25 minute read

The Freedom Park

Location: Pretoria, South Africa

Landscape Architect: GREENinc Landscape Architecture Year: 2007

Advertisement

Institutionalized racism and racial segregation had existed in South Africa under colonial rule (although less formally) and under the apartheid system established by the National Party. Apartheid created incomprehensible brutality in every aspect of life for Black South Africans, from healthcare to civil and political rights. After the fall of apartheid in South Africa, the Government of National Unity assembled the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) to investigate human rights violations and serve restorative justice. The TRC report included recommendations for necessary reparations, including financial, community, and symbolic reparations.1 One of the outcomes of the TRC Report, as mandated by President Nelson Mandela, was The Freedom Park. A park project offered a form of symbolic reparation to begin the process of cleansing and healing at a national level. The park design process began with adopting the notion of ubuntu, the African philosophical tradition stressing the existence of common humanity and the need for forgiveness as a precondition to reconciliation.2

Freedom Park intends to address the collective trauma of colonialism and apartheid. The design includes the use of metaphorical exemplification, symbolism, and draws on Indigenous knowledge systems to inform the designed components.3 Firstly, the park’s construction demolished colonial ruins of Fort Tullichewan, dating back to the late 1800s and the first Anglo-Boer War (between the British and the self-governing Afrikaner). This initial act intended to sever the link between memory and place to create and enforce a new symbolism.4 The park is situated on a quartz ridge, rich in biodiversity, obliging the designers to undertake a level of sensitive planning to conserve as much of its natural state as possible. Those plants that were removed were transferred to a nursery until they could be returned to the landscape.5 Nestled into the slopes of the landscape, the park and connected museum are to reveal themselves more subtly than the surrounding monuments do.

Many of the symbols and metaphors derive from nature’s core elements of earth, water, fire, and air. Each design component is named in a different official language, seeking to unite different cultural groups by giving them each equal stake and recognition in the park.6 For example, an Nguni word, Isivivane, was used to name the space of ceremonial trees and boulders, symbolizing the resting place of those who died in the struggle for freedom. Each boulder underwent ritual healing and cleansing before being brought to its final resting site.7 The siSwati word, S’kumbuto, is the name given to the memorial wall commemorating those who died in major South African conflicts and a Sanctuary for quiet contemplation and reflection near the lake.8 The winding path, with stops to rest and reflect leading to and from the museum, is named after the Tshivenda word for success or progress, Mveledzo. 9

The materiality assists the narrative and delivers symbolic meaning throughout the entire park. Water is one key element carried in many forms throughout different park spaces. The symbolism of water is consistent across tribes and plays a role in healing and traditional cleansing rituals. The use of red clay brick intended to create a symbolic material connection with the boulders, reflect the red soils of the hill and set the stage to emphasize vertical elements of steel and timber.10 Some of these vertical elements derive from the African philosophy of creation and symbolize the progress in the struggle for freedom. Or, in the case of the line of reeds, the vertical element represents communication between heaven and earth as reeds are used to communicate to higher powers through ancestors in Swazi and Zulu cultures.11

Evaluation

The politics of memory and memorialization often do not accurately acknowledge cultural discourses and are influenced by Western methods of commemoration. In this case, the project aimed to tell a new story- correct narratives about pre-apartheid Africa and reclaim that Africa’s significance is pre-colonial. There is no shortage of successful integration of tradition, Indigenous knowledge, and cultural symbolism. While the argument can be made that not all visitors will understand or appreciate these metaphors or symbols, I argue that is precisely the point, that it is not for them. Instead, this project aims to heal, reconcile, and address the psychological damage of colonialism and apartheid by incorporating meaningful symbols to oppressed groups. Of course, one of the museum’s main goals is to increase tourism; however, it goes further than that. Those who wish to learn may learn from the signage and descriptions, but this project represents a progression forward in history for local communities. The extensive consultation process with youth, women, traditional healers, labour groups, veterans, nationwide surveys, and more12 maintains that the overall concept evolved in democratic and transparent means into a symbol of national identity. Some criticism suggests that still, some of the design components are eurocentric, such as The Wall of Names or the Eternal Flame, and that some (mostly white conservatives, but some not) did not identify with the themes of the park and felt some perspectives on history were left out or skewed.13 Strategies of commemoration will always be controversial and not without challenges, especially ones that deal with a national identity. Perhaps there is not enough left to interpretation, or is there too much? It must be accepted among the design community that monumental spaces will be interpreted and re-interpreted in conjunction with culture and memory.

Takeaways

This project employed strategies worth considering moving forward into this graduate project’s conceptual and design phase. Symbolic representation is difficult to achieve and even more so in a divided community for whom symbols might have different connotations or whose collective narratives are competing. However, shared symbols and widely accepted feelings of trauma, loss, and the struggle for liberation may increase empathy and acceptance. However, one of the key takeaways is the recognition and welcoming of flux in interpreting symbols. This project did not explicitly acknowledge that the park’s embedded meaning may change over time, but this notion should be worked into the design intervention. The naming of different programmatic elements in the park with different official languages was a clever way to make each group see themselves in the park. Additionally, the extensive consultation process and integration of traditions and traditional ways of knowing makes new connections between people and place. While a consultation with the public is not within the scope of this graduate project, understanding tradition and connecting the commonalities between two peoples’ traditional ways of being will be critical to shaping long-lasting memories to place.

The Walled Off Hotel

Location: Bethlehem, Palestine

Designer: Banksy

Year: 2017

“The Walled Off, an art hotel set within slingshot distance of Checkpoint 300, was opened by the graffiti artist Banksy in 2017. It stands within yards of the high concrete barriers. Even the most expensive rooms only get a few minutes of direct winter sunlight each day: the shadow of the Wall is cast down into the rooms and can be tracked as it crosses the carpet. The maids can tell the time of day by how much of the carpet is shadowed.”14

– Colum McCann

World-renowned British street artist under the pseudonym Banksy opened the Walled Off Hotel for tourists, Israelis, Palestinians, and vandals alike. This project is rather controversial, located just five meters from the separation barrier in the Palestinian town of Bethlehem. Banksy is known for his politically charged street artworks, some of which are painted on the Separation Barrier in numerous locations. The hotel boasts of offering the “worst view in the world”15, that of the contested wall, which to some is a security measure and to others a symbol of oppression and dispossession. The hotel is called an ‘art hotel’ as it contains a museum and displays an extensive collection of street art and ironic or symbolic materials. Banksy created the museum precisely 100 years after the British took control and occupied Palestine, saying, “I don’t know why, but it felt like a good time to reflect on what happens when the United Kingdom makes a huge political decision without fully comprehending the consequences.”16

The hotel comprises several hotel rooms for overnight stays, a bookshop, a gallery featuring works created by exclusively local artists, a piano bar decorated like an English gentleman’s club, referencing Britain’s colonial rule, and a museum ‘dedicated solely to the biography of the wall.’17 One of the most under-acknowledged facets of the conflict today is the influence of the British in the region, both past and present. Banksy’s choice to decorate the piano bar in the way he did reveals the underpinning of the conflict’s geopolitical roots. Hotel staff serve tea and scones as visitors sit on leather couches beside a wall covered with security cameras affixed to wooden plaques as if they were dead animal heads in a hunting lodge. Being directly adjacent to the separation barrier, guests may sit and enjoy the ugly stain on the landscape in all its stateliness with a beverage in hand. Something is intriguing about the dichotomy of the site and the informality of this program. The wall in Bethlehem and around the hotel is covered in graffiti, the associated store next-door, ‘WallMart,’ even offers stencils and spray paint. The hotel then becomes an engagement with the wall. Allowing and encouraging street art as an active form of resistance is precisely Banksy’s vision with this project and in his works both locally in this land and internationally.

As previously mentioned, this project is controversial. For the local community who are unironically facing the realities of the conflict, some feel that the hotel and Banksy’s works trivialize the conflict18 and hide in the safe confines of humour. It remains unclear how Banksy developed his collection of culturally specific artwork and whether or not he consulted with folks with true life experiences of oppression. For example, one of the rooms boasts a large mural of an Israeli soldier and a Palestinian freedom fighter having a pillow fight. Some Palestinian locals feel that the hotel fetishizes and normalizes occupation,19 feeding the anti-normalization drive mentioned in the literature review section. Others appreciate that the hotel brings international awareness of the conflict and that its profits go directly to the city of Bethlehem.20 The Walled Off Hotel has positively influenced the economy of Bethlehem as numerous new shops and restaurants have taken over abandoned residences since the hotel’s opening.21 While the hotel claims to host anyone and everyone and have equal access regardless of political or national identity, a friend of mine who visited told me that when they went, the Rabbis had to travel to the hotel in the trunks of cars. In contrast, another friend told me she went with a group of Israelis, and they had no issues. This varying set of conditions relating to access highlights the inconsistencies on the ground and tangible barriers to shared space and dialogue.

