1

2

3

1

2

3

05. Loafers Lodge Tragedy Leaves Lasting Impact on Wellingtonians

06. Campus Bookstore Delays Caused by Attempts to be a Vic Books Dupe

06. The Vice Chancellor’s Rumoured Midday Gym Rendezvous

07. Hot Takes in the Hub

07. Headline Junkie

4

08. Diaspora in Cinema (Films Even Your Immigrant Mother Will Enjoy)—Joanna Fan

About Us

5

10. The Diaspora Paradox—Cileme Venkateswar

14. The Trauma Heirloom—Bella Maresca

18. The Good, the Bad, and the Aunties: Surviving Immigrant Family Reunions Like a Boss—Snigdha Mundra

22. Colonisation got my Tongue—Kiran Patel

26. Delicate Survival Strength Alive In My DNA— Franciszka Pietkiewicz & Stefania Pietkiewicz

28. Musings Over Nasi Goreng—Guy van Egmond

31. Journey to Freedom—Anonymous

32. Aye, Chootiya!—Janaye Kirtikar

33. Vegan Tofu Cabbage Dumplings—Sarah Burton

8

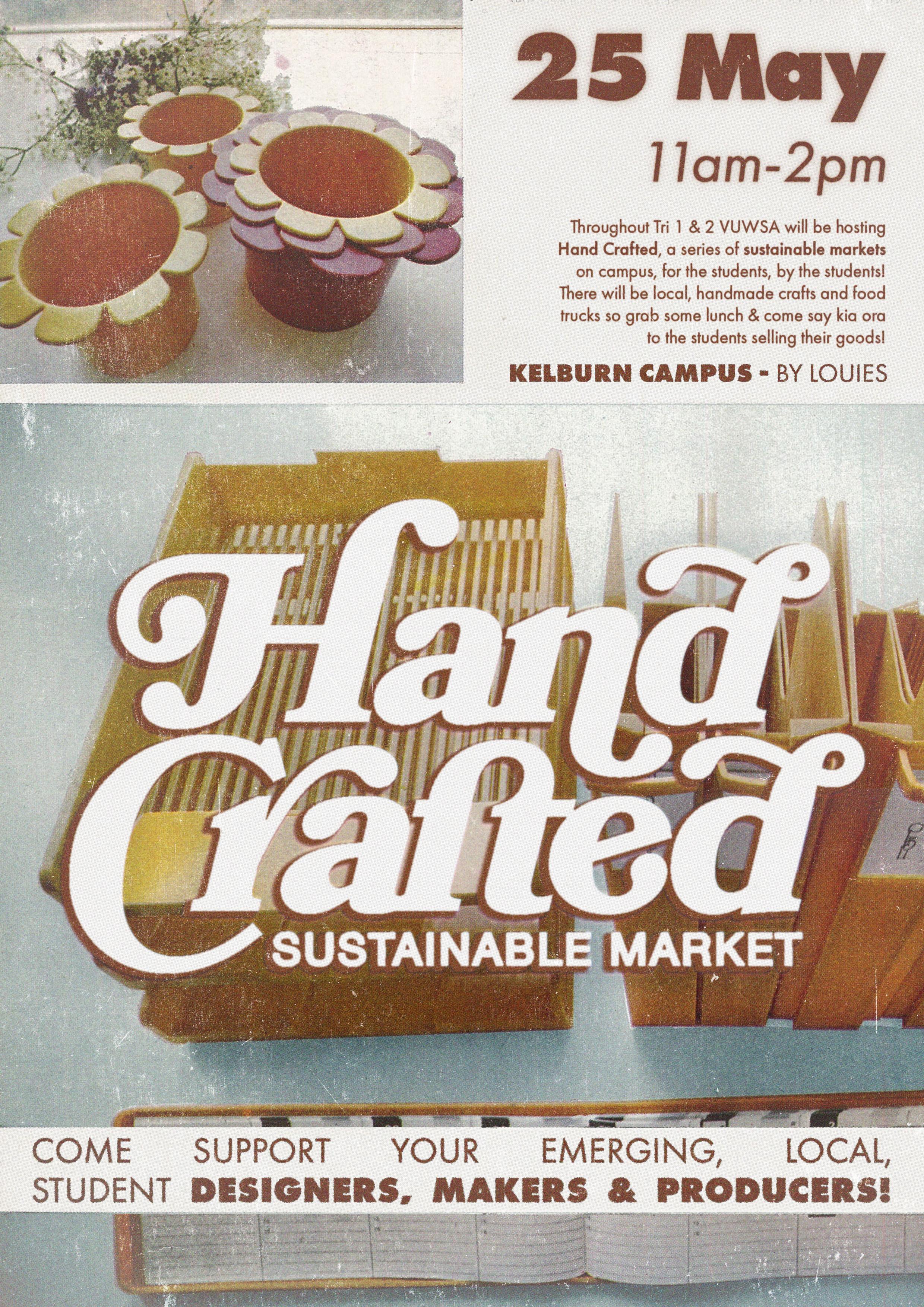

Salient is published by, but remains editorially independent from, the Victoria University of Wellington Students’ Association (VUWSA).

Salient is funded in part by VUWSA through the Student Services Levy. Salient is a member of the Aotearoa Student Press Association (ASPA).

The views expressed in Salient do not necessarily reflect those of the Editors, VUWSA, or the University.

Complaints

Complaints regarding the material published in Salient should first be brought to the Editors in writing (editor@salient.org.nz).

If not satisfied with the response, complaints should be directed to the Media Council (info@mediacouncil.org.nz).

Find Us

Twitter: @salientmagazine

Facebook: fb.com/salientmagazine

Instagram: @salientgram

www.salient.org.nz

Salient Podcasts

Instagram: @salient_podcasts

Salient Podcasts

Clearly, we look a bit different from the usual editorial suspects. This issue is guest edited by us—Joanna and Cileme. “Diaspora” exclusively focusses on immigrant and refugee stories!

Joanna: My real name is Zhao Fan (you can find the respective characters by my signature at the bottom of this editorial). My immigration journey has been a bit complicated. I was born in Beijing, China and lived there for five years. I moved to New York City at age 5, and learnt English there (would you believe, it actually comes in handy). In 2012, I moved to Aotearoa, first living in Ōtautahi, and later moving to Te Whanganui-a-Tara in 2019 to study. You could call me a third culture kid—I still don’t know quite where to call ‘home’. To give all of this a single label, I am a firstgeneration Chinese immigrant. To me, my language, Mandarin Chinese, has been my most valuable cultural link. Growing up, we exclusively spoke Mandarin at home, and still do to this day. I think it's such a privilege to be raised bilingual, and I am infinitely grateful to my immigrant parents for granting me this gift.

Cileme: Whenever people ask where I’m from and where I grew up, I always say “New Zealand born and internationally raised.” Born in Papaioea, I spent my childhood darting around the world before moving to Pōneke to study. Technically, I’m a second-generation Indian New Zealander. It’s funny to me that people love to ask ‘so where are you from?’, when my go-to answer is almost always ‘uhhhh, good question’. I don’t speak Tamil, or Bengali. I feel like I’m making up everything about my cultural identity as I go. As a brown girl with a not-white and not-Indian name, a thick New Zealand accent to my family, but an oddly not fully New Zealand accent to New Zealanders, and no tangible cultural ties to being Indian, nothing about my identity has ever really made sense. I’m still figuring out what ‘home’ means to me. I’ve been searching in academia, fiction, travel, and food—when I find an answer, I’ll let you know.

What, then, does it mean to be a part of a diaspora in Aotearoa?

Diaspora is defined as ‘the dispersion or spread of a people from their homeland’. Naturally, this issue focuses on both immigrant and refugee experiences—diaspora manages to embrace these two displaced identities, the combination of migration, and forced exile. In Aotearoa, we are perfectly placed to explore what diaspora means: we are a country built on a fraught history of migration. Whilst we are somewhat familiar with our colonial past, how do we as immigrants or refugees make sense of where we fit in Aotearoa society? To us, diaspora means finding a place of belonging, even if it isn’t where you might expect. Finding community, reconciling trauma, sharing food,

Catch us on: Salient is fuelled by:

inheriting intergenerational memories, and carrying our cultural legacies with us wherever we go.

In features this week, Kiran cracks us up with a painfully relatable and heartfelt account of reconnecting with their linguistic background. Fran and her mum Stefania dive deep into their refugee background, filled with both strength and sorrow. Bella retraces their connection with their Jewish heritage through the Menorah on their living room bookshelf. Snigdha gives you a fool proof guide to immigrant family reunions through the good, the bad, and the Aunties. Janaye mourns the loss of language with an edge of humour, teaching us her favourite Marathi and Hindi curse words. Through nasi goreng, Guy explores the integral connection between cultural identity and traditional foods. And if you’re feeling like a bit of a chef yourself, go try out Sarah’s delicious dumpling recipe—you won’t regret it.

