45 minute read

LANDSCAPES ARE PEACEBUILDING MECHANISMS

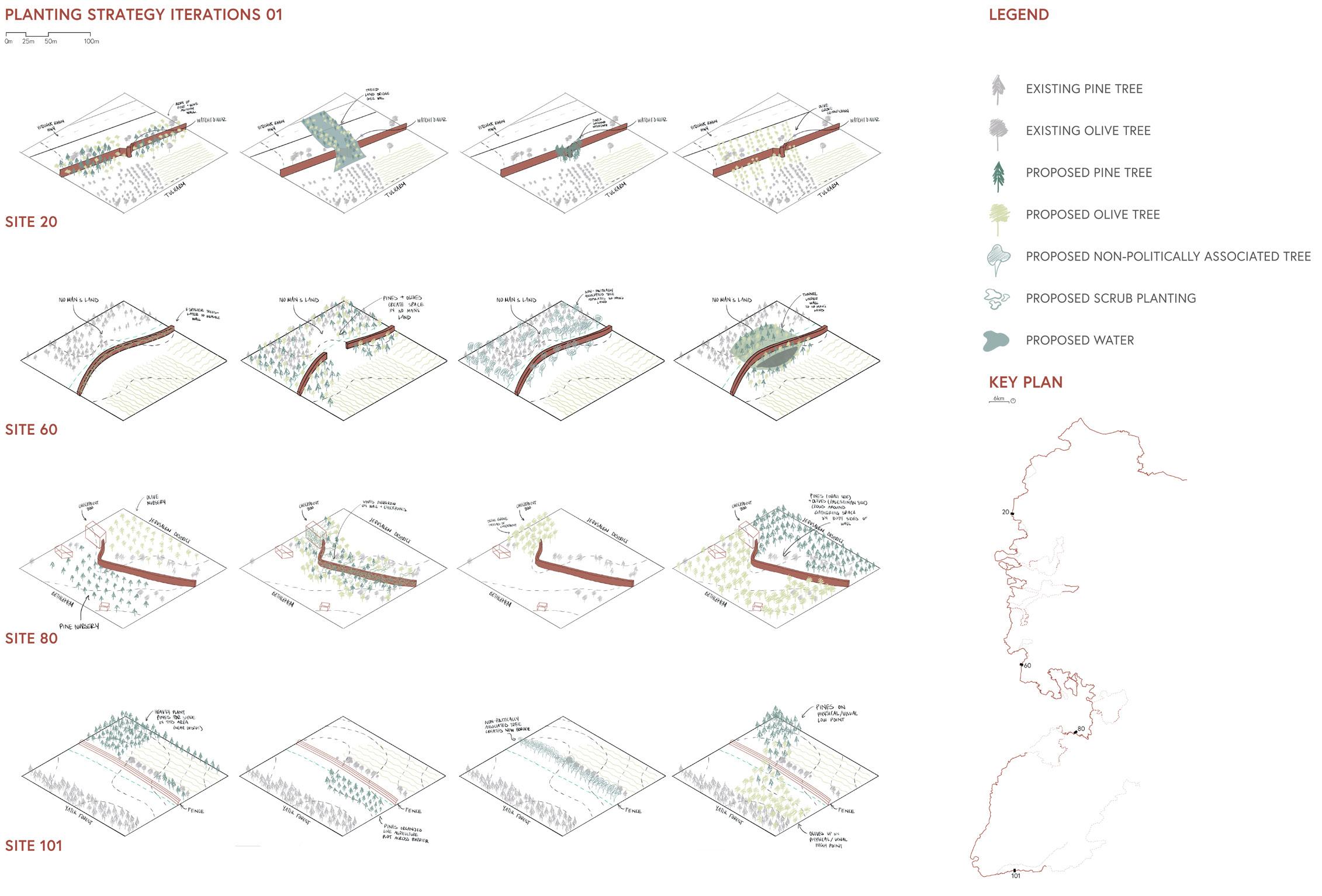

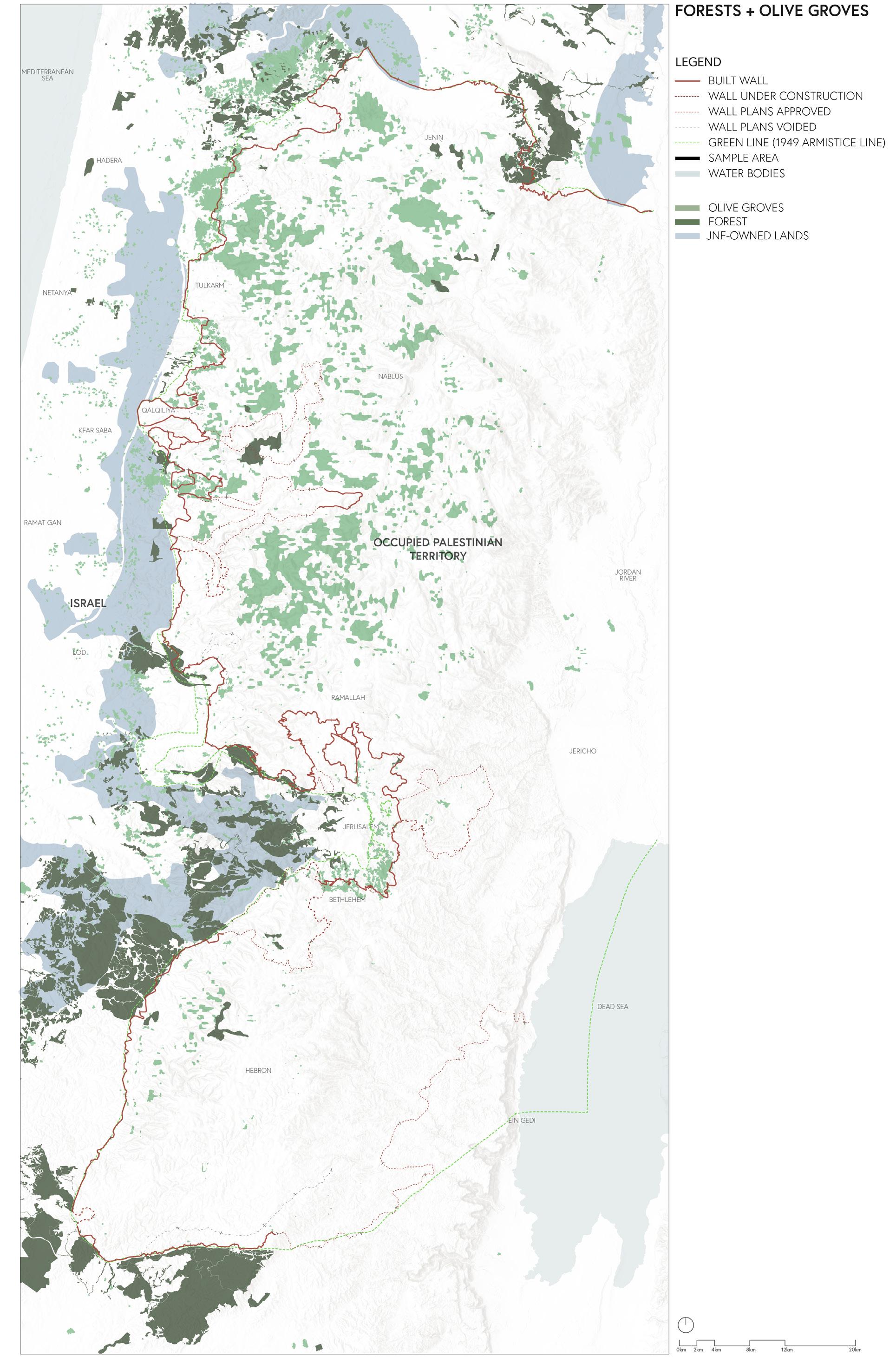

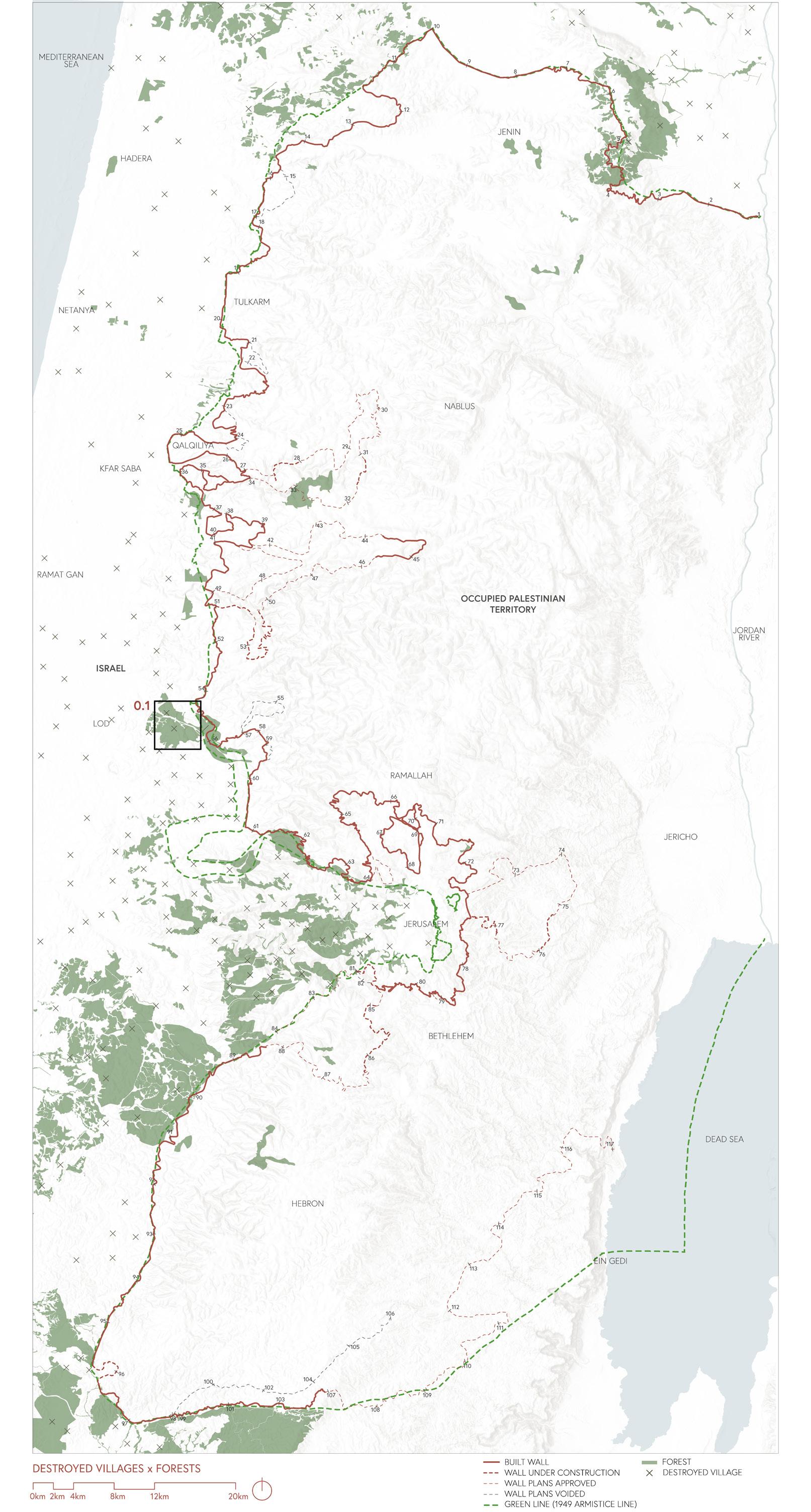

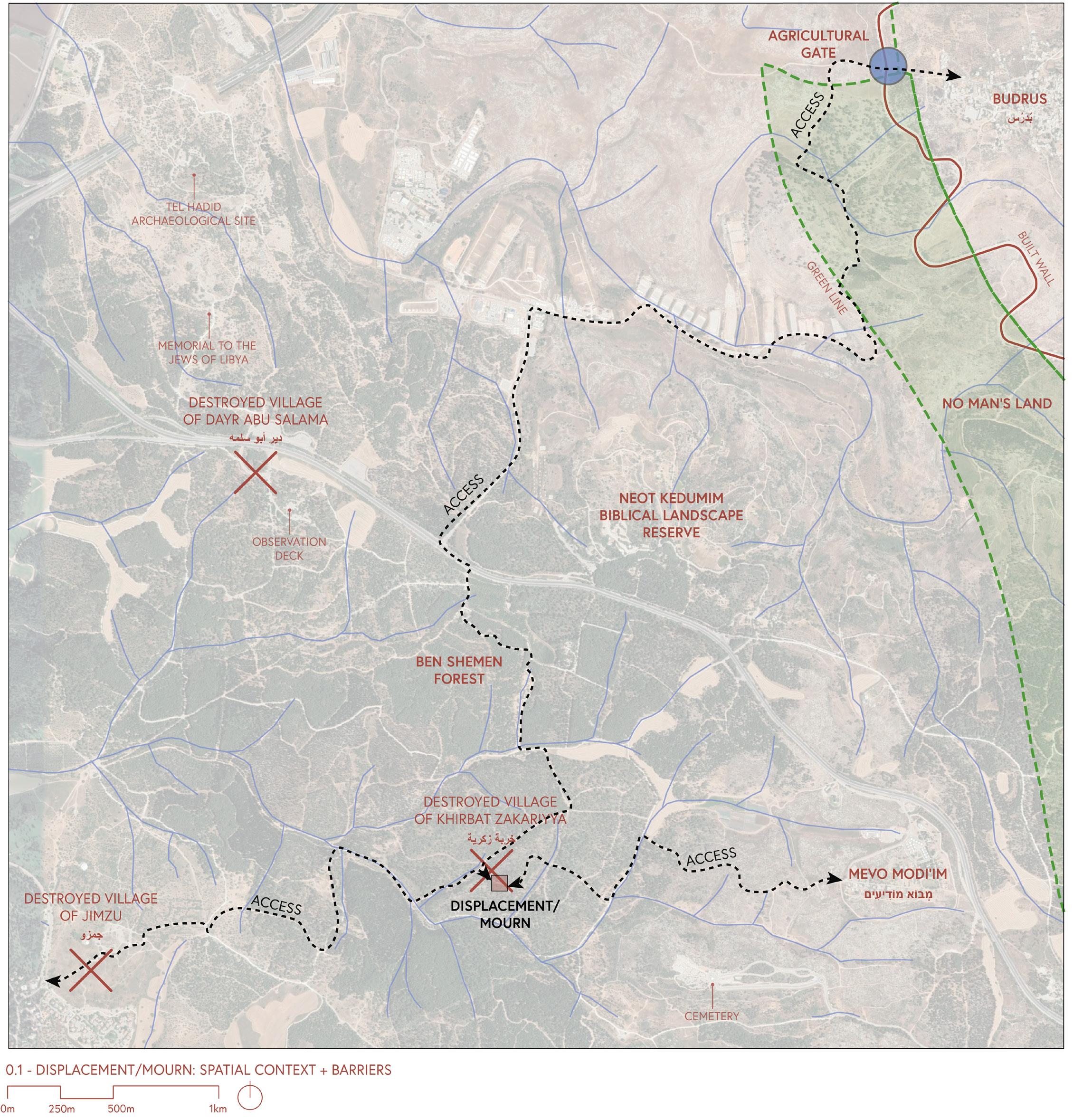

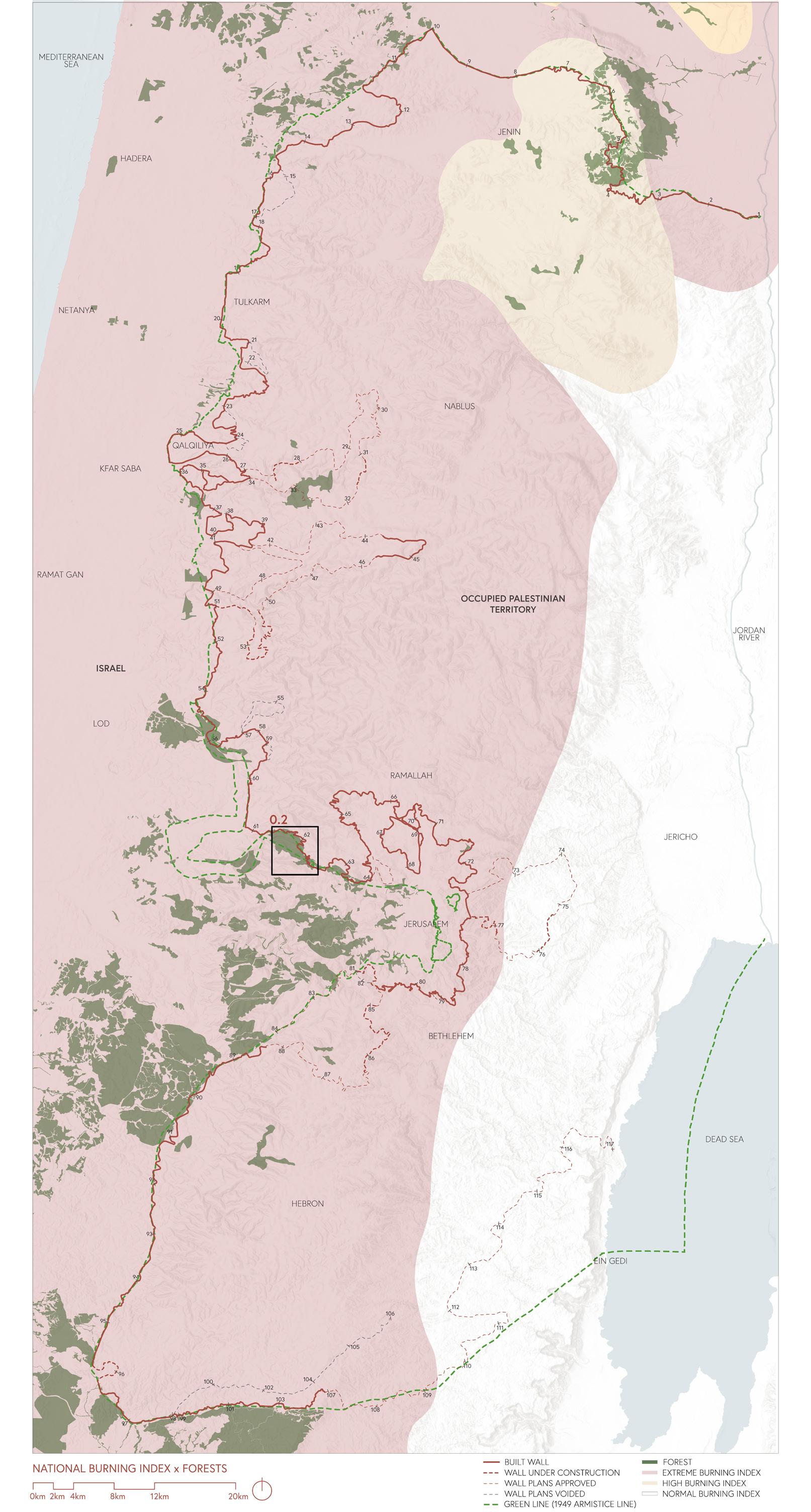

To demonstrate that landscapes are peacebuilding mechanisms and building upon the discussion of the symbolic and cultural importance of the pine and the olive, planting strategies using the pine and the olive were rapidly iterated upon. The sites were chosen from the land use index shown in the previous section, each with a varying condition of wall construction. Strategies tested included creating shared space, deconstructing the physicality or visual dominance of the wall, creating ecologically diverse and rich spaces on both sides of the wall, or using the pine and olive as narrative and teaching tools to tell the stories of collective narratives.

The following set of planting schemes looked to activist groups such as Tent of Nations, Combatants for Peace, the Parents Circle Family Forum, Oasis of Peace/Neve Shalom/Wahat al-Salam, and EcoPeace, as well as Israeli and Palestinian biodiversity reports to see if we could begin healing both the landscape and these two nations simultaneously.

Advertisement

Attitude and Approach to Design

Needless to say, this is a complex topic to tackle and a polarizing subject for many people at the individual and national levels. There are many different possible approaches, and it will take several tries before landing on one that will serve the communities well. New research on healing and psychosocial pathology highlights communities’ invaluable role in mediating conflicts, aside from relying on the institutional level.26 One of the primary attitudes necessary for this project is to suppress the white saviour complex to avoid Western ethnocentricity that may conduct oppressive post-colonial proposals that would not truly respect the cultural nuances of this region.

Throughout this project, I have look closely at my methods and approaches, and stay selfcritical. I will need to make explicit what is in my control and what is not. Power imbalances exist that make interconnected public space difficult to achieve. But, just as gardens can thrive in seemingly extreme or difficult environmental conditions, so can peace.

Shaping Public Space

Much of the literature regarding sharing space in divided places revolves around urban planning schemes.27 This body of work most often acknowledges that public space parallels the enmity and asymmetrical power dynamics within it. However, there is potential to increase instances of encounters between divided communities and break spatial and cultural barriers. In this regard, the principal starting point is to re-think what ‘space’ is and understand that it is socially and physically grounded.28 Secondly, allowing the irregular, improvisation, and messiness to exist in whatever designed space we propose is critical. A space that allows itself to evolve and change dynamically alongside the urban context is far more complex and offers investigation and happenstance.29 While more urban planning related, Gaffikin, Mceldowney, and Sterrett (2010) present a few key considerations to shaping public space in divided cities. First, to ensure that public space should have qualities of identity and inclusivity that all citizens feel they can use and identify with. Secondly, the designer should see themselves as having a role of influence rather than power or control. Thirdly, consider the design strategies that inadvertently encourage surveillance, such as ‘overlooking’ and creating distinct edges to space and borders.30

Education: Storytelling Over Textbooks

In post-war or active-war landscapes, education is a primary practice that influences public discourse and develops individual or societal perceptions and beliefs. However, history textbooks focus on times of war and suffering, painting someone as the enemy and someone as the ally. They tell a curated story of events, choosing which perspectives are shared and which are silenced. Education is essential, especially as more and more people worldwide deny the events of the Holocaust or believe that the separation barrier is simply a security measure and nothing more. The reading and writing of history are especially challenging in a context such as Israel and Palestine where numerous viewpoints and collective narratives are disputed and contradictory. History education should prioritize acknowledging memory and long-lasting trauma to prevent continued aggression and hostility.31 This may involve teaching “acknowledgment, truth-telling, apology, repair, and democratization” and “recognize the victims of violence and repression, as well as their suffering and need for justice.”32 Israel and Palestinian co-founders of the Shared History Project, Sami Adwan and Dan Bar-On, offered a space for both sides’ narratives to be presented and shared. It is the goal of the Shared History Project to bridge narratives and communities.33 While I am not proposing the creation of a new textbook, it is imperative that through the design of a proposal, physical space emerges that educates visitors on the narrative of the other. As mentioned, dialogue and space to tell stories are two way to educate. However, education is a larger theme that should be explored through landscape intervention. To do this, time must be dedicated to collecting first-hand accounts and the understanding of both side’s recollections of history. This has partially been achieved through the process of writing this proposal, but more work is to be done in collecting a database of narratives.

Conclusion

This project recognizes the emerging literature and existing body of work and methods contributing to studies on conflict and spatial relationships. Several questions regarding active conflict and creating spaces of peace still remain to be addressed because previous studies have almost exclusively focused on post-war landscapes, memorialization/commemoration of a past event, or active-war fighting. Other pieces to the puzzle concerning memory, storytelling, dialogue and narratives are disjointed in the body of literature surrounding this context. A new approach is therefore needed to pull these tenets together to share stories and bring empathy to the forefront.

Endnotes

1. Some of the scholarship involving the relationship between war and landscapes includes Björkdahl and Buckley-Zistel (2016), Braverman (2008), Helphand (2006), Mostafavi (2017), and Pearson (2012).

2. Fionn Byrne, “Verdant Persuasion: The Use of Landscape as a Warfighting Tool During Operation Enduring Freedom,” Journal of Architectural Education 76, no. 1 (2022), 37-38.

3. Byrne, “Verdant Persuasion,” 39.

4. Byrne, 43.

5. Gary Fields, “Landscaping Palestine: Reflections of Enclosure in a Historical Mirror,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 42, no. 1 (2010), 64.

6. Fields, “Landscaping Palestine,” 75.

7. Ella Ben Hagai, Phillip L. Hammack, Andrew Pilecki, and Carissa Aresta. “Shifting Away from a Monolithic Narrative on Conflict: Israelis, Palestinians, and Americans in Conversation,” Peace and Conflict 19, no. 3 (2013), 298.

8. Silvia Hassouna, “Spaces for Dialogue in a Segregated Landscape: A Study on the Current Joint Efforts for Peace in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict,” Conflict Resolution Quarterly, vol. 34, no. 1, 2016, 58.

9. Hassouna, “Spaces for Dialogue in a Segregated Landscape,” 59-60.

10. Hassouna, 61.

11. Hassouna, 60.

12. Such tales of epiphanies include that of Rami Elhanan and Bassam Aramin. Their stories are ever-so-poetically detailed in Apeirogon, A Novel (2020) by Colum McCann, a book that has greatly inspired this project. Additionally, similar themes are highlighted in Letters to My Palestinian Neighbour (2019) by Yossi Klein Halevi, I Saw Ramallah (2003) by Mourid Barghouti, and in the work of Peace Heroes, Just Vision, Ali Abu Awwad, and more.

13. Hassouna, 63.

14. Some written works that discuss memorialization and commemoration strategies include Pirker, Rode and Lichtenwagner (2019), Stevens and Franck (2016), Stevens (2013), Björkdahl and Buckley-Zistel (2016), and Mohammad (2017).

15. Anita Bakshi, “Modes of Engagement” in Topographies of Memories: A New Poetics of Commemoration. Secaucus; New York: Palgrave Macmillan (2017), 213.

16. Anita Bakshi, “Introduction” in Topographies of Memories: A New Poetics of Commemoration. Secaucus; New York: Palgrave Macmillan (2017),

12.

17. Bakshi, “Modes of Engagement,” 237.

