentially zero’, ‘not worth worrying about’… All of those might be used but all also have some problems – particularly the last one, because each of us have our own idea about what is worth worrying about,” he said.

“I use a few different approaches, but the one I have settled on commonly is ‘no meaningful increase in risk’. That runs the risk of being interpreted as ‘not worth worrying about’, but when there is scope for discussion, most people find it helpful.” Of course, if the risk is not low, he said this needs to be made very clear and, wherever possible, the risk should be controlled so that it is low.

Challenges in understanding risk

Driscoll also said there are several challenges faced by organisations in terms of understanding risk and helping others (such as workers or the public) to understand risks they might face in the course of their work. Focussing particularly on illness, he said many organisations appear concerned that in admiting there is a ‘risk’ of harm, they might ‘unnecessarily’ worry their employees, or might open the organisation up to claims for compensation.

“In some situations, it can be hard to gain a good understanding of the risks. Many people don’t understand the difference between relative risk and absolute risk. Many don’t understand the difference between hazard and risk, or how risk varies with level of exposure. People understandably don’t want to face extra risk of something bad happening if they can avoid it; they commonly want to be reassured there is no extra risk arising from the particular work activity or exposure they might be concerned about,” he said.

So, Driscoll said there can be a tendency for organisations to downplay risks, or to say there is ‘zero’ risk. Instead, a key concept is that, in most situations, the only way to have no risk is to have no exposure. In contrast, he said organisations can sometimes

inadvertently create worry and anxiety in workers (or the public) by being overly cautious, or highlighting a hazard for which the risk of illness is extremely low.

“This runs the risk of creating ill health by making people anxious. The recent issue of asbestos contaminating garden mulch is a good example of that. For the general public who spent time in parks or gardens, essentially all of them would have had a very, very low risk of being exposed to airborne asbestos fibres, and so their risk of any asbestos-related disease as a result would be very, very low,” said Driscoll, who added that the risk was perhaps not zero, but very close to it.

Organisational shortcomings on risk

While most workplaces have hazardous exposures of one form or another, Driscoll said most organisations probably don’t have a good understanding of the true burden of ill health arising from these exposures. In terms of injury risks, he observed that organisations are generally pretty good in terms of communication with their workers. “Injuries and the hazardous circumstances leading to them are likely to be well recognised because they are easily observed and the connection to work easily seen (if a person falls from a ladder and breaks their wrist, for example) and easily explained,” he said.

However, he said this is much less likely when it comes to illness (for example, if a person is diagnosed with lung cancer 30 years after they started work as a tunneller). “These types of work-related disorders are much harder to appreciate for a range of reasons. There might be a long delay – many years in some cases – between the causative exposure and when the worker develops symptoms. The worker might have retired by then or moved to another workplace. The worker and their doctor might not suspect the connection between their past work and their illness,” he said.

It is also important to understand and communicate the difference between relative risk and absolute risk. Driscoll observed that many organisations are not experienced or skilled at recognising these problems and communicating with workers about them.

Michelle Price on the path to AIHS Fellowship

AIHS Fellow Michelle Price discusses her career path, contributions to the field of OHS, the benefits of Fellowship, and why it is important to give back to the profession

The College of Fellows was established in 2002 and comprises members who are Fellows and Honorary Fellows of the AIHS. As a senior network of the Institute, the College works to support the Institute’s vision, values, and strategy. Membership of the College recognises OHS professionals who are making a substantial ongoing contribution to and have a record of achievement in the field.

With this in mind, the AIHS encourages members to aspire to be Fellows. By highlighting volunteering opportunities and participation in the various activities of the College, they can gain greater peer recognition, personal satisfaction, and impact.

Michelle Price is one such member, who recently stepped up to become a Fellow of the AIHS.

The journey to Fellowship

Price commenced her professional career as the first in her graduating class with a three-year role as a hydrologist and water scientist with what was then the Department of Water Resources. Motivated to pursue health and safety, she then moved into the university sector. She spent a decade improving organisational health and safety, audit and risk governance, identifying deficiencies, and developing solutions to reduce risks and safeguard workers.

“I view my acceptance as an AIHS Fellow as the progression of my career and a learning curve”

In 2012, after the roll-out of the then new 2011 WHS model legislation in NSW, Price took up a new opportunity in NSW Health - first with Ambulance NSW as the Metropolitan WHS Coordinator and then with Sydney’s local health district in a variety of roles.

Price says that becoming a Fellow was personally important to her, as she wanted to give back to her chosen profession and share the learning and knowledge she had gained from others. “I see a Fellow as a professional who is integrated into a group of like-minded individuals, and who can astutely influence both government and business leaders at the highest professional level,” she said.

Price explained that Fellows possess peer-reviewed knowledge and skills to understand and help make smart, simple, but beneficial changes to public sector and business governance knowledge and policy changes. “Personally, I’ve always tried to simplify and communicate the benefits of a robust business-integrated safety system. I want to ensure that health and safety is a rewarding career path, no matter how you get into it. Most of us have moved sideways or ‘fallen into it’,” she said.

Stepping stones to Fellowship

Although Price had been an active member of the Institute since 2000, she decided to gain certification to demonstrate her knowledge and skills formally. She has always been a fearless supporter of what accrediting health and safety professionals brings to the profession.

As an active member of the NSW Branch of AIHS, Price contributes to policy and the AIHS mentoring program. Her mentoring has seen passionate staff like herself, who ‘fell’ into work health and safety, fall in love with it. She has also taken up opportunities to bring change to staff mentality regarding what safety is and what it means to make implementation a seamless workplace experience.

Price considers herself to have been “very lucky” in all of her roles on the journey to becoming a Fellow, in that she has been able to share the journey with

committed colleagues at all levels. “They have given me such valuable information and guidance that I never felt I could fail professionally. I also wanted to ensure that my knowledge was on par with the highest levels of our profession,” she said.

