IN A FASCINATING DEVELOPMENT, an aviation insurer sems to have recognized this and is ignoring some of the latest CAA rules.

The aviation industry is highly regulated, not just by the CAA, who makes the rules, but perhaps even more so by the insurance underwriters –who determine what is okay – and what’s not.

The standard aviation insurance policy is supposed to be a simple contract. Risk information is provided and an insurance contract is proposed, with the ‘small print’ of definitions, conditions and exclusions. Exclusions usually include a version of: The aircraft and pilot must not contravene the civil aviation regulations (CARs). This can be worrying for an aircraft operator as it is easy to fall foul of the myriad regulations.

Thankfully insurers are not completely unreasonable when it comes to insisting on pilots being rule abiding.

The recent ill-considered attempt by CAA to introduce legislation that effectively would have prevented anyone from landing at an unlicensed or unregistered airstrip was met with howls of protest from the industry. An amendment to Part 94.07.03 meant that the Breach of Air Navigation Regulations clause in the insurance policies would have made off-licenced/ registered airport ops illegal and uninsured.

The charter industry was alarmed at the prospect, as were the ‘weekend warriors’. After consultation with the industry, CAA withdrew the legislation for six months while it is reworked. But much confusion still reigns as to the status of the legislation, and whether aircraft operating out of unlicensed airstrips are still covered by their insurance.

Santam, the largest aviation insurer in South Africa, has continued with its Unlicensed Landing Ground clause, the gist of which places the onus on the pilot to ensure that a landing strip is indeed suitable for landing. This will hopefully calm the fears of the aircraft operators and focus the pilots’ minds on the suitability of a landing area.

As an astute general aviation pilot friend in Cape Town points out; “It is noteworthy that the insurer would have covered me for basically breaking the law initially passed by CAA. I must imagine that this clause was inserted to make aircraft operators happy that they can continue to land at an unregistered game lodge or farm airstrip without negating their insurance. But it might also reflect the insurance underwriters’ belief that sanity will prevail at CAA and the redrafted law will mirror the insurer’s clause.

“Nonetheless, the CAA’s drive to register all airfields is continuing and it has to be asked to what end? Is this a safety and security thing, or a means to raise more fees in the future? Who knows? But once again CAA has done little to convince us that they are working in the best interests of the aviation industry.”

j

The charter industry was alarmed

Douglas Bader is claimed to have said; ‘Rules are for the guidance of the wise and the obedience of fools.’

Five doors, five seats, yet incomparable and unmistakably Macan. With significant enhancements from the previous generation, the Macan S is contemporary, dynamic, urban and built for adventure and endorphin rushes on every drive. Experience the ultimate sports car SUV.

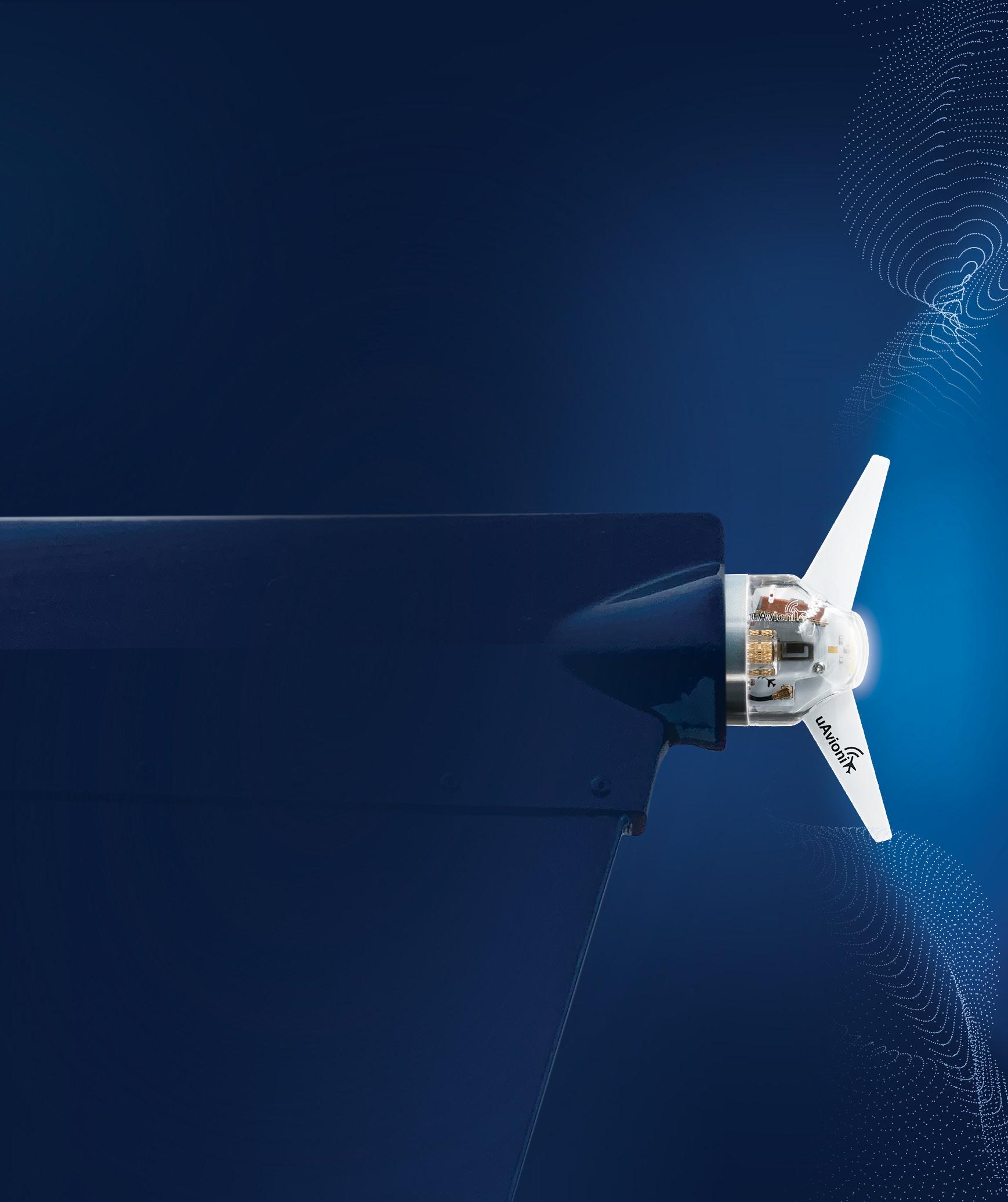

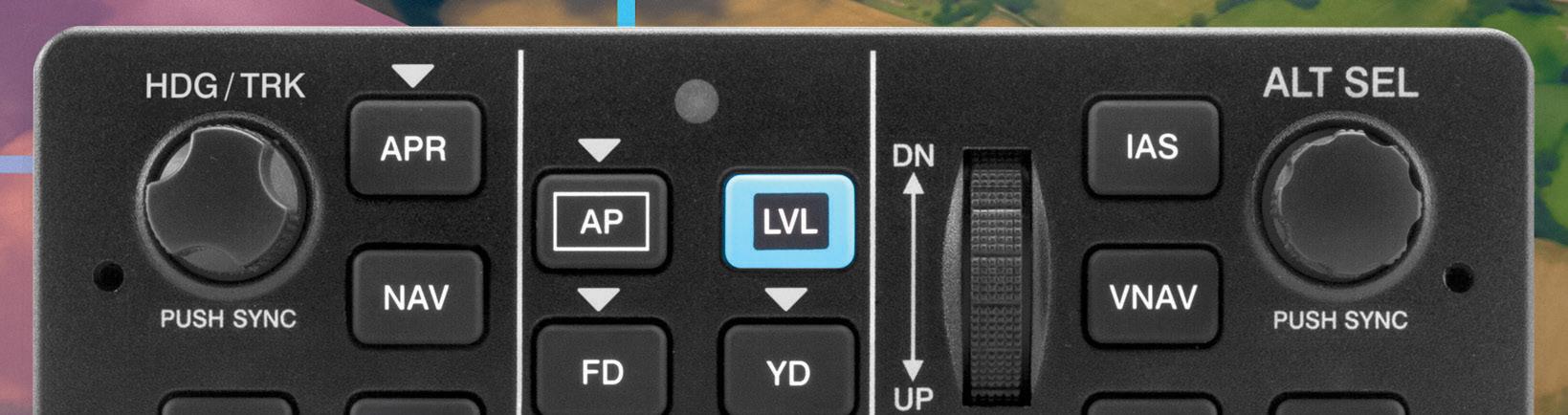

tailBeaconX combined with the AV-30 or supported third-party EFIS elevates your cockpit functionality while future-proofing your ADS-B transponder to meet South Africa, US, Canadian, and future ADS-B requirements. tailBeaconX replaces your existing transponder while upgrading your rear position light.

EASA Approved and Now Shipping

tailBeaconX CONTROLLED WITH AV30

AV30 HIGHLIGHT S:

• PRIMARY AI

• PRIMARY DG

• PRIMARY SLIP

• GMETER

• PROBELESS AOA

• LIVE ADSB TRAFFIC

AV30 ADDONS:

AV MAG STC

• EXT MAGNETOMETER

AV LINK

• WIFI/TRAFFIC

uAvionix.com/tbx

At altitudes like these, a lot can happen. And whether you’re a professional or recreational drone pilot, there are a number of risks that can lead to the damage of your drone. Which is why you need the right expertise to protect your drone from the risks that are obvious and the ones that aren’t. Santam. Insurance good and proper.

more information, visit santam.co.za or speak to your intermediary.

DURAN DE VILLIERS IS PASSIONATE about flying. He flies everything from paragliders to his Eurocopter EC120 helicopter and has now purchased a Bell 204 ‘Huey’.

The challenge when taking a photo out the cockpit is to get the interior and exterior exposures right. This is a perfect example of the art – no doubt assisted by his iPhone cell phone camera’s remarkably smart software. Duran took it from a Starlite Flying School Sling 2 while flying east along the coast towards Knysna.

