PROFESSIONAL

How can artificial intelligence advance the cause of OHS?

SPECIAL ISSUE CELEBRATING 75 YEARS OF THE AIHS

How can OHS professionals become more influential?

Australian Workplace Health & Safety Awards 2023 winners

AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF HEALTH & SAFETY PUBLICATION SEPTEMBER 2023 PP: 2555003/09535

In Health and Safety ALL YOUR WORKSITE SAFETY NEEDS TOTALLY SORTED! EYE, FACE & HEAD PROTECTION KNEE PADS WELDING PROTECTION FIRST AID & SUN PROTECTION WORKWEAR TRAFFIC SAFETY FALL PROTECTION PPE FIRST AID KITS FLOOR MATS RESPIRATORY PROTECTION HYDRATION HAND PROTECTION SIGNAGE & BARRIERS PADLOCKS FIRE SAFETY MATERIAL HANDLING SUN PROTECTION FOOTWEAR SAFETY CONES & BOLLARDS HAND CLEANER HEARING PROTECTION SPILL KITS Visit www.totaltools.com.au for more info For commercial sales contact Ross Kollevris 0447 674 231 2023_MetcashSponsorship_SafetyMagazine_PA.indd 1 11/08/2023 10:19:48 am

SEPTEMBER 2023 | OHS PROFESSIONAL aihs.org.au OHS Professional Published by the Australian Institute of Health & Safety (AIHS) Ltd. ACN 151 339 329 The AIHS publishes OHS Professional magazine, which is published quarterly and distributed to members of the AIHS. The AIHS is Australia’s professional body for health & safety professionals. With more than 70 years’ experience and a membership base of 4000, the AIHS aims to develop, maintain, and promote a body of knowledge that defines professional practice in OHS. Phone: (03) 8336 1995 Postal address PO Box 1376 Kensington VIC 3031 Street address 3.02, 20 Bruce Street Kensington VIC 3031 Membership enquiries email: membership@aihs.org.au Editorial Craig Donaldson email: ohsmagazine@aihs.org.au Design/Production Anthony Vandenberg email: ant@featherbricktruck. com.au Proofreader Heather Wilde Printing/Distribution SpotPress Advertising enquiries Advertising Manager Natalie Hall mobile: 0403 173 074 email: natalie@aihs.org.au For the OHS Professional magazine media kit, visit www.aihs.org.au. Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect AIHS opinion or policy. No part of this magazine may be reproduced in whole or in part without the permission of the publisher. Advertising material and inserts should not be seen as AIHS endorsement of products or services Other sections Connect with @AIHS_OHS @AustralianInstituteofHealthandSafety Australian Institute of Health and Safety How can artificial intelligence advance the cause of OHS? OHS professionals need to clearly understand what problems they are trying to solve before exploring artificial intelligence solutions 18 4 From the editor 5 Chair’s note 6 News 7 Law 8 Partnerships 34 Book review contents 24 26 Celebrating 75 years of advancing the OHS cause: 2023 marks the 75th anniversary of the Australian Institute of Health & Safety Celebrating the Australian Workplace Health & Safety Awards 2023: Excellence and innovation in WHS were recently celebrated at the Australian Workplace Health & Safety Awards 2023

can OHS professionals become more influential? New research examines the factors that impact the ability of OHS professionals to be strategically influential A primer on chemical hazard safety in the workplace: Managing chemical hazards is an important yet challenging role for OHS professionals 30 Features 10 SEPTEMBER 2023 SPECIAL ISSUE CELEBRATING 75 YEARS OF THE AIHS

How

Recognising and celebrating major milestones

There have been a number of significant developments in the broader profession and within the AIHS as it celebrates its 75th anniversary, writes

Craig Donaldson

the humans in the organisation work and will interact and use the technology.” For the full story please turn to page 18.

Technology has played a significant role in transforming organisations over the past decade. While many have been undertaking strategies to streamline operations and achieve efficiencies through digital transformation programs, artificial intelligence has shot to prominence in the past year.

With the potential to improve workplace safety, enhance risk management, and analyse data, AI technology holds immense promise. By analysing vast amounts of data and patterns, these systems can accurately predict potential hazards and identify areas requiring attention. However, there is certainly no one-size-fits-all approach (or platform) when it comes to applying AI to WHS. As Rod Maule, general manager of safety and wellbeing at Australia Post, notes in our cover story, “there is lots of new tech, and it is really interesting and potentially helpful; however, it is about thinking through ‘is this shiny thing something that addresses our risk, or something exciting and new?’” he asks. “If it addresses your risk, you really need to think through how

The AIHS also announced the winners of the 2023 OHS Education Awards as part of the Dr Eric Wigglesworth AM Memorial Lecture in May earlier this year.

Dr Cassie Madigan, senior lecturer in the School of the Environment at The University of Queensland, won the 2023 Dr Eric Wigglesworth Research Award, for PhD research which examines how OHS professionals can be strategically influential and contribute to the prevention of work-related injury and illness. “Having worked as an OHS professional for several decades, I believe influence is 99 per cent of the role,” said Madigan, who explained that if an OHS professional is unable to influence OHS decision-makers, their impact on safety outcomes will be negligible. Based on her research outcomes, Madigan recommends OHS professionals reflect on their influence behaviours and be self-aware of their current influencing practices and ask themselves five questions to assist in the process. See the full story on page 30.

The OHS Professional editorial board 2023

National safety, property & environment manager, Ramsay Health Care

In this issue’s OHS Body of Knowledge article (page 26), we explore a number of new chapters on managing chemical hazards in the workplace. The four new chapters (Managing Chemical Hazards, Health Effects of Hazardous Chemicals, Dusts, Fumes and Fibres, and Process Hazards (Chemical)), are interlinked in a number of ways, with important points of crossreference to other chapters in the OHS Body of Knowledge. As professor Mike Capra, co-author of chapter 17.2 notes: “to fully understand basic toxicology, the generalist OHS professional needs an appreciation of basic science (chapter 14), which provides an overview of how aspects of physical and biological/health sciences underpin OHS practice.”