“While the AIHS (or SIA as it was when I first joined) has always been about networking, peer learning, and mentoring through events, webinars, and face-toface conferences, it has recently become more governance and strategy-focused,” she said. “What’s so vital for my skillset is attending state-based events or even interstate branch meetings and the AGM to further my development. Every single one of these activities has allowed me to meet and mix with my colleagues in the safety business and learn as I grow on personal and professional fronts.”

The benefits of becoming a Fellow

There is almost “no end” to the benefits gained on her personal journey to finally achieving her goal of being a FAIHS, according to Price. “I also think the journey to being admitted as a Fellow is as individual as our members are,” she said. “I view my acceptance as an AIHS Fellow as the progression of my career and a learning curve. In my journey, I’ve had the ability to mix with true visionaries and WHS leaders, especially since my Master of Safety, Health and Environment from UNSW (which sadly is no longer available). This cemented the knowledge I had gained as a health and safety representative and OHS committee member, when I first migrated from quality management systems auditing into a role implementing a new WHS management system.”

Other benefits include the ability to mix with like-minded professionals, not just within Australia but internationally, who hold her values, ethics, and passion for enabling all levels of staff to go home without harm. “Being a Fellow requires me to uphold a core set of work and education values that are my basic core values anyway,” Price said.

She gave the example of working during COVID, embedded as a WHS manager in a hospital under NSW Health. “I was the only person in the facility whose job it was to ensure that our staff were safe and protected from what was then an unknown and highly infectious pathogen,” she said.

“I was dedicated to looking after the physical and psychological aspects of every staff member, including doctors, nurses, back of house corporate and admin staff, as well as sub-contractors most likely employed by engineering to do specialised

work,” said Price. “I loved that 10-year role because I believed it was a privilege to be the contact point for staff advice, guidance, education, and support when they needed it, to ensure issues affecting them were resolved, minimised or, at best, eliminated.”

Workers’ compensation and psychological injuries

As a professional who works tirelessly in the preventive space, Price knows the workers’ compensation path is never ideal for workers to need or use. “If there is an injury at work, this means that some part of the preventative system of work safety that professionals like me implement has failed,” said Price, whose community commitments include Carers NSW, NSW Mental Health Carers Network, Physical Disability Council of NSW, and local government.

“I see a Fellow as a professional who is integrated into a group of like-minded individuals, and who can astutely influence both government and business leaders at the highest professional level”

Workers’ compensation is a challenging system to navigate or even be involved with, as Price said long-term injuries that are deemed not to be the worker’s fault are treated negatively by the public and media. “For example, in NSW, you can have an insurer-accepted injury incurred in the course of your work, but regardless of your fitness for work, the insurer and business can legally sack you after six months because you are unable to go back into your pre-injury duties fully,” she said.

Price also observed that psychological injuries are generally unlikely to heal in six months to the point where an injured worker can fully go back to their role. This creates an issue for good staff who might lose their job just because a psychological injury takes longer to heal – but Price noted

that workers’ compensation laws have not changed to reflect this. “Furthermore, if they don’t lose their job, workers’ compensation laws allow for workplace-injured workers to receive 70 per cent of their pre-injury salary, which is not remotely fair in what is supposed to be a ‘no blame’ system,” she said.

“For any leader wanting to be a WHS role model, I always suggest their best and most important work will be preventing the psychological injuries they are now responsible for managing, with kindness and respect to the home life people have – and then to the staff who may have incurred a compensable psych injury over COVID (for example, due to work burnout or fatigue, which was a huge staffing issue for hospitals),” said Price.

“I ask the leaders to walk in their staff’s shoes and show empathy, compassion and, most of all, kindness for their work. Hospital staff, especially those who might be public servants, simply care about their patients. I ask our leaders: if this was their relative, wouldn’t they want the staff in that facility to look after their patients as if they were their own family? I’ve never had a ‘no’ in response to that question.”

Advice for members aspiring to become Fellows

Price had some parting words of wisdom for those aspiring to become Fellows. “Just work towards being the best you can be,” she said. “Be curious and ask questions to give you a feel for what the actual issues are. Seek the truth. Be accountable for all of the information or instruction you give others. Always be ethical in dealing with all staff levels.”

Other necessary steps are to create meaningful WHS and ESG lead indicators, KPIs, and SMART goals for all staff performance appraisals, and to leave the lag indicators to HR and workers’ compensation to monitor. This is because innovative and human-focussed lead indicators enable real and meaningful business leadership and genuine WHS change.

“Be kind in all interactions until you get a real idea of the issues and the ‘how’ and ‘why’. And remember, every person in our workplaces has something that could hold them back from bringing their A game or just being all they can be in their role – whether it be having a disability, being a carer, being a parent, being new to their role, or not having English as a first language. Every person in a workplace is a person, so ask yourself how you can make your workplace one where you know every person goes home to their family at the end of every shift, each and every day,” she said.

Silicosis and beyond: managing the risk of airborne contaminants

The rise of OHS risks such as silicosis and other airborne contaminants necessitates stringent safety measures to protect workers and improve compliance

Airborne contaminants present significant challenges in occupational health and safety (OHS) across most Australian industries. These contaminants – dust, fumes, vapours, biological agents, and others – pose risks to workers’ overall wellbeing, potentially leading to acute and chronic health issues. Understanding and mitigating these risks is crucial for maintaining a safe workplace and ensuring compliance in accordance with Australian regulations.

Silicosis and black lung disease are prominent examples of the health risks associated with the chronic inhalation of airborne hazards at a large number of Australian worksites. Silicosis, caused by inhaling crystalline silica dust, is a significant concern in industries such as construction and mining. In particular, it has made headlines regarding its use in the manufacturing and installation of engineered stone. Emerging risks, such as exposure to welding fumes, are also gaining increased attention. Welding fumes contain a complex mixture of metallic oxides, silicates, and fluorides, which can lead to serious health issues, including respiratory diseases and lung cancer. These risks are faced by workers in sectors where welding processes are prevalent, including construction, automotive, and advanced manufacturing.

