With its large cargo door, quickly reconfigurable cabin, and access to short, unpaved runways, the new PC-24 provides unmatched versatility.

PILATUS CENTRE SA

Authorised Sales Centre

ONE OF THE FAILINGS of many local governments is that they do not appreciate the value of having an airport, no matter how small.

Across South Africa there are countless examples of local authorities which have surrendered their airports to land invasions and squatter communities. Examples that spring to mind are Nylstroom, Estcourt and Hermanus, with many more under threat.

The fate of Plettenberg Bay Airport hangs in the balance. It is the subject of a three way tussle between the local authority; the Bitou Municipality, which owns the land, the hangar owners and users of the airport, and the Cape Winelands airport developers, who, presumably frustrated by their lack of progress with the old Fistentekraal Airport outside Cape Town, are now trying to run (or is it ruin?) the Plett Airport as well.

global transportation network, connecting cities and countries, facilitating international trade, and enabling cultural exchange.

Thus the significance of airports extends beyond their primary function of air travel; they act as hubs of economic activity, generating employment, stimulating local businesses, and attracting investment.

One of the reasons local governments do not fully appreciate their airports is that airports are seen as the playpens of those rich enough to have aeroplanes. However countless studies confirm the importance of airports to small town economies. Regional Horizons magazine (Q1, 2019) notes that, ‘airports… are significant engines of economic development and catalysts for growth in the modern era.’

There is a well-known aphorism:

“A mile of highway will take you a mile, but a mile of runway will

Small town governments need to appreciate that airports are not just places for the rich owners of aircraft to land and takeoff; they are pivotal to the

Airports have become integral components of the urban landscape, often shaping the economic fortunes of the cities and regions they serve. The development of an airport can transform what might have been a sleepy town or a rural backwater into a bustling economic centre. This metamorphosis is evident in numerous examples worldwide, where airports have acted as magnets for economic activity, drawing businesses, tourists, and residents alike. Dubai is a good example.

Airports play a crucial role in facilitating global trade. They are key to the value chain, enabling the rapid movement of goods across continents. This capability is particularly crucial in today’s global economy, where the competitive advantage from speed and efficiency are paramount.

Appreciating the economic impact of airports on local communities is not just about quantifying the direct financial benefits. It is also about appreciating the broader role these complex infrastructures play in shaping the social, cultural, and economic landscape of the regions they serve.

The SACAA tries hard to develop aviation amongst disadvantaged communities. I venture to propose that it would achieve a far better return for its efforts if it educated local governments on the value of their airports.

j

SALES MANAGER

Howard Long sales@saflyermag.co.za 076 499 6358

TRAFFIC

Howard Long traffic.admin@saflyermag.co.za

ACCOUNTS

Angelique Joubert accounts@saflyermag.co.za

EDITOR

Guy Leitch guy@saflyermag.co.za

PUBLISHER

Guy Leitch guy@saflyermag.co.za

PRODUCTION & LAYOUT

Patrick Tillman www.imagenuity.co.za design@saflyermag.co.za

CONTRIBUTORS

Jim Davis

Peter Garrison

Hugh Pryor

CONTRIBUTORS CONTINUED

John Bassi

Morne Booij-Liewes

Laura McDermid

Darren Olivier

Jeffrey Kempston

ILLUSTRATIONS

Darren Edward O'Neil

Joe Pieterse

WEB MASTER

Emily Kinnear

When a truly exceptional photo opportunity comes along, the truly exceptional aviation photogs are called on to make the photo opportunity work. Such was the FlySafair flyover of the final SpringboksAll Blacks rugby game at DHL Cape Town Stadium,

Justin de Reuck and the two crews planned the flight meticulously and then flew it with Justin shooting from a Piper Seneca with the door off. Justin used his trusty Canon EOS R6 Mkll. The lens is a Canon EF 24-105mm f/4L IS USM ll. The actual focal length was a very wide 24mm, for the in-your face effect. Exposure: 1/2000@ f/5.0 ISO 200

The pilots involved were:

• Pilot in Command (PIC): Captain Pierre Gouws

• Second-in-Command (SIC): Captain Steve van der Merwe

• Safety Pilot: First Officer Scott Ternent

• Reserve Pilot: Captain Peter Ladiellis

• Camera-ship Pilot: (PIC) Captain Alewyn Burger; (SIC)Captain Trevor Warner ; (Safety Pilot) First Officer Anneri Kemp

Speed was planned for 150KIAS and routing around Robben Island and down the Atlantic Seaboard to Cape Point, followed by the camaraship formating on the Boeing down the glideslope for RWY 19 at FACT and photographing the landing.

The meticulous planning and briefings happened over two online Teams meetings in the days before and then a final briefing of just the cameraship crew before departure.

a

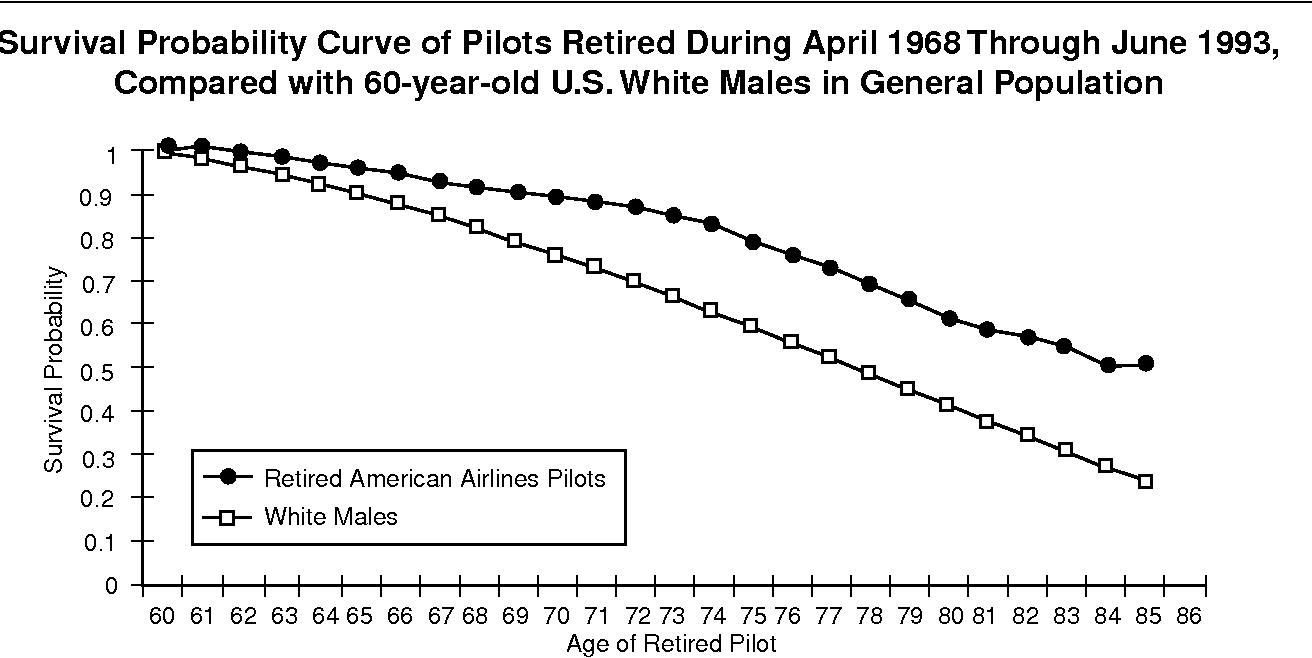

A QUESTION THAT HAS BEEN ARGUED for years in the cockpits, briefing rooms, remuneration negotiating tables and the watering holes of commercial aviation is; what is the life expectancy of an airline pilot after he retires?

Because airline pilots retire after a career of active health checks, the life expectancy of a 60 year-old retired airline pilot should be much longer than that of a 60 year-old from the general population.

However, briefing room chatter and online forums of the airline industry are happy to argue that pilots die at a younger age than the general population. Every time a retired airline pilot dies within the first few years after retirement, the whole idea that airline pilots’ die early is reinforced. Kind of like a confirmation bias.

The results were a shocking surprise, and caused much conflict in the airline industry. Clarke found that 60% of the pilots who retired at 60 had died by the time they were 65.

In stark contrast, the American National Center for Health Statistics says the average life expectancy for Americans who are 60 years old is 20.4 years. At 65 it is 14.7 years for men and 18.6 years for women.

The belief about premature pilot deaths was tackled by Captain Mike Clarke, a British Airways pilot who did a study for IFALPA, (the International Federation of Air Line Pilots Associations). Clarke analysed retirement records from 1953 to mid-1988 for 282 pilots across Britain, Canada and Argentina.

So it was deeply worrying for 60% of pilots to die within five years of retiring at 60 – to put it mildly. And now, with a current 63 or 65 retirement age – how many will live to 70?

The Clarke study reinforced the belief that airline pilots die early. The question is why?

One reason proposed is that, as a group, airline pilots (and from first-hand experience surgeons) have a hard time adjusting to retirement. The problem is that many airline pilots define themselves, and thus their value, as being captains of their ships, god-like in demanding respect and obeisance.

Fifteen years after retiring, a well-known SAA captain still loves to remind anyone who will

listen that he was the commander of the Queen of the Skies – the Boeing 747-400. And so when he retired, he went from being a Top Gun to a mere pop gun.

Hero to zero is another common self-image problem. Many retired pilots become depressed – and that leads to a significantly shorter lifespan, even if you don’t blow your brains out. Even four years after the trauma of Covid, and the massive SAA pilot cuts, at my regular watering hole there are still burned-out husks of pilots who start drinking at breakfast. I expect them to drink themselves into an early grave.

The prevalence of the belief that pilots die early is reinforced by almost every airline pilot having several anecdotes of colleagues who died early after retirement.

The obvious question is what factors associated with being an airline pilot may shorten life expectancy?

Pilots’ wives (or husbands) have a particularly torrid time with their retired captains. One famously remarked that since her husband had retired, “She has twice the husband hanging around the house – yet half the income.”

The stress of a high divorce rate doesn’t help matters.

Readers Health Warning: This list is enough to drive any pilot to drink.