Some final notes from us: keep using or learning your language, find your past within the photos you take, measure ingredients with your heart, keep your grandma’s ancient family gossip alive, and force your friends to watch a Bollywood movie on your next dusty Sunday.

We hope you find a piece of home in this issue.

Arohanui, Cileme and JoannaThe Ngāi Tauira column is always a highlight, but I particularly wanted to say how much I loved and was moved by Huy's kōrero on faith and queerness in Issue 9. It was nuanced and thoughtful, but deeply approachable, and I just felt really honoured to read about something that I struggle with from a different perspective. It's also not something that's talked about all that often, so it was great to see it in the pages of Salient.

-Anonymous

Think something is missing in the pages of Salient?

Then it’s up to you to pitch it to us.

Salient is entirely student run and produced, so what appears in this mag is at the whim of what students want to write about. If you’ve got something you’d like to see in Salient, send us a pitch at editor@salient.org.nz, and get writing!

Wellington City is grieving after the deadly house fire at Loafers Lodge in Newtown last Tuesday morning, which has so far claimed at least six lives. At the time of writing, 11 people remain unaccounted for, and 50 people are currently displaced. The fire, which started just after 12 a.m., has raised concerns around the safety regulations for emergency accommodation and boarding houses.

Loafers Lodge provided both short and long term accommodation to some of the cities most vunerable. The hostel’s 90 rooms were a support to mostly lower-income communities and marginalised groups, particularly those on disability or sickness benefits, elderly, the previously homeless, previously incarcerated, and deportees from Australia. It was also home to nursing and hospital staff who were unable to find affordable accommodation near the hospital.

“My heart goes out to the families impacted by this. I've been constantly amazed by the fire and emergency service, as well the police, for doing such a phenomenal job,” Mayor Tory Whanau told RNZ’s Checkpoint on Tuesday evening. Whanau and Wellington City Council (WCC) have been organising response to the fire, finding emergency accommodation, food, and clothing for evacuees—including allocating $50,000 to Whanau’s mayoral relief fund.

Bella, a nearby resident, lives only a few buildings down from the Loafers Lodge. “It was just after midnight when I heard someone running down the street yelling ‘Help! Help! Fire! Fire!’,” they said. “By the time I got to our living room window, there were already three firetrucks and multiple ambulances

pulling up on John Street. I could see smoke billowing out the top story of Loafers Lodge.”

Bella didn’t realise the extent of the fire’s damage until it made headlines that morning. With warnings about possible asbestos risk from the fire, they closed their apartment windows and stayed indoors for the day.

“The whole neighbourhood shut down, everyone’s been in collective mourning,” recounted Salient chief reporter Niamh Vaughan, another nearby resident. “I couldn’t sleep the night after. Some of my neighbours, people I’ve walked past on the street, people I shared the local shops with, are still in that building.”

On Wednesday morning, fire investigators and Urban Search and Rescue were able to enter the building. Some residents who escaped the fire say that they did not hear fire alarms go off on Tuesday night. Loafers Lodge was not required to be retroactively fitted with emergency sprinklers, as modern buildings are. Despite this, the building was issued with a warrant of fitness by WCC in March this year.

The event will leave both physical and emotional scars on those involved, and on the community, for some time. “I’m still finding it difficult to sleep or even be in our apartment knowing what’s going on over there [...], that there are still people missing who could be trapped inside,” Bella said.

Salient wishes to pass on condolences to the friends and family of those lost in the fires, and to the Newtown community impacted by the tragedy.

Students have been left confused after the Kelburn campus space previously occupied by Vic Books has remained empty despite promises from the university that a new book store would open in April. The Lab shifted to replace the café portion of the Vic Books space, but it still lacks a bookshop.

A spokesperson for the university confirmed to Salient that the new Campus Books branch will open on Kelburn campus on 1 June, over a month and a half longer than the initially promised date. The university has cited delays in recruiting staff as the main reason. Until this date, the university encourages students to order textbooks directly from the Campus Books website.

Spokesperson for Campus Books, John Chisholm, explained to Salient that it was important that the branch was meeting the needs and expectations of the university. “The biggest priority was working with the university and its staff to identify what textbooks are prescribed [or] recommended,” Chisholm said. “Coupled with this, it was important we employed the

appropriate manager. We have done so with Susan Murphy, an experienced retailer.”

Regarding Pipitea campus, the university is yet to confirm if a Campus Books branch will be opened. “The university is in discussions with Campus Books about a potential ‘pop-up’ store at Rutherford House on the Pipitea campus, but there are no concrete plans at this stage,” a university spokesperson told Salient. “There are no further updates on plans for the rest of the former Vic Books site beyond The Lab and Campus Books’ premises.”

Chisholm has confirmed that the Kelburn branch will offer “a mix of products, not only texts and stationery, but also other items attractive to both students and staff alike”, and the university has confirmed that the branch will also stock official VUW merchandise.

Whether the new branch will live up to the legacy of Vic Books—which has been referred to as the ‘heart’ of the campus—is yet to be determined.

Words by Ethan Manera (he/him)

“walking to and from the gym. [...] He’s always wearing sport shoes and running shorts and a lil activewear shirt.”

When asked if the sighting could be of another gym-going Nic Smith lookalike, the source said they were certain it was the real VC. “It's definitely him.”

University Recreation refused to be pressed about whether gym staff had spotted the VC using the facility, keeping us in the dark around his alleged exercise habits.

The arrival of Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington’s new Vice Chancellor Nic Smith has been a largely quiet transition. Besides making a cameo in VUW’s TikTok as the university’s “hot new bombshell”, Nic Smith’s tenure has been a muted affair. But one bizarre allegation has dominated the discussion of our new VC.

According to urban legend, Smith is partial to a lunchtime workout at the University Recreation gym. One eyewitness told Salient they frequently spot the VC

Salient decided to go straight to the source, asking Smith for a comment on his exercise habits. Although we didn't hear from the man himself, a spokesperson for the university confirmed that he does in fact visit the university gym. “The timing of his visits to the University Recreation Centre depends on his other commitments.''

“The Vice-Chancellor finds that maintaining good health through regular exercise and good nutrition is important for helping him function well in the role. He supports other staff and students who find the same,” the spokesperson said.

The week before last, National Party Leader Christopher Luxon told Newstalk ZB that he refused to form a government with Te Pāti Māori, stating that it would be a “coalition of chaos”. Luxon has ruled out any arrangement with the party, despite the fact that they’re likely to be National’s ticket into government.

Polls last week showed Labour and National were neck and neck, with Labour at 35.9%, only just ahead of National’s 35.3%. Assuming Te Pāti Māori wins an electorate, they would have the five key seats to the successful coalition, so Luxon’s prejudice may cost him if he wants to be Prime Minister. Co-Leader of Te Pāti Māori Debbie Ngarewa-Packer has stated that National has “nothing in common” with Te Pāti Māori. The party would prefer to work with a “party focused on [...] transformational change” and therefore they wouldn’t be interested in collation anyway.

Cocaine. A phenomenon sweeping the nation. Use of the drug has increased across the entire country, with Auckland continuing to “consume the most cocaine per capita”. The NZ Police tested wastewater at ten different sample sites across the country, and reportedly use of the drug is up 70%. "Cocaine consumption across sample sites increased [...] to an average of 1.6 kilograms per week," said the Police. MDMA consumption, however, is seeing a decline, with use down 28% on average per week. Methamphetamine usage is also decreasing, dropping 17% on average.

Mine is Tim Tam/ Timothee Chalamet I believe.

I quite enjoy going to wine tastings. I fully like, swirl it around, get my nose in there, and, you know, talk about where the grapes come from and everything. I love it.

Probably listening to Rick Astley’s ‘Never Gonna Give You Up’.

I think, getting a cheeky little flat white with soy milk in the morning in my to-go cup for like, eight dollars.

I won’t shut up about Everything Everywhere All At Once (2022). I don’t think anyone can. At the risk of sounding like every other immigrant daughter who watched that film—yes, it really did change my life. But it also changed much of Hollywood’s discourse surrounding diversity and inclusion. An overnight sensation, the film encouraged and accommodated valuable conversations about who a heroine could be, what they looked like, and how they spoke. Most of all, it shed light on often marginalised immigrant stories and communities, illuminating the sacrifices our own mothers, fathers, and grandparents had to make. But the immigrant experience does not end at Everything Everywhere All At Once. There are still many stories unexplored.