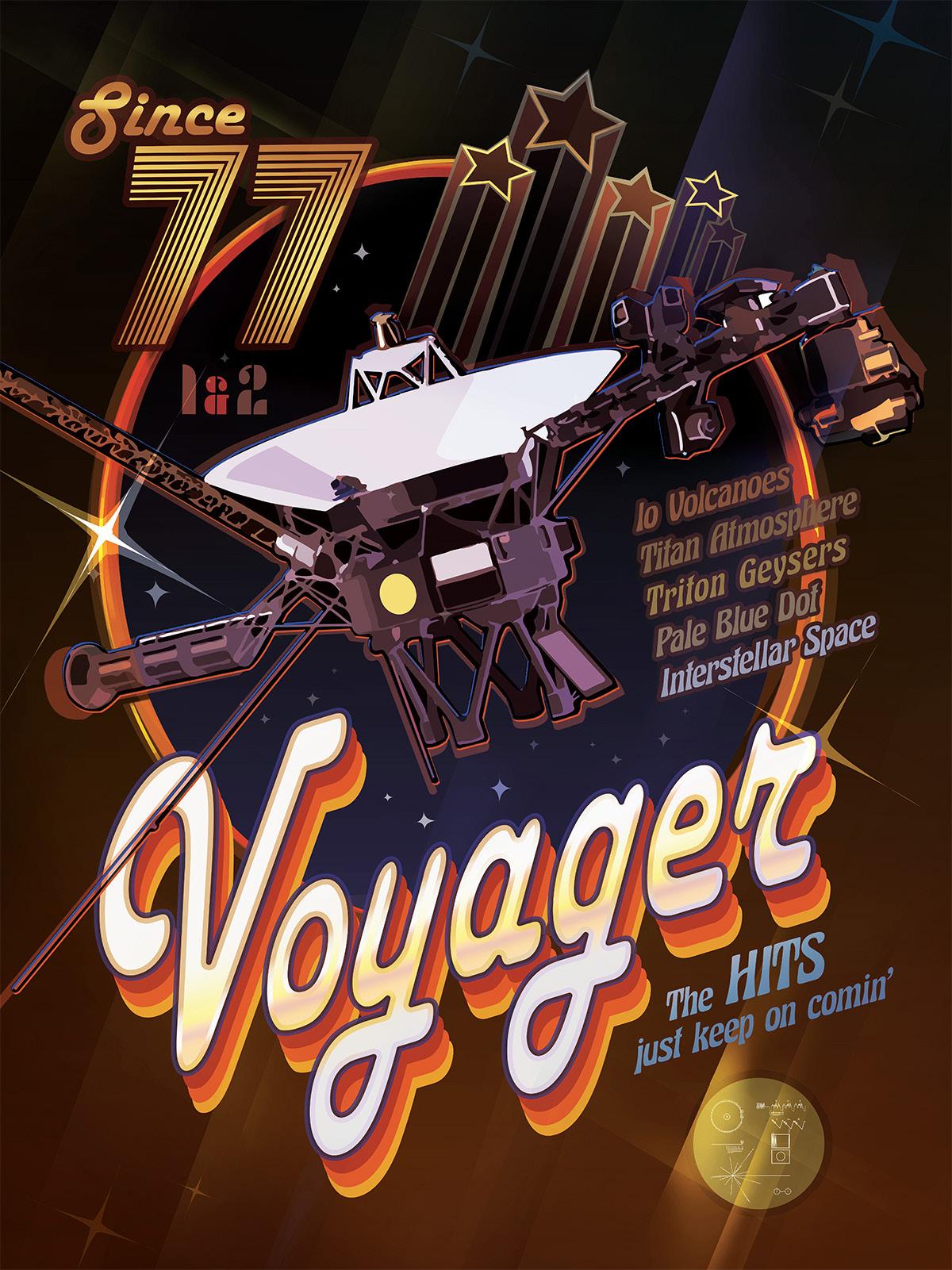

THE TWO VOYAGER SPACECRAFT are quietly getting on with the job of heading out of our solar system and into deep space. At over 61,000 km/h the two little Voyagers are right up there in the list of the top ten fastest objects, and they have been maintaining that speed flying away from Earth for almost 50 years. Both carry the famous “Golden Record,” a 12-inch goldplated disc containing sounds and images about life and culture on Earth.

The Voyagers unarguably own the record for the flying machines with the greatest range and endurance. Forty-six years ago, on 20 August 1977, NASA’s Voyager 2 launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida, on a Titan III-Centaur rocket. It embarked on a “grand tour” of the solar system that included visits to the Jupiter and Saturn systems and would make it the first spacecraft to visit the ice giants Uranus and Neptune and their moons.

Voyager 2 is now more 25 billion kilometres away and still they fly on, transmitting from the depths of interstellar space, rebuking every car and computer that profited from built-in obsolescence.

NASA’s rocket scientists are wondering how long they can keep going. There were glum faces at NASA in early August when the wrong command caused the transmission antenna of Voyager 2 to misalign with Earth – and the spacecraft went silent – possibly forever.

However, NASA said it wasn’t panicking. The mission’s scientists believed they had several options to restore communications with the half-century-old probe. And so they did. In an update in early August, NASA said all is now well once again with Voyager 2.

When they were launched, Jimmy Carter was in the first year of his presidency and Fleetwood Mac was in the charts with Don’t Stop. The two spacecraft took that song to heart and have not stopped ever since, travelling further from Earth than any other man-made object.

NASA’s Deep Space Network facility in Canberra, Australia, was able to “shout” a command to Voyager instructing the spacecraft to reorient itself into a proper position to facilitate communication with Earth.

It took 18.5 hours for the signal to reach the

The title of these columns is Attitude for Altitude –and this is nowhere better demonstrated than by two little spaceships that have real attitude – and altitude.

spacecraft, which is now 20 billion km from Earth. Finally, in the middle of the night, after an anxious wait of 37 hours, Voyager 2 once again started streaming back data.

Voyager 1 and 2 were launched to take advantage of a once-every-176-years alignment in the 1970s that made it possible for spacecraft to take gravity-assisted slingshots from planet to planet across the solar system.

Voyager 1 is currently the farthest spacecraft from Earth at about 24 billion kilometres, while Voyager 2 has travelled more than 20 billion kilometres. Both have now left the solar system and are in interstellar space, making them the only spacecraft to operate beyond the heliosphere, the sun’s bubble of magnetic fields and particles that extends well beyond the orbit of Pluto.

Though it launched second, Voyager 1 was so called because it was to reach Jupiter and Saturn first — in March 1979 and November 1980, respectively — before exiting the plane of the planets where it took the famous “Pale Blue Dot” photo.

Voyager 2 visited four planets: Jupiter in July 1979, Saturn in August 1981, Uranus in January 1986 and Neptune in August 1989.

Voyager’s discoveries are the stuff of legend among planetary scientists, many of whom still rely on the unique images from the spacecrafts’ now antiquated wide-angle and narrow-angle digital cameras.

The probes have taken photos of the volcanoes on Jupiter’s moon Io, and discovered that Jupiter’s Great Red Spot is an Earth-size storm. They studied Saturn’s rings; saw the giant moon Titan’s thick, Earthlike atmosphere; and revealed the tiny moon Enceladus to be geologically active.

Voyager 2 then set off by itself to check out Uranus and Neptune. The spacecraft’s firstever images of Uranus revealed dark rings, the planet’s tilted magnetic field and its geologically active moon Miranda. Neptune, meanwhile, was also discovered to have rings and many more moons than scientists initially thought. We also got to see Triton, a geologically active moon that is orbiting “backward” and, like Pluto, is now believed to be a captured dwarf planet from the Kuiper Belt.

In addition to making groundbreaking discoveries, the Voyager mission helped scientists determine what merited deeper exploration. The mission revealed Jupiter to be an incredibly complex planet, thus spurring NASA to launch the Galileo mission in 1989 and the Juno mission in 2011. The Voyager probes’ work also helped inspire the iconic Cassini mission to Saturn.

the two probes are alone on their cosmic treks

Voyager 1’s close flyby of Saturn’s largest moon Titan was the catalyst that justified the amazing Cassini mission. Cassini’s Huygens probe successfully parachuted onto the surface of Titan in 2005 and sent back an incredible video. This was the first landing ever accomplished in the outer Solar System and the first landing on a moon other than Earth’s Moon.

Voyager 2 has also been a catalyst for investigations into the role of the ice giant planets — not only in the solar system, but also in distant star systems, since most of the exoplanets found so far are roughly the size of Neptune and Uranus.

The big question is, how much longer will the Voyagers last?

Despite the recent communications near disaster, both the intrepid spaceships are still communicating with NASA’s Deep Space Network (which itself was created to communicate with Voyager 2 at Uranus and Neptune), receiving routine commands and occasionally beaming data and images back to Earth from its 1970s era computers. “We’re looking forward to getting data for probably another five or six years,” Stamatios Krimigis, principal investigator for the Voyager Interstellar

Mission, said during a news conference held in July.

To achieve the miracle of keeping these spacecraft alive in the frigid and far reaches of space, NASA is getting creative with the power supply and instruments. Over time, the Voyager team has commanded the probes to turn off instrument heaters and other nonessential systems.

Both Voyagers are nuclear powered, using radioisotope thermoelectric generators. The power pack loses 4 watts per year as the plutonium it relies on slowly decays and its heat is converted into electricity.

Each spacecraft’s power pack carries radioactive plutonium-238. As the isotope decays, it releases energy that is converted into electricity by three radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs). At launch, the RTGs provided each spacecraft with 450 watts of power. Now, they’re producing less than half that amount and their electrical output is decaying by four watts each year. NASA says that it takes about 200 watts to send signals back to Earth, and they only have about five to six watts of power margin on each spacecraft.

In the deep cold soak of outer space, the key challenge is to keep the propellant lines warm above 2 degrees Celsius so the aiming system continues to work.

Voyager 2 has begun using a small backup power reserve, which will enable the spacecraft to keep from shutting down another science instrument until 2026. The power reserve was designed as a safety mechanism to protect the instruments in case the flow of electricity changes significantly on the spacecraft. Now that back-up power is being used to keep Voyager 2’s instruments up and running.

The rocket scientists were thrilled to discover that the instruments recalibrated to become more sensitive in their data collection because some of the detectors operate better when colder.

As the sole extensions of humanity outside the heliosphere’s protective bubble, the two probes are alone on their cosmic treks as they travel in different directions.

Given the age of the two spacecraft it is inevitable that a small failure could ultimately lead to losing communication completely, even

if it still has power. But however long Voyager 1 and 2 continue to operate, the Voyager mission is already a massive success. The original mission was to perform flybys of the solar system’s gas planets and their moons and beam back data to Earth — tasks that both spacecraft had completed by 1989.

Now 35 years later, around the mid-to late 2020s, the probes’ scientific instruments will be shut down, and eventually, the spacecraft will go cold and silent — but their journeys into interstellar space will continue indefinitely.

In around 300 years, Voyager 1 and 2 will enter the Oort cloud, the sphere of comets surrounding the solar system. About 30,000 years later, they’ll exit the neighbourhood and silently orbit the centre of the Milky Way for millions of years.

Their scientific work may be almost over, but the Voyager spacecraft have only just begun their journeys into the cosmos. And who knows – maybe some clever lifeform will find and play Voyagers’ gold plated records and look back to where they came from. j

guy@saflyermag.co.za

Jack Knight’s was not a hero’s face. Neither rugged nor square-jawed, it was, rather, over-broad in the forehead and narrow in the chin, somewhat like Fred Astaire’s or the famous screaming face on the bridge in the Edvard Munch painting. But heroes are as heroes do.

KNIGHT WAS AN AIR MAIL PILOT at the very start of the air mail, years before Charles Lindbergh was. President Warren Harding wanted to shut down the air mail, deeming it unduly dangerous and costly, unreliable and not even especially swift, since mail was flown only by day and loaded onto trains at night. The assistant postmaster general in charge of the air mail, Otto Praeger, in a bid to deflect the presidential axe, set out to demonstrate that mail could be flown through the night.

On February 22, 1921, the night of a full moon, four de Havilland DH-4s took off at dawn, two from New York and two from San Francisco. One crashed in Nevada, killing the pilot. Two westbound planes gave up in the face of a snowstorm near Chicago. By evening, one lot of eastbound mail had been delivered by Knight to Omaha, Nebraska. Bad weather lay ahead, with snow still falling between Omaha and Chicago, and the pilot who was to fly the next leg declined to continue.

Jack Knight took off instead and flew through the night, freezing cold in his open cockpit and guided by bonfires lit by postal employees and by farmers. He refuelled at Iowa City, remarking later with some understatement, “Say, if you ever want to worry your head, just try to find Iowa City on a dark night with a good snow and fog hanging around.”

By morning he had reached Chicago, where another aeroplane took his cargo and continued to the east coast, completing the transcontinental trip in 33 hours.

Knight had no radio. He navigated by a combination of dead reckoning and pilotage. Pilotage means flying from one visible landmark to another, but in the midwestern night before rural electrification, few visible things were to be found. Dead reckoning means calculating your location from time, speed and direction of travel. With dead reckoning, here was seldom exact,

but it was good enough that Lindbergh made his landfall in Ireland, after 20 hours over water, right where he expected to.

In principle, you would dead-reckon from one unmistakable landmark to another; but alas, from time to time the next landmark would fail to appear, and that would “worry your head.” You would get the tense, creepy feeling of being lost in the sky. It was different from being lost on the ground; in the sky, there was a deadline set by fuel. No one liked the feeling, but still, it had a value: It reminded you that what you were doing was dangerous.

The night mail officially began operations in 1924. To provide its pilots with the landmarks that the countryside begrudged them, the Postal Service set up the first airway system. It was defined by electric beacon lights; Jack Knight helped lay them out.