Evaluation

The aspects of this hotel that make it fascinating in the context of this graduate project are the unique sarcastic and ironic discourses Banksy engages through the art and décor of the hotel and with the adjacent Separation Barrier. Walls like this one represent a nation’s desire or ability to control land and its edges. Graffiti and engagement with the wall directly confront the nation’s ability to control- visually debating and arguing back.22 Author of Conflict Graffiti (2022), John Lennon suggests that projects like this one created by international artists with no regionspecific lived experience often erase the realities of colonized peoples and lands that their work set out to highlight.23 Taking a satirical approach to this hotel was certainly a valid mechanism for encouraging dialogue, reflection, and engagement with the conflict on a different level. Its associated site, art, and décor reveal ideological keystones that challenge notions we think we understand and shine a new light on perspectives of the conflict that are necessary. In a sense, this project is a form of non-violent activism: holding value and principal commentary under the guise of irony and shield of humour.

Takeaways

I have always been intrigued by projects with ironic underpinnings, questioning what makes something art or landscape. Who makes those decisions? World-renowned landscape architect Martha Schwartz frequently addresses these questions, especially with her Bagel Garden. Landscapes may harness form-making and aesthetics to achieve restorative qualities, but they may hold meaning and prompt visitors to leave with new perspectives. As seen with the Walled Off Hotel, locals and tourists alike are immersed in dissonance. A space of cheeky jokes juxtaposed with one of the most severe manifestations of cultural division. Friends of mine who have visited describe it as fascinating in its site and approach to putting the many complicated facets of the conflict into words and art. However, Lennon (2022) makes the excellent point that despite good intentions, Western bias seeps into the work of artists and landscape architects alike. This bias may undermine the difficult issues facing local communities of which they are not a part and which they do not fully understand.24 This bias must be acknowledged, and there should be space in a project such as this for the local communities to actively engage with the concepts and sites the project seeks to address.

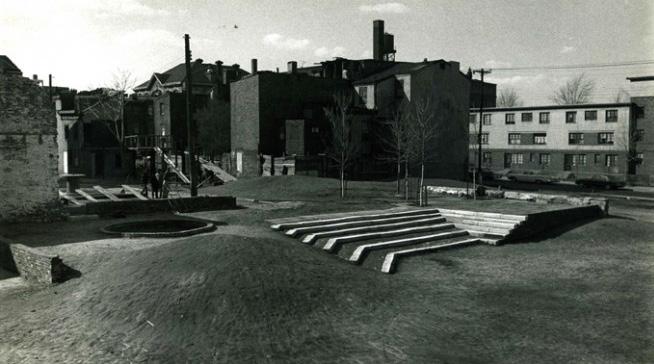

Melon Neighbourhood Commons

Location: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Designers: Karl Linn with Students + Community Members

Year: 1960

While the prospects of Urban Renewal sought to clear American cities of ‘blight’ and promised ‘slum clearance,’ designers like Karl Linn saw potential in the therapeutic properties of landscapes and their capabilities to heal relationships between communities and the urban city. Urban renewal affected most cities in North America, including so-called Vancouver, where white supremacist and segregationist planners like Harland Bartholomew began redlining marginalized neighbourhoods to ‘clear’ urban cities of the ‘cancer’ of ‘slums.’25 Similar stories of racist urban policies imposed by urban renewal were well underway in Philadelphia, where Karl Linn had been appointed a faculty position under Ian McHarg at the University of Philadelphia in 1959.26

Fearing Nazi persecution in Germany, Karl Linn’s family fled to Palestine in the 1930s where he helped found a Kibbutz.27 Being very familiar with Kibbutzim myself, as my grandparents met and were married on a Kibbutz, and many family members still live on Kibbutzim in Israel, I understand the sense of community and land stewardship that these places support. Karl Linn moved on to study psychology, but his background in agriculture on the Kibbutz led him to appreciate nature’s role in peacebuilding and healing.28 Linn saw empathy and emotion as potential pathways through which designers could unite and heal broken, segregated, or alienated communities.29 Melon Neighbourhood Commons became Linn’s pilot project in his journey to present an alternative to urban renewal focused on participatory engagement. He re-framed the view of the Melon site from ‘park’ to ‘Commons.’ He imagined that the site would serve as a hub for political activism and social life and strengthen collective identity.30 These goals, he hoped, would be achieved through the careful use and re-use of materials and thoughtful design.

The conceptual design process began by observing neighbourhood residents and how they operated in their current public spaces. He and his design students began observing how residents created spaces for themselves as extensions of their homes and community. They saw a need for safe and accessible play areas for children and accessible open spaces for youth and adults alike.31 After receiving funding and permission to re-envision the site, Linn arranged a meeting between his students and the residents of this primarily Black neighbourhood in hopes that it would support deepened compassion and empathy in his majority white and privileged students.32 Setting the foundation of respect and compassion propelled them into the construction phase, a cooperation effort between community members and students. The team salvaged as much material as possible as Linn believed this strategy would reaffirm community identity.33 In his book Building Commons and Community (2007), he writes:

“In human habitat, as in coral reefs, the incremental historical deposits of a place imbue the physical environment with a feeling of timelessness. Residues of former buildings, trees, and landscape features create an air of familiarity.”34

-Karl Linn

The overall design of Melon Commons was a ‘hybrid urban-naturalist scheme’35 with its amphitheatre embedded among rolling hills. The team saw potential in the existing rolling topography for play and gathering. Flagstones recovered from nearby demolished sidewalks, found boxes of mosaic tiles, and marble salvaged from doorsteps36 instilled a familiar sensitivity on site. Many local craftspeople, servicepeople, and elected officials kindly donated support, time, expertise, and materials, including trees and mechanical augers. As soon as the play equipment had been installed, children flocked to the site and families were relieved when Linn informed them that there would be no limited play hours or access like other parks.37 After completing the commons, the team established the Neighbourhood Renewal Corps (NRC) to rally local volunteers and guide them in other neighbourhood grassroots efforts.38 Moreover, the NRC engaged in many emerging civil rights efforts and imagined futures far beyond Melon Commons. Unfortunately, the felt effects of urban renewal racist schemes and redlining trickled deeper into the Melon Neighbourhood, forcing many homeowners to set their own homes aflame to collect insurance money as they were denied loans for home improvements and conditions deteriorated. This exodus of residents left the Commons’ state to depreciate to the point where it was designated to be demolished. Eventually, the empty lot gave way to fenced-in high-rise construction. In his book, Linn expresses guilt for what happened at the site, wishing maybe he had been there to stand in front of the bulldozer himself.39

Evaluation

Karl Linn set out to oppose the racist prospects of urban renewal at a time when many designers were busy responding to contemporary modernist challenges with new technologies or trying to have dominion over nature. His ethos is unparalleled. He valued community engagement and participation far beyond what many designers now consider engagement or outreach. Melon Commons showed marginalized community members that they can and should see themselves in their public spaces and that they have a stake in such places. While the commons’ design isn’t the most extravagant or outstanding creative expression, it radiates beauty in its cooperation efforts and legacy. Its demise and eventual demolition underscores the evolutionary nature of culture and the impacts of large-scale urban planning failures.

Takeaways

After reading about Karl Linn and his philosophies on design and his works, I saw many parallels between his intentions and mine. I also can understand how his life experiences shaped his viewpoints. Linn and my late Saba both grew up on tree farms and kibbutzim and placed extraordinary value on community participation in shaping the land we live on. In Linn’s design work, one of the primary strategies he employed was using salvaged materials to kindle a sense of belonging and familiarity with the designed space. Moreover, he engaged local community members in the design and construction process so they could feel included in shaping their own public space and make new connections with place. These are strategies that would be wise to adapt to this graduate project. While I cannot physically visit the community and have them aid me in design and construction, there is still room for intended community input and participation on all levels. Additionally, I think there is a lot to learn from this project’s influence following its construction as it attempted to propel civil-rights efforts forward and be a model for equitable urban space.

Conclusion

The three projects outlined in these precedent studies feature a range of approaches to engaging community members, telling stories, and coping with conflict on various scales. While the Freedom Park and the Melon Neighbourhood Commons are not located in the region of Israel/ Palestine, they both offer valuable approaches that ultimately led their communities to feel heard, understood, and respected. The use of irony and humour in Banksy’s Walled Off Hotel may not be as applicable to this project, but it is nevertheless exciting to study its reception by the public and light-hearted take on such a tense site. In conclusion, the projects selected exhibited a need for culture-specific design processes with true intentions to progress forward and reflect on the past or present.

Endnotes

1. “Truth Commission: South Africa,” United States Institute of Peace, December 1, 1995.

2. Michele Jacobs, “Contested Monuments in a Changing Heritage Landscape: //hapo Museum, Freedom Park, Pretoria,” De Arte 51, no. 1 (2016): 89.

3. Jacobs, “Contested Monuments in a Changing Heritage Landscape,” 90.

4. Jacobs, 90.

5. “The Freedom Park,” Landezine, September 4, 2012.

6. Jacobs, 90.

7. Jacobs, 90.

8. Jacobs, 90.

9. Jacobs, 92.

10. “The Freedom Park //Hapo (Museum),” GREENinc Landscape Architecture + Urbanism.

11. “The Freedom Park,” Landezine.

12. Sabine Marschall, “Chapter 7. Freedom Park As National Site Of Identification,” In Landscape of Memory. 2010, 216.

13. Marschall, “Freedom Park As National Site Of Identification,” 231.

14. Colum McCann, Apeirogon: A Novel, First ed, New York: Random House, 2020, 308.

15. Ian Fisher, “Banksy Hotel in the West Bank: Small, but Plenty of Wall Space,” The New York Times. April 16, 2017.

16. Tommaso M. Milani, “Banksy’s Walled Off Hotel and the Mediatization of Street Art,” Social Semiotics, no. ahead-of-print (2022): 1.