So on that note, this is an inconclusive introduction to contemporary cinema about diaspora and the immigrant experience.

The Joy Luck Club is a story combining the two things I love most: an Asian ensemble cast, and a focus on immigrant mother-daughter relationships. It's told through a series of interconnected vignettes, following four Chinese immigrant women, their American-born daughters, and the battle between the juxtaposing worlds and value-systems they were raised in. This is a story that I, and many others, will be all too familiar with. It’s a never ending struggle to find equilibrium between an individualistic and collectivist culture. But Amy Tan’s story offers a solution—she highlights the importance of empathy in building bridges between different cultures and communities. Mum will be thrilled to hear that.

Bend It Like Beckham captures the intersectionality of being an immigrant and queer (I know Keira Knightley’s abs were your sexual awakening). It’s a film that championed diversity and inclusion in the 00s, creating a platform for immigrant voices in women’s football. Perhaps this hyper-specific storyline is what truly makes the film a trailblazer ahead of its time, capturing the ubiquitous nature of immigration. Like The Joy Luck Club, the film explores the pressures of being the child of immigrants, and the difficulty of reconciling our own dreams and ambitions with the expectations and cultural norms of our families. Much to our parents’ dismay, I know we all held our breaths in anticipation for Jess and Jules to finally kiss. To quote on of Jess' aunties, “Lesbian? Her birthday's in March. I thought she was a Pisces.”

Persepolis contains the only acceptable use of ‘Eye of the Tiger’. Based on a graphic novel, it is an animated film about a young girl’s experiences growing up during and after the Islamic Revolution in Iran. Forced to leave her country due to conflict, political oppression, and social unrest, she navigates an unfamiliar Europe in search of freedom. The film is sure to resonate with anyone who has navigated a foreign country alone, as she struggles with feeling homesick and isolated in an unfamiliar place. Whilst the film’s details are unique to the time period, its politics are particularly relevant given the ongoing protests in Iran.

Brooklyn is a historical portrayal of migration that makes you endlessly grateful to not be crossing the Atlantic on a boat. Although the film is set in the 1950s, much of the immigrant sentimentality has stayed the same. At its core, Brooklyn is a story about belonging—one that is sure to resonate with first-generation immigrants and international students. The true essence of the film is captured in its final lines: “You'll feel so homesick that you'll want to die, and there's nothing you can do about it apart from endure it. But you will, and it won't kill you. And one day the sun will come out—you might not even notice straight away, it'll be that faint. And then you'll catch yourself thinking about something or someone who has no connection with the past. Someone who's only yours. And you'll realise... that this is where your life is.” That’s all you need to know.

Bao is the cutest thing you’ll ever watch. It's a Pixar short, so you have no excuses. I still remember the outrage this short film caused when it was first released—it was like no one had ever heard of symbolism before. But as an avid eater of baozi, let me mansplain it to you. When her only son moves out, a Chinese woman begins mothering one of her baozi that has come to life. As he grows and eventually plans to leave home with a new fiancée, she eats him so that he’ll stay with her forever. I know it’s a strange storyline, but this allegory is an ode to immigrant mother-son relationships. It’s also the powerful story of an immigrant, directed and written by an immigrant, addressing immigrant issues like internalised racism and cultural differences. I still cry every time I watch it—it truly illuminates the sacrifices our parents had to make for us. Shut up and let us enjoy Bao

Minari is a touching exploration of collectivist culture. The film follows a Korean-American family migrating from California to rural Arkansas in pursuit of the 'American Dream'. As they encounter language barriers, cultural differences, and alienation, the film uniquely portrays the experience of growing up in an overwhelmingly white community. In the face of financial difficulty and struggles to adapt to farm life, the story emphasises the importance of collectivism, family, and community support for immigrants. Halmoni (Grandma) Soon-ja, who joins the family from Korea, brings her own rigid perspectives and cultural roots— an image not unlike my own upbringing. Her presence also creates a support system for the family, values at the heart of any immigrant dream. Where would we be without our grandmothers?

In the Heights is an immigrant theatre kid’s wet dream. By following the colourful lives in a predominantly Latin American neighbourhood, New York City’s Washington Heights, the film addresses many contemporary migration issues facing American society today. Most compelling is its exploration of the politics surrounding migration, and the ripple effects that discriminatory policies can have on immigrant communities. Although not explicitly named, its quiet commentary on the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals’ (DACA’s) effects on undocumented youth is a heartbreaking and timely story. For every step forward, we really do take two steps back.

Polite Society is a new, kickass, hilarious, and heartwarming story about sisterhood. Think St Trinian’s meets Kingsman, but brown. British-Pakistani sisters Ria and Lena are caught in the tension between tradition and legacy, and the desire to forge your own (culturally blasphemous) path. When Lena agrees to an arranged marriage, Ria is horrified, and becomes determined to find a reason to break off the engagement. Cue: shady fiancés, even creepier mother-in-laws-to-be, and secret experiments to manufacture the perfect South Asian wife. Ria and her two best friends, armed with extra-curricular martial arts training and bucketloads of teenage girl rage, take this ominous operation head on. Polite Society is, at its heart, about being true to your own dreams amidst the pressures of holding onto your culture. Plus, you get badass brown gals kicking ass in traditional South Asian outfits. What more could you ask for?

(If you’re quick, you could still catch it in cinemas!)

By Cileme Venkateswar (she/her)

By Cileme Venkateswar (she/her)

When I went to India this past summer, I arrived armed with two film cameras, three rolls of NZ-bought film, and two years worth of selfreflective, cultural identity soul searching. I was determined that, somehow, I would capture the secret in my photos. The secret, the answer, the missing piece, the special ingredient—whatever mysterious, elusive part of me that was from here, that recognised, responded, and yearned for this place. I was adamant that it would show up through the lens.

I burned through my NZ-bought rolls quickly and sought to find some more, but as it turns out, film is hard to come by in India these days. Amma (my mum) and I trekked all over the city to get our hands on some, eventually finding a couple of hole-in-the-wall camera shops in a crowded side gullys. It was this film that I used carefully, sparingly, searching desperately for something with my glasses pressed up against the viewfinder. I dragged Amma through my childhood Calcutta haunts, trying to immortalise a feeling that would slip away before I could understand what it was. Only, when we returned to New Zealand and I finally got the rolls developed, the film we’d bought turned out to be expired. Most of my photos from a once in a lifetime trip to the Sundarbans were indecipherable. I cried myself to sleep, terrified that the rolls still sitting on my dressing table waiting to get developed were just as useless. That all these places and people I had sought to preserve were gone, as though losing the photos had destroyed any chance of finding myself through them.

But, unlike the Sundarbans photos, this film wasn’t underexposed beyond the point of no return. In fact, damage or age to the film instead made it exactly what I hadn’t known I was looking for. The photos were caught between my 25-year-old eye, looking at a city woven into the fabric of who I was, and an echo of what it had once been to me, a child all those years ago. Maybe even what it had been before that.

The photos were a little faded. The underexposure obscured clarity, and dulled bright and vivid colours a little, like a fog creeping in from the edges. But it also smoothed out some of the wrinkled faces, the crumbling buildings, and the cracking paint that had reminded me of how much time had passed. I was 25 and taking photos that captured how some of these people and places had looked to me at 11, at 7. Somehow, between my eye, the viewfinder, the lens, and the film, the mystery of this place that I’d never fully understood reemerged in photo form—the family home that always felt larger than life, the train tracks that would go on forever, the people whose gorgeous clothes and weathered skin and street-side card games made me want to write endless stories about them. ✦

Alongside my own photos, my mother— a better photographer by far—was taking photos of the same places, the same people. When she got them developed, it took me a while to realise that they were from the same trip. The black and white, the grain, and Amma’s eye for shapes and shadows created a beautiful timelessness to her photographs. When I looked at them in comparison to my own, I realised that, in essence, they were the same. My collection was caught between my child and present selves. Hers seemed caught between her present self and the person she was when this city had been her home, her stomping ground. When these haunts were hers.

Putting these two sets together created a curious kind of paradox. Though taken on the same day, each echoed back to a different time, a different glimpse of the city and how the two of us fit into it. Placing them side-by-side almost felt like a double exposure, a glitch in time. It captured diaspora in a way words never could—the simultaneity of belonging and non-belonging, of memory and history, of intrinsic familiarity and isolating alienation. The diaspora paradox.