Engineered stone and silica dust

Addressing these risks is crucial due to the increasing regulatory pressure and compliance requirements set by Safe Work Australia and other state and territory bodies. Notably, Safe Work Australia has introduced stringent measures to control silica dust exposure, including the upcoming ban on uncontrolled dry cutting of engineered stone. This has been followed by the Workplace Exposure Standards for Airborne Contaminants update, which mandates stricter exposure limits and more rigorous control measures for harmful substances. Different industries need to be aware of the impact of these regulatory changes, such as the changes associated with crystalline silica dust and its potential impact on businesses, according to Peter Aspinall, principal

occupational hygienist for WSP (Australia & New Zealand). “If you can demonstrate that you are actively and effectively managing your risks on-site, then you should be able to continue your work. But with the recent focus on silicosis, the businesses out there that are not currently even complying with the older exposure standards are the ones that are now paying the penalty,” he said.

“It has pushed a lot of businesses to a point where it’s not viable for them to introduce all these controls and such, so these changes are kind of weeding out some of the cowboys. However, it is also impacting on some of those businesses that are trying to do the right thing, such as family businesses that have been in operation for a long time, who need support making those changes. So the past two years have been very interesting, particularly with regards to silicosis and the stone benchtop industry.”

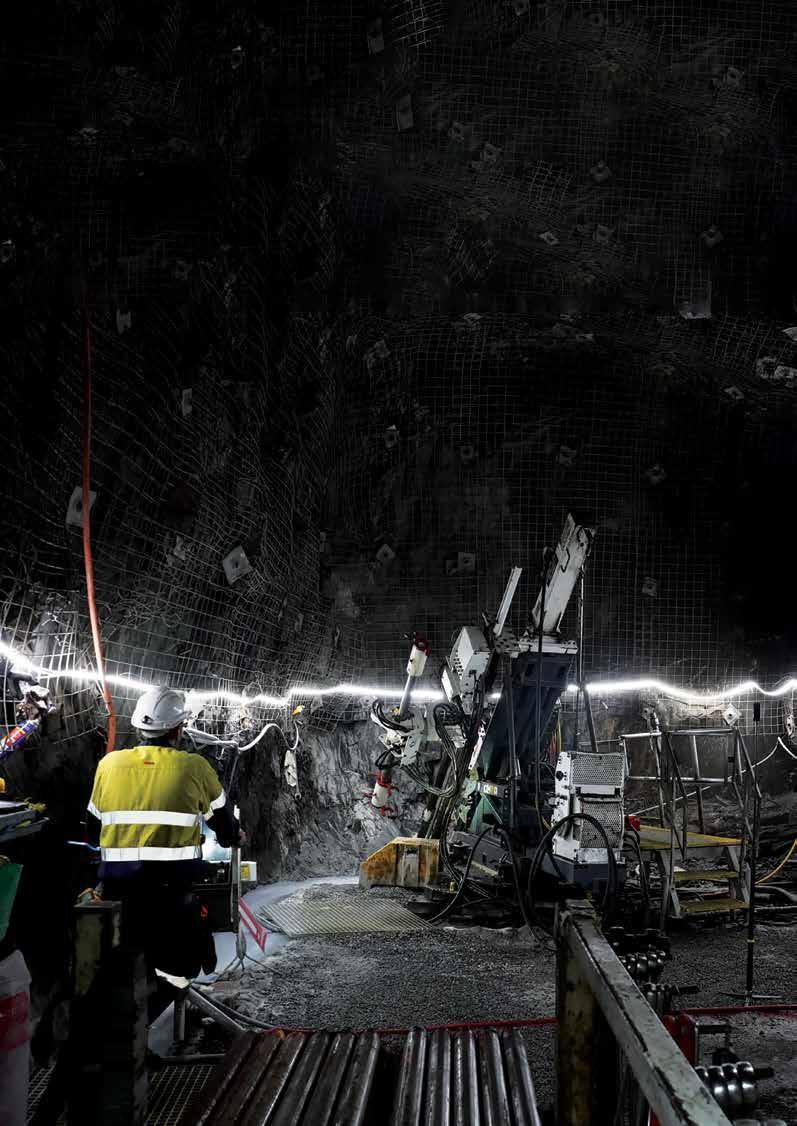

Alex Virr is chief technology officer at CleanSpace Technology, an Australian owned manufacturer of advanced respiratory protection solutions in the form of powered air purifying respirators (PAPRs) He said the ban on engineered stone makes “plenty of sense” given the risks associated with silica dust. He also comments that there are many other forms of dust that contain silica that present a range of OHS risks. “We haven’t banned all sorts of materials that also have silica in them, and there are many sources of dust that contain silica. In somewhere like a mining tunnel, for example, you don’t know how much silica there is because you’re just boring through. I feel like it would be safer to have a more general focus on just excluding dust that may contain silica, for example, and not get too worried about exactly what the material is that’s the flavour of the month,” he said.

Diesel particulate and welding fumes

Apart from silicosis, Aspinall said diesel particulate is going to become “very much a concern” for a lot of workplaces in the near future. Diesel particulate has traditionally been seen as an issue for the mining industry where employees work in underground environments. However, the

rising concern around diesel particulate is extending to other sectors that use diesel-powered machinery. “We have diesel forklifts going in and out of cold rooms, for example,” he said. “So there are some concerns around this, but my gut feeling is it’s probably not as bad as the underground application concerns. While there are some changes happening with the electrification of equipment and vehicles, with less diesel engines operating on the ground, it’s about quantifying that risk and whether higher order controls are required.”

