pilatus-aircraft.com

pilatus-aircraft.com

The fracas over FlySafair’s offshore ownership is becoming increasingly heated. Competitors Airlink and Lift have laid a complaint to both the Domestic and International Air Services Licencing Councils. At time of writing the Councils have not yet ruled - or in the Domestic Council’s case –even considered the matter.

THE IMBROGLIO has been fought out in the general media with sensational headlines. In my comments to the general media, I have tried hard to assure FlySafair passengers that flights are not likely to be cancelled, or the airline grounded.

Both Airlink’s Rodger Foster and Lift’s Gidon Novick have denied that they in fact ever called for FlySafair’s actual grounding, despite headlines to that effect.

The detailed financial submissions by the FlySafair holding company ASL, (which is based in Ireland) do not make pretty reading. Despite its protestations, FlySafair does, once again, seem to be on the wrong side of the law.

The question that engages many analysts is whether the law is reasonable. Many countries do not have restrictions on foreign ownership of airlines – or if they do, it’s around a 50% limit, and not South Africa’s very restrictive 25%.

I support the view that in a properly liberalised airline environment there should not be restrictions on non-resident ownership, provided the airline is properly registered in South Africa.

The free-marketers chief complaint against the 25% maximum limit is that it makes it harder for the airlines to raise capital, especially given the hefty political discount that erodes the SA Rand’s value.

But the rules are the rules – and FlySafair seems to have a long-running cavalier attitude to them. In the 2012 judgement against FlySafair for its non-resident shareholding, the judge was scathing, accusing it of evasion of the law (in fraudem legis) and misleading the Licencing Councils.

And now here we are again. Kirby Gordon, Safair’s Chief Marketing Officer, has been reported as saying, “instead of trying to ground the airline … their rivals should ‘stop whinging and up their game.”

However, what is equally hard to comprehend is why Safair appears to be so doggedly clinging to its evidently out of bounds ownership. After the fight 12 years ago, FlySafair established the Safair Investment Trust, registered in South Africa, to hold almost 50% of Safair’s shares. It also created a 25% employee share ownership scheme, which reduced ASL to the required 25% share.

So again, it should be simple enough to transfer a 75% shareholding to a trust with South African resident control. Safair’s reluctance seems to add weight to their competitors’ claims that it does indeed give them an illegal advantage.

The complainants argue that the current laws are not clear, especially the International Council’s requirement for an undefined ‘substantial’ local ownership. If nothing else, it is hoped that the resolution of this unseemly spat over arcane laws will bring much needed clarity to both Licensing Councils’ requirements.

j

SALES MANAGER

Howard Long sales@saflyermag.co.za 076 499 6358

TRAFFIC

Howard Long traffic.admin@saflyermag.co.za

ACCOUNTS

Angelique Joubert accounts@saflyermag.co.za

EDITOR

Guy Leitch guy@saflyermag.co.za

PUBLISHER

Guy Leitch guy@saflyermag.co.za

PRODUCTION & LAYOUT

Patrick Tillman www.imagenuity.co.za design@saflyermag.co.za

CONTRIBUTORS

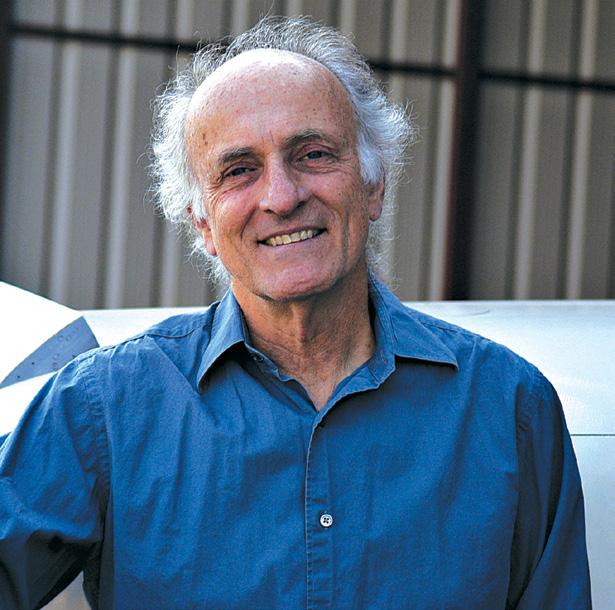

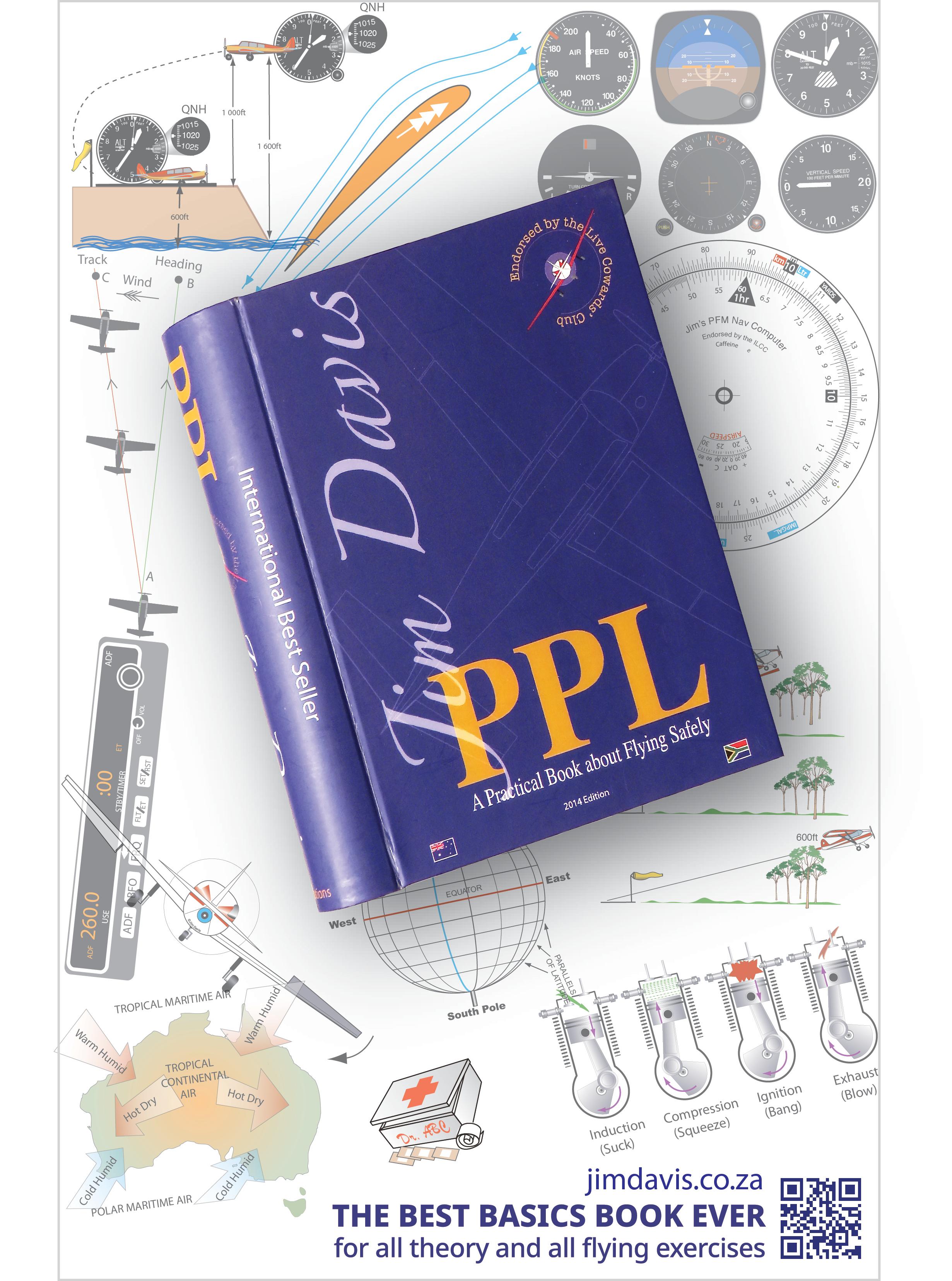

Jim Davis

Peter Garrison

Hugh Pryor

CONTRIBUTORS CONTINUED

John Bassi

Morne Booij-Liewes

Laura McDermid

Darren Olivier

Jeffrey Kempston

ILLUSTRATIONS

Darren Edward O'Neil

Joe Pieterse

WEB MASTER

Emily Kinnear © SA FLYER 2023. All rights reserved worldwide. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronically, mechanically, photocopied, recorded or otherwise without the express permission of the copyright holders.

To get a striking air to air image such as this, many different skills have to come together. The key is good formation pilots. In this instance well-known pilot Derek Hopkins was a passenger to Pierre Gouws in an RV-8 and Daan Conradie was formatting his RV-8 on Pierre’s lead. Derek is a big guy, and just using a clunky SLR camera in the tight space under the canopy of an inverted RV-8 is a challenge.

The image was taken by Derek using his Canon 700D with exposure of f6.3 at 1/160th second at ISO 100. Noteworthy is that the lens is a wide angle 29mm, which shows how tight the formation was as it went over the top of the loop.

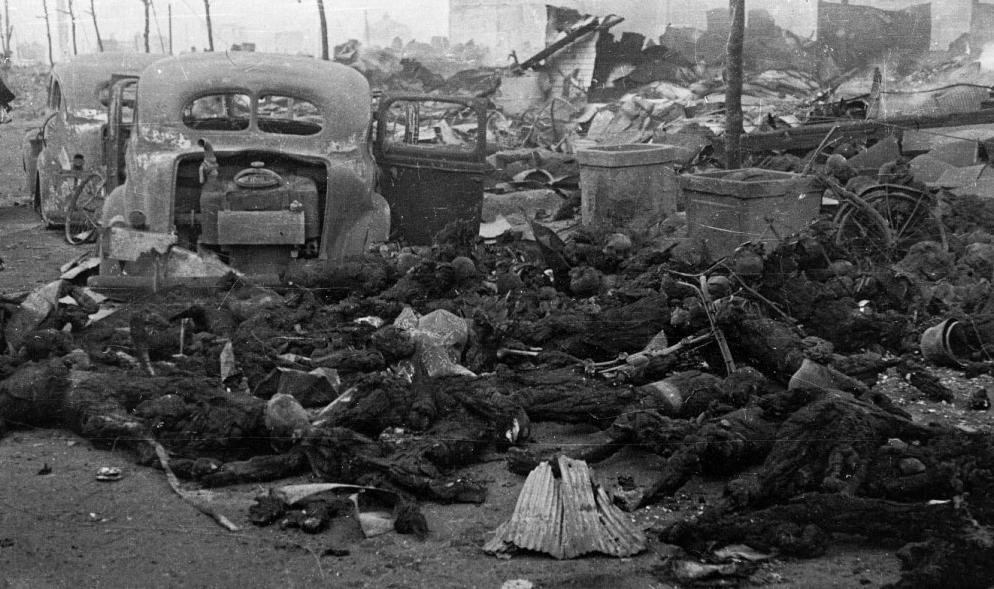

In modern warfare it’s not the soldiers who die – it’s the civilians. One of the best examples of this is carpet bombing.

