Manuela Studer-Karlen (ed.)

Manuela Studer-Karlen (ed.)

With the collaboration of Stefanie Agoues-Drabert

Schwabe Verlag

Unless otherwise stated, this publication is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercialNoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) licence.

Any commercial exploitation by others requires the prior consent of the publisher.

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

© 2024 by the authors; editorial matters and compilation © 2024 Manuela Studer-Karlen, published by Schwabe Verlag Basel, Schwabe Verlagsgruppe AG, Basel, Schweiz

Cover illustration: The Henry Barber Trust, The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham

Proofreading: Katherine Bird, Berlin; Séverine Nasel, Geneva

Cover: icona basel gmbh, Basel

Typesetting: Claudia Wild, Konstanz

Print: Hubert & Co., Göttingen

Printed in Germany

ISBN Print 978-3-7965-5187-1

ISBN e-Book (PDF) 978-3-7965-5188-8

DOI 10.24894/978-3-7965-5188-8

The e-Book has identical page numbers to the print edition (first printing) and supports full-text search. Furthermore, the table of contents is linked to the headings.

rights@schwabe.ch www.schwabe.ch Published with the support of the

Acknowledgements

1. Paul Williamson: Introduction

2. Maud Brochard: Les ivoires profanes parisiens du XIVe siècle. Artisanat du luxe et objets du quotidien 33

3. Michele Tomasi: La diffusion des ivoires gothiques profanes dans la première moitié du XIVe siècle. Géographie, société, genre, entre œuvres et documents 57

4. Svea Janzen: Notes From the Past. Ivory Writing Tablets and Their Users 75

5. Benedetta Chiesi: Broder l’ivoire. Les coffrets profanes ajourés de la fin du XIVe siècle .

6. Lina Roy: Des alter ego de plâtre. Les moulages d’ivoires gothiques, miroir des crises intellectuelles à Lyon du XIXe siècle à nos jours .

7. Sarah M. Guérin: Notes on a Scandal. Secular Ivories and their Social Contexts

8. Lisa Elena Schmid: Play the Game. How Games on Gothic Ivories illustrate Medieval Society

9. Manuela Studer-Karlen: Les valves de miroir sculptées sur ivoire et la clientèle féminine

10. Vera Henkelmann: Between Suffering through and Fortune of Courtly Love. Falconry Depictions on Late Medieval Ivory Mirror Cases and the Resilience of Courtly Lovers

11. Katherine Rush: Christian Conscience in Crisis. Visualising Morality and Immorality on Gothic Ivory Caskets

12. Alexandra Gajewski: Love among the Crenellations. Amorous Couples in Images of the Castle of Love in Ivory

13. Christina Normore: Sieges in Ivory and Parchment

14. Paula Mae Carns: A Royal Affair. A Rare Depiction of Tristan and Isolde on a Medieval Luxury Object

15. Elżbieta Musialik: Between Nostalgia and Reality. Chivalric Ideals and their Depiction during the Reign of the Last Capetians. The Visual Narration of the Coffrets Composites Group

In October 2022, the conference “Gothic Ivories between Luxury and Crisis” was held at the University of Bern as part of the research project “Love and War on Gothic Ivories”, sponsored by the Swiss National Science Foundation. The event could not have been realized without the tireless commitment and organizational support of my team members Lisa Schmid and Amélie Joller, to whom I express my warmest appreciation. Furthermore, I wish to thank Laura Hutter and Christopher Kilchenmann for their valuable assistance during the course of the conference.

As reflected in the present publication, the papers and discussions centred on the ambivalent phenomenon that, despite a series of social, climate, military, and pandemic crises, ivory carvings as luxury goods flourished in the XIIIth and especially in the XIVth century. This apparent contradiction raises questions about the value and significance of these objects in elite society.

In terms of defining, in a general sense, what “crisis” means for the period under consideration – leaving a more detailed and refined historical contextualization to the individual case studies – I would firstly note that the XIIIth and XIVth centuries were marked by a variety of natural disasters. These included a serious deterioration in the climate, known in Europe as the “Little Ice Age”, as well as several major waves of plague, with a concentration in the 1340s–50s. This historical moment was additionally characterized by military conflicts – chief among them the Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453) – and by the political changes that accompanied them. Most regions of late medieval Europe were severely affected by these and other crises, spurring a drastic decline in population and thus having far-reaching implications for Europe’s social and economic order.

Meanwhile, from the middle of the XIIIth century to the end of the XIVth, a cultural explosion in the use of ivory occurred in the Kingdom of France. Ivory’s association with luxury stems, on the one hand, from its preciousness as a raw material, which also involved its long-distance transport to Europe; and, on the other hand, from the high quality of the carvings we find on the objects. The industry was predominantly, though not exclusively, centred in northern France and especially Paris. All types of objects – whether those with religious or secular uses – were made from ivory, and the preserved examples demonstrate great variety.

The secular iconography can be found in ivory carvings on a large number of surviving household items – such as boxes, writing tablets, combs, and mirror cases. Whether scenes of courtship, motifs around the God of Love, or other imagery drawn from contemporary romances, the depictions reflect – albeit in an idealized manner – the lives, tastes, and literary knowledge of the elite. Analysis of these representations thus offers insight into the interests of courtly owners as well as into related social structures. This volume asks how the everyday

observation and perception of these images shaped the owners’ orientation to the crises of their moment.