18. Bakshi, “Modes of Engagement,” .

19. Anita Bakshi, “Chapter 7: Materializing Metaphor” in Topographies of Memories: A New Poetics of Commemoration, Secaucus; New York: Palgrave Macmillan (2017), 272-275.

20. Bakshi, “Materializing Metaphor,” 281.

21. Anne Whiston Spirn, “A Rose is Rarely Just a Rose: Poetics of Landscape” in The Language of Landscape, New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press (1998), 216.

22. Whiston Spirn, “A Rose is Rarely Just a Rose: Poetics of Landscape,” 216-217.

23. Bakshi, “Modes of Engagement,” 237.

24. Annika Björkdahl, “Urban Peacebuilding,” Peacebuilding 1, no. 2 (2013): 208.

25. Björkdahl, “Urban Peacebuilding,” 211.

26. David Senesh, “Restorative Moments: From First Nations People in Canada to Conflicts in an Israeli–Palestinian Dialogue Group,” In Peacebuilding, Memory and Reconciliation, edited by Charbonneau, Bruno and Genevieve Parent, Routledge, 2012, 163.

27. The literature surrounding shared public space in divided contexts include Björkdahl (2013), Bollins (2021), Brand-Jacobsen and Frithjof (2009), Calame and Charlesworth (2011), Gaffikin, Mceldowney, and Sterrett (2010), and more.

28. Frank Gaffikin, Malachy Mceldowney, and Ken Sterrett, “Creating Shared Public Space in the Contested City: The Role of Urban Design,” Journal of Urban Design 15, no. 4 (2010): 497.

29. Gaffikin, Mceldowney, and Sterrett, “Creating Shared Public Space in the Contested City,” 498.

30. Gaffikin, Mceldowney, and Sterrett, 499-500.

31. Karina V. Korostelina, “Can history heal trauma? The role of history education in reconciliation processes,” in Peacebuilding, Memory and Reconciliation, edited by Charbonneau, Bruno and Genevieve Parent, Routledge, 2012, 196.

32. Korostelina, “Can history heal trauma?,” 197.

33. Korostelina, 202.

Part 3: Precedent Studies

Introduction

This precedent study examines three projects and dissects the strategies engaged in creating meaningful landscapes within complicated or divided contexts. There are countless approaches to embedding meaning into landscape design. Some methodologies reviewed within these projects include symbolic or metaphoric exemplification, satirical or ironic art, harvesting local materials, and community engagement. The Freedom Park, the Walled Off Hotel, and the Melon Neighbourhood Commons demonstrate that creating connections and new memories with place does not need to involve western modes of memorialization. Western, top-down commemoration strategies often include national museums and memorials that often highlight the names of victims engraved on some structure. This notion is especially critical in the lens of this graduate project, in which there is a desperate need for approaches rooted in community, narrative, and collective struggle.

The Freedom Park Location: Pretoria, South Africa

Landscape Architect: GREENinc Landscape Architecture

Year: 2007

Institutionalized racism and racial segregation had existed in South Africa under colonial rule (although less formally) and under the apartheid system established by the National Party. Apartheid created incomprehensible brutality in every aspect of life for Black South Africans, from healthcare to civil and political rights. After the fall of apartheid in South Africa, the Government of National Unity assembled the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) to investigate human rights violations and serve restorative justice. The TRC report included recommendations for necessary reparations, including financial, community, and symbolic reparations.1 One of the outcomes of the TRC Report, as mandated by President Nelson Mandela, was The Freedom Park. A park project offered a form of symbolic reparation to begin the process of cleansing and healing at a national level. The park design process began with adopting the notion of ubuntu, the African philosophical tradition stressing the existence of common humanity and the need for forgiveness as a precondition to reconciliation.2

Freedom Park intends to address the collective trauma of colonialism and apartheid. The design includes the use of metaphorical exemplification, symbolism, and draws on Indigenous knowledge systems to inform the designed components.3 Firstly, the park’s construction demolished colonial ruins of Fort Tullichewan, dating back to the late 1800s and the first Anglo-Boer War (between the British and the self-governing Afrikaner). This initial act intended to sever the link between memory and place to create and enforce a new symbolism.4 The park is situated on a quartz ridge, rich in biodiversity, obliging the designers to undertake a level of sensitive planning to conserve as much of its natural state as possible. Those plants that were removed were transferred to a nursery until they could be returned to the landscape.5 Nestled into the slopes of the landscape, the park and connected museum are to reveal themselves more subtly than the surrounding monuments do.

Many of the symbols and metaphors derive from nature’s core elements of earth, water, fire, and air. Each design component is named in a different official language, seeking to unite different cultural groups by giving them each equal stake and recognition in the park.6 For example, an Nguni word, Isivivane, was used to name the space of ceremonial trees and boulders, symbolizing the resting place of those who died in the struggle for freedom. Each boulder underwent ritual healing and cleansing before being brought to its final resting site.7 The siSwati word, S’kumbuto, is the name given to the memorial wall commemorating those who died in major South African conflicts and a Sanctuary for quiet contemplation and reflection near the lake.8 The winding path, with stops to rest and reflect leading to and from the museum, is named after the Tshivenda word for success or progress, Mveledzo. 9

The materiality assists the narrative and delivers symbolic meaning throughout the entire park. Water is one key element carried in many forms throughout different park spaces. The symbolism of water is consistent across tribes and plays a role in healing and traditional cleansing rituals. The use of red clay brick intended to create a symbolic material connection with the boulders, reflect the red soils of the hill and set the stage to emphasize vertical elements of steel and timber.10 Some of these vertical elements derive from the African philosophy of creation and symbolize the progress in the struggle for freedom. Or, in the case of the line of reeds, the vertical element represents communication between heaven and earth as reeds are used to communicate to higher powers through ancestors in Swazi and Zulu cultures.11

Evaluation

The politics of memory and memorialization often do not accurately acknowledge cultural discourses and are influenced by Western methods of commemoration. In this case, the project aimed to tell a new story- correct narratives about pre-apartheid Africa and reclaim that Africa’s significance is pre-colonial. There is no shortage of successful integration of tradition, Indigenous knowledge, and cultural symbolism. While the argument can be made that not all visitors will understand or appreciate these metaphors or symbols, I argue that is precisely the point, that it is not for them. Instead, this project aims to heal, reconcile, and address the psychological damage of colonialism and apartheid by incorporating meaningful symbols to oppressed groups. Of course, one of the museum’s main goals is to increase tourism; however, it goes further than that. Those who wish to learn may learn from the signage and descriptions, but this project represents a progression forward in history for local communities. The extensive consultation process with youth, women, traditional healers, labour groups, veterans, nationwide surveys, and more12 maintains that the overall concept evolved in democratic and transparent means into a symbol of national identity. Some criticism suggests that still, some of the design components are eurocentric, such as The Wall of Names or the Eternal Flame, and that some (mostly white conservatives, but some not) did not identify with the themes of the park and felt some perspectives on history were left out or skewed.13 Strategies of commemoration will always be controversial and not without challenges, especially ones that deal with a national identity. Perhaps there is not enough left to interpretation, or is there too much? It must be accepted among the design community that monumental spaces will be interpreted and re-interpreted in conjunction with culture and memory.

