Samantha A. E. Hubbard

Design Portfolio

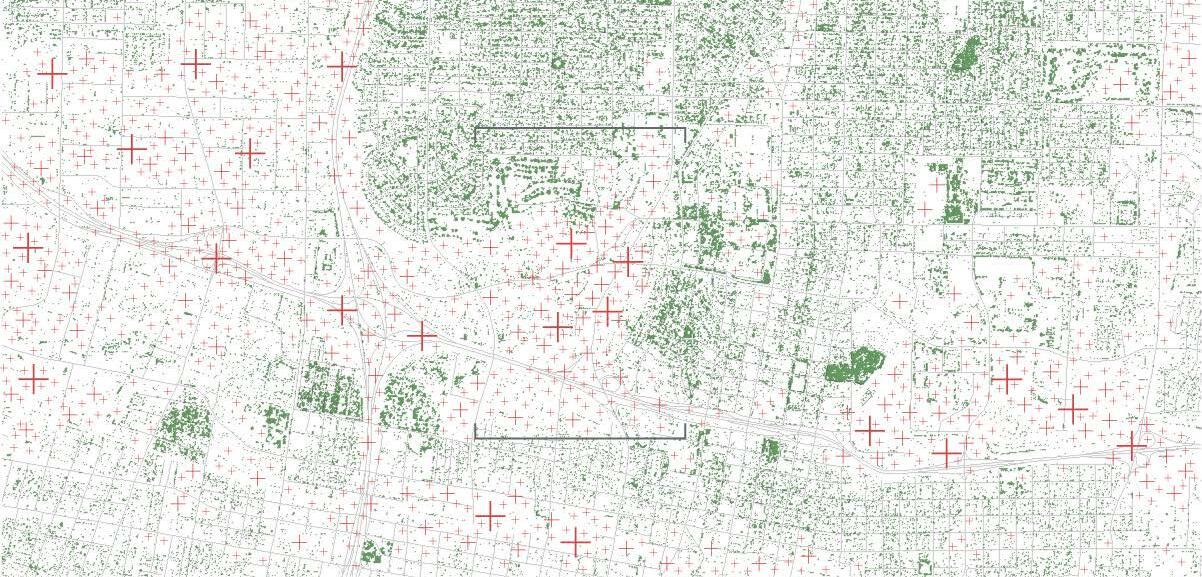

Relationships between naturally occuring drainages, infrastructure, parks and concretized arroyos throughout Albuquerque.

Relationships between naturally occuring drainages, infrastructure, parks and concretized arroyos throughout Albuquerque.

Stormwater Park | Albuquerque, NM

A lbuquerque employs a robust network for stormwater management. With 69 miles of channels, 9 miles of underground drainages, 7 miles of dikes and diversions, 35 dams, and various debris capture stations, the Albuquerque Metropolitan Arroyo Flood Control Authority (AMAFCA) aims to control and divert floodwaters as they move through the city.

Though efficient, this framework 1) speeds up water, limiting groundwater recharge; 2) provides miles of impervious surface for invisible pollutants to collect; 3) increases urban heat island effect (UHIE); and, 4) serves as uninviting and underdeveloped public recreational corridors.

Concretized arroyos contain floodwaters and channel ephemeral streams through indistinguishable and inhospitable landscapes, severing the city from its water. Regenerative Reuse connects the city with its hydrologic cycle by hybridizing channels and reviving land along the Arroyo de Domingo Baca. Spring 2021

Individual Work

University of New Mexico

Instructors: Kathleen Kambic + Katya Crawford

ARCH 402/LA 402: Urban Typology LA Design Studio II

Bioswale Detail

Potential Intervention Zones Terraced

walking path Diversion Channel

water canal primary water canal

x 75’ RV plot parklet

terraced park bioswale

terraced arroyo

gabion bridge Site Plan

At the intersection of the Arroyo de Domingo Baca and the North Diversion channel, the ground plane will be torn and stretched to make new space for water, people, and wildlife alike.

By redefining the genus loci of this over-engineered channel, uninviting RV lot, and other potential sites throughout the city, Regenerative Reuse unpacks Albuquerque’s relationship to water, allowing visitors to understand the importance of natural processes and cohabitation in urban ecology.

Waterfront bike + walking paths.

From 2012 to 2015, Sweden accepted roughly 40,000 refugees per year. Numbers increased during the crisis in 2015, and 162,877 asylum seekers entered Sweden that year alone. Though Sweden, and the city of Stockholm, have become a new home to hundreds of thousands of refugees, they struggle to assimilate to life in Sweden. University students have had a uniquely challenging transition into the Swedish education system and culture.