At one time 1,500 beacons marked 18,000 miles of airways. I followed them across Arizona in a Cessna 175 in the 1960s, but by that time the system was being dismantled. There was something sweet and warm in a beacon winking at you from a distant mountaintop, something

that the chill abstraction of a radio signal lacked. The only remnant of the beacon airways today is a string of 17 lights in the mountains of western Montana, maintained as a historical artifact by the state.

The beacon lights were supplanted by fourcourse “Adcock ranges.” Four-course ranges were low-frequency beacons like NDBs, usually located near airports, and set up to broadcast in four lobes roughly corresponding to the quadrants of a circle. In one lobe and the one opposite it the signal was the Morse letter A, dot-dash; the other two were dash-dot, N. Within the narrow “courses” where the lobes overlapped you heard a continuous tone. Chains of these courses formed airways; some were aligned with runways to provide primitive instrument approaches.

As you may imagine, to fly a range approach required a firm grip on oneself and a welldeveloped ability to transform random and obscure symbols into a mental map of the world and where you were in it.

Underlying that map was our old friend dead

Navigation, a great and noble art

reckoning. Besides calculating speed, time, distance and drift over long distances, dead reckoning also meant maintaining a sort of intuitive situational awareness on a local scale.

The four-course range was not just a bewildering cacophony of dots and dashes but an inner space in which an imaginary aeroplane, felt rather than seen, crept along. VOR, the

successor to the four-course ranges, preserved and augmented the airways system they had defined. It replaced the aural with the visual and made navigation infinitely more precise. It also made IFR flying more expensive because, for the first time, you needed something more than a simple audio receiver and headphones in the cockpit.

GPS, and the complex digital processing it makes possible, has changed all that. A drug seductive to even the fiercest Luddite, GPS

makes skill, knowledge and intuition obsolete. It makes us at once infants and gods. Observer and observed, we watch from on high as our icon creeps across the map. With GPS, there is no longer such a thing as “lost”.

Navigation, a great and noble art whose traditions stretch back into prehistory, has been replaced by a computer game. Its tools, the products of so much experience, ingenuity, daring and self-sacrifice, will soon become curiosities; its methods and skills, so recently the barrier separating life from death, will be forgotten.

Jack Knight’s night flight more than a hundred years ago must be, to new pilots who have trained in the era of GPS, all but unimaginable. His aeroplane, a two-place biplane designed during the First World War and modified to replace the front cockpit with a hold for 400 pounds of mail, could do 100 knots or so and stay aloft for nearly four hours. The cold, the darkness, the din of the 400-hp Liberty engine far out in front and the endless peering into darkness unrewarded for long periods by any answering light – these were trials to which we

modern pilots, snug and cozy in airtight cockpits and ministered to by a crew of digital assistants, weather forecasters and ground controllers, are strangers.

We are much better off, but we have also forfeited something: an adventurous life in which anxiety and relief alternated like the beating of a heart.

Beryl Markham, one of the pilots of that rash and risky era, foresaw what was to come, and in her autobiographical ‘West With the Night’ she wrote of the future we now inhabit:

By then men will have forgotten how to fly; they will be passengers on machines whose conductors are carefully promoted to a familiarity with labelled buttons, and in whose minds the knowledge of the sky and the wind and the way of the weather will be as extraneous as passing fiction.

ASK A DOZEN PEOPLE WHY the sky is blue and you will get a dozen woolly answers about refraction and reflection but not one honest, I don’t know. So nobody learns anything.

And now ask a dozen pilots why Madame Beech or Mr Piper put a rudder on their aircraft and you will hear all sorts of bull – but very few will answer, it’s mainly to counteract design problems like aileron drag and P factor. Much more on this later.

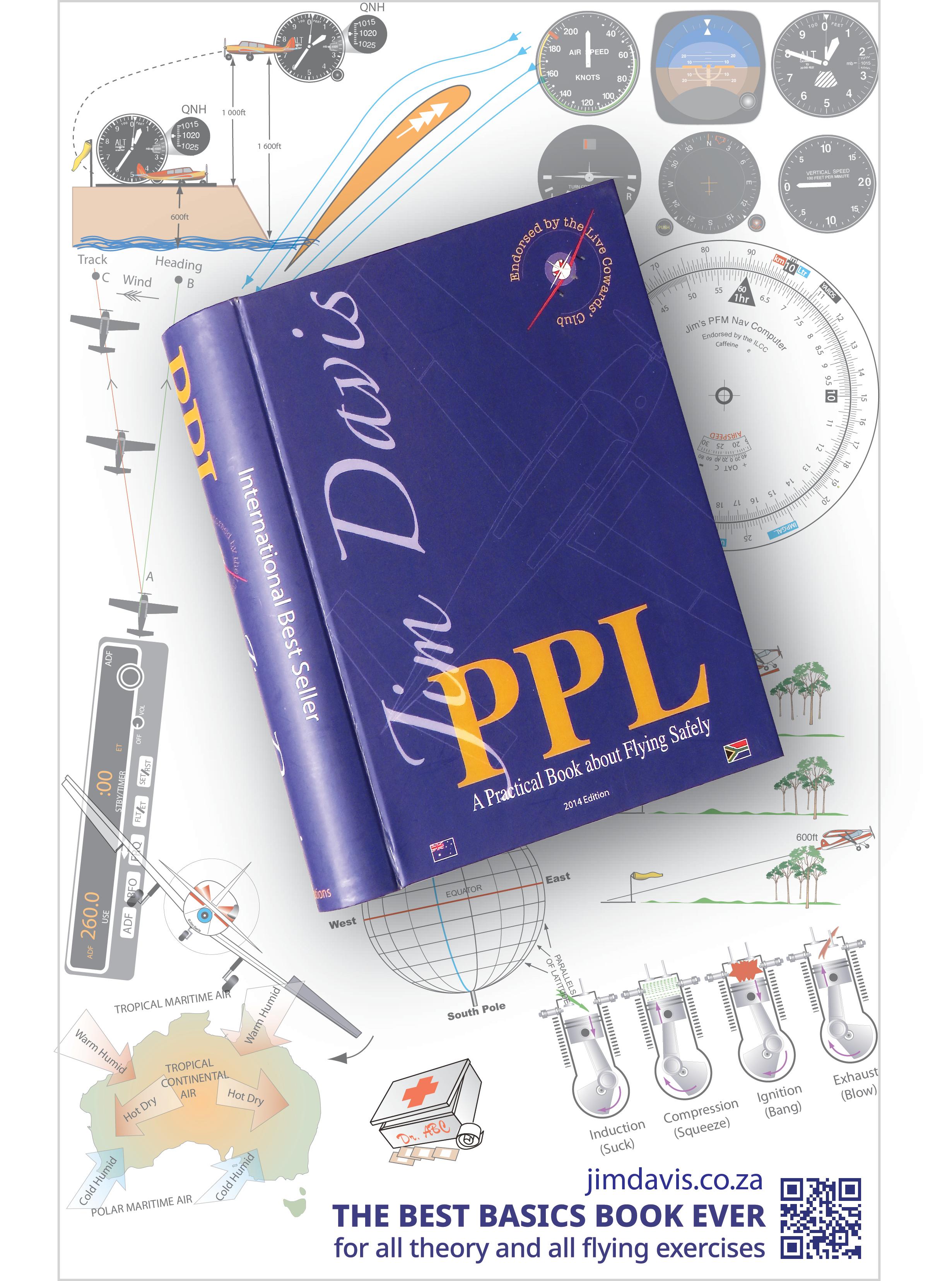

Back in the days when Pilate was only a student, I wrote a slender document called “Patter for Instructors”, or something. It worked well –instructors liked it and so did the DCA (which later became the CAA). So I updated it a bit and most of the flying schools in South Africa copied it – which was fine – actually quite flattering. I was trying to make a living from training pilots –not selling bits of paper.

Forty years later, when I sold my flying school, three of the instructors cosied up to the CAA and decided to turn this little ten-page book into something really impressive. They formed committees and sub-committees to advise each other. They were determined to improve my slender guide and make it so comprehensive that no one would ever use it.

They turned it into an AIC – 333 pages of dense text with the impressive name DOC NO: DP/ FTD/TS/05/009 Flight Instructor’s Training Procedures, Revision No: 07. DATE AMENDED: 26 October 2009

Imagine coming back to your bachelor pad, after a hard day at the office, to study this by candlelight during load-shedding. I believe this boring document, with its paragraphs and sub-paragraphs, sub-subparagraphs and roman numerals, has single-handedly caused our terrible shortage of Instructors.

The exercise – Effects of Controls – from a single page, now takes up 30 pages and includes things like the effects of carb-heat. Why not chuck in cabin-heat and the door handle as well? They both have just as much potential to kill you if you get them wrong.

They missed the point of the whole thing. The document was meant to teach new instructors the best way of training pedestrians in the art of handling basic aeroplanes.

Which reminds me – a pupe did indeed try to kill me by getting the cabin-heat wrong. So perhaps I should revise my thinking on the whole thing. Anyhow, here’s what happened.

We Saffers are ever reluctant to use the magic words, I don’t know.

our terrible shortage of Instructors

I was training a group of enthusiasts at Swellendam. They were a good bunch and we were having huge fun playing with rudimentary aeroplanes away from controlled airspace. Honest flying.

But I need to tell you about this one pupe who simply wasn’t hacking it. His name was Hendrik. He was a hell of a decent guy so I am doubly reluctant to speak ill of him –but facts is facts. If I describe the classic village idiot sitting on a wall with straw in his hair, taxi-door ears, rabbit teeth and the puzzled demeanour of a sheep who has found his path impeded by a mangelwurzel, you will have a picture of Hendrik.

Poor guy – not his fault, that’s simply the way they had kitted him out at birth. Those who constructed him, both mentally and physically, did not have aeroplanes in mind at the design stage.

Anyhow I am doing circuits and bumps with him in a delightful little Piper Cruiser, and they are not going well. While Hendrik’s body was in the aircraft, his mind was sitting on a stone in the sun, chewing a piece of grass.

We were doing a glide approach on runway 33 (the uphill one) when all the cheese-holes became aligned with the planets. In those days, most training landings were from glide approaches that started at 1000 ft on base.

In the last few seconds Hendrick had done two things wrong. He had started the glide too early, and he had forgotten to use carb-heat.

Now before going on, I should tell you that the Cruiser has fore-and-aft seating – like a Cub. The instructor sits in the rear and has access to only three controls – the stick, the rudder and the throttle. Apart from this, you can see little more than the back of the pupe’s head unless you loosen your seat-belt and move forward to peer over his shoulder.

So although a Cruiser is huge fun, it’s not the ideal training aeroplane.

Anyhow, there we are in a glide with no carbheat – so the engine is going to stop fairly soon. This would be fine if we were able to make it to the field – but we weren’t.

Nothing happens, so I repeat my request a little louder. We didn’t use head-sets – we just shouted. But the comparative silence of a glide approach made comms pretty easy. It wasn’t

that he couldn’t hear me – it just wasn’t getting through. His mind was still sitting in the sun chewing grass.

“Carb heat!” I shout, and tap him on the shoulder.

He is made of rubber. His head twists round 180 degrees, like a turkey, and he seems surprised to find someone else in his vicinity.

I point at the panel and repeat my instruction slowly as if talking to a snotty infant.

He faces ahead again and yanks out the mixture.

The engine noises cease, and the prop slows to a gentle windmill.

“Not that one,” I screech. So he pulls another knob that works the cabin-heat. But leaves the mixture out.

I seldom shout at a pupe, but this calls for decisive action, so I bellow at him to push the red knob – the mixture – in.

There is only one other red knob in the cockpit – it’s the throttle on the left sidewall, just below the window. So that’s what he goes for. The only thing that changes is the expression on his face as he again swivels his head round to give me a helpless look. Of course the throttle makes not a damn of difference, because the mixture has killed the engine.

I grab the controls and we skim over the dirt road and plonk down in a boulder-strewn area 50 yards short of the runway. And stop almost immediately.