“Welding fumes in particular are an issue for most industrial application workshops that do welding”

Another emerging and potentially significant risk involves exposure to welding fumes. Aspinall said this will be a “big one” for OHS: “Welding fumes in particular are going to become an issue for most industrial application workshops that do welding. There are a lot of them out there. Some places may only weld 15 to 20 minutes a day with certain tasks or patching up a job

with a couple of fixing welds, but there are other workplaces out there that are consistently welding eight hours a day, all day, every day,”he said.

Safe Work Australia also released updated information regarding limits for airborne contaminants recently. For instance, workers must not be exposed to total levels of welding fumes greater than 1 mg/m3 over an eight-hour working day, based on a five-day working week. “One of our biggest markets is people welding galvanised steel. I don’t know if you’ve welded this steel, but it produces a cloud of what is actually very fine particles. There’s some gas mixed in there too, but it’s the fine particles that block up filters faster than almost anything else for our customers. It’s super fine material and it cannot be good for you,” said Virr, who added that the potential risks of airborne contaminants such as welding fumes can be amplified in enclosed spaces without adequate ventilation, such as in underground mining or the tunnelling industry, which are prone to a range of airborne contaminants.

According to Virr, there is an increased perception that legislation will be introduced and this in turn will require workers in the tunnelling industry to wear a PAPR. “We’ve had customers coming to us on the basis that they’ve been told they have to wear a PAPR, but they’ve never heard of one before. So things are changing, and they do

need a higher level of protection and a more reliable protection system than they’ve used in the past for whatever reason,” he said.

Steps for OHS professionals

In managing increasingly complex operational and compliance concerns about risks associated with airborne contaminants, Aspinall said it is important for OHS professionals to be confident with their skill sets, and understand where their strengths are and the point at which they need to ask for assistance. “In a lot of cases, we get OHS professionals who say they have got respirators and hearing protection for their workers, but how do you know they have the right one? How do you know that’s the right equipment? What was your risk assessment that said it is the appropriate product?” he asked.

Aspinall said it is critical for OHS and occupational hygienists to open the lines of communication, particularly when it comes to certain industry and organisation risks such as diesel particulate in underground mining. “OHS and occupational hygiene do need to be talking to each other. That needs to be coming from the top, and it might also involve legal and risk in terms of exposure. So it’s about getting the right kind of buy-in or stakeholder support to minimise the risks and make sure they’re taking a proactive approach in terms of compliance and looking after their workers,” he said.

It is also important to involve the right stakeholders, such as occupational hygienists, in determining appropriate products to minimise risks, Virr added. He gave the example of PAPRs and said that employers can underestimate the difference between going from an unpowered negative pressure system to a powered positive pressure system and the difference this can make in a dangerous environment (such as a tunnel) which may contain a lot of silica dust. “If you can pick any reputable PAPR, from an engineering point of view, the problem virtually disappears in this sense that when you have an unpowered system, you are completely dependent on the seal of the mask,” he said.

The seal and overall effectiveness of unpowered respirators are impacted by factors such as stubble, dirt, sweat, or changes in the shape of the face. However, Virr said that powered respirators (such as those manufactured by CleanSpace Technology which provide levels of protection up to 99.97 per cent) create a positive pressure, so this reduces the risks associated with such elements. “They just take all of the difficulty out of it. That’s the main point I would like to make to people who are looking at respiratory protection: that there is a big difference between powered and unpowered respirators,” he said.

CleanSpace Technology is a diamond member of the Australian Institute of Health & Safety.

Leading by example: the AIHS mentoring program

The AIHS mentoring program aims to facilitate knowledge sharing and personal growth among OHS professionals

The Australian Institute of Health and Safety (AIHS) mentoring program is a cornerstone initiative within the broader strategic framework of fostering excellence in WHS. At its core, the program aims to cultivate enhanced skills within the WHS workforce, expand career pathways, and drive demand for WHS expertise, according to Ben Kirkbride, Chair of the mentoring committee.

Since its inception, Kirkbride said the AIHS mentoring program – now into its seventh cohort – has seen remarkable success and achieved significant milestones. “Mentors and mentees alike have benefited from valuable insights, professional development opportunities, and networking connections. These interactions have not only contributed to individual growth but have also fostered a sense of community within the WHS profession,” he said.

Looking ahead, Kirkbride said the program is poised for further growth and evolution. As the AIHS continues to expand its education and training resources, he said the mentoring program will play a vital role in supporting this endeavour. “With a focus on fostering diversity and inclusion, the program also aims to showcase inspiring career pathways and promote new certification opportunities, ensuring that the WHS profession remains vibrant and accessible to those that hold current AIHS memberships,” he said.

For those considering participating in the program (whether as a mentor or mentee), Kirkbride offered some advice. Firstly, he suggested approaching mentoring as a two-way street, where both parties have valuable insights to share and learn from each other. Secondly, he said to embrace networking opportunities and actively engage with the broader WHS community to expand your professional horizons. “Lastly, be open to feedback and growth, as mentorship thrives on mutual respect and a willingness to learn,” he said.

“In recognition of the invaluable contributions of current mentors, the AIHS extends its sincere gratitude and appreciation.

Their dedication to driving excellence in workplace health and safety exemplifies the spirit of collaboration and mentorship that lies at the heart of the AIHS mentoring program.”

A case study of mentoring in action

Peter Johnston is an AIHS mentor, Chartered Generalist OHS Professional and a Fellow of the Australian Institute of Health and Safety College of Fellows. With a wide range of experience in mechanical engineering, HR, occupational risk, workers’ compensation and injury management across sectors such as chemical, mining, automotive, and food manufacturing,

Johnston said there were a number of reasons he wanted to mentor others. “I enjoy assisting employees with their health and safety while ensuring that operational interface arrangements are safely implemented,” he said.