Apart from being depressed, there are many other reasons to blame for early deaths. Being a pilot means having to deal with physical and emotional stressors that have a negative effect on their health. In no particular order, twelve of the most frequently discussed of these factors are:

1. Fatigue

2. Cosmic radiation and electromagnetic field effects

3. Circadian dysrhythmia; (their body clocks get out of time)

4. Depression

5. Responsibility for passenger safety and survival

6. Loss of career from airline failure

7. Loss of job because of professional errors

8. Losing your medical.

9. Excessive noise and vibration

10. Low humidity, ambient pressure and hypoxia

11. Airborne sickness and infection

12. Bad eating: airline and airport food.

Clarke’s findings, a number of further studies were conducted on the question of pilot life expectancy.

In a notable follow-up study, a far larger initial sample, being 2209 retired pilots and flight engineers, was surveyed. Early and late retirees were excluded from the sample, leaving 1494 pilots who retired at age 60 between April 1968 to July 1993. Comparisons were made with the census of the U.S. general population of 60 year-old white males. (The retired pilots were almost exclusively white males).

Various attempts have been made to research these specific factors to determine their effect on life expectancy. However, because of the academic requirement for complete anonymity and de-identification, that level of analysis of specific factors could not be achieved.

Despite the alarming findings from Mike Clarke’s study, IFALPA declined to speculate on the reasons for the large proportion of untimely deaths. However, in response to

Happily, the new research contradicted Clarke’s findings.

It found that a full 50-percent of the pilots in this study’s sample, who retired at age 60, were expected to live past 83.8 years, compared to 77.4 years for the general population of 60 yearold white males.

The study therefore concluded, with typical academic jargon, that the question of lowered life expectancy for airline pilots was not

supported by the results of ‘that particular data set’. This second study in fact determined that airline pilots’ average longevity was more than five years longer than their counterparts in the U.S. white male population.

The new study did much to reassure pilots that they should not expect to die soon after retirement. But Item 2 on above the list of things that pilots have to put up with, namely cosmic radiation, is receiving an increasing amount of attention.

Cosmic radiation is high-energy radiation generated in outer space. Organisations such as the South African National Space Agency (SANSA) are increasingly concerned about its effects on flight crew.

On average, around 10 per cent of all radiation exposure of the pubic comes from cosmic radiation. Everybody receives small radiation doses from cosmic radiation reaching the Earth’s surface. But the dose dramatically increases with altitude. The atmosphere attenuates cosmic radiation – so the higher you fly, the more you receive.

It is therefore an occupational hazard that aircrew (and frequent flyers) receive higher radiation doses from cosmic radiation than the general public, and astronauts receive even higher radiation doses.

Thus, space tourists can also expect to receive an increased dose from cosmic radiation, depending on the altitude reached and time spent at altitude. The two astronauts stranded on the ISS because of the Boeing Starliner failures have yet more reason to be unhappy.

Life on Earth is not just proteted by the atmosphere, but is also protected from cosmic radiation by the magnetic fields that surround the Earth.

How much radiation do air – and space – crews receive?

The stats are not very helpful. Less than 1 mSv a year is received on average by aircrew where all routes flown do not exceed an altitude of 9,000 metres (FL295). But for aircrew flying long-haul polar routes, a far higher 6 mSv a year is a typical radiation dose.

Even that is not too serious. For comparison: 20 mSv is the limit per year for people who are occupationally exposed to radiation due to their work, such as radiologists, which other studies have shown to have a shorter life expectancy

A study by the Pentagon has shown an elevated cancer risk for military aviators. The Defense Department examined health records for 156,050 pilots for the period 1992 to 2007 and concluded that military pilots were 24 percent more likely to be diagnosed with cancers than members of the general population, when adjusted for age, sex, and race.

I guess pilots and cabin crew should push their airlines for occupational health compensation. j

THE COVER STORY in the New York Times Magazine on September 22, 2018 was entitled, “What Really Brought Down the Boeing 737 MAX?” The writer, William Langewiesche, son of the sainted author of Stick and Rudder, is an experienced pilot and a thorough and technically savvy researcher of his wide-ranging articles and books. As you can imagine, I read it eagerly.

The article had been posted online a couple of days earlier. By the time I checked, it had garnered over 1,500 comments. I didn’t read all of them, but the reactions I saw seemed about equally divided between friendly and hostile to the writer.

I wrote a letter to the editor myself. It was not published. Despite the variety of online reactions, however, the letters to the editor that did appear two weeks later, were, surprisingly, all favourable. Did the editors consider the critical reactions not worth printing?

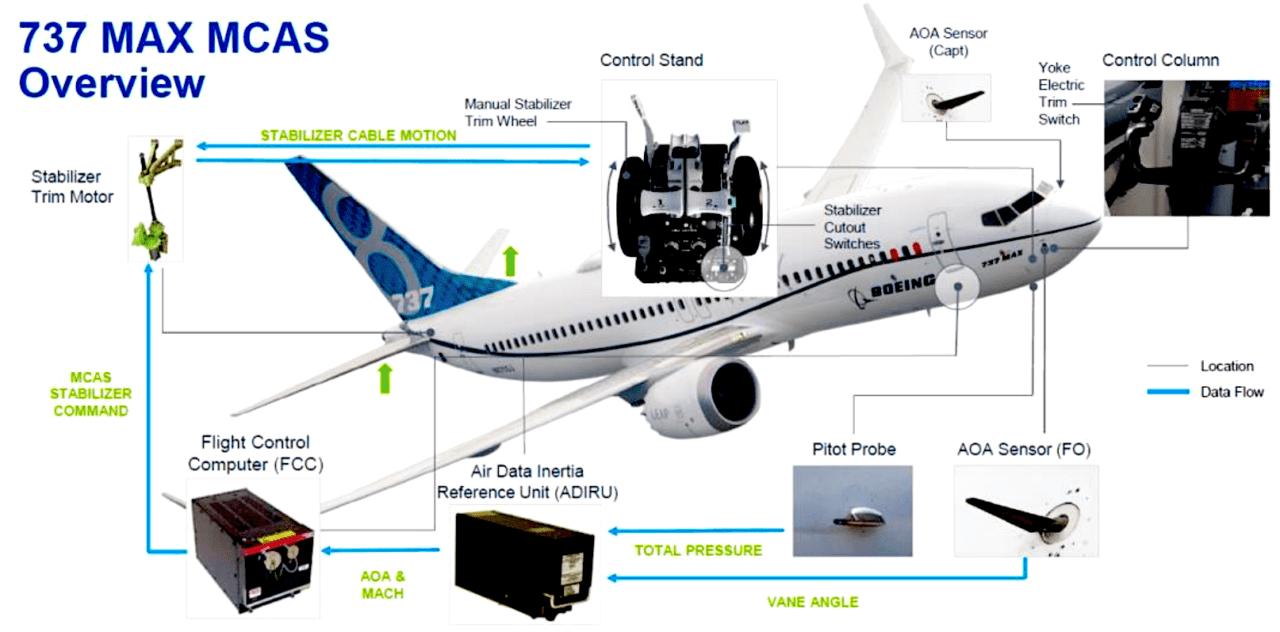

This is what Boeing apparently hoped any pilot would do in the event that the system, which applied nose down trim more rapidly than the normal trim system would, went off when it shouldn’t.

Langewiesche documented in great detail the combination of corruption, greed and irresponsibility that he said leads to the rapidly growing airlines of developing countries –notably, in this case, Indonesia’s Lion Air –putting novices fresh out of simulators into the cockpits of their jets.

What these crews lacked, he argued, was the wide experience in planes and flight operations of all sorts that enables pilots to react calmly and resourcefully to unfamiliar situations.

Langewiesche’s position, in a nutshell, was that the real reason for the two crashes, one in Indonesia and one in Ethiopia, that had cost hundreds of lives and led to the worldwide grounding of the airliner, was the poor airmanship of the crews involved. Properly trained crews, he argued, should have been able to disable their misbehaving stabilityaugmentation systems – the now infamous MCAS – in the same simple way that one would remedy a trim runaway.

Using cockpit voice and flight data records, he dissected second-by-second the reactions of the two crews to the pitch-downs that had been triggered, in each case, by a single faulty angleof-attack sensor. He showed how all four pilots failed to cope appropriately, one of them, in fact, turning to prayer as a last, and futile, resort.

Many online commenters branded the argument racist. It may have sounded that way, but I think, if Langewiesche was swayed by any unconscious prejudice, it was by a sort of class feeling: the belief of an experienced pilot, who

has logged many hours flying freight in junky aeroplanes and seen a thing or two, that old timers like himself are real pilots, and relative newbies simply aren’t there yet.

The refrain that young pilots “don’t know how to fly” is not infrequently heard from senior and retired captains. If it’s true, it’s not entirely surprising; just learning systems and procedures takes all of a new pilot’s training time.

The design philosophy underlying the Airbus flyby-wire system, in which the aeroplane, not the pilot, has the final say, signals tacit acceptance of this situation. Airbus airliners are not so much flown as managed. You tell the plane’s computers what you want; they do the actual flying. Software guardrails protect the aeroplane from clueless pilots.

Many American pilots, even those flying Airbus equipment, have professed to prefer the Boeing philosophy, in which the pilot can override the aeroplane rather than vice versa. Boeing aeroplanes, they said, were “pilots’ planes,” and Boeing pilots were real pilots.

By now no one can be unaware that the MCAS design was flawed. It was originally added to deal with changes in the 737’s longitudinal stability caused by the more forward position of new, larger engines on the low-slung jet.

Boeing management deliberately minimised its importance, almost to the point of concealment, in order to hurry the new model into service without its requiring re-certification or pilot re-training. Regulators, mainly the FAA, lulled by decades of reliance on Boeing’s competence and honesty, had not caught on.

Langewiesche conceded that Boeing had made mistakes, but passed lightly over them, expressing little more than mild puzzlement over the company’s actions.

I thought it would have been interesting to know as much about conversations that may have taken place in Boeing’s engineering and flighttest spaces as we know about what happened in the cockpits of the doomed planes. It’s hard to imagine that no one questioned the wisdom of allowing this powerful, fast-acting system to be triggered by a single faulty sensor.