On its own, the black and white photo in this set feels timeless. Maybe it’s from sometime in the early 70s, as my mum crosses the railway tracks, running late for school.

Maybe it’s not from my mum’s life at all. With the vendor looking out at the train tracks, you can almost forget the photographer is there and that you’re watching this moment through another person and their camera.

The vendor looks at me, smiles, and waves as my finger presses the shutter button. The moment becomes flooded with colour and movement. It’s here and now, and looking right at us.

One of my favourite quotes is from an essay by Seo-Young Chu: "Looking into the past, we find history already gazing back at us."

Nothing felt more paradoxical than staring at myself in a photo that looked like it was from some timeless, decades-past point in history. I remembered being there that day, on the street. But in photo form, it was as though I’d time travelled into my mother’s youth, or swapped places with her for a second.

It was also as though Calcutta and Amma’s Canon AE-1 were snagging my attention to say, “You’re looking for that part of you? It’s right here, it’s always been there, and always will be (if you look at the right angle).”

CW: Anti-Semitic Violence.

On the coffee table, nestled between two of Mum’s green velvet armchairs, sits a gold Menorah. It's the first time it’s been taken off the bookshelf in years. There's a Christmas tree in the corner behind it. On 13 December 2020, the Menorah is finally serving a purpose in our home other than looking beautiful. Mum and I melt all nine candles into their holders on the seventh day of Hanukkah. This isn’t how you’re supposed to do it.

Step One: On night one, starting from the right holder, place one candle into your Menorah. Also add your shamash, or ‘helper’ candle. Your shamash is placed in the centre of your Menorah, and is used each night to light the remaining candles.

Step Two: Each night, another candle is added and lit. Though you place the candles from right to left, you must light them each night from left to right.

Step Three: By the eighth and final night you will have all nine candles lit.

You need 44 candles to complete this ritual. We only had nine. Nevertheless, we make do. Despite having to do so in an unconventional way, we are determined to complete this together. We wait until it’s dark and then light all but one of the candles. We let them burn for half an hour. Then we blow them out. We need to save what’s left of the candles for tomorrow night. The next night, we light them again, letting them burn all the way down. I go to bed wondering why we have never done this before.

I was 20 the first time we celebrated Hanukkah. When I moved out of Mum’s place the following year, the Menorah was handed down to me. Jule, my grandma, bought the Menorah for Mum in 1984 when she visited the Jewish Museum in Manhattan. And now, it's mine.

Looking at the Menorah sitting on the mantlepiece of one of my first flats, I realised I knew almost nothing about my family history, nor our Jewish cultural identity.

‘Jewish’ wasn’t a term I would’ve chosen to identify myself with as a child.

But it’s not really a question of choice, is it? Not for me, nor anyone in my family. It’s cultural inheritance. It’s in our blood.

So why did I, for the majority of my life, feel incredibly disconnected from a part of me that is so significant and rich in culture?

Grandma has always felt like the glue that keeps my family connected, and food is our familial love language. When I was a kid, she had a house out by Waikanae Beach. We would drive up every couple of months for family gatherings. One of my warmest memories is of being 6-years-old, stepping out of the hot car, and smelling the salty sea and Grandma’s famous Christmas ham wafting out from her front door.

Grandma got her love for food, and her witty personality, from her mother and my great-grandmother, Ester.

Ester and her husband Helmut escaped Nazi Germany right before World War II began, coming to Aotearoa as refugees in 1939. The persecution of Jews didn’t start with the war. As children and young adults, my greatgrandparents lived through the rise of Nazism and Hitler coming into power. According to Grandma, her parents believed that Hitler’s influence would be short-lived. This was until 1938, when they lived through Kristallnacht, the night of broken glass, where all the Jewish premises throughout Berlin had their windows smashed and shops ransacked by Nazi supporters. My great-grandparents then realised the severity of what was happening and escaped.

Ester and Helmut both had very relaxed, liberal, and mostly secular Jewish upbringings. The difference with Ester was that her mother was non-Jewish. When I asked Grandma about this, she told me, “This was very radical for her father to have married 'out' of the faith, despite his own father withholding his permission for a long time.” Many religious Jews believed, and still do believe, that you can only be Jewish if it is passed down to you through your mother’s bloodline. This meant that to many, Ester would not have been considered Jewish. But that meant nothing to the Nazi regime.

Ester went to Schul (religious studies), and there she learnt Hebrew. Her first job in Berlin as a young woman was reading the Hebrew newspapers to a rabbi who was going blind, and she assisted him in preparing his sermons. While Ester’s family didn’t often participate in religious aspects of Jewish culture, they attended a synagogue, and celebrated the rituals of holidays such as Passover and Hanukkah with food and family gatherings.

It makes sense then that food has become such an important part of my family. It has always been something that brings us together, perhaps even well before Ester’s time. We still cut the crusts off Ester’s classic egg sandwiches, long after she has passed away.

Unlike Ester, Helmut grew up with religious Jewish traditions, but came to believe that religion had been the cause of conflict and persecution over the ages. Eventually, both Helmut and Ester became committed socialists and atheists. Because of this, Grandma didn’t go to a synagogue or grow up with any of the religious aspects of Jewish culture.

That is not to say that they were disconnected from their Jewish heritage, Grandma explained to me.“I feel that our background is deeply embedded in me. While one might think it is perhaps a European or German heritage, I believe that it is definitely a Jewish heritage that connects our parents to us and them to their forebears. It is the flavour of language, humour, food, rhythm of living, the emotional and the physicality of our lives, and our background of the arts, design, music, and literature.”

As a child and teen, I found it hard to disconnect the religious side of Jewish culture from everything else. I didn’t recognise that my family’s traditions were intrinsically connected to an ‘essense’ of Jewishness, not religion.

When I was around 6-years-old, my parents started getting into the Bahá'í faith. I was too young to know what that meant. As part of it, Mum ran a children’s group, where I hung out with friends and did crafts. I remember it with that sense of innocent childhood fun.

However, I saw my big sister Toby struggle with this new religious phase. With 8 years between us and different dads, she never talked to me about it. I was her annoying younger sibling, trying to be a ray of sunshine in her teenage angst. For the longest time, all I did was observe from a distance.

In recent years, my sister and I have been making up for lost time. Whether we’re just hanging out in her living room going through her extensive vinyl collection, or laying on the floor psychoanalysing our parents and unpacking our upbringings together—we’ve found that closeness I missed in childhood.

It was over a cup of tea on the couch that we began talking about Mum’s Bahá'í phase. Like our great-grandparents, Toby is an atheist, and felt deeply uncomfortable having to participate in Mum’s exploration of religion. Toby’s main issue with it was the fact that, as far as she understood it, Bahá'í was an openly homophobic religion. She couldn’t understand why Mum would want to be part of a religion that seemingly supported something so wrong, and went against the morals we were raised with. We had always been taught to be highly empathetic, and to care deeply about equality and social issues. It just didn’t make sense.

Mum eventually left the Bahá'í faith. After seeing how deeply it affected my sister, she questioned the community's homophobic beliefs and was only met with rigidity.

Toby told me this was a generally miserable time in her life, and she felt isolated. Her angst was caused by more than just teenage hormones, more than the sudden religious phase. It was the instability she experienced throughout her upbringing.

Despite our age gap, instability is something my sister and I had in common. We moved around a lot, constantly uprooting our lives and starting again. Going from one school to the next, over and over again, always being the ‘new kid’, and building friendships while knowing that a year later we’d probably never see them again. I never really understood why my parents would do this. Just as it started to feel like things were settling and we were building a stable home, we would pack up and leave. We were living a nomadic lifestyle, and I hated it.

I’ve come to understand the decisions Mum made through conversations with her about my childhood, and her own upbringing. Mum had a fractured, complicated childhood more so than me. I remember the first time she told me she had four fathers. I didn’t understand, and I still don’t entirely. I won’t get into it. You get the point. But I do enjoy telling people Mum is like Sophie from Mamma Mia (with a lot more trauma and an extra father).

“There were always these seemingly obvious ‘here and now’ reasons for why we needed to move. I also think that there's something about when things are difficult or threatening —in an unconscious way, my solution was to move and make a better life,” Mum told me. “It’s a thing in my mind that I associate with survival, in that sort of transgenerational way. A lot of the time Jews were chased away, forced away, but for us it’s so much in our bones that it becomes a coping mechanism.”

What she was describing was the effects of transgenerational trauma.

I wanted to see if I could trace this back further, so I asked Grandma what she thought. She agreed with Mum, saying her feelings were evidence that trauma is transferred through the generations by 'osmosis’. “It is not just the previous generation or two that passes it on—it has been generation upon generation throughout history where Jewish peoples have been persecuted and displaced time and again, and I believe that we have this inheritance instilled within.”