IN THE BAD OLD DAYS, soldiers used to line up and face the enemy, expecting to be attacked man to man, on foot, or with horses, and later, to mow each other down with machine guns. The soldiers were maimed, bled and died by their thousands on behalf of civilians.

World War 2 changed that as it was the first major war where more civilians died than soldiers. This continues today – at risk of stirring up a hornets’ nest – I reckon that the Israel-Hamas war is primarily a massive public relations stunt by Hamas to make their citizens unwilling martyrs and make Israel a pariah. At time of writing (8 April 2024), wiki says that over 34,000 civilians (33,091 Palestinian and 1,410 Israelis) have been killed. In stark contrast, Hamas claims to have lost 6,000 ‘fighters’ while the IDF claims up to 12,000 Hamas combatants killed. The point is, civilian casualties are three to six times higher than soldiers.

crews who, contrary to claims, indulged in area, and not precision, bombing. Only the leader aimed his bombs, the others released theirs when they saw the leader’s bombs drop.

The Oppenheimer movie is about Dr Robert Oppenheimer, who headed the Manhattan project, whose two atomic bombs killed 129,000 – 200,000 civilians – and ‘just’ 10,000 soldiers. The atomic bombs had the desired effect because the cost in human life was just too much, even for the Japanese Emperor.

is not just tactical – its moral

Which raises the question of whether bombing with conventional high explosive bombs was ever really a useful strategy in the WW2. Hundreds of thousands of civilians died on the ground in horrors such as the RAF’s Dreden firestorm and the USAAF’s Operation Meetinghouse Tokyo raid.

The reason I venture into this minefield is that I recently watched the Oppenheimer movie, and am sporadically watching the Netflix series, Masters of the Air, which is a semi-serious attempt to dramatize USAAF B-17 bomber

At the start of World War II, aerial bombing meant total destruction. The Luftwaffe’s London Blitz was designed to demoralise the British into submission. England’s response was Arthur ‘Bomber’ Harris, who many consider a

Gaza strip ruins were not caused by a nucear bomb.

psychopath, and who would probably have been executed as a war criminal if the Germans had won. Harris was one of the chief architects of the British tactic of what he called ‘morale bombing’. Despite the heroics of Londoners during the Blitz, Harris also believed that reducing German cities to rubble and incinerating civilians would force surrender.

In contrast, the Americans tried precision bombing under General Haywood Hansell, who believed their much-vaunted Norden bombsight really could drop a bomb down a ‘pickle barrel’. Hansell’s argument was that civilian casualties could be minimised if, instead of carpet bombing cities, you could surgically take out key infrastructure such as ball bearing and aircraft factories.

A few years ago our columnist Darren Olivier wrote, “In World War II there was a debate between the advocates of precision bombing and area bombing. Some, especially the ‘Bomber Mafia’ of the US Army Air Force, believed that, with the introduction of the Norden bombsight, it was finally possible for bombers to hit targets such as factories, rail yards, bridges, and other strategic infrastructure with pinpoint accuracy, therefore avoiding unnecessary

civilian deaths and, as they claimed, shortening the war by picking out and destroying Germany and Japan’s key infrastructure.

“Their opponents, mostly in the Royal Air Force, believed that precision bombing was not yet possible with the technology available at the time and that less discriminate area bombing would have a greater effect, both by destroying large amounts of industry at a time, and demoralising German and Japanese civilians.

“Ultimately neither was entirely correct. The advocates of area bombing were right about precision bombing being unfeasible: The Norden bombsight was overrated, and USAAF aircraft never achieved anything close to the level of accuracy needed to make the approach effective. As a result, even the USAAF switched to area bombing later in the war. But the British were wrong about area bombing working to demoralise civilians, proving conclusively that wars could not be won by terrorising populations from the air.”

Malcolm Gladwell has written a book about ‘The Bomber Mafia’. He keeps the readers attention by presenting two protagonists: General Haywood Hansell and Curtis LeMay.

As a strong proponent of precision bombing, Hansell justified it, both in terms of effectiveness and morality. In contrast, LeMay was the ‘get it done at any cost’ action man who did what had to be done to accomplish the larger mission.

In Gladwell’s somewhat romantic view, the story is about innovators and disrupters. His heroes are versions of Elon Musk or Steve Jobs — disruptors who brought a unique perspective and, through determination and insight, pursued a dream.

For Gladwell, the difference in leadership and operational approach is not just tactical – it’s moral. The precision bombing proponents were the good guys, trying to avoid the mass slaughter of earlier wars.

In World War 1, which was the ‘war to end all wars,’ the British, French and Russians lost more than five million troops and the Germans lost over four million. What mortality statistics fail to tell us is the 21 million who were wounded: many of whom would never make a full recovery, having lost limbs or been blinded. Compared to the soldiers deaths, it is estimated that there were barely one million civilian deaths,

perhaps the last time more soldiers than civilians died in a war.

For those with a conscience, for World War 2 there had to be a better way. Hansell was the panacea, with his belief that precision bombing from 40,000 feet really can take out key ‘choke points’ and win wars.

However, precision bombing was never as accurate as was hoped. Many bombers missed their targets completely, either because it was clouded over, or in Japan, because jet streams blew the bombs off target.

Gladwell considers the morality of carpet bombing and compares, not just the tactics of area vs precision bombing, but also the morality of the leaders, particularly Haywood Hansell to Bomber Harris and Curtis LeMay. Gladwell quotes Tami Biddle, a professor at the U.S. Army War College, who says, “I think there’s a strong moral component to all this, a desire to find a way to fight a war that is clean and that is not going to tarnish the American reputation as a moral nation, a nation of ideas and ideology and commitment to individual rights and respect for human beings.”

Not precision bombing - B-17s release their bomb loads during a daylight raid over Betzdorf, Germany, in 1945.

And so the argument is not just one of which is more effective: carpet bombing or precision bombing. Like the Israel-Hamas war, it is about the moral high ground. It is not about technology, whether it be the Norden bombsight or the Manhattan Project’s atomic bombs. Rather, it is a story about the ways in which the governments justified the wholesale killing of civilians.

As Darren Olivier says, it turns out Norden’s bombsight couldn’t provide the precision he said it would, and thus Hansell had very limited success carrying out precision bombing over Japan. Which is why he was replaced by Curtis LeMay, who used napalm bombs to burn 100,000 civilians to death in Tokyo in just one raid. Even by American estimates, more people were burned to death in a single attack, than at any other time in history.

Although he practised indiscriminate carpet bombing, LeMay’s use of area and incendiary bombing is now justified as having avoided the wholesale slaughter of military personnel and civilians that would have happened if it had been necessary to invade Japan. Estimations of the casualties that would have been incurred

if America had invaded Japan vary widely, but based on the Battle for Okinawa, it’s reckoned that if the war had continued, it would have cost America another million troops.

Supporters of area bombing therefore claim that it is the lesser of two evils, and it was not as terrible as the trenches and starvation of World War 1, or the bloody conflict of Guadalcanal and the retaking of the Pacific islands.

I reluctantly have to agree. My callous view is that the atomic bombs and firestorms from carpet bombing were indeed a military success. The ‘genocide’ created by these weapons of mass destruction have made the stakes so high that we have had ‘Pax Americana’ where no nuclear nation has dared attack another for the past 75 years.

The final analysis is bleak – if you strip away the rationalisations, air war is about the destruction of cities and the murder of civilians. It may accomplish other military goals in the process, but the wanton destruction of innocent life is its primary purpose. j guy@saflyermag.co.za

The Staggerwing was the climax, and the end, of an era.

LATE IN 1932, the newly formed Beech Aircraft Company flew its first product, a five-seat biplane with a 420-hp radial engine and fixed landing gear enclosed in huge fairings. Walter Beech gave it model number 17, since the last model built by the Travel Air company, which he had founded in 1925 with an all-star cast of Clyde Cessna and Lloyd Stearman and sold in 1929 to Curtiss-Wright, had been its 16th.

The United States was in the midst of the Great Depression, and buyers for the big biplane were hard to find. In a reckless moment Walter Beech decided to advertise that it was also available with a 690-hp Wright Cyclone engine. In fact, none had been built and flown with that engine, and the factory was actually heading in the opposite direction, developing a tamer retractable-gear version powered by a 225-hp Jacobs. But as luck would have it the offer came to the attention of Robert Fogg, the company pilot of the Goodall Worsted Company of Sanford, Maine, creators – somewhat ironically, given the geography – of the popular “Palm Beach Suit”. Goodall ordered one.

narrow-geared A-17F was claimed, somewhat implausibly, to be capable of 217 knots, but it turned out to be quite a handful to fly, and in due course Goodall sold it. It flew in a couple of transcontinental Bendix Trophy races, but with disappointing results.

In 1936 the landing gear collapsed under a heavy fuel load before the plane got into the air. On the next try, the engine quit a little short of the finish.

The definitive early production Staggerwing was the 1934 B model. It had retractable landing gear and the Jacobs engine, and achieved the sedate cruising speed of 140 knots, which was really not bad for such a big aeroplane with such a small engine. Later models got twice the power, in the form of a 450-hp Pratt & Whitney R-985. In principle doubling power should add 26 percent to speed, and indeed this version cruised near 180 knots, a gratifying instance of aviation reality conforming to theory.

Beech reinforced the empennage and stuffed the big heavy Cyclone as close to the firewall as it could go, giving the aeroplane the squashed face of a pug dog. The short-coupled,

During World War II, hundreds of Stags served as both the quaintest and the most charismatic personnel transports in the military fleet.

In 1948, having replaced the charismatic Staggerwing with the entirely different, but

equally iconic, V-tail Bonanza, Beech ceased production of its glorious but anachronistic biplane.

The Staggerwing got its nickname from the arrangement of its wings, with the lower wing 25 inches ahead of the upper. The term “stagger” refers to any difference in the longitudinal locations of a biplane’s wings.

The prevalent arrangement has always been “positive” stagger, with the upper wing farther forward, probably because during the First World War pilots found it more useful to be able to see downward than upward. (Nevertheless, the negative-stagger De Havilland DH.5 of 1916 was praised for its “first class view forward and upwards.”)

The principal requirement of a biplane, from a stability standpoint, is that the more forward of its wings stall first, so that the aeroplane naturally pitches down when stalled; this can be accomplished, regardless of the type of stagger, by adjusting either the aerofoils of the two wings or their angles of attack, or both.