Three weeks after the article appeared, the New York Times Magazine printed a single belated letter. It was from Chesley Sullenberger.

Sullenberger, whose successful ditching of a goose-disabled Airbus in the Hudson River has elevated him into a sort of Lindbergh for our time, was one of the pilots invited to re-enact the accidents on a full-motion simulator. He dismissed as an “age-old aviation canard” Langewiesche’s idea that the pilots’ airmanship, or lack of it, was to blame, though he agreed with Langewiesche that “inadequate pilot training and insufficient pilot experience are problems worldwide.” Still, Sullenberger wrote, “they do not excuse the fatally flawed design [of the] pernicious and deadly” MCAS, a “death trap” that should never have been approved, either by Boeing or by the FAA.

“Boeing made faulty assumptions,” he said, not only about the reliability of the system itself but also about “the level of human performance possible once the failures began to cascade.” Inappropriate MCAS activations “did not present as a classic runaway stabilizer problem.” The aeroplanes felt and behaved differently than they would have with runaway trim, and crews might

therefore look elsewhere for the cause, which Boeing had gone out of its way to hide.

Having more than once, in 50 years of flying, looked back with disbelief and embarrassment at my own reactions to in-flight emergencies and anomalies, I empathise with anyone who doesn’t reason accurately when failures begin to “cascade.”

My reaction to the article had been in some ways similar to Sullenberger’s. My own letter to the Times said, in part, “I have written an aeroplane accident analysis column for Flying Magazine for many years, and something I have learned is that no pilot or crew can be certain of their reaction to an unexpected emergency. If Langewiesche struggles to define the quality of “airmanship” that the accident crews supposedly lacked, it is because airmanship exists only after the fact. It knows no national boundaries. You can never tell who has the presence of mind to cope with unexpected and frightening events until the crisis is over. Because human performance is unpredictable, it is the duty of aeroplane manufacturers to provide crews with every possible advantage for coping with the unexpected. Boeing didn’t.”

j

At a recent conference an airline owner said,

“Airports are fundementally monopolies and as such are not suitable for private sector ownership unless there are rigorous checks and balances in place to prevent the users being overcharged.”

by Peter Garrison

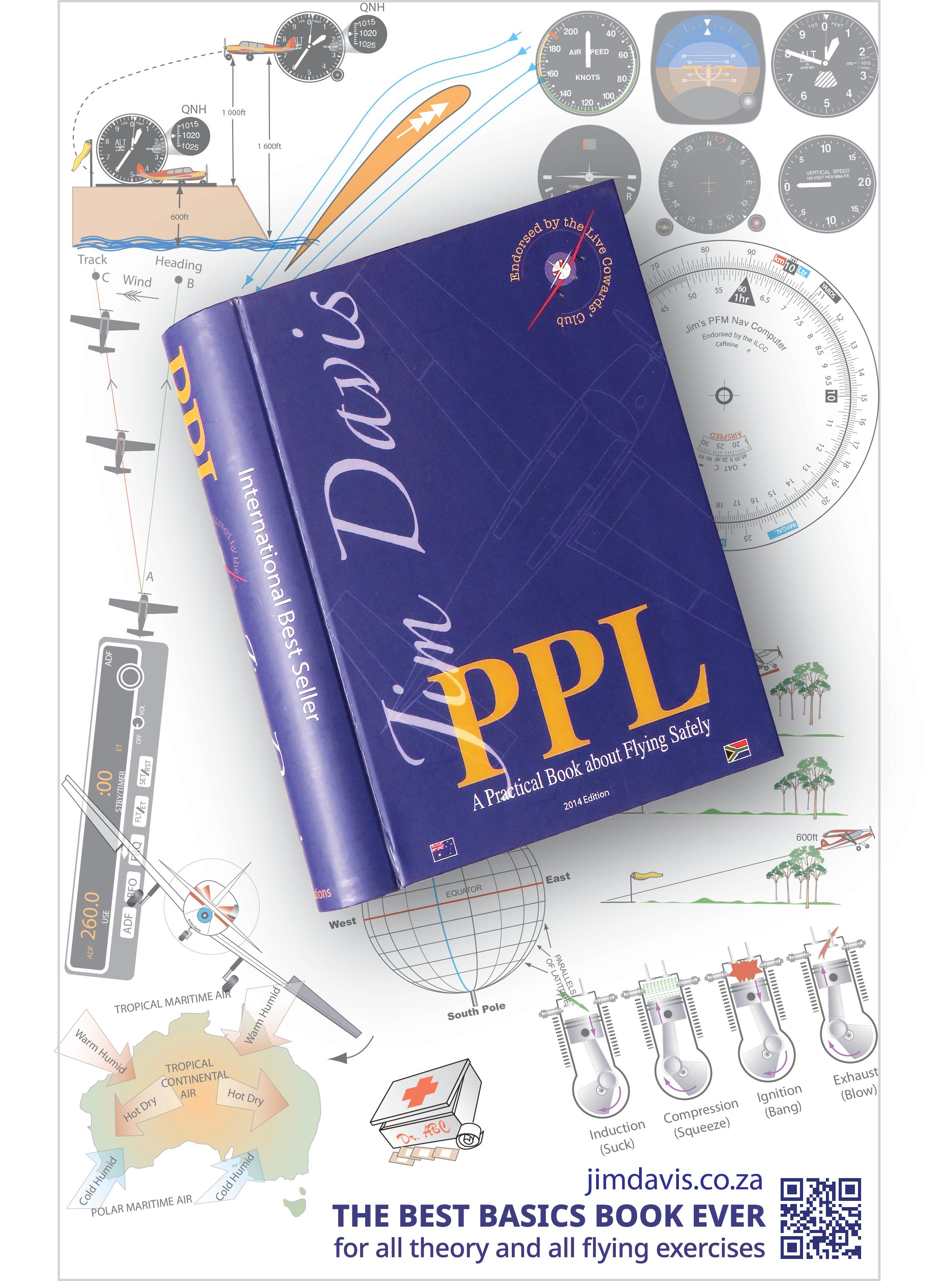

Descending is a remarkably complicated subject and us overworked instructors have to be able to field all manner of questions about it.

TO EASE YOU GENTLY into it – here’s the story about Joe’s picture. It was 1964 when I clambered on to an SAA Skymaster at Eros (Windhoek) for a flight to Keetmanshoop. The captain kindly let me sit in the jump-seat. Soon after takeoff he levelled off and asked me if I would like to descend to 1000’ below ground level. I had mixed feelings about this – he didn’t appear suicidal, but hell…

Anyhow he closed the cowl flaps, hauled the power back and stuffed the nose down for a flight into the mighty Fish River Canyon.

What a wonderfully thundering experience that was. It must have been one of the last of the barnstorming flights that airline pilots could occasionally get away with. Taking a dirty dive into a valley is now frowned upon.

Some years later I remember Scully Levin giving us a talk on what was involved in calculating the top of descent (TOD) in a modern jet airliner. He explained that it’s now a matter of pride for airline pilots to pull the power fully back – roughly a hundred miles from destination, and only use it again for taxiing.

The big radials that had been hammering out close to 6000 hp, fell silent, but for the occasional bang and boof from the exhausts. It was a magnificent, calm, clear morning – not a bump in the sky.

The previously benign captain, an ex-SAAF guy, adopted the wild and gritty look of a Brooklands Bentley driver. He took a feverish grip on the string-bound yoke as he wrestled 35 tons of machinery into unbelievable bank angles and then heaved back so we all sank deep into our seats. This was necessary to negotiate the twists and turns of the canyon. I had to wonder how the pax enjoyed the roller-coaster ride.

Actually that’s not quite true because they need to use a fair amount of thrust on final to maintain the glide-slope in the landing configuration; and in case of a go-around. But you get the idea – it’s a glide approach to a field that’s out of sight over the horizon.

So why glide? Well first, they are recovering some of the time and fuel they used in the climb. Second, jets are unbelievably thirsty at low altitudes, so a powered descent – like we use on cross-countries – eats into fuel reserves, and the airline’s balance sheet. And finally, it makes sense to stay above the weather as long as possible to give everyone a smooth ride.

Why did Scully carry on about how difficult it is to work out a precise TOD? Well, because you have to take into account the forecast winds at various levels during the descent. Then you don’t know exactly how far you are going to descend.

Sure you can use the DME – but that only gives the distance to the beacon – so you need to estimate your own track miles and make allowance for the circuit. Next, you need to keep a sharp ear out for any other traffic that might conflict with your immaculate plan. And finally when you have it all figured, ATC changes your routing.

Technology has taken some of the grind out of this. Now, on your Nav Display, you have a VNAV profile which puts a nice little icon on your track to tell you when to become a glider. Actually it tells the auto-pilot, so you sit on your hands and watch das blinkin-lights while it all happens on its own.

Out of interest, a normal glide in a 737-800 is at around 280kts indicated. Then at 50 DME it must come back to a max of 250 kts. Then 210 kts at 15 DME. Your end-of-decent point is usually, where you intercept the glide-slope on the localizer. This is normally at 8 miles, or about 2500’, where you should be at 180 kts or less.

Electronics have largely taken the guesswork out of this, but the surprises come when ATC suddenly changes your routing. They may give you a short-cut in which case you must instantly increase your rate of descent. Or they may give you speed or altitude restrictions.

So it often becomes the big deal Scully was talking about.

A quick sidetrack. I was coming back from London one night in an A340. We were working our way round the tops of some Charlies that were causing turbulence and lightning just south of Paris. The Captain, who was an ex-pupil of

mine, explained that if he typed the new track into his magic box; the MCDU (pronounced macdoo), the autopilot would simply follow this around the build-ups.

Then he pointed to a knob on the MCP – Mode Control Panel on the glareshield, and said, “Of course I can fly it manually by turning this.” He was serious.

When I taught him to fly a Cessna 150 in Port Elizabeth, I’m sure we used to associate manual flying with working the levers and pedals. Silly me. To him, manual flying now means twiddling a knob.

You may remember that on 1 April 2010 a young charter pilot was descending from FL95 into Swakopmund in a Cessna 210. Apparently, without warning the aircraft suddenly came apart and the separate bits variously fluttered and plummeted down over a large chunk of territory.