Against this backdrop, the volume’s contributors engage with the concept of “crisis” from various points of view. In particular, they seek to resituate the reception of such objects within the contexts of politics, warfare, and the machinations of court. Particular attention is also paid to questions around gender. By recontextualizing these luxury objects and tracing their respective biographies, the book offers compelling new perspectives on Gothic ivories. For certain objects, this necessitates challenging long-held academic assumptions.

A practical note is required to adequately frame this publication. Recent research has benefitted enormously from the Gothic Ivories Project, an online database launched by the Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London. Indeed, some of the contributors to this volume use this resource to identify and compare relevant objects. However, because the database has not been updated since 2015, it must be noted that it no longer reflects the current state of research. For this reason, each essay must undertake a recounting of the corpus at hand as part of its re-evaluation of the ivories.

This publication has been crucially shaped by the comments and corrections of the peer reviewers, whom I would like to thank most sincerely. My gratitude goes also to the Schwabe Verlag, and above all to Arlette Neumann-Hartmann and Ruth Vachek for accepting the book and for their consistently energetic collaboration. This volume would not have been possible without the committed participation of the contributors. I extend my warmest thanks to them all. Special thanks go to Juliana Maria Studer who was responsible for drafting the final index. My collaborator Stefanie Agoues-Drabert provided enduring support for this publication, and I wish to thank her for her commitment and great work. It is an immense honour and pleasure that Paul Williamson has taken on the task of writing the introduction, and I am very grateful to him for doing so.

Finally, I express my gratitude to the Swiss National Science Foundation for its generous financial support for this publication.

Manuela Studer-Karlen

Paul Williamson

It is both heartening and a cause for celebration that the study of Gothic ivory carvings remains in such a rude state of health well into the present century; indeed, by coincidence, these conference proceedings mark the centenary of the foundational publication of “Les Ivoires gothiques français” by the father of the subject, Raymond Koechlin. In the last twenty years, Gothic ivories have been at the centre of medieval studies, being included in many international exhibitions, the subject of scholarly articles of wide-ranging approaches, and with several new museum catalogues and an important recent book by Sarah M. Guérin being dedicated to them. Perhaps the major stimulus to this thriving state of affairs has been the creation of the online database of Gothic ivories, set up under the aegis of the Courtauld Institute of Art in London and launched in 2010, and its enduring importance is evident in the number of references to it found in the papers of the present publication.1 Gothic ivories have also been the subject of colloquia, covering both the religious and secular outputs of the ivory-carvers’ art, which have helped to address questions ranging across dating and localisation, patrons and markets, and even authenticity. The 2022 Bern conference, “Gothic Ivories between Luxury and Crisis”, chose to concentrate on those most characteristic products of the secular market, the caskets, mirror backs and writing tablets, with a brief to ground them in the society in which they were created.

The study of these pieces is far from standing still, as the papers will show. In addition to the different methodologies now being applied to their interpretation, there is also – somewhat surprisingly – the continuing emergence of previously unknown ivory carvings, providing new evidence to ongoing discussions. Such was the case with the appearance of the magnificent complete mirror back with the scenes of the Fountain of Youth and the Storming of the Castle of Love, which entered the Wyvern Collection in London in 2018, and the enigmatic and idiosyncratic casket – now known as the Baird Casket after its post-medieval owners – that appeared at auction as recently as 2021.2

Many of the objects at the heart of the conference papers exemplify the courtly interests of the late XIIIth- and XIVth-century aristocracy and the upper gentry, illustrating the intellectual and moral aspirations of their original owners and their circles, and casting light

1 Yvard (2014) and www.gothicivories.courtauld.ac.uk. Although still accessible, the website has not been added to for several years, and it is the hope that the database will be revived in the future.

2 Williamson (2019), 150–153, no. 73; the Baird Casket was sold at Lyon and Turnbull, Edinburgh, 20 May 2021, lot 493, and is discussed by Elżbieta Musialik in this volume. Notwithstanding the excellent points raised in Musialik’s essay and in Musialik (2022), it appears to stand apart from the composite casket group, and may not be Parisian.

on medieval notions of love and good – and also not so good – behaviour. They are deluxe objects, which would have been within reach of only a small percentage of the population, but the images carved on them – Arthurian, classical and contemporary – were ones that by the middle of the XIVth century were also widely disseminated in wall paintings, manuscript illuminations, textiles and sculpture, on a large and small scale, in both the public and private realms. They are beautiful objects in and of themselves, but can only be fully understood if set within their social and cultural context, and the scenes on them properly explained. The purchasers and the people to whom the ivories were given – if indeed they were gifts – would have been familiar with the stories told on the caskets’ sides and the mirror backs’ surfaces, and been well aware that they carried relevant lessons, both admonitory and light-hearted, in connection with love and the decorum that was associated with it.