The reasons for the negative stagger of the Model 17 were, I suspect, two. The one more often cited in published accounts of the aeroplane is to provide better visibility for the pilot, who would naturally be seated ahead of the CG. (In many multi-seat biplanes of the Twenties, including several Travel Air models, the pilot occupied a rear cockpit, separate from the passenger cabin, for reasons of balance.)

There is no compelling aerodynamic reason to prefer one over the other, as is apparent from the fact that the few negative-stagger biplanes that exist are not notably defective performers.

But the fact that work began on a retractablegear version so soon after the fixed-gear one went on the market hints at a different and more plausible reason. The position of the lower wing

gave the main wheels, which had to be placed well forward in a tailwheel-gear aeroplane, a place to hide. I think it pretty certain that Beech’s chief designer, Princeton-educated Ted Wells, had this requirement in mind from the start.

Wells had previously designed several biplanes for Travel Air, but nothing quite like this. The basic idea was to combine a reasonable landing speed – easily accomplished with a huge wing area of 300 square feet – and a high cruising speed, which would require a powerful engine and exceptionally low drag.

their professional involvement with bicycles influenced the Wright brothers’ approach to stability and control, Wells’ skill at streamlining owed something to his familiarity with flowing water. Wells was an avid and skilled competitive sailor; in fact he later resigned from Beech aircraft after a tiff with Walter’s wife, Olive Ann, over Wells’ frequent absences at sailing meets. It is not difficult to persuade oneself that there is some kinship between the graceful lines of the Staggerwing and those of a racing yacht.

The shape Wells produced is one of beautiful fluidity: you can visualize the air parting at the nose and coming together toward the tail in an effortlessly natural way. Perhaps, just as

The low drag of the Stag was due in part to wind tunnel research performed at NACA’s Langley Memorial Laboratory under Fred Weick, who would later design the Ercoupe, and at the Guggenheim Aeronautical Laboratory at Caltech (GALCIT).

ZS-BBC. Image Ray Watts.

The NACA contribution was the round cowling, fully enclosing the engine, that would eventually be used on practically every radial-engine aeroplane except cropdusters, which don’t care about drag. Behind the circular outlet slot at the rear edge of the cowling, the Stag’s firewall blended with a smooth curve into a windscreen so steeply raked as to be nearly flat, and from there seamlessly into the leading edge of the wing.

Although the feasibility of cantilever biplanes had been demonstrated by Fokker during World War I, Wells chose to accept the drag penalty of interplane bracing. But he made use of the thickness of the plywood-skinned Clark and, later, NACA 23000-series aerofoil to carry torsional loads, and replaced the customary N struts and multiple sets of bracing wires with a single streamlined interplane strut and a single pair of wires.

From GALCIT came the wing root fairing, which had been developed for the Northrop Alpha, a very clean all-metal low-wing cantilever monoplane of 1930 similar to the Stag in weight,

power and wing loading. The Alpha’s problem, which it shared with most low-wing aeroplanes, was flow separation, particularly in climb, in the diverging channel between the downwardsloping upper surface of the wing and the upward-sloping underside of the fuselage.

GALCIT studies produced the concave wing root fillet, extending behind the wing and blending gradually into the fuselage, that would thereafter grace many low-wing aeroplanes. The Stag’s big fillet swept upward in a gentle S-curve, extending more than halfway to the empennage and giving the aft fuselage the graceful cusped shape of a modern composite single.

Though it was stylish and fast and came at the climax of the biplane era, the Staggerwing was obsolete when it was new. Its contemporaries, like the Alpha and the Douglas DC-1, were metal cantilever monoplanes of the type that would dominate aviation for the next 70 years, leaving the Staggerwing – a nostalgic and inimitable jewel – behind. j

Henok Teferra Shawl

At the Air Finance Africa conference in Sandton held in May, Boeing’s Regional Director for Africa, Henok Teferra Shawl said;

“Boeing wants to work with Africa to enhance safety in the region.” (via journo Linden Birns).

The SAAF is not the only air force dealing with cutbacks

Yep, we are still thinking about engine food. When we started down this road, I had no idea it was going to take five times longer than any other part of the stuff instructors should bestow upon their congregations.

LET’S START WITH the story behind Joe’s cartoon – it has two serious morals. First your pupes need to know that a good earth is crucial before they touch the nozzle to the tank. The second is that if you happen to have set fire to a drum of fuel, you can either wave your arms

around and run for the hills, or you can just put your hand, or a lappie, over the hole, or put the lid on.

I always imagined it would explode until Peter’s unintentional demo showed me how wrong I was.

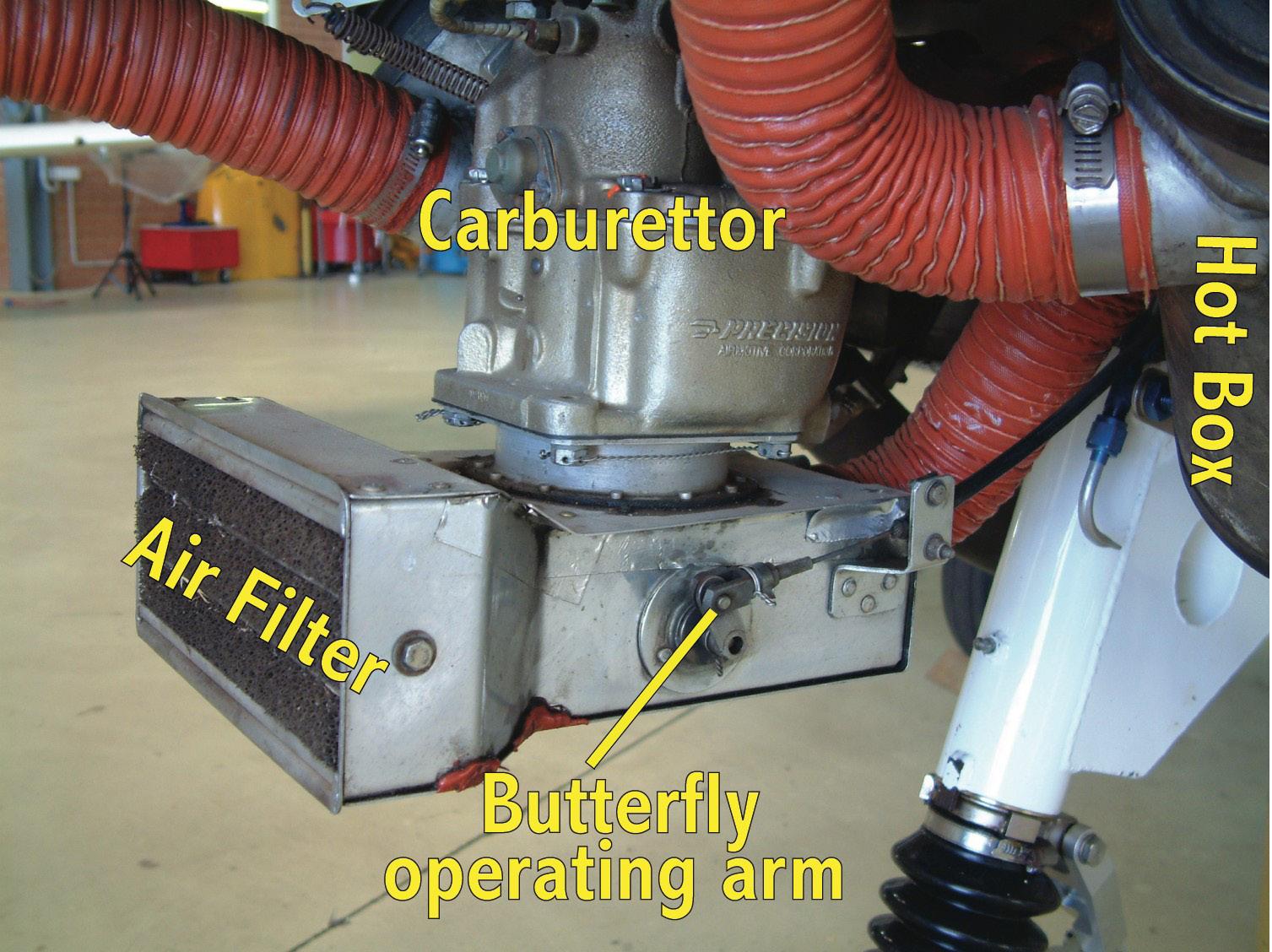

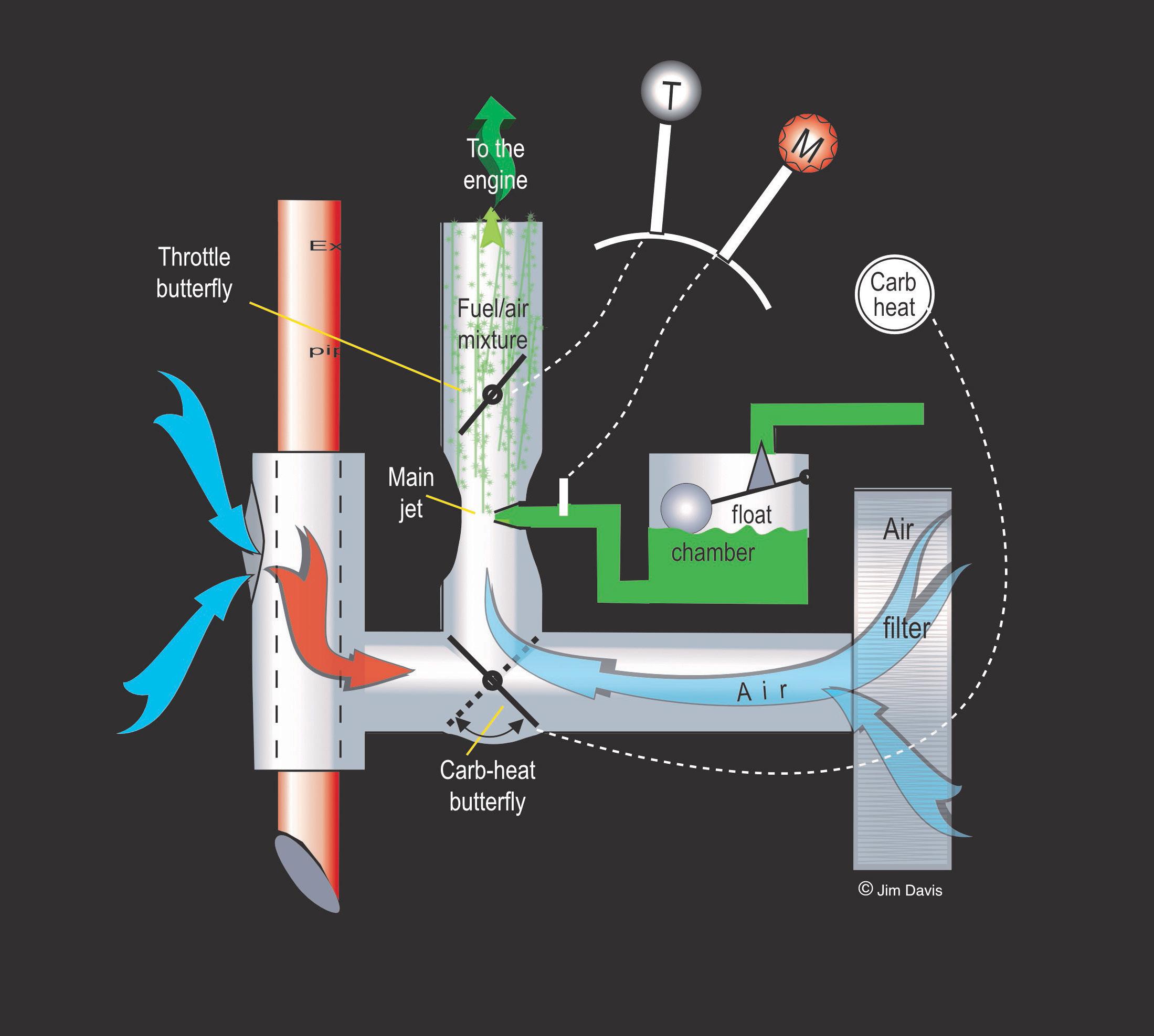

Jim's very nifty schematic of a carburettor fuel system.

