19 minute read

Feature

Uberization of energy storage: a potential solution to India’s grid integration challenges

India is currently the 4th largest electricity market in the world. The growth in overall electricity demand in the next two decades is expected to be double that of the overall energy demand. However, there are supply and demand side considerations that challenge the prime objective of a stable electricity grid – matching demand with generation at all points of time.

Advertisement

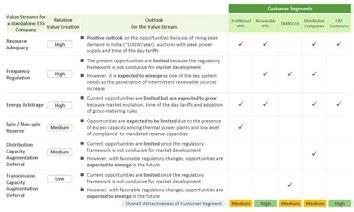

Coupled with other factors like adoption of gross metering rules and increasing electricity intensity of C&I customers, various strategic and operational challenges emerge for players across the value chain: generators, TRANSCOs, DISCOMs and consumers alike. Energy Storage Systems (ESS) hold promise to effectively solve most of the problems through the various value stacks offered by ESS technologies: frequency control, resource adequacy, energy arbitrage, spin / non-spin capacity and T&D capacity augmentation deferral. The applicability of the value stream depends on the location of the ESS in the value chain and the customer segment served. The value streams have varying levels of attractiveness. The total value creation also varies by the customer segment.

Preliminary assessments reveal that renewable IPPs and C&I customers are the most attractive customer segments. The demand from renewable IPPs is being driven primarily through structured RE tenders issued by SECI for solar power with advanced requirements like round-the-clock power and peak power. Due to rapidly falling battery costs, the LCOE of rooftop solar + storage projects are already comparable to retail electricity prices for C&I customers in major industrialised stated like Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Gujarat.

Adoption of gross metering rules and subsequent reduced realization on the excess electricity transferred to the grid is expected to make the case for ESS stronger – prosumers can store the excess electricity produced and use it during peak hours thus avoiding time-of-the-day charges. Electricity intensive sectors like data-centres are also looking to decarbonize their consumption through adoption of ESS. Similarly, establishment of short-term markets like Green Term Ahead Market (GTAM) and Real Time Market (RTM) is expected to boost the demand for ESS from both the customer segments as a platform to take advantage of energy arbitrage.

Though initial investments are being mobilised in setting up ESS projects, customers by and large are still hesitant to commit capital investments. In such a scenario it presents an opportunity for existing and aspiring ESS companies to disrupt the market through innovative business models.

The traditional asset based model involves setting up an ESS project for a particular customer. This leads to a longer payback period because of limited applicability of value streams and limited instances of application for a particular customer. On the other hand, a service led model that uses a tech-enabled aggregated ESS platform provides on-demand services to various customer segments in return for a pre-determined tariff. The aggregation model ensures higher asset utilization and cost recovery for the ESS company. In the aggregator model, the weighted average capital cost of the total system reduces as incremental storage capacities are added at lower costs (due to fall in technology cost). This results in reduction in tariffs for the customers, thus creating a win-win for both the ESS company and its customers.

While the initial focus in India appears to be on the asset – led model, we expect the service-led model to gain traction as the market matures, similar to developed markets such as US and Australia. However, a suitable regulatory framework is necessary to provide adequate certainty to players in this industry and enable development of a market for ancillary services like frequency and voltage control. The DISCOMs have a history of poor cost recovery. Also, the tariff structure is skewed towards variable charges which make recovery of fixed investments on ESS difficult.

Provisions pertaining to recovery of investments on ESS by DISCOMs would be needed to enable market creation. Regulatory provisions that incentivise the installation of ESS through clearly defined norms on power quality would also help in market creation. For example: The US Federal Electricity Regulatory Commission allows a separate tariff structure favoring fast acting resources like battery storage over traditional thermal power plants for frequency control. This has helped in mobilizing investments in ESS by TRANSCOs and DISCOMs.

We believe that a close understanding of customer needs, identification of relevant value streams and a supportive regulatory framework will enable players to develop bespoke business models in India. Learnings from the regulatory framework and business models in international markets can also serve as a useful reference point for stakeholders. Suman Jagdev, Director & Lead – Strategy Consulting GCA Corporation, Mumbai.

