13 minute read

Celebrating Excellence

Meb and Hurley Ryan ‘82 are the proud parents of two recent graduates Hurley ‘17 and Jack ‘19 and have made two gifts to the Invest in Excellence campaign: “There was no question we would support the campaign in its early days when one of the primary goals was a new Upper School STEM building. SCDS has been the key factor in our sons’ success, and we feel an obligation to pay it forward for future students as those before us have so generously done. When news of the Livingston Hall renovation was announced, we knew we could not sit on the sidelines since the Upper School Learning Support program is so near and dear to our hearts. We will always be enthusiastic advocates for SCDS — giving back is easy when you have been given so much!” — Meb Ryan

Classmates from the Country Day class of 1977 came together to make a collective class gift towards a student workspace in Mingledorff Hall. This class is widely recognized for its continued commitment and devotion to the school, and proudly uses the self-professed acronym, BCE: Best Class Ever.

Advertisement

“It is with great pleasure that the Class of 1977 A.D., B.C.E., participates in the rising from the ashes of the Open Classroom Experiment to the wonders of the latest in modern education.”

— Wiley Wasden III on behalf of his classmates

Robbie (Hoffman) ’64 and Eddie Culver ‘62 are part of Country Day’s only four-generation family, currently spanning 1934 to 2029.

“Savannah Country Day School, formerly Pape School, has been a part of our family for four generations, with Robbie’s mother (Electa Falligant Robertson Hoffman) graduating from Pape School in the class of 1934. We know firsthand the value of the Country Day experience and passed it on to our children, Brian, class of ’94, and Kristin, class of ’97. Now Brian and his wife, Kerri, are watching their children, Helen, class of ’26, and Hayes, class of ’29, flourish in the Country Day environment. We always felt that one of the greatest gifts we could give our children was the best education Savannah could offer. Our family is proud to be a part of Mingledorff Hall and proud to be a part of a legacy that will be passed on to future generations…of our family and many others.” — Eddie Culver ‘62