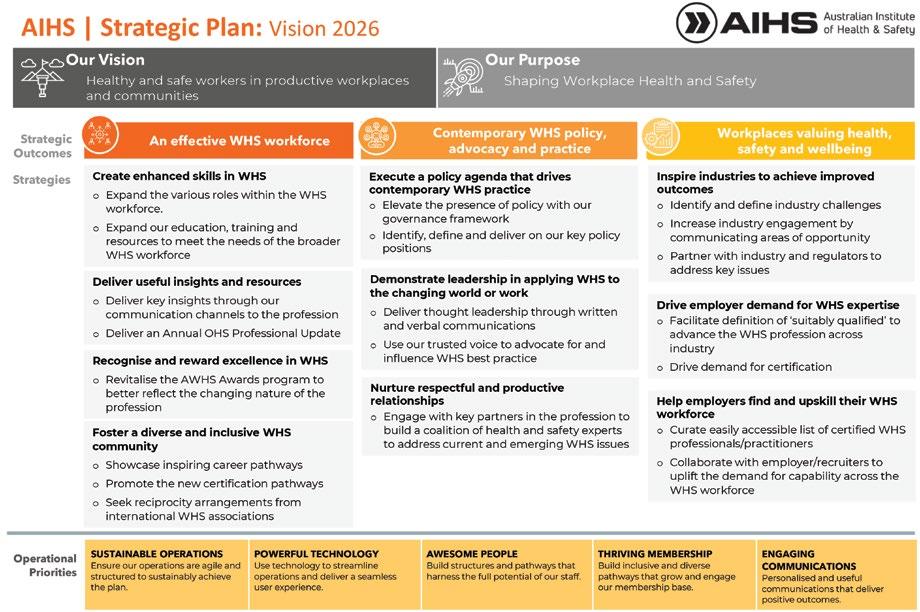

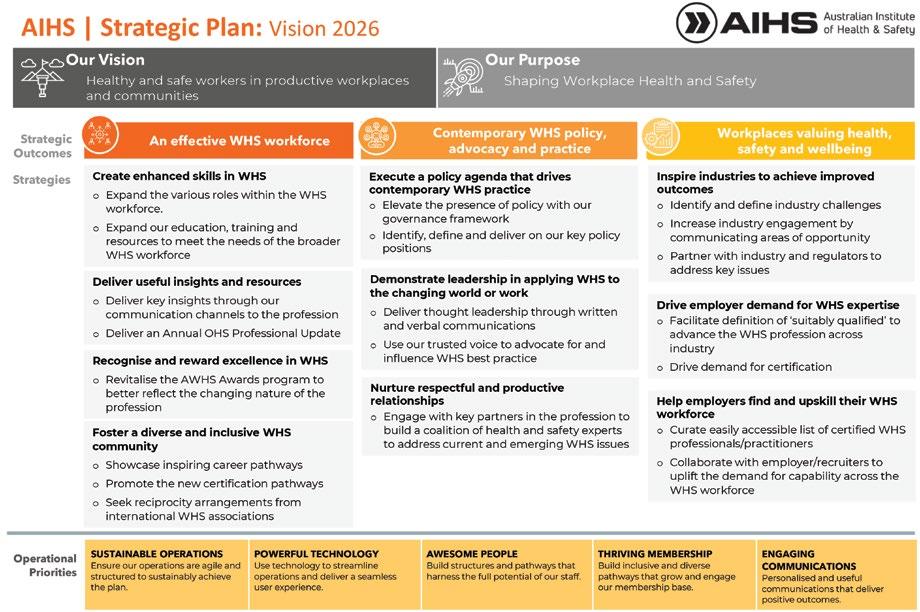

Lastly, 2023 marks the 75th anniversary of the AIHS. In a special feature (beginning page 10), we look at the evolution of the Institute from its inception in 1948, and explore a number of significant milestones in the evolution of the Institute over the decades. From the Safety Engineering Society of Australia, through to the Safety Institute of Australia and today’s Australian Institute of Health & Safety, the most recent development has been the development of the AIHS’ new strategic plan, ‘Vision 2026’. As Julia Whitford. CEO of the AIHS, notes in the article, a key component of this strategy is looking at ways to ensure an effective WHS workforce. “As we continue this exciting journey towards a dynamic, well-supported, and growing AIHS, I encourage you all to stay engaged, share your knowledge, and continue this strong collaboration,” she says. “I’m excited and energised for the future of the Institute as we embrace change and growth and continue the AIHS’s strong tradition of service to the profession.”n

Managing partner, Clyde & Co Australia

ROD MAULE, GM Safety & Wellbeing, Safety, Australia Post

ROD MAULE, GM Safety & Wellbeing, Safety, Australia Post

STEVE BELL Managing Partner –Employment, Industrial Relations and Safety (Australia, Asia)

STEVE BELL Managing Partner –Employment, Industrial Relations and Safety (Australia, Asia)

OHS PROFESSIONAL | SEPTEMBER 2023 aihs.org.au

04 EDITORIAL NOTE

Craig Donaldson, editor, OHS Professional

“If it addresses your risk, you really need to think through how the humans in the organisation work and will interact and use the technology”

CHANELLE MCENALLAY

KAREN WOLFE

KYM BANCROFT

LIAM O'CONNOR HSET group

SRG Global LOUISE HOWARD

MICHAEL

General manager of high reliability, ANSTO

Managing Director, New View Safety

manager,

Director, Louise Howard Advisory

TOOMA

Looking back and looking forward

Naomi Kemp reflects on the achievements, both past and present, of the AIHS, and looks forward to the future of the profession

who advocated for being part of a professional body. Undertaking an AOHSEAB accredited course, I relied on the OHS Body of Knowledge for foundational knowledge. A few years later, I became a Certified OHS Professional Member during the implementation of Certification.

Having industry and academic leaders, influencers, advocates, course accreditation, the OHS Body of Knowledge and Certification are all things taken for granted as ‘what the AIHS does.’ It is unfortunate that those on the outside don’t understand and appreciate the value of these things. I most certainly do.

will be enhanced by this too. These outcomes are operational priorities key for achieving the Vision 26 Strategic Plan set by the Board.

Vision 26 seeks to achieve strategic outcomes – an effective WHS workforce; contemporary WHS policy, advocacy and practice; and workplaces valuing health, safety, and wellbeing. All of which requires us to recognise that the world of work is changing rapidly due to technological, social, environmental and economic factors, and that health and safety professionals need to adapt and innovate to keep pace with these changes.

In this edition of the OHS Professional, the AIHS is not only looking back at its past achievements over 75 years, but also looking forward to the future challenges and opportunities for the profession. Reaching a milestone of 75 years, does make one reflect on what has changed even in the relatively short amount of time I have been a member. Even more so as I reach the end of my six-year tenure on the AIHS Board.

So, I want to indulge for a moment to recognise what I have had the opportunity to experience and perhaps influence in my time. I joined the AIHS as a student member during my studies under Mike Capra, Margaret Cook, and Kelly Johnstone

Corporate Members

SHARING OUR VISION – DIAMOND MEMBERS

Amazon Commercial Services Pty Ltd

APA Group

Avetta

Enablon Australia Pty Ltd

Everyday Massive Pty Ltd

Programmed

SAI360

Zenergy Safety Health & Wellbeing

GETTING CONNECTED – SILVER MEMBERS

Aurecon Australasia Pty Ltd

Australian Bureau of Statistics

Australian Unity

Brisbane Catholic Education

Clough Projects Australia Pty. Ltd

Codesafe

Compita Consulting Pty Ltd

Convergint

Downer EDI LTD

Engentus Pty Ltd

Fifo Focus

Guardian Angel Safety

Herbert Smith Freehills

Now at 75 years old, under the AIHS brand and with the highest membership ever, we look to what is next. With Julia leading the national office with vim and vigour, we are going to see the member experience enhanced through much needed digital innovation. I anticipate our staff experience

One of the most significant drivers of change in the way we work is the coming of age of artificial intelligence (AI). We have already started to see how it has the potential to transform the way work is done, as well as the risks and benefits associated with it. Some of this will be discussed in the following articles, and no doubt in our Branches, networking events, webinars, and symposiums around the country.

In a world where AI is becoming increasingly prevalent, I think it will be exciting to see how our roles change and adapt to ensure we continue to shape health and safety in Australia. I look forward to the challenge. Now, where are my shades? n

INVESTING IN HEALTH & SAFETY – GOLD MEMBERS

Alcolizer Technology

Area9 Lyceum

Australian Army

BGIS Pty Ltd

Brisbane City Council

Coles Group

Defence Housing Australia

EY

Federation University

Jones Lang La Salle (NSW) Pty Ltd

K & L Gates

Kitney OHS

Metcash Limited

MinterEllison

Relevant Drug Testing Solutions

Teamcare Insurance Brokers Pty Ltd

Uniting

BEING PART OF THE NETWORK – BRONZE MEMBERS

Hitachi Rail STS Pty Ltd

HOK Talent Solutions

Pilz Australia

Port of Newcastle Operations Pty Ltd

Safesearch Pty Ltd

Sustainable Future Solutions

The Safe Step

Trainwest Safety Institute

Transurban UnitingSA

University of Queensland

Virgin Australia

5 Sticks Consulting

Airbus Australia Pacific

AusGroup Limited

BWC Safety

Complete Security Protection Pty Ltd

Ecoportal

Employment Innovations Pty Ltd

Employsure Pty Ltd

FEFO Consulting

Flick Anticimex Pty Ltd

Health & Safety Advisory Service P/L

Integrated Trolley Management Pty Ltd

Isaac Regional Council

Kemira Australia Pty Ltd

Liberty Industrial Modus Projects

National Storage

National Training Masters

Office for the Commissioner of Public Sector Employment

Safetysure

SafeWork SA

Scenic Rim Regional Council

Services Australia

SIXP Consulting Pty Ltd

Westside Christian College

Would you like to become a Corporate Member of the AIHS? Please contact AIHS on 03 8336 1995 to discuss the many options available.

SEPTEMBER 2023 | OHS PROFESSIONAL aihs.org.au 5 05 CHAIR’S NOTE

“Now at 75 years old, under the AIHS brand and with the highest membership ever, we look to what is next”

Naomi Kemp, Chair of the Australian Institute of Health & Safety

Enforceable undertaking for Queensland Museum Board over Q Fever cases

The Board of the Queensland Museum recently entered an enforceable undertaking (EU) worth at least $900,224 following an incident in which two employees at the museum were diagnosed with Q fever. Part of the work and research of the Queensland Museum Network includes taxidermy of animals for display or study. It is alleged that between 1 June 2015 and 22 February 2019, workers were exposed to the risk of serious injury or illness from work that was performed in the evisceration area of the Queensland Museum in South Bank to prepare exhibits for display. In January 2019 and February 2019 two employees, based at the Queensland Museum were diagnosed with Q fever. One employee was diagnosed with a spinal abscess as a result of contracting Q Fever while the other employee experienced flu-like symptoms. While the source and cause of Q Fever have not been identified, however, the EU said taxidermy of native animals and field work associated with collecting specimens are potential causes.

