Cicero – Opera omnia

Ed. Andreas Cratander, Basel 1528

Supplementary volume: Introductory essay as well as text and translation of Cratander’s Letter of dedication

Begleitband: Einführung sowie Text und Übersetzung von Cratanders Widmungsbrief

Schwabe Verlag

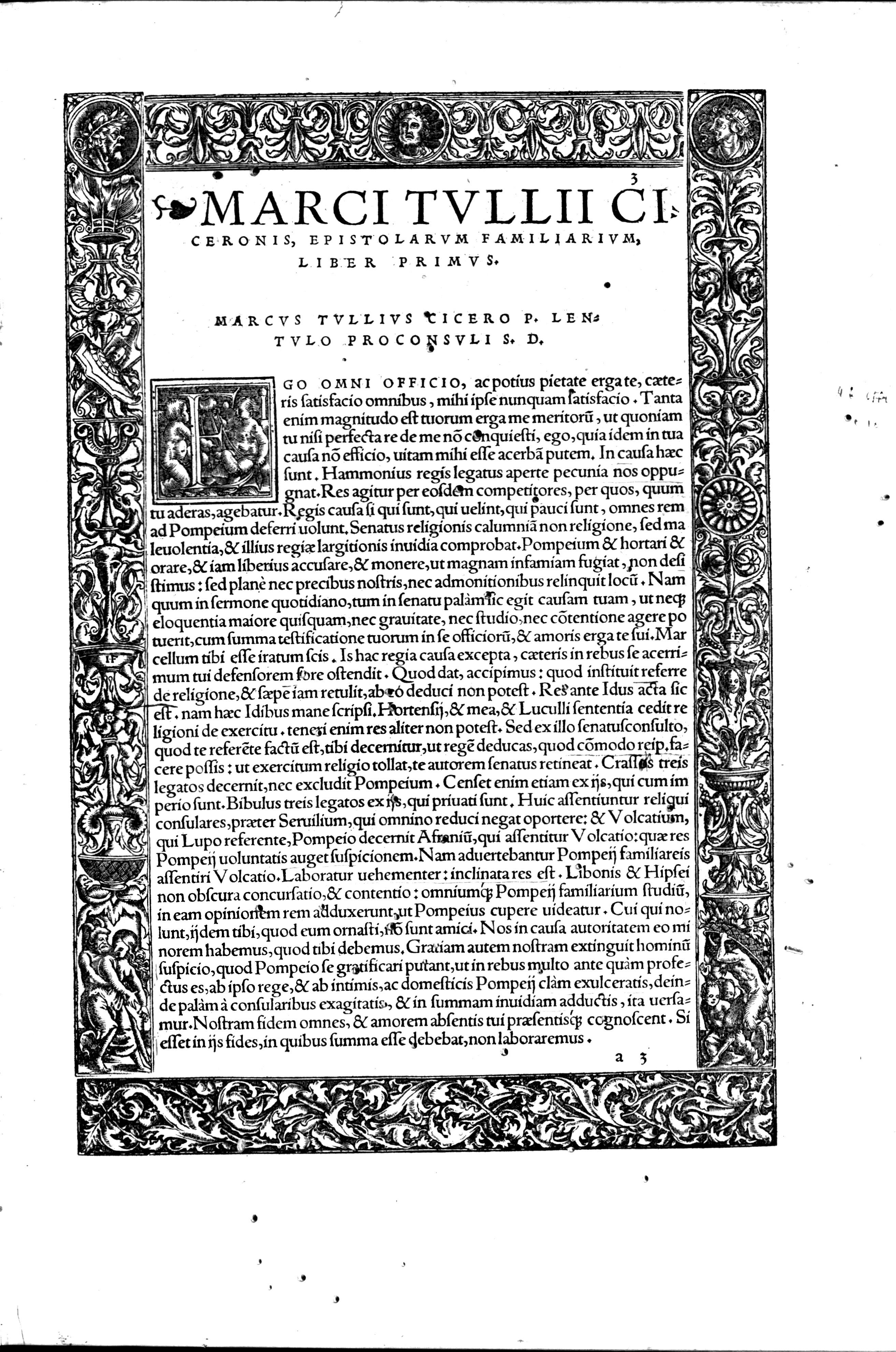

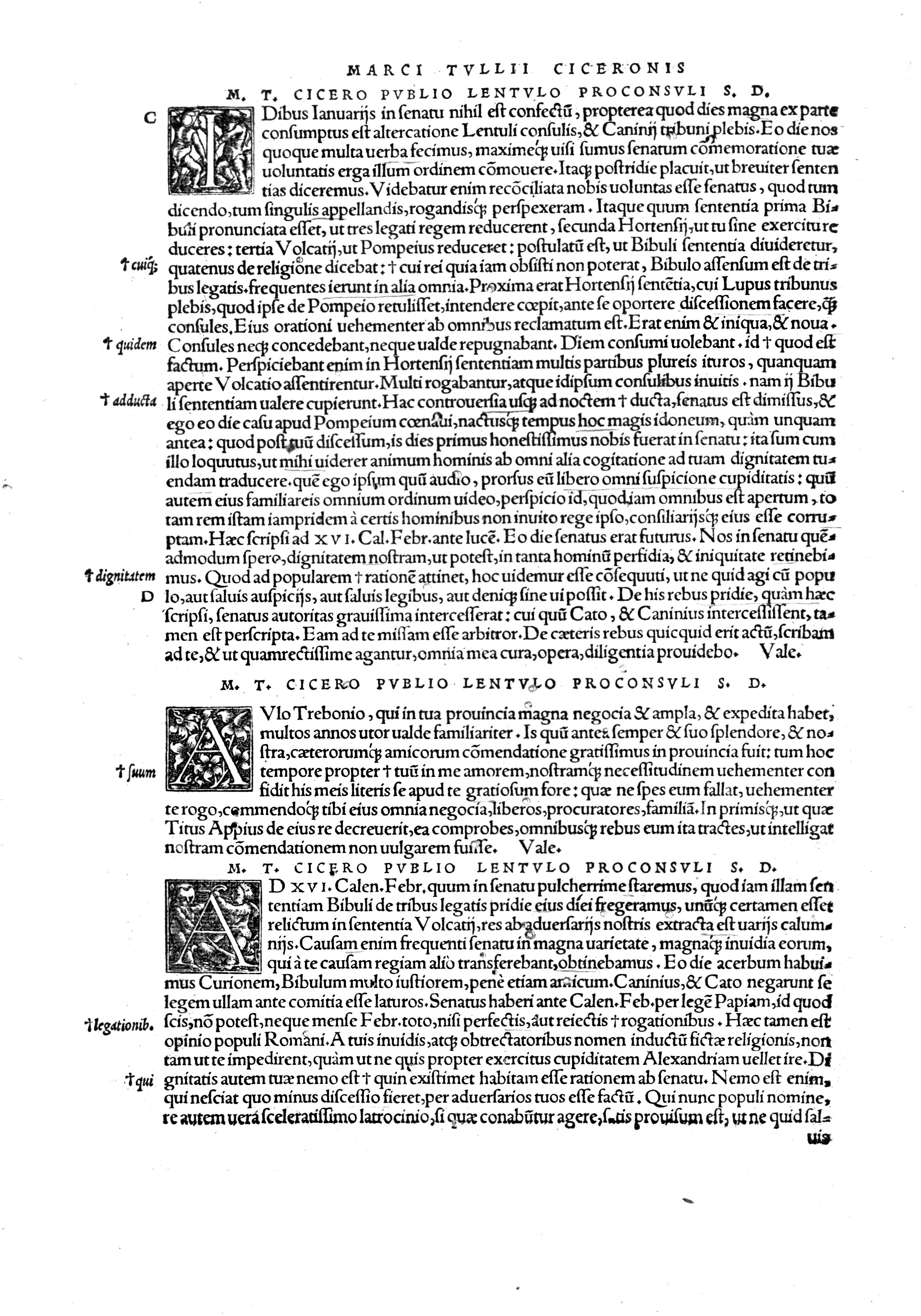

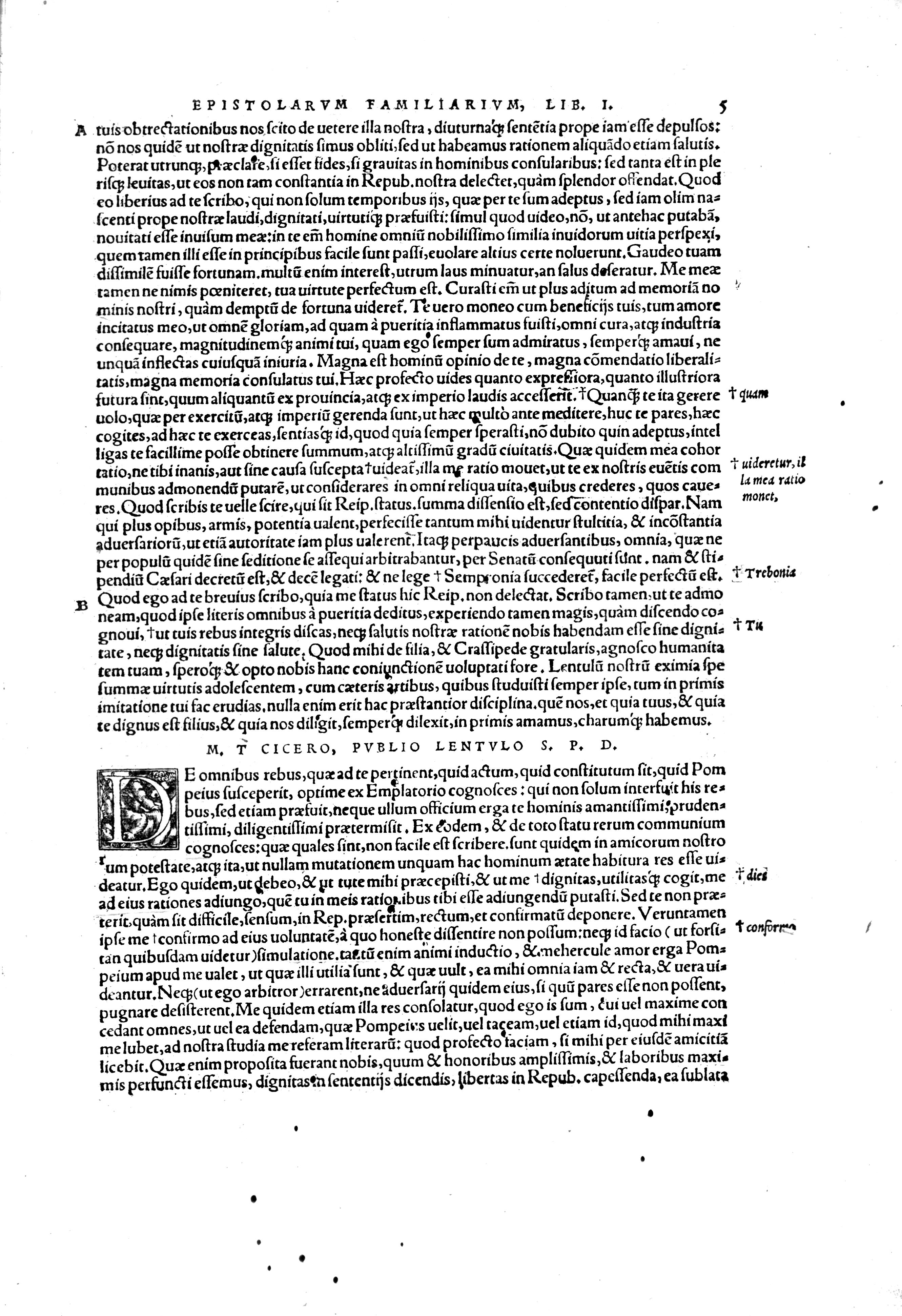

This edition offers a complete reproduction of the copy of Cratander’s edition of Cicero (1528), held at the Universitätsbibliothek Basel (shelf mark: CB I 1–2).

The two volumes of the reproduction are accompanied by a supplementary volume, including an introductory essay as well as the text and translations of Cratander’s Letter of dedication.

The publication was realised on the initiative and with the support of the Patrum Lumen Sustine- Stiftung (PLuS ), Basel, which covered all the production costs, and under the auspices of the Société Internationale des Amis de Cicéron (www.tulliana.eu), represented by the President of its Advisory Board, Ermanno Malaspina.

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

© 2022 Schwabe Verlag, Schwabe Verlagsgruppe AG, Basel, Schweiz

This work is protected by copyright. No part of it may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or translated, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Cover illustration of the supplementary volume: Cratander’s printer’s mark and excerpt from his letter of dedication, UB Basel, CB I 1–2, to.1.fol.α3

Cover of the supplementary volume: icona basel gmbh, Basel

Typesetting of the supplementary volume: mittelstadt 21, Vogtsburg-Burkheim

Reproduction and print: L’Artistica Savigliano, Savigliano

Printed in Italy

ISBN Print 978-3-7965-4343-2

rights@schwabe.ch

www.schwabe.ch

info@lartisavi.it

www.lartisticasavigliano.it

CONTENTS / INHALT Preface / Vorwort 7 Introductory essay: Cratander’s edition of Cicero’s collected works / Einführung: Cratanders Ausgabe der gesammelten Werke Ciceros 9 Bibliography and further reading / Bibliographie und Vorschläge für weitere Lektüre 37 Andreas Cratander, Letter of dedication to Ulrich Varnbüler (Latin, English, German) / Andreas Cratander, Widmungsbrief an Ulrich Varnbüler (Latein, Englisch, Deutsch) 39 Notes on the Letter of dedication / Anmerkungen zum Widmungsbrief 63 Figures / Abbildungen 67

PREFACE

These volumes provide a complete reproduction of the edition of the collected works of Marcus Tullius Cicero, published by Andreas Cratander in Basel in 1528. This is not just any book: printed in the heyday of Humanist learning in Basel, Cratander’s monumental volumes offer a particularly impressive example of the printing culture and editorial techniques of the time. Nor is it just any author: Cicero’s works – arguably the most extensive and most complex oeuvre of a single author to survive from Graeco-Roman antiquity – were one of the central points of reference in the Humanist debates on the value of tradition, language, style and of books themselves. Cratander’s edition, just as the handwritten notes that were jotted down shortly after its first appearance in the copy here reproduced, was a powerful intervention in such debates.