17. “Facilities,” The Walled Off Hotel.

18. Milani, “Banksy’s Walled Off Hotel and the Mediatization of Street Art,” 2.

19. Jamil Khader, “Architectural Parallax, Neoliberal Politics and the Universality of the Palestinian Struggle: Banksy’s Walled Off Hotel,” European Journal of Cultural Studies 23, no. 3 (2020): 477.

20. Tristan Davis, “Welcome to the Walled Off: A Visit to Banksy’s Hotel in Bethlehem,” The Jerusalem Post, March 17, 2018.

21. Davis, “Welcome to the Walled Off,” 2018.

22. John Lennon, “Erasing People and Land,” In Conflict Graffiti: University of Chicago Press, 2022, 101.

23. Lennon, “Erasing People and Land,” 102.

24. Lennon, 105.

25. Nicole Dulong, Samantha Miller, and Reece Milton, Hogan’s Alley Site Guidelines (Vancouver: University of British Columbia, 2021), 71.

26. Alison Bick Hirsch, “From “Open Space” to “Public Space”: Activist Landscape Architects of the 1960s,” Landscape Journal 33, no. 2 (2015): 187.

27. Anna Goodman, “Karl Linn and the Foundations of Community Design: From Progressive Models to the War on Poverty,” Journal of Urban History 46, no. 4 (2020): 796.

28. Goodman, “Karl Linn and the Foundations of Community Design,” 796.

29. Goodman, 796.

30. Goodman, 797.

31. Karl Linn, Building Commons and Community, Oakland, CA: New Village Press, 2007, 81-82.

32. Linn, Building Commons and Community, 83.

33. Goodman, 798.

34. Linn, 84.

35. Goodman, 798.

36. Linn, 87-89.

37. Linn, 89.

38. Linn, 90.

39. Linn, 96-97.

Part 3: Stories and Counter Stories

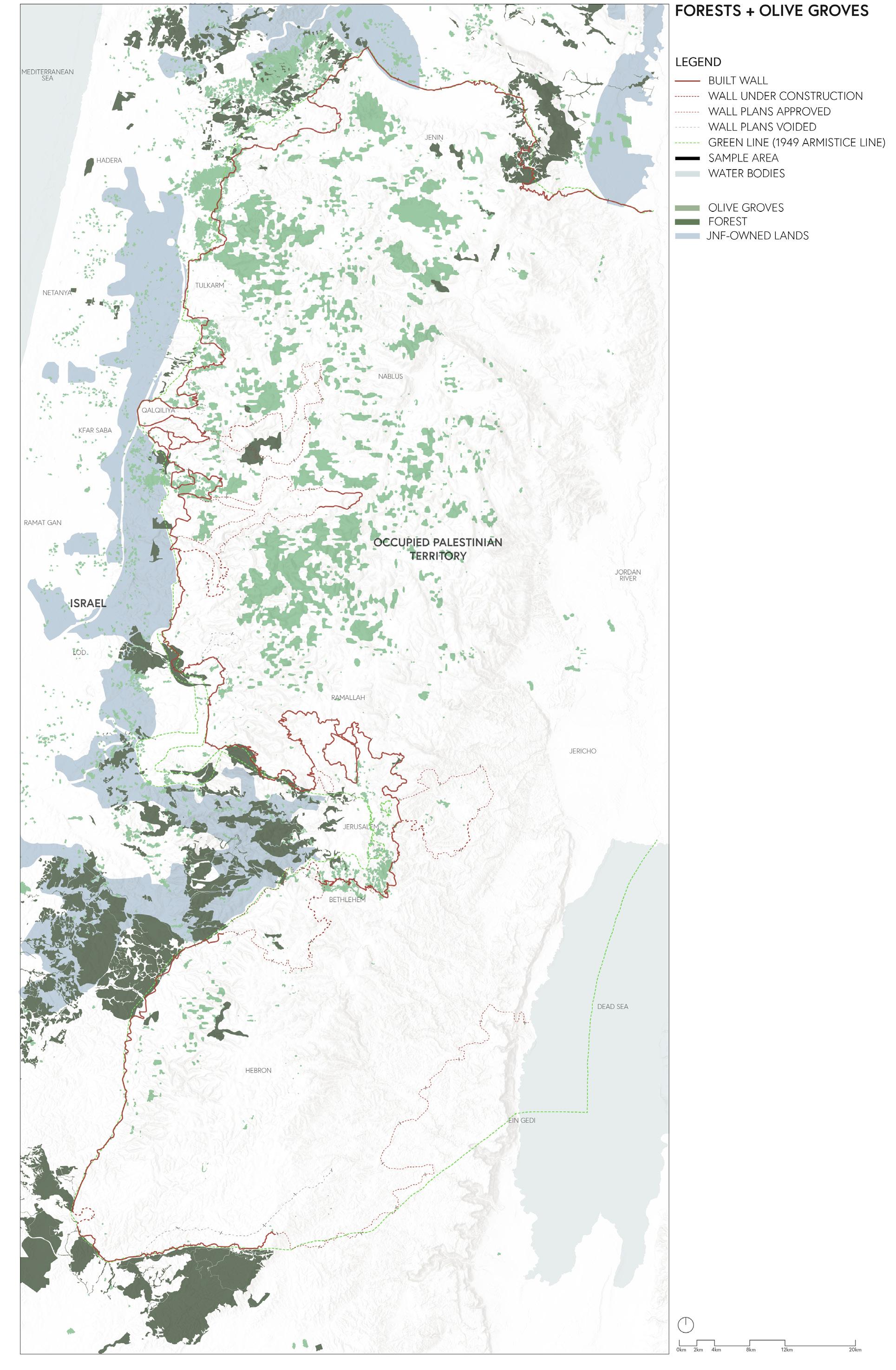

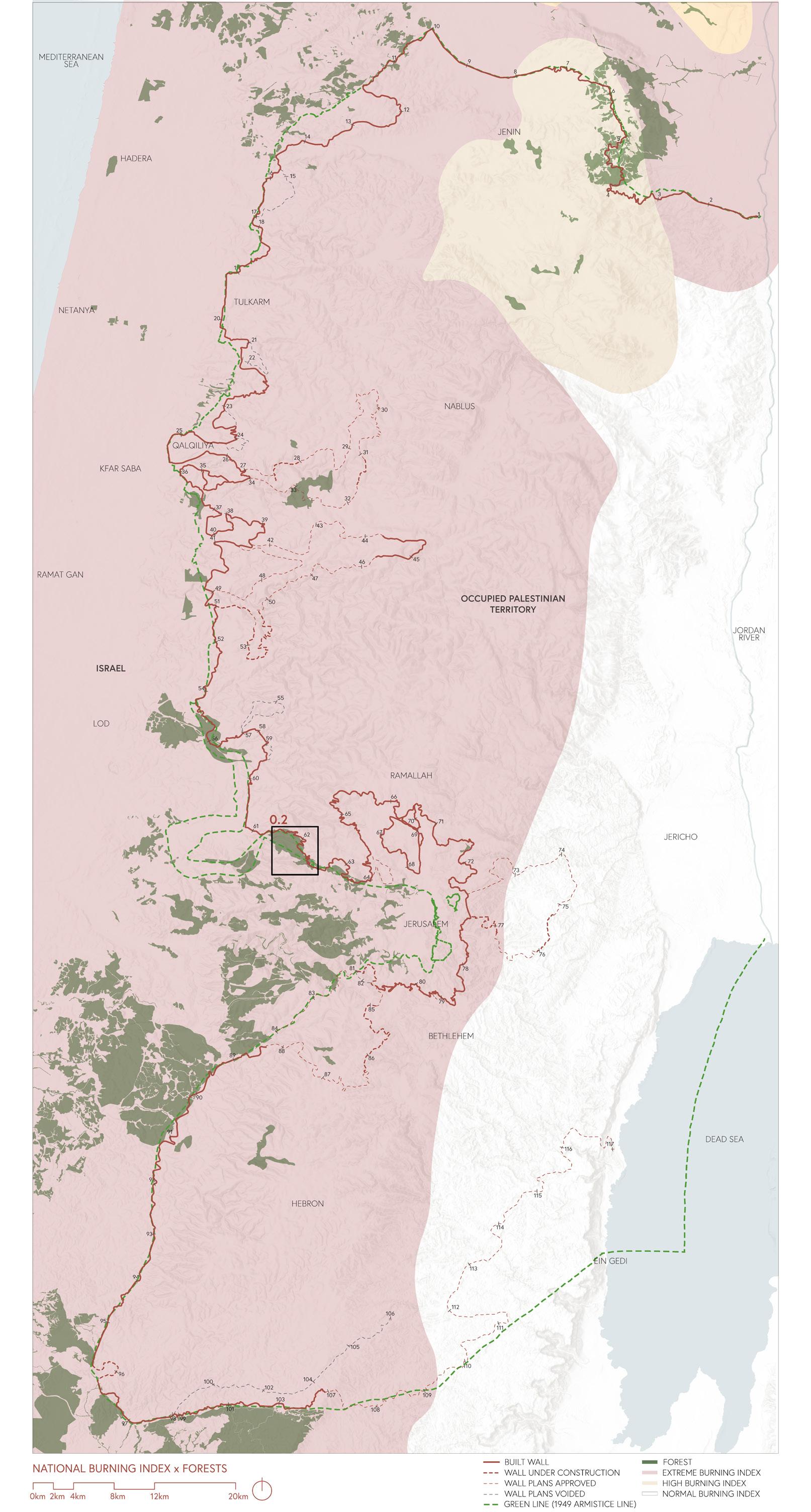

Looking to the olive, the pine, and other landscape architectural practices, the following three design proposals are framed as stories/ counter stories. Each story is chosen due to its proximity to the wall, its exemplification qualities of being used as a weapon or nation-building tool, and its opportunity for peacebuilding or healing at different scales. They begin with a description and example of a specific site and strategy in which the olive or the pine has been used as a proxy-soldier or proxy-nation-builder. Then, a counter-story (the design proposal) is offered to begin healing lands and nations simultaneously. In this way, we can acknowledge facts on the ground, power imbalances, and traumas and respond to them with empathy.