As expected, once it did arrive, India’s Basic Customs Duty plan for solar cells and equipment has managed to create just the sort of furore that the government claims it seeks to avoid. After all, for once, this was a decision that was long in coming, with intent having been announced last year itself, followed by enough loud thinking and leaks to ensure the surprise element was all but taken out. Thus, when the ‘decision’ finally came, to implement it from April 1, 2022, issues have been raised on the many missing gaps, instead of the announcement itself.

But first, let's quickly track the route to the announcement of the firm date of April 1, 2022. On that day, 25% BCD on solar cells, and 40% BCD on solar modules, will supposedly start, marking by far the strongest direct push for manufacturing these in India.

At SaurEnergy, we have regularly pointed out that the odds of the BCD being deferred to at least 2022 if not beyond, were always high for two very basic reasons. One, that domestic capacity is simply not enough to meet demand, making high duties counterproductive. Two, even with the support of manufacturing with incentives that work, fresh manufacturing capacities would take at least 18 months or more to come online, making a case for a staggered approach to protection. Beyond these, many pros and cons have been discussed regularly, some of which have become even more relevant now, as we will see.

New Duty Cycle

The new customs duty will replace a 14.5% safeguard duty currently imposed on imports from China and Malaysia. A duty which the ministry feels is “not helpful for domestic manufacturers as they are not willing to put up new plants,” an MNRE representative stated.

The planned duty structure, the government hopes, will finally put the country back on the map as a serious manufacturer of solar equipment, a situation that existed till 2010, besides cutting the high import dependence. Moving forward, the ministry has advised all renewable energy implementing agencies and other stakeholders in the country, to take note of the above trajectory and to include provisions in their bid documents, so that bidders take the trajectory into account while quoting tariffs, in all bids where the last date of bid submission is after April 1, 2022. Put simply, the long notice period before the imposition of BCD as per the above trajectory means that BCD when it starts from Aril 1, will not be considered as change-in-law.

The ministry believes that it had faced a similar problem when safeguard duty was imposed. “This time we do not want to repeat such kind of thing. So, we have proposed to the Government to impose Basic Custom Duty with a future date i.e. April 2022, so that all existing projects can be commissioned before that,” an MNRE representative said.

Planning

In July 2018, the government had imposed a safeguard duty for two years on the import of solar cells from China and Malaysia, which was set to expire on July 29, 2020. A 25% safeguard duty was imposed from July 30, 2018, to July 29, 2019, which was reduced to 20% from July 30, 2019, to January 29, 2020, and at 15% starting January 30, 2020, to July 29, 2020,* (now extended until July 31, 2021)

Through March - July 2020, the Directorate General of Trade Remedies (DGTR), under the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, was conducting a probe on whether to continue with the imposition of safeguard duty on solar photovoltaic (PV) cells following an application made by domestic companies for the same. In its probe, the DGTR had concluded that after a decline in imports in 2018-19 due to the imposition of safeguard duty on “solar cells whether or not assembled in modules or panels”, imports had again increased during April-September 2019 period then the rate of the safeguard duty had reduced on July 30, 2019.

The commerce ministry in the first half of 2020 had proposed imposing a 25% customs duty on solar modules from August 2020, which could be raised to 40% from April 2022. On solar cells, it has proposed a 15% duty, rising to 25% in 2022.

While the success or failure of the first two years remains up for debate, the ground situation clearly pointed to a failure on the

manufacturing side. Local manufacturers clearly believed the SGD to be inadequate. Even as solar bids at auctions continued to go down, primarily based on dropping imported module prices

But with the government and local industry firmly in favour of protecting the local market and protecting the domestic industry from injury from imports, the strong division between module manufacturers and project developers has slowly been waning as more and more developers announce their entry into the manufacturing segment.