This exercise is both critically important, and boringly obvious. It’s like learning to swim – you had better get it right, but once you have the basics of flying, or swimming, you may never need to give them another thought unless you go in for instruction, aerobatics or aquatic sport.

There is no damage, but I have to get out and swing the prop to get us to the numbers – and thence to the hangar.

Ask the average commercial, or even airline pilot, to describe the effects of the controls, and you will get an old-fashioned look and some vague muttering. Or they might laughingly tell you about “the houses”. Push the stick forward and the houses get bigger. Pull it back and the houses get smaller. Pull it further back, and the houses get bigger again.

Sorry about the side-track. I was just letting you know that under the ‘Effects of the Controls’ we will not cover all the controls – like that ridiculous AIC. We only do the three main flying controls. We cover the flaps separately, and the rest as they come up during the training.

Actually, this is so important (as was your first swimming lesson) that I am going to walk you through the pre-flight briefing and patter – before we look at the actual flying exercise.

Remember the golden rule:

Tell me and I will forget Show me and I will remember Involve me and I will understand

So you are going to do all three. You will tell her about the effects of the three main flying controls, using a model aircraft in your briefing room. Next, you are going to demonstrate how they work, in the real aircraft. And finally you are going to involve her by letting her fly herself and try out the controls one at a time.

By the way, patter means the words you use in the air, as you talk her through the exercise. For some exercises you need to learn it pretty much by heart otherwise the aircraft is likely to complete the exercise while you are stumbling along behind it groping for the right words.

Remember that the aeroplane is a terrible classroom – because of the noise, the distractions and the lack of face-to-face contact. For this reason – try to avoid teaching in the cockpit. Most of the teaching and learning should happen in the classroom or the briefing room.

Well they are both wrong – you don’t need to be a thief, a street hawker, circus barker, comedian or entertainer to use patter – you need to be a top-line flying instructor.

Remember to have the model pointing away from the pupe, and to start each control response from straight and level flight.

The stuff in blue is a reminder of what to say in the briefing and is also the actual patter you will use in the aircraft.

We will start with the PRIMARY effects of the three main flying controls.

This warrants a bit of discussion. Mr Chambers’ splendid dictionary claims that patter is: chatter, gabble, jabber, line, pitch, jargon, monologue.

Madame Merriam-Webster is a little more verbose on the subject, she thinks ‘patter’ means:

• a specialized lingo: especially: the jargon of criminals (such as thieves)

• the spiel of a street hawker or of a circus barker

• empty chattering talk

• the rapid-fire talk of a comedian

• the talk with which an entertainer accompanies a routine

• When I ease the stick back – like this, the elevator on the tail moves up, this decreases lift there, so the tail moves down and the nose moves in the direction of the cabin roof.

• When I ease the stick forward – like this, the elevator on the tail moves down increasing the lift there, so the tail moves up and the nose moves in the direction of the undercarriage.

• This movement is known as pitching.

• The aircraft pitches about its lateral axis –which runs from wingtip to wingtip.

• When I ease the stick to the right – like this, the right aileron moves up, decreasing the lift on the right wing, while the left aileron moves down, increasing the lift there. So the aircraft ‘banks’ to the right, with the right wingtip moving in the direction of the undercarriage. Obviously, if you move the stick to the left the aircraft ‘banks’ that way.

the aeroplane is a terrible classroom

• This ‘banking’ movement is known as rolling

• The aircraft rolls about its longitudinal axis which runs from the spinner, between our seats to the tail.

be more elegant to say that the nose moves towards the undercarriage, or the wing tip. But that’s not strictly correct – it doesn’t move one millimetre towards anything.

• When I press on the right rudder pedal – like this, the rudder on the tail moves to the right. This causes the tail to move to the left and the nose moves in the direction of the right wingtip. Using left rudder causes the tail to move to the right and the nose moves in the direction of the left wingtip.

• This movement is known as yawing

• The aircraft yaws about its vertical axis which runs from the undercarriage, up between our seats and to the cabin roof.

Notice that I use rather clumsy terms about the nose moving ‘in the direction of’ the undercarriage, the cabin roof or a wingtip. This is necessary because the controls always have the same effect relative to the aircraft.

For instance, if you are banked in a turn and you ease the stick back, the nose will not move vertically up – it will still move in the direction of the cabin roof. In other words, it will tend to pull the aircraft into the turn.

If you venture into aerobatics one day and you have the aircraft inverted, easing the stick back will still move the nose in the direction of the cabin roof – which will be down.

Also, if you are banked, say to the right, and you use right rudder, the nose will move in the direction of the right wingtip – in other words it will move down and cause you to lose height.

Finally, in defence of the clumsy phrase, it would

So remember – the PRIMARY effects of the controls are all relative to the aircraft – not relative to your main reference – the horizon.

Unfortunately the ailerons and the rudder both have FURTHER effects, meaning an additional effect that’s not necessarily desirable – it’s just a fact that you must be aware of and make corrections for.

Remember that if you move the stick to the right, the right aileron moves up – reducing the lift on the right wing, and also reducing the drag. At the same time the left aileron moves down, causing more lift and more drag. This differential drag will cause the nose to move to the left.

So, although you have moved the stick to the right – the nose will move in the direction of the drag on the left wing.

But this only happens when the ailerons are deflected, so if you centralise the ailerons, as you do once established in a turn, then that differential drag disappears.

Don’t worry too much about it at the moment – we will deal with it again later under a coordination exercise.

The further effects of the rudder

Remember that the right rudder moves the nose in the direction of the wingtip – so the nose yaws to the right. This means the right wing slows

ailerons and the rudder both have FURTHER effects

down and the left wing, on the outside of the turn, speeds up and gets more lift. The result is that as the aircraft yaws to the right it also banks to the right.

All a bit tough to get your head around? So here’s a table to make it easier:

Okay – so that’s what you teach in the lecture hall, and in your briefing. Once you are in the air you just need to remind her by using key words as you patter her through the exercises.

Do it properly and it works beautifully.

And I haven’t yet explained why aeroplanes need a rudder. That, and some more patter next time.

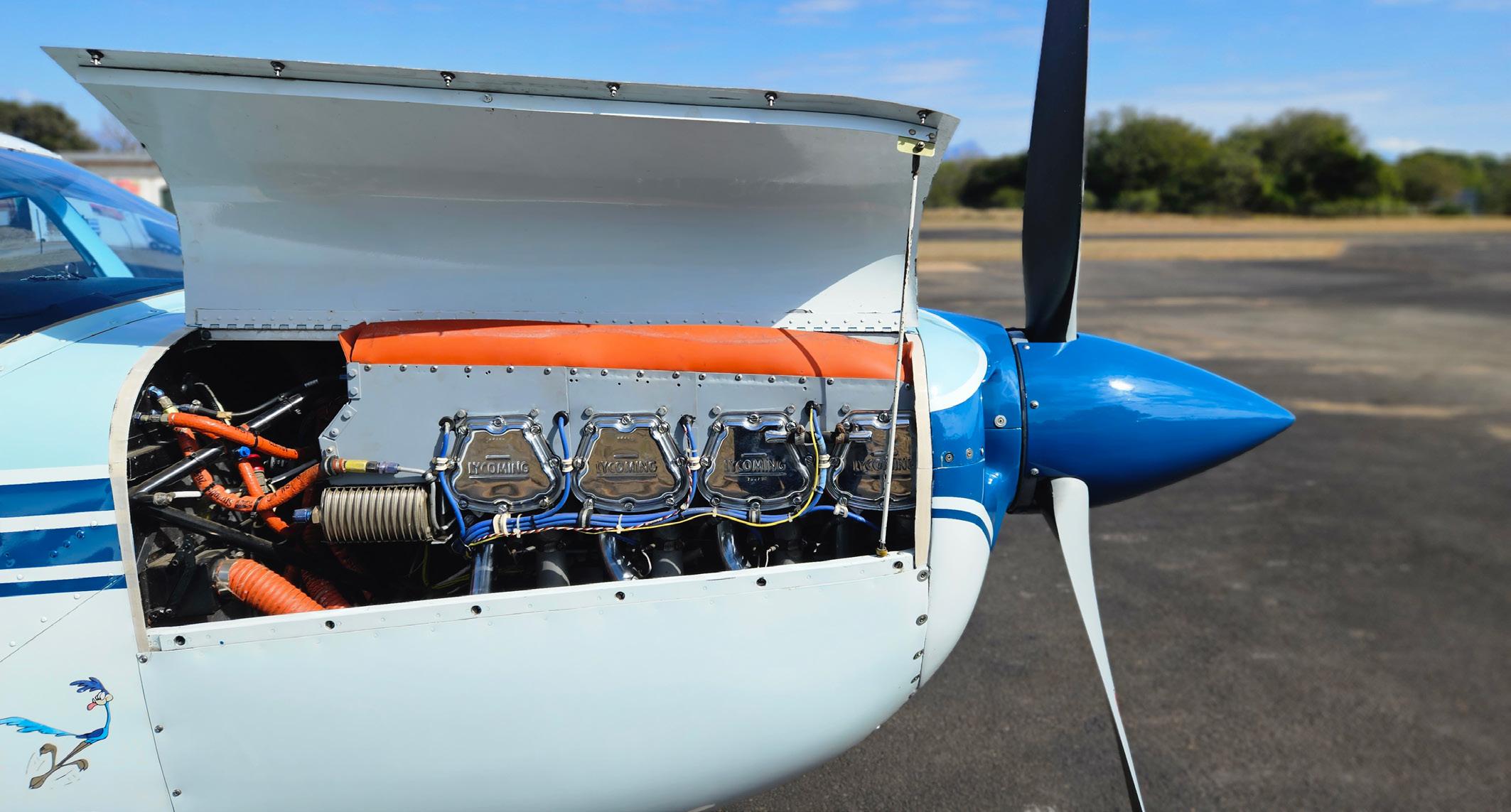

SOUTH AFRICA HAS ONE of the few remaining Comanche 400s and the type of pilots who have owned it say much about its character.

The subject of this flight test is ZS-DZZ and it was first owned by the indomitable Victor Smith – famous for his “Open Cockpit over Africa” exploits. It was then owned by South Africa’s Formula 1 champion Dave Charlton and is currently owned by Presidents Trophy Air Race uber-competitor, John Sayers. These are all pilots capable of taming the 400 galloping horses bolted onto the nose of Piper’s most svelte design.

When asked why they liked the Comanche 400 so much, both Dave Charlton and John Sayers have much the same answer – “Because it gives Baron speeds, with the cost and maintenance of just one engine.”

John Sayers has campaigned ZS-DZZ across many Presidents Trophy Air Races. A quick search through race results shows John roaring around the course at 195 knots – beating a number of Baron 55s. ‘nuff said.

The 400 sure is capable – but what’s it like to fly? Is it a rampaging monster - or a purring pussycat?

There is a popular saying that you can’t have a plane with too much power. Piper put that to the test when they increased the engine in their beautiful Comanche from 180 hp to a stonking 400 hp. So – does it have too much power?

Victor never got to full throttle

Jim Davis shares his insights into this extraordinary muscle plane.

If you listen to a pod of Piper pundits discussing their favourite aircraft. Some will insist that the Comanche is the greatest aeroplane of all time.

Comanches came with varying amounts of zing–anything from 180 to 400 horsepower. Many aircraft grow with time, but Piper planned the growth of the Comanches from day one. Here’s a 1956 news item from Lock Haven:

“The new four-seater Comanche might almost be mistaken for a wartime fighter because it is an all-metal, beautifully streamlined aircraft with retractable tricycle landing gear and an almost fighter-like cockpit canopy. The prototype is powered by a 180 hp Lycoming engine but future models could have various engines up to 400 hp, giving the Comanche something akin to the performance of a wartime fighter too."

This is a fascinating forecast because it shows the excellent relationship William T Piper had with Lycoming. There was no such thing as a 400 hp Lycoming at that time – so Piper got them to build it specially for his Comanche.