At the time the caskets and mirror backs were created, elephant ivory had been prized in Europe as a material for carving for over a thousand years.3 During the course of the XIIIth century, however, the scale of the industry took a quantum leap, so that by 1300 ivory carvings were being produced in unprecedented numbers. This had to do with the recently established trade routes which allowed the transportation and exchange of goods, including ivory, from Africa, from the early XIIIth century onwards;4 on the back of this increased availability of the raw material, new markets for ivory objects emerged. The first Gothic workshops continued the provision of religious, devotional sculptures, most notably the Virgin and Child statuettes, the Crucifix figures, the diptychs and the triptychs so characteristic of the “Age of the Cathedrals”.5 But the emergence of a growing haute bourgeoisie, the wealthy merchants and others in the social class just below the royal court and its associated aristocracy of barons, ladies and knights, ensured that the ivory carvers were also employed to provide objects for everyday, secular, use in their patrons’ palaces and households. The numerous surviving ivory caskets, mirror cases, combs, writing tablets and gravoirs are testament to this development and, as we shall see in several of the papers published here, inventories and wills provide us with further evidence of ownership and the use of secular ivories.

By the beginning of the XIVth century, the centre of the industry was undoubtedly Paris. The workshops were clearly established during the time of the great artistic efflorescence under King Louis IX (r. 1226–1270), when guild regulations were drawn up and working practices codified.6 There was a homogeneity of style across the different media, linking the ivory carvings with contemporary manuscript illuminations, goldsmiths’ works and larger sculptures in stone and wood; and, likewise, there is no reason to doubt that the ivory workshops produced both religious and secular carvings alongside one another. This is self-evident

3 The accessible and wide-ranging survey of Gaborit-Chopin (1978) remains a classic introduction to medieval ivory carvings.

4 The pioneering work on the ivory trade routes by Sarah M. Guérin, covered in a number of recent articles, has now been summarised in Guérin (2022).

5 Even a century after its publication, the magisterial monograph of Raymond Koechlin (Koechlin 1924) continues to be central to any study of French Gothic ivories. The approach to the material has been revised and adjusted considerably, however, most significantly in Barnet (1997) and Guérin (2022), and any student of Gothic ivories should also now consult the richly illustrated digital catalogue of the Courtauld Gothic Ivories Project.

6 Guérin (2022), 49–60.

when comparing the mirror backs with certain devotional diptychs, for instance; and ivory caskets that illustrated either the lives of the saints or the romance legends must have been carved in the same workshops.7

The papers published in these conference proceedings will be seen to cover, with originality and authority, several aspects central to our understanding of the subject of Gothic secular ivory carvings, ranging from case studies of particular pieces or groups to broader analyses of ownership and use. As a preliminary to these valuable contributions it is worth introducing one of the lesser-known ivory caskets as an exemplar, providing as it does a foundation – or sample – for the extrapolations that follow.

The casket in the Barber Institute of Fine Arts at the University of Birmingham is one of eight surviving ivory caskets that are now commonly known as composite caskets. The other seven are in the Victoria and Albert Museum and British Museum in London, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, the Museo Nazionale del Bargello in Florence, the treasury of Cracow Cathedral, and the Musée de Cluny in Paris;8 and there are also a good number of detached reliefs which must have come from similar caskets, such as a lid from Liverpool and a back panel now mounted on a book-cover in the British Library (Fig. 1.16).9 The title “composite caskets”, coined by Raymond Koechlin, refers to the fact that the scenes on the caskets are drawn from a variety of sources rather than showing a single narrative – a mixture that has aptly been described as a “compilation” (following the medieval practice of compilatio) in a seminal article by Paula Mae Carns.10 Although the eight caskets are of a similar style, give or take nuances of carving and slight variations of quality, and are likely to be the products of a workshop in Paris, probably in the years around 1310–1330, no two are exactly alike in their choice of scenes.11

We should start with the lid, and it is of interest to note that the Barber Casket here differs significantly from the others (Fig. 1.1).

7 See, for instance, Williamson/Davies (2014), vol. 1, 483, nos. 168–169 (Glyn Davies); this overlap is also discussed in Gaborit-Chopin (2011), 171–175.

8 Koechlin (1924), 449–455, nos. 1281–1287. More recent extended discussions of the caskets are to be found by Glyn Davies in Williamson/Davies (2014), vol. 2, 657–662, no. 227 (V&A Casket); Barnet (1997), 245–248, no. 64, Baltimore (Richard H. Randall); Ciseri (2018), 282–286, no. VIII.39 (Benedetta Chiesi); Morrison/Hedeman (2010), 281–286, nos. 55, 56, New York and Musée de Cluny (Élisabeth Antoine). The socalled “Gort Casket” in the Winnipeg Art Gallery (inv. no. G-73-60) is not included here as it differs markedly from the others, both in iconography and style: see Ross (1948); Bugslag (2007); Carns (2011). I prefer to put to one side the newly-discovered Baird Casket (see my second footnote).

9 Gibson (1994), 96–98, no. 41.

10 Koechlin (1924), vol. 1, 484–508; Carns (2005).

11 That in the Metropolitan Museum is closest to the Barber Casket, so the useful and convenient discussion of the various scenes on that casket by Paula Mae Carns (2005) are recommended for an elucidation of the Barber Casket. One workshop may have been responsible for all the composite caskets, but the carving was presumably the work of different hands over two decades.

Fig. 1.1: Ivory casket with romance scenes, lid, French (Paris), c. 1310–1330. Birmingham, Barber Institute of Fine Arts, inv. no. 39.26 © The Henry Barber Trust, The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham.