In Swedish, tröst is a noun meaning solace and comfort. Many refugees need safe spaces to start their new lives. With this in mind, the Tröst community provides the right learning tools, asylum resources, and social environments for refugee students to have a comfortable transition into the City of Stockholm.

Spring 2020

Individual Work

University of New Mexico

Instructor: Clare Cardinal-Pett

ARCH 302: Architectural Design IV

Site, commuter bike lanes, proposed sites, and surrounding universities

The 1.5-acre site sits near more than 20 universities colleges in Stockholm. It is also conveniently one of the city’s multi-lane bicycle “commuter” lowing students to commute to their schools minutes.

Integrated bike and walking paths encourage to live active and outdoor lifestyles. The community ter and attached sauna provide residents with for academic success, assistance in obtaining tus, and smooth assimilation into the Swedish

Allowing this community to serve multiple locations provide students with enhanced resources for success, healthier lifestyles, and assistance in cated and stressful asylum process.

universities and conveniently located on “commuter” routes, alschools within 5-20 encourage residents community cenwith resources obtaining asylum staSwedish culture. locations will for academic the compli-

Traditional Syrian architecture stresses modesty and privacy while Scandinavian culture centralizes around a connection to nature, comfort, and simplicity.

Together, these cultures combine the dichotomies of safety and exposure, privacy and togetherness, and concealed and opened to create spaces of comfort, modesty, and naturality.

Relationships between the Rio Grande, New Mexico Indian Reservations, the Rio Grande River Basin, and Dams + Diversions.

Infrastructural + Ecological Analysis | Pueblo de Cochiti, NM

Though irrigation is necessary for survival in the desert, decades of over-engineered dams and diversions have marginalized many of New Mexico’s pueblo communities. Since its conception in 1956, the Cochiti Dam and Lake have left the Pueblo of Cochiti broken.

As the symbiotic relationship between the people and land weakens, both are fighting for survival. The Rio Grande is often a slow trickle through southern valleys as Cottonwood bosques and wildlife diminish. The Pueblo of Cochiti has lost the ability to cultivate remaining lands, cutting ties to traditional ways of life, and have lost access to sacred lands. As the river goes extinct, so too does the culture of the Pueblo of Cochiti.

The Beautiful and the Dammed unearths injustices against and infringements upon the Rio Grande and Pueblo of Cochiti resulting from the desecrating construction and geographically opportunistic developments of Cochiti Dam, Cochiti Lake, and the Town of Cochiti Lake.

Spring 2021

Individual Work

University of New Mexico

Instructor: Cesar A. Lopez

ARCH 462: Representation As Action

In 1994, the Rio Grande Silvery Minnow was classified as endangered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. It now exists in only 5% of its natural habitat. The fish has gone extinct in the Pecos River and has disappeared south of Elephant Butte Reservoir, where the Rio Grande often runs dry. The depleting Silvery Minnow population has been directly linked to the artificial modifications and alterations to the Rio Grande over the past century.

When the waters of the Rio Grande flowed undisturbed,theRioGrandeCottonwoodthrived in the varying flood conditions.With a lifespan of 100years,themagnificenttreesrequireflooding tosurviveandgerminate.Asfloodcontrolefforts persistalongtheriver,thecottonwoodsaredying off. Most cottonwoods within the Middle Rio Grande Valley are nearing 80 years of age and have not germinated due to alterations in river flows and longstanding drought. Over the next 20 years, with continued drought and irrigation, the bosques of cottonwoods that line the Rio Grande from Cochiti to Belen could disappear.

From Indian relocation efforts in the Dam and Lake in 1956, and water Pueblo of Cochiti continually fights for environmental survival. Once a predominantly the construction of Cochiti Lake agricultural lands, destroyed traditional the ecosystems within and around worship cherished by the Pueblos broughtnewproblemsandlawsuitsas

615 acres of remaining farmland the Pueblo to abandon their rural the Corps eventually installed a damaging native lands, seepage

In 1960, Congress authorized the construction the Flood Control Act. From 1965 Engineers built Cochiti Dam and Lake, 50,000acresoflandownedbythePueblo infightingthedam’sconstruction,the portion of revered land and ancient burial obliged and flagged the lands that were construction,thoselandswerethefirst Corpsarguedthatitwastheonlyplace function.The various pueblos throughout as they saw their ancestral and native

the 1930s, the conception of Cochiti water disputes continuing today, the for its cultural, social, economic, and predominantly agrarian community, Lake decimated nearly all available traditional pueblo summer homes, altered the river, and desecrated places of of New Mexico. Post-construction asseepagefromthedamwaterlogged and 250 acres of bosque, causing rural way of life completely. Though 17-acre drainage system, further from earthen the dam continues.