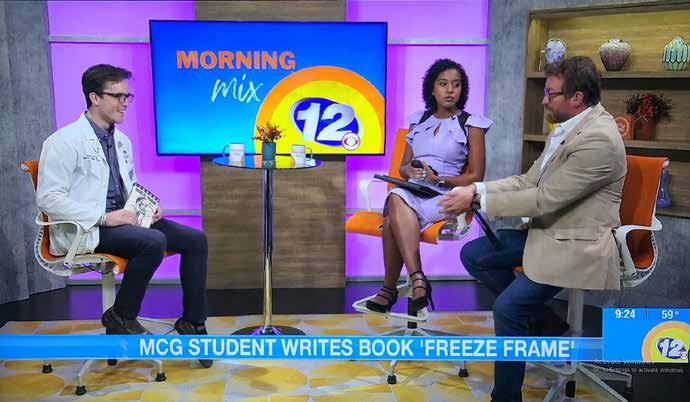

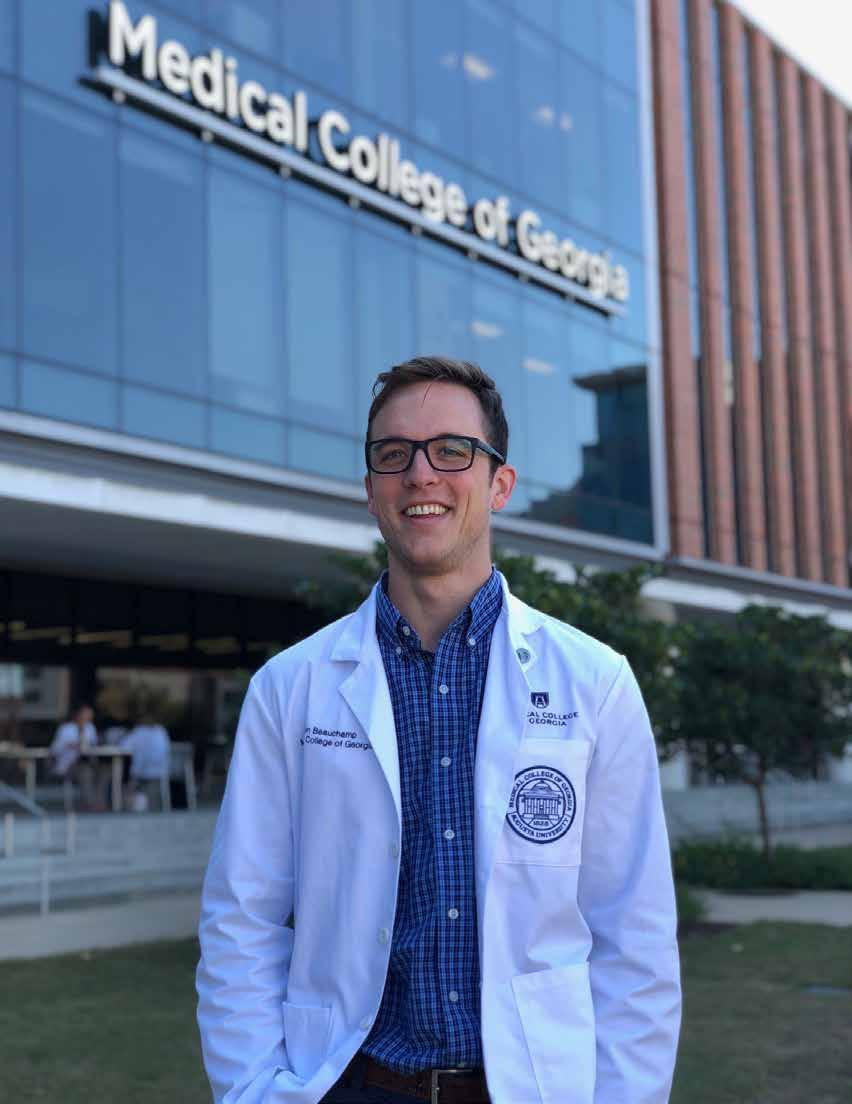

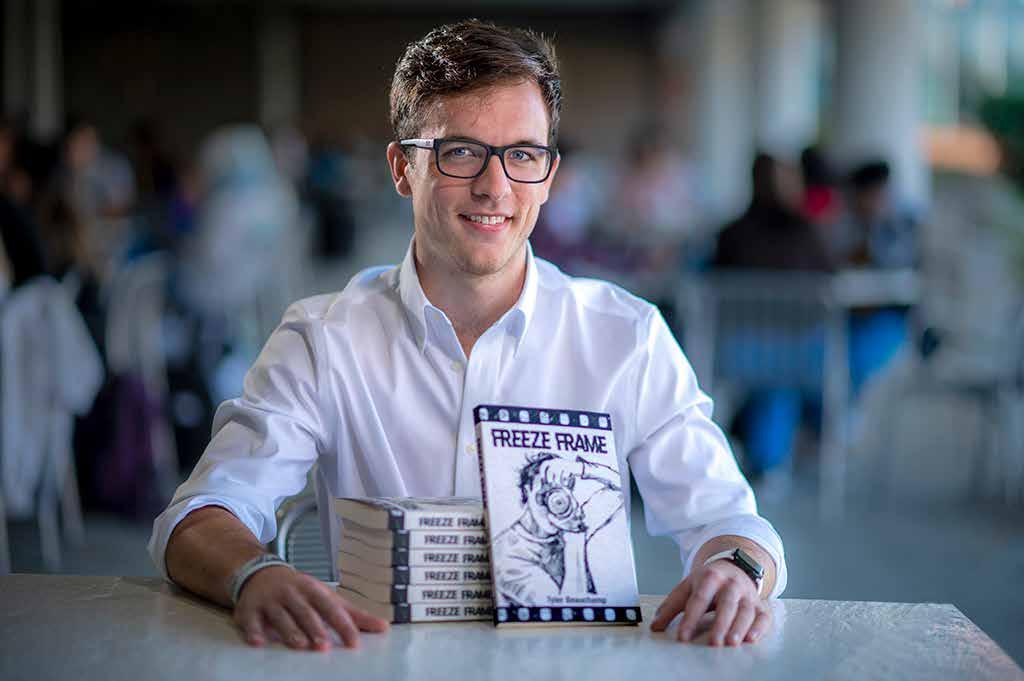

After graduating from Country Day in 2015, Tyler Beauchamp earned a Chemistry degree from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and later went to medical school at the Medical College of Georgia. While in medical school, Tyler worked as a coordinator at the campus mental health clinic and utilized his creative interests of music and writing as an outlet. It was his work at the mental health clinic that inspired him to write his first book, “Freeze Frame,” a captivating story of a high school junior who tries to overcome trauma in his past while changing to a new school. The book is currently an Amazon #1 Best Seller and #1 in Coming of Age Fiction.

Tyler returned to Country Day in the fall to spend time with Upper School students, both in smaller classroom groups and an Upper School assembly in Jelks Auditorium. Students appreciated hearing more about the process of writing and publishing a novel, how he successfully balances medical school with multiple creative explorations, and his push to raise awareness of mental health concerns.

When you spoke at the Upper School assembly, you mentioned that you explored a variety of majors at UNC and volunteered in a health clinic. Why did you decide to pursue medicine?

When I was little, I was actually a patient looking for answers to chronic joint pain. The process took me around research clinics for the better part of my childhood, so I really was exposed to medicine from that side of the curtain. When I got to college, I had absolutely no idea what I wanted to do. I tried everything under the sun (creative writing, business, psychology, athletic training, and more) because I didn’t want to leave college wondering “What if?” It wasn’t until I tried working with physicians and seeing the other side of the curtain that I realized I had found my place. Medicine would allow me to work hands-on with people through their most difficult days and create a lasting impact in their lives. I could also use my experience as a longtime former patient to better empathize with patients and their struggles. It also doesn’t hurt that you get to wear pajamas to work.

During medical school you channeled your creative side with music and writing. Why was that an important outlet for you and do you feel it complements your ability to care for others? Will your writing ability matter to your medical career?

I put a quote in the front of my book from Dead Poet’s Society that loosely says “Medicine, law, business, these are all noble pursuits necessary to sustain life…but art, poetry, love, this is what we stay alive for.” This is pretty much how I live my life. I definitely get asked, “How are you able to do both art and medicine?” and I always say I don’t know how I would do one without the other. When medicine becomes draining, I escape into writing and music and feel energized to keep going. When I’m having a tough time coming up with what to write next, I think about the problems and captivating stories of the many people I’ve met through medicine and I’m inspired to highlight their struggles. If art and medicine have anything in common, it’s that humanity lies at their core. Being a writer makes me feel more human, and the joy it brings me bleeds over to my time with patients. Continuing my passions outside of medicine will only serve to make me a better doctor and provide more personal care to my patients.