Takeaways

This project employed strategies worth considering moving forward into this graduate project’s conceptual and design phase. Symbolic representation is difficult to achieve and even more so in a divided community for whom symbols might have different connotations or whose collective narratives are competing. However, shared symbols and widely accepted feelings of trauma, loss, and the struggle for liberation may increase empathy and acceptance. However, one of the key takeaways is the recognition and welcoming of flux in interpreting symbols. This project did not explicitly acknowledge that the park’s embedded meaning may change over time, but this notion should be worked into the design intervention. The naming of different programmatic elements in the park with different official languages was a clever way to make each group see themselves in the park. Additionally, the extensive consultation process and integration of traditions and traditional ways of knowing makes new connections between people and place. While a consultation with the public is not within the scope of this graduate project, understanding tradition and connecting the commonalities between two peoples’ traditional ways of being will be critical to shaping long-lasting memories to place.

The Walled Off Hotel

Location: Bethlehem, Palestine

Designer: Banksy

Year: 2017

“The Walled Off, an art hotel set within slingshot distance of Checkpoint 300, was opened by the graffiti artist Banksy in 2017. It stands within yards of the high concrete barriers. Even the most expensive rooms only get a few minutes of direct winter sunlight each day: the shadow of the Wall is cast down into the rooms and can be tracked as it crosses the carpet. The maids can tell the time of day by how much of the carpet is shadowed.”14

– Colum McCann

World-renowned British street artist under the pseudonym Banksy opened the Walled Off Hotel for tourists, Israelis, Palestinians, and vandals alike. This project is rather controversial, located just five meters from the separation barrier in the Palestinian town of Bethlehem. Banksy is known for his politically charged street artworks, some of which are painted on the Separation Barrier in numerous locations. The hotel boasts of offering the “worst view in the world”15, that of the contested wall, which to some is a security measure and to others a symbol of oppression and dispossession. The hotel is called an ‘art hotel’ as it contains a museum and displays an extensive collection of street art and ironic or symbolic materials. Banksy created the museum precisely 100 years after the British took control and occupied Palestine, saying, “I don’t know why, but it felt like a good time to reflect on what happens when the United Kingdom makes a huge political decision without fully comprehending the consequences.”16

The hotel comprises several hotel rooms for overnight stays, a bookshop, a gallery featuring works created by exclusively local artists, a piano bar decorated like an English gentleman’s club, referencing Britain’s colonial rule, and a museum ‘dedicated solely to the biography of the wall.’17 One of the most under-acknowledged facets of the conflict today is the influence of the British in the region, both past and present. Banksy’s choice to decorate the piano bar in the way he did reveals the underpinning of the conflict’s geopolitical roots. Hotel staff serve tea and scones as visitors sit on leather couches beside a wall covered with security cameras affixed to wooden plaques as if they were dead animal heads in a hunting lodge. Being directly adjacent to the separation barrier, guests may sit and enjoy the ugly stain on the landscape in all its stateliness with a beverage in hand. Something is intriguing about the dichotomy of the site and the informality of this program. The wall in Bethlehem and around the hotel is covered in graffiti, the associated store next-door, ‘WallMart,’ even offers stencils and spray paint. The hotel then becomes an engagement with the wall. Allowing and encouraging street art as an active form of resistance is precisely Banksy’s vision with this project and in his works both locally in this land and internationally.

As previously mentioned, this project is controversial. For the local community who are unironically facing the realities of the conflict, some feel that the hotel and Banksy’s works trivialize the conflict18 and hide in the safe confines of humour. It remains unclear how Banksy developed his collection of culturally specific artwork and whether or not he consulted with folks with true life experiences of oppression. For example, one of the rooms boasts a large mural of an Israeli soldier and a Palestinian freedom fighter having a pillow fight. Some Palestinian locals feel that the hotel fetishizes and normalizes occupation,19 feeding the anti-normalization drive mentioned in the literature review section. Others appreciate that the hotel brings international awareness of the conflict and that its profits go directly to the city of Bethlehem.20 The Walled Off Hotel has positively influenced the economy of Bethlehem as numerous new shops and restaurants have taken over abandoned residences since the hotel’s opening.21 While the hotel claims to host anyone and everyone and have equal access regardless of political or national identity, a friend of mine who visited told me that when they went, the Rabbis had to travel to the hotel in the trunks of cars. In contrast, another friend told me she went with a group of Israelis, and they had no issues. This varying set of conditions relating to access highlights the inconsistencies on the ground and tangible barriers to shared space and dialogue.

Evaluation

The aspects of this hotel that make it fascinating in the context of this graduate project are the unique sarcastic and ironic discourses Banksy engages through the art and décor of the hotel and with the adjacent Separation Barrier. Walls like this one represent a nation’s desire or ability to control land and its edges. Graffiti and engagement with the wall directly confront the nation’s ability to control- visually debating and arguing back.22 Author of Conflict Graffiti (2022), John Lennon suggests that projects like this one created by international artists with no regionspecific lived experience often erase the realities of colonized peoples and lands that their work set out to highlight.23 Taking a satirical approach to this hotel was certainly a valid mechanism for encouraging dialogue, reflection, and engagement with the conflict on a different level. Its associated site, art, and décor reveal ideological keystones that challenge notions we think we understand and shine a new light on perspectives of the conflict that are necessary. In a sense, this project is a form of non-violent activism: holding value and principal commentary under the guise of irony and shield of humour.

Takeaways

I have always been intrigued by projects with ironic underpinnings, questioning what makes something art or landscape. Who makes those decisions? World-renowned landscape architect Martha Schwartz frequently addresses these questions, especially with her Bagel Garden. Landscapes may harness form-making and aesthetics to achieve restorative qualities, but they may hold meaning and prompt visitors to leave with new perspectives. As seen with the Walled Off Hotel, locals and tourists alike are immersed in dissonance. A space of cheeky jokes juxtaposed with one of the most severe manifestations of cultural division. Friends of mine who have visited describe it as fascinating in its site and approach to putting the many complicated facets of the conflict into words and art. However, Lennon (2022) makes the excellent point that despite good intentions, Western bias seeps into the work of artists and landscape architects alike. This bias may undermine the difficult issues facing local communities of which they are not a part and which they do not fully understand.24 This bias must be acknowledged, and there should be space in a project such as this for the local communities to actively engage with the concepts and sites the project seeks to address.

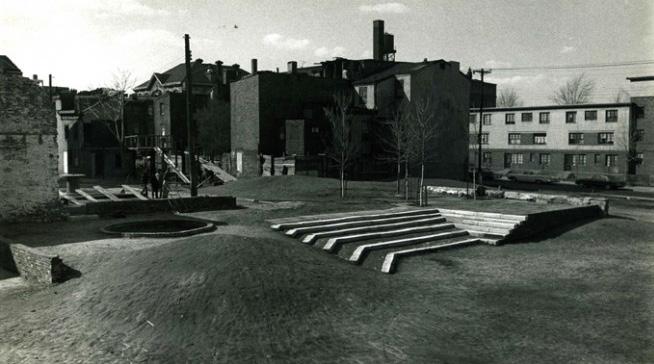

Melon Neighbourhood Commons Location: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Designers: Karl Linn with Students + Community Members

Year: 1960

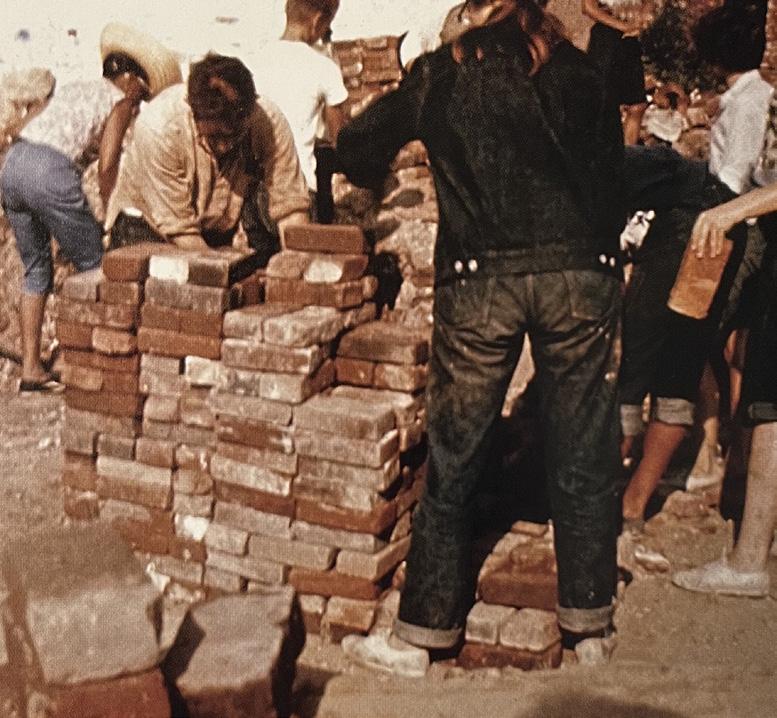

While the prospects of Urban Renewal sought to clear American cities of ‘blight’ and promised ‘slum clearance,’ designers like Karl Linn saw potential in the therapeutic properties of landscapes and their capabilities to heal relationships between communities and the urban city. Urban renewal affected most cities in North America, including so-called Vancouver, where white supremacist and segregationist planners like Harland Bartholomew began redlining marginalized neighbourhoods to ‘clear’ urban cities of the ‘cancer’ of ‘slums.’25 Similar stories of racist urban policies imposed by urban renewal were well underway in Philadelphia, where Karl Linn had been appointed a faculty position under Ian McHarg at the University of Philadelphia in 1959.26

Fearing Nazi persecution in Germany, Karl Linn’s family fled to Palestine in the 1930s where he helped found a Kibbutz.27 Being very familiar with Kibbutzim myself, as my grandparents met and were married on a Kibbutz, and many family members still live on Kibbutzim in Israel, I understand the sense of community and land stewardship that these places support. Karl Linn moved on to study psychology, but his background in agriculture on the Kibbutz led him to appreciate nature’s role in peacebuilding and healing.28 Linn saw empathy and emotion as potential pathways through which designers could unite and heal broken, segregated, or alienated communities.29 Melon Neighbourhood Commons became Linn’s pilot project in his journey to present an alternative to urban renewal focused on participatory engagement. He re-framed the view of the Melon site from ‘park’ to ‘Commons.’ He imagined that the site would serve as a hub for political activism and social life and strengthen collective identity.30 These goals, he hoped, would be achieved through the careful use and re-use of materials and thoughtful design.

The conceptual design process began by observing neighbourhood residents and how they operated in their current public spaces. He and his design students began observing how residents created spaces for themselves as extensions of their homes and community. They saw a need for safe and accessible play areas for children and accessible open spaces for youth and adults alike.31 After receiving funding and permission to re-envision the site, Linn arranged a meeting between his students and the residents of this primarily Black neighbourhood in hopes that it would support deepened compassion and empathy in his majority white and privileged students.32 Setting the foundation of respect and compassion propelled them into the construction phase, a cooperation effort between community members and students. The team salvaged as much material as possible as Linn believed this strategy would reaffirm community identity.33 In his book Building Commons and Community (2007), he writes:

“In human habitat, as in coral reefs, the incremental historical deposits of a place imbue the physical environment with a feeling of timelessness. Residues of former buildings, trees, and landscape features create an air of familiarity.”34

-Karl Linn

The overall design of Melon Commons was a ‘hybrid urban-naturalist scheme’35 with its amphitheatre embedded among rolling hills. The team saw potential in the existing rolling topography for play and gathering. Flagstones recovered from nearby demolished sidewalks, found boxes of mosaic tiles, and marble salvaged from doorsteps36 instilled a familiar sensitivity on site. Many local craftspeople, servicepeople, and elected officials kindly donated support, time, expertise, and materials, including trees and mechanical augers. As soon as the play equipment had been installed, children flocked to the site and families were relieved when Linn informed them that there would be no limited play hours or access like other parks.37 After completing the commons, the team established the Neighbourhood Renewal Corps (NRC) to rally local volunteers and guide them in other neighbourhood grassroots efforts.38 Moreover, the NRC engaged in many emerging civil rights efforts and imagined futures far beyond Melon Commons. Unfortunately, the felt effects of urban renewal racist schemes and redlining trickled deeper into the Melon Neighbourhood, forcing many homeowners to set their own homes aflame to collect insurance money as they were denied loans for home improvements and conditions deteriorated. This exodus of residents left the Commons’ state to depreciate to the point where it was designated to be demolished. Eventually, the empty lot gave way to fenced-in high-rise construction. In his book, Linn expresses guilt for what happened at the site, wishing maybe he had been there to stand in front of the bulldozer himself.39

Evaluation

Karl Linn set out to oppose the racist prospects of urban renewal at a time when many designers were busy responding to contemporary modernist challenges with new technologies or trying to have dominion over nature. His ethos is unparalleled. He valued community engagement and participation far beyond what many designers now consider engagement or outreach. Melon Commons showed marginalized community members that they can and should see themselves in their public spaces and that they have a stake in such places. While the commons’ design isn’t the most extravagant or outstanding creative expression, it radiates beauty in its cooperation efforts and legacy. Its demise and eventual demolition underscores the evolutionary nature of culture and the impacts of large-scale urban planning failures.

Takeaways

After reading about Karl Linn and his philosophies on design and his works, I saw many parallels between his intentions and mine. I also can understand how his life experiences shaped his viewpoints. Linn and my late Saba both grew up on tree farms and kibbutzim and placed extraordinary value on community participation in shaping the land we live on. In Linn’s design work, one of the primary strategies he employed was using salvaged materials to kindle a sense of belonging and familiarity with the designed space. Moreover, he engaged local community members in the design and construction process so they could feel included in shaping their own public space and make new connections with place. These are strategies that would be wise to adapt to this graduate project. While I cannot physically visit the community and have them aid me in design and construction, there is still room for intended community input and participation on all levels. Additionally, I think there is a lot to learn from this project’s influence following its construction as it attempted to propel civil-rights efforts forward and be a model for equitable urban space.

Conclusion

The three projects outlined in these precedent studies feature a range of approaches to engaging community members, telling stories, and coping with conflict on various scales. While the Freedom Park and the Melon Neighbourhood Commons are not located in the region of Israel/ Palestine, they both offer valuable approaches that ultimately led their communities to feel heard, understood, and respected. The use of irony and humour in Banksy’s Walled Off Hotel may not be as applicable to this project, but it is nevertheless exciting to study its reception by the public and light-hearted take on such a tense site. In conclusion, the projects selected exhibited a need for culture-specific design processes with true intentions to progress forward and reflect on the past or present.

Endnotes

1. “Truth Commission: South Africa,” United States Institute of Peace, December 1, 1995.

2. Michele Jacobs, “Contested Monuments in a Changing Heritage Landscape: //hapo Museum, Freedom Park, Pretoria,” De Arte 51, no. 1 (2016): 89.

3. Jacobs, “Contested Monuments in a Changing Heritage Landscape,” 90.

4. Jacobs, 90.

5. “The Freedom Park,” Landezine, September 4, 2012.

6. Jacobs, 90.

7. Jacobs, 90.

8. Jacobs, 90.

9. Jacobs, 92.

10. “The Freedom Park //Hapo (Museum),” GREENinc Landscape Architecture + Urbanism.