However that divide hasn’t completely vanished as Pinaki Bhattacharyya, CEO & MD Amp Energy India, a pure play developer explains “this move will slow down the race towards the 175 GW target by 2022 i.e. next year. Although this removes considerable uncertainty but the rates are too high and will increase the cost of solar power for discoms and consumers alike. This will increase the cost of manufacturing power as well as other industries in India. We understand that the intent of the government is positive and they want to encourage domestic manufacturing but the method should have been different. The government should have provided direct manufacturing subsidies to manufacturers to help them scale up their capacities and this would have been beneficial to the sector.”

Manufacturing in Solar Sector - so far

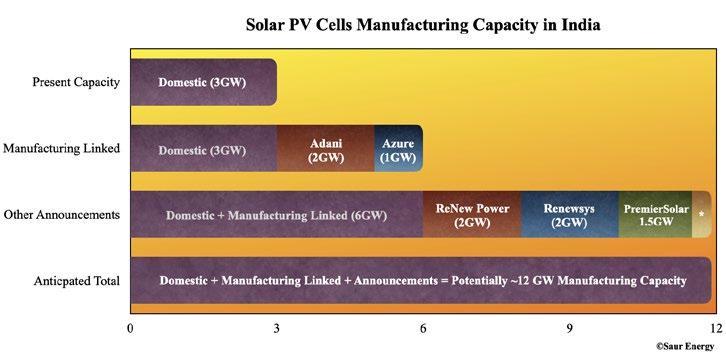

According to data obtained from MNRE, it is common knowledge that domestic manufacturing capacities are limited in India. At present, the manufacturing capacity is only 2.5 gigawatts (GW) for solar cells and 8.8 GW for solar modules, if one goes by MNRE’s own ALMM list. (Approved List of Module Manufacturers). Some industry players have pointed to the ALMM list as final vindication on the numbers around India’s installed capacity. The ministry claims that the demand in the sector is set to go to 30 GW. Even though recent history gives no reason to believe that number with the maximum capacity that has been installed in the country over the last three years (grid-tied utility-scale projects) being 6529.20 MW in 2018-19 against the 11,000 MW target. The number then dropped to 6447.14 MW in 2019-20 against the reduced target of 8500 MW and has further dropped to 4166.28 MW (as of January 31, 2021) for the current fiscal. While COVID-19 provided a fig leaf for 2020, the truth is that targets were going awry well before that, with COVID simply providing the coup de grace that has forced MNRE to go for drastic measures, including BCD, as it turns out.

Thus, going by installed capacity which has remained lower than 9-10 GW per annum, an onlooker might believe that domestic manufacturers are on par with the actual demand of the solar sector in India. However, they do fall behind, by some distance, when the expected demand is considered concerning the elusive target of installing 100 GW solar capacity by December 2022, with just under 39 GW (38.79 GW) installed currently.

And with this huge gap in demand and supply, another key figure that must be considered is the 21 to 22% cost difference between

domestic solar cells and solar modules that are imported specially from China. And with the current duty being under 15%, developers can save roughly 7-8% per module while importing what many believe to be technologically superior products.

Solar modules account for a massive 60% share of any solar project cost. And the numbers above show why developers prefer importing modules instead of procuring them from local manufacturers. A preference that has seen imports accounting for nearly 80-90% of the overall demand in the country, as multiple government initiatives — spanning from 2010 with the Domestic Content Requirement to 2018 with the Safeguard Duty — have more or less been unable to stimulate the domestic manufacturing segment.

Manufacturing in Solar Sector - going forward

However, it seems that the government has finally found the right track to follow if it wants to boost its local manufacturing performance :- The trio of (1) BCD with the recently updated (2) Approved Models & Manufacturers of Solar Photovoltaic Modules (ALMM) list which announced the names of 23 Indian manufacturers whose modules would be eligible for use in government contracts for solar plants, and the (3) Production Linked Incentive (PLI) Scheme with an outlay of Rs 1.956 lakh crore — which was approved in November 2020, to encourage manufacturing in key sectors including 'High-Efficiency Solar PV Modules’ which was assigned Rs 4500 crore. MNRE believes that the “Rs 4500 crore for ‘High-Efficiency Solar PV Modules’ will help bring scale and size in Solar PV manufacturing.”