The Covid pandemic hit during your second year of medical school. Tell us about how “Freeze Frame” came to be. How did your earlier work at the health clinic help shape your ideas in “Freeze Frame”?

When quarantine started, I was living in a room with no windows. It definitely psyched me out at times, not knowing if it was light or dark, rainy or sunny. The mind can sort of wander in a place like that. I remember having these vivid daydreams after a while, and after one of them, it took me a minute or two to figure out if the daydream had actually happened. That’s when this image appeared of a boy who was constantly jumping in and out of reality. I had spent a lot of time working at a free mental health clinic in medical school, and that paired with my own mental health battles helped shape the boy’s story. Almost instantly, I knew I wanted to tell a story about a vulnerable boy overcoming trauma while highlighting key issues of youth mental illness today (social media, peer pressures, anxiety/depression). In my opinion, children are the most vulnerable members of our society, a society that runs at a sprint driven by social media. Children are surrounded by social pressures very few of us can even fathom. And I really don’t mean to say social media is bad. In fact, when used properly, I think it has the power to be our saving grace. But anything powerful can be destructive. I think sometimes we don’t think about just how much power a child with a phone wields, and neither do they. We don’t just need to teach children how to use these tools responsibly, but there needs to be better guidance behind the tools themselves to protect kids. Like I said, the tools aren’t bad inherently. A hammer isn’t bad. It can build a house. But it can also end a life. So that’s where the antagonist was born to combat these counterculture kids. I thought it would be really fascinating for a group of kids with today’s technology and interests to choose to make a movie in a more classic fashion. Setting their work as a competition against social media platformers just made the story more intriguing. It definitely gets meta at times, with a filmmaker losing his grip on reality and seeing films play out before his eyes. But writing the story from Will’s perspective in that way really allowed me to highlight how everyone lives out their own trauma in a unique way, and hopefully readers will see that. You mentioned that the loneliness of the pandemic and your enforced solitude was very difficult. Isn’t writing, by its nature solitary, also very isolating? It seems you might have gone in a direction where you were somehow in a group.