Although divided, like all of the casket lids, into four sections by the position of the uncarved strips and the metal mounts set above them, it is given over entirely to the joust, whereas the others mix the central scene of two mounted knights fighting with lateral images of the Assault on the Castle of Love.12 In those cases, the apposite comments to be found in Alexandra Gajewski’s and Christina Normore’s papers are especially relevant. The two knights here, riding fully caparisoned horses, are shown with helms and shields and armed with special jousting spears with coronel tips.13 The festive atmosphere of the joust is emphasised by the trumpeters perched in the trees to the sides, and above, the assembled spectators, including a crowned queen, watch the sport from an arcaded terrace with a trellised balustrade. At the sides, the respective knights, kneeling and in an attitude of prayer, are shown being armed by their ladies, who lower the helms onto the knights’ heads, an action akin to the more often-seen lady crowning her lover with a chaplet, which regularly appears on ivory mirror backs and combs.

The lid of the casket, rather than illustrating a particular story from medieval romance or classical legend, as is the case with the other scenes on its body, appears to be instead a generic display of chivalric prowess; and the supporting scenes at the side might be interpreted, in the words of Michael Camille in connection with a coeval enamel pendant case, as showing the ladies “bestowing the knight with his masculinity” (Fig. 1.2).14

12 Two detached lids, in Hannover and Ravenna, have a similar arrangement to the Barber lid: Koechlin (1924), vol. 1, 455–456, 458–459, nos. 1289, 1296; Martini and Rizzardi (1990), 87–89, no. 18.

13 For this feature see Capwell (2018), 26–27.

14 Camille (1998), 89.

Fig. 1.2: Enamel pendant case, English, c. 1320–1335. London, Victoria and Albert Museum, inv. no. 218-1874 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

This raises the possibility that the caskets could be given to both men and women, probably celebrating a wedding, and thus questioning the assumption that in every case they were intended solely for female consumption.15 All the composite caskets include a joust on the lid and it is surely relevant here that the tournament was by the XIVth century commonplace as an important element at the marriages of the upper tiers of society.16

The four panels on the front of the casket (Fig. 1.3) are dedicated to two separate pairs of images: the two panels on the left of the lock-plate illustrate the story of Aristotle, Alexander and Phyllis, drawn from the popular “Lai d’Aristote of Henri d’Andeli”, those on the right the tragedy of Pyramus and Thisbe, first told in Book IV of Ovid’s “Metamorphoses”.17

At the far left, the old and bearded Aristotle chastises the young Alexander the Great, who was smitten with the maiden Phyllis (also called Campaspe); Aristotle warns Alexander off the girl, admonishing him that he is being distracted from his studies. When Phyllis hears of this she determines to teach Aristotle a lesson of her own, and sets out to humiliate him. Aristotle quickly falls prey to her charms, and allows himself to be ridden like a horse around the garden; this is the second scene, which includes Alexander and two companions above,

15 See the germane comments of Michele Tomasi in his paper, and below for discussion of ownership. I f given as a wedding present to the married couple, the male/female dichotomy would be irrelevant.

16 Barber (2000), 218–219.

17 Carns (2005), 71–73.

1.3: Ivory casket with romance scenes, front, French (Paris), c. 1310–1330. Birmingham, Barber Institute of Fine Arts, inv. no. 39.26 © The Henry Barber Trust, The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham.

Fig. 1.4: Copper alloy aquamanile with Aristotle and Phyllis, South Netherlandish, late XIVth century. New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Robert Lehman Collection, inv. no. 1975.1.1416 © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

who witness the older man’s foolish behaviour. The image of Aristotle being ridden by Phyllis quickly became one of the most popular of the XIVth and XVth centuries, and its representation of the “woman on top”, demonstrating the power of women, was particularly appealing to the makers and consumers of single objects, such as on a gravoir in the Victoria and Albert Museum, and in a particularly striking later aquamanile now in the Lehman Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Fig. 1.4).18