One firm firmly in favour of the move is Vikram Solar — one of the leading solar module manufacturers and solar solutions providers in the country. Gyanesh Chaudhary, Managing Director at the firm told us that the firm has “BCD implementation will provide the necessary impetus to create a self-sustaining ecosystem for solar equipment manufacturing in India, job-creation and reduce solar imports.”

Another positive stemming from this trio is the new initiatives being taken by Indian project developers in announcing firm action plans for undertaking manufacturing in the country. The trigger in this was the manufacturing-linked tender that was awarded by the Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI) to Adani and Azure Power. The nodal agency awarded 12 GW of solar generation capacity via projects — 8 GW to Adani and 4 GW to Azure — and with it a linked 3 GW pa mandatory manufacturing portfolio which was also shared between the two firms (2 GW for Adani and 1 GW for Azure). This was followed by announcements from ReNew Power which stated that along with chasing the target of 25,000 MW capacity in the next 5 years, it will also be entering the manufacturing sector with plans to initially set up a solar cells plant with a capacity of 2 GW pa.

Vikram Solar, has also signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the state government of Tamil Nadu to set up a 3 GW solar manufacturing facility in the southern state. Interestingly enough, the facility will be involved in the production of solar cells and modules but also solar wafers. A welcome sign of backward integration, in an industry where critical parts of the chain-like wafers and ingots remain almost completely hostage to imports with China dominating 95% of the global market.

The regulated impact of the trio is expected to have a positive impact on the local manufacturing performance, where the government is ready to accept higher project costs and tariffs in lieu of boosting the domestic performance.

Impact and Uncertainty

The biggest impact of this announcement will be first witnessed with the commissioning of a large portfolio of solar power projects in the country in the coming fiscal as developers rush to conclude power purchase agreements (PPAs) and then sign equipment orders before the new implementation date sets in the new duty cycle. This will also be substantiated with the hike in the solar product procurements from the cheaper Chinese manufacturers over the following year. Moving on from project installations to project bidding and tenders, a new analysis by rating agency ICRA has found that despite the imposition of the BCD on solar cells and modules

having an overall positive impact on the domestic equipment manufacturers, in the near term future it will result in an increase in solar tariffs.

According to Girishkumar Kadam, co-group head, ICRA ratings, BCD is expected to result in an increase in the capital cost for a solar power project by 23-24%, which in turn would result in an increase in tariff by about 45-50 paise per unit. “However, the bid tariff trajectory is likely to remain well below Rs 3 per unit and thus, would continue to remain cost-competitive from the off-takers perspective,” he said.

According to Vikram V, sector head, ICRA Ratings, based on an imported module price level of 18 cents per Watt and prevailing rupee-dollar exchange rate, the domestic modules are costlier by 12-15% without the impact of BCD. He believes that the imposition of BCD would bridge this gap and make the modules from a domestic manufacturer competitive against the imported modules. Furthermore, the extent of benefit would be higher for manufacturers having backward integration into cell manufacturing.

However, the agency also believes that there is a need for clarity on a few matters. The most critical of which is the applicability of the customs duty on imports of cells/ modules from manufacturers located in the Special Economic Zones (SEZs), a large portion of the manufacturing units in India are at present located in these regions.

Gyanesh Chaudhary, MD at Vikram Solar, a firm that stands firmly in favour of the new customs duty also said that the firm wants MNRE to “consider exempting BCD levy on manufacturing units located in SEZs. Considering that 43% of solar panel manufacturing units and 63% of solar cell manufacturing units are located in SEZs, imposing BCD on SEZ units will impact the domestic solar manufacturing ecosystem. The imposition of BCD on SEZ units will make them highly uncompetitive resulting in underutilisation of capacities, loss of investment, and jobs. There will be a question mark on the very existence, and survival of module manufacturers in SEZ units.”