It’s strange to say, for sure, that in isolation I dove into a more solitary act. What’s probably even stranger to say is that when I’m writing I feel completely surrounded by people. You know when you’re having a conversation with yourself in your own head, and you almost end up arguing both sides of a problem? At the end of it, you feel as if the conversation was real, when it was just you with your own thoughts. That’s sort of how I would write dialogue. After I created the characters, their motivations, their mannerisms and little idiosyncrasies, I would sort of place them all in my head and have them talk to each other as real people. They would rag on each other, laugh with each other, and surprise one another. I never felt like I was intentionally coming up with what they were saying, rather scribing as they went along. I spent so much time with these characters—more than I spent with friends or family even at times— that they were very real to me. I know it sounds crazy, but even though I was still in quarantine, writing was where I didn’t feel alone.

“ANYTHING POWERFUL CAN BE DESTRUCTIVE. I THINK SOMETIMES WE DON’T THINK ABOUT JUST HOW MUCH POWER A CHILD WITH A PHONE WIELDS, AND NEITHER DO THEY.“

“Freeze Frame” is a young adult novel that centers on mental health and recovery from a past trauma. What was the inspiration and why did you feel compelled to tell this story?

The mental health elements of “Freeze Frame” were inspired by my work with the free mental health clinic and my time rotating in pediatrics, but the pandemic as a whole played a major factor. Pretty much everyone I knew was worse for the wear, with stress, anxiety, and depression pervasively spreading. What I really started to notice was how often people were internalizing their worries and trying to numb themselves to their problems. And when it seemed like nothing was going right, it was understandable why people would. It’s easier. I know I did the same. I, like many others, convinced myself that opening up about how I was feeling to my friends and family would only weigh them down; if everyone was doing poorly, I didn’t want to add anything more to anyone’s plate. Ironically, of course, when I learned my friends were doing the same, I wanted nothing more than for them to open up to me so I could help them, so we could weather the storm together. The more isolated we feel, the easier it becomes to do things on our own against our own good. A big message behind “Freeze Frame” is to encourage those struggling to be open and vulnerable, with friends, family, or therapy. We can’t go through life alone, yet the pandemic did everything in its power to make us believe we had to be. I also was very intentional in how the main character, Will, navigates his trauma and recovery in that he finds no easy fix. I didn’t want Will “healed” at the end of the story; I wanted him on the right path. Recovery is a non-linear process. We can take a step forward, and then fall two steps back. But as long as we’re continually trying, making intentional efforts each day to improve and work through our burdens, we’re winning the battle. We collectively need to get better at not only celebrating the small successes others make in their mental health journeys but actively supporting others when they fall a step back.

Harold Evans wrote, “All great writing focuses on the significant details of human experience and in simple, concrete terms.” Do you agree?

Absolutely. We flock to stories because they make us feel something. At the end of the day, that’s the measure of success for art. A good story keeps the reader engaged, a great story consumes its reader and pulls something wonderful out of them. No matter what a story is about, from grounded realism to extreme fantasy, it only works if at its core it connects readers to human experience. The characters we love the most, good or bad, are those whose circumstances we can relate to. Everything else builds from that foundation.

What is next for you on the creative side?