On the surface it may seem like our parents pass trauma onto us through the decisions they make that directly impact us. But often, especially for families who have experienced extreme discrimination and persecution, these decisions are rooted in transgenerational trauma. It is not as simple as saying that we repeat the exact same mistakes our parents make, because the way we respond to trauma changes with each individual.

Something everyone in my family shares is an incredibly strong survival instinct and need to rise above adversity.

For Grandma, this manifests in the way she cares for her health and relationships, adapting and embracing change in a way others may not be able to. She cares deeply about creating a loving and caring environment for our family.

Mum has a desire to help others understand their own trauma, and is incredibly empathetic. She’s said that because of the trauma she experienced and saw in our family, grieving became her superpower. This partly led her on the path of becoming a therapist.

My sister and I both prioritise stability and security, putting more effort into creating comfortable lives for ourselves. We have mastered adapting to change, even when it’s out of our control.

So why did I feel disconnected from my Jewish background for most of my childhood? I simply didn’t see the way it was innately woven into the fabric of my family, and therefore, me.

It’s the end of 2022. I’ve just moved into a new flat with my friend Niamh. I’ve been in and out of hospital for the past couple of months. It’s been a rough year. Niamh and her boyfriend Sol are at his parents’ house. They’re celebrating the first night of Hanukkah. I’m home alone, laying on the couch. My Menorah is sitting on a yellow metal bookshelf behind me. It’s 11 p.m. I miss Mum.

Earlier that day, I overheard Sol on the phone talking to his mum in Hebrew. I was hit with a wave of jealousy. Why didn’t I understand what he was saying? As I watched them leave for their Hanukkah celebration, a second wave of jealousy hit.

I Google how to say ‘Happy Hanukkah’ in Hebrew.

Chag sameach!

I look at my Menorah. I forgot to light it last year. Shit Better try that again, I guess. I get up, put a candle in the left holder, and one in the center. I light the shamesh, and then use it to light the other candle. Wait… I was meant to start from the right, wasn’t I? Ugh. Regardless, I let them burn for 30 minutes, then blow them out.

Niamh and Sol come home. “Chag sameach!” Sol says. I awkwardly smile, I can’t say it back. I don’t know how to pronounce it. Probably should’ve looked that up too.

I forget to light it again until the fourth night of Hanukkah. Sol comes over and helps me do it. He says a blessing in Hebrew. I don’t understand, but it’s nice to feel included. It makes me realise that just because my experience is different from Sol’s, doesnt make me any less Jewish. I’m still ‘part of the tribe’, as he would say.

I don’t need to tick boxes or complete rituals. My Jewishness is in my blood, my bones and the essense of my being. It’s an inheritance, a fingerprint, passed down to me through generations.

So, my Menorah can just sit on my bookcase. A simple reminder of the beautiful, tragic, wonderful, and traumatic history of my family—my Jewish family.

" It has been generation upon generation throughout history where Jewish peoples have been persecuted and displaced time and again, and I believe that we have this inheritance instilled within."

Winter break is approaching fast, and that can only mean one thing. The ultimate emotional whirlwind, AKA good old family reunions. A special kind of event where all your problems have a way of making themselves known, leaving you to think, "How the hell do they know that?"

Family reunions can end up being the highlight of your year, or leave you wishing you had put your therapist on speed dial. Love ‘em or hate ‘em, there’s no denying that these gatherings are never dull. But fear not, as a seasoned veteran who has attended countless family gatherings, I present to you seven tips not just to survive, but to thrive at these events. From the art of the humblebrag to knowing when to make your dramatic exit—follow this guide and you’ll be the Aunties’ favourite in no time.

I get it, no one wants to come off as a pretentious show-off. But you don’t have to be a Nobel Prize winner for your family to take an interest in your life. Maybe you’ve taken up a new sport or got a better job—it’s your chance to flaunt those accomplishments and break the ice while doing so. Seriously, don’t settle for awkward small talk. Your cousins are probably doing the same. No shame in hopping on the humblebrag train once in a while.

Being a first, second or third-gen immigrant can mean losing touch with the goings-on in your family, but not to worry. The Aunties are often the gatekeepers of all the juicy family drama, so if you want the inside scoop, make sure to spend some time with them. Be warned that if you spend too much time in their company, two days later you’ll find them planning the details of your future wedding while you—a single, broke, and unemployed university student—look on. The Aunties can be a lot, but we love them anyway.

Be prepared for the questions and comments about your career, love life, and pretty much any sensitive topics you can think about. In fact, if you’re feeling spicy, make some comments of your own. Nothing better than a passiveaggressive comeback to leave an impression.

Bragging about your spice tolerance is probably half your personality, but you never know when the spice (or possible food poisoning) will get to you. Better be safe than have to make the bathroom your second home.

If you’ve managed to get through any large family gatherings without a single awkward interaction, kudos to you. I can’t say the same. There’s little avoiding it, but awkward interactions are no reason to hide in the bathroom and scroll through your Insta feed. Sure, you may have to endure an entire conversation with someone who ‘knows’ you while frantically trying to remember who they are (spoiler alert: it was someone who held you when you were a baby). But if you soldier through those awkward interactions, you’ll get to the good part. Like playing blackjack until 6 in the morning and finding out the hard way that your dad’s side are total casino masters (I lost 250 rupees, but it was worth it). You’d be surprised which family members seem to hide a secret double life—it’s almost always the Aunties.

This one is self-explanatory. The way into a brown family’s heart is always through food. Maybe even bring a dish to share, since there’s no better way to say “I’m a responsible and contributing member of this family!”

In a rare stroke of genius, I once invited a friend along with me, and it was a game-changer. You have someone who you trust and who can act as a buffer. They’re also good company when there's no one your age. Just make sure to introduce and include them in any conversations to make them feel welcome. It’s a win-win situation—your friend gets to enjoy the free food, scandal, and general good vibes, and you get to exploit them as a convenient exit strategy.

Don’t attack me for this one. Years ago, I used to pretend that I liked watching cricket so that I could have a common interest with everyone, but now I actually love it. So fake it till you make it I guess.

Words by Kiran Patel (he/they)

Words by Kiran Patel (he/they)

Not knowing your native language is like being on an episode of The Chase, waiting to get caught out.

Let me explain.

The predominant parts of my identity are pretty evenly split between my two home cities. In Wellington, I’m one with its creative coolness. My passive enjoyment of Lorde and Fat Freddy’s Drop matches the ‘chill but not so chill’, climate anxious, wacky maximalist vibe we have going on here. I’m the everyman strutting through Newtown with a pair of Dickies on and a dream.

Here, I’m Kieran with an e, sans the ethnicness. It’s fair to say that my adult, Westernised self has been strongly shaped by the wiley winds and poor public transport of Pōneke.

When I return to Auckland, my unfortunate birthplace and where most of my extended family still lives, I become Kiran again—sans the e, full ethnicness. My dormant melanin is brought forth from the ether, backed by a symphony of horns and over-the-top special effects à la cringey Indian soap operas.

Don’t get me wrong, I love my culture. In fact, it’s always been the part of my identity that I cherish the most. My childhood in Auckland is entirely rooted in it. Memories of turmeric-stained kitchen benches, old Bollywood movies looped on the TV, and the organic smell of nag champa floating around the house always bubble to the surface during these visits.

As an adult though, being around my extended family for too long prods a little too sharply at my insecurities. Why? Because they speak an entirely different language to me. No, literally.

Anytime a family members asks me a question in Gujarati, my native language, it usually plays out like this:

The bright studio light beams straight onto my sweaty face as an eager audience watches from the edge of their seats. The pensive music starts to ascend in the background. My brain leaps into overdrive, struggling to sift through years of pop culture references and old Vine quotes to find my shoddy Gujarati-to-English translator. Where the hell could it be?

A vision of Bradley Walsh begs me for an answer as time is about to run out. With milliseconds to spare, I abandon the translation route and decide that the question must be

about food—it always is! I garble out something about not being hungry. My aunty looks confused. My cheeks start to burn. Instinctively, I prepare myself for the humiliating reminder of how whitewashed I am.

“I asked what you’re studying at university,” she repeats in English.

“Oh, haha. English Literature,” I respond dejectedly. Sounds about right, her eyes seem to tell me.

My desire to be perceived as a real Indian has once again failed. Bradley Walsh reappears to echo my entire Gujarati-speaking ancestral line’s disappointment in me. “Unfortunately for you, Kieran, The Chase is over.”