Two months later a pilot and his navigator were descending their Flamingo towards an air-race checkpoint near Bella-Bella when it also broke up in flight.

Anyhow let’s get back on topic and look at descending in proper aeroplanes with propellers and pistons.

Unfortunately, before we look at the various ways you can descend, I must tell you about a nasty called flutter. This is because any descent has the potential for increasing airspeed –possibly to the extent that it can cause this lifethreatening condition. So here we go.

From pilot reports no significant turbulence existed in either case. Aerodynamic flutter, caused by excessive speed, had been the culprit in both events.

Now I have just read that Jimmy Leeward’s Mustang crash at Reno was caused by worn locknuts on the elevator trim. These allowed flutter to develop. The trim failed and subjected the aircraft to +17G, which incapacitated the pilot.

Both of the South African pilots seem to have been doing what we all do – using the descent to make up for speed lost in the climb. We like to think we are safe as long as we keep below Vne – the red line.

Sorry folks, this is not necessarily true. If you want to let the ASI needle move towards the business end of the dial you had better understand exactly what’s going on. It’s a complicated subject which I have covered Before. The Gleitch won’t give me the space to go through it all again, but here are the basics:

Flutter is what your washing does in the wind. Under the right circumstances parts of your aircraft can do the same. It might be a trim tab, an aileron, a tail-plane, or a whole wing. It can be anything from an almost unnoticeable buzz, to a major terrifying event which shakes the aircraft so violently that it rips itself apart. It may last for several seconds, or for only a fraction of a second, before it causes a catastrophic failure.

When the conditions are right the slightest thing may start it. It could be minor turbulence, or a twitch of the control column, or almost nothing.

To further complicate matters, flutter depends on TAS (True Airspeed) – NOT the indicated airspeed you are looking at on the ASI. This means that a particular indicated airspeed on your dial might be quite safe at sea-level but lethal at 12,000 ft.

Fortunately, unmodified, everyday aircraft, in good condition, have a decent safety margin built into the Vne limitation – as long as they are flown within their certification limitations – including maximum altitude. However any sloppiness in the control system can cause flutter at speeds well below the red line.

There is a whole set of complicated, and sometimes vague rules for gliders at high altitude. And other rules for NTC (Non-Type Certified) aircraft.

That’s just a general warning that any descent has the potential for increased airspeed – so keep that in mind when you plan to go downhill.

Basically you have two ways of making the aeroplane descend.

• You can glide

• You can descend with reduced power.

Instructors, please teach your pupil to glide. Ideally, demo it on her first flight. Then keep doing it as often as you can. This is pure flying. It’s the most elegant form of flight. It teaches her airspeed control. It teaches her judgement. And it teaches her that flight is about aerodynamics –not about engines. You want her to understand in her soul that an engine failure is an inconvenience – not a death sentence.

In Jim’s ideal flying school you will do glide approaches for most of your flight training.

Those of you who learned to fly when there was less traffic, and the plugs didn’t foul every time you closed the throttle, will remember that those wonderful glide approaches were the normal way of doing circuits and bumps.

gentle landing near the beginning of the grass runway. No tar, no VASIs and no PAPIs.

Sideslipping was a normal part of any approach that was too high. We will deal with that wonderful skill a bit later.

If you had used carb heat – we generally didn’t need to on Cherokees – you would put it off at about 100ft.

After a bit you got pretty good at glide approaches. So when they started teaching you forced landings – well you really couldn’t miss. Forced landings usually call for a longer glide, so you have to warm up the engine, and give it a blast of carb-heat, every thousand feet or so. You should also close the cowl flaps, if you have them.

Okay, so here’s the way we should teach students to start a glide:

You did a standard circuit, but when you turned on to the base leg you didn’t throttle back to start your descent. You maintained circuit height until you judged that you could easily glide for a touchdown a couple of hundred meters into the runway. You kept a beady eye on the runway and watched the drift in order to judge the wind. When the time was right you used carb heat and throttled fully back. You also used a touch of left rudder to keep the ball in the middle and you held the nose level until you reached your glide speed. Then you lowered it into the glide attitude and trimmed any pressure off the stick.

When you realized you were a bit high you would use some flap to steepen the glide. You progressively used flap. Each increment would steepen the descent to bring you down for a

• Make sure there’s no conflicting traffic

• Use carb-heat if the POH recommends it

• Richen the mixture

• Smoothly come all the way back on the throttle

• Use enough left rudder to keep straight

• Hold the nose in the level flight attitude

• When the airspeed reduces to the best glide speed lower the nose into the correct attitude

• Trim the pressure off the stick

• Relax and enjoy the sensation of pure flight

To maintain the glide:

• Keep a good lookout for traffic

• Don’t look away from your aiming point for more than a few seconds at a time

• Remember engine warm-ups and carbheat

To recover:

• Put the carb-heat off

• Richen the mixture

• Smoothly apply full power

• Use enough right rudder to keep straight

• Raise the nose into the level flight attitude. In some aircraft at large flap settings you may need to use a huge amount of forward force on the stick to prevent the nose from moving above the horizon

• When you reach cruise speed reduce power and adjust attitude accordingly

• Tidy up – trim, mixture, power-setting and cowl-flaps.

Descent with reduced power.

This will be your normal descent to destination – say on a crosscountry.

The question is where, when, and how much, should you reduce the power.

ears-popping, shock-cooling and excessive speeds.

First let ATC know you are at TOD. Richen the mixture a bit, ease the nose down a fraction, let the IAS increase by 15 – 20kts. Come back slightly on the throttle to prevent the revs running away. When everything is settled - trim the elevator and the rudder.

Keep an eye on the engine all the way down –tweak the mixture a tad richer every thousand feet and make sure the revs stay where you want them. As you get lower, any particular rev setting produces more power than it did at altitude. So you need to gradually reduce the revs during the descent.

Ideally I like to plan a normal descent to destination on a cross-country at a bit over 300 fpm. This gives you a reasonable increase in airspeed without running into the yellow on the ASI. It’s also nice and easy to work out your TOD – you are going to take about three minutes for each thousand feet.

So if you are descending to Virginia from say FL 95 you need to lose about 8500’, to get to circuit altitude. This should take you around 25 minutes.

If you normally true out at say 120kts, you can probably work your descent at a TAS of around 140kts. Which means you would start your descent 60nm short of Durban. These are thumb-suck figures – they can’t be exact because of winds and so on.

It is common for new pilots to misjudge this and start their descent way too late. This means

If you expect to be distracted by nav, traffic or pax, give the mixture an extra dose of richness – you don’t want a lean cut at low altitude. Also remember carb heat. I have had icing in a Cherokee 235 on the Natal coast when the OAT was over 35°C. It’s the humidity that does it.

And finally, let’s quickly sort out a long standing discussion. In piston-engine aeroplanes we control the airspeed with the elevator and the rate of descent with the throttle. I did touch on this earlier, but there’s a bit more to it.

Jet pilots do it the other way round, and there are good reasons for this. Briefly, because they are so heavy and carry so much inertia, it takes too long for changes in nose attitude to alter the airspeed. If they want to go faster NOW, thrust is what will do it for them.

Back to our sort of aeries, the only time you will ever break this stick-for-speed/power-forheight rule, is if you are low and slow on final approach. Obviously you can’t put the nose down to regain airspeed – so you have to use power. But this is not really something you need to think about – it just comes naturally.

Next time we will look at climbing and gliding turns and the disappearing art of sideslipping.

j

We elevate the ar t of aviation design to new heights. Our innovative approach blends cutting- edge technology with timeless elegance, transforming aircraf t into personalized sanc tuaries of comfor t and style. From bespoke seating & advanced cabin layouts to exquisite liveries, we craf t ever y detail to ensure your journey is as ex traordinar y as your destination.

Liver y Design

Photorealistic 3D previews

Photography

Day and night, the fun doesn’t stop!

Our catered camp site on the airfield means you won’t miss out on any of the activities – the early morning wake up call of P 51’s getting airborne, the evening ultralight parade, the STOL competitions and of course, the incredible night airshows! Plus all the camaraderie and fun only a camping group can offer.

Our campsite offers you a home from home at Oshkosh, tents and bedding, meals and beverages, charging facilities and sheltered seating – no camping gear required, bring only your clothes!

Tours depart Johannesburg, Durban or Cape Town Friday 18th July and return Tuesday 29th July 2024.

Prices from R40 650, Early Bird specials available!

Guy Leitch with Goitseona Diale

Pipistrel is a phenomenon. Despite coming from a country few people could find on a map, and burdening their planes with ridiculous names, Pipistrel have become world leaders in light sport aircraft – and they fly the pants off the competition.

Pipistrel’s Explorer is the latest, and undoubtably the most developed, version of the Slovenian plane builders’ incredibly successful Virus range.

The Sinus and the Virus were introduced to South Africa in 2003. Based on the aircraft’s reputation, there has been stiff competition for the Pipistrel agency –which is now in the hands of Absolute Aviation at Lanseria.

an autopilot, dual redundant ADAHRS units and airbrakes.”… it is the fastest, most capable and the most economic aircraft in the CS-LSA category. Its speed performance allows it to fly at IFR speeds in/near complex airspaces and procedures, so it can be used for private

The Explorer is at heart a Pipistrel Virus which has been fully updated –and certified. It is the certification that makes what was already a remarkable plane even more useful and attractive.

Pipistrel claims that the Explorer is “the first and the only EASA Type-certified aircraft in the CS-LSA category approved for night VFR operations, intentional spins and glider-towing, the only one with

use and training also at busy airports next to airliners, without slowing down the other traffic.”

Pipistrel also says that the Explorer is the first small aircraft in history to be type-certified with 3D printed parts.

As a certified plane it is aimed at the training market. Pipistrel says that it can

The Explorer has an amazingly powerful avionics fit as standard.

be used as a simple ab-initio trainer and for more advanced systems – such as an MT constant speed prop, negative flaps, airbrakes and autopilot. The instructor can progressively increase complexity by adding the systems and options which the aircraft is certified for.