Anyhow, here’s what happened.

I was between marriages and had a girlfriend, the fair Yvonne, in Salisbury, which now identifies as Harare.

My mate and student, Arthur Westworth, agreed that a dual cross-country to Salisbury and Vic Falls sounded like a brilliant way of spending a few days over the Christmas hols. We took my almost new 180 Cherokee ZS-ELK and collected Arthur’s girlfriend, Hazel, in Durban. We cleared customs at Virginia and set sail on the long leg that took us past the magnificent Drakensburg mountains, across the Limpopo and into Beit Bridge to clear customs and immigration into Rhodesia.

The officials, in their white uniforms, enjoyed the diversion from form stamping and paper signing in the office. They would spring into a Series 1 Landy, drive out to the airfield, and take their time anointing our paperwork. It was a peaceful and relaxed procedure – they were never in a hurry to get back to headquarters.

Peter Dahl, owner of Staggerwing ZS-PWD, also heard us. He flang an armful of cold Cokes into his WW2 Chev truck and clattered out to the airfield.

In those days you didn’t need to tell the guardians of the border that you were planning to drop anchor – you just beat up their shed a couple of times, and landed at Peter Dahl’s strip, just north of the river.

Peter was always fascinated by machinery and gadgets and loved fiddling with such things, He was usually very good at it, however, I viewed his latest refuelling contraption with some suspicion. He had rigged up an electric pump to transfer the fuel from the drum to the aircraft.

I didn’t like it and tried to point out that we could happily syphon the fuel since the drums were nice and high, but Peter was determined to

You need to understand what happens to the revs when you use carb heat.

demonstrate his apparatus. It sprouted red and black leads, that Peter clipped to the Chev’s battery.

At that moment, something else took my attention, and I only looked back when I heard Peter bellow “Oh f##k” from the back of his truck. My worst fears had come true. A surprisingly small fire was coming from the open mouth of the drum, and a considerably larger one enveloped the pump which I observed in mid-flight as he hurled it away.

Fortunately, we hadn’t put the nozzle in the aircraft’s tank when the conflagration broke out. So the pump and rubber pipe burned happily in the hot Messina sand, while Peter put his big leathery hand over the flaming hole in the drum.

All too soon the fun was over. Peter was unharmed and unconcerned by the near disaster. We all drank our Cokes while he muttered darkly about earthing.

The rest of the Christmas holiday was as good as it gets – 30 hours with pretty girls, blue skies and the wonders of Africa to explore.

Some may remember that Arthur was a big noise in ballooning circles and later became the boss of the Aero Club of SA. He was also a hell of a good guy. Sadly, in February 2005, Arthur was shot and killed by intruders in his home in Kyalami, while Hazel, who was then his wife was forced to look on.

Okay you lot, enough chatter – time to turn our safety focus on understanding the rest of the fuel system:

16. Electric fuel pump.

If you have a look at the beautiful diagram you will see that the electric and mechanical fuel pumps are connected in parallel. That means that if one fails or gets blocked the other can do the job just fine, thank you.

So the electric fuel pump is little more than a backup for the mechanical one that automatically pumps fuel as long as the engine is turning.

Many high-wing aircraft don’t even have an electric pump – they rely on comrade Newton’s gravity to shove the fuel from the tanks to the engine.

But of course low-wingers don’t have that going for them. This means that they need an electric pump to get the fuel to the engine before it can start.

Fuel injection engines may call for you to study the POH on how to use the electric pump during hot and cold starts. Be extremely careful with Continental fuel injected engines that have Hi and Lo positions for the electric pumps. Get this wrong on takeoff and you are likely to lose power and crash. I have reported on a number of fatal accidents with C210s and Bonanzas where the pilots used the Hi position during takeoff. Study the POH – you have been warned.

The mechanical fuel pump moves the fuel to the carburettor, or fuel injection system, so long as it’s not broken and the engine is turning.

You should test the electric pump before start to make sure it brings the pressure into the green. And once the engine is running you need to test the mechanical pump by turning the electric pump off and noting that the pressure remains in the green.

You should also use the electric pump during takeoff, landing and low flying, and any other time when a mechanical pump failure would be troublesome.

The electric pump will speed up an engine restart in flight if you run a tank dry. It normally takes between 10 and twenty seconds for the engine to come back to life – but if feels like about a week.

This statement is usually true –but not always.

Let’s have a pop-quiz to see if you have been paying attention to the diagram and the previous 500 pages on the fuel system. Ready?

List everything you can think of that could cause the engine to stop even if both pumps are in perfect working order.

Give it some thought before you look at my 20 point list, it will help to have the diagram in front of you. I’ll get you started by telling you the pipe to the pumps is either empty or it contains water, because of something you have done, or failed to do:

• The selected tank is empty because you ran it dry.

• You didn’t allow for contingencies like headwinds, incorrect leaning, getting lost and bad weather diversions.

• The fuel was stolen overnight and you didn’t do a thorough preflight.

• You trusted the fuel gauges.

• You didn’t use a dip stick.

• One of the tanks is leaking.

• A fuel drain was leaking or left open.

• The fuel was sucked out because a cap was loose, or left off.

• The ball is out of the middle, causing uneven left/right consumption figures.

• A sideslip or rolling takeoff caused unporting.

• The tank filter is blocked. Not your fault.

• The low-point filter bowl is blocked. Not your fault.

• The low point filter bowl contains water or gunk. Your fault – you should have checked.

• The tank breather is blocked.

• The cap breather is blocked.

• You selected an empty tank.

• The selector is faulty.

• The selector’s markings are missing or incorrect.

• The tanks contain water or something else.

• You are using the wrong fuel.

Now, once the fuel arrives at the engine, we have three controls – the throttle, the mixture and the carb-heat – to handle its final journey before it gets burned.

A quick reminder that the carburettor is a device, about the size of half a loaf of bread, and its job is to vaporise the fuel (mix it with air) in the ratio of about 1:15. That’s one part of fuel to fifteen parts of air, by weight.

This controls a butterfly valve which allows more or less of the fuel/air mixture to reach the cylinders. So it controls the power.

On most aircraft the throttle also operates a tiny little pump that squirts in a bit of extra fuel as you open the throttle. This is called an accelerator pump and its job is to make sure that ham-handed pilots who bang the throttle open suddenly, don’t cause the mixture to temporarily become so lean that the engine splutters, or even dies during throttle opening.

It allows us to adjust the fuel/air ratio of the mixture entering the cylinders. Remember we said earlier that this is ideally around 1:15. The reason we need to fiddle with it is because as we climb to higher altitudes the air gets ‘thinner’. And this messes with the ratio, so the 15 parts of air may become say 12 which would mean that the engine would be eating a mixture of 1:12. The same amount of fuel but less air. In other words the mixture would be too rich.

A rich mixture means the engine is less efficient – it produces less power, and it is prone to foul the spark plugs, and possibly make the engine run too cold.

On the other hand, if we make the mixture too lean – meaning insufficient fuel for the amount of air, the engine will lose power dramatically and will tend to overheat to a dangerous level, causing burned valves and detonation. Detonation is a condition in the cylinders where the fuel explodes violently instead of burning in the normal way. It can physically damage the pistons and may cause them to break, with dramatic results.

Got that?

But you wouldn’t do that would you? Or allow your pupils to, because we all know that smooth engine handling is the hallmark of a good pilot.

Perhaps the mixture control is the most abused engine control in the cockpit. Those pupils and pilots who have no mechanical aptitude will never really understand it. But everyone can learn general rules that will make sure they operate it safely.

First, what does a mixture control do? And why do we need it?

• Too rich – a loss of power.

• Too lean – a major loss of power and possible engine damage.

So here are some general rules – which are just that – they are no substitute for the POH.

1. On the ground, while idling or taxying, lean out aggressively to avoid plug fouling.

2. For max power during takeoff at altitude, lean for max revs but be on the rich side.

3. In the climb don’t lean out below 5000.

4. In the cruise only lean out if you are using 75% power or less.

5. During your descent the mixture becomes leaner and leaner as you enter denser air. Ideally you should richen it a bit every thousand feet or so, but you are likely to forget, which could mean that, when you need power, you will have none because the mixture has sneakily become too lean. If you think this can happen, then richen the mixture at the top of decent, when you reduce power, and then you have one less thing to think about.

6. If you change the power setting, even a little bit – you need to lean out again.

7. You may hear of all sorts of fancy ways of leaning out for best power or best economy or lean-of-peak. Generally they only apply to fuel injected engines fitted with special EGTs – one for each cylinder. For us ordinary people the rule is to lean out slowly until the engine just starts to run a bit rough – then richen for smooth running and then a minute amount more to be on the safe side.

Now we have yet another thoroughly misunderstood control.

What is it, why do we need it, and how does it work? Instructors, remember the What Why How rule for training?

What is it? It’s a pilot-controlled device for diverting hot air into the mouth of the carburettor.

Why would you need to do this? Because, under certain conditions, ice can form inside the carb and this will reduce or even cut off the airflow causing a reduction in power or a complete loss of power.

How do you use it? Okay here are some more general rules.

it’s almost certainly a fuel

8. I don’t trust an EGT because you never know whether it’s fitted to a rich or a lean cylinder. Yep, the mixture does vary slightly between cylinders.