Unfortunately that didn’t turn out too well. The

400 was a magnificent aeroplane, but the market wasn’t ready for it. Also it had an undeserved reputation for hot-start problems. So only 148 were built, making it a pretty rare bird.

I was lucky enough to fly a 400 from time to time. Victor Smith owned ZS-DZZ, one of at that time only two in Africa. I had a little flying school at the old airport at George. Victor would phone me, “Davis, I need to do some instrument flying. Meet me at my hangar at 2.35.”

This was not a request. It was a military-type order which meant that I had to drop whatever I was doing and either fly or drive the ten miles to Victor’s little grass strip on the edge of the Serpentine River at Wilderness.

Of course, Victor didn’t want to do instrument flying – he wanted me to come and play aeries with him. I suspect the phone call was to convince his wife, Betty, that this was important aviation stuff that had to be complied with.

Comanches handle like Spitfires and they look magnificent. I can’t think of a prettier aeroplane

than a Comanche with tip-tanks. And there’s nothing that will take you that far in so much comfort and style.

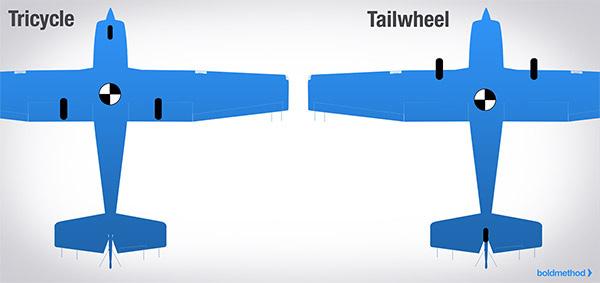

As you pull a Comanche out of the hangar the first thing you will notice is the big nosewheel – the same size as the mains. Not like the baggage trolly wheel on the Bonny and the 210.

A Comanche sits low and solid on the ground, and she handles rough surfaces and crosswinds very comfortably.

After pre-flighting you step up on to the wing and then deep down into the sports-car like cabin and sink into the red leather upholstery. All Comanche cockpits smell of avgas and luxury.

When that big 400 Lycoming is cold she starts instantly and the three blades shudder into a blur as the eight cylinders come alive with a deep throated growl.

Takeoff in a 400 is something else. We would sit at the threshold of this little grass strip and Victor would take his feet off the brakes and start winding in the vernier throttle. There’s no Maserati howl from the engine, it’s more of the rumble that you get from a big-bore V8.

The aeroplane doesn’t leap from the block like a race-horse out of the gate. It just pushes you firmly in the back with an ever increasing force as the rumble gets louder.

Victor never got to full throttle on the ground –he would still be winding in the power as we flashed across the river and watched the beach and the palm trees sinking below us.

Before takeoff in the 400 make sure that you wind in plenty of right rudder trim – you will need it by the time you get to full throttle. Acceleration may be rapid, but don’t raise the nosewheel too early – she likes to accelerate level.

She’s ready to fly at 70 -75 mph and will climb strongly as soon as she leaves the ground. There is none of that wallowing that you get with a heavy Mooney, Bonanza or Centurion.

As you pull up the undercarriage, retract flap and reduce power, she continues to climb and accelerate solidly. Comanches don’t mess around when they leave the ground.

You can’t expect a 60-year-old machine to be quiet by modern standards. You can get by

without head-phones but it’s not fun. A lot of the noise comes through the windscreen, and the optional, thicker, one-piece, curved windscreen is much quieter.

Like a sports car, the Comanche is a wonderful aircraft to play with. The controls are crisp and well-balanced at normal speeds. She sails round steep turns without adding power and without seeming to slow down. But at very low speeds she does wallow a bit and needs plenty of rudder.

Stalls are gentle and straightforward as long as you have the ball in the middle. In an unbalanced stall she will drop a wing, and the

a very soft spot for

rudder is slow to correct this until you have a bit of airspeed – which means losing a fair amount of height. It’s also easy to induce a secondary stall if you try to recover too quickly. But inadvertent stalls are unlikely, because you are warned by a strong aerodynamic buffet.

If you enjoy doing circuits and bumps you will love the Comanche. Her raw power keeps you busy round the circuit. And when you get the knack of landing a Comanche it’s an absolute delight. Ground-effect helps you to squeak the main wheels on, with that long nose so high you can’t see the runway.

Comanche flaps can give you a nasty fright if they are not maintained properly. I have twice had a Comanche try to roll on me when retracting the flaps. It’s possible for one to stick on its way up (not going down). This leaves you with one coming up and the other staying down. Once

you know about it, there is no problem. In fact Comanches taught me a good habit – to keep my hand on the flap (and undercarriage) selector until the job is done. If a Comanche starts to roll as you retract the flaps, just move the selector down and the problem is over.

Some say it is a bitch to land. If you have a forward CofG she can run out of elevator during the hold off. But so can a 182, a Cherokee Six, a Seneca and a Beech Sundowner. That’s why Piper gave us electric trim. Simply put your thumb on the button and roll it back as you round out and she touches down like a fairy.

If you need to go-around at the last minute then you have got to be strong with the forward pressure – but again, you just press the trim button and your problems melt away.

And talking of CofG, Comanches never have that Bonanza nonsense of sitting on their tails. Load it any way you like and the CofG always stays within the envelope.

Flying DZZ with Victor, our ‘instrument flying’ would consist of, “let’s see how quickly we can get to 10,000ft”. Then Victor would say, “Look at this” as he levelled off. And we would watch the needle move steadily round to the 220 mph

mark in the TAS window of the ASI. Or he might say, “I think I need to practice a few stalls and steep turns – would you like to have a go first?” Then sometimes we found it necessary to whip over the Outeniqua mountains to Oudtshoorn for a couple of practice forced landings, and some circuits and bumps.

Perhaps this is a good place to tell you that although the Comanche is seen as a hot-ship, this is a largely undeserved reputation. All the Comanches fly like proper aeroplanes. Certainly, if you pull them too tight in a turn, without enough airspeed, they will shudder and flick. But so will any self-respecting aircraft. Maybe not a Cub or a Colt, but then if a pilot ignores the stall warning and the shudder, should he really be allowed out on his own?

A Comanche is just an ordinary aeroplane. There’s no need to be frightened of it – treat it with respect and it will reward you in spades.

When we came back to his little strip of grass next to the river, it never seemed too short. We would rumble over the reeds at the edge of the lake with full flaps at 75 mph and sink gently into the grass at the threshold. Mostly we didn’t

need brakes because Victor knew how to fly an aeroplane.

Wonderful times in a spectacular aircraft.

You may be wondering why such a brilliant aircraft should go out of production. It’s a sad story. [queue ominous music please].

1972, enter stage left the villain of the piece – Agnes. She was the worst hurricane in American history. She twisted her way up from Florida and dumped nearly a metre of water on Pennsylvania, killing 129 people. Mr Piper’s factory at Lockhaven was one of the casualties. The Comanche’s dies, jigs and tooling were completely wiped out.

This was the second flood, and it killed the Comanche range, including the Twin Comanche. Word has it that it was an accountant’s decision to discontinue the Comanche tribe – no red blooded pilot could ever have made that terrible mistake. j

The first, and littlest Comanche, the 180, is an absolute delight. Not because it’s a great performer – it isn’t. In fact none of the single Comanches perform like modern glass aeroplanes. But then they are 50 or 60 years old. And they are roomy and comfortable. It’s like comparing an E-type Jag with the latest Porsche 911.

The 180 is nimble, and light as a feather. It has that beautifully simple carburettor, O-360 A1A Lycoming that always starts on the third compression. And even with the slightly shorter nose than its big brothers it’s still a very pretty aeroplane.

Actually one taught me an important lesson about pre-flights. It has, in common with many other Pipers, those sensible engine cowls that you can open with a couple of clips. I love it.

How can you preflight an aeroplane without looking at the engine?

Anyhow, I preflight this 180 in the gloom of a hangar without a torch. I fiddle with the plug leads, inspect the primer lines, view the engine mounts and check the exhaust flange gaskets –which are prone to blowing. It all looks fine.

We take off on a sparkling clear morning with the Outeniqua mountains so clear you can almost touch them. As we turn downwind there is a slight burning smell. Suddenly smoke billows from the engine and the slipstream whips it away over the wing. I yank the throttle back, turn towards the field, chuck out the gear and flaps and land on the cross runway – completely forgetting to turn off the fuel.

Smoke is still pouring out of the cowling so I leg it to the terminal building, come back with an extinguisher, open the cowl and give it the berries. It is all over in moments.

The frightening thing is that it was entirely my fault. If I had pre-flighted in the sunlight, or used a torch, I would have seen the massive rats’ nest in the bottom of the cowl. Sorry, fellow bunny-huggers, I don’t know what happened to the darling little furry inhabitants.

Before leaving the 180, I have to admit that speedwise, the beautiful Comanche wing is not quite as good as it looks. The boxy, short-wing, 180 Arrow is about 3 mph faster than the 180 Comanche at pretty much the same weight. But then the Comanche glides like a Grob, while the Arrow doesn’t so much glide as plummet.

But it’s a brilliant wing for long distance flying. In November 1959, my hero, Max Conrad, flew a 180 Comanche from Casablanca, in Morocco, non-stop to El Paso in Texas. That’s just short

of 7,000 miles (11,211 km) in a little 180 hp aeroplane. And that record still stands today.

The 250.

I have a very soft spot for this aircraft, probably because the 250 is the Comanche in which I have the most time.

Comanches are renowned for their long legs. In the days when my bladder could match the aeroplane’s, I flew a 250, ZS-DPL, from Rundu to George non-stop with three up and plenty of clobber. That’s 960 nautics or 1100 statutes, and we arrived with enough fuel to divert to Cape Town or PE. We may have been a tad over gross at takeoff, but the Comanche doesn’t mind in the least.

But that’s nothing. In June 1959 Max Conrad flew his 250 Comanche non-stop from Casablanca to Los Angeles. That’s 7668 miles (12,340km) breaking the record for that class. That’s Cape Town to Edinburgh and you would still be able to fly another 1300 miles.

In 1962 the 250s stopped using manual flaps and came out with electric ones. Actually I prefer the manual ones – there is nothing to go wrong, they are quick to operate, and you can tell what setting you have by resting your hand on the lever.

A thing I really like about the 250s is that they mostly came out with carburettors on their O-540-A1A5 Lycomings. That makes for easy starting and less to go wrong.