It is with good reason then that Cratander’s Cicero edition was chosen when the Patrum Lumen Sustine foundation (PLuS ) met with a group of scholars (along with the two authors in particular Professor Ermanno Malaspina) to develop a reproduction project that would make Humanist printing culture available to a wider audience. In an age of increasing digital availability of knowledge a printed reproduction may seem anachronistic – indeed, images of all the pages of Cratander’s edition are readily accessible online. However, the project arose from the belief that a reproduction offers readers something that cannot be replaced by images on the screen: the embodied experience of the book as artefact, an object with its own bulkiness and weight, which is not just looked at but held in one’s hands and handled and leafed through. The plan was to give an impression of how the edition might have looked and felt when it first appeared, and to offer a sense of the painstaking work that had gone into it –from the editor’s work on the text, to the work of the punchcutters, typesetters and bookbinders, to that of the Humanist scholar who read the texts pen in hand and whose notes can now be found in the margins of the book.

To accompany the reproduction, we have aimed to provide an introductory essay that sets Cratander’s edition in its wider context and highlights its key features. This additional text, along with a complete transcription and translation of the dedicatory letter with which Cratander prefaces the edition, now appears in this supplementary volume.

It has only been possible to realize this project thanks to the cooperation and contribution of a number of people and institutions, to all of whom we are very grateful. The PLuS foundation and particularly

VORWORT

Die vorliegenden Bände bieten eine vollständige Reproduktion der Edition der gesammelten Werke des Marcus Tullius Cicero, welche Andreas Cratander 1528 in Basel publizierte. Es handelt sich hierbei nicht um eine beliebige Edition: Gedruckt in der Blütezeit der humanistischen Gelehrsamkeit in Basel, zeigen Cratanders monumentale Folianten besonders eindrücklich den Stand der zeitgenössischen Druckkultur und Editionstechnik. Es handelt sich aber auch nicht um einen beliebigen Autor: Die Werke Ciceros – gewiss das umfangreichste und komplexeste Œuvre eines Autors der griechisch-römischen Antike, das erhalten ist – waren einer der wichtigsten Bezugspunkte in den humanistischen Debatten um den Wert von Tradition, Sprache, Stil und von Büchern selbst. Bei Cratanders Ausgabe ebenso wie bei den handgeschriebenen Notizen, die kurz nach ihrem Erscheinen in dem hier reproduzierten Exemplar niedergeschrieben wurden, handelt es sich um wichtige Beiträge zu diesen Debatten.

Cratanders Cicero-Ausgabe war deswegen eine naheliegende Wahl, als die Patrum Lumen Sustine -Stiftung (PLuS ) mit einer Gruppe von Wissenschaftlern (neben den beiden Autoren vor allem Professor Ermanno Malaspina) das Projekt einer Reproduktion entwickelte, das die Druckkultur des Humanismus für ein weiteres Publikum erschließen sollte. In einer Zeit der fortschreitenden Digitalisierung der Wissensbestände mag eine Reproduktion im Druck anachronistisch anmuten – in der Tat sind digitale Bilder aller Seiten von Cratanders Edition im Internet ohne Weiteres zugänglich. Das Projekt entstand jedoch in der Überzeugung, dass eine Reproduktion den Lesern etwas bietet, das durch Aufnahmen am Bildschirm nicht ersetzt werden kann: die sinnliche Erfahrung des Buches als eines Artefakts von einer bestimmten Sperrigkeit und einem nicht zu vernachlässigenden Gewicht, das nicht nur betrachtet, sondern in Händen gehalten, aufgeschlagen und durchgeblättert werden will. Es bestand daher die Absicht, einen Eindruck davon zu geben, wie sich Cratanders Edition ausgenommen und angefühlt haben könnte, als sie erstmals erschien, und die mühevolle Arbeit zu veranschaulichen, auf der eine solche Edition beruht – von der Arbeit des Editors am Text über jene der Schriftschneider, Setzer und Buchbinder bis hin zu der des humanistischen Gelehrten, der die Texte mit dem Griffel in der Hand studierte und dessen Notizen heute in den Rändern des Buchs zu finden sind.