9. When you have the mixture fully rich, at sea level, the engine is slightly richer than ideal, typically about 1:12. This reduces the possibility of pre-ignition or detonation, and helps with cylinder cooling

10. It’s normal to stop the engine by bringing the mixture fully aft into the ‘idle-cutoff’ position. This prevents the engine from erratic behaviour during shutdown. It also prevents fuel from diluting the oil on the cylinder walls.

11. The POH is always king.

1. If you have a fuel injected engine there’s no carburettor to ice up, so there’s no carbheat. Lucky you.

2. Never use carb-heat with full power. (a) you won’t get full power because you are using hot – less dense – air. And (b) the less dense air makes the mixture too rich. And (c) you can damage the engine because if may cause detonation.

3. Always clear any possibility of ice before leaning out. If you lean the mixture while there is ice in the carburettor then the mixture will be too lean when the ice melts.

4. Generally the POHs for small Cessnas call for carb-heat whenever you throttle fully back as when gliding or practicing stalls and spins.

5. Generally the small Pipers POH’s will tell you to only use carb-heat if you have an indication of icing.

6. Almost all small aircraft engines will gather ice when taxying over wet grass –particularly on cool mornings.

7. If, when you throttle fully back to stop at the holding point, the engine tries to die – that’s a sure sign you have picked up ice while taxying.

8. Always clear any chance of carb-icing before you do your engine runup and mag-check.

9. The temperature in the carburettor can drop by as much as 38°C (100°F).

10. Beware of high humidity, particularly when cruising just below cloud.

11. When you apply carb-heat you must expect the revs to drop about 150 RPM.

12. If ice is present the revs will drop more and if there is a lot of ice you may get a major drop in revs, perhaps 500 or more, and the engine will run extremely rough. Don’t get a fright and slam the carb-heat off. That

has caused many 150s and 152s to do unnecessary forced landings. Be brave –keep the carb-heat applied and life will return to normal.

13. RTFM (Read The Factory Manual).

If the engine stops, without expensive noises, it’s almost certainly a fuel problem:

• Close the throttle – you don’t want the engine surging when the new fuel comes through.

• Change tanks

• Switch the pump on

• Richen the mixture

The mixture control knob is ignored at your peril. j

One of the world’s most eagerly awaited piston single engine aircraft designs has finally arrived in South Africa. ZU-KTR is a long awaited Panthera, proudly owned by Bertus Kritzinger, a Free State trucker, and based at New Tempe in Bloemfontein, where the well-known Ferriera Aviation has assembled it.

WITH ITS INCREDIBLE PERFORMANCE claims, the Pipistrel Panthera captured pilots’ imaginations when it was launched – but it has had a long gestation.

Pipistrel have won many prizes for efficient planes and so the Panthera generated much excitement when it was announced at Aero Friedrichshafen. If it had been any other company, the claims would have been laughable.

The key claim was that the Panthera was going to manage, “four seats, 200 knots and 1,000 nm.” These were the magic numbers Pipistrel CEO Ivo Boscarol set as a challenge for his engineers in 2007. This was taken to mean a

200 knot cruise – on just 210 hp. Considering that the sleek Piper Comanche 400 cannot do that on 400 hp, many observers just quietly shook their heads and adopted a wait and see approach to the Slovenian plane builder’s aims.

Time passed and it seemed that Pipistrel were indeed having problems making their numbers come true when Panthera development was moved to a back burner. Then it was quietly announced that the engine had been increased from the original’s 210 hp to 260hp.

So the big question is – has Pipistrel managed to nonetheless create a 200 knot speedster that can comfortably seat 4 for 1000 nm?

Pipistrel elected not to use a turbocharger for high altitude speed.

Founded in Slovenia by the charismatic and brilliant Ivo Boscarol in 1989, Pipistrel has always been committed to efficient aircraft. Significantly he has now certified the first electric trainer, the Velis Electro, built on the nuttily named Pipistrel Virus base.

After the Panthera’s launch in 2012 things went quiet. “The main reason it was held up was because Pipistrel was contracted by several governments, including the U.S. government, to convert their two-seat airplanes into unmanned aerial systems for surveillance use by the military,” the company said in a later announcement.

engine options: an all-electric version, an electric hybrid and a conventional internal combustion engine (ICE) from Lycoming. Unsurprisingly so far only the ICE version has made it to market. However, in 2016 a Panthera mock-up received a hybrid-electric engine, being powered by either a 200-kW electric motor driven by batteries only, and by a 100-kW generator-only, and by both combined. In October 2021 Pipistrel announced that the hybrid version had completed the first phase of its flight test programme.

In the years since the 2012 launch, the big change was that the fossil-fuel burning engine was upgraded from the 210 hp IO-390 to the 260 hp IO-540. The extra 50 hp no doubt helped with the elusive top speed goals.

The Panthera was designed from the outset to have not just one – but three, radically different

Pipistrel had originally specified the IO-390 because of its good power-to-weight ratio and

Both front seats get their own gull-wing doors.

because it could burn Mogas (car petrol) . Except, in the end it couldn’t, as Lycoming said that the IO-390’s 8.9:1 compression ratio was too high for Mogas. So Pipistrel switched to the 260-HP IO-540-A5V4, which does allow Mogas.

The IO-540 weighs about 100 pounds more and is longer. Pipistrel addressed the centre of gravity by adding additional length to the rear airframe. The extra power also helped with high density altitude operations. The max all up weight was increased by 210 lb to make up for the extra weight of the engine.

aspirated six for maintenance and operational simplicity,’ he said.

The Panthera is the low-slung sportscar of the air. Its commitment to a low profile is reminiscent of the iconic Ford GT40, which was only 40 inches high. To get this low, sleek look, the canopy is not far from horizontal and, like a glider, needs to be kept spotlessly clean if it is to be properly transparent, with minimal distortion.

At the time of the engine change, Tine Tomažič, the Director of Engineering, said, “A lot of this decision was made because customers want good hot and high performance. We have lots of people coming from South Africa, from Argentina, from Mexico, from Colorado, places that would otherwise demand a turbocharger solution. But instead of going to a turbocharged four-cylinder, we decided to go for a normally

Composite construction may be sleek, but it’s not necessarily lightweight. The 260 hp Panthera is now a 2900 lb AUW plane with a useful load of about 1100 lbs. That makes it comparable with the Mooney Acclaim and 240 pounds lighter than recent Cirrus models – and even about 130 pounds lighter than the big Diamond DA50.

Interestingly Tomazic said, “Fuel capacity remains the same, 220 litres (58 USG) because for the given mission, the airplane will not consume more fuel. We are targeting the same cruise speed of 200 knots true and the same 10.5 gph.”

Dimesionally, the Panthera is the smallest. It’s the same length as the Cirrus SR22, but the wingspan is almost three feet shorter. And even with its tall T-tail, the Panthera is nearly a foot shorter than the Cirrus. Notably, the cockpit is low and wide, but at 47 inches still narrower than the Cirrus’s 49 inch width. Once seated, the lack of headroom makes it feel tighter than an SR22.

Gullwing doors are not popular because they let the rain in, and if the plane is inverted, may be impossible to open. Yet accident reports suggest that occupants being trapped after a crash doesn’t appear to be a real problem. Either planes don’t flip much or, if they do, survivors manage to get out okay. Further, the Panthera’s rear hatch is supposed to be an emergency exit – and so a glass-cutting hammer is provided. Gullwing doors opening in flight is another concern, because the door is likely to hit the tail. Pipistrel has addressed that with a robust closing mechanism that uses an over centre lock.

The cabin has two large gullwing doors on either side, and, for the rear occupants, an even larger gullwing hatch, similar to Diamond’s DA40. It’s surprisingly easy to step down into both the front and back seats.

Unlike the Cirrus, which has a long single-piece wing and thus has to be flown from the factory to South Africa, the Panthera has removable wings. The whole aircraft fits into a standard shipping container. Like composite gliders, the wings have overlapping spars that are mounted to the fuselage and each other with hefty steel pins. Also like a glider, the controls use push rods for the ailerons and elevator.

Beautifully smooth composite wing worthy of a competition glider.

Getting aboard requires stepping onto the wing. The flaps are about two-thirds of the span so the section over the wing walk area on both sides is protected with a solid surface. Technically, that makes that section a split rather than semiFowler flaps.

The flaps are electric and the gear is similarly electric, driven by rods and tubes. The backup system is a crank located in the centre console between the two front seats. It’s a pity they could not make a gravity free-fall system.

The Panthera has a whole-airframe parachute as standard, but unlike the Cirrus, it is not required as a condition of certification, and so may not need expensive 10-year servicing.

Getting in is easy. You can step straight onto the cockpit floor and use a handgrip to lower yourself into the seat. But getting out requires considerable upper body strength to pull yourself up with one hand.

ZU-KTR has a dual Garmin G3X Touch, driven by a GTN 650 and GTN 750 with GFC500 autopilot. While this provides plenty of capability, some buyers may view it as a step down from the G1000 NXi found in new Cirrus and Diamond models. Because of the Panthera’s smaller panel, the G1000NXi may not fit.

ZU-KTR does not have Garmin’s ESP envelope protection, even though it is available for the autopilot and is a planned addition. And while the NXi/GFC 700 in the Cirrus and Diamond

may eventually get Garmin’s Autoland option, it’s not contemplated for the Panthera. ADS-B is via the GTX 345 transponder.

There is a secondary battery to power an essential bus that includes the primary flight display and one of the two ADAHRS units. Additional backup is provided by a Mid-Continent SAM MD302, plus the Touch display has reversionary capability for primary attitude.

There’s plenty of space for maps, engine monitoring and the primary flight display. There is a clever sub-panel that shows the cabin air status. Push the test button and it shows the status of gear, flaps and fuel remaining as a percentage.

comfortable to use and the Beringer toe brakes effective.

The view forward through that long sloping windscreen isn’t great. The instrument panel glareshield is higher than a C210's and the seating position is laid back. A sloping centre column partially obscures the forward view. This means you can’t easily see beyond the right side of the nose when taxiing. And when turning from crosswind onto downwind in the circuit you won’t easily see traffic straight in to the downwind leg.

Having plenty of glass makes the cabin hot on a sunny day. The gullwing doors make it possible to taxi with doors fully open and this provides more than enough cooling from the prop.

Taxi is smooth, thanks to the trailing link gear. The bottom-hinged rudder pedals are

Unlike the Americans, the latest European designs have control sticks, which provide a more precise, uncompromised feedback. On takeoff this is immediately noticeable. Thanks to

a steerable nosewheel, taxiing is easy and accurate.

Given that it was designed for speed – the question is how much faster is it – if at all – to its competitors?