11. “The Freedom Park,” Landezine.

12. Sabine Marschall, “Chapter 7. Freedom Park As National Site Of Identification,” In Landscape of Memory. 2010, 216.

13. Marschall, “Freedom Park As National Site Of Identification,” 231.

14. Colum McCann, Apeirogon: A Novel, First ed, New York: Random House, 2020, 308.

15. Ian Fisher, “Banksy Hotel in the West Bank: Small, but Plenty of Wall Space,” The New York Times. April 16, 2017.

16. Tommaso M. Milani, “Banksy’s Walled Off Hotel and the Mediatization of Street Art,” Social Semiotics, no. ahead-of-print (2022): 1.

17. “Facilities,” The Walled Off Hotel.

18. Milani, “Banksy’s Walled Off Hotel and the Mediatization of Street Art,” 2.

19. Jamil Khader, “Architectural Parallax, Neoliberal Politics and the Universality of the Palestinian Struggle: Banksy’s Walled Off Hotel,” European Journal of Cultural Studies 23, no. 3 (2020): 477.

20. Tristan Davis, “Welcome to the Walled Off: A Visit to Banksy’s Hotel in Bethlehem,” The Jerusalem Post, March 17, 2018.

21. Davis, “Welcome to the Walled Off,” 2018.

22. John Lennon, “Erasing People and Land,” In Conflict Graffiti: University of Chicago Press, 2022, 101.

23. Lennon, “Erasing People and Land,” 102.

24. Lennon, 105.

25. Nicole Dulong, Samantha Miller, and Reece Milton, Hogan’s Alley Site Guidelines (Vancouver: University of British Columbia, 2021), 71.

26. Alison Bick Hirsch, “From “Open Space” to “Public Space”: Activist Landscape Architects of the 1960s,” Landscape Journal 33, no. 2 (2015): 187.

27. Anna Goodman, “Karl Linn and the Foundations of Community Design: From Progressive Models to the War on Poverty,” Journal of Urban History 46, no. 4 (2020): 796.

28. Goodman, “Karl Linn and the Foundations of Community Design,” 796.

29. Goodman, 796.

30. Goodman, 797.

31. Karl Linn, Building Commons and Community, Oakland, CA: New Village Press, 2007, 81-82.

32. Linn, Building Commons and Community, 83.

33. Goodman, 798.

34. Linn, 84.

35. Goodman, 798.

36. Linn, 87-89.

37. Linn, 89.

38. Linn, 90.

39. Linn, 96-97.

Part 3: Stories and Counter Stories

Looking to the olive, the pine, and other landscape architectural practices, the following three design proposals are framed as stories/ counter stories. Each story is chosen due to its proximity to the wall, its exemplification qualities of being used as a weapon or nation-building tool, and its opportunity for peacebuilding or healing at different scales. They begin with a description and example of a specific site and strategy in which the olive or the pine has been used as a proxy-soldier or proxy-nation-builder. Then, a counter-story (the design proposal) is offered to begin healing lands and nations simultaneously. In this way, we can acknowledge facts on the ground, power imbalances, and traumas and respond to them with empathy.