SA introduces laws to criminalise industrial manslaughter

The South Australian Government recently introduced a Bill to make industrial manslaughter a criminal offence in the state. Under the Work Health and Safety (Industrial Manslaughter) Amendment Bill, individuals can face a maximum penalty of 20 years imprisonment, and $18 million for companies, if they are reckless or grossly negligent in conduct that breaches a work health and safety duty and results in the death of another person. The introduction of this bill brings South Australia into line with other jurisdictions which have made industrial manslaughter a crime, including Queensland, Victoria, Western Australia, and the ACT. “Industrial manslaughter laws recognise that, while tragic workplace incidents do occur from time to time, it’s not an accident when people deliberately cut corners and place workers’ lives at risk. It’s a crime and it will be treated like one,” said South Australian AttorneyGeneral, Kyam Maher. “The overwhelming majority of businesses in South Australia do the right thing and take the health and safety of their workers seriously.”

Pressure and stress drive suicide rates up in construction industry

Long work hours and job insecurity are driving suicidal thoughts and distress among some Australian construction workers, according to new research from the University of South Australia. It found that the strain of working in a sector that, by nature, is often transient, requires hard physical labour, and assumes self-reliance and risk-taking attitudes, is pushing some workers to unendurable distress. These factors are contributing to the 190 cases of suicide within the Australian construction industry every year, equating to one worker taking their life every second day. The University of South Australia study, in collaboration with mental health charity MATES in Construction (MATES), explored the drivers and experiences of suicidal thoughts and psychological distress of industry workers. The research team also reviewed coping strategies that workers have adopted during challenging times, as well as what the industry can do to lower the risk of losing more of its workers.

Transport gig workers feel pressured to cut safety corners

More than half of food delivery, rideshare, and Amazon Flex drivers experience workrelated stress, anxiety, and mental health issues, according to a recent research report. It found 56 per cent of food delivery riders are pressured to rush and take risks on the road to earn enough money and avoid deactivation for being deemed too slow by the algorithm. This compared with 51 per cent of all gig workers, who said they also felt pressured to rush or take risks to make enough money or protect their job. The report, which was conducted by The McKell Institute and commissioned by TEACHO (Transport, Education, Audit, Compliance, & Health Organisation) and the TWU, also found one in seven workers had experienced sexual harassment, while over a third have been physically injured while working. While women only made up one in ten survey respondents, they experienced over twice the rate of sexual harassment as men – at 26 per cent compared to 12 per cent.

Alarming rise in compensation claims for apprentices and trainees

In the five years to 2021, the number of serious workers’ compensation claims (involving total absence from work of one week or more) for apprentices and trainees rose by 41 per cent to 11,490 claims, despite the number of apprentices and trainees increasing only 13 per cent. A new analysis from Safe Work Australia also found that the construction, manufacturing, and other services industries accounted for more than two-thirds of all serious workers’ compensation claims (those that result in five or more days lost from work) for apprentices and trainees. Half of these claims were for workers in the construction industry alone. Furthermore, for apprentices and trainees under 30 in the construction industry, the most common type of workrelated injury was lacerations or open wounds not involving traumatic amputation. while the most common cause of work-related injury was falls, trips and slips. And for apprentices and trainees under 30 in the manufacturing industry, the most common type of workrelated injury was lacerations or open wounds not involving traumatic amputation.

Assaults on retail workers to attract stronger penalties

People who assault retail workers will face tougher penalties under a Bill which was recently tabled by the NSW Government. The Crimes Legislation Amendment (Assaults on Retail Workers) Bill 2023 will introduce three new offences into the Crimes Act 1900. The reforms make it an offence to: assault, throw a missile at, stalk, harass or intimidate a retail worker in the course of the worker’s duty, even if no actual bodily harm is caused to the worker, with a maximum penalty of 4 years imprisonment; assault a retail worker in the course of the worker’s duty and cause actual bodily harm to the worker, with a maximum penalty of 6 years imprisonment, or; wound or cause grievous bodily harm to a retail worker in the course of the worker’s duty, being reckless as to causing actual bodily harm to the worker or another person, with a maximum penalty of 11 years imprisonment. “This type of offending causes enormous distress for the shop workers, their families and the wider community and can leave lasting emotional scars, as well as those caused by injury,” said Minister for Industrial Relations and Work Health and Safety Sophie Cotsis.

OHS PROFESSIONAL | SEPTEMBER 2023 aihs.org.au 06 AIHS NEWS

Legal advice hotline launched for AIHS members

The Australian Institute of Health and Safety has partnered with law firm K&L Gates to provide business members with an exclusive member benefit

Are you concerned about safety risks and their potential legal implications in your workplace?

The Australian Institute of Health and Safety recently launched a new legal advice hotline in conjunction with K&L Gates, experts in addressing workplace health and safety legal issues.

By using the Take 15 hotline, AIHS members can access a free 15-minute discussion with the K&L Gates national safety team about ways to control safety risks in their business, with a focus on proactive strategies for compliance and incident prevention.

In this Q&A, OHS Professional speaks with K&L Gates partners Dominic Fleeton, Alanna Fitzpatrick, and Paul Hardman about some of the latest trends, challenges, and solutions in WHS law and governance and what the Take 15 hotline offers AIHS members.

OHS Professional: How well do most organisations fare in terms of WHS legal governance?

K&L Gates: In our experience, the organisations that we advise and act for take the issue of safety in the workplace very seriously.

However, the level of effectiveness in managing and mitigating safety risk varies widely, and the variance does not necessarily reflect the organisation’s size or success. Some organisations have very robust risk management systems in place, whereas others are more superficial. Robust systems are generally anchored in a detailed assessment of the safety risks arising across each part of the organisation, investment in effective controls to mitigate critical risks, clear lines of accountability for the implementation and periodic review of risk controls, and a proactive approach to risk management.

OHS Professional: Where are the most common WHS legal gaps/ areas of risk and exposure for organisations?

K&L Gates: One of the biggest gaps we are seeing at present concerns the effective

management of psychosocial health risks, including sexual harassment and bullying. This is corroborated by the rapid increase in the number of mental health workers’ compensation claims that we have seen in the past three years.

OHS Professional: What is the Take 15 service about, and how can it help AIHS members?

K&L Gates: Take 15 is an exclusive hotline service offered through a partnership between the AIHS and K&L Gates. By calling the hotline, members can access 15 minutes of free legal advice about ways to control safety risks in their business, with an emphasis on proactive strategies for compliance and incident prevention.

OHS Professional: How can a proactive approach to WHS legal risk mitigation assist organisations and WHS professionals?

An issue with which many organisations have been grappling is the need to draw upon internal resources from disciplines in a coordinated way to assess and mitigate psychosocial risks properly. For example, there is a clear need for safety professionals to work collaboratively with Human Resources to ensure that risks are identified and measures are identified and implemented. Both groups have independent but critical skill sets.

K&L Gates: A proactive approach to WHS legal risk mitigation is a key component of future-proofing for any business. It is critical for organisations in order to limit their liability, reduce their insurance premiums and, most crucially, protect their workplace culture and brand. n

For more information, please visit www.aihs. org.au/take-15-sounding-board-service or call 1800 825 315 to speak to a member of the K&L Gates safety team.

SEPTEMBER 2023 | OHS PROFESSIONAL aihs.org.au 7 LAW 07

“Some organisations have very robust risk management systems in place, whereas others are more superficial”

Streamlining EHS performance through SaaS-enabled platforms

SaaS-enabled and mobile-ready applications can play an important role in protecting workers against risks and hazards, complying with regulations, conducting audits and inspections, and managing incidents

Investors, consumers, analysts, employees, and other key stakeholders have long looked at financial metrics as key indicators of a business’s operational health. Now, those same stakeholders are demanding companies make – and keep – strategic commitments to advance social responsibility and environmental stewardship. That’s because investors and analysts increasingly report strong correlations among ESG performance, business value, and operational performance.