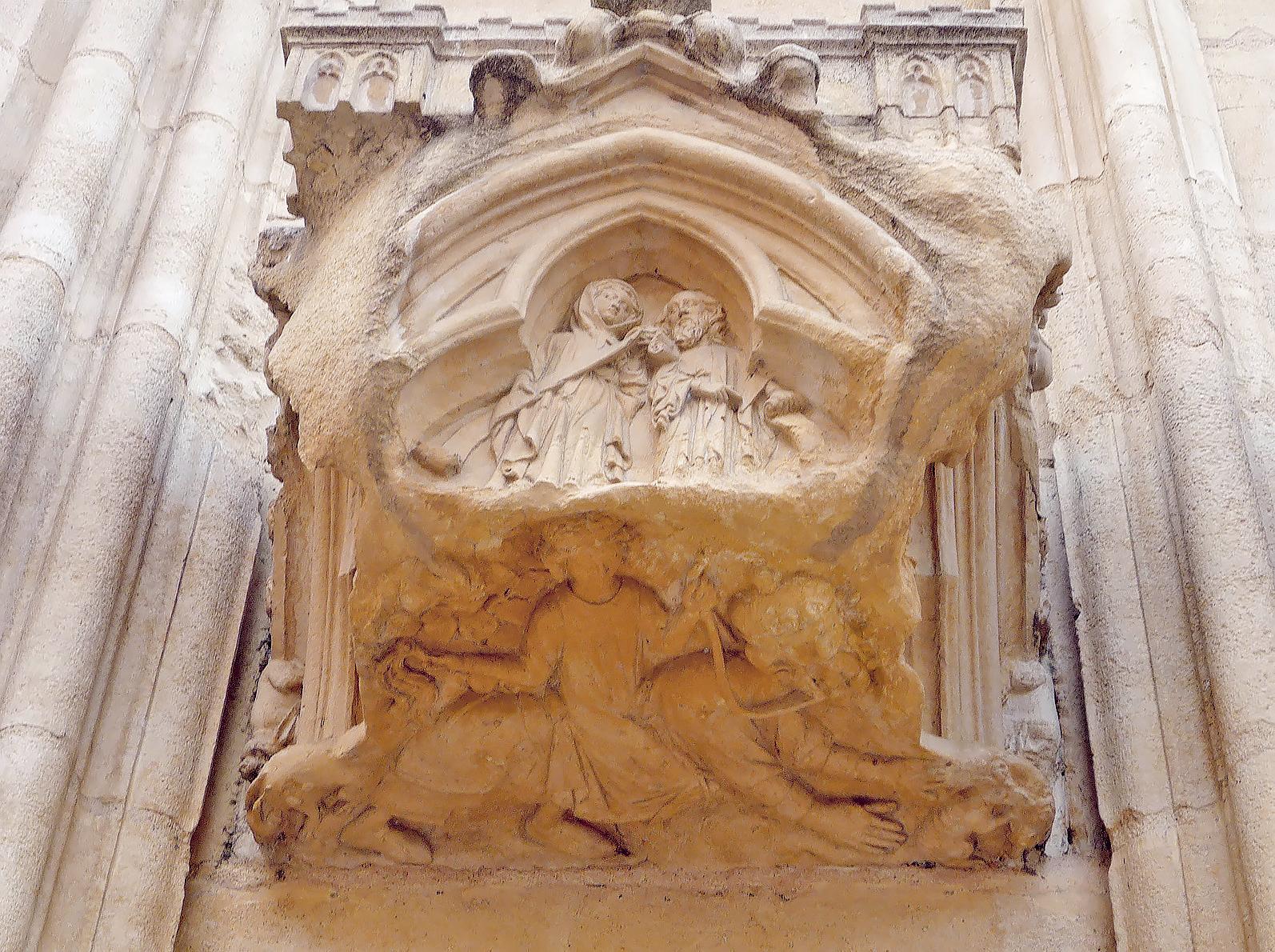

Its popularity was not confined to secular, private settings, however, and the scene even appears on the underside of a console on the west façade of Lyon Cathedral, a sculpture roughly contemporary with the Barber Casket (Fig. 1.5).

The moral here is that love can vanquish reason, and the second pairing of scenes on the casket, on the right, repeats this message but in a very different way. These two panels illustrate the doomed love affair of Pyramus and Thisbe: in the first scene, Thisbe – having dangerously gone down to the woods at night to meet Pyramus – has been frightened by the approach of a lion and climbs a tree to keep a safe distance (a visual solution different from the texts, where she either hides in a cave or behind a tree), but not before dropping her veil on the ground.19 The lion, drenched in blood from hunting, stops to drink from the foun-

18 Williamson/Davies (2014), vol. 2, 636–637, no. 220; Bleyerveld (2005); L’Estrange (2008), 85–86.

19 Innes (1955), 95–98; Carns (2005), 72.

tain; but before leaving it comes across Thisbe’s garment and tears it to pieces, covering it with blood. When Pyramus arrives at the fountain a little later he is horrified to discover the bloody shreds of the veil, and assumes that Thisbe has been killed by a wild beast. Full of guilt for suggesting the risky nocturnal meeting and consumed with grief he draws his sword and drives it though his body. The second scene illustrates the point in the story where Thisbe has climbed down out of the tree and, coming across the dying Pyramus, throws herself against him and impales herself on his sword.

It has been pointed out that the two pairs of scenes are antonymous, that they contrast with one another while offering the same meaning. While the story of Aristotle and Phyllis is to do with foolish, lustful and one-sided senile infatuation, that of Pyramus and Thisbe illustrates the power of a young, innocent, pure and mutual affection. As Paula Mae Carns has shown, the juxtaposed but opposing nature of the stories has been strengthened by the visual construction of the two central scenes, so that the figure of Aristotle, on all fours, is shown back to back with the crouching lion in the awkward spaces below the lock plate.20 While the composite caskets in New York, Cracow and Florence have identical front panels to the Barber Casket, the two caskets in the Victoria and Albert and British Museums and that in Baltimore show instead of the story of Pyramus and Thisbe another pair of images: the theme of the Fountain of Youth. Here the hopeful vanity of the old and stooped protagonists on the right (one of whom carries an old lady on his back in a clear reference to the younger Phyllis on the adjoining panel) is set alongside the aged Aristotle as an illustration of the misguided but enduring desire for eternal youth.21

Moving round the casket, to the right, the viewer next comes to a single scene on the first short side, showing a mounted knight spearing a wild man; between the two figures is a young maiden, raising her arms in surprised terror (Fig. 1.6).