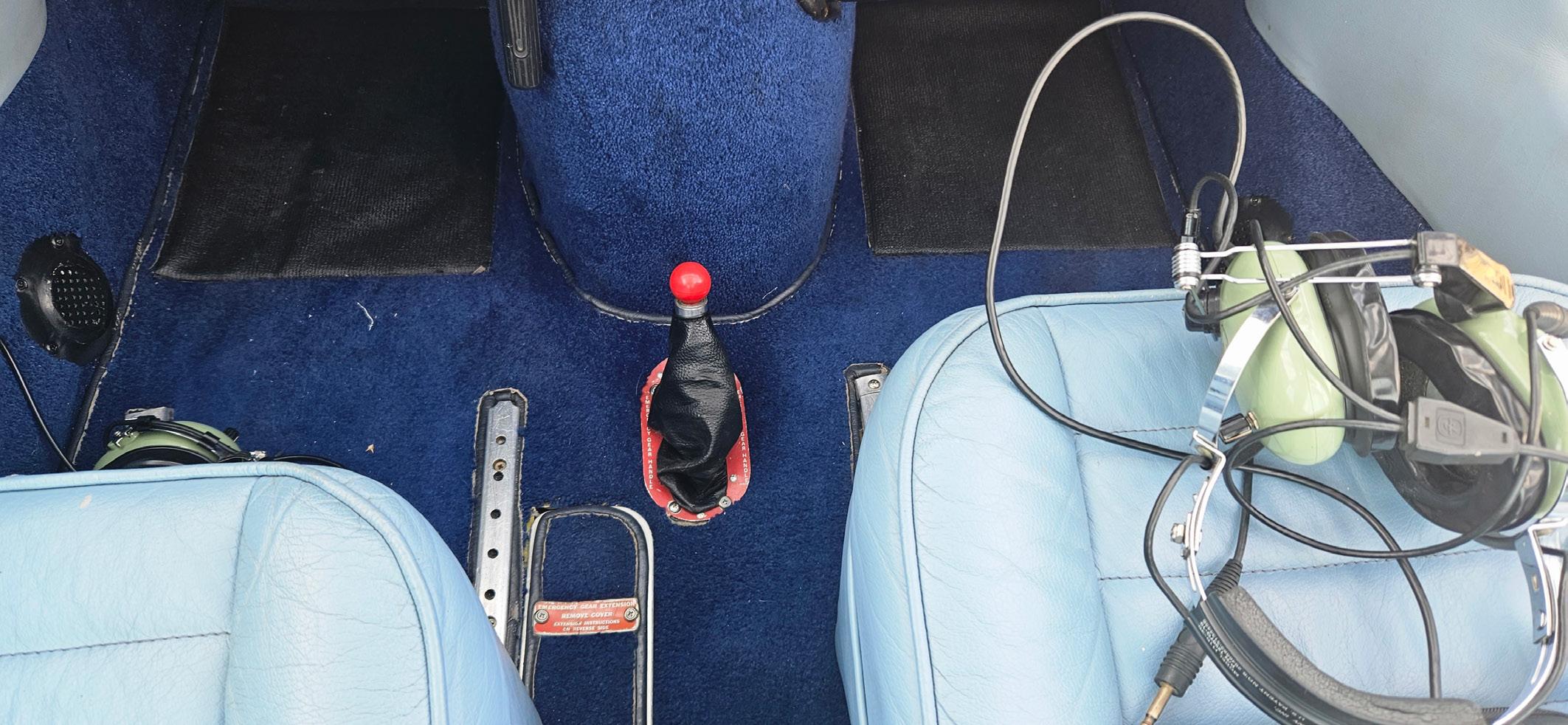

The undercarriage is also nice and simple. It has a direct mechanical linkage to a lever (Johnson bar) that’s hinged on the floor below the centre of the panel. The early ones were manual like the older Mooneys – same designer.

On the later models the lever is telescoped into a stub which you can extend to work the gear

manually should the electricity fail. It’s comforting to drop your hand to this stub and feel it rotate until the gear clonks into place.

Perhaps the 260 is the most interesting member of the tribe because it came in four flavours: Carburetted, fuel injected, six seater and turbocharged. I hasten to say that the six-seater isn’t really, it has extra windows and a couple of kids seats which take up the entire boot.

To my mind the ultimate Comanche is the turbocharged 260 six-seater with tip tanks. With enough fuel to go 2000 miles you can still put 730 lbs in the cabin.

Conrad wasn’t the only one to choose Comanches for record breaking. Sheila Scott used her 260, G-ATOY, called Myth Too, to fly solo round the world in 1971 and then go on to break more than 90 other world records, including first single engine aircraft to fly over the north pole.

Aircraft registration: ZS-PHB

Date and time of accident: 27 August 2016 1025Z

Type of aircraft: Cessna C182Q

Type of operation: Private (Part 91)

PIC license type: Private Pilot

License valid: No

PIC age: 39

PIC total hours: 342

PIC hours on type: 311

Last point of departure: Komati Gorge Lodge private strip

• This discussion is to promote safety and not to establish liability.

• CAA’s report contains padding and repetition, so in the interest of clarity, I have paraphrased extensively.

Next point of intended ldg: Komati Gorge Lodge

private strip

Location of accident site: Komati Gorge Lodge

private strip

Airfield Elevation: 4730’

Runway dimensions: 800m x 15m (2625’x50’)

Meteorological info: 050˚/08kts, 24˚C, Dew Pt: -5˚C, POB: 1+2

People injured: 0

People killed: 3

On the day before the accident, the pilot, who owned the aircraft, and a passenger took off from Nelspruit at approximately 1430Z. The aircraft was refuelled to capacity in Nelspruit. They flew to a private lodge 24km north-east of Carolina. They landed at approximately 1515Z.

The next day, at approximately 1025Z, the pilot and two passengers boarded the aircraft to conduct a short scenic flight in the area and land back at the lodge.

A witness, a guest at the lodge, saw the aircraft just after takeoff. He estimated its height at that point to be 30 feet above ground. He confirmed that he could hear the sound of the engine running, however, it sounded as though the engine was straining. He felt it was having difficulty maintaining height. Thereafter, the aircraft turned right and he heard a loud bang and saw smoke coming from the aircraft.

According to the second witness, a security guard working for the lodge, he heard the aircraft engine making an unusual noise, followed by a bang. He also noticed smoke and telephoned the lodge reception to notify

them of what he had heard. He also notified the neighbour (next door to the lodge) who also confirmed that he had heard a loud noise.

The aircraft was certified to use 100 LL grade aviation gasoline (AVGAS). It was fitted with standard tanks of which the total capacity is 61 gal / 230.91 litres.

The aircraft was refuelled to capacity at Nelspruit Airport. At approximately 1430Z, it departed Nelspruit Airport for the private lodge. The distance from Nelspruit Airport to the lodge is approximately 42 nautical miles with the estimated flight time of 45 minutes. The 45-minute flight would burn approximately 6 gal / 22.7 litres of fuel. Therefore, the total of 56 gal / 211.98 litres of usable fuel minus the 6 gal / 22.7 litres burned = 50 gal / 189.28 litres of usable fuel remaining on-board when landing at the lodge.

Note: There are no aircraft refuelling facilities available at the lodge airstrip. This is possibly the reason why the pilot decided to carry two extra jerry cans of fuel on-board the aircraft. Each of the two jerry cans carried 25 litres of fuel. No evidence was found of the aircraft being refuelled at the private lodge prior to the flight. This suggests that the aircraft took-off with a total quantity of 189.28 litres of usable fuel in the tanks and with two 25-litre jerry cans of fuel on-board.

The weight at takeoff was calculated as 2938 lbs which means it was 12 lbs below the maximum allowable takeoff weight of 2950 lbs.

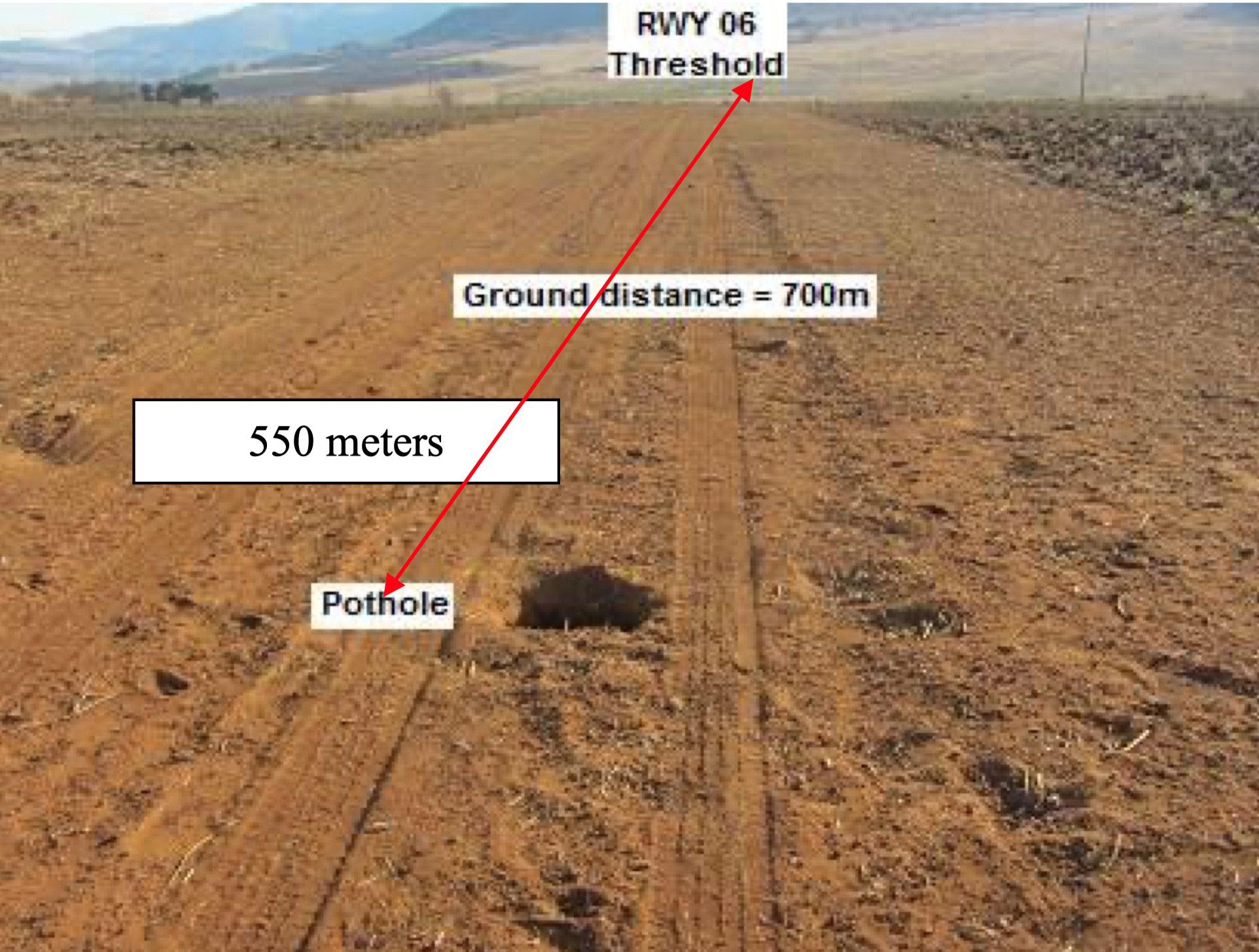

The airstrip had been constructed approximately a month before the accident. The surface was uneven and was topped with soft soil.

A substantial pothole was found on the centreline, 550m from the threshold of runway 06.