Today’s businesses are expected and often required to report and comply with a myriad of inconsistent and ever-evolving ESG regulations. They’re also faced with the overwhelming task of centralising and standardising non-financial ESG data from a multitude of internal and third-party sources.

“Just like financial reporting, effective ESG reporting requires multiple corporate regions, functions, and businesses to rise above their siloes to work together to collect and report ESG data, analyse that data to identify and manage risks, and assure its accuracy,” said Jay Mahoney, regional director, APAC at Wolters Kluwer Enablon. “That kind of true collaboration and integration can only happen with the support of digital transformation: technologies that can break down siloes, bring clarity to complexity, and ensure the traceability and auditability of ESG data.”

Three EHS and organisational trends

There are a number of significant EHS trends playing out within organisations, according to Mahoney. First, he observed innovative and emerging technologies are becoming more present in EHS management. “Examples include artificial intelligence, machine learning, digital twins, mobile technologies, etc. These technologies are not meant to replace EHS staff, but rather to make EHS processes more efficient,” he said. Second, the EHS function plays a big

role in the ESG programs of organisations. “This is not an accident,” said Mahoney, who explained that for decades, EHS departments have been collecting and managing key metrics, including carbon emissions, waste, and workplace incident rates, among others. “In fact, almost all of the ‘E’ of ESG and part of the ‘S’ is just EHS with a new name. We see today the EHS function owning outright the company’s ESG strategy, or having a big influence over it, or at least being a major contributor to it,” he said.

The third trend is one where the traditional pain points and concerns of EHS teams remain high on their agenda. “Of course, the use of emerging technologies, consolidation of EHS IT systems, and ESG are big trends, but ultimately, compliance with environmental and occupational health and safety regulations and the need to reduce incident and accident rates still reign supreme in terms of top EHS objectives,” he said.

Benchmarking EHS platform performance

In terms of how organisations use technology platforms to drive EHS outcomes, improve compliance, and reduce risks, the “picture is mixed”, according to Mahoney. On the positive side, he said most organisations recognise that commercial software (as opposed to spreadsheets or homegrown systems) is the best solution to achieve EHS objectives, remain compliant, and reduce risks. Leading firms also understand the value of an integrated enterprise EHS platform that covers most EHS processes or areas (e.g., incident management, audits, inspections, air emissions, environmental management, safety, occupational health, etc.), he said. “This is why many organisations have embarked on system rationalisation efforts to replace multiple EHS systems with a single one. Sometimes these efforts are part of corporate digital transformation initiatives and therefore get funded.

“But there is an untapped opportunity to “connect the dots.” Even if organisations are implementing a single integrated EHS platform, they need to capitalise on synergies between different processes,” said Mahoney, who gave a few examples of how to best leverage value from such systems. First, if an incident happens, the organisation should link it to the pertinent risk assessment and see if the likelihood or severity of an incident was properly evaluated and if the right controls were implemented. “They should also link the incident type to the pertinent inspection questionnaire to see if questions should be added to reduce the risk of a similar incident,” he said.

Second, if an audit or inspection identifies a non-conformity, new hazard, or weakened control, Mahoney said an action plan should be launched immediately to address the issue. And third, when a new hazard is identified through an observation entered by a worker, a risk assessment should be initiated, followed by an action plan to implement controls. “A single EHS platform enables these scenarios and others, or at least brings greater automation,” he said.

Common challenges and issues

When it comes to common problems that organisations experience with EHS technology platforms, Mahoney said there are some issues worth highlighting. “First, as part of their EHS system consolidation

OHS PROFESSIONAL | SEPTEMBER 2023 aihs.org.au 08 PARTNERSHIPS

“As part of your system rationalisation initiative, you must do a proper inventory of all systems that need to be replaced”

and standardisation efforts, some firms fail to do a proper inventory of all the systems used for various EHS processes,” he said. For example, an oil and gas firm may have acquired another firm that years ago acquired a refinery that previously purchased a system to track incidents. Many such sites utilise these point solutions, and Mahoney said the number can be quite high for large global firms that have been through many mergers and acquisitions. “As part of your system rationalisation initiative, you must do a proper inventory of all systems that need to be replaced,” he said.

Second, while most organisations have a good understanding of the value of an integrated enterprise EHS platform, he said some are still failing to look beyond their immediate needs and setting themselves up for more problems in the future. For example, they might seek a solution only for incident management, industrial hygiene, or audits and inspections – failing to realise the value of the synergies described in the previous section. “Firms should consider both their current and future needs and understand the benefits of a single platform for all EHS processes, such as reduced training and onboarding costs, better user adoption, a single vendor to interact with, and the ability to connect the dots between different processes,” he said.

Finally, firms should think seriously about systems integration, according to Mahoney, who explained that an EHS platform would require data integrations with external systems, such as ERPs, IoT sensors, HR systems, etc. “This is especially relevant to ESG, where EHS software will have to integrate with

financial or corporate performance systems for the creation of combined financial and ESG (non-financial) reports,” he said.

Building a business case for EHS platforms

In building the business case for an EHS platform, Mahoney said it’s important to know that there may be non-EHS leaders who will be part of the decisionmaking process and who could be more difficult to convince than EHS executives or leaders. “Therefore, you have to go beyond the ‘traditional’ arguments consisting of protecting the safety and health of employees and the public, protecting the environment, ensuring compliance, etc. These arguments, centred around ‘doing the right thing’, must still be made, but you must also articulate the business rationale for EHS software,” he said.

“For example, highlight the fact that EHS software makes it easier to identify and mitigate safety risks, which reduces incidents, thus increasing productivity and avoiding operational disruptions or production delays that can result in higher costs or loss of revenue. In essence, EHS software brings efficiency gains and greatly contributes to consistency and stability in business operations.

“You can also make an IT argument: An EHS platform like Enablon is deployed throughout the enterprise, across all sites and regions. In the process, dozens of point solutions, some of them used only locally, are replaced. IT costs are therefore reduced because there is only one system to administer and maintain, and only one vendor to interact with.”

Realising optimal value from EHS platforms

For organisations and WHS professionals looking to get the most value from such platforms, Mahoney recommended using out-of-the-box products and limiting customisations as much as possible. He explained that the Enablon platform already reflects industry best practices as a result of having been deployed and used by companies worldwide for well over two decades.

“By using the standard product, you reap the most benefits from the platform and ensure upgrades are seamless, especially regarding integrations with external systems, which are more likely to be impacted if you have heavy customisations across your IT landscape,” he said.

Second, it is important to ‘connect the dots’ and take advantage of the synergies described in the second section above. “That’s where the true value is found because it enables a cycle of continuous improvement. For example, if an accident happens, you don’t just enter it in the system for reporting and recordkeeping purposes. You also update the pertinent risk assessment, or start a new one, and launch action plans to correct what went wrong and prevent reoccurrence,” he said.

“Also, if you use the Enablon Permitto-Work application, you can receive learnings from past incidents associated to the work to be done directly in the digital permit right before you start work, to ensure you’re fully prepared and safe. Make full use of these synergies.”

Finally, Mahoney said to remember that, ultimately, an EHS platform is meant to strengthen your existing processes, not replace them. “Make sure your processes for incident management, incident investigation, action plans, audits and inspections, risk assessments, environmental reporting, etc., are well defined in your organisation. The Enablon platform helps you make your processes more efficient and effective through configurable workflows, dashboards, data quality checks, notifications, automations, real-time alerts, etc. Enablon helps you get from ‘point A’ to ‘point B’ in a faster and better way. But you have to determine where your ‘point B’ is located.” n

Enablon offers a suite of SaaS-enabled and mobile-ready environment, health, safety, and quality (EHSQ) applications designed to protect workers against risks and hazards, comply with regulations, conduct audits and inspections, and manage incidents. Wolters Kluwer is a diamond member of the AIHS.

SEPTEMBER 2023 | OHS PROFESSIONAL aihs.org.au 9 09

Celebrating 75 years of

2023 marks the 75th anniversary of the Australian Institute of Health & Safety, with a number of significant milestones in the evolution of the Institute over the decades

The AIHS started as the Safety Engineering Society of Australia, whose seed was planted in 1948 when a small group of students attended the first Industrial Safety and Accident Prevention course at the then Melbourne Technical College (which later became RMIT University). There was a meeting of like minds at this course, which provided a fortuitous opportunity for many of the founding members of the organisation to come together.

Neville Betts FAIHS, Former Chair, College of Fellows, and winner of the Harold Greenwood Thomas Award (2005), explains that their vision was to create a profession that could influence workplaces through the prevention of accidents, injuries, and diseases.