Of the eight composite caskets, the Barber Casket is the only one to dedicate a whole panel to this scene, and the Victoria and Albert and British Museum caskets do not include it at all, preferring in its place to show a scene often interpreted as Galahad and the Hermit at the gate of the Castle of the Maidens.22 Some authorities have identified the knight as the aged Enyas, who does rescue a young damsel from a wild man’s clutches, but there is more to that particular story than is illustrated here on the casket.23 The knight may indeed have called the Enyas story to mind for the medieval viewer, but such generic images of chivalry were commonplace in the XIVth century, celebrating the virtues of gallantry and male power, and in this case pointing to the victory of virtue over lust, the latter personified by the wild man. A rare complete ivory mirror case in the Wyvern Collection shows a more extended narrative, with a knight in combat with a wild man on one disc and the latter’s capture and

20 Carns (2005), 73.

21 The eighth composite casket, in the Musée de Cluny in Paris, shows the Wisdom of Solomon on the right, contrasting this figure with Aristotle on the left; see the illuminating discussion of this by Élisabeth Antoine in Morrison and Hedeman (2010), 284–286, no. 56.

22 Carns (2005), 80–81. The other composite caskets all either combine the knight attacking the wild man, on the left, with the “Galahad” scene on the right (New York, Cracow, Florence, Paris), or just show the latter as a single scene (Baltimore).

23 For the Enyas legend see Husband (1980), 69–71, following Loomis (1917a and 1917b). More circumspect readings are offered by McLaren Young (1947), 20, and Carns (2005), 79–80, and see also the analysis of the Wild Man scenes in the paper of Katherine Rush in this volume.

the meeting of the knight and a lady on the other; and a further example of the single scene is furnished by the splendid translucent enamel plaque on the other side of the little pendant case in the Victoria and Albert Museum that was mentioned earlier in connection with the scene of the arming of a knight (Fig. 1.7).24

Turning to the back of the casket, the oblong relief there continues the theme of chivalric gallantry, but in this case more clearly rooted in two well-known romances (Fig. 1.8).

The four panels illustrate what at first sight appears to be a single narrative, showing a knight fighting a lion, crossing a sword bridge, and lying on a curious bed (both the second and third scenes show swords or spears descending from above), while the final image is of three maidens looking on. In fact, this narrative combines two celebrated stories dedicated to Gawain and Lancelot: Chrétien de Troyes’ “Le Conte de Graal (Perceval)” and “Le Chevalier de la Charrette (Lancelot)”.25 The fact that the single scene demonstrably to do with

24 Williamson (2019), 208–209, no. 103; Alexander and Binski (1987), 458–459, no. 581 (entry by Marian Campbell).

25 Loomis/Loomis (1938), 70–72; Carns (2005), 76–79. The relevant passages are transcribed in Kibler (1991), 244–246, 475–477.

Fig. 1.7: Enamel pendant case; English, c. 1320–1335. London, Victoria and Albert Museum, inv. no. 218-1874 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

1.8: Ivory casket with romance scenes, back, French (Paris), c. 1310–1330. Birmingham, Barber Institute of Fine Arts, inv. no. 39.26 © The Henry Barber Trust, The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham.

Lancelot, the crossing of the sword bridge in search of Queen Guinevere, is sandwiched between the scenes connected with Gawain – the killing of the lion and Gawain’s ordeal on the perilous bed, where he is assailed by arrows and crossbow bolts and then welcomed by the damsels of the castle – has attracted much scholarly discussion about the use of literary sources and their visual presentation and is also further analysed by Katherine Rush in the present volume.26 It may be, as Loomis suggested, that the carvers who translated the two stories on to ivory did not have access to the written sources, which would explain why the scene of Lancelot crossing the sword bridge includes the shower of swords and arrow bolts, when these only occurred in the story of Gawain on the perilous bed; likewise, in some cases Gawain is not protected by a shield while on the bed (as on the Barber Casket), an essential prop for his safety in the full textual source. On the other hand, it cannot be entirely dismissed that the carvers of the panels might have juxtaposed the stories of Lancelot and Gawain in the two central scenes for the sake of visual harmony, just as they did with Aristotle and the lion on the front of the casket. Alternatively, it may be that the knight fighting the lion in the first panel is indeed intended to represent Lancelot, not Gawain, as McLaren Young proposed.27

All of the surviving composite caskets illustrate the same four scenes on the back, in the same order, but several other similar ivory boxes – now broken up – included a single scene of Gawain on the perilous bed on one of the shorter end panels.28 The existence of these single panels reinforces a reading of the caskets as compendia of chivalric deeds, sometimes isolated, brought together for the delectation of the owner.

The left end of the casket is, like the front, dedicated to two contrasting episodes, connected by their moral message and pictorial composition (Fig. 1.9).