The struggle to understand and speak your native tongue takes the meme of 'just smile and nod y’all' to a whole new level. You’re told to bluff your way through life, but in this case, you’re literally bluffing your way through an extremely important part of who you are. I mean, it’s my language. How do I not know it?

I decided to ask my mum about why she didn’t speak Gujarati to my brothers and I as kids, and basically doom our bloodline to being whitewashed English speakers for all eternity (just kidding, love you Mum). Her answer… was that there isn’t really an answer. “It just happened. Knowing both languages was a gift I took for granted, and I didn’t realise that until you were all grown up. It was too late for me to teach you organically.”

Okay Mum, you’re forgiven. Given that we’re thirdgeneration Aotearoa immigrants, and our day-to-day upbringing was no different from Dave and Debbie down the road, it does check out that speaking English at home would’ve just been a subconscious decision for my parents. But why is that? When I decided to dive a bit deeper, I was shocked to find (not really) that it all comes back to everyone’s favourite c-word—colonisation.

The Crown’s attempts to eradicate te reo Māori in order to establish a Pākehā hegemony probably isn’t new to anyone. The sparknotes version is that the Education Ordinance of 1847 declared that “for reasons so obvious as to not need repeating” (???), all children in New Zealand should be brought up to read and write in English. By the early 20th century, tamariki would be prohibited from speaking te reo Māori on school grounds entirely.

As Dr Rachael Ka'ai-Mahuta notes, stamping out knowledge of te reo Māori through the schooling system provided Pākehā with their best chance to establish long-term cultural dominance. “[Mission schools] sought to interrupt the intergenerational transmission of language and culture, thereby invalidating the world-view of Māori and paving the way for their own world-view to replace that of Māori.”

While I can’t speak to the feelings of tangata whenua, I can certainly empathise with the lasting impact that Pākehā assimilation has had on minority communities across Aotearoa.

Between 1887-1920, stringent immigration laws were put in place to trap English-speaking Asian immigrants in Aotearoa, and keep the so-called ‘undesirables’ out. Our proudly racist government did this because they believed English-speaking migrants could be stripped of their roots more quickly, and would help propagate the colonial dream of a dominant, white Aotearoa.

Even today, assimilation continues to rear its ugly head in our lives. The choices we make as migrants, especially through language, are measured by how useful they’ll be within Pākehā systems. Will speaking fluent English translate to better job prospects? Will hiding my ethnic background mean that I’ll avoid being discriminated against? Will teaching my kids their native language still make them Kiwi enough to fit in at school?

In my experience, growing up assimilated to Pākehā culture and speaking English as my first language has rewarded me with a lot of social mobility. But it feels like the price of that privilege is leaving behind the strength and importance of my Indian heritage. Our rich history and lineage has anti-climatically whittled its way down to me: a poorly-built caricature that has too much of a culture that’s not mine, and not enough of the culture I was born with.

Beyond my own personal embarrassment of my half-sketched cultural identity, my lack of Gujarati skills is actually kind of terrifying when I’m reminded of oral tradition in Indian culture. We’re totally reliant on passing information down through generations verbally rather than through writing. My family’s history is scattered across various elders’ memories, and can only be accessed via hours of conversation in Gujarati. While my Pākehā mates can order a 23andMe and call it a day, I somehow need to learn an entire language before Granny kicks the bucket.

Is this it then? Is my entire family’s legacy set to fall at the hands of my own ignorance?

I don’t think so.

Maybe the opportunity to organically learn Gujarati has passed by me. But rather than being the elusive ‘one that got away’, I’m constantly looking for ways that I can pursue it. There are so many cultural nuances wrapped up in language that I’m still excited to explore for myself.

Language is more than just conversation. Language is culture, and no amount of Google Translate or English subtitles can fill in that gap. But on the flip side to English, Gujarati is about more than just putting the right words together. Making meaning relies on feeling, and that’s something I do know.

The Kieran in me will probably always stick out like a sore thumb. But at the end of the day, my family named me Kiran, which means ‘a ray of light’ in Sanskrit. Even if my ancestors don’t understand the language that I speak, and would probably die again if they saw the life that I live, I’d say it’s pretty damn miraculous that our ancestry has made it to this point in history. With what little light remains, I’ll proudly continue to carry the torch of my culture forward.

CW: Labour Camps, War Related Death.

Being from a refugee background means you have survival mode built in.

When all systems fail, when your brain and body are bursting with emotion, each cell has been wired by your ancestors to problem-solve your way to safety. Even if that means everything has to fall before you get there.

Our bones are strong but hyper-sensitive, brittle but unbreakable. It sometimes feels like I’ve lived a thousand forevers with the number of times I’ve picked my life up from a pile of crumbs. Every time something goes wrong, there is a part of me, a DNA set defence mechanism, instantly ready to escape. A bittersweet superpower, it sometimes scares me the lengths at which my brain can defy me in order to keep my body alive. It’s the reason why, within my mental illness journey, I’ve always been deemed ‘high functioning’. There is a deep need in me to persevere and never break.

Unresolved trauma trickles down into future generations. This is our story.

-Franciszka

✦ ✦ ✦

I am the firstborn daughter of orphaned Polish war refugees. My parents were two of the 733 children invited to New Zealand by Labour Prime Minister Peter Fraser in 1944.

In 1944 there was no trauma-informed counselling available to refugees. They were expected to assimilate into New Zealand life. A 1967 NZ Film Unit documentary Story of Seven-Hundred Polish Children shows them as good New Zealand citizens, working, marrying, and making positive contributions to their communities and society. Outwardly, they were successful. And yet at night, my father had terrible nightmares and my mother saw devils. As a child I witnessed and yet could not understand the behaviours that would erupt. My mother shouting, “Bring my children back to the Land of the Living” — all those she lost haunting her waking with unspeakable memories.

As a child I would find quiet solace in the dark wardrobe, in being a high achiever at school, in the appearance of normalcy. I would become a lecturer at Victoria University of Wellington, and a communications strategist, a business owner, counsellor, and a mother… and yet in times of stress, I would encounter the ghosts of those children lost— depression, anxiety, neurodivergence, PTSD, and post-natal psychosis. I once wrote a university essay, while studying at VUW, in a loo in the Kirk Building. I couldn’t bear the crowded library. I would startle and sometimes hide at a knock at the door that banging at the door in the middle of the night decades before still so loud it made my nerves scream. “Be careful”was the same phrase I found myself saying to my children after my mother said it to me. So afraid she was of losing another one she loved. The unspoken trauma leaked into daily life.

- Stefania.My mother Stefania and I have a shared love for storytelling. We are the descendants of war refugees who passed on all of their strength, and their sorrow, to us.

Our task is to weave healing into words:

Hunted, Haunted, Hurt, Healed, Whole.

Lorraine Singh is a trauma-informed Child and Youth counsellor who offers psychotherapy to refugee background people as part of the Red Cross Trauma Recovery Service. I asked her if there was any science behind using art to release emotional pain. “Creativity can have a positive impact on emotional regulation and help alleviate stress by […] using colours, the senses and attention to detail to create something tangible to make sense of self or the world,” Lorraine explained. In my grandparents’ generation, there was no mental

health support for refugees navigating their trauma, or the confrontational anxiety of starting again in a place where you don’t speak the language or fit in with the culture. Now, the support available to help refugees recover has improved. Mum and I are so grateful.

Displacement is embedded in my family line, huddled in the depths of our DNA through decades of discomfort. It’s led us down paths between determined drive toward a future, and dissociation to dismiss the hard truths. We remain relentlessly alive. We are confidence-crushed by events out of our control, and we forget to forgive ourselves when it’s not our fault. My ancestors took on each day, becoming friends with the fear that this one could be their last, and building adrenaline anxiety into our genetic code.

“Epigenetics […] shows how the environment influences children’s experiences and actually affects the expression of their genes. Young brains are particularly sensitive to epigenetic changes,” says Lorraine, confirming the impact of trauma on our bodies and genetic systems. Unfortunately, as much as we might want to, we can’t only pass down the good. Pain intertangles all of us. The body holds it.

My grandparents were young when they became war refugees. Their innocence drained to a drop, bodies broken down to skin and bone. Forcibly removed from their homes and into Siberian labour camps. Waiting, watching, as parents, siblings, and other loved ones were wrongfully taken right in front of their eyes. At age 9, my grandad had to parent his young siblings. Forced to be headstrong, his heart learnt to harden.

✦

My father watched his father get shot on the platform where Russian soldiers were loading his family onto cattle trains bound for Siberia. On the journey there, his mother fell under the train, missing his outstretched hand as she raced to board the moving train carrying a pail of milk. He was 9 and left alone to care for and feed his 7-year-old sister and 2-year-old brother.