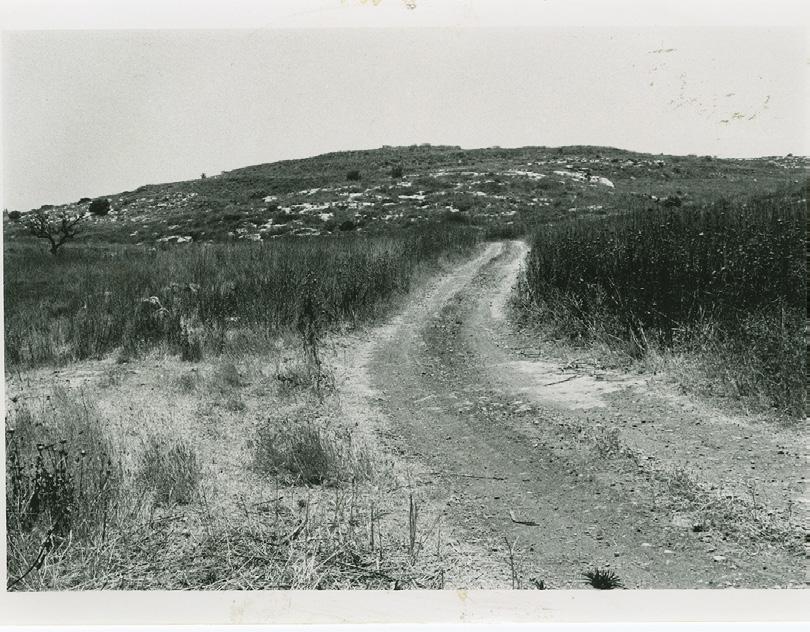

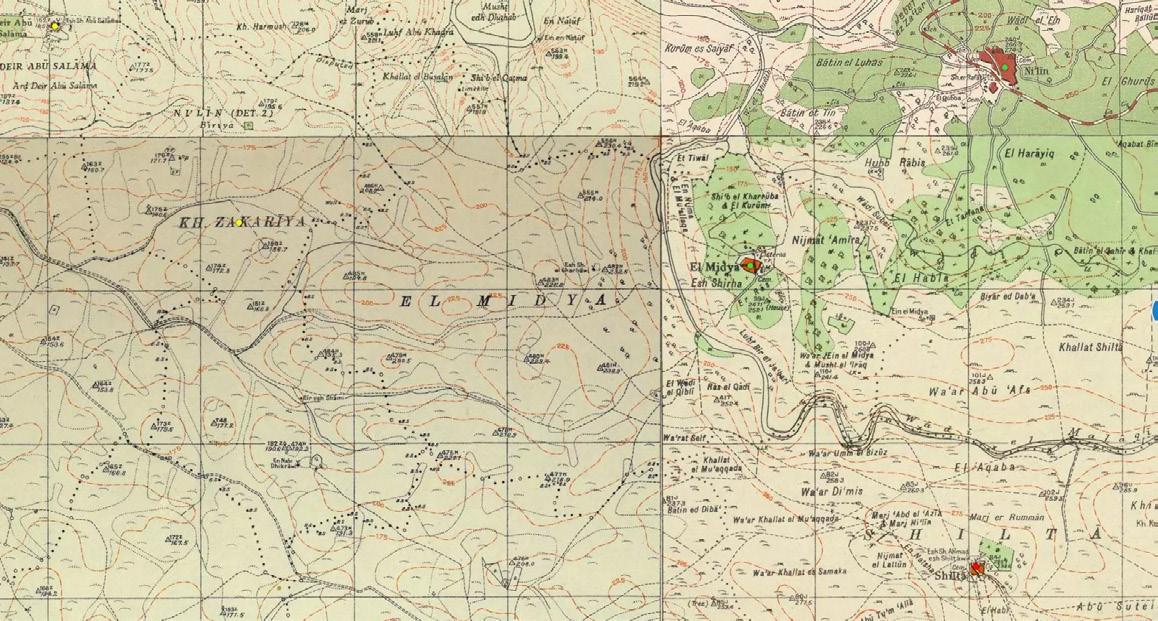

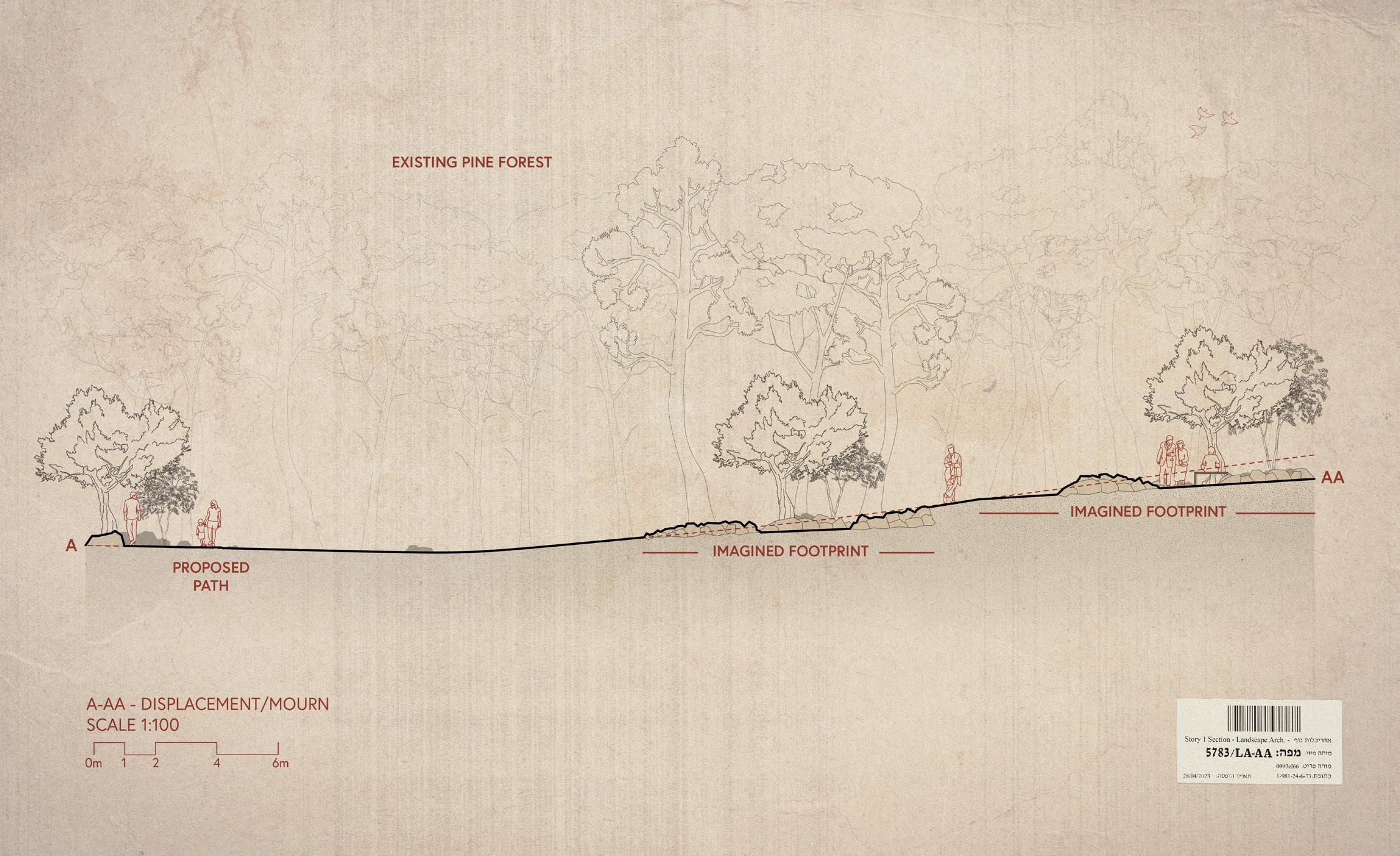

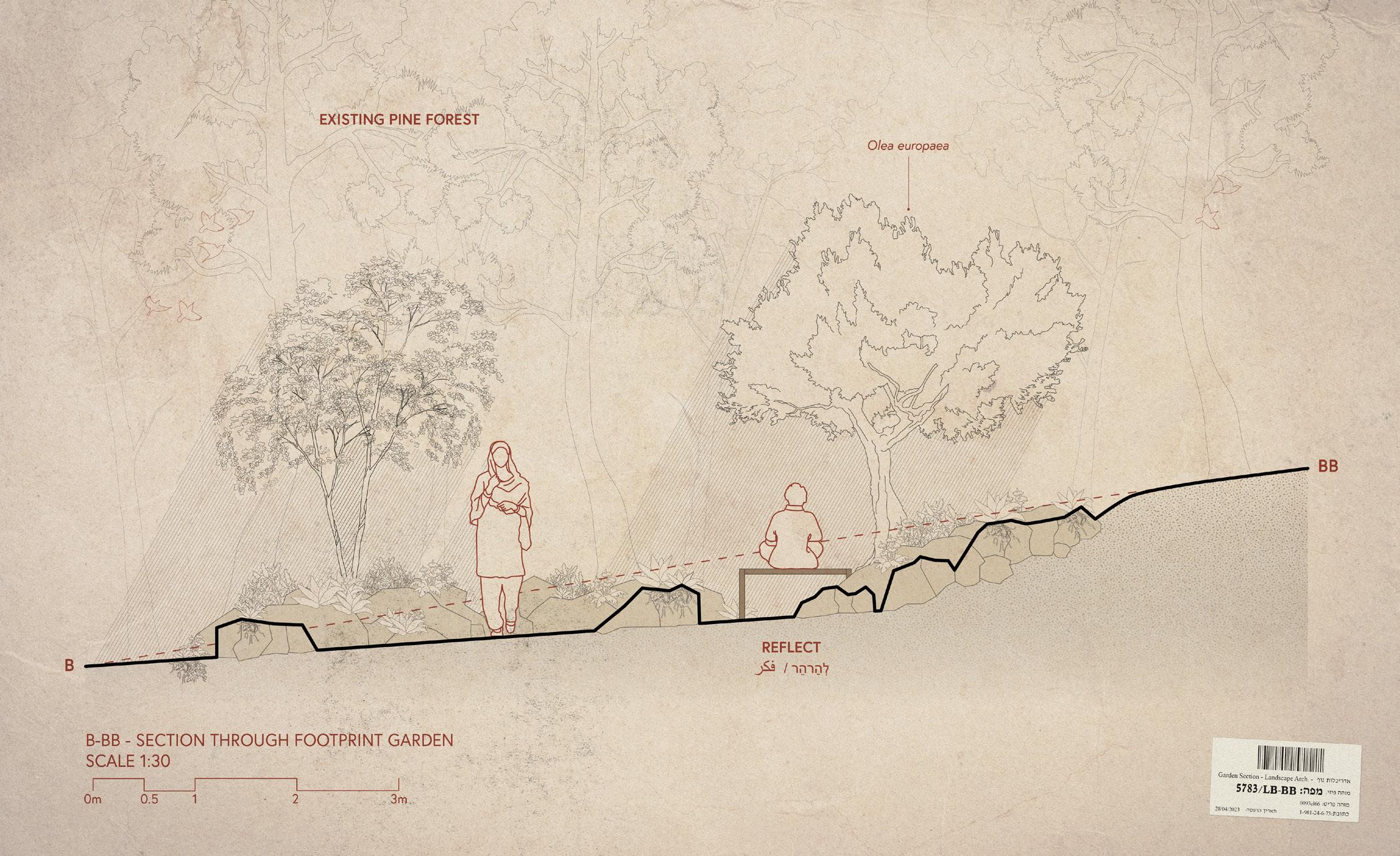

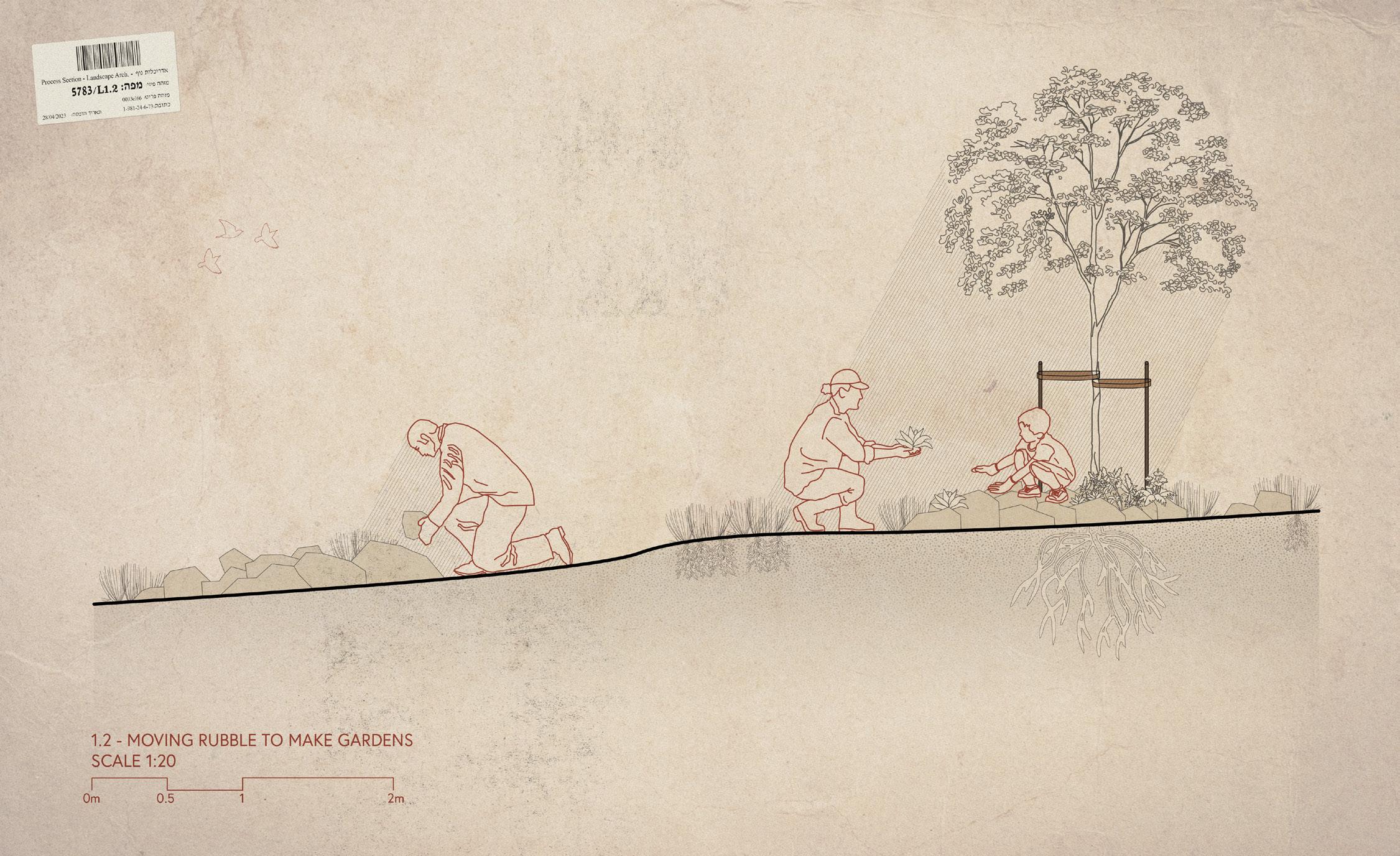

Displacement

The site of this intervention is what is now known as the Ben Shemen Forest, located near Ramallah. The forest is primarily comprised of pines planted by the JNF. The vast forest lands sit on the sites of destroyed Palestinian villages, depopulated during the Nakba in 1948 or in the Six-Day War of 1967. A practice of erasure that is far too common amongst the sites of JNF forests. Of the 418 Palestinian villages displaced during the Nakba, almost half are now the locations of nature parks, forests, or nature reserves.1 This fact is often a prominent proponent of debates surrounding the heart of the JNF’s intentions, some arguing that their afforestation policies were meant to prevent Palestinians from returning home, forcing them to find a new home elsewhere in the surrounding Arab countries.2 The sites of these destroyed villages are left in varying conditions under these pine trees. The focus of this story is the remains of Khirbat Zakariyya. According to Palestine Remembered, the 4500+ inhabitants of Khirbat Zakariyya/ ةبرخ ةيركز were completely displaced from their lands and homes in 1948.3 Palestinian historian Walid Khalidi describes the remains of the village today by writing:

“From a distance, the village appears as a bare hill overgrown with thorns and other wild vegetation. The remains of village wells and the cut stones that were used to cover them are visible.”4

-Walid Khalidi

Mourn

Political violence blurs the boundaries between the “war front” and the “home front.”5 One study on Palestinian women’s mental well-being found that anxiety and grief were consistent as there is agony in being unable to derive comfort within their environment.6 There are numerous tales of incredible internal breakthroughs occurring through seeing the ‘other’ grieve. Palestinian activist Ali Abu Awwad grew up in a politically active family, participating in resistance efforts which got him arrested. After being released from prison, he found was shot in the leg during the Second Intifada, and later, his brother was killed by a soldier at a checkpoint. He was chockfull of anger, grief, and pain. Eventually, he joined the Parents Circle Families Forum. In his 2015 Ted Talk, he expressed his shock after realizing Jews had emotion and could cry. Now, he works to spread a message of non-violent activism and reconciliation.7 A similar tale is told in Apeirogon: A Novel by Colum McCann, based on the true-life friendship of two grieving fathers, one Palestinian and one Israeli. McCann describes the Israeli father attending his first meeting at the Parents Circle Families Forum (an organization created to gather grieving people who want peace), writing:

“On and on they came, so many of them… And I remember seeing this lady in this black, traditional dress, with a headscarf- you know, the sort of woman who I might have thought could be the mother of one of the bombers who took my child. She was slow and elegant, stepping down from the bus, walking in my direction. And then I saw it, she had a picture of her daughter clutched to her chest. She walked past me. I couldn’t move. And this was like an earthquake inside me: this woman had lost her child. It maybe sounds simple. but it was not. I had been in a sort of coffin. This lifted the lid from my eyes. My grief and her grief, the same grief.”8

-Rami Elhanan via Colum McCann

When a person dies, the most common Jewish practice, regardless of the degree of religiousness, is to sit Shiva. Shiva is a seven-day mourning period in which the bereaved receive visitors to pray, eat, and be comforted at their homes. There is a powerful notion here of having friends, family, community members, and even acquaintances all come to the aid of the bereaved so they are not alone and are fed and cared for. Having space to grieve and be comforted is critical in healing on an individual and community level.

Unfortunately, being someone or knowing someone who has lost a loved one due to this ongoing conflict is almost a right of passage in this land. But this idea of grieving does not strictly apply to people grieving the loss of a loved one. We can grieve the loss of a home, a sense of community, of land, or an olive tree. There are stages of grief that require unique conditions to meet the needs of each stage. Grief is a universal human experience and feeling. It can be shared and recognized if there is space and time.

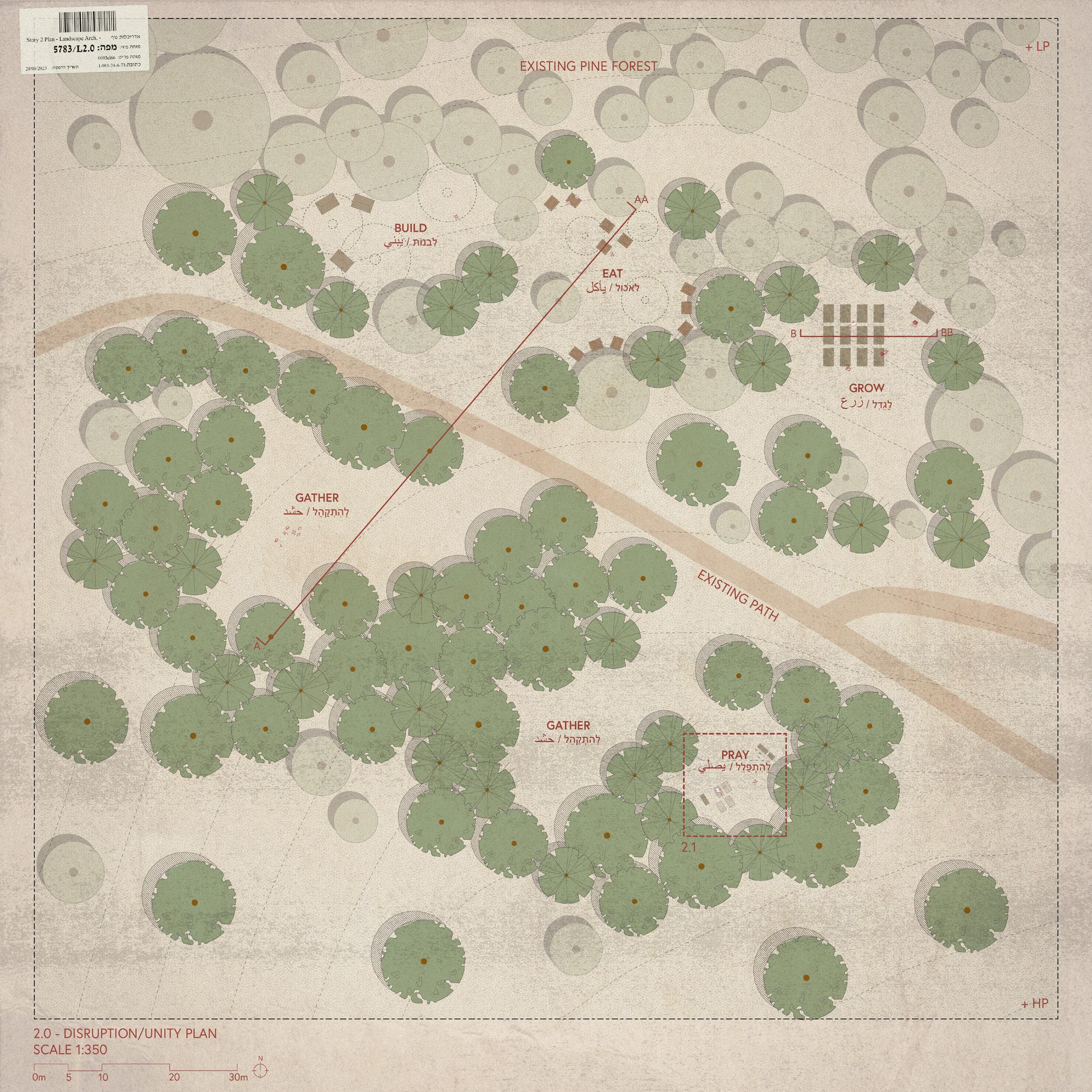

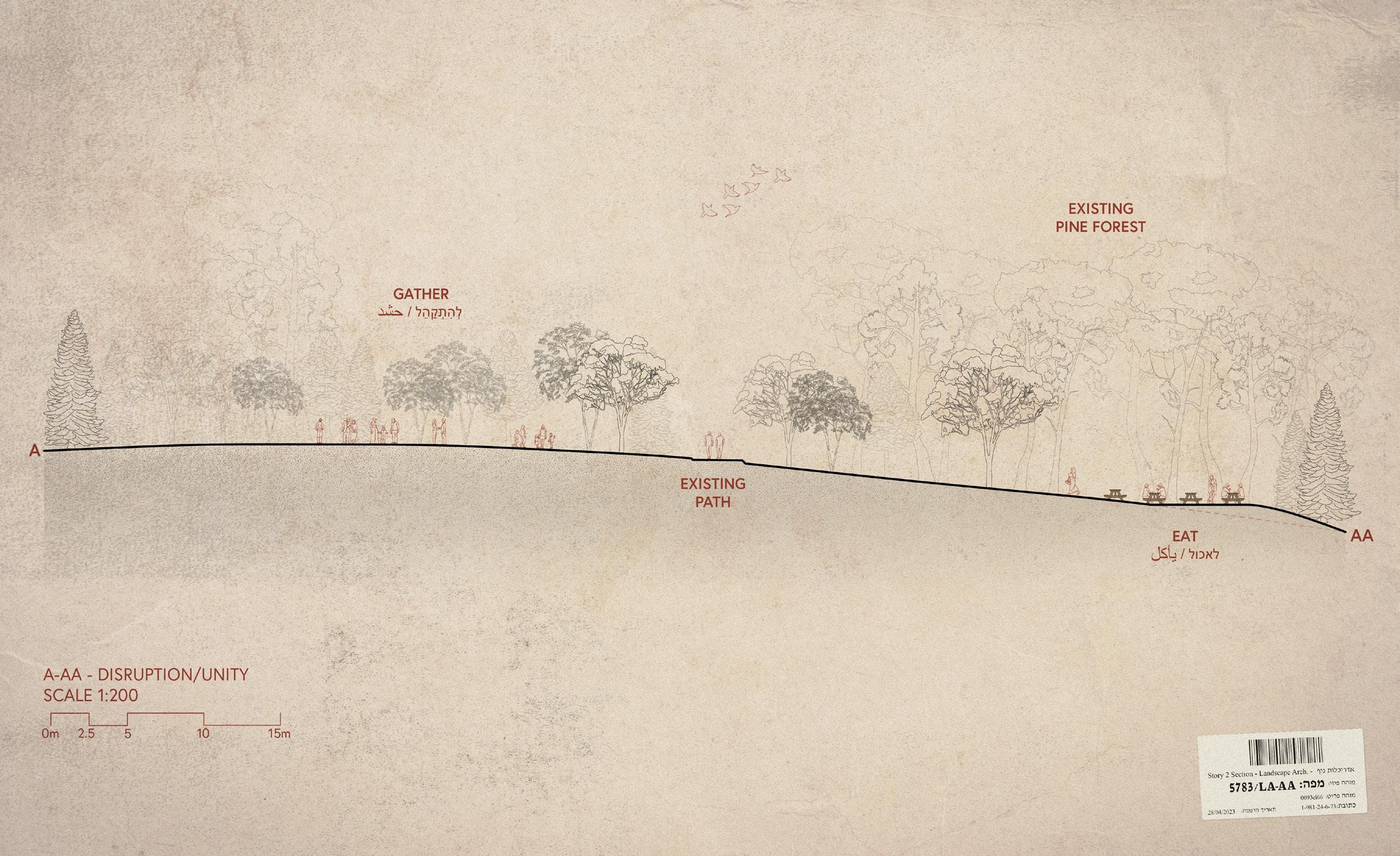

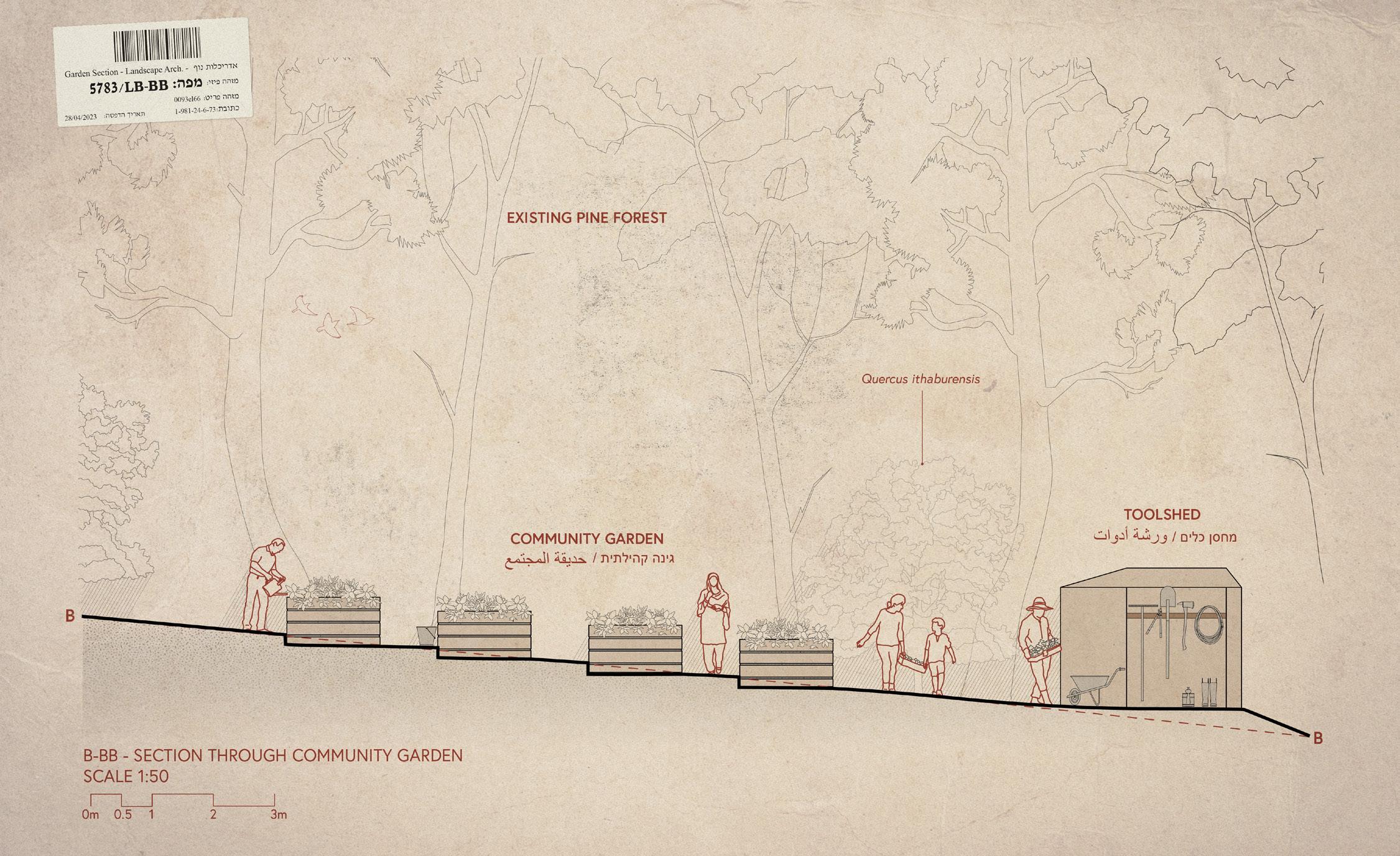

Disruption

Due to many of these pine forests being close to walls and therefore close to Palestinian towns shadowed by the wall, the exceptionally flammable nature of the tree’s resin, and their potent symbol of Jewish rootedness, they have become a frequent victim of arson attacks. Since the beginning of the First Intifada, over 900 fires have been started in JNF forests, most of which have been deliberately set by Palestinians.9 A Jerusalem-based newspaper even published a cartoon illustrating “tree burning certificates” being handed out by the Palestinian Authority, referring to the “tree planting certificates” offered by the JNF after donating into the blue tins.10 Underground Palestinian terror organizations often set out calls to commit terror and instructions on how to start forest fires.11 After a large forest fire incident in 2010, forest fires became recognized as deliberate and premeditated strategic terror tools.12 The site of this intervention is the HaHamisha forest located in ‘No-Man’s Land.’ Set ablaze in 2016, the fire started near Oasis of Peace/Neve Shalom/ Wahat al-Salam, a coexistence community near the intervention site and the recipient of several peace-related awards. Fires quickly spread across forests outside of Jerusalem, and fires were spontaneously started in other areas of the country. However, unity and community showed its face in this devastating form of disruption. Firefighting aircraft and aid arrived from Bulgaria, Cyprus, Croatia, France, Greece, Italy, Romania, Spain, Turkey, and even the Palestinian Authority.13