On the left are the young adulterous lovers Tristan and Isolde, seated to each side of a fountain. They have come to the woods for a furtive meeting, but King Mark, the husband of Isolde, has been told of their assignation and is perched in the tree above their heads. Fortunately for the young couple, Tristan sees the reflection of the king in the water of the fountain, and he is here shown pointing it out to Isolde. Instead of love-making, they instead converse in the most innocent manner and escape the king’s wrath.29

The lovers’ tryst is contrasted here with the scene on the right, which pictorially almost blends in with the first. It shows a virginal maiden on the far right, balancing the morally lax Isolde opposite; Isolde holds a small pet dog, an erotically-charged accoutrement to courtship, while the chaste damsel has attracted a unicorn, as only virgins can.30 She strokes its horn and holds a chaplet in her right hand, as if to crown a lover.31 Echoing the figure of King Mark at the left, a hunter crouches in a tree above the unicorn and spears the poor beast.

26 See, for instance Bruckner (1995), 66–68, and G. Davies in Williamson/Davies (2014), vol. 2, 658–659; see also Meuwese (2005) and Manuwald (2015) for wider discussions of the relation between texts and the ivories.

27 McLaren Young (1947), 20–21; see also Carns (2005), 76, and Antoine-König (2017), 154–155.

28 Antoine-König (2017).

29 See the full account in Loomis/Loomis (1938), 65–69, and Carns (2005), 73–75.

30 For the symbolism of the lapdog see Camille (1998), 102.

31 Carns (2005), 75–76, interprets this as a mirror, but its appearance most closely resembles other chaplets on ivory carvings; in this connection see also Camille (1998), 47–49, 55.

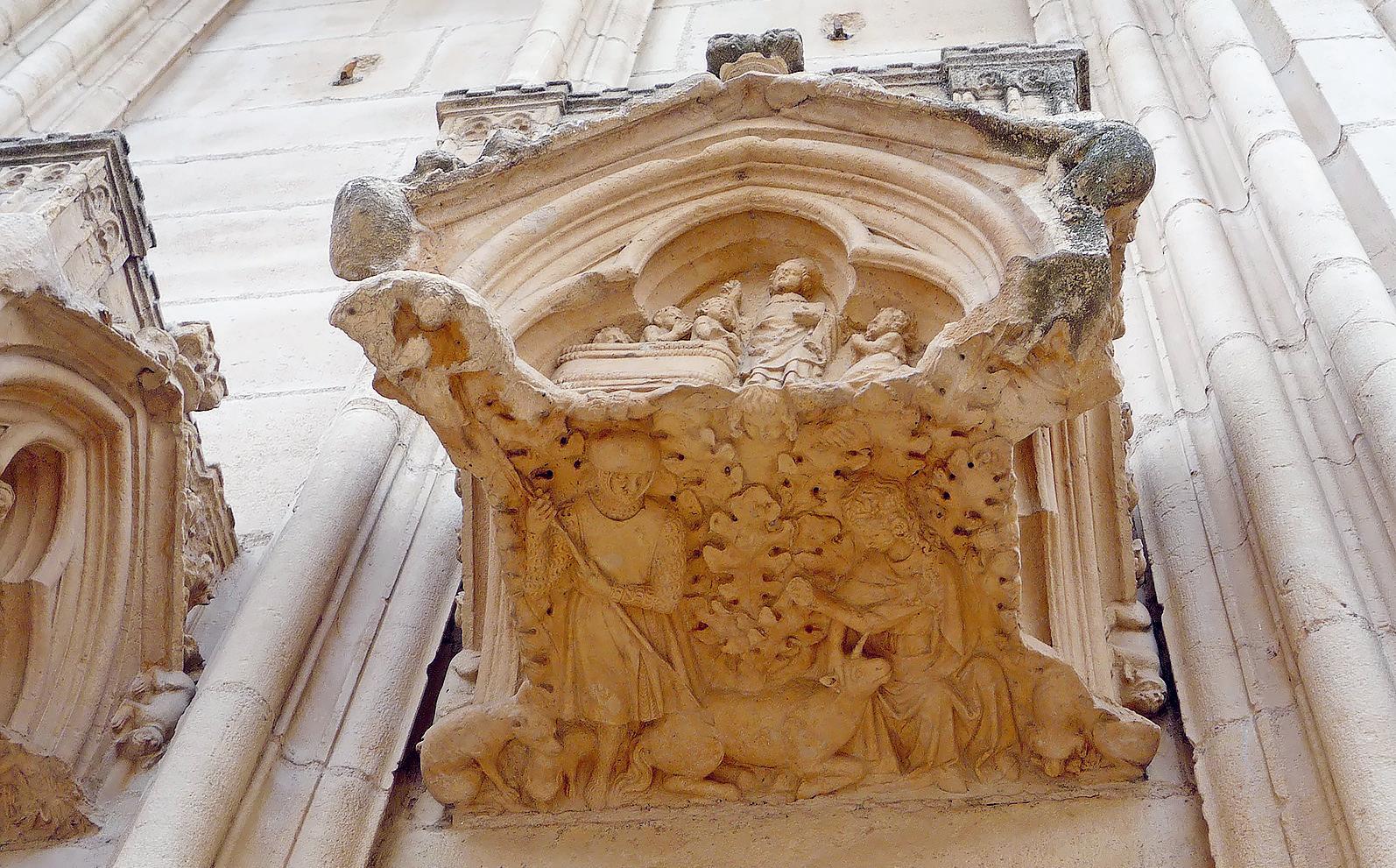

The unicorn was widely regarded as a symbol of Christ in the illustrated Bestiaries of the XIIIth century, and most viewers of the casket would have recognised the two poles of purity and adulterous lust represented here.32 The crossovers between sacred and secular, here and elsewhere in the Gothic period, were manifold, and it comes as no surprise that the unicorn was represented not just on ivories, tapestries and metalwork, but also on cathedrals, as at Lyon (Fig. 1.10).