My mother was 9 when she arrived in New Zealand. By this time, she had witnessed the death of three of her siblings from illness and starvation in the Siberian forced labour camps. She had then watched her mother die of a gangrenous leg wound. Her father and eldest brother had left to join the Polish Army, and until the 50s were thought to have been lost.

My grandmother had to be her own emotional support, with her mother, favourite sister, and brothers sickly snatched. None of their belongings to hold close and sentimental, left with only emotional baggage.

Finally, in 1944, a light shone upon them. Alongside 731 others, they were taken in to become the Polish children of Pahiatua. 56 years later, I was born half-Polish and given a Polish name, Franciszka Pietkiewicz. I am eligible for a Polish passport, but I’ve never been there. I have no real connection to Poland. My full-Polish mother and aunties don’t speak the language. My grandparents held it all in, too hurt to tell their children stories or teach their native tongue, except for the words to ‘Sto lat’: the Polish celebration song we sing each Christmas.

I’m grateful for Aotearoa. Pōneke has been my home, and has held me. Unlike my grandparents, I haven’t had to flee. But in 1944, society wasn’t equipped to protect us, and it’s still not. The memories haunted them in silence as they learned the language of this country’s colonisers and how, to their best ability, to blend in.

“Children learn by observing and learning stress responses from those closest to them. The environment children are exposed to since birth can have major impacts on them,

for example, living with an adult who has been traumatised by war who cannot manage their own distress or anger. […] Intergenerational transmission [or intergenerational trauma] is a complicated topic,” says Lorraine.

My parents’ early trauma wove itself into the genetic blueprint I inherited, and into the one I then passed on to my daughter and son. I was already an egg in the foetus of my mother as she was carried in her grandmother’s womb. It would take until the early 2000s and the work of Rachel Yehuda at Mount Sinai to confirm that intergenerational trauma is passed on through DNA—often becoming visibly acute in the second or third generation. The work of Peter Levine, Bessel van der Kolk, and Gabor Maté have also confirmed this hard gift. It is an inheritance which has bestowed immense gifts of creativity (our family are gifted writers, painters, artists) along with mental illness and adaptive neurodivergence. The psyche and the body held memories that had no way of being processed or integrated. Our eyes are trained to notice details, our bodies are hypervigilant and multi-sensory. Our intuition is an acute attention to all unseen and seen detail to ensure we survive. It would take till my late 40s before I could see, understand, and work with this.

I was confronted by my disconnection from my ancestral home once again last year. I remembered Mum saying the part of Poland we were from was now Ukraine. Our last name meant Peter, Son of Kyiv. I suddenly realised my grandparents’ past had begun to repeat itself. Our home was being destroyed again, and this time, I was watching it happen over Instagram. Mum and I reconnected to our intergenerational grief through a TikTok account made for a cat called Stepan. We patiently waited for his posts, wondering whether he remained safe on his escape journey to France.

Refugee genes are built strong and sturdy, from walking miles barefoot in dire conditions. They have to bury their emotions to keep themselves safe. Post-traumatic stress mixes into one’s mindset, marinating a generational ripple of misunderstood mental distress.

My mother has never come out of hurt without new skills and lessons learnt. She taught me to never hold on too hard to hurt and to be open, calm, and caring. We must allow ourselves to openly express and let our ancestors hold us, knowing we can survive. Hurt passes, but we can look within and face it. What does it mean to dive into all the hurt and happiness, and reflectively appreciate it all in harmony, holding hands with all of our ancestry’s inner children?

What has this hard inheritance gifted? Empathy, compassion, an extraordinary strength to overcome adversity, and a lifetime of helping others understand the unconscious and often inherited beliefs and behaviours that limit them. A desire for inclusivity of all kinds and an embrace of diversity… that I am so overjoyed to see is changing the world with my children’s generation. The liminal position of being a refugee gives you the ability to see the assumptions and expectations of the dominant culture in a different way. Healing underlying trauma can be the antidote that society needs. Our biodiversity and neurodiversity are our greatest hope for humanity’s continued survival. The more beautiful world, as Charles Eisenstein writes, requires all of us exactly as we are.

It’s been a long day. Getting up early, walking to campus, lecture, tutorial, lecture, lunch, tutorial. And my sandwich just didn’t cut it as lunch. I am hungry. Tired, cold, and hungry. But oh, do I know a remedy for that. Chop up some onion and mushrooms, scramble a couple eggs, grate a carrot (and apologise to Oma for the sacrilege). Whack that all into a hot wok with garlic and sambal, and toss it together like a man possessed. Throw in the rice you’ve had sitting in your fridge, slather it all in soy sauce and ketjap, and—at last— everything is once again right in the world. It’s a bold claim, I know, but there’s very little that’s better than wolfing down an entire wokful of hot and wholesome nasi goreng.

I’m halfway through my third bowl when I realise that I never would have done this at home. I probably would have had some toast, or snatched a slice of cake. My first thought would not have been to check my Indo cookbook for which soy sauce to use. Since I moved to Wellington, I’m less surrounded by my heritage, especially on the culinary front. No one else around me is making frikadelpan or roti koekoes anymore. If anything, I should be more inclined to make a ham and cheese sandwich now, right?

I think I owe a bit of context. I was born in the Netherlands to Dutch parents. My dad’s family have lived in North Holland for 500 years, but my mum’s great-grandfather started a family in Indonesia (unpacking that colonial history is a story for another day). When her parents came back to the Netherlands, they brought with them generations of mixed Dutch and Indonesian culture. So I tick the ‘Dutch’ box on the census form, but call myself a Eurasian ‘Indo’ (tl;dr: I’m Dutch, but I’m not freakishly tall and can handle spicy food).

On paper, we’re a pretty poster immigrant family. We moved to New Zealand when I was 3, but still speak Dutch at home (much to the struggle of my NZ-born siblings). It doesn’t feel like a big deal— we haven’t got any tricolour flags on the walls, and there are definitely no wayang dolls lurking around. We’ve never really celebrated Koningsdag, Pinksteren, or even Sinterklaas.

So why was it that when I moved to Wellington I started stocking up on fish sauce and sambal? Hell, I even dragged home a 5kg bag of rice from the store. All of a sudden, I was turning to recipe books that I’d only ever skim read. In the first month, I made nasi kuning, orak arik, and soto ayam, which I’d never made before. Don’t get me wrong, solving any minor inconvenience with fried rice has been fantastic, but it took me by surprise how strong my cultural connection had suddenly become.

To use a cheesy analogy, an old fish asks two younger fish in passing, “How’s the water?” The younger fish swims on, then one turns to the other and says, “What the hell is water?” My point being: at home, Indo culture is like the water. It’s everywhere, and thus nowhere. But all of a sudden—fish out of water—I’m in a world where the only agent of my culture is myself.

Coming to VUW has meant diving into the most awesome mix of variety and expression I’ve ever encountered. There are people here from all walks of life—it can be easy to fade into the sea of difference. But no one has my cultural background. It’s something uniquely personal for me to hold on to. I can stand out a little when I wear my batik shirts, or my wonderfully obnoxious jersey with ‘Nederland’ across the back. Seeing the myriad of cultural groups at the Clubs Expo and meeting other immigrant kids is comforting. We’re connected in our differences.

At home, I can introduce my flatmates to beschuit and poffertjes in return for a 'proper' butter chicken and the advice that Yorkshire puddings are awful. The flipside of my agency is that I don’t have to. I can keep it to myself when I want to devour a wokful of nasi, or keep a stash of speculaas. Unlike the bread and butter in the fridge, I don’t have to share my sambal or komijn kaas. And no one can judge me for spinning my BLØF CD on repeat.

Keeping my culture close to heart is important. It’s a direct link to my family and my heritage. I’ve got pages of my ancestors’ stories in my notebook, and moving away means writing my own chapter. It's bittersweet though, after living with my family for 18 years. We moved here together from the other side of the world, and moved many more times around Auckland. Coming to Wellington meant leaving them behind.

For me, food maintains that connection. I can't cook rice without remembering mum teaching me her foolproof method (100% success rate, it’s incredible). Thinking of rendang takes me back to trying to write down my Opa’s unbelievably vague recipe ($20 if you can find any mention of a measuring spoon). Hagelslag will always remind me of my little sister and brother, and I know Calvé peanut butter is my dad’s favourite.

These sentiments are not just mine either. Shifna, who emigrated from Sri Lanka as a baby, strongly relates her food to multiple generations of her heritage. “When I think of food,” she says, “I think of my mum, my grandma, my great-grandma. Mum makes this curry called paal anum, and it’s so warm and comforting. That really connects me. It feels like a hug.”