Als Ergänzung zur Reproduktion waren wir darauf bedacht, eine Einführung zu bieten, die Cratanders Edition im Kontext ihrer Zeit erklärt und auf ihre Eigenheiten hinweist. Dieser zusätzliche Text, zusam-

its president gave the first impetus and generously provided all the necessary funding for the project. The Universitätsbibliothek Basel kindly made available high-resolution images of all pages of its copy of the original edition by Cratander, on which this reproduction is based. Ueli Dill, Head of Manuscripts and Early Prints at the Universitätsbibliothek Basel, read a full draft of the introductory essay and offered helpful comments, especially on aspects of book history. Thomas Wilhelmi contributed information on some of the individuals mentioned in Cratander’s dedicatory letter. The printing house L’Artistica Savigliano and the publisher Schwabe did an excellent job in realizing the project and producing this impressive set of three volumes with great care. We are grateful to all those who have contributed to the project, in particular Francesco Bonino of L’Artistica Savigliano and Arlette Neumann of Schwabe as well as Ermanno Malaspina, who kindly facilitated the communication between the various project partners.

We hope that readers will enjoy the result. Cambridge / London, December 2021

men mit einer vollständigen Transkription und Übersetzung von Cratanders lateinischem Widmungsbrief, der am Anfang der Ausgabe steht, ist nun in diesem Begleitband abgedruckt.

Die vorliegende Publikation hätte nicht ohne die Unterstützung und Mitwirkung einer ganzen Anzahl von Personen und Institutionen realisiert werden können. Ihnen allen sind wir zu großem Dank verpflichtet, allen voran der PLuS -Stiftung und besonders ihrem Präsidenten, welche zu diesem Projekt den ersten Anstoß gaben und großzügig die Mittel zur Realisierung gewährten. Die Universitätsbibliothek Basel stellte freundlicherweise hochaufgelöste Aufnahmen aller Seiten ihres Exemplars von Cratanders Edition zur Verfügung, welche dieser Reproduktion zugrunde liegen. Ueli Dill, Leiter der Abteilung Handschriften und Drucke der Universitätsbibliothek Basel, las einen Entwurf der gesamten Einführung; wir verdanken ihm zahlreiche wichtige Hinweise, insbesondere zu Fragen der Buchgeschichte. Thomas Wilhelmi steuerte Informationen zu einigen der von Cratander im Widmungsbrief erwähnten Personen bei. Die Druckerei L’Artistica Savigliano und der Schwabe-Verlag trugen wesentlich zur Realisierung bei und produzierten mit außerordentlicher Sorgfalt dieses eindrucksvolle Ensemble von drei Bänden. Wir danken allen, die am Gelingen des Projektes beteiligt waren, insbesondere Francesco Bonino von L’Artistica Savigliano, Arlette Neumann vom Schwabe-Verlag sowie Ermanno Malaspina, der die verschiedenen Projektpartner miteinander ins Gespräch brachte.

Wir hoffen, dass Leserinnen und Leser am Ergebnis ihre Freude haben werden.

8 Preface / Vorwort

C. S. L.

/ G. M.

C. S. L.

G.

Cambridge / London, Dezember 2021

/

M.

INTRODUCTORY ESSAY:

CRATANDER’S EDITION OF CICERO’S COLLECTED WORKS

EINFÜHRUNG:

CRATANDERS AUSGABE DER GESAMMELTEN WERKE CICEROS

1 – Introduction

These volumes reproduce the edition of Cicero’s collected works published by Andreas Cratander (c. 1485–c. 1540) in Basel in 1528; the print is based on the richly annotated copy held by the University Library in Basel (shelf mark: CB I 1–2; digital version available at www.e-rara.ch; information on further copies at VD16 C 2814). Cratander’s publication provides important testimony for the history of Humanist activity in Basel and for the development of editorial techniques for works of ancient authors; thus, it deserves to be made more widely available to modern readers in the original format intended by Cratander. Moreover, the handwritten annotations in the Basel copy offer a unique glimpse into the reading habits and scholarly techniques that underpinned intellectual discourse in sixteenth-century Basel.

To set these volumes into their historical context and to outline its particular characteristics, this essay will provide brief sketches of Cratander’s biography and of the life, works and reception of Cicero; moreover, it will give an overview of the intellectual and scholarly framework in Humanist Basel, the conditions of book production at the time, the coverage and editorial principles of this edition as well as the distinguishing features of the copy held at Basel.