With “Freeze Frame”, I’m currently in discussions with streaming services about a potential series adaptation. Fingers crossed. My next book is the first in a children’s series that is sort of a “Magic Tree House” meets “Medicine.” I have a Young Adult sci-fi trilogy and a more in-depth fantasy trilogy mapped out, but those will come further down the line. I’m in no rush though. Right now, I’m a medical student first, so my priority is finishing my last year and beginning my career in pediatrics. The books will come.

You mentioned starting your career in Pediatrics? Why did you choose that as a specialty?

It’s funny, when I started medical school, pretty much everyone I knew told me I would end up pursuing pediatrics. Of course, me being the stubborn person that I am, I said there was no way and put the idea out of my mind. It wasn’t until my third-year rotations when I was able to really see what it was like day-in, day-out in peds that I realized I had found my place in medicine. So many problems I saw in the hospital ultimately came down to preventable causes. If someone had only started down a different path 10, 20 years ago, they wouldn’t be in the situation they were in now. Working in pediatrics would not only help me fix current problems but hopefully future ones as well. Also, it’s not enough to just say children are the future; they’re the entire solution. Almost every problem in our lives, town, country, and world can be solved by protecting and cultivating the next generation. I can’t think of a better use of my life than to make sure those that come after us are taken care of. On another note, they’re certainly the last source of magic in the world. They just see everything through eyes I wish we all still had. The lows in peds are most definitely difficult, as it is with any field, but I don’t think any other field can beat the highs.

Looking back on your time at SCDS, what lessons resonated with you, from the classroom to the stage to the soccer field?

I think the two greatest lessons I learned from SCDS were: one, every problem has a solution, and two, if something hasn’t been done, be the one to do it. I know specifically in Adam Weber’s physics class, we spent more time breaking down problems to the key components rather than throwing equations we had memorized. And not just physics problems, but ethics, economics, you name it. We learned that every problem we face can be broken down into manageable elements, and when there is no direct solution available, you can create a series of solutions to get to where you want to be. I use those skills nearly every day. SCDS also gave us the freedom to explore our interests outside of the classroom and encouraged us to not settle for what was standard. I know I’ve been told often in medicine to drop writing because it will only distract me from being a better physician. I’ve also been told that if I don’t give 100% of my time to writing, I will never make it as a writer. But what if I feel called to do both? I decided to do what makes me happy, regardless of what was said could or couldn’t be done. I hope that people see that and feel encouraged to pursue their passions regardless of what’s “the norm.”

SAID COULD OR COULDN’T BE DONE. I HOPE THAT PEOPLE SEE THAT AND FEEL ENCOURAGED TO PURSUE THEIR PASSIONS REGARDLESS OF WHAT’S ‘THE NORM’.”

What was the most challenging experience you had while at Country Day?

What about the most memorable moment?

I think the most challenging experience was when I hurt my neck the first football game my freshman year. I had spent middle school playing football, and a lot of my friends were made from those experiences. I was a lifer and spent most of my Friday nights growing up at Hornets’ games hoping one day I would be on the field. My very first game, I injured my neck and medically was forced to give up football for good. In an instant, those young dreams were over and the image of what I expected high school to be was gone. It had been a large part of my identity, and I was completely terrified of what I was supposed to be without it. It took time, but the injury led me to explore new interests I never had let myself experience, much of which were in the arts. Everything certainly happens for a reason, and I wouldn’t change how anything happened. The most memorable experience was probably my ongoing debate about UNC with my college advisor. When we were coming up with schools to look at, she threw it on the list and said “I just see you there.” I told her she was out of her mind and I had zero interest in going there. No one I knew had ever gone there, after all. I had a plan of my own, and I “knew exactly what I was going to do with my life.” With every college visit I went on, she would remind me to go visit UNC and I repeatedly told her I didn’t want to. She eventually broke me down and I visited near the end of my first-semester senior year. I instantly fell in love, and I threw out that careful plan of mine. I’m so thankful she broke through my stubbornness because she led me to the perfect fit and taught me to be open to the unknown.