These individuals included:

• Eric Warburton (first president)

• Chris Allan (first secretary)

• Eugene Falk (served periods as secretary of the society)

• Harold Greenwood-Thomas

• Bill Reid, safety manager for the then Herald newspaper

• Bill Jenkins, safety manager for the Gas & Light Company

• Peter Cathcart

• Bill Carroll

• Cecil Holmes (president-elect 1963)

After completing the course, Betts said this group kept together and formed the nucleus of the Safety Engineering Society of Australia. Their regular monthly meetings were held in the Boardroom of the Melbourne-based insurance company, Manchester Unity. Chris Allan,

an inaugural member of the society, later established ‘Alston Safety Equipment’, an organisation that was to become the safety equipment company Alsafe Safety. Another member who joined the society and later the institute was Bill Hughes, who Betts said was the driving force behind establishing the institute’s original safety journal, Safety in Australia. Many members found that they needed to assume several roles in these early days. For example, John Burns joined the Safety Engineering Society in 1957. He became a Fellow of the Safety Institute of Australia in 1984 after serving as Chairman of the Monash Exhibition Committee, a member of the Federal Constitution Committee. Membership of the Society expanded steadily and reached the stage where every state had formed a division affiliated with the federal body. In general, Betts said membership included a majority of safety engineers and safety officers, as well as medical practitioners, insurance officers, occupational nurses, educators, and many other people interested in promoting health, safety, and accident prevention.

The Safety Institute of Australia

With time, Betts said it became apparent that the term Safety Engineering in the Society’s name had an implied bias and emphasised only one of the many disciplines associated with the effective control of accidents, injuries, and diseases. “This was a time for the society to evolve into a bigger and broader organisation (accompanied by a name change) in the form of the Safety Institute of Australia,

incorporated in 1977,” recalls Betts. Some of the notable members who carried forward the aims and objectives of the Society were Eric Wigglesworth, Samuel Barclay, Sol Freedman, Frank Kuffer, Roger Smith, Cip Corva, Hilton Ludekens, and Fred Catlin. The constitution for the Safety Institute of Australia carried forward many of the structural and professional concepts of the Society. At the time of incorporation, Betts said the Institute adopted the following aims and objectives:

1. To promote and advance the science and practice of accident prevention in all its branches and to facilitate the exchange of information and ideas in relation thereto.

2. To encourage the development of safety as a profession by promoting such activities and providing such services to members as may set at a high level their proficiency in and knowledge of safety.

3. To encourage the increased employment of proficient safety practitioners and take action to encourage recognition of the Institute as a reference authority on technical aspects of safety.

4. To cooperate and maintain a close relationship with other organisations actively interested in accident prevention and promotion of environmental health and welfare.

5. To promote and advance the above by means of forums, lectures, classes, publications, demonstrations, investigations, and recommendations or by any other means.

OHS PROFESSIONAL | SEPTEMBER 2023 aihs.org.au 10 AIHS 75TH ANNIVERSARY

2008-09 Victorian Committee

SPECIAL ISSUE

Geoff Dell and Pam Pryor, Investiture 2005

advancing the OHS cause

Standards, events, and policies and procedures

From 1958 through to the present day, Betts said the Institute has maintained a close working relationship with the Standards Australia organisation. The Institute has served on many technical committees dealing with the likes of risk management, fire safety, OHS, road and traffic design, and the Building Code of Australia. “Institute members have been appointed to Standards Australia committees while attending conferences and working parties with the International Standards Organisation in Geneva, Switzerland and the European Standards Organisation, Brussels, Belgium,” Betts added.

The Institute developed and ran an International Safety Exposition in Melbourne from 25–28 February 1998. Whereas the usual scientific conference would be strictly focused on one professional speciality, ‘Safety in Action’ brought together safety researchers and professionals from many different areas and applications, according to Betts, who explained that, instead of concentrating on the normal narrow or niche of specialists, Safety in Action sought to encourage participants to explore the application of safety in all of its applications.

In May 1986, the then Federal Council received the report of a Procedures and Practices Review conducted by a recognised management consultant, Elmar Toime. This review recommended widespread changes to the administrative and publishing policies of the Institute. The review resulted in a sharp refocusing of the Federal Council’s attention on all matters of Institute management and has directly led to the adoption of formal

strategic planning measures of which the consultative document became a forerunner, according to Betts.

The many recommendations made in the report by Elmar Toime resulted in some immediate improvements, but more importantly, the production of the Safety Institute of Australia Corporate Plan, 1989-1992. The Institute’s Corporate Plan was both a consultative document and a plan of action for both Federal and Divisional organisations, said Betts. Drafted by the then Federal President Gary Knobel, the Corporate Plan was based upon decisions taken at the Federal Council over the period 1985-1988. Many points within the plan were actioned, and Betts said this document served as a major vehicle for change and the modernisation of the Institute.

The SIA evolves and expands David Skegg FAIHS was the former SIA National President and Chair of the College of Fellows. “Witnessing and being part of the development of the Institute has been a learning and rewarding experience, from the early days of 1992 through to my stepping away from all positional responsibilities,” he recalled.

“The year 1999 saw then President Geoff Dell and myself careering around Australia to re-establish relationships with members at large and the Divisional structures. This followed an intense period, driven by the passion and energy of Geoff Dell, where I was privileged to organise the first investiture of Fellows by the then Governor-General, Sir Peter Hollingworth.” That same year saw the first steps to changing the SIA’s constitution, representing the Institute at the American Society of Safety Engineers (ASSE) conference in Nashville,

establishing a privacy policy and ethics process, and many others. A tipping point was reached following the Health and Safety Professionals Alliance (HASPA) with the Victorian Workcover Authority, which led to inviting the Presidents of the UK (John Lacey), ASSE (Mark Hansen), Canadian (John Boerefyn), Malaysia (Lee Ham), and China (Cheng Ying-Xue) to the Safety in Action conference in Melbourne – “the beginning of our involvement in the fledgling INSHPO, now to be chaired by our own Nathan Winter”, said Skegg.

“That same year saw the creation of the Congress of Occupational Safety and Health Association Presidents (COSHAP) led by our own Dino Pisaniello, who developed its profile in the ensuing twelve months.”

Internally, Skegg said the Institute developed from a secretariat in the garage of a member in Lindisfarne, Tasmania, through contracted services to a professional support secretariat based in Melbourne supplied by stalwart Neville Betts and Doreen, “his long-suffering, hard-working wife”. This allowed the then Federal Committee to look longer term, with proposals such as computerisation, financial structures, and membership grades and awards, including the creation of the Harold Greenwood Thomas award, all of which fostered lively debate. “A proposal to establish a subsidiary to be known as the Australian Safety Representatives Association (ASRA) to cater for the practitioners who account for most of the then 20,000 deriving their living from the world of safety was tabled in 2003, but defeated on the basis that the current majority view was that the Institute was for the professional grades. Of particular note is the OHS Body of Knowledge project, arising from the earlier

SEPTEMBER 2023 | OHS PROFESSIONAL aihs.org.au 11

SIA Safety Show NSW 2008

2009 Education Awards

HASPA, and so well guided and managed by Pam Pryor AO over many years, and of such a standard to be now recognised on an international basis. This is truly a shining light for the Institute,” said Skegg.

A generational change from the entrepreneurial spirit of the Dell and Skegg years was followed by a lull in growth, which was ably turned around by the arrival of Patrick Murphy, first as President and then as Chairman of the newly formed proprietary limited company it is now. Along the way were a number of CEOs, who Skegg said all did their best to steer the ship through the turbulent times of the day.

The Australian Institute of Health and Safety

By the late 2000s, it was evident that the evolution of OHS was well and truly underway, according to Patrick Murphy, former Chair of the SIA. “Work was changing,” he explains. “The relationship between employer and employee was changing; the legislative environment had also been embarking on its own adventure to harmonise. There had been a few significant incidents and tragedies which helped shape public perception regarding the importance of work health and safety.”

There was also the re-emergence of deadly occupational illnesses that had not been identified or monitored. Contextually speaking, however, Murphy said the biggest factor and trend was the emphasis and focus being placed on mental health and wellbeing. “The realisation that mental health was just as important as physical safety and inherently connected. Organisations were responding to and dealing with their role in one’s mental health. The trend and importance would culminate in regulators requiring us to now address psychosocial hazards and risks born out of the work,” he said.