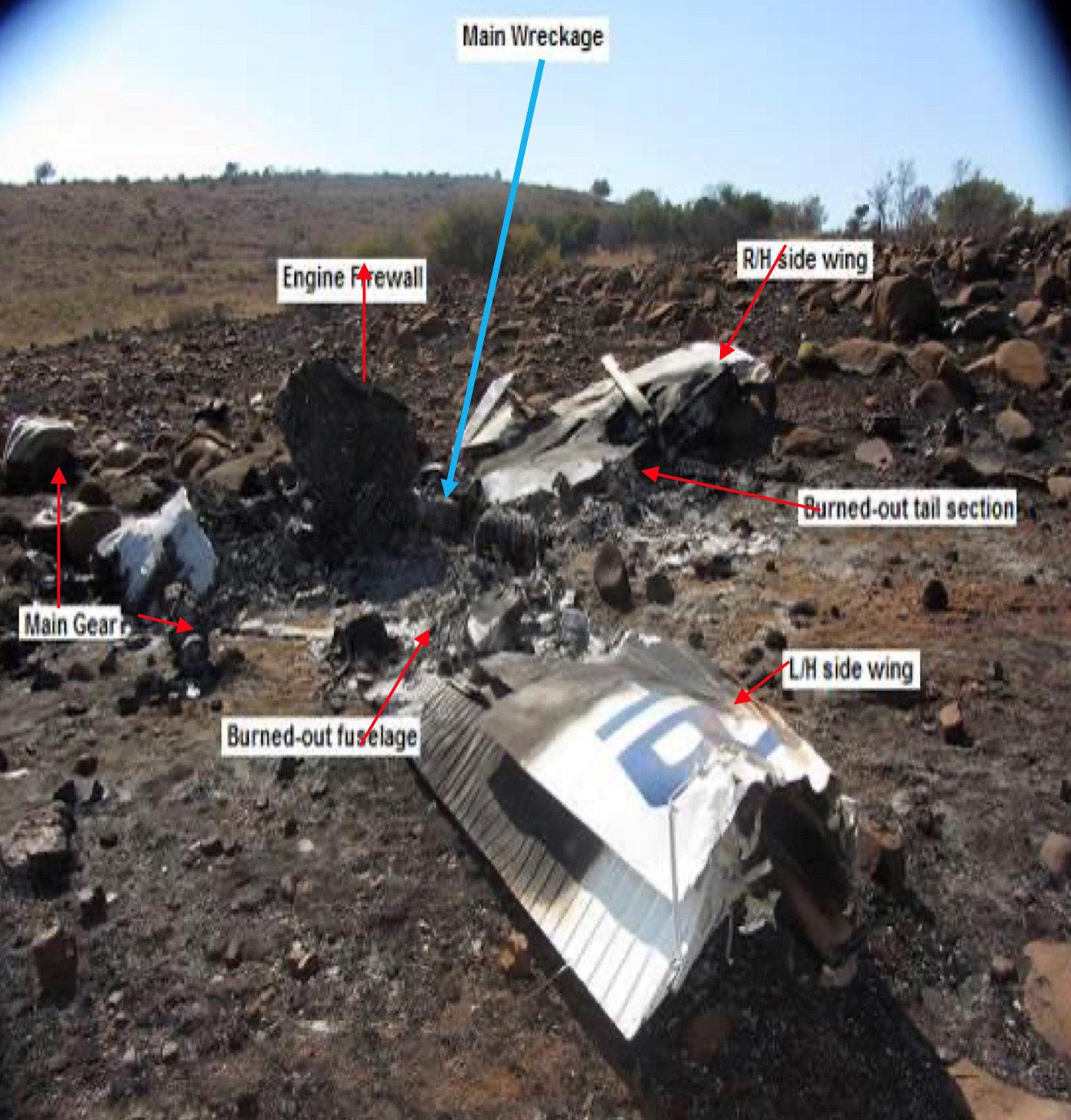

The wreckage distribution path was almost at 90° from the take-off direction. The right wing tip impacted the ground first and separated from the wing; it was located 29m from the main wreckage.

As the right wing impacted the ground, the aircraft rolled to the right and became inverted.

The propeller impacted the ground 10m from the initial point of impact. The propeller assembly had separated from the fuselage on impact and came to rest 17m from the first point of impact and to the right of the wreckage distribution path. The propeller showed evidence of rotation on impact.

The six attachment bolts on the propeller assembly were ripped out and the threads on these bolts were smooth.

The fuel tanks in both wings ruptured and the wreckage was consumed by fire.

It was not possible to determine the flap settings.

The POH says

1. Wing Flaps -- 0° - 20°.

2. Carburettor Heat -- COLD.

3. Power -- FULL THROTTLE and 2400 RPM.

4. Elevator Control -- LIFT NOSE WHEEL at 50 KIAS.

5. Climb Speed -- 70 KIAS (flaps 20°). 80 KIAS (flaps UP).

1. Wing Flaps -- 20°.

2. Carburettor Heat -- COLD.

3. Brakes -- APPLY.

4. Power -- FULL THROTTLE and 2400 RPM.

5. Brakes -- RELEASE.

6. Elevator Control -- MAINTAIN SLIGHTLY TAIL LOW ATTITUDE.

7. Climb Speed -- 57 KIAS (until all obstacles are cleared).

8. Wing Flaps -- RETRACT slowly after reaching 70 KIAS.

SOFT FIELD TAKEOFFS are performed with 20° of flaps are achieved by lifting the airplane off the ground as soon as practical in a slightly tail-low attitude. If no obstacles are ahead, the airplane should be levelled off immediately to accelerate to a safer climb speed

Note: The procedures for a soft field take-off and a short field take-off are similar in that the flap settings are the same and the aircraft is lifted off the ground as soon as practical.

The mixture should be leaned for takeoff from elevations greater than 5000ft to ensure maximum power.

The runway was 2624 ft long and the graphs show the distance required is 2459ft, a difference of just 167ft. However it’s not known where the takeoff run started. It’s likely that the pilot rotated too early without sufficient speed to climb, causing the aircraft to stall shortly after lift-off.

The POH states that runway conditions are calculated on level, dry, paved runways. The soft earth would have substantially decreased the aircraft’s ability to accelerate.

Probable cause:

The investigation could not find a definitive cause of the accident; however, it is likely that the aircraft’s performance was diminished by density altitude and/or the take-off configuration was incorrect, which would have caused the aircraft to stall shortly after takeoff.

The likely cause of the accident is that the aircraft was poorly configured, taking into account the density altitude and the effect on performance of the aircraft, which led to a stall shortly after takeoff.

I nearly skipped past this one because it looked boring – same old, same old. And then it sank in that this is the very reason it happened – and keeps on happening.

There is no one big red flag that would say to me ‘Woa! this flight looks bloody dangerous – I wouldn’t fly in the back of that aircraft’. Nope, but if I started scratching around a bit, I would find several things that were just a bit too marginal.

Things that we have all accepted from time to time and got away with.

Perhaps the most serious was the soft surface. But how are do you evaluate that in terms of takeoff distance? Sure there’s a general rule that says add 15% to the book figure. But that’s just a blind guess. It’s a very rough rule-of-thumb that is meant to apply to soggy ground, deep sand, long grass and so on. But, how soggy? how deep? and how long? There are no numerical answers.

cause one to suck in one’s breath and wrinkle the brow. And that’s what makes this accident so important.

casual

It’s shouting at me that in fact every one of these little flags should be a deal breaker. We know that one or more combined to kill three people and throw many other lives off track.

Then there’s a figure for the gross weight. We simply don’t know the gross weight within a couple of hundred pounds. No one was sure whether there was any luggage on board – the fire was too destructive to leave accurate evidence.

And how about the two jerry-cans of fuel in the back. Really not a good idea in the cabin because of the weight, the fire hazard and the question of how well they were tied down.

And technically the pilot was unlicensed – his medical had expired three weeks earlier. Did his disrespect for the law point towards a generally casual attitude towards safety?

And did he lean out for the takeoff? We don’t know, but at a density altitude of over 7000 feet he certainly should have done – it makes a hell of a difference to the power. But nothing different would show on the manifold pressure or the revs.

And the pothole in the runway. Was the pilot aware of it? And if so, was he planning to simply steer round it?

None of these points is a deal-breaker. But they do

In a way it relates to last month’s discussion on the eroding of safety margins. Our tendency to justify lower standard because they have not caused any trouble so far.

Beware when everything seems almost okay, it only takes one of them to slip over the line and bring down the whole pack cards.

j

The security services make a basic altitude error for the no-fly zone over the BRICS summit.

A meme after Russia's lunar lander crashed.

Only in Africa - boots to keep the tyres safe from wild animals.

This Spring, make sure you have the Sling that inspires your adventure.

THREE OF THESE REGISTRATIONS of new aircraft are Cessna C208 Caravan EXs for Federal Airlines. Federal have purchased a total of six new Caravans, of which these were the first three delivered. Aftrer a long ferry flight they arrived here in the first week of July. The other three arrived on 18 July 2023. This is the biggest single order and delivery for Cessna Caravans we have seen in this country. Federal Airlines will be using these on their flights to the various luxury game lodges that they service.

A Bombardier BD700-1A10 Global Express ZS-BPG taken up the registration once used by an HS125 which was exported to India in 2003.

Cemair have registered another Canadair CL600-2B19 ZS-CMJ. This one is a 2004 model and it takes up the registration once used by a Beech 1900 which now operates in Mauritius. There’s a new ATR72 for Solenta as well.

FlySafair have leased another Boeing 737-

800 from Ethiopian Airways. This one is now ZS-FGY and uses the registration of Cherokee 6 that was exported in 1988.

Amongst the other TCAs there is a Falcon 20, ZS-FLC, which arrived here in February 2023 and is now finally registered.

Showing the continued strength in the agricultural sector there is a Thrush Commander and an Air Tractor on the register. A Beech F33A Bonanza returns from Kenya, a Thunder & Colt Hot Air Balloon and a Pilatus PC12 from Botswana.

In contrast, the number of aircraft registered in the NTCA section this month is just six. Notably, there is a Graham Lee Nieuport 11 WW1 replica registered as well as an ex-Netherlands AF Allouette III, two new Sling 4 TSis, an RV7 and a Savanah S.

The number of drones registered just keeps getting larger, with another sixty-nine added this month and fourteen deleted.

This month there are sixteen new type certified aircraft (TCA) registrations – this is the most in a very long time.

the biggest single order

ABOVE: Imported from the Netherlands - A-275 is an Allouette III ex-Netherlands Air force, now ZU-RIK.

BELOW: A rare Garret powered King Air - N136MB is a Beech Be100 now ZS-JVR.

BELOW BOTTOM: An unique new homebuilt - the Graham Lee Nieuport 11.

ABOVE: ZS-MOX is a C152 exported to Uruguay. Photo Shane Swart.

BELOW: ZS-NYE is a King Air Be E90 exported to the USA.

BELOW BOTTOM: Another addition for Solenta - F-GRPX ATR 72 now ZS-XZR.

ABOVE: ZS-COH is a PC12 previously exported to Botswana, now re-registered as ZS-TAL.

BELOW: ZS-JSM is a Jetstream J41 exported to Zambia.

BELOW BOTTOM: The Safair fleet continues to grow - ex Ethiopian ET-AOA Boeing 737-800 is now ZS-FGY for Fly Safair.

is now

As a pleasant change, only five aircraft have been exported this month. There is a Jetstream J4101 exported to Zambia, and I suspect this one’s been operating outside the country for a long while as I’ve never seen it. There’s also a Cessna 152 exported to Uruguay. Two aircraft have gone to the USA. An Airbus AS332 C1 Super Puma has been registered in Switzerland.

The AERO Africa trade show at Wonderboom Airport was quite successful and I look forward to attending again next year. j

Through

The picturesque town of Maçon, France, served as the backdrop for this year’s World Rally Flying Competition.

FROM 29 JULY TO 5 AUGUST, aviation enthusiasts and competitors gathered to witness an exhilarating showcase of skill and precision. With participation from eleven countries and forty-five teams, including four teams from South Africa, this event promised the highest level of intense competition.

Ahead of the official start, Team SA displayed their dedication by arriving in France a week early for rigorous training. The anticipation peaked on 31 July, the first day of the competition, as the skies came alive with the energy of flying prowess.

In a true show of technological advancement, live tracking allowed enthusiasts from around the world to follow the action online.

The spirit of competition was briefly dampened when an official fell ill the following day, leading to the cancellation of flying activities.

Dominating the leaderboard were two Czech teams in first and second place, while the host country, France, claimed a respectable third. Team SA’s performance on the opening day ranged from 14th to 39th place, a testament to the diverse challenges of the event.

Undeterred, the competitors resumed the challenge on 2 August to be met with a difficult route and unpredictable wind. The Czech duo, Petr Jonàś, and Marek Velát, maintained their dominance by clinching the top spot again, with a Polish team securing second place and a French team placing third. For Team SA, the journey was marked with tenacity, as they secured positions in the range of 27th to 40th place.

As the event climaxed on the third and final day, the Polish team showed their mettle, claiming both first and second positions. The French team, while not clinching top spot, retained their third-place position with admirable finesse. Team SA’s placements ranged from 33rd to 40th, reflecting their unyielding spirit in the face of fierce competition.

Despite Poland’s late comeback, Czech duo, Petr Jonàś and Marek Velát, clinched the coveted first place, followed by two French teams in the second and third positions.