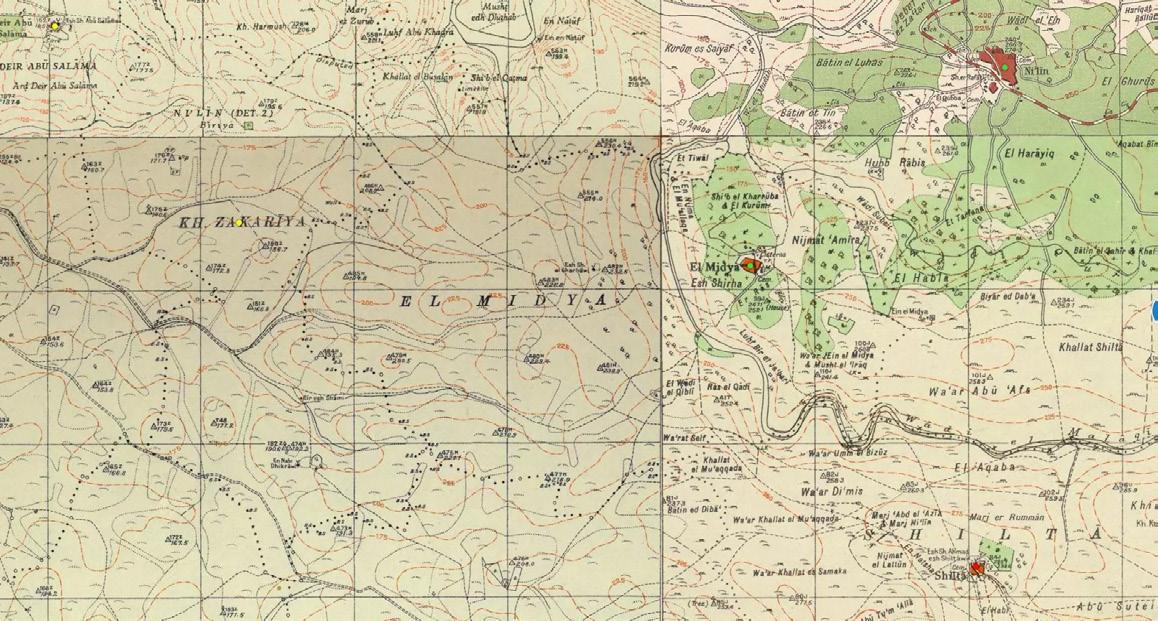

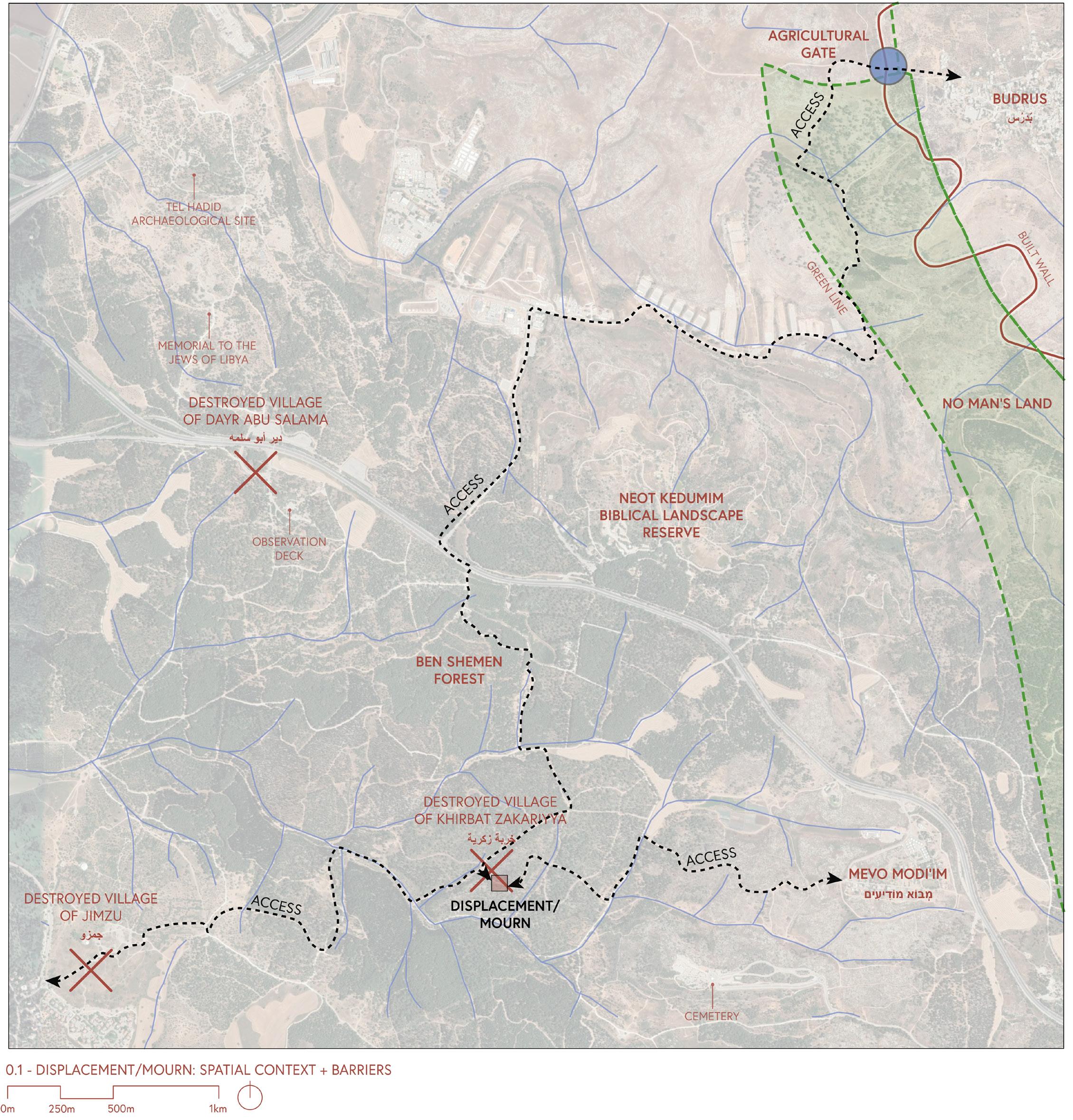

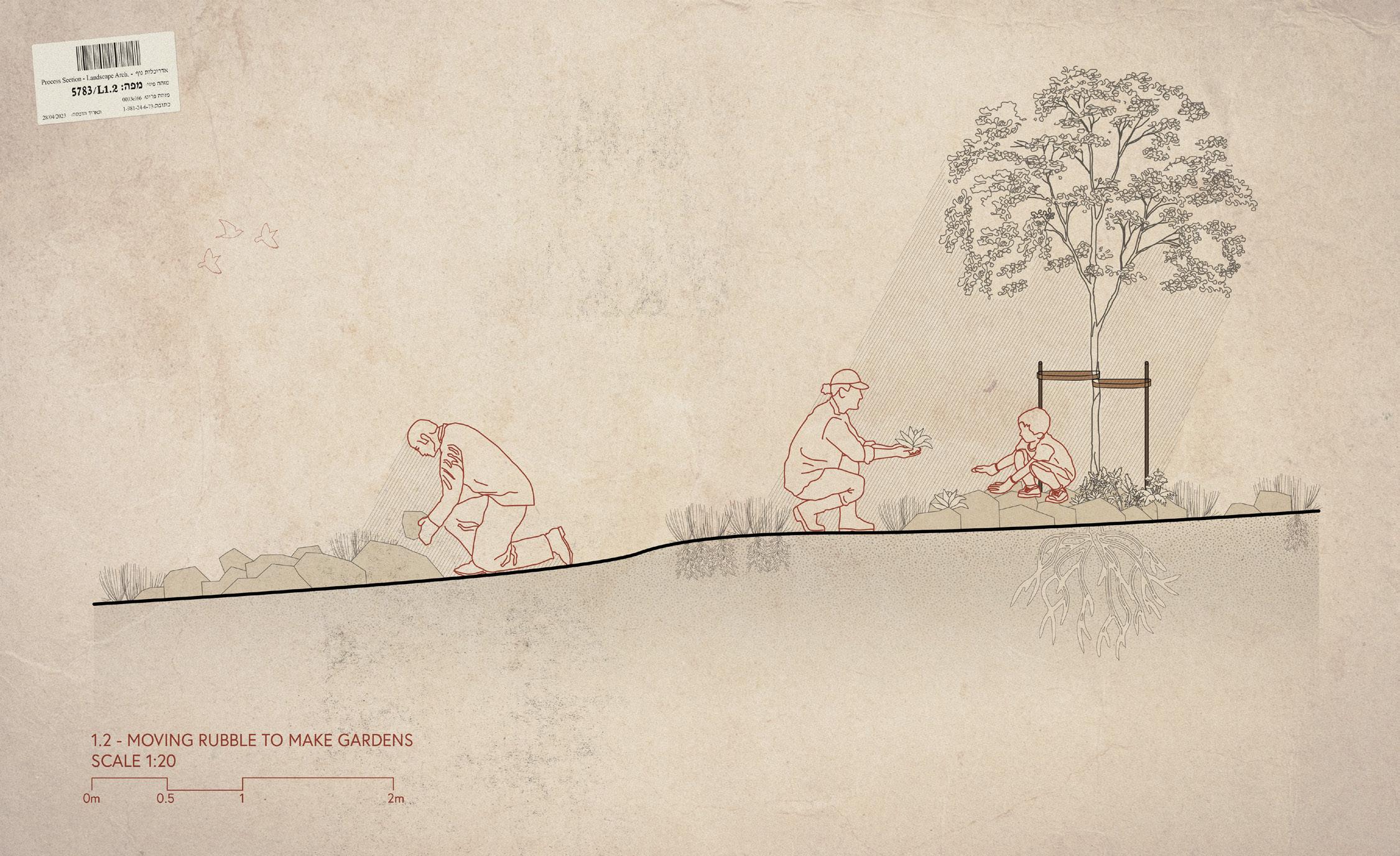

Displacement

The site of this intervention is what is now known as the Ben Shemen Forest, located near Ramallah. The forest is primarily comprised of pines planted by the JNF. The vast forest lands sit on the sites of destroyed Palestinian villages, depopulated during the Nakba in 1948 or in the Six-Day War of 1967. A practice of erasure that is far too common amongst the sites of JNF forests. Of the 418 Palestinian villages displaced during the Nakba, almost half are now the locations of nature parks, forests, or nature reserves.1 This fact is often a prominent proponent of debates surrounding the heart of the JNF’s intentions, some arguing that their afforestation policies were meant to prevent Palestinians from returning home, forcing them to find a new home elsewhere in the surrounding Arab countries.2 The sites of these destroyed villages are left in varying conditions under these pine trees. The focus of this story is the remains of Khirbat Zakariyya. According to Palestine Remembered, the 4500+ inhabitants of Khirbat Zakariyya/ ةبرخ ةيركز were completely displaced from their lands and homes in 1948.3 Palestinian historian Walid Khalidi describes the remains of the village today by writing:

“From a distance, the village appears as a bare hill overgrown with thorns and other wild vegetation. The remains of village wells and the cut stones that were used to cover them are visible.”4

-Walid Khalidi

Political violence blurs the boundaries between the “war front” and the “home front.”5 One study on Palestinian women’s mental well-being found that anxiety and grief were consistent as there is agony in being unable to derive comfort within their environment.6 There are numerous tales of incredible internal breakthroughs occurring through seeing the ‘other’ grieve. Palestinian activist Ali Abu Awwad grew up in a politically active family, participating in resistance efforts which got him arrested. After being released from prison, he found was shot in the leg during the Second Intifada, and later, his brother was killed by a soldier at a checkpoint. He was chockfull of anger, grief, and pain. Eventually, he joined the Parents Circle Families Forum. In his 2015 Ted Talk, he expressed his shock after realizing Jews had emotion and could cry. Now, he works to spread a message of non-violent activism and reconciliation.7 A similar tale is told in Apeirogon: A Novel by Colum McCann, based on the true-life friendship of two grieving fathers, one Palestinian and one Israeli. McCann describes the Israeli father attending his first meeting at the Parents Circle Families Forum (an organization created to gather grieving people who want peace), writing:

“On and on they came, so many of them… And I remember seeing this lady in this black, traditional dress, with a headscarf- you know, the sort of woman who I might have thought could be the mother of one of the bombers who took my child. She was slow and elegant, stepping down from the bus, walking in my direction. And then I saw it, she had a picture of her daughter clutched to her chest. She walked past me. I couldn’t move. And this was like an earthquake inside me: this woman had lost her child. It maybe sounds simple. but it was not. I had been in a sort of coffin. This lifted the lid from my eyes. My grief and her grief, the same grief.”8

-Rami Elhanan via Colum McCann

When a person dies, the most common Jewish practice, regardless of the degree of religiousness, is to sit Shiva. Shiva is a seven-day mourning period in which the bereaved receive visitors to pray, eat, and be comforted at their homes. There is a powerful notion here of having friends, family, community members, and even acquaintances all come to the aid of the bereaved so they are not alone and are fed and cared for. Having space to grieve and be comforted is critical in healing on an individual and community level.

Unfortunately, being someone or knowing someone who has lost a loved one due to this ongoing conflict is almost a right of passage in this land. But this idea of grieving does not strictly apply to people grieving the loss of a loved one. We can grieve the loss of a home, a sense of community, of land, or an olive tree. There are stages of grief that require unique conditions to meet the needs of each stage. Grief is a universal human experience and feeling. It can be shared and recognized if there is space and time.