“So, the megatrends of the 2000s

that were observed were playing out in our discipline and field. The risk for the SIA was that it was seen standing still, not moving forward, and evolving to address the needs of its members and the profession more generally. How do we evolve, grow, and modernise the engineer’s vision from 1948? We set out on redefining the strategy of the organisation, aiming to reposition it for the future.”

in 2019 also aimed to reposition the profession and practice as:

• Enablers in business, not blockers: Striving for solutions to make things happen safely as opposed to finding reasons why something can’t be done.

• Reducing complexity each and every day: Procedures and paperwork do not save people’s lives. Gold-plated systems are costly and burdensome. We need to be more conscious of the differences between work as done vs work as imagined.

• We needed to cut through more and more – especially at the frontline: We need not create new and more safety initiatives every day but rather hold course and remain disciplined on the most important critical few that will change the game.

It was a three-year plan that began in 2014 and consisted of three phases:

• Phase 1: Stabilise the organisation

• Phase 2: Refresh the direction, and

• Phase 3: Reposition for the future, a transformation centred around repositioning the Institute as a modern and dynamic peak body.

“In FY19, after a wide consultative, we announced the evolution of the SIA into the AIHS, which will likely be earmarked as a significant milestone in our history. We were focused on repositioning ‘health,’ especially mental health and safety, to enhance our relevance and value for stakeholders,” said Murphy.

“We owed it to ourselves and the next generational workforce working in OHS. The future needed us to be determined in tackling new and emerging challenges in order to improve health and safety outcomes.” The transition of our Institute

• We needed to be injecting more of the “H,” especially mental health, into OHS: The state of mind one is in when one makes a decision critical to whether one lives or dies is so critical to improving safety outcomes. The connection is very real.

• We needed to be clear on the commercial value of what we are doing: In our profession, we talk too much about the what and the how and not enough about the why. We fundamentally need to understand and appreciate the business context.

• We also needed to be more open to new ideas and learning, challenging ourselves and our peers, and embracing diversity in thinking: The old way will not be the new way, necessarily.

“Our vision was for safe and healthy workers in productive workplaces and communities. It was a privilege and honour to lead the Institute during this period, and I am proud to see the Institute evolve and modernise,” said Murphy.

OHS PROFESSIONAL | SEPTEMBER 2023 aihs.org.au 12 AIHS 75TH ANNIVERSARY

Geoff Dell 2008

CoF Lunch 2010

“There had been a few significant incidents and tragedies which helped shape public perception regarding the importance of work health and safety”

Women's Breakfast 2009

The OHS Body of Knowledge and the profession

A defined body of knowledge has long been considered a core element of a profession, and the lack of such a body of knowledge was identified as a factor limiting professional development in the field of OHS, according to Pam Pryor AO FAIHS ChOHSP and former manager of the OHS Body of Knowledge.

Following the formation of the Health and Safety Professionals Alliance (HaSPA) in 2007, sponsored by WorkSafe Victoria) Pryor said the recommendation was made that those providing OHS advice should be certified with the criteria for certification, including “completion of an educational program specified by a certification board or alternate means of establishing the applicant has the required knowledge.” However, Pryor said there was no agreement at that time as to what that knowledge should be.

A HaSPA sub-committee was convened in early 2008 under the auspices of the then Safety Institute of Australia (SIA) to explore how the core body of knowledge for the OHS generalist might be conceptualised and the required content. In 2009, WorkSafe Victoria provided funding for the OHS Body of Knowledge project. HaSPA ‘owned’ the project and provided oversight with technical aspects developed and managed by a technical panel comprising representatives of La Trobe University, (then) Ballarat University, RMIT University, and the SIA, with a consultant undertaking project administration and some consultation activities. As HaSPA was not a legal entity, Pryor explained that the Safety Institute of Australia was the contract holder and responsible for financial governance.

The design of the OHS Body of Knowledge was guided by a clear definition of its intended users, its application, and a set of principles.

The intended users of the OHS Body of Knowledge were defined as generalist OHS professionals, and the OHS Body of Knowledge would:

• Inform OHS education, but not prescribe a curriculum

• Provide a basis for course accreditation and professional certification

• Inform continuing professional development

• Be able to be applied in different contexts and frameworks.

“There would be a broad range of inputs, including Australian and international sources, educators and academics, OHS professionals, OHS professional bodies, and other interested parties,” said Pryor. “It would not be based on the opinions of individuals but, wherever possible, be derived from the evidence base reported in peer-reviewed literature and, as the evidence base expands, it would be updated to ensure its continued relevance. Information gathering and consultation resulted in a conceptual framework and list of chapters.”

The technical panel then selected highly regarded Australian experts to author each chapter topic. The OHS Body of Knowledge was launched in April 2012 with the OHS Body of Knowledge website and WorkSafe Victoria, assigning copyright and custodianship to the SIA.

In the 11 years since its initial publication, Pryor said the original chapters have been reviewed and updated with the addition of 21 new chapters. The OHS Body of Knowledge has been incorporated into the accreditation requirements of Australian universitybased generalist OHS education; it provides a framework for certification of individual OHS professionals by the Australian Institute of Health & Safety and is a resource for developing and implementing Continuing Professional

Development (CPD) plans. Internationally, it informed the development of the knowledge component of the INSHPO publication The Occupational Health and Safety Professional Capability Framework: A Global Framework for Practice.

“The OHS Body of Knowledge is a body of learning derived from research, education, and practice at a high level. It provides OHS professionals with knowledge, which is a point-in-time update of the current thinking. However, the OHS Body of Knowledge is only useful to the profession when people are aware of it and use it,” said Pryor, who added that it is freely available to all OHS professionals and others interested in evidenced-based OHS information via www.ohsbok.org.au.

The Australian OHS Education Accreditation Board (AOHSEAB)

Susanne Tepe, Registrar AOHSEAB and inaugural member of the OHS Body of Knowledge Technical Committee (2008 to 2012) recalls the moment that provided a catalyst for the eventual formation of the Australian OHS Education Accreditation Board. “Who would have thought that a taunt by a Victorian OHS regulator in 2008 would precipitate a 15-year journey to define the knowledge base of the OHS profession and recognise the Australian universities that use this knowledge to mould future OHS professionals?” Tepe recalls.

“The taunt came from a regulator at WorkSafe Victoria who observed that: ‘There is a lot of bad OHS advice being given in workplaces, and it’s your fault.’ The OHS educators and SIA members in the room were aghast. There was a great sucking in of breath, much looking at the tabletop; no one actually crawled under the table, but many were clearly considering it.”

To address this, she said there was a discussion about making OHS a profession

SEPTEMBER 2023 | OHS PROFESSIONAL aihs.org.au 13

Herbert Smith Freehills 2011

and what attributes make up a profession. Being academics, Tepe said there was literature searching, examining other professions, and many discussions. Ultimately, the decision was that the profession needs a recognised body of knowledge that defines the knowledge and skills used by the professionals, provides them with the means to acquire the knowledge and skills, members who possess and practice that knowledge and those skills, and a set of ethics that put boundaries on the practice with consequences for those who are unethical. This led to the development of the OHS Body of Knowledge, the Accreditation of OHS education programs (AOHSEAB), the Certification of members, and the AIHS Ethics Statement.

“While the development of the OHS Body of Knowledge is addressed above, suffice it to say, it was a grand adventure. Recognising the original 40 concepts that formed the core chapters of the OHS Body of Knowledge, wrangling over 100 local experts to author the chapters, and editing this into a cohesive whole for publishing in 2012 was a herculean task,” said Tepe.

The next task was to ensure that aspiring professionals were educated with respect to this OHS Body of Knowledge. This task was delegated to the Australian OHS Education Accreditation Board (AOHSEAB), structured as an independent body under the aegis of the SIA. The AOHSEAB was formed from a broad base of stakeholders, with the board members representing OHS professionals, OHS academics, related OHS professional societies, employers, unions, and regulators, with the assistance of an education advisor. “Among their first tasks was to set up an audit document (we are OHS professionals, after all) to be applied to university programs (Bachelors, Masters, or Graduate Diplomas) addressing the educational requirements of the government as well as the content,

knowledge, skills, and application expected of a graduate OHS professional,” said Tepe.