Its natural competitor is the similarly built-for-speed Mooney Ovation, the sleek Diamond DA50 RG, and the 315 hp Cirrus SR22.

Pipistrel elected to avoid the weight and complexity of a turbocharger, yet the Panthera is faster than the turbo Cirrus SR22T all the way to 18,000 feet. The Panthera is about 5-knots faster than the normally aspirated SR22 G6. However the 310 hp turbo Mooney Acclaim Ultra is still the fastest.

Pipistrel is not just about speed – it’s about efficiency. For this, the specific range is a measure of how far a plane flies on a pound of fuel. Here the Panthera easily beats both Mooney models but with its

Fit and finish are good enough for high end

turbocharged diesel, the Diamond DA50 RG is the efficiency champion.

The Panthera has about 1100 pounds of useful load and the CofG range is a generous 9 inches, so loading it out of limits takes effort. As a sample weight and balance, with 375 lbs in the front seats and 350 lbs of pax in the back, and 100 lbs of bags, the plane is 50 pounds over gross but still within CofG.

The Panthera gets airborne at about 65 knots with moderate, but not over light pitch force.

During initial climb, the restricted forward visibility is no worse than over the long nose of our Saratoga. The Panthera climbs well, with, at Vy,1600 fpm available initially. However, a cruise climb at 130 knots still yields a 600 to 800 fpm climb.

It’s all about the cruise numbers. And impressively the Pipistrel beats its book figures. On a hot ISA +30 day, at 8000 feet, it delivered 184 knots true on 13 GPH at 65 percent power. At 55 percent, it cruised at 174 knots on about a gallon less.

A reviewer went so far as to call the Panthera’s handling ‘fighter like, but the only fighter I’ve flown is the P-51 and the Panthera is way better in ease of control and lack of bad habits.’ However, the stall isn’t as benign as say a Diamond DA40. If held deep into the stall, it will drop a wing hard and fast.

Pitch stability is lower than its competitors. If the nose is high and the stick released, the plane takes its time damping the phugoid. In the dive it almost reached Vne before heading back up.

Despite its super-slippery design, Pipistrel have not given it speed brakes. So it takes careful speed management and planning to get slowed to the relatively low 106-knot gear extension limit. (The Mooney Ovation is 140 knots.) Max flap speed is also a low 106 knots.

Seventy-five knots is the recommended across the fence Vref. The trailing link main gear makes bad landings smooth. Although the Panthera was never designed to be a STOL plane, a proficient pilot should easily manage a 2500-foot runway at light weights.

If you want responsive handling, efficiency and head turning styling, the Panthera is for you.

It carries a little more than a Mooney, but less than a Cirrus, and it’s a little faster than both, including the SR22T at lower altitudes. It’s more efficient than both, but at the expense of a less spacious cabin than the Cirrus.

The Panthera promised a 200-knot plane that would be more efficient than anything else – and greener too, since it would eventually be offered in both pure electric and hybrid-electric versions. What it has, at least for now, is a not-quite200-knot top speed plane with better efficiency than modern Mooneys, an adequate albeit not capacious cabin, and sporty, well-harmonized handling.

Where it fits in a market dominated by Cirrus, or even if it fits, is difficult to predict.

Price (as tested): about $900,000

Engine: Lycoming IO-540V-V4A5

Horsepower: 260 hp

Propeller: MT three-blade constant-speed composite

Seats: 4

Length: 26 ft. 6 in.

Cabin Width: 3 ft. 11 in. Height: 7 ft. 2 in.

8

opt long-range tanks

Rate of Climb: 1,300 fpm at max gross weight

Maneuvering Speed: 143 kias

Fuel Burn: 13.6 gph at 75% power at 7,500 ft.

Stall Speed, Flaps Up: 60 kias

Takeoff Over 50 Ft. (ISA, sea level) 2,155 ft.

Max Operating Altitude: 25,000 ft.

Cruise Speed at 65% Power: 185 knots at 7,500 ft.

Never-Exceed Speed: 220 knots

Fuel Burn: 10.8 gph at 55% power at 7,500 ft.

Stall Speed, Full Flaps: 55 kias

Landing Over 50 Ft. Obs: (ISA, sea level) 1,130 ft

Aircraft registration: ZS-DED

Date and time of accident: Soon

Type of aircraft: Cessna 172

Pilot’s name: Joe Doe

Type of operation: Private

PIC license type: PPL

License valid: Yes

PIC age: 56

PIC total hours: 120

• This discussion is to promote safety and not to establish liability.

• CAA’s report contains padding and repetition, so in the interest of clarity, I have paraphrased extensively.

PIC hours on type: 20

Last point of departure: Rand Airport

Point of intended landing: Private strip in Natal

Location of accident site: Mountainous terrain

Meteorological info: IMC

POB: 1+2

People injured: 0

People killed: 1+2

THE PILOT PLUS HIS WIFE and teenage daughter took off from Rand Airport for a flight to a private strip 20 miles south of Ladysmith in the Natal midlands. They intended to spend a long weekend at a family reunion.

The pilot obtained a weather forecast which indicated extensive mid to low level cloud with occasional embedded thunderstorms in large parts of Natal.

According to two witnesses who spoke to the pilot before takeoff at Rand Airport, they had both

advised him to postpone the flight until the next day when the forecasts were for fine weather all the way. He told another witness that he had to be there that day for his father’s 80th birthday.

At about 16h30 local time, a farm worker in the Ladysmith area said he heard an aircraft overhead but couldn’t see it because the clouds were very low and covered the hilltops in the area. The witness said that it sounded as if the aircraft was circling overhead. Then the engine noise increased steadily until the aircraft appeared out of the cloud in a steep nose-down and banked attitude. It impacted

The aircraft caught fire on impact.

the terrain in a small wooded area. He said there was a loud noise and a bright light as the aircraft exploded in flames.

The witness ran to a farm house about a kilometre away. He notified the farmer and then accompanied him plus two farm workers in a pickup truck to the scene of the accident.

The aircraft was completely destroyed by the impact and fire. The engine was buried in the soft earth following recent heavy rain. There were no survivors.

OH DEAR, oh dear, when will they ever learn? Well, that was my first thought. However, I must confess that, through a friend, I happen to have inside knowledge of some of the events leading up to this accident. There are three things that stood out for me.

1. He was a particularly conscientious pilot who made a point of doing everything correctly and legally.

2. He was heard to be bragging about a previous extended flight into cloud during which he eventually descended into a broad valley when the GPS told him he had passed the mountain tops.

The aircraft was correctly licensed and maintained. The pilot was correctly licensed and current. He did not hold an Instrument Rating or Night Rating.

During the pilot’s recent PPL training and type conversion he had a total of six different instructors.

The pilot lost control of the aircraft while on a VFR flight when he entered IMC. It is possible that he encountered thunderstorm activity in the area. The aircraft was not equipped with weather radar.

3. He did not have one instructor who was overall responsible for his training.

Points 1 and 2 above simply don’t gel. It makes no sense that a law-abiding pilot would brag about an illegal operation. The only conclusion I can come to is that he saw nothing wrong with what he did because the dangers of VFR into IMC had never been sufficiently explained or demonstrated to him.

Unbelievably, it seems this was the case: The pilot had no idea of the dangers of VFR into IMC. Not one of his instructors had sat him down and explained the problems of flying without a visible horizon. Ideally, one of them should have put him under the hood, or taken him into cloud and let him experience loss of control first hand.

I believe this should be part of every pilot’s training. No amount of explanation is a substitute for the experience of losing control in cloud. It’s almost impossible to believe that the senses you have trusted all your life can suddenly abandon you.

Now his story takes another twist. I was chatting to a friend of mine - a retired airline pilot, who we will call Captain Mac. Now, Mac had been acting as a sort of mentor to Joe Doe. It seems that the pilot had previously flown through a small amount of cloud using his autopilot. Captain Mac had gently reprimanded him and gone to a lot of trouble explaining the dangers of going into IMC without a current instrument rating.

So the accident pilot did receive wise guidance to not do it again. He simply hadn’t taken Captain Mac’s warning to heart. He was a confident and successful man who basically didn’t believe that he wouldn’t be able to tell up from down.

In summary, he had ventured into a bit of cloud, on the autopilot, and taken some mild flak from Mac. He ignored this and again flew into cloud, on autopilot, for a lengthy instrument flight and GPS letdown. This is when Mac told me what was going on. He was incensed about his fledgling acting like a Darwin Award contestant.

Now many of us older pelicans have regretted not crapping on youngsters who were going off the rails. We later hear that the newbies

have turned their unsuspecting families into strawberry jam against a cliff. We naturally feel guilty for not speaking up.

Sound familiar? The doctor in a Bonanza syndrome.

Captain Mac did speak up – pretty forcefully. Here’s part of an email he sent to the accident pilot:

I am compelled to comment, this I do as somebody with 40 years of flying experience on many, many types, both small and very large, specifically with more than 30 years as an ALTP, now ATP, with Instructors Rating Grade 1, IR Testing Officer and DE.

IT’S TOTALLY UNACCEPTABLE FOR ANY NON INSTRUMENT RATED PILOT TO ENTER CLOUD

It’s highly dangerous as the likelihood of suffering Spatial Disorientation with catastrophic results is almost 100% guaranteed.

There are some who think they can do it but mark my word they can’t. Spatial Disorientation can strike any pilot, even a 20,000 hour Airline pilot.

Joe’s reply was extremely brief and basically gave Captain Mac the middle finger.

At this stage Captain Mac and I gave up on the man and quietly entered his name in our LBBs. These are the Little Black Books in

which many experienced pilots record the names of those most likely to kill themselves.

When the inevitable happens we draw a red line through the name, and enter the date. And perhaps shed a tear for the young family whose lives were crushed by one man’s ego.

The official probable cause is simply – VFR into IMC. But why would a well-trained pilot do that? Would an Air Force pilot do it? Or one who trained at a top professional pilot academy? I think not, and I’ll tell you why.

It’s because professional schools are disciplined. They plan each step of a pilot’s training, and they do their best to pair instructors and pupils appropriately. More mature pupils don’t want to be continually corrected by instructors younger than their kids. Female pupils often prefer female instructors. There are a hundred considerations when matching instructors to pupils.

So when you phone to make a booking, a good school doesn’t cast around to see if they can find an instructor who is not doing anything. They tell you when your instructor will be available. It doesn’t sound like a big deal does it? Well, it’s a huge deal – from the instructor’s point of view, and yours.

No instructor can put heart and soul into every pupil who passes his way. He doesn’t know what your strong and weak points are. He can spend the whole lesson finding these out, without teaching you anything new. Also, how can he really care about your future if he is never going to see you again?

Strangely, your instructor is human – his reward is in being creative. He takes pride in turning a fledgling into a good, safe pilot.

