HU M SA B E K

Exhibition catalog and construction document

“Pover ty is powerlessness. Pover ty c annot be removed unless the poor have power to make decisions that

- Ela Bhatt

“Pover ty is powerlessness. Pover ty c annot be removed unless the poor have power to make decisions that

- Ela Bhatt

This p roj e ct is i n spi red by the actions of poor working women in Indi a , who have survived societal and state indiference through half a century of relentless oragnizing. Hum Sab EK (We Are One) is the rallying cry of the 3 million strong Self Employed Women’s Association, situated at the confluence of the labor movement, the cooperative movement, and the women’s moverment.

In 2022, Dr. Balsari’s team at Harvard was invited to study the impact of the pandemic on the members of SEWA and its response to the pandemic.

The research was based on a survey of over 1000 households and 30 hours of oral histories, and revealed how fifty years of organizing had allowed these disadvantaged but very empowered women to navigate the greatest public health emergency of our times, when dominant political, social and cultural structures failed to protect the most vulnerable, globally. They implemented solutions that were practical, expedient and mutually beneficial. The research illuminates what it takes to build and sustain resilient communities. The story of SEWA’s response to the pandemic is important because it elucidates alternative approaches to preparing the world for the intractable challenges that lie ahead.

In order to communicate our findings to a wide array of domestic and global audiences, an interdisciplinary team of students from medicine, public health, design, government and computer science, developed a multimedia exhibition combining artifacts from the lives of the workers, oral history videos, data visualizations from the research findings, and a stunning multi-screen display capturing the salience of digital devices in sustaining health, education and wages. This exhibit was first hosted at the Center for Government and International Studies at Harvard, and supported by the Ofce of the Provost, and the Lakshmi Mittal and Family South Asia Institute at Harvard. It then began its tour, Jatra, or journey, with its next stop at the Clinton Global Initiative’s annual meeting in New York in September 2024.

At each stop, the exhibition is accompanied by panels and rount-tables inviting policy makers, artists and communities to explore the exhibit and, along with SEWA’s members, to retell, reinterpret and reimagine futures.

Exhibition Launch at Harvard’s Center for International and Government Studies

April 15, 2024

In conversation with Jyoti Macwan, Secretary-General SEWA, and the Student Exhibition Design Team

May 3, 2024

The Hum Sab Ek exhibition was prominently featured at the Clinton Global Initiative 2024 Annual Meeting in New York City. This marks the onset of the next phase, Jatra—a traveling exhibition that catalyzes a series of dialogues at the intersection of gender, work, health, climate change and resilience, first in the US and then globally.

September 23, 2024

September 24, 2024

In January 2025, the HUM SAB EK (We Are One) exhibition was showcased at The World Bank Headquarters’ Glass Gallery and the main atrium in Washington, DC. The exhibition was launched, with an opening panel discussion, on January 8, that addressed themes ranging from the role of a researcher working with communities, to how to achieve structural societal changes, including shifting decision making to the poor, and the need to put local communities at the center of development strategies.

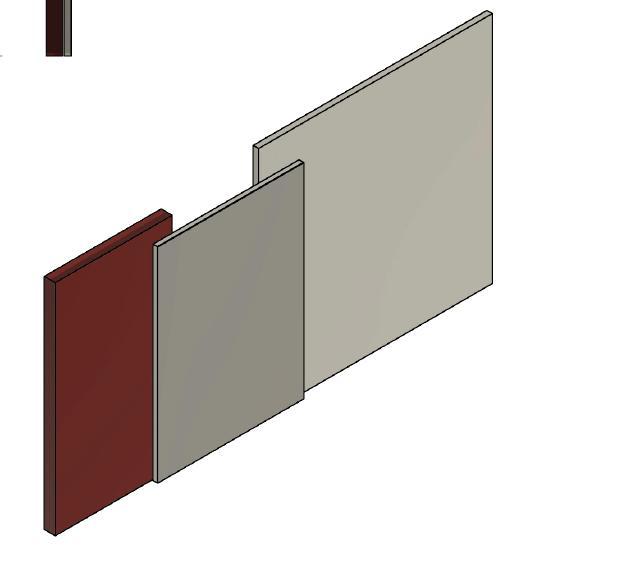

The traveling exhibition is designed using a lightweight modular system, featuring silicon edge graphic (SEG) frames and fabric panels.