(Referred to as“the Corps”)

construction of the Cochiti dam under 1965 - 1975 the U.S. Army Corps of Lake, encroaching on 11,000 of the PuebloofCochiti.Acceptingtheirdefeat thePuebloaskedtheCorpstoleaveone burial grounds untouched.The Corps were to remain intact. On the first day of firsttobedynamitedandexcavated.The placewheretheoutletworkscouldviably throughout New Mexico were devastated native lands demolished before their eyes.

Initially, under Public Law 86-645, the reservoir was permitted as part of the Middle Rio Grande project solely for flood and sediment control, not permanent storage, until the idea for the Town of Cochiti Lake was born. Developers loved Cochitibecauseofitscentrallocationwithin the“GoldenTriangle”of Los Alamos, Santa Fe, and Albuquerque.They planned for the reservoirtobecomeavacationspotofhiking trails,campgrounds,andapermanentnonCochiti community of 40,000 people west of the lake. In 1964, Public Law 88-293 was amended to authorize a 50,000 acrefoot“permanent pool for fish and wildlife andrecreationpurposes.”As99-yearmaster leases for the town“with all the amenities of a seven-day weekend” on half of the reservation became realized, the Pueblo found themselves buying leases for their land to limit the size of the non-Native town encroaching on their reservation.

Bookshelf + roof canopy interactions.

Biography chinju no mori.

Park, scriptorium, library, and Chinju no Mori connections.

Library of Biography + Chinju no Mori | Albuquerque, NM

Japanese forestry is grounded in belief that a forest is sacred and spiritual. A Chinju no Mori is a sacred forest surrounding a shrine, signifying beliefs that trees transport spirits back to Earth.

The National Library of Biography is a shrine to the 824,000 lives lost in the U.S. during the Coronavirus pandemic. Home to the biographies of those passed, the library is a Chinju no Mori of books, allowing spirits to tell their stories and connect with those on Earth.

Shinrin yoku is the practice of submitting to your senses and allowing your body to guide you through nature. Listen to the wind through the leaves, smell the plants and soil, be present, and connect with nature.

In the library of unacessible books, people are encouraged to listen to the stories playing within various audio zones and follow the komorebi, sunlight filtering through the leaves and fragmented roof canopy.

When patrons let their senses guide them, they will begin to understand the memorial’s spiritual significance.

Fall 2020

Individual Work

University of New Mexico

Instructor: Karen King

ARCH 401: Architectural Design V

The site for the National Library of Biography, currently a UNM Transportation parking lot with adjacent vacant land is a 24-acre underutilized neglected urban heat island. At the intersection of two of the busiest streets in the city, the lot increases temperatures, hosts invisible pollutants, and serves as a barren and uninviting landscape, limiting accessibility and safety in the surrounding community.

The Chinju no Mori surrounding the National Library of Biography serves as a noise barrier, carbon sink, and verdant haven for humans, animals and spirits alike. With community, accessibility, and empathy in mind, the native forest features a lending library, pedestrian and bicycle access points and paths, and unconditional access to a natural environment.

Meditation

M indfulness is the psychological process of purposely bringing one’s attention to experiences occurring in the present moment without judgment. This style of meditation encourages practice during all times of the day in both public and private.

Using minimum resources to create a space for optimal meditation, the inspiration for this project was rooted in collapsible shelters and primitive construction methods.

The full-scale meditation pod featured a round lashing joint at its apex and hinges on either side of the base allowing the structure to be collapsed and transported.

Mindfulness was a design-build project done in collaboration with classmate Anthony Hernandez. The final product was displayed on campus at The University of New Mexico in the fall of 2019.

Fall 2019

Partner Project

University of New Mexico

Instructor: Alexander Maller

ARCH 301: Architectural Design III

Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino explores culture, time, memory, and death through vivid descriptions of various fictitious cities visited by Marco Polo.

This pavilion is an interpretation of Zora, “a city that no one, having seen it, can forget.” With regulating lines and echoing latticework, “Zora’s secret lies in the way your gaze runs over patterns... as in a musical score where not a note can be altered or displaced.”

Fall 2017

Individual Work University of New Mexico

Instructor: Huang Banh

ARCH 111: Intro to Architectural Graphics

Samantha A. E. Hubbard

B.A. Architecture | UNM SA + P samie.hubbs@gmail.com