Pipistrel allow the owner to personalize their planes and thus offer a range of certified engine options - from the 80 hp Rotax 912 to the fuel injected Rotax 912-iS.

Unusually for this type of installation, Pipistrel mounted the coolant radiator above the engine, which gives a distinctive tall nose profile.

The Explorer is also commercially certified for glider towing which makes it very useful for clubs as an all-in-one aircraft and a great platform for pilots to build experience.

Safety is key and the Explorer incorporates a haptic stall warning system. This is essentially a system that alerts the pilot to an impending stall by vibrating the control stick. A ballistic parachute adds the ultimate fall back when all else fails.

The wing’s the thing.

The Explorer’s genesis can be traced back to the Sinus motor glider, whose wing is an aerodynamic marvel. Not only is it a super-efficient laminar flow wing, but like South Africa’s JS1 sailplanes, it uses different profiles along its span to improve the handling characteristics.

Testimony to the soundness of the design is that it won the first prize of US$100,000 in the NASA CAFÉ (Comparative Aircraft Flight Efficiency) competition for all-round performance, including climb, speed, economy, controllability and noise levels.

The Explorer has a wingspan almost two metres shorter than the standard Virus, but it is still lengthy at 10.7 metres and glider-like in its high aspect ratio. The tail is surprisingly high at over 2 metres above ground, which makes it tricky to inspect.

Even though the shorter wingspan is the most obvious change to the standard Virus, there are other less evident enhancements. The empennage is smaller and most importantly, under the skin it has been seriously beefed up to cater for higher speeds. This has meant that the Vne (never exceed speed) of the Explorer has been raised to a healthy 163 KTAS or 302 km/h.

The strengthening of the basic structure is so extensive that, despite its almost identical appearance with the standard Virus, the Explorer’s fuselage structure was redesigned from the ground up. Much of the skin is now built out of honeycomb material. Another indication

of the stronger structure is the two braces behind the windscreen, between the firewall and wing spar box, whereas the Sinus and standard Virus only have one brace.

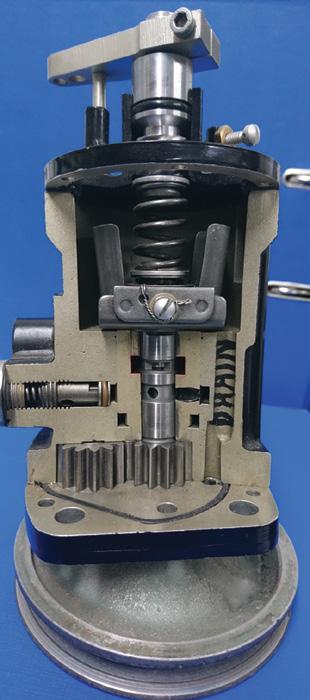

The Explorer with the 100 hp 912ULS Rotax drives a hydraulic constant speed MTV-33-1A 2-blade prop which gives both great takeoff performance and ground clearance.

The engine is easily inspected through a hatch on the side of the cowl. For a more detailed look the entire cowl comes off in a minute with Dzus fasteners. Many consider it sound practice for the first flight of the day to ‘burp’ the dry sump oil system by turning the prop through a couple of revolutions.

There is a good-sized baggage space behind the two seats rated for a useful 25 kgs of bags. This can be accessed through a small baggage bay door on the side of the fuselage. There is now a solid bulkhead between the cockpit and baggage bay so the headrests are more firmly mounted on the bulkhead, which also holds the headset jacks. The seatbacks can be removed to access the baggage bay from the cockpit.

Our test aircraft ZS-FSC (note the ZS registration!) has a ballistic parachute fitted and this intrudes on the available space in the baggage bay behind the right seat.

Explorer’s utility. But it is more than capable of carrying a load for training.

The fully faired wheels feature quality Beringer brakes which are easily inspected. Regular operation from rough strips would make the removal of the wheel fairings worthwhile. Once seated, when the Battery Master Switch is turned on, an unusual feature is that the haptic stall warning buzzes the stick three times in a self-test.

Each wing has a 50 litre fuel tank which can be reached from the ground by people of at least average height. So you don’t need to carry steps around as many Cessna pilots do. The 100 litre fuel capacity typically gives a 5 hour endurance, so is more than sufficient for most missions – and it happily drinks mogas, which is more readily available than avgas.As an LSA the max all up weight is limited to 600 kg. ZS-FSC has an empty weight of 370 kg, giving a 230 kg useful load. A 90 kg pilot and 80 kg pax leaves just 60 kg for fuel and bags. Assuming 50 kg for fuel, that is 67 litres. Two standard South African males with 10 kg of baggage will compromise the fuel load but can still fly for three hours. An increase in the 600 kg MAUW for the South African market, and the pending implementation of MOSAIC in the USA, will give a much-needed boost to the

The two transparent doors fold up against the lower surface of the wing and are held in place by a simple clamp.

It is not necessary to stand on a wheel spat to get in, you simply slide your butt onto the seat and then lift your legs into the cabin, hoisting one over the short control stick.

I found the seats very comfortable as they have excellent lumbar support. As the seats are fixed the rudder pedals are adjustable. Both pilot and passenger have toe brakes and a look under the instrument panel shows a reassuring quality of the fittings.

A big thing about the Explorer is that it has a high wing, but this is not particularly evident in the narrow but tall cabin. Once seated you may notice

the wing main spar, which looms across your forehead. But as with the two vertical braces across the windscreen, the spar soon ceases to intrude.

A high wing allows a good view of the ground, which is great for pleasure flying but it still suffers from poor view into turns, although Pipistrel go some way to alleviating this with a large transverse roof window. The view down is greatly enhanced by the transparent doors. An efficient fresh air system and cabin heater is standard.

The Explorer uses dual sticks with a single throttle and pitch control between the two pilots. This layout is ideal for training and it’s good to see that Pipistrel have not gone the cost-cutting route of installing a single centre-mounted stick. Behing the power controls is a large trim switch and ladder indicator and behind that the direct acting and simple ‘Armstrong’ handbrake style flap lever so familiar to Cherokee pilots.

The Explorer has plenty of space in its high and wide panel for the very comprehensive avionics fit, more befitting a bizjet than an LSA. The panel layout is straightforward, with pride of place top centre of the avionics stack being the very capable Garmin GMC-507 autopilot. On either side of the stack there are

two portrait oriented certified Garmin GDU-470 7-inch multifunction displays (MFDs), which can operate in split-screen modes and thus function as primary or secondary flight displays. Nav input comes from a Garmin GNC 355A which is WAAS enabled. Further nav input comes from GNC 255 navcom. A Garmin GTX 345 Transponder is standard so the aircraft is ADS-B compliant.

The auto trim system is connected to an angle of attack sensor on the pitot tube and automatically adjusts the trim. For flying schools, the trim system can be switched to manual and operated by a conventional conical hat on the stick.

Like all Rotaxes, the Explorer’s 912 engine bursts into life enthusiastically, but with the 912’s characteristic gearbox clatter.

Taxying is easy. Nosewheel steering is direct and the brakes sufficiently powerful and easy to use. Both seats have brake pedals. The wingtips are however hard to see and looking at the position of the shadows is a good way to check if there is wingtip clearance.

Another factor behind the Explorer’s clean design is that the windscreen is some distance ahead of the occupants. It is steeply raked and, with a high instrument panel sill, restricts forward visibility somewhat.

For straight and level cruise the flaps can, glider-style, be selected a further notch up – to negative five degrees, which has the effect of reducing the wing’s angle of incidence and thus attack. You can almost imagine the wing and indeed the whole Explorer high tailing it as it slices through the air.

The cabin noise level is pleasantly low, which creates the impression that the Explorer is lacklustre in climb and cruise speed. But a glance at the vertical speed and airspeed indicators quickly dispels this.

For takeoff the flaps are set to +1. Unstick speed is 43 KIAS and rotate after an impressively short ground run of around 250 metres at about 50 KIAS, depending on density altitude.

Unlike some T-tails, the elevator is smoothly effective on rotation. At 70-80 knots the flaps are raised to zero.

Climbing one-up through 5500 ft out of Lanseria routing for Durban’s Virginia, in a cruise climb at 70 knots the Garmin showed a climb rate of 1100 fpm. This is impressive, given that there was four hours’ fuel plus assorted stuff in the baggage bay.

In cruise the controls are well harmonised and responsive, especially the elevator. Control break-out forces are reasonably light, despite the full span flaperons. Whilst the Explorer takes its time to accelerate, it does not like to slow down.

As a minor criticism, the rudder lacks positive feel and so it is important to maintain the ball in the middle. But this makes it a good trainer.

Flying at an unusually high FL115, with just 55% power, Goitseona saw 98 IAS for 120 TAS at 6500 feet, full throttle and 5400 rpm, the Garmin PFD showed 125 KIAS for 137 KTAS, burning just 20 litres per hour Mogas. Even at that speed it flies impressively smoothly and quietly. With fixed gear and just 100 normally aspirated ponies, this is a great turn of speed.

The downside of a slippery laminar flow wing is usually found in the stall behaviour and the Explorer is no exception. Lowering flaps to Position +2 with the power off and the nose almost level with the horizon, there is an aerodynamic buffet plus the haptic stick feedback at 49 KIAS before the right wing dropped. As the Explorer is certified for intentional spins, this will further enhance its appeal to flight schools.

With the clean airframe, descent planning is important. It’s easy to end up a bit high and fast. Full flap in combination with the airbrake is typically used for landing. With the prop full fine and the power closed (there’s no risk of shock cooling on the Rotax) you use your right hand to reach up and unlatch the airbrake lever. This allows precise glider like hold-off and touch downs.

The Explorer is easy to land, but once the airbrake is applied on final, the sink rate can get high without judicious use of power. Thankfully the Explorer’s clever auto trim system, geared to the pitot’s angle of attack indicator, makes retrimming easy.

The approach is flown at a brisk 65 knots with flaperons at position 2. An idiosyncrasy not uncommon to flaperonequipped aircraft (and Robertson STOL conversions), is that with full flap the ailerons load up at slower speed and require more effort to roll the aircraft. It is only in the approach phase that pilots will encounter this, and it is by no means a disadvantage as this natural resistance will discourage too high an angle of bank when turning onto final.