“After trials and improvements with a few willing universities (thank you RMIT and LaTrobe), the accreditation process was used by 18 universities to have five undergraduate programs and 17 postgraduate programs accredited.” After a review of the process in 2017, AOHSEAB reworked its audit document to focus more on the content of the programs (meaning less emphasis on university structures and processes) and added more attention to skills and application of knowledge. This was heavily influenced by the INSHPO Capability Framework 2017, which the SIA representatives helped develop. In 2023, while several accredited programs have been closed during these tumultuous times for universities, Tepe said there are still 15 universities with 20 active programs that are accredited as providing the core knowledge and skills for entry-level OHS professionals.

“OHS is on the cusp of being able to be a recognisable profession. There is an OHS Body of Knowledge and ways of recognising when one has achieved this body of knowledge (certification). There is a Code of Ethics. The pieces are in place; the main issue is that there needs to be a drive to achieve recognised professional status. This can only be achieved with a push from the profession and a pull from employer and regulator stakeholders. AOHSEAB is well placed to support this.”

Furthering the cause of education

The Institute has successfully promoted and supported a number of undergraduate, graduate, and postgraduate educational courses around Australia – the first of which came about in 1979. One of these was the Graduate Diploma in Occupational Hazard Management (GDipOHM), which

was a ground-breaking development in OHS, according to Professor Dennis Else, former Pro Vice-Chancellor at the University of Ballarat and former Chair of the National Occupational Health and Safety Commission, and Dr Steve Cowley, CMIOSH FAIHS and Associate Professor of Accident Forensics at Central Queensland University

“Not only was the concept of managing hazards a little alien but also OHS had not previously been considered a subject of study at a higher level in Australia,” said Else and Cowley. Led by Derek Viner, with his aeronautical engineering background, and a small group of mechanical engineers at the then Ballarat College of Advanced Education (BCAE), the GDipOHM had its first intake in 1979. Eric Wigglesworth from the Menzies Institute became a central player, and collectively, the core lecturers planted the roots of hazard and risk management in engineering and introduced a high level of academic rigour, according to Else and Cowley.

“Unforeseen had been the influence of the four, two-week teaching periods on the Ballarat campus over the two-year course. Throwing OHS practitioners together in student accommodation led to much diffusion of knowledge and ideas, cemented friendships, and in no small way influenced the development of the early Safety Institute of Australia,” Else and Cowley said.

During the early 1980s, Else was seconded from Birmingham’s Aston University to support course growth. He then made the permanent move and saw the opportunity to grow research activities around the core of the GDipOHM. Cowley joined Else in 1985 to assist with delivering the first research projects and seeking further funding. “At the heart of Victorian Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (VIOSH) research was a focus on the generation and sharing of solutions to workplace problems,” they recall. “This prevailed.”

OHS PROFESSIONAL | SEPTEMBER 2023 aihs.org.au 14 AIHS 75TH ANNIVERSARY

WA Branch Christmas Function 2016

SIA Conference 2016

The advent of the state legislation around that time and the formation of the National Health and Safety Commission presented opportunities at Ballarat, and soon, the number of staff had grown, and VIOSH (the Victorian Institute of Safety & Health) was established. A Master degree in Hazard management was introduced for GDip students with higher academic ambitions.

“BCAE became the Ballarat University College, affiliated with the University of Melbourne, and some fresh thinking led to innovation in teaching and course design,” according to Else and Cowley, who said VIOSH staff attained teaching qualifications that led to a redesign of the GDipOHM. While maintaining the core values, the course was reconstructed to provide clearer learning pathways, building knowledge, and developing critical thinking, culminating with a dissertation that was the capstone of the studies. “The approach was based on that of a seasoned traveller who, when packing a suitcase, knows what to leave out,” said Else and Cowley.

“Around the same time, the work of Earnest Boyer was introduced to VIOSH. Boyer believed that traditional university activity needed to be broadened to address new social and environmental challenges beyond the campus. He proposed a clearer integration of research, application of knowledge in the community, and teaching and integration of these. This crystallised the thinking and supported the VIOSH approach to education; students were provided with an evidence-based framework, encouraging them to challenge theory against their real-world experiences and stimulating conversations whilst walking across the campus to the accommodation blocks where debate would often continue long into the night.”

The College of Fellows

The turbulent and productive years

of 1999 to 2001 were marked by the Institute struggling to identify itself between two schools of thought, according to Skegg: “either a populous body for all comers, or a professional body requiring entry standards and ethics, with the latter being dominant at the time,” he recalls.

“Grading levels were already established, and, following the around Australia trip by the National President and National Vice-President in 1999, it became clear that there was a need for a ‘senate’ to oversee the science and other issues.” In a letter to all Fellows and above of 29 March 2001, Geoff Dell proposed the formation of a College for the Fellow grades be formed for that purpose, with a remit to:

• Conduct colloquia to discuss emerging issues in OHS

• Engage OHS bodies from overseas in debate on emerging OHS issues

• Run advisory forums for other professional groups

• Encourage development of the OHS science within the Institute and across the OHS profession in Australia by engaging SIA members at all levels, and the public in the ideological debate.

• Conduct research-based, peer-reviewed scientific seminars to encourage Australian Tertiary Research Institutes to engage in OHS research and publication, and

• Develop a peer-reviewed scientific OHS journal.

The College was first proposed as an affiliate body of the Institute, as Skegg said there was no other option under the then constitution. “An attempt to create the College as a constitutional entity was defeated in 2001 by only two votes, probably due to too many constitutional changes being made at the same time. Nevertheless, the College continued to emerge as part of the Institute and started to make itself heard,” said Skegg.

A presentation to the Productivity Commission in 2003 by Skegg (then President) encompassed much of the College ideology and formed part of the profile presented to national bodies, such as the National Occupational Health and Safety Commission (NOHSC) and the State and Territory governments. In 2012, the College executive agreed to include new terms of reference proposed by the Board of the Institute, which were:

• Professional Standards, Ethics and Education (formerly the PSEEC of the Board), including:

o Ethics inquiries and recommendations to the Board

o Grading decisions

o Grading Appeals, and

o National Technical Panel Accreditation Board matters

The inaugural head of the College was titled Dean, in keeping with the status of that title in tertiary education. The first Dean was, predictably, Dr Geoff Dell, who Skegg said provided the passion, energy, and enthusiasm to bring the emerging safety profession into being, ably assisted by such luminaries as Pam Pryor, Honorary Fellow and barrister John McDonald, Treasurer Phil Lovelock, Neville Betts, and many others. “The reach of the College started to expand, with the awarding of Honorary Fellowships to Laurie Lawrence for his work in child water safety, and Donald Hector, for his advice to the College and his work in the public company directorates,” said Skegg. “Since these formative years, the College has continued to evolve and will undoubtedly continue to do so.”

AIHS engagement with INSHPO

The International Network of Health & Safety Professional Organisations (INSHPO) was founded in 2001 by the American Society of Safety Engineers (now American Society of Safety Professionals (ASSP)), the Canadian Society of Safety Engineering (CSSE), and

SEPTEMBER 2023 | OHS PROFESSIONAL aihs.org.au 15

Safety Symposium Board Vic 2017

the Institution of Occupational Safety and Health (IOSH) in the United Kingdom, to establish an effective and mutually supportive international network to address concerns of common interest and influence policymakers on a global scale. INSHPO has expanded its membership to include 13 organisations worldwide, according to Nathan Winter, PresidentElect of INSHPO and Former Deputy Chair of SIA.

Around 2003, the Safety Institute of Australia was invited to join INSHPO. Phil Lovelock was the inaugural SIA representative to the INSHPO Board and was INSHPO President from 2011-2012. Phil continued as the SIA representative until 2015 when Winter said he was succeeded by the then SIA Chair, Patrick Murphy. Murphy was the SIA representative until 2018 when he was succeeded by Winter (then SIA Deputy Chair). He was President of INSHPO in 2020, when COVID hit, and all INSHPO meetings were held virtually for the first time since INSHPO was founded. Winter continues to be the AIHS representative to INSHPO till today and is currently the President-elect for the second time.

Another AIHS Member, Fellow and 2022 Inspector of Year, Martin Ralph, has also served on the INSHPO Board and was a member of the Executive Council and President from 2008 to 2010. Although Martin didn’t serve as the SIA representative, Murphy said he was the representative for the Industrial Foundation for Accident Prevention (IFAP), where he was Managing Director at the time.