And for Nuha, since moving from Kashmir a decade ago, food and its rituals helped retain the connection to her roots. “Even though I speak Koshur in broken sentences, food is a big aspect of my culture that, I feel, truly ties me to where I’m from. The experience of coming together to eat wazwan during weddings or during Eid—that stuff really changes you.”

The culture we grew up in doesn’t just disappear when we move away. Habits and lessons we learnt stay with us. My flatmate Jordhveer, whose parents emigrated from Punjab, says, “If I'm making other food I tend to put an Indian twist on it, make it with Indian techniques [...] and the flavours I've been brought up with.”

For all of us fish out of water, it’s food that really connects us with who and where we’ve come from. Food symbolises more than just the means to survive until dinner. “Because, you know, it's not just food,” says Shifna, “it’s special. There’s connections beyond what you’re eating.”

Whether it’s going out and grabbing a lamb curry wrap from Roti Bay, putting your own twist on nachos, or solving every long day with nasi goreng, food is the strongest link in the chain connecting us to our culture. Recipes carry more than just ingredients and measurements (skip the measurement bit if you’re my Opa). The margins are full of memories and knowledge scribbled in by our ancestors, added to by our parents, and edited by us, ready for the next generation to ask, “What do you mean ‘until it tastes right’? Have you never heard of a measuring spoon?”

Words by Anonymous

It all started 25 years ago. It was five years before I was born, during a period of three years of radio silence between my newly married parents.

I don't know the exact details, nor the entire story, but I'll share what I've heard.

Both of my parents were born in Iraq. My mother left at a very young age and lived in Syria, then Iran, and later returned to Syria. She was forced to live in Iran because the borders were suddenly closed during the war. This scenario has repeated itself numerous times over the years due to wars, diseases, and international conflicts.

Shortly after getting married and having their first baby, my father decided to make the almost impossible trip to seek refuge.

The details from here are scarce, and we've been taught not to ask.

We only know that it was about 18 months before he ended up anywhere, and that he eventually found himself in Australia. We know he travelled through Indonesia first. The boat trip he took to Australia ended in catastrophe, during which many of his friends drowned. Another event he doesn’t speak about, for valid reasons.

After spending several months in Australia at a refugee camp, he was taken to another refugee camp in Auckland, where he spent a year before being granted refugee status. About a year later, the radio silence between my parents ended. Dad showed up at Damascus Airport, called my mother, and asked her to pick him up. She was shocked and speechless—all those years of raising my older brother

without him were about to come to an end. My mother recalls those three years as a period of sadness, with my father presumed dead.

Shortly after, the three of them moved to New Zealand, and my father finally started the life he had dreamt of after going through such extreme challenges to get there. I was born about a year and a half later—the first member of the family to be born outside of the Middle East. We spent the next seven years travelling, experiencing, and making the most of a journey of a lifetime.

My father lived in New Zealand for a total of nine years. He struggled with English, needing constant assistance communicating, and he still does to this day.

He eventually returned to Iraq after the war ended, getting work on an oil rig (his Bachelor’s degree in Petroleum Engineering was of no use in New Zealand). He would visit us several times a year in New Zealand over the next four years. We moved to Australia in 2014 after my younger sister was born, and the rest of my family still live there to this day.

I decided to move back to New Zealand in 2022 to continue studying after high school—an LLB which I barely got accepted into. I wasn't able to get a student loan in Australia as I wasn't a citizen (a frustrating topic that needs another story of its own).

The experience of seeking asylum and immigration was harrowing for my father. He endured a great deal of hardship to secure a better life for me, my siblings, and my mother in New Zealand and Australia. Although his absence for four years was difficult, I cannot begin to fathom the mental toll his experiences took on him. I will forever be grateful for his sacrifices to bring us here.

So many children of immigrants mourn the loss of language. The story in my family is that we all understood Marathi as babies and it faded away as we went to school. Other than a few words and phrases around the house, relational titles, and mantras, neither myself nor my two sisters have picked up much of our dad’s language. When we visit Mumbai, I can’t introduce myself, ask for directions, or hail a rickshaw. But I’m weirdly well-equipped if someone cuts me off in traffic.

My dad has unwittingly passed down the vocabulary from his chaotic life in Mumbai to his three daughters. We have a diverse knowledge of the most vulgar and unspeakable curse phrases in Marathi and Hindi. From the mouths of Mumbai’s gangsters, police, and ultra-wealthy to the ears of three girls in Upper Hutt. The older we became, the more we picked up on, and the more likely it was that he’d explain the niche ones to us. It’s not the cultural inheritance anyone expects to get but, fuck, it’s kind of funny.

So if you ever travel to India and want to pick a fight, here are a few choice words that Duolingo won’t teach you.

Chootiya Cunt

Madarchod Motherfucker

Bhenchod

Sister fucker

Randookli

Little whore

Bhosadi nandan

The loved child of a gaping vagina

Choodo bhagat Slut (man)

Lauda lasoon

Dicks and garlic

Hathi hagla mhanoon sasa hagalya gela

anni bocha phatoon mela

The elephant shat. The rabbit tried to shit like the elephant, then tore its arsehole and died.

Nasheebavar makad hagla

A monkey’s shat on my luck.

My mum’s side of the family has been moving between China and New Zealand since the 1880s, but my Por Por and Gong Gong immigrated to New Zealand in the 1930s and 1950s respectively. One of my favourite foods growing up was my Por Por’s wonton recipe, which my mum turned into a dumpling recipe when I was in my teens. The original recipe has a pork filling, which is delicious but not suitable for my collection of vegan friends in Wellington. I love this recipe because, to me, it represents the connection between my past and my present—traditional food that has been adapted to suit my life in Wellington and that I can share with all the people I love.

Makes 50-60 dumplings.

• 1 onion, finely diced (you can also substitute spring onions)

• 2 medium carrots, grated

• ¼ of a cabbage, thinly sliced then chopped into small pieces

• 5 garlic cloves, finely chopped

• 2 tbsp fresh ginger, grated

• 300g firm tofu

• 3 tbsp soy sauce

1 tsp chinkiang vinegar

• 1 tsp brown sugar

• 50-60 dumpling wrappers (I like the Oriental Cuisine Chiao Tzu skins, but use whatever you can find) White pepper to season

1. Heat a neutral oil over medium heat in a large frying pan. Add the onion and carrot and cook until soft, around 5 minutes.

2. Add the garlic and ginger to the frying pan. Cook until fragrant, around 1 minute.

3. Add the cabbage and cook until soft, around 5-10 minutes.

4. Crumble the tofu into the pan—try to get the crumbles pretty small. Stir through the mixture.

5. Add the soy sauce, chinkiang vinegar, and brown sugar. Season with white pepper. Stir through until the mixture is heated through. At this point, taste the mixture to check the seasoning, and adjust as needed.

6. Transfer the mixture to a container and let it cool down. I usually place the filling in the fridge for a couple of hours.

1. Place a dumpling wrapper in the palm of your hand, and add a small amount of the filling. I find a heaped teaspoon of filling is usually the right amount, but base the amount on the size of your wrapper.

2. Wet the edges of the dumpling wrapper using your finger.

3. Fold the dumpling in half, and pleat to seal. I use a bi-directional pleat with three pleats on each side. YouTube has great tutorials if you are struggling.

You can cook your dumplings however you prefer. I learned from my mum to pan fry, then steam.

1. Heat oil in a pan over a medium-high heat—it should be hot enough that the dumplings won’t stick to the pan.

2. Add your dumplings and allow them to sit in the pan until the bottoms are golden brown—this could be anywhere from 30 seconds to a few minutes depending on your pan.

3. Add around a cup of water to the pan and cover immediately. Steam the dumplings for around 7 minutes.

4. Uncover and transfer dumplings to a plate with a paper towel to soak up excess oil.

Enjoy! I serve mine with rice, vegetables (usually steamed bok choy and edamame), and a dipping sauce made of soy sauce, lao gan ma, chinkiang vinegar, and a little sesame oil.

This is the river.

This is the river where we drink from // where we wash our clothes // where we cry. This is the river that sounds like a flute at night, and a drum in the morning. The river is loud and can only be heard at octaves arranged on pillars of blue.

When babies are born, we dip them into the water, let them kick their toes against the cold rush so that they know what the world feels like.

This is the river where my dad used to play // where his dad used to play // and his, and his. This is the river I became queen. I ruled here for centuries, and everyone respected me. This is my kingdom.