Thanks to the airbrake, the float is minimal. With judicious use of the wheel brakes you can easily get stopped after just 60 to 70 metres’ ground roll.

Specifications & Performance

Engine Model: Rotax 912 S3

Max Take-off power: 100 hp

Max Fuel Capacity: 26 usg (100 litres)

Max Take-off Weight: 1320 lb (600 kg)

Typical Empty Weight*: 835 lb (370 kg)

Useful Load: 495 lb (230 kg)

Wingspan: 35.1 ft (10.70 m)

Length: 21.1 ft (6.42 m)

Height: 6.82 ft (2.08 m)

Performance

Takeoff 50’ Obstacle (MTOW): 1050 ft (320 m)

Max Climb Rate: 1050 fpm

Max cruise speed: 133 KTAS at 10000 ft

Max Range (65% power 4000 ft): 625 nm (+30 min reserve)

Max Endurance (65% power 4000 ft): 5hrs 33 mins (+30 min reserve)

Stall Speed w/flaps: 47 KIAS

Take off Roll: 150m

Landing Roll: 120m

The Explorer has taken a well proven design – the Virus SW – and equipped it to the most modern standards.

The avionics fit makes it a most capable aircraft and especially useful as a trainer. It would be great if Pipistrel can persuade the SACAA to approve a 700 kg version. j

Aircraft registration: ZS-LVC

Date of accident: 8 April 2004

Time of accident: 0730Z

Type of aircraft: CESSNA T210N

Type of operation: Acceptance/test flight

PIC license type: PPL

License valid: Yes

PIC age: 45

PIC total hours: 200.0

• This discussion is to promote safety and not to establish liability.

• CAA’s report contains padding and repetition, so in the interest of clarity, I have paraphrased extensively.

PIC hours on type: 115.0

Last point of departure: FAGM

Point of intended landing: FAGM

Location of accident site: Field Near N59 Highway

Meteorological information: CAVOK Temp +17

POB: 1

People injured: 0

People killed: 0

Synopsis:

THE PILOT/OWNER DEPARTED from Rand Aerodrome on an acceptance/test flight after a MPI was carried out on the aircraft.

The pilot stated that during the flight, he recycled the landing gear to check the landing gear operation and operated the ailerons (rocking the wings up and down) when the engine suddenly failed. He then changed the fuel tank selection and restarted the engine. The engine started briefly but then failed again.

As he was committed to carry out a forced landing, he decided to execute a forced landing on a slightly rough but open field with the landing gear retracted. The aircraft skidded for approximately 100m on the grass and ground looped through 90 degrees before it came to rest.

The pilot was not injured during the event and the nose landing gear doors, nose under surface and propeller blades were only slightly damaged.

According to the pilot, he did not uplift additional fuel into the aircraft or visually check the level in the fuel tanks as he was of the opinion that there was sufficient fuel available for a flight of approximately 15 minutes. The left and right hand fuel quantity gauges indicated approximately ¼ full.

Periodic inspection (MPI) prior to the Incident was audited by the Airworthiness Department on 07 April 2004 and no major findings were noted.

The last MPI was carried out 8 April 2004 at 3284.2 hours and the aircraft had accumulated an additional 0.3 hours at the time of the incident since the MPI. The Aircraft Maintenance Organisation who certified the last Mandatory

The engine stopped due to fuel starvation when the fuel tank outlets were uncovered by fuel when the pilot manoeuvred the wings up and down with the ailerons during the acceptance flight with fuel quantity at a low usable fuel level.

JIM’S COMMENTS

I COME FROM AN ERA when teachers told us, very publicly, when we had stuffed up, and hurled blackboard dusters at our heads. And that wasn’t for destroying expensive machinery and endangering lives, it was for failing to conjugate a Latin verb correctly.

There was a time, before all this woke nonsense, when it was perfectly normal to say what had caused an accident, and to speculate.

Overloading, alcohol, incompetence, poor training and crappy maintenance were all subjects on the agenda sheet for open debate.

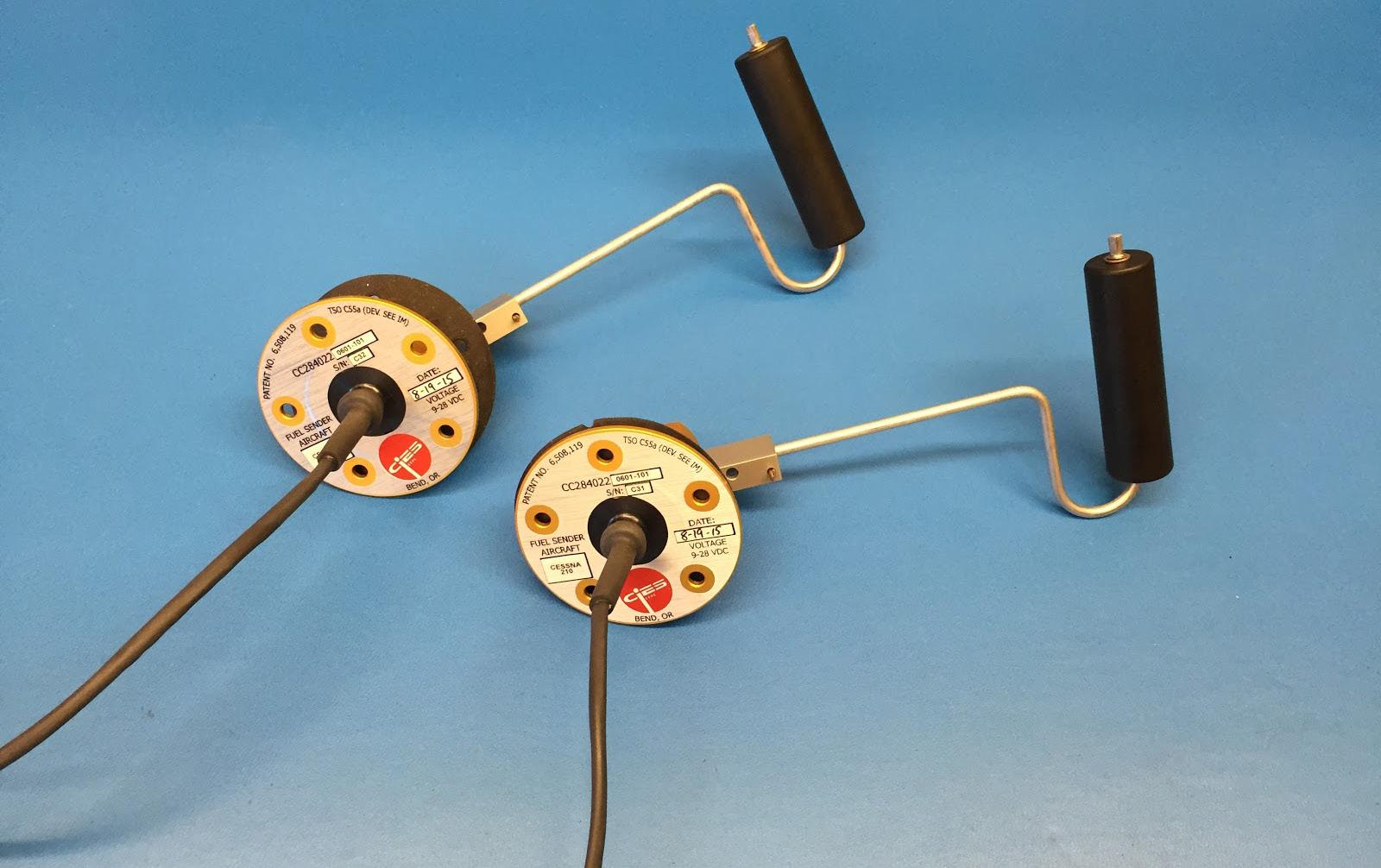

Fuel tank senders are notoriously unreliable.

Us newbies learned a lot by listening to these discussions and speculation. Nobody was going to take offense or legal action.

Now we have to be careful not to discuss how pilots or engineers killed people in case we upset them. Grrrrrrr.

So I am not going to pussy-foot around the lies, stupidity and incompetence surrounding this idiotic accident.

Fortunately, no one died. The pilot and AMO are not named and it all happened 20 years ago, so I hope feelings have calmed down, because I am going into wild speculation mode.

Who, in their right mind flies an aircraft without doing a preflight inspection? I guess the answer is no one. So it follows that the pilot was not in his right mind. He behaved like an idiot and was lucky not to have killed himself when he starved the engine over a built-up area.

But this leads to an interesting discussion. What exactly is a preflight inspection? I always teach

that it’s a silly abbreviation for a pre-every-flight inspection. When you are training people, this is the safe and sensible thing to teach. But we have all done abbreviated versions which common sense seemed to indicate were okay.

If you are on a four hour flight in a wellmaintained aircraft, and you land for a pee-break after three hours, are you really going to do a full preflight, or even sample the fuel? I would certainly check the fuel and oil levels and make sure there were no oil leaks or flat tyres, and then be happily on my way.

Legal? Perhaps not.

Safe? Almost certainly

But how about this oukie? If he doesn’t do a preflight after an MPI, when does he ever do one? To me a post-maintenance preflight has to be the most thorough one you ever do.

Hell, think about it. The guys who have been swarming all over your aircraft and pulling it apart, are not necessarily engineers. In fact they

may be appies who have never even seen your type of aircraft before. Yep, it’s the engineer’s job to make sure all the work is done correctly and signed for. But I try not to consign my life to strangers.

Put it this way; I never trust the refueller to put the fuel and oil caps on properly – and I hope you don’t.

You may remember the Centurion that took off from Wonderboom with a family of four on board. Soon after takeoff they spun into the ground killing everyone. It turned out that the refueller hadn’t put the oil cap on properly. When it came off, the windscreen was instantly blackened with oil. The pilot, who could see nothing, got such a fright he stalled while turning back to the field.

your fuel tanks. And where do the appies who serviced your aircraft get fuel for their cars and motorbikes – that’s right. So the longer your aircraft is in the AMO the less fuel is in the tanks.