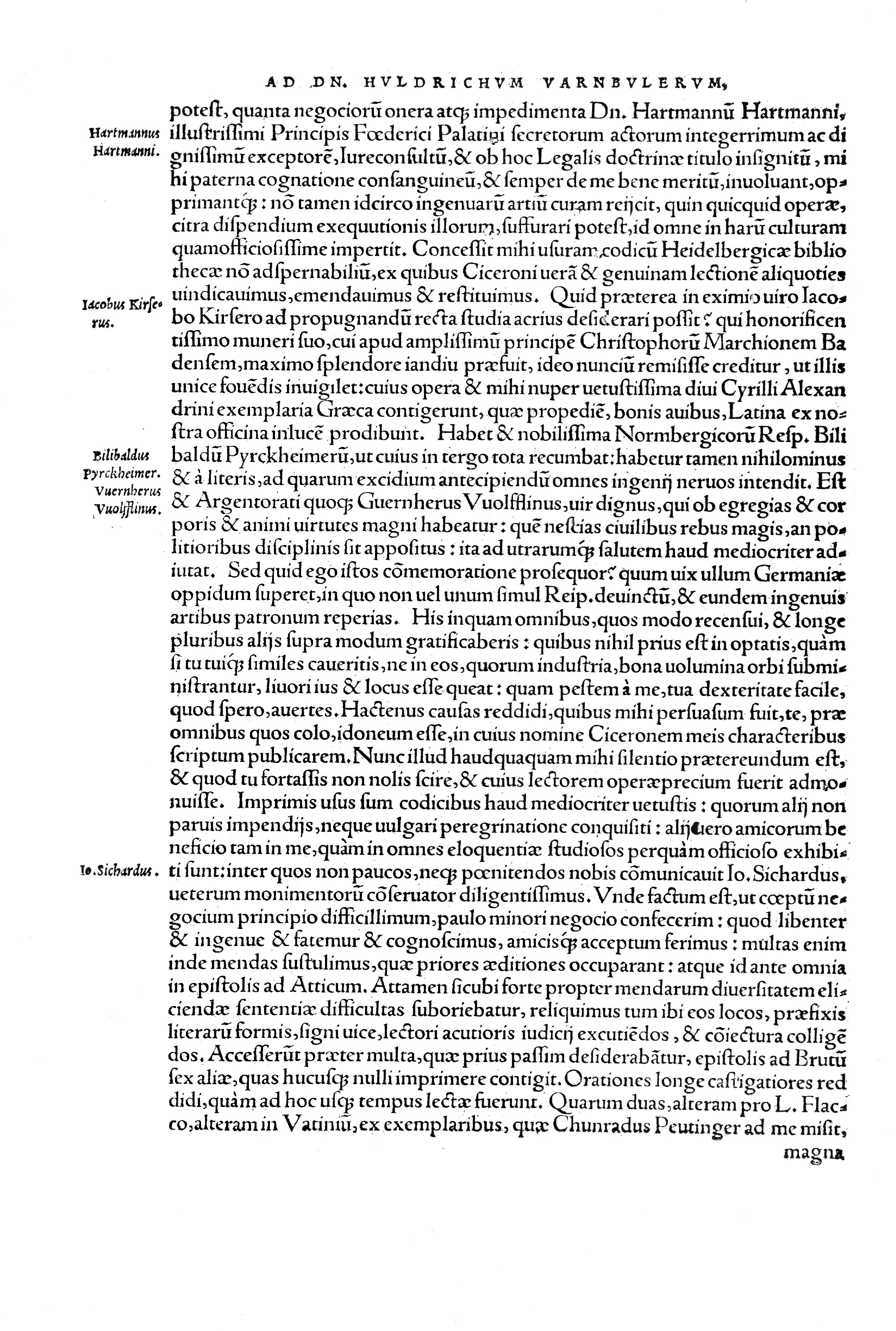

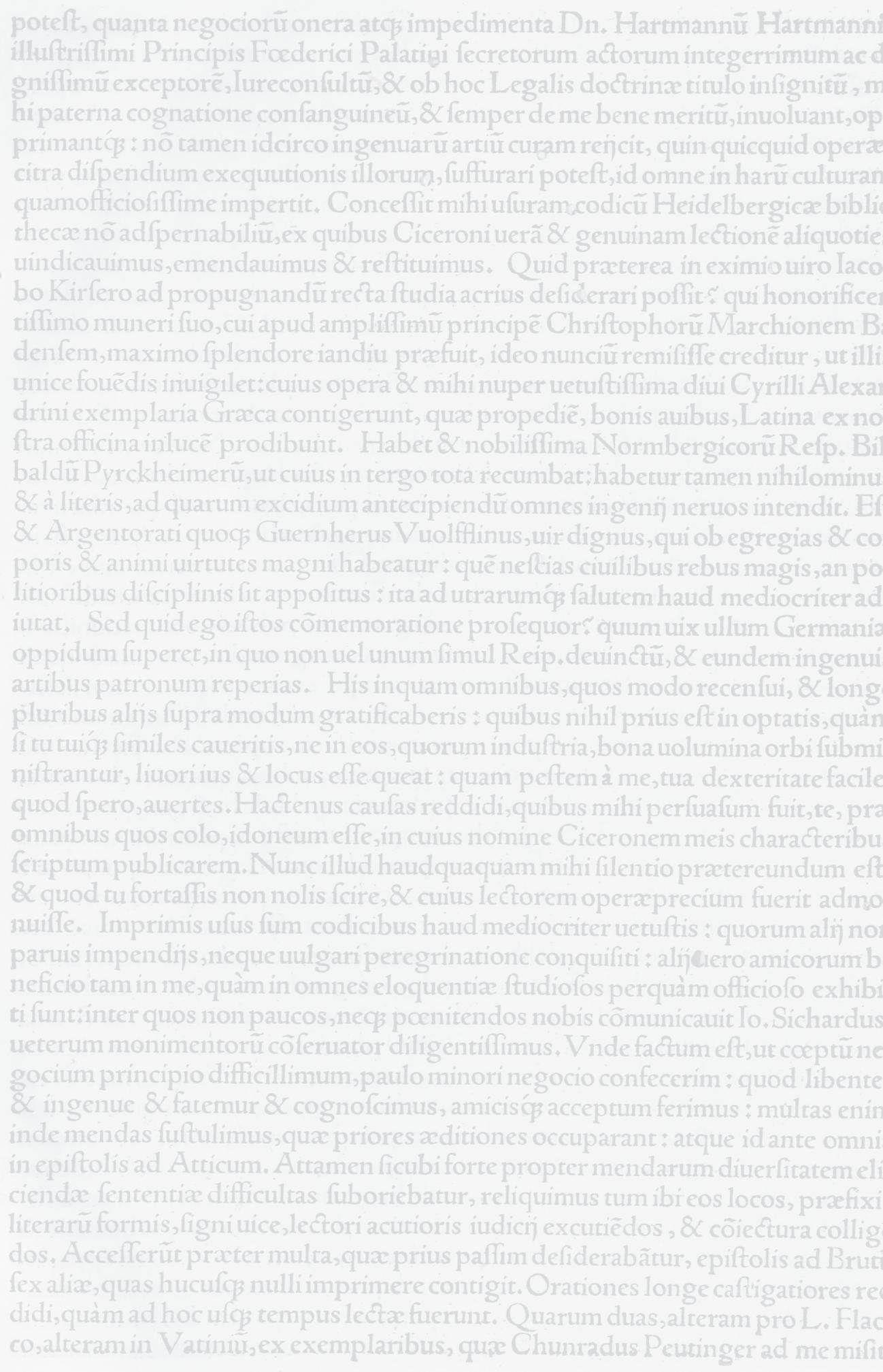

In addition, in order to illustrate Cratander’s editorial principles and the social and intellectual context of this edition as well as to present a flavour of Cratander’s own writing, a (slightly modernized) transcription of the letter of dedication prefacing the edition, along with translations into English and German, has been added (see below, p. 63). Some of the points made in Cratander’s prefatory letter will also be commented on here, with references to the relevant passages.

1 – Einleitung

In diesen Bänden ist die Gesamtausgabe aller Werke Ciceros, die von Andreas Cratander (ca. 1485 – ca. 1540) 1528 in Basel veröffentlicht wurde, reproduziert. Die Reproduktion basiert auf dem reich annotierten Exemplar in der Universitätsbibliothek Basel (Signatur: CB I 1–2; Digitalisat: www.e-rara.ch; Informationen zu weiteren Exemplaren: VD16 C 2814). Cratanders Publikation ist ein wichtiges Zeugnis für die Geschichte humanistischer Aktivität in Basel und für die Entwicklung der Editionstechniken zu Werken antiker Autoren. Daher verdient sie es, heutigen Lesern leichter zugänglich gemacht zu werden, und zwar in der von Cratander intendierten Originalversion. Außerdem erlauben die handgeschriebenen Anmerkungen im Basler Exemplar einen einmaligen Einblick in die Lesegewohnheiten und wissenschaftlichen Praktiken, auf denen der intellektuelle Austausch im Basel des sechzehnten Jahrhunderts beruhte.

Um diese Ausgabe in ihren historischen Kontext zu stellen und ihre besonderen Charakteristika zu illustrieren, bietet diese Einführung Kurzdarstellungen zu Cratanders Biographie sowie zu Leben, Werk und Rezeption Ciceros; ferner findet sich hier ein Überblick über das intellektuelle und wissenschaftliche Umfeld im humanistischen Basel, die zeitgenössischen Bedingungen für Buchproduktion, den Umfang und die editorischen Prinzipien dieser Edition sowie die spezifischen Merkmale des Basler Exemplars.

Außerdem ist zur Illustration von Cratanders editorischen Prinzipien sowie des sozialen und intellektuellen Kontexts dieser Edition, und um einen Eindruck von Cratander als selbstständigem Autor zu vermitteln, eine (leicht modernisierte) Transkription des Widmungsbriefs, der der Ausgabe als Vorwort vorangestellt ist, mit Übersetzungen ins Englische und Deutsche, hinzugefügt (s. u. S. 63). Einige der Punkte, die in Cratanders Widmungsbrief thematisiert sind, werden hier ebenfalls diskutiert, mit Verweis auf die jeweils relevanten Stellen.

2 – Basel as a centre for Humanist book production

The university at Basel was founded in the second half of the fifteenth century, when the infrastructure for printing was also established. The city became a ma-

2 – Basel als Zentrum humanistischer Buchproduktion

Die Universität Basel wurde in der zweiten Hälfte des fünfzehnten Jahrhunderts gegründet, zu einer Zeit, als auch die Infrastruktur für das Druckwesen entstand.

jor centre for book printing from about 1470, not only as a result of the presence of the university and its attractiveness for Humanists from elsewhere, but also for commercial reasons: Basel’s importance was based on its convenient geographical position along major trade routes, its wealthy population and the availability of paper makers as well as draughtsmen and artists needed for book production. The large number of printers active in Basel in the late fifteenth and the sixteenth centuries includes, in addition to Andreas Cratander, for instance Bernhard Richel, Michael Wenssler, Johannes Amerbach, Johannes Froben, Johannes Petri, Adam Petri, Nicolaus Episcopius, Johann Herwagen, Robert Winter, Johannes Oporinus and Valentin Curio.

The Basel printing houses published classical and Humanist texts; they were in close contact with contemporary authors and the educated elite. Printing activity at Basel became known for its speed, quality and broad coverage, facilitated by relative freedom from (clerical) censorship. Works printed in this period include books in Latin, Greek, German and Hebrew, religious and secular texts, legal works, textbooks as well as the latest writings of Humanists, many of whom were resident in the city. The prints were attractively presented and sometimes illustrated by contemporary artists such as Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/8–1543) or Urs Graf the Elder (c. 1485–1528).

As Cratander implies in the letter of dedication, a major threat to the reputation and success of a printing house was the custom of rival printing establishments to create cheaper reprints of books that had originally been put together with a lot of effort, time and funds. Only in 1531 (three years after the publication of Cicero’s works by Cratander) did a rule come into effect in Basel that banned reprints within three years after the first publication. Some protection against such unauthorized reprints was offered by obtaining the imperial privilege (again banning reprints within a certain period), which Cratander did, with the dedicatee’s help, as he says (Praef. 11): it can be seen on the title page of the Cicero edition.

Von etwa 1470 an wurde die Stadt zu einem wichtigen Zentrum für Buchdruckerei, nicht nur wegen der Universität und ihrer Attraktivität für Humanisten aus anderen Städten, sondern auch aus wirtschaftlichen Gründen: Die Bedeutung von Basel beruhte auf der günstigen geographischen Lage an wichtigen Handelswegen, der wohlhabenden Bevölkerung und der Verfügbarkeit der für die Buchproduktion benötigten Papierhersteller, Zeichner und Künstler. Zu der großen Zahl von Druckern, die in Basel im späten fünfzehnten und im sechzehnten Jahrhundert tätig waren, gehören neben Andreas Cratander unter anderem Bernhard Richel, Michael Wenssler, Johannes Amerbach, Johannes Froben, Johannes Petri, Adam Petri, Nicolaus Episcopius, Johann Herwagen, Robert Winter, Johannes Oporinus und Valentin Curio.

Die Basler Druckereien veröffentlichten klassische und humanistische Texte; sie standen in engem Kontakt mit zeitgenössischen Autoren und der gebildeten Elite. Das Druckwesen in Basel wurde bekannt für Geschwindigkeit, Qualität und ein breites Angebot, begünstigt durch eine relative Freiheit von (klerikaler) Zensur. Zu den damals gedruckten Werken zählten Bücher in lateinischer, griechischer, deutscher und hebräischer Sprache, religiöse und säkulare Texte, juristische Werke, Lehrbücher sowie die neuesten Schriften der Humanisten, von denen viele in der Stadt lebten. Die Drucke waren ansprechend gestaltet und manchmal illustriert von zeitgenössischen Künstlern wie Hans Holbein dem Jüngeren (1497/8–1543) oder Urs Graf dem Älteren (ca. 1485–1528).