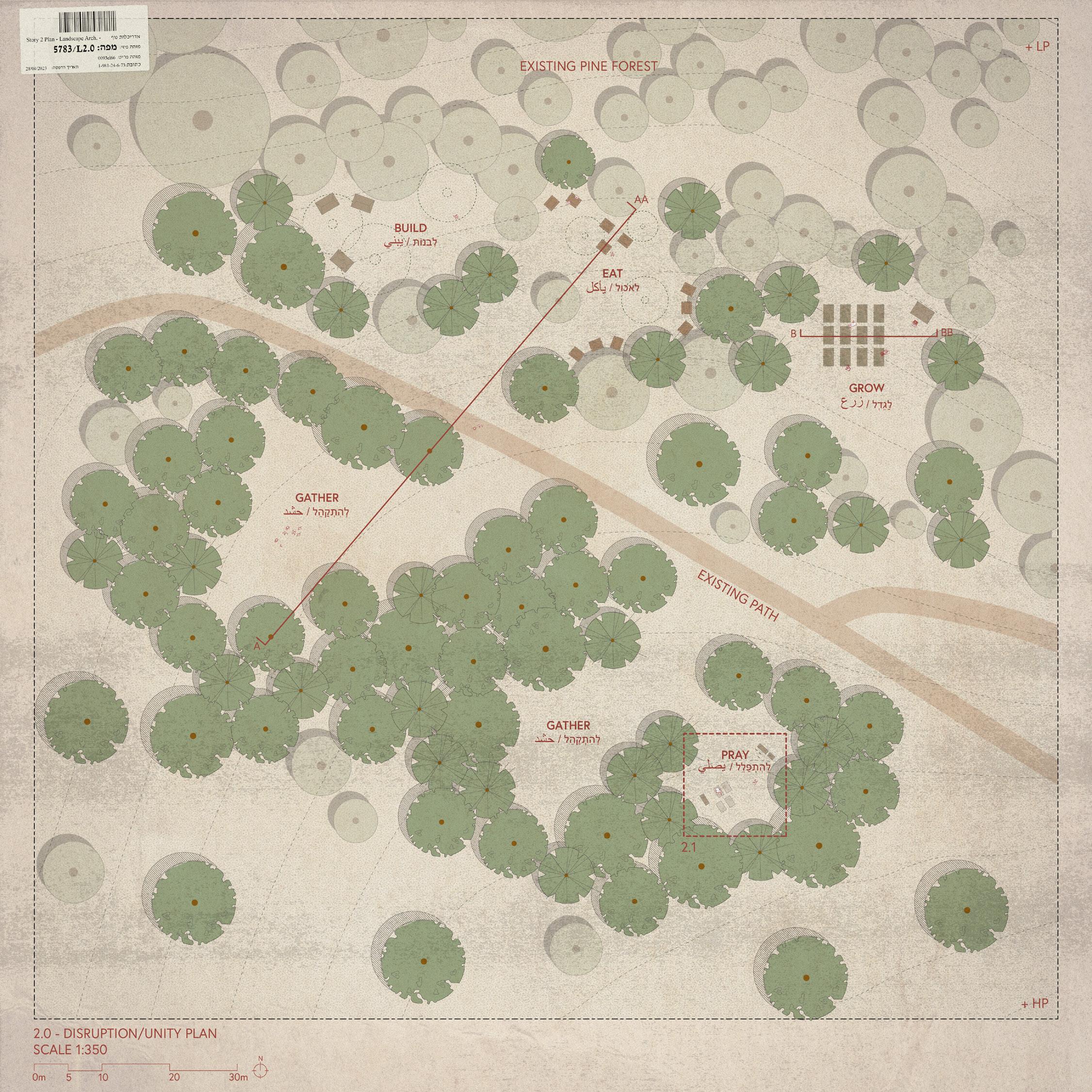

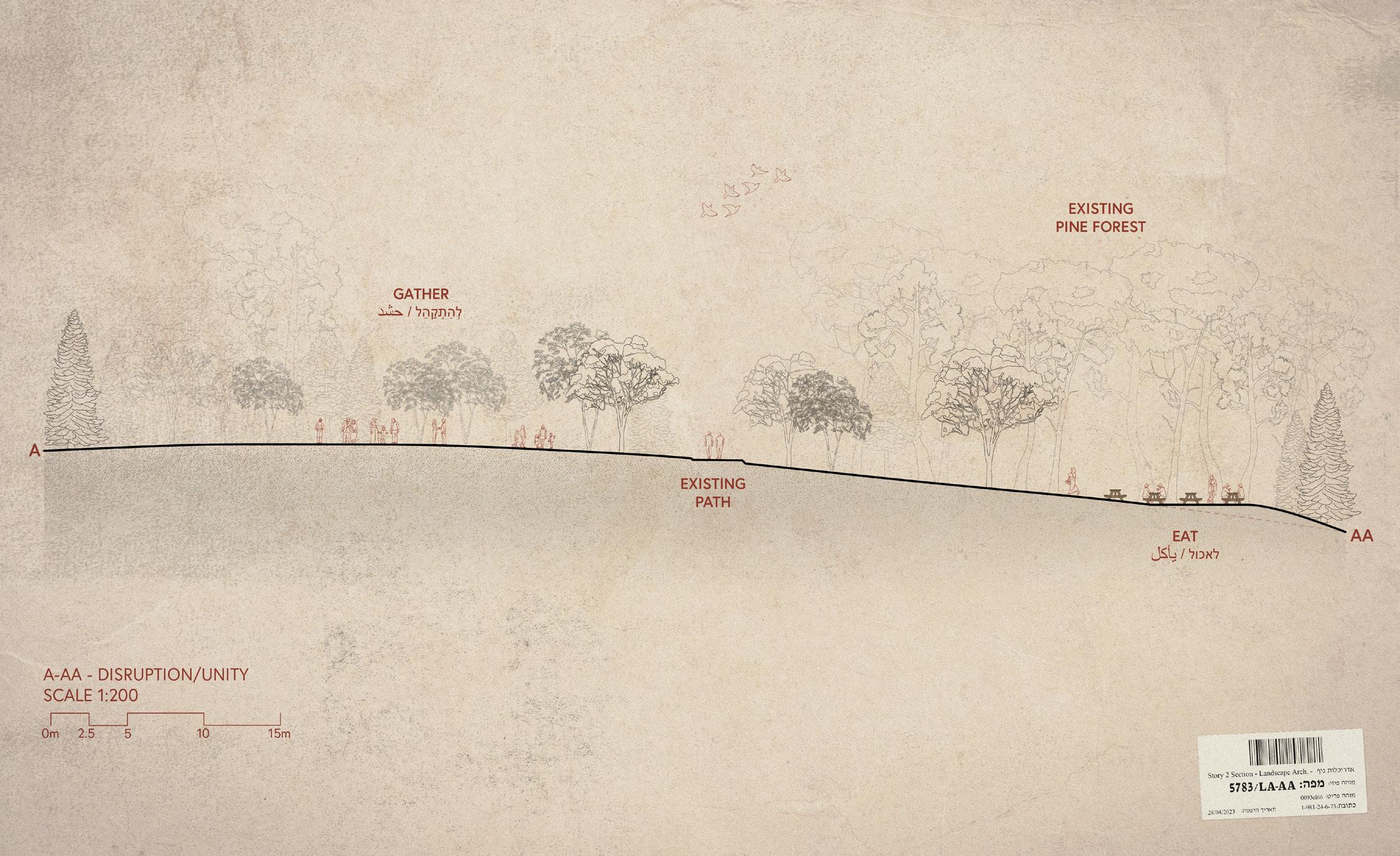

Disruption

Due to many of these pine forests being close to walls and therefore close to Palestinian towns shadowed by the wall, the exceptionally flammable nature of the tree’s resin, and their potent symbol of Jewish rootedness, they have become a frequent victim of arson attacks. Since the beginning of the First Intifada, over 900 fires have been started in JNF forests, most of which have been deliberately set by Palestinians.9 A Jerusalem-based newspaper even published a cartoon illustrating “tree burning certificates” being handed out by the Palestinian Authority, referring to the “tree planting certificates” offered by the JNF after donating into the blue tins.10 Underground Palestinian terror organizations often set out calls to commit terror and instructions on how to start forest fires.11 After a large forest fire incident in 2010, forest fires became recognized as deliberate and premeditated strategic terror tools.12 The site of this intervention is the HaHamisha forest located in ‘No-Man’s Land.’ Set ablaze in 2016, the fire started near Oasis of Peace/Neve Shalom/ Wahat al-Salam, a coexistence community near the intervention site and the recipient of several peace-related awards. Fires quickly spread across forests outside of Jerusalem, and fires were spontaneously started in other areas of the country. However, unity and community showed its face in this devastating form of disruption. Firefighting aircraft and aid arrived from Bulgaria, Cyprus, Croatia, France, Greece, Italy, Romania, Spain, Turkey, and even the Palestinian Authority.13

Unity

There is demonstrated need for gathering and coexistence space, with Oasis of Peace/Neve Shalom/Wahat al-Salam nearby and gatherings of activist groups around the country in the thousands. No-Man’s Land is a promising contender for facilitating this space, as expressed in the writing of political geographers, Noam Lesehm and Alasdair Pinkerton:

“Contrary to the absence assumed in its name, we demonstrate that no-man’s land is a highly active space: it is constantly produced and transformed by a multitude of actors, and in turn, is itself a transformative and generative space, opening new horizons of political action and social interaction.”14

-Noam Lesehm and Alasdair Pinkerton

Healing processes are most likely to occur when the individuals in conflict sit down in dialogue and are actively engaged in managing conflict15, rather than formal leaders or agencies making decisions around a boardroom table. Documentation and research examining the successes and failures of Israeli Palestinian dialogues have shown that more powerful sessions involved the practice of deep listening, best achieved in person. This means that one must suppress their sub-vocal objections and tendencies to be contrary to the person speaking to ensure they feel understood and heard.16 In recent years, testimonial stories of the horrors of war and its long-lasting personal consequences are a necessary therapeutic process and imperative to healing.17 In situations like these, participants often felt personally involved in the other’s narrative. As a result, they began feeling apologetic even though they were not the ones who directly inflicted the terror on the other. Most importantly, as examined in the literature review, space must be created to facilitate dialogue and peacebuilding in divided communities. This notion rings true in my own experiences within my Israeli/Palestinian dialogue group, رسج/Bridge/רׁשג. The first time we met in person, it was outdoors at a park. The big maple tree sheltered us, and the picnic tables hosted the traditional foods the members had brought to share. From that day on, after having that space to gather and meet in person, whether our meetings were online or not, we felt comfortable with each other and trusted each other with our tears and stories.

Uproot

The olive tree is not just a cultural symbol or a facet of Palestinian life and economy; it is also a political entity. It is slow-growing but long-living, drought resistant, and easy to grow in poor soil conditions, which is why it has transcended the eras of varying colonial forces and conquests in Israel/Palestine. It represents rootedness, history, and identity fixed in place. Increasingly in the last two decades, the State of Israel has been uprooting Palestinian-owned olive trees by the thousands. Olive trees have a history of being uprooted in this land since the Ottoman rulers uprooted them as punishment for tax avoidance, and the British Mandatory administration continued implementing these practices. However, Israel claims these uprooting practices are essential for national security.18 Olive trees are being uprooted to make way for the separation barrier, watchtowers and checkpoints, roads, and to increase visibility by removing hiding ground for terrorists.19 In a sense, the State of Israel has bestowed the olive with even more immense power because of its place in the conflict and through the indirect and direct acts of uprooting.20 In one documented dialogue group, the researcher found that many participants were stubborn to accept the causes of human rights violations as other members frequently attempted to justify them. In this dialogue session, participants were shown a photograph of an older woman holding onto the trunk of an uprooted olive tree. Scholar David Senesh describes this moment, writing:

“The interconnectedness of that woman, the land and the tree… This was a most pervasive visual demonstration of interconnectedness in an all-ornothing irreversible situation, where an uprooted tree symbolized death and despair… When Israelis can apologize for the uprooted tree, the Palestinians can invite them to sit in its shade and feel safe from threats of extermination.”21