And if the aircraft has to be weighed – they have to record the empty weight – which means without fuel. So the guys at the AMO have to drain your tanks. Ideally they would be drained into spotless stainless steel containers with covers on, and then every drop returned to your tanks after the weighing… hmmmmm…

And think about this. When you collect your aircraft after they have serviced it – it’s all nice and clean in the engine bay. Where do you think the cleaning material came from? It’s from

And who trusts their life to dicky fuel gauges that are reading around ¼?

And while I am speculating, who has exactly 200 hours? Remember when you started flying you proudly recorded hours to the nearest tenth. Most of us do that throughout our careers, but some greybeards with thousands of hours get a bit slack and round things up or down to the nearest half-hour – or perhaps even a whole hour on long-haul flights.

Anyone who writes in an accident report that they have exactly 200.0 total hours is either meticulously conscientious in recording this coincidence, or just a bit too bloody casual. And given the fact that he didn’t do a preflight I would suspect the latter.

And is it another coincidence that the AMO just happened to have been audited by the CAA’s Airworthiness Department one day before the accident? What’s that smell?

In the olden days when everything was blackand-white, and we learned to fly from grass fields in little aeroplanes with five instruments, 40 hours was deemed sufficient to earn a PPL. And 200 hours in little aeroplanes with a dozen instruments and two radios was generally enough to train a pilot to fly safely in uncluttered skies in decent weather.

Now I have to wonder how many hours you need to feel really comfortable barrelling through complicated airspace at 200 mph with flaps, retractable gear and a constant-speed prop while fiddling with a stack of avionics and a micky-mouse autopilot. Perhaps somewhere between 500 and 1000 hours? I don’t know.

But if this guy’s figures are to be believed, he converted to just such an aeroplane when he had 75 hours. Would you have happily consigned your loved ones to the back seat of his complex aircraft when he had less than 100 hours. Maybe it’s just an LCC thing.

Final thought – I believe that an instructor who signs out a brand-new low-hour pilot to fly a complex aircraft in a high density traffic environment is pushing his luck. Put it this way – if the airforce was converting a new pilot to a complex aircraft they would have him in the classroom for the best part of a month before he ever saw the aircraft – and he would probably have to do around 40 hours of dual in that aircraft.

Take home stuff:

• If you are the PIC please don’t trust anyone else to ‘help’ with the preflight, or the refuelling, or the removal of chocks, or the control locks, or pitot cover.

• Don’t let yourself fall into the category of too many Rands and too little sense. j

OPERATING FROM GRAND CENTRAL Airport in Midrand, Superior Pilot Services prides itself in its wealth of knowledge and experience in the aviation sector, offering a variety of certified courses, from the Private Pilot’s Licence to the Airline Transport Pilot Licence, Instructor’s Ratings and Advanced training. The school specialises in personal outcome-based training and combines the latest techniques, methods and training aids to maintain a high level and standard throughout. Superior is proud to have been selected as a service provider to numerous institutions like, TETA, Ekurhuleni Municipality, KZN Premiers office, SAA, SA Express and SACAA cadets, however their ideally situated location allows the general aviator and businessman to conveniently access and utilize the same services.

With highly trained and qualified instructors and a fleet of Cessna 172s, a Cessna 182, Sling 2, Piper Arrow, Piper Twin Comanche and R44 helicopter, the school has the know-how and experience to prepare the best pilots in the industry. Making use of a state-of-the-art ALSIM Flight Training Simulator, the Superior Aviation Academy offers unmatched facilities that ensure students’ social needs are catered for and that the training offered is at the forefront of international training standards. The Alsim ALX flight simulator model provided by Superior Pilot Services is EASA and FAA approved and has proven itself worldwide. It provides up to four classes of aircraft and six flight models that cater from ab-initio all the way to jet orientation programmes in one single unit available 24/7.

The school offers a range of advanced courses, including IF Refresher Courses, Airborne Collision Avoidance System (ACAS), GNSS/RNAV, CRM and Multi Crew Coordination (MCC) conducted by its qualified instructors. The school also offers PPL and CPL Ground School and Restricted and General Radio Courses. Superior Pilot Services has accommodation available. The lodge is conveniently located just six kilometres from the airport. All rooms are based on a bachelor’s unit which includes laundry and room cleaning services as well as breakfast. Students have access to the communal lounge, gym and entertainment room, pool and ‘braai’ area.

This Cessna 337 is now ZU-NVG and a noncertified aircraft. Image Rui Sequeira.

July’s register review sees some interesting additions and unfortunately quite a few aircraft exported too.

WE START THIS MONTH with a new Air Tractor AT-502B, ZS-XKB. The manufacturer describes this model as “the world’s most popular ag plane with over 1000 of these aircraft having been manufactured since 1987.

Several of these are already in service in South Africa in agricultural, firefighting and geo-survey applications.

Also registered this month is an Air Tractor AT-504 which is a two-seat variant of the aforementioned AT-502B. The cockpit’s side-by-side seating configuration is ideal for training new ag pilots but is still able to fully operate as an aerial application platform.

August has been a good month for helicopters, with five added to the register. Two turbinepowered Robinson R66s have been imported along with a single Robinson R44 Raven II. The other two additions are a single Bell 407 and Airbus Helicopters H125 – the two most popular turbine powered helicopter types in the South African market..

hopefully we see it around the airshow circuit

A 1984 year of manufacture King Air C90A ZS-KXP (LJ-1069) has been registered in South Africa having previously operated in Madagascar as 5R-AGB.

A Cessna 172K, ZS-TMH closes the typecertified fixed wing register additions for August.

Turning to the NTCA types, we also see five new additions, including a single helicopter. One each of the Sling TSI, Savannah S and Bathawk Rs have been added. The popularity of these trio of locallymanufactured aircraft is evident with at least one of these types regularly featuring in these monthly updates.

ABOVE: This ex-Madagascan King Air 90 is now ZS-KXP.

BELOW: Embraer 175 G-CLVK has been imported by Airlink. Image LRS747.

ABOVE: ATR 72-600 ZS-LIZ has now been exported to Gabon as TR-LJZ.

BELOW: Former SAA Airbus A340-600 - ZS-SNG has been exported to Germany.

A single Westland Helicopters manufactured Gazelle AH Mk.1 helicopter joins the large number of these helicopters already owned and operated in South Africa. In February 1967 an agreement between French manufacturer Aerospatiale and Westland allowed the production in Britain of 262 Gazelle helicopters ordered by the British Armed Forces. The AH-1 entered service with the Army in 1974 for observation and transport applications. This particular Gazelle was built in 1976 and carried the serial XX453. It had previously seen service with the Qinetiq Rotary Wing Test & Evaluation Squadron based at Boscombe Down. It was withdrawn from active duty in December 2018 and placed in storage at Fleetlands before its sale to a private owner in November 2022 and registered G-CMMF.

The last addition is a Cessna “Push-Pull” model 337, ZU-NVG (FTB3370024). This aircraft was previously registered EC-MYM and painted in period USAF livery by its owner. It is unclear who the new owner is or what its use will be, but hopefully we see it around the airshow circuit if it retains its USAF livery.

Closing this month’s “fives” are five deletions.

scheduled flights in September. The airline also plans to add an Airbus A320 before year end that will be deployed on international routes including a service linking Libreville with Johannesburg.

Other cancellations include a Diamond Aircraft DA-20 Katana exported to Germany and a Bell Longranger exported to Mozambique. A Pitts Special S-2A ZU-BIL also departs our shores to its new home in Australia. This 1974 built Pitts Special was imported to South Africa as ZS-MIK in 1989 and then moved to the NTCA register in 1997.

As always I close off this review by looking ahead at what aircraft have been delivered, but not recorded in the SACAA updates as yet, or that have seemingly missed in the updates supplied to SA Flyer every month.

Qatar Airways’ acquisition of a 25% stake in Airlink was one of the major news events in the local aviation. This announcement followed months of speculation as to which southern African airline Qatar Airways would invest in.

The SAA A340-600 ZS-SNG (557) mentioned in last month’s column has now been cancelled from the register as exported to Germany. Another departure is the ATR 72-600 ZS-LIZ (1674). This plane departed JNB with a new Gabonese registration TR-LJZ applied and is the first plane for the newly-launched Gabonese national carrier FlyGabon that began

They chose wisely in partnering with Airlink as the carrier has shown continued strong growth under competent management and we are sure to see even stronger growth and perhaps the introduction of larger single aisle aircraft types in the coming months.

Meanwhile Airlink has taken delivery of another two Embraer Regional Jets that will soon feature in this column. Embraer 175 G-CLVK (17000343) arrived at OR Tambo International Airport (JNB) on 24 August. A

ABOVE: Bombardier Global Express 6000 (9438) became ZS-CLO and has reportedly ended up in Russia.

BELOW: Pitts Special S-2A ZU-BIL has been exported to Australia. Image Stuart Soden.

few days later, on 3 September, Embraer 190 N421NA (19000041) landed at JNB having ferried from Marana in the USA via Goose Bay, Reykjavik, Casablanca and Accra.

Meanwhile SAA is expected to return to service another elderly Airbus A340-313

ZS-SXD (643). The plane made an hour long test flight from JNB on 9 August still painted in the original special livery promoting the country’s participation in the 2012 Olympic Games hosted in London.

The carrier’s first winglet-equipped Airbus A320, ZS-SZF operated its first revenue flight between OR Tambo Airport and King Shaka Airport in Durban on 3 September. The jet has been painted in a Star Alliance livery that will please the local spotters.

Pilatus PC-24, ZS-NID (535) arrived on delivery to South Africa on 5 September. The jet routed from Buochs on 30 August routing via Budapest, Hurghada, Djibouti and Kigali before landing at Lanseria International Airport.

A geosurvey configured Cessna 208B Grand Caravan, ZS-CXD, was ferried to Perth from South Africa between 12 and 20 August. This epic ferry taking 70 flying hours was done with 12 stops via East Africa, the Middle East, India and Indonesia. It is expected the plane will again revert to its Australian registry.

Finally, a Beechcraft 400A Beechjet, ZS-MJD (RK-18), was seen at Wonderboom during August being parted out. This 1991 model jet was registered in South Africa in December 2014 but now will end up as scrap metal after all the saleable parts have been stripped.