Unity

There is demonstrated need for gathering and coexistence space, with Oasis of Peace/Neve Shalom/Wahat al-Salam nearby and gatherings of activist groups around the country in the thousands. No-Man’s Land is a promising contender for facilitating this space, as expressed in the writing of political geographers, Noam Lesehm and Alasdair Pinkerton:

“Contrary to the absence assumed in its name, we demonstrate that no-man’s land is a highly active space: it is constantly produced and transformed by a multitude of actors, and in turn, is itself a transformative and generative space, opening new horizons of political action and social interaction.”14

-Noam Lesehm and Alasdair Pinkerton

Healing processes are most likely to occur when the individuals in conflict sit down in dialogue and are actively engaged in managing conflict15, rather than formal leaders or agencies making decisions around a boardroom table. Documentation and research examining the successes and failures of Israeli Palestinian dialogues have shown that more powerful sessions involved the practice of deep listening, best achieved in person. This means that one must suppress their sub-vocal objections and tendencies to be contrary to the person speaking to ensure they feel understood and heard.16 In recent years, testimonial stories of the horrors of war and its long-lasting personal consequences are a necessary therapeutic process and imperative to healing.17 In situations like these, participants often felt personally involved in the other’s narrative. As a result, they began feeling apologetic even though they were not the ones who directly inflicted the terror on the other. Most importantly, as examined in the literature review, space must be created to facilitate dialogue and peacebuilding in divided communities. This notion rings true in my own experiences within my Israeli/Palestinian dialogue group, رسج/Bridge/רׁשג. The first time we met in person, it was outdoors at a park. The big maple tree sheltered us, and the picnic tables hosted the traditional foods the members had brought to share. From that day on, after having that space to gather and meet in person, whether our meetings were online or not, we felt comfortable with each other and trusted each other with our tears and stories.

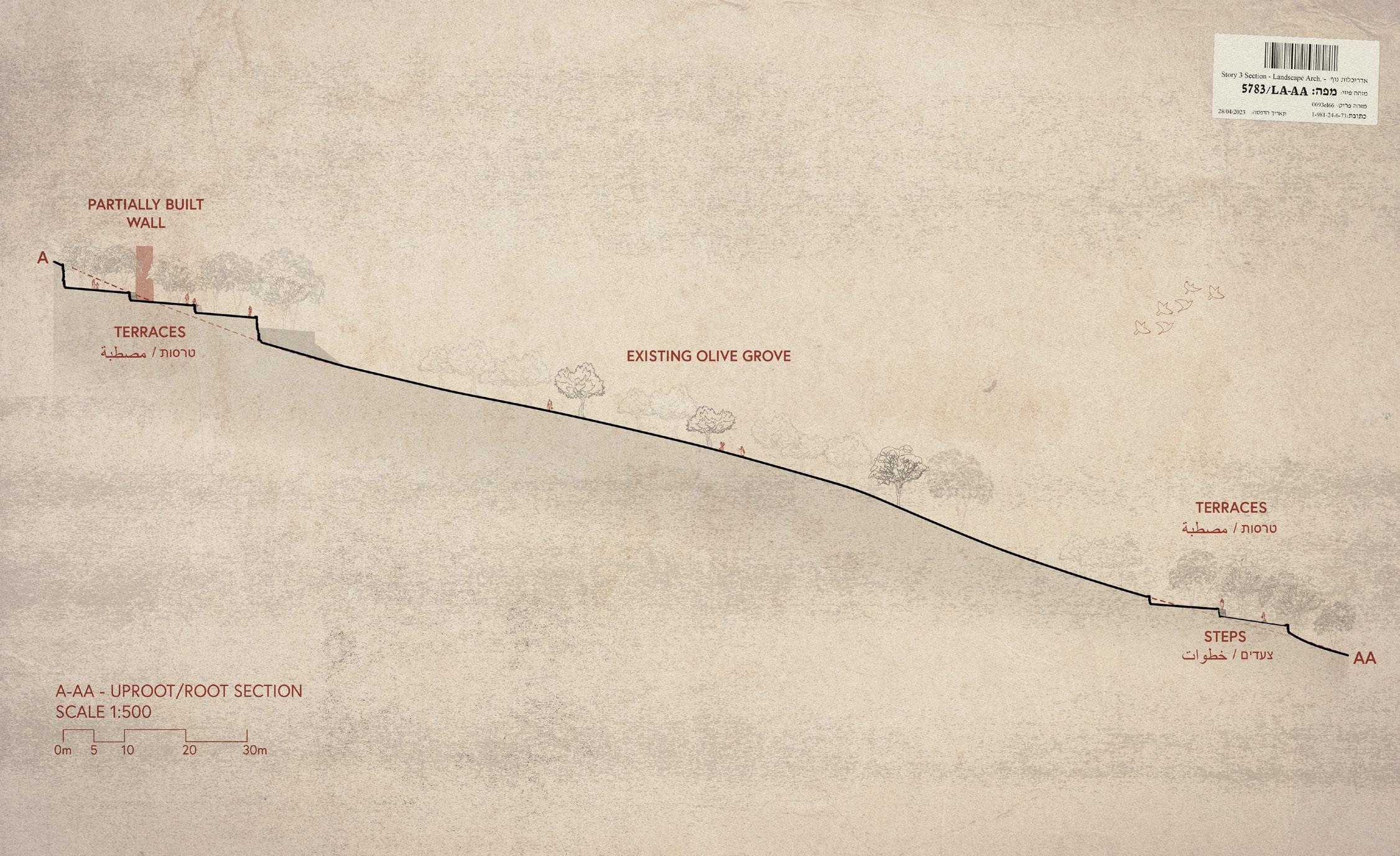

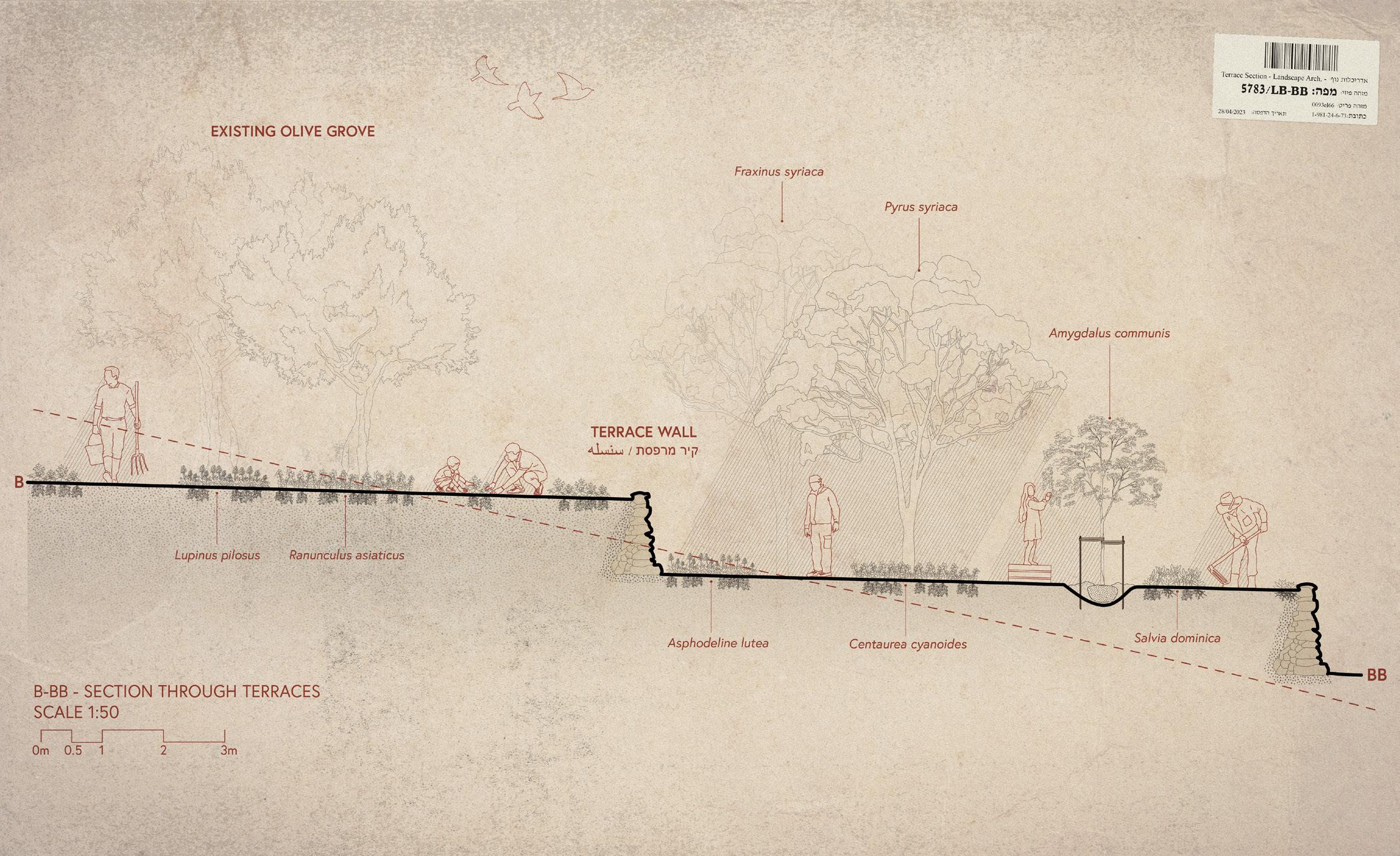

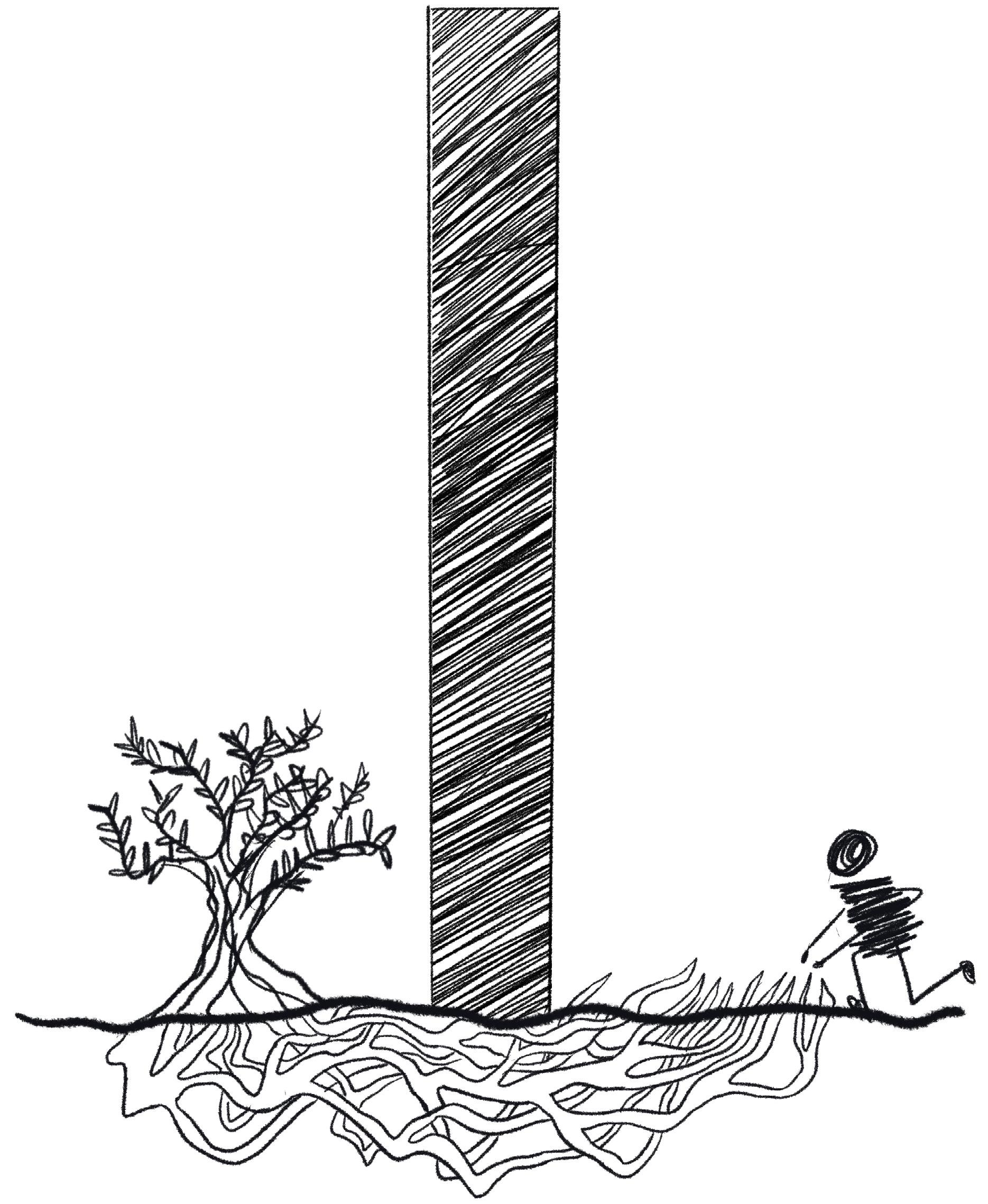

Uproot

The olive tree is not just a cultural symbol or a facet of Palestinian life and economy; it is also a political entity. It is slow-growing but long-living, drought resistant, and easy to grow in poor soil conditions, which is why it has transcended the eras of varying colonial forces and conquests in Israel/Palestine. It represents rootedness, history, and identity fixed in place. Increasingly in the last two decades, the State of Israel has been uprooting Palestinian-owned olive trees by the thousands. Olive trees have a history of being uprooted in this land since the Ottoman rulers uprooted them as punishment for tax avoidance, and the British Mandatory administration continued implementing these practices. However, Israel claims these uprooting practices are essential for national security.18 Olive trees are being uprooted to make way for the separation barrier, watchtowers and checkpoints, roads, and to increase visibility by removing hiding ground for terrorists.19 In a sense, the State of Israel has bestowed the olive with even more immense power because of its place in the conflict and through the indirect and direct acts of uprooting.20 In one documented dialogue group, the researcher found that many participants were stubborn to accept the causes of human rights violations as other members frequently attempted to justify them. In this dialogue session, participants were shown a photograph of an older woman holding onto the trunk of an uprooted olive tree. Scholar David Senesh describes this moment, writing:

“The interconnectedness of that woman, the land and the tree… This was a most pervasive visual demonstration of interconnectedness in an all-ornothing irreversible situation, where an uprooted tree symbolized death and despair… When Israelis can apologize for the uprooted tree, the Palestinians can invite them to sit in its shade and feel safe from threats of extermination.”21

-David Senesh

In 2015, in Beit Jala, right outside of Bethlehem, Israeli machinery began the construction of the wall, uprooting olive trees as it went. The proposed plan for the wall (while it remains unfinished) will make privately owned farmland in the Cremisan Valley inaccessible to Palestinian farmers in Beit Jala.