Wie Cratander im Widmungsbrief impliziert, bestand eine signifikante Bedrohung des Ansehens und des Erfolgs einer Druckerei in der Gewohnheit konkurrierender Druckereien, billigere Nachdrucke von Büchern zu publizieren, die ursprünglich mit viel Arbeits-, Zeit- und Geldaufwand erstellt worden waren. Erst 1531 (drei Jahre nach der Publikation von Cratanders Cicero-Edition) wurde in Basel eine Regelung eingeführt, mit der Nachdrucke innerhalb der ersten drei Jahre nach einer Erstveröffentlichung verboten wurden. Einen gewissen Schutz gegen solche unautorisierten Nachdrucke bot das sogenannte kaiserliche Privileg (das ebenfalls Nachdrucke innerhalb einer gewissen Zeitspanne untersagte): Mit Hilfe des Widmungsempfängers, wie Cratander sagt (Praef. 11), war es ihm gelungen, dieses Privileg zu erhalten: es ist auf der Titelseite der Cicero-Edition zu sehen.

Andreas Cratander (c. 1485 – c. 1540), one of the important printers in Humanist Basel, was born in Strasbourg and was originally called Andreas Hartmann. From 1502 to 1503 he was at the University of Heidelberg, acquiring a bachelor of arts degree. After some

Andreas Cratander (ca. 1485 – ca. 1540), einer der bedeutenden Drucker im humanistischen Basel, wurde in Straßburg geboren und hieß ursprünglich Andreas Hartmann. Von 1502 bis 1503 studierte er an der Universität Heidelberg, wo er den Abschluss eines Bac-

10 Introductory essay / Einführung

3 – Andreas Cratander

3 – Andreas Cratander

years as a printer’s apprentice in Basel and Strasbourg, he settled in Basel around 1515; he ran his own printing workshop there from 1518, after having gained experience of this trade while a printer’s assistant. In 1519 he was made a citizen of Basel and became a member of a local guild (‘Zunft zu Safran’) and later (1530) of another, more prestigious one (‘Zunft zum Schlüssel’); printers were free to choose one of the city’s guilds, which enabled them to obtain respected civic positions. In 1536 Cratander sold the printing shop and was then active as a bookseller.

Starting with the first editions he released from his own workshop from 1518, he called himself ‘Cratander’ (by a Graeco-Latin adaptation of his name, deriving from Greek kratos , ‘strength’, and an ē r , andros , ‘man’). Cratander was in touch with numerous scholars, other printers and artists of the time, including Hans Holbein the Younger, who created printer’s marks and book illustrations for Cratander. A version of Cratander’s printer’s mark, designed by Hans Holbein, appears on the title page of the Cicero edition; the woodcut initials marking the beginning of new works in Cratander’s Cicero edition are likely to go back to Holbein as well.

Cratander’s printing house produced prints of more than 200 works, particularly of works in Latin, but also in Greek, German, French and Hebrew. The publications consist particularly of Humanist school editions and new editions of ancient authors (e. g. Homer, Pindar, Aristotle, Aristophanes, Xenophon, Isocrates, Plutarch, Theophrastus, Theocritus, Hippocrates, Galen, Plautus, Cicero, Sallust, Pliny, Apuleius, Prudentius) as well as biblical texts and theological writings, especially by reformers such as Johannes Oecolampadius (1482–1531), with whom Cratander entertained close relations.

calaureus erwarb. Nach einigen Jahren als Druckergehilfe in Basel und Straßburg ließ er sich um 1515 endgültig in Basel nieder; ab 1518 führte er dort einen eigenen Druckereibetrieb, nachdem er durch seine Tätigkeit als Druckergehilfe im Druckgewerbe Erfahrungen gesammelt hatte. 1519 erhielt er das Bürgerrecht in Basel und wurde Mitglied in einer Zunft vor Ort (‚Zunft zu Safran‘) und später (1530) in einer anderen, angeseheneren Zunft (‚Zunft zum Schlüssel‘); Drucker hatten die Möglichkeit, eine der Zünfte in der Stadt zu wählen, wodurch sie angesehene bürgerliche Positionen erlangen konnten. 1536 verkaufte Cratander die Druckerei und war dann als Buchhändler aktiv.

Von den ersten Ausgaben an, die in seiner Druckerei ab 1518 erschienen, nannte er sich ‚Cratander‘ (mit einer griechisch-lateinischen Adaptation seines Namens, abgeleitet von griechisch kratos , ‚Stärke‘, und an ē r , andros , ‚Mann‘). Cratander war in Kontakt mit zahlreichen Gelehrten, anderen Druckern und Künstlern seiner Zeit, zum Beispiel mit Hans Holbein dem Jüngeren, der Druckermarken und Buchillustrationen für Cratander entwarf. Eine Version von Cratanders Druckermarke, geschaffen von Hans Holbein, befindet sich auf der Titelseite der Cicero-Edition. Die HolzschnittInitialen, die den Beginn neuer Werke in Cratanders Cicero-Ausgabe markieren, stammen wahrscheinlich auch von Holbein.

Cratanders Druckerei veröffentlichte Drucke von mehr als 200 Werken, vor allem von solchen auf Latein, aber auch solchen auf Griechisch, Deutsch, Französisch und Hebräisch. Die Publikationen bestehen vor allem aus humanistischen Schulausgaben und neuen Ausgaben antiker Autoren (z. B. Homer, Pindar, Aristoteles, Aristophanes, Xenophon, Isokrates, Plutarch, Theophrast, Theokrit, Hippokrates, Galen, Plautus, Cicero, Sallust, Plinius, Apuleius, Prudentius) sowie biblischen Texten und theologischen Schriften, insbesondere von Reformern wie Johannes Oekolampad (1482–1531), mit denen Cratander in engem Kontakt stand.

4 – Editions of Cicero’s works and Cratander’s edition

Among the books issued by Cratander’s printing workshop, the complete edition of the works of Cicero published in 1528 is particularly significant, both because of its interaction with contemporary discussions on this influential author and because it demonstrates progressive methods in approaching and presenting the work of an ancient author.

The edition appeared in a period in which Cicero’s writings were edited numerous times while his role as the paradigmatic author of the Latin language, an issue that dominated intellectual discourse, was discussed intensively. In the same year, for instance, also in Basel, Johannes Froben (c. 1460–1527), published the di-

4 – Editionen der Werke Ciceros und Cratanders Ausgabe

Unter den Büchern, die in Cratanders Druckerei hergestellt wurden, ist die Gesamtedition der Werke Ciceros von 1528 besonders bedeutsam, sowohl wegen ihrer Stellung innerhalb zeitgenössischer Diskussionen zu diesem wirkungsmächtigen Autor als auch weil sie fortschrittliche Methoden in der Bearbeitung und Präsentation der Werke eines antiken Autors aufweist.

Diese Ausgabe erschien zu einer Zeit, in der Ciceros Schriften vielfach ediert wurden, während seine Rolle als paradigmatischer Autor der lateinischen Sprache, wodurch er im intellektuellen Diskurs dominierte, intensiv diskutiert wurde. Zum Beispiel publizierte in demselben Jahr, ebenfalls in Basel, Johannes Froben

Introductory essay / Einführung 11

alogue Ciceronianus (1528) by Erasmus of Rotterdam (c. 1466–1536; resident in Basel 1514–1516, 1521–1530, 1535–1536), a text that programmatically deals with the question of how the literary production of that time related to that of classical antiquity; it critically discusses the extent to which Cicero’s Latin style should be the model for those aiming to write in Latin in the present (alluded to at Praef. 6).

Cratander’s Cicero edition contributes to this conversation: in the letter of dedication Cratander makes it clear that he has chosen the works of Cicero for publishing since they are universally held in high regard and since greater accessibility as achieved by this print will support their study. Thereby he takes a stand as he accepts the high regard for Cicero. At the same time, he stresses that he aims to present all the works in a single, carefully prepared edition, thus indicating that this was not yet common at the time. The letter of dedication is addressed to Ulrich Varnbüler (1474–1545). Varnbüler was a politically active diplomat and official, and he was a Humanist and a friend of Erasmus of Rotterdam and Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528).

Within the editorial history of Cicero’s works Cratander’s edition is not the first printed edition of all writings of Cicero (preceded in turn by editions of individual works after the invention of the printing press, going back to the first edition of a work of any classical author, Cicero’s De oratore , published in 1465 by Arnold Pannartz and Conrad Sweynheym). In particular, Cratander’s project of editing Cicero’s complete works was anticipated by the editio princeps of Cicero’s Opera by Alexander Minutianus (c. 1450–1522), first published in Milan in 1498/99 (followed by later editions).

In contrast to that by Cratander, this edition does not seem to provide text-critical notes, even if Minutianus stresses at the beginning that an effort had been made to collect and take account of various manuscripts; moreover, because he had to print the works in the order in which manuscripts became available to him, he was not able to arrange them in a systematic way.