“Importantly though, my thoughts on mentoring fall back onto our Institute values and, in more recent times, my pledge as a member of the College of Fellows. Key for me is to ‘act ethically and with integrity’ and to ‘foster and encourage the Institute and its members to advance the knowledge and activity of the profession.’”

For many years, Johnston has also been lecturing in both the Certificate IV

and Diploma WHS programs and working with students from a number of tier one employer groups. “When the opportunity arose with the mentor program a couple of cohorts ago, I felt that this was a great opportunity to support the Institute and, specifically, people who are wanting support to progress within the profession,” he said.

In reflection, he said the program has allowed him to challenge himself and has provided enormous satisfaction through the positive progression of people within the profession. “As a mature person working within the profession since 1985, I have had significant experience in both national and international roles. Both the education and mentoring programs provide me the opportunity to give back, and have conversations that allow me to reflect on my experience and strategies that have been successful and those which provided challenges and learnings,” he said.

Johnston is currently mentoring Jemma Imanova, a WHS&E engineer who joined the AIHS mentoring program after relocating from overseas. There were two reasons Imanova joined the program. “First, I wanted to connect with a professional in the health and safety field. Communicating and being guided by a professional to ask industry-specific questions, share ideas, and gain insights from their experience just seemed invaluable,” said Imanova, who said the mentorship program offers a chance to learn from the best and accelerate her own health and safety knowledge and skills.

Second, she was eager to gain a broader perspective on the health and safety industry. “The program puts mentees in touch with a mentor who has navigated different career paths within health and safety,” she said.

Imanova said the mentorship program has definitely lived up to her expectations. “Having a dedicated mentor has been a fantastic resource,” she said. “For example, I was recently tackling a tricky project at work, and my mentor offered invaluable advice on best practices and potential solutions. It was a huge confidence booster to have his expertise in my corner.”

Beyond specific situations, she said the program has also helped her develop her overall professional network. Through events and interactions with other mentees, she has met some great people in the health and safety community. “These connections could prove valuable down the line, whether it’s for collaboration opportunities or simply expanding my professional circle,” she said.

In terms of her future focus, Imanova said the mentorship program is perfectly aligned with her goal of becoming a leading

health and safety professional. “The knowledge, skills, and network I’m gaining are all crucial building blocks for my future career. I’m confident this experience will give me a competitive edge in the job market and help me land my dream health and safety role,” she said.

“I’m confident this experience will give me a competitive edge in the job market and help me land wmy dream health and safety role”

“If you’re even remotely interested in health and safety, I can’t recommend the AIHS mentoring program enough. It’s a fantastic opportunity to learn from experienced professionals, develop your skills, and connect with others in the field.

Johnston said he was privileged to be

able to work with Imanova. “We did not use the online program on all occasions,” he said. “We both felt that we have a level of trust and confidence in being able to work at a personal level which considered elements such as family, workplace, and university. Through our conversations and document reviews, the bottom line is to enable Jemma to have a clear pathway for progression and her next steps. I observed Jemma learning from our communications, and saw a consolidation of her passion and determination to achieve and meet deadlines while maintaining a family.”

In recognition of this, Imanova recently received a letter of commendation from Professor SueAnne Ware, the Head of the School of Design and the Built Environment at Curtin University (where Imanova is currently studying a Masters in Environment and Climate Emergency). The letter commended Imanova on her academic performance, her personal commitment to her studies, and her contribution to the reputation of her degree.

For more information about the AIHS mentoring program and how to get involved, visit the AIHS website.

AIHS mentoring program: Recognition and thanks to mentors cohort 7

Annette Sommerville

Trent Yeo

Bryce Gregory

Veronica Cooper

Angelica Vecchio-Sadus

Andrew Sloan

Greg Stagbouer

Damian White

David Howard

Alissa Webster

Gerard Forrest

Sajan James

Gordon Smith

Eddie Bugajewski

Steve McNair

Ben Kirkbride

Kelvin Genn

Gregory Chrisfield

Bruce Vernon

Barbara Cooper

Tim Allred

Nan Austin

Michael Eather

Symone Mercer

Katie Watson

Anthony Bate

Harshal Jain

Danielle Stalker

Peta Mercieca

David Whitefield

David Trembearth

Peter Brian Johnston

Ryan Baldwin

Kenneth Charles Patterson

Daniel Grivicic

Abigail McPherson

Shona Backers

Michael Hagan

Sonia Correa

Paul Kozina

Owen Bevan

Kristine Cotter

Stephen Weber

Kim Schulz

Craig Ramadge

Abhijit Prasad

Katie Weber

John Christie

Mark Philippi

Kim Whale

Susan Allen

Jeremy Clay

Mark Devlin

Dean Matthews

Stuart Rawlins

Courtney Newman

Phil England

Philip Powh

David Clancy

Melita Caffery

Graham Campbell

Lisa-Marie Dembski

Peter David Hedger

Mary Kikas

Kevin Figueiredo

Louise Vella Jurd

Vlad Doguilev

Sanzid Alvi Ahmed

Glenn Jordan

Michael Hall

Robert Dunn

Braham Tindale

Catherine Jeffries

Michael Polito

Donella Redclift

Martyn Campbell

Mano Raghavan

James McGuire

Lois Frances Hutchinson

Justin Haddock

Robert Whiteside

Matthew Mark Gauthier

Marilyn Hubner

Leading the regulator: Trent Curtin, SafeWork NSW

Head of SafeWork NSW, Trent Curtin, speaks with OHS Professional about trends, challenges, and priorities for the regulator

Trent Curtin commenced the role of head of SafeWork NSW in October 2023. He is responsible for leading the WHS regulator’s operations, improving compliance, and leading the regulator’s transformation following an ongoing independent review of its operation by Robert McDougall KC. Curtin was formerly the acting deputy Commissioner for Fire and Rescue NSW and the national spokesperson on fire safety regulation and compliance.