Pam Pryor, AO, the inaugural AOHSEAB Registrar, has been heavily involved with INSHPO. Pryor led the development of INSHPO’s flagship publication, The OHS Professional Capability Framework: A Global Framework for Practice (aka The Global Capability Framework), in conjunction with Professor Andrew Hale from the UK and Dennis Hudson from the US between 2012 and 2017. The Global Capability Framework was designed to be a visionary document to raise the bar

for OHS professional practice and create some consistency in what were highly disparate OHS education curricula and certification requirements around the world. “Many universities and certifying bodies (including the AIHS) have since aligned their curriculum and certification requirement to the Global Capability Framework, and many companies have used the Global Capability Framework to create capability frameworks for their own OHS employees,” said Winter.

a research project underway on the value of the OHS profession, are reviewing the Global Capability Framework, and seeking to diversify their membership to other geographic locations around the world,” said Winter.

The evolution of OHS management systems

The OHS Body of Knowledge has a number of chapters devoted to systems, which cover off topics including OHS management systems, rules and procedures, document usability, contractor management, and OHS performance evaluation, for example. Dr Nektarios Karanikas, Associate Professor in Health, Safety & Environment at QUT (Queensland University of Technology), co-authored the chapter on OHS management systems together with Pam Pryor, and he observed that in the circles and practice of OHS, the phrase “we have systems in place” usually denotes what we formally call OHS management systems.

While the INSHPO Board was meeting in Singapore in 2017 to coincidence with the 21st World Congress on Safety and Health at Work, then SIA CEO David Clarke, Winter (then Deputy Chair), and Tony Williams from WorkCover NSW met with representatives from the International Social Security Association (ISSA) and the International Labour Organization (ILO), organisers of the World Congress, to discuss the Australian bid for the 23rd World Congress in Sydney, which Australia ultimately won.

It was also through INSHPO that the SIA and the Board of Canadian Registered Safety Professionals (BCRSP) began discussing mutual recognition of each organisation’s certification programs, said Winter. This ultimately led to the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding by the then Chair of BCRSP, Paul Andre and Patrick Murphy (then Chair of AIHS) at the SIA National Conference in Melbourne on 23 May 2018.

“Currently INSHPO, in conjunction with several of its member organisations, have

Introducing quality management systems in the 1930s inspired early versions of OHS management systems. These were followed by regional standards such as OHSAS 18001 in the United Kingdom and AS/NZS 4801:2001 in our region and culminated in the ISO 45001 adopted by Australia and New Zealand as AS/NZS ISO 45001:2018.

As the term “system” in the industry has engineering roots, apart from the notion of “useful” to justify its existence, Karanikas said it has inherited the sense of “controllable,” which is central to disciplines such as process engineering. Thus, it is unsurprising that regulatory encouragement for implementation, audits and certification accompanied the standardisation initiatives above and incentivised the introduction of rigid, strict, and invariable processes to manage OHS. “Having an audited and/or certified OHS management system promised a competitive and reputational advantage and brought some comfort to internal and external stakeholders: ‘we must be safe. We have an OHS management

OHS PROFESSIONAL | SEPTEMBER 2023 aihs.org.au 16 AIHS 75TH ANNIVERSARY

“There was a realisation that mental health was just as important as physical safety and inherently connected”

Patrick Murphy VIC Safety Symposium 2017 David Clarke VIC Safety Symposium 2017 Naomi Kemp announcing name change to AIHS 2019 National Conference in Sydney

system, after all,’” said Karanikas.

Why then, he asked, don’t scientific evidence and lived experience consistently support that OHS management systems lead to improved OHS? “Indeed, we would reasonably expect that all successfully audited and certified companies, at least, enjoy similar OHS levels (and higher than their counterparts without OHS management systems) and harvest the fruits of their resource and capital investments in OHS management systems. Regrettably, this is not the case,” said Karanikas.

The key issue here comes from the exact phrase “we have systems in place” and the misunderstanding of what an OHS management system is. To fix this and make things work, Karanikas said we must reposition ourselves and see OHS management systems for what they should be. “The humans interacting between them and with technology and the environment are the system, and the OHS management system should serve the system. Staff should be supported by the OHS management system, not serve the OHS management system. The OHS management system must be designed with and for workers; the OHS management system should not just happen to workers,” he said.

An OHS management system can be extremely valuable and helpful if it facilitates, guides, and monitors the interactions amongst humans,

technology, and the environment – with the aim of maintaining and improving OHS, or simply put, implementing controls to minimise risks, Karanikas said. “When your OHS management system processes do not regularly “talk” to each other with the purpose of minimising risks, your system is fragmented and dysfunctional. If the major concern is maintaining the risk registry updated and not how to control risks effectively and sustainably, the OHS management system is off-track. If the investigations in your OHS management system do not conclude with tangible and effective risk controls, they add no OHS value,” he said.

The AIHS, now and into the future

The AIHS recently released its new strategic plan, ‘Vision 2026’, developed by the AIHS Board of Directors. “A key component of this strategy is looking at ways to ensure an effective WHS workforce,” said Julia Whitford, CEO of the AIHS.

“To do this, the AIHS will align education pathways to career pathways and opportunities, convert research and evidence to practical tools, keep professionals up-to-date and informed, and, as always, recognise and reward excellence in WHS, and showcase inspiring career pathways and achievements within the profession.”

Another focus of Vision 2026 is

embedding a culture where workplaces value health, safety, and wellbeing. To achieve this, Whitford said the AIHS has pledged to link researchers with industries that need support, educate employers about WHS career pathways, and provide practical support to assist businesses in applying good WHS practices.

A final focus for the AIHS over the coming three years is strengthening advocacy and policy work. “We will do this by working with governments and legislators to ensure the regulation that governs WHS is aligned to –and supports – good practice,” said Whitford.

“The AIHS is the trusted voice in WHS. We continue to be present in each state and territory throughout Australia with a dedicated group of volunteers who span across state branches and committees. It is through these dedicated individuals and this momentous reach that we use this voice to advocate and influence WHS best practices and policy. As we continue this exciting journey towards a dynamic, well-supported, and growing AIHS, I encourage you all to stay engaged, share your knowledge, and continue this strong collaboration. I’m excited and energised for the future of the Institute as we embrace change and growth and continue the AIHS’s strong tradition of service to the profession.” n

SEPTEMBER 2023 | OHS PROFESSIONAL aihs.org.au 17

How can artificial intelligence advance the cause of OHS?

OHS professionals need to clearly understand what problems they are trying to solve before exploring artificial intelligence solutions, writes Craig Donaldson

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is having a major impact on a broad range of professions, and OHS is no exception. With the potential to improve workplace safety, enhance risk management, and analyse data, AI technology holds immense promise. By analysing vast amounts of data and patterns, these systems can accurately predict potential hazards and identify areas requiring attention. This proactive approach to safety management allows organisations to address risks before they escalate into accidents or incidents.

could replace some dangerous manual tasks (decreasing worker exposure to physical risks), it said workers overseeing the technology could be exposed to more psychosocial hazards resulting from increased or more complex interpersonal interactions as part of their job role.

Another common organisational and functional priority for OHS is compliance. By automating routine administrative tasks, such as data collection and reporting, AI not only reduces the administrative burden on OHS professionals but also enhances data accuracy and accessibility. This point was underscored in a recent International Labour Organization (ILO) research report, Safety and health at the heart of the future of work, which explained how AI-driven technologies can assist in streamlining OHS compliance while assisting with facilitating datadriven decisions, implement targeted interventions, and continuously improve safety standards.

However, new technology capabilities must also be designed and have appropriate oversight to ensure workers are not exposed to new or additional OHS risks. This point was emphasised by Safe Work Australia in its Australian Work Health and Safety Strategy 20232033. For example, while automation

“AI adoption in business sectors has more than doubled in recent years, with optimisation of service operations being its top use case,” said Skye Buatava, research and evaluation director of the NSW Government’s Centre for Work Health and Safety, which recently published a detailed report on the ethical use of artificial intelligence in the workplace, in conjunction with The University of Adelaide and Flinders University.

The use of AI is affecting workplaces around employee recruitment, role design, task allocation, time management, organisational structure, communication, and even how employees are rewarded for their job performance, said Buatava. “Despite the increased use of AI, there has been no substantial increase in organisations’ mitigation of AI-related risks. AI may potentially elevate levels of uncertainty and pose the possibility of unknown risks and hazards to employees, only

OHS PROFESSIONAL | SEPTEMBER 2023 aihs.org.au 18 COVER STORY