As with the scenes on the back of the casket, all the other composite caskets include these two images juxtaposed on the left end of the box, with only minor differences in the details.

33

32 For a typical image in the Rochester Breviary and the text connected with it, of c. 1230–1350, see Morrison (2019), pl. 3.

33 The V&A casket transposes the two scenes, with the unicorn on the left.

The Barber and the other composite caskets are a distinct cultural phenomenon, offering a compilation of popular romantic scenes and images, and almost certainly intended to be presented as wedding presents or as gifts connected with courtship. However, while the subjects that covered their sides and lids might have been the images and stories that most captured the imagination of the XIIIth- and XIVth-century audience, the notion of the ivory box as a splendid gift follows a long tradition that can be traced back to the Roman era and even earlier. Elephant ivory, given its fine grain, lustrous colour and surface, and its status as a material connected with the Bible and the rulers of antiquity, was always in demand by the craftsmen and consumers of precious objects.34 And at times when elephant ivory was unavailable, alternatives such as bone and walrus ivory were employed instead, so there was rarely an era of the Middle Ages when small boxes were not being made. Many of these were for the use of the Church, as reliquaries or other liturgical vessels, but throughout the medieval period secular caskets were also much in demand.

Roman – and more precisely Late Antique – ivory and bone caskets must have been made in large numbers, but now their form and appearance has to be mostly reconstructed from the remaining single plaques that survive.35 These IVth-century caskets, by analogy with the contemporary but more valuable silver toilet caskets such as the Projecta Casket from the

34 The recent survey of Gothic ivories by Sarah M. Guérin investigates the status and use of ivory with admirable perception and a masterly command of the documentary evidence (Guérin (2022).

35 See, for instance, Weitzmann (1979), 332–333, no. 311 and Williamson (2010), 32–33, no. 2; a reconstructed casket is to be found in the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Randall (1985), 90, no. 135.

Esquiline Treasure, now in the British Museum, were certainly intended as bridal caskets, and this is a use that recurs repeatedly through the centuries.36 The bone plaques mostly show single figures rather than narrative scenes, and they were invariably attached to a wooden core. This method of construction continued into the Byzantine world, so that in the caskets produced in Constantinople in the Xth century, such as the so-called Veroli Casket now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, ivory narrative plaques with scenes from classical mythology were attached to the sides and lid.37 Like the Projecta Casket, the Veroli Casket was most probably made as a betrothal or wedding present, as its carefully selected scenes strongly suggest.38

In the medieval West before the Gothic period, the majority of the surviving ivory caskets served as reliquary caskets, and their sides were carved with figures of saints or with narratives drawn from the New Testament, as on the Farfa Casket, a South Italian work of the 1060s.39 Others were more purely decorative, including a later example also from Campania in Southern Italy, now in the Wyvern Collection in London, and numerous ivory caskets with entirely blank sheets of ivory attached to a wooden core were produced in Southern Italy and Sicily in the XIIth century and exported throughout Europe.40 These often ended up in cathedral and church treasuries, employed to contain numerous small relics, but many must also have been put to secular use, in the home and palace.

In the late XIIth century, Cologne became a centre for the production of reliquary caskets made from bone reliefs attached to a wooden core.41 Like the South Italian and Sicilian caskets, these were to enjoy considerable success as exports to neighbouring countries, partly because they must have been reasonably priced. The vast majority of the Cologne caskets were religious, but – for our purposes – the most striking piece is a small box now in the British Museum (Fig. 1.11).

The decorative scheme is given over to Tristan and Isolde, and this appears to be the earliest treatment of the subject on an object. It is of interest that the Cologne casket does not illustrate the same scene as appears on the later Parisian composite caskets, that of the young lovers beneath the tree in which King Mark hides. Instead, its sides are given over to pairs of figures in dialogue and two knights in combat, while on the lid is an enigmatic scene that appears to show Isolde in bed with King Mark, with the maid Bringvain (Brangain) bringing them the love potion that had already been taken by the young couple, leading them to their mutual passion.42

We are here on the threshold of the awakening interest in romance and the nascent representation of love scenes, manifested later in both the French ivory caskets and the Upper Rhenish Minnekästchen, carved in wood.43 Objects like the Cologne casket were the stim-

36 For the Projecta Casket and the Esquiline Treasure see Kent and Painter (1977), 44–45.

37 Williamson (2010), 76–83, no. 15; see also Cutler (1984/85).

38 Williamson (2010), 82.

39 Braca (2008); for a selection of references to ivory boxes in inventories of English treasuries see Williamson (1994), 188–190.

40 Williamson (2019), 80–81, no. 40; Knipp (2011).

41 The standard work is now Miller (1997).

42 This is the interpretation to be found in Loomis/Loomis (1938), 43–44; Robinson (2008), 209, prefers to see the couple in bed as Tristan and Isolde.

43 Kohlhaussen (1928); for an early example (c. 1250–1260) in the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum in Munich, see Haussherr (1977), 388–389, no. 532.