What are the priorities that SafeWork NSW will be focusing on over the coming 12 months?

SafeWork sets its regulatory focus from various data and intelligence sources, as well as lived experience and inspector observations.

It has also been informed by recent reviews by McDougall KC and the NSW Audit Office. SafeWork, as a portfolio of the NSW Minister of Work Health and Safety, is currently in the process of finalising those priorities for 2024/2025 and will continue to focus on priority risk areas.

These priorities will align with high-risk harms and injury mechanisms identified in the Australian WHS Strategy 2023-33, such as falls, moving plant, psychosocial health and safety, dust diseases, and cancers.

These decisions are based on a range of criteria, including evidence from workers’ compensation injury claims and incident data, research on enduring and emerging high-risk harms, as well as alignment with the Australian Work Health and Safety Strategy’s identified harm priorities. We will continue to be informed via tripartite collaboration with the government, business, and unions.

How is the role of SafeWork NSW as a regulator currently evolving?

SafeWork has a multifaceted approach to interacting with government and employer organisations, unions, and injured workers, all of whom have a clear ability to influence safety culture. Larger and well-resourced organisations are not always prioritising

Head of SafeWork NSW, Trent Curtin, says WHS risks typically persist due to shortcomings in leadership and a lack of genuine consultation with workers on solutions to WHS risks

sufficient effort towards health and safety, particularly relating to psychological health and safety.

“Larger and well-resourced organisations are not always prioritising sufficient effort towards health and safety, particularly relating to psychological health and safety”

Our interactions include providing advice and education, inspections, investigations, and prosecution when necessary to achieve compliance with WHS laws.

WHS risks typically persist due to shortcomings in leadership and a lack of genuine consultation with workers on

solutions to WHS risks. Every worker has the fundamental right to come home safely from their working day. As a regulator, we look to work with employers to bring about improvements in workplace safety by raising awareness and encouraging leaders to embed good practice.

Working in partnership with government agencies and employer organisations and unions, we balance our efforts. Larger and well-resourced organisations can expect swifter, more robust regulatory actions and enforcement as there are obvious duty holders and accountable officers.

With a lift in the performance of major employers with influence, such as government and big businesses, SafeWork can focus more effort towards small and medium businesses and industries, businesses, and hazards that require more support.

How do you see this evolving and what are the major trends that will impact SafeWork NSW and employers?

Over the next three to five years, SafeWork will invest further in data and evidence-based risk reduction efforts to identify new and emerging WHS harms. By improving our systems and harnessing data analytics and insights, we will identify and address workplace hazards and high-risk industries more proactively and effectively.

We need to emphasise a preventative stance that enhances our capacity to anticipate and respond to newer and emerging risks, including gig work and other risks arising from contemporary research.

We will focus more attention on ensuring effective consultation mechanisms and supporting the important work of health and safety representatives.

We are also aligning with trends outlined in the National WHS Strategy 2023-33. These include the changing nature of work, new technologies, psychosocial harms, and the changing nature of workers and the workforce.

What do you notice among ‘best practice’ organisations that consistently have good OHS outcomes?

Organisations with good WHS outcomes are always led by strong leaders who are well-informed of issues in their workplaces and place safe work culture at the centre of their business. They invest in genuine consultation with workers and their relevant unions in finding innovative solutions to work health and safety issues.

When SafeWork inspectors visit worksites, they look out for well organised, clean, and tidy places, which show respect for their workers. This is most easily noticeable around amenities and other shared spaces.

We also look for appropriate safe work procedures, which are not complicated, in the workers’ language, and reflect how work is completed – not just an instruction manual.

What advice would you offer to organisations looking to improve their OHS outcomes?

When SafeWork is on-site, we want to see a culture where even the smallest risks are appropriately considered, and not just left to an administrative control or simple PPE. Strong WHS leaders invest in removing risks where possible and ensure employees are properly trained to handle any incidents that may occur.

This is especially important when working with employees who are young, new, and inexperienced or who are employed on a casual basis. There must be appropriate induction and education, along with proper supervision around hazardous tasks.

While SafeWork’s education can be focused on supporting smaller businesses, which make up a large percentage of Australian employers, we look for WHS leaders who support and work with health and safety representatives to ensure

effective solutions to WHS issues.

When looking at larger workplaces, inspectors will focus on understanding how the psychological health and safety of employees is being managed, as this can often be disregarded or overlooked. Businesses should have their key focus on systems that prevent the occurrence of incidents that could cause psychological harm. Whist systems to respond are always important, prevention is key and will save businesses significant time, effort, and money. Businesses should also keep up to date with relevant codes of practice and should never cut safety for the sake of productivity or profit.

As workplaces change and ways of working continue to evolve, there will be risks emerging that will need to be addressed and WHS professionals need to be agile in addressing these issues. This includes a greater awareness of psychosocial risks and the emergence of the gig economy.

Holistic safety: integrating safety into the DNA of an organisation

A

holistic approach to OHS, incorporating leadership, culture, processes, systems, and continual improvement, is critical to safety performance, writes

Craig Donaldson

Good OHS is more than a onedimensional functional pursuit, and is more about fostering a work environment where everyone feels empowered to identify hazards and make risk prevention a top priority. A holistic OHS approach transcends addressing physical hazards and focuses on the bigger picture. Leadership styles, the organisational culture, established processes, and existing systems all play a crucial role in workplace safety.

Imagine safety as a well-built house. Robust regulations and clear procedures form the foundation, providing a solid base. But a secure roof – supportive leadership that champions safety – and strong, well-maintained walls – a positive safety culture where everyone feels comfortable raising concerns – are equally vital for complete protection. A holistic approach allows for the building of this complete structure, ensuring long-term safety and wellbeing for all workers.