-David Senesh

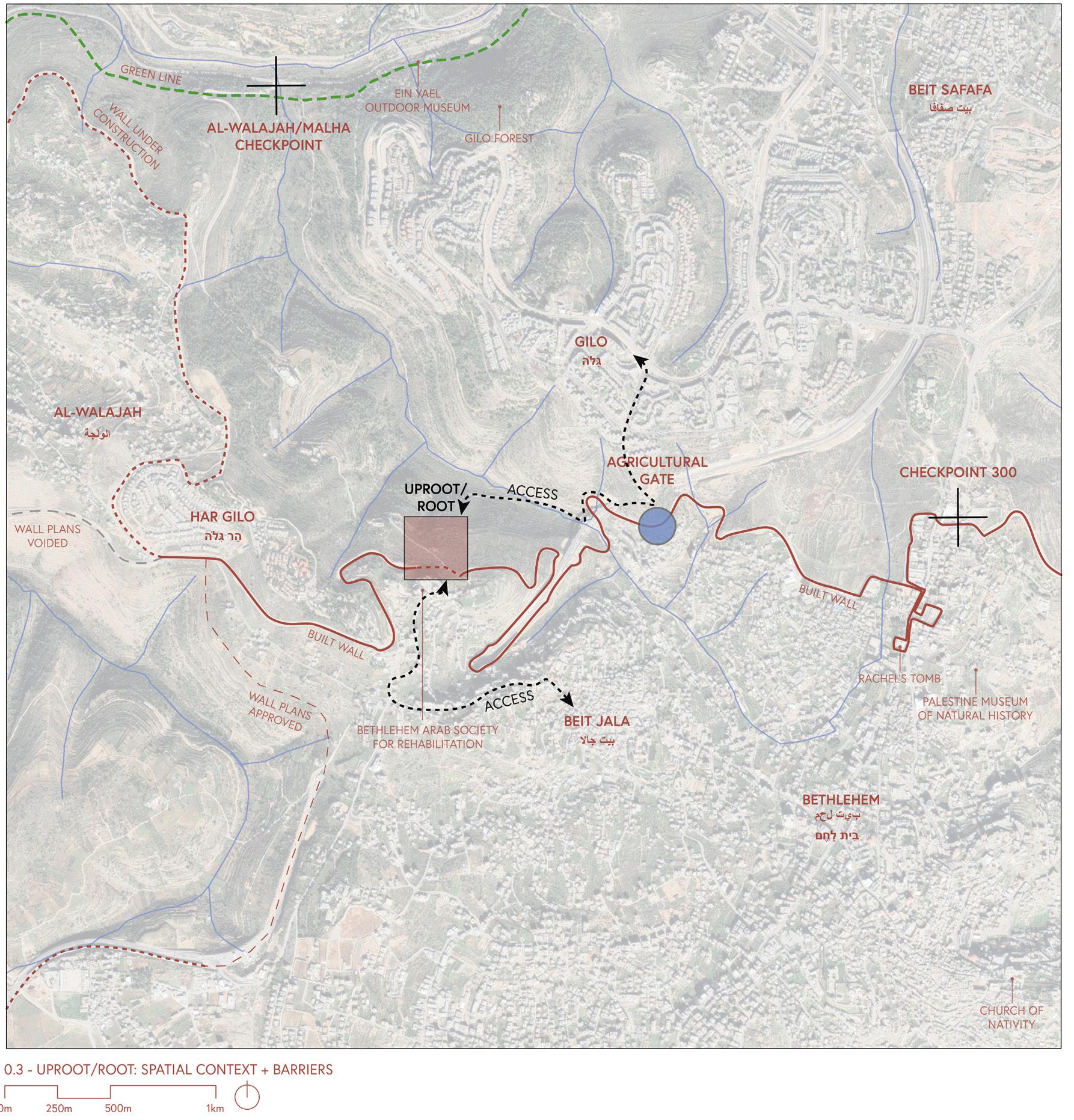

In 2015, in Beit Jala, right outside of Bethlehem, Israeli machinery began the construction of the wall, uprooting olive trees as it went. The proposed plan for the wall (while it remains unfinished) will make privately owned farmland in the Cremisan Valley inaccessible to Palestinian farmers in Beit Jala.