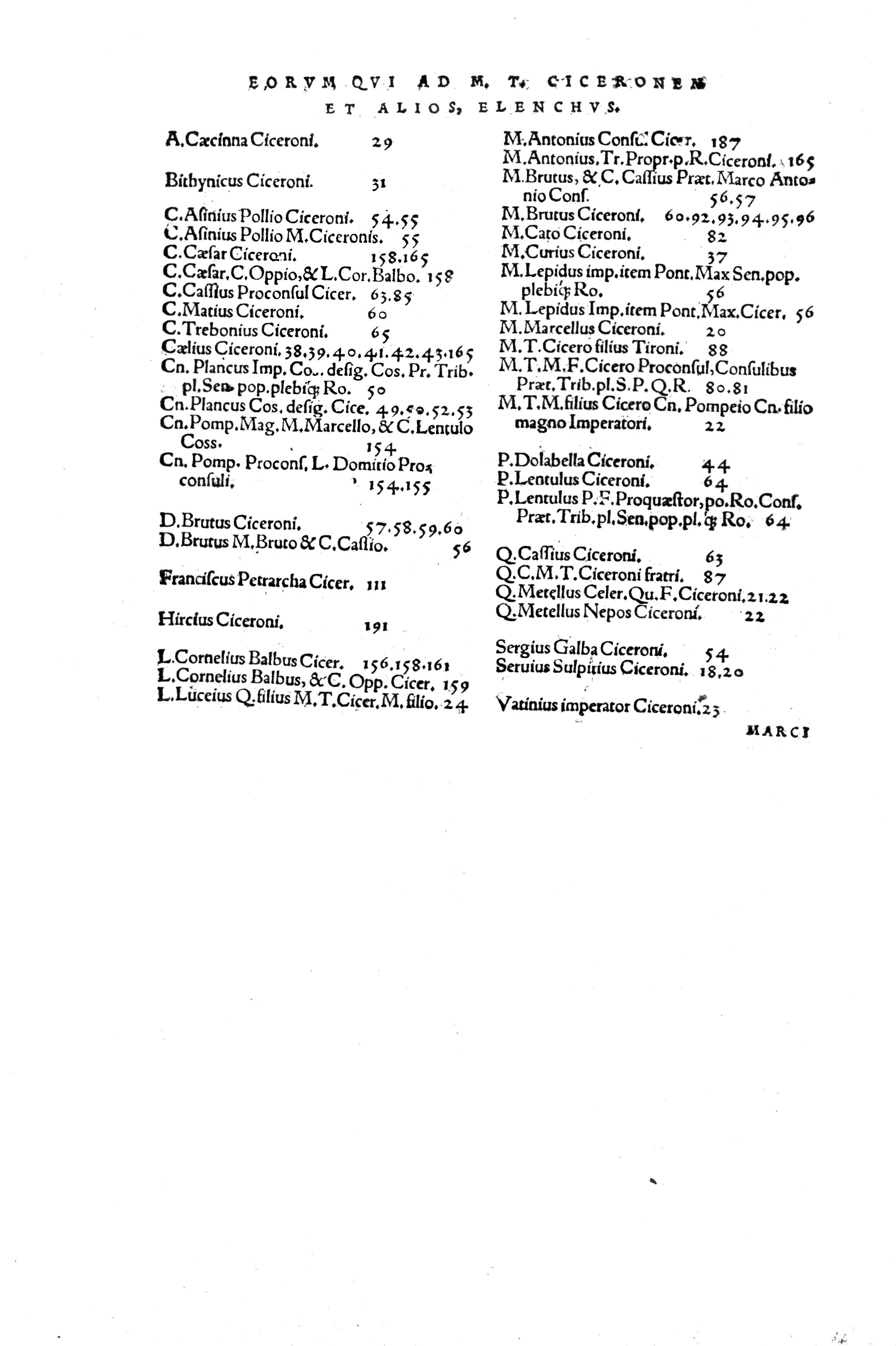

Neither is Cratander’s edition the first to include commentary notes. In fact, he reprints existing commentary notes by earlier and contemporary scholars. His edition stands out because it offers two types of annotation: notes on the text (printed in the margin) and explanatory comments (given in a separate section). Thus, there is a clear distinction between the different kinds of annotations and their respective value for readers who wish to gain a full understanding of the text’s history and meaning.

Cratander seems to be the first printer and editor of Cicero’s works who attempts to edit the entire oeuvre of Cicero systematically on the basis of the transmission, to apply text-critical methods consistently and to document variants in an accessible format for readers. Some of these principles were taken up in later editions of the works of Cicero and of other classical authors,

(ca. 1460–1527) den Dialog Ciceronianus (1528) von Erasmus von Rotterdam (ca. 1466–1536; wohnhaft in Basel 1514–1516, 1521–1530, 1535–1536), einen Text, der sich programmatisch mit der Frage befasst, wie die literarische Produktion dieser Zeit sich zu jener der klassischen Antike verhält; das Werk setzt sich in kritischer Weise mit der Frage auseinander, in welchem Ausmaß Ciceros lateinischer Stil für diejenigen, die in der Gegenwart Latein schreiben wollen, ein Modell sein solle (Praef. 6 spielt darauf an).

Cratanders Cicero-Ausgabe trägt zu dieser Diskussion bei: Im Widmungsbrief macht Cratander klar, dass er Ciceros Werke deswegen für die Publikation ausgewählt habe, weil sie allgemein hochgeschätzt würden und der durch den vorliegenden Druck ermöglichte Zugang ihre breitere Lektüre fördern werde. Damit bezieht er insofern Position, als er die Hochschätzung

Ciceros gelten lässt. Zugleich betont er, dass er beabsichtige, alle Werke in einer einzigen sorgfältig zusammengestellten Edition zu präsentieren, womit er impliziert, dass das zu dieser Zeit noch nicht allgemein üblich war. Der Widmungsbrief richtet sich an Ulrich Varnbüler (1474–1545). Varnbüler war als politisch aktiver Diplomat tätig und hatte verschiedene öffentlich Ämter inne, und er war ein Humanist und ein Freund von Erasmus von Rotterdam und Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528).

Innerhalb der Editionsgeschichte der Werke Ciceros ist Cratanders Ausgabe nicht der erste Druck aller Schriften Ciceros (Ausgaben einzelner Werke Ciceros gab es seit der Erfindung des Drucks, angefangen mit der ersten Edition eines Werks eines antiken Autors überhaupt, von Ciceros De oratore , gedruckt 1465 von Arnold Pannartz und Conrad Sweynheym). Vor Cratanders Projekt einer Gesamtedition liegt bereits die editio princeps von Ciceros Opera durch Alexander Minutianus (ca. 1450–1522), zuerst veröffentlicht in Mailand 1498/99 (worauf spätere Ausgaben folgten). Im Unterschied zu Cratanders Ausgabe scheint diese Edition keine textkritischen Anmerkungen zu enthalten, auch wenn Minutianus am Anfang betont, dass man sich bei der Erstellung des Textes darum bemüht habe, verschiedene Handschriften zu sammeln und zu berücksichtigen; da er außerdem die Werke in der Reihenfolge drucken musste, in der er Zugang zu den Handschriften bekam, war es ihm nicht möglich, sie systematisch anzuordnen.

Cratanders Ausgabe ist auch nicht die erste Edition mit Kommentarbemerkungen. Im Gegenteil, er druckte bereits vorhandene Kommentarbemerkungen früherer und zeitgenössischer Gelehrter wieder ab. Seine Edition zeichnet sich dadurch aus, dass sie zwei verschiedene Arten von Anmerkungen enthält: Anmerkungen zur Textgestaltung (am Rand) einerseits und erläuternde Kommentare (in einem separaten Abschnitt) andererseits. Auf diese Weise ergibt sich eine klare Trennung zwischen den verschiedenen Arten der

12 Introductory essay / Einführung

but it took some time until such conventions became standard to the extent that they are today. Some of Cratander’s emendations still appear in the textual apparatus of modern editions.

Kommentierung und ihres jeweiligen Werts für Leser, die ein volles Verständnis von der Geschichte und der Bedeutung des Texts gewinnen möchten.

Cratander scheint der erste Drucker und Herausgeber von Ciceros Werken zu sein, der versucht, das gesamte Œuvre Ciceros systematisch auf der Basis der Überlieferung zu edieren, textkritische Methoden konsequent anzuwenden und Varianten in einer für Leser leicht zugänglichen Form zu dokumentieren. Einige dieser Prinzipien wurden in späteren Ausgaben der Werke Ciceros und anderer antiker Autoren übernommen, aber es dauerte eine gewisse Zeit, bis solche Konventionen, wie sie heute üblich sind, entwickelt und implementiert waren. Noch heute finden sich manche Emendationen Cratanders im kritischen Apparat moderner Ausgaben.