In closing I want to mention an interesting article published in August by Swiss CH-Aviation that confirms my suspicion, as mentioned in last month’s Register Review, that several of the long- and ultra-long-range corporate jets recently added to the register are done so to side-step sanctions by their Russian owners. In the article it is revealed that the Bombardier Global Express 6000 ZS-CLO (9438), registered in July this year (and mentioned in this column last month),

ABOVE: SAA's first winglet-equipped Airbus A320, ZS-SZF is now operational

BELOW: This Pilatus PC-24 is now ZS-NID and is the second for truckers NiDa.

is operated by Udan Aviation, a company incorporated in January of this year with a single Director.

CH-Aviation further reports that the plane completed a test flight on 10 August from

Dubai World Central Airport and subsequently flew to Malé in the Maldives four days later and onwards to Russia on 15 August. It has apparently since been based out of Russia, operating flights within Asia and the Middle East.

IN A MAJOR BLOW for the world leading bizaviation expo, Textron, Gulfstream and Dassault have announced that they will not exhibit in NBAA for 2024. This may signal a growing dissatisfaction with OEMs for the costs vs return of Expo participation.

The withdrawal of these ‘big-three’ leaves Bombardier as the only large business aircraft OEM to display at NBAA-BACE.

However, several smaller companies like Pilatus and Daher are still in, as are Boeing and Airbus with their airliner conversions.

Textron didn’t say precisely why it pulled out of the show so suddenly, but about half of its workforce went on strike on 23 September and

production stopped. The 5,000 striking workers are members of the International Association of Machinists, which represents most of the shop floor employees. The rank and file rejected a tentative deal that would have given them a 26% raise over four years and a $3,000 annual cash bonus.

NBAA said, “We have been informed by company leadership that their focus on business operations will preclude their participation in NBAA-BACE this year. We respect their decision and look forward to welcoming their return to future NBAA events.”

j

ZS-RMB

ZS-LIZ

• Now certified for TCAS training.

• RNAV and GNSS Certified on all flight models from single engine to turbine.

Baragwanath - FASY R34,00

Beaufort West - FABW R32,30 R 23,10

Bloemfontein - FABL R33,04 R18,74

Brakpan - FABB R33,80

Brits - FABS R29,25

Cape Town - FACT R33,93 R19,96

Cape Winelands - FAWN R33,00

Baragwanath - FASY

Beaufort West - FABW

Bloemfontein - FABL

R34,00

R31,60 R 23,10

R33,04 R18,74

Brakpan - FABB R33,80

Brits - FABS R28,30

Cape Town - FACT R33,93 R19,96

Cape Winelands - FAWN R33,00

Eagle's Creek R31,50 Eagle's Creek R30,50

East London - FAEL R35,70 R19,62

Ermelo - FAEO R31,51 R24,73

Gariep Dam - FAHV R34,00 R23,00

East London - FAEL

Ermelo - FAEO

Gariep Dam - FAHV R32,00 R23,00

George - FAGG R36,40 R19,24 George - FAGG

R35,77 R18,94

Grand Central - FAGC R32,78 R23,29 Grand Central - FAGC R32,49 R20,99

Heidelberg - FAHG R32,20 R23,50 Heidelberg - FAHG R29,33 R21,28

Hoedspruit Civil - FAHT NO FUEL NO FUEL

Hoedspruit Civil - FAHT NO FUEL NO FUEL Kimberley - FAKM

Kitty Hawk - FAKT R32,30

Klerksdorp - FAKD R32,95 R22,08 Klerksdorp - FAKD R32,00 R22,42

Kroondal / Airspan R30,15 R20,91 Kroondal / Airspan R27,20 R19,49 Kroonstad - FAKS R31,63 Kroonstad - FAKS R31,63

Kruger Mpumalanga Intl -FAKN R35,15 R26,30 Kruger Mpumalanga Intl -FAKN R35,15 R26,30 Krugersdorp - FAKR R31,25

Krugersdorp - FAKR R30,00 Lanseria - FALA R33,47 R22,43 Lanseria - FALA R32,32 R20,93

Margate - FAMG NO FUEL NO FUEL Margate - FAMG NO FUEL NO FUEL Middelburg - FAMB R32,80 R22,53 Middelburg - FAMB R31,75 R20,50

Morningstar R30,95 Morningstar R30,95 Mosselbay - FAMO R37,50 R27,00 Mosselbay - FAMO R35,50 R27,00

Nelspruit - FANS R34,98 R25,30

Oudtshoorn - FAOH R33,05 R23,10

Nelspruit - FANS R32,26 R23,00

Oudtshoorn - FAOH R33,05 R23,10

Parys - FAPY R30,73 R21,48 Parys - FAPY R27,77 R20,07

Pietermaritzburg - FAPM R31,40 R24,60

Pietersburg Civil - FAPI R31,95 R23,10

Plettenberg Bay - FAPG NO FUEL NO FUEL

Port Alfred - FAPA R33,50

Port Elizabeth - FAPE R35,08 R22,08

Potchefstroom - FAPS R30,15 R20,91

Rand - FAGM R37,50 R25,55

Robertson - FARS R31,90

Rustenburg - FARG

Secunda - FASC

R32,10 R23,65

R31,91 R25,88

Skeerpoort *Customer to collect R27,91 R18,66

Springbok - FASB R36,46 R27,03

Springs - FASI R37,25

Stellenbosch - FASH R36,00

Swellendam - FASX R32,00 R23,00

Tempe - FATP

R31,64 R21,01

Thabazimbi - FATI R30,65 R21,41

Upington - FAUP R36,62 R24,76

Pietermaritzburg - FAPM R31,40

Pietersburg Civil - FAPI

Plettenberg Bay - FAPG NO FUEL NO FUEL

Port Alfred - FAPA

Port Elizabeth - FAPE

Potchefstroom - FAPS

Rand - FAGM

R33,50

R35,08 R22,08

R27,20 R19,49

R33,50 R23,50

Robertson - FARS R31,90

Rustenburg - FARG

Secunda - FASC

R31,50 R23,00

R29,33 R21,28

Skeerpoort *Customer to collect R24,95 R17,25

Springbok - FASB

Springs - FASI

Stellenbosch - FASH

Swellendam - FASX

Tempe - FATP

Thabazimbi - FATI

R31,70 R23,50

R37,25

R35,00

R31,50 R23,00

R31,64 R21,01

R27,70 R19,99

Upington - FAUP R36,62 R24,76

Virginia - FAVG R33,58 R22,43 Virginia - FAVG R33,58 R20,64

Vryburg - FAVB R31,31 R21,66

Vryburg - FAVB

Vryheid - FAVY R30,15 Vryheid - FAVY

R19,49 Warmbaths - FAWA R32,00 Warmbaths - FAWA

-

Text and Photos: Trevor Cohen

For the first time the South African Children’s Flight has been held outside of Gauteng.

ARRIVING AT FEDERAL AIRLINES at 4.30 am the coffee was hot and the departure lounge warm and comfortable. We were greeted by smiles with sandwiches and cold drinks for the trip to Bloem.

Our flight was in an almost brand new Cessna Grand Caravan EX. We taxied out the gate and almost directly onto Runway 03. We took off and turned over the bright lights of Johannesburg heading south-west to Tempe.

shirts on, get our faces painted, sit on the bean bags, look at the aircraft arriving, or play games with HOT102.7.

The flying started late due to the SA Army deciding to do parachute drops on the same day at the same airport. The army parachute practice soon stopped as they don’t like to have parachutists in the air where there are helicopters operating.

We landed expertly on Runway 01 to a relatively warm Bloemfontein morning. We were greeted with our media bibs, shirts and hats. The children had already started arriving and their excitement was visible. As they entered the kids area they did not know what to do first. Should we jump on the jumping castles, put our

First up, a prayer was said to bless the day’s proceedings. Then there was a civilian parachute drop with a huge South African flag and the national anthem is sung.

Thanks to meticulous planning all the kids were flown in either a fixed wing or rotary wing aircraft over the course of four hours.

ABOVE: Massive tents and containers full of goodies.

ABOVE: CemAir brought down a Beech 1900D. BELOW: Disabled children were helped.

ABOVE:

Some lucky children got heli rides.

The children were from orphanages and homes across the Free State. The object is to introduce kids to flight and show them that there is a future for them in aviation if they liked what they experienced as opposed to crime and gangs.

The event finished with a mini private airshow flown by the Harvard Pumas, Juba Joubert in the Gazelle and the Master Power Extras.

A special thank you must go all sponsors. From radio stations to fuel sponsors to food sponsors to pilots for their time and the aircraft time, to

the optometrists who did free eye exams to the container guys for the control tower.

Never forget those who volunteered their time to move and entertain kids, to feed them and to those who organised the show, those who drove generators, water and clothes down. Those who kept the aircraft safe and refuelled, those who cleaned up afterwards and put up and took down the tents.

We say thank you from every child. Once againwell done Team Gosher.

Even just single passenger Slings were welcome. j

With surveillance and crime-fighting equipment vital to operations, our versatile range of helicopters perform a multitude of critical missions. Supporting law enforcement teams, who in turn support communities, Airbus proudly delivers cutting edge flight technologies that help keep the world a safer place.

Text: Dr J Pons

Amongst the many services it provides, White River based Mercy Air flies teams of optometrists to do sight saving cataract surgery across the other side of South Africa – in the Northern Cape.

THE POWERFUL KODIAK lifted us to the skies. As the wheels lift off, I’m struck by the relief of having my team and precious equipment aboard for the four hours flight to Upington. A grateful reflection that without Mercy Air, we would by now be well into a tiring two day road trip, from one side of the country to the other.

Flying not only avoids the hazards of South African rural roads, but avoids four dead days of travel (there and back) for the very stretched specialist team.

Arriving in Upington, after a thorough briefing, we were soon in the hospital setting up the equipment, supplies, assembling the microscope and creating the various work stations in the clinic.

Mercy Air pilot David Schumacher is an extraordinary mission pilot, who has forsaken flying airlines for small aircraft, and he is becoming an invaluable technical member of this outreach.