Root

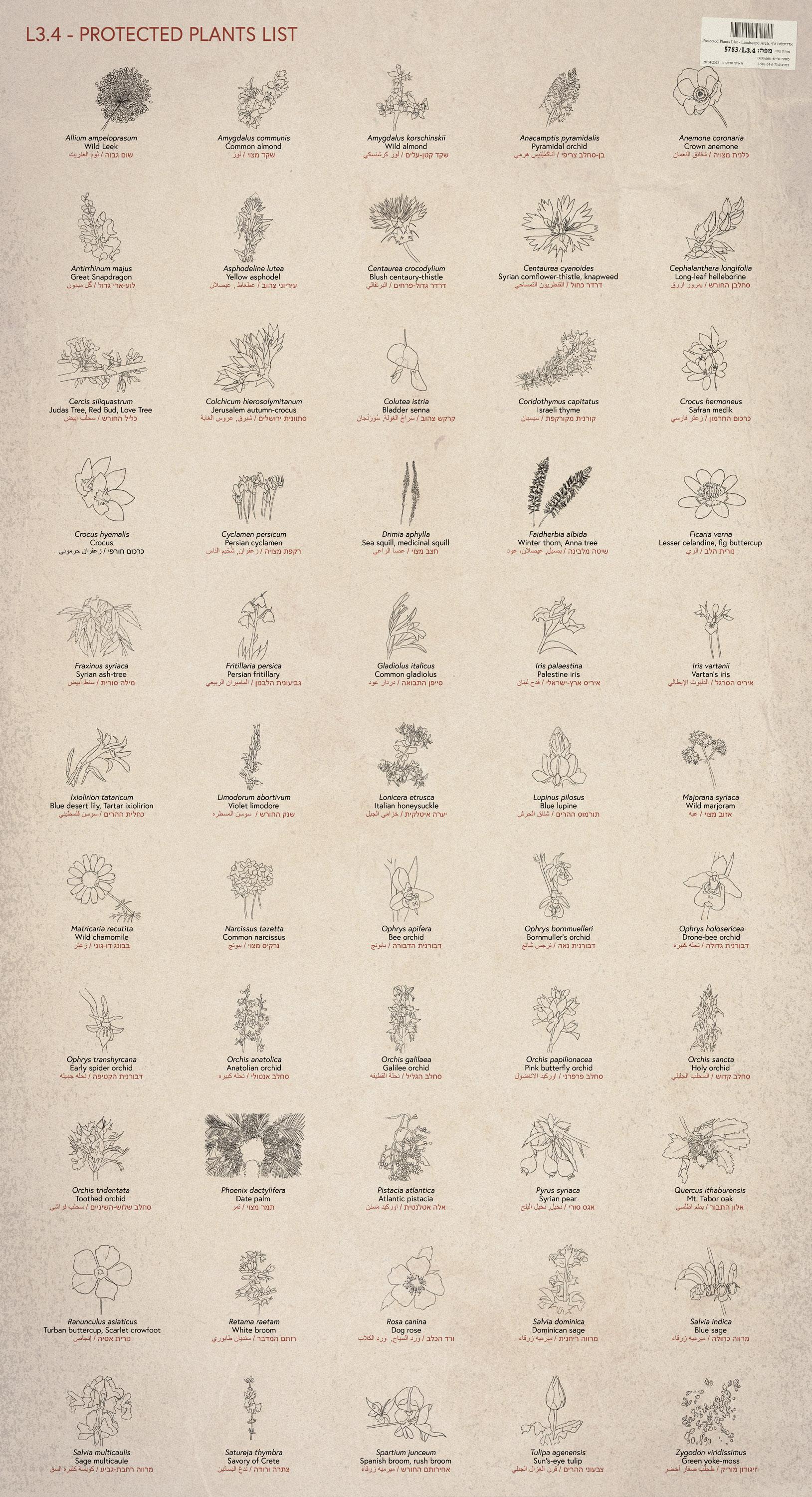

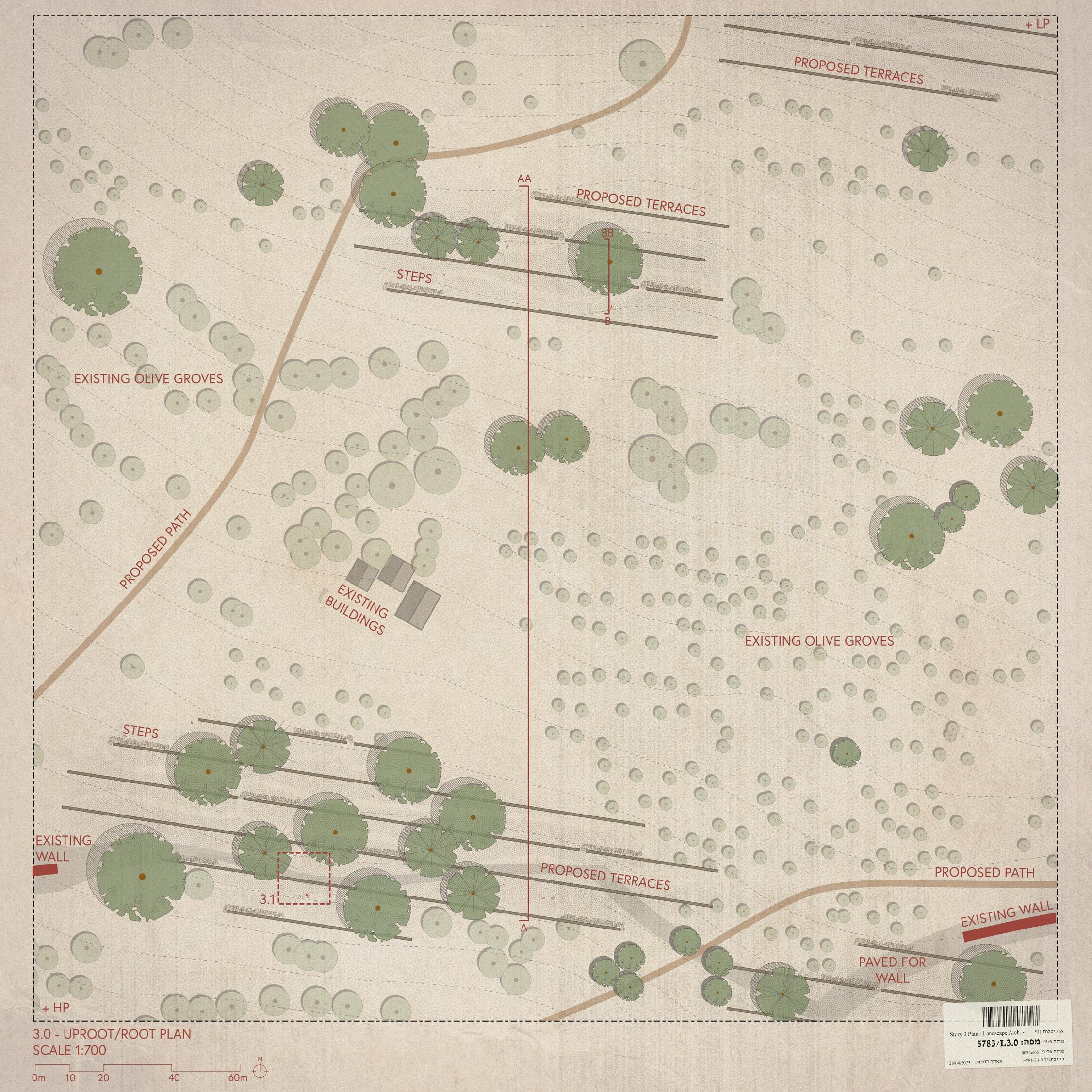

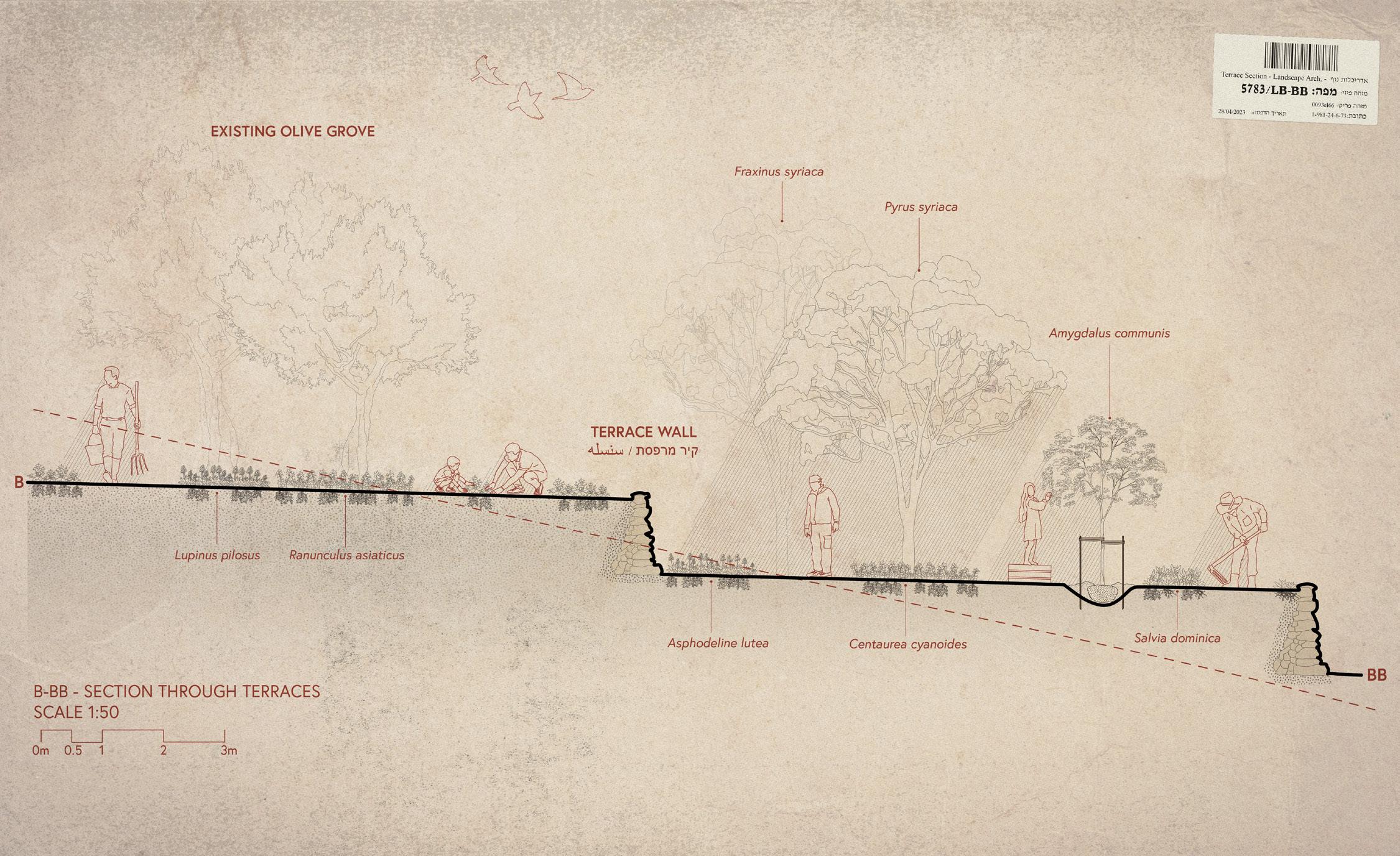

It would be naive to propose planting olive trees or transplant uprooted olive trees and call it ‘rooting.’ Olive trees, and pine trees for that matter, are not protected under Israeli Law and thus subject to continuous uprooting. However, in 1964, Israel published the “Protected Natural Values” Law, which includes a list of protected species that has since been continually revised.22 By planting these rare and protected species in the land where the wall has not yet been constructed and by using traditional land practices to do so, this proposal hopes to reinforce rootedness in the landscape and protect Palestinian land sovereignty and livelihood. While this intervention is less so about increasing interrelations between Palestinians and Israelis, it’s important to recognize that the Palestinians are the ones who are occupied and oppressed today, and this effort focuses on their security and maintaining their livelihood.

Endnotes

1. Irus Braverman, Planted Flags: Trees, Land, and Law in Israel/Palestine, Cambridge University Press, 2014, 99.

2. Braverman, Planted Flags, 99.

3. “Zakariyya, Khirbat - Al-Ramla,” Palestine Remembered, Accessed April 30, 2023, https:// www.palestineremembered.com/al-Ramla/ Zakariyya,-Khirbat/index.html.

4. “Zakariyya, Khirbat,” Palestine Remembered.

5. Cindy A Sousa, Susan Kemp, and Mona ElZuhairi, “Dwelling within Political Violence: Palestinian women’s Narratives of Home, Mental Health, and Resilience,” Health & Place 30, (2014): 205.