Amidst the mix of triumphs and challenges, South Africa found a glimmer of success. Steve van der Merwe and Alewyn Burger earned third place in the Landings category, serving as a testament to the perseverance and skill that required to compete in this top level exhilarating event. j

Fuel Prices as at 28/07/2023

Prices include VAT but exclude any service fees

Fuel Prices as at 29/08/2023

Prices include VAT but exclude any service fees

FOR THOSE AVIATION newbies who may be reading this, but have never heard of Oshkosh, it is the biggest airshow in the world. Held in Wisconsin, USA, it is on every passionate aviator’s bucket list, as it has been on mine for many years.

I’ve never met a pilot who’s returned from this spectacle disappointed. It covers every aspect of aviation, from exhibits showcasing a variety of home-builds to workshops on how to build your own aeroplane, there’s something for everyone that can leave you giddy with choice.

As is tradition amongst the South Africans, my home for the 8 days was in ‘Plakkerfontein’, the camp run by Neil and Carolyn Bowden. Neil set up the camp twentyodd years ago and it has become an institution.

As our bus from Chicago O’Hare pulled up at the camp, the red and blue lights which festoon the pub glowed invitingly in the stormy

I had the great privilege of going to Oshkosh this year to represent SA Flyer.

A small part of the 150 strong South African contingent.

darkness. The cheerful garden surrounding the entrance to the camp leads to a large marquee which sheltered us from the rain. In the storm a swing rocked under a large tree; its dense green canopy would serve as a respite from the relentless heat over the coming days.

A laager of caravans formed a semi-circle around 106 green dome tents, each labelled with its occupant’s name, arranged in neat rows of 10.

We waited until the rain dissipated before collecting sleeping bags and blankets.

I unpacked my kit, made up my bed and headed to the communal ablutions. After 36 gruelling hours in planes and buses, the warm shower was an elixir for my weary body.

Following a light dinner, I made a bee-line for my stretcher, looking forward to sleeping horizontally for a change.

The following morning, I was awakened by the general bustle of the campsite. I obtained my

A herd of Canards grazing peacefully.

fix of caffeine from the Red Barn and headed off to the media briefing area in the showgrounds.

My biggest challenge was trying to decide which talks to attend; more than 1,400 workshops, forums and presentations were on the agenda for the week.

Later that day I weaved my way through the thousandplus home-built aircraft that had flown in and headed for the flight line to watch the daily aerobatic displays.

The temperature was north of 35 deg C with the humidity above 70%, so I sought respite under the wing of Greg Peck’s restored 1955 150HP Piper Pacer N3622P. Like many of the fly-in visitors, Greg had set up camp next to his plane.

Airport in Oshkosh, a total of 556 NM which took him 8 hours at an average cruising speed of 110KT.

This was his first long cross-country flight. With only 300 total flying hours, it was a brave and adventurous thing to do, and Greg was bursting with pride. Rightly so, as anyone who has ever watched the landings at Oshkosh would know just how intimidating it is to fly in.

More than 10,000 aircraft flew into Oshkosh. There were 21, 883 aircraft operations in the 11-day period, which is an average of approximately 148 takeoffs/landings per hour.

He had flown the PA-22-150 all the way from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania to Wittman Regional

The next morning, I attended the media talk on the Super Guppy at the Boeing Plaza. With its bulbous fuselage and protruding ‘eyes’ this oddlooking aircraft lives up to its fish namesake. The Super Guppy was built to transport

components for NASA’s space programs, including spacecraft, rockets, and other critical hardware. It is an extensively modified version of the Boeing 377 Stratocruiser, with significant modifications to its fuselage to accommodate bulky payloads.

That afternoon I was back at the air show.

Skip Stewart took his highly modified Pitts S-2S biplane, ‘Prometheus’, through its paces, followed by Susan Dacy in her iconic Boeing Stearman biplane ‘Big Red’. Their performances included a mix of loops, rolls, spins, and other jaw-dropping manoeuvres.

Red Bull Air Race legend Michael Goulian, flying his Extra 330SC, took the air show performance to an even higher level of extreme aerobatics. The 330HP Extra tumbled and rotated at awe-inspiring rates in almost every attitude, showcasing the limits of both the pilot and the aircraft, leaving the spectators in awe.

The jet blast of a Pratt & Whitney F119-PW-100 could be heard way before the F-22 Raptor came into view. In an ear-splitting roar, the jet fighter thundered overhead. The air seemed literally bent out of shape as the Raptor approached the speed of sound. Air in front of the jet cannot move out of the way fast enough, so it compresses into a region known as the “shock cone”.

I watched transfixed as the Raptor climbed vertically at a rate of 60,000 fpm, in a blink of an eye becoming a mere speck in the sky. As I gazed into the glow of the disappearing afterburners, I pinched myself for the umpteenth time that day. What an amazing honour it was to be standing mere metres away from these incredible pilots and machines.

The next day, David Clarke’s in hand, I headed to the ultralight aircraft. I was to fly in a Bat Hawk, with our very own Sean Cronin, who was helping the Saitowitz family (who relocated to Los Angeles from South Africa) to promote and

sell this capable South African-built rag and tube microlight.

I cannot overstate the significance of getting in the air at Oshkosh, it’s a privilege that very few get to enjoy and here I was on my way to experience this grand spectacle from above.

For the first few days of the show the sky had been grey with the haze from the Canadian bushfires. But today it dissipated to reveal a cerulean blue sky. The birds were tweeting, and a slight breeze ruffled my hair. It was a perfect day.

I was led to the Eagle’s Nest tower where I met the managers of the field. I was in my familiar happy place surrounded by the collective buzz of Rotax engines and from this vantage point I had a bird’s eye view.

After signing the indemnity form, I slid down into the right seat next to Sean. We were airborne

in a few metres and levelled out at 300 ft AGL, which is the designated circuit height. (The Americans call it the pattern).

I had been amazed by the vast scale of the airshow on the ground; but nothing could prepare me for the incredible spectacle laid out below me.

The morning sun glinted off thousands of aeroplanes: caravans and Recreational Vehicles (RV’s). The emerald landscape slid past below us, periodically dotted with concrete grain silos, hinting at the farming nature of Oshkosh.

Dams and rivers glittered like strewn jewels, and a fresh breeze poured into the cockpit, providing a temporary reprieve from the oppressive heat.

I am due for a conversion onto the Bat Hawk, and Sean demonstrated its versatility. He deftly guided the plane around the aircraft on the ground (flying over parked aircraft is strictly

prohibited) and over the power lines and street poles to line up with the runway.

After landing, but still on cloud nine, I walked around the exhibition area and chatted to the international sales director of the Bush Cat, ex-South African Mike Gill, about the success of this proudly South African brand which has been in the USA for the past 12 years. Based out of Wonderlake Illinois’ Galt airport, Bush Cat offers fully assembled aeroplanes or kits for self-build.

I was back at camp early that afternoon to prepare for the legendary night show and fireworks display.

Over the years, word had spread through Camp Scholler that ‘Afrikaners is plesierig’ and Plakkerfontein has become the place to be. South Africans and their guests from all over the world were clustered around the braai, regaling one another with stories, as the delicious aroma of barbecued meat permeated the air.

Young Jesse Jeffrey, the Bowden’s grandson,

splashed around in a plastic pool while his mom Laura cradled 5-week-old baby Georgia, who is the youngest South African (possibly the youngest human) to ever attend Oshkosh.

Some folks were slouched in camping chairs whilst others lounged on bean bags sipping icecold Bud (which consensus has it, is nowhere as good as our local SAB brews).

Periodically all faces turned skywards, and the conversation was drowned out as the F-18 Hornets tore up the sky.

It was a perfectly wonderful afternoon.

Against a backdrop of a silver moon in a darkening sky, the AeroShell Aerobatic team of four North American T-6 ‘Harvards’, executed a series of carefully choreographed manoeuvres, including loops, rolls, and other aerobatics, all in perfect tight formation.

By showcasing the beauty of classic WWII aircraft and demonstrating the teamwork and

training required for precise formation flying, Team Aeroshell’s performance captivated the audience and was my favourite evening demonstration.

With its tadpole-shaped body and distinctive canard-wing configuration, a Long-EZ swirled around the sky in time to alien music. I wondered, not for the first time, if Burt Rutan was dropping acid when he designed it.

The Super Salto sailplane had me enthralled with its silent, graceful aerial ballet. Powered by the PBS TJ-100 jet engine, it is the only glider on the air show circuit capable of performing a low-level, jet-powered performance.

A de Havilland Chipmunk called GhostWriter ended the show with a bang. Originally designed as a trainer for the Royal Canadian Air Force, this 1956 Chipmunk has been specially modified for aerobatics and skywriting. As fireworks exploded in shards of multi-coloured lights, the

Chipmunk weaved between them, releasing its own stream of flares and pyrotechnics.

Mushroom cloud-like fireballs erupted from the ground in loud booms, the heat so intense that it could be felt on the opposite side of the runway.

The tempo and the frequency of the fireworks escalated, resulting in a heart-pounding climax. It was undoubtedly the best display I’d ever seen.

That evening, Plakkerfontein had its own extra-terrestrial visitations in the form of an inflatable pterodactyl, a flamingo wearing a cerise tutu, and a glowing green alien. Never a dull moment.

The following morning, I attended a talk at the Rotax stand on the new 916iS. With a service ceiling of 23,000 ft and 160HP, it is impressive, but comes at an even more impressive price tag of R1 million.

I wouldn’t change a thing

A yellow and white RV-9 N179RV, sporting a 916iS, was on display, highlighting how far the original Rotax design had progressed since its early days when it was developed for free wheel bicycle hubs. The first aircraft engines were manufactured in 1975 and the rest, as they say, is history.

Whilst at the presentation, I met John Tiley, from Canterbury in the U.K, who had purchased a 915iS to put in his Sling TSi. I was intrigued as to why, of all the available kit planes on the market, John had chosen the South African brand.

He explained that he wanted something modern and comfortable with sufficient range and interior space to take his grandchildren on holiday. He also mentioned (several times) what great service he’d received from the Sling agents in the UK.

Inspired by his story, my next port of call was Sling where I met up with ex-South African Jean d’Assonville. Jean is the USA representative for Sling who currently resides in the Bahamas. A far cry from 20 years ago when we used to fly paragliders at Hartbeespoort Dam together.

We chatted about the High Wing and how Sling is replacing the Rotax 915iS with the new Rotax 916iS, which should provide the HW with an extra edge.

A highlight that afternoon was the sixthgeneration air taxi, the Wisk, which took a vertical leap into the air. The world’s first fourpassenger, autonomous, electric vertical takeoff, and landing (eVTOL) air taxi flies itself while being monitored from the ground. Each flight is monitored (not remotely piloted) by a groundbased supervisor that can intervene by sending new commands that the aircraft then executes autonomously.

Back in SA, it would be repurposed to fit 10 people and a small goat. Kidding aside, the skies above Jo’burg would be complete bedlam.

As below, so above; a frightening thought!

A record number of 2,372 attendees from 93 countries outside the U.S. had registered at the International Visitors Tent.

The EAA international parade on Friday was dominated by 150 South Africans who were led out by patriarch Karl Jensen. The sun was bright, and the mood was jovial as we wound our way through the streets behind the rainbow flag.

At 16h00 a warning was issued regarding the possibility of severe storms and hail that evening. Hundreds of aircraft owners rushed to fly out of Wittman before their planes got damaged. The queue on the taxiway was insane, ATC was letting groups of planes depart amongst planes that were arriving. Some people waited on the taxiway for over an hour before getting airborne.

At 22h00 strong winds whipped through the camp, snatching at the tent pegs. The storm unleashed its full fury over Oshkosh. The rain

lashed against my tent, soaking through the flimsy material within minutes. Fortunately, the hail never materialized, and the storm exhausted itself by midnight.

My things were mostly dry thanks to the tarpaulin Warren had lent me, but the floor of the tent was under water.

According to Neil, camping in a storm is the ultimate Oshkosh baptism.

The next morning dawned, revealing a pristine sky. I had the privilege of being shown around the Warbirds area by aircraft guru Karl Jensen