Instilling a culture where safety is ingrained into every aspect of the organisation’s DNA requires a concerted effort at all levels, from leadership to frontline workers, as well as a commitment to transparency, communication, and collaboration. From redefining safety strategies to practical implementation at the operational level, the following three organisations (Mitchell Services, Cumberland City Council, and Powerlink Queensland) are taking a more holistic approach to safety that transcends compliance to build cultures of resilience, trust, and empowerment.

How Mitchell Services makes OHS business as usual

Mitchell Services is an Australian-based drilling company with more than 800 employees working across Australia, serving multiple clients in the surface and underground mining and exploration industries. The business faces significant challenges in managing the various systems and contractual requirements that must be met, all while managing high-risk activities.

There are a few standout challenges the business is currently facing, according to Josh Bryant, GM people, risk and sustainability for Mitchell Services. “It is a trend being experienced by businesses globally where some of our experienced people are leaving the business and it is showing that not only do our systems not necessarily capture their skills and knowledge (retention), but also that they were adapting in our system and covering for some its short falls. So, we need a way to really expose

and learn from those system weaknesses now. Identifying and addressing these ‘weak signals’ is crucial,” he said.

The business is also introducing new equipment that has had a positive impact in decreasing the amount of manual handling that its personnel have do as part of their roles. No matter how many change management processes the business goes through, Bryant said manufacturers have not necessarily involved operations in equipment design and use. As a result, he said some changes have made the job more difficult for operations personnel, or that it does not make sense for them to now have to do things a certain way. “We must ensure that changes are practical and gather feedback to learn from necessary adaptations,” he said.

Psychosocial safety is also a priority, in terms of groups working in small teams and the business’ role as a contractor working for clients. “There is an expectation of safe operations whist delivering on client requirements, where that be production or quality goals. Our challenge lies not in the relationships between members of the teams, as we find our teams are quite social, cohesive, and welcoming. It’s us understanding the conditions they face, where they are having to make trade-offs, and what the interactions are with our clients. We strive for genuine partnerships rather than traditional contractor-client dynamics,” said Bryant, who explains that open dialogue with the workforce and transparency with clients are essential in addressing these issues.

The evolving role of HSE within the business has also presented challenges, said Bryant. “We really have moved away from the traditional role of being some sort of ‘compliance officer’ and our role as WHS to audit, check, and investigate. We are finding that we have transitioned to more operational improvement and being a conduit for information flow between groups,” he said.

This is not something people new to the business are used to in their roles, so Bryant said it is important to enable them to be able to interact and build trust with different stakeholders in the business in order to unlock operational learning and operational value. “We are actually improving the safety of work,” he said.

Key elements of Mitchell Services’ WHS strategy

The business’ WHS strategy, influenced by Forge Work’s Map (a free resource), marks a shift from compliance to enhancing resilience and genuinely improving workplace safety, according to Bryant, who also identified four primary areas the WHS team and organisation focuses on as part of its strategy: Systems of work and work management. This is about being proactive about improving and learning from frontline work that feeds into improving safety of work and risk management systems in support of the frontline. “This is reviewing the effectiveness of our systems and whether they are doing what they are meant to, rather than just seeing them as

a bunch of activities to be counted. This includes how we deliver our training, so that we achieve our ISO certification and that it adds value and is not just ticking a box, and doing reviews of our processes so they reflect the realities of their use in the field,” said Bryant.

Operational learning to build resilience and operational excellence. It is crucial that leaders understand the importance of their responses to events, which helps in building trust and facilitating learning from experiences by shifting focus from ‘who failed’ to ‘what failed’. “We prioritise practical engagement with work processes over mere safety paperwork and identify systemic issues as a key learning point from events,” said Bryant.

Management of critical risk. Reducing operational risks with controls that are not only present but effective and userfriendly is a priority for the business. “Our approach to critical control failures or improvement opportunities focuses on learning and enhancement rather than merely completing verifications,” said Bryant, who adds that WHS are involved in operational discussions regarding improvements in work design that can apply a human factors/error tolerance lens with controls.

Influencing stakeholders and inbound business support. Operational leaders in the business drive processes with a clear safety lens to understand and improve work-as-done (WAD). In the process, Bryant said information flows freely from the leadership team to supervisors to frontline workers and back. “The five principles of Human and Organisational Performance (HOP) form part of our foundation for leaders in Mitchell Services and Deepcore Drilling,” he said. “Is this easy to implement? We only have a small team with limited resources, so we believe we are working on the things that matter and the things that will make a difference.”

Operationalising WHS strategy on the frontline

Bryant recalls a comment from Greg Smith (a partner at Jackson MacDonald Lawyers), who recently stated at an industry conference: “Organisations use safety metrics that do not actually measure safety, but rather the volume of safety-related activities. Many businesses prioritise ticking boxes for legal compliance rather than focusing on the actual effectiveness of safety measures. This compliance-driven approach can result in safety processes that are superficial and do not genuinely protect workers.”

With this in mind, Bryant said a full review of Mitchell Services’ integrated management system was conducted with the leadership team to determine its continuing suitability, adequacy, and effectiveness, rather than chasing statistics and activity. “This has improved our understanding of the system’s use by operations in controlling our risks, and where the system needs to improve,” he said.

Learning is also vital in the business, given the spread of its operations and the variation in teams and working environments, Bryant said. “We have changed our field leadership or ‘time in field’ activities to incorporate the 4Ds into our workplace insights: what does not make sense, what is difficult, what is different, and what is dangerous. We have found that the use of the 4Ds is a quick way to build rapport between frontline workers and leaders, and it’s revealed many of those ‘weak signals’ in our business where people are having to adapt, where we do not have standardisation, or there are opportunities to learn and improve where we can,” he said.