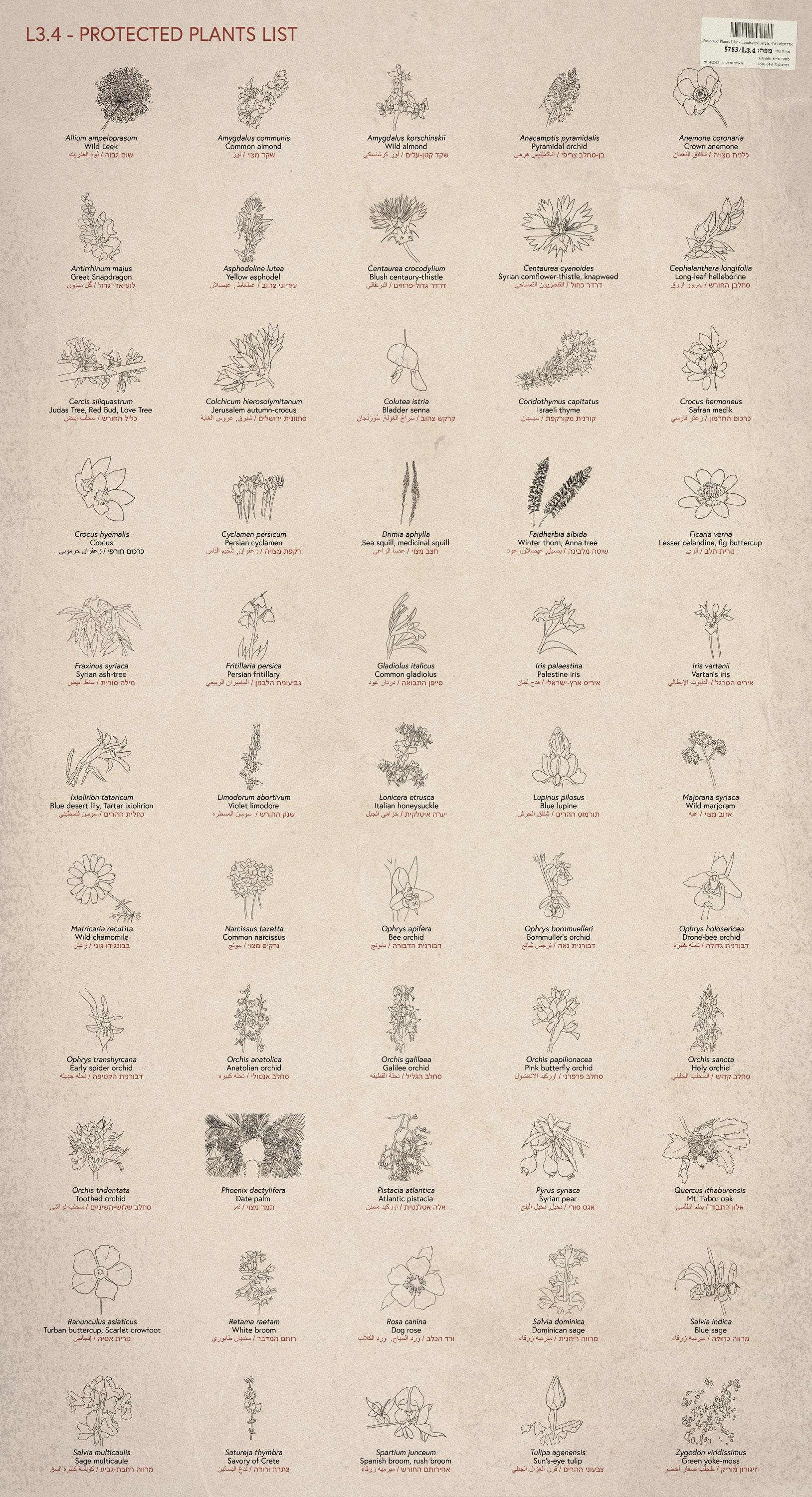

Root

It would be naive to propose planting olive trees or transplant uprooted olive trees and call it ‘rooting.’ Olive trees, and pine trees for that matter, are not protected under Israeli Law and thus subject to continuous uprooting. However, in 1964, Israel published the “Protected Natural Values” Law, which includes a list of protected species that has since been continually revised.22 By planting these rare and protected species in the land where the wall has not yet been constructed and by using traditional land practices to do so, this proposal hopes to reinforce rootedness in the landscape and protect Palestinian land sovereignty and livelihood. While this intervention is less so about increasing interrelations between Palestinians and Israelis, it’s important to recognize that the Palestinians are the ones who are occupied and oppressed today, and this effort focuses on their security and maintaining their livelihood.

Endnotes

1. Irus Braverman, Planted Flags: Trees, Land, and Law in Israel/Palestine, Cambridge University Press, 2014, 99.

2. Braverman, Planted Flags, 99.

3. “Zakariyya, Khirbat - Al-Ramla,” Palestine Remembered, Accessed April 30, 2023, https:// www.palestineremembered.com/al-Ramla/ Zakariyya,-Khirbat/index.html.

4. “Zakariyya, Khirbat,” Palestine Remembered.

5. Cindy A Sousa, Susan Kemp, and Mona ElZuhairi, “Dwelling within Political Violence: Palestinian women’s Narratives of Home, Mental Health, and Resilience,” Health & Place 30, (2014): 205.

6. Sousa, Kemp, and El-Zuhairi, “Dwelling within Political Violence,” 211.

7. TedX Talks, “Painful Hope | Ali Abu Awwad,” Youtube, 7 May 2015.

8. Colum McCann, Apeirogon: A Novel, First ed, New York: Random House, 2020, 223.

9. Braverman, Planted Flags, 105.

10. Braverman, 105.

11. Jonathan Fighel, “The “Forest Jihad”,” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 32, no. 9 (2009): 803-804..

12. János Besenyő, “Inferno Terror: Forest Fires as the New Form of Terrorism,” Terrorism and Political Violence 31, no. 6 (2019): 1234.

13. Besenyő, “Inferno Terror,” 1234.

14. Noam Leshem and Alasdair Pinkerton, “ReInhabiting no-Man’s Land: Genealogies, Political Life and Critical Agendas,” Transactions - Institute of British Geographers (1965) 41, no. 1 (2016): 42.

15. David Senesh, “Restorative Moments: From First Nations People in Canada to Conflicts in an Israeli–Palestinian Dialogue Group,” In Peacebuilding, Memory and Reconciliation, edited by Charbonneau, Bruno and Genevieve Parent,

Routledge, 2012, 167.

16. Senesh, 169.

17. Senesh, 169.

18. Braverman, 129-130.

19. Braverman, 130.

20. Irus Braverman, “Uprooting Identities: The Regulation of Olive Trees in the Occupied West Bank,” Political and Legal Anthropology Review 32, no. 2 (2009): 238.

21. Senesh, 172.

22. Avi Shmida, Ori Fragman, Ran Nathan, Zvi Shamir, and Yuval Sapir, “The Red Plants of Israel: A Proposal of Updated and Revised List of Plant Species Protected by the Law,” Ecologia Mediterranea 28, no. 1 (2002): 56.

Conclusion

Conclusion

The landscape is the basket that carries stories of love, trauma, displacement, and resilience. If we can uncover and listen to the tales the land and its inhabitants tell us, empathy moves to the forefront. The land reflects the political powers that put barriers on it, stopping the movement of people, flora, and fauna. But the land also speaks for itself, it continues to evolve in the face of an ever-changing climate, both politically and environmentally. The profound healing of the wounds of war and trauma will not come from political leaders.

This conflict is complex, deep rooted, and emotional. This project is my own. While I do my best to share the perspectives contrary to the narrative I grew up with, I cannot cover it all. Both Israelis and Palestinians deserve the right to express and receive love. Anyone who tells you that one must come at the expense of another, is not a human rights activist.

End Matter

Definitions

Click here to go back to where you left off!

Al-Nakba = ‘the Catastrophe’ = The Nakba was the max expulsion and exodus of over 750,000 Palestinians during the 1948 war that followed the declaration of Israel’s independence.

Annex = the forcible acquisition of territory or proclaiming sovereignty over a territory by another state, usually following war or conquest.

Antisemitism = prejudice toward, hostility to, or discrimination against Jewish people.

Balfour Declaration = the public statement issued in 1917 by the British government that announced their support for the establishment of a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine.

Bar Mitzvah/Bat Mitzvah = “son/daughter of the commandment” = the Jewish coming-of-age ritual in which Jewish children (at age 12 or 13) read from the Torah (Hebrew Bible) for the first time and become accountable to themselves and the laws of Judaism.

Checkpoint = barrier most often manned by the military that controls which travelers are permitted entrance or exit to a place.

Diaspora = the dispersion or spread of a group of people from their original homeland.

Dunam = the Ottoman unit of area equivalent to the acre, representing the amount of land that could be ploughed by a team of oxen in one day.

Eretz (Eretz Israel) = Eretz means land in Hebrew. Many Jews refer to this land as Eretz Israel. It is well-known among the Jewish community that if one says the ‘Eretz’ they are referring to Israel.

Green Line = the demarcation line set out in the 1949 Armistice Agreements made between Israeli commander, Moshe Dayan and his Jordanian counterpart, Abdullah a-Tal. They met to mark out a ceasefire line to end the war. They used thick crayons and drew on a dirty table, making any lines they drew quite bumpy and irregular. These lines became the de-facto borders of Israel until the 1967 SixDay War.

Judea and Samaria = some refer to this land as being called Judea and Samaria prior to it being called Palestine or Israel. The region of Judea and Samaria are biblical names tied to the ancient Israelite kingdoms.

Kibbutz = a community in Israel traditionally based on agriculture, where folks live in accordance with a specific social contract based on mutual aid and democracy.

Intifada = “shaking off” = An intifada is a civil uprising and resistance movement involving both violent and nonviolent Palestinian demonstrations. There have been two large intifadas in Israel/ Palestine: the First Intifada was from 1987 – 1993, and the Second Intifada was from 2000 - 2005.

Islamophobia = prejudice toward, hostility to, or discrimination against Muslim people.

Israeli Settlements = refers to any of the communities built by Israeli Jews after the Six-Day War (in 1967) located primarily in the West Bank, but also in the Gaza Strip, the Golan Heights, and the Sinai Peninsula. These settlements are in violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention, which prohibits a country from transferring its population into occupied territory. Israel maintains that the settlements are not illegal because the West Bank was ‘not a country’ when they annexed it.

Mitzvah = literally translates to ‘commandment’ in Hebrew, but generally used to mean a ‘good deed.’

No-Man’s Land = No-Man’s Land is a sliver of land where the Israeli and Jordanian commander’s crayons didn’t overlap when drawing the armistice line of 1949 (The Green Line). The area between the two Green Lines drawn became called No-Man’s Land.

Oslo Accords = a Declaration of Principles signed by Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Palestine Liberation Organization leader Mahmoud Abbas. The agreements included that the PLO would renounce terrorism and recognize Israel’s right to exist, that Israel would recognize the PLO as the representative body of the Palestinians, and that a Palestinian Authority would be established to govern the West Bank and Gaza for the next five years. Topics of borders, refugees and Jerusalem were unresolved. United States president Bill Clinton played a role in bringing these accords to the table and the leaders shook hands on national television on the White House lawn. Two years later, Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated by a right-wing extremist Israeli who opposed Rabin’s efforts making peace with Palestinians.

Qur’an = the central religious text of Islam. Muslim people believe the text is a transcription of God’s speech revealed by an angel to the Prophet Muhammad.

Saba = Hebrew for Grandfather.

Safta = Hebrew for Grandmother.

Separation Barrier = the wall built by Israel (somewhat following the Green Line) that divides Israel and the West Bank. Israelis describe the wall as being a security measure and Palestinians describe the wall as being an element of apartheid and segregation.

Shoah = Hebrew for “catastrophe” and is synonymous with the word Holocaust.

Torah = the central religious text of Judaism. Jewish people believe that the Torah was revealed to Moses by God on Mount Sinai.

Zionist Movement/Zionism = Jewish national movement that saw the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine/supports the self-determination of Jews in their ancestral homeland. Zionism is a nationalist movement created in reaction to increasing antisemitism in Europe. Anti-Zionists see the movement as colonial, racist, and exceptionalist.

Week 1

Collection

Collect stories of personal experiences in Israel/ Palestine from books, journals, and archives.

Week 2

Wall Analysis

Spatial data collection, mapping, understanding spatial and political context of the wall.

Week 9 Weeks 10 - 11

Silent Review

Create the first draft of drawing set with a semi-finalized design scheme.

Details

Work on materiality, planting plan, and focus on ephemeral and sensorial qualities of all proposed designed spaces.

Weeks 3 - 5

Schematic Design

Testing peacebuilding strategies, translating peacebuilding into uses of planting, schematically organizing potential design elements.

Week 12

Substantial Review

Create an 80% complete set of drawings that convey the narrative, intention, and scheme of the design.

Week 6

Midterm Review

Continue testing spatial program and create first set of drawings that should reflect a culturally specific style and method.

Weeks 13 - 14

Revisions

Finesse designed elements and revise drawings based on feedback from substantial review.

Week 7

Check Self

After receiving review feedback, reexamine work thus far and check for any possible culturally insensitive decisions and reconsider best approaches.

Week 8

Formal Design Stage

Move into critical design thinking using drawing as a thinking tool to flush out program elements.

Week 15

Final Graduate Project Review!

Present a full set of completed drawings.

Akawi, Nora. “Traversing Territories” Aga Khan Program Lecture. Lecture at Harvard GSD, Cambridge, MA, October 1, 2018.

Amiry, Suad. “Reclaiming Space: Riwaq’s 50 Village Project in Rural Palestine” Aga Khan Program Lecture. Lecture at Harvard GSD, Cambridge, MA, March 20, 2018.

Anderson, Ingrid. “Surviving the Story: The Narrative Trap in Israel and Palestine by Rosemary Hollis (Review).” The Middle East Journal 74, no. 2 (2020): 322-324.

Armiach, Igor, Iris Bernstein, Yaya Tang, Tamar Dayan, and Efrat Gavish-Regev. “Activity-density data reveal community structure of Lycosidae at a Mediterranean shrubland.” Arachnology Letters 52 (2016), 16-24.

Bakshi, Anita. Topographies of Memories: A New Poetics of Commemoration. Secaucus; New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Barghouti, Mourid. I Saw Ramallah. Translated by Ahdaf Soueif. 1st Anchor Books ed. New York: Anchor Books, 2003.

Barromi-Perlman, Edna. “Visions of Landscape Photography in Palestine and Israel.” Landscape Research 45, no. 5 (2020): 564-582.

Bartov, Omer. Israel-Palestine: Lands and Peoples. New York: Berghahn, 2021.

Ben Hagai, Ella, Phillip L. Hammack, Andrew Pilecki, and Carissa Aresta. “Shifting Away from a Monolithic Narrative on Conflict: Israelis, Palestinians, and Americans in Conversation.” Peace and Conflict 19, no. 3 (2013): 295-310.

Besenyő, János. “Inferno Terror: Forest Fires as the New Form of Terrorism.” Terrorism and Political Violence 31, no. 6 (2019): 1229-1241.