So if you have one instructor who is responsible for all your training, then he

Every pilot should have to watch this video and then have IMC demonstrated with an instructor.

rejoices in your successes and supports you through your difficult patches.

The single-instructor system ensures that each exercise has been covered thoroughly and tested – usually by the CFI.

Take-home stuff:

1. If your school can’t give you your own instructor who will conduct at least 80% of your training, find another school.

2. The syllabus doesn’t call for a loss-ofcontrol-in-IMC demonstration. Ask your school to include it. It’s going to happen to you at least once in your life. Make sure that when it does, it’s a planned exercise with your instructor at your side to rescue you.

This story is true except that the accident hasn’t happened – yet. If you know the pilot – or others like him – perhaps you can show him this story. j

Price: R950K excluding VAT

R2 million (replacement kit would cost over R2.8 million before building)

PA-24 – 180 hp: 1962. ZS-CXH.

Fantastic cruiser and hour builder.

Airframe: 2440. Lycoming O-360-A1D

Prop:Hartzell HC-C2YR-1BF

Avionics: Standard six pack

Viewing: Worcester FAWC

R3.5 million

Airframe: 25 hours. ZU-TUC.

Engine: Flygas Supercharged Rotax 912 uls

141 hp. 300 hours since new

Propeller: Elitest carbon fibre electric variable pitch propellor – 25 hours

Instruments: Mostly MGL but too many to list

2022 ZU-IWY. A Super Cub on steroids. A bigger, more powerful and faster bush plane

Airframe: 45 hours. Engine: Titan IO-360 180 hp

Prop: Hartzell HC-C2YR-INX

Avionics:Dynon Skyview with autopilot and Aera 600 GPS Viewing: Worcester

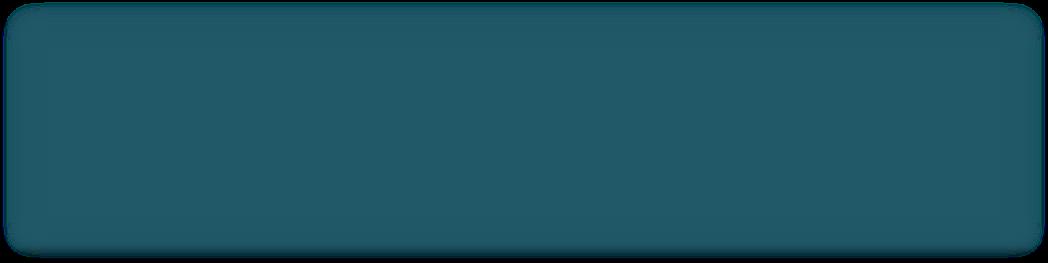

At Helideck Certification-Africa, we’re dedicated to providing a local solution for a global necessity – the certification of offshore helidecks.

CERTIFICATION FOR SAFETY:

Regular helideck certification is crucial for the safety of helicopter crew and passengers, ensuring the protection of your valuable assets.

ISO9001:2015 APPROVED: Helideck Certification-Africa adheres to international quality standards.

ADHERING TO UKCAA CAP 437:

We base our inspections on this recognized global standard, assuring the highest level of safety for offshore helicopter operations.

PRECISION FRICTION TESTING:

We employ the Findlay Irvine Microgrip friction tester, the only friction tester approved by UKCAA CAP 437.

OUR COMPREHENSIVE INSPECTIONS COVER

• Helideck markings and obstacle-free sectors

• Identification of operational Helideck limitations

• Competence of Helideck Crew

• Communication procedures

• Firefighting and rescue equipment

• Emergency Response Planning

• Helicopter operational procedures

YOUR SAFETY IS NON-NEGOTIABLE. CHOOSE HELIDECK CERTIFICATION-AFRICA FOR PEACE OF MIND AND COMPLIANCE WITH GLOBAL SAFETY STANDARDS!

ZS-ABB, an Embraer ERJ135, seen here in Finland, has been exported to Turkey.

April

has been a very quiet month on the local aviation marketplace with only nine new registration allocations and three deletions, according to the officially-supplied register review.

REGULAR READERS of this column will by now be familiar with quite a few corporate jets that I have recently mentioned that are either registered in South Africa and operated in Russia or that are briefly registered on the ZS- register to “sanitise” their onward sale to Russian owners under western sanctions.

it is now on the Russian registry

So this month I would like to start with a topical deletion from the South African register of a Embraer Legacy 650 corporate jet, ZS-ABB (14501210), as this also ties in with a newly-registered Bombardier Global Express 6000, ZS-BLA (9718) that my attention was drawn to by one of my contacts in the industry. This particular Legacy 650 was the subject of an article in the local press by the well-known aviation and defence investigative

journalist, Erika Gibson, that traced its journey from Basel to Moscow on 27 August 2022, where it has been resident ever since. The jet’s ZS- registration was finally cancelled on 28 March as “sold to Turkey”. I am prepared to bet it is now on the Russian registry if it follows the pattern of the recent registerhopping by some corporate jets.

Also on this subject, a Bombardier Global Express ZS-BLA (9718) was noted flying to Moscow on 21 April. This former Portuguese-owned jet (where it flew as CS-DHZ) does not yet feature in the updates supplied by the SACAA. This aircraft has also not been anywhere near SA since its registration, so it seems to follow the same pattern as the preceding corporate jets that ended up in Russia.

ABOVE Boeing 737-400, VH-TJK is now ZS-TEY in South Africa.

BELOW: Bombardier Global Express ZS-BLA as VP-BZN - now in Russia?

ABOVE: ZS-HSG, an MBB BO-105, has been exported to Kazakstan. Image Fanie Kleynhans.

BELOW: FlySafair's ZS-FGB has been exported back to Safair parent ASL.

The only other fixed wing type deleted from the register is a Cessna 208B Grand Caravan, ZS-JAX that has been exported to Namibia.

Closing the register deletions is another former SAPS Airwing Bo-105, ZS-HSG (S-747) which departs SA on export to Kazakhstan. This is one of the several Bo-105s sold on auction by the SAPS Airwing following their withdraw from service.

Turning to the new registrations, a Boeing 737-476(SF) ZS-TEY (24436) was delivered to OR Tambo International Airport on 17 February with the Gambian registration C5-TEY, so an easy one for the paint shop to change. The aircraft is the first of three cargo-configured Boeing 737-400SFs to join

Africa Charter Airline’s fleet. This particular Boeing was delivered new off the production line to Australian Airlines in February 1991. The carrier was an all-economy, full-service international leisure carrier, and was a wholly owned subsidiary of Qantas. This airline brand was discontinued in 1993, but the jet continued operating for Qantas until being withdrawn from use in April 2013. It was then acquired by Iceland’s Bluebird Cargo (later rebranded Bluebird Nordic) in March 2015 until being withdrawn from the fleet in March 2023. It was then acquired by Africa Charter Airline in December 2023.

The first Pipistrel Panthera 540 has been registered in South Africa. This sexy fourseat retract-gear T-tail plane is powered

C-FFLA, a Boeing 737-800, is now ZS-FGN with FlySafair.

ZS-JAX has been exported to Namibia - image ORTIA Planespotter.

by a 260 hp Lycoming IO-540 engine that gives a claimed 198kt cruise speed and 1000nm range. Absolute Aviation was appointed the agents for the manufacturer in May 2023 and has been marketing this manufacturer’s product range in the local market.

Other new additions include one each of the popular Sling TSI, Kitplane Safari and Orion Cub. A single Kallithea 915IS Gyroplane and an unknown type, a Janus Brookfield with registration ZU-RJO, closes this month’s NTC register additions.

In closing, Safair recently said farewell to two B737-800s ZS-FGA (27977) and ZS-FGB (27978) which left Safair’s fleet and were ferried to Liege in Belgium. Both will apparently be converted to freighter configuration for operation by the airline’s owner ASL. The carrier has meanwhile taken delivery of a newer B737-86N N105TS (36548) on 7 May that will reportedly become ZS-FGN. But more on this next month. j

T-hangar available for rent at a secure private farm airstrip near White River. No landing fees. Power available. R2200/m. Contact Jeremy (064 931 1642).

We perform SANAS certifications on all your:

Acoustics ( eg. CEL 350 )

Vibration ( eg. Rion VA -11)

Human Vibration ( eg. Quest Hav Pro)

Electrical DC/LF Equipment – inhouse or on site (eg. Fluke Multimeters, Insulation Testers)

When armed forces are scrambled, they put their lives on the line, so they need a helicopter they can trust to get the job done, whatever the weather, whatever the situation. Versatile, multi-purpose, and equipped with a renowned automatic flight control system and upgraded avionics, the H225M is the long-range helicopter they can rely on. There will always be risk and danger, but wherever the call comes from, the H225M will help to keep our world beautiful and safe.

Fuel Prices as at 19/04/2024

Fuel Prices as at 20/05/2024

Prices

Prices include VAT but exclude any service fees

Airfield Avgas Jet A1

Baragwanath - FASY

Beaufort West - FABW

R36,00

R33,80 R 25,85

Bloemfontein - FABL R32,00 R20,30

Brakpan - FABB

Brits - FABS

Cape Town - FACT

Prices include VAT but exclude any service fees

Airfield Avgas Jet A1

Baragwanath - FASY R36,00

Beaufort West - FABW

R34,00

R30,45

R32,20 R19,96

Cape Winelands - FAWN R33,00

Eagle's Creek

East London - FAEL

R32,50

R36,31 R20,83

Ermelo - FAEO R30,93 R24,73

Gariep Dam - FAHV

George - FAGG

Grand Central - FAGC

Heidelberg - FAHG

R33,80 R 25,85

Bloemfontein - FABL R33,00 R20,30

Brakpan - FABB R34,50

Brits - FABS R31,10

Cape Town - FACT R33,93 R19,96

Cape Winelands - FAWN R33,00

Eagle's Creek

East London - FAEL

R33,50 R23,00

R36,97 R19,88

R35,59 R24,55

R30,00 R23,50

Hoedspruit Civil - FAHT R33,47 R27,90

Kimberley - FAKM NO FUEL R21,90

Kitty Hawk - FAKT

R32,00

Klerksdorp - FAKD R31,66 R27,99

Kroondal / Airspan R32,43

R33,50

R36,30 R19,55

Ermelo - FAEO R31,51 R24,73

Gariep Dam - FAHV

George - FAGG

Grand Central - FAGC

Heidelberg - FAHG

R34,00 R23,00

R36,97 R18,87

R35,59 R24,55

R32,20 R23,50

Hoedspruit Civil - FAHT R33,47 R27,90

Kimberley - FAKM NO FUEL R22,52

FAKD

Kitty Hawk - FAKT R32,40

- FAKS

Klerksdorp - FAKD R32,85 R22,64

Kruger Intl Nelspruit R33,95 R25,15 Kruger Mpumalanga Intl -FAKN R33,95 R28,37

Kroonstad - FAKS R32,74

Krugersdorp R32,50

Kroondal / Airspan R35,10

Kroonstad - FAKS R32,40

Krugersdorp - FAKR R30,00

Kruger Mpumalanga Intl -FAKN R33,95 R26,91 Kruger Mpumalanga Intl -FAKN R35,15 R27,24