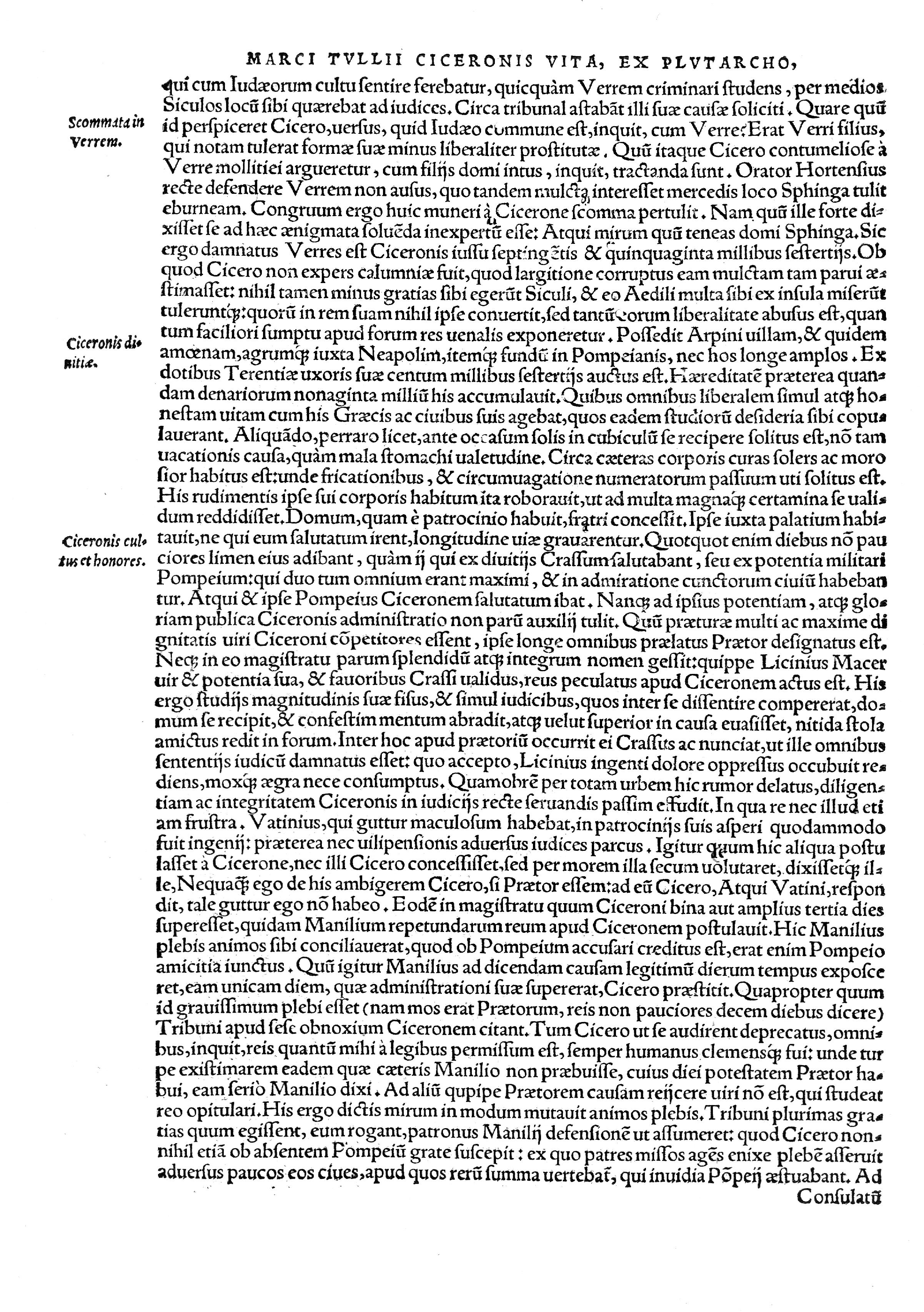

5 – Cicero’s life, literary activity and Humanist reception

Cratander’s monumental edition enshrines the works of one of the most important figures from antiquity, which were at the centre of debates on the legacy of classical antiquity and the importance of secular education in Cratander’s time.

Marcus Tullius Cicero was born in 106 BCE in Arpinum, a provincial town some 100 km to the southeast of Rome. His father was of the equestrian order; suffering from ill health, he led a secluded life. Yet, being a man of means and connections, he ensured that his sons Marcus and Quintus enjoyed the best education at Rome. Here, young Cicero showed an extraordinary aptitude and facility in the study of poetry, philosophy and oratory in both Greek and Latin that would define much of his later life and activity. Cicero was introduced into the first circles of Rome’s senatorial elite although he was not the scion of a noble family that had produced holders of high office. That he nonetheless acceded to the consulate, the highest office, without relying on the support network of one of the great families remained a source of pride throughout his life. His status as a ‘new man’ (homo novus ) from a provincial town, however, also opened him to the attacks of his noble rivals.

During the turbulent years of the Social War (91–87 BCE) – when he witnessed with some fascination the deeds of his compatriot C. Marius, to which he would later dedicate a poem (now lost) – Cicero served briefly in the army, but otherwise dedicated himself to the study of oratory and philosophy. His earliest extant work, the systematic account of rhetoric in De inventione (c. 84 BCE), does not only attest to his intellectual pursuits at the time but also to his ambitions: its preface, which was to have a formidable influence on later notions of ‘humanist’ education, offers a praise of rhetoric and advocates the ideal of the political uses of

5 – Ciceros Leben, literarische Tätigkeit und Rezeption bei den Humanisten

Cratanders monumentale Edition ist den Werken einer der herausragendsten Figuren der antiken Welt gewidmet, die in Cratanders Zeit im Zentrum von Debatten über das Erbe der klassischen Antike und der Bedeutung säkularer Bildung standen.

Marcus Tullius Cicero wurde 106 v. Chr. in Arpinum geboren, einer Provinzstadt etwa 100 km südöstlich von Rom. Sein Vater gehörte zum Ritterstand; von gesundheitlichen Problemen geplagt, führte er ein zurückgezogenes Leben. Dank seines Wohlstands und seiner guten Verbindungen konnte er seinen Söhnen Marcus und Quintus eine hervorragende Ausbildung in Rom ermöglichen. Der junge Cicero zeigte früh eine besondere Begabung im Umgang mit der griechischen und römischen Dichtung, Philosophie und Redekunst, die sein weiteres Leben und Wirken wesentlich bestimmen sollte. Obwohl er nicht aus einer aristokratischen Familie stammte, die Inhaber hoher Staatsämter hervorgebracht hatte, fand Cicero Eingang in die führenden Kreise der senatorischen Elite in Rom. Dass er später selbst zum Konsul, d. h. in das höchste Staatsamt, gewählt wurde, ohne auf das Netzwerk einer der großen Familien zurückgreifen zu können, erfüllte Cicero zeitlebens mit Stolz. Sein Status als ‚neuer Mann‘ (homo novus ) aus einer Provinzstadt machte ihn allerdings für seine vornehmen Rivalen auch anfechtbar.

Während der turbulenten Jahre des Bundesgenossenkriegs (91–87 v. Chr.) – als er fasziniert die Taten seines Landsmannes C. Marius beobachten konnte, denen er später ein (heute verlorenes) Gedicht widmete – leistete Cicero kurz Militärdienst, beschäftigte sich sonst jedoch hauptsächlich mit dem Studium der Rhetorik und Philosophie. Das früheste erhaltene Werk aus seiner Feder, die systematische Erörterung der Redekunst in De inventione (ca. 84 v. Chr.), zeugt nicht nur von seinen Studien und Interessen in dieser

Introductory essay / Einführung 13

public speaking – i. e. postulating that rhetoric should further the good of the citizenry.

Due to political upheaval at Rome it was only relatively late – in 81 BCE, when the Sullan restoration had brought some stability – that Cicero made his first public appearance as an orator, acting as an advocate in court; in the context of the shifting alliances and enmities between the powerful families at Rome this was an eminently political occupation. In an autobiographical section of the history of Roman oratory in the later work Brutus (46 BCE) Cicero recalls that he undertook his first court cases only at that time ‘so that I would not receive my training in the Forum (non ut in foro disceremus ), as most have done, but so that, as far as I could manage, I would enter the Forum already fully trained (ut … docti in forum veniremus )’ (Cic. Brut. 311).

In later phases of his life Cicero similarly dedicated himself to literary and philosophical studies when he found the opportunity for political action limited by adverse circumstances, and much of the vast body of his writings reflects on the mutual relations between learning and literature on the one hand and the active life of the lawyer and statesman on the other.

Cicero’s first public appearances in the Forum, documented in the extant orations Pro Quinctio and Pro Sexto Roscio Amerino , soon earned him the reputation of being one of the foremost orators of his generation; and his successes in court, interrupted by a period of further study in Greece, when his health had suffered under the strain of his public appearances, ultimately laid the foundations for an unparalleled political career.

In 76 BCE Cicero successfully stood for the office of quaestor and then served in Lilybaeum on Sicily in 75 BCE. He performed his duties with particular diligence, so that he earned the trust of the local population, who turned to him when, in 70 BCE, they sought to bring suit against their former governor C. Verres. As prosecutor in this high-profile case, Cicero had an opportunity to measure himself against the leading orator of the time, Q. Hortensius Hortalus, who led the defence. Cicero’s painstakingly well-prepared prosecution was so effective that the defendant went into exile before the trial had reached its conclusion. Nevertheless, Cicero later not only published the speech he had delivered in court, but added an edition in five books of the speeches that he would have delivered in the second round of proceedings. As at many other stages in his career, Cicero made effective use of published writings, advertising his triumph over the rival Hortensius and thus asserting his claim to oratorical pre-eminence.

Cicero successfully completed the cursus honorum of high political offices, acceding to the position of aedile in 69, praetor in 66 and eventually consul in 63 BCE, reaching each office suo anno , that is at the youngest possible age – an extraordinary feat for the ‘new man’ from Arpinum. Cicero’s political career, and especially

Zeit, sondern ebenso von seinen Ambitionen: So enthält das Vorwort zu dieser Schrift, das auf das Konzept ‚humanistischer Bildung‘ in späteren Zeiten großen Einfluss ausüben sollte, einen Lobpreis auf die Redekunst und formuliert dabei das Ideal von deren politischem Nutzen – d. h. die Forderung, dass die Rhetorik dem Allgemeinwohl der Bürgerschaft dienen müsse.