Some experts have theorized that with solar costs comfortably below coal-powered generation today, the broader thinking in the government is that a cost increase of Rs 25 to 35 paise per unit, the likely impact of the 40% duty, would be an acceptable price to pay for the drive to Aatmanirbhar Bharat in the power sector. With investments of USD 20 billion per annum expected for meeting the country’s renewable energy requirements for the next decade, it's a view that has some real weight.

What Could Go Wrong?

Industry players have regularly pointed out, that despite the ‘high’ duty structure, there is much that can still go wrong with government plans and expectations now.

Top of the list is the issue of backward integration. Leading Chinabased firms we spoke to point out that Solar Cells and Solar Modules are just a part of the broader solar supply chain. Other components, from polysilicon to silver paste, to EVA and even solar glass are equally concentrated in China.

Global module major Jinko Solar, in a surprising public release on March 18, 2021, placed its view on the future for solar prices, by pointing to the price escalation already seen in polysilicon prices, besides the disruptions seen in the market for EVA, silver paste, and solar glass. Jinko felt the need to announce that it was simply not possible for it, and other "quality" manufacturers to hold prices, or even consider dropping them. Their release adds that “ Silicon for monocrystalline products rose to about 114.2 RMB/kg and the price for multicrystalline products has reached 63.3RMB/kg. Consequently, wafer and cell prices ramped up by 25% over those of last year. The outlook for module prices is also clear, several major players have anonymously adjusted their pricing strategy and confirmed that increases are inevitable which has been witnessed in the latest bids in China.”

In other words, if someone offers modules at the same price as six months ago, or lower, worry about quality. It’s a view that has been endorsed in so many words by other vertically integrated module makers. The next argument is on capacity. Global manufacturers exporting to India point out that far from having the capacity to meet internal demand, the few Indian manufacturers that do make quality solar cells and modules actually prefer to export them! Because, for historical reasons, they have had a strong presence in the US and even European markets. In fact, the Ministry of Commerce itself has shared numbers that confirm that India’s exports of solar cells, with or without module assembly, jumped 157% to Rs 1,330 crore in the first eight months of 2020-21. Exports for the whole of 2018-19 stood at Rs 847 crore and in 2017-18, Rs 913 crore, according to the Ministry of Commerce.

To remove any misgivings about collusion among Chinese majors, these players point out how bids in China itself have trended up in recent weeks, pointing to a scenario of rising prices. What that means is that developers who were planning to take a chance, and the interest cost, to order in bulk by the third quarter of this year (December 2021), may not be able to do so at the scale they wished for, as the low-cost advantage may not be as high as thought. A typical order takes upto 12 weeks or even more sometimes, depending on volumes, to be delivered from China.

An interesting observation that indicates a reason for further tightness in the market comes from another large China player. “Large capacities in China do not mean that those capacities can be requisitioned for Indian orders. Sometimes only a proportion of our plants are BIS certified which can further reduce the window for servicing truly large orders from India, should they materialise,” he adds. This source points out, that Indian developers would need to be careful to place their orders with truly integrated players in this period, as other smaller players are likely to see more price volatility due to material shortages etc, which will lead to possible cancellations, delivery delays and more. Projects won on the assumption of using polycrystalline modules run an even greater risk going forward as those capacities are dwindling fast in China, and buyers risk being left at the mercies of smaller players with suspect quality.

He predicts more pain ahead for projects that are already delayed significantly if they can’t wrap up faster now.

Conclusion

For the government, the BCD announcement tried to meet multiple conditions that it hopes will make it a successful gambit. From enough advance warning, to a level that it believes will drive a significant shift to local manufacturing, at acceptable cost. What it may not have planned for is the tightness in global prices, that puts projects pending completion at serious risk. This pipeline was one of the key reasons for the long lead time to start of the new BCD regime, with the government making it very specifically clear that all projects from the day after the announcement, ie, March 10, 2021, will need to plan for the new regime accordingly. Multiple projects in the implementation pipeline of almost 30 GW stand to be impacted at different levels.