Lanseria R34,04 R23,00

Krugersdorp - FAKR R32,50

Lanseria - FALA R34,73 R24,84

Kroondal / Airspan R32,43 Kroondal / Airspan R35,10 Kroonstad - FAKS R32,74 Kroonstad - FAKS R32,40 Kruger Mpumalanga Intl -FAKN R33,95 R26,91 Kruger Mpumalanga Intl -FAKN R35,15 R27,24

Margate R34,04 R23,06

Krugersdorp - FAKR R32,50

Lanseria - FALA R32,78 R23,35

Middelburg

Krugersdorp - FAKR R33,35

R37,95 R23,00

Margate - FAMG NO FUEL NO FUEL

Middelburg - FAMB

Margate - FAMG NO FUEL NO FUEL

Lanseria - FALA R34,16 R23,69

Middelburg - FAMB R33,00 R25,99

Krugersdorp - FAKR R33,35 Lanseria - FALA R32,78 R23,35 Lanseria - FALA R34,16 R23,69

Margate - FAMG NO FUEL NO FUEL

Margate - FAMG NO FUEL NO FUEL

Margate - FAMG NO FUEL NO FUEL

Morningstar R34,56

Morningstar R32,25

Middelburg - FAMB R31,86 R25,99

R31,86 R25,99

Middelburg - FAMB

Mosselbay R37,50 R20,50

Morningstar

Morningstar R31,90

Nelspruit

Mosselbay - FAMO

Oudtshoorn FAOH

R31,90

R32,32 R28,44

R37,50 R27,50

Nelspruit - FANS R32,55 R24,73

Oudtshoorn - FAOH

Parys - FAPY

Pietermaritzburg

Middelburg - FAMB R35,83 R25,99

R35,83 R25,99

Mosselbay - FAMO R37,50 R23,00

Morningstar R33,50

Mosselbay - FAMO R37,50 R27,50

Mosselbay - FAMO

R35,19 R23,10

Morningstar R33,50

Nelspruit - FANS R33,41 R26,14

Nelspruit - FANS R32,55 R24,73

Nelspruit - FANS

Parys POA POA

Parys - FAPY

Pietermaritzburg - FAPM

Pietersburg Civil

Pietersburg Civil - FAPI

R35,19 R23,10

R33,00 R23,52

Oudtshoorn - FAOH

R37,70 R24,32

Mosselbay - FAMO R37,50 R27,50

R37,50 R27,50

Oudtshoorn - FAOH R35,19 R23,10

Oudtshoorn - FAOH R35,19 R23,10

R33,40 R25,80

Pietersburg Civil - FAPI

Nelspruit - FANS R34,98 R25,30

R34,98 R25,30

Oudtshoorn - FAOH R35,19 R23,10

Parys - FAPY R28,99 R22,23

R35,19 R23,10

Parys - FAPY

R33,00 R23,52

R31,80 R23,70

R30,50 R24,70

Pietermaritzburg - FAPM R33,40 R25,80

Plettenberg Bay R34,60 R25,00

Plettenberg Bay - FAPG NO FUEL R25,00

Port Alfred - FAPA

Port Alfred R33,50

Port Elizabeth

Port Elizabeth - FAPE

Potchefstroom - FAPS

Rand

Rand - FAGM

Robertson - FARS

Robertson FARS

Rustenburg - FARG

Rustenberg FARG

Secunda - FASC

Port Alfred - FAPA

R33,50

Port Elizabeth - FAPE

R35,48 R24,04

Potchefstroom - FAPS

Rand - FAGM

R30,50 R24,70

Parys - FAPY R35,67 R22,67

Pietermaritzburg - FAPM

R35,67 R22,67

Pietermaritzburg - FAPM R34,00 R28,10

R33,10 R25,80

Pietermaritzburg - FAPM R33,10 R25,80

Pietersburg Civil - FAPI

Plettenberg Bay - FAPG NO FUEL R25,00

R33,50

Pietersburg Civil - FAPI R33,50 R24,70

R33,50 R24,70

Plettenberg Bay - FAPG NO FUEL R25,00

Plettenberg Bay - FAPG NO FUEL R25,00

Port Alfred - FAPA

R35,19 R24,84

Port Alfred - FAPA R33,50

R35,48 R24,04

Potchefstroom POA POA

R32,43 R22,94

R35,75 R27,50

Robertson - FARS

R30,90

Rustenburg - FARG

Secunda - FASC

Port Elizabeth - FAPE

Plettenberg Bay - FAPG NO FUEL R25,00

Port Alfred - FAPA R33,50

R33,50

Port Elizabeth - FAPE R33,47 R23,46

R32,43 R22,94

Potchefstroom - FAPS

R34,10 R23,98

R33,00

R32,10 R23,65

R31,63 R23,58

Rand - FAGM

R30,90

Port Elizabeth - FAPE R38,30 R24,04

R38,30 R24,04

Potchefstroom - FAPS R28,99 R22,23

R35,75 R27,50

Robertson - FARS

R31,30 R23,65

Skeerpoort *Customer to collect R31,19 R20,70

Rand - FAGM

Rand - FAGM

R32,10 R23,65

Secunda R33,00 R25,88

Skeerpoort *Customer to collect POA POA

Springbok - FASB

Springs - FASI

Stellenbosch - FASH

Springbok - FASB

R30,50 R23,50

Rustenburg - FARG

Potchefstroom - FAPS R35,10 R22,09

R35,10 R22,09

R37,50 R26,00

R35,75 R27,50

R37,50 R26,00

Robertson - FARS

Rustenburg - FARG

R31,63 R23,58

Secunda - FASC

Springbok POA POA

Springs - FASI

R30,00

Swellendam - FASX

Tempe - FATP

Robertson - FARS R32,00

R31,90

R31,90

R32,50 R23,65

R31,00 R23,65

Rustenburg - FARG R32,50 R23,65

R31,91 R25,88

Secunda - FASC R33,07 R25,88

Skeerpoort *Customer to collect R31,19 R20,70

Secunda - FASC R31,91 R25,88

Skeerpoort *Customer to collect R32,85 R19,85

Skeerpoort *Customer to collect R32,85 R19,85

Skeerpoort *Customer to collect R26,75 R19,99

Springbok - FASB

R30,50 R23,50 Springbok - FASB

R36,46 R27,03

Springbok - FASB R33,93 R27,03 Springs R33,70

Stellenbosch - FASH

R37,00

Swellendam - FASX

R31,50 R23,00

- FATP

R33,90 R22,91

Thabazimbi - FATI

Upington - FAUP

R32,93 R23,44

R35,16 R29,60

Virginia - FAVG R35,08 R23,92

Vryburg - FAVB

Vryheid - FAVY

R33,59 R23,70

R32,43

Warmbaths - FAWA R32,50

Welkom - FAWM R33,06 R24,07

Wings Park EL

R31,00 R23,50

Witbank - FAWI R32,50

Wonderboom - FAWB

Worcester - FAWC

R30,69 R21,20

R29,50

R30,00 Springs - FASI

Springs - FASI

Stellenbosch - FASH

R37,00

Swellendam - FASX

- FASI

Stellenbosch - FASH

R34,22

R38,00

R33,20 R23,30

Tempe - FATP

Swellendam FASX R33,80 R22,50 Swellendam - FASX

Thabazimbi - FATI

Upington - FAUP

Virginia - FAVG

Vryburg - FAVB

Vryheid - FAVY

Warmbaths - FAWA

Welkom - FAWM

Wings Park EL

Witbank - FAWI

Wonderboom - FAWB

Worcester - FAWC

R32,09 R22,92

R35,60 R22,59

R35,19 R26,47

R35,54 R23,92

R36,25 R22,85

R35,10

R35,50

R32,32 R22,92

R33,50 R23,50

R32,50

R33,35 R20,35

R34,90

Guy Leitch finds out from AAD Exhibition Director, Ms Nakedi Phasha, how the buildup to this year’s biennial expo is going, and what visitors and exhibitors can expect.

THE 12TH AAD TRADE EXHIBITION and air show has the theme ‘Exploring New Paths, Sharing Solutions, Showcasing Innovation and Capability.’ It takes place at Waterkloof Air Force Base from 18 to 22 September 2024 and is considered to be one of the top six events of its kind in the world. It is the only aerospace and defence exhibition and air show on the continent.

The AAD expo is a partnership between South Africa’s Aerospace, Maritime and Defence Association (AMD), the Armaments Corporation of South Africa (Armscor), and the Commercial Aviation Association of Southern Africa (CAASA), in collaboration with the South African Department of Defence and Military Veterans (DOD).

AAD organisers report that as at May 2024, more than half of the exhibition space has been booked and confirmed. The event will see exhibitors coming from several countries, including the United States, Belgium, and China. The exhibitors include Sweden’s SAAB, Airbus, Turkish Aerospace Industries, and L3Harris Technologies.

topical issues that directly impact the industry. Furthermore, we project at least 60,000 visitors will attend the public air show days to witness the exhilarating aerobatics spectacle,” says Ms Nakedi Phasha.

A unique initiative of the AAD is its youth development programme (YDP). This sees youth from disadvantaged and marginalised communities being exposed to science and technology disciplines and related career opportunities. In 2022, AAD hosted over 9,000 learners through its YDP initiative. For this year’s event, 12,000 learners from across all nine provinces are expected to descend on the base to benefit from this impactful programme.

Being a biennial expo, the show was hard hit by the Covid pandemic. Ms Phasha said that the recovery following the COVID-19 pandemic has varied across sectors and regions, with the aerospace and defence industry being no exception. She points out that they observed a slight decline in attendance during AAD 2022. “However, recognising the importance of AAD 2024 as a catalyst for growth and collaboration, our primary objective is to reverse this trend and make the upcoming expo the biggest and best yet.”

The event has been designed to provide the perfect platform to strengthen existing and establish new partnerships within the defence and related industries.

AAD 2024 will introduce several ‘hubs’ that showcase the latest innovations. For instance, there are Energy and General Aviation hubs, as well as a third hub that features drone and antidrone technologies.

“As organisers, we want to position South Africa as the global pinnacle of innovation, excellence, and a preferred investment destination. We anticipate that more than 30,000 trade visitors will engage with over 300 exhibitors. Visitors can also attend our maiden conference edition to hear thought leaders in the industry, academia, and the defence sector provide insights into