6. Sousa, Kemp, and El-Zuhairi, “Dwelling within Political Violence,” 211.

7. TedX Talks, “Painful Hope | Ali Abu Awwad,” Youtube, 7 May 2015.

8. Colum McCann, Apeirogon: A Novel, First ed, New York: Random House, 2020, 223.

9. Braverman, Planted Flags, 105.

10. Braverman, 105.

11. Jonathan Fighel, “The “Forest Jihad”,” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 32, no. 9 (2009): 803-804..

12. János Besenyő, “Inferno Terror: Forest Fires as the New Form of Terrorism,” Terrorism and Political Violence 31, no. 6 (2019): 1234.

13. Besenyő, “Inferno Terror,” 1234.

14. Noam Leshem and Alasdair Pinkerton, “ReInhabiting no-Man’s Land: Genealogies, Political Life and Critical Agendas,” Transactions - Institute of British Geographers (1965) 41, no. 1 (2016): 42.

15. David Senesh, “Restorative Moments: From First Nations People in Canada to Conflicts in an Israeli–Palestinian Dialogue Group,” In Peacebuilding, Memory and Reconciliation, edited by Charbonneau, Bruno and Genevieve Parent,

Routledge, 2012, 167.

16. Senesh, 169.

17. Senesh, 169.

18. Braverman, 129-130.

19. Braverman, 130.

20. Irus Braverman, “Uprooting Identities: The Regulation of Olive Trees in the Occupied West Bank,” Political and Legal Anthropology Review 32, no. 2 (2009): 238.

21. Senesh, 172.

22. Avi Shmida, Ori Fragman, Ran Nathan, Zvi Shamir, and Yuval Sapir, “The Red Plants of Israel: A Proposal of Updated and Revised List of Plant Species Protected by the Law,” Ecologia Mediterranea 28, no. 1 (2002): 56.