Please note that the exhibit comprises 10 installations, each composed of one to four panels (in the five sizes listed below).

Maximum height: 8 feet

Total width: 116 - 150 feet

A – W4’ x H7.5’

B – W5’ x H7 ’

C – W4’ x H8’

D – W8’ x H8’

E – W6’ x H8’

Illustrative example:

Installation 10

Additional Features: A floor mounted literature holder to display SEWA’s timeline booklets.

Additional Features:

Additional Features:

74 Phones and 3 tablets and 3 additional tablets with headphones

Additional Features:

1 Television (28 1” x 16 8”), 5 Earthen pots and wooden shelves.

Additional Feature: 1 Television (28 1” x 16 8”)

Additional Features:

Additional Features: There are two sleeves for rods to suspend the tapestry—one at the top, as shown, and one at the bottom. Additionally, three thin ropes on each side help stretch the tapestry.

The tapestry is accompanied by two floor-mounted stands that display informational placards.

We t ha nk o ur co llea gues f ro m a round the world for the ir co un s e l:

Mihi r Bh att , Ca ro l i ne Buc ke e , B etti n a B u rc h, Ami t D ave , Ma rk Elli ot , Lo r i G ross, Je n ni fe r Le a ni n g , Mi t u l Ka ja r i a , Dee p a n ja n a Klein, Al l y M atth a n, N at ha n M e len b ri n k , Sab r in a Ly nn M ot l ey, He at he r M u m fo rd, Jo s e p h Nalle n , Emily R N ova k Gu st ai n is, R av i S a d hu, Kat h y Schoe r, Vis h we sh Su r ve,

Ch a s e Van A m bu rg, M i c h a e l Vo r t m ann, Rich Wol fe , a n d the teams at CGI S, M a kep e a c e, CGI, GFI, Markham, Chemistry Creative, and the Mi tt a l In st it u t e in D e lhi an d Ca m bri d g e

S atchi t Bal s ari, M D, MP H

As s o ci ate P rofes s o r, Eme rgenc y M edici ne,

Ha r va rd Medi c al Schoo l

B eth Is rael De aconess Medi c a l Ce nter

Hi tesh ree Das, MDes ‘2 5

Ha r va rd G radu ate School of D esig n

TECHNOLOGY LE AD

Rob er t M c Ca r thy, BA ‘23 (H ar va rd Colle ge )

DESIGN TE AM

Wi lli am B oles, MLA ‘26 (GSD )

Kar thi k Gi rish, MUP ‘25 (GSD )

Se lmon Rafey, Mi ttal I nstitu te

De epak Ra mol a , Ed M ‘23 (HGSE )

Sh ari q M. Sh ah, MDes ‘24 (GSD )

B etti na W yl er, Mi ttal In stit ute

RESE ARCH TE AM

Abhishe k Bh ati a , MS ‘ 17 (HSPH )

Kar ti keya Bh atoti a , MPP ‘ 24 (H KS)

Da n B o relli, Di rec to r of Exhibitions , Ha r vard G radu ate School of D esi gn

Lo ri G ross, As s oci ate P rovo st for A r ts an d Cul tu re,

Ha r vard U ni ve rsit y

Ta run Kha nna , Jo rge Paulo Lem an n P rofes s o r,

Ha r vard Busi ness Schoo l

Rahul M eh rotra , Joh n T Dunlop P rofes s o r

i n Ho usi ng a nd U rbani zatio n,

Ha r vard G radu ate School of D esi gn

Ca leb Sh reve, E xecuti ve Di rec to r,

Glo bal Fai rness Initi ati ve

Doris Somme r, I ra J ewell Willi ams P rofes s o r of Roma nce Lan gu ages an d Li te ratu res , Ha r vard Facul ty of A r ts an d S cienc es

MEMBERS OF THE SELF EMPLOYED

WOMEN’S ASSOCIATION

S UPP ORTE D BY:

Project Webpage: https://mittalsouthasiainstitute.harvard.edu/hum-sab-ek-exhibition/