“When the 4Ds uncover systemic issues, we can then conduct a learning team and

involve more of the business. This has led to changes in supply chains, stock availability, rig design, equipment design, onboarding, and process changes.”

“We are finding that we have transitioned to more operational improvement and being a conduit for information flow between groups”

Although the HOP principles are designed to be used together, Bryant said a standout element is the principle of ‘leader’s response matters’. This has changed the way that information is collected when there is an event, with subtle but important changes such as changing the ‘event statement’ form to an ‘event debrief’ form,

and incorporating some of Investigations Differently’s event insight questions like ‘What surprised you?’, ‘What has to go well?’, and ‘What does management need to know about this task?’ “Our event learning communication contains information about what happened versus what we thought would happen, what surprised us, what worked well, and what we learned. This has led to workers being more open and has increased the flow of information across the business,” said Bryant, who explained that this kind of approach has also lifted the engagement of the business’ WHS team. “The WHS team enjoys their role. They aren’t stuck looking at whether first aid kits are in date and walking around auditing – they are engaged and feel that they are adding value and making a difference,” he said.

Leadership and integrating safety into organisational culture

In discussing the importance of leadership to OHS, Bryant cited a quote from Todd Conklin: “As leaders, the first thing that we need to do is to change our definition of ‘safety’. Safety is not the absence

of accidents. Safety is the presence of controls and the capacity for our people to adapt and to fail safely.”

Bryant said Mitchell Services has taken a proactive approach to shifting the focus of its leadership team. As a contracting business, many of its tenders still require the submission of measures such as the TRIFR (Total Recordable Injury Frequency Rate) and number of hazards reported in the past 12 months. However, Bryant said these numbers are not communicated internally “as it is not what matters most”. “We want leaders to have heightened awareness of risk and if our systems are working, the effectiveness of our controls, and also for them to be interested in work and how our people adapt,” he said.

Bryant explained that leaders can make an “enormous difference” simply by changing how they respond to failure, and that has led to an improvement in trust and openness with supervisors and the frontline. “We created our own Human and Organisational Performance (HOP) training program that uses our context and our examples, and therefore it has a lot more meaning to our leadership team and

supervisors,” he said.

“It is also how our leaders show up to a site. We have been purposeful in this - do we turn up, pull out our phone, and start doing a critical control verification? Or do we stop, and open with a 4Ds conversation by simply asking ‘Where have things been more difficult than you thought they would be?’ or asking a new starter ‘Tell me about all the dumb stuff we made you do with your onboarding, and where you suggest we can improve.’ It is not going in as the leader who thinks that they need to have all the answers; it is being a leader that is genuinely curious and interested in learning.”

Bryant and his team also work with the leadership team in transparency of information, as he said it is important to have a system that does not just count critical control verifications, but also provides detail of the failure and the observation of the control.

“And then leaders, including our Board, will do a deeper dive on any systemic failures to determine if a learning team needs to be conducted. Overall, the business has moved from purely quantitative measures to more qualitative measures. This has not been easy and has been a slow process of change,” he said.

Results, outcomes and benefits

Bryant said the first sign of success people will look for in a business is injury rates. “Ours have improved, particularly injury severity, but statistics have not been our driver,” he said. Critical risk management has improved through understanding the effectiveness of controls and, importantly, the human interface with these controls.

The 4Ds approach has also increased communication and flow of information across the business, particularly in understanding ‘weak signals’. “We are showing that it does not have to take an event for us to learn. The leadership team has maintained a close relationship with our supervisors as we are acting on the feedback and learnings we are gaining from the critical control verifications and 4D workplace insights,” he said.

“Both initiatives have resulted in changes to work design and conditions. This has made a genuine improvement to the safety of work, rather than some short-term campaign that focuses on ‘hand and finger injuries’ or ‘insert injury of the month here’. We have been genuine in making sure that our messaging is focused on critical risk and operational learning, and working closely with our leaders wanting to learn and improve. In the end we are not only a better business, but we are also a closer business. There has been one thing that has increased in this period – it is the level of trust.”

Integrating OHS into Cumberland City Council

Cumberland Council is a local government area located in the western suburbs of Sydney. Formed in 2016 from the merger of parts of the Cities of Auburn, Parramatta, and Holroyd, the council employs about 900 people and has a population of about 250,000 people.

Like many local governments, the council faces a number of significant WHS challenges.

A key element in the creation of a strong safety culture is that safety is “our number one priority” every day, according to Belinda Doig, manager audit, safety and risk for Cumberland City Council. This strategy is embedded in council’s culture, from the executive management team down through each layer of the organisation. “It is openly promoted in all staff communication, monthly WHS committee meetings, toolbox talks, and safety events,” said Doig.

The council’s WHS team works closely with the executive management team to ensure that safety is deeply embedded in the organisational culture, according to Doig. “Council’s executive team consistently emphasise that safety is our number one priority every day. By fostering a strong safety culture from the top down, we set the tone for all employees to prioritise safety in their daily activities,” she said. Every month, the council’s WHS

committee convenes to dive deep into discussions on safety culture, recent incidents, potential improvements, and strategies. “We’ve implemented a comprehensive WHS management system (compliant with ISO45001 standards) which is accessible to every member of our staff, to ensure strict adherence to safety protocols,” said Doig.

Communication, toolbox talks and risk assessments

Regular staff consultations also provide a platform to address any changes in plant equipment, work practices, or safety procedures. “We foster a proactive approach to incident prevention and improvement. Toolbox talks are a staple, offering an open forum for staff to voice safety concerns, share best practices, reflect on incidents, and propose solutions,” Doig added. Toolbox talks have a strong focus on raising safety hazards, safety improvements, and learning from incidents, near misses, and hazards. All teams across the council are required to hold a certain number of toolbox talks per month, and Doig said the agendas and frequency are monitored and reported to council’s monthly WHS committee and form part of management’s KPIs.