Die politischen Wirren im Rom der Zeit führten indes dazu, dass Cicero erst recht spät – im Jahr 81 v. Chr., als mit der Restauration unter Sulla relative Stabilität einkehrte – als Anwalt vor Gericht auftrat und sich dabei erstmals als Redner der Öffentlichkeit stellte; im Kontext der ständig wechselnden Allianzen und Rivalitäten zwischen den führenden Familien Roms war das Amt eines Anwalts eminent politisch. In einem autobiographischen Abschnitt der Geschichte der römischen Redekunst, die Cicero später im Brutus vorlegte (46 v. Chr.), schreibt Cicero, dass er erst zu diesem Zeitpunkt die Tätigkeit bei Gericht aufgenommen habe, „damit ich nicht erst auf dem Forum meine Ausbildung absolvierte (non ut in foro disceremus ), wie es die meisten getan haben, sondern damit ich, soweit ich es erreichen konnte, bereits vollständig ausgebildet das Forum beträte (ut … docti in forum veniremus )“ (Cic. Brut. 311).

Auch in späteren Lebensphasen widmete sich Cicero immer wieder der Literatur und Philosophie, wenn die Möglichkeiten für politische Tätigkeit durch widrige Umstände eingeschränkt waren; viele seiner zahlreichen Werke befassen sich mit den Wechselbeziehungen zwischen der Beschäftigung mit Literatur und Kultur auf der einen Seite und der vita activa des Anwalts und Staatsmannes auf der anderen.

Ciceros erste öffentliche Auftritte auf dem Forum, die in den erhaltenen Reden Pro Quinctio und Pro Sexto Roscio Amerino dokumentiert sind, brachten ihm bald den Ruf eines herausragenden Redners seiner Generation ein, und seine Erfolge vor Gericht, die durch einen Studienaufenthalt in Griechenland unterbrochen wurden, als er aufgrund der großen Belastungen öffentlicher Auftritte gesundheitlich angeschlagen war, bereiteten seiner einzigartigen politischen Karriere den Weg.

Im Jahr 76 v. Chr. bewarb sich Cicero mit Erfolg um das Amt des Quästors und übte es im folgenden Jahr, 75 v. Chr., im sizilischen Lilybaeum aus. Er führte sein Amt mit so großer Hingabe und Sorgfalt aus, dass er das Vertrauen der einheimischen Bevölkerung gewann, die sich an ihn wandte, als sie, im Jahre 70 v. Chr., einen Prozess gegen den ehemaligen Statthalter C. Verres anstrengte. Als Ankläger / Staatsanwalt in diesem Gerichtsfall, der in der Öffentlichkeit große Beachtung fand, hatte Cicero die Gelegenheit, sich an Q. Hortensius Hortalus zu messen, dem führenden Redner dieser Zeit, der die Verteidigung übernahm. Cicero hatte seine Anklage so gut und sorgfältig vorbereitet, dass sich der Angeklagte noch vor Abschluss des Verfah-

14 Introductory essay / Einführung

his candidature and election for the consulship, however, were overshadowed by increased factionalism in the Senate and political unrest at Rome. The situation escalated when the nobleman L. Sergius Catilina (Catiline), who saw himself defeated in the consular elections, apparently sought to gain power by overthrowing the elected government. As consul, Cicero uncovered the so-called conspiracy and forced Catiline to show his true colours by leaving Rome and leading an open military insurrection. Moreover, Cicero succeeded in intercepting crucial exchanges between other conspirators still at Rome, who were arrested and eventually put to death. The insurgents were confronted in the field, and Catiline was killed.

Cicero’s role in the defeat of the Catilinarian Conspiracy was his greatest political achievement; his supporters and Cicero himself hailed it as the second foundation of the Roman state. Indeed, Cicero not only wrote up four of the speeches he had delivered (Cic. Cat . 1–4), apparently as part of a purposefully planned edition of his ‘consular speeches’ (Cic. Att . 2.1), but he also sought to enjoin others to treat the subject in their writings and repeatedly returned to it himself, going so far as to praise his achievements in a hexameter poem, De consulatu suo (of which only fragments remain).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Cicero’s apparently unabashed self-advertisement did not remain without critics. Crucially, the actions of his consulate met with controversy. While the Senate decreed celebrations of thanksgiving in Cicero’s honour and bestowed on him the honorific title ‘Father of the Fatherland’ (pater patriae ), Cicero’s adversaries immediately criticised his handling of the crisis and objected to what they saw as the extrajudicial killing of the Catilinarians. The contested legacy of his consulate plagued Cicero’s later life and led to a brief period of exile from Rome in 58/57 BCE, when a new enemy of Cicero’s, P. Clodius Pulcher – apparently indulged by the ever more powerful alliance between Caesar, Crassus and Pompey –, ascended to the People’s Tribunate and enacted laws criminalising Cicero’s consulate. Cicero’s assets were seized and his house partly destroyed. Cicero was allowed to return after a little more than a year, when political alliances had shifted once more, and he was fully reinstated in his rights and possessions (the debate around the restitution is documented in the ‘Post reditum speeches’).

Nevertheless, this was a traumatic experience, as Cicero’s extant letters show, and it certainly contributed to Cicero’s relative reticence on contentious political matters and his increasing acquiescence to the primacy of the triumvirate in the 50s BCE. To some extent, this situation was the impetus for two of Cicero’s most ambitious works, the mature discussion of rhetorical theory and oratorical practice in De oratore (55 BCE) and his account of political theory and Roman statesmanship in De re publica (54–51 BCE). In

rens ins Exil begab. Gleichwohl veröffentlichte Cicero später nicht nur die Rede, die er tatsächlich vor Gericht gehalten hatte, sondern zugleich eine fünf Bände umfassende Edition jener Reden, die er im weiteren Verlauf des Verfahrens gehalten hätte. Wie oft in seiner Karriere nutzte Cicero effizient die Publikation seiner Werke: Er verewigte so seinen Triumph über den Rivalen Hortensius und erhob damit den Anspruch auf die Stellung des führenden Redners. Mit Erfolg durchlief Cicero den cursus honorum hoher politischer Ämter. Er wurde für 69 v. Chr. zum Ädil, für 66 zum Prätor und schließlich für das Jahr 63 zum Konsul gewählt, und zwar jeweils suo anno , d. h. im jüngst-möglichen Alter – ein außerordentlicher Erfolg für den ‚neuen Mann‘ aus Arpinum. Ciceros politische Karriere, und insbesondere seine Kandidatur und Wahl zum Konsul, wurden indessen von zunehmenden Zerwürfnissen zwischen verschiedenen Senatsparteien und politischen Unruhen in Rom überschattet. Die Lage eskalierte, als der Patrizier L. Sergius Catilina, nachdem er im Rennen um das Konsulat unterlegen war, versucht haben soll, die gewählte Regierung in einem Putschversuch umzustoßen. Cicero, der amtierende Konsul, deckte die sogenannte Verschwörung auf und zwang Catilina, Farbe zu bekennen: Dieser verließ Rom und strengte eine offene Revolte gegen Rom an. Darüber hinaus gelang es Cicero, die Kommunikation zwischen weiteren Verschwörern, die noch in Rom verweilten, abzufangen und die Verschwörer zu verhaften und schließlich hinzurichten. Außerdem kam es zuletzt zu einer militärischen Konfrontation mit den Aufständischen, wobei Catilina sein Leben verlor.

Ciceros Rolle im Niederschlagen der Catilinarischen Verschwörung war sein größter politischer Erfolg; seine Anhänger und Cicero selbst stilisierten dies zu einer zweiten Gründung des römischen Staats. Dabei veröffentlichte Cicero nicht nur die vier Reden, die er in dieser Sache gehalten hatte (Cic. Cat . 1–4) – offenbar als Teil einer sorgfältig konzipierten Edition seiner ‚konsularischen Reden‘ (Cic. Att . 2,1) –, sondern er versuchte außerdem, andere dazu zu bringen, darüber zu schreiben, und kehrte auch selbst wiederholt dazu zurück; dabei ging er sogar so weit, seine Leistungen in einem hexametrischen Gedicht De consulatu suo zu besingen (das nur in Fragmenten erhalten ist).

Es erstaunt daher nicht sonderlich, dass solch ausgeprägte Werbung in eigener Sache auch Kritiker auf den Plan rief. Dabei kamen besonders Ciceros konsularische Handlungen unter Beschuss. Während der Senat eine Dankesfeier anberaumte und Cicero der Ehrentitel ‚Vater des Vaterlands‘ (pater patriae ) verliehen wurde, kritisierten Ciceros Gegner sofort seine Handhabung der Krise und protestierten gegen die in ihren Augen außergerichtliche Ermordung der Catilinarier. Das umstrittene Vermächtnis seines Konsulats beeinflusste Ciceros weiteres Leben und führte zu einer kurzen Phase der Exilierung aus Rom in den Jahren

Introductory essay / Einführung 15