Björkdahl, Annika. “Urban Peacebuilding.” Peacebuilding 1, no. 2 (2013): 207-221.

Björkdahl, Annika and Stefanie Kappler. Peacebuilding and Spatial Transformation: Peace, Space and Place. 1st ed. London: Routledge, 2017. doi:10.4324/9781315684529.

Björkdahl, Annika, and Susanne Buckley-Zistel. Spatializing Peace and Conflict: Mapping the Production of Places, Sites and Scales of Violence. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

Bollens, Scott. Urban Peacebuilding in Divided Societies: Belfast and Johannesburg. Milton: Taylor & Francis Group, 2021.

Bracka, Jeremie and Springer Law and Criminology eBooks 2021 English/International. Transitional Justice for Israel/Palestine. 1st ed. Springer International Publishing, 2021.

Brand-Jacobsen, Kai Frithjof. “Palestine and Israel: Improving Civil Society Peacebuilding Strategies, Design and Impact.” Center for Social Innovation, Department of Peace Operations (2009).

Braverman, Irus. Planted Flags: Trees, Land, and Law in Israel/Palestine. Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Braverman, Irus. “Planting the Promised Landscape: Zionism, Nature, and Resistance in Israel/Palestine.” Natural Resources Journal 49, no. 2 (2009): 317-365.

Braverman, Irus. “”The Tree is the Enemy Soldier”: A Sociolegal Making of War Landscapes in the Occupied West Bank.” Law & Society Review 42, no. 3 (2008): 449-482.

Braverman, Irus. “Uprooting Identities: The Regulation of Olive Trees in the Occupied West Bank.” Political and Legal Anthropology Review 32, no. 2 (2009): 237-264.

Brummer, David. “Kfar Saba Ranks 1st for Quality of Life in National Survey; Jerusalem Last.” The Times of Israel, January 10, 2022. https://www.timesofisrael.com/kfar-saba-ranks-1st-for-quality-of-life-in-nationalsurvey-jerusalem-comes-in-last/.

Byrne, Fionn. “Verdant Persuasion: The use of Landscape as a Warfighting Tool during Operation Enduring Freedom.” Journal of Architectural Education 76, no. 1 (2022): 37-48.

Calame, Jon and Esther Charlesworth. “Cities and Physical Segregation.” In Divided Cities, 19-36. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, Inc, 2011.

Chaitin, Julia. “Co-creating peace: Confronting psychosocial-economic injustices in the Israeli-Palestinian context,” In Peacebuilding, Memory and Reconciliation, edited by Charbonneau, Bruno and Genevieve Parent, Routledge, 2012: 146-162.

Chaitin, Julia and Shoshana Steinberg. “”You should Know Better”: Expressions of Empathy and Disregard among Victims of Massive Social Trauma.” Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 17, no. 2 (2008): 197-226.

Dávila, Patricio and Onomatopee (Gallery). Diagrams of Power: Visualizing, Mapping, and Performing Resistance. Vol. 168; Eindhoven: Onomatopee, 2019.

Davis, Tristan. “Welcome to the Walled Off: A Visit to Banksy’s Hotel in Bethlehem.” The Jerusalem Post, March 17, 2018. https://www.jpost.com/jerusalem-report/welcome-to-the-walled-off-a-visit-to-banksyshotel-in-bethlehem-544463.

Dulong, Nicole, Samantha Miller, and Reece Milton. Hogan’s Alley Site Guidelines. Vancouver: University of British Columbia, 2021.

“Facilities.” The Walled Off Hotel. Accessed November 10, 2022. https://walledoffhotel.com/facilities.html.

Fields, Gary. “Landscaping Palestine: Reflections of Enclosure in a Historical Mirror.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 42, no. 1 (2010): 63-82.

Fighel, Jonathan. “The “Forest Jihad”.” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 32, no. 9 (2009): 802-810.

Fisher, Ian. “Banksy Hotel in the West Bank: Small, but Plenty of Wall Space.” The New York Times. April 16, 2017. /www.nytimes.com/2017/04/16/world/middleeast/banksy-hotel-bethlehem-west-bank-wall.html.

Friedman, Thomas L. The Lexus and the Olive Tree. 1st ed. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1999.

Furse-Roberts, James. “Narrative Landscapes.” In Museum Making: Narratives, Architectures, Exhibitions, 2012, 179191.

Gaffikin, Frank, Malachy Mceldowney, and Ken Sterrett. “Creating Shared Public Space in the Contested City: The Role of Urban Design.” Journal of Urban Design 15, no. 4 (2010): 493-513.

Goodman, Anna. “Karl Linn and the Foundations of Community Design: From Progressive Models to the War on Poverty.” Journal of Urban History 46, no. 4 (2020): 794-815.

Gorney, Edna. “Roots of Identity, Canopy of Collision: Re-Visioning Trees as an Evolving National Symbol within the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict.” In Environmental History in the Making, 327-344. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2016.

Gorzalzcany, Amir. “The Kefar Saba Cemetery and Differences in Orientation of Late Islamic Burials from Israel/Palestine.” Levant (London) 39, no. 1 (2007): 71-79.

Gottesman, Rachel, Tamar Novick, Iddo Ginat, Dan Hasson, and Yonatan Cohen. Land, Milk, Honey: Animal Stories in Imagined Landscapes. Tel Aviv; Zurich, Switzerland; Park Books, 2021.

Gur-Ze’ev, Ilan and Ilan Pappe. “Beyond the Destruction of the Other’s Collective Memory: Blueprints for a Palestinian/Israeli Dialogue.” Theory, Culture & Society 20, no. 1 (2003): 93-108.

Hallward, Maia Carter. “Building Space for Peace: Challenging the Boundaries of Israel/Palestine.” ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2006.

Hassouna, Silvia. “An Assessment of Dialogue-Based Initiatives in Light of the Anti-Normalization Criticisms and Mobility Restrictions.” Palestine-Israel Journal of Politics, Economics, and Culture 21, no. 2 (2015): 51-59.

Hassouna, Silvia. “Spaces for Dialogue in a Segregated Landscape: A Study on the Current Joint Efforts for Peace in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict.” Conflict Resolution Quarterly, vol. 34, no. 1, 2016, pp. 57-82.

Helphand, Kenneth I. Defiant Gardens: Making Gardens in Wartime. San Antonio, Tex: Trinity University Press, 2006.

Hirsch, Alison Bick. “From “Open Space” to “Public Space”: Activist Landscape Architects of the1960s.” Landscape Journal 33, no. 2 (2015): 173-194.

“Historical Timeline: 1900-Present.” Britannica | ProCon, June 14, 2021. https://israelipalestinian.procon.org/ historical-timeline-1900-present/.

Ide, Tobias. “Space, Discourse and Environmental Peacebuilding.” Third World Quarterly 38, no. 3 (2017): 544-562.

Influs, Moran, Maayan Pratt, Shafiq Masalha, Orna Zagoory-Sharon, and Ruth Feldman. “A Social Neuroscience Approach to Conflict Resolution: Dialogue Intervention to Israeli and Palestinian Youth Impacts Oxytocin and Empathy.” Social Neuroscience 14, no. 4 (2019): 378-389.

Isaac, Jad and Jane Hilal. “Palestinian Landscape and the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict.” International Journal of Environmental Studies 68, no. 4 (2011): 413-429.

Jacobs, Michele. “Contested Monuments in a Changing Heritage Landscape: //hapo Museum, Freedom Park, Pretoria.” De Arte 51, no. 1 (2016): 89-100.

Kadman, Noga. “Roots Tourism–Whose Roots?: The Marginalization of Palestinian Heritage Sites in Official Israeli Tourism Sites.” Téoros 29, no. 1 (2010): 55-66.

Kadman, Noga and Oren Yiftachel. “Depopulation, Demolition, and Repopulation of the Village Sites.” In Erased from Space and Consciousness, 8. United States: Indiana University Press, 2015.

Khader, Jamil. “Architectural Parallax, Neoliberal Politics and the Universality of the Palestinian Struggle: Banksy’s Walled Off Hotel.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 23, no. 3 (2020): 474-494.

Klein Halevi, Yossi. Letters to My Palestinian Neighbor. Harper Perennial, 2019.

Korostelina, Karina V. “Can history heal trauma? The role of history education in reconciliation processes.” In Peacebuilding, Memory and Reconciliation, edited by Charbonneau, Bruno and Genevieve Parent, Routledge, 2012, 195-214.

Lennon, John. “Erasing People and Land.” In Conflict Graffiti: University of Chicago Press, 2022.

Leshem, Noam and Alasdair Pinkerton. “Re-Inhabiting no-Man’s Land: Genealogies, Political Life and Critical Agendas.” Transactions - Institute of British Geographers (1965) 41, no. 1 (2016): 41-53.

Linn, Karl. Building Commons and Community. Oakland, CA: New Village Press, 2007.

Liphschitz, Nili, Ram Gophna, Moshe Hartman, and Gideon Biger. “The Beginning of Olive (Olea Europaea) Cultivation in the Old World: A Reassessment.” Journal of Archaeological Science 18, no. 4 (1991): 441-453.

Macleod, Suzanne, Laura Hourston Hanks, and Jonathan Hale. Museum Making: Narratives, Architectures, Exhibitions, edited by Macleod, Suzanne, Laura Hourston Hanks and Jonathan Hale. 1st ed. Abingdon, Oxon [England]; New York, NY; Routledge, 2012. doi:10.4324/9780203124574

Marschall, Sabine. “Chapter 7. Freedom Park As National Site Of Identification”. In Landscape of Memory. Vol. 15. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2010, doi:10.1163/ej.9789004178564.i-410.

Makdisi, Saree. Palestine Inside Out: An Everyday Occupation. 1st ed. New York: W. W. Norton & Co, 2008.

McCann, Colum. Apeirogon: A Novel. First ed. New York: Random House, 2020.

Milani, Tommaso M. “Banksy’s Walled Off Hotel and the Mediatization of Street Art.” Social Semiotics, no. aheadof-print (2022): 1-18.

Mohammad, Omar. “Contemporary Memorial Landscape: How to Convey Meaning through Design: A Study Based on Cases from London and Palestine.” ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2017.

Mostafavi, Mohsen and Harvard University. Graduate School of Design. Ethics of the Urban: The City and the Spaces of the Political. Zürich; Cambridge, MA: Lars Müller Publisher, 2017.

Olin, Laurie. “Form, Meaning, and Expression in Landscape Architecture.” Landscape Journal 7, no. 2 (1988): 149168.

“OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights.” Hate Crime Reporting, April 12, 2022. https:// hatecrime.osce.org/canada?year=2020.

Ottman, Esta Tina. “Deconstructing ‘Collective Trauma’ and the Israel-Palestine Conflict: To what Extent is the Concept of ‘Collective Trauma’ Necessary to Peacebuilding in the Israeli-Palestine Conflict?” Annals of Japan Association for Middle East Studies 31, no. 2 (2016): 1-28.

“Palestinian Olive Agony - (A Statistical Report on Israeli Violations).” Monitoring Israeli Violations Department - Land Research Center - Arab Studies Society- Jerusalem, February 2017. https://www.lrcj. org/pdf/web/viewer.html?file=441737924-LRC-1511790968.pdf.

Pearson, Chris. “Researching Militarized Landscapes: A Literature Review on War and the Militarization of the Environment.” Landscape Research 37, no. 1 (2012): 115-133.

Peteet, Julie Marie. Space and Mobility in Palestine. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2017.

Pirker, Peter, Philipp Rode, and Mathias Lichtenwagner. “From Palimpsest to Me-Moiré: Exploring Urban Memorial Landscapes of Political Violence.” Political Geography 74, (2019): 102057.

Potteiger, Matthew and Jamie Purinton. Landscape Narratives: Design Practices for Telling Stories. New York: J. Wiley, 1998.

Pritz, Elie. “Making Room.” Peace Heroes, 1 Nov. 2019, globalpeaceheroes.org/2019/11/making-room/.

Roberts, Jo. Contested Land, Contested Memory: Israel’s Jews and Arabs and the Ghosts of Catastrophe. Dundurn, 2013.

Rubner, Michael. “The Two-State Delusion: Israel and Palestine - A Tale of Two Narratives.” Middle East Policy 23, no. 1 (2016): 163-167.

Salomon, Gavriel. “A Narrative-Based View of Coexistence Education.” Journal of Social Issues 60, no. 2 (2004): 273-287.

Sarafa, Rami. “Roots of Conflict: Felling Palestine’s Olive Trees.” Harvard International Review 26, no. 1 (2004): 13.

Senesh, David. “Restorative Moments: From First Nations People in Canada to Conflicts in an Israeli–Palestinian Dialogue Group.” In Peacebuilding, Memory and Reconciliation, edited by Charbonneau, Bruno and Genevieve Parent, Routledge, 2012.

Schaffer, Gad. “The Driving Forces Inducing Land Cover Changes in Israel’s Northern Sharon Plain from the End of the Nineteenth Century to the Present Time.” Historical Geography 48, no. 1 (2020): 102-132.

Schama, Simon. Landscape and Memory. Toronto: Random House of Canada, 1995.

Schirch, Lisa. “Trauma Triggers and Narratives on Israel and Palestine.” Journal of Peacebuilding & Development 13, no. 3 (2018): 108-114.

Schoonderbeek, Marc and Malkit Shoshan. “Conflict, Space and Architecture.” Footprint: Delft School of Design Journal 10, no. 2 (2017)

Schulze, Kirsten E. “Camp David and the Al-Aqsa Intifada: An Assessment of the State of the Israeli-Palestinian Peace Process, July-December 2000.” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 24, no. 3 (2000): 215-233.

Shmida A., O. Fragman, R. Nathan, S. Shamir, and Y. Sapir. “The Red Plants of Israel: A Proposal of Updated and Revised List of Plant Species Protected by the Law.” Ecologia Mediterranea 28, no. 1 (2002): 55-64.

Shoshan, Malkit. “Border Ecologies” GSD Talks. Lecture at Harvard GSD, Cambridge, MA, November 7, 2017.

Shadar, Hadas and Eli Maslovski. “Pre-War Design, Post-War Sovereignty: Four Plans for One City in Israel/ Palestine.” Journal of Architecture (London, England) 26, no. 4 (2021): 516-540.

Shavit, Ari. My Promised Land: The Triumph and Tragedy of Israel. Spiegel & Grau, 2018.

Sharif, Yara. Architecture of Resistance: Cultivating Moments of Possibility within the Palestinian/Israeli Conflict. 1st ed. Vol. 1. London: Routledge, 2017. doi:10.4324/9781315524290.

Sharif, Yara. “The Not So Ordinary: Capturing Possibilities Through The Gaps” Aga Khan Program Lecture. Lecture at Harvard GSD, Cambridge, MA, November 19, 2018.

Sheffi, Na’ama and Anat First. “Land of Milk and Honey: Israeli Landscapes and Flora on Banknotes.” National Identities 21, no. 2 (2019): 191-211.

Silva, Corinne. Garden State: The Politics of Planting in Israel/Palestine. Cardiff: Ffotogallery Wales Limited and The Mosaic Rooms, A.M. Qattan Foundation, 2016.

Sorkin, Michael. Against the Wall: Israel›s Barrier to Peace. New York: New Press, 2005.

Sousa, Cindy A., Susan Kemp, and Mona El-Zuhairi. “Dwelling within Political Violence: Palestinian women’s Narratives of Home, Mental Health, and Resilience.” Health & Place 30, (2014): 205-214.

Stevens, Quentin, and Karen A. Franck. Memorials as Spaces of Engagement: Design, use and Meaning. New York: Routledge, 2016.

“The Freedom Park //Hapo (Museum).” GREENinc Landscape Architecture + Urbanism. Accessed November 2, 2022. https://www.greeninc.co.za/the-freedom-park-museum.

“The Freedom Park.” Landezine, September 4, 2012. https://landezine.com/the-freedom-park-by-greeninc/.

TedX Talks. “Painful Hope | Ali Abu Awwad.” Youtube, 7 May 2015. https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=BzDEFAGv_hc

“Truth Commission: South Africa.” United States Institute of Peace, December 1, 1995. https://www.usip.org/ publications/1995/12/truth-commission-south-africa.